Abstract

The Republic of Lithuania was one of several young nation-states that re-established or proclaimed their statehood in the aftermath of the First World War, following the dissolution of empires in Europe. The quest for cultural identity and attempts at its representation within the country, in the region, and on the international stage was the crucial element in the nation-building process, where cultural diplomacy played a pivotal role. For Lithuania, as for most European countries of that era, exhibitions, especially art exhibitions or art sections in the case of world shows (for instance, the Expo 1937 in Paris or the New York World’s Fair in 1939), served as a prominent means of expressing its identity. An overview of the Lithuanian state art exhibition strategy, the dynamics of its organizational process, the exhibition content, and their geographical reach are discussed in the article. To comprehensively grasp Lithuania’s cultural strategy and to reconstruct the network of its artistic connections, foreign art exhibitions organized at the state level and the acquisition of artifacts from these exhibitions for Lithuania’s national art collection, the M. K. Čiurlionis Art Gallery, are briefly reviewed as well.

Since the mid-19th century, exhibitions, particularly art exhibitions, have served as crucial tools of cultural diplomacy. In specific circumstances, such as during the dictatorships starting from the 1920s or throughout the Cold War era, they even assumed distinct characteristics of political propaganda. As succinctly highlighted in the introduction to one of the most recent overviews of international art exhibitions from the latter half of the 20th century Exhibitions beyond Boundaries. Transnational Exchanges through Art, Architecture, and Design 1945–1985 (2022), edited by Harriet Atkinson, Verity Clarkson, and Sarah A. Lichtman:

Exhibitions continued to be part of the armory of propaganda preceding and during the Second World War, aimed at both domestic audiences and international ones, and addressing both allies and enemies1.

In simpler terms, exhibitions served the dual purpose of consolidating a desired image of the country within its borders and disseminating it beyond them. Successful presentations on the international stage were seen by the states as triumphs achieved through ‘soft power’, instilling a sense of pride in the nation and, accordingly, strengthening the community and collective identity of its citizens. Therefore, the study of cultural diplomacy and its strategies is inherently intertwined with the examination of nationalism.

The critical history of exhibitions, starting in the 1960s, initially concentrated on major international exhibitions with worldwide significance, such as London’s Great Industrial Exhibition, the Venice Biennale, or the 1925 Paris International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts2. In recent decades, this historical perspective has expanded and branched into various narratives. Nevertheless, the propaganda dimension, where not only international exhibitions but also an individual country’s presentations abroad are seen as tools of ‘soft power’, continues to be one of the central ones, as it has been in the past3.

In this article, the period between the two World Wars4 is chosen for analysis, with a particular focus on the Republic of Lithuania—a young European nation. This choice is both emblematic of the time and region and holds contemporary relevance, especially considering the ongoing efforts to decolonize historical memory in post-communist countries and correct attitudes toward the past that influence contemporary decisions. This topic gains added significance in light of the Russian war against Ukraine. For Lithuania, which lost its statehood and became part of the Russian Empire in the late 18th century, regained independence in 1918 and then endured Soviet occupation from 1940 until 1990, the interwar period was marked by an intense quest for a collective identity, which played a vital role in resisting Sovietization during the subsequent colonization by the USSR. Furthermore, an examination of the Republic of Lithuania’s participation in exhibitions abroad during the interwar years provides valuable insights into why Soviet cultural policies, implemented in all occupied countries, successfully emphasized and preserved elements of traditional rural culture while deliberately suppressing representations of modern existence and aspirations for statehood restoration. From this viewpoint, this study aims not only to uncover how national profiles were constructed and collective identities were produced and negotiated but also to understand the formation of regional identity, the development and manifestation of artists’ professional self-awareness, and the importance given to the aspect of personal and collective representations.

In the article, within the constraints of its scope, the methods of critical source and historiography analysis and social culture theory are employed to explore the role and significance of art exhibitions in the cultural diplomacy of the independent Republic of Lithuania (1918–1940). The study delves into the dynamics, geographical reach, content, and both domestic and international assessments of these exhibitions. Additionally, it sheds light on the priorities of international bilateral cooperation by examining the geographical and stylistic characteristics of international art exhibitions held in Lithuania during that period. While Lithuania’s traditional rural art and crafts exhibitions abroad and participation in global exhibitions featuring such artifacts were noted as important elements of national cultural growth and dissemination outside the country even in the late Soviet era (Korsakaitė and Kostkevičiūtė 1982–1983; Žemaitytė 1988), they had not been subjected to systematic analysis until this research effort. With the aim of showcasing Lithuania’s modernization efforts, a list of Lithuanian modern art exhibitions abroad and international art exhibitions held within Lithuania’s borders has been compiled here, without attempting to reconstruct the specific content and context of each exhibition (Umbrasas and Kunčiuvienė 1980; Korsakaitė and Kostkevičiūtė 1982–1983). The theoretical approach adopted in this research is influenced in part by the concept of horizontal art history proposed by the Polish art historian Piotr Piotrowski over a decade ago. This concept encourages a reevaluation of the hierarchical, or vertical, narratives of cultural history, challenging the conventional opposition of ‘centre’ and ‘periphery’5.

1. On Historiography

The initial attempt to comprehensively examine Lithuanian international and foreign art exhibitions within the context of the state’s cultural policy was undertaken by Jolita Mulevičiūtė and the author of this article. Our research shed light on the significance of not only traditional folk art and rural crafts but also Lithuanian modern art exhibitions and international modern art exhibitions hosted in Lithuania in the context of the country’s cultural diplomacy6. In terms of artistic connections and influences, a particular focus was given to the Belgian (1936) and French (1939) modern art exhibitions7 held in Kaunas, the temporary capital of the country8. Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Poster announcing the French modern art exhibition in Vytautas Magnus Culture Museum in Kaunas with the reproduction of the landscape ‘Nice’ by Raoul Dufy, 1939; 110.5 × 62 cm. Courtesy of M. K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art, Kaunas.

Lithuania’s participation in the 1937 and 1939 Paris and New York World’s Fairs, as well as the 1931 tour of folk art and rural crafts exhibitions in Scandinavian countries, is considered the most significant in terms of visibility, both domestically and internationally (Jankevičiūtė 2005a, 2005b; Banytė 2012; Šatavičiūtė-Natalevičienė 2017; Jakaitė 2018; Mikuličienė 2019). These exhibitions garnered substantial attention from contemporaries. Additionally, the Monza International Exhibition of Decorative Arts in 1925 and exhibitions featuring Lithuanian traditional rural art and crafts, such as the showcases of carpets in the Louvre (1927) and Trocadéro (1935) and crafts in Berlin (1938), hold considerable importance. Traditionally, the significance of these exhibitions lay in the demonstration of uniqueness through the representation of folk art and crafts. This was interpreted as evidence of recognition of Lithuania’s traditional culture and, at the same time, the importance of the Lithuanian state in the European context. However, more recently, perspectives have evolved, and the analysis now includes considerations from the realms of anthropology, ethnography, and ethnology. Moreover, a colonial theory approach has started to be applied9.

As the post-Soviet Lithuanian humanities entered an international context, scholars began to have opportunities to compare Lithuania’s experiences with those of other European countries. This prompted a reevaluation of the strategies employed in organizing state-level exhibitions that aimed to blend representations of traditional rural culture with modernity, shaping Lithuania’s image both domestically and internationally, and an investigation of the reasons behind the prevalence of folklorism in these exhibitions (Jankevičiūtė 2003, 2005a, 2005b; Šatavičiūtė-Natalevičienė 2017; Jakaitė 2018). This shift in perspective led to a distinction between exhibitions with an ethnological focus and those where folkloric elements emerged as a result of the politicized expression of collective identity.

As is noted in historiography, within Lithuania, a shift in attitude toward the importance of art exhibitions occurred with exhibitions featuring Swedish decorative art and design (1934), Belgian (1936), Hungarian (1938), and French modern art (1939), as well as an Italian modern landscape painting exhibition (1938), all of which were facilitated through diplomatic channels. The political significance of these exhibitions is underscored by the fact that artworks from each of these exhibitions were purchased using funds from the Lithuanian state budget, and they were incorporated into the national art collection housed in the M. K. Čiurlionis Art Gallery in Kaunas (Jankevičiūtė 2003, pp. 58–59). Both the exhibitions themselves and the attention shown to them clearly reflect the priorities of Lithuania’s foreign policy. Additionally, art exhibitions from other countries hosted in Lithuania offer a fascinating case study within the broader context of interwar exhibitions and the cultural connections forged through them, complementing studies of neo-traditionalism and prompting a reevaluation of the idiom of modernism.

