Abstract

The Holocaust is a living trauma in the individual and collective body. Studies show that this trauma threatens to be reawakened when a new and traumatic experience, such as illness, emerges. The two traumas bring to the fore the experiences of death, pain, bodily injury, fear of losing control, and social rejection. This article examines the manifestation of this phenomenon in art through the works of three Jewish artists with autobiographical connections to the Holocaust who experienced breast cancer: the late Holocaust survivor Alina Szapocznikow, Israeli artist Anat Massad and English artist Lorna Brunstein, daughters of survivors. All three matured alongside the rise and development of feminist art, and their works address subjects such as femininity and race and tell their stories through their bodies and the traumas of breast cancer and the Holocaust, transmitting memory, working through trauma, and making their voices heard.

1. Introduction

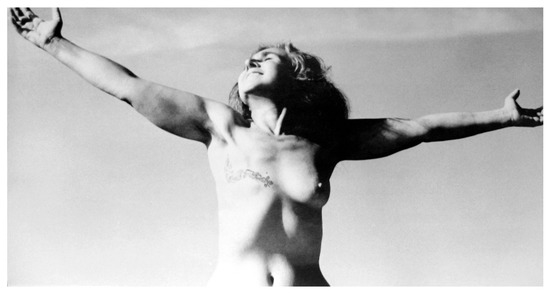

In 1977, German American photographer Hella Hammid captured Deena Metzger in a memorable photograph (Figure 1) titled The Warrior or Tree. In it, the forty-year-old Metzger is seen from the waist up, unclothed and showing her body with one breast and a tattoo of a flowering tree branch over a mastectomy scar that stretches from her arm to her heart. She flings her arms outward and looks to the sky in a declaration of vitality and freedom, challenging conventions regarding cancer, female beauty, and nudity.

Figure 1.

Deena Metzger, The Warrior, photograph by Hella Hammid, 1977. Courtesy of Deena Metzger and the Estate of Hella Hammid.

Deena Metzger was born in 1936 in New York to Jewish immigrant parents from eastern Europe who were committed to Yiddish cultural and spiritual life. In the 1960s and 1970s, she established a career as a writer, poet, educator, and feminist scholar. Following her breast cancer diagnosis and mastectomy in 1977, she published her first book, Tree, on healing from the disease (Metzger [1978] 1997). The Warrior and Tree were among the first embodiments of her lifelong interdisciplinary research, writing, and teaching, all of which integrate social justice issues, creativity, and healing. In 1977, Metzger wrote about her thoughts regarding illness:

These diseases which afflict us out of season are sociological, political, psychological, and spiritual events… Understanding cancer, for example, as imperialistic has helped me see the relationship between the personal and the political. So, illness, as it afflicts us and breaks us down, also enlightens us and presents the means to heal far more than it has undermined.

I have spent my entire life thinking about disease, cancer, and totalitarianism. When I was a child, I imagined myself a warrior against injustice… Before I was ten, I wanted to fight the Nazis, and when I was a young teenager, I imagined pursuing science so I might cure cancer. In both instances, I had the deep conviction that the Holocaust and its aftermath and the extent and circumstances of cancer were not, as the insurance companies say, “acts of God”, but injustices that should and could be righted.(Metzger [1978] 1997)

Here Metzger articulates her insights on oppression and healing as she recalls the historical trauma of the Holocaust, the systematic extermination of six million Jews during World War II. As an American Jewish woman whose family roots are in the Jewish communities exterminated during the war, she forges connections between the personal and the political and points to a relationship between individual healing and social change.

Metzger’s writings open the door to the phenomenon of social and personal intersections between the Holocaust and illness, particularly cancer, which are expressed by individuals and groups in different, often contradictory, ways. Among the first scholars to identify connections between the two in women’s art were art historians Amelia Jones and Gannit Ankori. Both discussed the art of pioneering Jewish American feminist artist Hannah Wilke (1940–1993), who documented her mother’s struggles with breast cancer and her own struggles with lymphoma. They both point to subtle signs in Wilke’s works that suggest that she examined life and death through the prism of the Holocaust (Jones 1998, pp. 194–95; Ankori 2001). Art historian Griselda Pollock also observed this link in the art of Polish Jewish artist and Holocaust survivor Alina Szapocznikow (Pollock 2013). Neither Ankori, Jones, nor Pollock set out to establish connections between these women’s art and the Holocaust, yet all three identified them. Nonetheless, the intersection of the Holocaust and cancer in women’s art has remained largely unexplored. Art scholars have mainly tackled the two directions separately, with some examining Holocaust and post-Holocaust art by women as individuals or the shared characteristics of their works (see, e.g., Rosenberg 2002; Brutin 2006; Presiado 2016, 2018, 2019; Scheflan-Katzav 2022) and others who explored the art of women following breast cancer (e.g., Rosolowski 2001; Bell 2002; Bolaki 2011; Tanner 2013).

This article focuses on the distinctive perspective of the relationship between cancer and the Holocaust in women’s art. This phenomenon is explored through the works of three artists, all of whom both experienced breast cancer and have or had autobiographical connections to the Holocaust: Holocaust survivor Alina Szapocznikow (1926–1973) and two daughters of Holocaust survivors, Israeli artist Anat Massad (b. 1951) and English artist Lorna Brunstein (b. 1950). It is difficult to determine the prevalence of this phenomenon; nevertheless, it is evident in the works of several female artists, including Hannah Wilke, mentioned above, the Israeli curator and painter Tzipora (Tzipi) Luria (1948–2008), and American artist Mina Cohen (b. 1951). Both are daughters of Holocaust survivors and created art in which the two themes are interwoven following the diagnosis of cancer, in Cohen’s case following her mother’s breast cancer, and in Luria’s following her own illness. Similarly, other Israeli artists such as Rachel Nemesh (born 1951), Devora Morg (b. 1949), and Dvora (Veg) Zelichov (b. 1953) have incorporated the themes of their Holocaust survivor mothers’ old age and physical decline in their Holocaust art.

Having matured during the rise and development of feminist art, these artists turned to the body to treat subjects such as femininity and race. Their artworks are addressed here through an interdisciplinary analysis that integrates history, gender, art, and the discourse on trauma and illness. A discussion of the relationship between cancer and the Holocaust in women’s art requires an examination of three key topics: the social and psychological connections between cancer and the Holocaust, women’s art and the Holocaust, and women’s art as a response to breast cancer.

1.1. Cancer and the Holocaust

The Holocaust is a living trauma in the individual and collective body, a traumatic element that threatens to reawaken at times, for example, when a new illness is diagnosed. The phenomenon in which a new and traumatic experience, such as an illness, triggers memories and even leads to trauma reactivation (the recurrence of traumatic symptoms) is well known. Recent studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic found that among Holocaust survivors and their descendants, the pandemic may have triggered distress from the past and led to intensified responses (Maytles et al. 2021; Shrira and Felsen 2021). Studies also indicate that reactivation is not only an individual phenomenon but also a social one. Recently, communications and social media studies have noted that in post-traumatic Israeli society, Holocaust trauma and associations were reawakened by the COVID-19 pandemic. In the early stages of the pandemic, the media reported on the association between the pandemic and the Holocaust, and when the initial wave of panic subsided, described a tendency to compare COVID-19-related government lockdowns and regulations to Nazi rule (Steir-Livny 2022).

As for cancer, studies have found deep connections between it and Holocaust trauma. It has been shown that Holocaust survivors, especially those who have experienced difficult living conditions, extreme and prolonged hunger, overcrowding, infectious diseases, and mental stress, are more likely than others to get cancer (Sadetzki et al. 2017). Furthermore, the rate of breast cancer is particularly high among Jewish women who spent the war years in Nazi-occupied Europe (Keinan-Boker et al. 2009).1

Psychological studies have also found a connection between cancer patients’ Holocaust experiences and their responses to the disease, with Holocaust survivors expressing greater emotional distress than others and likening the experience of cancer to that of concentration and extermination camps. Both cancer and the Holocaust are associated with fear of pain, disfigurement, disability, loss of control, feelings of social rejection, and helplessness (Baider et al. 1992; Peretz et al. 1994). Follow-up studies have shown that this phenomenon was transmitted to the second-generation survivors of the Holocaust. These are adult children whose identity was shaped by their childhood experiences in the shadow of parents who survived the horrors of the Holocaust (Brutin 2015, pp. 12–18; Milner 2003, pp. 19–28). When second-generation women are faced with traumas such as breast cancer, their reaction can be expressed by extreme psychological distress (Baider et al. 2000).

