1. Introduction

This article constitutes a preliminary essay within a broader doctoral research project that examines the scope of visual culture as a source of artistic and historical knowledge in audiovisual production. The larger investigation explores how figures drawn from the history of horror and the occult—including the witch and other emblematic archetypes—have been represented and reinterpreted through art, fashion, and cinema. Within this framework, the present study focuses specifically on the origins and early iconographic constructions of the witch, a figure whose evolution reveals the complex intersections between aesthetics, mythology, and gender ideology.

The reflections presented here are conceived as the first part of a twofold inquiry. This initial article addresses the emergence of the witch as a social and symbolic construct and her earliest depictions in art and literature, tracing how her image crystallised around themes of evil, sexuality, and transgression. A second complementary article will examine the witch’s subsequent transformation from persecuted outcast to cultural icon, analysing how this figure has been reappropriated within contemporary visual and popular culture as a means of feminist self-assertion and empowerment.

To this end, both tangible and symbolic connections have been traced, articulated through the use of costume, scenography, photography, and colour as essential elements of storytelling and the creation of visual identity in audiovisual media. All this is undertaken by drawing on research across diverse fields such as art history, fashion culture, architecture, and the cinematic universe, establishing interrelations and reflections on their aesthetics and collective imaginaries. Without yet seeking to establish a definitive methodology, the aim here is to reflect on the role of these domains across a specific period in the history of cinema, namely fantastic and horror films from 1968—the year in which the Sitges Film Festival was founded—to the present.

Previous studies have revealed a correlation between witchcraft and feminism (

Deepwell 1998). This work, however, adopts a specific perspective of an aesthetic nature. Furthermore, to date there are several investigations into the influence of medieval aesthetics on contemporary fashion (

Luceño Casals 2015;

Gómez-Chacón 2022), as well as numerous studies analysing the close relationship between fashion and cinema (

Nadoolman Landis 2012). The vast majority of these, however, take as their object of study Hollywood cult films, often adopting an idealised vision of the subject.

Scholarship devoted to the imaginary of fantastic and horror cinema remains scarce, despite its relevance within popular culture and its consequent potential as a cultural product. For this reason, its study is proposed here as an integral artistic phenomenon. What appears to differentiate this cinematic genre from others is an apparent lack of aesthetic commitment, replaced by a kind of over-involvement in sensations and emotions. Sound, lighting, and characterisation often serve to construct the monster, although there are certain exceptions in which costume design and artistic direction are as important as, or even more important than, the narrative itself. This refers to the ecstasy that envelops the figure of the monster and the sinister beauty of the grotesque. It should be borne in mind that this work is based on a compilation of films from the genre, preselected on the basis of their visual richness and the artistic references informing the creative process of their costume designers.

The witch is a figure constructed through social representations—that is, socially shared images of reality. While it acquires specific meanings according to the historical moment and the territory in which it is produced, it also shares common characteristics: her intimate and sexual bond with the Devil, her fascination with evil, practices such as flying on broomsticks, the preparation of potions and spells to heal or to harm, knowledge of botany, alchemy, and human anatomy, and participation in gatherings with other women in which the Devil was invoked as a special guest, with whom they allegedly engaged in sexual relations and erotic dances in exchange for powers, among many other traits associated with witches. In this way, a cultural idea was formed of the subject embodied by women labelled and stigmatised as witches.

Associated with the practice of black magic and linked to the moon and the night, they were regarded as something to be prohibited and punished.

Wise women, grandmothers, healers, herbalists, shamans, sorceresses, midwives, abortionists, heretics, spinsters, widows, lesbians—these women shared a common feature: they transgressed boundaries, crossing the limits of what was permitted and prescribed within hegemonic institutions of power such as the Church, the family, the State, and science. These women ultimately came to be produced as witches, a figure encompassing those who, in their particular time and place, did not conform to the demands and requirements of the singular model of womanhood.

Gender archetypes appear to date back to the origins of Western culture (

Harris and Young 1979), determining the representation of men and women and, by extension, their roles within society. In this way, a series of stereotypes that shape how individuals perceive and experience the world persists in the collective subconscious. This article proposes a reflexive awareness of the persistence of these myths, encouraging us to traverse the “difficult road out of their domains”.

“As with mythological figures, archetypal models combine historical facts with fantasies, realities with desires, tragedies with fears and terrors, all bound together with religious beliefs, ethical values, and moral prescriptions or proscriptions concerning what must be thought, felt, and done. They thus constitute the foundations upon which our values are built” (

Guil Bozal 1998, p. 95).

2. Women: The Origin of Evil or a Scapegoat?

As early as the sixteenth century, Michel de Montaigne had already perceived the following: “It is probable that the belief in miracles, visions, enchantments, and such extraordinary occurrences springs in the main from the power of the imagination acting principally on the minds of the common people, who are the more easily impressed. Their beliefs have been so strongly captured that they think they see what they do not” (

de Montaigne 1993, p. 39). This insight anticipates the mechanisms through which theological tension and collective imagination combined to generate the image of the witch—a figure at once imagined and terrifyingly real in the minds of her persecutors.

In contrast to Montaigne’s view, which attributes the persistence of witchcraft beliefs to the credulity of the uneducated masses, Richard

Kieckhefer (

2021) identifies the intellectualisation of such ideas as the true catalyst for the witchcraft theory that emerged in late medieval Europe. According to Kieckhefer, the development of witchcraft discourse resulted from the convergence between learned demonology and popular superstition. While certain humanist thinkers maintained a degree of scepticism toward diabolism, it was those among the educated elite who firmly believed in it that gave witchcraft its distinctive intellectual structure. Their intervention proved decisive, as they imposed theological and juridical frameworks upon simpler, pre-existing folk beliefs, transforming scattered accusations into a coherent system of persecution (p. 75).

Be that as it may, the idea of women as the origin of evil constitutes one of the most repressive mechanisms directed towards the female gender and, regrettably, we may still discern parallels today. In the words of the director

Pablo Agüero (

2020): “Because a woman dresses in a certain way or is smiling, it is said that she is provoking, as though her joy, her carefreeness, or her beauty were a crime”.

And so it seemed to be that “The word ‘witch’ brings before us the frightful old women of

Macbeth. But their cruel processes teach us the reverse of that. Numbers perished precisely for being young and beautiful” (

Michelet 1883).

This section analyses the demonisation of women as a strategy of delegitimisation driven by the patriarchal system. At the end of the Middle Ages, such a system required a scapegoat onto which it could divert attention and channel the anxieties generated by the historical transformations brought about by the crisis of feudal society and the religious schism. It is therefore necessary to analyse the theological and intellectual context of the period in order to understand the origins of the infamous witch hunts.

