Abstract

In the spring and summer of 1906, while visiting the rural village of Gósol in the Spanish Pyrenees, Picasso executed his first woodcut, made two sculptures out of boxwood, and began to focus on the topoi of wood and the forest as avatars of primal matter and of that which lies beyond civilization. In a subsequent series of paintings, he used wooden supports for images that depict male and female heads that look as if they had been chiseled out of wood. Others represent nude figures in forest settings, with explicitly sexual gestures and poses connoting a range of attitudes. These little studied works provide an optic into Picasso’s early exploration of the emergence of sexual identity as an inner psychic state, but one whose signs can be read through the body. Later, responding to the proliferation of cheap, industrially produced materials, including trompe l’oeil woodgrain wallpaper, Picasso began to treat woodgrain as a mere surrogate, one that marks its distance from actual wood through a variety of painterly and mechanical effects. No longer associated with “primitive” authenticity and the primordial forces of the forest, woodgrain now appears as a false sign open to conceptual play and metamorphosis.

I experienced my purest emotions in a great Spanish forest, where, at sixteen years of age, I had withdrawn to paint.

I felt my greatest artistic emotions when I suddenly encountered the sublime beauty of sculptures executed by the anonymous artists of Africa. These works of religious art, passionate and rigorously logical, are the most powerful and most beautiful that the human imagination has produced.

I hasten to add that, despite this, I detest exoticism.

“Propos de Picasso”, recorded in (Picasso 1917)1

Picasso’s early forest dwellers emerge from the traces of his memories of a Spanish forest, the shock of his encounter with African and Polynesian sculpture in 1906–1907, the many bathers among trees in Paul Cézanne’s late work, and the wood carvings of Paul Gauguin. Although the artist would later affirm a freely creative treatment of materials in which anything might be transformed into anything else, in his proto-Cubist and early Cubist works, wood takes on symbolic significance as a purportedly primal material. Indeed, wood has a long history in the West of standing for matter itself, as the etymology of the Greek term hyle (wood, matter, that which is disorganized, cannot be counted, and receives form) and the Latin materia (timber, wood, matter as opposed to mind, spirit), indicate. In his Physics and other works, Aristotle distinguished between hyle and morphé (shape, form, structure), between the fundamental (first) matter of all things, and the shape or structure it is given by immaterial ideas.2 According to this hylomorphic model, hyle or wood/matter carries a sense of potentiality as that which receives form from outside of itself, whereas morphé manifests as actualized form. Further, hyle refers to the supposedly passive, feminine role of the mother (she becomes body/vessel, a material substrate), who receives the fully formed homunculus from the active father and merely provides it with nourishment. The close link of matter and mater, matter, mother, and matrix retains these associations.

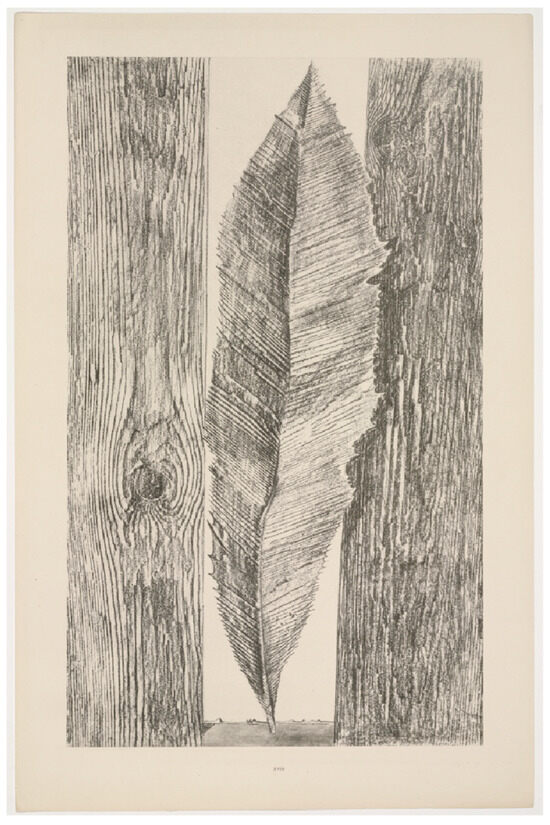

This philosophical construct transcends the historical moment in which Picasso first explored the primal resonances of wood and the forest as a mythological dwelling place, a timeless realm seemingly beyond the reach of civilization and its laws. I offer the following examples that postdate Picasso’s work; although they were not works that he could have drawn from, they allow us to examine key features of this pervasive Western understanding of wood as a primordial material, a receptive matrix open to external shaping forces including the human imagination. This attitude toward wood can be seen in the German artist Max Ernst’s purportedly chance discovery of a technique he called frottage (rubbing). As Ernst tells it, one rainy evening on August 10, 1925, he found himself staring at the floorboards in a seaside inn while in an excited, semi-hallucinatory state. Like Leonardo who had seen marvelous images in spots on a wall, flowing streams, and clouds, Ernst began to perceive images in the woodgrain that he captured by rubbing black lead onto paper placed directly against the boards (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Max Ernst, The Habit of Leaves, from Histoire Naturelle, 43 × 25.9 cm, ca. 1925, published in 1926. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

This process intensified his vision, bringing forth a spontaneous succession of superimposed and contradictory images that he transformed into drawings that revealed the “first cause” of his obsessive gaze, “or produced a simulacrum of that cause”. Although he admits to transmuting these rubbings to a significant degree, so that the imprint of the floorboards was diminished, Ernst nonetheless poses as a spectator at the “birth of the work”, as if the wood and his unconscious had conspired to produce the completed frottages.3

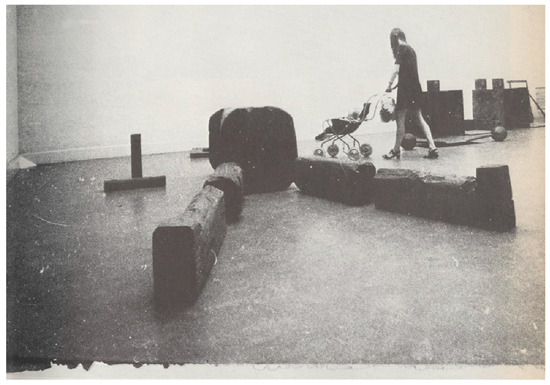

Another example can be found in Joseph Beuys’ Jungfrau (Holz) [Virgin], initially created in 1958 (Tate Gallery) in oil on paper but translated into teak in 1961 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Joseph Beuys, Jungfrau (Holz), [Virgin], 9 sections carved in teak, ca. 300 × 200 × 100 cm, 1961–1979. Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt, Ströher Collection. Photo: Ute Klophaus. © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

This work, according to the artist, “relates to woman, and to the female element in general. To express spiritual power and potential”, he declared, “I tend usually to use the female figure”.4 Above the small head of the figure, the artist placed a square frame, a geometric form he associated with masculinity. Attributing specific capacities and tendencies to men and women based on their physiology, Beuys further explained that “This frame represents a balance towards the male, towards the cold, hard, crystallized, burnt-out clinker that I would call the male intellect, the cause of much of our suffering. If you consider male physiology, you will agree that the male is anatomically squarer…”5 According to this binary schema, the “female element in general” needs to be supplemented with a square sign of male intellect, one that Beuys also sees as emanating from his anatomy. Some balance might be achieved by a partial redistribution or interfusion of attributes, but they remain associated with an essentializing gender binary. As Beuys puts it, “the square frame is a reminder that she too possesses this intellectualizing potential”; he needed to add this reminder because the very structure and materiality of the teak sculpture negates this capacity.6 In fact, the wooden frame had not been included in the oil study, but part of it is visible in the photograph taken by Beuys’ long time photographer, Ute Klophaus.

To realize the sculptural version of Virgin, Beuys cut down a teak tree in his backyard, creating nine minimally carved blocks. For his major retrospective at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 1979, he laid these blocks horizontally along the floor as separate elements, with Virgin’s legs splayed apart in a manner that signifies sexual availability; the enlarged torso suggests the “virgin” is already impregnated. Working closely with Beuys, Ute Klophaus emphasized this open pose in the image for the catalogue, in which she also captured a young mother pushing a child in a stroller, as if it were the immutable condition of women to be vehicles of procreation. In a similar fashion, Beuys conceived Virgin’s horizontality as a permanent state; composed of disconnected, heavy elements, the figure’s legs could not be concerted to rise, and the small head does little to suggest thought or the possibility of voluntary action despite the square frame Beuys placed above it. Nor does Virgin have arms or hands to enable action or creative expression in the world. Here the equation of wood and of primal or ur-matter as a feminized, horizontal, passive but fertile matrix finds exemplary articulation.

From 1906 to 1908, Picasso also seems to have understood wood as a primordial substance, associated with the sculptures of Africa and Polynesia, as well as of Romanesque Spain and Northern Europe, and with the forest as an ancient adobe for human beings before, and forever beyond, civilization.7 Yet by the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, matter had begun to acquire a new definition as a form of energy, as comprising volatile molecules and internal forces of its own. Modernist artists often strove to achieve what we now call “truth to materials” and to preserve the “integrity” of the medium by allowing its physical characteristics to remain visible through bare patches of canvas or panel, roughly applied brushstrokes and drips of paint, or direct carving in wood. Modernism can be understood as the effort to defeat merely arbitrary inventions by “motivating” its forms; often this occurs by allowing the medium to appear to determine a work’s shape or structure, in an effort to link matter and the creative act, body and spirit. Picasso’s work in the medium of wood registers this tension, between wood as unshaped and primal and wood as already bearing within itself particular material characteristics that to some extent must be respected or brought forth by the artist’s creative process.

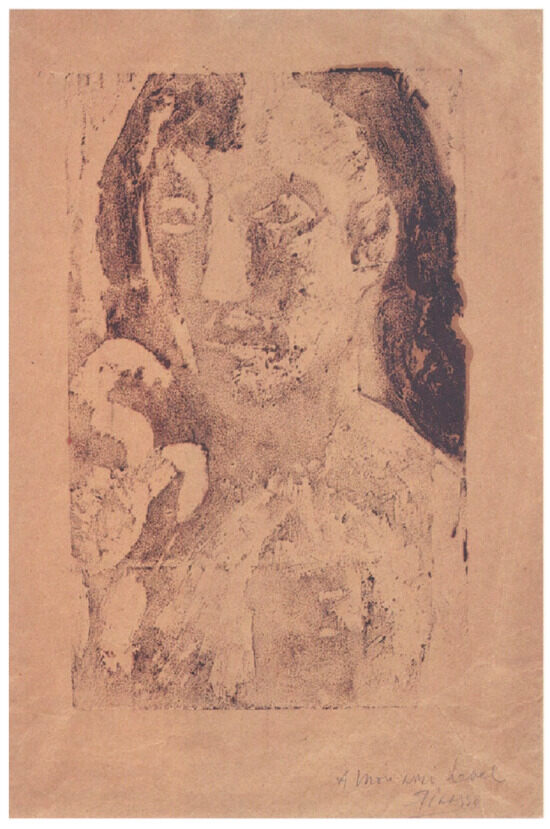

Picasso’s arrival in Gósol, Spain, in early June of 1906, seems to have activated his memories of Spanish forests and his interest in archaic or “primitivizing” sculptural forms as well as in wood as a medium. The artist executed his first woodcuts during this summer of 1906 with crudely drawn marks, carving into his wooden blocks so that they effect a near equation of figure and ground. Bust of a Woman with Raised Hand depicts a young woman with her right hand raised to her shoulder (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Pablo Picasso, Bust of a Woman with Hand Raised, woodblock print carved with gouge and hand patterned by artist, 21.9 × 13.8 cm, spring/summer 1906. Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Gift of Lois and Michael Torf. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Bernhard Geiser has identified twelve proofs, each colored differently by the artist in oil or gouache; the wood block seems not to have been preserved. Picasso printed the woodcut shown here in blackish-brown oil, but explored the possibilities of color in warm toned gouaches: in ochre, red-orange, and red and blue (G 211).8 This set of painterly prints is closely related in color to paintings the artist executed on wood in the summer and fall of 1906, such as Fernande on a Mule and Fernande with a White Shawl that explore the remote rural village of Gósol and its inhabitants’ daily lives.9 The figure’s prominent hand gesture, with only her index and baby finger extended and curled, appears frequently in the artist’s works leading up to Two Nudes of 1906 (MoMA). Reversed in relation to its carved block, it reprises the gesture seen in works such as Bust of a Woman with Her Left Hand Raised and Female Nude Against a Red Background.10 This gesture grows out of an earlier series on the subject of Aphrodite rising from the sea and wringing the water out of her hair, or images of a woman combing her hair or fingering the mantilla that falls over her shoulder. Yet Picasso developed this curious, awkward hand gesture so that in subsequent works, rather than evoke narcissism, it began to signify self-awareness or inward knowledge.