The increased focus on women’s studies in Lithuania in the early 21st century brought attention to the figure of Magdalena Avietėnaitė, a prominent protagonist of interwar Lithuanian cultural diplomacy, alongside other ideologists and organizers of interwar exhibitions. Raised in the USA, Avietėnaitė pursued her education in Switzerland and arrived in independent Lithuania in 1920. In 1926, she assumed a key role as the head of the Press Office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which coordinated Lithuania’s cultural representations abroad. (Lithuania did not establish a separate cultural propaganda institution in the first half of the 20th century.) Consequently, Avietėnaitė played a pivotal role in bringing together politicians, diplomats, and cultural figures who shared her ideological outlook to join the committees responsible for executing the directives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Avietėnaitė not only helped to shape the policy but also dictated the strategy for the preparation of Lithuanian exhibitions abroad. Avietėnaitė’s role in the realm of cultural diplomacy was recognized in the academic literature as early as the 1980s. She was often mentioned alongside another notable figure in this process, Paulius Galaunė, who served as the director of the national museum of art—M. K. Čiurlionis Art Gallery—from 1924, having completed his education at l‘École du Louvre, a renowned school for museologists, and held this position until the end of the Second World War as a director of the newly established Vytautas Magnus Culture Museum in Kaunas. It was thanks to the recent exhibition Light Through the Glass Ceiling: Magdalena Avietėnaitė (1892–1984), Creator of the Country’s Image, held by the M. K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art in Kaunas in the spring of 2023, that Magdalena Avietėnaitė’s name became widely known to the wider public in Lithuania10.

Avietėnaitė’s influence and contributions to the sphere of cultural diplomacy add new dimensions to the history of women’s emancipation not only in Lithuania and the Baltic countries but also in the broader European context. Her role underscores the important contributions of women in the male-dominated field of cultural diplomacy during the interwar period. The research into Avietėnaitė’s activities and their impact also contributes to the broader narrative of the contributions of Lithuanian Americans to the establishment of an independent Lithuanian state. This particular aspect of history has not received extensive exploration, even though it is widely acknowledged that Lithuanian Americans played a substantial role in various facets of Lithuania’s development, including its economy, sports, culture, and politics (according to demographic data of 1930, Chicago was home to 63,918 Lithuanians11, coming second in terms of Lithuanian residents globally, surpassed only by the then capital and largest city of the Republic of Lithuania, Kaunas). This seemingly small detail holds substantial significance in the context of the development of transnational cultural relations, which have become a focus of academic research today.

The research into Lithuanian exhibitions abroad has seen another significant shift, driven by the interest of the youngest generation of scholars in understanding the operation of Soviet soft power during the interwar period12. This topic had been marginalized after the fall of the Soviet regime, as it was unequivocally associated with the history of Soviet occupation. During the Soviet era, the prevailing narrative presented Soviet cultural influence as a positive force for developing local culture and integrating it into the broader culture of the USSR. However, contemporary researchers are reevaluating this perspective through the lens of post-colonial studies and deconstructing the previously positive assessments found in Soviet-era historiography regarding Soviet art exhibitions in Lithuania and the intentions of the Lithuanian Artists’ Union (established in 1935) in presenting modern Lithuanian art in Moscow and then Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) (Černiauskas and Radzevičiūtė 2022). This shift in perspective allows for a more nuanced assessment of the previously recorded impact of the Russian art exhibitions in Kaunas and their role in the dissemination of neo-traditionalism in Lithuanian art during the 1930s and helps us to understand the circumstances that facilitated the integration of Lithuanian artists into the Soviet cultural model, which began to be implemented starting from the summer of 1940 after the three Baltic countries—Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia—were invaded by Soviets (Cf. Jankevičiūtė 2008).

2. Lithuania Appears on the International Stage

For the first time, the name of the Lithuanian ethnic minority unknown to the international community gained some prominence at the Paris International Exposition in 1900, in which Lithuanian figures from the Lithuanian American diaspora and East Prussia or Lithuania Minor collaborated to establish a Lithuanian section, where they showcased handicrafts created by rural artisans and Lithuanian books, representing the culture of a people oppressed by the Russian Empire (Misiūnas 2006). These books were printed under special conditions, as printing Lithuanian publications in Latin characters and teaching in Lithuanian in schools had been banned by Russia since 1865, requiring the use of Cyrillic (the ban was in force until 1904). Books in Latin characters were printed abroad, primarily in East Prussia, and then smuggled into Lithuania. Russia saw the Lithuanian section at the Paris Exposition as a direct challenge, if only for the fact that Lithuania demonstrated its break from the empire’s influence and set up a separate exhibition. The organizers of the Lithuanian section also took measures to ensure the lasting impact of the exhibition. They arranged for some of the Lithuanian exhibits to become part of the Trocadéro Museum’s collection of ethnography of European peoples.

The establishment of the Lithuanian Art Society in Vilnius, the historical capital of Lithuania, in 1907 was a significant development that coincided with the liberalization reforms initiated in the Russian Empire after 1904–1905. This society not only supported the development and dissemination of contemporary art but also actively worked to promote local rural culture. However, the society’s efforts were primarily focused within the boundaries of the Russian Empire (the exception was an album showcasing drawings of traditional wooden wayside shrines and crosses that were also distributed outside the empire). All the society’s exhibitions, which were held annually in Vilnius until the outbreak of the First World War (two of them were moved to the second largest city of Lithuania, Kaunas, and one to Riga, the capital of neighboring Latvia, which had a significant Lithuanian community), consisted of two sections: one dedicated to contemporary art and the other to rural crafts13. The Lithuanian Art Society sent Lithuanian products to be showcased in exhibitions of handicrafts organized by the Central Board of Land Management and Agriculture of Russia. At the second exhibition of Russian crafts held in 1913, the society achieved significant recognition by winning a grand silver medal for a collection of fabric and sash drawings, as well as for its contribution to the development of fine crafts, and presented a small collection of items of Lithuanian crafts to the Vassily Dashkov Collection of Ethnography of the Peoples of Russia in Moscow (Jankevičiūtė 2009, pp. 30–31). While Lithuania was eager to present itself beyond the borders of the Russian Empire, the plans to participate in the exhibition of Russian fine crafts at the Wertheim trade house in Berlin in January 1914 did not materialize for reasons that remain unknown. Lithuanian folk art did find a presence outside of Lithuania in the form of an illustrated album titled Lietuviški kryžiai. Les croix lithuaniennes, published in 1912 and featuring an introduction by the political figure and medical doctor Jonas Basanavičius, along with drawings by the artist Antanas Jaroševičius. Published by the Lithuanian Art Society, this album was distributed to a wide range of recipients, including the Pope in the Vatican.

