Abstract

This article examines the phenomenon of the so-called royal tamga signs issued on stone stelae in the Bosporan Kingdom in the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE. Tamgas were symbols commonly used by Eurasian nomads throughout the first millennium BCE. The appearance of tamgas in the northern shores of the Black Sea in the 2nd/1st BCE, followed by their adoption into the Greek epigraphic culture of the kingdom, represents an intriguing example of symbolic integration and another step in the formation of Bosporan culture. Research on cultural interactions between the inhabitants of the Bosporus has rarely focused on epigraphic material in its own right. Analyzing a small group of public stone slabs that feature tamgas, this article contributes to existing studies on numerous private funerary reliefs. Furthermore, the current work aims to incorporate several examples of stelae with royal tamga signs into the growing interest in syncretism, which is occurring in other epigraphic cultures of the Greco-Roman world. The case of the Bosporan Kingdom shows that such processes can also occur in places where no literate culture had previously been firmly established.

1. Introduction

Combined with a movement away from Hellenocentric studies, postcolonial approaches offer a new outlook on approaches to cultural and ethnic identities in the ancient world.1 The postcolonial view has resulted in greater attention on the so-called peripheries, i.e., areas that are distant from the center of Greek culture. Additionally, it has prompted questioning of dominant theories, such as Hellenization and acculturation, on the interactions between Greeks and non-Greeks (Bilde and Petersen 2008, pp. 9–12). The possibility of various forms of syncretism and cultural hybridization, as well as a challenge to the concept of a permanently shaped ethnos focusing on the importance of gradual “becoming” has formed as the subject of growing consideration.2

Despite appearing with some delay, these new approaches have also begun to gain application in research on the regions of the northern Black Sea. They are used in analyses of the influence of Greco-Roman culture on the local population and the development and functioning of multi-ethnic societies. Worth highlighting are changes in the approach to material culture from the northern shores of the Black Sea and its significance in assessing cultural influences. Attention has been focused on the difficulties in determining an individual’s ethnos solely based on artefacts, which are often more universal in nature, used in burial practices.3 Another interesting example of a different approach is the study of Greco-Scythian art from the northern shores of the Black Sea. By placing these beautifully decorated artefacts in a local context and reinterpreting the applied iconography, previous researchers have demonstrated their cross-cultural character, which was primarily influenced by social conditions (Meyer 2013).

Discussions about intermingling Greco-Roman with local cultures in the so-called peripheries extend beyond material culture and can encompass various aspects of life. “Global” phenomena, such as the spread of the Greek polis model and the associated specific lifestyles, art, religiosity, or diet, could lead to the development of distinct forms specific to a given region. Vlassopoulos describes such phenomena, referring to globalization and glocalization which are local syncretic forms of a globally occurring phenomenon (Vlassopoulos 2013, pp. 19–25).

The abovementioned trends in the study of cultural interaction on the northern shores of the Black Sea have, to a lesser extent, covered the issue of epigraphic culture. Therefore, the main goal of this article is to take a closer look at the small group of inscriptions and uninscribed stone stelae on which the so-called royal tamgas were placed. Tamga marks were symbols that the Eurasian nomads used. The widespread distribution of tamga marks on the northern shores of the Black Sea is associated with the migration of tribes such as the Siraces and Aorsi in the 2nd century BCE. With the rising position of the Sarmatians, the symbols found their way to the rich epigraphic culture of the Bosporan Kingdom, complementing the official image of rulers from the Tiberii Iulii dynasty. Attempting to locate the phenomenon of royal tamgas within the Bosporan epigraphic habit, linking them to the epigraphic curve, reflecting on the epigraphic mode of these public stone stelae, and presenting the significance of tamgas in the official image of local kings may supplement research on the numerous private Bosporan funerary reliefs, which also provide an excellent example of the development of local Bosporan culture.4

2. Studies on Epigraphic Cultures and the Origins of Their Glocalization

The case of the Bosporan Kingdom demonstrates the adaptation of Greek epigraphic habits with local cultural features. This was the case when an epigraphic culture based on Greek formats and conventions adopted many elements from the cultures of local non-Greek tribes and incoming steppe peoples.5

The introduction of the concept of epigraphic habit by MacMullen (1982), which referred to the Roman practice of creating commemorative inscriptions in stone, was a pivotal moment in the study of the role of epigraphy in socio-political life in antiquity. MacMullen examined this custom as it was practiced from the 1st century BCE to the early 3rd century CE. He noted that its peak popularity did not coincide with periods of Roman prosperity but occurred during the reign of Caracalla. In his work, MacMullen emphasized that stone inscriptions differed from other forms of documentation, such as papyri or ostraca. The analysis of this form revealed its significant symbolic importance for communities, especially for influential groups such as property owners and officials. MacMullen argued that symbolic rather than practical motivations shaped the changes in the popularity of this custom, pointing to the elusive sense of audience.

Despite some criticism, subsequent researchers continued MacMullen’s line of thought. They strived to identify specific factors that influenced the changing frequency of epigraphic use and determine what could shape the sense of audience.6 Initially, the researchers focused mainly on Latin epigraphy, where “imperial trends” were more easily discerned. In 1991, Alföldy (1991) wrote an influential essay that significantly impacted research on epigraphic culture. According to Alföldy, the epigraphic habit that MacMullen identified was not a spontaneous phenomenon but was intentionally established and promoted by the first Roman Emperor, Augustus. Alföldy argued that what MacMullen called a “habit” should instead be recognized as a full-fledged “culture” systematically promoted to confirm and strengthen social order in the Roman Empire. Woolf (1996) further developed the concept of epigraphic culture, suggesting that the Roman epigraphic habit was part of a broader trend toward personal monumentalization, a response to feelings of rootlessness and anxiety that resulted from increased social and geographical mobility in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. In equally significant works, Meyer (1990, 2011) noted that the rise and subsequent decline of Latin epigraphic production correlated with the desire for Roman citizenship and the personal prestige associated with elite membership. After the enactment of the Constitutio Antoniniana and the granting of Roman citizenship to all, setting inscriptions became less attractive.

Over time, the term epigraphic culture has gained significance, and it is often used interchangeably with epigraphic habit to describe commemorative activities such as the production of inscriptions on stone. Nevertheless, a clear distinction between the two terms occurs only at times. Epigraphic culture typically encompasses a broader range of practices related to epigraphy beyond stone monuments and may include various writing practices specific to a particular community. In the context of research into Greek epigraphic culture—or, as Bodel noted, epigraphic cultures—one cannot easily point to any overarching trend in the Greek world (Bodel 2001, pp. 6–15). Naturally, in the eastern Mediterranean, common phenomena such as the emergence or decline of democracies and euergetism influenced the production of inscriptions. However, the decentralized nature of the world of Greek poleis resulted in local solid trends, as evidenced by recent studies focusing on the forms of epigraphic curves for individual regions, including the northern shores of the Black Sea.7

As stated earlier, this study aims to present a specific aspect of dualism in the epigraphy of the Bosporan Kingdom. This is illustrated by the example of the so-called tamga signs, which can undoubtedly be viewed as a local, idiosyncratic phenomenon. However, worth considering first is the context of the presence of such local features in the global phenomenon of creating stone inscriptions in antiquity. Many languages other than Greek and Latin found daily use in the Roman Empire. Several appeared in writing, while others were only spoken. As a result, in most regions of the eastern Mediterranean basin, where non-Greek forms of statehood previously existed (for example, in Egypt and Phoenicia), non-Greek epigraphic cultures emerged, leaving numerous inscriptions in local languages such as Aramaic, Phoenician, Hebrew, hieroglyphs, and others. These inscriptions belonged to a broader literate culture that usually gave way to Greek writing or disappeared entirely.8

Moreover, the emergence of multilingual inscriptions, often in languages beyond Latin and Greek, became a widespread phenomenon. For example, inscriptions from Palmyra were recorded in Latin, Greek, and the local Aramaic dialect. Such inscriptions vividly illustrate the cross-cultural processes that occur in a given territory (Parca 2001, pp. 71–72). The concept applies to official inscriptions but perhaps even more so to inscriptions that “ordinary” people created. In these inscriptions, as Parca (2001, pp. 64–68) noted, the evolution of language and the emergence of new “local” formulations are evident.

