Abstract

This article concerns nōsatsu, also known in Japanese as senjafuda and generally known as “votive slips” in English. Nōsatsu emerged in the 18th century out of popular practices related to pilgrimage in the city of Edo. Nōsatsu practitioners who visited Buddhist temples or Shinto shrines would paste votive slips on walls or other surfaces in the belief that the pasted slip would function as a proxy for the pilgrim, continuing in prayer vigil after the pilgrim had left. Practitioners persisted in their pasting activities in the face of opposition from temples and shrines. Later, nōsatsu evolved into full-color pictorial woodblock prints meant for exchanging and collecting, rather than pasting, but the early history of pilgrimage, proxy devotion, and institutional resistance remained in both the memories of the practitioners and the iconography of the slips themselves. Through close visual analysis of several slips depicting Buddhist themes, this article will describe the attitude of transgressive devotion that characterizes nōsatsu culture.

Keywords:

nōsatsu; senjafuda; votive slips; Japanese Buddhist art; Edo period; pilgrimage; play; Nichiren; hell; ukiyo-e; woodblock prints 1. Terms of Devotion: Introduction

This essay concerns the phenomenon of nōsatsu 納札, a word usually translated as “votive slip”. These votive slips began, in the eighteenth century, as small strips of paper that devotees would paste on walls or other surfaces at shrines and temples; later, they evolved into privately commissioned woodblock-printed slips that were exchanged among collectors. The nōsatsu phenomenon thus involves a social dimension (practices related to both religious pilgrimage and hobbyist collecting) and a material dimension (the slips themselves, both those meant for pasting and those meant for exchange). While nōsatsu are still comparatively little understood in both Japan and the West, both the social and the material aspects of nōsatsu culture have recently received attention in both Japanese and English.1 This essay will, instead, largely concentrate on the material aspects by offering close readings of the imagery in several exchange slips from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. My overall goal is to show how the early social practices of nōsatsu bequeathed to later nōsatsu culture an ambiguous attitude toward institutional religion, particularly Buddhism, and that this attitude was frequently expressed in both the pictorial content and the formal aspects of votive slips. Through my close readings, I will argue that nōsatsu display what I call “transgressive devotion”, simultaneously celebrating and subverting the objects of their ostensible faith.

The first three sections of this essay seek to familiarize the reader with the broader nōsatsu phenomenon through examinations of selected exchange slips;2 the remainder of the essay will further explore the dimensions of nōsatsu’s transgressive devotion by examining, not single slips, but large assemblages of slips. Nōsatsu’s peculiar origins have resulted in a modular approach to their design that lends itself to the construction of visual narratives, while simultaneously allowing collectors to resist or ignore the prescribed narrative at will. The very format of nōsatsu seems to encourage both sincere and playful engagement—transgressive devotion.

A good way to begin to understand nōsatsu is by examining the words used to identify them, beginning with “nōsatsu” itself. Of the two elements in this word, the second, satsu 札 (also read fuda), refers to a small piece of paper, often with writing on it (the same satsu is used for paper money). The first element, nō 納, derives from the verb osameru 納める, which can mean “to donate”, with the idea being that the slip is something to be donated. As will be discussed below, votive slips are indeed bestowed upon temples and shrines—although these institutions are usually unwilling recipients of the donors’ largesse. Nevertheless, nōsatsu are conceived of as representing an act of religious devotion, as well as embodying this devotion in paper form.

The other common term by which these slips are known in Japanese, senjafuda 千社札,3 also connotes devotion. It means “thousand shrine” slips, a reference to the multitude of Shintō shrines to the harvest god Inari 稲荷 found in the city of Edo 江戸 (later Tokyo), and to the pilgrimages that connected them—pilgrimages that provided an occasion to deploy votive slips. Here, it is important to note that despite the close association between votive slips and Inari worship, from their beginnings at the turn of the 19th century, senjafuda have been equally concerned with both Shintō and Buddhism (Takiguchi 2008, pp. 12–13).

As noted at the outset, a sense of play is inseparable from nōsatsu, both as a practice and as artifacts; this extends to the artifacts’ treatment of religious subjects, whether gods or Buddhas. However, this essay will argue that it is in the use of Buddhist imagery that nōsatsu most fully express their complicated attitude toward institutional religion, the flippant yet sincere way in which the pilgrims who commissioned votive slips presented them as unwanted offerings at temples and shrines. Even slips that were never meant to be presented as offerings often express a sense of transgressive devotion, a faith that honors religious orthodoxy in the breach—that, in fact, commemorates the breach as evidence of faith.

2. In One Ear and out the Other: Votive Slips in Theory and Practice

In this section, I will examine one particular votive slip that captures both the practice and theory of nōsatsu culture, particularly as it relates to Buddhism. The slip in question is Figure 1, datable to circa 1857 (Ansei 安政 4) and designed by Utagawa Yoshitsuna 歌川芳綱 (dates unknown; fl. ca. 1850s).4

Figure 1.

Untitled votive slip by Utagawa Yoshitsuna, 1857, depicting pilgrims pasting votive slips on the head of a giant Buddhist icon. Japanese votive slip (nōsatsu) collection (NE1184.35.N67_v.45_037a), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries.

The print is large and square, about thirty centimeters by thirty, and the pictorial surface is dominated by a massive bronze Buddha head. We know the head is enormous because it dwarfs the twenty-four human figures in the frame. The scale of the icon is suggestive of the Great Buddhas of Nara 奈良 or Kamakura 鎌倉, the fifteen-meter-high Vairocana at the Tōdaiji 東大寺 and the over thirteen-meter-high Amitābha at the Kōtokuin 高徳院 in Kamakura. But its expression—a distinct, if somewhat vacant, smile—corresponds to neither. And indeed, given how small the human figures appear, it seems to be even larger than either. We may be meant to understand it as an imaginary greater-than-Great Buddha, rather than a real-life icon.

This is just as well, because the twenty-four human figures are interacting with it in ways that range from irreverent to comically blasphemous. In the center, one man has seated himself comfortably on the Buddha’s lips, from which perch he is hailing a friend below. Another man stands on the Buddha’s lips and appears to be gazing into the Enlightened One’s cavernous nostril. One man stands on the upper edge of the Buddha’s right eye, looking up, while another crouches on the left eye, peering into the gigantic pupil. There appears to be a line of men crawling into the Buddha’s right ear and more emerging from his left, suggesting a tainai meguri 胎内巡り or womb tour on a scale even more prodigious than that offered by the Kamakura icon.5 All of this, not to mention the ladders propped unceremoniously against the ears and lips, suggests less a party of pilgrims than simply a party.

And the crowning amusement is what we see taking place at the top of the image. A pair of men on the top left, perched amid the Buddha’s curls, are holding a long strip of cloth, at the end of which another man dangles head-first over the icon’s forehead, reaching toward the gold circle representing his byakugō 白毫 (Skt. ūrṇā; the auspicious mark on the Buddha’s forehead); another man is already there, seated in a looped strip of cloth held by invisible comrades on the other side of the Buddha’s head. What are these two men up to, aside from daredevil climbing? A hint is provided by the wooden box hanging at the seated man’s waist. Similar boxes can be seen elsewhere in the print, with the most telling example being the one at the far right, just above the Buddha’s left ear. These boxes contain votive slips, and the men holding the boxes are preparing to paste slips on the surface of the icon itself.

As depicted in this print, votive slips meant for pasting are small strips of paper containing a name and often a simple design or logo. The slips are privately commissioned by aficionadoes; the name and logo on the slip belong to the commissioner. The logo often represents a group to which the commissioner belongs, a club of fellow nōsatsu enthusiasts, while the name is usually a pseudonym chosen for use in nōsatsu society. Aficionadoes affixed these strips to walls, gates, and other surfaces at temples and shrines in the belief that the slip would function as the paster’s proxy, keeping a prayer vigil long after the paster had returned home. This is why the name or pseudonym of the commissioner/paster—known as a daimei 題名—is the one indispensible element of a nōsatsu: it is what enables the slip to function as a worshiper’s proxy. Of course, popular religion in the Edo period often included an element of play, and nōsatsu pasting was no different.6 Devotees organized themselves into clubs and turned the act of pilgrimage into a pleasure excursion; pasters vied with each other to leave their slips in the most hard-to-reach spots, where they would be most likely to escape being removed by temple or shrine personnel—who often regarded the practice as noxious graffiti (Takiguchi 2008, pp. 39–42).

