Abstract

The Middle Ages and Early Modern periods saw the interpretation of reality through symbols, connecting the natural world to the divine using symbolic thinking and images. The idea of a correspondence between the human and universal macrocosm was prominent in various fields such as medicine, philosophy, and religion. Symbolism played a crucial role in approaching divine matters, with symbols serving as a means of direct presence and embodiment. Plato’s influence on Neoplatonist and Hermetic thinkers emphasized the role of dreams and eidola (images) for interpreting the divine. Contemplation of art and nature was an epistemological tool, seeking hidden cosmic harmony and understanding. Christianity embraced worshiping images as representations of the divine, granting believers a way to understand religious concepts. Icons were considered mirrors reflecting the spiritual and divine aspects. The medieval concept of speculum books as mirrors containing all knowledge offered instructional and subjective insights on various subjects. Speculum humanae salvationis illuminated books demonstrated the interplay between the Old and New Testaments, influencing artists like Rogier van der Weyden.

| Mirrors: still no one knowing has told |

| What your essential nature is. |

| Rainer Maria Rilke, Sonnets to Orpheus, 2, III1 |

1. Introduction

The interpretation of reality, perceiving in nature or in the elements of events symbols of another reality, whether divine, intelligible, or similar concepts, stands out as one of the main characteristics of the epistemology of the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period, particularly through symbolic thinking and the use of images. During this period, thinkers believed in a connection between the human world and the divine, but this relationship was veiled and required interpretation and exegesis. This was an essential element of medieval and early modern aesthetics.

The idea of a correspondence between the human and universal macrocosm was prominent in various fields. Symbolism played a crucial role in approaching divine matters, with symbols serving as a means of direct presence and embodiment. The things represented were not only what they seemed. When a beholder looks at the images, this person should think about what they appear to be and who or what they connect with. There is a symbolic dimension that had to provoke in Nicholas of Cusa (1401–1464) words a symbolica investigatio, to grasp the divine.

To analyze this lineament, Christian theology is going to be crucial, but also the philosophic current from Plato to Middle Platonists, Neoplatonists, Hermetic thinkers, Nicholas of Cusa, and Hermetic-Neoplatonic thinkers of the Renaissance, above all Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) and Giordano Bruno (1548–1600). Therefore, in the context of interdisciplinary research, we will combine the analysis of visual culture from the perspective of art history with the use of philosophical and religious sources, drawing from both pagan and Christian authors and traditions. We will also consider some implications from the perspective of image anthropology, not forgetting literary studies, especially focusing on illuminated manuscripts.

Contemplation of art and of nature looking in them for hints constituted a common epistemological tool. Myths, alchemical engravings, celestial observations, and dreams were all used as sources of clues and hints for understanding the divine. Nevertheless, let us now delve into a particular case—the image—as both conduits of knowledge and communication and reflections of the divine. In medieval times, despite historical reservations stemming from their association with Pagan practices, Christianity underwent a transformative shift in its perception of imagery. Embracing the veneration of images as representations of the divine provided believers with a tangible means to comprehend religious concepts.

Icons held a special role, creating a space of presence and contemplation, not only of mere narration. The power of images lay in their ability to connect the viewer with the invisible reality of God, granting grace and miraculous powers. In medieval and early modern aesthetics, images’ indicative and intermediary features often overlapped. An image could indeed be both indicative and intermediary simultaneously; it could depict a biblical scene, representing a narrative, while also serving as a medium through which believers could engage with the divine story and possibly receive spiritual insight or grace. However, images also carried the risk, a way of conceiving them that culminated with reformists accusing the Church of idolatry.

Iconic images were mirrors reflecting the spiritual and divine aspects rather than the mundane. The use of the mirror metaphor linked images to a gateway for accessing the divine in a mental, not just physical, dimension. We will analyze the human notion of considering the image as a mirror that reflects the divine, through Christian aesthetics of Middle Ages and Early Modern periods, both similar in this aspect.

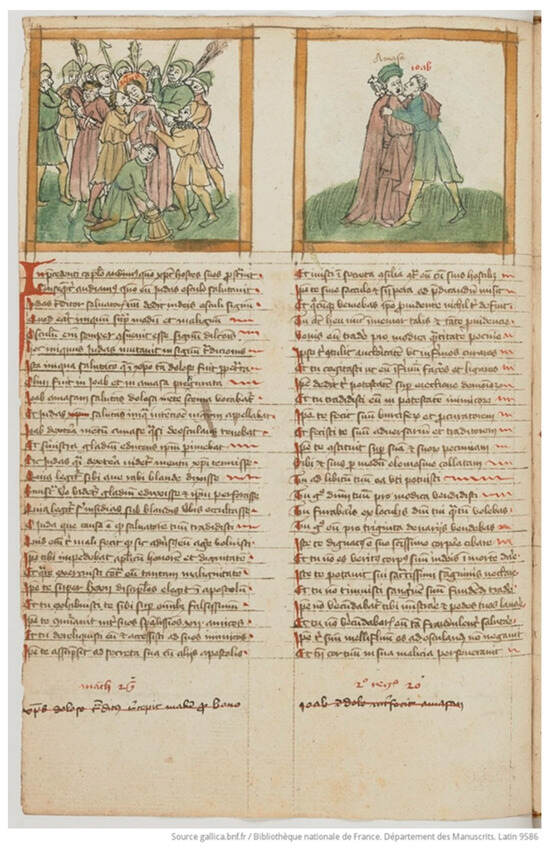

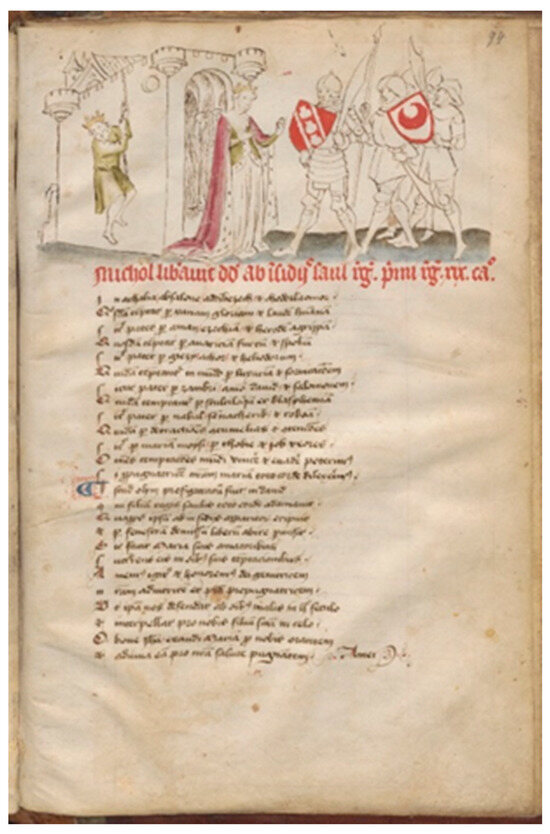

Finally, in the fifth section, as an exemplar embodying that mentality, the exploration will delve into medieval speculum books—conceived as mirrors containing comprehensive knowledge, spanning various fields such as alchemy, astrology, and astronomy. These “speculum” books served as proto encyclopedias, offering instructional, pedagogic and subjective insights on their subjects. Notably, Speculum humanae salvationis illuminated books demonstrated the interplay between the Old and New Testaments, with the Old serving as a mirror-image for the New (Figure 1). The Mirror of Human Salvation also provided lessons and analogies for understanding present events for late medieval and early modern societies. Different copies were created in Flanders and the Netherlands, influencing works by artists such as Jan Van Eyck, Robert Campin, and Rogier van der Weyden.

Figure 1.

Johannes Andreae/Anonymous, Speculum humanae salvationis, fifteenth century, National library of France, Latin 9586, f19v, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b105438116/f44 (accessed on 1 May 2024). Christ is betrayed, and Joab kills his brother Amasa.

2. A Method of Reasoning Based on Discernible Clues

One of the primary epistemological approaches to understanding reality during the medieval and early modern ages was to view this world as connected to another world by subtle clues placed here and there that were linked to the divine. However, these hints were not transparent and required effort in interpretation; exegesis was necessary.

Saint Paul (c.5–c.65 AD) famously stated that humans perceive reality and God dimly, like in a mirror (1 Cor 13:12).2 This phrase became well-known and found common usage among Christian thinkers, including those with roots in Platonism, such as Saint Augustine (354–430) and Nicholas of Cusa. The former extensively elaborated on the metaphor of Saint Paul in the concluding chapter of the City of God (426), where he discussed how the saint would come to see God directly, instead of through a looking glass, as humans perceive the world of flesh and bones.3 Nicholas of Cusa, on his part, agreed with Saint Paul: in this world, knowledge is acquired in a speculative and enigmatic manner because we possess only partial knowledge and prophesy in part in our quest for wisdom.4

The idea of an essential correspondence between the human and the universal macrocosm was one of the central principles in the medieval and early modern worldviews, encompassing various fields of knowledge, primarily medicine, philosophy, metaphysics, magic, and religion. According to this worldview, a profound connection exists between human beings and the universe, a sense of unity and fullness, a feeling of mystic participation in the whole, which links the individual with the macrocosm. This concept was even more central for Hermetic and Neoplatonic authors (Ferrer-Ventosa 2023, pp. 495–511).

