Abstract

This article examines memory and monuments in the science fiction Star Trek franchise as a lens for understanding commemoration technologies and how futuristic visions of memorials anticipated real ones, especially during times of conflict. To understand the cultural reciprocity of sci-fi television and contemporary commemoration of war and trauma, we investigate the interactive website produced by the Israeli Public Broadcasting Corporation, Kan, titled Kan 7.10.360, which commemorates the victims of the 7 October 2023 Hamas massacre of civilians, soldiers, and policemen in Israel’s Gaza Envelope region. The 7.10.360 website employs advanced technologies to create what we identify as a digital “counter-monument.” By applying the concept of metamemorial science fiction relating to the Shoah, investigating its victims’ commemoration and examining the globital turn in memory work, we demonstrate that the Kan project realizes digital mnemonic practices engaged in Star Trek. We argue that the renowned series performs and anticipates three aspects of globital memory work and novel digital commemoration, also prevalent in the Kan 7.10.360 website: the personalization of memory using images; televisual testimony or documentation that mediates personal experience; and the display of objects that symbolize quotidian aspects of the victims’ lives.

Keywords:

Star Trek; 7 October 2023 Hamas massacre; Israel; Palestine; Gaza; memory; counter-monument; science fiction; commemoration; Shoah; war Words alone cannot convey the suffering.Words alone cannot prevent what happened here from happening again.Beyond words lies experience.Beyond experience lies truth.Make this truth your own.1

1. Introduction

The voiceover in the opening titles of the science fiction television series Star Trek is among the most renown in television history. It concludes with the declaration that the space travels of the “Starship Enterprise” will “boldly go where no man/no one has gone before.”2 Taking our cue from this voiceover, in this article we examine the ways in which the Star Trek franchise has “boldly remembered,” considering how memory and monuments were integrated in its plots and screenplays. Our aim is to look at Star Trek as a cultural lens for understanding commemoration technologies and how futuristic visualizations of memorials anticipated real ones, especially during times of conflict and—in this case—with regard to the Israel-Hamas Gaza conflict.

Memory-making and commemoration of conflict and war have evolved significantly during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries—from monuments to counter-monuments, from written and recorded testimonies to recent mnemonic digital technologies. Today, scholars across multiple disciplines study digital spaces of commemoration, comparing them to physical monuments, locating them within the historical development of commemoration practices, and examining their unique capabilities. Exploring how memorials are portrayed in science fiction is particularly relevant to recent developments such as the digital project produced by the Israeli Public Broadcasting Corporation, Kan, titled Kan 7.10.360, which commemorates the victims of the 7 October 2023 Hamas massacre of Israeli civilians, soldiers, and policemen in the kibbutzim, moshavim and towns of Israel’s Gaza Border Envelope (Kan 7.10.360: Digital Memorial Project n.d.). While the Star Trek sci-fi series and films have been researched from numerous cultural-historical aspects, the Kan 7.10.360 digital documentation project is new and has not received scholarly analysis.

Our aim is to investigate the visual aspects of commemoration by analyzing television set design, historical physical memorials, as well as aspects of the graphic design and photographic evidence of the Kan project. Relying on theories from the fields of memory studies, literature studies, art history, and film and television studies, we argue that science fiction television provides a cultural mirror to digital commemoration. It has the capacity to contribute to broader cultural discourses and production surrounding commemoration in the twenty-first century. Moreover, we demonstrate that specific episodes of Star Trek prefigured and ‘pre-imagined’ the integration of technological advancements in commemoration practices. The paper provides a brief introduction of the series—Trek for non-trekkies, so to speak—followed by a discussion of the theoretical background. We then discuss the Kan 7.10.360 project and specific Star Trek episodes, analyzing their fictional memory-making monuments, technologies and their visual representation. We demonstrate how Star Trek’s engagement with memorials presented concepts that anticipated those applied in the 7.10.360 project, which employs advanced techniques for documenting and mediating the Hamas Massacre to the public, representing a digital method of commemoration and documentation in a conflict zone. In view of the Star Trek franchise’s undisputed centrality to shaping the role of popular science fiction in broader cultural discourses, we demonstrate that studying the series is instructive in understanding the origins and meaning-making of current digital commemorative methods.

2. Star Trek, Culture and Memory

Since its creation in the 1960s, Star Trek has been a significant cultural phenomenon spanning multiple generations of television series, films, animated productions, merchandise, and scientific inspiration. The franchise has consistently served as a frontier for cultural, societal, and technological exploration and advancement, explored within a futuristic, often utopian framework. Many real-life technologies were indeed inspired by the series and later developed in reference to ideas first depicted on screen. This is partly because, unlike other science fiction franchises, the Star Trek universe has consistently offered plausible explanations for the principles behind its futuristic technologies (Allgaier 2018, pp. 85–86). These now-familiar technologies include mobile phones, tablets, touch screens, artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and more. Groundbreaking representations of cultural and social issues in Star Trek are also numerous, ranging from the first interracial kiss in popular American television to inclusive representations of the LGBTQ+ community.3

However, even when real-world developments resemble elements of the franchise, it is important to acknowledge that not all of these parallels result from direct influence. In many cases, the connection is indirect or uncertain. For the purposes of this study, then, we use verbs such as “anticipated,” “pre-imagined,” and related terms primarily to describe technologies and social or cultural developments that were not necessarily shaped by the show, but that Star Trek had already explored, in some form or another, decades earlier, mediating these to millions of viewers through its screenplays and set designs. In these cases, the franchise anticipated or pre-imagined advancements that would later emerge in the real world, rather than directly prompting them. As the following discussion will demonstrate, this anticipatory quality is central to understanding Star Trek’s cultural significance.

Building on this understanding of Star Trek’s anticipatory imagination, it is equally important to consider how the franchise has applied this imaginative capacity to questions of memory, commemoration, and historical trauma. Given this trajectory, it is unsurprising that as part of the series’ engagement with contemporary cultural and social phenomena, Star Trek has explored representations of historical atrocities and memorial and commemoration techniques throughout its run. It has scripted sci-fi plots with innovative approaches to commemoration and memory preservation of both alien and human civilizations, referring to events in human history, most notably the Shoah, the Holocaust of the Jews during World War II. This is exemplified in various episodes, with specific alien species allegorized to represent Jews (Bajorans, especially in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine) and Nazis (Cardassians, in the same series) (Kapell 2000, pp. 104–14). More directly relevant to this paper is the franchise’s representation and envisioning of monuments and mnemonic technologies among advanced species beyond Earth. Through its depiction of these technologies, Star Trek anticipated the kind of global, digitally mediated commemoration practices emerging in projects like Kan 7.10.360.

3. Theoretical Premise

To demonstrate what at first glance may seem like a big “cultural leap”—from real conflicts to imagined ones—we employ several theoretical perspectives. Our first premise relies on the research of digital memory in a “globital” age. This is a term coined, to the best of our knowledge, by Anna Reading in her book Gender and Memory in the Globital Age. Reading merges the words “global” and “digital” to describe the profound transformations evident in the ways culture engages memory, considering processes of globalization and digitization (Reading 2016). We find that now, more than ever, the way in which Star Trek approached memory and commemoration is relevant to the “globital age.” In her book, Reading also discusses sociological imagination and the cultural role of literary utopias in conceptualizing mnemonic technologies. Several scholars have demonstrated the utopian characteristics of Star Trek (Gonzalez 2018; Porter 2013; Booker 2008, pp. 195–208). As such, Star Trek can be analyzed as a part of what Reading identifies as “imaginaries [that enable] one to be momentarily discursively dis-embedded from the globital memory field in which the 21st-century human being is uncritically immersed” (Reading 2016, p. 66). Reading underscores that memory technologies in utopias thus afford us with new perspectives regarding memory work in our own time. Consequently, we approach the globital as a phenomenon that involves not only technology and advances in computing and communication—but also art and design in the form of commemorative monuments (imaginary and real), website design and televisual sci-fi culture. We demonstrate how, in its representation of imaginary physical monuments or vessels, Star Trek’s visual culture anticipated globital mnemonic technologies as embodied in the 7.10.360 project.

The concept of “metamemorial fiction” is also important to the analysis we present. Australian sociologist Shameem Black terms metamemorial fiction as a literary strategy involving the commemoration of violence by an author who tells a new fictional story that has a direct and recognizable relation to a historical event. Black argues that how we commemorate conflict and war is a question that has become more debated and scrutinized in the age of globalization; she demonstrates that fictional storytelling has a meaningful role in commemoration and its critique, alongside veritable documentation. Adopting Black’s observation that metamemorial fiction “compels us to reflect on the act of forging public memorials” (Black 2011, p. 46), we suggest that Star Trek functions as a form of anticipatory metamemorial practice, constituting “metamemorial science fiction.” The series explores what Mark Alan Rhodes II calls “alternate pasts, presents, and futures” through a “futuristic lens of history.” (Rhodes 2017, pp. 29–30).

