Abstract

This essay examines how Black girl narratives are finding and making space and place in the arena of comic books and television. With the rise in Black girl (super)hero protagonists on the comic book pages and adapted television shows, it is essential to explore the significance of their rising inclusion, visibility, and popularity and understand how they contribute to the discourse surrounding the next generation of heroes. Guided by an Afrofuturist, Black feminist, and intersectional framework, I discuss the progressive possibilities of popular media culture in depicting Black girlhood and adolescence. In Marvel Comics’ “RiRi Williams/Ironheart”, DC Comics’ “Naomi McDuffie”, and Boom! Studios’ “Eve”, these possibilities are evident. Blending aspects of adventure, fantasy, sci-fi, and STEM, each character offers fictional insight into the lived experiences of Black girl youth from historical, aesthetic, and expressive perspectives. Moreover, as talented and adventurous characters, their storylines, whether on the comic book pages or the television screen, reveal a necessary change to the landscape of popular media culture.

1. Why Black Girls?

In the winter of 2020, The Black Scholar featured a Special Issue on “Black Girlhood” (Lewis 2020, pp. 1–3) that shined a light on the significance, challenges, and beauty of Black girls. This Special Issue covered an array of topics that include analyzing representations of Black girls in the 2020s protest movement, musical theater, literature, Black girlhood personified in digital communities and new media technologies, Black girls in the Marvel Universe, as well as testimonials of Black girls sharing their own girlhood experiences. As a collection of articles, testimonials, and book reviews, “Black Girlhood” builds on the established work of literary writers, playwrights, and scholars such as Ruth Nicole Brown, Toni Cade Bambara, Nazera Sadiq Wright, Kristen Childs, Bettina Love, LaKisha Simmons, Venus Evans-Winters, and Monique W. Morris. Tapping into the literary and political authority of these authors, the issue at the same time answers the question why Black girls matter and offers another platform for Black girls to be seen and heard. Additionally, this issue delivers several interdisciplinary conversations around the intersectionality of Black girls, incorporates a global focus, and serves as a motivation for this article.

Black girlhood has a very layered and complex past. Whether we are talking about the recorded experiences of enslaved Black girls,1 about centering Black child/girlhood in photographic form,2 the 1940s Kenneth and Mamie Clark doll studies, the threat of loss of black girls’ life and innocence in the 1960s, or the report “Girlhood Interrupted: The Erasure of Black Girls’ Childhood” (Epstein et al. 2017) produced by the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality, Black girlhood remains a heavily discussed topic. For more than 20 years, multi-disciplinary scholars of Black girlhood have identified the ways in which these girls have been disproportionately represented (based on race and gender), their marginalized status, educational inequity, the violence directed towards them, and recently the ways in which they embody traits of #BlackGirlMagic, joy, and empowerment. However, while there are discussions of Black girlhood experiences within the academy and the larger landscape of popular culture, what is not discussed in great detail is the specific way in which comic book storytelling contributes to the Black girlhood narrative. Thus, the question is further expanded to why Black girls in comics?

In this article, I seek to see Black girls as a whole through the lens of three fictionalized comic book characters, Marvel Comics’ RiRi Williams (“Ironheart”), DC Comics’ Naomi McDuffie, and Boom! Studios’ Eve. Bridging my wide interest in Blackness and popular culture with my personal and professional passion for comic books, I aim to respond to the call for a critical analysis of Black girlhood while establishing more lanes of inquiry. A larger set of thoughts that I want to explore is the dynamics of Blackness in comics, particularly Black girlhood, and what is necessary for it to have more academic representation. Additionally, it is necessary to explore these characters’ existence and representation in popular culture (particularly around defining and maintaining popularity in the sense of being widely read, bought by many, maintaining a regular viewership, and generating ongoing online discussions), while achieving change in people’s conceptions of these characters. When thinking about Black girlhood, I do not see it as experiences defined by one meaning but as an illustration of a variety of emotions, experiences, and personalities. There is a constant push–pull and complex relationship that Black girls have with society, media, and their own identity formation. Historically, Black girl characters have been repeatedly neglected, adultified, and written as one-dimensional compared to their male and white counterparts (Edwards 2016). This is especially visible in the comic book narrative. Moreover, their growing existence in comic book narratives is a success considering they were not common characters.

As a Black woman who was once a Black girl, I see this article as part of an ongoing investment in the futures of Black girls and teens. Furthermore, as a Black female scholar in Africana Studies who is both a researcher and fan of comic books, I view this article as an academic social experiment of cross-disciplinary collaboration (Africana Studies, Black girlhood Studies, and comic books studies). I fully take up the responsibility, personal passion, and sense of urgency to recognize the need for Black girls to have a voice (whether fictional or reality) and to be normalized within the popular comic book narrative. Moreover, engaging in the narratives of RiRi, Naomi, and Eve provides an innovative opportunity to create new ways of understanding how Black girls question the status quo and create change where their voices have been systematically excluded. With the work that I do as a teacher and researcher, my personal and professional passion involves creating curriculum and spaces that offer healing, transformation, critical thinking, and problem-solving. It is essential that not only scholars conduct the research, but that students, particularly Black girls, see themselves in the literature and popular culture so that they can achieve a multitude of Black girls’ perspectives. Additionally, it is just as important that these comics find a space outside the classroom as they have the potential to appeal to a mass of new and seasoned readers and fans from all ages, genders, nationalities, and backgrounds. The works in question tell stories in a conventional, serialized format while also highlighting different types of Blackness, working towards some level of commercial success and popular recognition.

My argument in this article is guided by a triple-point of view framework of intersectionality (Crenshaw 1991), Black feminism (Collins 2000), and Afrofuturism (LaFleur 2011; Womack 2013). I try to shed light on gender, race, class, and the imagined futures of Black girls simultaneously, via popular culture and the comic book medium, in order to highlight Black girl experiences. Each of these frameworks offers an opportunity for Black girl superhero characters to become an integral part of the comic book narrative, which has been traditionally owned by adult white men. Bridging these frameworks also creates conversations past and future between Black feminism, Afrofuturism, Girlhood studies, and comic book studies. These lines of intellectual inquiry can also create possibilities for establishing a space to interrogate and move beyond academic borders. As Paula Giddings argues, Black feminist narratives seek to address past and present oppressions, stereotypes, and controlling images to be subverted and corrected so that new forms of activism can emerge to tell the stories of Black women and girls (Giddings 1984). Thus, when an Afrofuturist framework is added, an examination of belonging, healing from oppression, re-writing past and present scripts, and taking hold of the future particularly in this case of the Black female ensures another avenue to facilitate new stories of Black girls within the comic book narrative. Using Afrofuturism also empowers Black girls to employ their creative imaginations, which allows for further exploration of how Black girlhood experiences are not monolithic. Through these frameworks and the characters in question, using a popular3 medium such as comic books, their narratives explore transformation, reclamation, #BlackGirlMagic, Black girl joy and empowerment, resistance, and perseverance, which are key elements of Black feminism and Afrofuturism.

2. Black Girl Representation in Comics

Being Black and a girl in today’s U.S. society is an involved action that is filled with racial and gender biases and is often met with adversity (Gipson 2022). When you factor in representation in pop culture and comic books, Black girl experiences become part of an unfortunate imbalance. As noted by Ruth Nicole Brown (2009), a celebration of Black girlhood and her many experiences centers on the everyday achievements that are in actuality not so commonplace. Nevertheless, there is a rising class of Black girl characters who are tipping the scales and making their presences known. A recent and consistent example that places Black girlhood at the center can be found in the all-ages comic book series Princeless from Action Lab, by creator and writer Jeremy Whitley. Inspired by his own daughters to change the narrative of young girls waiting to be saved or rescued by their “prince”, Whitley, through a Black girl lead, created a story that disrupts gender binaries, challenges and questions the expectation and stereotypes associated with being a princess. Another example of a Black girl protagonist can be seen in Milestone Media’s4 Raquel “Rocket” Ervin. Rocket’s storyline adds another layer of sophistication as her story deals with issues of police violence, income inequality, and a rare occurrence in comic books, teen pregnancy. What makes her narrative compelling is that her storyline as a teen mother becomes an example of persistence and perseverance. A final example can be seen in Robert Garrett’s Ajala: A Series of Adventures. As an independently published coming-of-age sci-fi series, it tells the story of a pre-teen budding superheroine, Ajala, from Harlem, New York, who is on a mission to protect her community from looming crime and vice. Through her story, readers go on a journey with Ajala as she navigates her high-school, family dynamics, and friendships, along with issues of gentrification. Each of these characters, as well as the ones to follow, invoke what it means to be different, have a sense of pride in being a Black girl, and what a future looks like when they are seen in it.

