Abstract

Heta-Uma, a Japanese illustration style, was first proposed in the 1970s and flourished in the 1980s. It involves illustration that expresses a unique artistic temperament through the use of childlike and naive forms. However, such a special cultural phenomenon has not been widely explored in the literature. The aim of this article is to examine the Heta-Uma works during the 1980s and reveal the role of these works’ characteristics. We conduct a case study of the two most representative Heta-Uma illustrators: Teruhiko Yumura and Yosuke Kawamura. Specifically, we analyze a total of their 514 works using the combination of quantitative and qualitative research methods. Our key findings suggest that the number and the type of Heta-Uma works changed from the early 1980s to the end of 1980s and the text in Heta-Uma works potentially plays an important role in supporting their understanding. In addition, the study demonstrates that Heta-Uma is likely to have a relationship with Japanese aesthetics. We take a first step towards understanding Heta-Uma systematically, and believe that this article complements the knowledge gap in the context of Japanese illustrations. Meanwhile, our study opens up avenues for future work, such as investigating the birth of Heta-Uma, the relationship between the works and the social impact, and the effect of Heta-Uma on the modern Japanese illustrations.

1. Introduction

Heta-Uma is a cultural phenomenon that has played an important role in Japanese arts. In the concept of Heta-Uma, ambiguity is a fundamental aspect of its culture and aesthetics. The term Heta-Uma itself represents a distinctive culture and set of values. Heta-Uma popularity easily changes with the times, which is common within the cultural language (), The applications of Heta-Uma culture include letters, manga, and illustrations (); (). Among these applications, the most representative and broadly known expression of Heta-Uma culture is Heta-Uma illustration.

Heta-Uma illustration can be literally translated as “not skilled and immature (Heta), but actually proficient and charming (Uma)”. When one first views Heta-Uma works, they could be mistaken for the doodles of regular people. Rather than “looking immature”, it is instead a way of expressing a unique artistic temperament through the use of childlike and naive forms (). Compared with the other professional and occupational illustration techniques, Heta-Uma pays more attention to the general performance impulse of ordinary people without painting training skills. This is a distinctive feature of Japanese aesthetics, where emphasizing flaws and a sense of incompleteness is also considered a kind of beauty. Heta-Uma appears often in various books, magazines, and collections of graphic and illustration works in Japan. Meanwhile, apart from the art field, it is also widely used in the advertising field, particularly by cartoonists, illustrators, and graphic designers.

As a special cultural phenomenon in the field of illustration in Japan, Heta-Uma first appeared in the 1970s and flourished in the 1980s (); it is also one of the most emblematic cultural phenomena in the development of Japanese contemporary art. The use of “technical immaturity” as an expression form has had a significant influence on Japan’s illustration and advertising sectors. Shoji Yamafuji, a Japanese painter, was the first to propose the notion of Heta-Uma. During the 1980s, when Heta-Uma was at its peak, it swept through the whole Japanese illustration sector, spawning a slew of well-known artists, including Teruhiko Yumura, Yosuke Kawamura, Yoshikazu Ebisu, and Mizumaru Anzai, among others.

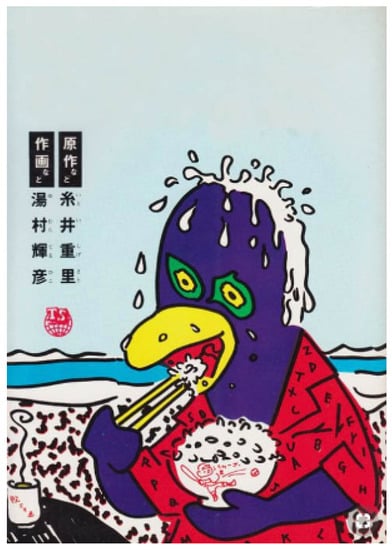

Heta-Uma was especially carried forward by two prominent illustrators: Teruhiko Yumura (Yumura) and Yosuke Kawamura (Kawamura). With their promotion, Heta-Uma has become a means of expression in the field of illustration in Japan, and has had a certain significant impact on Japanese commercial art. For example, Figure 1 shows one of the most famous Heta-Uma works by Yumura, known as ペンギンごはん (A penguin having a meal). This illustration is the cover of a grotesque caricature written by Shigesato Itoi and drawn by Yumura, which began to be serialized in Garo magazine in April 1976. Many artists have referenced it, inherited it, and used it in their own creations in contemporary times, demonstrating its liveliness. To analyze a Japanese illustration, it is of significance to understand its history, social background, and the characteristics of representative works. Recent works (); () have briefly investigated the history of Heta-Uma, randomly selecting several works of Yumura and describing their contents. Despite such attempts, Heta-Uma, as an important Japanese culture phenomenon, has not been widely studied and systematic knowledge of the characteristics of Heta-Uma works remains underdeveloped.

Figure 1.

A Heta-Uma work by Yumura: A penguin having a meal (1976).

To fill this gap, this study investigated the characteristics of Heta-Uma illustration works in the 1980s through a case study of two representative illustrators: Yumura and Kawamura. A total of 514 Heta-Uma works were collected and manually analyzed (i.e., 273 works by Yumura and 241 works by Kawamura). The main goal of this study was to systematically understand the characteristics of their 1980s works. Specifically, we investigated the following three aspects:

- (I)

- The trend between the year and the number of Heta-Uma works during the 1980s.Motivation: The 1980s was the prosperous period of development for Heta-Uma, but it is uncertain whether the works in the 1980s underwent distinct changes as a result of the early ascent, middle stage, and late stage. From this viewpoint, it is possible to provide a research perspective and a foundation for future study on Heta-Uma, in order to qualitatively investigate its potential drivers (e.g., economy, culture, and life demand).

- (II)

- Heta-Uma work type differences between Yumura and Kawamura.Motivation: A variety of Heta-Uma works have been assessed, but how the types of these works differ remains unknown. Thus, we aimed to gain an understanding of the differences between the two considered representative Heta-Uma illustrators through a comparative analysis.

- (III)

- The role of text in Heta-Uma works.Motivation: Heta-Uma works use “technical immaturity” to express their contents. We argue that this may make the audience confused, hindering understanding of their intentions underlying the Heta-Uma contents. Thus, we further explore whether text is essential in Heta-Uma works.