The connection between cancer and the Holocaust recalls the racist and anti-Semitic identification of Jews with physical and social illnesses, as Susan Sontag showed in her book Illness as Metaphor, written during her breast cancer treatment (Olson 2002, p. 167). Sontag notes that throughout history, societies have used metaphors of incurable diseases to describe social situations and mark or condemn the Other (Sontag 1978). These metaphors reflect the spirit of the times and the character of the culture that uses them.2

Modern totalitarian movements, in particular, have tended to use images of disease to influence the public. Nazi propaganda used historical and contemporary anti-Semitic metaphors and analogies that compared Jews to insects, parasites, spreaders of plagues, and a cancer in the body of the nation. According to Sontag:

The Nazis declared that someone of mixed “racial” origin was like a syphilitic. European Jewry was repeatedly analogized to syphilis, and to a cancer that must be excised… As was said in speeches about “the Jewish problem” throughout the 1930s, to treat a cancer, one must cut out much of the healthy tissue around it. The imagery of cancer for the Nazis prescribes “radical” treatment, in contrast to the “soft” treatment thought appropriate for TB—the difference between sanatoria (that is, exile) and surgery (that is, crematoria).(Sontag 1978, pp. 82–84)

1.2. The Body in Women’s Holocaust Art

Nazism’s attack on the bodies of its victims was radical and characterized by complete and boundless sadism (Goldberg 2013, p. 62). The Nazis did not believe in an ideology, i.e., an abstract, theoretical, and ideational concept, but rather held a worldview, a physical and bodily way of seeing the world (Neumann 2002, pp. 29–30). According to this worldview, the body was a central object towards which Nazism directed itself and the source of its authority (Goldberg 2013, p. 63). The world was experienced and perceived through the body, and Jewish women, as Holocaust scholars have shown, were subject to double suffering as Jews and as women. Jewish women experienced the Holocaust differently because of their physiology, their socialization, and the patriarchal Nazi worldview directed against them (e.g., Katz and Ringelheim 1983; Ringelheim 1983; Bridenthal et al. 1984; Heinemann 1986; Koonz 1987; Goldenberg 1990; Ofer and Weitzman 1998; Baumel-Schwartz 1998; Baer and Goldenberg 2003; Hertzog 2008; Shik 2010; Hedgepeth and Saidel 2010). Moreover, gender shaped the ways in which women remembered and recounted their experiences (Bos 2003).

Studies of survivors’ testimonies indicate that both men and women were immersed in the deterioration and destruction of their bodies during the Holocaust and lived in fear of their practical implications, that is, death. In women’s memories, an additional dimension of how this physical reality affected them as women, i.e., the loss of femininity and fertility, emerged (Shik 2010, pp. 175–76). In women’s stories, particular attention is also given to the shaving of their heads in the camps, as in patriarchal culture, women (and men) are socialized to perceive women’s beauty as a value (Wolf 2002), and hair is considered one of the most prominent signs of beauty, femininity, and sexuality. Its loss was associated in women’s testimonies with humiliation and the loss of a sense of identity; the loss of hair and beauty was a traumatic experience for women in the Holocaust.

During the Holocaust, in the art that women created in the ghettos and concentration and death camps, and immediately afterward, the experiences of suffering and trauma are intensely and realistically represented through the portrayal of the female body’s destruction. These depictions include images of bodies enduring abuse, experiencing pain, being shaved and mutilated, and gradually wasting away (Presiado 2016). The representations of the body reflected the physical trauma and emotional and mental struggles they experienced, communicating the inner turmoil of the artists. At the same time, such images allowed these women to process and document the horrors they faced while narrating individual and collective experiences. Through their art, they attempted to come to terms with the changes in their bodies and minds and to find a sense of agency in a world in which their autonomy was stripped away; by doing so, they asserted their identities, humanity, and connections with others (Hlavek 2022).

In later works of women survivors, from the 1950s onwards, a process of exclusion of these brutal physical images is evident. Their gradual disappearance is related to the return to “normal life” and the old societal gender order, as well as how society perceived the survivors and reacted to their stories and art. The change also arose from consideration—conscious or unconscious—for family members and public opinion.

Beginning in the late 1960s, and more prominently from the 1980s and 1990s, many Jewish artists returned to the body in their artworks about the Holocaust. Prominent among these artists were daughters of survivors who belonged to what Marianne Hirsch termed the generation of postmemory (Hirsch 1997). Their engagement with the Holocaust is a combination of collective memory, personal trauma inherited from their survivor parents, and their own life experiences as children of survivors. Their choice to place the female body at the center of their works stemmed from the far-reaching influence of feminist art that emerged in the late 1960s and 1970s, transforming the female body into an artistic field and primary focus. Feminist artists believed that the woman’s body was the central site from which knowledge about the female experience could be drawn, as well as the source of inner forces that could liberate women from patriarchal oppression. They created oppositions to the male gaze and the ways in which men had sexualized and controlled women’s bodies, working from within the female body to address the bodily experiences of women, who had frequently been excluded from the social discourse (see, e.g., Lippard 1976; Tickner 1978; Frueh 1994; Liss 1994; Betterton 1996; Jones 1998; Battista 2013; Dekel 2011). The representations in these artworks reveal a deep connection between the artists’ inherited trauma and their explorations of the female body.

The idea that the body is the center of the psychic experience is evident in Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology, which views subjects as inseparable from their experiences, with the body and sensory impressions serving as the tools that enable these experiences (Merleau-Ponty 1962). This understanding of the connection between human beings’ physical and mental aspects is further developed in the notion of embodiment, according to which consciousness is deeply anchored in the body and where the body and soul must be viewed as a single unit. Trauma is known to be significantly mediated through the body and manifested in embodied experiences (see, e.g., Scaer 2005; Johnson 2008). In the works of these women that relate to the Holocaust, the body conveys the story of trauma. The body serves not as a metaphor but rather as an archive of past physical experiences that affect emotions in the present.

1.3. The Body in Breast Cancer Art

Stories of illness are also told through the body. In his book, The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness, and Ethics, Arthur W. Frank suggests that the stories are told through the wounded body that carries the illness or is recovering from it. The body is the source and subject of these stories and the instrument through which they are told. These personal stories also have social aspects; first, storytellers pass their stories on, and second, they address the narrative conventions and social expectations regarding the stories of illness (Frank 1995, pp. 2–3).

Breast cancer is treated by manipulating the body; coping with the disease and its consequences destabilizes both body and mind. Although the same is true for many diseases, for women, breast cancer may provoke a more emotional and gender-related concern following the changes that the body undergoes compared to other cancers, as the breast is an intimate organ associated with issues of body image, femininity, motherhood, and sexuality (Young 2005, pp. 75–96). Women who tell stories of breast cancer do so against the background of the dominant social discourses regarding the disease. The medical discourse perceives the body as an object and dichotomizes illness and health, while the social–gender discourse objectifies the female body and focuses on women’s outward appearance, grooming, and their control of behavior and emotion as it relates to illness, as an opportunity for personal and professional transformation (Zion-Mozes et al. 2022). Feminist researchers claim that these discourses deny the limitations of the body—the pain and suffering—and the complications involved in coping with the disease—the treatments and the procedures of mastectomy and reconstruction. They point to the gap between physical reality and the social–medical rhetoric that positions health and beauty as an ideal (Zion-Mozes et al. 2022).

When the feminist critical discourse developed in the 1960s and 1970s, with the rise of feminism and the women’s health movement, cancer narratives written by women began to challenge dominant cultural discourses. In visual art in the 1970s and 1980s, women artists also began to represent their struggles with breast cancer and their changing bodies (DeShazer and Helle 2013, p. 7) as they challenged conventional representations of femininity.