With a gradual rise in consistent mainstream Black girl comic book depictions (Marvel Comics’ Moon Girl/Lunella Lafayette [2015] and Shuri [2018]; DC Comics’ Thunder/Anissa Pierce and Lightning/Jennifer Pierce [2018] and Sojourner “Jo” Mullein/Green Lantern; Milestone Media Rocket [2021]),5 it becomes necessary to highlight the significance of the above-mentioned characters, as well as others, in order to combat the lingering stereotypical representations and imbalances. For many fans, “female comic book representation is something that creators have been slowly inching towards, giving us diverse women something to look up to” (Dominguez 2022). Grounded by my personal and academic interest in exploring the representations of race and gender in comic books, it was important that the characters selected for my analysis spoke to the need to address a lack of representation and that I would also acknowledge existing Black girl characters in comics and popular culture, including the notion that there have been limited viewpoints for Black girls. Centering Black girl narratives in comics contributes to and allows for, the opportunity to build and embrace more diverse representations. If Black girls are only relegated, in the white imagination, as one-dimensional, as being loud, troublemakers, sassy/having an attitude, othered, seen as inhuman/monstrous or as an enemy/villain, their existence in and out of reality is simply a dream deferred or snuffed out (Evans-Winters 2005; Morris 2007, 2016; Wright 2016; Kelly 2018; Halliday 2019; Thomas 2019; Hines-Datiri and Carter Andrews 2020). Images over time can become tools of empowerment, change ideologies, and even dismantle tropes, all of which speak to the work and efforts of intersectionality, Black feminism, and Afrofuturism. If youth grow up without diverse images and depictions, whether in books, television, and films, they are, as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie argues, confined to the dangers of a ‘single story’6 ultimately affecting their imaginations of the world around them (Thomas 2019). For this reason, highlighting an array of Black girl experiences in comic books (mainstream works from Marvel and DC and independent publications from Boom! Studios) can play a role in breaking the status quo, while giving Black girls a chance to evade social, civic, and imaginative death (Brown 2013). If these Black girls (whether fiction or reality) and their narratives are to garner attention and hopeful popularity, they have to be given a chance to exist.

3. The Art of Storytelling through Marvel Comics RiRi Williams/“Ironheart”

I am a firm believer in the idea that everyone has a story to tell and that it is just a matter of people tuning in to listen to this story. One’s story has the ability to shape opinions, reinforce or disrupt stereotypes and biases, and highlight a world that had never been imagined. Such stories have the power to “sustain us through oppression, transmit our ancient and precious traditions through all kinds of adversity…stories that move beyond the shadows to become known across the world are always connected to power, positioning, and privilege” (Thomas 2020, p. 2). And stories like that of Marvel Comics’ RiRi Williams (“Ironheart”) can inspire and formulate a sense of normalcy (especially in the STEM fields) and social acceptability, while also contributing to filling the “imagination gap” of youth literature.7 Created by comic book writer Brian Michael Bendis, RiRi makes her first comic book appearance in Invincible Iron Man Vol. 2 #7 in May 2016. Growing up as a child genius, RiRi is able to home in on her science and technological skills and talent and take up the mantle of continuing the Iron Man legacy as “Ironheart.” Breaking into the comic book scene during Marvel Comics’ move toward broadening their audience (tapping into the pre-teens and adolescent fanbase) and creating more diverse characters, RiRi presents a brilliant Black STEM girl who is a Tony Stark fan but has also created her own suit. RiRi’s actions receive the attention of Tony Stark. They lead to a meeting of the two characters and the establishment of mutual respect. While this is a part of her story, it is just the beginning. Because she is popular, the RiRi character is useful for “what Marvel has always done over the course of their history: creating a diverse universe of characters that appeal to people from all walks of life” (Tapley 2016). In the sections to follow, I want to share numerous perspectives of RiRi’s story, which include her redesigned appearance in Eve Ewing’s Ironheart series, a special appearance in a live-action video short for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Admissions department, and appearances in film and television.

3.1. Flexing the Pen to Write Black Girl Intelligence

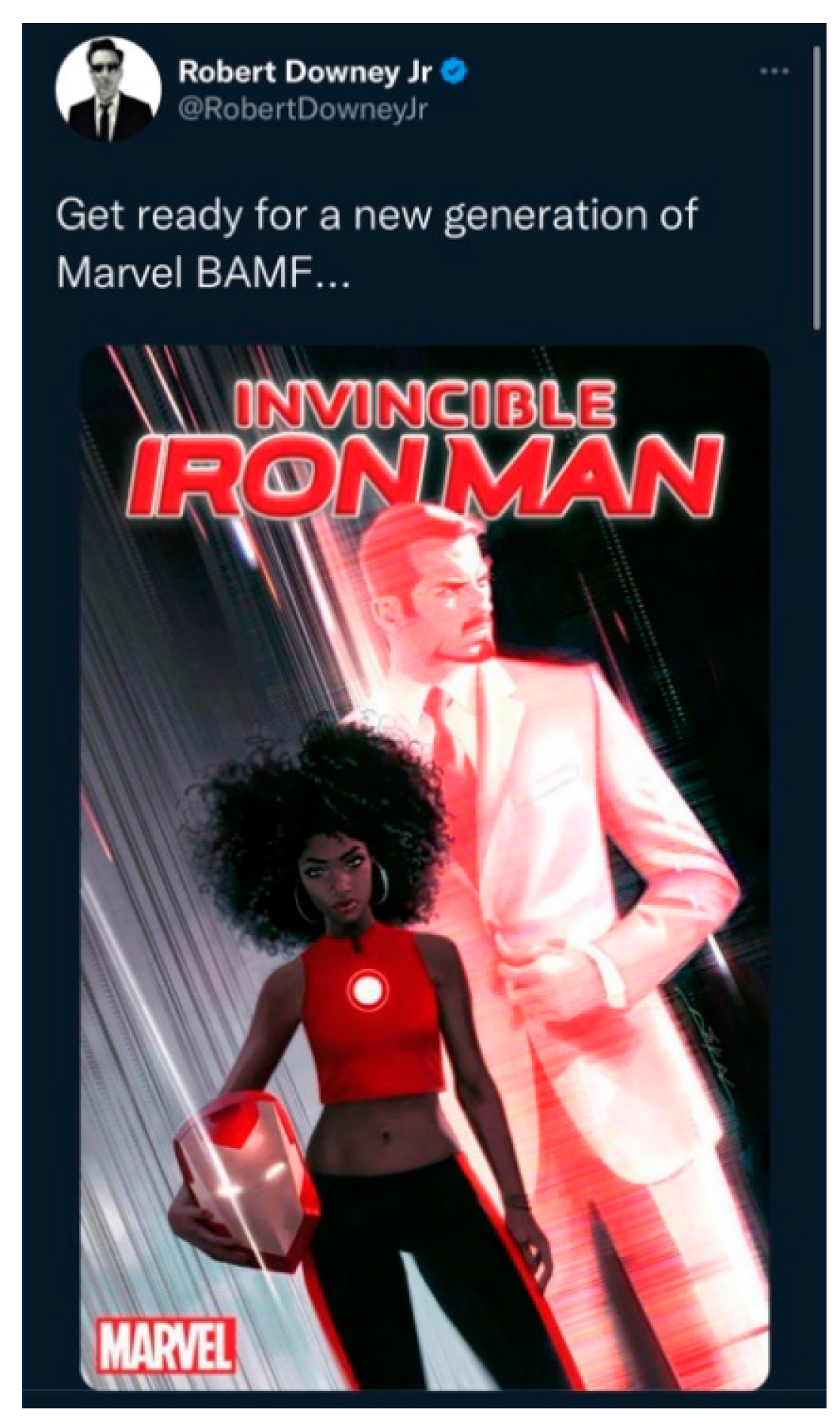

To be young, gifted, Black, nerdy, and female is an identity that taps into this notion of standing out and being different. As a newer character in the comic book medium and Marvel universe as well as a superhero genius, RiRi creates a lane for young girls to simply show up, to maintain their youth, and see themselves as part of the script without having to picture themselves as adults. As adventure-seekers and scientists, it is important to have these visible representations. RiRi’s entrance into the Marvel Comics universe was even praised and endorsed by the MCU’s Iron Man actor Robert Downey Jr., who announced: “Get ready for a new generation of Marvel BAMF…” (Figure 1). This tweet is doubly significant in that it helps to ease the minds of many fans who are attached to the classic version while also offering a sense of applicability for the entrance of a teenage Black girl superhero in a large, mainstream comic book universe. The tweet was liked more than 11,000 times, quote-tweeted more than 1300 times, and retweeted 28,500 times, which indicates both Downey’s reach as an actor from the MCU and the willingness of a sizable segment of Marvel followers to recognize these new Black Girl characters.