Now, we summarize the key findings from this study. Our results first show that, in terms of the trend between the year and the number of Heta-Uma works, the 1980s were indeed a prosperous period of development for Heta-Uma works. From the early 1980s, the number of works gradually increased, but decreased by the end of the 1980s. By studying the different kinds of Heta-Uma works of Yumura and Kawamura, it was found that most of the works of Yumura in this decade were for magazine covers, while most of the works of Kawamura in this decade were for original illustrations and covers. In particular, the scope of Yumura’s works was pretty wide, while the scope of Kawamura’s works was narrower in comparison. In terms of the relationship between hand-painted text and Heta-Uma works, we observed that 58% of Kawamura’s works included no hand-painted text. Conversely, there was no hand-painted text in 18% of the works of Yumura. The main contributions of this research are three-fold: (i) This research comprises a first step towards investigating the Heta-Uma works during the 1980s (a prosperous period for this style); (ii) a manual comparative analysis of two famous Heta-Uma illustrators is detailed; and (iii) we reveal the role of text in Heta-Uma works.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: We describe the background of Heta-Uma and the related literature in Section 2. We then introduce the materials and methods used in this study to answer the proposed research questions in Section 3. The research results are presented in Section 4, and we discuss the features of the works by the two illustrators and the relationship between Heta-Uma and platforms and Japanese aesthetics in Section 5. Finally, we conclude our study in Section 6.

2. Background and Related Work

In this section, we first introduce the background regarding the definition of Heta-Uma, and describe the two representative Heta-Uma illustrators. Then, we present the related work.

2.1. Definition of Heta-Uma

The concept of Heta-Uma was first proposed around 1970 (). Concretely, according to the illustrator Shoji Yamafuji, the definite origin of the term Heta-Uma was heard when he attended an illustration exhibition at a department store in Ginza around 1970, where he had a conversation about Heta-Uma with a senior illustrator he knew. Later, Yumura further refined the definition of Heta-Uma and injected more ideas. As discussed in his book, the definition of Heta-Uma evolved typically in this way ():

- (1)

- Heta-Uma (unskilled good).

- (2)

- Heta-Heta (skilled bad).

- (3)

- Uma-Uma (skilled good).

- (4)

- Uma-Heta (skilled bad).

More recently, Kyoichi Tsuzuki also clarified statements regarding the definition of Heta-Uma in an interview in the fifth episode of “The History of Postwar Japanese Subculture II” (“What is hetauma”), which aired on NHK on 30 October 2015. In this context, the details were as follows ():

- Uma-Uma (works that are highly skilled and attractive).

- Uma-Heta (works that are highly skilled but not attractive).

- Heta-Uma (works that are not highly skilled but very attractive).

- Heta-Heta (works that are neither highly skilled nor attractive).

2.2. Representative Illustrators: Yumura and Kawamura

Yumura (1 November 1942–) is an illustrator and graphic designer. His main pen name is Terry Johnson, but he also goes by other pen names, including FLAMINGO TERRY, FRAMINA TERRENO GONZO, TERRINO FLAMINI’ GONZAREZ, and so on. In the 1970s, illustration works by Yumura became gradually popular among youth magazines and other publications. In 1970, he joined Nobuhiko Yabuki and Kawamura, and founded “100% studio”. Meanwhile, the original “flamingo studio” was founded in 1974. Yumura grew up in the center of Shinjuku, Japan, a place where the people were able to buy the latest music and manga of that time. In addition, his father, the owner of Meiji House, had been immersed in the world of Kabuki from a young age and was a lover of popular music (). Thus, musical elements deeply influenced Yumura’s style.

Kawamura (28 April 1944–4 June 2019) was a Japanese designer, artist, and music critic who started drawing under the name of “100% studio” in 1970, alongside Yumura and Nobuhiko Yabuki. Inheriting Yumura’s Heta-Uma technique, Kawamura’s illustrations tend to emphasize the unique personality and musicality of each person. Through his skillful drawing techniques, he deformed characters to express them uniquely in his own way; in other words, Kawamura developed his unique Heta-Uma style through a unique “morphing” expression technique.

2.3. Related Work

To cover all potentially related literature, we conducted a comprehensive search using CiNii Article, Google Scholar, IEEE/IET EL, SSRN (eLibrary Database Search Results), and the National Diet Library of Japan, among others. We used a keyword list consisting of “Heta-Uma”, “illustration”, “1980s illustration”, “Yumura Teruhiko”, and “Yosuke Kawamura”, in order to search through the related literature. Finally, we were only able to retrieve two research papers and one book that satisfied our keywords and met the scope of this study; one was from Japan and the other two were from Western countries. Most of the retrieved candidates were from magazines or interviews, which were not considered academic enough to be analyzed. Notably, there has been no research work investigating Heta-Uma illustration works during the 1980s. Below, we discuss the two related research papers.

Within Japan, () published a article entitled “About the Heta-Uma in Japanese Illustrations” in 2018. In this work, Onishi investigated the characteristics of several Heta-Uma works by Yumura. The study also claimed that the 1980s were a period in which the Heta-Uma works were largely released. They analyzed the Heta-Uma works from the aspect of the number of humans appearing in the contents. Outside Japan, in 2016, Dejasse Erwin published a article entitled “Heta-Uma: manga on the other side of the mirror” (). The study started from the view of a foreigner and raised confusion with regard to the word “Heta-Uma”. The author proposed his own definition, based on his understanding. At the same time, the author introduced Yumura with the representative magazine called Garo in 1970. The author assumed that the Heta-Uma illustrators are a group of artists full of rebellious spirit, similar to punk artists. In the book “Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga” by (), the author discussed the evolution of the Manga over the last decade and the associated visual culture across the world. Importantly, one chapter addressed the significance of the works of Yumura and regarded the proposal of Heta-Uma as a revolutionary movement that enriched the Manga area and also changed the field of commercial illustration. The author commented that, if an artist focuses too much on their painting skills, their work is likely to lose its activeness. The author recognized that the philosophy of art by Yumura is to avoid perfect painting, instead sustaining the doodle-like soul.

3. Materials and Methods

In this section, we present the studied materials, following which we present the methods used to answer our proposed research questions.