3. Design before Design: Lithuania’s Presence in the Second International Exhibition of Decorative Arts in Monza

After the conclusion of the First World War, it was traditional rural culture artifacts that played a crucial role in drawing international attention to the newly established state of Lithuania. Lithuania’s first foray onto the international stage occurred at the Second International Exhibition of Decorative Arts, which took place at Monza’s Villa Reale in 1925 (Cf. Pansera 1978, p. 30). At this exhibition, Lithuania showcased a range of items that represented its rich traditional culture: hand-woven fabrics, sashes, and wooden artifacts (such as ornamentally decorated work tools, household items, and Catholic saint sculptures). Figure 2. Additionally, there was a collection of the artist Adomas Varnas’s photographs of wooden village shrines and crosses that were still standing outdoors at that time. This presentation was both timely and well suited to the context of the event, as both the Italian provinces and the countries of Northern and Southern Europe sought to highlight their uniqueness by displaying traditional rural art and crafts. The installation created by Adomas Varnas was equally impressive as that of Romania and even surpassed the Polish presentation, which was primarily focused on the country’s participation in the International Exhibition of Decorative Arts held in Paris during the same year (Jakaitė 2018). However, despite the success of Lithuania’s exhibition at Monza’s Villa Reale, where most Lithuanian exhibits found buyers and as many as 32 Lithuanian works were featured in the exhibition’s catalog (Opere scelte 1926), and Lithuania and its folk art were additionally promoted in the book by the Italian journalist Giuseppe Salvatori, published in Italian, French, and English (Salvatori 1925a, 1925b, 1925c), there was a sense of disappointment among the Lithuanians who attended the event and saw the modern design displays of other countries. Everyone realized that Lithuania was unable to showcase even a single exhibit of modern design; in other words, Lithuania lacked the means to assert its modernity and was unprepared to compete in the cultural battle that required tangible evidence—examples of modern design in exhibitions of this nature, which had just crystallized into a distinct category of international exhibitions (Žemaitytė 1988, pp. 129–31). Lithuania found itself in a stage often referred to by Lithuanian design historians as ‘design before design’ (Jakaitė 2018), when individual artists created unique design items, including ornately decorated furniture in the art nouveau and art deco styles, as well as other objets d’art. However, these were one-of-a-kind pieces that were not suitable for mass production. With this factor in mind, during the Monza exhibition in 1925, the attention of Lithuanians was not primarily focused on the Deutscher Werkbund department, which required advanced industrial resources, the refined products of centuries-old Venetian glass manufactories, or the futuristic-style room furnished by Italian artist Fortunato Depero. Instead, they were drawn to the attractively designed innovations for mass consumption that were being produced by young national states. One of these states was Czechoslovakia, with which Lithuania actively cultivated cultural and economic cooperation ties across various sectors, taking it as a model. In 1933, when Lithuania received an invitation to participate in the Milan Triennale of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts and Architecture, which became the successor of the Monza exhibition, the country began to question its ability to compete effectively on an international stage in this type of event. However, with the benefit of hindsight, it is evident that if Lithuania had showcased its new architecture in Kaunas, the presentation would have been on a par with, for instance, Belgium, which Lithuania also tried to emulate in many ways. There were signs of improvement in the fields of crafts and design, as evidenced by the fittings and decorative details like wooden trim elements, metal grilles, doors, etc. Nonetheless, in the 1930s, Kaunas’s modernist architecture was not showcased to represent Lithuania’s achievements on the international stage, apart from individual reproductions of new public and industrial buildings in propaganda publications and sets of postcards distributed through Lithuanian embassies. This could have been influenced by the active debates at the time regarding the concept of a ‘national style’ in architecture, which may have led those responsible for representation to believe that Kaunas’s modernist architecture lacked the necessary distinctiveness needed to represent the newly reestablished state on the European map.

Figure 2.

Photographic display of the images of Lithuanian section in the Second International Exhibition of Decorative Arts at Monza’s Villa Reale, 1925. Courtesy of Adelė and Paulius Galaunė Memorial House, Kaunas.

4. The Dilemmas of National Modernism

At this point, it should be noted that there was a great deal of suspicion and reluctance toward the ideas and forms of modernism in Lithuania’s political and cultural circles. One significant reason was the association of the avant-garde with revolutionary leftist ideas. In Lithuania, as in other countries, there was a belief that avant-garde art not only disrupted the established cultural norms and values but also posed a potential threat to social stability and even the political order of the state. Another factor was the avant-garde’s global orientation, which rejected the emphasis on perceiving and demonstrating national identity that had been nurtured by nationalistic ideologies in Lithuania. As a result, it is easy to explain, for instance, why the poet Juozas Tysliava’s attempt to publish the Lithuanian international avant-garde magazine MUBA in various languages in Paris in 1928 received a lukewarm response in Lithuania (Jankevičiūtė 2008, pp. 45–47). Tysliava’s global vision appeared distant to his compatriots, who were more focused on showcasing their unique cultural identity, and consequently, few in Lithuania supported his ideas, and MUBA remained relatively unknown in the country; only a handful of copies of the first issue of the magazine are preserved in private and state collections, and even the second issue had to be obtained from the French National Library, as it has not yet been located in Lithuania. For a long time, there was disagreement over whether the magazine had two or three issues, with no consensus reached (in the Soviet era, research on such topics was hardly possible and later considered irrelevant). The entry in the electronic General Lithuanian Encyclopaedia still erroneously states that three issues of the magazine were published14. This detail reveals a paradoxical approach to the cultural heritage of modernism since Tysliava’s magazine represents one of the strongest connections between the Lithuanian artistic culture of the 1920s and the ideas and personalities that were central to the international avant-garde.

It is more difficult to explain why, at the official level, the efforts of the expressionist artist Adomas Galdikas to establish himself as part of the authoritative international École de Paris were ignored. Galdikas often referred to himself as ‘a man of the swamps’ and valued elements of folklorized animism or even wildness as essential aspects of his personal and broader Lithuanian identity, hoping that it would captivate the interest of the exoticism-loving Parisian art audience and his fellow artists (Jankevičiūtė 2024). In April 1931, Galdikas made an attempt to conquer the modernist art scene in Paris by presenting a collection of paintings featuring swamps, mounds, uprooted stumps, dwarf birches, witches, mermaids, and devils at the Galerie de l’Atelier Français. However, despite his efforts, this attempt cannot be considered entirely successful. Even though two of his paintings were acquired by the Musée du Luxembourg, and a book on his art was published in French with an introduction by the prominent art critic Waldemar George a few years later (George 1934), Galdikas’s endeavors can hardly be called successful. His monograph went largely unnoticed, and nowadays it is a bibliographic rarity in both Lithuania and France. His works in the collection of the Musée du Luxembourg were only briefly mentioned by contemporaries, and nowadays this fact is known to only a small group of art history specialists, although it could be considered a partial, unfulfilled, for reasons unknown, possibility of success.

Why did the artistic display of wildness with the means of expressionist painting, portraying Lithuania as an exotic country on the fringes of Europe, characterized by its retention of pagan beliefs and spells, as well as unique natural landscapes, not align with the official vision of the state? The reason is definitely not Galdikas’s preferred expressionist style, because other artists of this trend from the territories of Lithuania and Belarus, representatives of the École de Paris, predominantly Jews (Arbit Blatas aka Neemija Arbitblatas, Marc Chagall, Michel Kikoïne, Chaïm Soutine), received appreciation and recognition for their work by contemporaries in Lithuania. This would be confirmed by the correspondence between Paulius Galaunė, an ideologue and executor of Lithuanian cultural diplomacy, and the writer Jurgis Savickis, the Lithuanian diplomatic representative in Scandinavia, who resided in Stockholm, during the preparation of the French edition of Galaunė’s book on Lithuanian art. In 1931, thanks to Savickis’s efforts, a book on Lithuanian art was initially published in Swedish in Malmö. However, realizing that the distribution of the Swedish publication was quite limited, a French version was prepared, which was eventually released in 1934 (Galaunė 1931, 1934). To provide more space for the country’s modern culture in this updated version, Savickis encouraged Galaunė to move away from the artists of the old generation deeply rooted in the long nineteenth century and focus on the most recent talents. Among these, he particularly emphasized the works of the Lithuanian avant-garde artist Vytautas Kairiūkštis and the Kaunas Jewish painter Max Band (Maksas Bandas), adding that the publication could offer a more comprehensive representation of Jewish artists and include additional reproductions of their works15. In simpler terms, he was searching for Lithuanian artists who could be easily recognized abroad and associated with the popular art movements of their time: Kairiūkštis was seen as representing post-cubist painting and constructivism, while Band was linked to the École de Paris, a group that included many Jewish artists from Central and Eastern Europe. In this case, it can be assumed that Galaunė and Savickis were likely drawn to the idea of Jewish exoticism because they viewed Jewish traditional culture as something exotic, ‘the other’, or different from their own perspective. However, in the eyes of their contemporaries, Galdikas, the Lithuanian artist, may have appeared less modern and less internationally appealing, too focused on Lithuanian-specific aspects, and therefore too local.

It was easier and more convenient to showcase individuality using an instrument employed in other countries, i.e., through the lens of traditional rural culture. In other words, Lithuania chose a common 20th-century cultural diplomacy strategy that was both practical and accessible. Despite some efforts to modernize Lithuania’s image, folk art remained the primary tool in the arsenal of the Lithuanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and its affiliated exhibition organizers. This was complemented by the works of contemporary craftsmen who drew inspiration from folk traditions and artists who embraced a distinct national style, both of whom flourished in Lithuania during the 1930s. During the first half of the 20th century, many countries shared a general interest in ethnology and the unique aspects of their rural cultures. However, the vast majority of European nations did not exclusively rely on the presentation of traditional culture to represent themselves to the world. In this context, Lithuania’s approach could be considered somewhat exceptional.

6. Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia in Paris: Joint (Self-) Representations

The significance of rural culture in constructing the cultural identity and self-representation of the country was similarly understood in Latvia and Estonia. Therefore, it is not surprising that folk art and crafts played a pivotal role in uniting the three Baltic countries for a joint cultural presentation abroad. In 1935, a collaborative exhibition of the Baltic countries was inaugurated at the Museum of Ethnography in Trocadéro. Figure 4. The exhibition’s catalog was co-authored by Helmi Kurrik, an Estonian ethnographer renowned for her expertise in national costume and traditional cuisine, and Jurgis Baltrušaitis, a Lithuanian medievalist with a keen interest in primitive art (Kurrik and Baltrušaitis 1935). Henri Focillon, a French authority on art history and coincidentally Baltrušaitis’s professor and father-in-law, wrote the introduction. Focillon’s name held considerable renown in the French public sphere, making his involvement essential and desirable for the organizers. His authority lent additional prestige to both the exhibition and its coordinators, Kurrik and Baltrušaitis. Kurrik was a female scholar, and Baltrušaitis was a young 32-year-old researcher who had not yet established significant academic standing. Entrusting them with the responsibility of curating the cultural representation of the Baltic countries reflected a deliberate effort to harness fresh talent for cultural diplomacy, tapping into the potential of emerging cultural professionals.

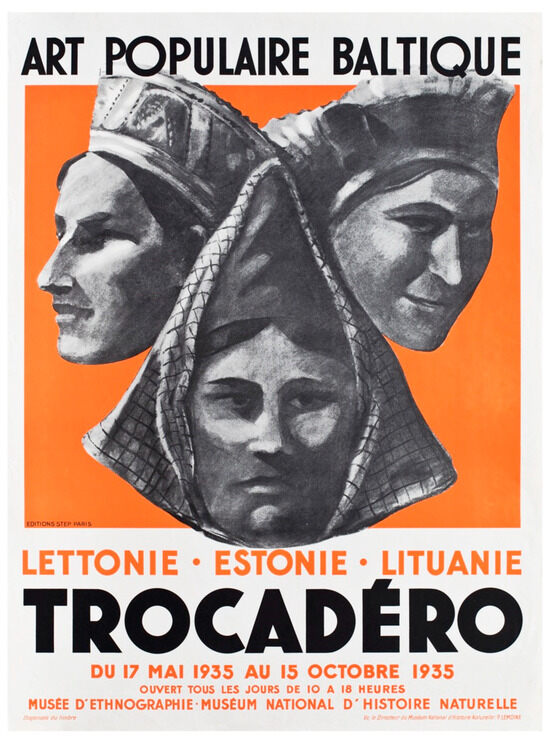

Figure 4.

Poster announcing the exhibition of Baltic Folk Art in Trocadéro Museum from 17 May 1935 to 15 October 1935; 80 × 59.5 cm. Courtesy of M. K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art, Kaunas.

The joint endeavor of the three Baltic countries in Paris was considered a resounding success, earning them the highest state accolades. In 1936, both Kurrik and Baltrušaitis were honored with orders from all three participating nations—Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. A portion of the exhibited items was added to the Trocadéro Ethnography Museum’s collection after the exhibition, in hopes of piquing the interest of the museum’s curators and visiting scholars in the cultures of the Baltic countries. Lithuanians believed that this invitation to augment the Trocadéro Museum’s collection of folk art and crafts, accumulated since the 1900 Paris Exhibition, demonstrated France’s special attention to Lithuanian traditional culture and its distinctiveness. This belief was further reinforced by a gracious gesture from Georges Henri Rivière, the then-director of the Trocadéro Museum (and the founder of the new Musée national des Arts et Traditions populaires in 1937). In a letter of gratitude to Galaunė, he expressed his desire to visit Kaunas and view the collections of the national gallery of art (Jankevičiūtė 2003, p. 55).

The experience of participating in the Trocadéro exhibition motivated the Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians to incorporate displays of folk art and crafts into their joint presentation at Expo 1937 in Paris. However, at this juncture, we can observe a shift toward public relations and the deliberate incorporation of exotic elements to capture the attention of visitors.

The three Baltic neighbors shared a joint pavilion in Paris. Figure 5. The pavilion’s understated modernist architecture, designed by the Estonian architect Alexander Nürnberg, portrayed the Baltic countries as modern nation-states. However, in separate halls, each of them aimed to emphasize their uniqueness. Lithuania openly embraced the imagery of a mysterious land of forests and meadows, and at the center of the display stood a sculpture of Christ in Sorrow, an enlarged replica of the traditional wooden Christ figure commonly found in rural culture. Figure 6. In the eyes of contemporaries, this sculpture symbolized not only the country’s suffering in its quest for independence but also its pursuit of political, economic, and cultural autonomy (Surdokaitė-Vitienė 2015, pp. 107–10). The statue, based on the model created by the sculptor Juozas Mikėnas, who had studied in Paris, was carved from oak, a symbolic tree for Lithuania, by woodwork instructors from local craft schools. Behind the Christ in Sorrow sculpture, a three-part triptych by the artist Adomas Galdikas depicted scenes of summer agricultural work, including rye and vegetable harvesting. The hall’s walls were lined with rustic-style furniture and display cases filled with fabrics and ceramics. Unlike previous representations, these were not authentic examples of folk crafts. According to the Polish art historian Piotr Korduba, this was a unique form of folklore—no longer a subject of ethnographic study but rather a transformed version intended for sale to urban residents, particularly the cultural elite, and official institutions looking to showcase themselves through the lens of national uniqueness (Korduba 2013, p. 13). Visitors were welcomed by young Lithuanian beauties dressed in traditional costumes or, more precisely, stylized versions of them. Tourist posters, commissioned by the Lithuanian Railways, depicted an idealized and appealing image of Lithuania, featuring blooming gardens, unique wooden rural architecture, and brick cities, encouraging visitors to experience Lithuania first-hand. However, beneath this picturesque façade, a fierce competition for buyers was underway. All three Baltic countries placed particular emphasis on marketing their agricultural products, including meat and dairy. This competitive atmosphere led to tensions between Lithuania and Latvia during the exhibition (Banytė 2012, pp. 31–32).

Figure 5.

Pavilion of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania (architect Alexander Nürnberg) in the Paris World Fair of 1937. Photograph from private archive.

Figure 6.

Lithuanian hall in the pavilion of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania in the Paris World Fair of 1937. Photograph from a private archive.

Younger generations in Lithuania and Lithuanians in the United States criticized the way Lithuania was presented in Paris, urging a shift toward showcasing the country’s modern accomplishments and moving away from archaic exoticism. However, these critics may have overlooked the fact that the concept of archaic exoticism had evolved into a modern national style of design, which was well received internationally and had gained popularity in many countries (Jankevičiūtė 2005b; Banytė 2012; Surdokaitė-Vitienė 2015).

7. Modern Graphic Art Competes for International Recognition

Amid the debates surrounding Lithuania’s image and the necessity of modernization, the international press and graphic art specialists largely overlooked the well-deserved and significant attention given to Lithuanian bibliophile books. These books effectively represented the achievements of modern Lithuania, spanning both the realms of art and the printing industry. Figure 7. No one publicly celebrated or expressed their satisfaction that it was after the Paris exhibition that the respected book history and aesthetics yearbook Maso Finiguerra, published by the Italian bibliophile and press historian Lamberto Donati, became interested in the works of Lithuanian graphic artists and featured a richly illustrated review of the new Lithuanian graphic arts, authored by the artist Mečislovas Bulaka (Bulaka 1938). Figure 8.

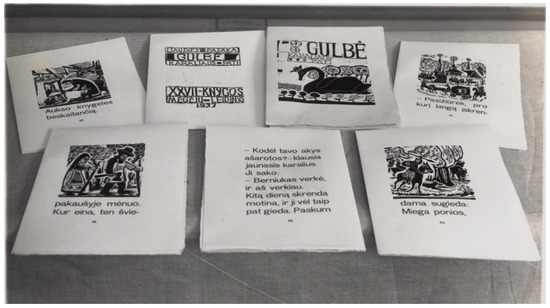

Figure 7.