Our analysis is further grounded in James E. Young’s analysis of Holocaust monuments and Paul Arthur’s theorizing of digital memorial spaces. Young’s research and his participation in developing policies regarding Holocaust memorials following German reunification in the 1990s made him an international authority on physical memorials. Young’s important work has deconstructed the idea of the traditional tangible monument (Ehrenpreis 2018). He developed the concept of the counter-monument—a monument whose abstraction and, at times, inconspicuousness allow for multiple interpretations (Young 1999, pp. 1–10). One of Young’s key observations is that in the current age “monuments are increasingly the site of competing meanings, more likely the site of cultural conflict than of shared national values and ideals” (Young 2000, p. 119). Arthur’s examination of digital memorials identifies differences between “traditional” memorials and digital platforms. Arthur and Young, respectively, underscore the digital monument and the counter-monument’s capacity to generate “ongoing connections with the deceased” (Arthur 2014, p. 152) and transform memory into a process (Young 1999, pp. 1–10).

Relying on these theories we demonstrate that, as metamemorial science fiction, Star Trek’s engagement with futuristic mnemonic technologies performs and anticipates three aspects of globital memory work and commemoration, also prevalent in the Kan 7.10.360 project: First, the personalization of memory using images; second, textual testimony or documentation that relates personal experience; and third, objects that symbolize quotidian aspects of the victims’ lives. We emphasize the centrality of reconstructing a timeline of events in personalizing memory in both Star Trek’s metamemorial science fiction and in the 7.10.360 project. Using Young and Arthur’s theories, we identify the reconstructed timeline, as well as the digitization of memory in both the sci-fi monuments and the 7.10.360 project, as visual manifestations of commemorating conflict through process rather than by a singular object or physical “event”, interpreting the 7.10.360 website as a globital counter-monument.

4. Visualizing Conflict in the Kan 7.10.360 Project

On Saturday, 7 October 2023 at 6:29 a.m., the day of the Jewish celebration of Simchat Torah, the towns, kibbutzim and moshavim of the Gaza Envelope were heavily bombarded with rockets fired from the Gaza Strip. Versed in such attacks for over two decades, civilians took shelter in their domestic saferooms, unaware of the infiltration of thousands of Hamas terrorists. A murderous attack ensued, in which 1163 women, children and men—mostly civilians—were killed and over 250 were kidnapped. The commemoration website titled Kan 7.10.360: A Digital Memorial Project, was developed by the Israeli Public Broadcasting Corporation Kan to document these events and the massacre, and commemorate its victims. The project is accessible to the public via its website in Hebrew and in English. The website is the second digital commemoration project developed by high-tech company AppsFlyer and Diskin company, following their first project: a panoramic view and digital guided tour of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, physically located in Poland.4

Upon entering the website, visitors first encounter a black landing page in Hebrew, displaying a trigger warning: “The content contains descriptions and documentation that are difficult to view,” accompanied by a brief explanation of the project’s purpose and documentation process (Figure 1). Immediately after this introductory screen, a satellite map marked with red disks and teardrop-shaped pins appears, indicating sites where the 7 October massacre occurred. The map spans from Zikim, north of the Gaza Strip to Kerem Shalom and Shlomit near the Israel-Egypt border in the south. It denotes, as mentioned above, urban and rural locations, as well as routes attacked that day. The satellite aerial view features both Israel and the Gaza Strip. Rather than providing a detailed scholarly and framed historical account of the events, the interactive website focuses on individual stories. Visitors can choose their navigation path from red pins and disks marked on an earth-brown satellite map framed by a plain black screen and an opaque, black, Mediterranean Sea. Pins represent specific locales. Disks represent routes.

Figure 1.

Trigger Warning on the Kan 7.10.360 project homepage (photo source: www.710360.kan.org.il, accessed on 21 December 2025). The English translation of the Hebrew text reads: “The interactive site of the Gaza Envelope map for 7 October 2023 is intended to document and commemorate the events that took place in the communities around the Gaza Strip through real-time records, minute by minute. The project is under construction and investigation; in the next stages many more points will be added to the map, including IDF bases, expanded party areas, and the roads leading to the Gaza Envelope. For more details and to get in touch, https://www.kan.org.il/content-pages/about360/ (accessed on 21 December 2025). Warning: The content includes descriptions and documentation that are difficult to view.”

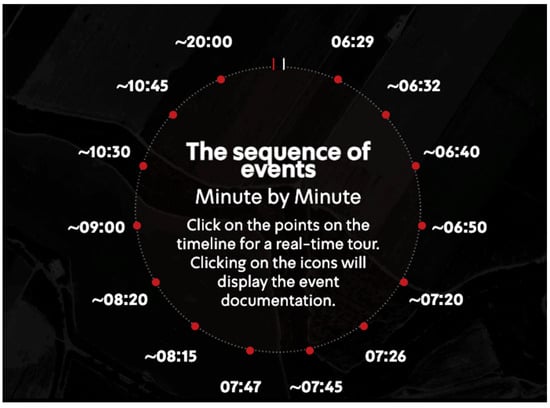

When selecting a locale or route a new page with a close-up satellite map of the location (and in some cases a background photo) comes up. These pages offer in-depth exploration, as each location features stories of families and individuals affected by the massacre—the murdered, kidnapped, and survivors. Following a brief introduction to each family or individual’s account, in most cases with a partly transparent prewar photo of them in the background, events are presented in a clock-like dotted circle (Figure 2). The dots are red and specific hours are typed in a white sans-serif font in their outer circumference. The time indicated on the clock commences at 6:29 a.m., when the attack began, and ends at 8:00 p.m. or later, the approximate hours of the night during which many of the survivors managed to evacuate or escape. The website visitor can click on each of the marked hours to view what occurred at that specific time. A chronological list of dates since 7 October shows the aftermath of survivors and victims. Various points in each story include relevant photographs of people and objects, videos, screenshots of WhatsApp messages, and other documentation—images of individuals before the massacre, footage of terrorists breaking into specific locations, and additional photographic evidence that Kan collected and uncovered.

Figure 2.

The Kan 7.10.360 visual and interactive clock “minute by minute” (photo source: www.710360.kan.org.il, accessed on 21 December 2025).

The project is personal and emotional in nature, as the interactive platform enables visitors to choose their navigation path, focusing on individual stories. The clock-like design can evoke fear or stress, creating what Arthur describes as the integration of “the intensely personal and painful into the everyday,” a key characteristic of digital memorialization’s “therapeutic dimension” (Arthur 2014, p. 158). The integration of photos, WhatsApp conversations, videos, and interviews makes the experience more visceral than text alone or the lists of names often found on physical monuments. To demonstrate this we selected a key example documenting the Kleiman family from Kibbutz Holit, who hid and managed to escape and survive.