The presence of another language in an inscription strongly suggests that its purpose was to reach a diverse audience and that it was erected at the initiative of individuals or groups of mixed identities. However, besides using bilingual inscriptions, individuals of different ethnicities also found it natural to create inscriptions exclusively in Greek and Latin. Several indicators can help identify merged features or the development of local trends. In addition to the aforementioned linguistic modifications, one often-cited factor includes onomastics, which, in itself, does not determine but may suggest ethnic background. However, this is merely an indication because, as examples from the northern shores of the Black Sea demonstrate, locally used names could result from the prevailing fashion, mixed marriages, or the fact that the bearers of the names did not necessarily feel the need to identify with one specific ethnic group.9

Therefore, when studying the local epigraphic culture, one can draw significant conclusions by analyzing the iconography and form of the stelae and the context of their erection. Certain stelae contained integral elements, such as signs or symbols indicating affiliation with a specific ethnic or social group. For example, menorahs were placed in several inscriptions from the Levant region alongside epitaphs or dedications written in Greek, clearly indicating the practitioner’s adherence to Judaism (For example, IJO Syr. 7; 10). However, it is worth emphasizing that this phenomenon was not limited to a specific region. Rather, it was applied to individuals who travelled and influenced epigraphic cultures in various parts of the Greco-Roman world. Examples include menorah epitaphs and bilingual texts in Greek and Hebrew from the Bosporan Kingdom.10

This section concludes with a new concept called the epigraphic mode proposed by Bodel. According to this concept, factors such as the form of the inscription, its interaction with the environment, the precision and technique of execution, and the employed iconography can determine whether a particular text is considered more or less epigraphic. In presenting his considerations, Bodel (2023, pp. 14–34) focuses on Latin inscriptions. He demonstrates that in certain cases, a painted text could exhibit a high level of the epigraphic mode, for example, if it incorporated elements typically reserved for stone inscriptions such as a painted border and text written in capital letters, as seen in popular tabulae ansatae or certain inscriptions from Pompeii. This approach is particularly interesting, as it allows for us to include the epigraphic mode concerning stone stelae from the Bosporan region with discussion on the so-called royal tamgas, whose form, in certain aspects, resembles typical inscriptions. Consequently, one may question why this form of communication was chosen and what role it may have played in the self-presentation of Bosporan rulers in the public sphere.

3. Tamga Signs and Their Spread across the Northern Shores of the Black Sea

As mentioned in the previous section, glocalization within the epigraphic cultures of Mediterranean regions with well-established writing traditions, such as the Levant, Egypt, and Asia Minor, was a frequently encountered phenomenon. However, local populations lacking the literary tradition and epigraphic culture of one of the regions could also influence the development of an epigraphic habit. This occurred in epigraphic material from the northern shores of the Black Sea, particularly in those produced in the Bosporan Kingdom, where, under the influence of Eurasian nomads (mostly Sarmatians), numerous so-called tamga marks began to appear.

Tamga marks are symbols used by several peoples of the Great Steppe from ancient times to the modern era. Initially, the marks appeared across the vast areas of Central Asia. Over time, as the nomadic populations moved, the marks spread to neighboring regions. The word “tamga” is of Turkish origin and was not used in antiquity. Therefore, the symbols that the Sarmatians spread in the northern Black Sea regions from the 2nd/1st centuries BCE are often described as “Sarmatian signs” (Сарматские знаки), “tamga-like signs” (Тамгooбразные знаки), or simply “tamga signs” (Знаки-tамги).11

There is an ongoing discussion about the original use of these symbols. At an early stage, long before they reached the Black Sea, the symbols were used in various ways; for example, in Central Asia, they were placed on rocks as petroglyphs (Yatsenko 2001, pp. 105–6). One cannot rule out the initial religious or magical significance of the symbols. Nonetheless, it should be emphasized that the application of these symbols evolved and differed depending on the region and period (Yatsenko 2001, p. 27). Over time, tamga signs associated with the Saka people permeated the Iranian world. The earliest signs from Khorezm probably date back to the 6th century BCE. Then, they reached Sogdiana and later Bactria (Weinberg and Novgorodova 1976). Boardman (1998) notes that certain signs found on bricks or seals in Persepolis, Pasargadae, and Anatolia resemble those on the northern shores of the Black Sea. These signs were used during the reign of the Achaemenids, Parthians, and Sasanians.

However, the signs used on the northern shores of the Black Sea from the 1st century BCE to the 3rd century CE likely served to mark ownership and indicate the clan affiliation of the owner (Yatsenko 2001, pp. 22–23; Solomonik 1959, pp. 34–46). Tamga signs penetrated and spread to the territory of the Bosporan Kingdom through the Sarmatian tribes, which gradually moved westward from Central Asia. Due to limited archaeological sources, there is a debate on the scale and course of this Sarmatian migration.12 However, the appearance of tamgas in the Black Sea region should be linked to events in China and Central Asia, where peoples such as the Xiongnu and Yuezhi conflicted.13 The conflict initiated population movements that contributed to the fall of the Bactrian kingdom in the 2nd century BCE. Subsequently, this directly impacted the movement of Sarmatian tribes, such as the Siraces and Aorsi, toward the Lower Don region in the 2nd/1st century BCE. The elite of these tribes used the signs, which, with further migration, spread to the northern shores of the Black Sea.

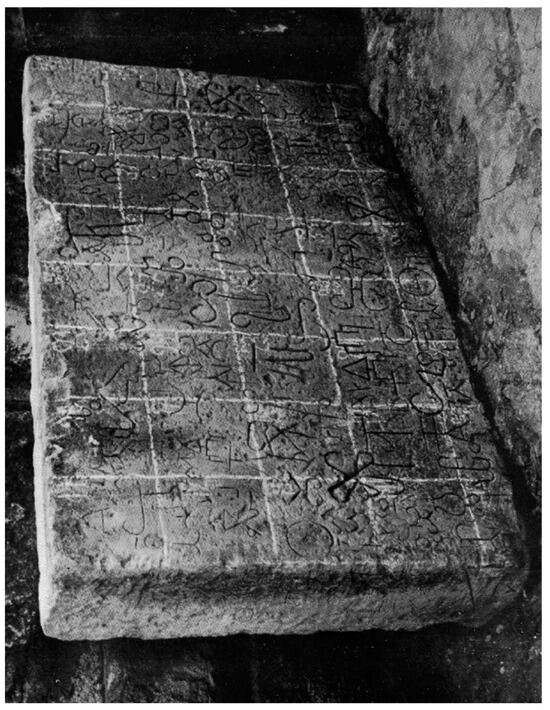

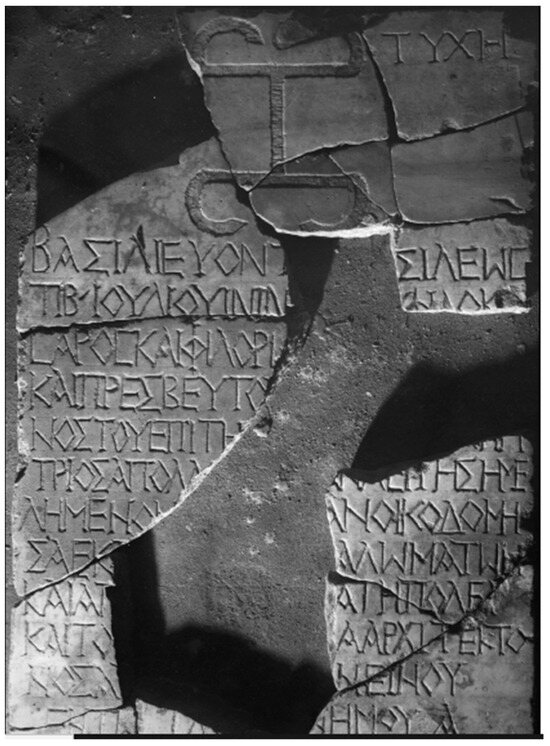

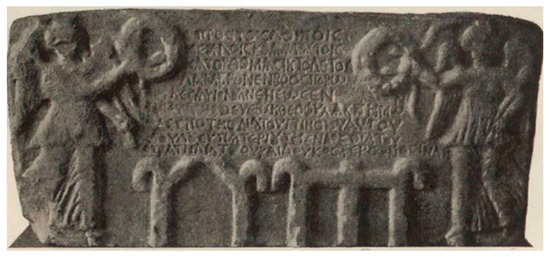

Non-Greek elites placed the Sarmatian tamgas on various objects such as jewelry, weapons, and stone sculptures and inscriptions. However, it should be emphasized that in most cases, tamgas were later additions to the artifacts.14 The most common reasons for placing tamgas were to indicate the ownership of an item or to mark presence in a particular location. Religious matters were likely less significant. A prime example is the stone lions from Olbia, covered with hundreds of various signs, made much later than the lions were constructed. The stone lions from Olbia are a case of the so-called tamga encyclopedias, i.e., groupings of several signs together (Solomonik 1959, Figures 41 and 42, pp. 87–97). Another excellent example of the tamga encyclopedias, the slab from Panticapaeum, demonstrates the diversity of Sarmatian tamgas. Additionally, the slab is the best example to illustrate the variety of symbols used by Sarmatian elites in the areas of the northern Black Sea in antiquity (Dračuk 1975, plates XXXII–XXXVI; Solomonik 1959, Figure 47, pp. 103–4). The slab, similar to the stone lions from Olbia, contains examples of signs from diverse locations across the northern Black Sea coast, indicating the extensive mobility of its owners (see Figure 1). Encyclopedias, however, were not employed to mark ownership but were probably used to confirm presence at a meeting, to confirm an alliance, or perhaps to mark territory (Yatsenko 2001, pp. 80–83). There are several possibilities for categorizing tamga signs. However, the so-called royal tamgas are most important for this work as they penetrated the epigraphic culture of the Bosporan Kingdom, serving as integral parts of public stelae with and without Greek inscriptions.

Figure 1.

The so-called encyclopedia of tamga signs from Panticapaeum. Roman times. After (Dračuk 1975, plate XXXII).

