Abstract

The Fun Palace, a project initiated by Joan Littlewood and Cedric Price in 1961, exemplifies a pivotal transformation in the approach of cultural institutions toward their visitors. By centering on the audience experience, the Fun Palace signifies a departure from conventional institutional practices and represents a seminal example of unconventional art institution projects. This paper will examine the project, closely looking at the architecture, programming, and cybernetic structure of the Fun Palace. The purpose of this examination is to demonstrate how and why the ideas of Littlewood and Price predate the contemporary policies of institutions interacting with their audiences.

1. Introduction

In this paper, I will show that the Fun Palace, an unrealized project developed between 1961 and 1966 by a theater director, Joan Littlewood; an architect, Cedric Price; and a cyberneticist, Gordon Pask, is an important hub in institutional relations with the public. The Fun Palace represented a radical departure from the cultural institutions of the past, as it placed a premium on fostering active engagement in life, facilitating learning, and cultivating curiosity and critical thinking in its members. The visitors were expected to depart from the Fun Palace with a newfound conviction in their own intellectual aptitude and a transformation in their personal perspectives.

The Palace was supposed to be made of steel, more of a skeleton than a building, rough looking on the outside and designed to undergo continuous transformation to align with its users’ evolving needs and preferences on the inside. Cedric Price and Joan Littlewood envisioned its construction in London, specifically on the banks of the River Thames, within a residential district inhabited by working-class people, at a considerable distance from the West End theaters. Not intended to be a theater, it could, nevertheless, serve as one, should the people require that type of establishment. Instead, it was a multifaceted venue that could serve as a gallery, a radio, or a cinema, depending on the audience preferences.

The initial chapter of this study draws upon two methodological influences that have served as the foundation for the research: Donna Haraway’s speculative fabulation (Haraway 2016) and Mieke Bal’s concept of preposterous art history (Bal 1999). The chapter also provides a comprehensive literature review of the Fun Palace. Although the project was thoroughly discussed by scholars interested in modular and adaptable architecture, media theory, or cybernetics and mentioned as an inspiration for the Centre Pompidou building, the focus of this study, using Haraway’s method of reconfiguring existing knowledge, is to treat it as an important project in museum studies and show how its revolutionary approach towards shaping relations with audiences predates the change that was about to happen in the late 20th century.

The second chapter is dedicated to an examination of the Fun Palace’s program and architectural design. The chapter explores the alignment between Cedric Price’s concept of a flexible, modular building and the programming initiatives developed by Joan Littlewood for the institution. To better understand the motivations of the creators, I demonstrate how their approach to their respective disciplines developed and how these experiences shape the Fun Palace’s attitude towards its audience. A comparison of Price’s and Littlewood’s positions reveals a striking similarity, culminating in a revolutionary project of an institution that prioritized adaptability and a profound interest in its audience’s experiences over conventional values such as stability and expertise.

In the third chapter, I undertake a close examination of the software developed by Gordon Pask for the Fun Palace, focusing on his distinctive integration of cybernetics and conversation theory as means to offer the audience a good user experience. Until the present day, researchers have been unable to reach an agreement regarding the influence of Pask’s contribution on the viewers of the Fun Palace. The question remains as to whether the contribution would have diminished the viewers’ freedom to act or whether it was merely a convenient and necessary tool that allowed the building to achieve its desired flexibility. In this chapter, I proceed to reconstruct Pask’s stance on the intersection of arts and cybernetics. Pask’s perspective is evident not only in his conceptualization of the Fun Palace’s software but also in other projects, such as “Musicolour” and “Proposals for Cybernetic Theatre.” The articulation of Pask’s underlying perspective enables a more nuanced comprehension of the conceptual underpinnings of the Fun Palace’s cybernetic architecture, a prerequisite for examination of its relationships with the audience.

The Discussion focuses on demonstrating the correlations between the Fun Palace and contemporary attitudes concerning the manner in which institutions engage with their respective audiences. This discussion is divided into three distinct sections. The first one addresses the formation of museums’ interest in their audiences, beginning in the 1960s and becoming an increasingly prominent feature in the late 20th century. The second is devoted to exploring the influence exerted by the Fun Palace on the Centre Pompidou. This analysis will focus on two main aspects: the architectural aspects of the buildings and the ideological aspects of the institutions’ mission and programming.

An examination of the Fun Palace’s legacy in the 21st century allows for a more nuanced understanding of contemporary art institutions and the continued relevance of the 1960s concept of empowering the public to manage their own cultural experiences within current institutional frameworks. The third section of this chapter will address the institutional contexts in which the Fun Palace resurfaced in the 21st century. This will include a 2004 conference on the future of Palast der Republik in Berlin and a more recent example of The Shed, a New York-based cultural institution with architecture and programs that are directly inspired by the Fun Palace. The subsequent segment of this section examines the participatory shift in museum practices, which has led to a greater prevalence of public involvement in programming.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Methods

This paper, a case study of Joan Littlewood’s and Cedric Price’s Fun Palace and its influence on contemporary art museums and their relations with the public, is both a speculative fabulation (Haraway 2016) and an exercise in writing a preposterous history of institutions (Bal 1999). Employing Bal’s concept of non-linear history, which posits that both the past and present can influence one another, I will explore a new thread in the history of museums, reconfiguring existing knowledge to concentrate on their ways of engaging with the public.

This study draws upon a review of the extant literature on the Palace. The project has been meticulously designed to align with the needs and preferences of its visitors, guided by the principle that visitors possess a unique understanding of their own needs and expectations. A comparison of said concept with the evolution of audience research, which commenced in museums in Europe and North America in the mid-1960s, facilitates the reconfiguration of knowledge consistent with Donna Haraway’s postulate in Staying with the Trouble to pursue a nebulous thread, to compose an alternative history from established facts. While Haraway’s primary focus has been on the history of science, her methodological approach has found successful application in various disciplines, including pedagogy (Truman 2018) and cultural studies (Chaberski 2020).

“Plucking out fibers in clotted and dense events and practices” (Haraway 2016, p. 3) is a strategy of examining the history and present of art museums that reveals new patterns and threads in the fabric of institutional history. Haraway’s perspective, which highlights the importance of science fiction as “a way of patterning possible worlds and possible times” (Haraway 2016, p. 31) and the importance of staying in the present—or, as she prefers to call it, “staying with the trouble”—was crucial to my attitude toward the presented material. This article does not attempt to present a counterfactual history—an account of what would have happened if the Fun Palace had been built—but rather examines the agency of an unrealized project in changing the way institutions interact with their audiences and rearranging the existing version of museum studies. This fabulation enables me to incorporate the Palace into the history of art institutions and view it as a significant node in the narrative.

As Sarah Truman notes, Donna Haraway’s way of thinking is based on facts. Yet, speculative fabulation “defamiliarizes and queers perception, disrupting habitual ways of knowing” (Truman 2018). The speculative fabulation I propose results from three aspects the Fun Palace had: its modular, changeable architecture, designed by Cedric Price (Price 1965; Mathews 2005, 2007; Dal Co 2016); its program, shaped by Joan Littlewood and influenced by Erwin Piscator’s political theater of the 1930s (Piscator 1978); and its cybernetic software, established by Gordon Pask in accordance with his conversation theory (Pask 1969, 1971; Pickering 2010; Yiannoudes 2016).

A Fun Palace is a speculative fabulation (SF, in Haraway’s terms) as well and it could be referred to as a version of different SF Haraway is interested in: as a science-fiction project. Despite the passage of 60 years since its development, the modular architecture guided by a learning software with a perpetually evolving program continues to be an ambitious endeavor, arguably bordering on the impossible. What Littlewood and Price tried to construct in London is not only an actual building, but a change in organizational paradigm: an institution no longer interested in passing on knowledge, but in learning from its audience. The present study aims to develop this speculative fabulation further, contributing to the field of museum studies by establishing the Fun Palace as a significant source.