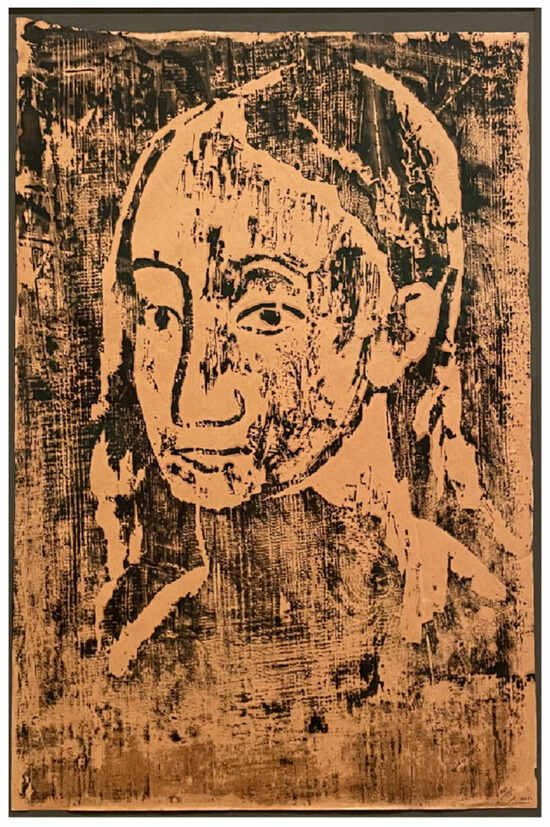

In Bust of a Woman with Raised Hand, the artist’s earliest woodcut as far as we know, the oil paint largely obscures the grain of the block. Later, in the much larger Bust of a Woman in Three-Quarter Profile, probably executed in the fall of 1906 in Paris and with better tools, Picasso dispensed with effusive, painterly displays of color in favor of sharp contrasts of black and white (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Pablo Picasso, Bust of a Woman in Three-Quarter Profile, woodcut, oil on brown wove paper, 52.5 × 34.5 cm, fall 1906. Proof printed by the artist in 1933. The Art Institute of Chicago. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Printed by the artist with black oil paint, originally in only three proofs (and later reprinted in 1933 by the artist in an edition of fifteen with two proofs), the work instantiates the near identity of figure and ground. The image surfaces into visibility, only to sink back into its striated matrix. Distinct areas of light and shade seem arbitrarily distributed in defiance of a single source of illumination. A dark shadow engulfs the right side of the woman’s neck (to our left), allowing the grain and a prominent knot in the fir block to emerge, while the hair falling to our right becomes legible as wood, its linear pattern provided by the grain of the support.11 Picasso carved away most of the plane of the face, so that it figures to some extent as an absence, but he also left many areas untouched so that, receiving pigment, they read as painterly marks; this produces dark, stain-like smudges that assert the constant presence of the wooden matrix as it permeates the image. Whereas Picasso’s etchings and drypoints of 1905 had revealed the artist’s mastery of the nuanced, elegant line, often set against a blank or neutral ground, here he aims for broad, crudely defined boundaries, created at times from gouged out voids, or alternatively, from ridges that produce thick black lines when inked. Rough lines define the neck and the top of the head, and a single wide black stroke traces the edge of the right eyebrow through the nose and across the philtrum (a shorthand way of signifying that this side of the face is further away, and that it is in shadow). Picasso simplifies the woman’s features, while widening and flattening her neck and the back of her head, to deny any convincing illusion of volume. He would apply a similar schematization to the features of his own face in his Self-Portrait with Palette of 1906 (Philadelphia Museum of Art), so that a hint of his visage appears mingled with that of this young woman, inspired by his companion Fernande Olivier. At this point, Picasso translates Olivier’s features through the model of the ancient Iberian limestone heads he had seen at the Louvre prior to leaving for Spain. Yet in creating a similarly abstracted facial structure, he chose wood as a medium rather than stone. It is noteworthy that although Picasso had seen several wooden and ceramic sculptures by Gauguin in late April 1906 at the home of the painter and designer Gustave Fayet, his own early practice of wood carving bears little resemblance to that of the older artist. Gauguin appears to have been important primarily for his rejection of Western norms and civilization, and his quest for a simpler life and sexual freedom in Polynesia, rather than for his specific treatment of wood or clay. Gauguin’s wood sculptures were far more refined, with areas of high finish and detail, than those Picasso executed from 1906 to 1908.

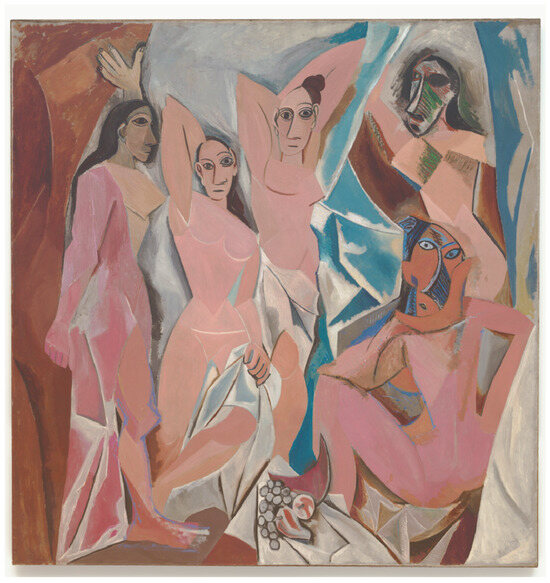

Bust of a Woman in Three-Quarter Profile allows us to see Picasso exploring the potential of the crudely executed woodcut to enhance the “primitive” associations of this figure, a precursor to the women depicted in Two Nudes and the Demoiselles d’Avignon of 1907. Here medium, technique, and abstracted forms coalesce to evoke an image of woman as avatar of an archaic, or even timeless, past, emerging as if from a forested environment and still imbued with its primordial materiality. As Robert Rosenblum has noted, Picasso’s summer in Gósol “prompted many kinds of regression to ethnic and primitive roots…. Not only did it stir in him a fresh sense of his Spanish origins but it triggered a broader fascination with a remote world, unpolluted by modern history.”12 This remote world also allowed the artist to imagine a series of erotic scenes, from a dreamy harem conveyed in rose-colored hues to nude figural studies of male and female adolescents in arcadian terracotta and ocher that suggest sexual awakening and yearning.

While in Gósol, Picasso also created his first sculptures out of wood. Josep Palau i Fabre, author of a catalogue raisonné on Picasso’s work, recalls the artist speaking to him on several occasions of the “bois de Gósol”: “That was the name he gave to a tree-trunk which, apparently, he had wanted to give–or help to acquire–a human structure which he could see prefigured in it. This attempt was also one of his basic concerns at that time.” Drawings for this “bois” appear in the Catalan Sketchbook.13 Palau i Fabre’s uncertainty over whether Picasso wanted to endow the tree trunk with form, or “help” it to acquire a human form already prefigured in it, is telling. Somehow the artist had both to treat the trunk as primal matter, as unshaped and awaiting his creative intervention, and simultaneously as already imbued with a form that he would merely help to disengage. This form could not stray too far from the shape of the slender boxwood trunk if it were to preserve a sense of its seemingly primordial materiality, and it had to be carved only minimally and roughly, in a manner that would reveal the sculpture’s identity as a piece of wood. The depicted woman and the boxwood trunk had to seem nearly indistinguishable.

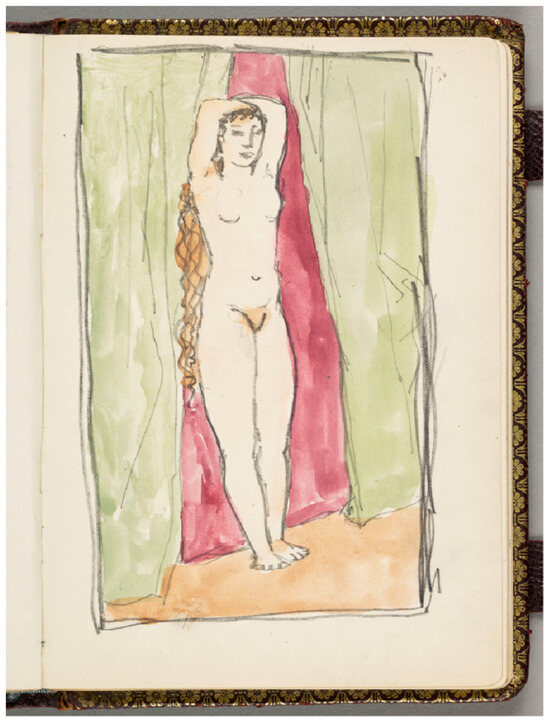

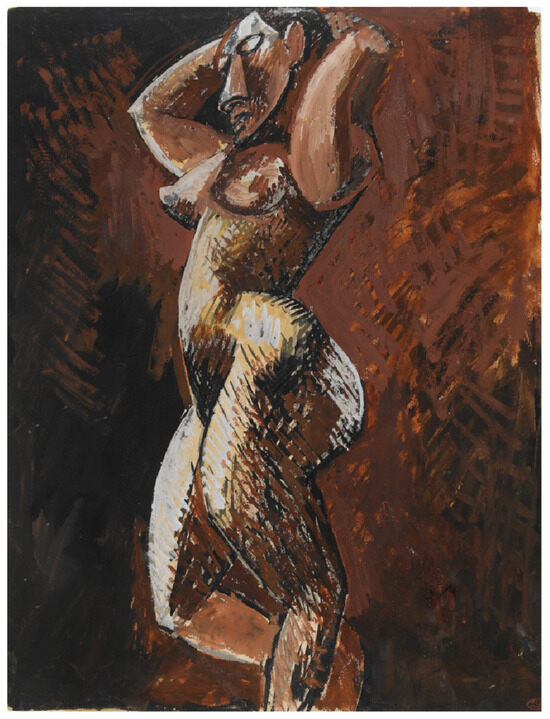

Yet Picasso lacked the tools he needed. He repeatedly wrote to his friend, the classical stone sculptor Enric Casanovas, who intended to visit him in Gósol, asking him to bring carving implements and paper. In a letter of June 27, Picasso appeals to Casanovas: “I continue working and this week they brought me a piece of wood and I’ll begin something. Tell me a few days before you come so that I can answer you because I may want you to bring some eynas [sic. chisels] to work the wood.” He wrote again in July, probably with the understanding that Casanovas would not visit him: “Could you send me in the same package two or three small eines to work in wood?”14 It is unclear if Picasso ever received the chisels, and it seems he may have resorted to using kitchen knives to carry out his carving. In the end, he produced two narrow sculptures out of the wood he had received. In one, he incised the form of a woman with legs pressed together and arms crossed overhead within a smoothed-out columnar shape that betrays its rough matrix at top and bottom (Figure 5). The gesture of arms held over the head to form a kind of archway appears in other contemporary works, where it serves to constitute the corporeal sign of a threshold, one the figure both assumes and is poised to cross (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Pablo Picasso, Nude with Raised Arms, boxwood, 46.5 × 4.5 × 6.5 cm, 1906. Musée national Picasso, Paris. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 6.

Pablo Picasso, Nude with Raised Arms between Two Curtains, from Carnet 6, folio 45r, graphite and gouache on paper, 18.5 × 13 cm, 1906. Musée national Picasso, Paris. Photo: Mathieu Rabeau. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The figure’s self-framing gesture, differing in important ways from the single bent arm held aloft over the head, a conventional pose of seduction, enacts a state of passage, of sexual awakening, a key theme for Picasso during these years. Moving through the liminal space of a threshold, whether in the form of a theatrical curtain as in Young Girl with a Goat (Barnes Foundation) or Two Nudes (Figure 9) or in the form of an archway as in several drawings of adolescent males and females, signified the before and after of sexual experience. But for Picasso, the body itself could signify this passage, this psychic and physical transformation, through bodily posture alone.