Figure 1.

Tweet from Iron Man actor Robert Downey Jr. in support of Riri Williams taking over for Tony Stark in the Iron Man comics (7/7/16).

While RiRi’s character makes her debut in May 2016, her story and personality take flight when University of Chicago sociology professor/poet Dr. Eve E. Ewing takes over the writing reigns after the departure of Brian Michael Bendis in 2018.8 It is also important to note that 2016 serves as a #BlackGirlMagic9 year for Marvel Comics when they hired three Black women writers (Eve Ewing, Roxane Gay, and Yona Harvey). This hiring of Black and queer women, invoking #BlackGirlMagic, is noteworthy and historical as it had not been done before. Black women are making space not just as characters, but as writers of the “comic script” (we would also see a rise in Black female illustrators during this time as well). With a revised series title, Ironheart went from simply being a “girl Iron Man” to teen student, inventor, and superheroine. As the lead writer, Ewing personalizes and humanizes RiRi’s story to include the loss of her stepfather and best friend and a necessary narrative of her Chicago origin story. As a result of Ewing’s revision and as a departure from Bendis’s caricature-like presentation, RiRi is given some humanity as a Black teen and becomes what Deborah Whaley calls a “sequential subject” (Whaley 2016, p. 8). Her character is not a diversity-checked box, but a representation of real and imagined Black girlhood.

Through Ewing’s writing, readers are able to take in Black inner-city Chicago life as personified by a teenager, without it being overrun by trauma and violence as portrayed in the previous Invincible Ironman series. In the opening pages of Ironheart issue #5, we see present-day Chicago on a summer day. Organized in two-tier columns with a total of six panels, the comic offers a range of scenes with a diverse cast, including a police car driving in front of a liquor store with a group of men engaging in conversation outside of the store; a small business owner setting up his ‘Tamales Café’ stand; a group of young men drumming on paint buckets; a group of kids playing in the water of an exposed fire hydrant; a homeless man digging through a trash can. Closing out the page is Riri’s mother, who appears stressed working as she going through some important budgeting or accounting documents. What makes the series of panels personable is Riri’s voice as she narrates each scene. Her thoughts range from how her city is perceived: “I live in a city that people call dangerous”; to finding the small wins of Chicago: “the place that makes other people feel good about where they lay their heads at night”; to the realization that “people here are struggling to survive…and a wise person once told me that the business of survival ain’t always pretty” (Ewing 2019b, Ironheart #5). This panel highlights RiRi’s vulnerability and her inside perspective into the Chicago she knows. She describes the adversity, the joys, and the stress and conveys an understanding that how one sees something depends on one’s own vantage point. Although a native of Chicago, RiRi can provide an outside perspective without being voyeuristic, still giving it some sort of identity. Her awareness of the perception of others (a subtle jab towards Bendis’s controversial interpretation)10 is narrated in her own voice. Through each of these panels, Ewing provides a reclaiming of her voice and a sense of authority to RiRi to critique outside depictions and celebrate the strengths of her home city. The issue opens with working in the importance of a Black child’s innocence and perspective. Ewing’s personal connection as a Black woman from Chicago who also has an academic background (as a trained sociologist) offers a shift in the comic book narrative, where the majority of writers (and artists) have been white and male, such as Bendis.

In addition to RiRi recognizing and celebrating Black life, we also get to see her step outside superhero mode and bond with fellow Black girl peers. While RiRi normally operates as a solo hero, in issue #10, “The Enemy Within,” RiRi teams up with fellow Black girl Marvel heroines Shuri and Silhouette. Ewing writes the script for this issue from a team mindset that is full of laughter and action. As RiRi walks into the group meeting with Shuri and Silhouette, a playful back and forth takes place, with Silhouette assigning a cute nickname: “Finally the gang’s all here. So listen here’s what we need to do Shuriri….” Taken off guard, Shuri replies, “Silhouette did you just call us Shuriri?” To which RiRi quickly quips, “That’s a NO. Hard Pass.” The humor builds as Silhouette continues to try and sell the name to RiRi and Shuri: “Oh come on. It’s an adorable nickname, like Brangelina” (Ewing 2019a, Ironheart #10). The childlike banter between the young ladies becomes a way to transition into a more serious conversation about family and legacy. Showcasing these friendships and relationships is important and necessary, as readers and fans “will have the ability to absorb the imagery and portrayals in the comics they read, subconsciously referring back to them” (Schwein 2020).

Due to RiRi’s loner status, she often does not get to cultivate friendships beyond linking up with other superheroes. So, in the next moment, she capitalizes on being transparent and opens up about the impact the loss of her stepfather has had on her. The conversation begins with RiRi asking Silhouette why she is helping her and Shuri in this latest mission. The conversation quickly shifts to Shuri sharing her appreciation of the relationship she has with her father: “[M]en always think they know what’s best. My father was different. He treated me like I always knew things. But he also always had wisdom to share”. Noticing that RiRi is being quietly observant, Shuri shifts the conversation: “You’re awfully quiet, RiRi. What about you? Do you have a good relationship with your father?” This triggers a shaken pause for reflection, with RiRi responding, “Hm? Oh. He’s dead. But I had a pretty special relationship with him. My stepfather, I mean. I had a pretty good relationship with him” (Ewing 2019a, Ironheart #10). With each panel, the reader gets a back-and-forth close-up shot of RiRi, then Shuri, and back to RiRi. In between, RiRi further acknowledges that her biological father is dead as well but that she never met him so there was nothing to miss. Shuri attempts to wrap up the conversation with a closing thought: “It seems like…you’ve been through A LOT.” And in a semi-sarcastic response, RiRi replies, “Yeah, well it be like that sometimes” (Ewing 2019a, Ironheart #10). In this tense but candid exchange, the young women bond over their paternal connections, and RiRi finds herself being receptive to sharing her grief. Even in their youth, they affirm each other, while understanding the need to be a listening ear for each other and grasping that they can collectively come together as a sisterhood to support each other.