This a-linear attitude is a shared feature of Haraway’s method and Mieke Bal’s concept of preposterous art history, which constitutes an additional methodological inspiration for the present project. A distinguishing feature of her approach is the attitude toward temporal position, which she considers not as a limitation that theorists must overcome, but rather as a situation conducive to a more nuanced interpretation of the works presented.

In her seminal book Quoting Carravaggio: Contemporary Art, Preposterous History, Mieke Bal explores the interconnections between contemporary art and the oeuvre of Caravaggio. Rather than focusing on the impact of Caravaggio’s influence on contemporary artists, she acknowledges reciprocity between their works and the critical perception of Baroque art. Bal notes that the issue of contemporary perspective conditioning our view of older works has been raised repeatedly by researchers, especially literary historians. Accordingly, artists such as Dotty Attie, Ken Aptekar, and David Reed, who are cited by the author, are understood as not merely quoting Baroque works, but rather as providing new interpretations of the source materials.

Bal compares the mechanism of preposterous art history to Freud’s concept of delayed action, or Nachträglichkeit (Bal 1999, p. 9). As Ruth Leys notes, this term refers to the development of trauma and assumes that the process occurs between two events, neither of which must be traumatic. The first event occurs in early childhood. Because the individual lacks the tools to understand it, the event is forgotten. Only after the second event, which occurs later in life, does the earlier event become “remembered” and become a source of trauma (Leys 2000, p. 20).

Bal advocates abandoning this rigorous Freudian interpretation. Although she believes that preposterous art history links two events, she argues that the connection between them is two-way. The source of the quotation is not forgotten. On the contrary, the quoter consciously and actively refers to earlier works, and the practice of quotation allows us to rethink the original. In psychoanalytic terms, writing a preposterous history of art can be compared to a therapeutic process in which the original event is recognized, and the relationship between the past and future is clearly defined.

Although the Fun Palace has been more of a footnote than a crucial part of the history of art museums, it has resurfaced in the 21st century. The “non-building,” conceived by Price and encouraging public participation, is mentioned as an inspiration for projects such as The Shed in New York (Davidson 2016), and was the topic of a 2004 conference at the Palast der Republik in Berlin that discussed the future of an unwanted relic of a bygone era (Frieze 2005; Bernau et al. 2005). Contemporary interpretations of the institution’s program emphasize the importance of audience-driven experiences, paving the way for participatory museums in the 21st century and redefining institutions as agents of societal change.

2.2. Literature Overview

The scholarship surrounding the Fun Palace project emerges at the intersection of several fields—experimental architecture, theater, cybernetics, and media studies. Although these bodies of literature generally develop in disciplinary isolation, they converge on a shared set of concerns regarding the redistribution of agency within cultural institutions, the shifting expectations placed on audiences, and the possibility of conceiving spaces that respond to the behaviors, desires, and rhythms of their publics.

The texts devoted to Cedric Price’s architectural practice form the backbone of existing research. Stanley Mathews’s (2005, 2007) comprehensive historical analyses emphasize Price’s early critique of modernist determinism and his pursuit of an architecture grounded in openness, provisionality, and the suspension of authorship. These studies show that the modular steel structure proposed for the Fun Palace is not an isolated experiment, but rather a crystallization of Price’s wider conviction that spatial form should emerge from use, not precede it, expressed by the architect himself (Price 1969; Obrist 2009). In this paper I will be using these texts on architecture to understand how modularity and adaptability of the building were used to plan a different experience for the Fun Palace public.

Francesco Dal Co (2016) extends this view by tracing the project’s afterlife in the Centre Pompidou, where the ethos of flexibility first articulated by Price became embedded in the architectural language of major cultural institutions. A concise but important addition comes from Tanja Herdt (2019), who interprets the Fun Palace through the emerging information age: using a hardware/software analogy, she frames the project as a flexible program animating an indeterminate structure and highlights the tension between the ideal of open-ended user autonomy and the cybernetic mechanisms proposed to manage participation. Herdt’s reading underscores the project’s ambivalence, situating it at the threshold between emancipatory possibility and informational control.

A second body of literature situates the Fun Palace within the history of experimental and politically engaged theater, foregrounding Joan Littlewood not simply as Cedric Price’s collaborator but as the project’s conceptual engine. Nadine Holdsworth’s (2006) study of Littlewood’s practice significantly deepens this context: tracing her work at the Theatre Workshop, Holdsworth shows how Littlewood consistently rejected hierarchical modes of theater-making in favor of collective authorship, improvisation, community engagement, and an insistence that performance emerge from the lived experiences of its audiences. Her method of devising—open, porous, and radically inclusive—positioned the spectator as a co-producer of meaning. From this perspective, the Fun Palace appears as a logical expansion of Littlewood’s earlier work: a spatial and organizational extension of her long-standing commitment to social activation, vernacular creativity, and the redistribution of cultural agency. This will be a critical component in the examination of the intended Fun Palace program mechanism for inspiring visitors to engage in the creation of their own cultural experiences.

A third body of texts focuses on the cybernetic dimension of the project and on Gordon Pask’s role as its third author. Studies by Lobsinger (2000), Mathews (2007), Pickering (2010), and Yiannoudes (2016) demonstrate the extent to which Pask’s conversation theory and his earlier artistic experiments, such as Musicolour, informed the project’s operational logic. Rather than interpreting the use of sensors, punch cards, and adaptive algorithms as a mechanism of constraint, these authors emphasize the reciprocal nature of Pask’s (1969, 1971) systems, which his texts described in detail: the environment was expected to learn from its users, and users, in turn, were expected to reshape their own actions in response to the environment’s adjustments.

The system’s reciprocity, however, is not without its critics: Mathews’s reading of Pask as an advocate of subtle social control stands in stark contrast to Lobsinger’s interpretation that foregrounds the open-endedness of cybernetic exchange. The central tension between the promise of unrestricted user freedom and the cybernetic mechanisms proposed to coordinate participation is also noted by Herdt (2019), framing the Fun Palace as a project both visionary and inherently ambivalent. The tension between these positions remains one of the unresolved questions in the literature and points to broader anxieties about technological agency in cultural spaces.

Taken together, these bodies of literature demonstrate the extent to which the Fun Palace resonates across disciplinary boundaries, even if it is seldom treated as a project capable of unifying them. What remains consistently underexamined is the Fun Palace as a cultural project whose meaning cannot be reduced to architecture alone but must be located in the interplay of media, activism, theater, technology, and institutional experimentation. By drawing these sources into dialogue it becomes possible to see the Fun Palace not simply as a visionary object but as an anticipatory model for a flexible, visitor-centered, and self-reflective cultural institution—one whose ideas would reappear, transformed, in the museological and architectural paradigms that emerged in the decades that followed.

To create a background for the speculative fabulation of the Fun Palace’s impact on museum studies, I decided to incorporate into my research a body of works on changing relationships between art museums and their viewers. Starting with the sociological investigations of Darbel et al. (1966), which mark a decisive break by demonstrating that museum audiences are not a neutral public but a socially differentiated one whose access to aesthetic pleasure depends on prior cultural competencies. Early Canadian experiments in public surveys reveal a growing institutional concern with audience research (Abbey 1969). Theoretical reflections from the late 20th century (Wright 2006; Weil 2007) explicitly articulate this shift: museums move from being custodians of objects to facilitators of interpretation, from spaces “about something” to spaces “for somebody.” Within these texts, participation becomes not a peripheral activity but a criterion for institutional legitimacy.