In the other boxwood sculpture, the artist hacked away at the wood so that it portrays the slightly tilted shape of a woman, with both arms cleaving tightly to her torso; the right arm runs the length of her side, while the left bends to raise a hand to her shoulder (Figure 7). The artist gave greater definition to the head and its features, which recall those of Olivier, although the head rests on a thickened, crudely hewn neck. Traces of red and black paint on the right side and the back, perhaps inspired by the polychrome Gósol Madonna, a wooden sculpture of the 12th century that the artist could have seen in the Church of Santa Maria in the Castle of Gósol, endow the work with a sense of ruin, suggesting it must have been more fully colored in the past. Drawings for this sculpture in the Catalan notebook suggest that Picasso was able to achieve the effects he desired, despite his lack of training in wood carving (see note 13). In 1932, he showed these wood sculptures to Brassai, explaining that “he had not wanted to smooth them out too much, so that the wood with—its structure, its knots and fibers–would remain alive.”15

Figure 7.

Pablo Picasso, Bust of a Woman (Fernande), carved boxwood with traces of red and strokes of black paint, 77 × 17 × 16 cm, Gósol, 1906. Musée national Picasso, Paris. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Significantly, both works treat the body as a single, unified shape, without gaps or projecting limbs that would break the uniformity and solidity of the whole. In Bust of a Woman (Fernande), the woman who emerges from the wood does not have distinct legs and feet to carry her weight; moreover, neither of the works has a supporting base. This anti-classical posing of bodies that do not meet the ground in a graceful, convincingly naturalistic way, presents them as objects to be held in the hand in any position or mounted on an external structure. This precarity enhances a sense that the sculptural object should be apprehended through both vision and touch, as an object that continues to be a piece of wood. Whether consciously or not, the artist gave these columnar sculptures a distinctly phallic shape, one that Sigmund Freud would argue in his essay “Fetishism”, of 1927, reveals a disavowal of the unwelcome discovery by the little boy that a woman does not have a penis. Believing she must have had one and has lost it, he fears for his own bodily integrity.16 Seen in this light, the self-sealing, phallic bodies of these women function as fetishistic objects that oscillate between male and female attributes, the nude’s entire body both standing in for the missing penis and covering over her supposed lack. In making this observation, I do not intend to suggest that Picasso was familiar with Freud’s theories, but simply that they both drew from contemporary notions that located psychic phenomena in bodily experience and childhood traumas, and that Picasso, like Freud, was not afraid to ponder questions of sexual identity, masculine fear of sexual difference, the fluidity of infantile desire, and the ambiguous relation of desire to human morphology.

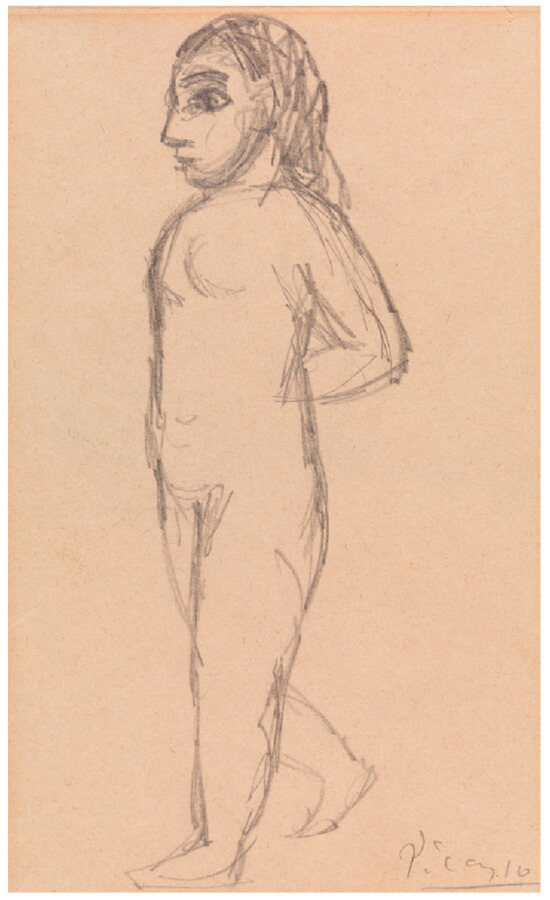

A similar drive to unify the female body, smoothing over and emphasizing the continuity of its curves and thickening the neck so that head, neck, torso, and legs become more tightly joined in a simplified, abstracted, and columnar shape, occurs in numerous drawings of this period. In Nude Girl Walking of 1906, for example, we can observe the artist drawing over the descriptive contours of a girl’s body in order to schematize her shape, while also denying the extension of her right shoulder into depth and rendering her face in a masklike way (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Pablo Picasso, Nude Girl Walking, graphite on wove paper, 17.1 × 11.1 cm, 1906. Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

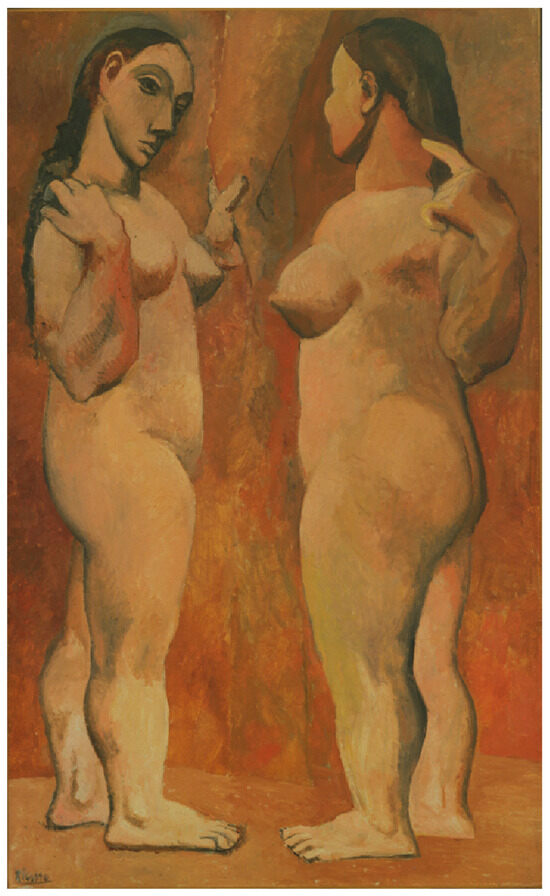

Such departures from naturalism reveal Picasso’s growing interest in a “primitive” female body, sometimes rendered analogous to a trunk of wood in its columnar self-containment and unbreached wholeness. Leo Steinberg interpreted the bodies of the women in Two Nudes, the work that precedes the Demoiselles d’Avignon of 1907, as signifying their raw materiality and virginity by recourse to an analogy with “carved logs” (Figure 9 and Figure 10). Whereas the figures in the Demoiselles, a brothel scene, stare down their male clients in “a clash of the sexes and a reciprocal shock” in an implicitly shared space, Picasso set the Two Nudes in a female-only antechamber, a space of anticipation and “a place, a condition rather, of woman alone.”17 Steinberg calls attention to the change in body types as the women move through the depicted curtain from the antechamber in Two Nudes to the scene of sexual confrontation in the Demoiselles:

In the earlier painting, a pair of crude, sturdy maidens stand like carved logs–timber lately enwoman’d, ensouled. They are forms intact, their humanity sealed in integuments of solid fusion. As sculptured monoliths, they suggest matter never yet plied or stretched. As creatures of growth, they appear raw and unbreached. As physiological types, they seem unadapted and unaccustomed to motion, with flesh that has never submitted to pressure. Bodies, then, of primal virginity…18

Figure 9.

Pablo Picasso, Two Nudes, oil on canvas, 151.3 × 93 cm, 1906. Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of G. David Thompson in honor of Alfred H. Barr Jr. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 10.

Pablo Picasso, The Demoiselles d’Avignon, oil on canvas, 243.9 × 233.7 cm, June–July 1907. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

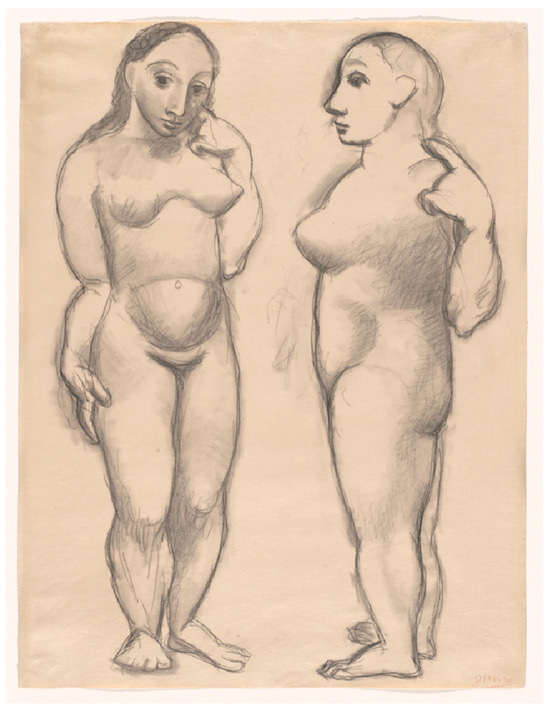

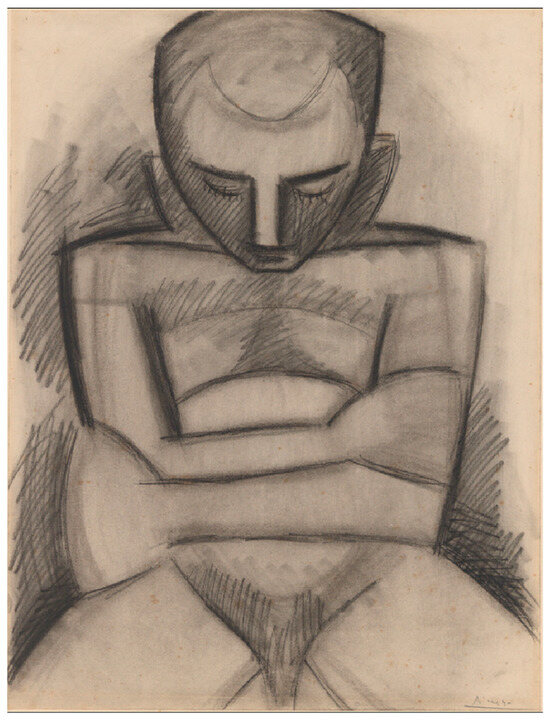

One can further note that in one of the studies for Two Nudes, the posture of the nude on the left depicts the figure with her right arm adhered to her side and her left arm bent at the elbow with a hand raised to her face in a gesture familiar from his first woodcut, Bust of a Woman with Hand Raised (Figure 3 and Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Pablo Picasso, Study for Two Nudes, conté crayon on paper, 62 × 47.3 cm, 1906, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, The Joan and Lester Avnet Collection. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Picasso had also carved a related figure in one of his boxwood sculptures in Gósol, Bust of a Woman (Fernande) (Figure 7).19 The metaphor of the wooden logs that Steinberg detected had been at the origin of these figures.

