Abstract

This article explores the pictorial representation of the Buddhist hell in Kamakura (1185–1333) Japan, with a focus on a mid-thirteenth century rokudō-e, or Pictures of the Six Realms, preserved at Shōjuraigōji Temple. The examination revolves around how these scroll paintings convey messages of salvation by representing the symbolic architecture of the hell realm, the lowest level within the six realms. By scrutinizing the visual representation of hell landscapes in four hell scrolls in the Shōjuraigōji set, the study unveils the architectural symbolism of boundaries and pathways. A visual analysis of two hell-tearing narrative scrolls further reveals that the key iconography involves the destruction of the architectural symbols of hell. Through tracing the concurrent processes of constructing and destroying the imaginary space of hell, the study demonstrates that the conceptual and visual construction of hell is coupled with an equally pronounced intent for hell-tearing. Lastly, based on the visuality of the hell-escaping narratives, the medium of hanging scrolls, and the centrality of an Enma scroll within the Shōjuraigōji set, the author proposes a spatial arrangement of this set of fifteen scrolls that could systematically convey the visual massage of “escaping from suffering in the six courses”.

1. Introduction

Hell (jigoku 地獄), the lowest level in the six realms, has been a recurring theme in visual art across Buddhist Asia since the final centuries of the first millennium (Moretti 2019; Yian 2015). Yet few have reached the degree of comprehensiveness as the hell imagery in Kamakura-period (1185–1333) Japan. The comprehensiveness is exemplified by a mid-thirteenth century set of fifteen hanging scrolls preserved at Shōjuraigōji Temple 聖衆来迎寺, Shiga Prefecture, Japan. Known as rokudō-e 六道絵, or Pictures of the Six Realms, this scroll set comprises four hell scrolls (Figure 1), two hell-tearing narrative scrolls, and a scroll featuring the judge of hell, along with eight scrolls depicting the other five realms within the Buddhist cosmology.

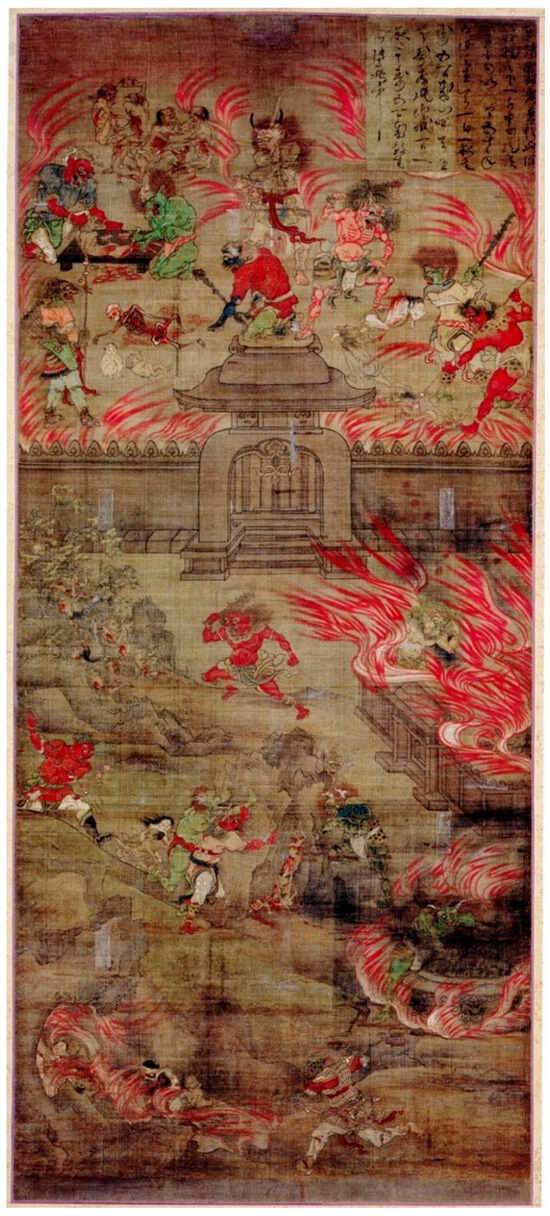

Figure 1.

The Hell of Endless Rebirth (Tōkatsu jigoku 等活地獄). Shōjuraigōji Six Realms Scrolls. Mid-thirteenth century. 155.5 cm × 68 cm. Hanging scroll; ink and colors on silk. Shōjuraigōji, Shiga Prefecture. Photograph courtesy of Shōjuraigōji Temple.

Scholarly discussions of the Shōjuraigōji scrolls have highlighted their extraordinary representation of spaces and landscapes, particularly those found in the empirical world. In recent decades, art historians have directed considerable attention to the representational techniques and meticulous depictions of landscape in the human realm. For instance, Tekeo Izumi highlights the successful representation of spatial depth in the Shōjuraigōji scrolls, drawing comparison with contemporaneous Chinese narrative and landscape paintings (Izumi et al. 2007). Miriam Chusid (2016) observes how the rich elements in the four scrolls of the human realm are derived from various pictorial sources and life experiences. Fusae Kanda (2005) delves into how landscape becomes the predominant visual feature in the Scroll of Human Impurity. Chelsea Foxwell (2016) demonstrates how the landscape and spatial representation in the human scrolls contribute to the visibility of karma. The current study, however, diverges from these discussions to explore the simultaneous construction and destruction of the imaginary space of hell and how the visual representation conveys the message of salvation.

The concept of escaping hell has been discussed extensively by scholars of Japanese Buddhist art (Hirasawa 2008, 2012), yet how the idea of escape is embedded in the process of constructing confinement has not been seriously considered. The conceptual and visual construction of hell, as I will argue, is accompanied by an equally strong intention of “hell tearing” (hajigoku 破地獄). Similarly, the visual messages of “escape from suffering in the six realms” (rokudō-bakku 六道抜苦) have been incorporated into the representation of the six-realms taxonomy.

Centering on the hell imagery in the Shōjuraigōji scrolls, this study unravels this multi-layered representational space in the literary, pictorial, and spatial contexts. The second section explores the duality in hell construction in the major literature source for the Shōjuraigōji scrolls. The third section examines the construct of hell space in the hell scrolls of the Shōjuraigōji set in comparison to earlier examples, emphasizing spatial prototypes and exotic architectural styles as important visual vocabularies of the hells. In the fourth section, the focus shifts to how these vocabularies serve as bases for narratives, symbols, and spatial representations of hell-tearing imageries. The fifth section proposes a spatial arrangement of the fifteen scrolls, which in return facilitates the contemplation of hell and that of hell-tearing simultaneously.

2. Constructing and Escaping the Hell within the Literary Source

A widely accepted cosmology among medieval Japanese Buddhists was articulated by the Tendai monk Genshin 源信 (942–1017) in his work, the Essentials of Rebirth in the Pure Land (Ōjōyōshū 往生要集, 985, hereafter the Essentials). Genshin outlines the cosmology in the first chapter, titled “Loathing the Defiled Realm” (onri edo 厭離穢土), identifying the six realms (rokudō 六道). These realms, in ascending order, include hell (jigoku 地獄), the realm of hungry ghosts (gaki-dō 餓鬼道), the realm of animals (chikushō-dō 畜生道), the realm of asuras (ashura-dō 阿修羅道), the realm of humans (hito-dō 人道), and the realm of celestial beings (ten-dō 天道) (Ishida 1970; Takakusu and Kaigyoku 1924–1933, no. 2682, vol. 84: 33). In line with Indian and Chinese conceptions of hell as a place of fear and punishment for sinners, the Japanese, nonetheless, formulated their own distinctive interpretation of the dialectical relationship among the realms.

On one hand, hell, perceived as the lowest level in this Buddhist cosmos, embodies seclusion, enclosure, and torture. Hell is the only realm where humans retain their human form outside the realm of humans and coexist with demonic guardians. In hell, the human body becomes an inescapable site of torture. If the body is burnt or cut apart, it is reset to an intact state, only to endure a relentless cycle of punishment. Furthermore, hell is the only realm named after the spatial features as opposed to the accommodated beings, such as ghosts, animals, and humans. Hell is distinctly characterized by a clear structure of its spaces. This spatial structure is hierarchical and multi-layered. Hell consists of eight major zones, namely, “the eight great hells” (hachidayi-jigoku 八大地獄). Each major zone is surrounded by sixteen auxiliary zones called “minor hells” (besshyo-jigoku 别処地獄) (Takakusu and Kaigyoku 1924–1933, no. 2682, vol. 84: pp. 33, a15–37, a12). All the above features suggest that hell is constructed based on situatedness rather than inhabitants.

On the other hand, hell engages in constant exchanges with other realms as much as the six realms are physically separated. This continuous interaction is attributed to the unceasing transmigration of sentient beings who enter and exit hell. Everything in this Buddhist cosmos, including the torture in hell, is seen as a consequence rather than gratuitous, reflecting the virtuous and evil deeds of the recipient in the past. Additionally, certain supernatural beings, such as Jizo 地藏 (Skt: Kṣitigarbha) Bodhisattva and his incarnations, possess the ability to trespass and observe hell without being subjected to the torture inflicted there. In this sense, hell is not fundamentally different from other structures; walls are constructed, yet doors are opened upon them.

From the Pure Land perspective, Genshin constructs a cosmological “map” that serves as a foundation for outlining the salvific path in later chapters. As he concludes, a genuinely peaceful state of mind cannot be obtained as long as one is attached to existence within the six realms. Therefore, by adopting a worldview that encompasses the six realms, one is led to realize the urgency of nenbutsu 念仏 practice, or reciting the Buddhas’ names. Through this practice, one can break free from the cycle of transmigration within the six realms and attain a non-revolving life in the Western Pure Land (Rhodes 2007, pp. 254–55).

Although no sentient being is exempt from the possibility of falling into hell, various theories of salvation have emerged to address the anxiety about reincarnation in the six realms, particularly hell. The rest of this article will reveal the internal tensions between escape and confinement as manifested in various spatial representations. To understand these tensions, it is necessary to begin with the discussion of how the strong boundary of hell is constructed.

3. Hell Imagery: Representing Confinement and Torture in Pictorial Traditions

3.1. Precedents: Incompletely Defined Hell Space in the Scrolls of Hells

Hell has long been depicted in Buddhist visual art not just for the purpose of inspiring fear but, more importantly, as part of a broader initiative to reveal the endless, karma-driven transmigration within the six realms. The earliest Japanese handscrolls of hell depiction, which can be dated to the twelfth to the thirteenth centuries, are the Scrolls of Hells (jigoku zōshi地獄草紙) (Ienaga 1960). The Scrolls of Hells exist in a fragmentary status and are not necessarily based on the Essentials but rather on other older sutras (Komatsu 1987, p. 67).1 It is generally accepted that the Scrolls of Hells have been commissioned as integral components of rokudō-e since the Heian period (794–1185), although only the Scrolls of Hells, the Scrolls of Hungry Ghosts, and the Scrolls of Illness have survived (Fukui 1998).2 The creation of rokudō-e, with its templates evolving around the thirteenth century, reflects a systematic conception of the six realms.