Fragment of the display of Lithuanian books in the Lithuanian hall in the Paris World Fair of 1937 with the spreads of folk-tale ‘Swan–Wife of the King’ illustrated and designed by Viktoras Petravičius. Photograph from private archive.

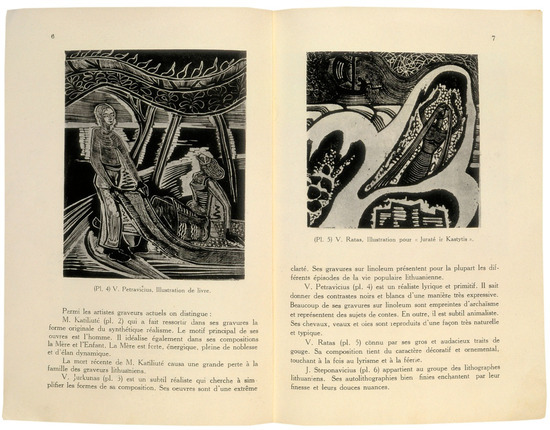

Figure 8.

Double page spread of the article ‘L’art graphique lithuanien’ by Mečislovas Bulaka published in the magazine Maso Finiguerra. Rivista della stampa incisa e del libro ilustrato, vol. 3, 1938, pp. 54–62 (Bulaka 1938).

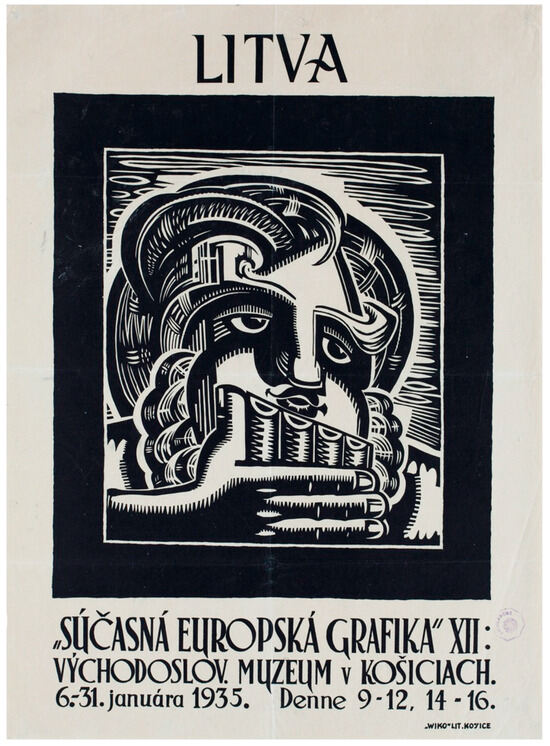

Adequately assessing the presentation of print design in Paris and the Lithuanian graphic art exhibition in the series of modern European graphic art exhibitions at the Museum of Eastern Slovakia in Košice17 was hindered by an outdated perspective that considered graphics inferior to painting in terms of its significance and societal impact. Figure 9. Consequently, it was often relegated to the cultural periphery and viewed as lacking the critical weight to represent a nation’s culture effectively. However, when we set aside this view rooted in the traditional academic hierarchy of art forms, it becomes evident that graphic art was, in fact, the most dynamic medium within the Lithuanian visual culture during the interwar period. Analyzing graphic representations allows us to bridge the heritage of interwar Lithuanian art with global developments in visual art, demonstrating the contemporary and mature nature of Lithuanian art. Unfortunately, this recognition was often overshadowed by the undue emphasis on the radical avant-garde.

Figure 9.

Poster of the Lithuanian graphic art exhibition from the cycle ‘European Contemporary Graphic Art’ in the Eastern Slovakian Museum at Košice, designed by Adomas Galdikas, 1935; 63.5 × 46.5 cm. Courtesy of M. K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art, Kaunas.

For the same reason, the exchange of modern art exhibitions among the Baltic countries lacks a clear place in the history of interwar Lithuanian cultural diplomacy. In 1937, Lithuania presented itself in Latvia and Estonia, and in the same year, it hosted art exhibitions from these countries in Kaunas (Cf. Jankevičiūtė 2003, pp. 59–64; Kunčiuvienė and Mikulėnaitė 2020, pp. 89–90). This geographical spread of exhibitions highlights two significant points: the regional relevance of Lithuanian art and the country’s geopolitical orientation. In the case of Moscow, this orientation was also intertwined with the strong interests of the USSR in the Baltic countries and the actions taken to bolster its influence in Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. The aforementioned art exhibitions were no longer under the coordination of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs but were managed by the Lithuanian Artists’ Union, a professional organization of art creators funded through the state budget and subordinate to the Ministry of Education, established in 1935. However, in the eyes of the country’s politicians and cultural figures, modern art exhibitions did not hold the same significance as the mobile traditional folk art exhibition in the Scandinavian countries in 1931 and the joint exhibition of the three Baltic countries in Trocadéro (1935), not to mention the Lithuanian sections at the world exhibitions in Paris and New York.

However, the success of Lithuanian bibliophile books in Paris had an impact on the assessments made by certain figures involved in Lithuanian cultural diplomacy. The memory of the prohibition of the Latin script and the Lithuanian language in the Russian Empire, which remained a constant topic of public discussion, along with the concerns expressed by influential representatives of the country’s cultural and political elite regarding the state of book art, likely contributed to this shift. As interest in book art and graphics grew, it became apparent that this interest was not unique to Lithuania but was shared by other European countries as well. Consequently, graphic art and print design emerged as suitable mediums for Lithuania’s international representation, particularly in the context of broader attention to propaganda and its various media forms.

Lithuania established a section of publications and prints in its part of the pavilion at the Paris International Exhibition, a decision influenced by several factors: first, it was in line with the common requirements of participating countries, and second, it drew from the experience gained in the 1900 exhibition when publications in the Lithuanian language played a significant role in Lithuania’s presentation. Additionally, Lithuania’s participation in the international exhibition of the Catholic press in the Vatican in 1936 may have contributed to this approach. During the preparation of the Lithuanian press showcase in the 1937 Paris exhibition, probably for the first time, public organizations actively collaborated with state enterprises (such as the XXVII Society of Book Lovers, which brought together Lithuanian bibliophiles and published its own publications) (Jankevičiūtė 2008, pp. 116–18). This emphasis on the press presentation underscored its importance for the country’s image. Furthermore, the decision to exhibit the works of Lithuanian graphic designers who had received awards in Paris to the Lithuanian public highlighted the significance of this presentation. Those who could not travel to Paris had the opportunity to view these exhibits at the Third Exhibition of the Lithuanian Artists’ Union in Kaunas in the autumn of 1937 (III rudens dailės paroda 1937, pp. 21–28). This exhibition marked a significant departure from previous interwar exhibitions by showcasing the finest work produced by Lithuanian printing houses. It encompassed not only books but also smaller prints and posters, providing visitors with an opportunity to appreciate the importance of the physical format of a print in enhancing its aesthetic quality.

As artists began to sense the increasing attention from the public and government representatives toward their work, they took initiatives to represent the country’s modern art through graphic artifacts. The Daira group (an abbreviation for Dailininkai realistai-aktyvistai—The Realist and Activist Artists), which had split from the state-supported and -controlled Lithuanian Artists’ Union in 1940, made efforts to publish an illustrated publication about Lithuanian graphic art in both Lithuanian and French—the official language of the international diplomacy at the time (Umbrasas and Kunčiuvienė 1980, p. 179). The texts for this publication were commissioned to the artist Mečislovas Bulaka, who collaborated with Maso Finiguerra, and the young yet already recognized art historian Mikalojus Vorobjovas. Vorobjovas had some experience in the realm of cultural diplomacy, having authored and published a monograph in German on the music and art of the national classic of modern culture Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis. He also effectively managed the international dissemination of this publication.

In a limited edition of 265 copies, Daira published a livre d’artiste by Viktoras Petravičius, featuring his linoleum-carved Lithuanian folk tale titled ‘Marti iš jaujos’ (The Bride from the Barn) along with a separately printed French translation. The aim was for this book to serve as a representative work of modern Lithuanian culture, intended to pique the interest of book enthusiasts and professionals beyond Lithuania’s borders. However, these plans were abruptly halted by the Soviet military invasion in June 1940, followed by the occupation of Lithuania.

