Abstract

The wall paintings from the site of Akrotiri, Thera, are often considered to be instrumental to understanding elements of life in the Bronze Age. This is partially due to their high degree of preservation. The large-scale detail present in the scenes allows for a more detailed and nuanced understanding of the imagery that survives in glyptic art that, considered together with the surviving wall paintings, helps to better inform one’s understanding of Aegean life. Many of the iconographic elements and themes, however, remain at least partially enigmatic. This is particularly the case for Xeste 3, a cultic building at Akortiri, where the wall paintings contribute to a larger, programmatic cultic narrative. The current investigation seeks to better understand the monkeys scene from Room 2 of the first floor by deconstructing and examining each visual element via comparative analyses. They are first contextualized within the Aegean, then considered in light of Mesopotamian comparanda. This method allows for possible parallels between the monkeys from Xeste 3 and at least three priestly classes known from contemporary Mesopotamian tradition: the gala, assinnu, and kurgarrû. Each of these priestly classes belonged to the adaptable and widespread cult of Inanna, one of the most powerful and popular deities in Mesopotamia.

Keywords:

religion; Aegean; Mesopotamia; mythology; bronze age; iconography; archaeology; animal; exchange; silk roads 1. Introduction

The Bronze Age (ca. 3000–1170 BCE) wall paintings from the site of Akrotiri on the Aegean Island of Thera are often regarded as expressing the height of Bronze Age Aegean art, due, in part, to their preservation, but also because of the large-scale detail and iconographic themes they depict.1 Many of these themes, however, remain only partially understood. Without accompanying decipherable writing, the interpretation of the nuanced meanings and associations of the preserved imagery becomes daunting. This remains the case even within the confines of the single, often-discussed building of Xeste 3, where the wall paintings seem to contribute to a larger cultic narrative. Nevertheless, countless scholars continue to grapple with both the building’s connected program and individual panels. The current investigation seeks to better understand a single scene within the building’s broader context: the monkeys scene from Room 2 on the first floor. By reading this scene as not only associated but intertwined with the activities depicted in adjoining Room 3a, a more nuanced reading of the imagery becomes possible. By employing somewhat traditional comparative methodologies within the much-expanded corpus of excavated and published material—both in the Aegean and in nearby regions—possible parallels emerge between the monkeys from Xeste 3 and at least three priestly classes known from contemporary Mesopotamian tradition: the gala, assinnu, and kurgarrû. This possible parallel is explored by first situating the Late Bronze Age wall painting within the broader context of Afro-Eurasian exchange, before revisiting the ways in which multifaceted evidence of an Aegean connection survives from the Mesopotamian site of Mari. Such relations form a critical foundation for the strong possibility of the intentionally syncretic and/or polyvalent imagery seen in Xeste 3—particularly the image of the seated Potnia. It is within this context that the image of the monkeys is first dissected: each visual element is examined and considered within the broader Aegean, before they are reunited and collectively compared to potential parallels from Mesopotamia. Excavated remains, contemporary written sources, and iconography are interwoven as key evidence for this possible transregional relationship between the Aegean and Mesopotamia.

2. Intricate Interconnections

In the quickly growing study of Bronze Age Afro-Eurasian exchange, ample evidence continues to emerge that shows the high degree of interconnectivity amongst the Mediterranean, Egypt, Levant, Mesopotamia, and the areas beyond, including but not limited to Scandinavia, the British Isles, the Indus River Valley, and Southeast Asia.2 Various types of evidence survive that attest to these strong interconnections: raw materials (largely inorganic), iconography, motifs and artistic styles, technologies and workshop practices, textual documentation, and information rendered via scientific analysis. Considering the networks linking such far-flung places, it is perhaps unsurprising that neighboring regions may have had closer and more frequent contact with one another than initially suspected. Such relationships between these areas—for instance, the Aegean and Mesopotamia—are acknowledged and yet in many ways remain unexplored (Figure 1)3.

Figure 1.

Map of the Aegean, Levant, and Mesopotamia. Adapted by Marie N. Pareja from Google Earth.

The presence of ‘Aegean-style’ wall paintings in the Near East is sometimes considered an attestation of the desirability of the decorative architectural products created by unique, highly specialized Aegean craftspeople, and yet others believe that the same wall paintings are indicative of independent, Near Eastern traditions (Koehl 2013, pp. 170–79; Winter 2000, pp. 750–51). ‘Aegean-style’ wall paintings are known from the Middle and Late Bronze Age sites of Tell el Dabca and, later, Malqata in Egypt, as well as Alalakh, Tel el-Burak,4 Mari, Qatna, and Tell Kabri (Brysbaert 2008, pp. 7–14; Becker et al. 2018). Of particular interest is a painting from Mari,5 where the composition, content, artistic style, and production technologies serve as strong parallels for lime plaster wall paintings from Knossos, Crete, and Akrotiri, Thera.

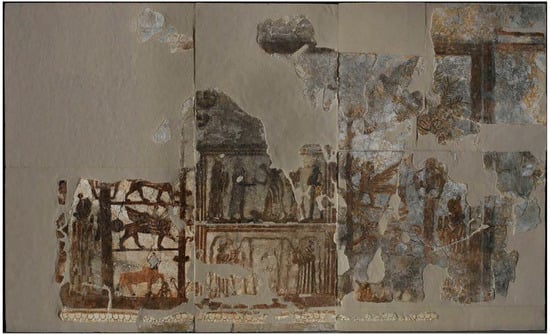

3. The Investiture Scene at Mari

The Bronze Age palace at Mari (2900–1759 BCE) is located along the western bank of the Euphrates River in modern-day Syria, and the settlement served as a center for trade between Sumer to the southeast and the Levant and Anatolia to the northwest. The Investiture of Zimri-Lim scene (2.4 × 1.8 m) was painted at the height of the Lim dynasty, and it originally decorated the south wall of Inner Court 106, ‘The Court of the Palm,’ which is west of the recessed doorway that leads to the palace’s throne room (ca. 1776 BCE; Figure 2; al-Khalesi 1978, pp. 37–69; Bradshaw and Head 2012, pp. 3–10, figs 2–3; Devries 2006, p. 27; Frayne 1990, p. 606; Hamblin 2006, p. 258; Margueron 2014). The scene is composed symmetrically, with a structure in the center that shows (a part of) the palace in which the painting was found. The central architecture is framed by supernatural creatures, palm trees, and perhaps poles.6 In the upper room depicted in the wall painting7, Zimri-Lim ascends to kingship as he reaches with one hand for the rod-and-ring8 and holds the other hand to his mouth in a gesture of prayer and reverence.9 Ištar, the Akkadian theonym for the Sumerian Inanna10, hands the rod-and-ring to the new king while holding a sword in her other hand, with the hilts of several weapons visible above her shoulders. Lamassu, minor goddesses wearing horned headdresses, flank Ištar and Zimri-Lim. Ninshubur, mythical handmaiden to Ištar, stands behind her goddess. In the room depicted below, two figures (Lamassu again) hold vessels from which plants sprout and liquid flows in several directions, symbolizing the impending prosperity and abundance of Zimri-Lim’s reign.

Figure 2.

Investiture of Zimri-Lim from Mari. 2000–1800 BCE. Lime plaster and pigment. AO 19826. Image courtesy of Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Various figures are depicted outside the central palatial structure, together with palm trees and an unidentifiable (perhaps mythical) tree.11 Supernatural creatures appear amongst the tree branches, including at least one human-headed, front-facing bull; winged lions (representing Ištar’s aggressive, martial aspect); and a sphinx. Human figures appear to the climb the palm trees, perhaps to pick fruit. Oversized Lamassu stand at the outermost corners of the garden with their hands raised in prayer. Finally, flying doves are also depicted, which represent the peaceful aspect of Ištar. The centrality of Ištar to Mari and Zimri-Lim himself is apparent in the preserved iconography, which is further supported by various texts, including those preserved at Mari from Hammurabi’s later invasion.12 The wall painting itself is fragmentary, although enough of the surface remains to indicate strong parallels with lime plaster wall paintings from the Aegean islands.

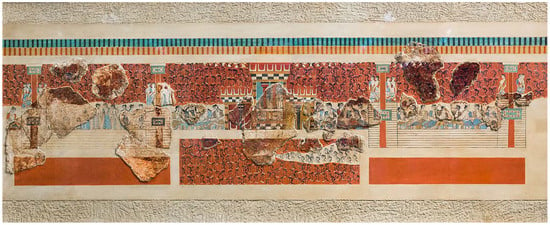

First among these similarities to Aegean artwork is the focus on a particular location within the palace as the subject of this image. The Grandstand Fresco from Knossos, Crete (Figure 3), for instance, serves as an artistic parallel (Evans 1930, p. 46 ff.). In this miniature wall painting, female figures are seated together in the central court space at Knossos, as indicated by the depiction of the tripartite shrine at the center of the image. Although differing in dimension, both scenes flaunt a symmetrical arrangement of characters around a specific, significant central architectural structure. Additionally, the painting was recovered in the very structure that it depicted, as at Mari. In composition, arrangement, chronology, the association between depiction and original location, and even artistic production technology, these two wall paintings may serve as parallels for the purpose of this discussion. Nevertheless, the scene from Mari possesses two elements that, at times, seem to be perpetually elusive—conspicuously lacking—from Aegean iconography: a clear illustration of deity and ruler.

Figure 3.