As previously mentioned, the spatial structure of hell features seclusion and enclosure. In its early development, hell imagery emphasized hell’s secluded location and man-made fortifications. The Scrolls of Hells usually consist of scenes of humans being tortured by beasts or demonic wardens. The typical settings of such scenes are a dark sky and a deserted landscape. In addition, imagery of solid walls and closed gates began to emerge, though still being scarce. For example, the Hell of Chicken (kei jigoku雞地獄) in the Harake scroll depicts a scene in which a huge rooster is spitting fire at sinners (Komatsu 1981–1985). The black background intensifies a viewer’s fear of being situated in an unknown darkness (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Hell of Chicken (kei jigoku雞地獄) from the Scroll of Hells, Harake version, twelfth century. In the collection of the Nara National Museum. Photograph courtesy of the Nara National Museum.

The Hell of Boiling Feces (Hutsushi jigoku 沸屎地獄), a scene depicted in the late-twelfth-century Matsuda scroll, similarly sets the stage in a deserted flatland without any rocks, vegetation, or hills and under a gray sky. The scene even represents the boundary of the hell as a charcoal-black wall extending over the horizon (Figure 3). Within a text–image–text–image composition, the scene of the Hell of Boiling Feces takes a landscape format. According to the inscription accompanying the scene, this hell features a flow of boiling feces in the east–west direction, toward which six hundred monks are driven out from the north gate of the walled zone (Komatsu 1987, p. 71).3 In the image, the river and the city wall parallel each other, occupying opposite corners of the picture in a diagonal composition. The atmosphere of hell is suggested by three visual components—the dark horizon, the black walled city along with its north gate, and a section of the river of boiling feces. The monotonous darkness indicates the hell’s underground locality, as no sunlight could penetrate its thick boundary. The walled area is so enormous that the wall extends to the horizon and one can barely determine where it ends.

Figure 3.

The Hell of Boiling Feces (Hutsushi jigoku 沸屎地獄) from the Scroll of Hells, Masuda-ke kō version, twelfth century. In the collection of the Nara National Museum. Photograph courtesy of the Nara National Museum.

The representation of man-made fortification further addresses the basic spatial structure of the hell. According to the Essentials, a great hell is a quadrilateral prison bounded within solid walls that cannot be penetrated. Each of its four walls is centered by a gate, outside of which are located the sixteen minor hells. This hell image provides a relatively clear representation of a zone in hell. More linear than the horizon and the riverbank, the wall divides the hell space into two: one black and unknown, and the other bare and scary. An edge of the north gate, depicted at the right end of the wall and backgrounded by the pale, naked bodies of the monastic sinners, appears straight and sharp. The gate is not articulated by any architectonic details typical of gate architecture; instead, it appears to be a mere opening on the wall. Only upon close examination can one discern a few vertical lines on the charcoal-black wall, suggesting the subtle structure of the gate. If the wall indicates where the sinners come from, then the flow on its opposite side shows where they are going. Though minimal, all the visual elements emphasize the firmly walled structure—a necessary spatial device in hell.

The Scrolls of Hells as such illustrate two principles of hell construction. The first principle is to trap sinners in an enclosed space, often signified by a dark sky, a fortified city, and thick mist. The second principle involves torturing the sinners through gruesome wardens and an extreme environment, represented by fire flames, a river of boiling feces, iron liquid, and a forest of blades.

Nonetheless, certain aspects of the hell construction are yet to be clarified. The image of the Hell of Boiling Feces struggles to resolve the paradox of depicting an “unlimited yet enclosed space”. Only being able to render a small portion of the hell, it remains unclear whether the scene is inside or outside the walled city. If it represents the inside, then the two rivers must intersect with the wall no matter how long it is, and the group of sinners are rushing from a mystical outside. If it represents the outside, then the city of the hell becomes a depository or jail of sinners, but the actual punishment happens outside, making the center of the hell less intimidating. The ambiguity found in the Scrolls of Hells is not present in the rokudō-e scrolls, as the spatial conception of hell gradually developed.

3.2. The Shōjuraigōji Scrolls: Prominent Representation of Gates and Walls

Similar to the Scrolls of Hells, the Shōjuraigōji scrolls represent hell in a highly selective manner concerning the localities, places, activities. However, the Shōjuraigōji scrolls feature a more pronounced representation of the hells’ man-made fortification and architecture. The Shōjuraigōji scrolls follow the tradition reflected by contemporaneous scrolls representing hell and other realms, and they epitomize a comprehensive way of illustrating the hell space. The innovations in image-making serve not only to reveal the great and minor hells simultaneously but also to display their exotic locality.

Firstly, the Essentials, the major text that the scrolls are based on, describes the eight great hells, but the Shōjuraigōji scrolls represent only half of them. Four scrolls, respectively, depict the first, second, third, and final levels of the eight great hells. They are, respectively, the Hell of Endless Rebirth (Tōkatsu jigoku 等活地獄, Figure 1), the Hell of Black Rope (Kokujō jigoku 黒縄地獄, Figure 4), the Hell of Crushing (Shugō jigoku 衆合地獄, Figure 5), and the Hell of No Interval (Abi jigoku阿鼻地獄, Figure 6). The fourth through seventh great hells are not included in the Shōjuraigōji set, despite the fact that they were often included in contemporaneous scrolls representing the hells described in the Essentials.4 The selection of hell in the Shōjuraigōji set is probably based on the three evils and the five great sins in Buddhist teachings. According to descriptions of the sinners and punishments in various hells in the inscriptions and the Essentials, the first, second, and third great hells, respectively, punish the three evils of killing, stealing, and sexual misconduct, while the final great hell punishes the five great sins related to harming the Buddha and Sangha.

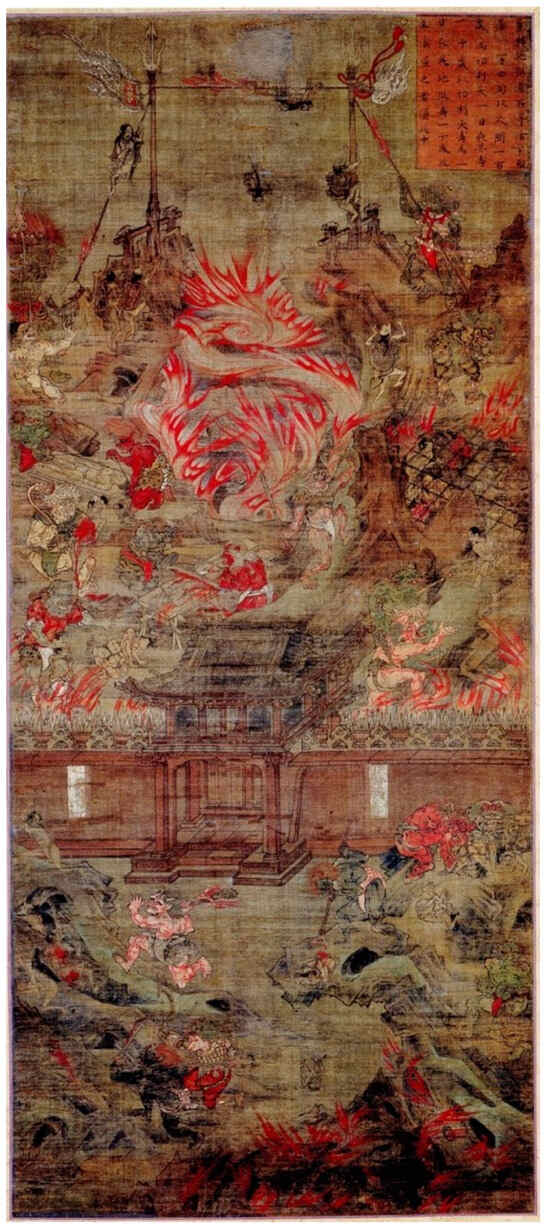

Figure 4.

The Hell of Black Rope (Kokujō jigoku 黒縄地獄). Shōjuraigōji Six Realms Scrolls. Mid-thirteenth century. 155.5 cm × 68 cm. Hanging scroll; ink and colors on silk. Shōjuraigōji, Shiga Prefecture. Photograph courtesy of Shōjuraigōji Temple.

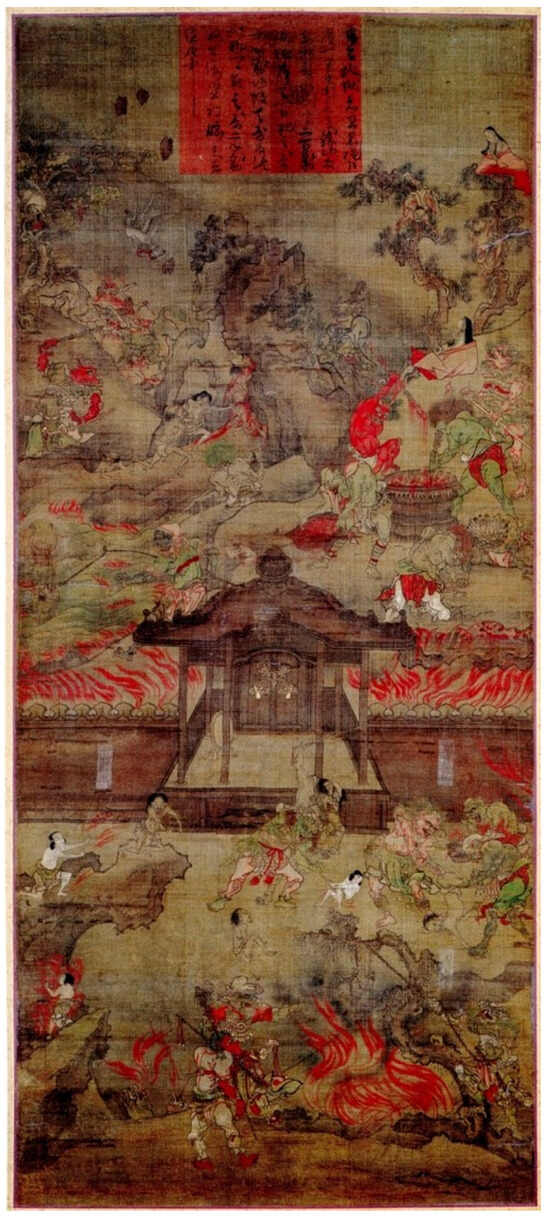

Figure 5.