As Nicholas of Cusa claimed, it was common to think that the pathway to approach divine matters was open to mankind only through symbols.5 This statement is even truer among Hermetic and Neoplatonic thinkers. A symbol does not define, describe, or represent but alludes to or suggests. In this sense, a symbol does not convey a concept but embodies a direct presence of the thing, albeit veiled (Cavallé 2008, p. 91). This is akin to icons, which do not represent a concept of Christ but share His presence in a particular way.

Pseudo-Dionysius (5th century) maintains that the Bible reveals teachings about angelic hierarchies through symbolic and anagogic means, using symbolic figures.6 Another notable thinker on this epistemological subject, Richard of Saint-Victor (1110–1173), proposed a system with four levels of vision and truth, using images as a means to progress from the corporeal to the spiritual in a hierarchical order (in Camille 1996, pp. 16–17). Something similar can be found in Dante (c. 1265–1321). He discussed the four senses he attributed to a possible symbol, with the anagogical sense of the symbol regarded by the great poet as the highest, surpassing the literal, the allegorical, and the moral. By pointing towards its transcendent, spiritual content, the symbol allows for reflection in that direction and builds bridges towards the intelligible.7

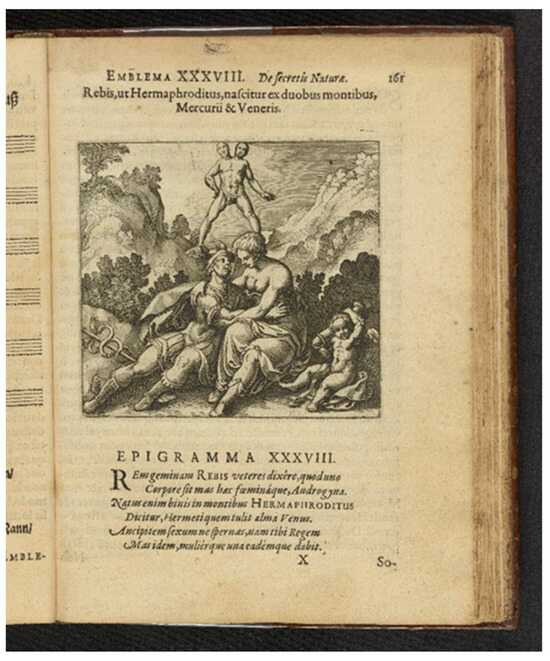

Various methods were chosen to unveil the truth behind the veil and open a path to the divine. One of the most effective approaches to understanding the divine was through the study of myths. Much like Plato (c. 423–348 BC) and his lineage of Renaissance Platonists, myths were believed to contain secrets that could not be easily translated into syllogisms (Zambelli 2012, p. 112). Alchemical engraving books, for instance, are replete with such mysteries (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Michael Maier/Johann Theodor de Bry, “Emblem XXXVIII, Atalanta fugiens, 1617, 161. https://doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-7300 (accessed on 1 May 2024). The love between Hermes and Aphrodite gave birth to Hermaphrodite.

But not only that: as an integral part of mysticism, alchemy employs images from the sensory world and visual metaphors to allude to a perception of supreme experience. The visible world serves as a gateway to something beyond what is seen. These symbols, as signals of a concealed truth, are deciphered through them and belong to a supernatural realm. These images may not be found in nature, yet paradoxically, they represent elements from the natural world, and their visual representations provide a golden path to access the symbolized truths. They bridge both the intelligible and the sensory realms in the soul and mind of the wise individual capable of reading and decoding them—a connoisseur who possesses the secret code of reality.

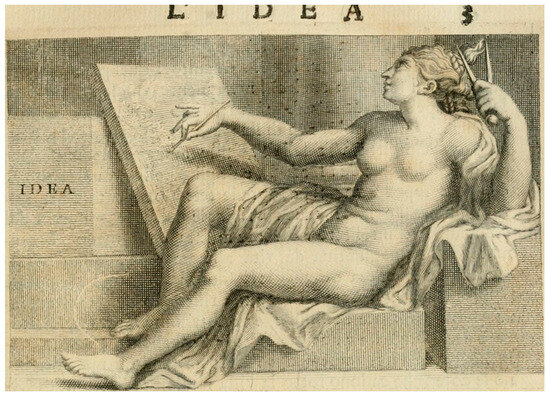

As an example, this Platonic perspective on art and life is visually presented for contemplation through images rather than texts, as seen in the engraving “Idea” in The Lives of the Modern Painters, Sculptors and Architects, created by Charles Errard (c. 1606–1689) for Giovanni Pietro Bellori (1613–1693). In this artwork, the idea is allegorized by a naked woman who gazes upward to the models of perfect beauty, adapting them using a compass and a paintbrush for the canvas (Stoichita 1997, pp. 92–94).8 Both things and images can guide us toward invisible truths (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Giovanni Pietro Bellori/Charles Errard, “L’idea”, Le vite de’ pittori, scultori et architetti moderni, 1672, 3. Source: Wikimedia.

One of the central figures in art history, Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472), maintained a similar perspective. He believed that the ability of painting to give form to the gods was the highest gift bestowed upon humanity.9 according to Alberti, this art form connects mankind with the divine and the piety of religion.

Another terrain for seeking clues was the observation of celestial bodies. During the Renaissance, the Christian Hermetic tradition sought insights by studying the stars (Ferrer-Ventosa 2023, pp. 496–499). Or dreams. During the Middle Ages, dreams served as a source of validation. For instance, consider the dream of Constantine (c. 272–337), in which Saint Peter and Saint Paul visit him. He does not recognize them until he sees an icon of these saints (García Avilés 2021, pp. 100–101). In this way, dreams can be seen as an example of the concept discussed here, where symbols function as mirrors reflecting divinity. This notion is not a new one and can be traced back to earlier times. For instance, in Artemidorus’ book on dream interpretation, there is no distinction between encountering a god in a dream and seeing their statue in a temple. Artemidorus (second century AD) discussed dreams that contained symbols hinting at future events, where the soul expressed forthcoming events enigmatically.10

Plato, the philosopher who was pivotal for Neoplatonist and Hermetic thinkers during the medieval period, and the Hermetic-Neoplatonists of the early modern era also considered dreams in a similar manner. Apart from Socrates’ daimon, which guided him through symbols, in his work Timaeus (71a-d), Plato asserts that humans possess an inner mirror where the gods project eidola, or images,11 as messages. These messages become more apparent when one is dreaming, and it is essential to interpret them correctly.

It may seem unusual, but the organ that receives these messages in the form of eidola or images is the liver, as it does not rely on reason. The liver serves as a link between the lower soul, driven by passions, and the higher soul, which is intellectual and logical. The liver conveys the intelligence’s concepts through images that prompt the appetitive soul to act according to the commands of the higher soul. In this section of Timaeus, the gods communicate their insights through dreams.12

We will conclude this section with Giordano Bruno, who provides a fitting transition to discuss the unique aspect of symbolic thinking through images explored within. Analogy played a fundamental role in Bruno’s worldview, but he did not emphasize logical relations among different elements. Instead, he favored associations, resemblances, magical sympathy, correspondences, and other possibilities. Bruno encourages transcending purely logical connections in his game of likeness outlined in On the Composition of Images (1591). For example, the philosopher highlights the similarity between the Latin words for ‘mirror’ (speculum) and ‘reflection’ (speculation),13 a connection partly retained in English.

Bruno’s creation of images represented a unique form of ekphrasis, where descriptions of visual material formed the core of his method. Bruno’s goal was to offer a richly imaginative world imbued with cosmological and ontological ideas. The theory of images in Giordano Bruno and its use in his methods will serve as a prelude to delve into the conception of the image as a mediator of the divine in Western Christianity.

3. Images as Hints

After delving into symbolic epistemology during the Middle Ages and early modern periods, let us now delve deeper, focusing on the iconic image as a clue or symbol towards the divine. For this theory of the iconic image, we will focus on the Catholic sphere and the critique of the image by Protestants, since the case study will be conducted with a Western European example, the Mirror of Human Salvation. In addition to the theory of the image within the cultural context of Central and Western Europe, some supplementary notes from visual culture and the anthropology of the image will be added to provide nuances and delve deeper into the subject.

As a means of sharing knowledge, images offer a type of understanding that synthesizes and transforms the sensory, serving as a product of the senses. When we analyze an image as a form of knowledge, it becomes a synthetic representation that consolidates a diverse range of data, enabling the conveyance of a set of information in a single communicative act.

From the sixth century onwards, Western Christianity embraced the worship of images as representations of the divine—visual cues aiding believers in comprehending otherwise elusive religious concepts. Saint Basil (330–378) and Saint John of Damascus (c. 675–749) laid the foundations for this inclination (González García 2015, p. 291).