Reconstruction of the Grandstand Fresco from Knossos, Crete. Middle Minoan III–Late Minoan IA (1600–1450 BCE). Lime plaster and pigment. Watercolor painting by Emile Gilliéron. Early 20th century. Image courtesy of Harvard Art Museum. Website: https://hvrd.art/o/291769 (accessed on 23 November 2023).

4. A Polyvalent Potnia?

One of the lingering questions that plagues Aegean iconographic studies relates to the understanding of figural imagery. Currently, visual elements are capable of being identified (axe, male figure, crocus stamen), but many of the second- and third-order layers of identity and interpretation remain elusive (leader, acolyte, ruler, mother, priestess, goddess). The same is true of depicted actions. Although sometimes it is enough to identify a male figure performing a particular action, such as interacting with a tree (e.g., CMS I 219)13, a more nuanced reading of such imagery remains tenuous without the ability to properly contextualize the visual elements within a larger system. For instance, a more thorough understanding of the social and iconographic system is required to distinguish between an individual grasping the branches of a tree, beginning to climb a tree, or shaking a tree (second order). The cultural/social implications of this action could range from admiration to blessing, from harvest to begging, and from playfully carefree to intensely focused and sacred (third order). The contextualization of the action helps with more accurate identification of the figure performing it (goddess, queen, priestess, worshipper, participant, or an individual who is simply present, for instance) and the circumstances around it (religious event, ritual, or regular occurrence). The crux of this problem is that the greater system(s) within which Aegean peoples functioned remains obscure.

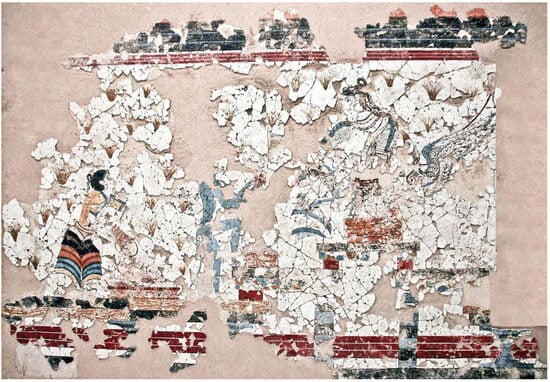

The types of religious and political systems present in the Aegean remain debated, particularly due to the lack of consistency between Linear B texts, archaeological evidence, and iconography.14 The question of rulership often seems secondary to matters of religious structure, and scholarship frequently appears to assume that for the Aegean, as for its neighboring cultures, the two were intertwined.15 Monotheistic (Peatfield 2000; Morris 2006), polytheistic (Marinatos 1993, 1996, 2010), shamanic (Tully and Crooks 2015; Crooks et al. 2016), and animist systems (Herva 2006; Tully and Crooks 2015; Wyatt 2008) have been proposed, sometimes as intentional, singular systems and sometimes as overlapping, interwoven ways of life. Some scholars advocate for a single and central Mother Goddess figure (Figure 4) due to the iconographic abundance of nature, (mortal?) human women, and floral imagery, together with the relatively infrequent depiction of male figures.16 Others propose that the gods within the pantheon from Linear B texts simply cannot yet be distinguished from one another in art. Among those who favor the existence and/or depiction of (a) deity(/ies), yet another division appears: some favor identifying some images/concepts as Potnia (Kopaka 2001; Vlachopoulos 2021)17, while others do not. The argument for shamanism and/or animism eliminates the need to distinguish between named gods in favor of emphasizing the depictions of figures amongst a natural, animated world. Alternatively, some advocate for an abdication of specific labels for the often-oversized figures that many consider deities: Janice Crowley, for instance, aptly observes that speculation inevitably bleeds into interpretation or theories that engage virtually any label more specific than VIP (Very Important Person; Crowley 2008).

Figure 4.

Offering to the Seated Goddess Wall Painting. Late Cycladic IA Period (1620–1500 BCE). Lime plaster and pigment. Adapted by M.N. Pareja from Doumas 158–59, fig. 122.

Another option has recently been suggested. Perhaps the iconography and cult paraphernalia from the Aegean are consistently, intentionally vague—a one-size-fits-all, syncretic set of imagery that welcomes a variety of traditions and beliefs, particularly those with an emphasis on the divine feminine (Blakolmer 2018, p. 179; Pareja 2023b). The theory also topically explores strong similarities in the organization of cultic space, attributes, worshippers and acolytes, polyvalence, and paradoxical duality between the Aegean Potnia and Sumerian Inanna (Akkadian Ištar), arguing for a possible parallel identity between them (Pareja 2023b, pp. 104–8). This comparison is not necessarily limited to only these two figures, however, as a key advantage of such a system lies in its iconographic and ideological malleability and permeability—its deeply adaptable, syncretic nature. This alternate framework, together with comparative approaches, serves as the foundation for reconsidering the ways in which some animals depicted on the walls of Xeste 3 at Akrotiri, Thera, might share actions and attributes with acolytes, worshippers, and perhaps even mythical characters, in a manner similar to some animal depictions in Mesopotamian traditions.18

5. Allegorical Animals

Although it is not unusual for animals to be employed symbolically in prehistoric or modern contexts—which lends further credence to Vlachopoulos’ assertion that the animals from Xeste 3 are, in fact, symbolic acolytes of sorts—both texts and material culture illustrate a focused tradition of not only anthropomorphosis, but of animals embodying human archetypes or social roles.19 Consider that Aesop’s Fables (Aesopica) are a written culmination of various longstanding oral traditions that may be rooted in Sumer and Akkad as early as the third millennium BCE (Priest 1985, pp. 49–58).20 This allegorical treatment of animals can be spotted in written and material culture. For instance, artifacts recovered from the Royal Tombs at Ur show animals performing the roles of priests or attendants. Of particular interest is the bull-headed lyre and the iconography found on the front-facing plane of its soundbox.

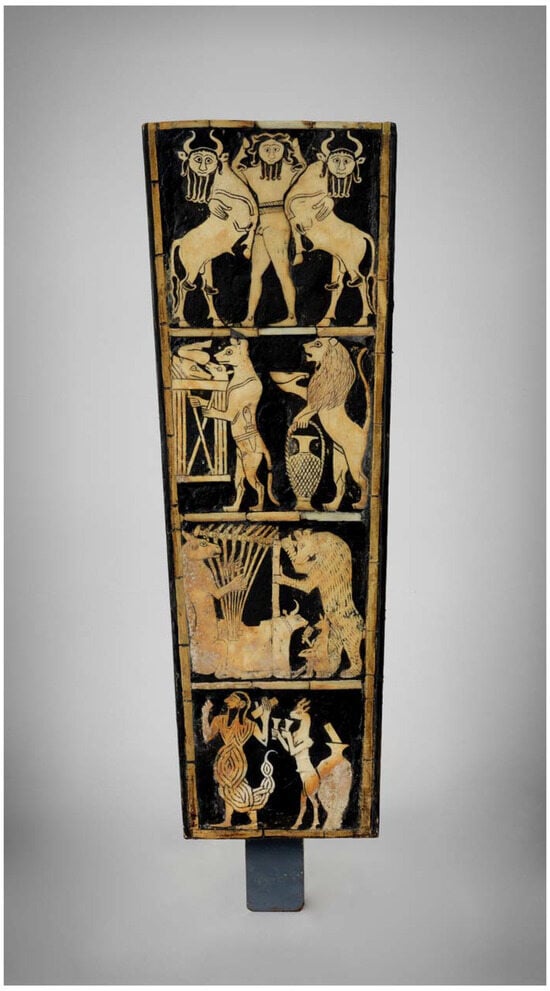

The front panel of the bull-headed lyre, recovered from The King’s Grave from the Royal Tombs at Ur (Early Dynastic III; 2550–2450 BCE), shows anthropomimetic and anthropomorphized animals—some natural and some supernatural—in four vertical registers (Figure 5; de Schauensee 2002, p. 63). Each of these figures appears to engage in different phases of a funerary ritual, including games (wrestling/grappling), food preparation/sacrifice, feasting, the playing of musical instruments (including the bull-headed lyre), and the final meeting of the deceased with the scorpion man at the entrance of the underworld (Scurlock 2021, p. 419).

Figure 5.

Front Panel of Bull-Headed Lyre. 2450 BCE. Shell and bitumen. B17694A. Courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

When considered together with this imagery, the notion that Vlachopoulos puts forth of animals serving as acolytes is remarkably familiar from most (if not all) other regions of Bronze Age Afro-Eurasia, and yet such overtly depicted human-like behavior by animals does not typically appear for any real-world creatures in Aegean artwork except for monkeys (due perhaps, in part, to the primate physique and mental acuity). A vital distinction between these visual traditions may suggest an underlying difference in the intention and interpretation of these images: the figures shown on the lyre clearly perform human actions in human ways, despite each creature’s lack of suitable morphology, while the animals in Aegean artwork are shown moving and behaving in accordance with both nature and morphology. Essentially, no goats are shown nimbly dancing on their hind legs, no lions are depicted skillfully slicing meat, and no rock doves are shown swinging necklaces from feathered fingers. Although this may simply be a matter of cultural preference, it is also possible that by rendering images of animals that are both familiar and symbolic to other cultural groups, Aegean peoples created an iconography that deliberately facilitated syncretic interpretations.