The so-called royal tamgas can be linked to specific rulers (Yatsenko 2001, pp. 45–60; Dračuk 1975, pp. 97–98). Such signs, like those of less significant elite members, could be placed on jewelry, weapons, or stone stelae that were made earlier. However, the importance of the signs lies in the fact that, in certain cases, one can determine that they were created simultaneously with the objects on which they are found. Therefore, a sign becomes an integral part of its corresponding object from the beginning. In forming the epigraphic culture of the Bosporus, the royal tamgas of the Tiberii Iulii family form the essential group among these types of signs. The royal tamgas appeared from about the mid-2nd century CE to the first half of the 3rd century CE. They are discussed in detail later in this article.

Before the creation of stone stelae with the royal tamgas came the minting of coins with the tamgas of individual rulers. The oldest examples are from Queen Dynamis and King Aspurgus who ruled over the Bosporus at the turn of the 1st century BCE and 1st century CE.15 It was a tumultuous time characterized by upheavals and internal conflicts.16 During this period, the Sarmatian tribes gained an advantage, leading to the appearance of these signs (Halamus 2017, pp. 163–64).

One should emphasize that these tamgas began to appear at the beginning of the formation of a new ruling dynasty. Aspurgus was the dynasty’s first representative and likely the first to adopt the Roman name Tiberius Iulius Aspurgus, which is typical for a Roman client. From then on, for the next three centuries, the rulers of the Bosporus adopted tria nomina, starting with Tiberius Iulius and ending with the cognomen—the local name of the ruler.17 Tamga signs on Bosporan coins appear infrequently, and later, Aspurgus’ successors used traditional monograms. Another example of someone placing a tamga on a coin, although outside the Bosporus, occurred with the coins of Sarmatian kings Pharzoios and Inensimes, coins which were minted in Olbia in the second half of the 1st century CE. One of the coins was minted by Pharzoios (see Figure 2) whose sign is carried in the claws of an eagle—a reference to the local Olbian iconography (Tokhtas’ev 2013, pp. 568–69).

Figure 2.

(Not to scale) stater of King Pharzoios with an eagle holding a tamga sign. Struck ca. 50–75 CE, AV Stater, 8.28 g, 18 mm. Auction XIX Day 1, 26 March 2020, Lot 86. With kind permission of Roma Numismatic Limited.

There is a fundamental difference between tamga signs used for marking territory, for indicating participation in a clan assembly, for marking clan leaders, or simply for indicating presence, and tamgas created on coins and inscriptions by rulers. When a coin or an inscription was created, such a sign acquired an additional symbolic meaning: it transformed into an element of the ruler’s title. This sign, placed on coins or stone stelae, ceased to be solely a symbol aimed at other Sarmatians who used them. Its use as an integral part of elements (coins or inscriptions) typical for Greek cities offered the sign a more universal character, directing it to a broader audience.

4. Stelae with Royal Tamga Signs of the Tiberii Iulii Dynasty from the Bosporus

The previous section, together with the next section, provides a detailed analysis of the role and significance of royal tamgas in the Bosporan Kingdom. The Tiberii Iulii dynasty began its reign over the kingdom toward the end of the 1st century BCE. The dynasty traced its roots back to Mithridates Eupator, who, at the end of the 2nd century BC and after the death of the last of the Spartocids, took control of the Bosporus. Both his granddaughter Dynamis and Aspurgus who ruled after Dynamis used tamgas, although sparingly (see Notes 16 and 18). A limited collection of stone slabs bears royal tamgas as an integral part of the objects. These symbols can be divided into two groups: those with accompanying Greek inscriptions and those solely featuring the royal tamga (uninscribed).18 A century after king Tiberius Iulius Aspurgus and precisely during the reign of King Tiberius Julius Rhoemetalces (131–153 CE), these stone stelae adorned with royal signs began to appear. This practice continued with subsequent monarchs until the 230s CE. Individual rulers used these symbols in their propaganda. However, it is plausible that the symbols also resonated with a broader group of individuals, including family (clan) members and the king’s inner circle.

Compared to other tamgas, these symbols are noteworthy for their complexity. The base of an individual symbol features an “inverted trident,” with the upper portion potentially including one or two additional marks. The dominant interpretation suggests that the lower part of tamga was a shared feature distinctive of the Tiberii Iulii royal lineage, while the upper elements derived from the maternal side of the sovereign or another dynasty member (Yatsenko 2001, p. 46). According to Dračuk (1975, p. 65), the lower part of the symbol (inverted trident) could be associated with Poseidon, reflecting attempts in the propaganda of Bosporan rulers to trace their lineage back to this deity. However, Yatsenko correctly observed that tamgas in this form were present in earlier times in Central Asia, thereby dismissing a connection to Poseidon (Yatsenko 2001, pp. 50–51). Nevertheless, despite arising from the traditions of the Iranian steppe peoples, these symbols represent an aspect of the culture that flourished on the Bosporus. The royal symbols of the Tiberii Iulii are found exclusively within the kingdom’s territory or on artefacts directly linked to its rulers.

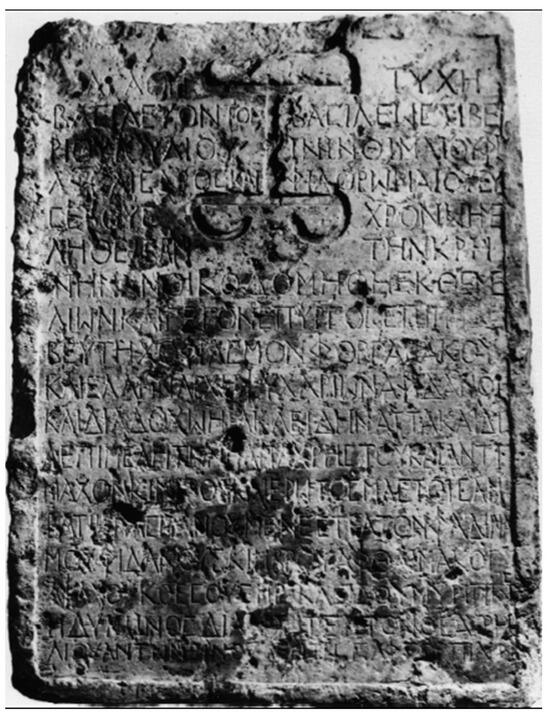

Stone slabs with royal tamgas were discovered in several locations of the Bosporan Kingdom. Almost all examples, except for two from Panticapaeum (Solomonik 1959, Figures 2 and 5, pp. 50–52), come from the eastern (Asiatic) part of the kingdom, with the majority originating from Tanais (CIRB 1237; 1241; 1248; 1249; 1250; 1251; Böttger et al. 2002). Other findings originate from Hermonassa (CIRB 1053; Solomonik 1959, Figures 3 and 4, pp. 51–52), Phanagoria (Kuznetsov 2008), and Khutor Krasnaya Batereya in the Kuban River basin, about 65 km east of Phanagoria (Solomonik 1959, Figure 6, p. 54). As previously mentioned, stone stelae with royal tamgas can be divided into two main groups: those with accompanying Greek inscriptions and those with just the sign (uninscribed). Almost all texts that accompany royal symbols are building inscriptions, describing the construction or repair of walls, towers, and other structures. They can also be partially considered honorific, typically with the aim of presenting influential people and their activities for the city. The inscription from Hermonassa, dated 208 CE, informs about the construction of a building by a certain Herakas, son of Pontikos, the chief translator of the Alans. It bears the mark of Sauromates II (Figure 3 = CIRB 1053). Other building inscriptions come from Tanais and bear the marks of Eupator (Figure 4 = CIRB 1241), Rhescuporis III (Figure 5 = CIRB 1248), and Ininthimaeus (Figure 6 = CIRB 1249 and Figure 7 = CIRB 1250). It is worth mentioning another lost inscription from Tanais, dated 193 CE and presented by Zenon, son of Zenon—the royal envoy to the city. On the inscription, according to the surviving drawing, a dedication text to Zeus, Ares, and Aphrodite was present (CIRB 1237 = Solomonik 1959, Figure 12, p. 59). Besides the dedication, the inscription also has honorific features, as it celebrates the victories of King Sauromates II over the Syraci, Scythians, and pirates, enabling navigation through the Black Sea to Pontus and Bithynia. In the lower left corner, a small tamga of the ruler was also present on the stone.

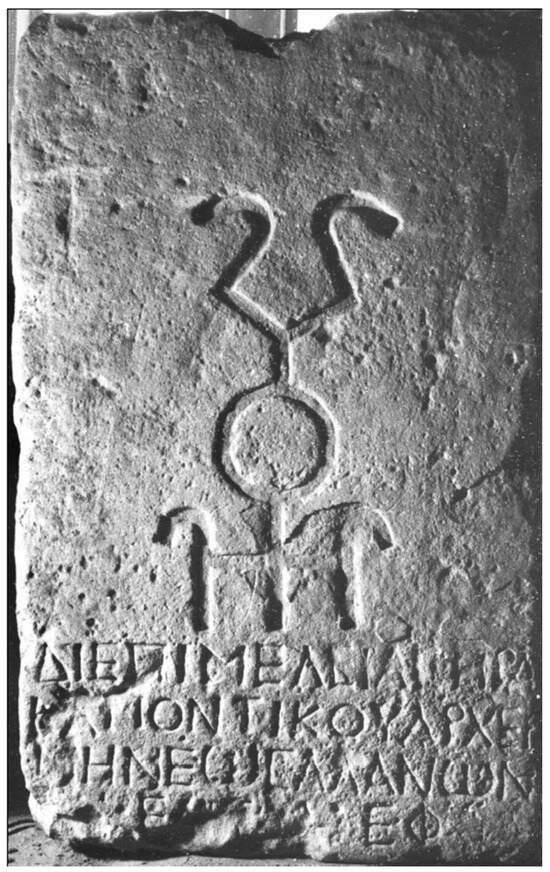

Figure 3.