These efforts signified an impending shift in the country’s cultural diplomacy strategy. However, the anticipated breakthrough did not materialize until the onset of the Second World War. Lithuania persisted in portraying itself as an agrarian nation steeped in medieval traditions. Yet, within the broader context of rising nationalism, this strategy of anchoring the country’s image in the realm of agrarian culture did not provoke significant opposition.

8. Controversies of Lithuanian Self-Representation in the Late 1930s and the New York World Fair of 1939

The image of a country deeply rooted in rural culture harmoniously aligned with the First International Crafts Exhibition held in Berlin in 1938. Lithuanian national costumes, handcrafted textiles, wood carvings, amber jewelry, and rural pottery items found a fitting place in this propaganda show that promoted nationalism and traditional craftsmanship. In the exhibition’s Hall of Honour, the artist and weaving instructor Anastazija Tamošaitienė, dressed in traditional costume, sat at a handloom, demonstrating to visitors the traditional weaving techniques still practiced in rural Lithuania. However, Lithuania stood out among the few countries that declined to showcase industrially manufactured design products in Berlin, opting not to participate in the exhibition’s ’Industry Assists the Artisan’ section (Šatavičiūtė-Natalevičienė 2017). While the exhibition organizers may not have emphasized this point, it did not escape notice in Lithuania, reigniting the discussion about the need for a change in the country’s image.

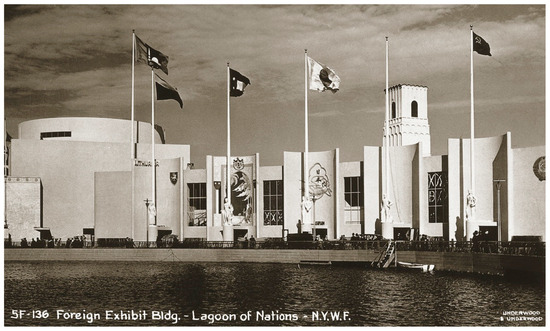

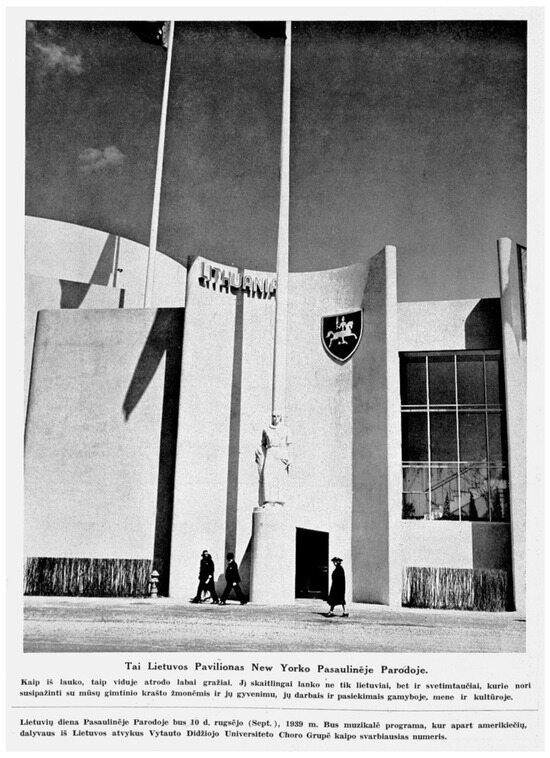

The tension between showcasing ethnic identity and the necessity of demonstrating Lithuania’s modernization came to a head on the eve of the 1939 New York World’s Fair, titled ‘The World of Tomorrow’. Lithuania chose to focus its presentation on themes related to youth education and the growth of the country’s food industry, set against a backdrop of artworks emphasizing the grandeur of the medieval empire—Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In the pavilion, situated by the Lagoon of Nations and featuring standard architecture, visitors were greeted outside by a neoclassical allegorical sculpture representing Lithuania (created by sculptor Juozas Mikėnas). Figure 10 and Figure 11. Inside, they were met with an aggressively designed plaster cast of the statue of Vytautas the Great, a 15th-century ruler of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (sculpted by Vytautas Kašuba). Additionally, seven painted panels adorned the pavilion, depicting pivotal moments in Lithuania’s statehood, from the coronation of the medieval ruler Mindaugas in the 13th century to the declaration of independence in 1918. These artworks were produced by recognized local artists from various generations, all of whom were instructed to adhere as closely as possible to a unified artistic style (Jankevičiūtė 2003; Mikuličienė 2019). Even a modernist-style panel (created by artist Stasys Ušinskas) dedicated to the history of Lithuanian education failed to significantly alter the perception of the exhibition. Critics, who were primarily concerned with the retrogressive and mythological depictions of history in the presentation, largely overlooked it, dismissing it as mere decorative ornamentation. As the New York Expo continued, Lithuania was drawn into the tumultuous events of the Second World War, effectively putting an end to all discussions regarding the country’s image and its representation through cultural diplomacy efforts abroad.

Figure 10.

Group of national pavilions on the shore of the Lagoon of Nations in New York’s World Fair of 1939. Courtesy of M. K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art, Kaunas.

Figure 11.

Lithuanian pavilion on the shore of the Lagoon of Nations in New York’s World Fair of 1939 adorned with the coat of arms of Lithuanian state and the allegorical image of Lithuania by sculptor Juozas Mikėnas, installed in front of the building. Courtesy of M. K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art, Kaunas.

The Soviet Empire’s approach toward the inhabitants of the occupied territories relied on classical criteria, which encouraged the highlighting of the exotic aspects of indigenous culture. Emphasizing tradition and rural cultural heritage was convenient for the communist regime, as it facilitated the introduction of a discourse that naturally suppressed notions of statehood and, consequently, the pursuit of independence. Accordingly, certain aspects of Lithuania’s cultural diplomacy strategy developed during the interwar period persisted during the period of Soviet occupation. However, a comprehensive exploration of this topic warrants a more detailed presentation and falls outside the scope of this article.

Funding

Funded by the Lithuanian Institute for Culture Research.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Atkinson (2022, p. 6). The monograph Tymkiw (2018) can be considered an example of the anatomy of propaganda exhibitions during the totalitarian regime era. |

| 2 | Classical research of this kind: Alloway (1969), Allwood (1977), Greenhalgh (1988). |

| 3 | The latter statement can be substantiated, for example, by the historiography of interwar foreign exhibitions of the Republic of Poland, a country culturally and geographically close to Lithuania, which reveals the locally relevant issues of exhibition research, shedding light on the not yet sufficiently researched exhibition strategy of the Republic of Lithuania in the interwar period: Sosnowska (2009, 2012); Luba (2012), pp. 253–81; Kuhnke and Badach (2013); Kossowska (2017, 2020); Bartosz Dziewanowski-Stefańczyk, ‘World Fairs as a Tool of Diplomacy: Interwar Poland.’ Leerssen and Storm (2022), pp. 300–28. |

| 4 | The period of twenty years between the two World Wars is highly representative in analysing the development of the image-building strategies of the nation states; one of many examples of this trend is Devos (2015). |

| 5 | Jakubowska and Radomska (2022): ‘Introduction’. |

| 6 | Jankevičiūtė (1998); Mulevičiūtė (2001); Jankevičiūtė (2003): chapters on propaganda and representation and on the history of the country’s museums. |

| 7 | Mulevičiūtė (2001); Jankevičiūtė (2003). In the permanent exhibition of the Mykolas Žilinskas Gallery, the foreign art branch of M. K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art (currently under reconstruction), a section of Belgian art was installed. It showcased the works acquired by the Kaunas Museum from the exhibition of Belgian art and donated by the exhibition organizers. The significance of Belgium and its art for the culture of the Baltic countries is also evident from the attention to mutual relations with Belgium in Latvia: in 2013, the Art Museum Riga Bourse hosted an exhibition of Belgian art titled Impressions and Parallels. Belgian and Latvian Painting from the Collection of the Latvian National Museum of Art. First Half of 20th Century, showcasing a collection donated by the Belgian government to Latvia after the exhibition of Belgian art in Riga in 1932, which in the interwar years was exhibited in the Riga Castle: https://studylib.net/doc/7695745/latvijas-nacionālais-mākslas-muzejs (accessed 6 August 2023); a catalogue presenting the cultural links between Latvia and Belgium was also published in 2013: Brasliņa (2013). |