The imagery on the lyre (and other such depictions) could also/alternately indicate the use of animal costumes by cult participants, a well-documented practice in several regions during the Bronze Age. This is an aspect of cultic life that (as of yet) is not often discussed in Aegean literature, likely due to the little overt, direct evidence that survives for such practices (Foster 2016, p. 71; Krzyszkowska 2005, p. 152; Morgan 1995, pp. 173, 179).21 Nevertheless, Cyprus (Counts 2008, p. 19), ancient Egypt (Bommas and Khalifa 2019, pp. 11–27; Taylor 2013, pp. 168–89), the Near East (Russel and McGowan 2003, pp. 445–55), and Mesopotamia are each home to various festivals, rituals, and traditions in which masks and costumes—sometimes simple and sometimes quite elaborate—are worn. This is well documented in Mesopotamia, where ritual texts detail the proceedings of such events. Kings, priests, attendants, and other participants wear animal costumes (including masks, wigs, and sometimes wings) while dancing, playing music, and making animal sounds (Foster 2016, p. 72; Collins 2001; Wiggermann 1986). Priests of the goddess Inanna, for instance, ‘had a full-time job amusing this grim mistress of liminality by making a lot of noise on various instruments, donning masks, singing of warfare, dressing up as women, and dancing sword dances,’ (Scurlock 2002, p. 396). These items may have ultimately become votive offerings for gods or demigods from ritual participants post-performance (Foster 2016, p. 73). If the monkeys depicted in Xeste 3 are considered through this lens, then perhaps there are more layers—more possible associations and nuanced identities for the creatures represented on the walls of this building.

6. Animal Acolytes in Xeste 3

Xeste 3 at Akrotiri, Thera, is a cult building that was largely preserved by the Pompeii Effect when a volcano erupted during the early phase of the Late Bronze Age. The structure and its lime plaster wall paintings serve as focal points for investigations into Bronze Age life. The preservation of the large-scale wall paintings is unrivalled in the Aegean, and their proper, thorough, and highly skilled excavation, cleaning, conservation, reconstruction, and publication is key to much of what has been learned about the site of Akrotiri itself, as well as the broader Aegean.

The structure is composed of three levels, with a sunken area as part of the ground floor. The wall paintings are figural, with scenes of nature populated by animals and human figures on the ground and first floors. On the second story, repeating linear motifs of spirals and rosettes dominate the pictorial space. The male figures—possibly priests, male acolytes, or male participants, but at the very least, male figures—present in Xeste 3 belong only to the ground floor entrance, where they are depicted in possible preparatory scenes. Males are first depicted grappling with bulls and agrimi in the entrance to the structure, presumably for sacrifice (Vlachopoulos 2021, pl. LXa). They each wear a kilt or long loincloth (zoma), boots, and sport short hair. Another group, consisting of four male figures of various ages, are depicted holding textiles and vessels (Doumas 1992, pls. 109–11).22 These are the only male human figures depicted in the entire structure, although male animals are shown in other spaces. The remaining figures shown on the walls of the structure are women.

Throughout Xeste 3, the depicted women are variously considered adorants, possible priestesses, initiates, and at least one female figure is considered a goddess. Except for the oversized seated goddess figure from Room 3a who accepts an offering from a blue monkey, however, the women do not appear to engage directly with animals. Vlachopoulos (2021) rightly draws attention to the function of the depicted animals as Potnia’s acolytes (cattle, agrimi, monkeys, ducks, birds, swallow/fledglings, dragonflies, flying fish, non-flying fish, and griffin). These animals do not so much represent the surrounding environment on the island of Thera as they do ‘reproduce cycles of (Knossian) Neopalatial iconography in which animals reveal religious symbolism, participate in rituals and promote exemplary qualities’, (Vlachopoulos 2021, p. 253). It is within this context that the roles of the depicted monkeys are separated for consideration.

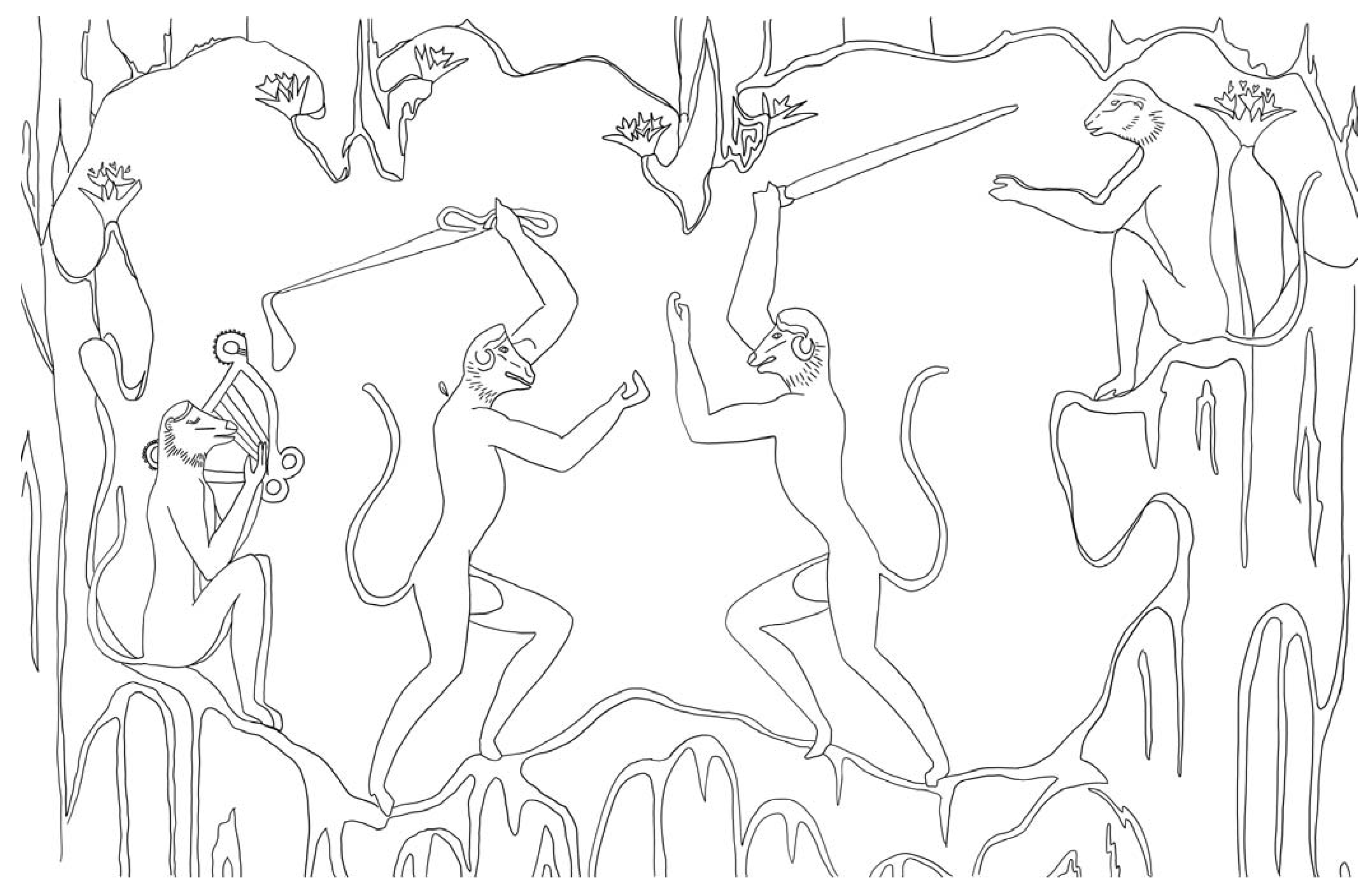

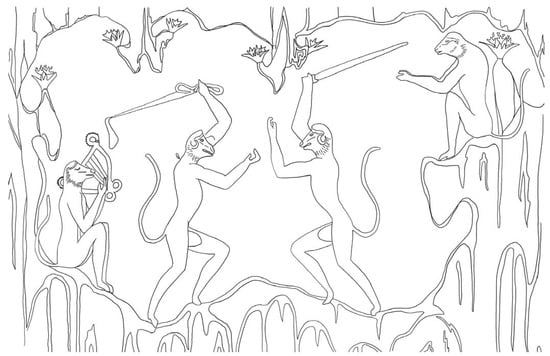

Monkeys are depicted in two spaces of the first story of Xeste 3: Room 2 and Room 3a. In Room 2, which was used for ritual performances and feasting (Vlachopoulos 2021, p. 261), at least four monkeys are depicted performing anthropomimetic actions with man-made objects amidst a rocky landscape that is dotted with clumps of crocus flowers (Figure 6). One monkey, seated to the lower left, faces to the right and holds a harp, mouth open—perhaps singing, chanting, or speaking. Vlachopoulos reconstructs this monkey in a seated pose, backside planted on the rocky groundline, and not in a crouching-squat position like most other monkeys in Aegean art (Vlachopoulos 2021, p. 264, pl. LXIIb; Pareja 2017, p. 16). The second monkey also faces right and holds a scabbard aloft, a yellow tassel or fur chape hanging from its end. This individual is reconstructed in an extended, upright, anthropomorphized posture, likely charging toward the right, and they appear to wear a large yellow hoop earring with red dots (beads?) around the exterior. According to the reconstruction, this same monkey wears something that ties, as the loop-and-line motif appears to extend from the back of the creature’s neck.23 A third monkey bears a gold or bronze sword overhead, presumably the weapon that is missing from the second monkey’s scabbard, but the head of the animal does not appear to be preserved, and so one may assume that it faces left, toward the animal holding the scabbard. If this is the case, then the scene is almost symmetrically composed (except for the vertical off-setting of the first and fourth monkeys), as this individual is also reconstructed standing in an elongated, upright pose. The fourth monkey faces left with its mouth open, and it may hold an instrument or perform percussive movement (playing a small hand drum, castanets/krotala, or clapping) while seated—not squatting—on rockwork in the upper right portion of the image.24 Dragonflies and swallows populate same landscape in the adjoining friezes. Notably, the rocky, crocus-laden background extends into Room 3, uniting these separate spaces.