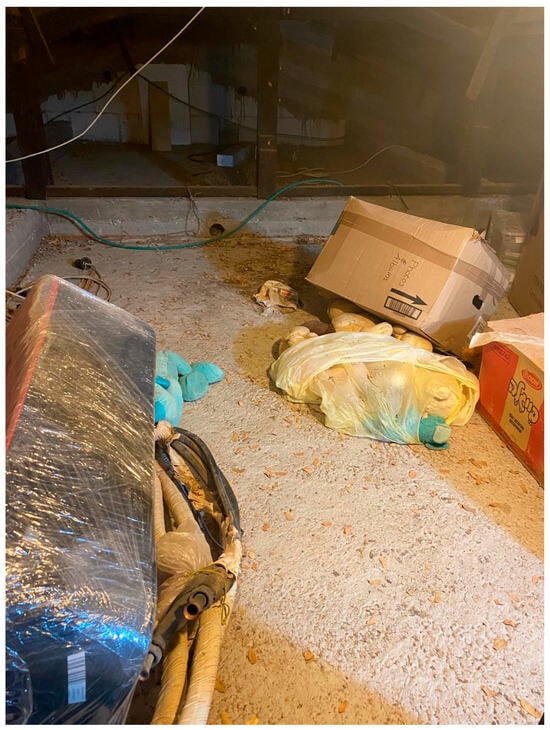

When the visitor selects the Kleimans’ page from the map of Holit, a happy family photo of Harida, Lior and their children—thirteen-year-old Hailey and sixteen-year old Aidan—appears as a gray-scaled, partly transparent, background. When selecting the hours indicated on the above-mentioned clock, texts in white letters appear on the nearly black background. The Kleimans survived owing to Harida’s common sense that led the family to the attic, rather than the safe room, which would have been the obvious place where the terrorists would search. The family’s actions and perseverance while hiding for eleven hours is retraced in written documentation, which cites Harida saying: “go up to the attic, in the saferoom we’ll die.” Alongside these texts, below the clock’s center, are standard icons representing photos, recordings, and WhatsApp conversations, when available. One photo icon, for example, opens a picture of the attic (~6:40 on the clock, Figure 3). It shows boxes and bags used for storage, including a torn one containing the children’s old stuffed animals, thus relating the everyday nature of domestic storage and childhood memories. The following photo (~6:45 on the clock, Figure 4) powerfully fuses more toys—legos and a child’s medal won in a competition—with the impending massacre, as in its center lays the knife taken by Harida to protect the family. Gunshots were recorded on phone during the attack, and their sound is accessible via the microphone icon (~15:18 on the clock). Additionally, WhatsApp messages from the family’s cellphones can be selected from the “call” icon. WhatsApp conversations are visualized in a way that mimics their reception in the app. They document the personal and the everyday, in the hours when the residents of the Gaza Envelope were as yet unaware of the magnitude of the 7 October attack. These digital and digitized testimonies of a day that began just like every other, “infiltrate” the website visitors’ everyday lives, as suggested by Arthur (2014, pp. 152–53), and we will elaborate on this issue in the following sections.

Figure 3.

Picture of the attic where the Kleiman family hid, as presented on the Kan 7.10.360 website (photographed by Lior Kleiman, reproduced courtesy of Lior Kleiman).

Figure 4.

Picture everyday objects and a knife from the Kleiman family home, as presented on the Kan 7.10.360 website (photographed by Lior Kleiman, reproduced courtesy of Lior Kleiman).

The Kan project is not the first initiative to digitize sites of atrocity as a means of commemoration and testimony. As noted above, the companies involved in developing the 7.10.360 website had previously collaborated on a digital guided tour of the Auschwitz–Birkenau concentration camp. Upon entering this Shoah website, the viewer encounters a grayscale image of the railway leading into the camp, accompanied by three smaller grayscale photographs at the bottom of the page. Above these, the instruction “Choose from the available tours” invites the user to select a preferred path. Once an option is chosen, a panoramic image of the camp appears—this time in color. The visitor can navigate the space by clicking on arrows that enable a virtual “walk” through the chosen location. A sidebar offers several functions, including an “i” icon that provides additional information or a descriptive text. Selecting this option opens an extended description of the site and panorama, as well as written testimonies (“witness accounts”) of camp survivors. The witness accounts are presented solely as text: the website displays the survivor’s name and a paragraph-length excerpt of the testimony, without accompanying images.

Digital modes of Holocaust commemoration have also been developed in pedagogical contexts, through interactive platforms that incorporate virtual reality (VR), video games, and recorded testimonies. A notable example is the short VR film The Last Goodbye, which follows Majdanek survivor Pinchas Gutter as he guides the viewer through the camp. As Kate Marrison observes in her analysis of the film, “the user is both physically and imaginatively invited to occupy this new perspective—the attitude of the familial witness, through a virtually extended self” (Marrison 2021, p. 17).

These examples demonstrate that interactive and digitized memorials are developing in various directions, each with its own approach to structuring memory and user engagement. Within this broader context, the Kan project presents a distinct configuration. Its navigational design operates through a two-step structure: users begin by selecting a specific place such as a town, kibbutz, moshav, or route, and then choose an individual or family associated with that location. The interaction is therefore anchored in the experiences of particular people whose stories unfold across the hours of 7 October.

As mentioned, the Kan project incorporates a range of materials including photographs, WhatsApp conversations, video clips, screenshots, and other documentation that shape the visitor’s encounter as one centered on personal narratives. The user follows the events almost moment by moment as they occurred to an individual or family, creating a form of mediated witnessing grounded in specific lives. This mode of engagement is comparable to the way the story is told by Pinchas Gutter in The Last Goodbye and—as we will show—to the mnemonic devices depicted in the Star Trek episodes examined in this study. The latter construct immersive frameworks through which characters are positioned as witnesses or even first-person participators. In both cases, the technological interface functions not only as a container for testimony but also as a mechanism that structures how remembrance is experienced. Emphasis on personal experiences blurs boundaries between individual and collective, and this can be seen in Star Trek’s earliest application of metamemorial fiction, discussed in the next section (Black 2011, pp. 41–42; Rhodes 2017).

5. Metamemorial Science Fiction: Star Trek’s “Conscience of the King”

The first Star Trek episode we discuss is Conscience of the King (S01E13). It belongs to Star Trek: The Original Series (TOS) and was first aired in 1966. It represents one of the series’ earliest examples of creating metamemorial science fiction. While this is an early episode that does not anticipate globital mnemonic devices, it lays the basis to understanding how metamemorial fiction dealing with mass massacres operates within the series. Conscience of the King engages with memories of a massacre, and contains clear references to the Shoah. In the past few decades, the Shoah has been profoundly connected to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and these connections have received ample scholarly attention (See, for example, Levanon 2021, pp. 58–66). As a result, visual cultural analysis of 7.10.360—a memorial website related to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict—is interlaced in understanding approaches toward memorials representing the Holocaust, whether physical or digital. Metamemorial science fiction dealing with the holocaust in the early years of Star Trek is therefore useful in explaining the evolution of such connections.

Holocaust researchers Alvin Rosenfeld and Gulie Ne’eman-Arad demonstrate that throughout the second half of the twentieth century the Holocaust was largely mediated to Americans through film and television (Rosenfeld 1995, p. 35; Ne’eman-Arad 1996, pp. 14–22). Conscience of the King is a clear example of this. It was produced twenty years after the end of World War II, at a time when the Holocaust began receiving public attention after a long period of “muteness”, as Rosenfeld termed the preceding era (Rosenfeld 1995, p. 35). This early episode of Star Trek presented to the American audience a fictional story whose main theme was how a recent massacre of unprecedented scale is remembered by individuals.5 Only four years after the trial and sentencing of Adolf Eichmann in Israel—an event described by Ne’eman-Arad as a watershed in American awareness of the Holocaust, the Conscience of the King raised moral questions and a fateful encounter between the perpetrator of a mass massacre and its survivor-witnesses. It is therefore important to examine discourses on the Holocaust in America, where Star Trek was made, when analyzing the series’ meanings.

The plot of Conscience of the King presents the Starship Enterprise as it is called to a planet under false pretense, only to realize that an old friend of the ship’s Captain Kirk believes he has identified “Kodos the Executioner”—a cruel leader who commanded a massacre from which only a handful of witnesses—Kirk, his friend and another Enterprise crew member among them — survived. As a fictional story with a recognizable relation to a historical event, this plot falls under Black’s conceptualization of metamemorial fiction, carried here to include science fiction. The episode was filmed during the Cold War, with the shadow and the memory of WWII looming large. Like several other episodes in TOS, current political themes were represented in the sci-fi narrative. Here, Kodos the Executioner hides his identity, living as a Shakespearian actor under the pseudonym of Anton Karidian. He is gradually exposed by the living victim-witnesses, while his daughter tries to kill the latter to conceal her father’s true identity. This plot correlates to the legal and political mission of exposing Nazi criminals in hiding in order to try them, which expanded in the 1960s when it began to receive public attention. The important role of the witnesses in this process—as in the above-mentioned case of Adolf Eichmann—was emphasized and received publicity as well (Marrison 2021). The science-fictional Conscience of the King similarly presented the importance of witnesses’ coping with the difficult memories of mass massacre, for the moral purpose of exposing a perpetrator in hiding.

Highlighting the central role of witnesses in the popular science fiction series sixty years ago formed part of the initial cultural engagement with the unfolding horrors of the Holocaust through witnesses’ stories. It is noteworthy that nowadays, in the globital age, acknowledgment of the witnesses’ role in commemoration has increased, as Holocaust history enters the post-witness era. In American culture this has been embodied, for example, in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC (USHMM), where visitors themselves are positioned as a witness in the mediation of the exhibition (Popescu and Schult 2020, pp. 135–51). This is also represented by the advent of the “digital witness,” which we discuss in the next section.