The Hell of Crushing (Shugō jigoku 衆合地獄). Shōjuraigōji Six Realms Scrolls. Mid-thirteenth century. 155.5 cm × 68 cm. Hanging scroll; ink and colors on silk. Shōjuraigōji, Shiga Prefecture. Photograph courtesy of Shōjuraigōji Temple.

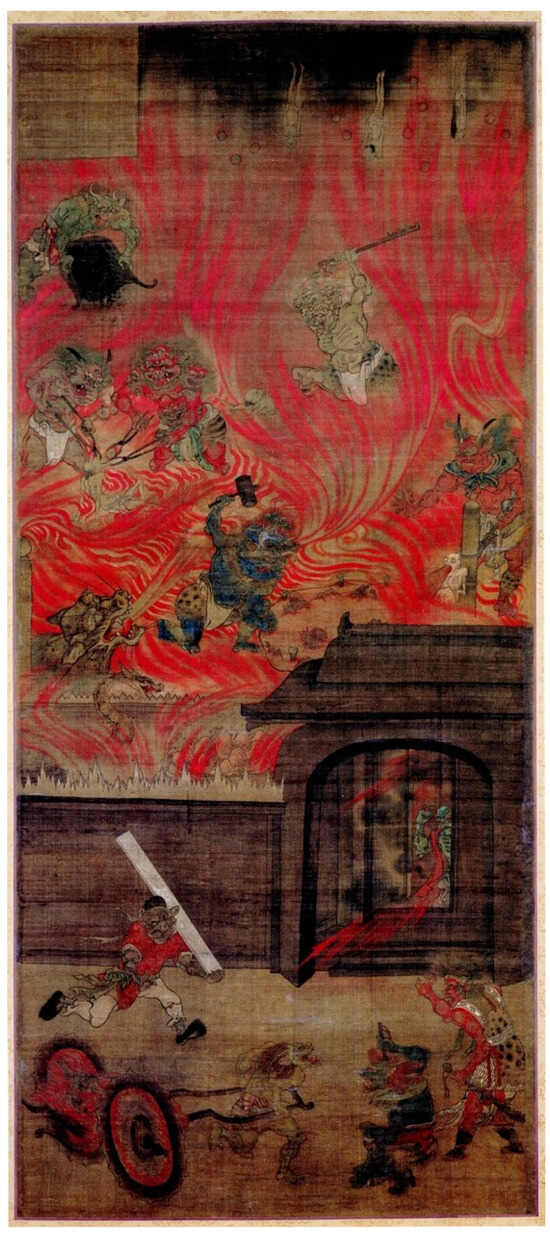

Figure 6.

The Hell of No Interval (Abi jigoku 阿鼻地獄). Shōjuraigōji Six Realms Scrolls. Mid-thirteenth century. 155.5 cm × 68 cm. Hanging scroll; ink and colors on silk. Shōjuraigōji, Shiga Prefecture. Photograph courtesy of Shōjuraigōji Temple.

Secondly, the selected hells are represented as torturing scenes either in front of or behind a fortress architecture. While the Essentials does not emphasize the center-versus-periphery relationship, the pictorial compositions in the Shōjuraigōji scrolls suggest a dichotomy between inside and outside.

Thirdly, although a variety of tortures are depicted, the ways they interact with the landform and architectural space could be summarized by a couple of types. Regardless of whether they occur inside or outside of a walled city, the major types of torturing scenes involve sinners falling into a valley or being crushed by rocks.

Fourthly, even so, the fortification is represented in the predominant location with a much greater extent of architectonic details than what could be found in the Scrolls of Hells. A gate occupies the middle section of each scene, and the wall on which it is opened upon creates a pronounced boundary between the inside and the outside.

The representation of gates and walls is curious because architecture is only briefly mentioned in the Essentials, and no other realms have such elements in their iconography. Despite its visual predominance, the architectural images in the Shōjuraigōji scrolls have been scarcely studied from the perspective of its iconography in hell representation. Although scholars have discussed representational techniques, like the illusion of visual depth and precedents from Chinese paintings, it remains unclear whether these gates hold crucial significance for hell.

3.3. “The Boiling Cauldron” at the Landscape and Architectural Scales

To understand the symbolic meaning of the architecturally defined landscapes, I investigated the development of two spatial prototypes in hell imagery, namely, the boiling cauldron and the sealed cage. The former embodies one of the major functions of hell—torturing the sinners—while the latter embodies the other function of imprisoning them.

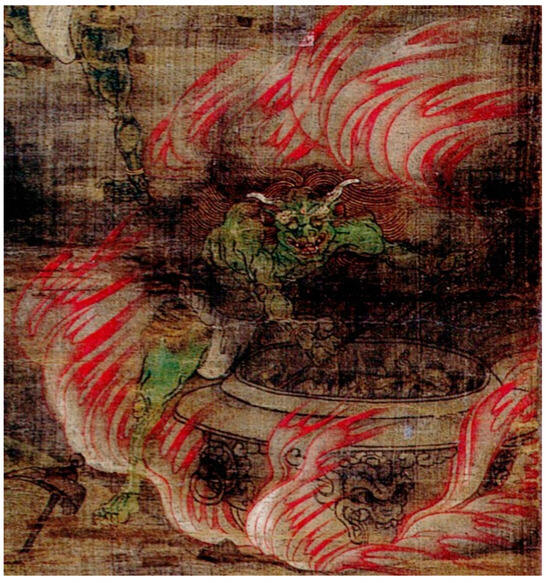

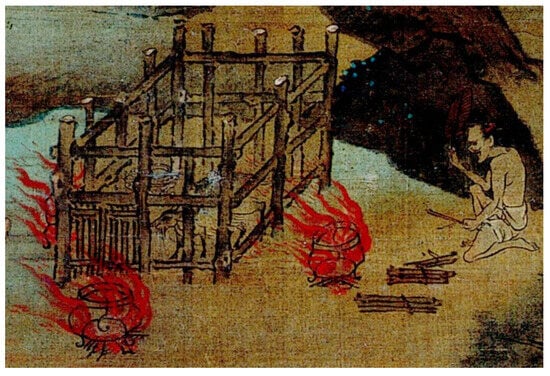

The prototypes are derived from empirical experience and integrated into the landscape and architecture to form a gruesome hell space. For instance, the Hell of Endless Rebirth scroll includes a scene of “the place of boiling cauldron”. This scene depicts a hell warden stirring a boiling cauldron full of sinners with a long stick (Figure 7). This is probably based on vivid human experience of torturing animals, as exemplified in another scene of slaughtering and cooking animal meat in the Realm of Animals scroll (Figure 8). In the latter scene, the animals are trapped in a cubical cage, and in front of them is a butcher heating up three round cauldrons. If anything from the imaginary world might be based on a model in real life, as demonstrated in the extreme example of Yoshihide’s burning carriage painting, the animal-slaughtering scene might have evoked empathy for the most vulnerable and terrified beings (Lippit 1999, p. 44; Izumi et al. 2007, p. 376).

Figure 7.

A boiling cauldron, detail in Figure 1. Photograph courtesy of Shōjuraigōji Temple.

Figure 8.

A butcher about to kill animals in a cage and boil them, detail in the Scroll of the Realm of Animals (chikushō-dō畜生道), Shōjuraigōji Six Realms Scrolls. Mid-thirteenth century. 155.5 cm × 68 cm. Hanging scroll; ink and colors on silk. Shōjuraigōji, Shiga Prefecture. Photograph courtesy of Shōjuraigōji Temple.

The boiling cauldron is one of the most consistent elements in hell iconography. As a spatial prototype, it has long been associated with the gruesome landscape and architectural spaces. For example, the Hell of Black Rope scroll renders the landscape of this great hell as a gigantic boiling cauldron in terms of function and spatial structure (Figure 9). The terrain within the walls features two huge iron mountains that encircle a pond of boiling iron. At the mountain peaks, two poles are erected and an iron rope is tied between their upper ends. The sinners have to climb the iron mountains and walk on this rope as punishment. If they fail to keep their toes on the rope, they fall into the huge boiling-iron pond beneath. Thus, the mountains and the pond constitute a boiling cauldron at the landscape scale.

Figure 9.

Two iron mountains and a pond of boiling iron, detail in Figure 4. Photograph courtesy of Shōjuraigōji Temple.

Another cauldron-like space is a burning courtyard in the Hell of Endless Rebirth scroll (Figure 10). As a rare scene not mentioned in the Essentials, this unidentified place is depicted as a courtyard on fire, inside which sinners are speared by a demonic warden outside. The image of a burning courtyard recurs in the Hell of No Interval scroll, which represents the most awful zone in the hell (Figure 6). This great hell is similarly rendered as a prison on a huge fire spanning over half the height of the scroll. In addition, boiling cauldrons together with flame-spitting dragons are placed in-between the prison’s double layers of walls, making the fortress a hazardous container.5 By means of assimilating landscape and architecture to the boiling-cauldron prototype, a synthesis of prison and torture is achieved. Fearful punishment is not limited to the contents within the prison; the prison itself is turned into the instrument of torture.

Figure 10.

A house on fire, detail in Figure 1. Photograph courtesy of Shōjuraigōji Temple.

3.4. Exotic Gates of “the Sealed Cages”

The walled prison of hell may be interpreted as modeled after the sealed cage prototype, yet architecture possesses expressive potentials through its various styles. The gates not only provide entrances/exits to the hellish prisons but also represent the architectural aesthetics of such locales. Further exploration into the meticulous architectonic details of these images reveals that the Japanese conception of exotic architecture might have been an inspiration for the imaginary hell architecture. The gates in the hell scenes might have been derived from Indian or Chinese architectural models found in pictorial and architectural sources available to Japanese painters.

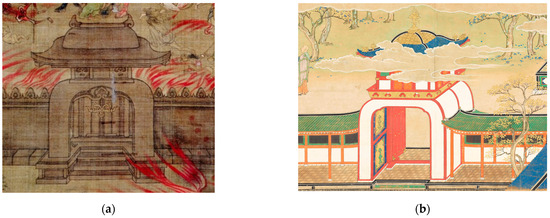

For example, the gates represented in the Hell of No Interval and the Hell of Endless Rebirth scrolls resemble masonry structures whose upper parts are tilted inward (Figure 11a). More characteristically, the pitched roof of this structure consists of a smaller, domed upper part and a larger, hat-like lower part. This architectural form alludes to gate architecture in Indian Buddhist monasteries, as seen in the seventh scroll of Genjō sanzōe 玄奘三蔵絵 (Illustrated Biography of Xuanzang, Figure 11b).