3.1. Materials

The study materials for this study were mostly centered on the works of Yumura and Kawamura, two representative creators of Heta-Uma works. We selected these two Heta-Uma illustrators by rigorously leveraging a systematic approach. First, we did a large-scale search to retrieve those potential candidates of Heta-Uma illustrators from online and books, resulting in a list of modern illustrators including Teruhiko Yumura, Yosuke Kawamura, Kazuhiro Watanabe, Shigesato Itoi, Yoshikazu Ebisu, Kei Nemoto, Kotobuki Shiriagari, and Sadao Shoji. Then, we conducted a round-table discussion with an experienced Japanese professor (Takayuki Terakado) from Kobe Design University who is an expert in the context of Japanese illustration. At the end, two illustrators survived (i.e., Yumura and Kawamura) since these two illustrators are very well-known and importantly they claimed that they were Heta-Uma illustrators in the public while the other candidates did not claim this. As we focused on works that were created in the 1980s, we manually collected the works that were created between 1980 and 1989 from these three books (); (); (). Note that we excluded those Heta-Uma works used in comic books and picture books, as our scope was limited to illustration only. Finally, a total of 273 works by Yumura and 241 works by Kawamura were manually examined.

During the data collection process, two threats to validity may exist. The first threat is with regard to the external validity (the ability to generalize based on our results). In our study, we only investigated two representative Heta-Uma illustrators, Yumura and Kawamura. Other Heta-Uma illustrators may have also significantly contributed to Heta-Uma in the 1980s. However, we are confident that the two selected Heta-Uma illustrators are representative enough to be studied. Other artists whose work seems to be Heta-Uma, from viewing experiences, include Mizumaru Anzai and Katsuhiko Hibino; however, these artists never actually publicly claimed their style to be Heta-Uma and, thus, their inclusion may have introduced false positives into our study. The second threat is related to the data completeness; in particular, relating to Yumura and Kawamura’s works (construct validity). We mostly relied on three books to collect their Heta-Uma works during the 1980s; however, we believe that the collected works (i.e., 273 works by Yumura and 241 works by Kawamura) were sufficient to provide insights for the understanding of representative Heta-Uma works.

3.2. Research Methods

In this research, we applied a mixed approach (quantitative and qualitative analysis) to analyze the characteristics of the Heta-Uma works of Yumura and Kawamura. Below, we describe the research methods used to address each aspect.

(I) The trend between the year and Heta-Uma works during the 1980s. Regarding the trend between the year and the number of works, we determined the year in which each work was created using the notation provided in the books, and manually sorted the number of Heta-Uma works for each year using a card sorting approach, as leveraging card sorting reduces the possibility of missing data. To visually analyze the results, we drew a bar chart to show the trend of Heta-Uma works in the 1980s.

(II) Heta-Uma types of Yumura and Kawamura. To classify the Heta-Uma work types—that is, where the works were used—we manually labeled each work type, based on the notation provided in the selected books. To analyze the work type distribution, a bar chart was drawn to display the different Heta-Uma types between Yumura and Kawamura.

(III) The role of text in Heta-Uma works. To investigate the usage of text in Heta-Uma works, we targeted two aspects: (i) The language of the text (i.e., Japanese or other foreign languages), and (ii) whether the text was hand-drawn or printed. For this purpose, we manually inspected a total of 514 Heta-Uma works and labeled these two aspects. Pie charts were drawn to present the extent to which the Heta-Uma works contained text.

4. Research Results

In this section, we present the results obtained in the following three aspects: (I) The trend of Heta-Uma works during the 1980s, (II) differences between the two representative artists (Yumura and Kawamura), and (III) the role of text in Heta-Uma works.

4.1. The Trend of Heta-Uma Works during the 1980s

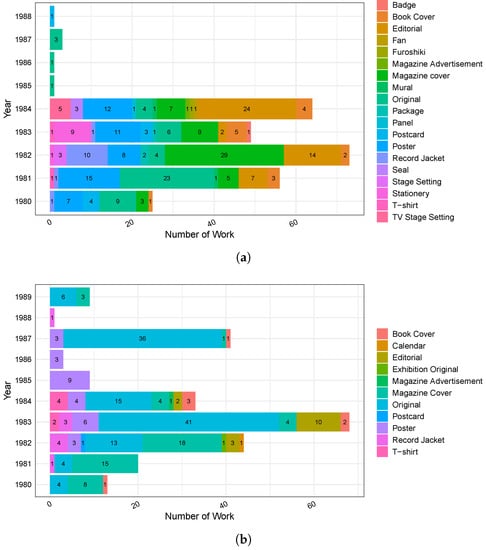

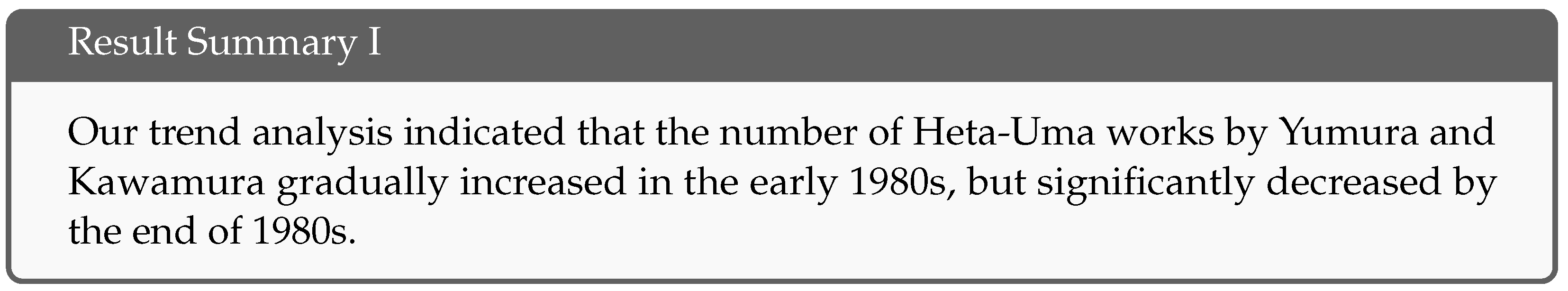

The number of Heta-Uma works increased through the early 1980s, while a relative decrease was observed by the end of the 1980s. Figure 2 depicts the trend between the year and the Heta-Uma works of Yumura and Kawamura during the 1980s. First, we observed that a large number of Heta-Uma works were produced by both of the representative artists. For instance, 273 works were produced by Yumura and 241 works were produced by Kawamura. These empirical results suggest that the 1980s would be a golden era for Heta-Uma.