The resolutions of the second Council of Nicaea (787) confirmed the continuation of traditional customs regarding icons and other images, allowing their placement inside churches. Some reasons cited included the preservation of tradition, drawing from predominantly Roman and Greek pagan cultures, the use of appropriate colors, forms, and materials. Additionally, through contemplating these images, believers could experience the divine models or archetypes such as Jesus Christ and the saints, offering honor and veneration to the individuals represented by those images. The value of images as intermediaries was so significant that St. Hedwig of Silesia (1174–1243) was buried with an image she cherished, holding it in her hands until her death, and the image could not be separated from her grasp (Camille 1996, p. 130)

The right term to explain what happened was translatio ad prototypum. When believers worshiped a sacred image, such as that of Jesus, they were, in fact, worshiping the being represented through it—the archetype of that image. Similarly, when citizens honored the emperor’s image, they were honoring the real emperor, not the image itself. Otherwise, the citizen would be multiplying kings, acknowledging both the emperor and the emperor’s image. According to Saint Basil of Caesarea, only one archetype or original existed that was reflected in multiple images.14

Among images, icons had special features. The meaning and uses of icons were different from those of pictures depicting biblical episodes or narrative and historical scenes. Icons, akin to Hindu images, create a space of presence and contemplation rather than one of narration or representation (Favero 2021, p. 33). As visual anthropologist Paolo Favero argues, for icons, what they do is more important than what they represent (Favero 2021, p. 106).

In that visual culture, and often in mysticism, images served as visible representations of the invisible reality of God, acting as visible manifestations of God’s invisible nature. Nicholas of Cusa believed that the elusive truth becomes visible in the image, accessible solely through this enigmatic representation. Visual culture theorist William J. T. Mitchell claims that this dimension of revealing something inner and invisible is fundamental in understanding how images should be interpreted (Mitchell 1984, pp. 525–526).

Middle Ages aesthetic of vision conceived sight as something powerful,15 with images carrying a power of infection, to cast a spell on the viewers, to enchant them. Some cult images had a reputation for thaumaturgy, magic powers, and facilitating miracles. These iconic images pointed to something—the godhead—but also offered something else: the spiritual power to connect the believer with God.

Icons could impart grace (charis) and miraculous power (dynamis), as in the case of the Madonna of Blachernae, according to the medieval Neoplatonic Christian author Michael Psellus (c. 1018–1078). The same author spoke about an icon of Empress Zoe (978–1050) with oracular powers, depending on their colors; if the icon turned pale, that was a sign of impending disappointment, but if the icon shone with fiery colors and radiant light, the future was to bring brightness (Belting 1994, pp. 511–512).

Images could even carry power to facilitate indulgences, with engravings containing inscriptions for the Otherworld salvation of the believer, as in a case exposed by Michael Camille with an image of Gregory the Great (c. 540–604). Moreover, far from diminishing the power of images, the arrival of printing permitted the copying and sharing of power with wider audiences (Camille 1996, p. 120).

As a consequence, icons underwent a shift in their categorization from mere objects to a change in their intrinsic value. Their significance was no longer anchored in their materiality but rather in their form. Belting, highlighting the Platonic roots of this theory of value, emphasizes the “resemblance of the image to its original” (Belting 1994, p. 183).

In 1582, Gabriele Paleotti, the archbishop of Bologna, deemed it orthodox for Christians to venerate images, provided they focused on the prototype represented by the image and disregarded the material aspects. This devotion was categorized into latria (devotion for God), hyperdulia (veneration for the Virgin), and dulia (respect for the saints) (Belting 1994, pp. 555–556). Despite differing philosophical assumptions, Giordano Bruno echoed this Platonic direction, stating that through images, one aspires not only to other images but also to the forms constituting those images.16

Analyzing Yolngu paintings, anthropologist Howard Morphy identifies a parallel with the medieval aesthetic discussed here. These artworks transcend mere representation; they share the essence of something, at least theoretically for the original recipients of these pieces. In the Middle Ages, people considered such works divine, akin to the sacred-law status accorded by the Yolngu people. A distinguished artist, then, could link the icon with that essence, showcasing artistic skills to meet this challenge (Morphy 1994, pp. 181–208).

For the power of images, they were both admired and feared. In this worldview, the advised attitude was to avoid becoming fascinated by the image, to refrain from being captivated by it. Instead, the beholder should act in the opposite manner, using the image as a springboard to reach the thing represented—to reach God, as recommended by the words of San Juan de la Cruz in Ascent of Mount Carmel.17

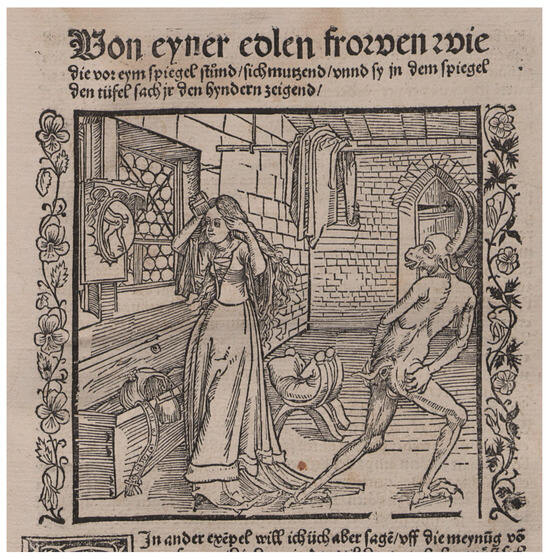

To prevent idolatry, Catholicism always emphasized that the Church devoted itself to the thing represented in the picture, not to the picture itself, as Pagans did. The Devil could infiltrate them, much like in the case of a mirror. An engraving by the young Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) in Dans Der Ritter vom Turn (1493) (Figure 4) illustrates the medieval adage that the mirror is the Devil’s true ass (Baltrusaitis 1978, p. 193). The same caution can be applied to images.

Figure 4.

Geoffroy La Tour Landry, Der Ritter vom Turn von den Exempeln der gotsforcht vnd erberkait, 1493. Engraving (parchment). Bayerische Staatsbibliothek Münich, Rar. 631, 19v (detail) https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/view/bsb00029711?page=42,43 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

Precisely, this point was crucial for the movements opposing the magic power of images. Reformists accused the Church of idolatry toward images and imagery. In an accompanying text associated with an image depicting iconoclastic attacks, created by the woodcut designer Erhard Schoen (c. 1530) (Figure 5), the images blame humankind for creating them but later turning them into idols (Belting 1994, p. 463).

Figure 5.

Erhard Schön, Complaint of the Poor Persecuted Idols, c. 1530. Engraving. Source: Wikimedia.

Luther specifically sought to forbid the cult of images, not all images per se. He was not concerned with those that filled private picture cabinets, as those could be collected without prejudice. Luther accepted images containing biblical episodes, with narrative features, as he found them useful in presenting stories like a mirror, using the metaphor applied here. In contrast to Luther, Calvin also employed the mirror metaphor, but instead of associating it with images, he referred to something that allows one to see God, replacing images with words. The Word of God, like a mirror, allows us to see Him (Calvin 1994, pp. 550–551). The Calvinist critique of images accepted them only as representations of the visible world, detaching them from the realm of the sacred. Consequently, images ceased to be hints to the divine.

The epistemology of iconic images, akin to mirrors reflecting the spiritual, the pure, and the divine, operates in a manner similar to hermetic texts: they possess a literal meaning but also harbor a hidden key decipherable by the wise, containing multiple layers of significance. The psychological role of mirrors, the gaze implied, and the epistemology derived of looking at a reflection on them, has as consequence, “to lay the foundation for analogical reasoning and to aid symbolic thought” (Melchior-Bonnet 2001, p. 270).

Using a mirror as a metaphor for referring another thing was highly common in the period analyzed and in several ways. For instance, in medieval epistemology, seeing the things on the mirror should facilitate a reflection. As in Plato and Plotinus (c. 205–270), the image in the mirror could be true, as far as it is the reflection of the original in front of it, but that image lacked essence, hence is not real, meant that that is not the original thing, it is only a copy made image, as Plato pointed it.

In The Republic, he compared the production of works to images with reflections in mirrors. Just as the surface reflected in a mirror shows things that exist outside of it but are not within it or its interior, thus a mere reproduction lacking internal reality, the same applies to human-made artificial images. Mere appearances without true consistency (see endnote 11). In fact, the analogy of the arts, and more specifically, painting with the mirror, is employed by Plato when Socrates argues the reason why poetry must be prohibited from the ideal city. He thinks about visual arts, especially painting, as the act of placing a mirror in front of something, creating something apparent, mirages (Ferrer-Ventosa 2024).

Pedagogy was also a matter of mirroring for Platonists. The education through examples employed the lives of saints as rhetorical, epidictic Christianized models, attempting to universalize those lives as originals reflected in the mirror of believers’ lives—a typus to be emulated (González García 2015, p. 382). This tradition already came from Pagan Platonism, such as Plutarch’s Parallel Lives (96–117), serving as a means for readers to analyse human nature and themselves. In medieval mystical epistemology, the human being was conceived of as looking at divinity through a mirror, following Saint Paul’s famous statement already cited. Similarly, the Virgin was considered speculum sine macula.

The tendency in that period was to judge mirrors as something for revealing a sacred and hidden truth. According to Nicholas of Cusa, we see eternity in a mirror, an icon, a symbolism, while God’s sight is a living mirror—an eye that sees everything within itself.18 The Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680), highly influenced by Hermetism, claimed in a fragment that all things are mirrors in which the rays of divine wisdom would be reflected (in Yates 1964, p. 418).