Among the most well-known examples of such artists are Hannah Wilke, mentioned above; English photographer Jo Spence (1934–1992), who had breast cancer in the 1980s and photographed her body after her mastectomy at various stages of the disease until her death; and the American artist, model, and journalist Joanne Matuschka (b. 1954), who was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1991, underwent a mastectomy, and was photographed following the surgery in different poses. Among the photographs of Matuschka was one that depicted her as an Amazon in a dress cut away from one shoulder that emphasized her mastectomy scar. Spence and Matuschka presented viewers with the ill, changing, pained, and imperfect body, conveying political messages that subverted the conventions and patterns of representation of the perfect female body and its visibility in the public sphere while offering a different, unpopular alternative to the representation of femininity. Art historian Ruth Markus and curator Ruthi Chinski-Amitai suggest that for women artists, the act of documenting the stages of illness and radical changes in the body may provide a sense of control over the situation and allow them to reappropriate their bodies by making it possible to observe and approach them as not necessarily defective and deformed, as is common in our culture, but simply as changed (Marcus and Chinski-Amitai 2020).

The artworks of Szapocznikow, Massad, and Brunstein examined in this article reflect the double vulnerability of the trauma of the Holocaust and ill female bodies. In them, the body functions far beyond its material representation. It is the authority through which memory and emotional experience are transmitted, trauma is processed, and through which individual voices that are also political are heard.

2. Trauma and the Memory of Trauma Etched into the Female Body

2.1. Alina Szapocznikow—Trauma

“I am convinced that of all the manifestations of the ephemeral, the human body is the most vulnerable, the only source of all joy, all suffering and all truth, because of its essential nudity, as inevitable as it is inadmissible on any conscious level” (Szapocznikow et al. 2011, p. 28). These words were written by Alina Szapocznikow in 1972, a year before her death. Today, she is known as one of the most important sculptors active in Europe after World War II and a harbinger of feminist art. She placed the female body image at the center of her works and used innovative materials such as polyurethane, polyester resin, chewing gum, and nylon.

Szapocznikow was born in Poland in 1926 to parents who were both physicians. When she was twelve, her father died of tuberculosis. A year later, in 1939, she was imprisoned with her mother and brother in the Fabianica ghetto. After the ghetto’s liquidation, the three were transferred to the Lodz ghetto, then to Auschwitz-Birkenau, and from there to Bergen-Belsen and the Terezin ghetto, from which she was liberated. During the years in the camps and ghettos, she worked as a nurse alongside her mother until they were separated in the fall of 1944 (Pollock 2013, pp. 188–89, 192; Feldmann 2014, pp. 117–20). After the war ended, convinced that all her family members had perished, she went to Prague, where she found her mother and began working as a sculptor. Later, she established her career in Poland and France, and in 1963 moved permanently to Paris, where she rose in avant-garde circles. She was barren as a result of contracting tuberculosis in 1949, and she and her husband eventually adopted a son. In 1961, her mother died of lung cancer, and in 1969, Szapocznikow fell ill with breast cancer. The massive physical and mental traumas she experienced emerged in her works, in which she focused on her body.

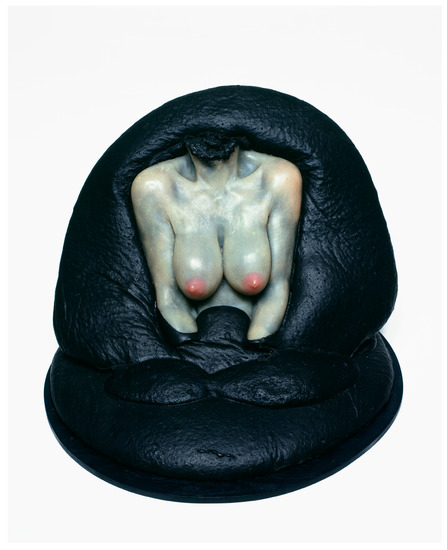

In the sculpture Headless Torso (Figure 2), which Szapocznikow created before her breast cancer diagnosis, a naked, realistic female body sinks into a viscous mass. The head and lower part of the body are engulfed in black material, and the encounter with the work evokes associations of suffocation, sinking, decay, and death. The feeling that emerges from the work is traumatic. Griselda Pollock recognizes that Szapocznikow’s work changed over the years, from being solid and full, with images of a complete and presentable body, to something fluid, amorphous, and disintegrated. This kind of representation of the body, according to Pollock, signifies an encryption of the trauma of the Holocaust, a delayed creative material expression of her experiences in the concentration and extermination camps, about which she rarely wrote or spoke (Pollock 2013). Precisely because of the continued silence, the trauma had to ultimately present itself through traces encrypted in the flesh.

Figure 2.

Alina Szapocznikow, Headless Torso, 1968, polyester resin and polyurethane foam, 46 × 64 × 73 cm, Zachęta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw © ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy of The Estate of Alina Szapocznikow/Piotr Stanislawski/Galerie Loevenbruck, Paris/Hauser & Wirth.

After the Holocaust, it became clear to many survivors that no language would allow them to express the reality they had experienced. In Auschwitz, every possibility of narrative thinking was undone (Spiegel 2007, p. 12). Scholars have written about the impossibility of Holocaust victims expressing themselves in language. Historian Boaz Neumann describes the language of the victim as a language incapable of expression (see, e.g., Felman and Laub 1992; Neumann 2002, p. 247). In a similar vein, Pierre Restany, French art critic and formulator of the New Realism, describes how in the absence of verbal language with which to talk about the Holocaust, Szapocznikow expressed herself in a language that came from within the body: “Her work was to be but one long scream of revolt against the genocide of the flesh and ineluctable calamity of evil” (Restany 1973, cited in Pollock 2013, p. 206).

Trauma is an event or a series of violent, unusual, and difficult-to-process events that leaves an indelible mark on the mind. When trauma occurs, mental and physical defense mechanisms cease to function, and intense feelings of terror, fear of death, and loss arise. Traumatic events trigger a wide range of physical and emotional symptoms and leave victims with an experience of detachment and interruption, undermining the foundations of existence and stable, familiar identity. The Holocaust was and remains a massive, ongoing trauma. Concentration camp survivors report acute invasive post-traumatic symptoms many decades after the events.

Traumatic memory is characterized by the disruption of time. Often victims of trauma re-experience the events in flashbacks and nightmares (Herman 1992). Freud called the repeated intrusion of memories of traumatic experience “the compulsion to repeat” (Freud [1914] 1958). The repetitiveness and intrusiveness of the memories turn the trauma into an experience that disrupts the distinction between the here and now and the “then and there” (Goldberg 2006, p. 15). At the same time, traumatic memory is characterized by absences and gaps that cannot be filled in, and the trauma always remains unconceptualized, a black hole of memory and forgetting (Herman 1992), an event that cannot be fully represented (Rothberg 2000, p. 157). In Szapocznikow’s works, she repeatedly created disintegrated bodies that suggest this fragmentation of memory.

Szapocznikow experienced her trauma through the flesh, and her memory was sealed in the body. French writer Charlotte Delbo describes exactly this kind of memory in her chilling memoirs of her imprisonment in Auschwitz-Birkenau and defines the memory of the camp as deep memory. This is a different type of memory, which comes from the body and is distinct from ordinary or common memory. It is a sensory memory that records the internal experience of the trauma. For Delbo, this is precisely the most valuable memory because it resists historicization and holds within it the emotion and feelings evoked by the experience itself (Langer 1993, pp. 6–9; Delbo [1985] 2001, p. 47). The experiences in the camp were sensory and included sights, smells, physical sensations, pain, hunger and thirst, disgust, fear, and terror. Delbo uses the term skin to describe the perpetuity of the effects of the camp’s trauma in bodily terms: “Auschwitz is there, unalterable, precise, but enveloped in the skin of memory, an impermeable skin that isolates it from my present self” (Delbo [1985] 2001, p. 47).

Similarly, in Headless Torso, Szapocznikow wrapped herself in a layer of material that simulated skin, touching the body and evoking an emotional response in viewers. The emotional responses of viewers of a work of art result from a sensory encounter, as scholar Jill Bennett explains through the concept of affect. Affect refers to the activation of the experience of sensory and internal emotional responses to the visual-material intensity of an artwork (O’Sullivan 2001): “the affective responses engendered by artworks are not born of emotional identification or sympathy; rather they emerge from a direct engagement with sensation as it is registered in the work” (Bennett 2005, p. 7). The sensory encounter of viewers with Szapocznikow’s artworks is created by contact with the representation that simulates human flesh and bare skin (Kulasekara 2017, pp. 41–42).