3.2. A Decision to Reach beyond the Page

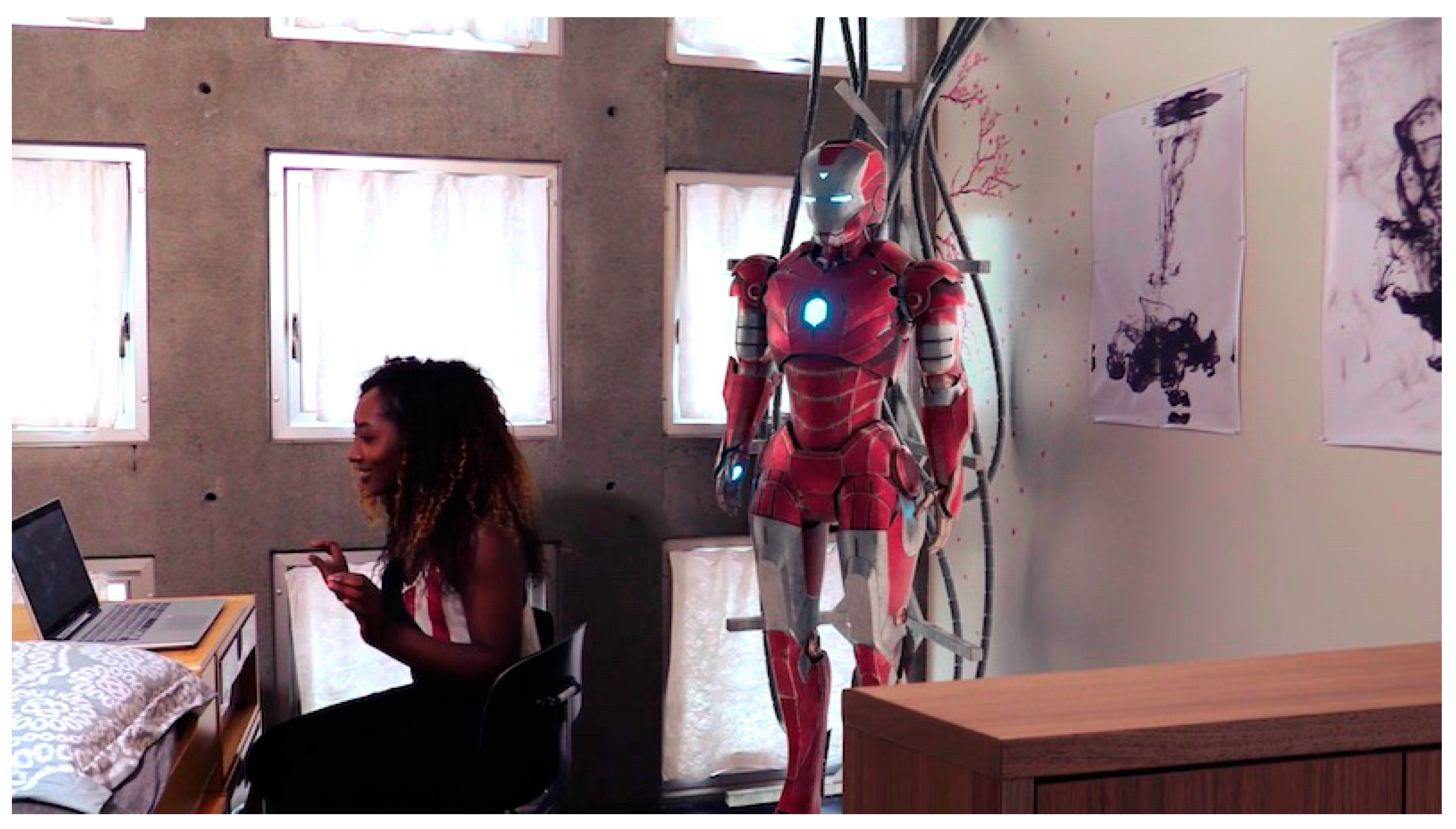

Not only has RiRi’s story made an impact on the comic book pages,11 but it has also become a part of the culture beyond comics through Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) recruitment and admission. On March 2017, MIT Admissions released a student-made short film based on the debut of the Marvel Comics character in order to inform prospective students of the university’s decisions announcement.12 The short film starred real-life MIT chemical-engineering major Ayomide Fatunde (MITbloggers 2017). Describing the film, MIT Admissions noted that “although Riri Williams is a fictional MIT black woman, she’s played by a real MIT black woman, directed by a real MIT black woman, and ‘lives’ in a real MIT black woman’s dorm room, something I thought was pretty awesome” (Gano 2017). This becomes a significant moment as MIT uses the character of RiRi, a Black young woman, to usher in future MIT students. With the tagline not all heroes wear capes, but some carry tubes, MIT was not only signaling the significance of Black girlhood to the incoming class; it also recognized the potential of women in the STEM field. As a creative recruitment tool, the action video follows RiRi (Ayomide) as she goes from sitting in class to designing and building her own super suit in her dorm room (Figure 2) and eventually heading to the office of Stu Schmill, Dean of Admissions, to help him carry out the important task of making some future incoming MIT students’ dreams come true.

Figure 2.

Still shot of MIT student Ayomide Fatunde as RiRi Williams/Ironheart for Pi Day 2017.

The ‘what-if’ style film “shows that all of Riri’s characteristics can be found, collectively, among all of the black women at MIT, and I’m glad that there’s now an additional story among all the fictional stories where people can witness this identity” (Gano 2017). Thus, the decision of the students and MIT to incorporate both RiRi and her alter-ego “Ironheart” in their decision process is notable, given the prestigious status of MIT and the current Hollywood climate of emerging Black female superheroes. Seeing Ayomide, a real-life STEM student, RiRi enables young Black women, whether in high school or on the MIT campus, to imagine themselves as future engineers. The creators also tap into the “interesting ways in which Black folks use fiction [ex. comics] in its various forms to free themselves from the bounds of fact” (Young 2012). Thus, as a short film, it also serves as a tool to explore the ability to use the creators’ voices and talents to create change. “People were excited about RiRi because she opened up the spectrum of imagination—for people in and outside of the demographic of black women…It makes you think, I can imagine a black, female, mechanical engineer—because I’ve seen one. It allows people of that demographic to imagine themselves that way, too” (Gano 2017). Fantasy may become reality if Black girls have appropriate role models.

While RiRi has had a fairly consistent showing in the comic book medium, which indicates her popularity among Marvel followers, her story has recently been translated into several other media. In 2018, RiRi starred in her own animated television special Marvel Rising: Heart of Iron (voiced by Sofia Wylie), where she teams up with the “Secret Warriors” to disarm a doomsday device and save her city. Marvel Rising: Heart of Iron serves as one of the three characters of color to a Marvel Rising special (the other characters are Shuri and America Chavez/Miss America). RiRi/Ironheart also expands her reach appearing as a playable character in several video games (Marvel Puzzle Quest, Marvel Future Fight, Marvel Avengers Academy, Lego Marvel Super Heroes 2, and Marvel Strike Force). And before making her series debut on Disney+ (Ironheart, fall 2023), we have seen her show off her skills in live action in the Marvel Cinematic Universe film, Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022). All of these media appearances are important because her character is establishing a future legacy and becomes a part of laying the groundwork for the next chapter and phase in the ongoing Marvel Cinematic Universe. Riri’s comic book popularity is not only validated but also extended through these transmedia adaptations.

In light of the long history of Black girls being victims of erasure in fiction and reality, Riri’s multiple appearances across the pop culture landscape, her apparent rise in popularity, and her attachment to STEM are noteworthy and important to acknowledge. With little representation of Black girls in the Marvel Universe, as well as in the larger comic book universe, Riri further confirms that not only does representation matter but it is necessary. Seeing superhero stories like RiRi as Ironheart disrupts the established narrative that Black characters lack nuance or must appear as tokenized characters. As noted by one comic book fan, “It’s super dope to see these two young black girls (Lunella Lafayette and RiRi Williams) out here dominating and becoming the future of a field where middle-aged white men have been the standard” (More Street Art 2017). Additionally, seeing a Black girl have a presence in multiple popular media lets fans and consumers know that they are worthy of being seen, which can also translate into reality and future possibilities. Ewing speaks to this notion of being seen: “I feel like for years a lot of black kids in fantasy culture have had to compromise, so it was important to show them they can be the hero” (Murphy 2019). The inclusion of her character, especially in the Marvel Universe, adds to the growing popularity and legacy of younger heroes like Kamala Khan, Miles Morales, and Sam Alexander.

4. DC Comics, “Naomi” Port Oswego’s Environmental/Geo-Engineer

The year 2022 was a busy one for comic book representations on television, ranging from Marvel’s Moon Knight, Ms. Marvel, and She-Hulk to Image Comics’ Paper Girls and Tales of the Walking Dead, to Vertigo’s The Sandman and DMZ. From the DC Universe, we saw #BlackGirlMagic play out in the superhero drama series Naomi. Created by Academy Award and Golden Globe-nominated director Ava DuVernay and television writer Jill Blankenship, Naomi is based on the 2019 comic book of the same name co-written by Brian Michael Bendis and David F. Walker and illustrated by Jamal Campbell. Premiering in January 2022 on The CW, Naomi is a coming-of-age drama that follows a Black teen girl’s journey (played by Kaci Walfall13) after a supernatural event from a small Pacific northwestern town to a massive multiverse.

4.1. Who Am I?

The Naomi series is one that I would describe as self-exploratory. From the opening of episode #1, “Don’t Believe Everything You Think,” we are looking through the literal lens of Naomi’s glasses as she is preparing to attend a friend’s house party. This is an episode that can be likened to an origin story and one that sets the tone for the entire season. Upon first glance, we see a fusion of Naomi’s style and personality as a skater girl, a military brat, and a huge Superman fan who caters her style to an amalgamation of 1990s fashion (Poetic Justice braids, baggy overall jeans, Nike Air Force Ones). We also learn that she is adopted (by a mother of color and a white father), which speaks to the importance that not all Black girls have the same experience and family dynamics. Moreover, the fact that her parents are not Black could be seen as a strategic mainstreaming move to make her character more palatable to white audiences. As part of this episode, viewers also get to see how the creators offer a freedom narrative where Naomi is open about whom she chooses to like and flirt with, whether it is her comic book buddy Lourdes or two male friends Nathan and Anthony. According to co-creator Ava DuVernay, the show overall is an example of normalizing the types of stories they want to see in the world. She explains: “We show a different hero, a black girl, and we’re making it normal and that’s radical/revolutionary” (Bennett 2022). An immediate engagement with Naomi’s sexuality is extremely noticeable and refreshing and a nod to this current generation’s attitude toward the fluidity of sexuality. Showrunner Jill Blankenship shared that they looked to this generation to influence the tone and approach to telling Naomi’s story (Bennett 2022). For Naomi is constantly trying to uncover the truth about who she is while simultaneously navigating her newfound identity as a superhero and accepting it as something positive and empowering. But just like any other teenager, she constantly desires to be normal and to fit in. This can be complicated even in reality, when Black girls are seen as threats, problematic, or someone who needs to be tamed.