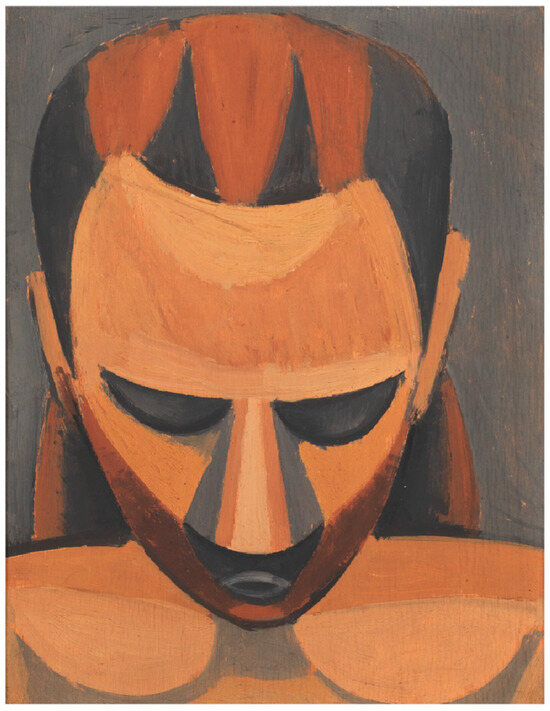

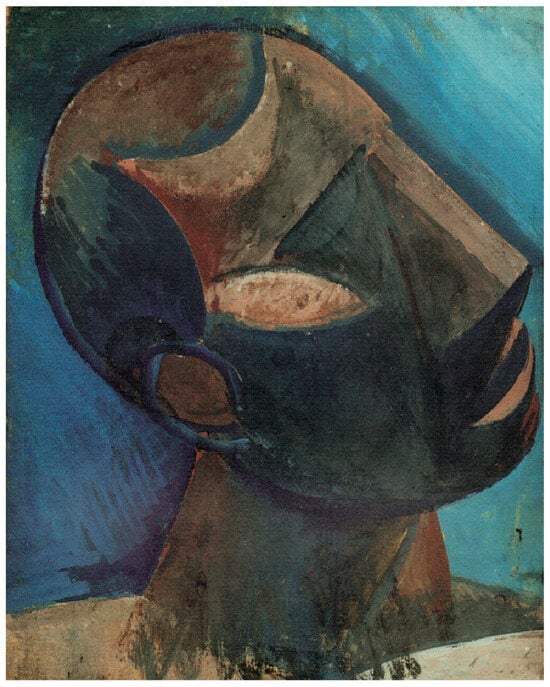

Explorations of a similarly “primitive” male figure were taking shape as well. In spring 1908, during a time when Picasso was haunting the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro to view its collection of African art, he executed a little-analyzed series of male heads on wooden panels of identical size. These works present heads that appear as if chiseled out of wood in extreme close-up; the heads bend forward into the viewer’s space, or tilt upward as if to catch a light they cannot see, but simultaneously withdraw from the viewer with closed or averted eyes. In Head of a Man, the male head, depicted from above, inclines forward, so that the supporting neck as a connecting structural element becomes nearly invisible (Figure 12). This posture emphasizes the hieratic frontality and near rectilinear symmetry of the figure, invoking African and Egyptian religious prototypes. Yet, some irregularities can be noted; Picasso placed the man’s left ear (to our right) slightly higher than his right ear, thereby intimating a turn to our left, while the curve defining his brow rises in the opposite direction. The man sits on a plain wooden chair whose curved black and brown back appears just behind his head (and the misaligned ocher ears), in tones that echo those of his head. Schematic eyes, rendered in black lines with a blue-grey wash, deny access to the man’s gaze, while a sharply articulated curve divides light from dark, inumbrating the lower part of the face. Simple geometries and elemental forms prevail over nuanced transitions, creating echoes across the visage while avoiding signs of individuality. Somewhat varied, wedge-like triangular shapes in the hair, apparently inspired by the triangular motifs at the top of a Kru mask in the collection of the Trocadéro, resemble those that describe the nose, while a small oval mouth, also clearly derived from African masks, appears out of scale to the expanded and splayed-out nose above. Picasso rendered the forms primarily in browns, ochres, and blacks, colors that evoke wood.

Figure 12.

Pablo Picasso, Head of a Man, oil on wood panel, spring 1908, 27 × 21 cm, spring 1908. Kunstmuseum Bern, Fondation Hermann et Margrit Rupf. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

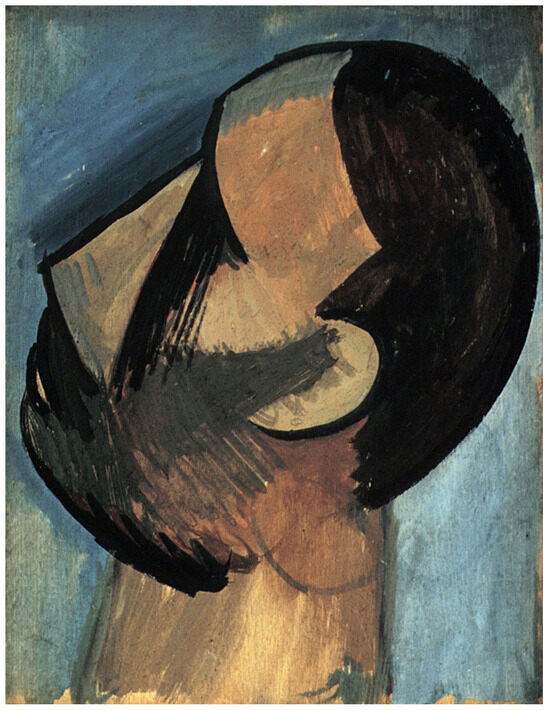

Picasso endowed another male head, seen in profile with his head tilted upwards, with a closed eye, sharply defined, wedge-like nose, and strange almond-shaped ear (Figure 13). The curvature of the hairline suggests this may be a fantasized self-portrait, one in which Picasso strove to imagine himself as “other”, as able to assume an alien identity or project an image of himself as a so-called primitive (previously he had imagined himself as a Harlequin, and later he would take on alter egos as a Minotaur and a bull). This identity seems to emerge as much from the figure’s intense inner reflection as from his external appearance. Hard-edged, chiseled planes offer contrasting, angled surfaces to the light. Yet, as in related works, the man, deep within the forest, has not found a clearing; repeated strokes of greenish-blue run across the single closed eye, further negating the possibility of external vision. Picasso left the traces of an earlier, thinner, and inclined neck at the lower right; in painting over it, he produced a thickened cone that meets the figure’s torso more frontally with a series of rough marks, thereby precluding any sense of naturalistic movement or anatomical transition.

Figure 13.

Pablo Picasso, Head of a Man, gouache on wood panel, 27 × 21.3 cm, 1908. Musée national Picasso, Paris. Photo: Adrien Didierjean. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In a related image, also in gouache on wood panel, the artist reversed the angle of the head, while further canceling the eye and its socket (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Pablo Picasso, Head of a Man, gouache on wood panel, 27 × 21 cm, 1908. Private collection. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Dark strokes descend from the man’s left eye, just as they would in a drawing of Picasso’s own head from 1908.20 Other male heads, also executed on wood, explore various angles and conditions of illumination, but retain the close-cropped, curved hair line, the harshly defined planes that evoke rough-hewn wood, and the closed eyes that intimate a sense of withdrawal from the external world in favor of inward awareness.

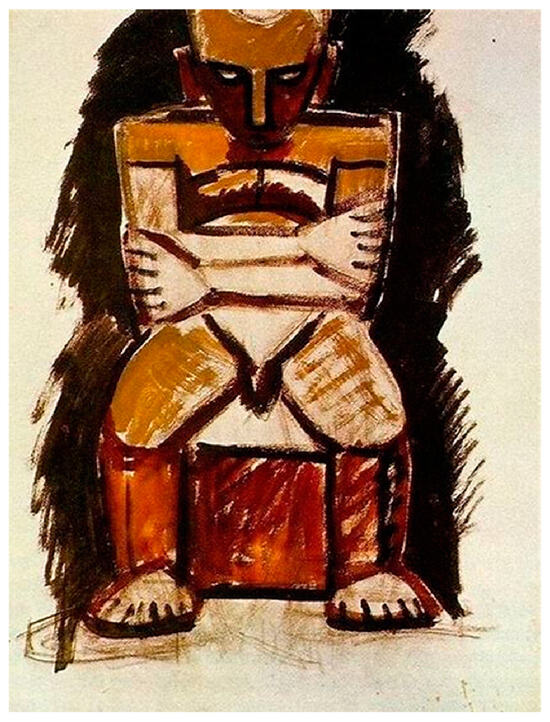

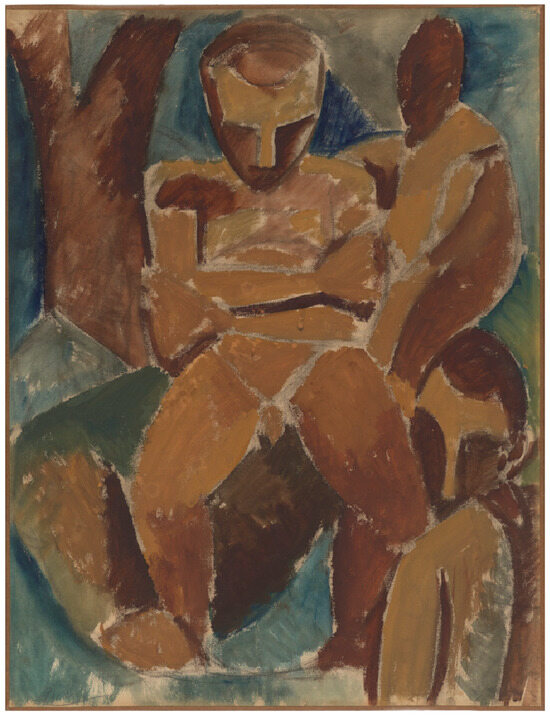

Some of these heads are closely related to studies on paper that imagine male figures in both interior and forest settings. Head of a Man, which presents the figure as seated on a chair, for example, has been associated with a drawing in charcoal, gouache, and ink of a man sitting on a box-like structure, head down, arms folded across his chest, legs apart (Figure 15). Is he resting on a box like those that academic models often sat on while posing, or is this seat in an implied brothel? His frontal posture projects a sense of contained energy, in part through the contrast between his tightly self-sealing, nearly rectangular upper body, which signals an attitude of self-protection or vehement refusal, and his exposed lower body that calls attention to his sexuality and masculine power.

Figure 15.

Pablo Picasso, Seated Man, charcoal, gouache and India ink on paper, 62.8 × 48 cm, spring 1908. Musée national Picasso, Paris. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Another sketch, executed in charcoal in even greater close-up, further abstracts the figure’s hands and ears and emphasizes the rectangle formed by his chest and arms, but adds pubic hair, chest hair, and eyelashes, perhaps to de-sublimate the increasingly schematized forms (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Pablo Picasso, Seated Nude, charcoal and graphite on white laid paper, 63.2 × 47.9 cm, 1908. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Scofield Thayer. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

However, the geometric rendering of the torso and arms works in concert with, rather than in opposition to, other signs of virility, such as body hair and exposed genitalia. A more elaborated version puts this figure, now multiplied, into a forest setting (Figure 17). Instead of a box, the man with the downward tilted head and crossed arms now sits on a log. Picasso rendered him and his two companions, who appear on the right side of the gouache and who were the subject of the related studies as we have seen, in the same ochers, browns, and beiges of their wooded milieu. Their abstracted forms seem almost interchangeable with those of the trees in their vicinity.

Figure 17.

Pablo Picasso, Three Men, gouache on paper, 63.5 × 48 cm, 1908. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter C. Arensberg Collection. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Studies for Head of a Man of 1908, in gouache, blue ink, and graphite on paper, offers an image of the same man seen twice, enveloped in a forest surround, with brown tree trunks and hints of foliage (Figure 18). The intense blue coloring that pervades the faces and parts of the background might be read as evocations of sky or water. It is if the men were made not only of wood, but of the primary elements that surround them, in particular, earth, sky, and/or water. Within the shadowy realm of the forest, which lies temporally before and geographically outside the bounded, sunlit spaces of civilization, these elements instantiate the unity of primal substance, despite the forms it might assume; as such, they could mingle and transform from one to the other in a constant play of metamorphosis. Indeed, as they preexist the advent of form, logos, and the law, these elements could not even be named or distinguished. Here we might recall that the word “forest” comes from the Latin foris, signifying that which lies outside.

Figure 18.

Pablo Picasso, Studies for Head of a Man, gouache and pen and blue ink with graphite on paper, 31 × 24.4 cm, spring 1908. Davis Museum, Wellesley College, Wellesley MA. Photo: Davis Museum at Wellesley College/Art Resource. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Or perhaps this man, multiplied, is simply a bather, but Picasso does not provide him with an appropriate setting or relevant attributes, such as the alternately small scraps or voluminous folds of fabric that Cézanne gave to his often waterless bathers. In creating this series, Picasso seems to have been thinking of a larger, multi-figure composition, a male companion to his Five Bathers, but that work never materialized.