Recent literature traces the Fun Palace’s afterlives in twenty-first-century cultural discourse, noting how its rhetoric of flexibility and participation is frequently invoked but inconsistently realized. Debates around the redevelopment of the Palast der Republik (Frieze 2005; Bernau et al. 2005) positioned the project as a model for experimental institutional forms, even as policymakers showed little appetite for its radical openness. Similar tensions appear in Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s The Shed, where Price’s principles of modularity and adaptability, to which authors refer (Davidson 2016), are formally adopted but reframed within a commercially driven cultural economy Parallel discussions in museum studies—most notably Simon’s (2010) The Participatory Museum and subsequent work by Sitzia and Elffers (2016), Jagodzińska (2017), and Cruickshanks and van der Vaart (2019)—show that participatory ideals have been implemented in different museums, yet are still often constrained by curatorial authority and institutional structures. Collectively, this scholarship reveals how the Fun Palace’s language of openness and public agency has been adapted to contemporary contexts in ways that simultaneously echo and limit its original ambitions.

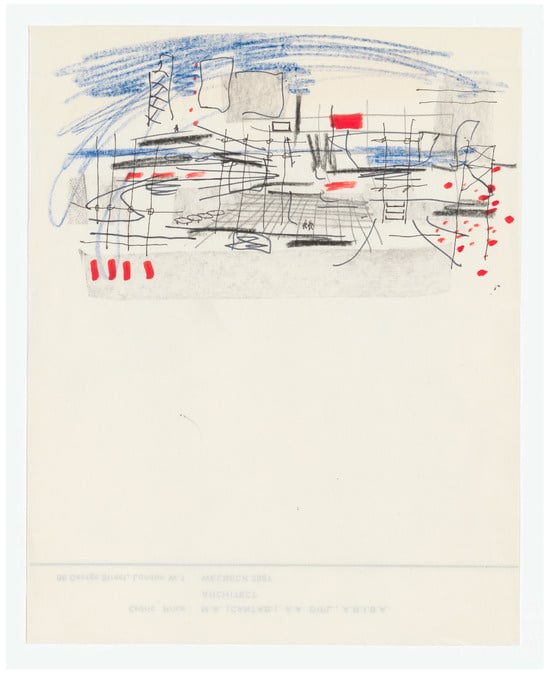

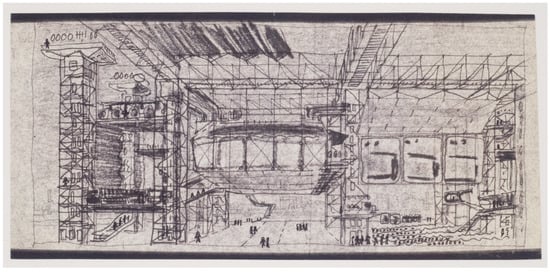

3. Architecture and Program

The contemporary term “Fun Palace” serves to collectively denote the array of methods for the dissemination of a set of ideas conceived by Joan Littlewood, Cedric Price, and subsequently Gordon Pask between 1961 and 1966. The collection includes architectural drawings, some of which were published as early as 1965 (Price 1965), DIY models, a film (see Herdt 2019, pp. 55–72), pamphlets, written statements (Littlewood 1964), and minutes from meetings of various committees responsible for developing the concept (see Mathews 2005). The project continuously evolved since the initial phase, characterized by a rudimentary sketch in red and blue created by Price in 1963 (Figure 1). This was followed by the development of intricate technical drawings in monochrome, intended for presentations during meetings with the local community at the venue selected for the project’s physical construction (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Cedric Price, Perspective sketch of Fun Palace, 1963? Cedric Price fonds. Canadian Centre for Architecture, © CCA.

Figure 2.

Cedric Price, Interior perspective for the Fun Palace, ca. 1963. Cedric Price fonds. Canadian Centre for Architecture.

What they all conveyed was Price’s notion that the structure’s appearance should evolve over time. The architect opted for a flexible structural design, incorporating a substantial open space at its core, encircled by cubic steel scaffolding. The design called for the installation of overhead cranes, which would facilitate the moving of prefabricated elements intended for use as walls, floors, and ceilings. The cranes would allow the visitors to modify the structure in accordance with their present requirements, thereby facilitating the creation of new rooms, enlargement of existing rooms, and reduction in rooms according to necessity.

Per Price’s initial plan, the fundamental structural unit was to be a cubic scaffolding with sides measuring 18.3 m in length. The entire structure was designed to occupy a space of 219.6 m in length and 109.8 m in width. The design of the building, which featured no walls, was conceived to facilitate access from all directions at all times.

The drawing that Joan Littlewood saw in early 1963 was not particularly evocative; its shape resembled Constant’s conceptual sketches for New Babylon, combining elements of abstract painting with technical drawing. The structure, whose primary construction elements were vertical grids, is distinctly delineated against the sky, which has been marked in blue crayon. The architectural sketch indicates the presence of an open space at the center of the building, with vertical structures surrounding it. Two human figures, placed in the center of the design, give an idea of the scale of Price’s concept: the floor, sketched in perspective foreshortening, is roughly the size of a football pitch.

Price asked Frank Newby, with whom he was concurrently working on an aviary for London Zoo, to accompany him with the construction. Although the final design met all of the architect’s requirements, the publicly presented structure was designed by the engineer. Newby decided to make a slight alteration to the proportions, increasing the length of the sides of the rectangular base from 12 by 6 cubic scaffolds to 14 by 6. The new design called for a structure measuring 237.7 m in length and 109.7 m in width, with an undeveloped interior measuring 201.1 m in length and 73.2 m in width, to be covered by a membrane roof. The conceptual framework entailed the use of two overhead cranes, strategically positioned along the perimeter of the inner rectangle, to facilitate the creation of additional rooms within the confines of the structure. This innovative system was designed to ensure the seamless transportation of necessary components to any desired location in the building, thereby enhancing its functionality and adaptability.

Price’s Fun Palace was not a multifunctional building; it was more of a skeletal structure that permitted construction of any necessary rooms. The distinguishing characteristic of the structure was rooted in a premise that the originators held less insight regarding the users’ needs than the users themselves. The fundamental premise of the Fun Palace concept revolved around the notion that visitors would adopt the role of experts on their own leisure time, while being entrusted with the responsibility of determining the architectural form of the building. The raw steel frame, which constituted the skeletal structure, was designed solely to provide the requisite tools to facilitate movement within the space. The surrounding cubes were intended to contain lifts and escalators.

The structure, conceived by Price and Newby, functioned as a prominent emblem of the institution’s program, a subject that was addressed by the architect and director. The structure was supposed to be open, flexible, and easily adaptable to the requirements of the audience. This adaptation process was a continuous and ongoing endeavor. Price further elaborated his conceptual framework underpinning architectural design in other projects. In his practice, he prioritized the users of his designs, and his architectural solutions were occasionally radical, primarily due to the absence of any alterations in the nature of the space. In 1999 he was invited to participate in a competition for designing the future of western Manhattan. Notably, he was the only participant to propose that nothing be built in the small strip of empty space above the Hudson River. The Lung for Midtown Manhattan project was conceived as a means of introducing fresh air into the densely developed city center. The initiative aimed to provide New Yorkers and visitors with opportunities to enjoy outdoor spaces, offering vistas of the city skyline and the river. In contrast to the other participants in the competition, who were renowned architects from around the world, Price proposed a solution with the potential to improve the lives of residents (Obrist 2009, pp. 59–60; Muschamp 1999).

A salient theme in Price’s designs was the recognition of change as an integral part of life. In his interpretation, architecture became a means of thinking about people and their needs rather than a set of construction solutions. Stanley Mathews has observed that Price’s persistent criticism of conventional architectural practices contributed to the enhancement of the field by accentuating, among architects and within society, unproductive modes of conduct and thought. He derived great satisfaction from proposing non-architectural solutions to architectural problems, as he did not subscribe to the notion that buildings were an appropriate remedy for every situation (Mathews 2007, p. 41).