Although witch trials of the early modern period were predominantly rural phenomena, the earliest cases before 1500 often originated in urban centres. Many of these prosecutions, however, were rooted in tensions emerging from nearby agrarian communities. As

Kieckhefer (

2021) explains, the surviving records suggest that accusations of witchcraft reflected broader processes of social dislocation—particularly the breakdown of traditional family structures and the demographic upheavals following the Black Death. The migration of disoriented rural populations into the cities, together with the introduction of inquisitorial procedures into municipal courts, fostered an atmosphere of instability and mistrust that encouraged the spread of moral anxieties surrounding women’s roles within the community (pp. 94–95).

Moreover, these accusations were seldom arbitrary; rather, they tended to arise from pre-existing social conflicts. Kieckhefer further observes that anthropological studies have shown how charges of sorcery often emerged from quarrels or long-standing resentments between individuals or neighbours. In many cases, the accused occupied a position of perceived moral superiority, prompting the accuser to project his own guilt or frustration onto her through an allegation of bewitchment. Feelings of personal grievance and moral unease thus became intertwined with the broader dynamics of fear and control that underpinned early modern witch persecutions (

Kieckhefer 2021, p. 98).

It was with the dissemination of several demonological treatises, that fascination and curiosity about the subject began to flourish, not only among scholars but also among the general public, heavily influenced by eschatological beliefs. Few works reached the notoriety and transcendence of the Malleus Maleficarum [The Hammer of Witches] by Heinrich Kramer (1487), which, since its publication in the fifteenth century, became the foremost reference on demonology and witchcraft. Its success was not an isolated event but rather the starting point of a new current of thought that managed to permeate various literary and pictorial works, as will be explained later.

This theological climate can be further understood in the light of Walter Stephens’s analysis in Demon Lovers: Witchcraft, Sex, and the Crisis of Belief (2003). Stephens argues that early modern demonology was not merely a catalogue of diabolical phenomena but a response to a profound theological anxiety. The obsession with proving the reality of witches and their alleged pacts with the Devil, he suggests, stemmed from a deeper fear: the fear of disbelief itself. By demonstrating the Devil’s tangible influence in the world, theologians sought to reaffirm the existence of God and the veracity of Christian doctrine at a time when scepticism and rational inquiry were beginning to undermine faith. The female body thus became the site where this crisis of belief was materialised and contested—a symbolic battlefield on which the Church attempted to stabilise the fragile boundaries between reason and faith, nature and the supernatural.

The Malleus Maleficarum therefore served as a manual for the identification, persecution, torture, and elimination of witches, linking women closely and almost naturally with the Devil. In fact, early studies did not focus so much on the supposed innate evil of witches as on the Devil’s wicked arts to act against man through women. It was the imperfect nature of a woman that made her an easily manipulable instrument of diabolical forces. So much so that the doctrine of the Church frequently denounced women as weak creatures, inclined to temptation and driven towards evil by concupiscence.

Much of the modern interpretation of this influential demonological work relies on distorted translations that sensationalise or simplify its content. As Stephens observes, overreliance on its most infamous section—Part I, Question 6, a compendium of every misogynistic trope the author could find—has led twentieth-century readers to mistake the entire treatise for a straightforward expression of clerical misogyny (

Stephens 2003, p. 33). Yet this narrow focus obscures the text’s more complex theological and mechanical structure, in which the discourse on women serves as a vehicle for a broader inquiry into evil, sin, and the credibility of belief itself.

Although the misogyny of the Kramer’s treatise is evident and undeniable, Stephens warns that its scope has been vastly overstated. The notorious passages concerning “women’s sexual powers” constitute barely 2.5 percent of the entire work (

Stephens 2003, p. 34). As he asks, paraphrasing Umberto Eco, “is it economical to presume that the ideological purpose of the

Malleus maleficarum is to justify hatred of women?” The text’s primary concern, he argues, was to defend the reality of demons and to theorise physical interaction between the human and the supernatural—a project in which the female body was instrumentalised as theological evidence.

Stephens also points out that the foundational text of witch-hunting discourse betrays its author’s uncertainty about the very claims he advanced. Kramer’s insistence on the “expert testimony of the witches themselves” as proof of demonic copulation exposes the circular logic of the text (

Stephens 2003, p. 35). Women’s confessions served simultaneously as evidence and justification for belief, transforming the female body into empirical proof of the supernatural. The

Malleus Maleficarum thus becomes not merely a manual of persecution but an anxious theological experiment in which faith sought validation through the corporeal.

Michelet’s (

1883) historical reflection makes this anxiety visible, situating the emergence of the witch within the Church’s own crisis of faith: “At what date, then, did the Witch first appear? I say unfalteringly, ‘In the age of despair’: of that deep despair which the gentry of the Church engendered. Unfalteringly do I say, ‘The Witch is a crime of their own achieving’”.

Yet this was not always the case: for years, so-called witches had constituted the only available healthcare resource in rural communities. They were known as wise women or healers who employed natural remedies, whose formulae were transmitted and refined from generation to generation. As

Charlotte Broad (

2009) notes, they were “possessed of certain powers, of knowledge of the body and the remedies to heal it, of spells and potions to satisfy desires, to fulfil passions”. Within a society characterised by magical thought (

Harris 1985), this gift would ultimately turn against them (

Fisher 2000), to the extent of being accused of practising sorcery: it came to be believed that witches themselves cursed people with illness and poor harvests.

Ye magian queens of Persia; bewitching Circe; sublime Sibyl! Into what have ye grown, and how cruel the change that has come upon you! She who from her throne in the East taught men the virtues of plants and the courses of the stars; who, on her Delphic tripod beamed over with the god of light, as she gave forth her oracle to a world upon its knees;—she also it is whom, a thousand years later, people hunt down like a wild beast; following her into the public places, where she is dishonoured, worried, stoned, or set upon the burning coals!

“The witch passed from occupying a central place in social health to becoming the new scapegoat of a society that dispensed with her knowledge in favour of the growing concentration of medical knowledge” (

Brinkop 2009, p. 43). This was the consequence of a latent confrontation between empirical female knowledge and male scientific knowledge, a conflict that would culminate in the establishment of medicine as a science reserved exclusively for men, thereby excluding women from its practice.

In other words, women who did not conform to the project of being married in the Catholic Church, bearing children, and dedicating themselves entirely to domestic duties were liable to be accused of witchcraft—still more so if they possessed knowledge of botany or alchemy, if they engaged in healing practices within their communities beyond official medicine, or if they led or participated in processes of heresy or peasant subversion in a context of pressing needs, precarious resources, and explanations framed in magical-religious terms.

3. Mythology, Literature and Folklore: Lilith, the Archetypal Witch

It is impossible to address this subject without considering the figure of Lilith who, despite her relative obscurity—owing to the scant biblical references—has retained her vitality as a

femme fatale1 within contemporary mass culture. She may be regarded as the first liberated woman in the history of humankind and, therefore, the archetypal witch. The earliest representations of Lilith derive from Sumerian mythology and depict her as a winged young woman, resembling the Greek goddess Nike, an iconography far removed from the monstrous image that Hebrew culture would later ascribe to her as a woman of the night. This transformation was the result of the imposition of a renewed religion, marked by the presence of predominantly male deities symbolising an androcentric political power.