The print shows pasters in flagrante delicto. The man on the Buddha’s left ear has laid a slip atop his box and is applying paste to its back with a brush. He may be about to hand it to the man next to him, who is using a long-handled brush to apply another slip to one of the Buddha’s curls. Other pilgrims have done the same—in total, the Buddha’s head is festooned with thirty-two votive slips, each with the name or pseudonym of a different aficionado. The men crowding in on the Buddha’s byakugō may be about to add more slips. Meanwhile, a man seated atop the Buddha’s right ear is about to add his name to the collection in a different way. What at first glance might appear to be a pipe is in fact a brush—an early variant of votive slip practice involved eschewing the medium of printed paper and writing one’s name directly onto one’s chosen spot, as here.

What at first glance appears to be simply a lot of men climbing around on a Buddha head thus turns out to be a somewhat more organized activity: a votive slip pasting excursion. Many of the men have pasting tools or are assisting others who do. And even those who do not at first appear to be engaged in pasting are in fact implicated in it, as the writing on their hats, parasols, and banners does not consist of the spiritual mottoes one might expect but are in fact more daimei. All twenty-four of these men might be part of the same votive slip club, and the thirty-two slips7 already decorating the Buddha might belong to members of the same club, as evidenced by the diagonal red stripes that function as a unifying mark on so many club-made slips.

There is another way in which Yoshitsuna’s print relates to votive slip pasting, a way that is only apparent to a viewer familiar with nōsatsu. The print itself is a votive slip, although it looks nothing like the slips being pasted onto the Buddha.

As the playful dimension of nōsatsu culture developed over the course of the nineteenth century, slips became collectors’ items. Aficionadoes would exchange them with one another, first in ad hoc encounters and then in dedicated meetings where clubs would get together and trade their slips. Ultimately, slips came to be commissioned especially for exchanging and collecting, which encouraged the graphic design elements to flourish. Slips came to boast more elaborate calligraphy, or pictorial elements in full color. While commissions remained private and personal, professional woodblock print artists and artisans were enlisted to design and execute slips. By the mid-nineteenth century, nōsatsu for exchange could be seen as miniature ukiyo-e 浮世絵, displaying all the thematic, artistic, and technical sophistication of their more famous commercial cousins.

And they were not always miniature. Nōsatsu became standardized at roughly 15 cm in height and 5 cm in width, but designs came to encompass more than one slip. Sometimes slips were made in series, with a variety of designs meant to correspond to others in the same series. And sometimes a single design was made to spill across multiple slips, resulting in nōsatsu that rivaled or exceeded standard ukiyo-e in size. These elaborate and capital-intensive slips were never pasted except in scrapbooks, but, crucially, they retained the elements that allowed them to function, at least in theory, as nōsatsu. Even the most pictorially minded slips still contained commissioners’ pseudonyms. And even the largest of slips were measured in multiples of the standard-sized pasting slip; usually, the black frames of the putative single slips comprising the design were allowed to protrude as if from beneath the superimposed illustration.

Just such frames can be seen at the edges of the Yoshitsuna print. Due to the way the print was pasted into a scrapbook, its single-slip frames are not as distinct as in some other examples, but one can still make out that this print comprises twelve single slips in two rows of six. (A single slip is counted as a chō 丁; this print would be described as twelve chō in size).

This means that the entire print is itself a large votive slip, commissioned jointly by the members of a nōsatsu club, whose pseudonyms appear on the slips within the slip. Those pseudonyms perform a dual role: within the scene depicted, they represent the names of the people who pasted them, or who are pasting them. For example, the slip currently being pasted by the man with the long-handled brush standing on the Buddha’s left ear bears a pseudonym that presumably belongs to him or his companion—or both, since the third character is ren 連 or “group”, the term often used for a nōsatsu club. The other characters on this slip-within-the-slip are partially obscured by the edge of the picture and by the brush, but are probably 子 “child” and 雀 “sparrow”. It can be difficult to ascertain the correct reading of nōsatsu pseudonyms; this one may be Kosuzume, Shijaku, or even Kojaku. In any case, it suggests that the paster and his companion are members of the “Sparrow Chick Club”. But since the entire print is also a votive slip, this name along with all the others present can be read as belonging to one of the real-life commissioners of the print—large, elaborate slips like this one typically had multiple sponsors. In this case, a real-life Sparrow Chick Club (yet to be identified) must have provided at least partial funding and guidance for this print.

3. Lèse Majesté: Transgressive Devotion

Nōsatsu began as a form, or accoutrement, of pilgrimage. Practitioners believed that the act of leaving slips behind on temple or shrine buildings functioned as a form of continuous prayer or worship. The inevitable conflation of worship with play that characterized Edo period religion meant that the pleasure–excursion aspect of slip pasting was never far from the surface, but as the twelve-chō slip we have been examining attests, even after nōsatsu turned into a collectors’ item, and nōsatsu culture came to encompass or perhaps even focus on the generation and consumption of unpastable multicolor prints, the idea of religious pilgrimage was never forgotten, and the presence of daimei in slips meant that a religious function was always implicit. However, this mixture of play and worship is not quite what I mean to explore with the concept of “transgressive devotion”. The irreverence expressed in the Great Buddha print may after all simply be that of enthusiastic pilgrims getting a little carried away. But nōsatsu often display more than just careless exuberance.

The three-chō slip in Figure 2 exemplifies this. It shows a nōsatsu enthusiast in an altercation with a priest. The scene is a Buddhist temple, as indicated by the large bell partly seen in the top left, meant to be struck with the log suspended over the men. The man at the center of the composition is clearly a paster caught in the act—he holds a pasting pole similar to those seen in Figure 1 and slips are scattered on the ground around him. At his feet is a man dressed as a temple acolyte. Evidently, the acolyte was tasked with chasing away the paster, but their encounter grew violent, and the paster won. The men’s pose, with the paster brandishing his pole like a weapon and trampling the priest underfoot, is (no doubt intentionally) reminiscent of statues of the Shitennō 四天王 or Four Heavenly Kings often found at temples. These Buddhist guardian figures are usually depicted in armor and brandishing swords or spears and are often shown treading on enemies of the faith depicted as demons. This slip, therefore, shows a role reversal, with the nōsatsu paster in the position of a defender of Buddhism and the acolyte placed in the position of the antagonist. The conceit is comical, but also significant. It captures an attitude of defiance often seen in nōsatsu, one in which the worshiper is determined to stick to his chosen expression of faith even in the face of institutional rejection. What the temple defines as transgression (trespass or vandalism), the practitioner defines as devotion, if only to a hobby.

Figure 2.

Untitled votive slip depicting paster in altercation with priest. Japanese votive slip (nōsatsu) collection (NE1184.35.N67_v34_090a), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries.

But as Figure 3 reminds us, this hobby was always implicitly a recognition of the power of religious observance—it was always implicitly a statement of faith. This two-chō slip is one of a series produced by the Manjiren 卍連 or Swastika Club (the swastika being, of course, a common Buddhist symbol), and depicts the legendary figure of Son Gokū 孫悟空 (Ch. Sun Wukong), the Monkey King who stars in the influential Ming-era vernacular novel Saiyūki 西遊記 (Ch. Xiyouji), or Journey to the West. Son Gokū is one of four figures assigned to guard Sanzō Hōshi 三蔵法師 (Ch. Sanzang Fashi; “Dharma Master Tripiṭaka”, a title granted to a Buddhist monk who deeply mastered the Buddhist teaching; the character in Saiyūki is loosely inspired by the historical Tang Dynasty monk Xuanzang 玄装 [602–664]); Sanzō Hōshi, in turn, is on a quest to cross Central Asia and bring back Buddhist sutras to China. Son Gokū’s magical powers (which include riding on clouds) and fighting prowess, abetted by his magical staff (which can be extended or contracted at will), save the company in many an adventure. But in addition to his role as a protector of Buddhism in the person of Sanzō Hōshi, the Monkey King is a trickster and a troublemaker, always willing to challenge any cosmic authority other than his own. In one of the most famous episodes in the story, the Buddha tells Son Gokū that no matter how far he goes, he can never escape the Buddha’s influence. Son Gokū promptly rushes to the edge of the universe, where he turns his staff into a brush and writes his name on one of the five pillars he finds there—only to find that the pillars are the Buddha’s fingers, and that he has never left the palm of the Buddha’s hand.8

Figure 3.

Untitled votive slip depicting Son Gokū. Japanese votive slip (nōsatsu) collection (NE1184.35.N67_v45_086a), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries.

Figure 3 presents an immediately recognizable Son Gokū: an anthropomorphized monkey in Chinese dress, standing on a cloud. In his left hand, he holds, instead of his familiar magical staff, a nōsatsu paster’s extendable pasting brush. The brush motif in turn may well call to mind Gokū’s act of writing on the pillars at the edge of the universe—recall that graffiti of this kind was remembered as a forerunner of votive slip pasting. The Monkey King, with all of his ambiguous relationship to Buddhism, is thus converted into an avatar of nōsatsu pasters, claiming for them a roguish energy that can both challenge the Buddha and serve him.