Restany notes that Szapocznikow’s rebellion against the genocide of the flesh became a prophetic vision that ended in the disease that killed her at age 47 (Pollock 2013, p. 206). Unfortunately, the Holocaust became a kind of marker that determined the direction of the remainder of her life, coloring everything and becoming an integral part of the body itself.

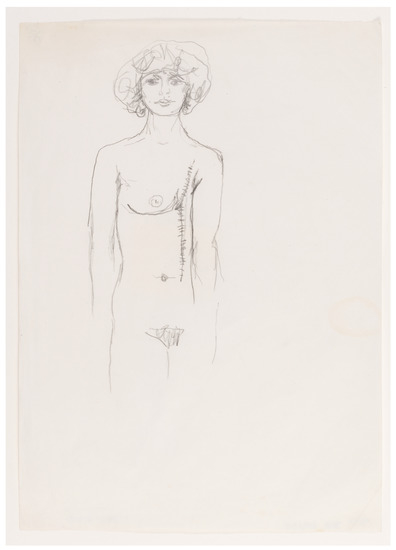

From the moment she fell ill until she died, Szapocznikow underwent many medical procedures and invasive surgeries. In one of her self-portraits, she depicted her body after a mastectomy (Figure 3). In it, she stands naked, gazing fiercely at the viewer. Her mastectomy scar stretches from her shoulder to her navel, and the breast that remains takes up almost her entire chest.

Figure 3.

Alina Szapocznikow, Untitled, v. 1971–1972, pencil on copying paper, 29.5 × 21 cm. © ADAGP, Paris. © ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy of The Estate of Alina Szapocznikow/Piotr Stanislawski/Galerie Loevenbruck, Paris/Hauser & Wirth.

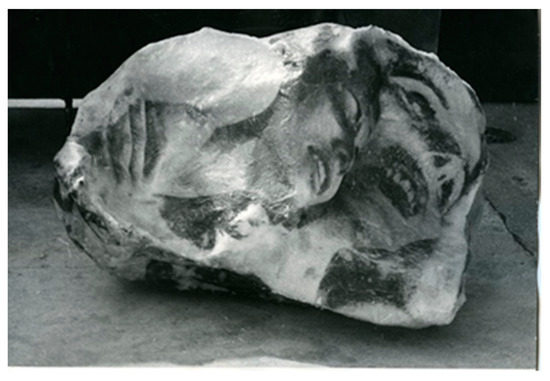

In other works, Szapocznikow’s experiences of cancer and the Holocaust are interwoven. One of these is Grand Tumor I (Figure 4), from the Tumor Series.

Figure 4.

Alina Szapocznikow, Grand Tumor I, 1969, polyester, photographs, 73 × 93 × 97 cm. © ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy of The Estate of Alina Szapocznikow/Piotr Stanislawski/Galerie Loevenbruck, Paris/Hauser & Wirth.

This work simulates a kind of tumor in a strange and amorphous way, with two photographs of women superimposed onto it. The first is an enlarged photograph of a dead woman’s head that was apparently taken in Majdanek or Auschwitz (Pollock 2013, p. 212). The woman’s head is a detail from a photograph in which she is shown lying naked among a tangle of emaciated corpses. This photograph is placed next to one showing the face of the actress Emmanuelle Riva from the 1959 film Hiroshima Mon Amour, directed by Alain Resnais. The film, based on the novel of the same name by Marguerite Duras, is replete with images of sexuality and disaster and tells the story of a French actress taking part in the shooting of a film in Hiroshima fourteen years after the Americans dropped the atomic bomb. It includes documentary footage, and the opening scene shows the effects of the bombing on the city, the injured people who survived, and the scarred heads of women who lost their hair. By placing the dead woman from the concentration camp and the actress side by side on the tumor statue, Szapocznikow linked the suffering of her illness, the suffering of the camps, and the horrors of World War II. This sculpture seems to reveal the two worlds Szapocznikow occupied at the time: “the kingdom of the sick,” a term coined by Sontag (Sontag 1978, p. 3), and the “other planet,” a term invented by writer and Holocaust survivor Yehiel Dinur, known by his literary name Ka-Tzetnik, to refer to Auschwitz (Records of the Eichmann Trial 1961, Session 68, p. 1034).

Just as the Holocaust left its victims with no language, some cancer stories also express the loss of the possibility of articulating the illness with words. Arthur Frank calls these narratives of chaos. They emerge when people are overwhelmed by the intensity of their illnesses, and there is no hope of returning to normal. Frank asserts that “[s]eriously ill people are wounded not just in body but in voice” and compares chaos narratives to the narratives that emerge from the stories of Holocaust survivors (Frank 1995, p. xii). These are disjointed, repetitive narratives characterized by disturbances of time and memory, descriptions of physical pain, lack of control, and absence (Frank 1995, pp. 97–114).

The disease is one of the means by which to voice the memory of the Holocaust and transmit it to future generations. The body speaks covertly, in a way that culture cannot control, as literary scholar Talila Kosh Zohar explains, and the disease of the female survivor’s body serves as a language through which memory is transmitted (Kosh Zohar 2013, p. 275). In the installation Tumors Personified (Figure 5), Szapocznikow’s face is cast onto a large number of tumors scattered over a surface that resembles bare soil. It seems that the faces are growing out of the tumors or that the tumors are enveloping and digesting them. The fragmentation evokes a feeling of suffering, and the humanized tumors are reproduced and spread over the earthy surface like metastases multiplying uncontrollably and spreading through a body. At the same time, they recall the appearance of a mass grave, which evokes not only the artist’s death but also mass death, the extermination of a people.

Figure 5.

Alina Szapocznikow, Tumors Personified, 1971, polyester resin, fiberglass, paper, gauze, various dimensions, Zachęta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw. © ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy of The Estate of Alina Szapocznikow/Piotr Stanislawski/Galerie Loevenbruck, Paris/Hauser & Wirth.

In Alina’s Funeral (Figure 6), Szapocznikow predicted her own death and described herself as an accumulation of materials stuck together to create a kind of corpse. She is not human, but a sticky, bubbling mass from which we see more anthropomorphized tumors emerging. This image is reminiscent of the photographs that documented the mass graves of humans with their organs tangled together that were discovered during the liberation of the concentration and extermination camps.

Figure 6.

Alina Szapocznikow, Alina’s Funeral, 1970, polyester resin, glass wool, photographs, wood, gauze, artist’s clothing, 135 × 210 × 50 cm. Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie. © ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy of The Estate of Alina Szapocznikow/Piotr Stanislawski/Galerie Loevenbruck, Paris/Hauser & Wirt.

As she approached the end of life, the artist compared her death to the anonymous, broken deaths of those who perished in the Holocaust. The Holocaust remains written on the body. Szapocznikow survived the Holocaust and became ill with cancer. Ultimately, she was overcome by the disease, which was deeply rooted in the physical trauma she experienced.

2.2. Anat Massad and Lorna Brunstein—A Memory of a Trauma

The memory of the trauma of the Holocaust is powerfully written on the body in the works of daughters of Holocaust survivors and interwoven with the struggle with breast cancer. Children of survivors are often identified in research and culture with the concept of the second generation. Some parents shared their experiences with their children and family members in detail, and some repeated the same stories obsessively, while others remained silent. Whether they spoke or remained silent, the Holocaust permeated the lives of their families through conscious and subconscious channels (Wardi 1992; Bar-On 1995). Psychoanalyst, Yolanda Gampel, uses the images of an atomic bomb and radioactive fallout to explain the transmission of violent and destructive traumatic elements saturated with anxiety by survivors to their children (Gampel 2021, p. 67).