4.2. F.I.A.R. (Face the Fear, Identify, Acknowledge, Release)

Another common theme that frequently occurs in the series is Naomi’s management of self-care. Not only is she committed, but her parents and mentors play a role in making sure it is a priority. In one of their many conversations, Naomi’s mentor Dee wants to make sure she moves away from striving to be “normal.” As part of this self-reflection, in episode #3, “Zero to Sixty”, Dee offers a series of thoughts and questions about “who determines normalcy?” Having powers, she suggests, does not mean you’re ready to use them as a threat, the power of words, and embracing change. Over the course of the series, Naomi will incorporate a mantra, F.I.A.R. (Face the Fear, Identify, Acknowledge, Release) to help with personal relationships with friends and family, navigating school and preparing for college, and the way she deals with accepting her additional identity as a superhero. The mentorship and guidance given to Naomi can be seen as a luxury since not every young girl is afforded this opportunity. For Black girls, mentorship becomes vital to avoid being thrust into the criminal justice system at an early age (Brown 2013; Morris 2016). Channeling an Afrofuturist spirit, ultimately, Black girls need space to simply exist not just in the present, but the hopeful future.

4.3. Who Gets to Save the World…A Black Teen Girl

What is also important to note, much like the significance of Eve L. Ewing writing the Ironheart series, is that the majority of the directors for each episode are Black (a total of 8 out 13, with 4 being Black women [DeMane Davis, Neema Barnette, Angel Kristi Williams, Merawi Gerima]). With film and television having very little minority representation among top management and boards, and a need to advance racial and gender equity, concerted action and the joint commitment of stakeholders across the industry ecosystem is essential (Dunn et al. 2021). The “Naomi” script with its diverse casting of characters and directors speaks to the efforts of rendering Black girls visible and redefining who gets to save the world. These efforts also channel the work of Black feminists as they work towards giving agency to Black women’s experiences, changing societal systems, and dismantling racial and gender inequities. In essence, Naomi serves as a radical act of transformation that DuVernay explains moves beyond representation: “[I]t’s not about representation, it’s about normalization… The more you can portray images without underlining or highlighting them and putting a star next to them. By showing a different type of hero that centers a girl, a Black girl, that centers different kinds of folks. We start to make that normal and that’s a radical and revolutionary thing” (Steiner 2022).

Unfortunately, Naomi’s story is cut short, and the series was canceled after only one season due to a struggling viewership and the recent Discovery and Warner Bros. merger (Oddo 2022). Along with premiering in the midst of a merger, Naomi also fell victim to not being marketed properly, with commercial considerations potentially overriding the wish for more and better representation. Instead of pushing stories like Naomi’s that feature forward-thinking visuals of Black girlhood to the margins (Hooks 2014), producers need to be enticed to create more narratives that speak to various lived experiences. While the cancellation of the show can be seen as a failure, the existence of her character has left a mark that can live on beyond the show. As proclaimed by Book Riot journalist Aurora Lydia Dominguez, Naomi’s character “represents a powerful Black teenage superhero, one that young Black girls can look up to and feel represented by” (Dominguez 2022). She goes on to argue: “it’s not just about this female superhero having unique superpowers, it’s about what this symbolizes: that diverse women can truly fulfill their destiny, find strength within themselves, and showcase their strengths in front of their male counterparts” (Dominguez 2022). Others have also noted that Naomi’s story and the series can be likened to this notion of a Black Girl transforming the superhero space. The series is representative “of those historically marginalized by major superhero stories; Naomi is for the people who are usually excluded from representation of this kind but know they’re badass enough to be the stars of their own universe” (Andrea 2022). Thus, with this quick cancellation, we are left to wonder about the potential popularity and what might have been further developed in Naomi’s television comic book narrative.

5. Adventures of a Pre-Teen Explorer in Boom! Studios’ Eve

When thinking about the representation of Black girls in comics and popular culture, I want to make sure to include experiences before adolescence. In my research, most of the characters that are explored vary from teenagers to young adults. Thus, I feel that it is necessary to include BOOM! Studios’ Eve, which offers an under-researched perspective into Black girl middle childhood. Debuting in May 2021, Eve is an original five-issue series by award-winning author Victor LaValle and rising artist Jo Mi-Gyeong. It tells the story of an 11-year-old Black girl named Eve, who embarks on “a dangerous journey across a future dystopian America to save the world.” As a departure from the larger two comic book publishing companies, the character of Eve in many ways creates her own path because she does not have to come from behind the shadows of existing, long-standing characters. Her series is another example of the future possibilities of Black girls as main protagonists not just in comic books but within genres like science-fiction, fantasy, or magical realism, where they are still not featured or seen as much.

“What kind of planet are we leaving to our kids?,” LaValle asks at the end of Eve issue #1. This is a poignant question that also serves as a motivation for the creation of this comic book and one that he is constantly wrestling with through his own personal life and work. Through this question, LaValle explains the importance and necessity of telling a story like Eve’s:

“Many generations have wrestled with it, but the question has never been as immediate…But I didn’t want to write some grim story about how this joint went to hell. Instead, I wanted to write a story about how we let the planet fall apart and left it to younger generations to fix it. So, this is a story, inspired by young folks like Mari Copeny, Else Mengistu, Greta Thunberg and so many more, of how an eleven-year old girl, Eve, and her android teddy bear try to do the seemingly impossible: save the planet, save us.”(Broken Frontier Staff 2021)

Here, LaValle addresses a societal need for change and how a younger generation is stepping up to the task to get the job done. Taking it a step further, LaValle is giving this responsibility and power to an eleven-year-old Black girl. But what does it mean to write a story about a young Black girl, like Eve, who holds so much responsibility?

Picture this, a young precocious Black girl navigating a dense mangrove tree landscape maze filled with wooden bridges and crabs climbing the branches. With a walkie-talkie in her hand, this eleven-year-old named Eve is embarking on a utopian journey where she is the lead explorer. As she leaps from tree to tree, talking to herself, a voice comes through the walkie-talkie: “[Y]ou finished with the perimeter sweep?,” asks her father. She then races back home to her father to have dinner, recap from her adventure, and discuss plans for the future. What follows their conversation is a walk to a mysterious doorway and a shocking revelation for Eve. Before opening the door, Eve’s father shares with her, “you’ve made this place feel like a home. It won’t be the same without you.” To which Eve replies, “Daddy I don’t understand…you’re scaring me.” In this moment, Eve realizes her playful adventures were actually training sessions, as her father was preparing her for journey of self-discovery and survival. In his last words to his daughter, he is essentially passing the torch for her to jump into an unknown reality: “[Y]ou have to open this yourself, little one. I can’t do it for you” (LaValle 2021a, Eve #1). This opening begins Eve’s mission to get back to her father and save the world. At a young age, Eve is given tremendous responsibility, designed for a superhero even though she is not one. In the first issue, we see how Eve handles her new reality guided by an android teddy bear named Wexler, programmed by her father. Readers early on see her fears, frustrations, and how she struggles with the destruction that has taken over her Jackson Square community. In spite of the dystopian reality and her imperfections, Eve is still motivated to take on the mission as a way to possibly reconnect with her father.

Eve’s story is not only about self-discovery but an example of how children operate through life when faced with ongoing obstacles. Even at a young age, Eve understands that she has to be her own champion. Very early on we see how Eve is very transparent with her emotions. In one panel, we see her looking up toward the sky talking to her mother, who has passed away, assuring her that she is ok. “Are you there Mom? It’s Me. Eve…You’re probably worried about me, but I know how to pilot that craft below” (LaValle 2021b, Eve #2). In this moment, Eve is confident in her ability to navigate this part of her mission. And even though Eve’s mother is not alive to physically protect her, Eve still offers this reassurance. This is also an example of how kids operate without fear, while adults typically operate in protection mode. In this same issue, we also see Eve’s burgeoning curiosity. As she continues to escape what’s left of New York City, accompanied by her companion Wexler, Eve encounters a team of mutant stalkers. Staying one step ahead of them, Eve begins wondering how they came to be mutants. Communicating through a crown helmet, Eve asks Wexler, “How did it work? Did people get sick one day and turn into…those things?” To which he explains that they were consumed by a virus. This response leads to a further inquiry from Eve: “[S]o we’re making this trip because the danger hasn’t passed right? The virus remains active?” (LaValle 2021b, Eve #2). Eve does not want simple answers; she would rather be told the hard truth versus be pacified. As noted by the author in the issue’s closing notes, a lesson he learned while attending a writing conference was that when writing YA stories like Eve’s that tackle tough problems, “don’t write for adults, write for the reading audience” (LaValle 2021c, Eve #3). In essence, be honest, and truthful, and trust that kids know the world can be a vicious place. Thus, through Eve’s confidence and curiosity, the above-noted examples serve as teachable moments in which we see how one should not underestimate how much children are able to handle.