Another philosopher of the Renaissance strongly influenced by Hermetic and Neoplatonic philosophers, Marsilio Ficino, who mingled Plato, Proclus (412–485), and the Corpus hermeticum, explicitly used the metaphor. God shines in three mirrors, in all of them is found the divine ray of the fecund power of creation: shining in the world as forms or images; brighter in the souls as reasons or concepts; and brightest in the angels as archetypes or ideas. Moreover, these three mirrors reflect divine rays gradually becoming fainter, from angels to the world.19 In his conception, the mirror functions paradoxically as a medium of transmission. At the same time, and for the same process, it lowers the level of the divine order as it descends to matter (Kodera 2002, p. 299).

Ficino maintained that the works of architects and painters reflect their mind and soul, in the same way that a mirror reflects a person who looks into it. In a fragment that belongs to his Theologia platonica (1482) he claims: “For in these works the rational soul expresses and delineates itself, just as a man’s face gazing in a mirror forms itself in the mirror”.20 According to Ficino, an artist places his soul into the painting, so it becomes a mirror of his creative soul. And the more it serves as a mirror of the subject’s inner self, not their external appearance, the higher its quality as a mirror will be.

Imagination served as the human organ for this process of conversion, functioning as a mirror in itself. A remarkable author with a huge influence on Hermetism and extensively cited here, Giordano Bruno, maintained that the imagination was an inner sense which keeps in contact with the divinity of each human being. This theory proves the influence in Bruno of some Neoplatonic authors of the Late Antiquity, such as Synesius (373–414). Bruno considered this inner sense as a way to link with daimons, angels and other beings (Yates 1964, pp. 335–336).

The extensive power of imagination was a common feature of medieval thinking. For instance, Albertus Magnus (c. 1200–1280), quoting Avicenna (980–1037), asserted that whoever was afraid of leprosy finally became a leper (Zambelli 2012, p. 17). Furthermore, for the mindset discussed in this context, which includes Hermetic and Neoplatonic thinkers, the powers of imagination were even broader than in other philosophical backgrounds. According to this perspective, imagination was the power that explained certain supernatural phenomena, utilizing images for its application.

In those collected from Hermetic Arabic culture, we find the same value granted to imagination, for instance, in Picatrix (c. 1050) and al-Kindi (c. 800–c. 873). According to Al-Kindi, the process of knowledge and willingness starts with the imagination, when human being wants something; this person imagines, giving a shape to this wish; this form embodies in an image, and then this person shall evaluate if that thing is useful, wishing it or rejecting it depending on this estimation.21 But a point to underline here is the value granted to the images—first mental, later physical—, and to the imagination in these schools.

Images have traditionally been linked to imagination, serving as the language of imagination (Ferrer Ventosa 2021, pp. 75–102). As James Elkins claims: “Imagination is a place inhabited by images” (Elkins 1996, p. 224). For icons and also for narrative altarpieces imagination possessed a fundamental value. Contemplating the tableaus and other sacred images should help develop an inner view, training the imagination and inspiring visions. Remembering the episodes related to the images was another effect that images triggered to make the believers’ vision stronger (Belting 1994, p. 362).

Icons were image-mirrors reflecting the divine. In a theological dispute in Mallorca in 1276 between a Christian and a Jew, the latter accuses the former of idolatry for worshiping images, but the former counters that a Christian actually worships only God and Jesus Christ, while the images placed by the Church serve as mirrors. Through these mirrors, the faithful can contemplate with the eyes of the mind and heart what their physical eyes see (in García Avilés 2021, p. 41), through them, they will comprehend the sacred mysteries. These images act as mediators, facilitating access to the divine. What is significant is the reuse of the metaphor, equating the image with a mirror, which serves as a gateway to another dimension, not physical but mental.

4. Human as a Hint That Mirrors God

This mindset used metaphor to describe the relationship between the human soul and, more directly, humans as mirror-images of God. How does something that does not have a material form manifest? The metaphor will help in this sense. This paradox will challenge believers in the three “People of the Book” religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Therefore, this also explains their ambivalent, contradictory, and tensional relationship with images.

According to the specialist in Jewish mysticism, Elliot R. Wolfson, the problem of expressing the incorporeal God in words and concepts was solved in the Jewish mystic tradition with the term dimmuyot, images, or even more, the Latin figurae ontic manifestations of the divine captured by the imagination of the mystic, and then put into words or images in different metaphors: God as the warrior, the Ancient of the days and other hypostasis in which God appears to mystics and prophets (Wolfson 1994, pp. 33–41). Human form would have special value in those sources: “God does appear to human beings in different forms, including most importantly that of an anthropos” (Ibid, p. 395).

Taking a closer look at the main sources for this article—Hermetic and Neoplatonic—we find that the mirror-metaphor stands out. As in Jewish mysticism, the Corpus Hermeticum (third century) claims that the invisible God has no image but contains everything in His imagination, being the source from which all images and forms come. God is a force that imagines all things.22 The primordial man, image of God, had descended to the matter, in love with it, after saw in the waters his reflection and upon the earth his shadow. Man loved that image in nature and wished to inhabit there.23

The Neoplatonic thinkers, such as Michael Psellus, believed in the androgyne and the primordial human as an image mirroring God. Meditating about the famous versicle on Genesis 1:26, Psellus pointed that mankind was made as an image of God, capable of improving themselves, imperfect beings to perfect themselves, to reach a likeness with the divinity. Human beings can go on for the path of goodness or fall down, unable to assimilate beauty. But he modified the notion of invariable archetypes found in ancient icons, no longer considering them immutable. Instead, he emphasized denoting the character, particular emotions, and even pain of the figures depicted in the icons (in Belting 1994, pp. 529–530). According to another Neoplatonic thinker, Plotinus, the representation of something is able to receive the influence of its original,24 the reflection from the model, so to speak, that means that something divine shines in mankind.

Needless to say, Christian authors influenced by these ideas blended them with Christian theology. Jesus, the son of God, was considered His image, and it could be represented in an image because he had embodied, while the Father lacked a body and was invisible, making Him impossible to represent in an image; only the symbol could provide a hint of God’s presence. Representing aspects of Christian history, such as Jesus’s passion, could lead the Christian spirit to spiritual truth.

According to Saint Paul’s famous declaration, human beings were made in the image of God but were also considered as the shadow of God or of the Holy Spirit by some Christian theologians of the Middle Ages, and for Christian authors, above all from eleventh century on, love and emotion stood out as a major way to reach God.

Nicholas of Cusa explains God’s omniscience, all-seeing, using a simile that comes from icons. God sees everything, much like the figures in those icons whose gaze seems to follow the audience for a trompe l’oeil effect, transmitting that sensation to each person in the audience as if the icon gaze were unique for each individual.25 God’s Absolute Sight acts comparably.

Moreover, in the same text, Nicholas of Cusa employs the mirror metaphor, asserting that the icon is like a mirror that reflects eternal life. When observing this image of eternity, each human being sees not their own image in the mirror, the Form of forms, but the truth, of which each human being is an image. Because God is the original of everything that exists, the supreme archetype about which humans are copies.26 Ontological resemblance stands out as fundamental for the notion of man as an image of God (Melchior-Bonnet 2001, p. 226). Aesthetically, this characteristic will culminate with Dürer’s Self-portrait (1500), where he presents himself adorned with the forms of Christ (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Albrecht Dürer. Self-Portrait at Twenty-Eight, 1500, Alte Pinakothek Münich.

And this use reaches up to a Renaissance philosopher that embraces this tradition, Marsilio Ficino. In his Theologia platonica, the metaphor is employed in different ways. For instance, in one of them, the human mind is compared. In another, nature is considered the mirror of God.27 Nature is a shadow in which God looks; the divine glance shapes the shadow, turning it into a mirror that reflects the image of God.28 The beauty of the world and the nature mirrors the divine, or speculum dei.

5. Speculum: Medieval Books as Mirrors of Comprehensive Knowledge

In this analysis, we have transitioned from the general (symbolic thought as the golden pathway in medieval epistemology) to a more concrete illustration of this trend, with the iconic image reflecting the divine. Subsequently, we have delved into the concept of humanity as a mirror-image of God (derived from Jesus as the prototype of humanity). For this final section preceding the conclusions, we will explore one more specific case exemplifying the preceding concepts: the speculum books, particularly the Mirror of Human Salvation, as an outstanding instance of these ideas.

This mode of thinking, through supernatural analogy, wherein the natural mirrored the intelligible or established similar relations, while the wise sought hints to the divine in the natural, found an exemplar in books bearing ‘speculum’ in their titles. The Latin term specio, meaning to look, traces its roots to the Indo-European base *spek, which means to look. It gave rise to two forms: the noun ‘speculum,’ meaning mirror, and the verb speculari, meaning to speculate, to look from above, and watchtower; both share this common root.29

In a seminal study, originally published in 1898, Émile Mâle already connected various ‘Mirror’ books to the iconography and culture of the Middle Ages (Mâle 1984). Speculum literature comprised studies focused on a single subject with instructional purposes and often a subjective approach. One common manifestation was in the genre of proto-encyclopedias; books like Speculum historiale, Speculum morale, and Speculum mundi appeared in numerous titles with diverse meanings related to manifold subjects, with the term ‘speculum’ denoting a proto-encyclopedia of that subject (Beaujour 1982, pp. 193–195; Rivera Dorado 2004, p. 44; Melchior-Bonnet 2001, pp. 111–115). Arguably, one of the most remarkable and influential Middle Ages works was Speculum Maius by Vincent of Beauvais, considered a foremost precursor to encyclopedias and was written around 1250. It serves as a compendium of knowledge from the Medieval Era.