Since the late 1970s, second-generation artists have been telling their stories through their works (Hirsch 1997; Young 2000; Apel 2002; Van Alphen 2006; Brutin 2015). Daughters of survivors are simultaneously positioned in the world of their inherited trauma and the collective memory of the Holocaust and integrate them into their art. Their experience of coping with this situation creates a unique rhetoric that contains, on the one hand, shared memory—the social construction of what and how society remembers the past—and on the other, the trauma—the personal experience of inaccessible or partially accessible traumatic memories transmitted by the survivor generation, and the lived experience of deep emotional identification with their parents.

Historically, the art of the daughters of the second generation developed alongside the maturation of feminist ideas, allowing their unique memory of the Holocaust to merge into feminist historical memory. The trauma and the memory are expressed in feminist artistic language. As daughters of survivors, they tell their parents’ stories, especially their mothers’, often using their bodies and selves to do so.

Second-generation Israeli artist Anat Massad is the daughter of Holocaust survivor parents whose entire families perished in the war. Her mother was a prisoner in the concentration camps of Płaszów and Auschwitz. Her father fled from Lodz to the Soviet Union and spent the war wandering and working in labor camps. Massad’s parents did not often talk to her about their experiences, but the Holocaust and the deaths of family members were a constant and silent presence (Massad 2009; Brutin 2015, p. 61). “The Holocaust,” Massad says, “was always at home for me, not for them. I mean, this is my inner world, although it is not something that is talked about…” (Massad 2009).

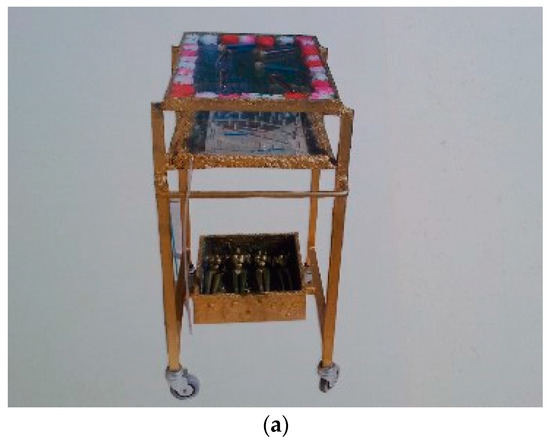

In 1993, Massad was diagnosed with breast cancer. About a year later, she created a sculpture—a wheeled cart with shelves painted in gold (Figure 7a). The upper shelf in the cart is cast in oil, and colorful silk flowers are pressed into it (Figure 7b). On it are four test tubes. One is filled with a bluish liquid reminiscent of antiseptic or liquid medicine, and the others are filled with the artist’s hair and the hair of other women collected by her. The middle shelf is wrapped in foil, and on it are glued plastic tubes of the kind used for IV drug administration. On the bottom shelf lie four decapitated Barbie dolls covered in gold in a box, as if in a mass grave (Figure 7c).

Figure 7.

(a) Anat Massad, Untitled, 1994, hair, test tubes, and mixed technique, 90 × 50 × 43 cm, the artist’s collection (above); (b) Detail (bottom right); (c) Detail (bottom left). Courtesy of Anat Massad.

The multiple dolls and their decapitation creates a sense of incompleteness and violence, emphasizing their anonymity and physical injury. Massad says that the impetus for the creation of fragmented figures was her imagining of the appearance of her mother, who was liberated from the camps in a state of extreme malnutrition: “She was skin and bones. When we visited Auschwitz and saw pictures on display, she would come back and say, ‘You see, that’s how I was.’ I think she weighed fifteen kilos. A skeleton that was still breathing a little” (Massad 2010). The experience of the body during the Holocaust, and, in particular, of the bodies of her mother and the murdered aunts and grandmothers she never knew, preoccupies Massad. The photographs of the Holocaust that appeared in the many books her father purchased over the years also had a huge impact on her visual memory (Massad 2010; Brutin 2015, p. 61). Massad says that, even as a child, these albums intrigued her, and she would peruse their pages again and again. Since her father’s death, these books have been on a shelf in her studio. She told me the following:

There are these famous pictures of the Allies who arrived at the camps with shovels and are pushing the bodies into the pits…. The realization that the mass being pushed by a shovel is actually a mass of real people [is shocking]. You don’t think at all that these are real people… In the camps, the damage to the body was total. In the camps, millions were harmed. But among those millions, there is one person whose body this is… People came to the trains; they were crammed in; people had to eat; people had to go to the bathroom; people contracted diseases… and in the end, they also burned them. There was such a preoccupation with the body itself. What else can we invent to free us from this body? For me, this is quite a story. The extermination of the entire Jewish people does not speak to me in the way that this story speaks to me. How do you lead the body, isolate it, starve it, work it hard, sicken it, kill it, cut it, tattoo it, how many operations were carried out at the procedural level until we finally got rid of this body?… The destruction of the body, not the destruction of the people—this is the story here in my opinion.(Massad 2010)

By dismantling the Barbie dolls, Massad was attempting to understand the unbearable vulnerability of the body: “In my view of the world, only the victims of the Holocaust exist… I describe them and emphasize the physical harm they experienced by depicting severed limbs… in one second, the body is dismantled. The head is separated from the shoulders. Completely amputated” (Massad 2009).

The wheeled cart, reminiscent of a hospital cart, recalls Massad’s experience with illness, as do the test tubes with the hair and liquid and IV tubes coming out of the middle shelf. The transparent shelves reveal a view of all the components of the cart from top to bottom. Below are the decapitated dolls; above them, catheters and medical test tubes; and above these are flowers, which lend the work the appearance of a grave or monument constructed from layers of memory and experience that have merged into one another. Massad tells of a conscious process that began with the memory of the Holocaust and was later integrated into the experience of illness:

The motivation is the vulnerability of the body. After I understood the vulnerability of the body, I got cancer. This is the story. This is the right order. After asking myself for years what else can be done to the body and how else it can be harmed, I too am ill. I was thinking about the vulnerability of the body, and it doesn’t matter if it comes from experiments on the body during the Holocaust or from an illness that attacks you, or if it just comes from the passing of the years and the body gradually deteriorating.(Massad 2009)

Barbie dolls have represented an unattainable, unrealistic model of a young body and perfect female beauty for generations of girls. Massad’s decapitation of the dolls hints at the painful and dangerous results for women of expectations of beauty and bodily perfection and the exclusion of the aging and diseased body from cultural production. Massad thought a great deal about how her mother’s experience during the Holocaust as a young and beautiful woman was related to the abuse she suffered in the camps: “I asked her if there was any abuse by other female prisoners, by the capo. She said that there hadn’t been… Do I believe it? I don’t know. She said no… What happened to my mother’s body? I really wanted to know if, in addition to all these horrors, she also underwent some kind of rape…” (Massad 2009).

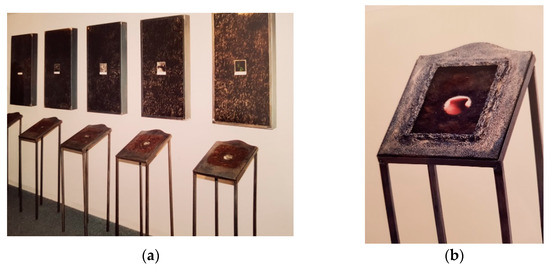

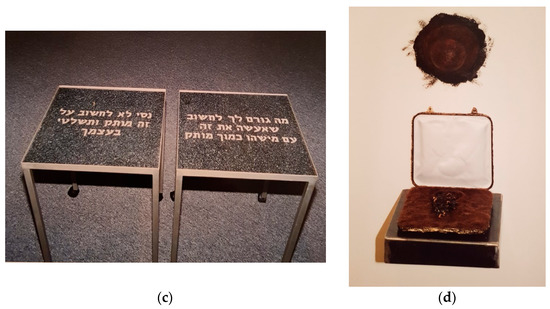

In 1996, Massad continued to develop this theme in the multi-piece installation, For the Purpose of the Plot (Figure 8a–d). The installation, a kind of memory puzzle (Gonen 1996), included collages hung on a wall and iron podiums on which were placed a board with a photograph Massad took of the inside of her body or a text surrounded by hair (Figure 8a,b), several carts on wheels holding marble slabs with engraved texts reminiscent of tombstones in a Jewish cemetery (Figure 8c), and scraps of paper on which were drawn random images such as an axe, a shoe, a fish, a body, and a suitcase. In addition, there was a jewelry box containing a small statue simulating an unidentified body part, and above it, a round rug with hair glued onto it (Figure 8d).