While Cedric Price was working on the design of the building for the new institution, Joan Littlewood began work on its program. The inaugural text devoted to the Fun Palace was published in 1964 in New Scientist. The document did not include any specific program proposals or practical information regarding the necessary equipment, anticipated staff, or rules for using Price’s flexible structure. The emphasis was consistently placed on the prospective users of the Fun Palace and the potential positive impact of its use on their future. In the introduction to her article, the director noted:

Politicians and educators, talking about increased leisure, mostly assume that people are so numb or servile that the hours in which they earn money need be made little more than hygienically bearable, while a new awareness is cultivated during the hours of leisure. This is to underestimate the future. Those who at present work in factories, mines and offices will quite soon be able to live as only a few people now can: choosing their own congenial work, doing as much or as little of it as they like, and filling their leisure with whatever delights them. (…) In London we are going to create a university of the streets—not a ‘gracious’ park but a foretaste of the pleasures of 1984. It will be a laboratory of pleasure, providing room for many kinds of action.(Littlewood 1964, p. 432)

Littlewood’s text, in conjunction with public appearances of both creators (see Mathews 2007, pp. 148–51), functions as a manifesto for a novel approach to art, thereby disrupting the modernist dichotomy between low and high culture. The Fun Palace was conceived as a space where disparate fields, including science and art, politics and mass media, sporting events and poetry evenings, could coexist on equal terms. A century prior, social reformers in Great Britain regarded museums as a solution to the prevailing issues of folk entertainment, which was often associated with excessive alcohol consumption and marital infidelity (see Bennett 1995, pp. 20–22).

Price and Littlewood’s institution did not differentiate between activities such as reading the latest world news, cheering the favorite sports team on, engaging in gossip, or attempting to create art through painting. The Fun Palace was designed to facilitate autonomous development, function as a comprehensive learning platform, and serve as a tool for self-assessment of one’s situation. Additionally, it was conceptualized as a catalyst for societal transformation.

This motivation was most clearly articulated when Littlewood described how the theater section, the field with which she was most intimately familiar, would function. The proposed acting area was supposed to provide therapeutic benefits to individuals from diverse backgrounds. Factory workers, shop employees, and office personnel, who find themselves disengaged from their daily routines, would have the opportunity to engage in the reenactment of incidents from their personal experiences through different registers of theater. This was intended to facilitate a shift in their passive acceptance of external events, prompting them to awaken to a critical awareness of reality (Littlewood 1964, p. 362).

This principle, which was demonstrated in the domain of theater, appears to regulate the operation of the Fun Palace: a structure that was to be reconfigured daily to suit the requirements and aspirations of the individuals who frequented it. This issue arises from the inherent challenge of predicting the various activities that could occur within the building. Most individuals invited to contribute to the conceptual framework possessed distinct, personal visions, which made constructing a clear, cohesive vision even more challenging. The veracity of this claim is proved by the comprehensive compendium of 70 projects for the Fun Palace, which was meticulously catalogued in 1964 by John Clark, a distinguished figure in the domain of psychiatry and a member of the Cybernetic Committee. He was also a pivotal contributor to the group tasked with formulating the institution’s program. The concept encompasses a diverse array of artistic and technological elements, including “art machines” and “galleries of colored panoramas,” alongside “flying people,” “mazes of silence,” and the “Tower of Babel” (Mathews 2007, pp. 274–75).

The conceptual underpinnings of Price’s modular, transformative architecture and Littlewood’s abstract program (refined with the assistance of project-affiliated committees) are rooted in a shared fundamental principle. The Fun Palace’s initiators prioritized the users, aiming to empower them to proactively manage their leisure time. Their institution was supposed to be a place of acquiring and honing new skills, learning to think critically and community building.

To add a footnote to this preposterous institutional thinking, I would like to add that this conceptualization of cultural institution roles might have been novel to the art museum, but it has been a prevailing feature in various cultural domains, particularly in theater, for nearly three decades. The tradition of German political theater, as exemplified by Erwin Piscator, was characterized by its commitment to confronting the audience, who were eager to participate in a more active role, often engaging in disputes and singing the “Internationale” alongside the actors. This approach led to the creation of “total theater,” a concept that blurred the conventional boundaries between the audience and the stage, a departure from the more rigid distinctions found in classical theater.

Piscator implemented the multi-level reform of theatrical events, which involved the introduction of current news and other elements of political and social reality into performances. On a formal level, the following elements were incorporated: film projections accompanying the actors on stage, a functional rather than decorative set design, and music as a fully fledged element of the performance. According to British critic and scholar Graham Holderness, Piscator worked in various registers of theater, preparing both agitprop plays performed outside the institutional theater and costly productions created on subsidized stages. The concept of “total theater” emerged from the confluence of these experiences, which, in equal measure but in different ways, activated the audience, encouraging them to participate more fully in the performances (Holderness 1992).

Although there is no evidence of Joan Littlewood reading The Political Theatre, Piscator’s seminal book about his view of onstage politics and developing a new kind of theatrical institution in interwar Berlin, this tradition of thinking was present in her own practice as a director. Born into a working-class family, Littlewood did not receive a conventional theater education, leaving the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA), where she had been awarded a scholarship, in protest against the institution’s pedagogical approach. Instead, she focused her creative energies on producing for the residents of London’s East End and Manchester, demonstrating a clear preference for practical, community-oriented theater over the abstract theories of continental theater (Holdsworth 2006).

Littlewood’s upbringing in an area marked by significant social unrest, including strikes and hunger marches, instilled in her an early commitment to socially engaged theater, leading her to reject classical academic training. Following her departure from RADA, the future director relocated to Manchester, where she engaged in professional collaboration with the local BBC branch. It was during this period that she became acquainted with Jimmy Miller, who initiated her into the realm of working class propaganda theaters, which were affiliated with the Workers’ Theatre Movement.

In 1934, in response to the political situation in Europe, Miller founded his own troupe, the Theatre of Action, which Littlewood soon joined. Following their expulsion from the Communist Party due to the avant-garde, formal nature of their performances, the duo proceeded to establish another group, Theatre Union, at the conclusion of 1935. Among the theatrical productions they mounted was The Good Soldier Švejk, which was translated into English from its German original and based on the 1928 Berlin production by Piscator. The German director’s staging, which incorporated a revolving stage segmented into sections on which Švejk traversed via a moving belt, served as a direct point of reference for emerging British artists (Holdsworth 2006, pp. 1–42).

Miller’s interactions with Brecht and Littlewood’s engagement in intellectual discourse within left-wing theater circles, coupled with her interest in audience analysis, rapidly guided her toward formal solutions that resembled those employed by Piscator. This approach is exemplified by the 1940 production of Last Edition, which employed film projections to stage the text, integrating bibliographical research with the most recent war reports.

She engaged with Theatre Workshop audiences as collaborative partners, considering their contributions to the performance. In his posthumous memoir, director Richard Eyre articulated that while she held writers in high regard, she exhibited a certain disregard for the “text” itself. She subscribed to the notion that the action and dialogue on stage should not be permanently fixed and presented in an unchanging form. She believed in the “atmosphere of a specific event,” which also included encouraging the audience to interrupt the performance and the actors to respond. This approach, postulated by Brecht, was an active form of alienation that remained absent in his practice.

In this context, Littlewood’s involvement in the Fun Palace appears not as a digression from her theatrical practice but as its logical extension. The project translated her long-standing commitment to audience activation, collaborative authorship, and socially grounded performance into architectural and organizational form. By bringing the principles of political theater—its documentary immediacy, fluid boundaries, and insistence on public agency—into dialogue with Price’s adaptable architecture and Pask’s cybernetic thinking, the Fun Palace proposed an institution structured around participation rather than spectatorship. This continuity between early twentieth-century theater and late 20th-century spatial experimentation highlights the project’s enduring relevance and reinforces the need for an interdisciplinary lens capable of grasping its full conceptual scope.