Operating through an Afrofuturistic lens, the Eve series engages with technology, speculative, and reclamation. Eve uses VR and AI tools left by her father; she runs from supernatural beings and uses her imagination to create a future new normal. This latter sentiment is something of which she constantly reminds herself: “Instead of thinking about what went wrong in the past, I want you to imagine how you can do some good during what comes next” (LaValle 2021d, Eve #5). Eve’s bravery, much like RiRi’s and Naomi’s, is a reminder that when given an opportunity to be heard and seen, Black girls’ stories have the possibility to change the media landscape and the way they are perceived in society. In the end, despite the spreading of the virus, Eve is successful in her pursuit to save the world even when others have lost hope. For Eve, “we found love in a hopeless place” (LaValle 2021d, Eve #5). themes like fear, parent loss, climate crisis, references to COVID-19, and survival, Eve offers the possibility that even in reality the world can still be saved. This possibility is revisited as Eve’s story continues with Wexler and her sister in the latest series Eve: Children of the Moon (debuting in October 2022).

6. The Rising Possibilities

As the comic book landscape continues to expand and grow, diversity still remains a heavily discussed topic. As noted by comic book creator C. Spike Trotman, “diversity of every sort—racial diversity, gender diversity, acknowledging minority sexualities—is experiencing an explosion of recognition and representation in comics” (Hudson 2015). This is especially significant in the case of the Marvel and DC publishing companies adding teen characters to their roster. The past 10 years have seen a steady increase in the number of young characters of color entering the comic book landscape as main/central characters, whether via comic books, television, and/or film formats (see Table 1). This increase in young characters of color, particularly in works by Marvel and DC, is significant and noteworthy considering how a character builds popularity if they are included. Furthermore, including characters like the ones mentioned above, especially for young readers who match their identities, is relatable and can be viewed as inspirational and aspirational.

Table 1.

Mainstream New Class of Young Characters of Color.

Diversity and inclusion, especially in younger characters, also open doors for new genres or genres that have been ignored but are getting more attention in comic books. These characters, as well as the ones explored in the article, offer a relatability that is not primarily relegated to hetero-white men. More diverse characters can also enable stories that engage with different walks of life. For example, Ms. Marvel’s (Kamala Khan) story (both in her Disney series and the comic book) taps into the role of religion and faith through the lens of social justice. She’s a Muslim and a Pakistani-American teen living in New Jersey who goes to parties, deals with disappointments and heartaches, has crushes and insecurities. Ms. Marvel highlights a story that is universal while also being specific. Considering the one-dimensional narratives often associated with Muslim people, including terrorism and orientalist tropes, it is crucial to re-condition and provides a more relatable and empowering reflection. Another prominent character is Static Shock (Virgil Hawkins) of Milestone Media. While he has one of the earlier appearances in comics and television, pre-dating Miles Morales by many years, Static Shock offers a perspective from a Black teen boy who is a highly gifted student with interests in science-fiction, technology, comic books, and role-playing games. As an animated television series that premiered in 2000, Static Shock was unapologetically political and engaged with a variety of heavy topics, such as homelessness, mental health, racism, gangs, and gun violence. Compared to other kid and superhero shows of that time, Static Shock’s cultural and political commentary was integral to the show’s DNA (Dominguez 2020). All in all, just because these characters are young does not mean they are oblivious to what is happening in the world around them. If anything, their stories as well as others offer a beacon of hope of what is to come in the future.

Not only do we see the rising possibilities of young characters of color in the Marvel and DC universes, but we are also seeing an influence on a global scale, particularly in Africa. While there have been locally produced African superhero comics from Africans since 1980s, this popularity increased in 2016 due to the rise of Marvel Studios superhero films (Wangari 2022). Embracing an Afrofuturist framework and an exploration of diasporic Blackness and girlhood, an example of this impact can be seen in the newest Netflix series Mama K’s Team 4. As an original and the first animated series from Africa, Mama K’s Team 4 follows four teenage girls who live in a futuristic Lusaka, Zambia, and are recruited by a retired secret agent to save the world. Inspired by creator and Zambian writer Malenga Mulendema to change the way cartoons have been portrayed in her home country, Mulendema wanted to see herself in a medium that often left her out. She aimed at “creating a superhero show set in Lusaka, I hope to introduce the world to four strong African girls who save the day in their own fun and crazy way…and most importantly, I want to illustrate that anyone from anywhere can be a superhero” (Vourlias 2019).

In addition to the debut of Netflix’s Mama K’s Team 4, Africa has also contributed more specifically to the comic book and graphic novel genre with the work of Marguerite Abouet. Her Aya series depicts the normal life of residents of the Ivory Coast as seen through the eyes of a Black/African teen girl named Aya. Abouet’s depiction of daily African life disrupts the western viewpoint, which primarily focuses on famine, civil war, and unhinged wilderness. As an award-winning comic book/graphic novelist, Abouet, as a writer, is very intentional with her characters’ portrayals, highlighting them going to school and work, having fun with family and friends, and planning for their futures. The Aya series also gained global popularity as it has been translated into 15 languages and turned into an animated film (“Aya of Yop City”) distributed internationally by the Institut Français, and it also received the 2018 Prix des jeunes cinéphiles francophones (Prize for Young French-Speaking Film Enthusiats). All in all, both African creators, much like their U.S. counterparts, are contributing to the global popularity by telling stories that invite their African readership into the genre while simultaneously yearning for more diversity, representation, and authenticity in their stories.

When we consider comics as a quantitative phenomenon, we can note that comic book sales reached USD 2.075 billion (the largest in the industry) in 2021, with 13–29-year-olds buying 57% of all comics (Clark 2022; Georgiev 2022). Comic books continue to be a thriving business with collectors and fans still making the financial investment. A part of this success is attributed to a few factors: rediscovering hobbies during the COVID-19 pandemic, increased popularity in certain genres, and streaming services like Amazon Prime Video, Netflix, HBO Max, and Disney+ featuring new shows and movies (Marvel Cinematic Universe and DC Comics). Consumers are obviously seeking out the source material. Additionally, children’s comics and graphic novels have become increasingly popular because parents are seeing them as a “gateway into reading” (Clark 2022). While some fans and consumers may view RiRi, Naomi, Eve, and other diverse stories as manufactured diversity (Cain 2017),14 their narratives explore why their inclusion and range are necessary while also serving as a turning point in American visibility. With each month, these stories and others are becoming more commonplace and accessible to consumers. According to one retailer, increased diversity has brought a new clientele to his store, as the diverse comics “do bring in a different demographic, and I’m happy to see that money in my store” (Griepp 2017). Furthermore, with the existence of movies and series/shows like Disney’s Ms. Marvel and Marvel Rising: Operation Shuri (voiced by Daisy Lightfoot), The CW’s Black Lightning, and the upcoming Disney Channel animated series Marvel’s Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur (voiced by Diamond White) to complement the digital and physical comic books, Black girls are continuing to make space, imagine alternative futures, and exemplify that being a Black girl is something to be proud of.

Girlhood, in particular Black girlhood, in comics is expanding beyond just the comic book page and steadily branching into more media (mainstream and independent). While the increase in mainstream recognition is not always massive, although steady, there is a popularity of Black female character storylines in the independent space, which contributes to their overall representation. For many, success and popularity are not solely based on the validation of dominant publishers. As noted by veteran comic book editor Joe Illidge, “I don’t think the goal should be to try and break into DC and Marvel… I think the goal is we have to build our own houses and then in time be as big as DC and Marvel” (Lynn 2018). This is important to recognize as it can help to reconsider and redefine what is deemed popular and to whom. Even in spite of cancellations, the opportunity for a show to exist, or a comic book series to hit bookshelves, is an accomplishment on its own, especially when considering the lack of exposure in the past.