Figure 8.

(a) Anat Massad, For the Sake of the Plot, detail, 1996. Mixed media: iron, hair, text. The artist’s collection, Kfar Masaryk. Detail (left); (b) Detail (middle); (c) Detail (left); (d) Detail (right). Courtesy of Anat Massad.

The hair, one of the most prominent elements in the work, is charged with contradictory meanings—on the one hand, connotations of feminine beauty and sexuality and, on the other, the heaviness of violence and death. Before preparing the installation, Massad collected hair from a barber shop, sorted it by color, and scattered and cut it to imitate the disciplinary actions of the Germans. “The hair… the matter of collecting the hair, is an action that is very much identified with the Holocaust and collective memory,” Massad explained, “I was taking myself back to an action that I wanted to understand or identify with or feel how it felt” (Massad 2010). This was Massad’s attempt to understand or rebel against the Germans’ coercive control over all aspects of their victims’ bodies. Here, too, the separate body parts carry personal meanings related to Massad’s illness. Massad did not lose her hair because of chemotherapy treatments, but she wanted to convey the sense of fear of the unknown: “When you are sick, you are constantly afraid” (Massad 2009).

On the marble slabs and iron podiums are written sentences such as: “You need pleasure”, “Try not to think about it honey and control yourself”, and “I tried to control myself sweetie I can’t be what I’m not (sweetie)”. These sentences evoke intimate exchanges between lovers. On one of the carts, hair is glued around the question: “Where is the cradle of your desire?”. Above the text, a circle is embroidered in red thread. This combination brings to mind female genitalia, sexuality, and fertility, and, at the same time, the lines written on the marble slabs reminiscent of tombstones hint at aggression and violence, while the red color and the separation of the hair from the body evoke a sense of injury and death.

Massad creates a collection of images that are intended to tell a story, as the work’s title, For the Purpose of the Plot, implies. But the plot remains disjointed, consisting of fragments of sentences and isolated images, some of them unidentified. This story is attempting to be told from her mother’s silence, from Massad’s internal discourse as a daughter of her survivor mother, and from the story of her illness. Massad creates a unique language with which she recounts the injury and memory of the body.

A later embodiment of the intersection between the Holocaust and cancer is found in the art of Lorna Brunstein. Both of Brunstein’s parents were Holocaust survivors. Her mother, born in Lodz, Poland, was sent by the Nazis to Auschwitz-Birkenau aged sixteen. Her father was born in Warsaw. At the beginning of the Nazi occupation, he fled from Poland to the Soviet Union, where he was sent to a prison and labor camp in Siberia. The artist’s parents lost their entire families in the Holocaust and went to England after the war. There they married and had two daughters, Lorna and her sister. According to Brunstein, her childhood was steeped in the Holocaust:

They were very damaged people obviously because of what happened to them. They loved us very much, the Holocaust was always there in the house, it was just present everywhere, and they were very protective, my father especially so... he didn’t speak much about his experience… but he painted… the house was my father’s gallery. It was covered with paintings depicting pre-war Jewish life in Warsaw and the horrors of his experiences during prison and leaving his parents, whom he never saw again. It was overwhelming… for him the room, the house was his sanctuary, but for me it was becoming like my prison.(Brunstein and O’Brien 2021)

Brunstein has been involved in art since the 1970s. For a long time, she avoided addressing the subject of the Holocaust, and it only arose for the first time late in her life, following a trip she took with her parents and sister, in 1998, to Poland to trace their family history. In 2001, while researching the first major exhibition on her mother’s past, Brunstein was diagnosed with breast cancer. The artist draws a connection between the events:

I was looking at these faces of my grandmother, of my aunt, looking and trying to connect, find a way in, and I got diagnosed, and I was so immersed in it, reading history, all I [could] think of when heard I [had gotten] breast cancer [was] God saying (not that I am religious): “Do you really want to do this?” I felt that I was scratching something and the result of that was breast cancer.(Brunstein 2022)

During the cancer treatments, Brunstein began to collect materials for a future artwork. In 2006, when four years had passed since the end of the treatments, she was able to engage in reflection and create a work on the period of the treatments while linking the cancer experience to the Holocaust trauma she had inherited: “The Holocaust was always there... it was in my Mom’s milk. She fed me, and so thinking about cancer... I always say it was in Mom’s milk” (Brunstein 2022).

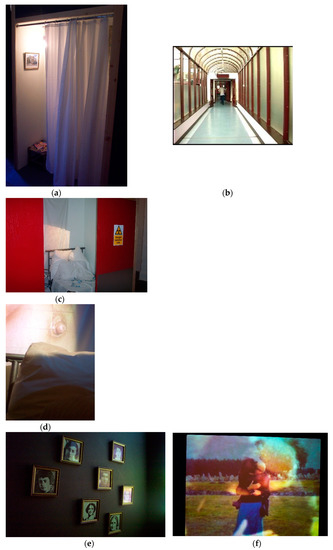

The work that she created, So How Come I Got It Then? (Figure 9a–f) is an installation containing three booths. The first booth, “The Journey,” consists of two small rooms—a doctor’s waiting room with a small table with magazines on it (Figure 9a) that leads to the second room (Figure 9b), where a film Brunstein shot while sitting in a wheelchair is projected. The film describes the winding path through the hospital from the multi-story parking lot to the red doors of the radiotherapy room. The film ends as the doors open and the radiotherapy room is seen from inside, then begins again. This is the path that Brunstein took, back and forth, every day for the six weeks of her treatments. In the background, the romantic song Fly Me to The Moon, which she heard during the treatments, is playing.

Figure 9.

(a) Lorna Brunstein, How Come I Got It Then? 2006. Installation, Walcot Chapel, Bath. Detail of the “Waiting Room” in Booth 1, “The Journey” (left); (b) Detail of a video in Booth 1, “The Journey” (right). Courtesy of Lorna Brunstein; (c) Detail of Booth 2, “The Red Doors” (left); (d) Detail of a video in Booth 2, “The Red Doors” (right); (e) Detail of Booth 3, “Farewell” (left); (f) Detail of a video in Booth 3, “Farewell” (right).

The second booth, “The Red Doors” (Figure 9c), simulates a radiotherapy treatment suite. At the entrance to the booth are the two red doors mentioned above. Inside is a hospital bed on which are strewn empty wrappers of the tamoxifen pills that Brunstein took for five years to prevent the disease from returning. On the wall and the back of the bed, zooming in and out, is a video of the artist’s radiotherapy treatments and her breast with her fresh lumpectomy scar (Figure 9d). The irritating sounds of the radiotherapy device are heard in the background. Brunstein says that she wanted to convey the anxiety that accompanied the radiation treatments and which was magnified as a result of the existential fear she inherited from her survivor parents:

It didn’t hurt. But you are lying on this bed, they all go out… because it is dangerous… and you are put on a bed, so you can’t touch the floor, so you have no anchor, no roots, and I am in a middle of a room with no one else, and it doesn’t hurt, but what was going on in my head, it was a panic, a sheer panic, and that is what I feel is my inherited trauma.(Brunstein 2022)

At the entrance to the third booth, “Farewell,” (Figure 9e,f) torn sacks hang and sand is scattered. These materials are associated with death and mourning. Above the entrance to the booth is an LED screen with running red text of the type used in train stations that states: “There is no cancer in our family,” and below, on the floor, another screen with running text that asks, “So how come I got it then?” The two sentences are part of an imaginary dialogue that the artist had with her late father based on a sentence that is etched into her brain. When Brunstein was twenty years old, her mother discovered a breast lump and was hospitalized for about two weeks. The lump was eventually found to be benign, and Brunstein’s father brought her mother home. The artist recalled, “I remember, so clearly, they came through the door, he was standing behind her, and he looked at me. He had a triumphant smile on his face, and he pointed and said: “there is no cancer in this family”; [he] was saying… we have been through enough, and the divine or moral justice… whatever else happened to us, this family will not get cancer” (Brunstein 2022). In the “Farewell” booth, Brunstein confronts her father over the broken promise. Even the most brutal past cannot protect the family from future disasters.