4. Fun Palace: Cybernetics

Joan Littlewood shared a fondness for audience members who interrupted performances and were ready to shout their comments from their seats with Cedric Price. The framework proposed by Price did indeed allow for audience intervention. However, the rough steel skeleton he designed left several unanswered questions. Chief among these was: who would decide what the building should look like at a given moment, and on what basis. The question of how the structure would be controlled is equally pertinent. What solutions should be implemented to ensure that the process of shaping the rooms does not excessively distract visitors?

In the spring of 1963, Littlewood and Price requested the assistance of Gordon Pask, who provided specific answers to the questions. Pask, the founder of System Research, was a seminal figure in the field of cybernetics in Britain. He is perhaps most notably known for his trailblazing book, An Approach to Cybernetics, which was first published in 1961. Pask’s intellectual interests were extensive, encompassing a wide range of fields including medicine, theater, and psychology. His decision to participate in the Fun Palace project was influenced by prior familiarity with the Littlewood Theatre Workshop’s work. As Stanley Mathews notes, Pask rapidly emerged as the third author of the Fun Palace concept. It was his version of “software” for Price’s design that enabled a practical realization of Littlewood’s vision. The solution he proposed, akin to the building’s architecture, prioritized functionality, thereby ensuring that Pask’s work remained imperceptible to the intended user (Mathews 2005, p. 86).

Another significant contribution of the cyberneticist was the establishment of the Cybernetic Subcommittee, which brought together supporters of the project. The subcommittee’s members included other cyberneticists, such as Stafford Beer, a pioneer in the use of cybernetics for social management, and Robin McKinnon-Wood, Pask’s partner at his firm, System Research. The team was also joined by politicians such as Tom Driberg and Ian Mikardo, historians, psychologists, doctors, visual and theater artists. While it was not the sole committee involved, as another group concurrently sought to devise activities for the Fun Palace, it unquestionably exerted a powerful influence on the evolution of the Fun Palace concept. Stanley Mathews underscores the pivotal role of regular meetings among members in fostering their substantial engagement in formulating solutions for Price’s building. It was they who developed specific, practical proposals, published in 1964, with a clear division of possible types of activities into six zones.

This division, which was not included in Price and Littlewood’s original concept, necessitated the development of software to ensure the self-control of the Fun Palace. Pask’s proposal entailed the implementation of a control system that was to be based on sensors. The sensors would be responsible for transmitting data regarding visitors, their numbers, and their movements to a central computer. The computer, using a punch card system to analyze the information in real time, was tasked with determining the optimal transformation of the space. Mathews provides a thorough description of the operational mechanisms of this system. The punch card system, a technological marvel of its era, was designed to record and allocate the resources necessary for the execution of diverse activities. The center of the card was intended to be punched with a record of specific activities, while the outer holes contained data on the size, location, quality, and frequency of the activity. The second system recorded and allocated resources, including televisions, communication needs, noise levels, acoustic requirements, lighting levels, electricity consumption, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (Mathews 2005, p. 86).

However, for this to be feasible, the empty space between the steel towers had to be subdivided. The initial hypothesis of complete freedom proved impossible to implement. If the radical openness of the Fun Palace, as discussed by the director and architect in early 1963, was to be maintained, potential users would have to be able to quickly learn how to assemble rooms from prefabricated elements using overhead cranes. Therefore, prior to a visitor’s participation in a pantomime that facilitates the exploration of their personal perspective on the monotony of quotidian life, they would have to move a few walls using cranes or settle for the existing infrastructure. The members of the Cybernetic Subcommittee determined that it would be better to impose partial limitations by establishing zones that would group similar proposals, thereby simplifying the users’ experience in navigating the building (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

de Burgh Galwey, photographer, Fun Palace: interior perspective, 1964. Cedric Price fonds. Canadian Centre for Architecture © CCA.

The first zone encompassed teaching machines, that is to say, a variety of mechanized methods for knowledge transfer and skill development. These ranged from recorded lectures that disseminated scientific achievements to games that fostered perceptiveness (developed by Pask’s company, System Research) and the observation of quotidian life in industrial, agricultural, and medical settings. The second zone was dedicated to the exploration of new forms of expression. Littlewood’s theatrical experiences, which combined avant-garde form with political engagement, were undoubtedly formative for this concept. In this setting, workers were expected to cultivate a critical perspective on reality through the enactment of scenes from their personal experiences. The third zone was designated for the presentation and production of films, offering individuals the opportunity to rent small cameras and engage in the practice of directing. The fourth space was designated for scientific experimentation, the fifth for artistic pursuits such as painting and sculpture, and the sixth for musical performances.

Roy Ascott devised an additional cybernetic system that complemented Pask’s proposal. His “Pillar of Information” was designed to make it easier for visitors to use the building by employing a search engine. For instance, an individual interested in painting could use the display to find out where classes of interest were taking place at a given moment. However, in accordance with Pask’s approach, Ascott conceived a system that functioned not only as a mere information source, but also as an autonomous entity capable of acquiring and processing user behavior data. Using the history of previous searches carried out at the Fun Palace, it could suggest other, unexpected activities that visitors might not be aware of. Ascott was among the first to propose the use of a computer to search a large database. He also developed a structure for linking information that was subsequently employed by the creators of the World Wide Web (Mathews 2005, p. 89, for more about Ascott’s further cybernetic project see Ascott 2007).

Upon initial observation, the solutions devised by the Cybernetic Committee and Gordon Pask may appear to have contributed to a diminution in the freedom of action within the Fun Palace by means of spatial structuring. The integration of a division into zones dedicated to analogous activities, in conjunction with the utilization of a computer to adapt the layout of the rooms according to users’ needs, appears to be associated with control and the provision of tailored solutions to visitors, while expecting them to adapt to these solutions. In order to comprehend the underpinnings of Pask’s proposed solutions, which, despite their ability to impose order on the chaotic system delineated by Littlewood and Price, are rooted in analogous assumptions, it is imperative to examine his inaugural cybernetic endeavors within the domain of art. Despite having received his formal education in the scientific field, his interest in music, theater, and the visual arts accompanied him throughout his adult life.

Pask became interested in cybernetics after meeting Norbert Wiener, the founder of this scientific discipline: while studying at Cambridge, he was assigned the task of looking after a visiting professor. During their conversations, he became convinced that it was in the field of cybernetics where he could most effectively pursue his interests. Specifically, he sought to simulate the learning process and use electronics to recreate the nervous system. In doing so, he hoped to determine how machines could learn (Pickering 2010, p. 313). His inaugural projects in this field entailed the development of a specialized apparatus, the “Musicolour” stage lighting system, in collaboration with Robin McKinnon-Wood.

The machine processed input data from a microphone, as programmed by Pask, illuminating the stage where the performer stood in real time. The auditory stimuli were directed towards filters responsible for recognizing different frequencies, which subsequently activated the lighting system. This created a synaesthetic experience, immersing audiences in a vibrant auditory and visual environment. Andrew Pickering has noted the system’s singularity, wherein lights are not definitively allocated to particular frequencies. Instead, the machine “listens” to the music and contextualizes the sounds.

During a concert featuring the machine, the same melody could be visualized in different ways, depending on which part of the piece it was in. A significant element, not only for “Musicolour,” but also for Pask’s concept of art reception, was the potential for audience involvement in the operation of the stage apparatus. If the performer were to improvise in response to the audience’s behavior, the task of “Musicolour” could be described as visualizing the atmosphere in the room. The designers operated under the assumption that the microphone would collect music; however, the presence of loud sounds from the audience, such as applause or whistles, would likely have an effect on the lighting.