“The belief in sorcery and witchcraft is probably as old as mankind. When primitive man is confronted with something incomprehensible, the explanation is always sorcery and evil spirits… it is the result of naïve notions about the mystery of the universe” (

Christensen 1922).

According to the myth, prior to the existence of Eve, God created Adam and Lilith from clay as equals. Since Lilith had been fashioned from the same clay as her companion, she did not consider herself inferior to him and refused to submit to Adam’s sexual demands, which contradicted such equality. Her refusal led her to flee Paradise and to be condemned to clandestinity, stripped of her divine attributes and transformed into a demonic figure as the concubine of the devil. Lilith was thereafter replaced by Eve, as Hebrew writings attest and biblical texts largely omit, save for a brief reference in Isaiah 34:14 (

Bible 1989).

Lilith’s decision to live her sexuality freely led the patriarchal discourse to elevate her as the antithesis of the obedient and sexually passive companion, transforming her into a woman of monstrous nature. The conception of medieval witchcraft was, therefore, inherited from this Hebraic tradition. Nonetheless, the myth of Lilith loses its weight in the misogynistic representation of women in favour of the biblical figure of Eve, since the discourse of the Middle Ages was constructed upon the idea of original sin. At this juncture it is pertinent to recall the figure of Pandora, Hesiod’s Greek antecedent of Eve.

There are many names by which the monstrous woman has been known throughout time and, in particular, within mythology: Lamia, Sphinx, Harpy, Sibyl, Siren… Even Cleopatra was regarded in Ancient Egypt as a

femme fatale, a term later supplanted by the figure of

la belle dame sans merci2 in numerous works of art. Nor should we forget the three archetypal witches of the Greco-Roman period: Hecate, Circe, and Medea.

History thus proves to be replete with innumerable malevolent female figures, each bearing a different appellation, yet all guilty of the same sin: leading man to his perdition.

The literary image of women reflects a history determined by the hegemony of phallocentrism. Men have written, interpreted, and lived history from an exclusively masculine perspective that has undervalued female experiences and distorted the image of women within diverse artistic manifestations. Knowledge is not neutral, and the imprint of patriarchy has indelibly marked our understanding of historical becoming.

The representation of women as demonic beings is also nourished by Oriental myths. In these cultures, we encounter representations of witches such as the Yama-uba, a spirit of Japanese folklore dwelling in the mountain forests, closely resembling Baba Yaga of Slavic mythology. Similarly, ghosts with unfinished business are known as yūrei. Indeed, in Japanese culture the colour white is associated with death; for this reason, yūrei are commonly depicted in white robes, in contrast to the dark garments of most Western creatures, witches included.

“In general, European communities have misinterpreted the figure of the witch. She assumes different meanings in each cultural context and has been classified on the basis of erroneous assumptions; consequently, she has been misrepresented across a wide range of texts” (

Broad 2009, pp. 9–10).

4. The Earliest Representations in Art: When Nakedness Constituted the Witch’s Primary Garment

It is from the Renaissance onwards that the female figure emerges as a clear erotic exponent in the visual arts through the proliferation of Venuses. Within this iconography we discern the representation of male sexual desire: women uninhibited, surrendered to carnal pleasure, awaiting to gratify the needs of man. As Golrokh Eetessam Párraga affirms, the representation of women in the plastic arts is that of a passive recipient of male worship, a passive embodiment of a sexuality that has taken in male desire its centre, beginning, and end (

Eetessam Párraga 2009, p. 236).

Yet, conversely, there exist works in which such dependence is absent, foregrounding instead the female monstrosity already discussed, wherein a man is rendered a slave and victim of a woman.

In Ian Watt’s words (

Watt 2000): “The tabooed object is always an indication of the deepest interest of the society that forbids. All the forces that combined to intensify the prohibitions against sexual activity outside marriage, tended in practice to increase the importance of sex in the total picture of human life”. The representation of female nudity in Renaissance art illustrates this paradox precisely: the more insistently sexuality was censured, the more obsessively it came to dominate the visual imagination.

A similar dynamic is identified by Claudia Brinkop, who poses the following question: “What became of this body and its sexuality during the Renaissance? On the one hand, it was represented in a sublime manner, exalted, celebrating nakedness and the erotic in art and poetry; on the other, it was demonised, and women who enjoyed it were associated with Satan” (

Brinkop 2009, p. 41).

This dichotomy would be accentuated above all through the work of Henry Fuseli, precursor of surrealism and endowed with a peculiar taste for the grotesque and the dark, who represented the terror concealed in dreams and the subconscious—attributed, of course, to the female gender. In the following painting (

Figure 1), Fuseli anticipates the yet-to-be-fully-formed image of the depraved woman. It illustrates a passage from

Paradise Lost3, in which the nocturnal witch, the Greek goddess Hecate, rides the air and goes to dance with her sisters, lured by the scent of infant blood.

This fascination with the figure of the witch as devourer of innocence, so vividly embodied in Fuseli’s nocturnal vision, finds its theological origins in the early demonological imagination. As Stephens notes, “Witches kill children. Witches are cannibals, and their favourite food is children, as Hansel and Gretel found out” yet these gruesome images were not inventions of folklore alone; they were adopted and theologised by witchcraft theorists to defend the logic of divine providence (

Stephens 2003, p. 241). The infanticidal witch, far from being a mere monster, became essential to sustaining belief in the sacramental efficacy of baptism and, by extension, in the goodness of God. Her crimes served to rationalise why the innocent could suffer and die despite divine protection: through her, theologians reaffirmed the necessity of the sacraments in a fallen world. The cauldron—her most infamous tool—thus emerged as a blasphemous inversion of baptismal water, a vessel in which salvation was symbolically boiled away.

Subsequently, the witch would be transformed into Salome by Gustave Moreau, who laboured for years on this biblical figure associated with virginity and death, thus representing another femme fatale of history. She is, therefore, another figure maligned by the biblical tradition, accused of using her charms to seduce man.

The baton would then be taken up by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who inscribed in the women of his paintings many of the iconographic topics derived from mythology, laying the foundations for the visual imaginary enveloping the femme fatale.

This underlying eroticism—at times explicitly unsettling—brought to light a type of woman as sensual as she was strange, already foreshadowing the principal traits of the fin-de-siècle femme fatale. The most recurrent motifs were the absent gaze, the lax posture, faintly provocative, and physically the abundant hair, loose, at times curly or wavy, frequently red, and the cold, penetrating green eyes.