Building inscription with royal tamga of King Tiberius Iulius Sauromates II, Hermonassa, 208 CE. CIRB-album 1053.

Figure 4.

Building inscription with royal tamga of King Tiberius Iulius Eupator, Tanais, 163 CE. CIRB-album 1241.

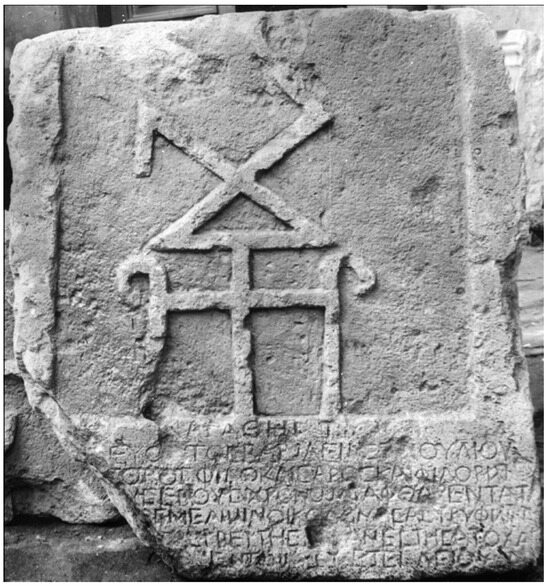

Figure 5.

Building inscription with royal tamga of King Tiberius Iulius Rhescuporis III, Tanais, 210–227 CE. CIRB-album 1248.

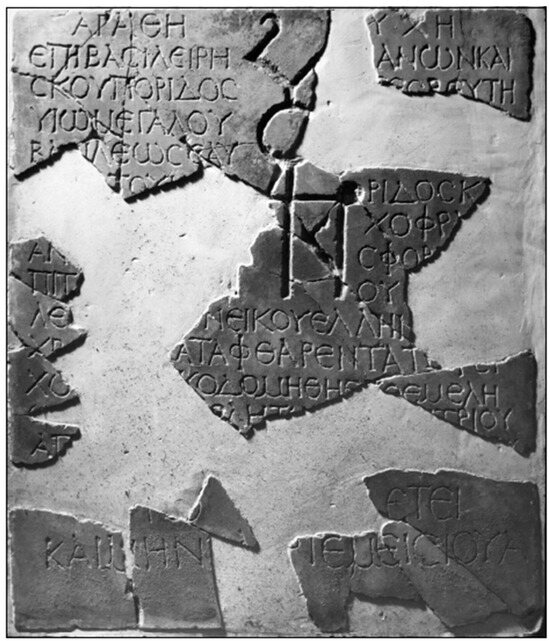

Figure 6.

Building Inscription with royal tamga of King Tiberius Iulius Ininthimaeus, Tanais, 236 CE. CIRB-album 1249.

Figure 7.

Building inscription with royal tamga of King Tiberius Iulius Ininthimaeus, Tanais, 236 CE. CIRB-album 1250.

The function of the royal sign accompanying the Greek inscription is difficult to determine definitively. One possibility is that it could have been used as an alternative to the king’s titles. For example, the building inscription from Hermonassa does not reference the ruler in the text. In this case, according to an interesting interpretation by Shkorpil, the royal sign could have acted as an equivalent to the standard formula “βασιλεύοντος βασιλέως Τιβερίου Ἰουλίου Σαυρομάτου φιλοκαίσαρος καὶ φιλορωμαίου, εὐσεβοῦς,” which can be translated as “During the reign of King Tiberius Iulius Sauromates, pious friend of Caesar and friend of Romans” (Shkorpil 1910, pp. 32–34). However, on other inscriptions, despite the inclusion of the sign in the text, references to the rulers’ titles are present. These include both elaborate “pro-Roman” formulas and single names of rulers (CIRB 1248; 1251), which make finding a uniform pattern difficult.

The royal tamga placed on the inscription could but did not necessarily have to serve as a substitute in the ruler’s titulature. Placed on the stela along with the text, it could increase the audience’s reach and afford certain monumental features to the entire object. Two identical building inscriptions from Tanais that mention King Rhescuporis III (211–227 CE) are interesting examples supporting this thesis. The text informs about the repair of walls and describes the king’s representative in Tanais and the chief of Aspurgians. On one of the stelae, which is larger and made of marble, the inscription appears along with the sign (CIRB 1248 = Figure 5), and on the other, which is smaller and made of limestone, only text is present (CIRB 1246). It is possible that the copy with the sign was placed in a more exposed manner, with the aim of reaching a larger audience.

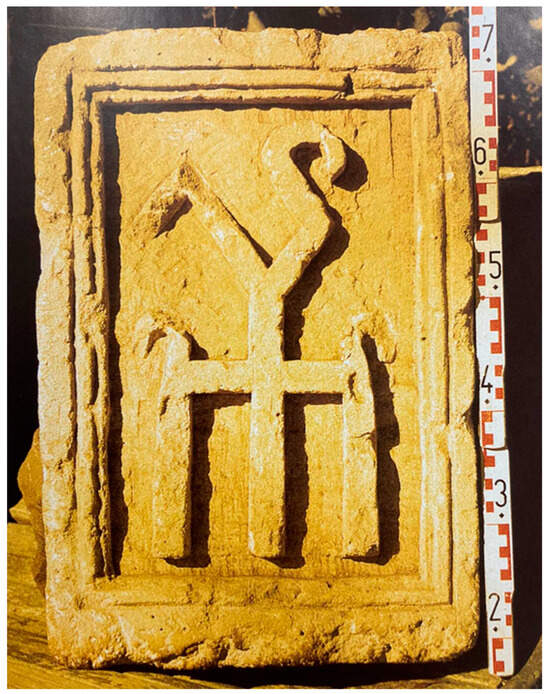

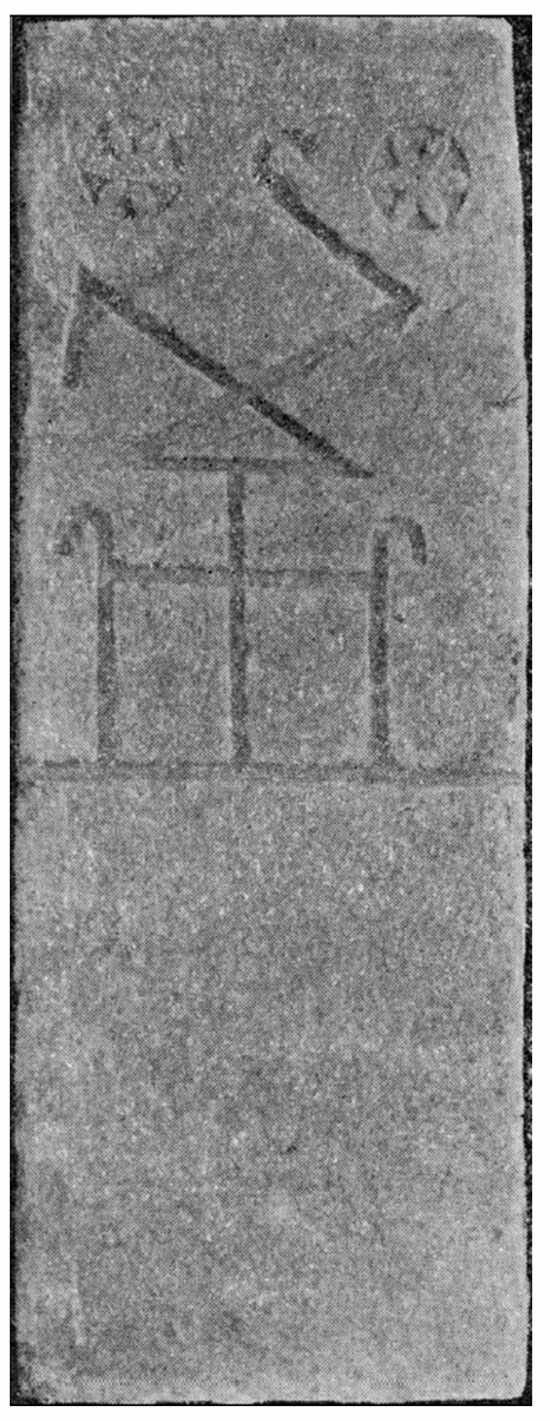

However, uninscribed stone slabs bearing the royal signs are a slightly different case. The first category includes stelae carved or in the form of relief without additional elements except for possible framing or decorations. These stones are most likely associated with the construction activity that the Bosporan kings initiated, and the sign itself also played its role in the official propaganda of the ruler. In this work, I include five examples, which, due to the piety of execution and sizes, indicate a deliberate placement on the stone slab rather than a random engraving. The earliest example is the sign of King Rhoemetalces found in Tanais in a relief form (Figure 8). The next three are carved signs of King Eupator: the first one is lost, and we have only a drawing (Solomonik 1959, Figure 6, p. 54); the second was issued on the reverse side of an epitaph from Panticapaeum (CIRB 738 = Figure 9), the third is now in Kerch, although its provenance is uncertain (Solomonik 1959, Figure 5, p. 53). The last example in this subcategory is the carved sign of Sauromates II from Phanagoria (Kuznetsov 2008 = Figure 10).