The remainder of this essay will explore three more Buddhist motifs in nōsatsu, reading them as examples of transgressive devotion in varying degrees. In each case, we will also note how, as in the Yoshitsuna print we began with, the print designers utilized the modular nature of exchange-oriented votive slips in distinctive ways, accomplishing a degree of both prayer and play seldom found in other woodblock prints.

It might be noted that some of the foregoing descriptions of votive slip activity are cast in the present tense, while other statements are in the past tense. In fact, nōsatsu culture persists today, both in its pasting and pilgrimage dimension (with recently pasted slips visible at many a shrine and temple) and its exchange and collecting dimension. This culture took shape over the late eighteenth century and reached its fullest development by the middle of the nineteenth; the three slips examined above all date to the Bakumatsu 幕末 era (1853–1868), after Western powers began to force their way into Japan but before the fall of the Tokugawa 徳川 shogunate. The advent of modernity in the ensuing Meiji 明治 period (1868–1912) affected the material and social context of nōsatsu as it did other forms of cultural production, but never killed the scene entirely. Nōsatsu continued as a subculture, persisting both in its social organizations (ren drawn largely from the older working-class neighborhoods of Tokyo) and its artistic content (preserving the esthetics and cultural values of late Edo). By the Taishō 大正 era (1912–1926), nōsatsu had come to attract the attention of a new type of cultural elite intent on rediscovering and perpetuating the plebeian culture of Edo; many of the slips to be discussed below come from this period and beyond (McDowell 2020; Smith 2012).

While it is possible to find traces of contemporary life in slips of any era, for the most part, their esthetics are those of the late Edo period: they tend to depict objects, social types, and customs that date back at least as far as the Bakumatsu period if not farther, and they depict them in ways more or less appropriate to that period. Of course, this late-Edo focus means something different in every era; a given motif could signify one thing in 1858, when Edo culture was contemporary, and something entirely different in 1928, when Edo culture was revivalist. That being said, the religious roots of nōsatsu remain today an integral part of the subculture’s self-conception, and imagery related to temples and shrines and the beliefs they represent plays a significant role in slips of every age. Therefore, this essay does not attempt to differentiate (much) between “premodern” and “modern” conceptions of Buddhism in nōsatsu, but rather seeks to explore the way devotion and transgression are coded into slips by the very self-consciousness that leads them to perpetuate Edo cultural norms.9

4. Serial Fidelity: Pilgrimage Circuits

The Yoshitsuna Great Buddha print is an example of collaborative print design and sponsorship: it would have been funded by and understood as representing all the aficionadoes whose daimei appear on it. This kind of arrangement is common in larger slips, no doubt due to the expense involved in having them made. They represent special projects undertaken by an entire club as an act of collective expression.

Collaborative slips did not always take the form of large, multi-chō prints, however. Often, a club’s collective expression would take the form of a series of smaller slips related in motif, each bearing as few as a single individual daimei. In these cases, the club as a whole must still have agreed on the conception, but the discrete-slip format allowed each individual member to claim credit for the existence of his or her own slip. Particularly when the motif is Buddhist in nature, this individual assertion of merit could be significant, as it harks back to the original proxy worship function of nōsatsu.

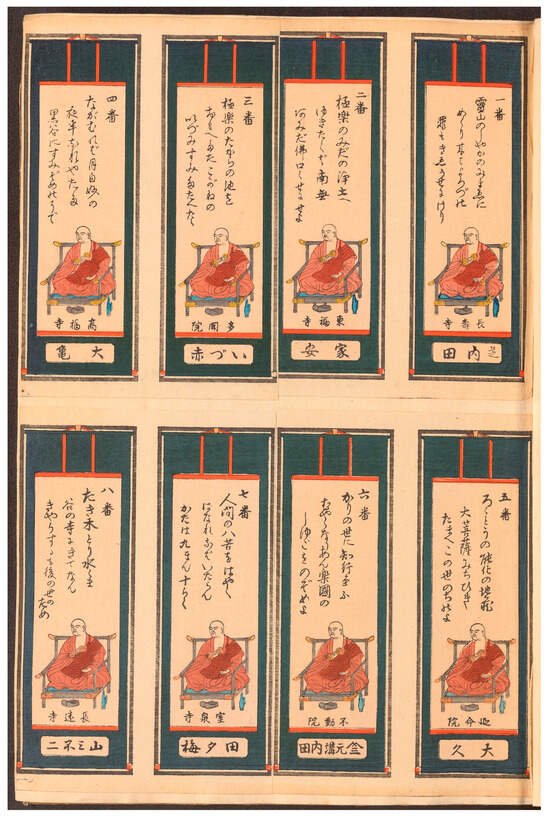

A conspicuous example of this can be seen in Figure 4, the first eight slips from a series of one-chō slips datable to 1916 representing all eighty-eight temples in the Gofunai 御府内 or “Metropolitan” pilgrimage circuit. This circuit was established in the eighteenth century as an Edo equivalent (gofunai referred to areas under the authority of Edo city magistrates) of the more famous Shikoku henro 四国遍路, an eighty-eight temple pilgrimage route around the island of Shikoku.

Figure 4.

Gofunai pilgrimage series, numbers 1 through 8. Japanese votive slip (nōsatsu) collection (NE1184.35.N67_v22_007), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries.

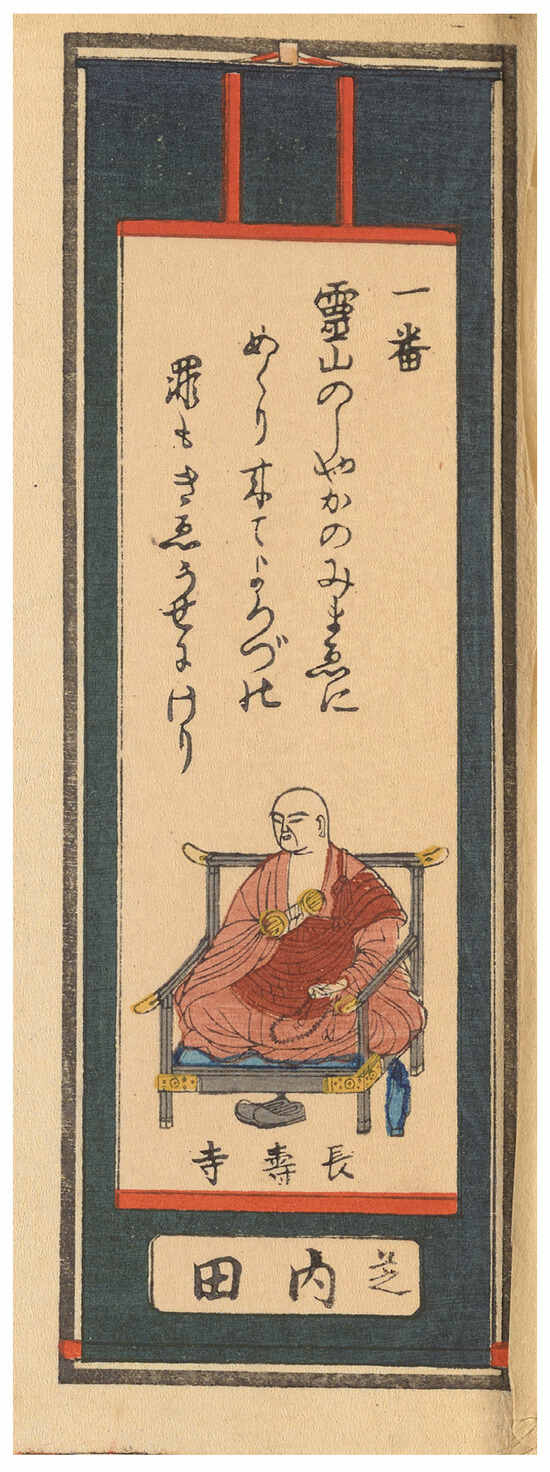

Each slip is nearly identical. The motif is of a hanging scroll, with the vertical format of the one-chō slip neatly matching the format of an unrolled scroll, complete with a trompe l’oeil hook at the top of each slip. The scroll features a conventionalized portrait of Kōbō Daishi 弘法大師, also known as Kūkai 空海 (774–835), the early-Heian 平安 cleric with whom both the Shikoku route and the Gofunai route are associated. Directly beneath the venerable priest is the name of the temple each slip is meant to represent. For example, slip no. 1 (Figure 5) is labeled “Chōjuji” 長寿寺, a temple in Takanawa 高輪 now known as Kōya-san Tokyo Betsuin 高野山東京別院. Above the portrait, each slip contains a number (referring to where the temple falls in the Gofunai circuit) and a calligraphed poem. These poems are the goeika 御詠歌, or devotional waka, associated with each temple. That for Chōjuji reads as follows: Ryōzen no / Shaka no mimae ni/megurikite/yorozu no tsumi mo/kieusenikeri 霊山のしやかのみまゑにめくり来てよろづの罪もきゑうせにけり, “Having come/before Sakyamuni/in his Holy Mountain10/all my sins/have utterly vanished”. Beneath the name of the temple, in a separate space, is a single daimei, different for every slip; this one may be read Shiba Uchida 芝内田.