An additional metamemorial aspect in the Conscience of the King is the aggressor—Kodus’—attempt to erase or deny the memory of the atrocity committed by him. However, towards the episode’s end, a conversation between Kirk and Kodos presents the latter accepting responsibility for his crimes. The relationship of this TOS plot to the post-Holocaust events is thus clear and present (Horáková 2018, pp. 13–27), alluding, through this imaginary narrative, to post-World War II efforts to hunt down Nazi criminals. Located within Star Trek’s now utopian universe, the viewer learns that the usually impeccable moral standards of the series’ protagonists were threatened in the very recent past by destructive forces.

This “sociological imagination”—to use Reading’s words—was also grounded in the personal experiences and memories of the creators of the show: the screenplay for this episode was written by Barry Trivers, a successful film writer who had already written WWII-related screenplays.6 Writer/producer Gene L. Coone (1924–1973) was an Emmy award winning writer and producer. He served as a marine (stateside) during WWII and the Korean war and was also a military reporter (Ina Rae Hark 2022). Gene Rodenberry (1921–1991), Star Trek’s legendary creator and producer, flew 89 combat missions in the Army Air Force during World War II and worked as a commercial pilot after the war (Alexander 1994). The first series he produced, The Lieutenant, dealt with Marines during the Cold War. Thus, the series’ creators and the writer of the episode all harbored direct memories of World War II. Creating metamemorial science fiction about the Holocaust in Conscience of the King thus mediated the most tragic memories and events of the War to American viewers, through comparable events in the Star Trek narrative. An alternative past enacted on a distant planet was presented, and the episode personalized memory through the accounts and actions of witnesses.

6. “A Memory in One’s Own Head”: Pioneering the Visual Culture of Digital Memory in Star Trek TNG

The theme of memories of a catastrophe and how it is mediated to viewers through the characters’ personal experiences, was therefore present already in the 1960s. Almost thirty years went by, and the series was renewed with Star Trek: The Next Generation (TNG). Metamemorial science fiction in the 1990s’ series reflected changes both in how the Holocaust was perceived and in memory work surrounding it. Moreover, technologies for preserving history and reviving it changed dramatically. The shape and function of physical memorials changed, and increasingly overlapped new digital modes of commemoration.

Young addressed these changes: citing German artist Horst Hoheisel, he observed that a monument is “an invitation to passersby… to search for the memorial in their own heads. For only there is the memorial to be found.” (Young 1999, p. 1). Such a statement reflected a new acknowledgement of the complexity of memories when shared by different peoples—as in the case of Germans and Jews or Israelis. In the creation of physical Holocaust memorials, this implied a move away from explicit figural sculptures—such as the Scroll of Fire memorial in Israel—a tall bronze, somewhat cylindrical, monument with a figural relief representing events “from Holocaust to Revival” (an Israeli concept reflecting the establishment of the State of Israel following the genocide of World War II) (Figure 5). The new non-figural memorials were far more abstract creations—such as Micha Ullman’s Empty Library (installed in 1995) (Figure 6). At first glance this installation, created to memorialize the event of the Nazi book burning in Babelplatz (Babel Square), Berlin, looks like a glass tile arbitrarily set on the pavement of the Square. Only upon inspecting it closely does the viewer realize that under the glass is an empty library: bookshelves dug deep into the ground. This type of abstract and unassuming installation was termed by Young a “counter-monument” (Young 1999, p. 3). The concept of creating a monument that challenges traditional ones and forces viewers to “look within themselves for memory,” (Young 1999, p. 9) relates not only to tangible monuments, but also to the new role given to both witnesses and spectators in constructing memory in the globital age: more people remember more events and through digitization—many more histories, memories, memorials, and testimonies become available. Recordings, visualizations, texts and simulations afford new exposure to war and catastrophe and shape their understandings (Ben-Asher Gitler 2017). These new technologies certainly occupied a role in the affordance of abstraction in physical monuments, and we demonstrate herewith the abstraction of the visual “vessels” of digital memory in the science fiction plots.

Figure 5.

Nathan Rapoport, Scroll of Fire monument, bronze, 1971 (inaugurated), Jerusalem. Photographed by Hagai Agmon Snir (photo source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ScrollOfFireJune202023_03.jpg, accessed on 21 December 2025).

Figure 6.

Micha Ullman, The Empty Library, 1995 (unveiled), Berlin. Photographed by Luis Alvaz (photo source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Memorial_de_los_libros_quemados_en_Bebelplatz,_Berl%C3%ADn_02.jpg, accessed on 21 December 2025).

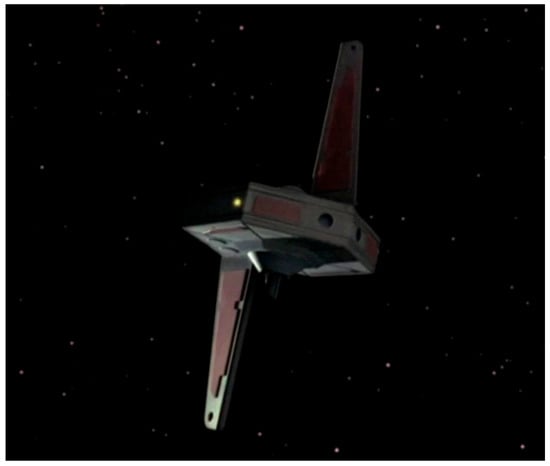

The episode The Inner Light, written by Morgan Gendel and Peter Alan Fields, was first aired in 1992 in the fifth season of TNG. It examined imaginary globital memorialization technologies through the digital personalization of memory. The plot focuses on the series’ Captain, Jean-Luc Picard, as he experiences an entire lifetime as a member of an extinct civilization after connecting to an alien probe. The probe preserves the memory of a lost world by transferring the experiences of its long-gone inhabitants to another being (Picard), creating commemoration through a process of shared consciousness. The probe serves as a physical memorial and is designed like a double, mirrored obelisk placed on a hexagon (Figure 7). Both these geometric shapes often figure in abstract memorials, in both ancient and modern ones, such as the Washington Monument in Washington D.C., designed by architect Robert Mills in the first half of the nineteenth century (Figure 8). In The Inner Light, the design of the probe as a memorial is merged with the idea of digitization and human–computer interface, or post-human design. The plot surrounds the civilization of the fictional planet Kataan, which was destroyed by natural causes—a supernova from a neighboring star. Before extinction, realizing their fate, the people of Kataan developed a digital technology capable of transferring societal knowledge to one person, requesting that this individual continue telling their story so their memory would survive. The probe preserved this knowledge by focusing on a single family. Upon connecting with the probe, for a duration of 25 minutes, “in his own head” Picard experiences and relives the life of a man named Kamin, as a spouse, father, and grandfather.

Figure 7.

The Kataan Probe, Star Trek: The Next Generation, “The Inner Light” (first aired 1 June 1992) (photo source: Memory Alpha, https://memory-alpha.fandom.com/wiki/The_Inner_Light_(episode), accessed on 21 December 2025).

Figure 8.

Robert Mills (architect), The Washington Monument, construction began in 1848, Washington D.C. (photo source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Washington_Monument_2022.jpg, accessed on 21 December 2025).

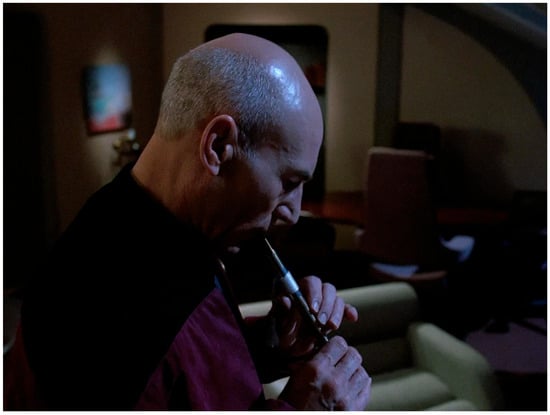

The memories that Picard-as-Kamin experiences are akin to “reading” a digital diary. The series visualizes his life in a peaceful community, living in a home designed with objects and furnishings that are Cycladic and classical Greek in spirit, suggesting an ancient yet cultivated society. During his simulated life, Picard/Kamin remains aware of his transposition, constantly searching the skies for his Starship and known existence. This aspect is represented by his developing a Dobsonian telescope to study the stars. When the supernova is about to annihilate the planet, the elderly Kamin’s life is merged with Picard’s consciousness, as Kamin’s virtual daughter says: “you saw [the probe] right before you got here”—a sentence explaining the probe’s discovery by the Starship Enterprise. The screenplay underscores the probe’s digital mnemonic role, as the lifetime family and friends of Picard-as-Kamin explain: “The rest of us are gone for a thousand years. If you remember what we were and how we lived, then we have found life again.” Two important personal objects enhance the episode’s set design, in addition to the probe: the first is a tiny pendant-replica of the probe itself given by Picard/Kamin to his wife (33:03). The second is Kamin’s physical flute, discovered in the probe after it ceases to transmit the memories. Picard, having learned to play the instrument in his simulated life, continues playing it throughout the series’ ensuing episodes (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Picard (portrayed by actor Patrick Stewart) playing the Ressikan flute, Star Trek: The Next Generation, “The Inner Light” (first aired 1 June 1992) (photo source: Memory Alpha, https://memory-alpha.fandom.com/wiki/The_Inner_Light_(episode), accessed on 21 December 2025).