Pask’s machine was capable of both learning and being trained; when professional musicians used it and observed the reaction of “Musicolour,” they were able to arrive at the desired effects by slightly altering the piece they were playing. Pask’s research focused on the adaptive capabilities of machines, leading him to design “Musicolour” to exhibit “boredom” and render its operation contingent on external factors. If a performer returned to a particular motif too frequently, the machine did not reiterate the visual sequence but rather ceased reacting to it. This created an incentive for the musician to make changes.

A brief analysis of the “Musicolour” system illuminates the fundamentals of conversation theory, a seminal contribution of Pask’s to the field of cybernetics. According to his understanding, the objective was to establish a system in which two participants could exert influence over each other, and the solutions they devised were collectively shared and could not be ascribed to either individual. The participants in such a conversation could be biological organisms as well as machines or works of art. In consideration of the subject matter of this paper, the most salient question in this context appears to be: on what basis, according to this concept, can a dialogue between the viewer and the image be established? In a text published several years after the completion of the Fun Palace, Pask expounds his theory of art as follows:

It is clear that an aesthetically potent environment should have the following attributes:(a) It must offer sufficient variety to provide the potentially controllable variety [in Ashby’s terms] required by a man (however, it must not swamp him with variety—if it did, the environment would be merely unintelligible).(b) It must contain forms that a man can learn to interpret at various levels of abstraction.(c) It must provide cues or tacitly stated instructions to guide the learning process.(d) It may, in addition, respond to a man, engage him in c.(Pask 1971)

It is therefore clear that, for Pask, mutual, creative shaping is also possible between subjects who do not engage in actual conversation. As Pickering explains, according to this concept, the process of conversation between the viewer and the image can be based on internal processes (Pickering 2010). The viewer, by interpreting, changes his or her own perception of the canvas, while the image has the opportunity to change someone’s way of thinking and show a new perspective. The integration of zoning and data-driven decision-making computers into the Fun Palace project could be interpreted as a means of controlling users and, in a literal sense, programming the institution. However, Pask’s comprehension of cybernetics and his approach to art suggest an alternative interpretation.

The steel structure on the banks of the Thames, like other artistic projects by the cyberneticist, was designed to influence its audience while being shaped by them simultaneously. The analysis of incoming information could be used to improve the building’s operation, but at the same time it also built up the computers’ “knowledge” of audience behavior patterns. The proposed solutions to the spatial organization of the building would be derived from the user’s prior decisions regarding activities they select and the subsequent navigation of the space. These decisions would serve as a basis for the placement of prefabricated elements within the designated area.

Another of Pask’s projects created with Littlewood, Proposals for a Cybernetic Theatre (1964), also operates according to the principles of conversation theory. The inspiration for it came from a discussion between two representatives of the American First Nations on a reservation, held one evening after a screening of a western, during which one of them said, “Yesterday, I was already hoping we would win.” The 30-page document developed by the cyberneticist described a system that could form the basis for a new kind of theater, consisting of a set of scenes directed by the audience. This experiment, which could be undertaken by the Theatre Workshop, would involve identifying pivotal moments in the narrative and enabling the audience to determine the fates of particular characters with whom they identify. The audience’s choices would be recorded through a voting system involving buttons. The basis of the Pask proposal was the institutionalization of the figure of the spectator bursting onto the stage, for example, to prevent Romeo from consuming the poison before Juliet awakens (Pickering 2010, pp. 349–50; Littlewood 2001, pp. 760–61).

The notion that the narrative structure of a theatrical production, a sculpture showcased in a museum, or even a musical improvisation could not only exert an influence on viewers but also be subject to their influence during the interpretive process was a fundamental tenet of Pask’s theoretical framework. His cybernetic works, including “Musicolour,” Proposals for a Cybernetic Theatre, and “Colloquy of Mobiles,” developed for the exhibition Cybernetic Serendipity, demonstrate Pask’s contemplation on the integration of art and cybernetics, particularly the role of the viewer in this combination.

This important issue is also addressed by Socrates Yiannoudes, author of a book on the influence of computer technology on architecture:

Pask’s cybernetic mechanisms were modeled on second-order cybernetics. This was an information discourse proper to the emerging post-industrial society and knowledge-based economy, which Price wanted to anticipate. In the context of second-order cybernetics, observers are inseparable from the system being observed (the machine) and with which they interact, configuring and reconfiguring their goals dynamically. Observer and observed participate in open-ended reciprocal exchanges—what Pask called conversation, a cybernetic concept that runs through all of Pask’s work, both applied and theoretical.(Yiannoudes 2016, p. 29)

This aspect renders the controversies surrounding the contemporary assessment of Pask’s role in developing plans for the Fun Palace all the more surprising. In his texts, Stanley Mathews repeatedly accuses the cyberneticist of wanting to turn Littlewood and Price’s project into an experiment in social control (Mathews 2005, pp. 73–76; 2007, pp. 83–85). In Mathews’s understanding, Pask’s system becomes an oppressive tool of control, and its goals—including determining what could make visitors happy (Mathews 2007, p. 84)—are reduced to attempts to manipulate individuals. A primary concern articulated by the researcher pertains to the utilization of the terms “unchanged” and “changed” by Pask to describe visitors at the beginning and end of their visits, respectively. If we were to agree with the scholar’s assertion, it would be difficult to consider the Fun Palace as a project aimed at the emancipation of museum visitors.

The aforementioned texts on the role of art in conversation theory demonstrate that, despite Pask’s utilization of the concept of control, among others, his objective was not to develop a first-order cybernetic system (see Lobsinger 2000).1 His initiative strove to develop a program capable of autonomously managing the building and adaptively aligning with the evolving requirements of its users. The development of the Fun Palace was not initiated as an experiment designed to produce a system that would compel viewers to adhere to the objectives of the programmer. While Pask’s writings emphasize the transformative experience of the viewer within the architectural space, an examination of his artistic theory reveals that comparable transformations can occur in the context of traditional museum or theater visits. It was his belief that an environment with great aesthetic potential was supposed to shape people, while remaining under their influence. Since individuals became part of the system for a moment (as pointed out by Yiannoudes, among others), they could not leave this experience exactly the same.

Tanja Herdt’s paper offers a noteworthy argument concerning the concept of control. In 1965, members of a Cybernetic Subcommittee articulated a necessity to establish a hierarchical structure within the audience. A select group of Fun Palace attendants would be eligible for benefits, which would be contingent on their frequency of attendance and their “overall performance” (Herdt 2019, p. 91). A different committee proposed the implementation of a social observation program for Fun Palace users. The aforementioned information contributes to the overall ambivalence regarding the project’s cybernetic components and its implementation of the principle of freedom, which is intrinsic to the Fun Palace concept.

It is also important to recognize that contemporary assessments of Pask’s contribution are inevitably shaped by our lived experience within data-driven environments—systems that routinely infer behavioral patterns and use them to guide, predict, or monetize human action. From this vantage point, it becomes difficult to regard the Fun Palace’s proposed “software” with the optimism and innocence characteristic of early cybernetic thought. Technologies such as data sorting, user profiling, and adaptive feedback loops carry very different connotations today: they evoke infrastructures of surveillance and modulation rather than pure conversational reciprocity. Even if we grant that Pask intended the system to engage visitors in an open-ended exchange—an environment that learns in order to support self-expression rather than to constrain it—the question remains of what would happen to the traces of those interactions. A system that “keeps score” could, in principle, be used not only to assist users but also to shape their behavior. While I do not align myself with Mathews’s more skeptical reading of Pask as a proponent of subtle social control, it is crucial to acknowledge that many of the tools he envisioned have, in contemporary contexts, become integrated into apparatuses of monitoring and behavioral management.