It is noteworthy to observe how the cult of feminine beauty was represented from both gendered perspectives. Indeed, it is difficult to believe that two contemporaneous works so closely related as those illustrated below (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) could project such divergent connotations. On the one hand, Julia Margaret Cameron, great-aunt of Virginia Woolf, rejects the vulgar and sensual representation of women in favour of a more romantic vision suggestive of emotion and spirituality. By contrast, Rossetti presents a goddess of carnal love who is the bearer of sin through the apple and who fulfils to the letter all the aforementioned stereotypes.

Later, Franz von Stuck would once more resort to the female gender to embody the allegory of sin (

Figure 4), as would his contemporary Jean Delville, who referred to women as an idol of perversity. Both were exponents of Symbolism and of the contemporary fascination with occultist painting. In their canvases, the scene is shared by a serpent, a creature associated with original sin and the devil. Indeed, in Delville’s work

L’Idole de la perversité [The Idol of Perversity] (1891) there are certain similarities with a

Gorgon4. This visual and symbolic lineage finds a compelling echo in

Lilith (1889) by John Collier, who significantly titled his painting after the first witch—silenced and forgotten in patriarchal tradition—thus reviving the mythic archetype of the rebellious woman as a source of both desire and condemnation (

Figure 5).

In order to satisfy their sexual desires, demons were believed to require possession of or metamorphosis into animals through which copulation with witches might take place. Medieval imagery designated he-goats, toads, black pigs, wolves, and cats as the principal instruments through which the devils carnally united with witches. The association of witches with these nocturnal, sordid, lugubrious, and at times grotesque creatures was fuelled by the descriptions of preachers and theologians, which fired the popular imagination, and by the inspiration of artists who gave plastic form to this imaginary (

Beteta Martín 2014, p. 300).

This supposed sexual character of witches alluded to an animal eroticism, referencing the practice of zoophilia originally tied to ritual contexts of a mythological scope. This would be expressed in other works, such as that of Federico Beltrán Masses, who drew upon the biblical character of Eve to link her with the

femme fatale. In the painting (

Figure 6), a woman appears in ecstasy, surrounded by a serpent that coils around her erogenous zone, making its way towards her mouth: the image of a woman succumbing to carnal pleasure and departing from a sexual perception confined solely to reproduction.

The bestial dimension of witchcraft further reveals the physical and moral transgressions projected onto the female body. The companionship between witches and cats soon became a commonplace of early modern demonology: the witch’s “familiar”—a domesticated demon incarnated in animal form—was interpreted as tangible proof of her allegiance to the Devil. She was believed to nourish this creature from a hidden “witch’s teat”, an act perceived as both diabolical communion and perverse maternity (

Stephens 2003, p. 283). Peasant folklore, intertwined with theological speculation, imagined that witches could transform themselves into cats or wolves to attack children and wander the night.

This fusion of a woman and animal found one of its most evocative expressions in

La femme chauve-souris [The Bat Woman] by Albert Joseph Pénot (1890). The painting presents a hybrid creature—half human, half bat—suspended in a dark and nebulous atmosphere. The nocturnal setting and her ambiguous stance suggest that she moves through the night as a predator, perhaps a witch herself, her wings extending from the shadows as emblems of occult power. Pénot’s bat woman epitomises the fascination with female metamorphosis at the fin de siècle: a creature of desire and fear, endowed with primitive and hidden forces capable of subduing those who dare to explore the depths of darkness (

Figure 7).

Such metamorphic depictions derived directly from the demonological tradition that associated witches with their infernal lovers. Through their sexual unions with demons, witches were believed to acquire not only their powers but also their physical traits. Over time, the demonic wings of these spirits were transposed onto the bodies of women, fusing the sensual with the monstrous. These iconographic transformations, both erotic and terrifying, illustrate the way visual culture absorbed theological narratives of corruption into aesthetic form.

Visual culture of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries would further intensify these associations through unmistakably sexual imagery. In certain engravings, the witch’s pitchfork or broom assumes a strikingly phallic character, “a surrogate instrument of demonic intercourse”, sometimes adorned with tubular objects that “cannot help suggesting penises in the total context of the pictures” (

Stephens 2003, p. 300). These hybrid forms—half erotic, half grotesque—reinforced the conviction that female transgression was not only spiritual but also physical, a corruption inscribed upon the body through its contact with the animal and the demonic.

As Walter Stephens explains, such monstrous representations of demons carried not only moral but also epistemological significance: “Their grotesque bodies demonstrated that they could become palpable and real” (2003, p. 118). By endowing the demonic with material form, artists provided visual proof of its existence. The sexualised violence and corporeal excess of these scenes underscored the theological conviction that evil had to be incarnated in order to be believed. Within this framework, the female body functioned as both mirror and measure of that incarnation—simultaneously desired, feared, and condemned.

In this way, a woman was transformed into a sinful being who personified that which was simultaneously feared and desired. For, as Beteta Martín affirms, the monstrous is intimately bound to fear, and this fear of alterity constitutes one of the fundamental pillars that engender rejection of the transgressor (

Beteta Martín 2011, p. 30).

Such rejection is made manifest in the work of William Mortensen, dubbed “the Antichrist of Pictorialism”, who was condemned to ostracism for his numerous theatricalisations of witchcraft, as is evident in his Preparation for the Sabbat (1935). In this photograph, two witches are depicted: the elder smears an unguent upon the back of the younger, who poses naked in a disinhibited manner, holding a stick between her legs as though it were a broom.

According to Stephens, witchcraft theorists conceived of maleficium as a countersacrament, a perverse reflection of Christian rituals (

Stephens 2003, p. 184). Like the sacraments, witchcraft required perceptible effects to prove its efficacy: the visible marks on the body, the gestures, the substances, and the ceremonies that materialised invisible energies. This inversion of the sacred made witchcraft the tangible evidence of a corrupted faith—one that sought to verify the spiritual through the physical. In this sense, the witch’s body itself became both altar and instrument, the locus where the sacred was mimicked and perverted through sensory experience.

Once prepared and already on their way to the Sabbat, the witches are presented in the following work of Falero (

Figure 8), where nakedness once again becomes the principal attire of this figure, enveloped in a tenebrous yet seductive atmosphere.

It is hardly surprising that, following such representations and the emergence of the New Woman, men felt threatened by the growing empowerment of the female gender and rejected the adult woman in favour of a fascination with puerile innocence.

“Thus, by transgressing limits and boundaries, and from their marginality and peculiar mode of relating to the world, to nature, and to people, witches occupy the place of the Other, the repressed, the sinister feminine, the reverse of the order of passion and desire” (

Broad 2009, p. 8).

5. The Contribution of Fashion to the Process of Mythification

Long before the Wicked Witch of the West donned her iconic attire, the fashion industry was already drawing upon the collective imaginary to market Ipswich ladies’ stockings: “There’s modern witchcraft in the flawless knitting of Ipswich stockings. There’s witchery in the sheer silken web of them, and in their exquisitely shaded colors”, reads the text accompanying the image (

Figure 9). It may appear anecdotal, yet if we consider the words inscribed on the wooden stocks restraining the female figure: “Behold ye people a witch”. It is striking that such an illustration should appear in an advertisement in a women’s magazine of the time, given that little more than a century earlier, women were still being executed for witchcraft in Europe

5.