In many ways, this futuristic episode anticipated the capacity of digital memory storage to include not one, but numerous stories. While it does not deal with a disaster inflicted by humans, it demonstrates metamemorial fiction following the digital turn of memory work, by its focus on private experience and process, rather than on collective or national memory. Thus, while the 1960s Conscience of the King engaged the historic role of survivors as witnesses through the lens of science fiction television, The Inner Light enlisted this medium to reflect on the role of personal memory in documenting extinct societies.

Metamemorial science fiction referring to the Holocaust, where individual memory was central to the plot, already began in the 1960s: in “The Mnemonogugues,” a story included in Primo Levi’s sci-fi collection, The sixth day and other tales (Levi 1966), the renown Italian holocaust survivor observed:

“There are those who take no interest in the past and let the dead bury the dead. However, there are also those who care about the past and are saddened by its continuous fading away. Furthermore, there are those who are diligent enough to keep a diary, day by day, so as to save everything of theirs from oblivion, and preserve their materialized memories in their home and on their person: a dedication in a book, a dried flower, a lock of hair, photographs, old letters.”(Levi 1966, p. 14)

Levi articulated the importance of recording daily actions for documenting that which is extinct. Similarly to The Inner Light, Levi stressed the quotidian as formative to commemoration. Comparing Levi’s description of an analog diary to the character Picard’s digital one, reveals that the innovativeness of The Inner Light is in its imagined technology. The digital turn thus becomes central to how this screenplay adds layers of meaning to the cultural discourses on the role of the personal memories of a single individual in commemorating mass death. The quotidian emphasis in Levi’s Holocaust-related metamemorial sci-fi similarly resonates in the Kan website. However, The Inner Light evocatively bridges the sixty-year gap between Levi’s story and the documentation of the 7 October 2023 Massacre, through its proposal of futuristic means to record the personal: the Kan website’s sequential digital experience is enabled through interactive web pages, objects are recorded in digital photos and interpersonal WhatsApp conversations offer new form and new visualization of the victims’ last grasping of normalcy.

The plot of The Inner Light also articulated the idea underscored by Young and Arthur of memory as a process capable of transforming the individuals touched by it—Picard gained new awareness of his own existence through experiencing the memories of others (Young 1999, pp. 1–10; Arthur 2014, pp. 152–75). In Holocaust documentation and commemoration, the beginning of the twenty-first century was significantly characterized by this move. Marrison theorizes “digital Holocaust memory,” arguing, for example, that Holocaust commemoration through virtual reality experience—among the most advanced forms of digitization—establishes a “digital witness” who experiences an “intimate exchange” with past events and with those who lived through the catastrophe but are deceased and can no longer tell the story (Marrison 2021). “Virtual modes of engagement”, claims Marrison, “most prominently ask the user to take up the imaginary identification… while remaining aware of their own position.” (Marrison 2021, p. 28). This analysis points to the accuracy with which The Inner Light anticipated aspects of digital technology later invented and—perhaps more importantly—the nature of the experience that the “digital witness” undergoes. While 7.10.360 is not a virtual reality project, it nevertheless creates a visual interface that implements similar concepts, as well as the personal nature of memory and its creation in “one’s own head,” which lies at the project’s core.

As mentioned, in The Inner Light the process of memory making as a personal experience was enhanced by objects—the probe pendant and the flute. These demonstrate how objects contribute to integrating commemorative experiences into the digital witness’ identity—in this case a fictional digital witness. As noted, the “real” digital probe that afforded this integration was reminiscent of abstract monuments in its design. At the end of its brief 25 minute transmission its role was done, suggesting the ephemerality of some counter-monuments constructed in the final decades of the twentieth century: For example, the Monument Against Fascism (1986), was a square column installed in Hamburg, Germany by Esther Shalev-Gerz and Jochen Gerz (Figure 10). The artists invited passersby to create personal memory through participation—signing their names—on the column, which was gradually lowered into the ground during the course of seven years, and thus disappeared. (Popescu and Schult 2020, pp. 135–51).7

Figure 10.

Esther Shalev-Gerz and Jochen Gerz, The Monument Against Fascism, 1986, 12 m × 1 m × 1 m, lead–clad column, Hamburg, Germany (photo source: Esther Shalev-Gerz, https://www.shalev-gerz.net/portfolio/monument-against-fascism/, accessed 21 December 2025. Reproduced courtesy of Esther Shalev Gerz © Studio Shalev-Gerz).

Returning to the objects and probe “monument” in The Inner Light, Black underscores that in metamemorial fiction the use of such tropes or objects is also intended to counter the “omnibus memorial,” perceived as political and public rather than personal (Black 2011, pp. 40–65). Levi, quoted above, wrote of the importance of personal “materialized memories”—not only analog documents such as photographs or letters, but also “a dried flower, a lock of hair.” (Levi 1966, p. 14). Hence, these are additional aspects that metamemorial science fiction shares with digital memory making.

The probe-as-pendant and the flute in The Inner Light, as well as the real and tragic documentation of objects on the Kan 7.10.360 (Figure 3 and Figure 4), thus contribute to establishing the centrality of objects for memory work. To further unpack the role of objects in documentation and commemoration of extinct or devastated societies, as enacted in the sci-fi episode and in the Kan 7.10.360 project, the function of objects in Holocaust commemoration can be explored. In her research of Holocaust museums, Jennifer Hansen-Glucklich explained that when displayed, objects “…act as witnesses and bear testimony in the sense that they testify to the time and place whence they came. They belong to a different world, and thanks to their authentic presence, or “aura,” we can come closer to that distant, vanished world through them.” (Hansen-Glucklich 2014, p. 120). This is certainly the case with the pendant and the flute in the imaginary screenplay.

In the case of the Kan 7.10.360 project, the photos of objects represent not only their enlistment as “witnesses”: they demonstrate the extent to which digitization—first through television and then through the internet and other means—has transformed and globalized such objects (Lomsky-Feder and Sheffi 2023). A recent example relating to the Holocaust is the traveling exhibition Auschwitz: not long ago, not far away, which is overwhelmingly grounded in original objects, mostly from Auschwitz. Intended to be viewed in its physical space, the exhibition is nonetheless meticulously digitally documented and accessible via the World Wide Web (Doering 2020, pp. 447–74; Musealia and the Auschwitz Birkenau State Museum 2019). In this case, the exhibition’s makers declare that objects serve to transform visitors into vigilant and educated members of society, who will potentially prevent a recurrence of the Holocaust, a goal intended also for the Monument Against Fascism mentioned above.8 These meanings further demonstrate the reliance of the Kan 7.10.360 web design on Holocaust commemoration and exhibition. Many of the photographs displayed in the Kan website are similar in vein to those in Figure 3 and Figure 4, presenting destroyed objects or their burnt remains, such as burnt pots and other kitchen tools. These are similar to exhibited Holocaust physical personal belongings or these objects’ photos. In both cases, these objects represent daily household activities.9 These recreate the everyday essence of the destroyed and traumatized lives of the victims.