Figure 5.

Gofunai pilgrimage series, number 1: Chōjuji. Japanese votive slip (nōsatsu) collection (NE1184.35.N67_v22_007a), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries.

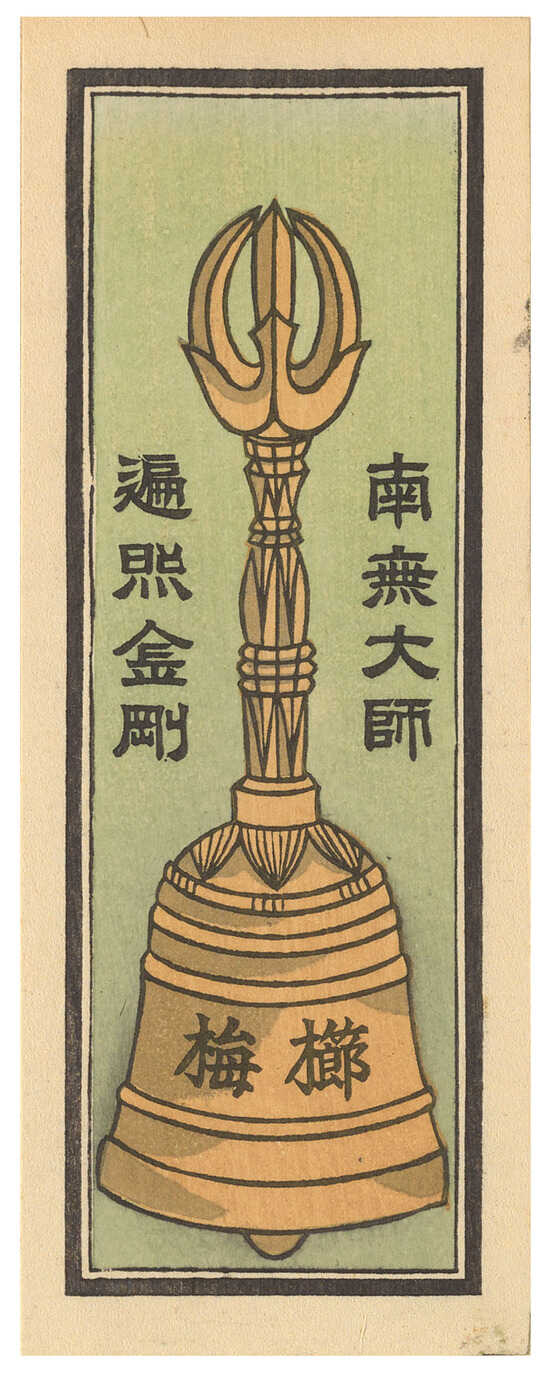

The visual simplicity of the series is key to this devotional effect. While each slip represents a different sponsor, the daimei is the only element of self-assertion allowed—no tell-tale logo intrudes to indicate what group the sponsor belonged to. Even the main pictorial motif, of Kōbō Daishi, is so conventional as to be commonplace.11 This subdued tone was originally set by Figure 6, a four-chō slip made to announce the meeting for which these slips were created. Exchange meetings were usually announced on specially designed slips of their own; this one specifies that an exchange meeting is to be held in the Takasago 高砂 Club in Asakusa 浅草 on 20 September, Taishō 5 (1916), chaired by two members identified by the daimei Horigen 彫源 and Horikin 彫金. The theme is not explicitly stated but is hinted at via the small ritual five-pronged bell (gokorei 五鈷鈴) depicted in red in the bottom left corner. The announcement slip does not name the club sponsoring the meeting, but this information is conveyed pictorially through the brush, pole, and pouch depicted on the announcement slip. These are, of course, tools associated with nōsatsu practice, and since the pouch is decorated with the logo of the Tomoe-ren 巴連, to which Horigen and Horikin belonged, we are meant to assume that the Tomoe-ren sponsored this meeting.

Figure 6.

Gofunai pilgrimage series, announcement slip. Japanese votive slip (nōsatsu) collection (NE1184.35.N67_v22_003a), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries.

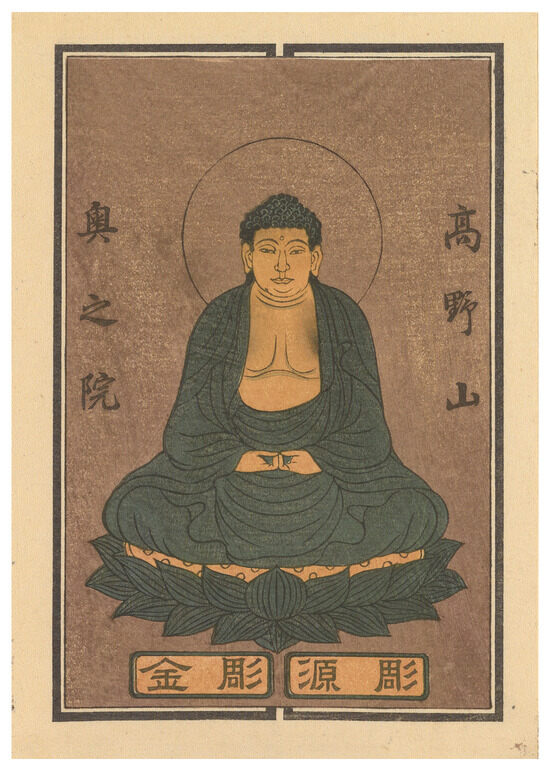

In addition to the pilgrimage set, a few other slips seem to have been created for the 20 September 1916 gathering, and they mostly display the same sense of sobriety. These include Figure 7, a handsome one-chō representation of a gokorei, with a daimei on the bell and a ritual invocation to Kōbō Daishi himself (namu Daishi kongō henjō 南無大師金剛遍照; “hail the Great Teacher, the diamond that shines everywhere”) on either side of the bell’s handle; and Figure 8, a two-chō depiction of an Amida 阿弥陀 icon with the legend “Kōya-san Oku-no-in” 高野山奥之院, Kōbō Daishi’s mausoleum in the temple complex on Mount Kōya.

Figure 7.

Gofunai pilgrimage series, unnumbered slip depicting gokorei bell. Japanese votive slip (nōsatsu) collection (NE1184.35.N67_v22_021b), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries.

Figure 8.

Gofunai pilgrimage series, unnumbered slip depicting Amida icon and label “Kōya-san Oku-no-in.” Japanese votive slip (nōsatsu) collection (NE1184.35.N67_v22_006c), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries.

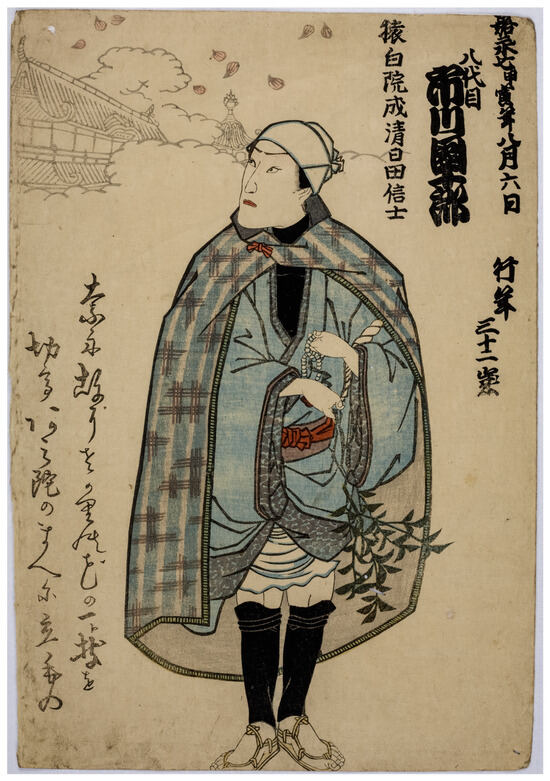

And yet this gathering of the Tomoe-ren does not seem to have been entirely devoid of a sense of play. Perhaps the most imposing print produced for it is Figure 9, an eight-chō slip designed by Hōsai 豊斎 (Utagawa Kunisada 歌川国貞 III [1848–1920]) and sponsored by Horigen and Horikin. It mimics the format of an ōkubi-e 大首絵 or bust portrait in ukiyo-e, and depicts a man dressed in priestly garb and holding a set of crystal prayer beads. The man’s rakish expression and devilish good looks suggest this is a kabuki actor in costume, which brings a whole different set of associations to the act of pilgrimage being celebrated at this event. The other slips speak of serene, worshipful focus, and make it easy to believe that they were commissioned by people who had actually performed the Gofunai pilgrimage, or at least desired to, and who meant these slips to express their faith in its efficacy. But the kabuki portrait suggests an alternate interpretation of events, one in which participants might have felt themselves to be, like the actor, worldly men disguised as pilgrims, their style and charisma shining through. For all the spiritual pretensions of the series, then, one might well imagine that if a corresponding pilgrimage had taken place, it might well have looked, in practice, something like that depicted in the Great Buddha print after all.