For instance, mirrors for princes constituted a subgenre, sharing the same pedagogic aim mentioned earlier. In this case, these books provided good examples for instructing kings or the nobility in general, offering images for them to mirror behaviors and reflect on those examples. Furthermore, in the Middle Ages (and likely applicable to other periods), the court served as a mirror for the rest of society.

Alchemy stands out as one of the subgenres with many examples, such as the Speculum alchemiae attributed to Arnau de Vilanova (c. 1240–c. 1311), and the Speculum alchemiae attributed to Roger Bacon (c. 1220–c. 1292), among many others, because it was very frequent in alchemy. For astrology or astronomy, we also find several examples, such as Francesco Giuntini’s Speculum astrologiae (1573), featuring calendars of birth dates for Renaissance celebrities, and the Speculum astronomiae, attributed to Albertus Magnus and probably written by him. Even examples as peculiar as the antisemitic book Johannes Pfefferkorn’s The Jews’ Mirror (1508), with the particularity of being written by a Jewish convert to Christianity. He proposed to burn Hebrew books like the Talmud (c. 200–c. 500) with the fervor of the convert.

An astonishing kind of book and perhaps the best example that demonstrates the thought system presented in this work is Speculum humanae salvationis. The book works as a mirror “in which the redemption of humanity becomes visible” (Cardon 1996, p. 36). It should serve as an illuminated book to help the believer by serving as a mirror in which they could see and learn, with the images providing an allegorical lesson about rightness or evilness. Silber mentioned in 1980 that more than 380 manuscripts from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries of the Speculum Humanae Salvationis had survived (Silber 1980, p. 33).30

As Elina Gertsman and Barbara H. Rosenwein claim: “Its popularity is clear from the great number of manuscripts and printed books that contain its texts (and almost always images), and by the fact that translations from Latin were made into English, French, German, Dutch, and Czech” (Gertsman and Rosenwein 2018, pp. 98–99).

Speculum Humanae Salvationis (Figure 7) belongs to the illuminated books on historical symbolism, typology, or the figurative method, encompassing biblical typological thinking. These illuminated books view the Old Testament as a prefiguration or prototipus of the New, antitipus, the logical culmination (Cardon 1996, p. 1; Silber 1980, p. 33; Labriola and Smeltz 2002, p. 2). The literal text of the Old Testament becomes a mere allegory, with its referential dimension transforming into a self-reference, a disguise anticipating Jesus’ life. For instance, the incarnation of Jesus, depicted in the Nativity scene in the stable in Bethlehem, could be celebrated in the same scenario as King David’s old palace (Stoichita 1997, p. 84).

Figure 7.

Anonymous. Spegel der minschlichen Salicheyt. Speculum humanae salvationis, c. 1425, Royal Library Copenhagen, GKS 79 folio, p. 194 http://www5.kb.dk/manus/vmanus/2011/dec/ha/object84961/da#kbOSD-0=page:194 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

The Mirror of Human Salvation was not a unique example. According to Albert C. Labriola and John W. Smeltz, the main influence for the book was the Bible of the Poor, with examples dating back to the twelfth century (Labriola and Smeltz 2002, pp. 3–4). The typological method, where Old Testament scenes prefigure episodes in Christ’s life, was a common feature in Illuminated Books created in the Southern Netherlands during the period 1425–1450 (Cardon 1996, p. 325). In fact, Christ himself preached using typology, drawing examples from the Old Testament to explain his parables because “[a]ll this took place to fulfill what the Lord had said through the prophet” (Mt. 1:22–23). Paul the Apostle also employed the figural method to explain episodes from Christ’s life and the lives of the new Christians and their time.

Following medieval hermeneutics, with Dante’s four categories already mentioned (literal, allegorical, moral, and anagogical meanings), the Mirror of Human Salvation serves as a clear example of the complexity in which these categories intertwine, with the literal triggering the other ones. Therefore, it was widespread in Christian exegesis, epistemology, and visual culture. Analogies of this kind were common in the artistic production of the Middle Ages, particularly in Illuminated manuscripts.31

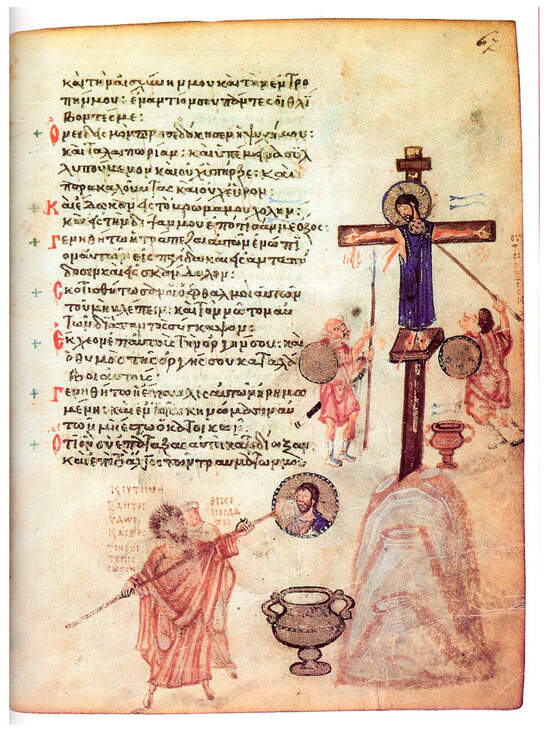

For instance, the famous Chludov Psalter (ninth century) (Figure 8) proposes a visual link between the Jews who offered a vinegar-soaked sponge to Christ on the cross and the iconoclasts who destroyed icons by wiping them with a sponge, erasing the memory of the images. The iconoclast in the image repaints the icon using something similar to a lance, echoing the actions of the Jews in the episode of Christ (Walter 1987, p. 216; Corrigan 1992, pp. 30–31)

Figure 8.

Anonymous. Chludov Psalter, c. 850, Moscow State Historical Museum MS. D.129, folio 67r.

In the same Chludov Psalter, on another folio illustrating Psalm 51:9, an analogy is drawn between the clash of Saint Peter vs. Simon Magus and the conflict between a patriarch and his enemy, an iconoclast (Corrigan 1992, pp. 27–28). The patriarch is represented in the image with gestures of victory borrowed from Roman body symbolism. The episode from the past serves to explain the iconoclastic conflict of the time, around the year 845 in Byzantium.

This type of epistemology through biblical analogy can still be observed in some masterpieces by Diego Velázquez (1599–1660). However, the game is played slightly differently and more intellectually, with clever allusions filled with irony. In works such as Christ in the House of Martha and Mary (1618) (Figure 9) and The Kitchen Maid (1622), Velázquez disguises ordinary scenes from daily life with episodes from the New Testament, presenting them side by side. These New Testament episodes are projected into Velázquez’s contemporary setting, featuring humble surroundings with women busy in the kitchen.

Figure 9.

Diego Velázquez, Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, 1618. Oil on canvas. National Gallery, London. Source: wikiart.

Both paintings should be considered, in the first place, as metapictures, regardless of the two main interpretations raised from them—whether interpreted as paintings inside other paintings or as windows opened to other rooms (see Stoichita 1993, pp. 21–27). However, the visual inspiration comes from the biblical analogy device presented in the Chludov Psalter and the Mirror of Human Salvation. This complexity and indirect correspondences need to be considered when scholars analyze medieval visual culture. Such analogies were depicted in the iconographic motifs of books and paintings and in the frescoes and altarpieces of churches and cathedrals.

From the Christian perspective in the medieval period (and beyond), the Old and New Testaments served as mirrors of each other. However, it was a peculiar mirror that reflected retrospectively into the past, where the original was the New and the secondary was the Old, even though the latter historically predates the former. In the Speculum Humanae Salvationis, the dominance of the New Testament influenced various aspects, such as sometimes richer decoration of the margins for the New, while the Old was presented in simple ink work, among other treatment variations (Cardon 1996, pp. 9–12). In this sense, the Old functioned as a mirror-image for the New.