Figure 2.

The trend between the year and Heta-Uma works during the 1980s. (a) The work distribution of Yumura in the 1980s. (b) The work distribution of Kawamura in the 1980s.

Second, taking a closer look at the years, as shown in the figure, we found that the Heta-Uma works of the two representative artists presented a similar trend. In detail, the number of works by Yumura and Kawamura gradually increased in the early 1980s; however, the number of their works relatively decreased afterwards, dropping to less than 10 per year by the end of 1980s. For example, as shown in Figure 2a, the number of works by Yumura was on the rise from 1980 to 1982 and reached a peak in 1982 (i.e., 73 works). From 1985, the number of works by Yumura showed a significant drop (i.e., one work, one work, three works, and one work for 1985, 1986, 1987, and 1988, respectively). Similarly, as shown in Figure 2b, the bar plot shows that the production of Kawamura’s works gradually increased in the early 1980s and reached a peak in 1983, with 68 works being produced in this year. Then, from 1984, the figure indicates a decline in the number of works by Kawamura. Although 41 works were produced in 1987, the overall trend presented a relative decrease, when compared to the early times. The second observation above opens a future avenue towards understanding the relationship between the year and the production of Heta-Uma works. We assume that such a trend may have been affected by the economy and social culture of Japan during 1980s. One potential reason is that, at the end of 1980s, Japan slowly suffered from the effect of the bubble economy, which may have had an impact on the significant decrease in Heta-Uma works.

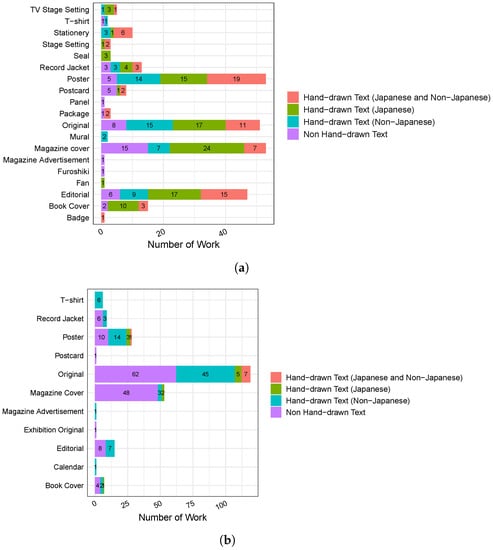

4.2. Difference in Heta-Uma Work Types between Yumura and Kawamura

Different Heta-Uma artists tend to have different types of work. Figure 2 shows the results for the manually labeled work types, with respect to the works of Yumura and Kawamura. First, we observed that the variety of works by Yumura was larger than that for those by Kawamura. For instance, there were a total of 19 work types (i.e., badge, book cover, editorial, fan, furoshiki, magazine advertisement, magazine cover, mural, original, package, panel, postcard, poster, record jacket, seal, stage setting, stationery, T-shirt, and TV stage setting) observed in Yumura’s works, making it a highly diverse collection. On the other hand, Kawamura’s works were divided into only 11 categories (i.e., book cover, calendar, editorial, exhibition original, magazine advertisement, magazine cover, original, postcard, poster, record jacket, and T-shirt).

Second, our manual classification indicated that the two representative Heta-Uma artists had their own dominant production types. The most prolific works by Yumura during the 1980s were mainly produced for magazine covers and posters. He drew many magazine covers, for magazines such as Garo, Bikkuri House, WET, and Takarajima. After 1987, his work on Garo covers decreased significantly, as Shinbo Minami’s works replaced the full-year Garo covers in 1988 and 1989. Between 1980 and 1984, Yumura was very active and created various types of Heta-Uma works; after 1985, the genres produced dwindled, concentrating mainly on original illustrations. Original illustration was the most common work type for Kawamura during the 1980s. This is due to his participation in several exhibits and the creation of numerous series, such as the “JUNGLE FEVER” series of illustrations in 1987 and the celebrity portrait series of illustrations in 1983. In 1989, as a music aficionado, Kawamura was one of the founders of the music magazine known as “Bad News”, for which he was responsible for the graphics and designs. Kawamura previously created a number of original illustrations, consisting of personal portraits of singers as well as his favorite Latin music. In the early 1980s, in addition to original illustrations, one of his primary genres of work was magazine covers, and he was responsible for the covers and illustrations of “MUSIC MAGAZINE”.

4.3. Text in Heta-Uma Works

Many Heta-Uma llustrations were originally designed to be accompanied by text. Illustrations have the meaning of “explanation”, and appear as a complement to the text; for example, in the relationship between the illustration and the title on the cover of a novel or the like, the illustration is what provides a sense of atmosphere to the novel. In the case of Heta-Uma works, the illustrations look very interesting; however, as the illustrator has deliberately used a distorted and childish approach in their creation, people may not understand the meaning of Heta-Uma works very well. Considering this, the text may play an important role in supplementing an understanding of the illustration.

In particular, the text in the illustration can be divided into two types: Hand-drawn text and printed text. Hand-drawn text refers to the text that is complementary to the image vision in the process of creating the illustration, and can be considered part of the illustration content. Meanwhile, printed text denotes text that is added later during the printing progress in a commercial activity, such as a preview of magazine content or an advertisement on a poster. As the illustration itself plays the function of a textual description, the text occupies a very significant place in the illustration.