On one of the walls of the booth are pictures of women from the artist’s family who were murdered in the Holocaust that she enlarged from several surviving family photos. The women look relatively young (Figure 9e).

Brunstein assembled for herself a lineage of the women of the family who were simultaneously absent from and present in her life. The photographs raise questions about the unforeseen long-term consequences of extermination. After the news of her diagnosis, she was asked by the doctor if there had been cancer in previous generations of her family, in her grandmothers or aunts, and she answered that she did not know because her parents were Holocaust survivors and all the women in the family had been murdered when they were still relatively young, so there was no one left to ask. This conversation with the doctor was a defining moment in which she experienced a new kind of recognition: “This is what it is about… total annihilation. I have no knowledge. I don’t know” (Brunstein 2022). A woman’s medical history is one of the most important tools in addressing breast cancer treatment and prevention. For women whose families were annihilated and who have no knowledge of their medical histories beyond one generation, many questions remain open (Sharsheret 2010).

The last detail in the third booth is a video, zooming in and out, of the artist and her late father embracing against the background of the tombstones at the memorial site at Treblinka (Figure 9f). In the background, her father can be heard speaking gibberish and a mixture of Polish and Yiddish, and the sounds of doors, wind, and a train bring to mind the transport of Jews to the extermination camps to the east. The photo was taken by Brunstein’s sister during the family trip to Poland. Brunstein’s father had not wanted to return to Poland. For him, Poland was one huge graveyard, but when they reached the memorial site at Treblinka, the extermination camp where his parents were apparently murdered, he collapsed and sobbed. At this moment, Brunstein understood. as if for the first time, her father’s trauma and his attitude towards her as a child and teenager, in a home that was permeated with the Holocaust:

This moment of him hugging me when he broke down, we connected, and I felt there was some unspoken dialogue… he wore his heart on his sleeve… he was highly strung, very anxious. He was so overprotective, he would have died for me and my sister… he was wonderful, lovely, but it was suffocating. And I knew sometimes I was short with him, I could get angry, and all of this in a way of saying “I’m sorry… I forgive you, I know you didn’t mean any harm.”(Brunstein 2022)

Brunstein’s work can be categorized as what Frank calls cancer stories that are quest narratives. In narratives of this type, the disease becomes a journey that becomes a search. The object of the search may be unknown, but there is something to be learned from the experience. The quest narrative gives sick people voices as the protagonists of their stories. In these stories, sick individuals offer insights that the disease has brought into their lives and should be passed on to others (Frank 1995, pp. 115–35). Brunstein created a work of mourning and the working through of trauma. Her illness allowed her to address the painful memories of the family’s past and her lost childhood. Her dialogue with her late father and attempts to understand and come to terms with the past were both parts of the healing process. Her embrace with her father against the background of the tombstones of the Treblinka memorial site comprised a declaration of love and connection in the face of the horror of the Holocaust and life’s hardships.

3. Conclusions

In France and later in Israel and England, at a distance of decades from each other, three artists, Szapocznikow, Massad, and Brunstein, immersed themselves in the intimate work of the ill body to engage with their knowledge of the Holocaust. Szapocznikow, a survivor, simulated skin and flesh to represent disease and described her eventual death as a collection of tumors in a mass grave. Massad and Brunstein, second-generation daughters, connected their illnesses to their family histories. Massad photographs disassembled Barbie dolls and internal organs and obsessed over hair. Brunstein reconstructed her family’s female lineage of murdered women, imagined her genetic history, and captured images of her scarred breast during radiotherapy treatment.

These artists reveal how hidden knowledge is transmitted across generations and emphasize the visual, situational, and emotional connections between events. Moreover, they highlight the societal discourse that links humans and diseases that harm not only those affected by the Holocaust but others as well. The current exploration of these artworks could lead to the investigation of how the intersection of race, historical trauma, and cancer extends to a broader context, as demonstrated, for example, by American artist Hayv Kahraman, who was born in Baghdad in 1981. During the COVID-19 pandemic, as she grieved her mother’s death from cancer, she created artworks that explored parallels between the militaristic language used to depict the “war” against viruses, cancer, and migrant populations who “invade” the body politic (Barrie 2021).

In 1977, Deena Metzger forged connections between the Holocaust and cancer as injustices that should and could be addressed. She also pointed to the relationship between individual healing and social change. Szapocznikow, Massad, and Brunstein provided powerful testimonies relevant to this relationship, identifying, conceptualizing, and ascribing meaning to their experiences, using visual language to convey what is indescribable in words. In their attempts to portray the unspeakable, they created links between past and present, demonstrating that when language fails, the body speaks its truth, exposing the layers of oppression embedded across generations. At the same time, they explored the themes of vulnerability, the lasting impact of intergenerational trauma on the psyche, and resilience. Feminist art influenced these artists, giving them the agency to confront and challenge traditional patriarchal narratives surrounding women’s bodies and empowering their work.

The works of these artists convey the memory of their suffering, but no less, their overcoming of it. Art is essential to cultivating empathy and a sense of community. Victims of trauma, such as those affected by the Holocaust, endure pain not only as individuals but also as part of larger communities. Likewise, in the case of breast cancer, art serves as a medium for sharing the stories of women and their loved ones, raising awareness, and pointing out the social constructions that surround the disease (see, e.g., Potts 2000; DeShazer 2005). The art of these three women bears witness not only to their own experiences but to those of numerous other women. The knowledge and memory rooted in their bodies are embodied in their works and point the way to paths of change, repair, and collective transformation.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | It is important to acknowledge that research that explored psychosocial factors or stress and their influence on breast cancer development has produced mixed findings. Some studies point to a connection between psychological aspects and the incidence of breast cancer, while others indicate less pronounced associations or suggest that isolating the variables is challenging. Research that seeks to deepen the understanding of this complex relationship is ongoing. (See, e.g., Greer and Morris 1975; McKenna et al. 1999; Chiriaci et al. 2018). |

| 2 | In the 1980s, AIDS was another metaphor that linked the Holocaust with disease (See, for example, Kramer 1994; Goshert 2005). |

References

- Ankori, Gannit. 2001. The Jewish Venus. In Complex Identities: Jewish Consciousness and Modern Art. Edited by Matthew Baigell and Milly Heyd. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, pp. 238–58. [Google Scholar]

- Apel, Dora. 2002. Memory Effects: The Holocaust and the Art of Secondary Witnessing. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, Elizabeth Roberts, and Myrna Goldenberg, eds. 2003. Experience and Expression: Women, the Nazis and the Holocaust. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baider, Lea, Tamar Peretz, and Atara Kaplan De-Nour. 1992. Effect of the Holocaust on Coping with Cancer. Social Science & Medicine 34: 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baider, Lea, Tamar Peretz, Pnina Ever Hadani, Shlomit Perry, Rita Avramov, and Atara Kaplan De-Nour. 2000. Transmission of Response to Trauma? Second-Generation Holocaust Survivors’ Reaction to Cancer. American Journal of Psychiatry 157: 904–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, Dan. 1995. Fear and Hope: Three Generations of the Holocaust. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barrie, Lita. 2021. Hayv Kahraman’s The Touch of Otherness at Vielmetter Los Angeles. The Third Line. Available online: https://thethirdline.com/press/70-hayv-kahramans-the-touch-of-otherness-at-vielmetter/ (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Battista, Kathy. 2013. Renegotiating the Body: Feminist Art in 1970s London. London: I. B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Baumel-Schwartz, Judith Tydor. 1998. Double Jeopardy: Gender and the Holocaust. London: Vallentine Mitchell. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Susan E. 2002. Photo Images: Jo Spence’s Narratives of Living with Illness. Health 6: 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Jill. 2005. Empathic Vision: Affect, Trauma, and Contemporary Art. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Betterton, Rosemary. 1996. An Intimate Distance: Women Artists and the Body. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bolaki, Stella. 2011. Re-Covering the Scarred Body: Textual and Photographic Narratives of Breast Cancer. Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature 44: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bos, Pascale Rachel. 2003. Women and the Holocaust: Analyzing Gender Difference. In Experience and Expression: Women, the Nazis and the Holocaust. Edited by Elizabeth Roberts Baer and Myrna Goldenberg. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, pp. 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bridenthal, Renate, Atina Grossmann, and Marion Kaplan, eds. 1984. When Biology Became Destiny: Women in Weimar and Nazi Germany. New York: Monthly Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brunstein, Lorna. 2022. Interview by Mor Presiado. Personal Interview. Zoom. November 8. [Google Scholar]