7. What These Black Girl Superheroes Taught Me

So, what did these Black girl superheroes teach me? These characters as well as others provide a change in my thinking. I am becoming less surprised when I see them in a comic book, leading a television series, or making a stand-out performance in a Hollywood blockbuster film; instead, I am more encouraged. Revisiting RiRi, Eve, and Naomi’s stories transports me back to my own childhood while giving me the confidence to declare that Black girls are the future, whether locally, nationally, or even globally. Comics are widely accessible, e.g., online sites such as Comixology (https://support.comixology.com/hc/en-us, accessed on 14 March 2023), Comic Book Plus (https://comicbookplus.com/, accessed on 14 March 2023), DriveThru Comics (https://www.drivethrucomics.com/, accessed on 14 March 2023), Digital Comic Museum (https://digitalcomicmuseum.com/, accessed on 14 March 2023), and Libby (https://www.overdrive.com/apps/libby, accessed on 14 March 2023) or in local libraries. They are being taught in K-12 and collegiate classes, and their characters are featured in television and film. Having such a wide-ranging impact, comics offer Black girls and teens the opportunity to not only imagine who they could be but also act on it. As the comic book superhero narrative gradually includes younger voices, especially Black girls, we as scholars and fans can consider the ways in which their stories can be utilized as a valuable tool not only to teach but also to facilitate critical conversations around popularity, power, race, class, gender, privilege (Dallacqua and Low 2019) and their relationship with popular culture. These stories make statements and serve a purpose in which their popularity is within a particular space. For example, PBS Media founder and engineer Naseed Gifted notes that he creates and uses comics with Black stories “to get students interested in STEM” (Lynn 2018). Here, the comic book becomes a vehicle to reach audiences of fans and introduce them to others. While characters like RiRi, Eve, and Naomi exist in a fictional comic book and television show landscape, their narratives resonate with an array of Black girl realities. I can even remember as an eight-year-old Black girl reading the latest X-Men series, watching Transformers and Scooby-Doo as part of my Saturday cartoons routine, and anxiously awaiting getting my copy of the Sunday Funny Papers. During each of the 30 min syndicated programs, I would escape my reality and transport myself into a colorful fantasy. Now what would have made this an almost utopian experience would have been the opportunity to see more characters that looked like me or shared my reality. As more stories of Black girls like RiRi, Naomi, and Eve are created and presented in multiple formats, in comics, popular culture more broadly, and the academy, their presence becomes a game-changer and works toward filling the gaps in existing genres and narratives.

Each of their narratives provides new representations, new voices, and redefinitions of Black girlhood, creating new worlds while “dismantling problematic and artificial boundaries obstructing Black liberation” (Moore 2017). It is crucial to have a wide range of images and possibilities for Black girls so that as they grow up their imaginations do not have to be stifled or diminished based on preconceived notions. Their narratives, whether in the comic book or television format, also create discourses on the intersections of race, gender, sexuality, religion, etc., and on how those identities navigate “living in a racialized society” (Kirkpatrick and Scott 2015, p. 120). Especially in the portrayal of the classroom space, regardless of age, all three girls manage to find ways to define themselves for themselves. It was necessary to analyze more than one Black girl experience across a range of ages so as not to limit the Black girl voice to a single iteration. RiRi, Naomi, and Eve are inventive examples of adventure-seekers, innovators, and freedom fighters who encourage Black girl empowerment. They challenge oppression, push back against the labels placed on Black girls, refuse restrictions, and make meaning of their identities. Ultimately, RiRi, Naomi, and Eve are not only trying to save their communities and the world. They are also contributing to revising the future Black girl script, in and outside of popular culture. The greater the access and representation are, the more opportunities arise to make space for other Black girls and teens to imagine the possibilities of seeing themselves in a world where they are not normally seen or represented.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See Phillis Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (Wheatley 1793) and Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (Jacobs 1861). |

| 2 | See W. E. B. Du Bois’s The Brownies’ Book (Du Bois 1920). |

| 3 | I define popular as being regarded with favor, approval, or affection; and popular culture as the collection of arts, entertainment, beliefs, and values that are shared by large sections of society. |

| 4 | Milestone Comics was renamed Milestone Media in January 2015. |

| 5 | These are representations in comic book, television, and film formats. |

| 6 | This is in reference to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s (2009) TEDTalk on “The Danger of a Single Story”. |

| 7 | In Ebony Elizabeth Thomas’s text The Dark Fantastic: Race and the Imagination from Harry Potter to the Hunger Games (Thomas 2019), she addresses several conversations surrounding the lack of diversity in children’s stories and how they promote an imagination gap in youth literature, media, and culture. More specifically, these disparities are argued in two 2014 New York Times op-ed essays from notable Black children’s author Walter Dean Myers and his son Christopher Myers, “Where Are the People of Color in Children’s Books?” and “The Apartheid of Children’s Literature”. |

| 8 | Ewing’s arrival can be attributed to a variety of reasons including fans petitioning Marvel to give her authorship of Ironheart in 2017, their disappointment in Bendis’ aesthetic portrayal of RiRi Williams, as well as his departure to DC Comics. Ewing’s hire is also part of another trend to give a voice to Black women writers with university affiliations. Nnedi Okorafor, the author of Marvel’s Shuri series, is another example in this context. [https://www.change.org/p/marvel-hire-eve-ewing-for-marvel-s-invincible-iron-man-comic-book] (accessed on 10 November 2022). |

| 9 | As a hashtag that celebrates beauty, power, and resilience of Black women and girls, it also celebrates their work and contributions to a field dominated by white men. Connecting it to the writers also shows how the hashtage can translate beyond a social media illustration. |

| 10 | Bendis was highly criticized for his marginalization of RiRi and lack of outside input regarding her experiences as a Black girl (https://geeksofcolor.co/2017/06/23/comics-riri-williams-and-the-limits-of-representation/) as well as the sexualization of how she was drawn in a variant cover (https://www.dailydot.com/parsec/riri-williams-variant-cover-iron-man-campbell-controversy/) (both accessed on 10 November 2022). |

| 11 | Since the publication and appearance of Ironheart in comics, she would be ranked 4th in CBR.com’s 2021 “Marvel: 10 Smartest Female Characters” list, just under Athena (#3), Brainstorm (#2), and fellow Black girl superhero Moon Girl (#1). Then, in 2022, Screen Rant included her in their “MCU: 10 Most Desired Fan Favorite Debuts Expected In The Multiverse Saga” list, as one of only two women included. |

| 12 | Annually, MIT debuts a creative video that informs prospective students when the school’s admissions are released, which is on March 14th (Pi Day… 3.14). This creative video would continue in the legacy of MIT using pop culture figures to bring in students to the university. In 2016, they featured a computer-generated version of BB-8 from Star Wars: The Force Awakens. |

| 13 | Kaci Walfall is only the second Black woman to lead a DC superhero show on The CW; the first is Javicia Leslie, who played Batwoman/Ryan Wilder. |

| 14 | Manufactured diversity is defined as media products that have a superficial use of inclusion. As noted by Arizona State University professor Michelle Martinez, “diversity is manufactured if the characters have no nuance or specificity, no relationship to their home communities, are written as caricatures or stereotypes and are portrayed as in need of or dependent on the white main character” (Robbins 2019). |