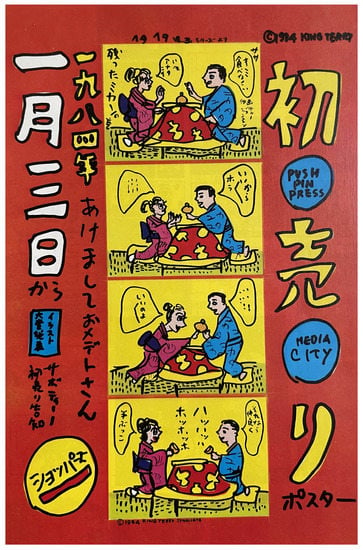

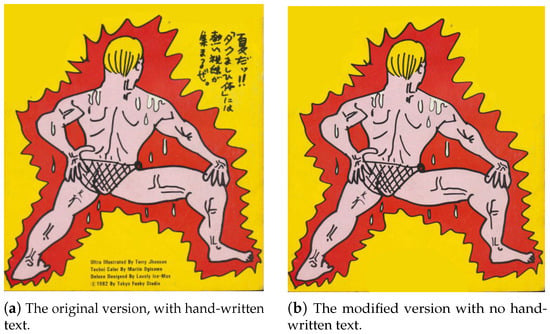

We illustrate two examples from the studied Heta-Uma works, in order to demonstrate the role of the text in understanding these works. Figure 3 shows a poster work by Yumura, which was used in a shopping mall for promotion. As can be observed in the figure, many Japanese characters are hand-drawn in this work, with the topic, time, and location of the event all drawn by hand, making it apparent what the poster is attempting to express at a glance. Without this text, the customers may not understand the goal of the childish illustration. To further address the significance of the text in Heta-Uma works, we show a comparative example. Figure 4a shows a work originally by Yumura with hand-drawn text, while Figure 4b shows a edited version, in which the hand-drawn text has been removed. In Figure 4a, the following text is written: “夏だ!!「タクましひ体」には熱い視線が集まるぜ。” (translated to English: “It’s summer!! A hot gaze is drawn to a “tough body”.”). The reader may instantly comprehend the meaning of the artwork if they read the text; however, when the work is presented without this text, the reader may not fully understand what information is expressed, and could simply think the man in the figure is too hot and, thus, sweats a lot.

Figure 3.

A poster work by Yumura for a shopping mall in Fukuoka, Japan (1984).

Figure 4.

A Heta-Uma work by Yumura (1982): (a) The original work; and (b) The modified version, where the hand-written text (“It’s summer!! A hot gaze is drawn to a “tough body”.”) was removed by the author.