Returning to the digital recreation of The Inner Light’s fictional Picard/Kamin family, as its physical existence ended, its story was digitally recorded and transmitted to ensure that the family members would not be forgotten. The 7.10.360 website similarly constitutes the visual and textual commemoration belonging almost entirely to families. In the case of murdered family members, it implements contemporary digital memorial practices anticipated in the TNG episode, creating what Arthur calls “continuing bonds” with the deceased (Arthur 2014, pp. 152–75). In its memory work, the website thus enlists cultural tropes and devices while digitizing them, many of which are Holocaust-related. Tellingly, the attic that concealed the Kleiman family, whose story as documented in Kan 7.10.360 is presented here, was likewise connoted; when interviewed in July 2024, Harida Kleiman said that since her neighbors on the kibbutz heard how she saved her family, they had been calling her “Harida Frank,” alluding to the famous Holocaust victim, Anne Frank: “These were hours of Shoah,” Harida said, “hours when we realized we do not have much longer to live.” (Zuri 2024). The connection to renowned personal Holocaust testimonies and Holocaust displays also constitutes an aspect of the public discourses in Israel and internationally that have compared the 7 October 2023 Massacre to the Holocaust (Mashiach and Davidovitch 2024, pp. 135–50). The 7.10.360 website’s commemoration through digital documentation and representation technologies transmitted via the internet, with its emphasis on personal timelines, family connections and objects, thus renders it in effect as a digital counter-monument that attains cultural functions similar to those anticipated in metamemorial science fiction, and that are also directly related to Holocaust commemoration practices.

7. “It’s a Memorial!”: Monuments, Conflict, and Changing Perspectives

In Star Trek: Voyager’s episode titled Memorial (S06E14, first aired 2 January 2000) the starship’s crew experiences traumatic war memories implanted by interaction with a monument designed to ensure that a planetary massacre is never forgotten. The plot is evocative of the Odyssean Siren myth and tells of the planet Tarakis: the mind of anyone traveling near it is penetrated by flashbacks that are potentially fatal. The flashbacks are of a massacre that occurred on Tarakis 300 years earlier, in which 82 people of a race called the “Nakan” were killed. The episode opens with consecutive scenes in which four Voyager crew members who traveled near the planet Tarakis during an “away mission,” experience what seems to be a real war in which they are participating as soldiers. By the end of the episode, the crew realize that these war “memories,” which by now have affected the entire Voyager crew, are implanted flashbacks—memories of the Nakan massacre. The crew members experience the massacre as if they are an aggressive military force ordered to evacuate colonists. Through these images, it is gradually revealed that the massacre occurred because it was suspected that 24 unaccounted colonists were hiding and planning armed resistance to the evacuation.

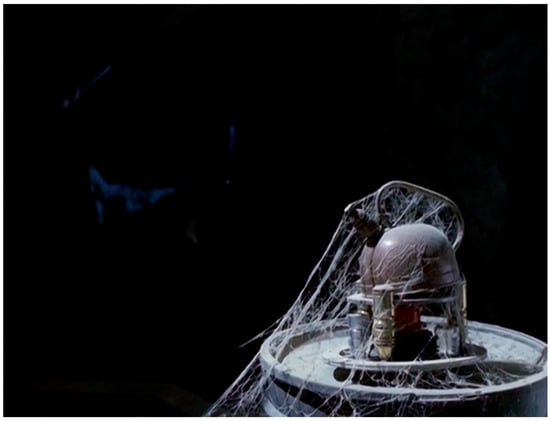

Attempting to relieve the crew of the violent memories that have taken over their minds, the Voyager crew returns to Tarakis, where they discover a monument. This is the “Nakan memorial,” the structure and digital apparatus responsible for the flashbacks, as it broadcasts a neurogenic signal containing memories of the massacre to nearby spacefarers (Figure 11). As the crew debates whether to disable the monument, the episode presents a moral dilemma about commemorative responsibility. Ultimately, the starship Voyager’s Captain Janeway decides to maintain and repair the now-deteriorating physical and digital mnemonic device while installing a warning buoy in the entrance to the star system, to prepare future travelers for a powerful immersive memory experience.

Figure 11.

The Nakan Memorial, Star Trek: Voyager, “Memorial” (first aired 2 February 2000) (photo source: Memory Alpha, https://memory-alpha.fandom.com/wiki/Memorial_(episode), accessed 21 December 2025).

By presenting a narrative that focuses on a process of understanding memories and deciphering the physical-digital function of a memorial, the episode questions the ethics of forced memory as commemoration and the psychological impact of experiencing others’ trauma, issues directly relevant to Black’s analysis of memorial authority and the ethics of “outsider participation” in commemorative processes (Black 2011, pp. 40–65). In what follows, we discuss several aspects of such commemoration and memorial methods, and how they anticipate the Kan 7.10.360 project.

As Ronit Milano noted in her call for this Special Issue, visual culture in conflict zones offers insights into the human condition, particularly through visual narratives, representations through visual media and its impact on collective memory. This is especially relevant for the unique case of the Kan project, where evidence is still being collected, and at the time of writing this article the conflict is ongoing. The events on the fictional Tarakis are experienced as very recent flashbacks, thus providing some correlation to the issue at hand.

Similarly to The Inner Light episode, the set design of Memorial visualizes a physical monument inspired by artistic traditions of obelisks and—in this case—inscribed cenotaphs. The commemorative role of the physical monument is integrated with science fictional technology as it is embedded with a transmitter of neurogenic pulses, integrating imaginary digital methods with a spatial monument.

The Star Trek: Voyager episode additionally represents mnemonic technologies that feature images, textual testimony, and objects. These metamemorial science fictional technologies anticipate globital mnemonic devices. For example, they predict the accessibility, immediacy and hyperspeed with which events and their memorialization can be shared in the globital age (Reading 2016). Perhaps most significant is Memorial’s predictive exploration of “immersive witnessing” (Marrison 2021, p. 18)—a memorialization approach used for the commemoration of conflict and atrocities. Through screenplay and televisual devices, Memorial does so already in 2000, while actual extended reality commemoration began circa 2015.10 The cenotaph text, quoted at the epigraph of the present article, articulates the logic of immersive witnessing related to war. This text functions as metamemorial fiction, offering an interesting perspective when applying it to real events and commemoration projects such as Kan 7.10.360. The inscription manifests that the monument is not just a spatial artifact. It signifies that to fully understand the ancient atrocity on Tarakis one must immerse oneself in the events, rendering them one’s own experience and truth. Although the 7.10.360 project is a two-dimensional digital commemoration, its interactive platform similarly attempts to create an intimate bond between the visitor and the events and victims of the 7 October 2023 Massacre.

Recent empirical research underscores the profound psychological toll of directly experiencing the 7 October 2023 attacks: individuals present in the Gaza-envelope communities had a threefold higher likelihood of probable PTSD and a twofold higher likelihood of depression (Levi-Belz et al. 2024). These findings highlight the impact of on-site witnessing and embodied exposure in shaping traumatic memory. This dynamic parallels the implanted recollections experienced by the Voyager crew, emphasizing how first-hand or seemingly first-hand immersion, whether real or technologically induced, produces a far more potent and enduring form of remembrance.

An additional aspect of metamemorial science fiction is the way in which the massacre on the planet Tarakis reflected the real-world colonial system and its war-ridden consequences. Rather than relating to a single event and one location, the episode engaged the colonial condition. Star Trek’s representation of postcolonial or anticolonial perspectives has gained much scholarly attention throughout the years. These televised fictional representations have been criticized because, as observed by M. Keith Booker, “… the rhetoric with which the series declares the United Federation of Planets to be an anticolonialist enterprise is made problematic by its very connection to the taming of the American frontier, with its associated legacy of racism and genocide.” (Booker 2008, p. 196). Thus, although presented in a planet far (far) away from Earth, the events of the Memorial episode ‘metamemorialize’ historical colonial conditions on Earth: The flashbacks that the Voyager crew experiences tell of a forced evacuation of a colony and a partisan-like resistance group. And because the crew is placed in the position of the perpetrator, debates about the moral right to conquer and control the colony are raised. By positioning the crew in a situation they cannot accept morally, the anticolonial perspective is highlighted in the screenplay. The episode thus adopts an unusual digital memory route, one that engenders identification with the victims through traumatic self-criticality. As such, the episode contributed to current postcolonial debates, while proposing novel visual and textual means for creating identification—means that later materialized in digital commemoration projects. The episode thus represented a unique fictional counter-monument, as it questioned the authority of memory and—to use Young’s words—displaced memory (Young 1999, pp. 1–10).

An important visual aspect of both the episode and the Kan project is the use of mapping to present and explain conflict. In the Star Trek episode, the crew uses advanced mapping and digital scanning technologies to understand the flashbacks it is experiencing. As noted, when visiting the Kan website, the visitor is first introduced to an interactive map, from which he or she can select the locations where the 7 October massacre occurred. As argued by Paul Jaskot, who discusses contemporary digital platforms and websites that document historic atrocity events, advanced digital mapping and reconstruction of sites of atrocity make visible the spatial conditions that enabled violence. He interprets the role of such mapping as mainly allowing one to focus on recovering victim experiences and providing evidence for legal and social justice (Jaskot 2023, pp. 237–41). Kan 7.10.360 similarly uses mapping to understand individual experience and produce accurate evidence: one must select a locale on the map and decide which family house to click on. Temporal accuracy is added by the clock that enables retracing what happened to the victims on the day of the event. This is similar, to some degree, to the way Voyager’s crew experience the massacre on Tarakis—these are not merely names inscribed on a wall, or a conceptual monument—one must immerse himself or herself in the individual stories that are being presented, whether as an external observer (Kan), or as the so-called perpetrator of the event (Voyager).