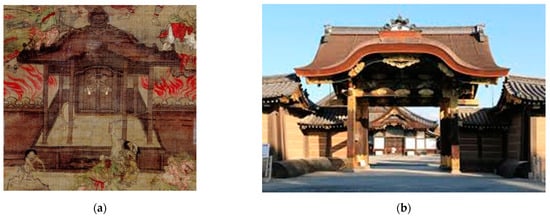

Figure 11.

Comparison of (a) the gate of the Hell of Endless Rebirth and (b) a gate of an Indian monastery in the sixth scroll of Genjō sanzōe, attributed to Takashina Takakane 高階隆兼 (Japanese painter, active ca. 1309–30). Photograph courtesy of Shōjuraigōji Temple and Fujita Museum of Art.

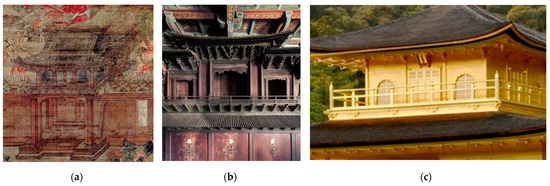

In another instance, the gate in the Hell of Black Rope scroll appears to be modeled after the Japanese version of Chinese Buddhist architecture. This gate is depicted as a timber-framed, two-story building with a hipped-and-gabled roof covered by ceramic tiles (Figure 12a). This type of roof is known as xialiangtou zao 廈兩頭造 or xieshan ding 歇山頂 in the Chinese contexts and had been applied to relatively high-rank buildings for several hundred years (Xiao 2017, pp. 94–95). The braces framing the entrance on the first level and the side windows on the second level feature a decorative arch form consisting of five minor arches. The application of this motif in medieval Chinese Buddhist buildings is testified by an eleventh-century sutra cabinet in Bhagavat Hall 薄伽教藏殿 of Huayan-si Monastery 華嚴寺 in Datong, Shanxi province, China (Figure 12b) (Liang 2001, pp. 67–86). The motif is also preserved in the top-level windows of the golden pavilion at Kinkaku-ji Temple 金閣寺 (Figure 12c), whose uppermost level was built in the style of a Chinese Zen Hall.

Figure 12.

Comparison of (a) the gate of the Hell of Black Rope, (b) sutra cabinet in Bhagavat Hall of Huayan-si Monastery, and (c) the golden pavilion at Kinkaku-ji. Photograph courtesy of Shōjuraigōji Temple. Images in the public domain.

Another architectural inspiration is a gate type known as karamon 唐門, or literally “the gate in the style of the Tang”. This style is exemplified by the main gate to Ninomaru Palace 二の丸御殿 at Nijō Castle 二条城, which is characterized by an undulating bargeboard above the entryway (Figure 13b). The gate in the Hell of Crushing scroll is depicted with a similar gable roof form, where the typical karahafu 唐破風 gable is applied (Figure 13a). The karamon gate image not just signals an entrance to the hell but also connects to the exotic and Chinese aesthetic associated with Buddhist architecture in medieval Japan.

Figure 13.

Comparison of (a) the gate of the Hell of Crushing and (b) the main gate to Ninomaru Palace 二の丸御殿 at Nijō Castle 二条城. Photograph courtesy of Shōjuraigōji Temple. Image in the public domain.

3.5. Section Summary

This section examined the representation of hell landscapes in the Shōjuraigōji scrolls as well as its precedents, with a focus on the development of boundary walls, gate architecture, and boiling cauldrons in depictions of hell. The early Masuda Scroll of Hells introduces both natural boundaries and man-made structures in hell, trapping sinners in prisons and subjecting them to torture. While this depiction is not explicit about the overall spatial structure or possible exits, it sets the foundation for the exploration of these themes. In comparison, the Shōjuraigōji scrolls emphasize the walls and gates as well as repetitively use the cauldron motifs. Furthermore, the gates of the great hells draw architectural inspiration from Japanese adaptations of Indian and Chinese Buddhist architecture, rendering hell as an exotic and untraceable place in the Buddhist world.

These treatments on architectural elements suggest a nuanced spatial representation, with attention given to the symbolism of boundaries and pathways. It could be inferred that, rather than diminishing, the potential for escaping hell increases alongside the reinforcement of hell’s boundaries. The following section will further explore the significance of gates in the context of sundering hell and the themes of escape and confinement.

4. Escape from the Hell through the Broken Cauldron and the Opened Gate

4.1. Freedom Unfolding: Mental Travel in the Kitano Scroll

The spatial representation of hell in hell-tearing or -escaping stories is closely associated with the representation of narrative structures. The journey through hell has been a recurring narrative theme in the literature since the Heian period, revealing an enduring desire for freedom from the samaric world. For example, the legend of Ono no Takamura 小野篁 (802–53), “How Ono no Takamura Saved the Minister Nishisanjo Out of Mercy” in Konjaku Monogatarishū 今昔物語集 (Anthology of Tales from the Past, 391–411), describes how shamanic figures like Ono no Takamura could traverse the six realms, a feat beyond the reach of commoners (Wakabayashi 2009).

In terms of narrative structures, travel-through-hell tales have often employed the witness’s perspective since the late Heian period. This is in contrast to the omniscient and descriptive approach used in the description of the six-realms taxonomy in the Essentials. The omniscient perspective provides an overview of the six-realms taxonomy while indicating ways to detach from it. On the other hand, the witness’s perspective establishes an individual viewpoint of traversing the various courses without being affected by them.

The integration of these two perspectives can be observed in an early-thirteenth-century handscroll set titled Kitano Tenjin Engi北野天神縁起 (Miraculous Origin of Kitano Tenjin Shrine, Figure 14). In these scrolls, the six realms are visually juxtaposed in a descriptive manner yet episodically connected by the monk Nichizō’s 日蔵 tour. The seventh handscroll of this set represents an early attempt to depict a systematic space of hell in a handscroll format. It introduces a distinct hell imagery compared to the Scrolls of Hells, owing to the representation of a journey. Moreover, the depiction of the six realms in the Kitano scroll is based on the Essentials, whereas the Scrolls of Hells are grounded in the Sutras of Buddhas’ Names.

Figure 14.

Kitano Tenjin Engi, Kitano Tenmangū, beginning section of the seventh handscroll, Kamakura period, 1219. (a) an entrance to the hell, (b) torment in the hell. (Komatsu 1978, pp. 32–33).

The Kitano scroll exemplifies four features the Shōjuraigōji scrolls adhere to. First, the demonic wardens take over the primary role of torturing sinners, reducing the role of dreadful animals and indicating a tendency toward bureaucratism in hell’s operation. Second, the eight great hells are condensed and represented by images of the burning gate and the boiling cauldron. Third, and more importantly, it portrays individuals who are exempt from the torture by depicting them hovering in midair above the horrifying landscape. In his soul travel, the eminent monk remains unaffected by the sufferings in hell, as every punishment occurs on solid ground while he floats in midair. This exception reveals a deliberate limitation of the hell space in visual representation: although hell is boundlessly broad, the effective part is confined to the ground surface. Fourth, in the Kitano scroll, the freedom of mental travel could be experienced by the viewer through sight movements along the painting surface. Unfolding the handscroll part by part, a viewer follows Nichizō’s path through the six realms, thereby achieving a sense of mobility and freedom.

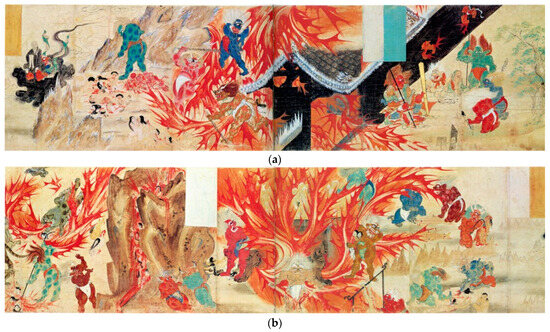

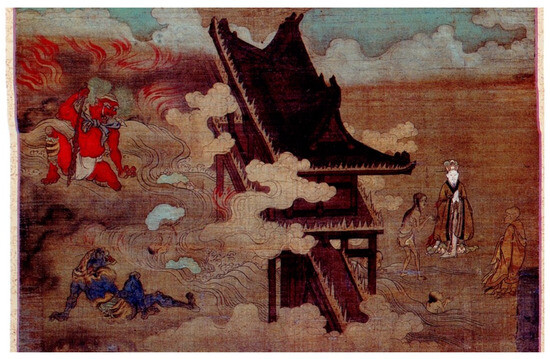

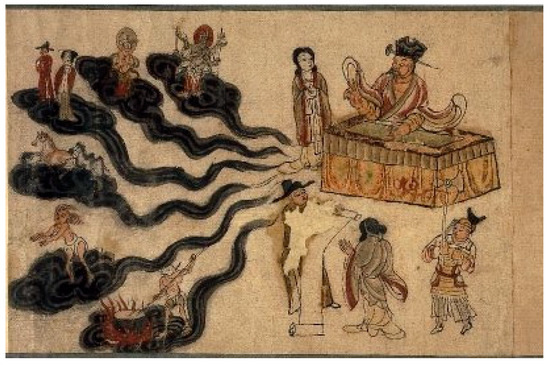

4.2. Two Episodes of Hell-Escaping in the Shōjuraigōji Scrolls

Two narrative scrolls in the Shōjuraigōji scrolls depict how practitioners of nenbutsu manage to escape and aid others in breaking free from hell. Both scrolls systematically portray the space of hell within the six realms but illustrate an escape route by challenging its symbolic boundaries. The Scroll of the Karmic Merit of Nenbutsu Recitation as Explained in the Sutra of Precepts for Laymen represents this act as breaking free from the boiling cauldron (Figure 15). The Scroll of the Karmic Merit of Nenbutsu Recitation as Explained in the Sutra of Parables represents the act of hell breaking as an exit through the gate architecture (Figure 16). The hell scenes utilize broken cauldrons to symbolize the sundered hell and gate openings to signify the movements of entering and exiting. Throughout the viewing of these hanging scrolls, the beholder is taken on a simulated journey, passing through various realms including hell without succumbing to their influence.

Figure 15.

Scroll of the Karmic Merit of Nenbutsu Recitation as Explained in the Sutra of Precepts for Laymen. Shōjuraigōji Six Realms Scrolls. Mid-thirteenth century. 155.5 cm × 68 cm. Hanging scroll; ink and colors on silk. Shōjuraigōji, Shiga Prefecture. Photograph courtesy of Shōjuraigōji Temple.

Figure 16.

Scroll of the Karmic Merit of Nenbutsu Recitation as Explained in the Sutra of Parables. Shōjuraigōji Six Realms Scrolls. Mid-thirteenth century. 155.5 cm × 68 cm. Hanging scroll; ink and colors on silk. Shōjuraigōji, Shiga Prefecture. Photograph courtesy of Shōjuraigōji Temple.