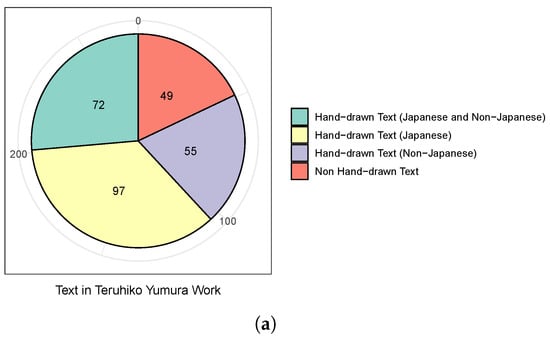

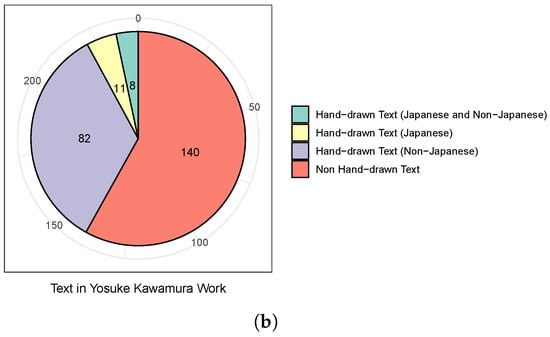

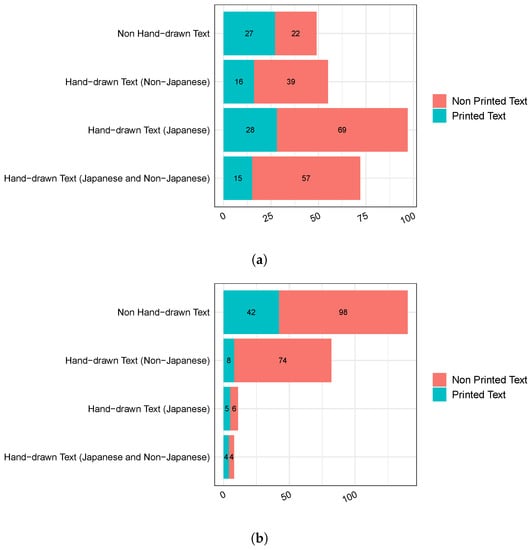

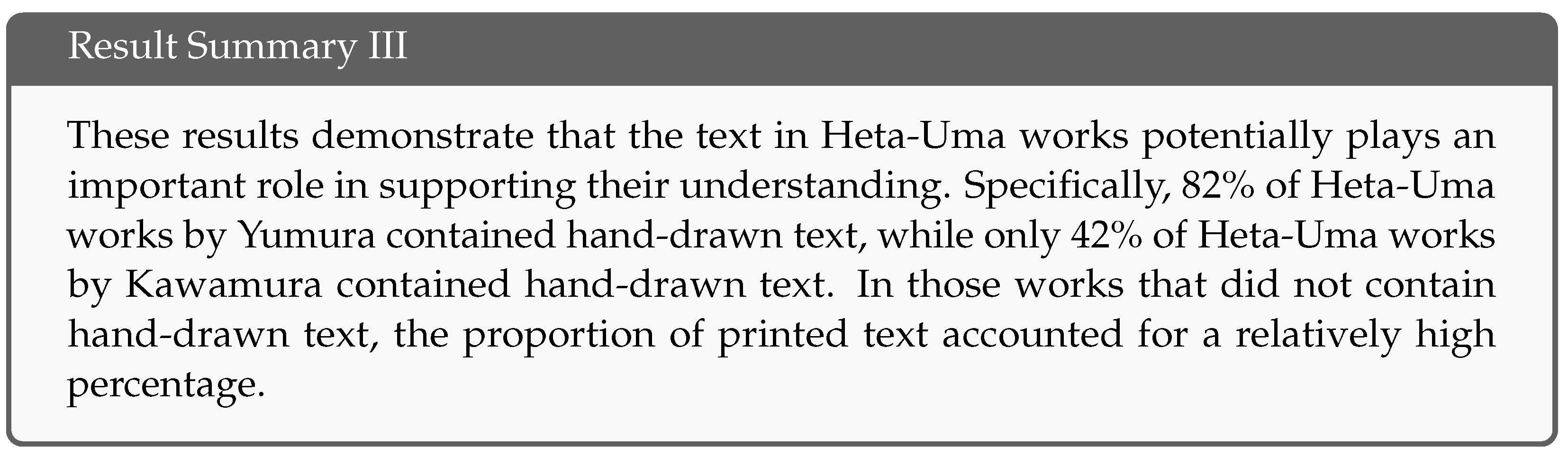

It was found that 82% of Heta-Uma works by Yumura contained hand-drawn text, while 42% of Heta-Uma works by Kawamura did not contain hand-drawn text. Figure 5 shows the proportion of Heta-Uma works that contain hand-drawn text, while Figure 6 presents the distribution of different Heta-Uma work types that contain hand-drawn text. Figure 7 shows the proportion of printed text and non-printed text among the works. Four kinds of works were classified, based on hand-drawn text and its language: Hand-drawn Text (Japanese and Non-Japanese), Hand-drawn text (Japanese), hand-drawn text (non-Japanese), and no hand-drawn text. Hand-drawn text (Japanese and non-Japanese) refers to the case where the text is written in both Japanese and other foreign languages (e.g., English). Hand-drawn text (Japanese) denotes when the text is only written in Japanese. Hand-drawn text (non-Japanese) refers to the case where the text is not written in Japanese (e.g., in English). Now, we discuss the related results, with respect to the works of Yumura and Kawamura, below.

Figure 5.

The proportion of Heta-Uma works that contain hand-drawn text. (a) The proportion of Yumura works containing hand-drawn text. (b) The proportion of Kawamura works containing hand-drawn text.

Figure 6.

The distribution of different Heta-Uma works containing hand-drawn text. (a) The distribution of Yumura works containing text. (b) The distribution of Kawamura works containing text.

Figure 7.

The proportion of Heta-Uma works that contain printed text. (a) The proportion of Yumura works that contain printed text. (b) The proportion of Kawamura works that contain printed text.

In terms of Yumura, as shown in Figure 5a, our manual classification results demonstrated that 82% of his works (72 + 56 + 97 = 225 out of 273 works) contained hand-drawn text. In addition, we observed that there was a high proportion of English words appearing in works by Yumura with text, with 43% being classified as such (72 + 25 = 97 out of 225 works). This result indicates that Yumura often used English words in his works. One potential reason for this is that, during the 1980s, Japan was widely influenced by Western cultures. Upon closely looking at the kinds of works, as detailed in Figure 6a, we observed that poster, original, and editorial works were likely to contain hand-drawn text. Furthermore, we found that, among these work types, the proportion of non-Japanese text was relatively similar to that of those containing only Japanese. Regarding printed text, the results in Figure 7a show that the works of Yumura without hand-drawn text were slightly more likely to use printed text (i.e., accounting for 55%).

In terms of Kawamura, as shown in Figure 5b, we found that less than half (42%) of his Heta-Uma works included hand-written text. Interestingly, the results demonstrated that almost 90% of his works that contained text involved non-Japanese words, which was even higher than that in the works of Yumura. We imply that this technique may have been affect by the pioneer (Yumura). Figure 6b shows that original works tended not to contain hand-drawn text, when taking the frequent work kinds into account. Such a difference could have been the result of the different aims of these two Heta-Uma illustrators. For instance, the works by Yumura were mainly intended to meet commercial illustration purposes, while the works of Kawamura were intended to reflect personality. Figure 7b shows the proportion of Kawamura works that contain printed text. As can be observed from the figure, in the works that did not contain hand-drawn text, around 30% of them contained printed text. In general, when compared to the works by Kawamura, printed text did not frequently appear in the works of Kawamura.

5. Discussion

In this section, we illustrate several Heta-Uma works by Yumura and Kawamura, and discuss their features.

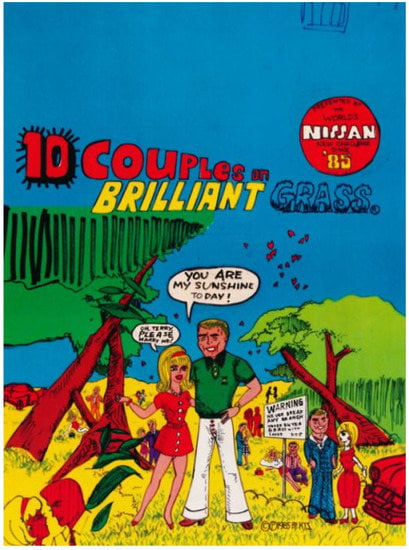

5.1. Features of Yumura’s Heta-Uma Work

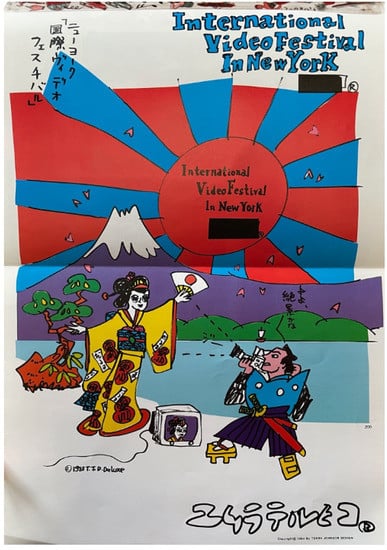

The work of Yumura is characterized by its “pomposity”. Many of the images in his works depict scenarios in which white Westerners speak foreign languages; as a result, he has been accused of being “more American than Americans”. One example is shown in Figure 8, which shows a poster designed for Nissan. This particular aesthetic is largely due to the fact that Yumura grew up at a time when the Japanese fascination with Americans was at its peak. Yumura was not interested in some refined cultures, but instead was inspired by the layout and visual design of some of the cheesy American magazines and comic books of the 1970s. For instance, in an interview for the book “Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga”, Yumura stated: “I had a strong, romantic image of the U.S. before actually going there, but seeing the real thing sort of destroys the dream. People often think I’ve lived a long time in the U.S., but if you live there the influence is diluted. When I do go, I want to notice interesting things” (). Yumura is also a lover of soul music, and claims to own nearly 400 records. In his Heta-Uma work, he incorporated typical American packaging and advertising concepts. Yumura prefers to work in English, as he believes that English is a highly sensible language. In the 1980s, he also created posters for a number of major international business events, injecting the Heta-Uma style into these posters. Yumura’s work encompasses not only European and American elements, but also Japanese elements. For example, in another poster shown in Figure 9, which was used for the International Video Festival in New York, distinctly Japanese elements can be observed: Kimonos, Mount Fuji, and a Japanese samurai.

Figure 8.

A work by Yumura showing Westerners (1986, Nissan Poster).

Figure 9.