These concerns resonate strongly with ongoing debates in museum and institutional studies around participation, agency, and the ethics of designing visitor experience. If institutions define the parameters of engagement, do they genuinely expand public freedom, or do they simply multiply the available options within a pre-structured framework? In the 21st century—when audience segmentation, target groups, and outreach strategies have become routine components of museological practice—participation can also be instrumentalized as a marketing tool, signaling openness without necessarily enabling more experimental or unconventional modes of engagement with collections and exhibitions. The tensions visible in the Fun Palace’s cybernetic ambitions thus continue to echo in contemporary discussions about how institutions shape, invite, and delimit the agency of their publics.

5. Discussion

5.1. Focusing on the Audience

Understanding the evolution of museums’ approaches to their audiences is essential for grasping the intellectual climate in which the Fun Palace was conceived—and for recognizing why its proposals were so radical. The 1960s marked the moment when art institutions first began to investigate their publics systematically, adopting sociological and statistical tools to map who visited museums and why. These early studies revealed deep inequalities in cultural access and demonstrated that aesthetic appreciation was not an innate capacity but a learned skill shaped by education, class, and familiarity with artistic languages. At precisely the same time, Price, Littlewood, and Pask were formulating the Fun Palace as an alternative cultural model—one that refused the museum’s hierarchical assumptions and instead imagined a space in which users could experiment, learn, and co-create without prior cultural qualifications. By situating the emergence of institutional audience research alongside the Fun Palace’s ambitions, we can see more clearly how the project responded to, exceeded, and reimagined the debates of its moment. The following historical overview therefore serves not only as background but as a framework for understanding the specific problem the Fun Palace sought to address: how to construct a cultural environment genuinely shaped by its users rather than merely studied, measured, or managed by institutions.

The evolution of the museums’ approach towards their audience can be traced back to the 1960s, a period that witnessed a concurrent interest in audience engagement from both visionaries and museum professionals. The advent of institutional transformations was accompanied by the integration of statistical and sociological research methodologies within art museums. The first large-scale research in this area was conducted in 1965 by Pierre Bourdieu, Alain Darbel, and Dominique Schnapper in European art museums. The primary interest of French sociologists was to identify a correlation between the educational attainment and socioeconomic status of the public and the frequency of museum visits. This pioneering work demonstrated that the appeal of a given institution to visitors is influenced not only by the quality of its collection, but also by the manner in which the narrative is presented (Darbel et al. 1966).

Since the late 1950s, Duncan F. Cameron and David S. Abbey, members of the Canadian branch of the International Council of Museums, also conducted audience research. In 1967, the team undertook a study of the public’s attitudes toward contemporary art. While the study centered on museum programming, the survey was conducted using a representative sample of the region’s residents, not exclusively among museum visitors. The results of the questionnaire interviews, which focused on the perception of works of art, were subsequently discussed by the International Council of Museums and published in the ICOM journal Museum (Abbey 1969).

The above studies employed different methodologies and were conducted for different reasons. The questionnaire prepared by the French team was completed independently by museum visitors. The Canadian experiment entailed the curation of 23 sets of cards with reproductions, each set depicting contemporary artworks (selected by a team of museum professionals, curators, and art historians) and containing 10 images linked by a single theme. The respondents, under the supervision of the interviewer, arranged the images in order of preference, from those they liked the most to those they liked the least. Approximately 30% of respondents in specific sets assigned the highest rating to the same card, and these were most often figurative, realistic works. Notably, abstractions and cubist works received consistently low ratings, with the paintings of Léger, Feininger, and Mondrian receiving the lowest scores (Abbey 1969).

The initial studies on museum audiences, spearheaded by the team of French researchers, sought to ascertain the social conditions under which art can operate. It was hypothesized that art can only resonate with viewers and provoke a positive response if they understand it. To test this hypothesis, discussions were initiated with the institution’s audiences. The researchers posited that the capacity to experience aesthetic pleasure is an acquired skill, emphasizing the institutional conditions that facilitate this learning (Darbel et al. 1966). By posing inquiries regarding the demographic of museum visitors and the popularity of specific artistic creations among viewers, we can extrapolate similar conclusions from the Canadian and French studies.

The investigation’s focus on audience interest and their attitudes towards art yielded findings that did not bode well for museum professionals. Despite the institutional efforts to attract new viewers, the exhibits and narratives presented required prior training, which may have discouraged some potential attendees. The experience of contemporary art, shaped by evolving modes of representation, remained largely inaccessible to the general public. It was primarily limited to a select few who possessed the necessary education and had been exposed to art through prior generations. Concepts such as Price and Littlewood’s Fun Palace or Hultén’s Kulturhuset were instrumental in formulating a novel paradigm for cultural education. This paradigm encompassed not only the presentation of works of art of historical or cultural significance, but also the cultivation of critical viewers. In the latter half of the 20th century, in order to comprehend the works on display, viewers required knowledge not only about the changes taking place in art itself, but also about cultural and technological phenomena.

The implementation of increasingly large-scale studies, such as those conducted in European institutions by Bourdieu, Darbel, and Schnapper, indicates a growing interest in the study of audiences and the social embeddedness of art museums. In 1969, the Ministry of Culture, Recreation, and Social Work of the Netherlands commissioned an audience research study, and in 1971, the Federal Republic of Germany followed suit (see Hudson 1975, pp. 172–76). The German research was initially carried out by commercial operators; however, the growing importance of statistical research is demonstrated by the fact that a decade later, the Institut für Museumsforschung, the world’s first institution dedicated to audience research and the publication of museum statistical yearbooks, was established in Berlin. These trends precipitated the establishment of marketing and advertising departments in the 1980s (see Reeve and Wollard 2019, pp. 67–68). The mounting significance of attendance statistics necessitated heightened competition for visitors.

However, it is important to acknowledge that the initial interest of art institutions in audience research was predominantly quantitative in nature. The concepts of granting viewers agency or empowering them to make decisions regarding their participation in the museum program were not implemented as swiftly as the introduction of statistics. Thinking of visitors not only as a group that should be encouraged to use museum services as often as possible, but as people who can shape the institution’s program (in accordance with cybernetic conversation theory—just as the program shapes them), proved to be more complicated than introducing advertising specialists to the museum team.

Twenty-five years after the publication of Bourdieu, Dardel, and Schnapper’s findings, Philip Wright authored a chapter on the relationships between museums and their audiences in The New Museology. This text illuminates a multitude of systemic deficiencies and shortcomings, analogous to those previously delineated by a team of French researchers. Wright’s primary accusation against museums was that they primarily catered to a pre-qualified, educated audience that did not require explanations regarding the order in which paintings were hung or the selection of specific objects from the collection. He accused exhibitions of attempting to show an “objective” history of art, i.e., one that does not problematize its own position, the Eurocentric shape of the narrative, and the lack of representation of art from other cultures, ethnic minorities, or works by women (Wright 2006).

Wright’s observations highlighted the intricate nature of museums’ interdependencies, stemming from both historical and contemporary factors. These dependencies have a profound influence on the formation of collections and the subsequent presentation of these collections to the public. A comparison of the methods of presentation in private galleries and public institutions was made, and it was noted that what is effective in a commercial context has undesirable effects in museums. An explanation is that laconic descriptions devoid of contextual information work well when a work of art is the subject of a transaction, not education. The viewer’s ability to derive enjoyment from a visit to the museum hinges upon their comprehension of the exhibited works. This encompasses not only the recognition of mythological and Old Testament stories, but also the familiarity with Cubist forms (Wright 2006).