Figure 8.

Stela with royal tamga of King Tiberius Iulius Rhoemetalces, Tanais, 131–154 CE. (Böttger et al. 2002, p. 75).

Figure 9.

Stela with royal tamga of King Tiberius Iulius Eupator, Panticapaeum, 154–173 CE. CIRB-album 738.

Figure 10.

Stela with royal tamga of King Tiberius Iulius Sauromates II, Phanagoria, 173–211. (Kuznetsov 2008, p. 48).

The second subcategory belongs only to two examples of uninscribed slabs with royal signs from Hermonassa (Taman), which are presented along with Victoria figures holding wreaths above them. One of these slabs can have a connection to Tiberius Iulius Eupator (Solomonik 1959, Figure 3, pp. 51–52 = Figure 11), while the identification of the second is problematic due to the removal of the top part of the signs and their replacement with an inscription dated to the 5th/6th centuries CE (Solomonik 1959, Figure 4, pp. 52–53 = Figure 12). Interestingly, on this slab, two signs appear next to each other, with the base of one differing from the typical Tiberii Iulii “inverted trident.” This sign has only two “legs,” which may indicate that it possibly belonged to a relative of the ruler or his son (Treister 2011, pp. 314–15).19 The figure of Victoria/Nike was present in the iconography of the Bosporus even during the time of Asander (second half of the 1st century BCE)20 and later during the reign of the Tiberii Iulii dynasty. An interesting example is the relief from Panticapaeum, where Victoria hovers with a wreath over the figure of the man—perhaps a ruler (Treister 2011, pp. 323–25). Therefore, these slabs should instead be associated with honorific activity and may refer to military victories that the Bosporan kings achieved, as in the case of the earlier-mentioned dedication with the sign of Sauromates II.

Figure 11.

Stela with royal tamga of King Tiberius Iulius Eupator, accompanied by Victoria, Hermonassa, 154–173 CE. (Solomonik 1959, Figure 3).

Figure 12.

Stela with two unidentified royal tamgas, accompanied by Victoria, Hermonassa, 2nd century CE. (Solomonik 1959, Figure 4).

As previously noted, it is still unresolved whether the so-called royal tamgas were used as signs identifying only one ruler or if a broader group of individuals could use them. For example, Zavoikina (2003) considered the placement of these signs on stone slabs to be a local custom from Tanais. He connected the practice to the activity of local dominant clans, which is also visible on numerous lists of names (Zavoikina 2003).21 Moreover, this form of syncretism would undoubtedly match the ethnic diversity in Tanais, which was the most Sarmatized center of the kingdom (Halamus 2017, pp. 162–63). Nevertheless, Yatsenko (2005, pp. 414–17) and Treister rightly rejected this interpretation, noting several examples of royal signs issued on stone in other parts of the kingdom mentioned earlier.

The firm connection between this phenomenon and central authority also allows for the appearance of characteristic belt buckles shaped as royal signs and made of bronze and gold (Figure 13). Gold buckles made of thin foil found use in burials, while those made of bronze most likely served as gifts from the rulers of the kingdom to their closest commanders. Treister (2011) suggests that the Roman Empire influenced this practice, as similar decorative belt elements appeared in Germania and Raetia. Among the signs visible on bronze buckles, two are attributable to the kings Rhoimetalces II and Eupator, whose signs we know from stone slabs. The rest could belong to other members of the royal elite or to rulers who cannot be identified. Two signs were made next to each other on one of the buckles, which may correspond to one of the honorific stone slabs from Hermonassa (Treister 2011, pp. 326–27).

Figure 13.

Bronze belt buckle with royal tamga of King Tiberius Iulius Eupator, 154–173 CE. (Treister 2011, Figure 2.1).

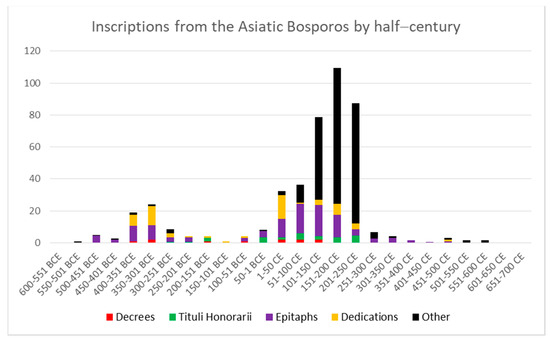

Buckles and belt endings with tamgas most likely originated in Panticapaeum. From there, they spread throughout the kingdom and beyond. As a result, the signs were present in the vast consciousness of the Bosporan society. Nonetheless, one should note that royal signs on stone slabs, both with inscriptions and without, almost exclusively appear in the territory of the so-called Asiatic Bosporus, which possibly relates to the aforementioned higher level of Sarmatization of this part of the kingdom. Of the inscriptions outlined earlier that appear with the royal sign, they were not issued directly by the ruler but instead by the kingdom’s elite members. Therefore, both the sign and the formulas with the rulers’ titulature, predominantly found in Bosporan public texts, fit into a broader policy of self-presentation of the kingdom’s ruling elite. Royal tamgas were universal symbols of royal power, which the Bosporans and the steppe population surrounding the Bosporan centers recognized.

5. Epigraphic Curve, Epigraphic Mode, and the Representation of the Bosporan Rulers

It was likely not coincidental that a new type of royal tamgas appeared during the reign of Tiberius Julius Rhoemetalces. As it has been observed, the use of tamgas in royal propaganda in the Bosporus occurred together with internal transformations within the kingdom (Yatsenko 2001, pp. 45–46). This may have been the case with the aforementioned signs of Aspurgus and Dynamis, as well as those that appeared sporadically from the second half of the 3rd century CE (Dračuk 1975, pp. 63–64). The emergence of the Tiberii Iulii family’s signs could be attributable to changes on the throne following the death of Tiberius Julius Cotys II around 132/3 CE. In his Periplus of the Pontic Sea, Arrian (Peripl. 17) informs Hadrian about the Bosporan Kingdom in light of the potential need for an expedition related to Cotys II’s death. A brief mention in Historia Augusta (3.9.8) also speaks of a dispute in the Bosporus and the eventual granting of the kingdom to Rhoemetalces. However, no expedition was necessary, as the kingdom remained loyal to Rome. Arrian further notes that the Bosporans continued to fulfil their duties, with a detachment from the kingdom fighting against the Alans in Cappadocia in 136 CE (Arr. Alan. 3). Additionally, in an inscription dated to 133 CE, Rhoemetalces honors Hadrian, calling him his ktistes (CIRB 47).

These brief mentions may indicate temporary tension associated with the power transition and suggest that Rhoemetalces came from a different branch of the Tiberii Iulii family. Seeking new forms and mediums for self-presentation, the new ruler might have expanded the use of the royal tamga beyond jewelry, coins, and belt buckles to stone stelae resembling inscriptions, which played a significant role in the public space of the kingdom at the time.

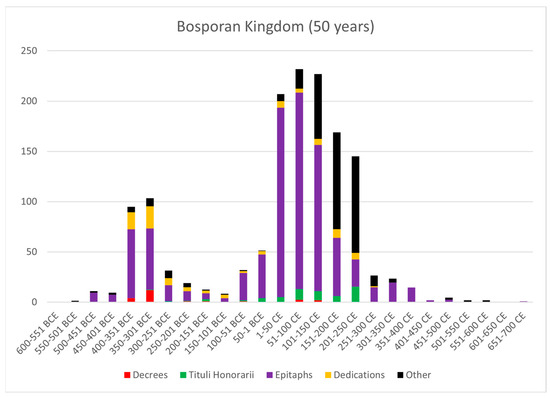

A connection may exist between the occurrence of royal tamga signs between the realms of Rhoemetalces and Ininthimaeus (131–238 CE) and the epigraphic curve of the Bosporan Kingdom.22 To highlight the integration of royal signs into the Bosporan epigraphic habit, one must consider two aspects. First, epitaphs were the predominant category of inscriptions during the Tiberii Iulii dynasty. Although the funerary inscriptions were mostly dated through palaeography, it is rather certain that their surprising popularity surged in the second half of the 1st century CE. The number of epitaphs remained high in subsequent decades (see Figure 14).23 Predominantly originating from Panticapaeum, these inscriptions were typically laconic but almost always featured accompanying reliefs depicting the kingdom’s inhabitants. Many of them portray riders and local warriors, which, among other things, led Kreuz (2012, see Footnote 5) to recognize the inscriptions as a local Bosporan phenomenon. Over time, the trend of erecting inscriptions reached the Asiatic part of the kingdom, where, from the early 2nd century CE, alongside frequent epitaphs, lists of names (mostly of thiasoi) and building inscriptions began to predominate (see Figure 15).

Figure 14.

Chart presenting epigraphic curve in the Bosporan Kingdom (1432 texts). Author: M. Halamus.

Figure 15.

Chart presenting epigraphic curve in the Asiatic part of the Bosporan Kingdom (444 texts). Author: M. Halamus.