A work by Yumura showing Japanese elements (1983, International Video Festival In New York Poster).

5.2. Features of Kawamura’s Heta-Uma Work

When discussing the Heta-Uma work of Kawamura, it is impossible not to refer to “salsa music”. Kawamura has studied “salsa music” deeply, and has written many musical reviews about salsa music. Salsa music is one of the sub-genres of Latin music, which spread rapidly from New York to the rest of Latin America in the early 1970s. Salsa music is contemporary and has a colorful and imaginative quality that clearly differs from other music. Kawamura was fascinated by this lively music. Inspired by this, his works widely reflect the optimistic spirit of salsa music. He attempted to produce a feeling that is as similar as possible to a photograph, but not similar to it, when making his compositions.

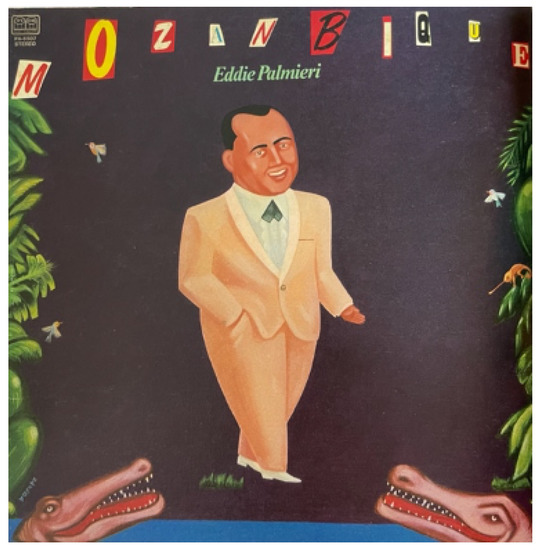

Kawamura’s work was highly associated with record covers since 1975, as he illustrated a variety of covers for records. For example, Figure 10 presents a work by him, which was used for a MOZAMBIQUE record in 1975. In 1971, Yumura and Kawamura cooperated to paint the front and back of Takada Wataru’s (1949–2005) album cover. They shared a similar painting style, and seemed to be in perfect harmony. The album cover has a mix of pictures on the front and back: An American and a cucumber, and a Japanese and a banana. This represents the communication between and integration of the East and West. Yumura and Kawamura developed a unique starting point to study American popular culture from the early 1970s. To capture a sharper impression of the current youth, Kawamura deliberately toned down his painting talents and appeared to be naive. Over time, several common agreements between Yumura and Kawamura affected each other, with respect to their Heta-Uma works.

Figure 10.

A work by Kawamura, created for a record (1975, MOZAMBIQUE).

5.3. Relationship between Hetauma and Platform

The empirical results obtained in RQ2 indicate that there could be a relationship between Heta-Uma illustrations and the platforms on which they are presented. Hence, we here provide an in-depth discussion around this relationship using Yumura and Kawamura as cases. Generally, illustrations themselves are commonly designed for usage on specific platforms (e.g., magazines, exhibitions, posters, packaging, etc.). Hence, the illustrator needs to consider the purpose and the scenario of designing an illustration, in order to best show their value and meet audiences’ needs.

In Heta-Uma, as one style of illustration, a portion of works are created for commercial purposes, such as designing covers for magazines, making posters, and drawing illustrations for publications.

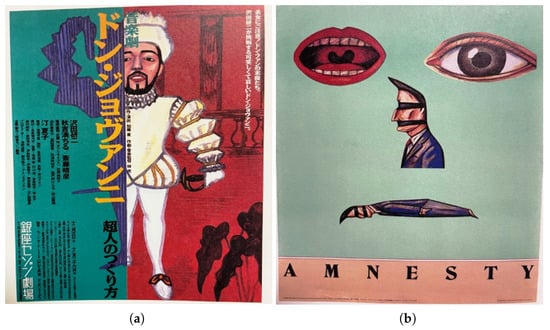

In this sense, commercial illustrations must conform to specific specifications, styles, and design requirements to ensure that they are consistent with the products or services they represent, and attract potential consumers. At the same time, there are many original illustration works, which are usually created by illustrators to showcase their creativity, and these works may be exhibited or displayed in galleries. Different from the feature of commercial ones, original illustrations widely do not have specific purposes or requirements and are created and presented based on the illustrator’s own decisions. For example, as shown in Figure 11a, the poster “Don Giovanni” drawn by Kawamura is aligned with the contents of the musical, with the aim to attract those audiences who are interested in the target music. As we can see, the character in the figure is wearing ballet-related clothes. In terms of his original works, they are more likely to have a relatively abstract and difficult-to-understand image, such as “AMNESTY”, as shown in Figure 11b. With regard to Yumura’s works, from Figure 2a, we observe that the type of magazine cover accounts for a relatively high proportion. Especially, in 1982, the number of Heta-Uma artworks reaches almost 29. One of the magazines that Yumura frequently contributed to is called Garo. Garo is a monthly comic magazine published by Seirindo, which was in publication from 1964 until around 2002. We then manually did an in-depth analysis to explore the characteristic difference between Garo illustration works and Yumura’s original illustration works based on the collected dataset, from various perspectives (i.e., colors, number of characters, and with a scenario or not). From the color perspective, we find that Garo illustration works are more likely to be colorful than original illustration works (93% against 59%). From the character perspective, we observe that Garo illustration works tend to depict a single character (60%) but original illustration works tend to describe multiple characters (80%). From the scenario perspective, we find that compared to original ones, Garo illustration works are less likely to introduce the scenario, only accounting for 7% of the classified instances. Based on our exploratory discussions, another actionable future work is to systematically establish a relation map between the characteristics of Heta-Uma works and platforms by leveraging a more fine-grained qualitative analysis.

Figure 11.

A comparison of Heta-Uma illustration works by Kawamura between commercial works and original ones. (a) Commercial work “Don Giovanni”. (b) Original work “AMNESTY”.