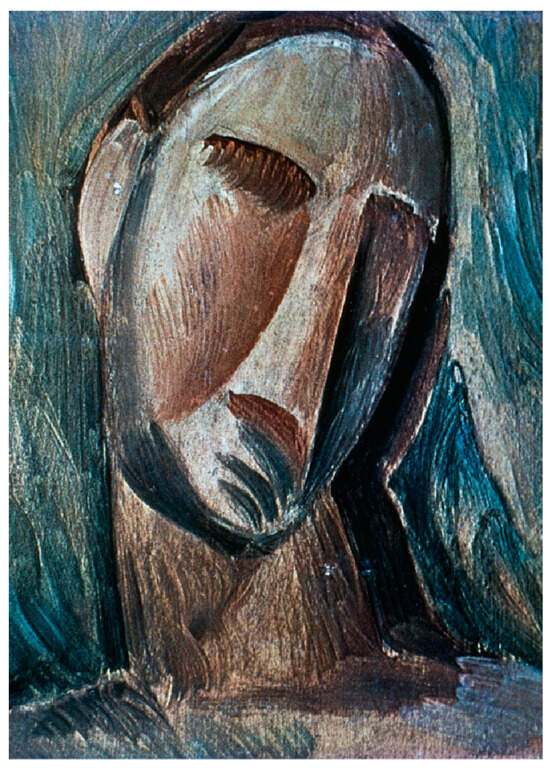

We can trace a similar movement from interior environment to forest scene in a sequence of female figures in the spring of 1908. Several heads rendered in gouache on wood explore the same “primitivizing” formal vocabulary found in the male heads. In Head of a Woman, a gouache on wood executed on the same size panel as several of the male heads, Picasso defined the figure’s visage and falling hair through a series of elemental, abstracted, and reconfigured shapes (Figure 19). He indicated the mouth through some hastily rendered marks and sheared off part of the chin. The sharp angle in the woman’s hair follows that of her profile and neck at right but does little to enhance a sense of the curvature or volume of a head that remains mask-like; instead, the dark hair functions to thicken the neck, by restating its outline. A forest, intimated through green and brown linear patterns, surrounds the woman, casting some of its coloring onto her face. The figure and her environment partly interpenetrate, as parallel striations cut through the gouache with what appears to be the sharp end of a palette knife or chisel, as if they were cutting into wood. The neck, in particular, suggests a gnarled trunk rising from the curve of the shoulders, while dark brown strokes across the eyes deny the possibility of external vision.

Figure 19.

Pablo Picasso, Head of a Woman, gouache on wood, 27 × 21 cm, spring 1908. Private Collection. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

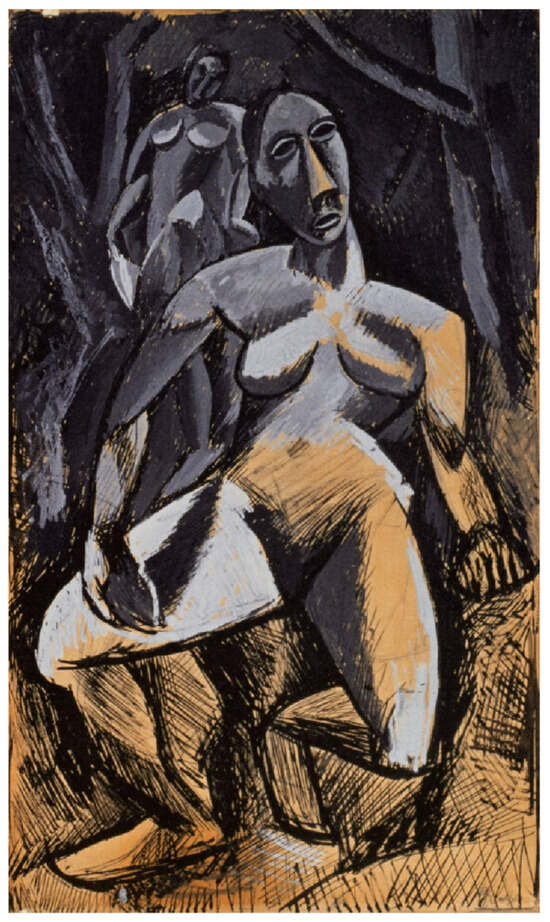

Head of a Woman is closely related to a gouache and ink sketch of two nude women in a forest (Figure 20). In this sketch, the foreground figure strides aggressively toward the viewer, legs apart in a brazen, anti-classical pose; her left arm descends in broken, facetted volumes to a clenched fist signifying refusal, whereas her right arm describes a continuous arc to conclude in an open hand that gestures toward her crotch, as if issuing an invitation or pointing to her exposed sex as evidence of her biological destiny.

Figure 20.

Pablo Picasso, Study for Nude in the Forest (Dryad), gouache and ink on paper, 63 × 36 cm, 1908. Private Collection. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Like the male figure seated in the forest on a log, this dryad embodies the ambivalence of desire and fear, sexual aggression and refusal. This study assumed its final, monumental shape as Nude in the Forest (Dryad) of 1908, executed in oil on canvas (Figure 21). But as Leo Steinberg has observed, a preparatory drawing presented this figure as a harlot in a brothel slouching in a tall chair, her legs splayed open. In Nude in the Forest, the artist transforms this pose of relaxed extension so that, as Steinberg puts it, “brothel revert[s] to jungle”.21 However, it was not enough to place the harlot in the forest, to suggest an atavistic return to primeval and animalistic roots; Picasso also reversed her right and left feet, rendered as solid slabs, further disarticulating her anatomy from its analogue in nature.

Figure 21.

Pablo Picasso, Nude in the Forest (Dryad), 185 × 108 cm, 1908. The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

For Steinberg, this disturbance of right and left, generally associated in Western art with masculine and feminine attributes, respectively, cannot be without significance. It evokes cross-traffic or intermixing in sexual identity, manifesting a certain hardening and “becoming-male” of a figure who is otherwise female.22 Moreover, the harsh, geometric faceting of the left arm (on our right) of the striding dryad resembles that of the left arm in Seated Male Nude of fall 1908, suggesting a tendency toward maleness in the pose of aggressive refusal as well as a broader fluidity of gender characteristics in Picasso’s work of this period.23 Related studies, such as Nude with Raised Arms, a gouache of 1908, imagine a woman in a process of becoming-animal, realized in the wild woodlands beyond civilization (Figure 22).

Figure 22.

Pablo Picasso, Nude with Raised Arms, gouache, charcoal, and black ink on paper, 32 × 25 cm, 1908. Musée national Picasso, Paris (MP 575r). Photo: Mathieu Rabeau. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

According to Steinberg, this form of regression can be understood through Nietzschean descriptions of the original chorus of satyrs, who gave birth to Greek tragedy, as “nature beings who dwell behind all civilization and preserve their identity through every change of generations and historical movement”. For Steinberg, Picasso conceived his atavistic dryads similarly; he writes of Nude with Raised Arms that she is “a jungle dweller of slumbrous vitality, she walks alone, listening to the surge of the body as her left leg metamorphoses into the hind leg of a quadruped–a hock on the reserve side of the knee”.24 If we accept this view, we may further interpret the fact that so many of Picasso’s male and female figures of this period close their eyes as a sign that they are “listening to the surge of the body”, a force that becomes audible through the unconscious rather than through engagement with the external world. As Robert Pogue Harrison has argued, in the Western imaginary, the forest–conceived as preexisting and forever beyond the polis, as outside the bounded spaces of social norms, language, morality, and the law–was a place where binaries such as male/female and human/animal could easily dissolve.25

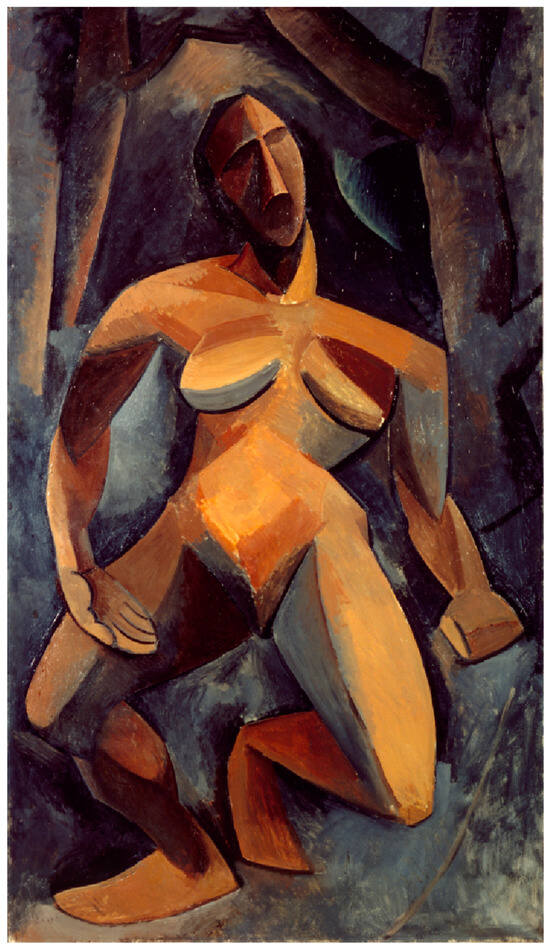

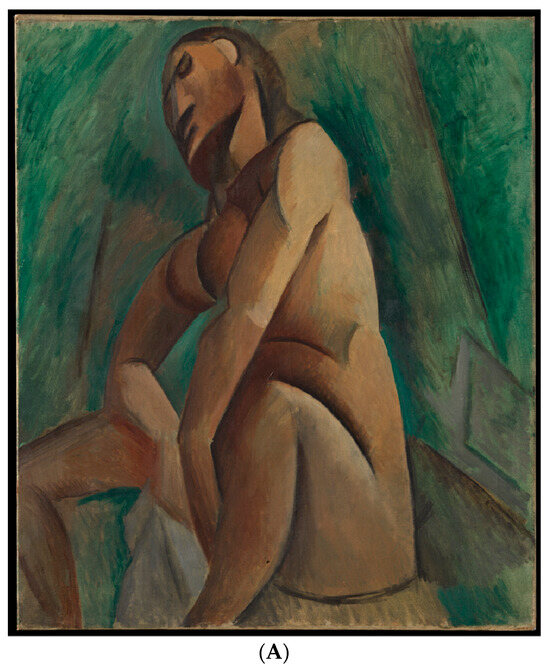

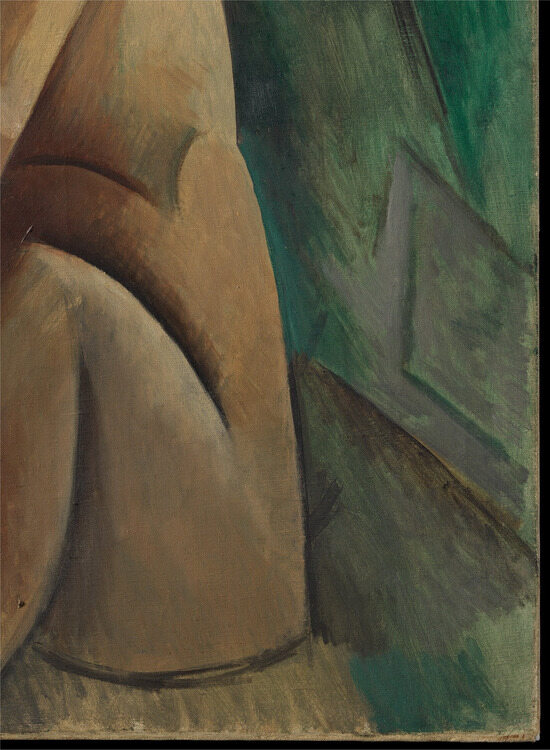

A work from winter 1908, which has received renewed attention since it was acquired by Leonard A. Lauder and given to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, stands as a culminating statement of these themes, and of the contradictions and ambiguities they bring to light. Picasso executed Seated Female Nude quickly with broad, fluid strokes for the background forest setting (Figure 23A). In contrast, the seated figure appears as if hewn from wood, as if she were a human form found within the trunk of a tree to which she still adheres, as in the Gósol wood sculptures. The artist seems to have chiseled her into existence with hard-edged contours and flat planes, such as those at the back of the proximal arm, the double curve that defines the waistline, and the geometrically rendered areas of the head and visage. Picasso further equates this nude with the substance of wood as living matter by depicting a small grey twig growing out of the lower part of her otherwise nearly straight-edged back and buttocks; a second, fainter twig appears just above it. These twigs, once seen, suggest that the nude remains a part of the living tree that rises above her (Figure 23B); she appears, then, both as a carved sculpture and as still-living wood.

Figure 23.