Figure 9.

Gofunai pilgrimage series, unnumbered slip credited to Hōsai depicting man in pilgrim garb. Japanese votive slip (nōsatsu) collection (NE1184.35.N67_v22_004a), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries.

The kabuki portrait itself might be susceptible to an alternate interpretation. Its subject’s priestly garb suggests the death portrait or shini-e 死絵 genre, in which recently deceased kabuki actors were memorialized in portrait prints that depicted them, not in any actual stage role, but in idealized scenarios often connected with prayer or pilgrimage. Figure 10, for example, an anonymous 1854 print, depicts Ichikawa Danjūrō 市川團十郎 VIII, who had just died; he is presented in the garb of a traveler, holding prayer beads and a sprig of shikimi 樒 (star anise), associated with offerings to the dead.12 The ghostly clouds and temple roofs behind him suggest we are seeing the actor on his posthumous journey to a paradisiacal rebirth. If the nōsatsu in Figure 9 is meant to suggest a shinie, then it could well be meant to suggest not only an actor but a deceased member of the Tomoe-ren itself. As we will see, it was not unusual for exchange meetings to be held as tributes or memorials (tsuizen 追善) to deceased members, with slips designed to have special relevance to the occasion. Although this one was not announced as such, its pilgrimage theme would certainly have been appropriate to a memorial event. In such a context, a large-format shini-e would have been a tribute made on nōsatsu’s own unique terms, combining religious offering with the motifs of Edo popular culture, in this case theater fandom. The result might have been a rather restrained sense of play, but play it was nonetheless.

Figure 10.

Memorial Portrait (Shini-e) of Actor Ichikawa Danjûrô 8th (1823–1854) as a Buddhist Pilgrim, artist unknown, 1854, print, 2021:43.124 (Gift of the Lee & Mary Jean Michels Collection), Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon.

The Gofunai pilgrimage slips are as reverent as the Great Buddha slip we began with is irreverent. The only variation among the eighty-eight slips comprising the pilgrimage sequence is in the text; pictorially, they are static, an impression heightened when they are all mounted in sequence on the pages of a scrapbook, as is the case in this copy. A sense of invention is not entirely absent—there is a subtle cleverness in the way each slip at first appears to be a portrait of Kōbō Daishi, only to be revealed as a portrait of a portrait, as it were. But overall, the visual elements seem designed to support the textual elements, the only elements that vary from slip to slip: the name of the worshiper, the name of the temple, and the poem. Because of these variations, the slips’ cumulative impact is much greater than that of any individual slip. Reading through them in order creates the illusion of a journey through the physical space of the pilgrimage route, but without the sensory distractions of variation in scenery; the viewer is instead encouraged to concentrate on the spiritual messages of each station in the pilgrimage in turn, messages that might differ from temple to temple but never conflict. The group members who commissioned these slips might have felt they had completed the pilgrimage itself in symbolic form, accruing the same merit; perhaps the collectors who assembled and experienced them felt the same.

This effect is created through canny use of the basic format of the nōsatsu, the small, one-chō slip. In the case of the twelve-slip Yoshitsuna print discussed earlier, large-scale collaborative sponsorship produced a large-scale image, a collective self-portrait of nōsatsu practitioners interacting with the Buddha. The Gofunai pilgrimage series is no less a collective self-portrait, but it achieves its effect through a series of one-chō slips; the format here is utilized for its modularity, with each slip functioning both singly and as part of a larger assemblage, in the same way that each sponsor accrues their own spiritual merit while contributing to the overall devotional (and artistic) project. The resulting slips can be contemplated as a whole—one could set them out next to each other and take them in at a glance. But they can also be contemplated one at a time, and in this case, they impose a kind of order on the viewer’s experience, as they ask to be examined in numbered sequence. These slips are discrete, but they are also, ineluctably, part of a whole. This play of form contains a number of possibilities for expressing religious sentiments and ideas.

5. Serial Fidelity, Continued: Hagiography

The numbering of the Gofunai pilgrimage slips creates a kind of narrative, in that it postulates a viewer experiencing them as a kind of imaginary pilgrimage. The slips shown in Figure 11 create another, more conventional, kind of narrative: a biography. To be precise, since these relate key events in the life of a revered religious figure, they represent hagiography in nōsatsu form.

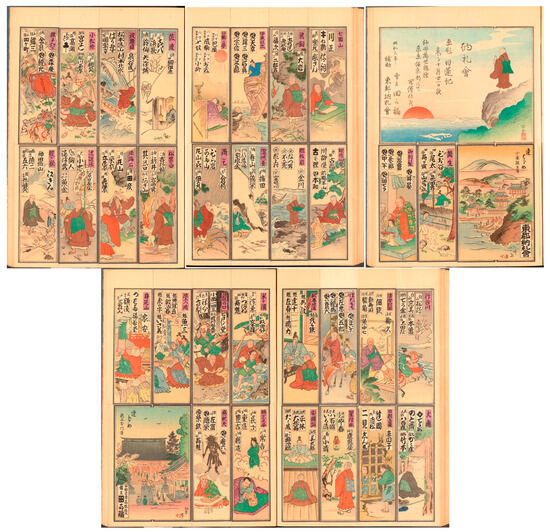

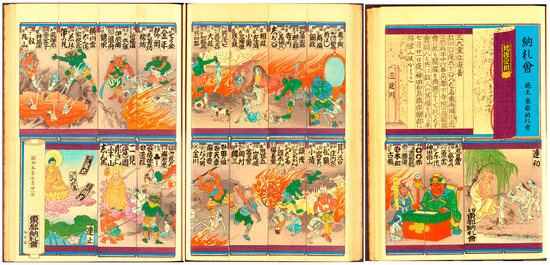

Figure 11.

“Record of Nichiren” series as pasted on five successive pages of an album. Shobundo senjafuda collection (Coll482_b010_v002_057 through 061), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries. The pages are arranged right to left in the order they occur in the album.

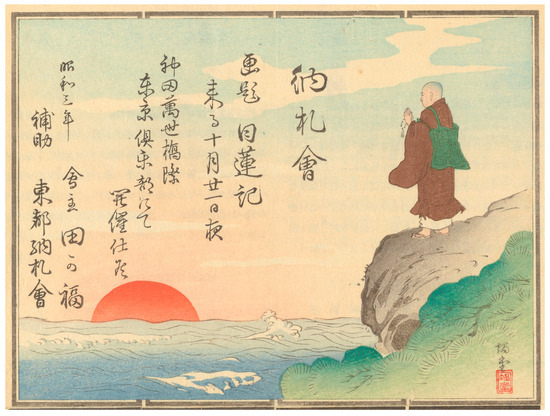

The theme of this series is laid out in the announcement slip shown as Figure 12. It tells us that a meeting is to be held on 21 October 1928, under the auspices of the Tōto Nōsatsukai 東都納札会 (Eastern Capital, i.e., Tokyo, Votive Slip Association), with the theme of Nichiren-ki 日蓮記, or “a record of Nichiren”. The monk Nichiren (1222–1282) was, of course, a pivotal figure in Japanese Buddhism, founding a sect that remains influential to this day and contributing to the preeminence of the Lotus Sutra over other Buddhist scriptures. Key points in his life and career had long been the stuff of legend and popular narrative, including on the kabuki stage, where Nichirenki was an element in the title of more than one play. The announcement does not seem to be evoking the stage, however, but the general phenomenon of popular Nichiren hagiography, and indeed the specific set of incidents depicted here does not appear to match any particular source. It is likely that this set represents an original sequence of motifs agreed on by the sponsors and selected from the many already established in print and illustration.13

Figure 12.

“Record of Nichiren” series announcement slip. Shobundo senjafuda collection (Coll482_b010_v002_057a), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries.