Wright’s critique is rooted in the notion that the function of a museum has evolved beyond the mere acquisition and preservation of a collection. Instead, the primary responsibility of a museum has come to be regarded as the facilitation of a dialogue between the exhibited objects and their viewers. The institution is not only a repository for works of art of the highest caliber; it is also an active agent in the acquisition of cultural competencies. It is the institution’s fundamental responsibility to foster engagement with art, a process that, as French sociologists have demonstrated in their research, is only possible when art is accessible to the viewer.

During the latter half of the 20th century, a transformation began to take place in museums around the world. This transformation can be summarized by the title of a text by Stephen E. Weil: from being about something to being for somebody (Weil 2007). While the unrealized London project may not have directly influenced subsequent generations of museum curators, its impact can be seen in the architectural design of Piano and Rogers and its ideological resonance with Hultén’s Kulturhuset. The Fun Palace can be regarded as a catalyst for a shift in the way visitors perceive their roles and the possibilities offered by cultural and art institutions. From disciplined and educated audiences for whom a visit to an art museum was supposed to be a privilege (Hudson 1975, pp. 8–30), viewers became partners—without them, the institution’s activities would be pointless.

5.2. Fun Palace and Centre Pompidou

Despite the fact that the Fun Palace was never constructed, Price did not shelve his designs. This unrealized concept proved to be of great significance for Price’s career as an architect, with his sketches serving as a source of inspiration for succeeding generations of architects (Dal Co 2016, p. 45). The architectural plans for the Fun Palace were published in magazines (see Price 1965; Landau 1985), and Price himself discussed these designs during his talks at the Architectural Association, where he lectured on an occasional basis until 1964. The Fun Palace, much like the concepts of Archigram or Superstudio’s Architettura Interplanetaria, did not require physical construction to exert its influence on architecture.

It is unclear whether Richard Rogers encountered the plans for the Fun Palace in the press or learned about the project during meetings at the Architectural Association, of which he was also a member. It is reasonable to conclude that the architect, a contemporary of Price, must have closely examined this project. Following the dissolution of Studio 4, the architectural firm he operated with his wife, Su Rogers, and Norman and Wendy Foster, in 1967, he began working with Renzo Piano. Two architects, not widely known at the time, submitted a proposal for the Centre Pompidou, one of the most prestigious architectural competitions of the era. Their submission, inspired by the Fun Palace project, emerged a winner. The primary intention underlying Piano and Rogers’s design was to ensure that the spatial configuration within the building could be adapted to evolving needs.

A comparison of the unique architectural design of the French museum with Price’s preliminary sketches reveals striking formal parallels, including the exposed steel framework, the clearly delineated façade divisions, and the external communication structures. Francesco Dal Co has noted similarities between the interior designs of the two. Specifically, he has highlighted the floor panels, wrapped in a transparent material, as a point of convergence between them. These movable floor panels echo Cedric Price’s Fun Palace, highlighting a shared emphasis on adaptability and interactivity in modern architecture. The configuration of the building was such that each floor was to be open, with free space in the middle and utility and technical rooms located on the sides (Dal Co 2016, p. 73). These visual analogies, however, may obscure crucial distinctions. The British project constitutes an open-air structure, only partially covered by a roof, while the French museum inverts the structure of a conventional building, showcasing the skeleton, ventilation systems, electrical and plumbing installations, and other components that typically remain concealed.

Of even greater significance, however, are the ideological affinities: the conviction, inherent in the design, in the adaptability of the contemporary institution and its needs, as well as the synonymous application of the terms “play” and “education.” This observation is particularly noteworthy in the context of Price and Littlewood’s seminal contributions to Piano and Rogers, as highlighted by Francesco Dal Co (2016, p. 45). This notion is further elaborated by Dal Co, who underscores the pivotal role of visitors’ autonomy in determining their own experiences.

The Centre Pompidou was conceptualized by Georges Pompidou as a nexus for diverse domains of science and art. This singular building was designed to serve as a multifaceted cultural institution, encompassing a museum of contemporary art, a library, a cinema, a theater, and lecture halls. In addition, it featured institutions dedicated to design and contemporary music. This architectural complex was designed to foster interaction and collaboration among these diverse forms of artistic and cultural expression. Visitors and users of the institution could partake in a variety of activities that diverged from those available in the disciplining museums of previous eras (Hulten n.d.).

Despite the numerous instances in which the architectural similarities between the Centre Pompidou and the Fun Palace have been emphasized (see Buchanan 1983; Landau 1985), it is important to note an unexpected similarity in their respective programs, despite their separate origins. Prior to Pontus Hultén’s relocation to France to assume the role of the inaugural director of the Paris museum, he served as the director of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. At that time, with a newly constructed building in the city center in mind, he developed a vision for an institution not too dissimilar from what Littlewood had conceived a few years earlier. In conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist, he placed particular emphasis on the audience’s role in this project:

In 1967, we were engaged by the city of Stockholm to undertake a project at Kulturhuset. The participation of the public was to be more direct, more intense, and more hands-on than ever before, that is, we wanted to develop workshops where the public could participate directly, could discuss, for example, how something new was dealt with by the press—these would be places for the criticism of everyday life. It was to be a more revolutionary Centre Pompidou, in a city much smaller than Paris.(Obrist 2014, p. 45)

Kulturhuset, which was originally conceived as a combination of a museum, laboratory, studio, and workshop, similar to Price and Littlewood’s vision, was not realized according to Hultén’s idea. The building, with its glass façade bearing resemblance to the Pompidou’s, was inaugurated in 1974. However, it featured a wholly distinct program. Nonetheless, the curator himself underscored the fact that it was precisely this project that led him to conceptualize the Paris museum. Kulturhuset and Fun Palace were constructed according to remarkably similar principles; both were designed to provide users with the means to engage actively in culture. Both institutions were to offer the public an opportunity to use technologically advanced equipment to allow users to understand the impact of technological development and mass media on reality.

The museum evolved from a disciplining space, defined by numerous rules and restrictions, whose primary objective was to safeguard the collection, into an institution designed with the viewer in mind. It transitioned from a state of separation from everyday life to one that facilitates comprehension of the underlying rules that govern it. Projects such as Hultén’s Kulturhuset and the Fun Palace have been identified as contributing factors to this phenomenon.

5.3. The Fun Palace’s Influence in 21st Century

More than half a century after its conception, the Fun Palace continues to haunt contemporary discussions about the role, form, and social obligations of cultural institutions. Its core propositions—flexible architecture, user agency, interdisciplinary experimentation, and the dissolution of traditional hierarchies—remain compelling precisely because they were never fully tested in practice. What survives instead is a set of ideas that institutions repeatedly invoke when imagining new futures, even as the realities of policy, economics, and cultural politics constrain their implementation. Reconstructing how these ideas are mobilized today allows us to assess not only the enduring appeal of Price, Littlewood, and Pask’s vision, but also the persistent tensions between radical cultural ambition and the institutional structures that attempt to contain it.

At the beginning of the 21st century, the Fun Palace resurfaced within the context of institutional discourse concerning the future of the Palast der Republik in Berlin (Frieze 2005). The conference was part of Urban Catalyst, an EU project developed by Phillipp Misselwitz, Phillipp Oswalt, and Klaus Overmeyer to examine different strategies for temporary use of leftover sites. While the potential outcomes of the Palast’s transformation are not pertinent to the subject of this paper, it is crucial to examine the reasons behind the Fun Palace’s reference. The idea put forward by Price, Littlewood, and Pask served as an example of a laboratory for cultural innovation, a place where revolutionary ideas about what culture is could be developed.

However, even among the architects and urbanists in attendance at the conference, the majority concurred that the notion of establishing a revolutionary cultural institution would not be of interest to policymakers (Bernau et al. 2005, pp. 131–45). They could not be more right: the demolition of Palast der Republik was completed in 2008 and 2020 marked an opening of a reconstructed baroque Berlin Palace in the same location.