(A) Pablo Picasso, Seated Female Nude, oil on canvas, 73 × 60 cm, winter 1908. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Leonard A. Lauder Collection, Gift of Leonard A. Lauder. (B) Detail. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Still partly attached to the trunk of the tree, the nude tilts in parallel to its diagonal thrust along its right edge, aligning her movement with that of the tree. Although she holds a scrap of cloth between her bent and opened arms and legs, no water is in sight, and she hardly seems to be bathing. In what may be a unicum, Picasso borrowed the features of her head from those of a monumental Easter Island sculpture that was on display at the Jardin des Plantes during this period. Even though the Easter Island figure was carved from volcanic stone, Picasso transformed it into wood, while retaining its rough, “primitive”, and mysterious appearance. The oversized and ponderous head strains to the viewer’s left, eyes closed, perhaps to hear the painful “surge of the body” and the inexorable force of desire that the artist also described symbolically through her bodily posture. I pondered this curious pose for a long time before realizing that the nude bather sits so as to form a yonic shape–an emblem of a female vulva–with her outwardly bent arms and open legs. The artist emphasized the void between her arms and legs by refusing to depict the continuation of the right thigh below her arm and part of the torso beneath the breasts that he raised to the level of her shoulders. These displacements and elisions produce an implied diamond-shaped opening just above her crotch. The nude thereby both assumes a posture that signifies her female anatomy and its procreative potential and frames its implications. Whereas in ca. 1877 Cézanne had created a satirical image of the “Eternal Feminine” by placing a misshapen nude with splayed open legs within a theatrically vaginal setting, Picasso stages the yonic through both bodily posture and primitivizing associations with the forest and wood. He strives to motivate the sign, we might say, by making his female nude appear to emerge directly from the tree trunk to which she is still seemingly attached, and by having her assume a yonic shape that symbolizes a sexual identity and human desire determined by biology.

Yet the work also displays the tensions that subtend its thematic, material, and formal logic. Even as Picasso presents the seated nude as an avatar of a feminized, primitive matter, he also endows her with the newly acquired capacity for inner self-awareness and reflection. She seems made of wood, indeed of wood that may still be alive, but insofar as she is chiseled, and has a head that clearly quotes an Easter Island prototype, she also represents a sculpted work of art with a known historical lineage. Perhaps the two small, grey twigs attached to her backside are no longer living and signal her separation from the living matrix of the tree. Moreover, she dissimulates her actual medium, which is oil painting, not primitive wood carving. Although this nude assumes a yonic posture, as if to re-signify her feminine anatomy, to make it visible in the form of a corporeal hieroglyph, she seems rather uncomfortable doing so. This is an awkward, unconvincing pose that must be asserted against nature, even in defiance of nature; to achieve it Picasso had to eliminate part of her right thigh and torso, and to create a disjunction between the over-sized head and the rest of the body. This pose is a fiction that makes an ambiguous statement, perhaps one that Picasso had begun to doubt. Like his contemporary Freud, Picasso had begun to ponder the relation of anatomy to psychic desire, and to understand the latter as a force impinging from within rather than as marked on the body in legible forms. He may have begun to wonder how he could express the inner surge of desire, its unconscious source and mystery, in ways that did not materialize in signs of anatomical difference.

As Picasso began to collaborate ever more closely with Georges Braque during the winter of 1908-1909 in the creation of what would come to be called “analytical Cubism”, an art of intermittency that both employs and disrupts the devices of Western illusionism, the role of wood as a signifier of primordial matter inevitably diminished. Both artists reduced the role of color in their works, to focus more intensively on form and the pictorial conventions of the post-Renaissance tradition, and Picasso rarely created multi-figure compositions. Although forest scenes, inspired by the work of the self-taught artist Henri Rousseau, continued to appear during part of 1909, they were rarely inhabited by atavistic forest dwellers. Instead, the artist focused on still lifes, along with portraits and nudes. During these years Picasso and Braque continued to acquire African masks and sculptures. Eventually, Picasso came to understand African art as exemplifying a conceptual approach to expressing the real through powerful forms that do not seek to imitate visual appearances. There were intimations of this understanding of African art as early as 1907, as the artist began to redistribute anatomical elements such as ears, eyes, noses, and mouths on flattened, masklike surfaces without reference to an internal skeletal core; an ear might move inward to encroach on an eye or eyebrow, or a mouth might appear as an oval or rectangle interchangeably.

By spring 1912, when Braque began to employ a house decorator’s comb to create quick simulations of woodgrain that required little skill, the tables had turned. Picasso responded by using the housepainter’s comb to portray the mustache and hair of a man, in a satirical gesture that established visual analogies out of faux woodgrain with no pretense of an underlying motivation.26 Later, in the fall 1912, Braque purchased some woodgrain wallpaper and used it in a papier collé, Fruitdish and Glass, to signify the wood paneling in a room, as well as the wood drawer of the still life table, thereby confounding spatial relations of foreground and background. But in these examples, the wallpaper is clearly mechanically produced; it mimics the look and placement of woodgrain effects Braque had achieved with a decorator’s comb in earlier still lifes such as The Fruitdish in a meta-play of signifiers. If such works engage notions of truth and illusionism and set the mechanically produced and hand drawn against one another, they do not seduce the viewer into thinking they are actual wood. Instead, they employ trompe l’oeil devices against themselves, by quoting them only episodically, and never with an intent to fool the eye.

At the same time, there is no interest in treating wood as a primordial, ur-material, or one associated with the emergence of sexuality or forest dwellers. In the Cubism of 1912 and beyond, wood appears in the form of a thin, fabricated veneer, rendered in oil paint through the housepainter’s comb or via the reproductive technologies of wallpaper. As such it participates in a broader concern of the artists at this time with the rise of mechanically produced, cheap substitutes for works that had traditionally required artisanal or artistic labor. The appearance of faux woodgrain thereby questions the continuing relevance of craft and skill as they pertain to art making. Picasso’s first collage, The Still Life with Chair Caning of April 1912, displayed a piece of trompe l’oeil oil cloth, mechanically printed with a chair caning pattern. The artist framed this oval work, which simulates a table uprighted to the wall, with a mariner’s rope that substitutes for a carved and gilded frame. Here too, the comparatively cheap object, one the artist did not make, stands in for the venerable fine art frame. When wood reappears, it is similarly under the guise of the substitute, the surrogate, the false, the thin veneer, rather than as a primal material that represents timeless matter in a state of passive potentiality.

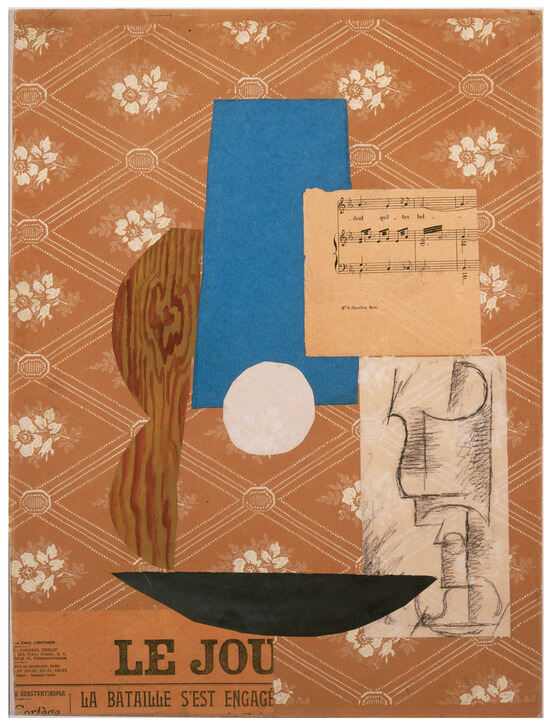

Unlike Braque, who initially tended to use woodgrain wallpaper and painted trompe l’oeil woodgrain to signify wood (or wood paneling),27 Picasso used woodgrain in a variety of ways, often calling attention to the disjunction between the painted or pasted collage material and the substance it was meant to signify, or woodgrain might appear as merely one of a diversity of elements that constellate the image of an object. In Guitar and Wineglass, an early collage of 1912, Picasso pasted a piece of paper, hand painted with a trompe l’oeil woodgrain pattern, to the left side of a guitar where it stands for the distinctive shape and materiality of the guitar, two of its attributes (Figure 24). But to undermine any sense of one-to-one veracity, he made the top curve swell out of proportion to the lower curve that should be larger. The woodgrain seems to caricature trompe l’oeil as a device as much as it does wood and it is quickly unmasked as paint. Only one of several, disparate elements that collectively constitute the shape and materiality of the guitar, it relies on other elements to define its right profile, fingerboard, scroll, and so forth. The straight-edged right profile emerges from two stacked elements: a square piece of a musical score at the top, and a longer rectangle with a drawn Cubist glass at the bottom. The work asks us to consider the play of oppositions between simulated woodgrain, machine printed musical score, and hand drawn glass, as well as the formal equivalence of a curved and straight-edged profile. In this complex pictorial context, woodgrain serves as a merely contingent marker of one of the guitar’s predicates but in a manner that says: “this is not wood”.

Figure 24.

Pablo Picasso, Guitar and Wineglass, pasted papers, gouache, and charcoal on paper, 47.9 × 37.5 cm, autumn 1912. Marion Koogler McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, Texas. Bequest of Marion Koogler McNay. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

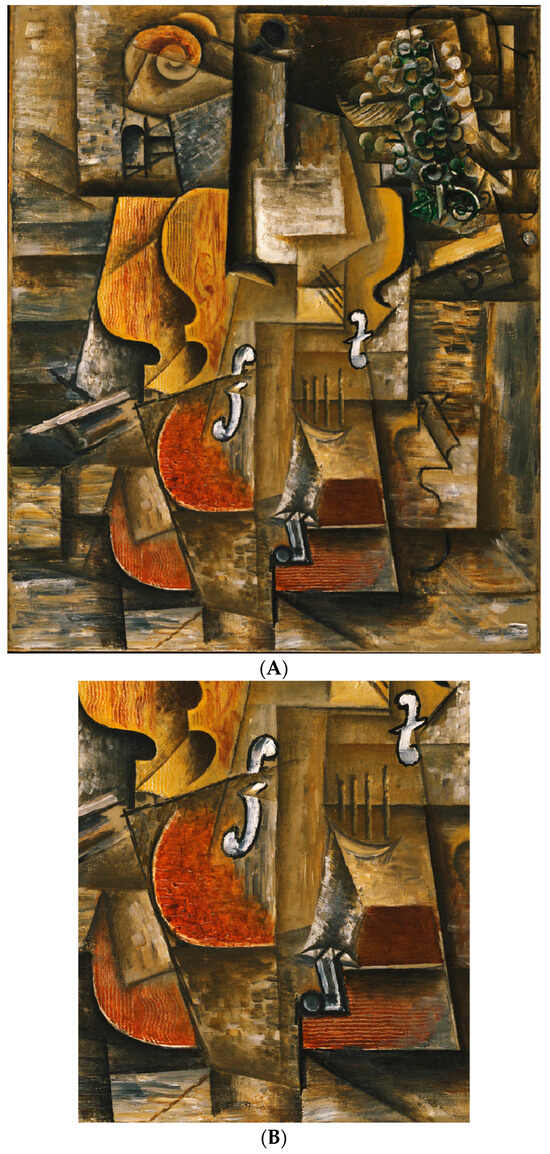

In Violin and Grapes, also of 1912, Picasso employs a variety of differently oriented and colored areas of woodgrain to call attention to its fictional status (Figure 25A,B).28 He offers a remarkable display of painterly effects at the top left, allowing the loosely rendered, almost fluid imitation woodgrain to fade into shadow, or simply to bleed into the blank ground; at the upper left the smooth woodgrain is interrupted by a strange diagonal ridge that casts a shadow where we know no real volume exists. As the body of the violin continues below the sound holes, it acquires a warm reddish tonality delivered in loaded patches of oil paint that highlight their own viscosity.

Figure 25.

(A) Pablo Picasso, Violin and Grapes, oil on canvas, 61 × 50.8 cm, 1914. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Mrs. David M. Levy Bequest. (B) Detail. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

This shift in tonality and texture puts the local color of the trompe l’oeil woodgrain in doubt. Just below this area lies a form, curved at the left, straight edged at the right, that represents both the lower curved profile of the violin at the left, and the table on which the violin rests at the right. The vertically oriented woodgrain pattern at the left, which contrasts with the horizontal disposition of woodgrain at the right, also hints at a shift in reference. Yet on both sides of this form, the woodgrain encounters an interruption that denies its truth value; at the right it runs aground before it reaches the edge of the drawn profile that contains it, and at left, it wavers between vertical striations at the far left, a blank area, and then wavy striations. This is a subtle play with the house painter’s comb to undermine rather than convince the viewer of the trompe l’oeil effect.