The announcement features a depiction of Nichiren atop a seaside cliff facing the rising sun, a reference to perhaps the pivotal moment in his life when he first recited the Lotus Sutra mantra namu myōhō renge kyō 南無妙法蓮華経 (“hail the wondrous law of the Lotus Sutra”) in a grove at the temple of Seichōji 清澄寺 (also known as Kiyosumidera; present-day Chiba prefecture), the symbolic founding of his movement. The illustration is by an artist known only as Kadō 蝸堂 (no dates; he is known to have produced prints related to the Sino-Japanese [1894–1895] and Russo-Japanese [1904–1905] wars), whose signature appears on some of the other slips in this series, making it likely he did all of them.

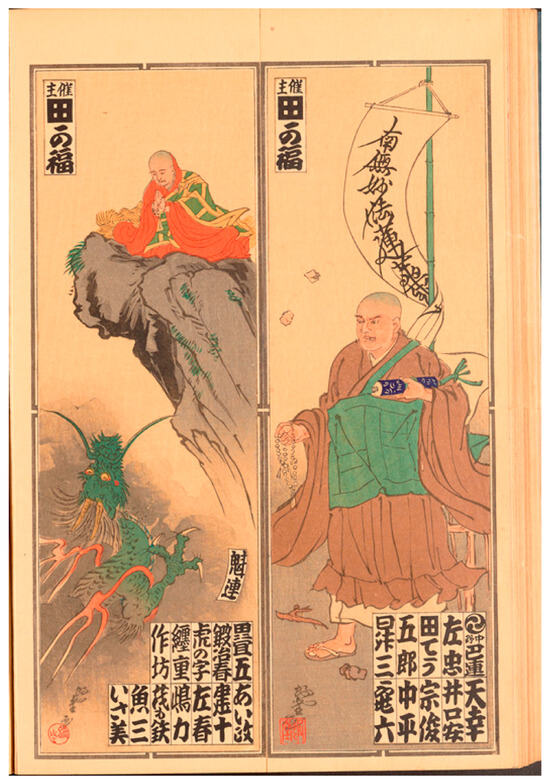

The series proper begins with a two-chō slip labeled ren-hajime 連はじめ or “first of sequence;” it shows the temple Tanjōji 誕生寺 in Kominato 小湊, present-day Chiba 千葉 Prefecture, founded to mark the site of Nichiren’s birth. The daimei on this slip credits it jointly to the Tōto Nōsatsukai. The final slip in the series is another two-chō slip, this one labeled ren-dome 連どめ or “last of sequence;” it shows the temple Ikegami Honmonji 池上本門寺 in Tokyo, founded on the site of Nichiren’s death. The daimei here identifies the slip’s sponsor as Takafuku 田か福, who had been named as host of the meeting on the announcement slip. Following the series proper—that is, pasted into the scrapbook that contains the series and found on the page following that on which the ren-dome occurs—are two additional slips, Figure 13. They each depict Nichiren, but in a larger format that sets them apart from the hagiographical series; neither scene is titled, which further sets them apart. Both are vertical four-chō compositions with daimei representing Takafuku, as host, and a further group of sponsors. The slip on the right depicts a young Nichiren preaching in the street, in front of a banner bearing his familiar Lotus Sutra mantra. The one on the left presents an older Nichiren (in the garb of a senior cleric) seated on a cliff in prayer, while a dragon approaches him from below.

Figure 13.

“Record of Nichiren” series unnumbered slips depicting (right) Nichiren preaching in the street and (left) Nichiren seated on a cliff in prayer. Shobundo senjafuda collection (Coll482_b010_v002_062), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries.

The main hagiographical sequence consists of thirty-two one-chō slips pasted in neat order between the Tanjōji and Ikegami Honmonji slips, that is between the ren-hajime and ren-dome slips. Each of these slips depicts a significant moment in Nichiren’s life and contains a colophon in purple titling the scene as well as five daimei in white. This main sequence elides the scene found on the announcement slip, that of Nichiren’s first recitation of his Lotus Sutra mantra. Given the centrality of this first recitation to Nichiren’s legend, its absence from the sequence cannot be accidental; rather, the thirty-two slips should probably be understood as presenting events that led up to and then proceeded from that pivotal moment. However, the two four-chō slips that lack titles (those in Figure 13) seem to duplicate scenes that are represented in the series. The one on the right corresponds to the scene in the main sequence labeled tsuji seppō 辻説法 (“Crossroads Sermon”), a famed incident when Nichiren, having founded his sect in Awa province, goes to the shogunal capital of Kamakura and preaches to the public at a crossroads—his fiery denunciations of other sects provoked his hearers to throw things at him. The one on the left, though differing in its iconography, probably depicts the scene labeled Shichimensan 七面山 (“Shichimen Mountain”), a site in modern Yamanashi prefecture where Nichiren was preaching when a woman in his audience revealed herself as the dragon goddess of the mountain and vowed to protect those who chant the Lotus Sutra mantra.

It is not difficult to construct a narrative, indeed a metanarrative, from all this. The metanarrative begins with the announcement slip, which presents the central event in Nichiren’s life (for a follower of Nichiren, one of the central events in history). This is followed by the ren-hajime, which presents not a scene from Nichiren’s life but a temple later erected commemorating the beginning of that life. While the temple is presented as it would have looked in the Edo period (the predominant pictorial paradigm in nōsatsu even today), rather than in 1928, it still situates the viewer in a contemporary moment compared with Nichiren’s life. From there, we proceed through the narrative within the metanarrative, the life and career of Nichiren, after which we are returned to the contemporary moment with the ren-dome, which places us at another temple, the one built to commemorate the site of Nichiren’s death. This is followed by the two four-chō slips that recap, as it were, particularly dramatic moments from the story we have just experienced. The metanarrative has a hint of pilgrimage about it, as we are taken to the Tanjōji in Kominato and thence to the Ikegami Honmonji in Tokyo; in this reading, the recital of Nichiren’s hagiography can be thought of as the pilgrim’s reflections while traveling between these two spots. The announcement slip, in this reading, becomes the motivation for the pilgrimage, while the two concluding four-chō slips represent memories or impressions the pilgrim retains after the pilgrimage has been concluded.

This metanarrative represents what we might call an ideal reading of these slips, or the reading they demand of us; but the actual arrangement of them in the collector’s scrapbook offers a potential subversion of this reading. While the announcement, ren-hajime, and ren-dome slips are all placed where we would expect them to be, the thirty-two slips of the main sequence are not in chronological order. These thirty-two are titled (that is, the scene they depict is identified) but not numbered, meaning a collector seeking to put them into chronological order would have needed some familiarity with accounts of Nichiren’s life. As it happens, whoever assembled the scrapbooks containing this series pasted the slips out of order. It may simply be that the collector was not familiar with Nichiren’s life and legend—but even a complete stranger to Nichiren would likely have realized that his death scene should come last, whereas it appears fourth from last in this scrapbook. More likely, what this arrangement implies is a particular kind of indifference. The scene of Nichiren’s birth comes first (although it should be preceded by what is here the sixth slip, which is Nichiren’s mother dreaming of clasping the rising sun to her breast while pregnant with him), and the death scene comes on the last page, and that was probably close enough for this collector. They arranged the other slips randomly, or according to a private logic unrecoverable to us—perhaps according to who the sponsors were, or according to what seemed to look best where.

What this indifference tells us is that here, too, we have an artistic project that grounds itself in religious doctrine and practice but seems to accommodate modes of engagement other than purely devotional. The designers and commissioners of these slips took care to ensure that they could function as hagiography, communicating both the facts of Nichiren’s life and the experience of a faithful follower of his, but the collector, at least, seems to have prized the slips primarily as artifacts of nōsatsu culture. The slips that have special functions in the context of votive slip exchange are carefully placed in their rightful spots, and the fact that this makes devotional sense as well seems almost incidental, in light of the fact that the thirty-two main slips are placed with little regard for sequence. This privileging of the secular mode of engagement over the sectarian may not be as transgressive as the Yoshitsuna print with which we began, but it does subtly undercut the devotional tendency of the project.14

6. Crime and Punishment: Hell Scenes

In both the Gofunai pilgrimage series and the Nichiren hagiography series, we see an artistic conception that announces itself as devotional, but that either in execution (with the shini-e) or in consumption (with the misarrangement of the stations in Nichiren’s life) proves itself to be susceptible to play. As noted earlier, play was seldom very far from religious observance in the Edo period; any tension between devotional and ludic tendencies in these two series is probably more apparent to the outside analyst than the participant. My point in this article is to explore a tension much more fundamental, much more openly iconoclastic, than this. Nevertheless, the Gofunai and Nichiren series are both useful as a baseline index of what we might call alloyed religiosity in senjafuda. The oppositionality encapsulated in the Son Gokū slip and broadly gestured to in the Great Buddha slip is glaring and seems at first to contrast with the reverence of the Gofunai and Nichiren sets. But what the foregoing examination of the Gofunai and Nichiren series shows is how, even at their most orthodox, Buddhist-themed nōsatsu cannot escape a certain level of irreverence. The converse is true as well: What the Son Gokū and Great Buddha prints show is how play-imbued irreverence is always liable to slip into outright comic defiance. This defiance was part and parcel of the religious expression so common in senjafuda.