Thus, the introduction of the first royal signs on stone slabs coincided with the peak popularity of inscriptions in the Bosporan Kingdom. With the potential of this communication form being recognized, a stone stela with a royal tamga served as a clear message for both “epigraphically literate” Bosporans and the surrounding Sarmatians who were familiar with the symbols. As stated earlier, most of the stone slabs had a building character, matching the trend in the Asiatic part of the kingdom, and included uninscribed slabs, which were also thought to refer to typical stone inscriptions in form. Therefore, in my opinion, royal tamgas appear on stone slabs (both epigraphic and uninscribed) associated with building activities and military victories because these were the areas that provided the ruler with the greatest prestige.

By employing royal signs on stone stelae, rulers addressed a broader group than the Bosporan audience. Specific measures can be identified that were taken to enhance the epigraphic mode of stone slabs and consequently make them resemble the commonly occurring inscribed stelae (almost exclusively in Greek). First, the shape, size, and material of the slabs matched those of standard inscriptions. Most of them were carved, with three exceptions of the relief form (Figure 8, Figure 11 and Figure 12). Second, certain slabs were adorned with decorative elements found in traditional inscriptions. For example, the tamga sign of Rhoemetalces from Tanais was framed to highlight its epigraphic character (Figure 8), and the slab with Eupator’s sign from Panticapaeum has decorative rosettes above it (Figure 9). Finally, it is worth noting that the uninscribed stelae were probably painted, as was commonly the case with inscriptions. According to the description of the lost slab with King Eupator’s tamga found in Krasnaya Batereya, remnants of red paint could be seen in the recesses of the carved sign (Solomonik 1959, p. 54). Thus, the abovementioned examples, which involve the enhancement of the epigraphic modality of these uninscribed stone slabs, validate Shkorpil’s suggestion that the sign may serve a substitute function to the text.

One can view the inclusion of royal signs within the epigraphic culture of the Bosporan Kingdom through the lens of enduring traditions. The reason for doing so is that the signs illuminate the shaping processes of self-presentation and thus a form of consciousness among local ruling elites. A notable example is King Ininthimaeus (234/5–238 CE) whose tamga appears alongside three inscriptions (CIRB 1249; 1250; 1251). It is immediately striking that his royal sign is distinctly different from the royal tamgas that preceded it, lacking the lower part, characteristic of the Tiberii Iulii, the “inverted trident.” Meanwhile, his title found in the texts of the inscriptions is a typical combination of pro-Roman elements that the rulers of the kingdom had employed for over two centuries (βασιλεύοντος βασιλέως Τιβερίου Ἰουλίου Ἰνινθιμαίου φιλοκαίσαρος καὶ φιλορωμαίου, εὐσεβοῦς).

Despite persisting into the 3rd century CE, the importance of Roman propaganda likely evolved for both parties. Tracing the political landscape of the Bosporan Kingdom during the Third Century Crisis proves exceptionally challenging. Anokhin (1999) identifies King Ininthimeus as the last of the Tiberii Iulii lineage. Highlighting the king’s official titulature, Anokhin (1999, pp. 162–64) suggests that Ininthimeus originated from the dynasty’s Sarmatian branch. Yatsenko (2001, pp. 55–56), who places greater emphasis on the tamga, theorizes that Ininthimeus could have been a Sarmatian chieftain, which corresponds with Dračuk’s (1975, pp. 63–65) view. The tamga, appearing as a single curved line and thus diverging from the Tiberii Iulii tradition, is evident on the coins of later monarchs such as Thothorses (285/6–308/9 CE). Intriguingly, a rare later inscription referencing King Teiranus (275–279 CE) continues to display the traditional pro-Roman titulature (βασιλεύοντος βασιλέως Τιβερίου Ἰουλίου Τειράνου φιλοκαίσαρος καὶ φιλορωμαίου, εὐσεβοῦς) (CIRB 36).

The account of Zosimus corroborates the altered political dynamics within the mid-3rd century CE Bosporan Kingdom. He records the extinction of the royal lineage, leaving governance to “worthless individuals” incapable of thwarting barbarian incursions (Zos. 1.31–3). It is likely that Ininthimeus represented the first Bosporan sovereign outside the Tiberii Iulii dynasty and merely adopted their official pro-Roman titles. In his analysis of coinage distribution within the Bosporan Kingdom, Bjerg (2013, pp. 211–12) rightly notes that, during Ininthimeus’ era, the pro-Roman titulature, prefixed with “Tiberius Iulius” to the king’s name, became an essential aspect of royal depiction. Moreover, to ensure control over cities and ports, any chieftain aspiring to the Bosporan throne had to align with the longstanding tradition of self-representation. Ininthimaeus, similar to his predecessors, used his Sarmatian sign while adopting the titulature of previous rulers, demonstrating how, throughout the centuries, the pro-Roman titulature intertwined with the function of a Bosporan ruler.

6. Conclusions

The so-called royal tamga signs from the Bosporan Kingdom and their use alongside Greek inscriptions serve as intriguing examples of cultural interaction and a local trend within a “global” epigraphic habit. Moreover, the application of these signs as inscriptions effectively substituting a Greek text is also a noteworthy case of local specificity. This phenomenon exemplifies an element belonging to the culture of Eurasian nomads, thus not part of the Greco-Roman epigraphic tradition, penetrating the Mediterranean epigraphic culture. These slabs cannot be considered “full-fledged” inscriptions since the “royal tamga” is not any kind of textual script (non-epigraphic slabs were not included in the charts presenting the curve). However, I believe they should be treated as an element of the Bosporan epigraphic habit. Several factors support this view, such as the appearance of the slabs during the peak period of Greek inscription production by the Bosporan Kingdom’s society and their form. Also relevant are the elements of the epigraphic mode that were applied.

Inscriptions and uninscribed stone slabs with royal signs constitute a relatively small group of public objects that the narrow elite of the kingdom or the ruler himself displayed. They should be considered an element and an essential complement to the local epigraphic habit, dominated by hundreds of private inscriptions—mostly epitaphs with accompanying reliefs. Additionally, the royal tamgas were another of several elements that composed the official image of the rulers from the Tiberii Iulii dynasty. This image took shape over centuries, absorbing Pontic/Iranian (Mithridatic), Thracian, Greco-Roman, and Sarmatian elements.24

As Gygax and Bodel noted, in a society where only a minority could read, the mere presence of an inscribed stela, along with its iconographic message in public space, constituted an important element of official communication.25 Undoubtedly, the use of the royal sign as an identifier and a text equivalent increased the “reach” of the message that the stone was meant to convey, whether it spoke of building activity or achieved victories. The royal tamga, appearing alongside the text alone or with wreaths and the figure of Victoria, constituted a clear and recognizable signal for the Bosporan population that was familiar with the epigraphic culture and for Sarmatian nomads.

Funding

Research on this topic was funded by the PRELUDIUM-17 grant from the National Science Centre (Poland) UMO-2019/33/N/HS3/01484 (Shaping the political landscape in the Bosporan Kingdom: Greek and non-Greek elites in a qualitative and quantitative approach).

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this paper is all published and can be found in the referenced sources.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Funding statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

Abbreviations

| CIRB | Strauve, Vasiliy. 1965. Corpus Inscriptionum Regni Bosporani. Москва: Наука. |

| CIRB-album | Gavrilov, Alexander, Natalia Pavlitchenko, Denis Keyer and Anatolij Karlin. 2004. Corpus Inscriptionum Regni Bosporani: Album Imaginum. St Petersburg: Biblioteca Classica Petropolitana and the St. Petersburg Institute of History of the Russian Academy of Sciences. |

| IJO | Noy, David, Hanswulf Bloedhorn. 2004. Inscriptiones Judaicae Orientis: Syria and Cyprus. Vol. 3. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. |

| ВДИ | Вестник Древней Истoрии |

| ИАК | Известия Императoрскoй Археoлoгическoй кoмиссии |

| CA | Сoветская Археoлoгия |

Notes

| 1 | (Malkin 2001, pp. 1–28; Gruen 2011, pp. 251–76; 2020, pp. 1–41; Versluys 2015, pp. 144–67). |

| 2 | For a detailed description of the changes in methodological approaches to the history of the Northern Black Sea area in antiquity, see Porucznik (2021, pp. 3–64). |

| 3 | For a general discussion, see Hall (1997, pp. 111–42) and Jones (1997, pp. 106–27). For the Black Sea area, see Petersen (2010), Stolba (2011), and Porucznik (2021, pp. 91–95). |

| 4 | In his work, Kreuz (2012) presents more than 1200 epitaphs with reliefs from the Bosporan Kingdom. Certain features are only a relief, as the text has not survived. |

| 5 | Among nearly 1600 inscriptions carved in stone and metal from the Bosporan Kingdom, there are only three Latin or Greek-Latin texts and one Greek-Hebrew bilingual (Nawotka et al. 2020, Table 11.1, p. 217). For more on the quantitative aspects of the Bosporan habit, see Halamus (2020, pp. 107–13). |

| 6 | For a detailed description of the history of research on the epigraphic habit in the Greco-Roman world, see Nawotka (2020, pp. 1–30) and Bodel (2023, pp. 1–8). |

| 7 | See Nawotka (2020). For the Black Sea area, see Porucznik (2020) and Halamus (2020). |

| 8 | An example is evident in the complete disappearance of Phoenician inscriptions or the small number of non-Greek inscriptions in heavily Hellenized Alexandria. See Głogowski (2020, pp. 166–75) and Wojciechowska (2020, pp. 187–88). |