4.2.1. The Sutra of Precepts Scroll: Lotus-Birth from a Broken Cauldron

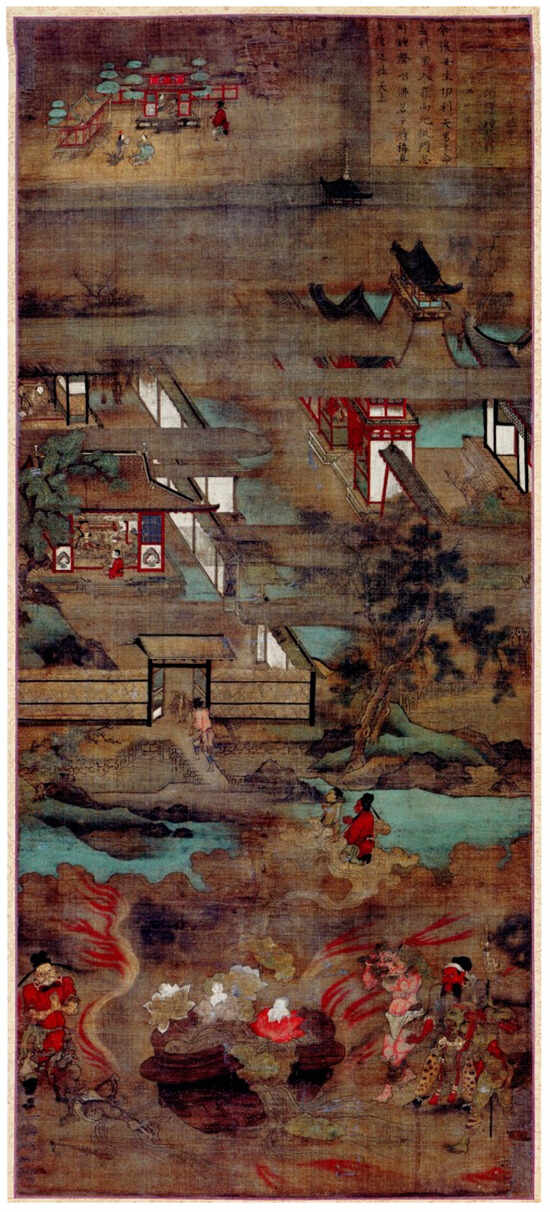

An allegorical representation of hell-tearing in the Sutra of Precepts scroll is the broken cauldron. The scroll represents, in a descending manner, the realm of heavenly beings, the human realm, and hell. The narrative unfolds with the story of a woman saving her husband by teaching him the practice of nenbutsu. In the narrative painting, a man named Kori, who indulged in excessive drinking and gluttony, fortunately heeded the advice of his wife and recited Buddhas’ names. When Kori was sent to hell upon death, he remembered to recite Buddhas’ names and thereby sparing himself from hell. Subsequently, he ascended to the realm of heavenly beings, where his wife had previously been reborn. This pivotal moment is symbolized by the breaking of the cauldron of hell, allowing the sinners who had been tortured therein to attain rebirth on lotus flowers (Figure 17) (Izumi et al. 2007, pp. 140–41).

Figure 17.

Breaking the boiling cauldron, detail in Figure 15. Photograph courtesy of Shōjuraigōji Temple.

A defeated hell, whether represented as a walled city or a cauldron, is usually inundated by flows adorned with lotuses. The Sutra of Precepts scroll predominantly depicts lotus flowers growing from the broken cauldron. In another instance, the Sutra of Parable scroll depicts lotus leaves among the waves. It not just indicates a tender environment that lotus is associated with, but also carries a strong connotation of lotus-birth into the Pure Land. Once broken, the visual sign of hell conveys an even stronger message of transformation and salvation.

4.2.2. The Sutra of Parables Scroll: The Hell’s Gate as a Metonym

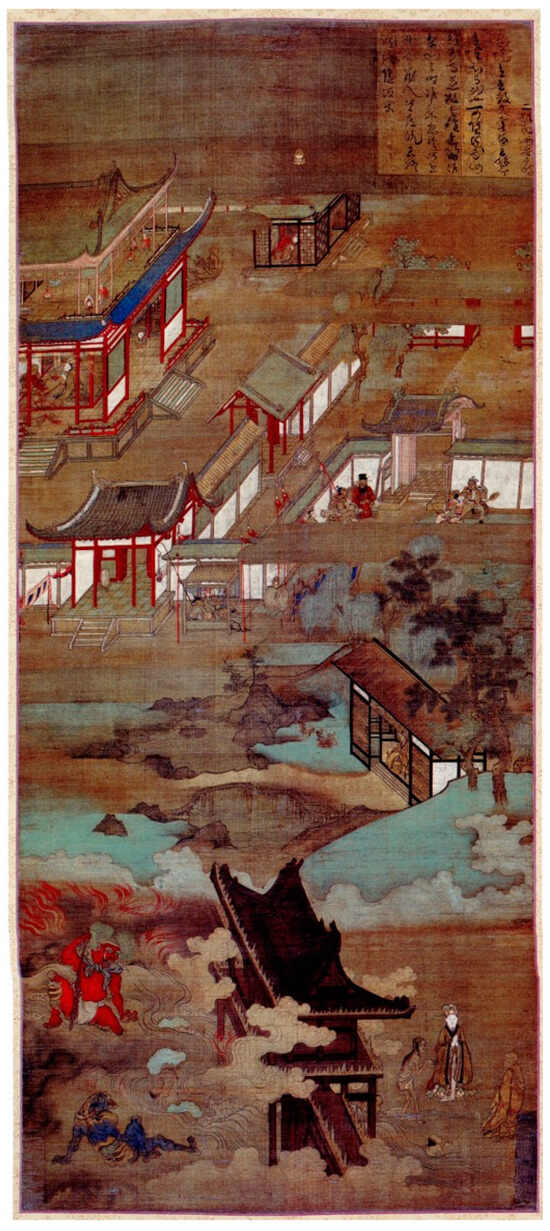

The Scroll of Sutra of Parables depicts the tale of an anonymous monk who, through nenbutsu practice, saved his mother from hell and converted an evil king of a remote kingdom destined for damnation. The narrative unfolds as the monk, in search of the whereabouts of his late mother, has a vison where five of the six realms manifested in front of him.6 He then manifests himself in the king’s bedchamber, appearing with only his upper body, and imparts counsel despite the king’s repeated attempts to sever his head. Converted by the monk, the king turns to constant prayer at a Buddha hall to avoid the impending descent into hell. The monk’s mother, too, is rescued from hell. This crucial plot is represented by her emergence from the gate of hell, standing before the monk and the king (Figure 18) (Izumi et al. 2007, pp. 130–31).

Figure 18.

Exiting the gate architecture, detail in Figure 17. Photograph courtesy of Shōjuraigōji Temple.

The scroll adopts a tripartite composition. It situates the palatial complex of the remote kingdom in the upper part, the hermitage of the monk in the middle, and hell—represented by a gate and two demonic wardens—in the lower register. The two settings within the human realm are visually connected by a bridge and a tilted misty ground. Hell is distinctly separated from the human world, marked by a horizontal border of a clear-edged cloud or vapor.

In order to convey the message of salvation, the solidity of hell is challenged through spatial and perspectival constructions. In this condensed scene, the hell space is divided by the gate architecture, aligning with the hell scrolls. While the gate itself does not identify the inside and outside, the left side of the gate, representing two demonic wardens torturing a sinner in a boiling flow, is likely a main hell within the walled city. The right side of the gate, showing the protagonist and the two individuals he managed to rescue, probably represents the place outside of the main hell. Salvation is conveyed by the imagery of leaving the walled city, suggesting that the gate architecture holds significance in representing the acts of entering and exiting hell. The image does not represent the entirety of hell but rather a corner of its central prison, but it is challenging to picture an alternative and tangible boundary for the realm. This scene of exiting through the hell’s gate illustrates a viable method of portraying the breaking of this enclosed yet limitless space, using the architecture of hell in a metonymical manner.

4.3. The Hanging Scroll Format: Representation of Vertically Layered Realms

The Shōjuraigōji scrolls are notably large, measuring 155.5 cm (height) by 68 cm (width), and they are in the hanging scroll format. This format allows for easy display on a wall or a stick, making it convenient for multiple viewers to examine simultaneously. The hanging scroll format, in contrast to the handscroll format, provides a vertical composition that is particularly effective in representing the vertical spatial structure of the six-realms taxonomy, enhancing the imagination and visualization of hell-tearing.

The six realms are conceptually arranged along a vertical axis, with hell situated beneath the human realm, which is, in turn, topped by the realm of celestial beings. The pictorial compositions of the two narrative scrolls align with this conceptual arrangement of space, where the upper register represents the better realm and the lower register represents the worse realm. In comparison to the handscroll, the hanging scroll offers a heightened sense of the hierarchy along the vertical axis.

Moreover, the hanging scroll format excels in representing spatial depth. While depicting a vertical structure, the hanging scroll portrays figures, architecture, and landscape in successive layers, creating a sequence of foreground, mid-ground, and background. In the two scrolls, the figures in hell are notably larger than those in the human realm. In addition to emphasizing the dramatic moment of hell-tearing, the foreground setting smoothly transitions to the mid-ground setting in the human realm due to the illusionary depth. This spatial illusionism also provides an unconventional perspective, allowing viewers to see the gate from inside out, as opposed to the typical outside–in view. As a result, the spatial representation evokes a sense of exiting hell in the viewer’s contemplation.

Sequentially, the viewing experience becomes integrated into the process of salvation or transition between the realms. If following the narrative, viewers first look at the middle section of the hanging scroll, which represents the human realm in content and a comfortable viewing zone for viewing due to its height approximating to the viewer’s eye level. As the viewers’ eyes trace down to the bottom of the hanging scroll, they witness along with the protagonists in the narratives the breaking of hell. When looking up to the top register, they observe the saved or converted individuals finding peace in the realm of heavenly beings or the Buddha hall. In a word, what the viewers’ eyes follow is the journey of the souls released from suffering places.

4.4. Section Summary

This section delves into the narratives, perspectives, symbols, and spatial representations of hell-tearing imageries, drawing comparisons between the Kitano handscrolls and the Shōjuraigōji hanging scrolls. The key iconography of hell-tearing in the Shōjuraigōji scrolls involves metonymically breaking the prison of hell, symbolized by the cauldron of hell, and metaphorically escaping the torture of hell, represented by the gate of hell. Additionally, the blooming lotus flowers emerge as a significant landscape element, serving as an omen of hell-escaping.