Figure 6.

Line drawing of reconstructed Monkeys Wall Painting. Late Cycladic IA Period (1620–1500 BCE). Lime plaster and pigment. Line drawing by Marie N. Pareja after Vlachopoulos (2021, pl. LXIIb).

In Room 3a, the Offering to the Seated Goddess scene (Figure 4) features only one monkey in an upright—again anthropomimetic—posture, ascending a tripartite structure while offering crocus stamens to an oversized woman (goddess). Behind the monkey and to the left, a young woman empties crocus flowers into a basket, presumably from which the stamens have been separated before being deposited into a second basket, which rests on the intermediary step of the platform, in front of the monkey. The mythical griffin shares the uppermost level of the tripartite structure with the seated woman, head lifted and wings spread upward, despite the red cord that leashes it to the very real wooden window frame. In Room 3a, to either side of this central wall painting, images of a marshy reedbed and young women picking and carrying crocus flowers in a rocky landscape survive.

Although the remaining animals in Xeste 3 each play a variety of symbolic roles in the greater scheme of Potnia’s domain, the monkeys are particularly vexing, as their behaviors are categorically unlike those of the other animals depicted. Rather than behave as monkeys do when beyond the bounds of human interference (i.e., not caged animals, trained workers, or pets), they appear here to conduct themselves as humans do. This is certainly the case for the monkeys from Room 2, and arguably also the solemn monkey from Room 3a. The continuative nature of the scenes, united as they are by virtue of their background and location within the larger building, may also inform the ways in which one considers the subjects, themes, and traditions behind the monkey depictions in each space.25 As such, it is certainly worth mentioning that the Offering to the Seated Goddess image in Room 3a boasts a composition derived from the long-lived, traditional Mesopotamian Presentation Scene, which sometimes features a monkey between the approaching supplicant(s) and seated divinity or royalty (Pareja 2017, pp. 33–34, 121, 125). Perhaps the image from Room 2 also draws on traditions beyond the Aegean.

7. Contextualizing the Xeste 3 Monkeys

To better understand the monkeys in Xeste 3—especially those from Room 2, as little remains to be said about the solo, liminal creature in Room 3a—it may be beneficial to first separate and briefly contextualize various elements of the images. These include attributes (lyre, sword and scabbard, earrings, and items that tie (necklace, belt, and baldric))26 and actions (music, dance, and combat) considered via stylistic aspects (poses, gestures, and composition) with and in which the animals are shown. By seeking iconographic comparanda, nuanced aspects of the roles played by these creatures might be clarified.

7.1. Lyre

The lyre held by the first (leftmost) monkey does not possess any perfect parallels in Aegean iconography, but portable stringed instruments are depicted in various media. Younger identifies the instrument played by the animal as a triangular lyre, or else a toy that emulates one (Younger 1998, p. 10). Although the painted frame of the instrument is depicted as variegated, perhaps suggesting wood, the volute terminals appear lined with red dots, which may be made from bits of copper, reddened gold or ivory, or carnelian27 (Vlachopoulos 2021, p. 264, n. 114; Younger 1998, p. 15). No other imagery of triangular lyres survives from the Bronze Age,28 although other stringed instruments are represented in Aegean art. The painted lime plaster decoration on the Ayia Triadha Sarcophagus, for example, shows a figure playing a different type of stringed instrument (the phorminx) in a funerary context, an association compounded by the very purpose of the object on which the scene is depicted (Burke 2005, pp. 403–22; Younger 1998, p. 18). This is the same type of instrument held by the Lyre Player (inopportunely named), who is pictured beside a large bird in one of the lime plaster wall paintings from the Pylos Throne Room (Lang 1969; Younger 1998, pp. 18–19). Despite the long tradition and varied depictions of stringed instruments in the Aegean, it seems that only male figures29 are shown holding or playing these types of instruments.30

7.2. Sword and Scabbard

The weaponry pictured in these creatures’ hands is particular: the sword depicted may be made from gold or bronze, and the (presumably leather?) scabbard may have been colored with valuable purple pigment (Vlachopoulos 2021, p. 264).31 The sword pictured in Xeste 3 is similar in construction to the one pictured on the Pylos Combat Agate (Stocker and Davis 2017, pp. 594–95). The scabbard also somewhat resembles the scabbard of the victorious figure from the Combat Agate, although this relationship is slightly less convincing, considering the different decorations extending from the object’s end. The ornamentation is identified as a pendant finial made of fur, which is attached to the chape (tip) of the scabbard (Vlachopoulos 2021, p. 264, n. 115). Additional comparanda for this iconography are identified in wall paintings and glyptic art (CMS I 11; CMS XI 208; CMS I 290; CMS II 3 no. 16; Doumas 1992, p. 178, pl. 139; Pareja 2023b; Rehak 1999). Notably, both male and female figures are depicted with both sword and scabbard (as well as with only swords).

7.3. Earrings

The earring worn by the scabbard-wielding monkey resembles those worn by some of the other women in Xeste 3, namely those involved in the crocus ceremony and the adorants in the adyton from the sunken area on the ground floor (Televantou 1984, pp. 14–54; Vlachopoulos and Geroma 2012, p. 36; Younger 1992, pp. 260–61). The marked addition of red dots to the exterior curve of the hoop earrings—again, possibly made from copper, reddened gold or ivory, or carnelian—distinguishes these adornments from many others in Aegean iconography. Note the proportionally larger, thicker hoops worn by the male figure (African) from the Porter’s Lodge and the left Boxing Boy from Building Beta (Vlachopoulos and Geroma 2012, pp. 36–37, pls. XIId, XIIIa) when compared to the tapering, the perhaps more delicately rendered earrings seen on the women from the House of the Ladies (Doumas 1992, pls. 2–5), or the Young Priestess’ earrings that feature a four-pointed-star motif on the interior. Notably, both male and female figures are depicted with plain gold hoops of various sizes, but only the earrings worn by some women (and monkeys) appear with additional decoration.

7.4. Items That Tie

The presence of the loop-and-line motif on the neck or back of the second, scabbard-bearing monkey indicates the presence of another adornment: something that can be tied into a knot. In Aegean iconography, these items appear relatively infrequently, and the appearance of the motif is reliant on the perspective from which the wearer of the item is shown and the sartorial style of the wearer. When a torso (or at least the span of the shoulders) is rendered frontally, as seen with the Necklace Swinger (Doumas 1992, p. 141, pl. 104), the knotted closure of a necklace is not visible; if a torso is rendered in profile and yet long hair or a garment covers the back of the neck, as seen with the Veiled Girl from the adyton scene, then again, the knotted closure is not visible and therefore not depicted. This visual device is, however, easily visible as part of the red beaded necklace held by the Necklace Swinger. It also occurs on the back of the neck of a Fisherman from the West House (Doumas 1992, p. 55, pl. 23) who wears a red cord or ribbon as a necklace; or as a belt, as seen securing the flounced skirts of the Saffron Gatherers in Room 3a of Xeste 3 (Doumas 1992, pl. 122). Finally, the motif again indicates a device for securing, as a belt to which a scabbard is attached at the waist of a male from the Pylos Combat Agate (Stocker and Davis 2017, pp. 583–605). This motif too appears on both male and female figures, although admittedly more female figures are depicted wearing necklaces (Younger 1992, pp. 261–69).

In the present situation, the loop-and-line motif may indicate that a monkey wears a necklace or belt. Granted the thickness of the line as compared to the reconstructed bodily proportions of the animal, together with the yellow pigment used for its illustration, a (golden?) necklace may be more likely than either belt or baldric.32 Nevertheless, the reconstructed angle of the monkey’s body may largely block a longer, draping necklace from sight, unless it is jarred into motion by the animal’s movement toward its sword-bearing companion. Without additional fragments that might provide more information about the necklace, one may only speculate.

7.5. Music

It is not enough to simply describe the monkeys as emulative of musicians (if the first monkey does indeed hold a toy or model and not a real, functioning instrument)33 or even as musicians. Rather, the socio-political implications of the ways in which music is made, depicted, and controlled in Aegean culture lend particularly important perspectives to the viewing of this wall painting. Younger explains the foundational assumptions for the present discussion: ‘The primary purpose of Aegean formal art is to present and validate political relationships: power inequalities, status, and class; the formal requirements of [Aegean] society would demand that music’s exciting qualities be controlled; we would expect music, therefore, to be depicted as narrowly constructed and constrained; while at the same time, there must also have existed some sort of acceptable setting for expressing these excited feelings,’ (Younger 1998, p. 43). Essentially, music is treated as a form of release and control, and the imagery is managed to indicate the appropriate occasions for it. Most examples of musical performance date to the Mycenaean period, but of those occurring earlier, musical performance appears to consist of singing/chanting and the use of stringed (harp/lyre), percussive (sistrum/krotala/clapping), or woodwind (flutes) instruments (Younger 1998, p. 46).