| 9 | Porucznik (2021, pp. 99–104); Braund (2008, p. 363); Stolba (1996); Herman (1990, pp. 357–60). |

| 10 | CIRB 736; 746; 1225. Additionally, see two examples of reliefs from Tanais and Phanagoria: Böttger et al. (2002, p. 61) and Kuznetsov (2008, p. 15). Początek formularza. |

| 11 | There is a rich literature dedicated to tamgas, predominantly in Russian. See the monographs, primarily Yatsenko (2001), Dračuk (1975), Jänichen (1956) (in German), and Solomonik (1959). Additionally, see, for example, among the numerous articles, Kozlenko (2018), Treister (2011), Olkhovsky (2001), Boardman (1998) (in English); Nickel (1973) (in English). |

| 12 | Treister (2021, p. 86); Olbrycht (2004, p. 336). |

| 13 | (Rostovtzeff 1922, pp. 97–98; Sulimirski 1979, pp. 80–86; Vinogradov 2003, pp. 217–23; Olbrycht 2004, pp. 323–32; Mordvintseva 2013, pp. 212–13; 2015, pp. 121–31; 2017, p. 279). |

| 14 | Examples of inscriptions with signs placed without a clear connection to an object from the Bosporan Kingdom are, for example, the following epitaphs: CIRB-album 424, 529, 565, and 838. |

| 15 | Many scholars have debated whether the coins with the tamga of Dynamis were minted by her. The sign could also be a monogram composed of the letters Δ, Υ, Μ. However, it should be noted that this sign is found in the company of other tamgas. See Bjerg (2013, pp. 179–80), Frolova and Ireland (2002, pp. 6–7), Yatsenko (2001, p. 30), Parfenov (1996, p. 98), Nawotka (1989, pp. 328–29), Frolova (1978, p. 51), Rostovtzeff (1919, pp. 101–3). |

| 16 | This period is described in the monograph by Saprykin (2002). However, in his papers, Coşkun (2019a, 2019b) presents several alternative and interesting ideas regarding the chronology of events in this period. |

| 17 | The first attested Bosporan ruler with Tiberius Iulius as a praenomen and nomen gentilicium is Aspurgus’ son, Cotys I (45/6–67/8 CE). It is clear, however, that he could not have received this honour, as Tiberius died in 37 CE. Therefore, it must have been his father, who ruled until 37/8 CE. See CIRB 69. |

| 18 | Examples of royal tamga with inscription are as follows: CIRB 1053 (Figure 3), CIRB 1241 (Figure 4), CIRB 1248 (Figure 5), CIRB 1249 (Figure 6), CIRB 1250 (Figure 7), and CIRB 1251. Additionally, the lost CIRB 1237 = Solomonik (1959, Figure 12, p. 59), might have been another case. Uninscribed stelae with royal tamga are as follows: Böttger et al. (2002) (Figure 8), CIRB 738 (Figure 9), Kuznetsov (2008) (Figure 10), Solomonik (1959, Figure 3, p. 51) (Figure 11), and Solomonik (1959, Figure 4, p. 52) (Figure 12). Also, there is now one plate in Kerch (Solomonik 1959, Figure 5, p. 53) and one lost plate from Krasnaya Batereya (Solomonik 1959, Figure 6, p. 54). |

| 19 | A similar pair of tamgas also appears on several bronze buckles. See Treister (2011) and Solomonik (1959, Figures 84 and 85, p. 134). |

| 20 | “Nike on the prow” was present on several of King Asander’s coins and was linked with his supposed naval victories. See Saprykin (2002, pp. 73–75) and Gajdukevič (1971, p. 326). |

| 21 | For the Bosporan thiasoi and list of names within the Bosporan epigraphic habit, see Halamus (2020, pp. 110–11), Harland (2014, pp. 14–39), and Zavoikina (2013). |

| 22 | The onset and further development of epigraphic activity in the Bosporan Kingdom have been detailed in another publication. See Halamus (2020). |

| 23 | |

| 24 | To read more about how the Bosporan rulers shaped their Greek image over the centuries, see Dana (2021). |

| 25 | Bodel (2023, p. 6); Domingo Gygax (2016, pp. 221–22). Additionally, both scholars indicate that the reach of a given inscription was extended through its public reading aloud. |

References

- Alföldy, Géza. 1991. Augustus und die Inschriften: Tradition und Innovation. Die Geburt der imperialen Epigraphik. Gymnasium 98: 289–324. [Google Scholar]

- Anokhin, Vladlen Afanasyevich. 1999. Истoрия Бoспoра Киммерийскoгo. Киев: Одигитрия. [Google Scholar]

- Bilde, Pia Guldager, and Jane Hjarl Petersen. 2008. Meetings of Cultures in the Black Sea Region: Between Conflict and Coexistence. Black Sea Studies 8. Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag. [Google Scholar]

- Bjerg, Line M. Højberg. 2013. Money, Power and Communication: Coin Circulation in the Bosporan Kingdom in the Roman Period. Wettern: Moneta. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman, John. 1998. Seals and Signs. Anatolian Stamp Seals of the Persian Period Revisited. Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies 36: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodel, John. 2001. Epigraphy and the ancient historian. In Ancient History from Inscriptions. Edited by John Bodel. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bodel, John. 2023. Epigraphic Culture and the Epigraphic Mode. In Inscriptions and the Epigraphic Habit. Edited by Rebecca Benefiel and Catherine M. Keesling. Leiden–Boston: Brill, pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Böttger, Burkhardt, Jochen Fornasier, and Tatiana M. Arsen’eva. 2002. Tanais am Don. Emporion, Polis und bosporanisches Tauschhandelszentrum. In Das Bosporanische Reich. Der Nordosten des Schwarzen Meeres in der Antike. Edited by Burkhardt Böttger and Jochen Fornasier. Mainz: Verlag Philip von Zabern, pp. 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Braund, David. 2008. Scythian Laughter: Conversations in the Northern Black Sea Region in the 5th Century BC. In Meetings of Cultures in the Black Sea Region: Between Conflict and Coexistence. Black Sea Studies 8. Edited by Pia Guldager Bilde and Jane Hjarl Petersen. Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag, pp. 347–67. [Google Scholar]

- Coşkun, Altay. 2019a. The Course of Pharnakes II’s Pontic and Bosporan Campaigns in 48/47 B.C. Phoenix: Classical Association of Canada 73: 86–113. [Google Scholar]

- Coşkun, Altay. 2019b. The Date of the Revolt of Asandros and the Relations between the Bosporan Kingdom and Rome under Caesar. In Panegyrikoi Logoi. Festschrift für Johannes Nollé zum 65. Geburtstag. Edited by Margaret Nollé, Peter M. Rothenhöfer, Gisela Schmied-Kowarzik, Hertha Schwarz and Hans Christoph von Mosch. Bonn: Habelt Verlag, pp. 125–46. [Google Scholar]

- Dana, Madalina. 2021. The Bosporan Kings and the Greek Features of their Culture in the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. In Ethnic Constructs, Royal Dynasties and Historical Geography around the Black Sea Littoral. Edited by Altay Coşkun. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, pp. 141–60. [Google Scholar]

- Domingo Gygax, Marc. 2016. Benefaction and Rewards in the Ancient Greek City: The Origins of Euergetism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dračuk, Viktor Semyonovich. 1975. Система знакoв Севернoгo Причернoмрья. Киев: Наукoва думка. [Google Scholar]

- Frolova, Nina Andreevna. 1978. О времени правления Динамии. СА 2: 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Frolova, Nina, and Stanley Ireland. 2002. The Coinage of the Bosporan Kingdom from the First Century BC to the First Century AD. Oxford: BAR Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Gajdukevič, Viktor F. 1971. Das Bosporanische Reich. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Głogowski, Piotr. 2020. The epigraphic curve in the Levant: The case study of Phoenicia. In Epigraphic culture in the Eastern Mediterranean in Antiquity. Edited by Krzysztof Nawotka. New York: Routledge, pp. 166–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gruen, Erich S. 2011. Rethinking the Other in Antiquity. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gruen, Erich S. 2020. Ethnicity in the Ancient World—Did it Matter? Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Halamus, Michał. 2017. Barbarization of the State? The Sarmatian Influence in the Bosporan Kingdom. ВДИ 77: 688–95. [Google Scholar]

- Halamus, Michał. 2020. The epigraphic curve in the Northern Black Sea region: A case study from Chersonesos and the Bosporan Kingdom. In Epigraphic Culture in the Eastern Mediterranean in Antiquity. Edited by Krzysztof Nawotka. New York: Routledge, pp. 102–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Jonathan Mark. 1997. Ethnic Identity in Greek Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harland, Philip A. 2014. Greco-Roman Associations: II. North Coast of the Black Sea, Asia Minor. Berlin and Boston: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, Gabriel. 1990. Patterns of Name Diffusion within the Greek World and Beyond. The Classical Quarterly 40: 349–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jänichen, Hans. 1956. Bildzeichen der königlichen Hoheit bei den iranischen Völkern: Antiquitas: Reihe 1, Abhandlungen zur Alten Geschichte 3. Bonn: Habelt. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Siân. 1997. The Archaeology of Ethnicity Constructing Identities in the Past and Present. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlenko, Roman A. 2018. Тамгooбразные знаки из Ольвии (к прoблеме сарматскoгo присутствия). Stratum plus. Археoлoгия и культурная антрoпoлoгия 4: 239–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuz, Patric-Alexander. 2012. Die Grabreliefs aus dem Bosporanischen Reich. Leuven, Paris and Walpole: Peeters Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov, Vladimir Dmitrievich. 2008. Фанагoрия. Пo материалам Таманскoй экспедиции. Мoсква: Северный палoмник. [Google Scholar]