References

- Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi. 2009. The Danger of a Single Story [Video]. YouTube, October 7. Available online: https://youtu.be/D9Ihs241zeg (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Andrea, Marks-Joseph. 2022. Naomi’s True Power Is Black Girl Magic. Tilt Magazine, February 19. Available online: https://tilt.goombastomp.com/tv/naomi-the-cw/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Bennett, Tara. 2022. ‘Naomi’ Not Only Introduces a New Superhero, But Also Plans to Normalize Things Not often Seen on TV. SYFY Official Site, January 7. Available online: https://www.syfy.com/syfy-wire/naomis-black-bisexual-superhero-breaks-ground-says-ava-duvernay (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Broken Frontier Staff. 2021. Eve—New Limited Series by Victor LaValle and Jo Mi-Gyeong Debuts this May from BOOM! Studios. Broken Frontier: Exploring the Comics Universe, February 18. Available online: https://www.brokenfrontier.com/eve-victor-lavalle-boom-studios/ (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Brown, Ruth Nicole. 2009. Black Girlhood Celebration: Toward a Hip-hop Feminist Pedagogy. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Ruth Nicole. 2013. Hear Our Truths: The Creative Potential of Black Girlhood. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cain, Sian. 2017. Marvel Executive Says Emphasis on Diversity May Have Alienated Readers. The Guardian, April 3. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/apr/03/marvel-executive-says-emphasis-on-diversity-may-have-alienated-readers (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Clark, Travis. 2022. Comic-Book Sales Had Their Best Year Ever in 2021—And This Year Is on Pace to Be Even Better. Here’s What’s behind the Surge, from Manga to ‘Dog Man’. Business Insider, July 13. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/whats-behind-surge-in-comic-sales-movies-kids-comics-manga-2022-7 (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 2000. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1991. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review 43: 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallacqua, Ashley K., and David E. Low. 2019. “I Never Think of the Girls”: Critical Gender Inquiry with Superheroes. English Journal 108: 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez, Aurora Lydia. 2022. Why Diverse Female Superheroes Are so Impactful|Book Riot. BOOK RIOT, June 7. Available online: https://bookriot.com/diverse-female-characters-in-comics/ (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Dominguez, Noah. 2020. 20 Years Ago, Static Shock Proved Kids Can Handle Political Superheroes. CBR.com, February 16. Available online: https://www.cbr.com/static-shock-cartoon-political-retrospective/ (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt. 1920. The Brownies’ Book; New York: DuBois and Dill, to 1921 [Periodical] Retrieved from the Library of Congress. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/22001351/ (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Dunn, Jonathan, Sheldon Lyn, Nony Onyeador, and Ammanuel Zegeye. 2021. Black Representation in Film and TV: The Challenges and Impact of Increasing Diversity. McKinsey & Company, March 11. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/black-representation-in-film-and-tv-the-challenges-and-impact-of-increasing-diversity (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Edwards, Rachael. 2016. 5 Comic Books with Black Female Lead Characters You Should Be Reading. The Culture, February 5. Available online: http://theculture.forharriet.com/2016/02/5-comic-books-with-black-femalelead.html (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Epstein, Rebecca, Jamilia Blake, and Thalia González. 2017. Girlhood Interrupted: The Erasure of Black Girls’ Childhood. Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality. Available online: https://genderjusticeandopportunity.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/girlhood-interrupted.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Evans-Winters, Venus E. 2005. Teaching Black Girls: Resiliency in Urban Classrooms. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, Eve L. 2019a. Ironheart #10. New York: Marvel Comics. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, Eve L. 2019b. Ironheart #5. New York: Marvel Comics. [Google Scholar]

- Gano, Selam. 2017. The Making of the Riri Williams Pi Day Video. MIT Admissions, March 9. Available online: https://mitadmissions.org/blogs/entry/the-making-of-the-riri-williams-pi-day-video/ (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Georgiev, Deyan. 2022. 13+ Comic Book Sales Statistics You Need to Know in 2022. Techjury, April 22. Available online: https://techjury.net/blog/comic-book-sales-statistics/#gref (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Giddings, Paula J. 1984. When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America. New York: W. Morrow. [Google Scholar]

- Gipson, Grace D. 2022. #BlackFemaleIdentityConstructions: Inserting Intersectionality and Blackness in Comics. In Teaching with Comics: Empirical, Analytical, and Professional Experiences. Edited by Robert Aman and Lars Wallner. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 255–76. Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-05194-4 (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Griepp, Milton. 2017. MARVEL RETAILER SUMMIT—DAY 1—‘Addressing Retailer Concerns, Part 1’. ICV2, March 31. Available online: https://icv2.com/articles/news/view/37154/marvel-retailer-summit-day-1 (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Halliday, Aria S., ed. 2019. The Black Girlhood Studies Collection. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hines-Datiri, Dorothy, and Dorinda J. Carter Andrews. 2020. The Effects of Zero Tolerance Policies on Black Girls: Using Critical Race Feminism and Figured Worlds to Examine School Discipline. Urban Education 55: 1419–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooks, Bell. 2014. Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center, 3rd ed.London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, Lauren. 2015. It’s Time to Get Real About Racial Diversity in Comics. WIRED, July 25. Available online: https://www.wired.com/2015/07/diversity-in-comics/ (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Jacobs, Harriet A. 1861. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself, with Related Documents. Edited by Jennifer Fleischner. New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Lauren Leigh. 2018. A Snapchat Story: How Black Girls Develop Strategies for Critical Resistance in School. Learning, Media and Technology 43: 374–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, Ellen, and Suzanne Scott. 2015. Representation and Diversity in Comic Studies. Cinema Journal 55: 120–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFleur, Ingrid. 2011. Visual Aesthetics of Afrofuturism- TEDx Fort Greene Salon [Video]. YouTube, September 25. Available online: https://youtu.be/x7bCaSzk9Zc (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- LaValle, Victor. 2021a. Eve Vol. 1. Los Angeles: BOOM! Studios. [Google Scholar]

- LaValle, Victor. 2021b. Eve Vol. 2. Los Angeles: BOOM! Studios. [Google Scholar]

- LaValle, Victor. 2021c. Eve Vol. 3. Los Angeles: BOOM! Studios. [Google Scholar]

- LaValle, Victor. 2021d. Eve Vol. 5. Los Angeles: BOOM! Studios. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Shireen. K. 2020. Introduction: Black Girlhood. The Black Scholar 50: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, Samara. 2018. The Business of Black Comic Books. Black Enterprise, July 9. Available online: https://www.blackenterprise.com/the-business-of-black-comic-books/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- MITbloggers. 2017. Not All Heroes Wear Capes—But Some Carry Tubes (Pi Day 2017) [Video]. YouTube, March 7. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=drl5gD3AzT4 (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Moore, Nathan Alexander. 2017. An Ode to Wildseeds. Departures in Critical Qualitative Research 6: 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More Street Art. 2017. Marvel Girl Magic. Medium, March 16. Available online: https://medium.com/@boringblackboy/marvel-girl-magic-79e6d8eabf49 (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Morris, Edward W. 2007. “Ladies” or “Loudies”? Youth & Society 38: 490–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Monique. 2016. Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools. New York: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, Keith. 2019. Marvel Comics’ Ironheart Writer Eve L. Ewing Is Ultimate Chicago Sports Homer. Andscape, January 7. Available online: https://andscape.com/features/marvel-comics-ironheart-writer-eve-l-ewing-is-ultimate-chicago-sports-homer/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Oddo, Marco V. 2022. ‘Naomi’ Cancelled after Season 1 at The CW. Collider, May 12. Available online: https://collider.com/naomi-canceled-the-cw/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Robbins, Lisa. 2019. Diversity in Fandom: How the Narrative Is Changing. ASU News, October 18. Available online: https://news.asu.edu/20191018-creativity-diversity-fandom-how-narrative-changing (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Schwein, Uncultured. 2020. The Comic Book Future Is Black and Female. Medium, September 20. Available online: https://aninjusticemag.com/the-comic-book-future-is-black-and-female-73a0860af162 (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Steiner, Chelsea. 2022. Ava DuVernay Has Big Plans for the ‘Naomi’-Verse. The Mary Sue, January 11. Available online: www.themarysue.com/ava-duvernay-has-big-plans-for-the-naomi-verse/ (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Tapley, Peter. 2016. Point-Counterpoint: How Do Comic Book Fans Respond to the New Iron Man? The Journal-Queen’s University, August 2. Available online: https://www.queensjournal.ca/story/2016-07-31/opinions/what-does-riri-williams-mean-for-the-future-of-iron-man/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Thomas, Ebony Elizabeth. 2019. The Dark Fantastic: Race and the Imagination from Harry Potter to the Hunger Games. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Ebony Elizabeth. 2020. Young Adult Literature for Black Lives: Critical Storytelling Traditions from the African Diaspora. International Journal of Young Adult Literature 1: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vourlias, Christopher. 2019. Netflix Picks Up Its First Animated Series from Africa, ‘Mama K’s Team 4’. Variety, April 16. Available online: https://variety.com/2019/tv/news/netflix-first-animated-series-africa-mama-k-team-4-triggerfish-1203189786/ (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Wangari, Njeri. 2022. Seven African Comics and Graphic Novels that Center Black Experiences Are Being Adapted to Film. Global Voices, February 24. Available online: https://globalvoices.org/2022/02/18/7-african-black-comics-and-graphic-novels-that-are-being-adapted-to-film/ (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Whaley, Deborah Elizabeth. 2016. Black Women in Sequence: Re-inking Comics, Graphic Novels, and Anime. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley, Phillis. 1793. Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. London: Archibald Bell. [Google Scholar]

- Womack, Ytasha. 2013. Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-fi and Fantasy Culture. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Nazera Sadiq. 2016. Black Girlhood in the Nineteenth Century. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Kevin. 2012. The Shadow Book. In The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness. Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, p. 34. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).