In the Memorial episode everyday objects are presented as well. While in The Inner Light the flute and pendant visually memorialize positive experiences, the objects in Memorial play a different role—one more closely aligned with certain objects presented in the Kan project, which, as proposed above, derive from the functions of objects in physical and digital Holocaust displays. An additional dimension to that discussed by Hansen-Glucklich regarding such objects is provided by Laurie Beth Clark. In her analysis of mnemonic objects in memory culture, Clark examined how everyday items function differently in traumatic commemoration versus positive remembrance. The objects Clark examined in memorial sites created what she termed a “fundamental tension between a forensic impulse (which claims objects as evidentiary) and a rhetorical effect (whereby objects stand in for the dead or disappeared)” (Clark 2013, p. 156). These memorial objects—personal belongings, household items or clothing—work as metonyms that allow visitors to contemplate overwhelming trauma through manageable, familiar fragments. However, Clark argued that such objects are most effective not when they provide clear answers about violence, but when they “show us what we cannot fully know or understand” (Clark 2013, p. 156), forcing engagement with the complexity of historical trauma. The everyday nature of these items makes violence feel both more relatable and more disturbing by revealing how trauma invades ordinary life.

In one of his flashbacks in the Memorial episode, crewmember Kim encounters two Nakan people hiding in a cave trying to escape the massacre. Kim, who “participates” as an aggressor, shoots and kills them, exacerbating his traumatic memory. When returning to Tarakis as part of the attempt to relieve the crew of the painful flashbacks, Kim enters the real cave, recalling the event. He discovers the remains of the two murdered Nakan alongside everyday objects—a teapot perched on a burner and some plates (Figure 12). These are emphasized vis-à-vis the viewer by close-up shots. The objects are covered with cobwebs yet, placed on pedestals, they glow in dim light, rendering them reminiscent of a display or photograph of everyday objects in memorial museums.

Figure 12.

An item discovered by Kim and Tuvok in the cave, Star Trek: Voyager, “Memorial” (first aired 2 February 2000) (Source: Television still used for analytical purposes).

As discussed above, household and everyday objects found in the massacre sites in the Gaza Envelope were photographically documented and are presented on the 7.10.360 website. These objects accentuate the fact that many of those who were murdered, kidnapped or barely survived, were engaged in routine activities in their homes or military bases. Objects, both in the metamemorial science fiction plot of Memorial and in the 7.10.360 website, represent the trauma of survivors and the dead. As argued by Clark, these objects create an emotional response by accentuating a life that was lived, while enticing curiosity regarding the real or fictional event.

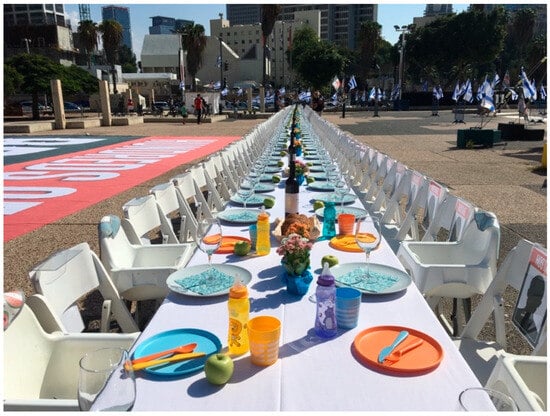

An additional interpretive dimension to the role of everyday objects can be gained by briefly addressing one of the physical commemoration sites of the October 7 massacre in Israel, which was located at the entrance square to the Tel Aviv Museum of Art and was largely dismantled in December 2025 (Dvir 2025). For over two years, this vast open outdoor space was repurposed as “the Hostages Square” through an ongoing memorialization process that involved temporary and permanent site-specific installations, performance art and activism apparatus (Roskies 2024, pp. 7–20). The centrally located urban commemoration site simultaneously served to increase awareness of the ongoing war and the suffering and demise that the Israeli and foreign hostages in Gaza underwent. The installations included, for example, a table surrounded by empty chairs, set with tableware for a festive Shabbat Dinner, and hence made use of a routine cultural practice to signify the absence of the hostages.11 During the first weeks of the war, children and babies were held hostages, and the table therefore included the everyday objects of children—infant feeding bottles and plastic utensils (Figure 13). Among the most powerful objects identified with commemoration of the murdered children was a stuffed pink elephant toy, held by baby Kfir Bibas in a photograph. Kfir was the youngest hostage, kidnapped when he was only nine months old, and murdered in captivity with his mother, Shiri, and older brother, four-year-old Ariel. Photos of baby Kfir and the elephant were displayed in the Hostages Square (Figure 14), and likewise, the photo of the kids’ toys in the attic where the Kleiman family hid (Figure 3), photos of bicycles of family members left in the yard, or open closets with children’s clothes, can still be viewed in the Kan digital project.12 The photographic documentation of toys that was displayed in the square and is still presented on the 7.10.360 website clearly reflect Clark’s observations: they serve as both evidence to the events and to children who are survivor-witnesses, as well as links to the murdered children.

Figure 13.

Shabbat dinner table installation representing hostages in Hostages Square, Tel Aviv, installed 20 October 2023. Photographed by Yossipik (photo source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shabbat_Dinner_table_representing_the_hostages_and_missing_people,_The_October_7_attack.jpg, accessed on 21 December 2025).

Figure 14.

Hostages Square Poster Board, Tel Aviv. To the left, photo of Kfir Bibas z”l (abbreviation used in Hebrew when mentioning the dead, stands for: ‘may his memory be a blessing’). Kfir holds his pink elephant. Photographed by Chenspec (photo source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kidnapped_Square_in_Tel_Aviv_-_Iron_Swords_War_2023_10.jpg, accessed on 21 December 2025).

Returning to Memorial and the 7.10.360 website, both raise a moral dilemma about commemorative responsibility. In Memorial, the memory implantation technology serves as an extreme form of immersive historical education, forcing visitors to become unwilling digital witnesses. This raises questions about consent in commemoration and whether the ethical burden of remembering atrocities can be justifiably imposed on others, even for preventing future similar events. In Star Trek, as noted, the crew of Voyager ultimately decides to maintain and repair the monument while installing a warning beacon for approaching vessels. The warning beacon in the Memorial episode, comparable to the Greek sorceress Circe’s warning to Odysseus against the Sirens, can also be read as metamemorial science fiction anticipating contemporary trigger warnings in social media and other online platforms. These digital trigger warnings, which often appear as textual landing pages, alert viewers to potentially distressing material and are intended to allow web surfers the agency in deciding whether to engage with traumatic content (Jones et al. 2020, pp. 905–17). Similarly, as described at the outset, the Kan project opens with a black landing page featuring a trigger warning and an introductory explanation of its aims (see Figure 1).

An additional important textual mediatory aspect is the idea of multilingualism in metamemorial fiction and contemporary digital commemoration. Globital memory is often multilingual, similar to the way counter-monuments employ an abstract design approach. These commemoration strategies encourage what memory scholars, cited above, view as enabling outsider participation and making each memory one’s own. Multilingual websites present an important opportunity of making commemoration of digital testimonies accessible, thereby contributing to diverse interpretations and adoption of memories by visitors. The Kan project offers English and Hebrew versions of the testimonies. Here, too, the science fiction of Memorial acknowledged the possibilities of multilingual mediation. The narrative presents the neurogenic pulses transmitted by the Nakan Memorial as adapting to the person or creature receiving them. The episode thus conceptually presents commemoration of conflict as accessible not just to those immediately connected to it—such as descendants or members of the same culture—but also to outside viewers. This is an issue that is central to actual contemporary digital commemoration projects.