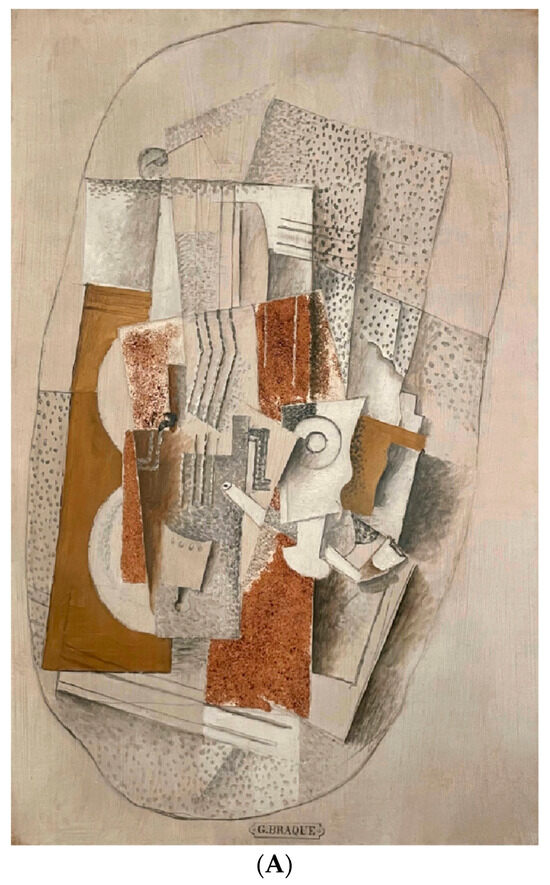

In the course of 1913 and 1914, both Picasso and Braque began to use wood and woodgrain in increasingly self-reflexive and contradictory ways. In The Violin of 1914, a work that includes several trompe l’oeil and faux trompe l’oeil devices, Braque added wood particles and sawdust to areas of the canvas that appear to have pasted faux bois collage elements (Figure 26A,B). These wood particles produce real textural effects, but they are not those typically associated with woodgrain.

Figure 26.

(A) Georges Braque, Violin, oil, sawdust and wood particles on canvas, 92.1 × 60 cm, 1914. Private Collection. (B) Detail. © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

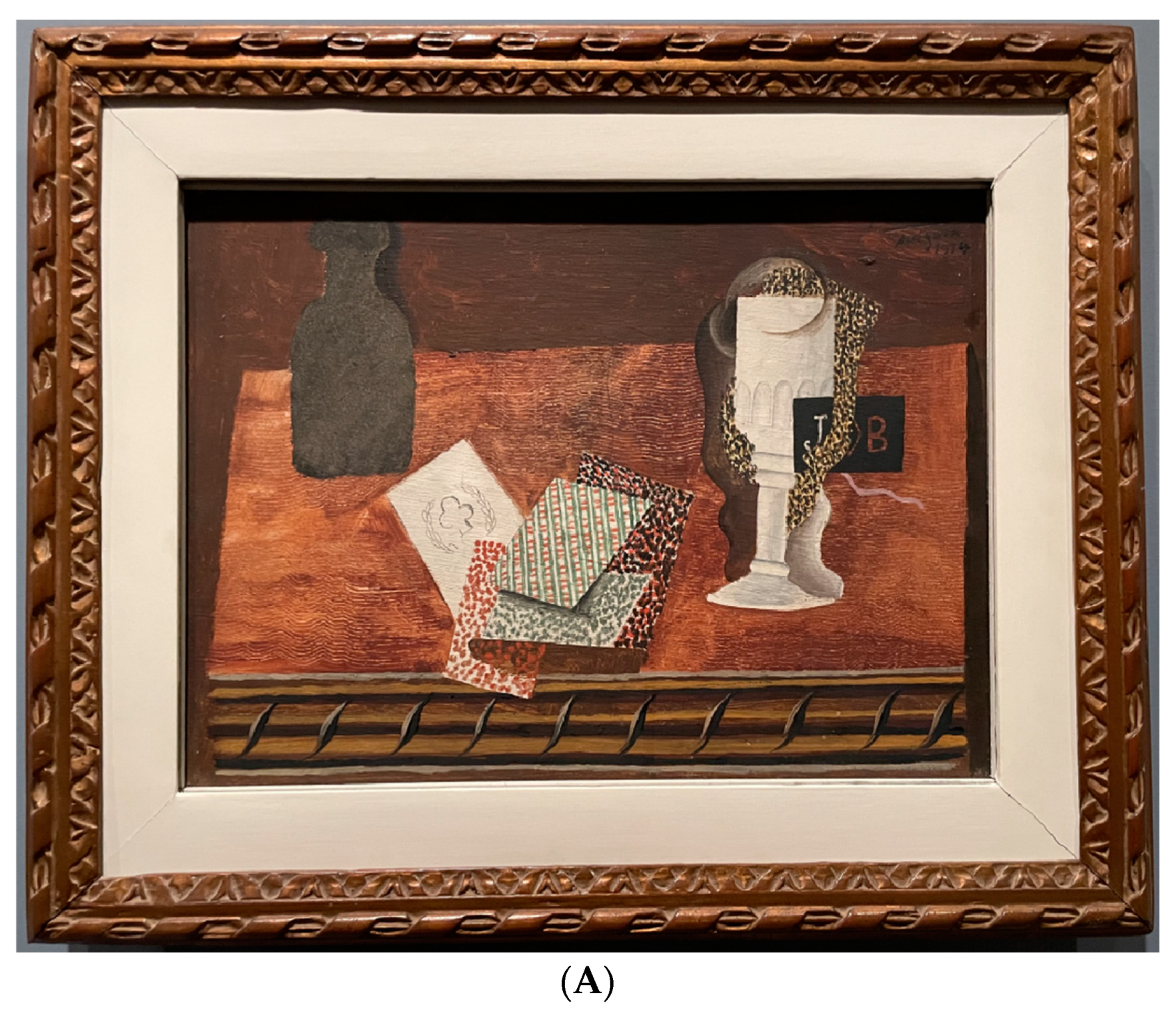

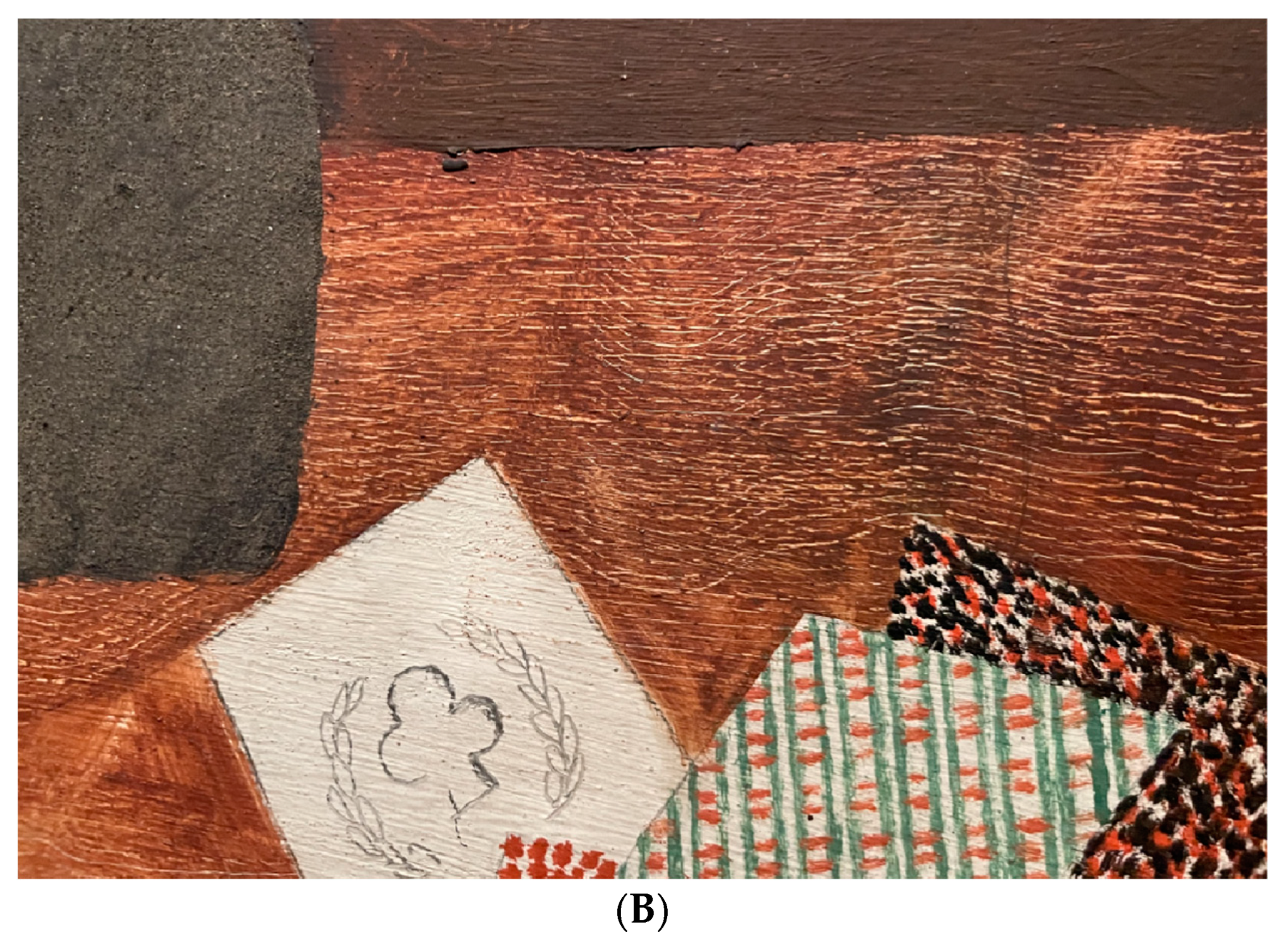

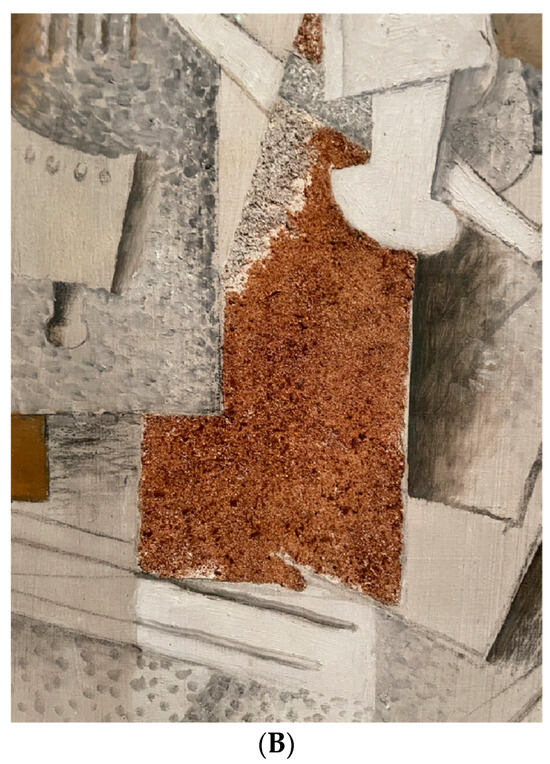

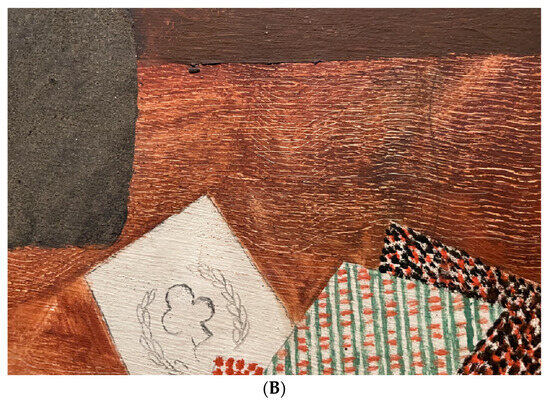

Similarly, in Picasso’s Still Life with Bottle, Playing Cards, and a Wineglass on a Table of 1914, the artist painted a simulated tabletop in faux bois over the wooden panel that is the literal support for this work (Figure 27A,B).

Figure 27.