| 8 | From 1922, the historical capital of Lithuania Vilnius was incorporated into the Republic of Poland and became part of the Republic of Lithuania only for a brief period in the autumn of 1939, when Poland was occupied by Germany’s Wehrmacht and the Soviet forces. For that reason, the country’s main governmental and cultural institutions in the interwar period were established and operated in Kaunas, which was also the centre of official culture. |

| 9 | Matulytė (2018), Lebednykaitė (2020). A characteristic symptom of the changed perspective is the relocation of a part of Lithuanian exhibits during the restructuring of the Trocadéro Museum in Paris (Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, reorganized into the Musée de l’homme by Paul Rivet in 1937) into the Museum of Civilisations in Marseille (MuCEM) established in 2013. |

| 10 | |

| 11 | https://www.vle.lt/straipsnis/cikagos-lietuviai/ (accessed 4 August 2023). |

| 12 | A symptomatic text quite representative of this perspective: Červonaja (1977). |

| 13 | For more see Laučkaitė (2009): from 70. |

| 14 | https://www.vle.lt/straipsnis/muba/ (accessed 5 August 2023); the same erroneous information is given in the electronic Encyclopaedia of Lithuanian Literature: https://www.literatura.lt/enciklopedija/m/muba/ (accessed 5 August 2023). |

| 15 | Letter of Jurgis Savickis to Paulius Galaunė from 28 August 1933. Department of the Manuscripts of the Library of Vilnius University, f. 132, b. 59, l. 37. |

| 16 | Sigurd Erixon, [intro], Utställning… (Utställning av Litauisk Folkkonst 1931a, pp. 3–5); Thor B. Kielland, [intro], Utstilling… (Utstilling av Litauisk Folkekunst 1931); Vilhelm Slomann, [intro], Litauisk Folke (Litauisk Folkekunst 1931); Sven T. Kjellberg, [intro], Folklig… (Folklig konst Litauen 1931); Ernst Fischer, [intro], Utställning… (Utställning av Litauisk Folkkonst 1931b). |

| 17 | This exhibition was mentioned in a synthetic overview of Lithuanian art of the first half of the 20th century published in the Soviet era (Korsakaitė and Kostkevičiūtė (1982–1983)); however, the authors left out its context, which was first briefly discussed in the book: Jankevičiūtė (2008, pp. 64–67). |

References

- Alloway, Lawrence. 1969. The Venice Biennale 1895–1968: From Salon to Goldfish Bowl. London: Faber and Faber. [Google Scholar]

- Allwood, John. 1977. The Great Exhibitions. London: Studio Vista. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, Harriet A. O., ed. 2022. Exhibitions beyond Boundaries. Transnational Exchanges through Art, Architecture, and Design 1945–1985. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Banytė, Miglė. 2012. Tautų arenoje. Paryžius 1937 [In the Realm of Nations. Paris 1937], Exhibition Catalogue. Kaunas: Nacionalinis M. K. Čiurlionio muziejus. [Google Scholar]

- Brasliņa, Aija, ed. 2013. Latvija–Beļģija: Mākslas sakari 20. gadsimtā un 21. gadsimta sākumā. Latvia–Belgium: Art Relations in the 20th Century and in the Beginning of the 21st Century. Riga: Latvian National Art Museum–Neputns. [Google Scholar]

- Bulaka, Mečislovas. 1938. L’art graphique lithuanien. Maso Finiguerra. Rivista della stampa incisa e del libro ilustrato 3: 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Černiauskas, Norbertas, and Gabrielė Radzevičiūtė, eds. 2022. Ribos ir paraštės: Socialinė kritika tarpukario Lietuvoje [Margins and Boundaries: Social Criticism in Interwar Lithuania], Exhibition Catalogue. Vilnius: Lietuvos nacionalinis dailės muziejus. [Google Scholar]

- Červonaja, Svetlana. 1977. Lietuvių dailės ryšiai [Lithuanian Art Connections]. Vilnius: Vaga. [Google Scholar]

- Devos, Rika A. O., ed. 2015. Architecture of Great Expositions 1937–1959. Messages of Peace, Images of War. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Erixon, Sigurd. 1931. ‘Lietuvių liaudies meno paroda Stokholme’ [Exhibition of Lithuanian folk art in Stockholm]. Naujoji Romuva 5: 109–10. [Google Scholar]

- Folklig konst Litauen. Samlingar från Ciurlionies galleri k Kaunas. 10 Oktober–10 November 1931 [Lithuanian Folk Art. Collections from the Čiurlionis Gallery in Kaunas. October 10–November 10, 1931], Exhibition Catalogue. 1931. Göteborg: Göteborg Museum.

- Galaunė, Paulius. 1931. Litauens konst [Lithuanian Art]. Text by Paulius Galaunė and Justinas Vienožinskis. Malmö: John Kroon. [Google Scholar]

- Galaunė, Paulius. 1934. L’art lithuanien. Malmö: John Kroon. [Google Scholar]

- George, Waldemar. 1934. Galdikas [series ‘Les Peintres Contemporains’]. Paris: Éditions Arts et Lettres. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, Paul. 1988. Ephemeral Vistas: The Expositions Universelles, Great Exhibitions and World’s Fairs, 1851–1939. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- III rudens dailės paroda [The Third Autumn Exhibition of Art], Exhibition Catalogue. 1937. Kaunas: Lietuvos dailininkų sąjunga.

- Jakaitė, Karolina A. O., ed. 2018. Daiktų istorijos. Lietuvos dizainas 1918–2018. Stories of Things. Lithuanian Design 1918–2018, Exhibition Catalogue. Vilnius: Lietuvos dailės muziejus. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowska, Agata, and Magdalena Radomska, eds. 2022. Horizontal Art History and Beyond. Revising Peripheral Critical Practices. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jankevičiūtė, Giedrė. 1998. Art deco Lietuvoje [Art Deco in Lithuania], Exhibition Catalogue. Kaunas: Nacionalinis M. K. Čiurlionio dailės muziejus. [Google Scholar]

- Jankevičiūtė, Giedrė. 2003. Dailė ir valstybė: Dailės gyvenimas Lietuvos Respublikoje 1918–1940 [Art and State: Artistic Life in Lithuanian Republic 1918–1940]. Kaunas and Vilnius: Nacionalinis M. K. Čiurlionio dailės muziejus–Kultūros, filosofijos ir meno institutas. [Google Scholar]

- Jankevičiūtė, Giedrė. 2005a. ‘Kryžių ir rūpintojėlių šalis ar moderni Europos valstybė. Lietuva XX a. pirmosios pusės tarptautinėse parodose’ [A country of crosses and [statues of the] Christ in Sorrow, or a modern European state. Lithuania in international exhibitions of the first half of the 20th century]. In Reprezentacijos iššūkiai. Challenges of Representation. Edited by Erika Grigoravičienė and Laima Kreivytė. Vilnius: AICA Lietuvos sekcija, pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Jankevičiūtė, Giedrė. 2005b. Lithuania in the International Exhibitions of the 1920s and 1930s. In Neue Staaten—Neue Bilder? Visuelle Kultur im Dienst staatlicher Selbstdarstellung in Zentral- und Osteuropa seit 1918. Edited by Arnold Bartetzky, Marina Dmitrieva and Stefan Troebst. Köln, Weimar and Wien: Böhlau Verlag, pp. 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Jankevičiūtė, Giedrė. 2008. Lietuvos grafika 1918–1940. The Graphic Art in Lithuania 1918–1940. Vilnius: E. Karpavičiaus leidykla. [Google Scholar]

- Jankevičiūtė, Giedrė. 2009. ‘Lietuvių dailės draugija ne vien per nacionalinio atgimimo prizmę’ [The Lithuanian Art Society not only through the prism of national revival]. Lietuvos dailės muziejaus metraštis 14: 26–40. [Google Scholar]

- Jankevičiūtė, Giedrė. 2024. The image of the swamp: About borders, boundaries, influences and transformations in Lithuanian modernism. In Swamps and the New Imagination. Edited by Nomeda Urbonas, Gediminas Urbonas and Kristupas Sabolius. London: Sternberg Press, Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Korduba, Piotr. 2013. Ludowość na sprzedaż. Towarzystwo Popierania Przemysłu Ludowego, Cepelia, Instytut Wzornictwa Przemysłowego [Folklore for Sale. The Association for the Promotion of Folklore Industry, Cepelia—The Folk and Artistic Industry Headquarters, the Institute of Industrial Design]. Warszawa: Fundacja Bęc Zmiana, Narodowe Centrum Kultury. [Google Scholar]