Because of such representations and the associations they engender, it is hardly surprising that certain stereotypes have been perpetuated over the years and appropriated by the catwalk, with their meanings distorted to suit convenience.

“This is precisely what occurs with stereotypical beliefs concerning the characteristics of men and women today. Everyone assumes that women are this way or that way, as though these peculiarities were constitutive attributes of the feminine essence, immune to debate” (

Guil Bozal 1998, p. 95).

Thus, we encounter proposals such as Martine Sitbon’s Spring/Summer 1993 collection, in which the witch of the Ipswich stocking advertisement appears to have come to life. The model wears a characteristic pointed hat covered by a kind of veil reminiscent of the

hennin6 worn by medieval women, which may well constitute the origin of this potent symbol. Be that as it may, the most likely association of this accessory with witchcraft derives from the Church, which historically established a connection between certain fashions and sin or evil. One cannot forget, for example, the conical headwear worn by those tried by the Inquisition.

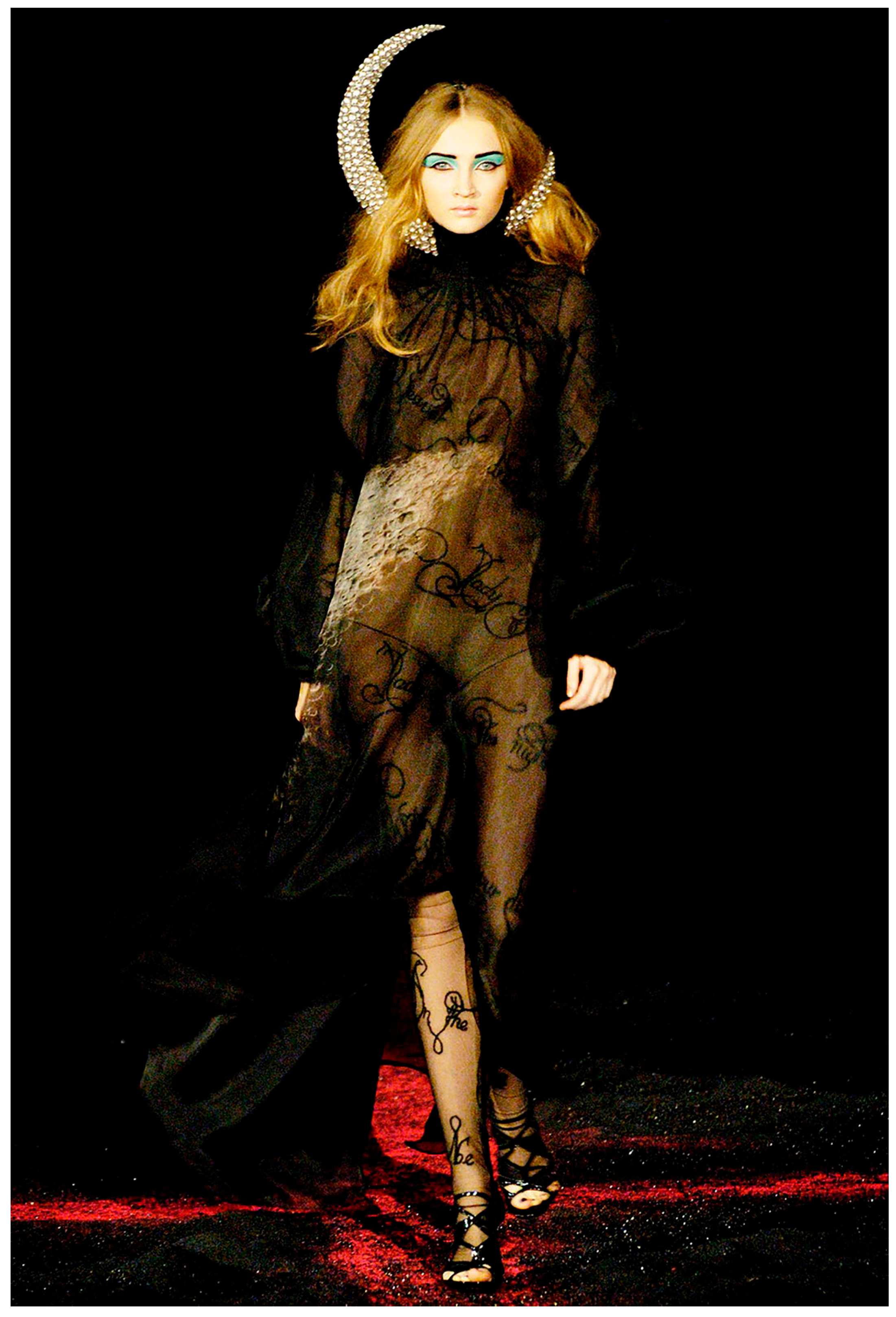

In explicit memory of one of the first victims of the witch hunt, Elizabeth How, Alexander McQueen’s 2007 collection (

Figure 10) honours his ancestor, unjustly condemned and hanged in 1692. Through his garments, the designer revaluates certain pagan and Christian symbols attributed to witches, such as pentacles and crosses, as well as the principal astral sign linked to feminine energy, the moon.

Also drawing upon a real character, Saint Laurent’s 2013 runway show (

Figure 11) took as its muse the American artist and occultist Marjorie Cameron, the living image of a liberated woman ahead of her time, whose work was inspired by sex, drugs, and the occult sciences. The collection may be described as a rock Sabbat of the seventies, the decade in which pioneering women appropriated masculine fashion. Indeed, it was Yves Saint Laurent himself who challenged at that time the prevailing notion of femininity by proposing the tuxedo as female attire; it was therefore coherent that his brand should be the first to present us with a masculinised witch.

Sex, drugs, and rock & roll would give way to a disco atmosphere in which Ashish’s witches (

Figure 12) became the protagonists of a decadent party. The dance floor was plunged into profound darkness, broken only by the sparkle of sequins and mirrored balls.

It was precisely this essence of glam rock, combined with the darker, more pessimistic aesthetics of Romanticism, that transformed Veronique Branquinho’s witches (

Figure 13) into figures who might well have stepped out of a Fuseli canvas: a mystical woman with fatalistic overtones, dressed in a sequinned gown and a sixteenth-century ruff collar—traditionally reserved for men, while women wore a larger version covering the chest, known as

gorguera. This accessory indicated high social standing, thus once more representing a powerful woman.