(A) Pablo Picasso, Still Life with Bottle, Playing Cards, and a Wineglass on a Table, oil, sand and graphite on paperboard, mounted on cradled wood panel, 31.8 × 42.9 cm, 1914. The Philadelphia Museum of Art, A. E. Gallatin Collection. (B) Detail. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

But the faux woodgrain has a complex pattern, created by running the decorator’s comb across the surface of the depicted table more than once, thereby superimposing a wavy woodgrain over a still visible, horizontal woodgrain. This still life displays several objects familiar from this period: a bottle at the upper left, a reconfigured Cubist glass at right that is intercut with a painted label for Job tobacco papers, and a set of playing cards. Picasso arranged these objects on the uprighted tabletop, a frequent feature of works in this genre. This reorientation from the horizontal to the vertical allows the viewer to imagine a near equivalence of table surface and pictorial surface, of depicted object and work of art; the tabletop appears to float on the dark brown ground, faux woodgrain against a darker colored wood, even as its sides hint at recession into depth along divergent angles. Picasso painted the lower edge of the table to mimic a cut out pattern he had found in wallpaper, where it was used to simulate carved wood borders. Here it functions to signify both the lower edge of the table and the frame of the picture as a motif depicted within it. By imitating wallpaper that imitates carved wood molding–wallpaper that allows one to frame a wall with paper borders instead of expensive carved wood–Picasso calls attention to the rise of mechanical substitutes and deskilled forms of labor into historically artistic and decorative practices, even as he realizes their purportedly facile effects in paint. He embraces these cheap and unlikely materials, giving them a new creative status in his work, one that allows him to work on a more conceptual basis.

By this time, wood no longer instantiated a primordial material associated with a shadowy forest and its naked denizens attending to the awakening forces of sexual desire, or even the emergence of a sentient human figure from a wooden substrate. Instead, wood entered the work of art as an industrially manufactured simulation, that is, as a product of civilization. Picasso engaged these new materials and technical processes, but in surprisingly inventive ways that do not affirm a modernist attitude toward truth to materials. In this later phase of Cubism, the artist abandoned his earlier interest in seeking to align his choice of material with the value or meaning of a work of art. His understanding of African sculpture seems to have been a key catalyst in this transformation, leading him to ever greater awareness that works of art are powerful constellations of signs that need not represent the world, or human anatomy, as they are perceived by Western viewers. Instead, the work of art found its own imaginative logic, its own beauty and truth, in acknowledging the play of its conventions in mutual contradiction, and the creative agency of artists and viewers alike.

Many years later, in 1958, Picasso executed a new Head of a Man out of a mass-produced, rectilinear structure, a simple, open wooden box or crate mounted on an overturned ceramic dish (Figure 28).

Figure 28.

Pablo Picasso, Head, open wood box, nails, buttons, painted plaster and painted synthetic resin mounted on overturned ceramic dish, 50.5 × 22.2 × 20.3 cm, 1958. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Jacqueline Picasso in honor of the Museum’s continuous commitment to Pablo Picasso’s art, 1984. © 2024 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

He attached a narrow, angled strip of wood, probably cut from the lid of the box to its top edge; it represents the plane of the face and nose, with two differently colored buttons for eyes. Along the rear interior wall of the box, he added a strange, informe mass of painted plaster and resin in a vertical strip, perhaps to contest its otherwise rigid rectilinearity. This resin and plaster material provides support for the projecting pieces of wood that fix in place the angled plane of the face and nose, and the small horizontal fragment of wood that stands for the mouth. Here is a man’s head, created out of simple, prefabricated and industrially cut elements, as well as materials that defy measure and formal coherence. Together, they create a system of familiar signs made of unlikely, geometric, and form-negating elements. I take it to be an ironic self-portrait of the artist.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Picasso (1917): “Mes plus pures émotions, je les ai éprouvées dans une grande forêt d’Espagne, où à seize ans, je m’étais retire pour peindre. Mes plus grandes émotions artistiques, je les ai ressenties lorsque m’apparut soudain la sublime beauté des sculptures exécutées par les artistes anonymes de l’Afrique. Ces ouvrages d’un art religieux, passionné et rigoureusement logique sont ce que l’imagination humaine a produit de plus puissant et de plus beau. Je me hâte d’ajouter que cependant, je detest l’exotisme”. All translations are by the author unless otherwise noted. |

| 2 | Aristotle (1984). Robert Pogue Harrison points out that Aristotle is the first person to give the term “hyle” its philosophical meaning. See: (Harrison 1992, p. 28). |

| 3 | Ernst (1936), pp. 428–29. |

| 4 | Statement by Beuys and Tisdall (1979), p. 50. |

| 5 | See Note 4. |

| 6 | See Note 4. |

| 7 | On the loss of forests, (symbol of nature tout court), and of all that lay beyond the boundaries of civilization in the cultural imagination of the West, see: (Harrison 1992). |

| 8 | Geiser (1933), cat. 211, n.p. Geiser lists three works as printed in colored oil on tinted manila paper, five on letter paper including one in black oil (reproduced here, and four printed with colored gouache.) The gouache prints are reproduced in color in: Ocaña and von Tavel (1992), p. 370, ex. cat., no. 194 a-d. |

| 9 | (Palau i Fabre 1985, p. 454, cat. nos. 1269 and 1271). |

| 10 | Ibid. p. 472, cat. nos. 1358 and 1359. Many other examples could be cited, including studies for Two Nudes, 471, cat. nos. 1350 and 1354. |

| 11 | The fir block is held in the collection of the Musée Picasso, Paris (MP 3541). |

| 12 | Rosenblum (1997), p. 268. ex. cat. |

| 13 | (Palau i Fabre 1985, p. 459), catalogue nos. 1291, 1292, and 1293. Picasso executed nos. 1292 and 1293, in lead pencil and India Ink respectively, in the Catalan notebook (pages 53 and 3), whereas the closely related, larger no. 1291, is in gouache and has notations for color “if it were a painting” [“Si fuera una pintura”]. |

| 14 | Picasso (1906), pp. 442–44. |

| 15 | Brassai (1964), p. 14. |

| 16 | Freud (1927), pp. 147–57. Yve-Alain Bois called attention to the masculine, phallic postures of some of the figures in the Demoiselles d’Avignon, in (Bois 1988), pp. 135–38. |

| 17 | Steinberg (1972). A revised version appeared in October, no. 44 (Spring 1988), pp. 7–74. It has now been republished, with some further revisions, in Picasso: Selected Essays, ed. Sheila Schwartz (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), p. 98. |

| 18 | Steinberg (1972), p. 100. |

| 19 | Several sketches show Picasso exploring the posture of this “bois de Gósol” from varied angles. See Palau i Fabre 1985, note 13. Other sketches propose variants, including one in which the female figure assumes the hand position with the index and baby finger curled seen in the artist’s first woodcut, Bust of a Woman. See (Wofsy 2012), vol. 259, pp. 1906–315. |

| 20 | For a discussion of the ink and charcoal drawing Head of a Man of late 1908, executed over the hieratic figure of a woman, see: (Poggi 2014), pp. 36–39. |

| 21 | Steinberg (1972), pp. 87–89. |

| 22 | Steinberg made this argument in relation to the legs and feet of a drawing for the left-hand figure in Three Women of 1908, in which he asked his readers to observe “that her wanton legs right and left are methodically interchanged, a right inner calf and right foot facing out on the left. This is no neutral shift. For the notion that dexter and sinister correspond respectively to male and female is a near-universal myth, and no wilful disturbance of these orientations can be sexually innocent; certainly not in Picasso’s imagery where only female nudes are so garbled–women bedded down or somnambulant, whose nether limbs in cross-traffic intimate sexual mix, or man-woman encounter, or a subliminal sorting out of sexuality”. (Steinberg 1978), p. 120. |

| 23 | See: Seated Man, winter 1908, in (Daix and Rosselet 1979), p. 233, no. 229. |

| 24 | Steinberg (1972), p. 103. |

| 25 | Harrison (1992), pp. 29–30 and passim. |

| 26 | See: Le Poète, in (Daix and Rosselet 1979), summer-autumn 1912, p. 284, no. 499. |

| 27 | See, for example, Georges Braque, Still Life with Guitar, 1912 (Jucker Collection, Milan), in which the artist pasted a single piece of trompe l’oeil woodgrain wallpaper onto this work that represents a guitar. Yet, Braque also negated its efficacy as a simple sign for wood by pasting the paper obliquely onto the vertically aligned guitar, and by drawing with charcoal both onto, across, and below the wallpaper, which then oscillates between the functions of figure and ground. The paper also evidently lies flat on the surface of the papier collé, while seeming to cast a shadow, making it more object-like. For a discussion of this and other papiers collés by Braque, see: (Poggi 1992), chap. 4, pp. 90–123. This work is reproduced on p. 103. |

| 28 | This work was included in The Metropolitan’s Museum of Art’s major exhibition, Cubism and the Trompe l’Oeil Tradition, organized by Emily Braun and Elizabeth Cowling. The opportunity to look closely at so many Cubist works that employ trompe l’oeil effects, and to attend to subtle differences in technique, facture, color, and texture, in relation to examples of works from American and European trompe l’oeil traditions, greatly contributed to my thinking about this topic. I am grateful to all those who provided comments on my presentation at the Scholars Day, which offered an early version of the ideas developed more fully here. For the catalogue, see: (Braun and Cowling 2022). |

References

- Aristotle. 1984. Physics. In The Complete Works of Aristotle. Edited by Jonathan Barnes. Princeton: Princeton University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Beuys, Joseph, and Caroline Tisdall. 1979. Joseph Beuys. New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum/Thames and Hudson, p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Bois, Yve-Alain. 1988. Painting as Trauma. In Art in America. vol. 76, pp. 130–41, 172–73. [Google Scholar]

- Brassai. 1964. Conversations with Picasso. Originally published in French in 1964 as Conversations avec Picasso. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Emily, and Elizabeth Cowling, eds. 2022. Cubism and the Trompe l’Oeil Tradition. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Daix, Pierre, and Joan Rosselet. 1979. Le cubisme de Picasso. Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre peint 1907–1916. Neuchâtel: Éditions Ides et Calendes. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, Max. 1936. On Frottage. Originally published as “Au delà de la peinture”. In Cahiers d’art. Cited from: Herschel B. Chipp, ed. Theories of Modern Art. Translated by Dorothea Tanning. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, pp. 428–29. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, Sigmund. 1927. Fetishism. In The Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Translated by James Strachey. London: Hogarth and the Institute of Psychoanalysis, 1964, vol. 21, pp. 147–57. [Google Scholar]

- Geiser, Bernhard. 1933. Picasso: Peintre-Gravure: Catalogue illustré de l’oeuvre grave et lithographié, 1899–1931. Berne: B. Geiser. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Robert Pogue. 1992. Forests: The Shadow of Civilization. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ocaña, M. Teresa, and Hans Christoph von Tavel, eds. 1992. Picasso, 1905–1906: From the Rose Period to the Ochres of Gósol. Barcelona: Museu Picasso. Bern: Kunstmuseum Bern. [Google Scholar]

- Palau i Fabre, Josep. 1985. Picasso: The Early Years, 1881–1907. Translated by Kenneth Lyons. Barcelona: Ediciones Polígrafa. [Google Scholar]

- Picasso, Pablo. 1906. Letters to Enric Casanovas. Cited in John Richardson, with Marilyn McCully. A Life of Picasso, 1881–1906. New York: Random House, 1991, pp. 442–44. [Google Scholar]

- Picasso, Pablo. 1917. Propos de Picasso. In Picasso/Apollinaire: Correspondance. Edited by Pierre Caizergues and Hélène Seckel. Translated by Christine Poggi. Paris: Éditions Gallimard/Réunion des Musées nationaux, pp. 201–3. [Google Scholar]

- Poggi, Christine. 1992. In Defiance of Painting: Cubism, Futurism, and the Invention of Collage. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Poggi, Christine. 2014. Double Exposures: Picasso, Drawing, and the Masking of Gender, 1906–1908. In Cubism: The Leonard A. Lauder Collection. Edited by Emily Braun and Rebecca Rabinow. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 28–39, 302–3. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum, Robert. 1997. Picasso in Gósol: The Calm before the Storm. In Picasso: The Early Years, 1892–1906. Edited by Marilyn McCully. Washington: National Gallery of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, Leo. 1972. The Philosophical Brothel. In Art News. vol. 71. pp. 2–9, 38–47. A revised version appeared in October. No. 44. Spring 1988. pp. 7–74. Cited here from the new edition of Steinberg’s essays on Picasso. Edited by Sheila Schwartz. Picasso: Selected Essays, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022, pp. 71–116, 211–18. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, Leo. 1978. Resisting Cézanne: Picasso’s ‘Three Women’. In Art in America. [Part I]. pp. 115–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wofsy, Alan. 2012. Picasso’s Paintings, Watercolors, Drawings and Sculpture: A Comprehensive Illustrated Catalogue, 1885–1973, The Rose Period–1906: Paris, Holland and Gósol. The Picasso Project. San Franciso: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).