The mouths of the musician-monkeys are open, suggesting singing, chanting, or speaking (Dumbrill 2015, p. 99).34 Unlike the singers from the Harvester Vase (Forsdyke 1954, pp. 1–9), whose heads are held at various angles and whose mouths shape the sound of their voices (as indicated by the modelling and lines in the cheeks), these animals’ mouths are not obviously animated. This may be due to an unfamiliarity of the artist with the appearance of singing (or screeching?) monkeys, but Aegean artists deliberately choose characteristic traits of the subjects they depict, so this is improbable.35 Nevertheless, the difference in media may better inform this relationship: the planes of the face and its various expressions are not shaded or modelled to show volume in two-dimensional artworks. Granted the difference in media, together with the monkeys’ elongated, fur-covered snout—differing considerably from our fur-less, snout-less human mouths—it seems that the artists chose to emphasize the playing of instrument(s) and the physical form of the instrument(s), leaving one’s mind to fill-in-the-blank, so to speak, of the open mouth.

More complicated, however, is the question of the contexts in which music is played. Musicians are depicted as present and/or actively playing in mostly ritual settings, particularly those associated with death—funerary, sacrificial, and military—perhaps illustrating, in part, the broad applicability of lamentations.36 Notably, the musicians appear to be male (or at the very least, dark-skinned figures wearing robes). The pairing of music with the rigorous movement in Room 2 of Xeste 3 appears relatively unique in the Aegean. Only the Harvester Vase and a sealing from Knossos (HMs 260 + 263) show music paired with marching. One wonders, however, about the Bronze Age distinctions between walking together to perform a task, marching with militant purpose, processing (in a run or walk), and dancing.

7.6. Dance

Only one scene in the Aegean corpus is identified as a dance: the Sacred Grove and Dance wall painting from Knossos (Immerwahr 1990, no. Kn15). This scene, however, may just as well be called the Sacred Grove Procession or the Sacred Grove Ritual, as no fragments survive that indicate the presence of music. The same can be said of the imagery on the Isopata Ring (CMS II.3 no. 51). If these are considered scenes of dancing, then there are probably many more images that have not yet been recognized as such (Younger 1998, p. 53). Perhaps some seals and sealings thought to depict supernatural compound creatures in contorted poses, such as those crafted by the Zakros Master, show dancing humans in full or partial (natural or supernatural) animal costumes. Other types of imagery that might also show dance include but are not limited to processions, acrobatics, and even scenes involving the iconography of dueling or combat, which might be considered war-dances (CMS V 643; CMS XI 34; VS1A 294; CMS VIII 008a), thus expanding the corpus of participants to include women and men. This seems to be the case for the monkeys from Room 2 of Xeste 3 as well: they participate in music and dance, actions frequently paired in rituals performed throughout the Bronze Age world. ‘The central protagonists of the performance stand upright, like their crocus-offering “brother”, and grip our attention in their ritual dance, which does not enact a duel or a mimetic prank but is the triumphal display of the sword and its accoutrements,’ (Vlachopoulos 2021, p. 265).

7.7. Combat

Although as currently reconstructed, these monkeys certainly appear to be dancing while holding martial attributes (the sword and scabbard), one must note parallels in composition and posture. The central monkeys’ poses are, at first glance, seemingly analogous to that of the victorious figure in the Pylos Combat Agate: sword held overhead, moving to strike his ill-fated opponent, who maneuvers his shield perhaps a moment too late. This scene is one in a longstanding tradition in Aegean glyptic arts.37 In seals and sealings, however, a third figure who lays on the ground is often represented, presumably already slain. According to the most recent reconstruction, Room 2 lacks this third, slain individual—no conquered monkey lays sprawled on the ground.38

The positioning of the sword and scabbard as the monkeys approach one another also does not fit with the composition of the traditional combat scene. They lift the objects over their heads, but rather than angling the end/tip of the items downward toward the other’s shoulders, the objects point back and away from the other animal. Although this could be interpreted as a swinging or chopping motion rather than a downward piercing or jabbing motion, the creatures’ poses are markedly distinct from those of warriors in combat scenes and yet seem perhaps more analogous to the four seals with (approximately) symmetrical figural arrangements that might show dancing. This comparison is not perfect either, however, as these four scenes show swords angled or crossing at hip- or torso-height, and the dancers (or combatants or both?) are shown in much closer proximity to one another—entangled in a pose perhaps anticipated by the monkeys from Room 2, if they continue on their current trajectory toward one another. When considered together with the pair of monkey-musicians and the absence of helmets, shields, other armor, or a fallen comrade, the central pair of monkeys from Room 2 of Xeste 3 are almost certainly shown dancing—an activity that can still be considered martial in tone, but it is still not combat.39

7.8. Biological Sex and the Gendering of Space, Objects, and Iconography

The objects in the scene and the generalized roles associated with those objects prove problematic when considered within the larger context of Xeste 3, particularly the image’s location on the first story, together with the rocky, crocus-dotted setting that is shared with the Potnia. In Aegean iconography, the three possible activities depicted here (playing music; combat; and performing a war-dance) are performed by males. The possible presence of a belt or necklace is not reserved for a single biological sex. The only visual element that appears solely in association with women is the red-bead-studded gold earring. The only males in Xeste 3 are depicted on the ground floor, and none are richly adorned as the women from the adyton or first floor, who sport matching earrings with the monkeys. Is it problematic, then, that masculine-presenting animals perform in the otherwise woman-dominated program of the first floor?

To sidestep this issue, the sword (presumably together with its scabbard) might serve as one of Potnia’s attributes (Vlachopoulos 2021, p. 266). By reassigning the attribution of the object to the deity rather than the animals, one of the hurdles is evaded. The scene can then be reinterpreted as a presentation of the object—or perhaps preparation to present it?—to the seated goddess. Perhaps the same can be argued for the pair of musicians, thereby eliminating the interruption of the feminine program of the first floor. This solution falls a bit short, as it fails to acknowledge that the crocus stamens are offered to the seated goddess directly, not the weaponry, and, although the presence of the deity is communicated via the shared background, Potnia is not overtly depicted in this room, as she is in 3a. Room 2 is described as ‘an autonomous unit of rituals, and its iconography as a likewise autonomous cycle […] the said space is a shrine-in-shrine’ (Vlachopoulos 2021, p. 266). As such, these objects are only directly and overtly visually associated with the monkeys, and more work is required to associate them with Potnia.

This resurrects the question of gendered objects and space, a frequent topic for those discussing Bronze Age monkey and ape imagery. The animals depicted in Aegean art possess no clear indications of biological sex. Unlike cattle, for instance, where the sex of the animal is often critical for image interpretation, and unlike their counterparts in Egyptian art, the blue monkeys of the Aegean remain sexless. By trying to assign or affiliate gender with these animals, as with artifacts, art historians and archaeologists are missing the point: Bronze Age artists made the deliberate choice not to illustrate whether they are male or female, and so, to put it quite bluntly, it does not matter for the reading of Aegean art.40 This deliberate ambiguity may, however, serve as an additional clue to the cultic roles embodied by these creatures. One of the oldest deities from Mesopotamia bears striking parallels to the paradoxical and adaptable Aegean Potnia, as well as her cult activities and personnel—in particular, her lamentation-singing, sword-dancing, animal-costume-wearing, gender-bending attendants and cult participants.

8. Inanna, Participants, and Performance

The earliest preserved written texts from Sumer bear the name of Inanna (Akkadian Ištar)41, the longest-lived and perhaps single most important deity in Mesopotamia (Black and Green 1992, pp. 108–9).42 Her myths, character, and details of her worship survive in primary sources, affording a rare diachronic glimpse of both goddess and practices.43 As a goddess of paradoxical duality, she is a mercurial, liminal figure who consistently defies binaries and boundaries alike, not least of which is the delicate balance of life and death, which she navigates as a resurrected god.44 She embodies creation and destruction, young and old, structure and chaos, sex and war, femininity and masculinity, maidenhood and prostitution, maiden and widow. Critically, she is not a goddess of motherhood45 or marriage, but beauty, eroticism, and extramarital sex (Streck and Wassermann 2018, pp. 15–21). Inanna ‘shatters the boundaries that differentiate the species, those between the divine and human, divine and animal, human and animal’, (Harris 1991, p. 272). Her attributes include stars, the stellar/solar disk, lion(/ess) (as martial aspect), doves (as pacific aspect), weaponry,46 and libations. She is frequently depicted in this martial aspect, ‘as a w41arrior goddess, often winged, armed to the hilt’, and in the presence of her lions (Black and Green 1992, p. 109). Notably, she is depicted in feminine and masculine forms (Sacher Fox 2009, p. 53).

In an early Sumerian myth, Inanna flies into a brutal, destructive rage that terrifies the other gods (Foster 1977, pp. 79–84; Kramer 1981, pp. 1–9; Scurlock 1988; Wolkstein and Kramer 1983). This violently explosive behavior is often related to traits traditionally considered masculine: her love of battle, which is frequently referred to as her playground, and her desire for conquest (Black and Green 1992, p. 109). One of the other deities, to stop the chaos and bloodshed, creates a new class of priest for the express purpose of soothing and lulling her into a more pacific state. The most important of their performances are known as Balag and Ershema, named for the instruments required for their performance, the lyre and a percussion instrument (Mirelman 2022, p. 211). Th new group of priests, the gala, employ an arsenal of hymns, prayers, laments, and music (singing, percussion, woodwinds, and strings) to distract and entertain the bloodthirsty deity. These male attendants are not personifications of calmness or characters of mere myth, but real individuals responsible for performing these duties in her various temples, particularly during feasts, festivals, and other ritual occasions. The gala are depicted in pairs and described as appearing and behaving as women, which unites them with Inanna’s entourage of gender-nonconforming cultic personnel.