By highlighting the integration of omnificent and individual perspectives in both the literature and image-making, the analysis revealed the necessity of having a witness present in the hell-tearing scenario. This reflects the tendency that the viewing experience of the six-realms pictures becomes assimilated into the illusionistic spaces they represent. The next section will further discuss the possibility that the physical spatial arrangement of the six-realms pictures might have served the contemplation of the hells and hell-tearing.

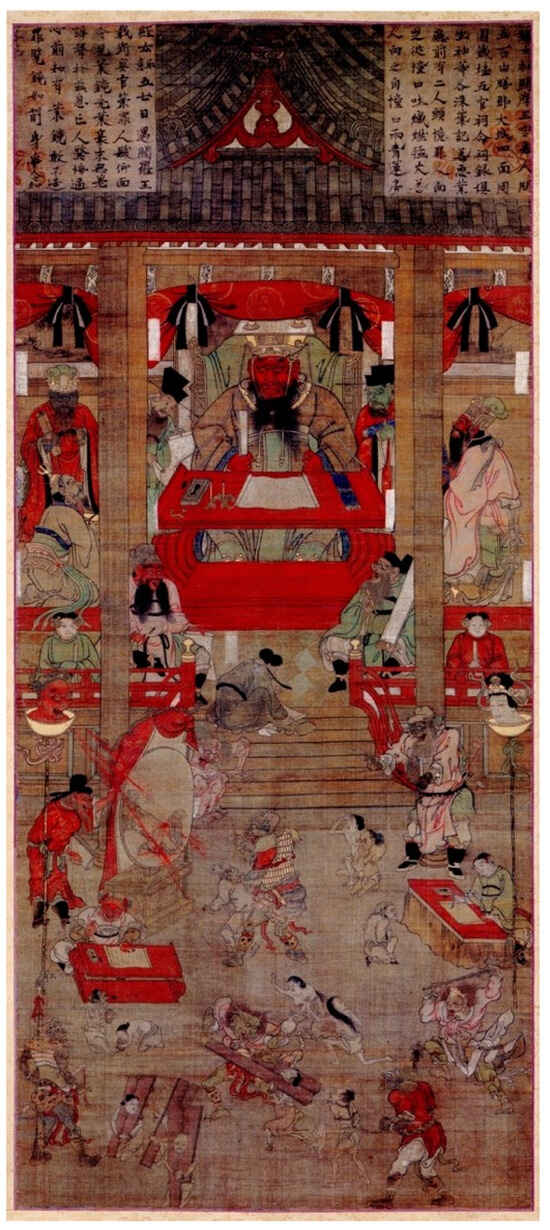

5. Ritual Space: Turning the Wheel of the Six Realms

The connectivity of the six realms is testified by its multi-directional entrance—the court of Enma. Often regarded as the entrance to hell, the court of Enma is indeed a terminal point of transmigration. This concept is evident both in literary accounts and visual representations as early as in the tenth century. For instance, Nihonkoku Genpō Zen’aku Ryōiki 日本国現報善悪霊異記 (Miraculous Stories from the Japanese Buddhist Tradition) narrates a story of Hiromushime, summoned to the palace of Yama, the king of death, and subsequently sent back to life with a half-human–half-ox body. This narrative illustrates Yama’s power to send individuals to destinations beyond hell (LaFleur 1986, pp. 35–37; Keikai 1973, pp. 392–97). A Dunhuang handscroll titled Jūō jigoku zu十王地獄図 (Pictures of the Hells of the Ten Kings) depicts one of the ten kings of hell sending the deceased to the six realms (Figure 19). Similarly, the Court of Enma scroll in the Shōjuraigōji set suggests diverse destinations based on the judgement of the deceased’s good and evil deeds (Figure 20).

Figure 19.

The Ten Kings Scroll, Dunhuang, 10th century, Five Dynasties, British Museum. Or.8210/S.3961. Photograph courtesy of British Museum.

Figure 20.

Court of King Enma (Enma-ō chō 閻魔王庁). Shōjuraigōji Six Realms Scrolls. Mid-thirteenth century. 155.5 cm × 68 cm. Hanging scroll; ink and colors on silk. Shōjuraigōji, Shiga Prefecture. Photograph courtesy of Shōjuraigōji Temple.

5.1. Question about Spatial Arrangements Reframed

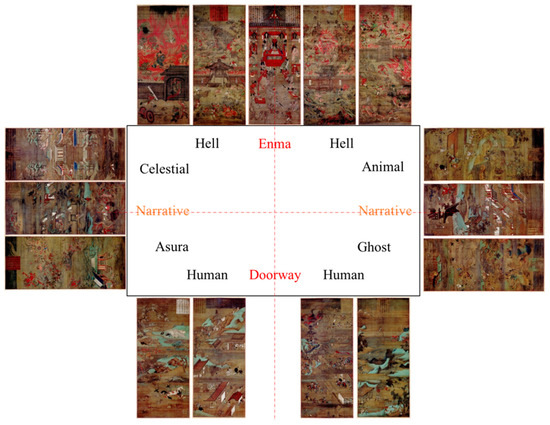

Scholars have explored the potential significance of the Enma scroll within the whole set, given that it offers a frontal view of a main icon and portrays the judgment and transmigration of the deceased into the six realms. Kasuya Makoto suggests that the Enma scroll serves as the focal point of the entire set, coordinating movements within all realms, but the order of other scrolls is not discussed (Izumi et al. 2007, pp. 226–27; Chusid 2016, p. 132). Yamamoto Satomi presents two scenarios: one proposes placing the Enma scroll between the two hell-tearing scrolls (Yamamoto 2012, pp. 15–16), while the other suggests positioning it first and to the right of the series of hell scrolls (Yamamoto 2011, pp. 117–20; Chusid 2016, p. 131). Each scenario has its limitations: the first proposal does not consider the order of other scrolls and the second one neglects the centrality of the Enma scroll. Indeed, the likely incomplete state of the scroll set does not allow one to reconstruct their original placements in an Enma hall, likely in Shuryōgon’in (Nara National Museum 1990, p. 159). Given the absence of historical records and similar cases, it is almost impossible to verify these hypotheses.

However, these proposals demonstrate a common belief among scholars: although the hanging scrolls could be flexibly arranged in various ways and displayed in different rooms, there must exist some more systematic ways of arranging them than others. In order to gain further insights into the overall meaning of the set of fifteen scrolls, it is still meaningful to consider what kind of spatial arrangement would effectively convey the soteriological message. After all, this question must have been considered by many who once had the opportunity of displaying the set of scrolls.

5.2. Centrality of the Enma Scroll

To begin with, it is important to verify the central position of the Enma scroll in the entire set. This thesis is reinforced by the intrinsic fact that the Enma scroll is distinct from the other fourteen scrolls in four aspects.

Firstly, the nature of this scroll distinguishes itself from the others. It is the only scroll that is not based on the Essentials but is adapted from the painting genre of Pictures of the Ten Kings.

Secondly, the Enma scroll provides an alternative type of escaping hell. Rather than traveling from the hell to other places, King Enma directly sends the deceased to the good paths as long as they conducted benevolent deeds in their previous lives. As depicted in the lower right side, a figure is judged by a tender-looking official and scrutinized by a non-wrathful deity’s head (Figure 21). The appearance of the judges indicates that the deceased is taken as a righteous person and presumably exempt from the evil paths.

Figure 21.

A deceased being judged by an official and a head, detail in Figure 20. Photograph courtesy of Shōjuraigōji Temple. Annotation by author.

Thirdly, this scroll features an architecturally defined space that is not so predominant in contemporaneous Pictures of the Ten Kings. It is not only represented in the unconventional frontal view, but also features the audience hall where King Enma is seated in a solemn space away from the busy judging scene. In this hall, Enma sits in front of a painted screen, which bears ink landscape painting in the Chinese style. Seven officials gather around King Enma and report to him. The outer court is where the actual judgement and decision take place, with sinners running here and there and guards shouting at them. Communication between the inner and outer courts is mainly indicated by a messenger kneeling on the staircase, holding a scroll in his hand, and facing the direction of King Enma. The architectural setting implies the structure of administrational access and spatial hierarchy. This spatial and behavioral division also suggests King Enma’s venerable status as an icon for worship.

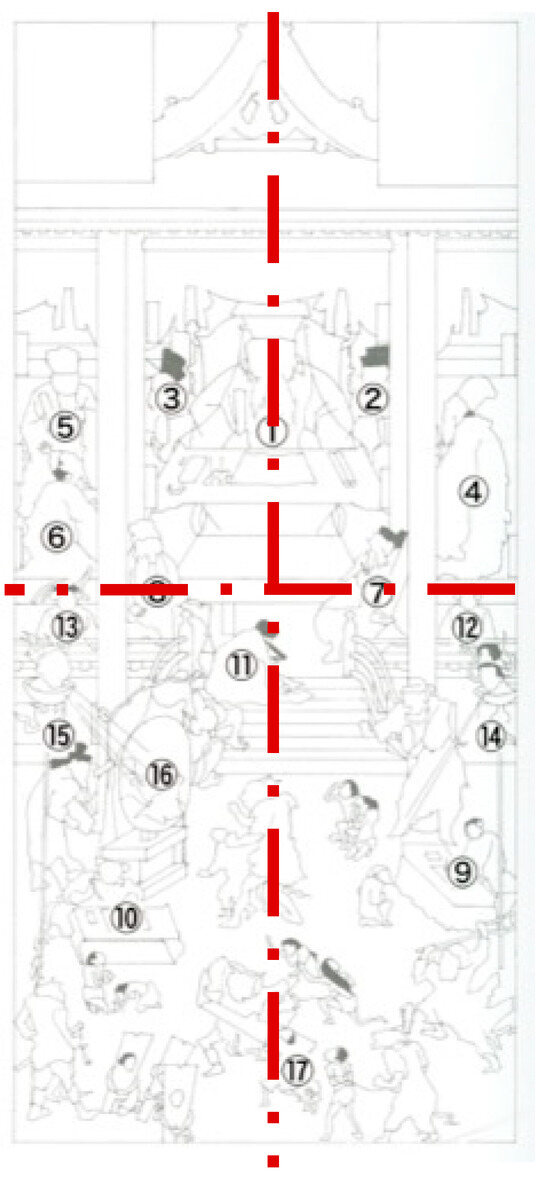

Fourthly, the Enma scroll is the only scroll with overall symmetry. Both the architectural stage—signaled by the gable roof and the stairway—and the predominant icon—King Enma—are presented in a frontal view, defining the central vertical axis of the painting. From the curtains and the screens behind Enma to the judging instruments and heads, everything in this setting appears in symmetrical pairs. They extend the central vertical axis from inside the hall of Enma to outside of it, indicating a penetrating view across the judging scene and directed at King Enma (Figure 22). The unique composition supports the thesis that this scroll was designed for the center of a ritual space, establishing a direct relationship between the viewer and the viewed icon.