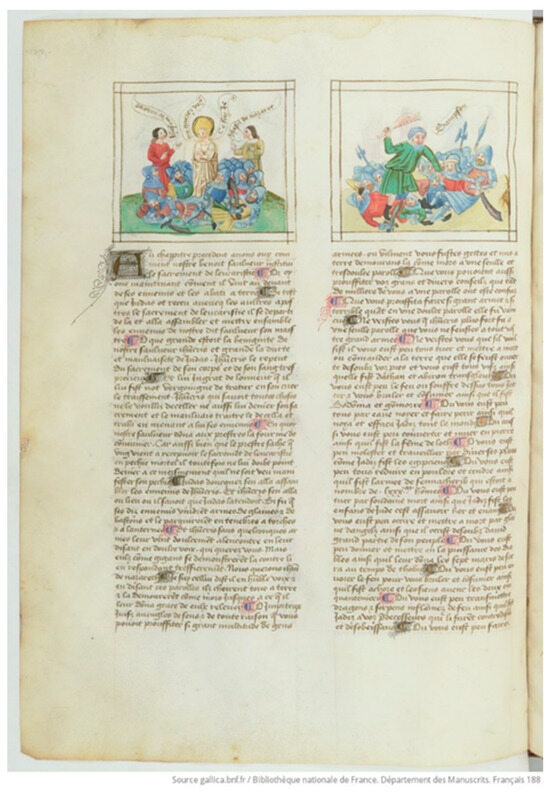

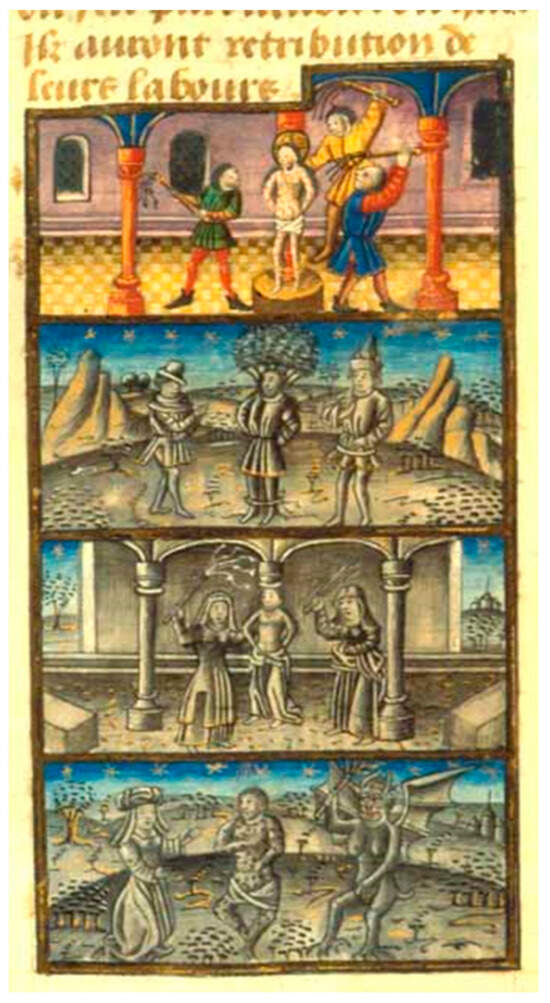

In various languages, different copies of the Speculum Humanae Salvationis were created by masters and groups, mostly but not exclusively located in Flanders and the Netherlands. The illuminations on the pages can be arranged with one illustration; two, perhaps the most common form; or even in four columns or four horizontal registers per folio. The left column of each page often features an episode from the New Testament, while the right column depicts the equivalent from the Old Testament. For example, in a volume at the National Library of France, Christ’s arrest is portrayed at the left of the folio, and Samson fighting against the Philistines is depicted at the right (Figure 10). In other volumes, the left folio may contain the New Testament episode, and the right folio may feature the Old Testament, or other variations may exist. Therefore, there is no fixed rule shared among all the books.

Figure 10.

Jean Miélot/Anonymous, Miroir d’humaine salvation, Fifteenth century, BNF Français 188 f21v https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b100223880/f46 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

At times, the treatment of color makes a difference in the significance of each image, with the images of the New Testament in color and the others rendered in grisaille or other variations. The illustrations’ convergence point can be identified in both the respective narratives and purely visual motifs. This is evident in folio 29 of a volume at the University of Glasgow library, where a central figure, typically bound, is depicted, surrounded by other figures inflicting torture upon him. The themes include Jesus Scourged, Achior scourged, Lamech tormented by his wives, and Job reviled by his wife and scourged by Satan (Figure 11). The same frontal composition unifies the four images, establishing thematic parallels and visual ones.

Figure 11.

Anonymous. Mirror of Human Salvation, 1455. Library of the University of Glasgow. Ms. hunter 60, f. 29v.

Like in the previous example (Figure 11), the reader can even find editions featuring four illustrations on some folios. For instance, we can find the following four episodes: The Virgin enthroned after her assumption, the Ark before which David harped, the Blessed Virgin Mary in Glory, and finally, Solomon placing his mother beside him. The analogies are rather subtle, encompassing the glory of the Virgin, other aspects of glory, maternity, and the recipient of the most holy being. Some of these images, such as the one with the Virgin enthroned, share similarities with works from the Flemish tradition (Cardon 1996, p. 277).

Prominent figures of the period, including Jan Van Eyck (1390–1441), Robert Campin (c. 1375–1444), and Rogier van der Weyden (c. 1400–1464), were influenced by different editions of the Speculum Humanae Salvationis in their works. Specifically, Rogier van der Weyden portrayed scenes of historical symbolism. As Bert Cardon rightly points out, in the Bladelin triptych, for instance, “[t]he components of the programme executed here are taken from the Speculum”. (Cardon 1996, p. 331). The left side, in particular, depicts the episode of Augustus and the vision of the Sibyl, who saw a Virgin and her son, telling Augustus that the child was the greatest man in the world. The large central panel illustrates the birth of Jesus, drawing a relationship that can be found in the Speculum Humanae Salvationis.

The book enjoyed immense success, and Edward J. Olszewski explains that the preference for triptychs from the trecento onward can be attributed to the widespread influence of the Mirror of Human Salvation. This preference stemmed from religious symbolic reasons, with the triptych format referencing the three pinnacles of Solomon’s temple, seen as a prefiguration of the Virgin Mary due to her triple golden celestial crown. This relationship elevated the popularity of the triptych format, particularly during the Gothic age, characterized by a profound devotion to the Virgin Mary (Olszewski 2009, p. 5).

Furthermore, the Mirror of Human Salvation not only served as a juxtaposition of the Old and New Testaments but also held pedagogical significance, as discussed earlier. The biblical episodes provided tools for understanding contemporary events properly. Authorities in the fifteenth century sought to leverage the lessons embedded in the book, presenting themselves as new personifications or vicars of the divine, with a crucial role in God’s plan. For example, the Burgundian duke Philip the Good (1396–1467) “mirrored himself on the past or used the past to justify his own deeds and plans” (Cardon 1996, p. 346), with the past referring to scenes from the Testaments, read through the lens of typology. Biblical characters were interpreted as ancient predecessors of the duke, the House of Burgundy, and other princely circles, serving as models to be imitated in the mirror. This exemplifies biblical typological thinking and its application to contemporary lives, where books served as keys to shed light on the present.

6. Conclusions

In medieval and early modern thought, a profound interrelation pervaded symbolic cognition, imagery, and the pursuit of divine truths. Images served as the nexus where these facets intertwined, mediating access to the divine while also serving as its manifestation. The use of symbolism and the interpretation of veiled realities were essential aspects of knowledge acquisition during that time. The Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period were characterized by a profound epistemological approach that involved interpreting the natural world and events as symbols of a higher, divine reality. This symbolic thinking, often facilitated by the use of images, was a central element of the aesthetics of the time. Thinkers during this era believed in a concealed connection between the human realm and the divine, requiring interpretation and exegesis to unveil.

This concept of correspondence between the human and the universal macrocosm permeated various fields, including medicine, philosophy, metaphysics, magic, and religion. Symbolism played a pivotal role in understanding divine matters, as symbols were seen as a direct means of divine presence and embodiment. The influence of Plato, Middle Platonists, Neoplatonists, Hermetic thinkers, and philosophers like Nicholas of Cusa, Marsilio Ficino and Giordano Bruno was significant in shaping these ideas. The interpretation of art and nature as sources of divine hints required time and a departure from the apparent chaos of the material world to unveil the hidden harmony within the universe. This Hermetic and Neoplatonic approach emphasized a cosmic harmony originating from God. Myths, alchemical engravings, celestial observations, and dreams were all utilized as clues for understanding the divine, with a significant role assigned to imagination.

The concept of images as mirrors for the divine was a common theme in Christian aesthetics, emphasizing their power to connect the viewer with the invisible reality of God. However, it also carried the risk of being perceived as idolatry, sparking debates within the Church. The mirror metaphor was employed to reflect physical and mental dimensions of divine access.