Binary breaking and genderbending contribute to a larger retinue of cultic roles and behaviors for Inanna’s followers47, who are responsible for blurring the line between structure and antistructure in rituals and performances that defy cultural norms and break typical societal restrictions (Peled 2014, pp. 289–91).48 This is often achieved by nimbly engaging the notion of play (mēlulu). Celebrants participate in a variety of games, ranging from those simple and safe for children to dangerous (or complicated) and reserved for trained adults: hide and seek, jump rope, games of chance (e.g., dice), physically competitive games (e.g., racing), perception-altering activities (e.g., merry-go-rounds and swings), and various types of performance, including dance (often with swords), music, and theatrical performances by masked, costumed actors (Caillois 1961, p. 36).49

Other attendants to Inanna include the assinnu and the kurgarrû (Peled 2014, pp. 283–84, n. 5). Although general scholarship assumes that both classes of priest are males with feminine attributes, Peled argues that the kurgarrû are cult warriors who perform sword dances, among other activities. Kurgarrû are still understood as militant, masculine, and virile, particularly during the mock battles (reenactments?) in which they participated, together with the assinu.50 The dance, however, is just one of various events in which these priests were paired. ‘These two figures formed a mirror-image of each other, the reason being their mutual performance in the cult of Ištar[/Inanna]… The effeminate assinnu and masculine kurgarrû, who frequently cooperated in cultic rites, represented the whole of their patron goddess and the complete spectrum of her gender image,’ (Peled 2014, p. 284). Essentially, via social action, these individuals seem to perform or (even temporarily) embody complimentary roles.

It has also been suggested, however, that some members of the kurgarrû are female. These women are noted among groups of (exclusively women) singers of various nationalities and ethnicities (Fales and Postgate 1992, pp. 32, 34; Henshaw 1994, p. 289). Amidst discussions of Inanna’s attendants are frequent mentions of singing and dancing as being women’s ritual activities (Peled 2014, p. 284). Granted the consistent and high degree of gender fluidity and transformation, sword-dancing women were perhaps also part of Inanna’s cult personnel.51 One might note, however, that the modern conceptions of an individual’s transformation from female to male or vice versa (and the various qualitative measures that are often applied to such conversations, interrogating the nature of the change: psychological, physical, social, and so on) might not have been considered in Mesopotamia. It may simply have been enough to understand that Inanna is the one ‘turning a male into a female and a female into a male,’ as explained in the Lady of the Largest Heart hymn (Sjöberg 1976, p. 183).52

Non-physical transformations also fall under Inanna’s purview. The maḫḫû/muḫḫû and muḫḫūtu, for instance—practitioners that are both women and men—participated in cult worship and performance by entering into trance states (Steinert 2022, p. 371). The name for this role derives from maḫû, the term for becoming frenzied, entranced, moving in a vigorous, agitated way, or raving (Steinert 2022, pp. 371–72, n. 13). Similarly, the zabbatu and zabu (women and men, respectively) are also named for their frenzied behavior (Stökl 2012, p. 57). Such shifts from mundane, everyday awareness to altered states of consciousness are attested in many and various prehistoric cultures (Stein et al. 2022). Such states can be encouraged or induced in a vast number of ways, including but not limited to sensory deprivation, sensory overload, extended fasting and/or exhaustion, the observation of or engagement in repetitive movement or sound, the use of psychoactive substances, self-mutilation or bloodletting, and perhaps even the simple act of viewing.53 It is worth noting that music accompanies and sometimes drives many of these experiences (Dumbrill 2018; Winter 2022, pp. 219–21), particularly as both music and ecstatic experience are intertwined with emotion (Delnero 2020, pp. 8–37, 51–65, 115–33; McMahon 2019). Many texts record hymns, prayers, and ritual proceedings, which clarify the relationships between these and other performative elements.

Iddin-Dagan’s Sacred Marriage Hymn to Inanna describes some of the participants and events in a festival. ‘Male prostitutes[54] comb their hair before her… they decorate the napes of their necks with colored bands… they gird themselves with the sword belt, the “arm of battle” … Their right side they adorn with women’s clothing … Their left side they cover with men’s clothing… the ascending kurgarrû priests grasped the sword… The one who covers the sword with blood, he sprinkles blood … he pours out blood on the dais of the throne room,’ (Reisman 1973, p. 187).55 This passage bears four particularly important details. First, the presence of masculine males who (first) wear colored bands on their necks—might these bands tie at the back of the neck? Second, these men are associated with sword belts, drawing martial or sacrificial associations. Lastly, the deliberate use of the terms ‘sprinkling’ (third) and alternately ‘pouring’ (fourth) in reference to the blood, likely the result of bloodletting and/or sacrifice.56 This almost certainly indicates blessing or anointing via sprinkling and offering libations via pouring, ritual actions for which ample evidence survives in the Aegean.

9. Reexamining Xeste 3

The parallels between the attributes, descriptions, and activities of Potnia’s genderless monkeys and Inanna’s genderbending personnel are striking. The monkeys scene in Room 2 shows two simian pairs engaging in the very activities so clearly recounted in Sumerian and Akkadian texts by Inanna’s special classes of priests. The pair of monkey musicians on the exterior of the composition appear to be synonymous with the musically inclined gala, who are also typically depicted in pairs. They play the same types of instruments and sing,57 and they perform together with the central pair of dancers. The scabbard-bearing monkey may embody one of the assinnu, with its feminine, red-beaded golden hoop earring and possible necklace.58 The sword-bearing monkey on the right is currently reconstructed with the same earring, but the most recently published photographs of the original fragments do not show more than this animal’s hand and arm, and so the creature may not wear a red bead-studded golden hoop. The scabbard may represent a stand-in for a second sword, and/or be used as a visual foil to emphasize the martial, more aggressive role of the sword-bearing monkey. If this is correct, then this wall painting shows subtle distinctions between the creatures that are also used to delineate the roles of Inanna’s animal-costume-wearing, performing gala, assinnu, and kurkarrû.

Although the precise ritual depicted in Room 2 remains a mystery, there are a few notable traits that might contribute to an eventual decoding of the general type of event represented. The zoomorphic figures, lyre, singing, vigorous movement of the sword dance, and possible reference to the underworld59 parallel the subjects on the bull-headed lyre from the Royal Tombs at Ur, an object that predates the wall painting by as much as a thousand years. The animals engage in wrestling (vigorous activity, as would be expected in funerary games), harp playing and singing, and the scorpion-man stands as a psychopompic reference to the underworld.60 Sacrifice and banqueting are themes depicted on the lyre that do not appear in Room 2 of Xeste 3, and yet sacrifice may appear in Room 3a if one considers the harvesting and offering of saffron to Potnia as such.61 It seems possible, therefore, that the scene from Room 2 could show the performance of a lamentation ritual or something similar.

Within the greater context of Xeste 3, the placement of the scene is notable. The space in which it was painted is nearby but separate from the depicted apex of cult activity (offering saffron), perhaps suggesting that the theatrical performances are preparatory, taking place before the events pictured in Room 3a. One might consider the spatial separation of practitioners and Inanna in different parts of a much longer, possibly twenty-four-hour ritual (as indicated in Lady of the Largest Heart) and the decoration in spaces throughout Xeste 3 as perhaps representative of some of the various phases of the recounted ritual.62 This could suggest that the music and dance take place concurrently with or even after the scene in Room 3a. Matters of temporality remain unclear. The monkeys—as physical embodiments of far-flung networks of exchange (and perhaps influence), and as creatures with a particularly close relationship with the goddess—perform in a space that is purposefully separate from the seated deity, as indicated by the crocus-studded rockwork that encloses them within the visual space63 and the very physical structures of the building itself.64 As such, they can be regarded as connected to but wholly separate from the crocus ceremony taking place in the scenes from the nearby space.

The question remains, however, as to whether this scene ought to be interpreted as mythical, allegorical, or illustrative of real actions and events. Although the author argued elsewhere (Pareja 2015, 2017) that this wall painting can only represent a purely mythical scene, this no longer seems to be the case.65 Although it does not show cult proceedings in a literal sense (monkeys were not playing harps or brandishing swords), it does illustrate what ritual participants were perhaps expected to see and/or understand: special performers appear as animals that blur the boundaries between nature, human, and divine (perhaps affecting all three realms and their inhabitants),66 emulating their patron deity by virtue of their liminal and transformative nature in this particular context. The element of transformation is not solely limited to gender roles—or the absence of them—but includes the perceived natural order.

Monkeys are also irrevocably intertwined with notions of travel, exchange, and far-flung, little-known places for both Mesopotamian and Aegean peoples.67 Especially when considered in terms of eco-social spheres of human interaction,68 it seems particularly fitting for the monkey69 to embody the interface between the human and the divine. Nevertheless, one cannot help but wonder at the immediacy of communication and understanding between the Aegean and Mesopotamia. The regions did not share a common language and may not have maintained constant, consistent communication, particularly granted the ever-changing boundaries of the various kingdoms and states in the Bronze Age. How could such nuanced and clear information about the specific roles and practices of one (albeit widespread and exceptionally adaptable) cult have been learned, observed, or otherwise communicated so that they ultimately appear in the wall paintings of Xeste 3?