Not all, however, is despair and pessimism. The more optimistic face of Romanticism was revealed in Viktor & Rolf’s 2019 collection (

Figure 14), which alluded to a form of spiritual

glamour—in the original sense of the word, referring to a spell cast by witches, in this case to transform a general feeling of fatality into positive action. A return to the primordial essence of the witches, women close to nature who employed plants. Similarly, the designers revived ancient dyeing processes, boiling fabrics with pigments in a cauldron, as if concocting a potion, to achieve a specific shade known as

Burgundian black. This bluish-black tone, characteristic of Flemish painting, originated in the region of Burgundy.

Much more naïve is Ryan Lo’s vision (

Figure 15), which reworks the classic princess tale in a narrative attempt to imagine witches enjoying a happy ending, thereby banishing the darkness traditionally associated with their image. Pastel-coloured elements complete the attire with a broom. The association of this object with witchcraft stems from transcriptions of the Salem trials, in which the accused confessed to applying plant-based hallucinogenic ointments with the handle of a broom to their intimate parts, generating a magical state of levitation.

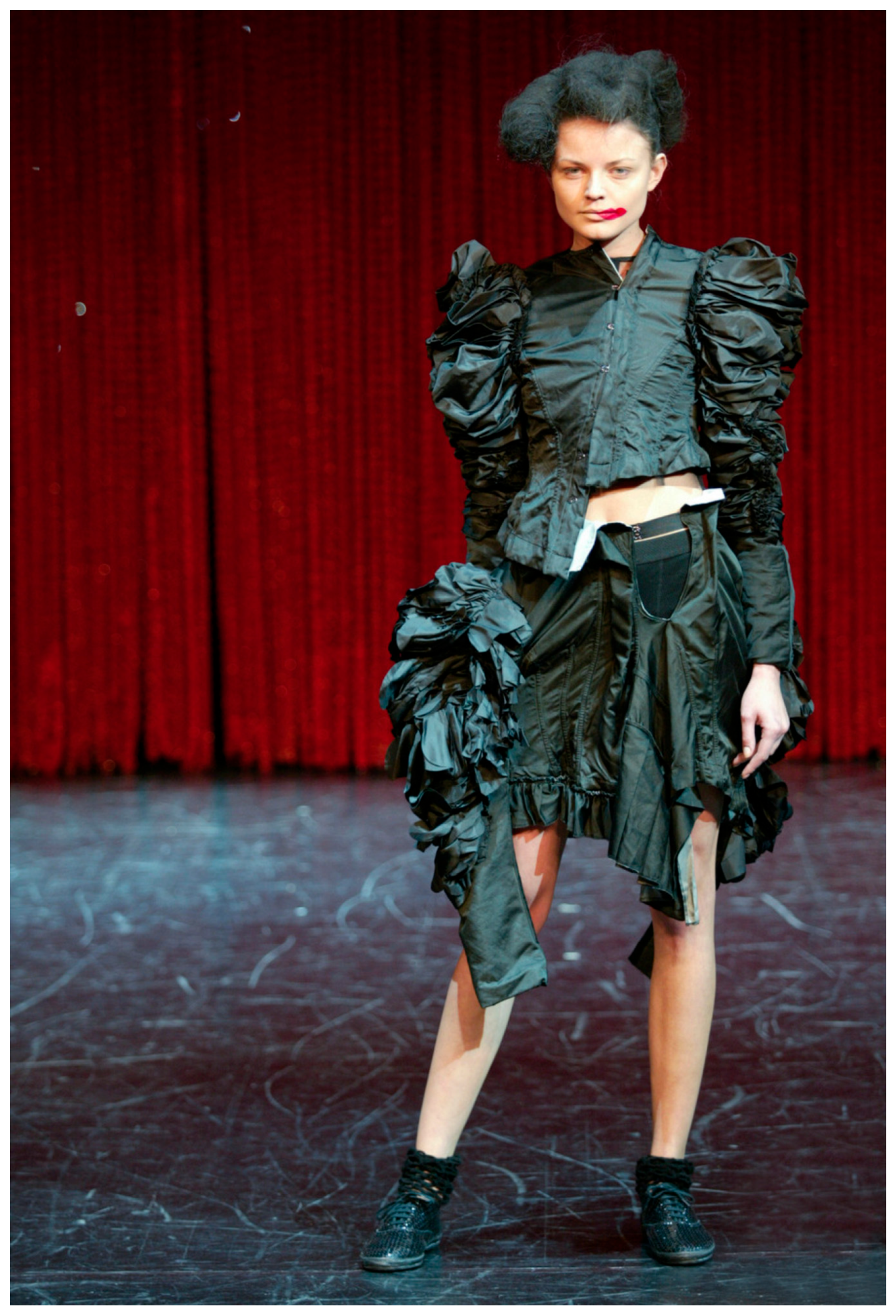

This renewed vision seems to seek to leave behind the monstrous-female image, offering the viewer a more acceptable representation of the empowered woman. Comme des Garçons had already presented such a figure in its 2004 collection (

Figure 16). In the words of designer Rei

Kawakubo (

2015): “I was thinking of witches. Witches in the original sense of the word, in the sense of a woman who has power. The original witches were benevolent, but because people did not understand them, they were intimidated. They left us with a negative image of them”. The collection presented a Victorian witch exploring gender limitations and breaking with imposed restrictions. Skirt ruffles were transformed into sleeves that hung down, coexisting with garments borrowed from masculine attire.

But what if these powerful witches were to act with boldness? Kawakubo went a step further with her

Blue Witches collection in 2016 (

Figure 17). Eccentricity flooded the runway with artificial volumes that defied any banal discourse on functionality or commercialisation. Kawakubo’s witches were proud of what they were: strong, misunderstood women who reclaimed their indomitable red manes and leapt into blue, symbolising their yearning for freedom.

Nor did Kawakubo’s message end there. Her Autumn/Winter 2019 collection,

Gathering of the Shadows (

Figure 18), again inspired by witches, was conceived as a declaration of intent. Through it, she highlighted humanity’s potential to enact both good and evil. In its staging, as the models grouped in a circle at the close of the show, the spectator might glimpse, in a brief flash of hope, some form of feminine ritual to banish all ills. A gathering of shadows, in which the protagonists were hoods, fishnet stockings, and the interplay of textures.

Remaining faithful to the essence of the Sabbat, straddling runway and film, is John Galliano’s recent Haute Couture Artisanal collection. In it, he explored the desire for a new utopian youth connected to the cycle of life, time, and nature—a return to the roots. Here the term witch appears in its purest sense: mystical women gathering and dancing in the moonlight. Some wore animal masks while others bore sceptres as symbols of their power.

Thus, highly distinct styles are presented. On the one hand, the sombre garments and other clichés associated with the wicked witches of fairy tales. On the other, darkness clashes stylistically with the more innocent aesthetics of pastel-coloured dresses and the sophistication of diaphanous fabrics. And, finally, straddling these two extremes, a strong, self-assured woman indifferent to gender or social condition, represented through ample volumes and vibrant colours.