Nowhere is this dynamic so well displayed as in depictions of hell and related imagery. The four-chō slip shown as Figure 14 is a classic example. The artist is Yoshitsuna again, which dates the print to the mid-to-late 19th century. The scene would have been familiar to anyone versed in popular Buddhist hell imagery, as it depicts Enma 閻魔, King of Hell, judging sinners newly arrived in his domain. The grimacing sovereign is seated at his desk, reviewing a scroll inscribed with the names of sinners, while his majordomo hovers next to Enma’s desk at the right edge of the composition, holding his boss’s massive flat scepter of office. A couple of Enma’s legendary assistants loom to the left of the desk, here combined on one pedestal: Mirume 見目 and Kaguhana 嗅鼻, Seeing Eye and Sniffing Nose. Behind Enma in the top left corner, we see the approach to his court of judgment, with dead souls standing on the bank of the Sanzu 三途 River, confronted by Datsueba 奪衣婆, the Clothes-Stripping Crone, who confiscates robes and hangs them on trees. Everywhere, condemned sinners are shown suffering in a lake of blood or among the flames of hell, punishments overseen by two imposing demons, wardens of hell.

Figure 14.

Nōsatsu of King of Hell Judging Nōsatsu Group, Utagawa Yoshitsuna, mid/late 19th century, nōsatsu print, 1964:3.23.1687 (Gift of Frederick Starr Estate), Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon.

Between the two demons stands a large mirror, rendered in metallic pigment. This is the famed jōhari no kagami 浄玻璃の鏡 (“uncloudy mirror”), a mirror that shows dead souls the sins they committed in life. And what crime is being reflected? Nōsatsu pasting. In the mirror image, one man holds a long-handled brush of the type seen in the Great Buddha slip, while another man, perched on the shoulders of a third, writes his name directly on a temple wall—a precursor of nōsatsu pasting that, as we have already seen, was kept alive in depictions of nōsatsu practice. The implication is clear: the groveling souls in front of the mirror are men who were, in life, nōsatsu practitioners. Now, in death, they are to be punished for defacing temple property.

Of course, this entire scene is itself a votive slip, and a perfectly functional one: all the names on Enma’s scroll are in fact daimei, as is the writing on the scepter and some of the writing on the milepost next to Datsueba. The surface message is clear: nōsatsu will lead you to hell. This is a perfectly justifiable explanation, since temples officially prohibited the pasting (and scrawling) of daimei. But the tone of the slip is one of insouciance, even outright defiance: we (as pasters, collectors, commissioners, viewers) do not care. A more transgressive stance can hardly be imagined.15

But as Figure 15 shows, this same pictorial motif—senjafuda practitioners in hell—could be utilized to express profound devotion, as well. This is a single twenty-four-chō horizontal composition; the individual slips comprise one four-chō announcement slip, one two-chō ren-hajime slip, one two-chō ren-dome slip, and sixteen one-chō slips. In the Nichiren series, the announcement slip forms part of the narrative, albeit a displaced part; here, something similar happens, as the announcement slip is meant to be seen as part of the single unified composition completed by the rest of the series. This composition, in turn, partakes of the metapictorial quality of the Gofunai slips, as these slips are meant to represent an illustrated scroll.

Figure 15.

“Hell Tableau” series as pasted on three successive pages of an album. Shobundo senjafuda collection (Coll482_b010_v004_001 through 003), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries. The pages are arranged right to left in the order they occur in the album.

As presented here, the slips have been mounted in a scrapbook, somewhat fragmenting the composition (another copy of the series has been further fragmented, mounting some of the slips out of order or separated by unrelated slips, and leaving other slips unmounted); to fully appreciate the composition, one needs to rearrange them into a single horizontal sequence. The announcement slip is meant to be placed at the far right. It begins with writing on a blue background. The writing reads, “Votive Slip Meeting: Patron, Tōto Nōsatsukai”. The blue background continues at the upper and lower edges of each following strip and is meant to represent a neutral space or surface against which the scroll is viewed. To the left of the “Votive Slip Meeting” inscription, we see the brocade cover of an unrolled scroll, with the scroll’s paper continuing to the left; a red silk cord (meant to secure a scroll when it is rolled up) can be seen spilling out from behind the cover. The cover bears a title strip: “Jigoku hensō” 地獄変相, or “Hell Tableau”, a common genre of religious painting. The “scroll” begins with a short textual inscription, followed by a small pictorial device: a wooden mile-marker reading “River Sanzu”. In terms of the announcement slip, this mile-marker hints at the territory to be covered in the series proper; in terms of the overall composition, it signals the viewer’s arrival in hell.

Most of what follows is a more detailed version of the hellscape depicted in the Yoshitsuna four-chō slip just discussed. The ren-hajime slip shows Datsueba relieving newly arrived dead souls of their robes. This is followed by a scene of Enma at his desk, complete with scepter-holding majordomo, Seeing Eye/Sniffing Nose, and the mirror. Hell’s torments are depicted in much more detail here and include no fewer than thirteen hell wardens overseeing a boiling cauldron, a flaming cart, a lake of blood, and a myriad of souls in agony. But the final one-chō slip provides hope, showing Bodhisattva Kṣitigarbha, or Jizō 地蔵, accompanied by heavenly beings, appearing to deliver three sinners from their torment. The sequence concludes with the ren-dome, which shows Amida Buddha in his Pure Land, where the three saved souls are bound. The ren-dome also shows the scroll’s spindle, thus bringing us out of the metapictorial space. On the spindle is text dating the series (21 July, Shōwa 昭和 5/1930) and identifying the artist (Kadō again), along with a daimei for the Tōto Nōsatsukai itself.

The mirror in this set is blank, but any viewer familiar with Yoshitsuna’s hell scene might guess that at least some of the sinners depicted here are being punished for pasting senjafuda. This assumption is bolstered by the text found on the announcement slip, which reads:

In Memoriam of Three Great Souls:In memory of the late Ota of Yotsuya, Tsubame of Shitaya, and Kawashō of Higashi Ryōgoku, we will bring slips on the theme of Enma, on the occasion of the Bon Festival as annually observed in the Capital’s temples, as an offering to our three departed friends, at the Izumibashi Club on July 21.

This explains why Jizō is saving exactly three souls at the end of the “hell scroll”, and why the scene of Amida features three daimei: they belong, of course, to Ota 尾太 of Yotsuya 四谷, Tsubame つばめ of Shitaya 下谷, and Kawashō 川正 of Higashi Ryōgoku 東両国. The daimei are another metapictorial touch—they are fluttering in the air, as if they are printed daimei slips that have been tossed into the Pure Land ether; they invite the viewer to imagine them as embodying the now-saved Ota, Tsubame, and Kawashō. In this nōsatsu vision of paradise, the practitioners themselves have entered into nirvana, leaving behind only traces of themselves in the form of their slips—a cosmic version of the proxy logic of worldly votive slips. But perhaps these slips too have somehow been redeemed, delivered into the Pure Land, where they continue to assert their makers’ individuality (after all, the daimei remain) even in a space meant to represent egolessness. If nōsatsu have sent these three men to hell, it would seem they have also led them to paradise.