The Near Eastern and Mesopotamian palaces’ ‘Minoan-style’ wall paintings and archives may help to answer this question. Qatna, Tel Kabri, Tel el-Burak, and Mari each possess decorative architectural evidence for a real, personal interfaces with the Aegean.70 When coupled with textual documentation, such as the archives at Mari, additional evidence of interactions between these regions emerges. Although no references from the Mari archives have yet been found that address the ethnicities or nationalities of those who created the lime plaster wall paintings, they do indicate communication between Zimri-Lim and a man from Crete at Ugarit—via translator, and perhaps together with accompanying officials (Foster 2018, pp. 344–46, 353–54). A hematite cylinder seal from Mari (British Museum Object Number 89255) shows a seated ruler, holding the rod-and-ring of rulership, in a possibly Aegean-inspired ship, for which there are no parallels in other Mesopotamian cylinder seals (Foster 2018, p. 354). If nothing else, it is certainly worth noting that Zimri-Lim participated in festivals and rituals of Inanna, the patron deity shown transferring kingship to him with the rod-and-ring in those same palatial wall paintings that may have been created by Aegean hands (Ziegler 2007, pp. 55–64). By no means does this unilaterally prove continuity between Potnia and Inanna, or between Mesopotamian priests and Cycladic wall paintings. It does, however, allow for a better sense of what communication, collaboration, and exchange looked like between these groups.

10. Conclusions

The ideas proposed here are not new—they are sprinkled throughout the last 60 years of scholarship on the finds from Akrotiri. This article is simply the first study to juxtapose the simians depicted in Xeste 3 with priests from the cult of Inanna/Ištar. This chapter does not argue that the monkeys depicted in Room 2 are the gala, assinnu, and/or kurgarrû, but rather recognizes and acknowledges the similarities between their documented and depicted activities, attributes, and cultic roles. Karen Polinger Foster aptly describes the ways in which perception, memory, and performance intertwine, which perfectly fits the way this paper approaches the Room 2 wall paintings from the first floor of Xeste 3: “Thanks to them, we enter a distant, kaleidoscopic world of metaphor, wherein distinctions between human and animal, sacred and secular, shift, blur, and clear, only to shift again”, (Foster 2016, p. 75).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new datasets were created for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | I am so very grateful to Branko van Oppen and Chiara Cavallo for the invitation to contribute to this special issue of Arts and for all their guidance and tireless work. I am always grateful for my partner in crime, Anne P. Chapin, for our endless conversations, her support, and her ever-constructive criticism. Thank you to Doug Morrow for entertaining various late-night epiphanies and for supporting my work in so many ways. I am grateful to so many colleagues for candid discussions, recommendations, suggested sources, study photographs, guidance, and multifaceted support, especially those who urged me to finally publish this particular investigation. Thank you to the reviewers for your close critical eye, genuine interest, and suggestions. Finally, I hope this serves as an enjoyable exercise for you, dear reader. As always, any and all errors in the following publication are my own. |

| 2 | For a discussion and review of such evidence from the Neolithic through Bronze Age periods, see (Pareja 2023a), especially 1–7. For extended consideration through the time of Alexander the Great, see (Arnott 2020). For the most recent work in this field as a result of an international workshop hosted by the University of Oxford in December 2022, see (Pareja and Arnott 2024). The modern understanding of relationships between the Aegean, Mesopotamia, and Egypt, in all permutations and combinations, continues increasing in complexity and nuance, particularly with the veritable renaissance catalyzed by scientific materials analysis (Pareja 2021). Although countless parallels exist between Egypt and the Aegean, the purpose of the present paper is to focus on possible relationships between the Aegean and Mesopotamia to facilitate possibilities for alternate perspectives and interpretations regarding a single wall painting from Akrotiri, Thera. |

| 3 | Such relationships between the Aegean and Egypt have been intensively explored since the 1990s, perhaps most notably by Eric Cline (1994, 2013); Alexandra Karetsou (2000); Jacqueline Phillips (1991, 2008). For travel and exchange between Egypt, the Near East, and Mesopotamia from at least the Chalcolithic period onward, see (Foster 2020; Oshiro 2000; Watrin 2004). With specific regard to monkey and ape iconography and the similarities between the artwork of Egypt and the Aegean, see (Greenlaw 2005; Pareja 2017, pp. 11, 19–27, 121–23). For ancient depictions of primates in the Mediterranean, see (Greenlaw 2006, 2011). For the first proposed identifications of various genus or species of Egyptian monkeys depicted in Aegean art: vervets, see (Parker 1997, p. 348); various baboons, see (Greenlaw 2011); grivets, see (Fischer 2019); guenons, see (Foster 2012). |

| 4 | Although Tel el-Burak currently holds the earliest known polychrome wall paintings executed in an Aegean style by approximately 200 years, it remains unclear whether this is a (local?) development, independent of Aegean influence (whether direct or indirect), or whether this truly is the earliest Aegean painted lime plaster decoration in the Near East (Bertsch 2019, p. 393). |

| 5 | For a more extensive study on the Aegean elements present at Mari, see (Foster 2018). |

| 6 | These may be ringed poles, symbols associated with Inanna (Cabrera 2018, p. 49, n. 4), or they might represent stylized, artificial trees. |

| 7 | For the spatial meaning of the scene with respect to the layout of the palace in which it was found, see (al-Khalesi 1978, esp. 37–69) and (Margueron 2014, pp. 152–55, fig. 175). |

| 8 | The rod and ring are traditional Mesopotamian symbols for rule and kingship (Abram 2011; Slanski 2007, p. 41; 2004, p. 262; Van Buren 1949, p. 449). |

| 9 | Is it possible that this relational gesture is mimicked by not only the monkeys in Aegean art, but many of the human figures as well? Such poses—and possible variations of them—are visible in glyptic arts, figurines (particularly from peak sanctuaries), and other media. For more on gestures of prayer and reverence, see (Morris and Peatfield 2002; Morris and Goodison 2022). For more on relational gestures, see (Myres 1902–1903; Rutkowski 1986, pp. 87–88; 1991, pp. 52–56; Morris 2001, pp. 248–49). |

| 10 | Because the archives from Mari refer to her as Ištar, this theonym and other Akkadian terminology is employed to describe the Investiture Scene (i.e., lamassu (Akkadian) instead of lama deity (Sumerian), although other iconographic nuances have been suggested for the distinction between these two terms, as well). The author acknowledges that some scholars may take umbrage with such flexibility between theonyms and elision of the goddess’ nuanced changes in identity over thousands of years throughout antiquity. Nevertheless, beyond the description of the Investiture Scene, the deity will be referred to as Inanna. |

| 11 | Although the tops of each representation of the tree with red bark and blue leaves are not preserved, it is possible that they represent the Huluppu tree or trees from Inanna’s sacred garden. |

| 12 | Not least of which include passages about Zimri-Lim’s participation in a festival of Ištar (Inanna) at Mari (Ziegler 2007, pp. 55–64) and texts from the Mari archives that attest to Zimri-Lim meeting and trading with individuals from Crete while visiting Ugarit (Foster 2018). |

| 13 | All CMS numbers are object identification numbers assigned by the Corpus of Minoan and Mycenaean Seals, the database for which can be found at the following website: https://arachne.dainst.org accessed on 23 November 2023, (Förtsch et al. 2011). |

| 14 | This debate is simplified here for the sake of brevity. For a more thorough discussion of this problem, see (Blakolmer 2010; Crowley 2008). |

| 15 | Foster recognized a likely reference to a Minoan king/prince (or other male in a position of leadership or power) and Minoan translator in the Mari Archives, from the time during which he travelled to the port at Ugarit (Foster 2018, pp. 346, 354). |

| 16 | See, for instance, (Marinatos 2008, 2010). This comparatively infrequent depiction of male figures is also cited as reason to suspect a possible matriarchal society. Images of men in superior positions are limited compared to those of women, some of the most notable including the erroneously reconstructed Priest King wall painting from Knossos and the Master Impression from Chania. |

| 17 | The arguments regarding who or what Potnia is constitute a veritable can of worms. Is she a concept? Another word for woman? A goddess? A lexical designator for a powerful woman? A priestess? A more abstract social role? For a summary of the evidence and discussion, see (Kopaka 2001). |

| 18 | For more on monkeys in Mesopotamia, see (Dunham 1985; Pareja 2017, pp. 31–49). |

| 19 | For more on animal roles and hierarchy, see (Blakolmer 2016). For eco-social roles with humans, see (Chapin and Pareja 2020). |

| 20 | Of course the same is also possible in Egypt, where animal satire is also well attested (Manniche 1991, p. 112). |

| 21 | With the exception of death masks, such as those from the shaft graves at Mycenae, which serve a quite different purpose (Mylonas 1973), and perhaps two figures from glyptic art: the male figure in the Master Impression (as noted by Foster 2016, p. 74) and the helmeted figure from the Pylos Combat Agate (Stocker and Davis 2017, p. 593). I must note a monkey-headed (or Humbaba-headed) rhyton from Tiryns (Kostoula and Maran 2012, figs. 2–10), which, in casual conversation at the 2020 AIAs in Washington D.C., colleagues proposed might have been held in front of the face like a mask before being used for libations. |