5.4. Relationship between Hetauma and Japanese Aesthetics

To gain a better understanding of the theory of Heta-Uma illustration, we now further discuss the relationship between Heta-Uma and Japanese aesthetics, as we speculate that the emergence of Heta-Uma is related to such aesthetics. According to Taro Okamoto’s proposal of “Three Principles of Today’s Art” (, pp. 4–5), art should not (1) be beautiful, (2) be skillful, and (3) be comfortable. Moreover, he claimed, “The true art of the future, the art that will be recognized by the world, is something that is clumsy, dirty, and uncomfortable”. Additionally, Okamoto’s proposal is along the same line as the concept of Heta-Uma, and both of them share a common aesthetic philosophy that is beyond traditional aesthetic standards. On the one hand, Okamoto’s proposal advocates for exploring the possibilities of new expressions that are unconstrained by the traditional emphasis on the “beauty” and “skillfulness” of art. On the other hand, the aesthetic philosophy of Heta-Uma illustrations is to address the values of imperfect expressions, as well as the personality and sensibility of the artist, rather than the pursuit of perfection. Inspired by the aesthetic philosophy of Heta-Uma, Okamoto incorporated it into his own works and showed a high appreciation. Hence, Okamoto’s works generally are not technically perfect, but they have distinctive textures and expressive methods that possess the Heta-Uma charm. To summarize, Heta-Uma illustrations are free from traditional aesthetic standards and instead are better at emphasizing the personality and originality of artists.

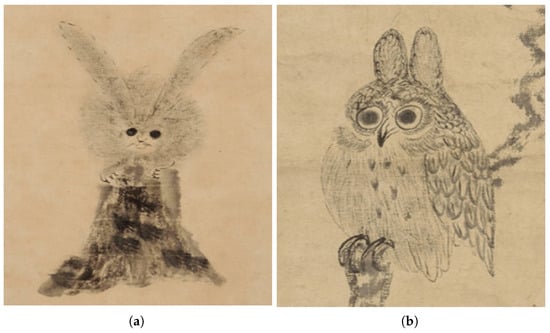

Furthermore, the prior literature () suggested that Heta-Uma illustrations could have a connection with Japanese art from the Edo period (also known as the Tokugawa period between 1603 and 1867, the final period of traditional Japan). Although artworks produced in the Edo period contained a number of impressive sculptures, they also had an appealing aspect of imperfection that can be considered Heta-Uma. The idea of imperfect forms and incomprehensible tastes is likely to be originated from Japan’s unique aesthetic consciousness, as observed in Zen paintings (most closely associated with Zen Buddhism), Haiga (a style of Japanese painting that incorporates the aesthetics of haikai), and Nanga paintings (the painting of the Southern school in China). Meanwhile, those imperfect paintings created by Hakuin Ekaku (one of the most influential figures in Japanese Zen Buddhism) and Sengai Gibon (a representative Japanese monk of the Rinzai school) are also regarded as expressions of Heta-Uma. It is said that these works can further encourage audiences to think about the judgment of their charm. We now elect two artworks from the Edo period to illustrate how Heta-Uma appears to be influenced by traditional aesthetic consciousness. Representative examples include the “Rabbit Drawing” and “Owl Drawing” drawn by Iemitsu Tokugawa, as shown in Figure 12. These two drawings commonly have a loose style that is not broadly observed in traditional Japanese art, but they are undeniably charming and endearing to modern sensibilities. The Southern School of literati painting during the Edo period frequently employed simple expression techniques. While the produced paintings may not be visually stunning, they possess a unique charm and express strong emotions. Since there is no academic research that proves the inherent relationship between Heta-Uma and the artworks from the Edo period, the next logical future direction for researchers is to explore whether or not the causality indeed exists.

Figure 12.

Two artworks by Iemitsu Tokugawa from Edo period. (a) Rabbit Drawing. (b) Owl Drawing.

6. Conclusions

Heta-Uma, a particular cultural phenomenon in the field of illustration in Japan, was first proposed in the 1970s and flourished in the 1980s. However, this phenomenon has not been widely studied in the literature, and a relevant knowledge gap exists. To complement this gap, in this study, we conducted a case study on two representative Heta-Uma illustrators—Yumura and Kawamura—in order to investigate the characteristics of Heta-Uma works during the 1980s. Our main results demonstrated that (I) the number of Heta-Uma works by Yumura and Kawamura gradually increased in the early 1980s, but presented a significant decrease by the end of 1980s; (II) Yumura and Kawamura tended to have different Heta-Uma work types; and (III) the text in Heta-Uma works potentially plays an important role in supporting their understanding.

This study provides a first step towards understanding the characteristics of Heta-Uma works systematically from quantitative and qualitative viewpoints, as well as opening up several future promising avenues for research, including further qualitative studies (involving, e.g., interviews or surveys) to investigate the reasons why the number of works tended to decrease, as well as extending the existing framework to analyze other Heta-Uma illustrators.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

We provide our data available via https://shorturl.at/ckmU0 (accessed on 29 April 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

References

- ACROSS Henshushitsu. 1994. Hetauma Sedai. Tokyo: PARCO Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Dejasse, Erwin. 2016. Heta-Uma: Manga on the Other Side of the Mirror. Liége: University of Liége. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchu Art Museum. 2019. Heso Magari: Japanese Art from Zen Paintings to Heta-uma. Tokyo: Kodansha Ltd., p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jima, Oda. 2009. 1980’s Pop Illustration. Sevenoaks: Aspect Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, Kawahara. 1971. New Illustration Imagination and Technology and Professional Secrets. Tokyo: David sya. [Google Scholar]

- NHK. 2015. What Is Heta-Uma? Available online: https://www.nhk.or.jp/subculture/02/lecture05.html (accessed on 29 April 2023).

- Schodt, Frederik L. 2013. Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, pp. 140–44. [Google Scholar]

- Shoji, Yamafuji. 2013. Hetauma Bunkaron. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, pp. 4–5, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Tadashi, Fujita. 2012. dennsetsu no irasutore-ta Yosuke Kawamura no shinnjitsu. Tokyo: p-vine Books. [Google Scholar]

- Teruhiko, Yumura. 1981. Teruhiko Yumura HIT PARADE. Tokyo: Bijiutsu Press, p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- Yo, Onishi. 2018. About the “Heta-Uma” in Japanese Illustrations. J. Hokkaido Univ. Educ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 69: 140–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yousuke, Kawamura, and Yumura Teruhiko. 1984. nippon no e. Yousuke Kawamura vs. Teruhiko Yumura. Tokyo: Shogakukan. [Google Scholar]

- Yukiko, Tanaka. 2019. Artscape Artwords 1.0. Available online: https://artscape.jp/artword/index.php/ (accessed on 29 April 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).