The hell scroll set is a deeply moving example of nōsatsu. It functions as a pictorial offering to deceased colleagues (something that may be true of the Gofunai series as well), but it is more than a simple tribute. It seeks to enact their ultimate deliverance into paradise. The unbroken parade of sponsor daimei in the upper part of each slip make it seem as if the living are escorting the dead through hell, keeping them company in their sufferings and ensuring (as Buddhist offerings are meant to) that those sufferings end in salvation. The cheeky, almost literally devil-may-care attitude of the Yoshitsuna hell scene is perceptible here, too, in the assumption that Ota, Tsubame, and Kawashō are bound for hell: of course they are, as nōsatsu pasters. But the scroll series constitutes a powerful counterclaim of precisely the kind we saw in the Son Gokū slip: nōsatsu practice, for all its defiance of religious authority, can in fact be a powerful affirmation of religious meaning. For all its transgressiveness, it can in fact be a form of devotion. Votive slips can damn you; but they can also save you.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The most accessible English-language account of nōsatsu in print is in Rebecca Salter’s Japanese Popular Prints from Votive Slips to Playing Cards (Salter 2006; nōsatsu are explored on pp. 94–107). More recently, Kumiko McDowell examined the social history of nōsatsu, particularly in the early 20th century, in an M.A. thesis (McDowell 2020). Particularly useful generalist accounts in Japanese are Sekioka Senrei 関岡扇令’s catalog Edo korekushon: Senjafuda 江戸コレクション〜千社札 (Sekioka 1983) and Miyamoto Tsuneichi 宮本常一’s catalog Senjafuda 千社札 (Miyamoto 1975), while the most complete scholarly exploration is Takiguchi Masaya 滝口正哉’s monograph Senjafuda ni miru Edo shakai 千社札に見る江戸社会 (Takiguchi 2008). This essay is indebted to all of the above sources. Finally, my website Yōkai Senjafuda (Walley 2019) contains a broad overview of nōsatsu culture aimed at the general reader; some of the material in the present essay is derived from commentary developed for the website. |

| 2 | Salter (2006) gives a more in-depth account of the pasting and pilgrimage activities covered in this section; see pp. 94–99 especially. |

| 3 | Often pronounced senshafuda by cognoscenti (see Takiguchi 2008, p. 4). The term senjafuda is more familiar to general audiences today, but nōsatsu seems to be a more common term in the materials under consideration here. |

| 4 | All slips discussed in this essay are part of the University of Oregon’s collection. |

| 5 | Several Buddhist sites in Japan offer womb tours in which the pilgrim crawls through a usually dark space within, beneath, or behind an icon. In the case of the Great Buddha at Kamakura, pilgrims can enter the belly of the Buddha itself. |

| 6 | See (Salter 2006). On the interrelationship of play and worship in the period, see Nam-Lin Hur, Prayer and Play in Late Tokugawa Japan: Asakusa Sensōji and Edo Society (Hur 2000). |

| 7 | Interestingly, Buddha is popularly thought to have thirty-two distinguishing marks or physical characteristics (J. sanjūnisō 三十二相); whether the number of slips in this print is meant to suggest these marks is speculative, but it would be typical of the sly referentiality at work in Edo popular visual culture. |

| 8 | For a full translation of a canonical account of this incident, (see Jenner 1993, pp. 149–51). |

| 9 | Elsewhere (“The Tengu of Mount Kurama(e): Transgression, Devotion, and Self-Representation in Votive Slip Collecting”, forthcoming), I take the opposite tack and examine how a particular motif (in this case, the tengu 天狗) has different significance in early and later nōsatsu. (Walley forthcoming) |

| 10 | A common abbreviation for Ryōjusen 霊鷲山, “Holy Vulture Peak”, a site where Buddha preached. |

| 11 | The simplicity and uniformity of the Gofunai series contrasts significantly with a pilgrimage series reproduced in (Sekioka 1983, pp. 123–25, commentary on p. 156). This series, from 1925, depicts the Saigoku Sanjūsansho 西国三十三所 route, a pilgrimage circuit that links thirty-three Kannon 観音 temples in Western Japan. Each slip in the series is two chō arranged vertically, and each slip depicts that main icon of a temple on the circuit along with its goeika. The visual conceit of votive slips as a hanging scroll is the same as in the Gofunai series, but each slip in the Saigoku series is visually unique, with its own color and design scheme to go along with its unique main icon. |

| 12 | For a discussion of shini-e, (see Guth 2005–2006). |

| 13 | Illustrated accounts of Nichiren’s life go back to the Muromachi 室町 period, and monk Nitchō 日澄’s (1261–1310) Nichiren Shōnin chūgasan 日蓮聖人註画讃 (Saint Nichiren in pictures, captions, and commentary); painted versions include a 1536 scroll painted by Kubota Muneyasu 窪田統泰 (n.d.) and a sixteenth-seventeenth century codex painted by Sakyō Chō 左京兆 (n.d.) (Tokyo National Museum 2003, pp. 42–45 and 220–21). At least one illustrated woodblock-printed version circulated in the Edo period, published as early as 1632 by Nakano Ichiemon 中野市右衛門 [d. 1639]) (Nakano 1632). The illustrations in the nōsatsu series do not closely match any of these precedents. The nōsatsu series might be further compared with Nichiren Shōnin goden mokuhanga 日蓮聖人御伝木版画 (The life of Saint Nichiren in woodblock prints), a series of thirty-three woodblock prints on the life of Nichiren digitized by the Risshō University Library; the prints were designed by a variety of artists and published circa 1928–1935. Risshō also digitized Kōso on’ichidai ryakuzu 高祖御一代略図 (Abbreviated illustrations of the life of an eminent monk, a series of ten prints designed by Utagawa Kuniyoshi 歌川国芳 (1798–1861). These two print series (see Nichiren Shōnin Kichō Shiryō Gazō Ichiran 日蓮聖人貴重資料画像一覧) do not completely overlap in terms of the episodes they depict, and the nōsatsu series does not completely match either of them, suggesting that all were drawing from a pool of famous incidents in Nichiren’s life that nevertheless had not coalesced into a single standard iconography (Risshō Daigaku Toshokan n.d.). |

| 14 | This finding echoes Takiguchi’s analysis (Takiguchi 2008, pp. 130–31) of a series of slips made in the 1840s or 1850s on the theme of the Kanda 神田 Shrine Festival’s parade floats. The exact floats depicted do not seem to match the records of any year’s parade, although they do correspond to the neighborhoods the slips connect with the floats, suggesting they commemorate the festival in general rather than any particular year’s observance. Furthermore, Takiguchi notes that in large part, the sponsors of each slip do not seem to have resided in the neighborhoods responsible for the floats depicted. In other words, the slips were not sponsored by the parishioners’ associations who supported the parade, and therefore, the series should be taken not as a record of participation in a religious observance but as a recognition of and tribute to the festival as a part of the city’s culture. |

| 15 | This slip’s depiction of hell is very much in the spirit of late-Edo parodic hell scenes as discussed in (Hirasawa 2008, pp. 35–39), representing what she calls a secularizing tendency. As she suggests, however, the iconoclasm inherent in this approach was not entirely incompatible with the primary message of hell imagery: “Overcoming fear of mortality and shattering conceptions of the world were also, however” she writes (pp. 38–39), “objectives faithful to the spirit and intent of many orthodox teachings about hell”. |

References

- Guth, Christine E. 2005–2006. Memorial Portraits of Kabuki Actors: Fanfare in the Floating World. Impressions 27: 22–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa, Caroline. 2008. The Inflatable, Collapsible Kingdom of Retribution: A Primer on Japanese Hell Imagery and Imagination. Monumenta Nipponica 63: 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, Nam-lin. 2000. Prayer and Play in Late Tokugawa Japan: Asakusa Sensoji and Edo Society. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Jenner, William Francis, trans. 1993. Journey to the West. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, Kumiko. 2020. Printed, Pasted, Traded: Nōsatsu as an Invented Tradition. Master’s thesis, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, Tsuneichi 宮本常一, ed. 1975. Senjafuda 千社札. Tokyo: Tankōsha 淡交社. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano, Ichiemon 中野市右衛門. 1632. Nichiren Shōnin Chūgasan 日蓮聖人註画讃. Place of publication unknown.

- Risshō Daigaku Toshokan 立正大学図書館. n.d. Nichiren Shōnin Kichō Shiryō Gazō Ichiran 日蓮聖人貴重資料画像一覧. Available online: www.ris.ac.jp/library/nichiren-kichou/index.html (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Salter, Rebecca. 2006. Japanese Popular Prints from Votive Slips to Playing Cards. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sekioka, Senrei 関岡扇令, ed. 1983. Edo korekushon: Senjafuda 江戸コレクション〜千社札. Tokyo: Kōdansha 講談社. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Henry D., II. 2012. Folk Toys and Votive Placards: Frederick Starr and the Ethnography of Collector Networks in Taisho Japan. In Popular Imagery as Cultural Heritage: Aesthetical and Art Historical Studies of Visual Culture in Modern Japan. Final Report, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research #20320020 (PI: KANEDA Chiaki). [Google Scholar]

- Takiguchi, Masaya 滝口正哉. 2008. Senjafuda ni miru Edo shakai 千社札に見る江戸社会. Tokyo: Dōseisha 同成社. [Google Scholar]

- Tokyo National Museum. 2003. Dai Nichiren ten: Rikkyō kaishū 750-nen Kinen 大日蓮展〜立教開宗750年記念. Tokyo: Tokyo National Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Walley, Glynne. 2019. Yōkai Senjafuda. University of Oregon Libraries and Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art. Available online: https://glam.uoregon.edu/yokaisenjafuda (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Walley, Glynne. Forthcoming. The Tengu of Mount Kurama(e): Transgression, Devotion, and Self-Representation in Votive Slip Collecting.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).