Figure 22.

Two pictorial axes in Figure 20. Base diagram after (Izumi et al. 2007, p. 143), annotation by author.

5.3. A Potential Arrangement of the Scrolls in a Ritual Space

Based on the central position and the compositional axes of the Enma scroll, I further examined the internal logics of the Shōjuraigōji set. A noticeable fact is the unequaled numbers of scrolls for the six realms. In addition, a potential key to the spatial arrangement is the conceptual relationship among the twelve scrolls of the six realms and the three “special scrolls”—the Enma scroll and the two narrative scrolls. Considered factors also include the basic form of architectural space and the size of the scrolls. As typical for traditional Japanese architecture, the room, hall, or shrine for displaying the set of scrolls most likely has a rectangular plan so that the hanging scrolls could be displayed on the four walls. Using a set of hanging scrolls to adorn interior walls was a common practice in East Asia, and abundant literary and archaeological evidence has been identified on the continental side (Wu 2022, pp. 187–88). Given the large size of the Shōjuraigōji scrolls, five of them could easily occupy the entire width between two columns.

The examination leads to a potential arrangement of the set of fifteen scrolls in a ritual space, allowing the hanging scrolls to display the six-realms taxonomy and convey the salvation message. My proposal carefully considers the number of scrolls in subsets. There are four scrolls each for hell and the human realm, one each for the realms of hungry ghosts, animals, asuras, and celestial beings, two narrative scrolls depicting hell-tearing stories, and one for the court of Enma. The singular Enma scroll is most suitably paired with a doorway. Both serve as liminal spaces—the former for the afterlife and the latter for the living. The equal number of the human and hell scenes, four each, suggests a parallel placement on opposite walls, with the former likely associated with the entrance for humans and the latter with Enma and the afterlife. The pair of narrative paintings is fittingly hung on the gable walls, serving as central pictures for worship and contemplation, because they convey soteriological messages like the Enma scroll. Each of the hell-tearing scrolls is flanked by two scrolls of the other four realms.

An additional reason for the central locations of the three “special scrolls” is that the compositional axes of the Enma scroll would be better revealed if they are integrated into the axes of the ritual space. In my proposal, two axes form a spatial cross at the center of this room (Figure 23). The one spanning between the doorway and the Enma scroll is the main axis pointing to the major accesses in the present and afterlife. The other, spanning between the two narrative paintings on the gable walls, is the secondary axis pointing to the possible ways to break the physical boundaries between the realms. The two axes in architectural space resemble the pictorial axes in the Enma scroll. The main axis echoes the vertical axis in the Enma scroll and extends it into the ritual space, while the secondary axis parallels the horizontal axis, emphasizing the spatial division in this underworld gateway. The axes in the pictorial space offer a visual entrance/exit to the six-realms circle physically structured by the axes in the ritual space.

Figure 23.

An optimal layout of a ritual space for displaying the Shōjuraigōji scrolls. Diagram by author.

Moreover, the layout of the six-realms paintings might be more significant if it resembles the wheel of the six realms. Distributing the paintings around the room according to their ascending order in the Essentials could facilitate the contemplation of the taxonomy in a clockwise circumambulation program, which is a common ritual in Buddhist architecture. In fact, esoteric Buddhist mandalas of the six realms from the continent typically visualize the taxonomy in a circle (Figure 24).

Figure 24.

A rock carving of the wheel of the six realms, Dazu Rock Carving, Chongqing, China, 13th century. Image in the public domain.

If we opt for a clockwise circle for displaying hell, and the realm of animals, hungry ghosts, humans, asuras, and celestial beings, then we have some rationale for the placement of the two narrative scrolls.7 This proposal associates the Sutra of Parables scroll with the scrolls of hungry ghosts and animals, while linking the Sutra of Precepts scroll with the scrolls of asuras and celestial beings. This association is based on thematic content, with the Sutra of Precepts scroll exclusively representing the realm of celestial beings.

Further considering the visual composition within each scroll, this proposal organizes the hell scrolls in the following order: starting with the Hell of Endless Rebirth, followed by the Hell of Black Rope, then the Hell of Crushing, and concluding with the Hell of No Interval. This sequence aligns with both the ascending order of them according to the Essentials and the descending locations of the gate images in the scrolls.

For the scrolls of the human realm, this proposal suggests beginning with the Impurity scroll, followed by the two Sufferings scrolls, and ending with the Impermanence scroll. This arrangement follows the order in the Essentials and considers the approximate symmetry of their landscape backgrounds.

In summary, the proposed arrangement is, clockwise beginning from the left end of the rear wall, the Hell of Endless Rebirth scroll, the Hell of Black Rope scroll, the Enma scroll, the Hell of Black Rope scroll, and the Hell of Crushing scroll, and moving to the right wall, the Realm of Hungry Ghosts scroll, the Sutra of Parables scroll, and the Realm of Animals scroll, and moving to the front wall, the Impurity scroll, one Sufferings scroll, the doorway, the other Sufferings scroll, and the Impermanence scroll, and moving to the left wall, the Realm of Asuras scroll, the Sutra of Precepts scroll, and lastly, the Realm of Celestial Beings scroll (Figure 23). While taking into account the flexibility of displaying portable paintings, this proposal aims to create an extreme scenario where the maximum significance of the set of scrolls is explored.

5.4. Potential Ritual Functions of Hell Imagery and Rokudo-e

The proposed arrangement of the Shōjuraigōji scrolls outlines a ritual space designed with a deliberate intention to escape from the confinement in the six realms, particularly hell. William R. LaFleur, a modern scholar of Japanese religions, has proposed four types of response to the ever-transmigrating world, embodying the aspiration of rokudo-bakku, or “escape from suffering in the six courses”. These responses are infiltration, transcendence, copenetration, and ludization (LaFleur 1986, pp. 49–59).8 These responses prompt a reconsideration of the purposes of making images of hell and the six realms in medieval Japan.

Firstly, the imagery of hell set up a stage for showcasing Buddhist deities and deified judges in the afterlife world. For example, according to Enma-ō dō emei 焔魔堂絵銘 (Painting Descriptions of the Enma Hall) written in 1223 (Chusid 2016, pp. 218–24; Mika 2004, pp. 206–7), mural paintings of hell-related stories adorned the surrounding walls in an Enma hall at Daigoji Temple 醍醐寺, providing a backdrop for the statues of King Enma and his ancillary officials (LaFleur 1986, p. 226).9 The depictions of hell further facilitate Buddhist practices believed to be effective in alleviating sufferings. In another instance, in an early-eleventh-century Jissaidō Hall 十齋堂 at Hōjōji Temple 法成寺, Buddhist scriptures and precepts were recited in front of hell murals to ease the sufferings of those who had fallen into hell (Ōgushi 1954, pp. 44–45; Chusid 2016, p. 33). Similarly, Enma halls at Hōshakuji, Ennōji, and Shidoji were ritual sites for offering prayers for salvation (Chusid 2019, pp. 41–47). Hell imagery displayed in temple settings created an atmosphere necessary for staging Buddhist icons and performing rituals.

Secondly, images of hell and the six realms likely served as visual aids in Buddhist practice for the sake of rescuing beings from the evil paths and sending them to the Buddhaland. During the Kamakura period, the display of hell screens was commonly used for the recitation of Butsumyōkyō 仏名経 (the Sutra on the Names of the Buddhas) (Takahashi 2004; Chusid 2016, p. 20). Genshin actively promoted the nenbutsu practice, which aims at reaching the Western Pure Land.

The Shōjuraigōji scrolls seem to have been made and used with soteriological purposes as well. During Genshin’s instructional period in Ryōzen’in Cloister霊山院, where the Shōjuraigōji scrolls were first repaired in 1313, monthly practice of making offerings for sentient beings was conducted along with lectures on the Lotus Sutra. According to a fourteenth-century documentation titled Sanmon dōshaki 山門堂舎記 (Records of Temples and Shrines in Enryakuji Temple), these offerings were aimed to release those suffering in the three evil paths and promise their rebirths in the Pure Land (Izumi et al. 2007, pp. 179–81; Chusid 2016, p. 41).10 To carry on Genshin’s teachings, a fellowship group named “the Twenty-Five Samādhi Society” (Nijūgo Zanmai-e 廿五三昧会) possibly commissioned the Shōjuraigōji scrolls to facilitate postmortem care, nenbutsu practice, and transference-of-merit rites for those suffering in the six realms (Chusid 2016, p. 58).

The third kind of practice around the six-realms imageries was driven by a combination of mundane and supermundane goals. A practitioner could use the representational space of the six realms simultaneously for worldly benefits, such as a long and healthy life, and for postmortem welfare and rebirth in the Pure Land. For example, an Enma hall at the Anrakujuin 安楽寿院 temple complex commissioned by the retired sovereign Toba (鳥羽法皇, 1103–56) integrated both purposes. This hall provided a stage for Toba to petition King Enma for a long life, and for memorial and salvation rites to be enacted after his death (Yamamoto 2013, pp. 100–5; Chusid 2016, pp. 108–11).

Finally, carefully crafted visual and ritual programs can potentially enhance the understanding of the interconnectedness and playfulness inherent in the depiction of the six realms. In the proposed arrangement of the Shōjuraigōji scrolls, both the ritual space and the Enma scroll are centered by Enma and visualized as an entrance to the six realms, yet the former visualizes everything in the same two-dimensional painting medium. While the ritual space aims to simulate the imaginary gateway of the afterlife visualized by the Enma scroll, the former diminishes the terrifying dominance of King Enma by substituting the icon with a continuity of the pictorial surface and, consequently, a sense of mobility. Moreover, the ritual space increases diversity, color, and playfulness within a continuous and austere landscape setting, offering hope and avenues of escape from this dreadful locality.

5.5. Section Summary

In this section, I examined the spatial representation in the Enma scroll and proposed an arrangement for the Shōjuraigōji scrolls that would maximize their pictorial and spatial meanings. The suggested layout reveals the simultaneous construction and the destruction of the six realms, mirroring the themes presented in the scrolls. The two axes, respectively, point to the physical space and the administrational space in-between the six realms, offering a potential means of escape. These two axes break the circle of the six realms and create a hopeful rhythm in the process of viewing and ritual practices. Insights from historical accounts of Enma halls shed light on the potential ritual functions of such a ritual space that the scrolls might have adorned.