6. The Figure of the Witch and Other Monsters in Cinema

The big screen constitutes a significant testimony to the extent to which fascination with the figure of the witch is rooted in popular culture, omnipresent across diverse artistic expressions. It is therefore unsurprising that, as a reflection of the social moment, this tendency also established the witch as a climatic inspiration for cinema.

As Manolo Dos observes, “The golden age of Danish silent film found in the erotic melodrama its principal resource: fatality, intertwined with woman, sin, and sex, gave rise to a new cinematic typology of the wicked woman indebted to past cultural traditions” (

Dos 2009, p. 137). Films such as

Afgrunden [The Abyss], directed by Urban Gad (1910), epitomize this moment: the female protagonist’s sensuality and transgression mark the emergence of a new moral and visual code that would influence later representations of female evil and desire.

This depiction of women, as both alluring and threatening, echoes what Barbara Creed defines as the monstrous-feminine—a figure shaped by patriarchal fears of female power and corporeality. As

Creed (

1993) argues, cinema often constructs a woman not simply as others but as a disruptive force that blurs the boundaries between purity and impurity, desire and danger. Her perspective helps illuminate how the archetype of the witch, like that of the femme fatale, embodies the persistence of these cultural contradictions in visual narratives.

Costume designer Vera West would be the one to export this archetype of the wicked woman and to bring it to life, disseminating it internationally when she was hired in 1927 by Universal Pictures as head of costume. At that time the studio had decided to invest in a series of horror films that would become today’s classics, establishing West as one of the first creators of monsters. To her we owe the current imaginary of many femmes fatales: for instance, the long, silky garments of Dracula’s concubines, or the iconic white gown of The Bride of Frankenstein, through which horror costume design ascended to the heights of Haute Couture.

Despite her contemporaneous vision and groundbreaking proposals, the rules laid down by Hollywood remained highly strict: women could only play roles in which they were either victims of the monsters, or, in rare cases, the monsters themselves.

“Two broad labels may encompass the wide variety of female roles in patriarchal cinema: the wicked and the foolish, corresponding to the dual way of conceiving female presence on screen—either sublimated and fetishised, or mocked and despised” (

Guarinos Galán 2008, p. 115).

Yet

Guarinos Galán (

2008) argues that such simplification is insufficient. While there is a tendency to crystallise the prototype of the

femme fatale or the good girl, traditional roles have evolved, giving rise to more complex characters. The range is considerably broader, although at root all figures feed upon the same misogyny. According to him, the most common stereotypical female figures are: the good girl, the angel, the virgin, the devout/spinster, the wicked girl, the warrior, the

femme fatale or vamp, the

mater amabilis, the

mater dolorosa, the punitive mother, the stepmother, the mother of the monster, the childless mother, the Cinderella, the

turris eburnea, the black queen/witch/black widow, the villainess, the superheroine and the dominatrix (pp. 116–18).

In line with this classification, a series of films has been selected in which the contemporary witch figure acts in accordance with some of these categories, and their visual representation has been analysed.

First, the role of the good girl or the Cinderella is embodied by the protagonist of The Love Witch (2016) directed by Anna Biller, naïve and eager to please her man at all costs, as if patriarchy had brainwashed her. A lethal beauty, obsessed with finding her Prince Charming and willing to do anything to obtain him. Between irony and truth, the film speaks to the conventions imposed upon women in matters of love. Its colourful, carefully crafted aesthetic is typical of 1960s and 1970s cinema, with each shot strategically framed and every object meticulously placed.

With the air of the good girl aspiring to sainthood, the protagonist of

Saint Maud (2019) from Rose Glass, becomes a wolf in sheep’s clothing, embodying the figure of the angel. The young nurse attempts to save her patient’s soul from the devil’s sharp claws, though it remains unclear whether this modern martyr, condemned to self-destruction, devotes her faith to good or to evil—a twisted vision of the terrifying character inherent in religious fanaticism. The film’s imaginary is steeped in the aesthetic of William Blake, particularly in its fusion of mystical revelation and corporeal torment. Like Blake’s visionary engravings—where the divine and the diabolical coexist within the same ecstatic frame—Saint Maud translates spiritual anguish into physical expression, its flickering lights and convulsive bodies recalling the tension between transcendence and decay that defines Blake’s symbolic universe. Tinged with Symbolism and interwoven with the brutality of

body horror7, it visualises faith as both illumination and self-annihilation.

In its younger version of the angel, we encounter the wicked girl, provoking sexual tension among middle-aged men impurely attracted to her. In this case, the protagonist of

Akelarre (

Agüero 2020) by filmmaker Pablo Agüero, uses her youth to beguile Judge Lancre and subvert his religious convictions, seeking thereby to avoid the execution to which she and her friends have been unjustly condemned for witchcraft. “I love the idea that festivity is a form of rebellion. Their way of rebelling is joy. Gloom lies in the gaze of the other, which transforms sexual and intellectual freedom into something dark. And that persists: the culpabilisation, the condemnation of female freedom. We must create fictions that change the system, telling stories from other perspectives” (

Agüero 2020). Costume is centred on fabric: through their richness, noble characters are distinguished from the poor. The women wear natural textiles of the period, such as wool, canvas, and linen, while the Rostegui clan is dressed entirely in black—above all the protagonist, who shines thanks to rich fabrics such as silk, affordable only to the nobility. An aesthetic born of the interaction between inquisitorial stereotypes and folkloric culture.

Equally the ruin of men is the femme fatale or vamp, though she desires more than male downfall: the illusory ideal of beauty and eternal youth. The Neon Demon (2016), by director Nicolas Winding Refn, presents witches bound to the frivolous world of fashion, whose principal concern is the pursuit and possession of sublime beauty. To achieve it, they will devour their companion and bathe in her blood, absorbing her strength and purity—just as Cronus devoured his children to avoid being dethroned, or as the legend of Countess Elizabeth Báthory narrates. Many of the costumes are sourced from major designers, including several looks from Saint Laurent’s Spring/Summer 2015 collection or Marina Hoermanseder’s debut collection, inspired by orthopaedic devices and severe skin disorders. Combined with vibrant colours, blood, and glitter, the aesthetic lies midway between surrealism and gore. Indeed, makeup, one of the film’s main protagonists, is influenced by the 1990s animated series The Ren & Stimpy Show created by John Kricfalusi, transporting us to a psychedelic world.

Also linked to blood and bodily fluids is

In Fabric (2018), shot under the direction of Peter Strickland, which depicts the archetype of the black queen/witch/black widow. According to

Guarinos Galán (

2008): “depending on the genre in which they are inscribed, they may be monstrous or intoxicatingly beautiful, but they will always be perverse and disposed to evil—either to dominate something or someone, or simply for sadistic pleasure”. Its imaginary oscillates between the macabre and the mordant, with an aesthetic of saturated colours reminiscent of Italian

giallo8. Pale skin, period dress, and a teased wig clothe the witch of this tale, recalling those of

The Witches (1990) directed by Nicolas Roeg, when they revealed their true aspect, exposing their baldness. The plot centres upon a department store during the sales season, where the protagonist discovers a supposed bargain: a beautiful red dress that she purchases under the witch’s persuasion. It soon exercises a powerful influence over her, and only too late does she realise she has fallen victim to the curse embedded in the garment.