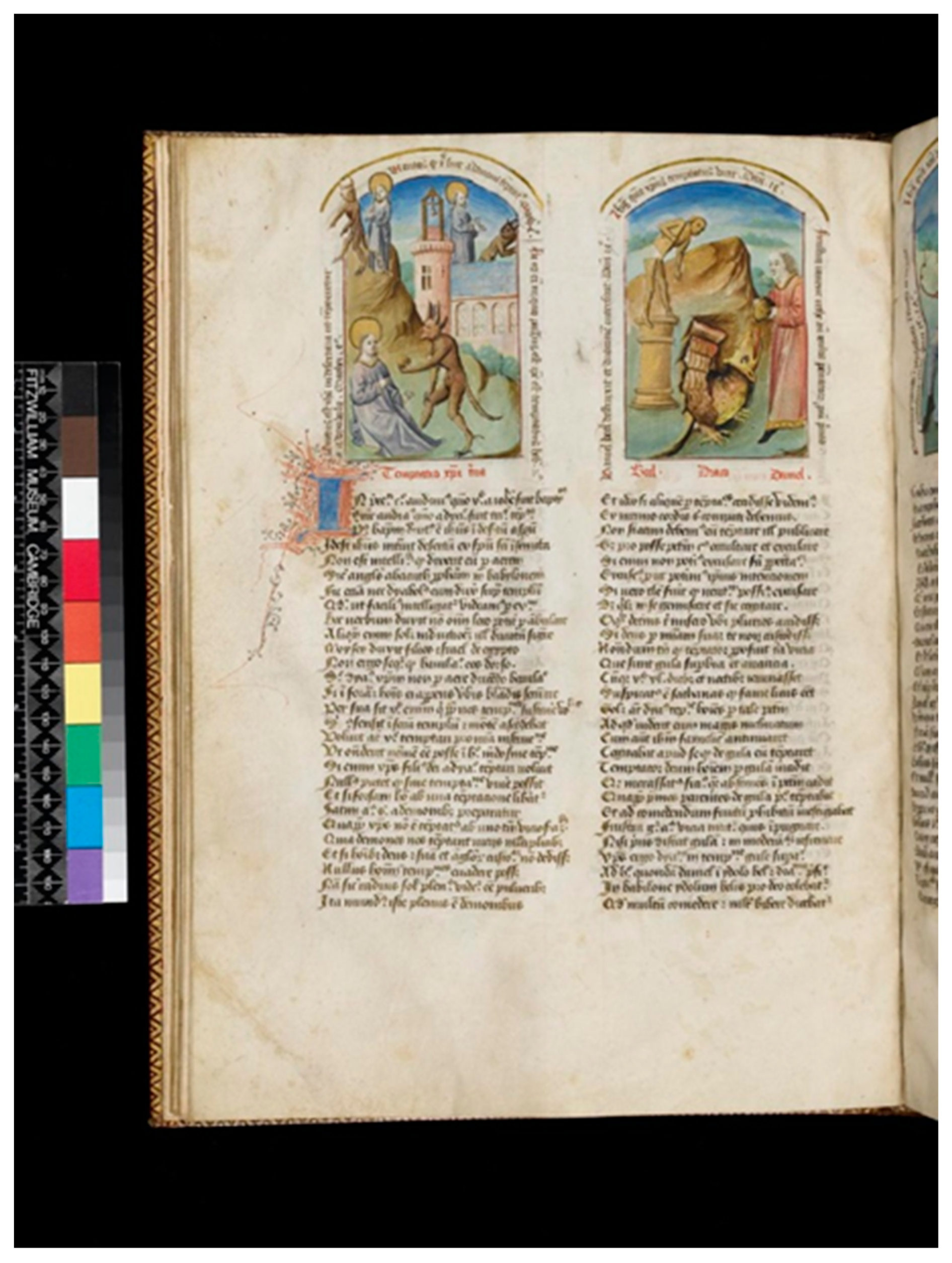

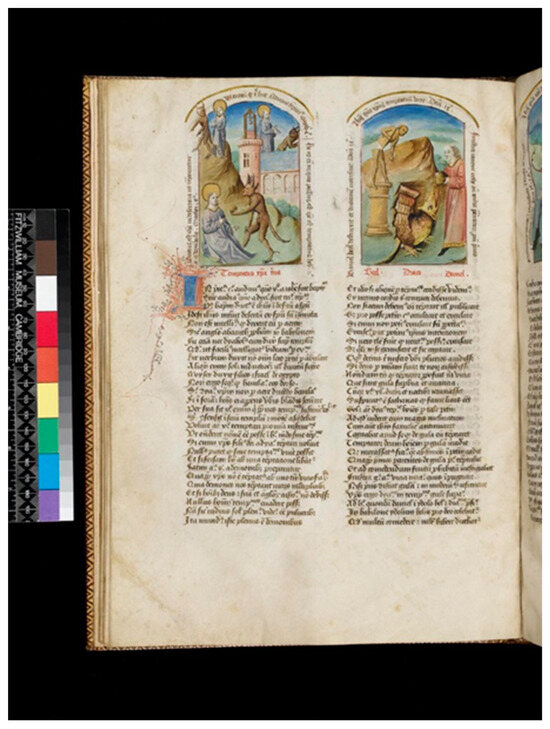

Lastly, the article explored speculum books (Figure 12), which served as mirrors containing comprehensive knowledge on various topics, offering pedagogic insights and analogies for understanding present events. The Speculum Humanae Salvationis intricately reflects humanity’s redemption through biblical typology, with Old Testament stories foreshadowing events in Christ’s life. Illustrated in manuscripts, these analogies provide profound insights into Christian exegesis and the visual symbolism of the era. These books were influential in the art world, with artists like Jan Van Eyck drawing inspiration from them.

Figure 12.

Anonymous, Speculum Humanae Salvationis, third quarter fifteenth century. The Fitzwilliam Museum MS 23, f. 14v, https://collection.beta.fitz.ms/id/object/169702 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

In summary, the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period were marked by a profound engagement with symbolism, images, and the concept of the image as a mirror for the divine, which influenced various fields and shaped the understanding of the relationship between the human and the divine.

Funding

This research was funded by NEXTGENERATIONEU and the Spanish Ministry of Universities, grant REQ2021.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | (Rilke 1961, p. 61). Original text: “Spiegel: noch nie hat man wissend beschrieben, /Was ihr in eurem Wesen Seid”. |

| 2 | And in another verse, (2 Cor. 3.18), it is said that ”we all, with unveiled face, beholding as in a mirror the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the same image”, in the New King James version. https://biblehub.com/nkjv/2_corinthians/3.htm (accessed on 27 January 2024). |

| 3 | City of God, XXII, 20, in (Augustine 2013, pp. 1171–1173). |

| 4 | De venatione sapientiae 39, 124, in (Cusa 1998, p. 1354). |

| 5 | De docta ignorantia I, 11, 32, in (Cusa 1990, p. 19). |

| 6 | Celestial hierarchy I, 3, in ([Pseudo] Dionysius the Areopagite 1899, pp. 3–4). |

| 7 | Convivio, II, 1, in (Dante Alighieri 1995, pp. 64–66). |

| 8 | Like other Neoplatonic theorists of art, Giovanni Bellori developed a concept of beauty that refines nature. He stated: “For this reason noble painters and sculptors, imitating that first maker, also form in their minds an example of higher beauty, and by contemplating that, they amend nature” (Bellori 2001, p. 57). |

| 9 | De pictura, II, 25, in (Alberti 2011, p. 89). |

| 10 | De somniorum interpretatione I, 1–2, in (Artemidorus 1975, pp. 14–18). |

| 11 | In The Republic, Plato presents various types of images, such as eikonas, which include figures in water or mirrors, as well as phantasmata: Republic 509e-510, in (Plato 1997, pp. 1130–1131; Plato 1894, p. 289). The concept of water and its reflections as an original mirror is supported by Gilbert Durand (Durand 1999, p. 98). Interestingly, in another cultural context, specifically within Maya culture, looking into a mirror and observing the surface of water are essentially the same (Rivera Dorado 2004, p. 91). In later pages of the same book, Plato criticizes images, equating the visual creations of painters with mirror images. He uses the cosmos as an example to illustrate that just as the reflected surfaces of a looking glass display external objects like the sun and the contents of the sky, the resulting image is merely a reproduction, lacking intrinsic reality (Republic 596d-e, in (Plato 1997, pp. 1200–1201)). |

| 12 | Timaeus 71a-d in (Plato 1997, p. 1272). |

| 13 | De imaginum, signorum et idearum compositione I, 1, 10, in (Bruno 1991, p. 31). This book outlines a theory of images, explaining how they are constructed in Bruno’s perspective. |

| 14 | De spiritu sancto XVIII, 45, in (Saint Basil the Great 1980, p. 72). |

| 15 | For Catholics, vision had pre-eminence among the five senses, while for Lutherans, audition possessed that privilege because the Holy Spirit used it as a vehicle (see González García 2015, p. 317). |

| 16 | De imaginum, signorum et idearum compositione I, 1, 7, in (Bruno 1991, p. 22). |

| 17 | “Hence, in order to avoid all the evils which may happen to the soul in this connection, which are its being hindered from soaring upward to God, or its using images in an unworthy and ignorant manner, or its being deceived by them through natural or supernatural means, all of which are things that we have touched upon above; and in order likewise to purify the rejoicing of the will in them and by means of them to lead the soul to God, for which reason the Church recommends their use”, in Subida del monte Carmelo 3, XXXVII, 2, in (St. John of the Cross 2000, p. 248). |

| 18 | De visione dei 4, 13, in (Cusa 1988, p. 685), and De visione dei 8, 32, in (Ibid, p. 694). |

| 19 | De amore V, 4, in (Ficino 1985, p. 90). |

| 20 | Theologia platonica, X, IV, 3, in (Ficino 2003, p. 149). |

| 21 | De radiis V, 4, in (Al-Kindi 2003, p. 35). |

| 22 | Corpus hermeticum, V, 1, in (Copenhaver 1992, p. 18). |

| 23 | Corpus hermeticum, I, 14, in (Ibid, p. 3). |

| 24 | Ennead IV, 3, 11, in (Plotinus 1984, pp. 71–73). This matter of the original and the copy is explored in another excerpt from the Enneads. When contemplating the influence of prayers, Plotinus rationalizes it through sympathy. The philosopher employs a metaphor: a lyre placed in front of another one resonates in sympathy if the other is being played at that very moment: Ennead IV, 4, 41, (Ibid, p. 265). It resembles a metaphor found in mirrors, albeit with a distinction; both lyres are identical, whereas in the image within a mirror there exists an original and multiple reflections, potentially limitless, devoid of the ontological significance attributed to the original archetype. |