| 22 | Although fragmentary, the three younger nude male figures are better preserved than the oldest male figure, as they are missing only small portions of their legs below the knee, but the older, clothed male is not preserved below the thighs. |

| 23 | On closer inspection of the blue tone of the monkey’s body against which the loop-and-line motif is depicted, it does not appear to be identical to the blue of the rest of the monkey on whom it is reconstructed. This may be a result of the photographic process, or fault with the author’s eyes, but if this is indeed the case, then two possibilities remain: either the color of the fragment was altered (via erosion and time, publication, or something else entirely), or an Aegean device for distinguishing between two overlapping or nearby elements of identical color is at work, here. If this is the case, then there may be a fifth monkey in the image. Nevertheless, this would certainly disrupt the approximate symmetry of the image. Take this proposal with a grain of salt, however, as the author is not involved in the conservation and reconstruction efforts at Akrotiri and has not (yet!) had the opportunity to view these fragments in person, under the same light, beside one another. |

| 24 | Again not reconstructed as resting in the typical crouching-squat position. |

| 25 | This is one of the few divergences from Vlachopoulos’ reading of the relationship between these spaces, as he asserts that Room 2 is treated rather as a shrine-within-a-shrine, or a separate space with a specific purpose. Rather, I would like to propose that these two spaces may be more directly, thematically linked than was previously anticipated. |

| 26 | As crocuses have been covered exhaustively elsewhere and their associations are currently limited exclusively to women and monkeys (and griffin?), this information will not be reviewed again here. For more on crocuses and saffron in these contexts, see (Day 2011a, 2011b, 2013; Marinatos 1993, 1987). |

| 27 | If these dots are indeed meant to represent carnelian, then this monkey’s item stands as yet another testament to Eastern exchange, as the likely origins of the lyre lie in the Indus River Valley (Vyas 2020), as do the deposits of carnelian and the resulting workshops that were situated along the coast of the region now known as Gujarat (Kenoyer 2017, p. 151; Mackay 1943). This is particularly important, as both of these—stringed instruments and carnelian—are known to have passed through Mesopotamia, where alterations were often made, before reaching the Aegean via indirect exchange (for more on such exchange, see Aruz 2003). |

| 28 | Although alabaster fragments of one may survive (Younger 1998, p. 16). |

| 29 | Or at least dark-skinned figures who wear long robe-like garments and various lengths and styles of hair. |

| 30 | Because the krotala are not visible (if the fourth, rightmost monkey plays them rather than claps), they are not included in the main text of this discussion. If these instruments were indeed depicted, then this scene would constitute the first scene in Aegean art that showcases two or more instruments being played at the same time, something hitherto seen in the art of the cultures with whom the Aegean communicated, traded, and exchanged (Younger 1998, p. 46). Critically, a set of krotala were recovered from Xeste 4, the monumental building of which Room 2 held a ‘privileged view’ (Vlachopoulos 2021, p. 261), at Akrotiri (Mikrakis 2007, pp. 89–92, figs. 1–4). Given the above discussion of the bull-headed lyre from the Royal Tombs at Ur and the relationship between the actual object and the depiction of it in a ritual scene, actively used by an animal musician/participant, the discovery of such instruments nearby becomes significantly more important for this discussion—doubly so when one considers that while a pair of the recovered krotala are shaped like hands, a third is decorated with birds and a rocky landscape studded with crocuses. Could there have been, perhaps before the pre-eruption evacuation, a triangular lyre somewhere nearby, too? |

| 31 | Indigotin, the molecule for the purple pigment that is famously derived from mollusks (murex), also occurs in several plant species and is a highly fugitive material, particularly with relation to light and time (Brysbaert 2007). |

| 32 | Note, however, the possible parallels this addition could strike with the Saffron Gatherer wall painting from Knossos, in which original, preserved fragments indicate the presence of red lines at the monkeys’ waist, wrists, ankles, and arms. Although some have proposed that these lines are indicative of halters (or otherwise devices for controlling/showing ownership of the animals), it is possible that they represent bands of adornment, similar to the red cord or ribbon seen tied at the necks of some male figures. The human figures’ bands include the loop-and-line motif, however, whereas it is conspicuously absent from the monkeys in the Saffron Gatherer scene. Perhaps the details are too small to consider worthy of depiction, or perhaps these red bands are affixed to the body in another way (more akin to bangles and arm-rings, which are more frequently worn by men than women), are made from another material, or even represent something altogether different (Younger 1992, pp. 269–72). |

| 33 | When first discussing this possibility as a graduate student in 2014, this idea was met with, ‘who in their right mind would give a real harp to a monkey?! It would be destroyed in seconds!’ It seems that any one of the Bronze Age cultures would give a harp—and sword, no less!—to a monkey, whether an actual animal or a cult participant costumed as one. |

| 34 | The mouth of the monkey who offers saffron to the seated goddess is closed, and so the creature does not appear to orally communicate. |

| 35 | For more on this, see (Chapin 2004; Pareja 2017, pp. 12–17; Pareja et al. 2020a, p. 772). |

| 36 | The documentation of which survives from ancient Egypt (Verbosek 2011), Mesopotamia (Delnero 2020), the Near East (Jacobs 2016), and likely the Aegean as well (Younger 1998, p. 52). |

| 37 | Varying in period and style, each of the following seals shows the same motif of victor, shielding adversary, and slain individual (Kellenbarger 2023): CMS I 011; CMS II.6 017; CMS I 012; CMS I 263; CMS XII 292; CMS VII 129; CMS IX 158; and possibly CMS XII D013. Kellenbarger proposes that this composition may be an Aegean invention that involves the adoption and adaption of the ancient Egyptian Smiting Pose. |

| 38 | Unless the lighter colored blue fragment with the loop-and-line motif does not belong to the scabbard-bearing monkey but an as-of-yet undepicted fifth ‘slain’ monkey. The likelihood of this is slim, however, especially considering the poses of the central creatures when compared to combat versus potential war-dancing imagery. |

| 39 | No seals are currently known to depict monkeys holding swords or scabbards from the Bronze Age Aegean. |

| 40 | Although ancient Egypt associates certain types of monkeys in certain situations with either women or men, as do other Near Eastern and Mesopotamian groups, the Aegean currently does not appear to do the same. This may change in the future with the discovery of new evidence. |

| 41 | Contemporary scholarship refers to her as either or both theonyms (Heffron 2016). |

| 42 | For a comprehensive comparison of the traits shared by the Aegean Potnia and Mesopotamian Inanna/Ištar, similarities between their cultic structures, see (Pareja 2023b). |

| 43 | As mentioned elsewhere, the author (lamentably) does not read cuneiform and therefore relies on translations. Any fault in the understanding or interpretation of the information from these translations is the sole responsibility of the author. Some of the various translations used here include From Enheduanna to Inanna (Hallo and van Dijk 1968, p. 19); The Great Prayer to Ishtar in two versions (Reiner and Güterbock 1967, p. 259); The Incantation Hymn (Cohen 1975, p. 16); and some hymns and prayers without titles (Reisman 1969, p. 167; Sjöberg and Bergmann 1969; Sjöberg 1976, pp. 189–95; Güterbock 1983, pp. 157–58). |

| 44 | For a thorough discussion of Inanna’s dual nature as it is recorded in Mesopotamian texts, see (Harris 1991 and especially Streck and Wassermann 2018, forthcoming). |

| 45 | Although she is a protector of pregnant women, children, and young mothers. |

| 46 | Most commonly the sword and, in earlier periods, the double axe. |

| 47 | One must note, however, that Budin argues staunchly against the notion of genderbending, including third and fourth genders in the ancient Near East, particularly in the case of Inanna’s cult (Budin 2023, pp. 175–215). She argues from a series of key points: 1. Modern and ancient understandings of gender, and therefore genderbending, are incompatible (pp. 175, 177); 2. The problem of survival coupled with the concept that the texts which are preserved may include errors or damage, and so they are not always perfectly legible and clear (pp. 178–80); 3. The Stand Alone Complex and Corrupting Consensus, which essentially refer to the inadvertent human error of a single false conclusion that is then repeated and reinforced in scholarship until the error has become nearly canonical and takes considerable effort to disprove and dislodge (pp. 180–81). She also states, however, that ‘what we do have is evidence that people flouted gender roles and conventions for public reasons, such as political roles and economic prerogatives. So gender bending took place for social reasons,’ which may be a statement better suited to the argument at hand (p. 177). If the reader prefers Budin’s argument against the notion of genderbending as present in the ancient Near East for this aspect of the investigation, then the question of the seemingly genderless monkeys remains unanswered and without parallel from neighboring regions. Nevertheless, the other elements of this paper’s argument continue to support the ultimate observation: parallels exist between the monkeys depicted in Room 2 of Xeste 3 at Akrotiri, Thera, and the attributes (musical instruments, weaponry, adornment, and pairs of performers) and actions (martial dancing, and musical performance), as well as broader contexts (in association with ritual scenes, in a cultic structure as opposed to a domestic or commercial building) of particular, named priestly classes of Inanna/Ištar. |

| 48 | Rather like the later maenads who follow Greek god, Dionysos (Harris 1991, p. 268; Zeitlin 1985, p. 79). |

| 49 | Any of these games can also become considerably more harmful or even deadly with the consumption of experience-altering substances. |

| 50 | Many of whom were castrates or eunuchs. For more, see (Lambert 1992; Budin 2023). |

| 51 | Particularly if the feminine assinnu were considered, even only sometimes and/or only performatively, women. |