Remarkably, the set of hanging scrolls in this three-dimensional display unfolds all six realms simultaneously, unlike the sequential order presented in handscrolls. Furthermore, viewers of the hanging scrolls, unlike those of handscrolls, have the freedom to embrace an enhanced illusion of spatial depth and explore various realms and scenes at will by moving around the room. This allows them to turn the wheel of the six realms both within and beyond the pictorial sphere. Eventually, the viewer is guided to realize that hell is a spatial construct not without an exit, as long as one is aware of the karmic bound and its possible thresholds.

6. Conclusions

This study re-examined the imagery of hell in the Shōjuraigōji Rokudō-e scrolls, emphasizing the inseparability of construction and destruction. It discussed the representation of several internal tensions within the hell space. Firstly, the limitless but enclosed space of hell is constructed as a cauldron-like landscape and a cage-like fortification. Secondly, in the hell-tearing narrative illustrations, the invisible but indexable boundary of hell is illustrated through architectural symbolism and spatial illusionism, encouraging viewers to metonymically break it and mentally traverse it. Thirdly, the confined but escapable space of the six realms is perceptible in both two-dimensional and three-dimensional ways, as the spatial setting for the scrolls potentially intertwines the wheel of the six realms with various kinds of exits. In these ways, the Shōjuraigōji scrolls, particularly the hell-related images, exemplify a significant systemization of spaces—encompassing the imaginary space, the representational space, and the physical space—in the development of Pictures of the Six Realms in Kamakura Japan.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This article was developed from a course paper written for Chelsea Foxwell’s graduate seminar at the University of Chicago in 2017 titled “Japanese Handscroll Paintings”. That version received the 2019–2020 Liu Cong Memorial Prize for the Best Essay on East Asian Art and Visual Culture, granted by the Center for the Art of East Asia, the University of Chicago. The revision of this article significantly benefited from comments of two anonymous reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For example, the Matsuda scroll is based on mezu rasetsu butsumyo kyo 馬頭羅刹仏名経, an apocryphal sutra and forgery Buddhist sutra compiled during the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE). It seems that this sutra is also titled foshuo foming jing 佛説佛名經 T14.0441. |

| 2 | Fukui Rikichirō, the proponent of this idea, suggests that the Go-Shirakawa scroll is part of an entire set of six-realms paintings. His argument had been generally accepted until recently when the complexity in hell presentations was considered. For instance, considering the early Scrolls of Hells are based on different textual sources and are virtually distinct from the hell images in rokudō-e, Chusid suggests that, besides rokudō-e, there should be other genres such as the independent hell depiction, and the representation of the three evil realms of hell, hungry ghosts, and animals (Chusid 2016, pp. 18–19). |

| 3 | It seems that this scroll is designated for monastic viewers, as all the sinners have shaved heads, indicating them being Buddhist monks and nuns in their previous lives, and the inscription speaks about sinners who are monks but have broken the precepts of not drinking alcohol and not eating meat and therefore enter the hell. |

| 4 | The unrepresented hells are “the Hell of Wailing” (Kyōkan jigoku 叫喚地獄), “the Hell of Great Wailing” (Daikyōkan jigoku 大叫喚地獄), “the Hell of Scorching Heat” (Shōnetsu jigoku 焦熱地獄), and “the Hell of Great Scorching Heat” (Daishōnetsu jigoku焦熱地獄). For example, the Kitano scroll includes all eight hells, even though each is more abbreviated as one scene. |

| 5 | The Essentials mentions that this hell has seven circles of walls in total. |

| 6 | Only five realms are depicted, except for the realm of asuras. If it is not an error in the painting, perhaps there is a possibility of indicating that the asura realm is somehow special here like the kingdom of the wrathful king. It is interesting that here the king is mentioned to be in the remote realm, which is presumably a destiny driven by an evil karma as the remoteness displayed in the hell gates. |

| 7 | An uncertainty in my proposal pertains to the order of placing the realm of asuras above (or after, in viewing sequence) the human realm rather than below. The Chinese tradition typically follows this order, while the Japanese tradition often places the realm of asuras below (or before, in viewing sequence) the human realm. The ambiguity in the Shojuraigoji set arises because the only depiction of these realms together is in the narrative scrolls, where the realm of asuras is omitted, making it challenging to determine its relationship with the human realm. |

| 8 | Infiltration refers to the understanding that a devotee is still within the world of transmigration although their pain would be alleviated by Kannon 觀音 (Skt: Avalokiteśvara) and Jizo Bodhisattvas. Transcendence means escaping the six realms through the notion of a transcendental locality such as the Western Pure Land. Copenetration is a combination of the former two modes that developed within the Tendai school. Based on the expansion of the six realms into the ten worlds (jikkai 十界), to which four nirvanic levels are added above, this mode implies total interpenetration with the concept of “each world is equipped within its own ten worlds”. Lastly, ludization conveys the radical relativizing of the six realms and the conception of them as an arena of play. |

| 9 | The images depict the tales of falling into the pond of hell and the salvation from hell. |

| 10 | It should be noted that although Ryōzen’in is conventionally considered to be the original context for the scrolls, because of the first repair documentation, Yamamoto and Crusid reconsider this possibility. Crusid convincingly argues that it might not be so because Ryōzen’in was not recorded to have any association with the Essentials; also, it is instructional of Genshin. She offers an alternative possibility of Shuryōgon’in Cloister 首楞厳院, where Genshin composed the Essentials and it is probably where the Shōjuraigōji scrolls were originally designed for. |

References

- Chusid, Miriam. 2016. Picturing the Afterlife: The Shōjuraigōji Six Paths Scrolls and Salvation in Medieval Japan. Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Chusid, Miriam. 2019. Constructing the Afterlife, Reenvisioning Salvation: Enma Halls and Enma Veneration in Medieval Japan. Archives of Asian Art 69: 21–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxwell, Chelsea. 2016. The Pulled Back View: The Illustrated Life of Ippen and the Visibility of Karma in Medieval Japan. Archives of Asian Art 65: 25–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, Rikichirō. 1998. Fukui Rikichirō bijutsushi ronshū. Tōkyō: Chūō Kōron Bijutsu Shuppan, vol. 2, pp. 33–79, Reprint of Fukui’s 1931 essay in Shinrigaku oyobi geijutsu no kenkyū. Edited by Kuwata Yoshizō. Tokyo: Kaizōsha. [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa, Caroline. 2008. The Inflatable, Collapsible Kingdom of Retribution: A Primer on Japanese Hell Imagery and Imagination. Monumenta Nipponica 63: 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirasawa, Caroline. 2012. Cracking Cauldrons and Babies on Blossoms: The Relocation of Salvation in Japanese Hell Painting. Artibus Asiae 72: 5–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ienaga, Saburō. 1960. Jigoku Zōshi: Gaki Zōshi. Yamai Zōshi. Tōkyō: Kadokawa Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida, Mizumaro, ed. 1970. Nihon shisō taikei: Genshin. Tōkyō: Iwanami Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Izumi, Takeo, Makoto Kasuya, Satomi Nishiyama Yamamoto, and Morio Kanai. 2007. Kokuhō Rokudōe. Tōkyō: Chūō Kōron Bijutsu Shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Kanda, Fusae. 2005. Behind the Sensationalism: Images of a Decaying Corpse in Japanese Buddhist Art. Art Bulletin 87: 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keikai. 1973. Miraculous Stories from the Japanese Buddhist Tradition: The Nihon Ryōiki of the Monk Kyōkai. Translated and Annotated with an Introduction by Kyoto Motomochi Nakamura. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu, Shigemi. 1978. Nihon emaki taisei. v.21, Kitano tenjin engi. Tōkyō: Chūō Kōronsha. [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu, Shigemi. 1981–1985. Zoku Nihon emaki taisei. v. 7. Tōkyō: Chūō Kōronsha. [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu, Shigemi. 1987. Gaki Zōshi. Jigoku Zōshi. Yamai Zōshi. Kusōshi Emaki. Tōkyō: Chūō Kōronsha. [Google Scholar]

- LaFleur, William R. 1986. In and out The Rokudo: Kyokai and The Formation of Medieval Japan. In The Karma of Words: Buddhism and the Literary Arts in Medieval Japan. Edited by William R. LaFleur. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 26–59. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Sicheng. 2001. Liang Sicheng quanji [Complete Collection of Liang Sicheng]. Beijing: Zhongguo Jianzhu Gongye Chubanshe, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Lippit, Seiji M., ed. 1999. The Essential Akutagawa. New York: Marsilio Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Mika, Abe. 2004. Daigoji Enmadō shiryō sandai. Kokuritsu rekishi minzoku hakubutsukan kenkyū hōkoku 109: 206–7. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti, Costantino. 2019. Scenes of Hell and Damnation in Dunhuang Murals. Arts Asiatiques 74: 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nara National Museum. 1990. Special Exhibition: Depictions of Buddhist Scriptures. Nara: Nara National Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Ōgushi, Sumio. 1954. Kenkyū shiryō: Hōjōji jissaidō no jigokue. Bijutsu kenkyū 176: 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, Robert F. 2007. Ōjōyōshū, Nihon Ōjō Gokuraku-ki, and the Construction of Pure Land Discourse in Heian Japan. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 34: 254–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Shūei. 2004. Kamakura jidai no butsumyōe. Indogaku bukkyōgaku kenkyū 53: 237–45. [Google Scholar]

- Takakusu, Junjirō, and Watanabe Kaigyoku, eds. 1924–1933. Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō. Tokyo: Taishō/Issai-Kyō Kankō kwai, 100 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi, Haruko. 2009. Officials of the Afterworld: Ono No Takamura and the Ten Kings of Hell in the Chikurinji Engi Illustrated Scrolls. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 36: 319–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Hung. 2022. Zhongguo huihua: Yuangu zhi Tang [Chinese Paintings: From the Remote Ancient to the Tang]. Shanghai: Shanghai Renmin Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Mo. 2017. Zhongguo jianzhu yishu shi [History of Architectural Art in China]. Beijing: Zhongguo Jianzhu Gongye Chubanshe, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, Satomi. 2011. Kaisōkasareta jigoku: Shōjuraigōji-zō ‘Rokudōe’ jigoku fuku yonpukuoyobi Enma-ō chō fuku no kōzu o megutte. Kyōritsu Joshi Daigaku Bungei Gakubu kiyō 57: 117–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, Satomi. 2012. Shōjuraigōji-zō ‘Rokudōe’ Enma-ō chō fuku to Enma ten zuzō. Kyōritsu joshi daigaku bungei gakubu kiyō 58: 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, Satomi. 2013. Toba Enma-tendō no ba to zōkei. In Zuzō kaishakugaku: Kenryoku totasha. Edited by Kasuya Makoto. Tōkyō: Chikurinsha, pp. 100–5. [Google Scholar]

- Yian, Goh Geok. 2015. Southeast Asian Images of Hell: Transmission and Adaptation. Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 101: 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).