A modern variant of the black queen/witch/black widow is the dominatrix. A clear example is La Vénus à la fourrure [Venus in Fur] (2013), based on Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s 1870 novel. The depravity of this erotic work is multiplied in Roman Polański’s adaptation, in which the two characters undergo a metamorphosis culminating in an exchange of roles. As the fiction progresses, the male protagonist becomes engulfed by the ecstasy of the moment and ultimately succumbs to submission. Here the witch is depicted as powerful, exploiting her position of dominance to ridicule the man, control him, and do with him as she pleases. She does so through the sadomasochistic aesthetic, clad in leather and stiletto heels, in stark contrast with the decadence of the setting.

In the same cold, inflexible vein as the dominatrix, the

turris eburnea or ivory tower is inaccessible, which renders her all the more desirable. Gaspar Noé presents his witches thus, impassive at the prospect of being burned alive. Equally cold is the atmosphere, enveloped in a chaotic, intermittent interplay of

RGB9 lights, interrupted only by the infernal aesthetic of flames and torches. In

Lux Æterna (2019), the audiovisual is at the service of presenting Saint Laurent garments. The film emerges as a new proposal within the artistic project

Self, which seeks to convey the essence of the brand through the eyes of various artists: in this case, the director proposes a most chic witch-burning. Despite being bound and on the verge of incineration, we see the models reclining serenely in their finery, as though in a fashion shoot. In a sense, this mirrors the way the fashion industry presents models: expressionless women who appear to languish.

The opposite version is embodied by the virgin, devout and chaste. The innocence of the protagonist of The Witch (2015), helmed by Robert Eggers, aligns perfectly with the idea of the submissive virgin, shattered as her family turns against her. The story unfolds in a rural setting in seventeenth-century New England, and the family seems to have been painted by Rembrandt himself. Its striking cinematography conveys a sombre, primitive atmosphere in which religious fanaticism once again subjugates women.

Female agony does not end here; it continues with motherhood. The mater dolorosa [mother of sorrows] cannot bear the anguish of witnessing her children’s suffering, still less imagining that it might be her fault. This is precisely the fate of the protagonist of Antichrist (2009), a film by Lars von Trier, whose “sexual voracity” precipitates the death of her child. The trauma triggered by this event leads the film’s aesthetic to probe representations of the psyche, resorting to the sublime and horrific aspects of nature, imbuing it with a dreamlike yet gruesome quality. The guilt attached to her sexuality leads the witch to reject every source of pleasure—just as Lilith’s decision to live her sexuality freely was precisely what rendered her a woman of monstrous nature.

The reverse face of motherhood is the punitive mother or stepmother, embodied in

Suspiria (2018) as the

mater suspiriorum [mother of sighs]. The severe director of the dance academy exercises her authority by curtailing the freedom of her “daughters”. Luca Guadagnino portrays the monstrous, aged mother, envious of her disciples’ youthful beauty and femininity. Such femininity pervades the film’s aesthetic. Costume designer

Giulia Piersanti (

2018) explains how she began by researching witches’ dress and its symbolism but became more interested in the vision of artists such as Louise Bourgeois and Rebecca Horn, who use the female body as a tool. Thus, although the plot unfolds in the 1970s, many garments are inspired by the work of these two artists. Piersanti drew upon the floral prints of the period, reworking them into her own version of arms, legs, breasts, and vaginas. All this, without neglecting the clear references to Dario Argento’s original film (1977), which shaped the horror genre with its wallpaper designs and hyper-stylised compositions.

7. Conclusions

It is important to clarify that the history of witches and the figure of the witch are not the same thing. The former is a narrative constructed around the phenomenon of the witch hunt, while the latter is a symbolic production, a social representation that conveys different contents, meanings, and interpretations surrounding that character.

From this perspective,

Stephens’s (

2003) notion of early modern witchcraft as a “crisis of belief” acquires renewed significance when understood as both a theological and a psychological phenomenon. The witch was not merely a superstition projected onto women but a construct through which faith, doubt, and authority were continually negotiated. As Stephens explains, “without our recognition of this desire to believe, witchcraft appears to be a bundle of unrelated, even contradictory beliefs, held together by illogical, even irrational hatreds” (p. 366). The witch thus embodies the paradox of faith itself: born from the same impulse that sought to eradicate her—the need for certainty in the face of scepticism. This desire for proof also found expression in theology, where, as Stephens notes, “witchcraft theory and Protestantism emerged as manifestations of the same crisis of confidence in the efficacy of the sacraments” (p. 185). Both reflected the anxiety that the sacred might no longer be perceptible. While Protestant reformers questioned the tangible efficacy of a ritual, witchcraft theorists sought to defend it, insisting that the effects of maleficium were as real and material as those of sacramental grace. In this sense, the witch became the final refuge of belief in a world where faith demanded proof—an imaginary born from doubt yet sustained by the need to overcome it.

Archetypes do not incarnate in reality in an effective or total manner; they are merely models. The archetypes of control, painstakingly elaborated by Western culture since the Middle Ages—typifications or profiles such as those of the thief, the traitor, the perverse, the saint, the witch, or the murderer—did not find, despite the efforts of judges and legislators, any perfect fit between model and reality. … Archetypes are precisely that: archetypes, imaginaries, “ideals”. In reality, people are simply people, and their deviations from order, from the statu quo, are never as twisted as imagination and “service to the republic” would portray them.

Building upon this theological and cultural inheritance, the echoes of these constructions persist across visual and material culture, revealing the same unresolved tension between doubt and devotion, as well as corporeality and transcendence. As women become increasingly visible and influential in spaces traditionally dominated by men, their representations in art, fashion, and cinema respond accordingly. The new social order enables credible depictions of intellectual and strong women who demonstrate not only the potential of the female gender but also their capacity to accomplish everything men can do, thereby deconstructing the canons imposed by the monstrous-feminine imaginary. Moreover, contemporary representations of witches tend to converge more with the elegance of Audrey Hepburn than with the fatality and seduction of Mata Hari.

Echoing the ideas of

Beteta Martín (

2014, p. 296), the visual language once used to condemn women now becomes the terrain of their emancipation. The witches, Amazons, sirens, and other figures of the “monstrous-feminine” rise from the margins they once inhabited, reclaiming the symbols of fear, sin and desire as emblems of knowledge and power. In their reimagined forms, they no longer haunt culture—they shape it.

This transformation, from persecution to empowerment, marks not an end but a threshold. It opens the way for a broader exploration of how the witch—and the feminine archetypes that surround her—continue to evolve within contemporary visual and material culture, a trajectory that will be further developed in the next stage of this research.