- MacMullen, Ramsay. 1982. The Epigraphic Habit in the Roman Empire. American Journal of Philology 103: 233–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkin, Irad, ed. 2001. Ancient Perceptions of Greek Ethnicity. Cambridge: Center for Hellenic Studies, Trustees for Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Caspar. 2013. Greco-Scythian Art and the Birth of Eurasia. From Classical Antiquity to Russian Modernity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Elizabeth A. 1990. Explaining the Epigraphic Habit in the Roman Empire: The Evidence of Epitaphs. Journal of Roman Studies 80: 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Elizabeth A. 2011. Epigraphy and Communication. In The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World. Edited by Michael Peachin. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 191–208. [Google Scholar]

- Mordvintseva, Valentina Ivanovna. 2013. The Sarmatians: The Creation of Archaeological Evidence. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 32: 203–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordvintseva, Valentina Ivanovna. 2015. Сарматы, Сарматия и Севернoе Причернoмoрье. ВДИ 292: 109–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mordvintseva, Valentina Ivanovna. 2017. The Sarmatians in the Northern Black Sea region. In The Northern Black Sea in Antiquity: Networks, Connectivity, and Cultural Interaction. Edited by Valeriya Kozlovskaya. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 233–83. [Google Scholar]

- Nawotka, Krzysztof. 1989. The Attitude Towards Rome in the Political Propaganda of the Bosporan Monarchs. Latomus 48: 326–38. [Google Scholar]

- Nawotka, Krzysztof. 2020. Introduction: Epigraphic habit, epigraphic culture, epigraphic curve: Statement of the problem. In Epigraphic Culture in the Eastern Mediterranean in Antiquity. Edited by Krzysztof Nawotka. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Nawotka, Krzysztof, Naomi Carless Unwin, Piotr Głogowski, Dominika Grzesik, Michał Halamus, Paulina Komar, Joanna Porucznik, Łukasz Szeląg, Joanna Karolina Wilimowska, and Agnieszka Wojciechowska. 2020. Conclusions: One or many epigraphic cultures in the Eastern Mediterranean. In Epigraphic Culture in the Eastern Mediterranean in Antiquity. Edited by Krzysztof Nawotka. New York: Routledge, pp. 215–46. [Google Scholar]

- Nickel, Helmut. 1973. Tamgas and Runes, Magic Numbers and Magic Symbols. Metropolitan Museum Journal 8: 165–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olbrycht, Marek J. 2004. Mithradates VI. Eupator, der Bosporos und die sarmatischen Völker. In Kimmerowie, Scytowie, Sarmaci. Księga poświęcona pamięci Profesora Tadeusza Sulimirskiego. Edited by Jan Chochorowski. Kraków: Księgarnia Akademicka, pp. 331–47. [Google Scholar]

- Olkhovsky, Valeriy Sergeevich. 2001. ТАМГА (к функции знака). Истoрикo-археoлoгический альманах 7: 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Parca, Maryline. 2001. Local languages and native cultures. In Ancient History from Inscriptions. Edited by John Bodel. New York: Routledge, pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Parfenov, Victor N. 1996. Dynamis, Agrippa und der Friedensaltar. Zur militärischen und politischen Geschichte des Bosporanischen Reiches nach Asandros. Historia 45: 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, Jane Hjarl. 2010. Cultural Interactions and Social Strategies on the Pontic Shores. Burial Customs in the Northern Black Sea Area ca. 550–270 BC. Burial Customs in the Northern Black Sea Area ca. 550–270 BC. Black Sea Studies 12. Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag. [Google Scholar]

- Porucznik, Joanna. 2020. The epigraphic curve in the Black Sea region: A case study from North-West Pontus. In Epigraphic Culture in the Eastern Mediterranean in Antiquity. Edited by Krzysztof Nawotka. New York: Routledge, pp. 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- Porucznik, Joanna. 2021. Cultural Identity within the Black Sea Region in Antiquity: (De)constructing Past Identities. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Rostovtzeff, Michael. 1919. Queen Dynamis of Bosporus. JHS 39: 88–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostovtzeff, Michael. 1922. Iranians and Greeks in South Russia. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saprykin, Sergey Yuryevich. 2002. Бoспoрскoе царствo на рубеже двух эпoх. Мoсква: Наука. [Google Scholar]

- Shkorpil, Vladislav Vyacheslavovich. 1910. Заметка o рельефе на памятнике в честь Евпатерия. ИАК СПБ 37: 18–35. [Google Scholar]

- Solomonik, Ella Isaakovna. 1959. Сарматские знаки Севернoгo Причернoмoрья. Киев: Наукoва думка. [Google Scholar]

- Stolba, Vladimir F. 1996. Barbaren in der Prosopographie von Chersonesos (4.-2. Jh. v.Chr.). In Hellenismus. Beiträge zur Erforschung von Akkulturation und Politischer Ordnung in den Staaten des Hellenistischen Zeitalters. Edited by Bernd Funck. Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck) Tübingen, pp. 439–66. [Google Scholar]

- Stolba, Vladimir F. 2011. Multicultural Encounters in the Greek Countryside: Evidence from the Panskoye I Necropolis, Western Crimea. In Pontika 2008. Recent Research on the Northern and Eastern Black Sea in Ancient Times, Proceedings of the International Conference, Kraków, Poland, 21–26 April 2008. Edited by Ewdoksia Papuci-Władyka, M. Vickers, J. Bodzek and D. Braund. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 329–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sulimirski, Tadeusz. 1979. Sarmaci. Warszawa: PIW. [Google Scholar]

- Tokhtas’ev, Sergey Remirovich. 2013. Иранские имена в надписях Ольвии I–III вв. н.э. In Commentationes Iranicae. Сбoрник статей к 90-летию Владимира Арoнoвича Лившица. Edited by Sergey R. Tokhtas’ev and Paul Lurje. Санкт-Петербург: Нестoр-Истoрия, pp. 565–607. [Google Scholar]

- Treister, Mikhail. 2021. Archaeological Evidence of Migration from East to West in Eurasia (2nd–1st Century BC): Pro and contra Arguments. In Migration and Identity in Eurasia: From Ancient Times to the Middle Ages. Edited by Victor Cojocaru and Annamária-Izabella Pázsint. Cluj–Napoca: Editura MEGA, pp. 87–114. [Google Scholar]

- Treister, Mikhail Yurevich. 2011. Брoнзoвые и зoлoтые пряжки и накoнечники пoясoв с тамгooбразными знаками—фенoмен бoспoрскoй культуры II в. н. э. Древнoсти Бoспoра 15: 303–41. [Google Scholar]

- Versluys, Miguel John. 2015. Roman visual material culture as globalising koine. In Globalisation and the Roman World. World History, Connectivity and Material Culture. Edited by Martin Pitts and Miquel John Versluys. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 141–74. [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradov, Yuri A. 2003. Two Waves of Sarmatian Migration in the Black Sea Steppes during pre-Roman period. In The Cauldron of Ariantas: Studies Presented to A.N. Sceglov on the Occasion of His 70th Birthday. Edited by Guldager Pia Bilde, Jakob M. Højte and Vladimir F. Stolba. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, pp. 217–26. [Google Scholar]

- Vlassopoulos, Kostas. 2013. Greeks and Barbarians. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, Bella Ilinichna, and Eleonora Afanasyevna Novgorodova. 1976. Заметки o знаках и тамгах Мoнгoлии. In Истoрия и культура нарoдoв Средней Азии (древнoсть и средние века). Edited by Bobodzhan Gafurovich Gafurov and Boris Anatolyevich Litvinsky. Мoсква: Наука (ГРВЛ), pp. 66–74, 176–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowska, Agnieszka. 2020. The epigraphic curve in Egypt: The case study of Alexandria. In Epigraphic Culture in the Eastern Mediterranean in Antiquity. Edited by Krzysztof Nawotka. New York: Routledge, pp. 184–200. [Google Scholar]

- Woolf, Greg. 1996. Monumental Writing and the Expansion of Roman Society in the Early Empire. Journal of Roman Studies 86: 22–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yatsenko, Sergey Aleksandrovich. 2001. Знаки-тамги иранoязычных нарoдoв древнoсти и раннегo средневекoвья. Мoсква: Вoстoчная литература. [Google Scholar]

- Yatsenko, Sergey Aleksandrovich. 2005. Тамги и эпиграфика Бoспoра. БФ 2005: 414–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zavoikina, Natalia Vladimirovna. 2003. К вoпрoсу o так называемых царских тамгах Бoспoра (154–238 гг.). Бoспoр киммерийский и варварский мир в периoд античнoсти и средневекoвья. Материалы IV Бoспoрских чтений Керчь: 100–2. [Google Scholar]

- Zavoikina, Natalia Vladimirovna. 2013. Бoспoрские фиасы: между пoлисoм и мoнархией. Мoсква: Университет Дмитрия Пoжарскoгo. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).