| 25 | De visione dei Preamble, 3–4, in (Cusa 1988, pp. 680–682). |

| 26 | De visione dei 6, 19, in (Ibid, p. 688). |

| 27 | Theologia platonica, XII, 4, in (Ficino 2004, p. 45). |

| 28 | Theologia platonica, XVII, 2, in (Ficino 2006, pp. 9–11). |

| 29 | https://www.etymonline.com/word/speculate (accessed 31 January 2024) and in Spanish with more information about the Latin evolution: http://etimologias.dechile.net/?especular (accessed 31 January 2024). |

| 30 | Twenty years later, Albert Hauf i Valls increased the number of books to 400 (Hauf i Valls 2001, p. 186). Number of volumes rising to 420 in 2022 according to Melinda Nielsen (Nielsen 2022, p. 2). |

| 31 | As with other examples, the illuminations in the manuscripts enabled the illiterate to better comprehend the concept of Christian redemption presented in the book. This aligns with the idea put forth by Gregory the Great regarding the use of pictures to assist individuals in attaining salvation. For further insights, see secondary sources: Gertsman; & Rosenwein 2018, 99. Chazelle nuances part of this assumption about the use of images advocated by Gregory the Great (Chazelle 1990). |

References

- Alberti, Leon Battista. 2011. On Painting. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Kindi. 2003. De Radiis: Théorie des Arts Magiques. Paris: Allia. [Google Scholar]

- Artemidorus. 1975. The Interpretation of Dreams. Park Ridge: Noyes Press. [Google Scholar]

- Augustine. 2013. The City of God against the Pagans. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baltrusaitis, Jurgis. 1978. Le Miroir. Essai sur une Légende Scientifique. Paris: Aline Elmayan et du Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Basil the Great, Saint. 1980. On the Holy Spirit. New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beaujour, Michel. 1982. Speculum, Method, and Self-Portrayal: Some Epistemological Problems. In Mimesis, from Mirror to Method, Augustine to Descartes. Edited by John D. Lyons and Stephen J. Nichols, Jr. Hanover: Darmouth College Press, pp. 188–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bellori, Giovan Pietro. 2001. The Lives of the Modern Painters, Sculptors and Architects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Belting, Hans. 1994. Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, Giordano. 1991. On the Composition of Images, Signs & Ideas. New York: Willis, Locker & Owen. [Google Scholar]

- Calvin, John. 1994. Fragment of Institutes of the Christian Religion (1536–59). In Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art. Edited by Hans Belting. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 550–51. [Google Scholar]

- Camille, Michael. 1996. Gothic Art: Glorious Visions. New York: Harry N. Abrams. [Google Scholar]

- Cardon, Bert. 1996. Manuscripts of the Speculum Humanae Salvationis in the Southern Netherlands (c.1410–c.1470): A Contribution to the Study of the 15th Century Book Illumination and of the Function and Meaning of Historical Symbolism. Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallé, Mónica. 2008. La Sabiduría de la No-Dualidad. Una Reflexión Comparada Entre Nisargadatta y Heidegger. Barcelona: Kairós. [Google Scholar]

- Chazelle, Celia M. 1990. Pictures, books, and the illiterate: Pope Gregory I’s letters to Serenus of Marseilles. Word & Image 6: 138–53. [Google Scholar]

- Copenhaver, Brian P., ed. 1992. Hermetica. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan, Kathleen. 1992. Visual Polemics in the Ninth-Century Byzantine Psalters: Iconophile Imagery in Three Ninth-Century Byzantine Psalters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cusa, Nicholas of. 1988. Nicholas of Cusa’s Dialectical Mysticism. Minneapolis: The Arthur J. Banning Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cusa, Nicholas of. 1990. On Learned Ignorance. Minneapolis: The Arthur J. Banning Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cusa, Nicholas of. 1998. Nicholas of Cusa: Metaphysical Speculations. Minneapolis: The Arthur J. Banning Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dante Alighieri. 1995. Convivio. 2. Testo. Firenze: Casa Editrice Le Lettere. [Google Scholar]

- Durand, Gilbert. 1999. The Anthropological Structures of the Imaginary. Brisbane: Boombana Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins, James. 1996. The Object Stares Back: On the Nature of Seeing. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Favero, Paolo S. H. 2021. Image-Making-India. Visual Culture, Technology, Politics. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer Ventosa, Roger. 2021. Mágica Belleza. Ondara: Dilatando Mentes. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Ventosa, Roger. 2023. Imago Mundi. The Notion of Something as a Microcosm of the Macrocosm. De Medio Aevo 12: 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Ventosa, Roger. 2024. El saber de la sombra. In Mitos e Imágenes. Edited by Marta Piñol Lloret. Vitoria-Gasteiz: Sans Soleil, pp. 75–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ficino, Marsilio. 1985. Commentary on Plato’s Symposium on Love. Dallas: Spring Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ficino, Marsilio. 2003. Platonic Theology. Volume 3. Books IX–XI. Cambridge: The I Tatti Renaissance Library. London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ficino, Marsilio. 2004. Platonic Theology. Volume 4. Books XII–XIV. Cambridge: The I Tatti Renaissance Library. London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ficino, Marsilio. 2006. Platonic Theology. Volume 6. Books XVII–XVIII. Cambridge: The I Tatti Renaissance Library. London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- García Avilés, Alejandro. 2021. Imágenes Encantadas. Los Poderes de la Imagen en la Edad Media. Vitoria-Gasteiz: Sans Soleil Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Gertsman, Elina, and Barbara H. Rosenwein. 2018. 24—Günther Zainer, The Virgin Mary Overcoming a Devil, from Speculum Humanae Salvationis/Spiegel menschlicher Behältnis, c. 1473, Germany, Augsburg, hand-colored woodcut; 7.4 × 12.0 cm (2 15/16 × 4 3/4 inches). In The Middle Ages in 50 Objects. Edited by Elina Gertsman and Barbara H. Rosenwein. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 96–99. [Google Scholar]

- González García, Juan Luis. 2015. Imágenes Sagradas y Predicación Visual en el Siglo de oro. Madrid: Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Hauf i Valls, Albert. 2001. De l’Speculum humanae salvationis a l’Spill de Jaume Roig: Itinerary specular i figural. Estudis Romànics 23: 173–219. [Google Scholar]

- Kodera, Sergius. 2002. Narcissus, Divine Gazes and Bloody Mirror: The Concept of Matter in Ficino. In Marsilio Ficino: His Theology, His Philosophy, His Legacy. Edited by Michael J. B. Allen and Valery Rees. Leiden: Brill, pp. 285–306. [Google Scholar]

- Labriola, Albert C., and John W. Smeltz, eds. 2002. The Mirror of Human Salvation. An Edition of British Library Blockbook G. 11784. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mâle, Emile. 1984. Religious Art in France. The Thirteenth Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Melchior-Bonnet, Sabine. 2001. The Mirror: A History. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, W. J. T. 1984. What Is an Image? New Literary History 15: 503–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morphy, Howard. 1994. From Dull to Brilliant: The Aesthetics of Spiritual Power among the Yolngu. In Anthropology, Art and Aesthetics. Edited by Jeremy Coote and Anthony Shelton. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 181–208. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, Melinda. 2022. An Illustrated Speculum Humanae Salvationis. Green Collection Ms 000321. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski, Edward J. 2009. A Possible Source for the Triptych, Lunette, and Tondo Formats in Renaissance Paintings. Source: Notes in the History of Art 28: 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plato. 1894. Plato’s Republic. The Greek Text. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Plato. 1997. Complete Works. Indianapolis and Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Plotinus. 1984. Enneads. IV. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. London: William Heinemann Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- [Pseudo] Dionysius the Areopagite. 1899. The works of Dionysius the Areopagite. London: James Parker and co. [Google Scholar]

- Rilke, Rainer Maria. 1961. Sonnets to Orpheus. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera Dorado, Miguel. 2004. Espejos de poder. Un aspecto de la Civilización Maya. Madrid: Miraguano. [Google Scholar]

- Silber, Evelyn. 1980. The Reconstructed Toledo Speculum Humanae Salvationis: The Italian Connection in the Early Fourteenth Century. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 43: 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. John of the Cross. 2000. Ascent of Mount Carmel. Grand Rapids: Christian Classics Ethereal Library. [Google Scholar]

- Stoichita, Victor I. 1993. L’instauration du Tableau. Paris: Méridiens Klincksieck. [Google Scholar]

- Stoichita, Victor I. 1997. A Short History of the Shadow. London: Reaktion Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, Christopher. 1987. ’Latter-day’. Saints and the Image of Christ in the Ninth-century Byzantine Marginal Psalters. Revue des études byzantines 45: 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, Elliot R. 1994. Through A Speculum that Shines. Vision and Imagination in Medieval Jewish Mysticism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, Frances A. 1964. Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Zambelli, Paola. 2012. Astrology and Magic from the Medieval Latin and Islamic World to Renaissance Europe. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).