Both the Voyager episode and the Kan project exemplify the commemoration of conflict using advanced technology and both engage in memory as a process. The Kan project is an ongoing documentation and publication process, as more information comes to light. The fictional events on the planet Tarakis occurred 300 years in the past, but the Voyager crew experience them as ongoing and memories are created gradually through the flashbacks, as throughout the episode more evidence is discovered and clarified. In addition, in both cases the memorial projects employ visual manifestations and digitized methods to mediate the atrocities. The obelisk-like monument on Tarakis, and the clock of Kan 7.10.360, which is central to the website, represent traditional spatial elements related to memory and time. Alongside them, the televisual neurogenic pulses of flashbacks in Memorial, as well as the mapped, textual and photographic documents on the Kan website, embody digital methods of commemoration and testimonies.

8. Conclusions

As of December 2025, 1430 books dealing with the 7 October Massacre and the ensuing, ongoing war and conflict have been published; internet websites documenting and collecting evidence have reached a volume of 40TB while photographic and voice testimonies, as well as tangible material, continue to amass in Israel and worldwide.13 A proliferation of artworks and literature have broadened this collection of facts, generating thought-provoking cultural production, some fictional and some that reflect personal reactions to the events (Mayer 2025). This includes television personae, such as French television presenter and producer Arthur Essebag, who recently published his book, J’ai perdu un bédouin dans Paris (Essebag 2025). All of these reveal a rich and varied array of commemoration techniques and mnemonic devices.

From the significant body of digital–visual projects included in these responses, we selected one website: the Kan 7.10.360 project. We examined it as a case study for digital commemoration within an ongoing conflict, particularly in a conflict zone. The project integrates digital and visual means to produce individual and spatial commemoration. The website’s powerful memorialization is grounded in the way that it transcends simple documentation, since it constitutes an ongoing archival endeavor that considers individual stories while employing tropes of spatial monuments and objects within a digital platform. Moreover, it invites commemoration through the process of discovery and digital witnessing, rather than a singular event or more typical website scrolling. The map, the clock, and the accompanying images and texts that guide the visitor’s journey through this site all relate to spatial and digital mnemonic techniques.

To understand this sensitive and significant project, we offered a metamemorial analysis of mnemonic and commemorative techniques through the Star Trek science fiction franchise. Broadly speaking, metamemorial fiction, which encompasses science fiction, offers an important arena for cultural exploration of memorial practices. As an arena that has explored atrocities, conflict and trauma—such as Levi’s stories relating to the Holocaust—metamemorial science fiction constitutes an important site for scholarly excavations of these issues. In the case of Star Trek, the series is counted among the most influential and popular science fiction series in television history. The series’ representation of fictional futuristic mnemonic and commemoration techniques thus contributes to ongoing discourses of commemoration. What will future technologies look like? This was a central concern mediated through the series’ set designs and plots. The visual form given to memorial technologies shaped the liminalities of personal and collective trauma and enabled the witnessing of past atrocities. Through alien memorials in particular, the franchise configured these structures as combining spatial monuments with digital technologies, anticipating globital commemoration that transcends nations and cultures.

The three episodes that we examined traced the show’s engagement with commemoration and historic atrocities from its first season in the 1960s, when the Holocaust was beginning to gain representation in American television, through the early 2000s, when post- and anticolonial perspectives impacted Western popular culture in general and the Star Trek franchise in particular. These episodes were discussed in relation to globital memory work, taking the Kan 7.10.360 project to demonstrate how Star Trek functions as metamemorial science fiction that relates to actual conflict, war and their commemoration. Our goal was not to argue that the Kan 7.10.360 project or other digital commemoration projects were directly inspired by the Star Trek episodes. Rather, we propose that the series, as metamemorial science fiction, contributes to cultural debates on globital commemoration. In Conscience of the King we analyzed Star Trek’s initial relation to the Holocaust in the series’ first season. We demonstrated the importance of understanding the connection of the series’ writers and producers to the War; and we discussed how the plot engaged the central role of witnesses, the pursuit of aggressors and the issue of acceptance of responsibility for crimes. In The Inner Light episode, emphasis was placed upon a specific family using images representing its multigenerational existence, objects symbolizing it and a screenplay and set design that highlighted memory technology—the probe—and its role in deciding what memory to preserve and how to preserve it. The episode allowed contemporary viewers to engage with individual stories and their memorialization. This focus reflected the personalization of memory work and its conception as structuring “ongoing connections with the deceased” (Arthur 2014, p. 152). As we have shown, such considerations significantly shape the 7.10.360 commemorative website, as the latter introduces family-centered images, personal texts that tell of the survivors’ lives, the final hours of those murdered, and objects representing their daily existence. Easily accessible through an interface that allows visitors to the website to choose their own memory path, the victims’ digitally commemorated experiences reflect “the intensely personal and painful” (Arthur 2014, p. 158) hours of the massacre, penetrating the visitors’ everyday lives. As noted at the outset, this is a key characteristic of digital memorialization (Arthur 2014, pp. 152–75). We further addressed the relationship between metamemorial science fiction, the Holocaust and its documentation, explaining how these mnemonic cultures are embodied and embedded in the design and conceptualization of the Kan website.

The episode Memorial further underscored powerful digital witnessing and an immersive experience. It staged images of war, a monument harboring memory technology, objects that represented the victims and a screenplay that underscored the role of an immersive, digitally induced experience in creating a deeply emotional and personal memory. This episode engaged significant aspects of the visual culture and memory technologies used to commemorate war and atrocities in conflict zones. As metamemorial science fiction related to the colonial condition, the episode engaged globital memory, representing the moral issues of war through personal identification and sophisticated digital documentation. Images of mapping the monument and deciphering it visualized the importance of physical memorials and their interface with the digital—similar to the maps and texts in the 7.10.360 website and anticipating them.

An important aspect of the discussion presented here is the underlying politics of the Kan 7.10.360 website. The website focuses on the events of the 7 October 2023 massacre and its Israeli and foreign victims, isolating the atrocities from the broader ongoing bloodshed that is the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. The website seeks to create a lasting visual and textual memory of a singular catastrophe of historic dimensions and implications—from the Israeli perspective. Its globital characteristics of representing personal suffering using the immediacy of digital photography and mapping, digitized records of mobile phone applications, and the construction of an interface that provides a choice as to how one navigates the website render it a digital counter-monument. As argued by Young with regard to counter-monuments, the participatory function afforded by the 7.10.360 website assigns “the burden of memory to the visitors [of the site] themselves,” in effect ‘forcing’ them to take on an active role (Young 1999, p. 9). This active role can be interpreted in numerous ways. It is here that the website resonates the concepts of metamemorial fiction as created in Star Trek episodes, wherein the characters had an active role in the creation of memory, albeit—as observed by Kapell—in various and opposed roles of victims and perpetrators (Kapell 2000, pp. 104–14). Moreover, the Kan 7.10.360 project exemplifies key aspects of digital memory making, bridging the gap between science fiction’s imagined commemorative futures and our contemporary digital reality, transforming ongoing trauma into accessible memorial experience.

Violence, conflict and destruction often construct the “bread and butter” of sci-fi cinema and television, often relating, as demonstrated here, to contemporary sociopolitical issues or events. Such screened works, Star Trek among them, function as cultural sites where moral questions and human experience during dire times are engaged through futuristic storytelling. However, as argued by Rhodes, “the importance of Star Trek is not always in the narratives it provides, it is in the way those narratives are delivered” (Rhodes 2017, p. 32). The way in which commemoration was mediated in the series positioned its characters as boldly remembering events through a deeply personal digital–virtual interface. These mnemonic technologies and modes of articulate memory work have been “delivered” along with the Star Trek vision. They have gradually materialized in the commemoration of war and atrocities, including the Israeli virtual commemoration of a conflict that took a fateful and tragic turn on the morning of 7 October 2023.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the research conducted for this study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this paper to our dear friends and colleagues Ronit Sultan and Yasmin Zohar. Ronit and her husband, Roland, were murdered in their saferoom on 7 October 2023 in Kibbutz Holit. Yasmin, her husband, Yaniv, and their daughters Keshet and Tchelet, were murdered in their saferoom in Kibbutz Nahal-Oz. The Zohar Family murder is documented on the Kan website and the Sultan couple’s is not. We wish to thank Alon Judkovsky for his reading and suggestions regarding cinema and television history and terminology. We also thank Esther Shalev-Gerz for providing further information on The Monument Against Fascism and for her insightful comments. Finally, we thank Lior Kleiman for approving the use of images from his home, destroyed in the October 7 massacre, and for generously sharing his family’s story with us. Limited use of GenAI has been performed. During the preparation of this study, the authors made limited use of Claude Sonnet 4 version for the purpose of English-language editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TOS | Star Trek: The Original Series |

| TNG | Star Trek: The Next Generation |

| Sci-fi | Science Fiction |

| WWII | World war II |