- Korsakaitė, Ingrida, and Irena Kostkevičiūtė, eds. 1982–1983. XX a. lietuvių dailės istorija, 1900–1940 [History of the 20th Century Lithuanian Art, 1900–1940]. Vilnius: Vaga, vols. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Kossowska, Irena. 2017. Politicized aesthetics: German art in Warsaw of 1938. Art History & Criticism/Meno istorija ir kritika 13: 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossowska, Irena. 2020. ‘Strategia państwowej autoreprezentacji: Sztuka ZSRS w Warszawie’ [Strategy of the representation of the state: Art of USSR in Warsaw]. Rocznik Humanistyczny 4: 205–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnke, Monika, and Artur Badach, eds. 2013. Sztuka i dyplomacja. Związki sztuki i polskiej dyplomacji w okresie nowożytnym [Art and Diplomacy. Relationships between Art and Polish Diplomacy in the Modern Period]. Warszawa: Ministerstwo Spraw zagranicznych i Stowarzyszenie Historyków Sztuki. [Google Scholar]

- Kunčiuvienė, Eglė, and Ema Mikulėnaitė, eds. 2020. Antanas Gudaitis: Tekstai ir vaizdai [Antanas Gudaitis: Texts and Images]. Vilnius: Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus. [Google Scholar]

- Kurrik, Helmi, and Jurgis Baltrušaitis, eds. 1935. Guide de l’exposition d’art populaire baltique: Estonie, Lettonie, Lituanie, Exhibition Catalogue with Introduction by Henri Focillon. Paris: Musée d’etnographie du Trocadéro. [Google Scholar]

- Lamm, Carl Robert A. O., ed. 1927. Les tapis. Première exposition Europe septentrionale et orientale: Finlande, Lithuanie, Norvège, Pologne, Roumanie, Suède, Ukraine, Yougoslavie, Exhibition Catalogue. Paris: Musée des arts décoratifs. [Google Scholar]

- Laučkaitė, Laima. 2009. Art in Vilnius 1900–1915. Vilnius: Baltos lankos. [Google Scholar]

- Lebednykaitė, Miglė. 2020. ‘Lietuvių etnografijos rinkinys Europos ir Viduržemio jūros civilizacijų muziejuje Marselyje (MuCEM), Prancūzijoje’ [Lithuanian ethnographic collection at the Museum of civilisations of Europe and the Mediterranean (MuCEM) in Marseille, France]. Būdas 2: 56–73; 3: 32–44. [Google Scholar]

- Leerssen, Joep, and Eric Storm, eds. 2022. World Fairs and the Global Moulding of National Identities: International Exhibitions as Cultural Platforms, 1851–1958 [National Cultivation of Culture]. Leiden and Boston: Brill, vol. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Litauisk Folkekunst: Udstiling udlaant af Čiurlionies museum i Kaunas. April–Maj 1931 [Exhibition of Lithuanian Folk Art from the Čiurlionis Gallery in Kaunas. April–May 1931], Exhibition Catalogue. 1931. Kjøbenhavn: Det Danske Kunstindustrimuseum.

- Luba, Iwona. 2012. Duch romantyzmu i modernizacja. Sztuka oficjalna Drugiej Rzeczpospolitej [The Spirit of Romanticism and Modernisation. Official Art of the Second Polish Republic]. Warszawa: Neriton. [Google Scholar]

- Matulytė, Margarita. 2018. ‘XIX a. etnografija Lietuvos kolonizavimo procese’ [19th century etnography in the process of the colonisation of Lithuania]. In Vakarykščio pasaulio atgarsiai: Mokslinių straipsnių rinkinys, skirtas Lietuvos valstybės atkūrimo 100-osioms metinėms. Edited by Margarita Matulytė, Romualdas Juzefovičius and Rimantas Balsys. Vilnius: Lietuvos dailės muziejus, Lietuvos kultūros tyrimų institutas, pp. 296–305. [Google Scholar]

- Mikuličienė, Irena. 2019. Lietuva 1939 metų Niujorko pasaulinėje parodoje [Lithuania in the 1939 New York World Fair], Exhibition Catalogue. Vilnius: Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus. [Google Scholar]

- Misiūnas, Remigijus. 2006. Lietuva pasaulinėje Paryžiaus parodoje 1900 metais [Lithuania at the 1900 Paris International Exhibition]. Vilnius: Versus aureus. [Google Scholar]

- Mulevičiūtė, Jolita. 2001. Modernizmo link: Dailės gyvenimas Lietuvos Respublikoje 1918–1940 [Towards Modernism: Artistic Life in Lithuanian Republic 1918–1940]. Kaunas and Vilnius: Nacionalinis M. K. Čiurlionio dailės muziejus-Kultūros, filosofijos ir meno institutas. [Google Scholar]

- Opere Scelte. Seconda Mostra Internazionale Delle Arti Decorative. Monza—1925, Exhibition Catalogue. 1926. Milano: Casa editrice ‘Alpes’.

- Pansera, Anty. 1978. Storia e cronaca della Triennale. Milano: Longanesi. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatori, Giuseppe. 1925a. L’arte rustica e popolare in Lituania. Milano: Casa Editrice G. E. A. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatori, Giuseppe. 1925b. L’art rustique et populaire en Lithuanie. Milano: Casa Editrice G. E. A. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatori, Giuseppe. 1925c. Rustic and Popular Art in Lithuania. Milano: Casa Editrice G. E. A. [Google Scholar]

- Šatavičiūtė-Natalevičienė, Lijana. 2017. Der Zug nach Paris: Das Bild von Litauen. In Fortsetzung folgt: Im der Zuge der moderne. Edited by Giedrė Jankevičiūtė and Nerijus Šepetys. Vilnius: Lithuanian Culture Institute, pp. 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sosnowska, Joanna M., ed. 2009. Wystawa paryska 1937 [1937 Paris International Exhibition]. Warszawa: ISPAN. [Google Scholar]

- Sosnowska, Joanna M., ed. 2012. Wystawa nowojorska 1939 [1939 New York World Fair]. Warszawa: ISPAN. [Google Scholar]

- Stavenow, Åke, ed. 1934. Švedų pritaikomojo meno paroda Kaune [Exhibition of the Swedish Applied Art in Kaunas], Exhibition Catalogue. Kaunas: Vytauto Didžiojo muziejus. [Google Scholar]

- Surdokaitė-Vitienė, Gabija. 2015. Susimąstęs Kristus: Nuo religinio atvaizdo iki tautos simbolio Rūpintojėlio. The Christ in Distress: From Religious Image to a National Symbol Rūpintojėlis, Exhibition Catalogue. Edited by Gabija Surdokaitė-Vitienė. Vilnius: Bažnytinio paveldo muziejus. [Google Scholar]

- Švedų liaudies meno paroda [Exhibition of the Swedish Folk Art], Exhibition Catalogue. 1934. Kaunas: Vytauto Didžiojo muziejus.

- Tymkiw, Michael. 2018. Nazi Exhibition Design and Modernism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Umbrasas, Jonas, and Eglė Kunčiuvienė. 1980. Lietuvių dailininkų organizacijos 1900–1940 m. [Organisations of Lithuanian Artists in 1900–1940]. Vilnius: Vaga. [Google Scholar]

- Utställning av Litauisk Folkkonst från Čiurlionies Galleri i Kaunas. 14 Januari–16 Februari 1931 [Exhibition of Lithuanian Folk Art from the Čiurlionis Gallery in Kaunas. January 14–February 16, 1931], Exhibition Catalogue. 1931a. Stockholm: Nordiska museet.

- Utställning av Litauisk Folkkonst från Čiurlionies Galleri i Kaunas. December 1931 [Exhibition of Lithuanian Folk Art from the Čiurlionis Gallery in Kaunas. December 1931], Exhibition Catalogue. 1931b. Malmö: Malmö Museum.

- Utstilling av Litauisk Folkekunst fra Čiurlionies Galleri i Kaunas. Mars [10]–April [10] 1931 [Exhibition of Lithuanian Folk Art from the Čiurlionis Gallery in Kaunas. March [10]–April [10], 1931], Exhibition Catalogue. 1931. Oslo: Kunstindustri museet.

- Žemaitytė, Zita. 1988. Paulius Galaunė. Vilnius: Vaga. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).