- Brunstein, Lorna, and Katie O’Brien. 2021. Inherited Trauma, Place, Embodied Memory and Artistic Practice—Conversation. Presented at Migration, Memory and the Visual Arts: Second-Generation (Jewish) Artists, Online Symposium, May 7; Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lxJ2wiSAUdU (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- Brutin, Batya. 2006. The Inheritance—The Holocaust in the Works of ‘Second Generation’ Female Artists. In Women and Family in the Holocaust. Edited by Esther Hertzog. Tel Aviv: Ozar Hamishpat, pp. 315–44. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Brutin, Batya. 2015. The Inheritance: The Holocaust in the Artworks of Second-Generation Israeli Artists. Jerusalem: Magnes. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Chiriaci, Valentina-Fineta, Adriana Baban, and Dan L. Dumitrascu. 2018. Psychological Stress and Breast Cancer Incidence: A Systematic Review. Psychosomatic Medicine 91: 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekel, Tal. 2011. Gendered: Art and Feminist Theory. Bnei Brak: HaKibbutz HaMeuchad. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Delbo, Charlotte. 2001. Days and Memory. Evanston: Marlboro Press. First published 1985. [Google Scholar]

- DeShazer, Mary K. 2005. Fractured Borders: Reading Women’s Cancer Literature. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- DeShazer, Mary K., and Anita Helle. 2013. Theorizing Breast Cancer: Narrative, Politics, Memory. Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 33: 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann, Ruth. 2014. Biographical Notes. In Alina Shpochnikov: Body Traces. Edited by Ahuva Israel. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, pp. 101–41. [Google Scholar]

- Felman, Shoshana, and Dori Laub. 1992. Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History/Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, W. Arthur. 1995. The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness, and Ethics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, Sigmund. 1958. Remembering, Repeating and Working-Through (Further Recommendations on the Technique of Psycho-Analysis II). In The Standard Edition of The Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Edited by James Strachey. London: Hogarth Press, vol. 12, pp. 145–56. First published 1914. [Google Scholar]

- Frueh, Joanna. 1994. The Body through Women’s Eyes. In The Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s, History and Impact. Edited by Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard. New York: Harry N. Abrams, pp. 190–207. [Google Scholar]

- Gampel, Yolanda. 2021. Memory of The Present. In But There Was Love: Shaping the Memory of the Shoah. Edited by Michal Govrin, Etty Ben-Zaken and Dana Fribach-Heifetz. Jerusalem: Carmel, pp. 62–71. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Amos. 2006. Introduction. In Dominick LaCapra, Writing History, Writing Trauma. Translated by Yaniv Farkash. Tel Aviv: Resling, pp. 7–27. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Amos. 2013. Body, Pleasure and Irony in the Representation of the Suffering of the Holocaust Period. In Pain in Flesh and Blood: Essays on Malady, Suffering and Indulgence of the Body. Edited by Orit Mittal and Shira Stav. Or Yehuda: Dvir, Beer-Sheva: Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, pp. 62–100. [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg, Myrna. 1990. Different Horrors, Same Hell: Women Remembering the Holocaust. In Thinking the Unthinkable: Meanings of the Holocaust. Edited by Roger S. Gottlieb. New York: Paulist Press, pp. 150–66. [Google Scholar]

- Gonen, Ruth. 1996. Anat Massad: For the Purpose of The Plot. Curated by Drora Dekel. Kabri: Kabri Gallery. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Goshert, John Charles. 2005. The Aporia of AIDS and/as Holocaust. Shofar 23: 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, Steven, and Tina Morris. 1975. Psychological Attributes of Women Who Develop Breast Cancer: A Controlled Study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 19: 147–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedgepeth, Sonja M., and Rochelle G. Saidel, eds. 2010. Sexual Violence against Jewish Women during the Holocaust. Waltham: Brandeis University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann, Marlene E. 1986. Gender and Destiny: Women Writers and the Holocaust. New York: Greenwood. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, Judith Lewis. 1992. Trauma and Recovery. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog, Esther, ed. 2008. Life, Death and Sacrifice: Women and Family in the Holocaust. Jerusalem: Gefen. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, Marianne. 1997. Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hlavek, Elizabeth. 2022. A Meaning-Based Approach to Art Therapy: From the Holocaust to Contemporary Practices. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Rae. 2008. Oppression Embodied: The Intersecting Dimensions of Trauma, Oppression, and Somatic Psychology. The USA Body Psychotherapy Journal 8: 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Amelia. 1998. Body Art: Performing the Subject. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Esther, and Joan Ringelheim, eds. 1983. Women Surviving the Holocaust: Proceedings of the Conference. New York: Institute for Research in History. [Google Scholar]

- Keinan-Boker, Lital, Neomi Vin-Raviv, Irena Liphshitz, Shai Linn, and Micha Barchana. 2009. Cancer Incidence in Israeli Jewish Survivors of World War II. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 101: 1489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koonz, Claudia. 1987. Mothers in the Fatherland: Women, the Family, and Nazi Politics. New York: St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kosh Zohar, Talila. 2013. Memory of Life: Reading Second-Generation Holocaust Fiction. Theory and Criticism 41: 287–63. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Larry. 1994. Reports from the Holocaust: The Story of An AIDS Activist. New York: St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kulasekara, Dumith. 2017. Representation of Trauma in Contemporary Arts. Athens Journal of Humanities & Arts 4: 35–60. Available online: https://www.athensjournals.gr/humanities/2017-4-1-3-Kulasekara.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- Langer, Lawrence L. 1993. Holocaust Testimonies: The Ruins of Memory. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lippard, Lucy R. 1976. The Pains and Pleasures of Rebirth: Women’s Body Art. Art in America 64: 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Liss, Andrea. 1994. The Body in Question—Rethinking Motherhood, Alterity and Desire. In New Feminist Criticism Art, Identity, Action. Edited by Joanna Frueh, Cassandra Langer and Arlen Raven. New York: HarperCollins, pp. 80–96. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, Ruth, and Ruti Chinski-Amitai. 2020. The Gendered Art of Ariela Shavid. Erev Rav. Art. Culture Society. Available online: https://www.erev-rav.com/archives/51796 (accessed on 8 January 2023). (In Hebrew).

- Massad, Anat. 2009. Interview by Mor Presiado. Personal interview. Kibbutz Kfar Masaryk, Israel. September 4. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Massad, Anat. 2010. Interview by Mor Presiado. Personal inreview. Kibbutz Kfar Masaryk, Israel. September 29. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Maytles, Ruth, Maya Frenkel-Yosef, and Amit Shrira. 2021. Psychological Reactions of Holocaust Survivors with Low and High PTSD Symptom Levels during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders 282: 697–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, Molly C., Michael A. Zevon, Barbara Corn, and James Rounds. 1999. Psychosocial Factors and The Development of Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Health Psychology 18: 520–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1962. Phenomenology of Perception. New York: Humanities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, Deena. 1997. Tree: Essays and Pieces. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. First published 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, Iris. 2003. Past Present: Biography, Identity and Memory in Second-Generation Literature. Tel Aviv: Am Oved and Tel Aviv University. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, Boaz. 2002. The Nazi Weltanschauung: Space, Body, Language. Haifa: Haifa University Book Publishing. Tel Aviv: Maariv Library. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, Simon. 2001. The Aesthetics of Affect: Thinking Art beyond Representation. Angelaki 6: 125–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofer, Dalia, and Lenore J. Weitzman, eds. 1998. Women in the Holocaust. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, James Stuart. 2002. Bathsheba’s Breast: Women, Cancer and History. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peretz, Tamar, Lea Baider, Pnina Ever-Hadani, and Atara Kaplan De-Nour. 1994. Psychological Distress in Female Cancer Patients with Holocaust Experience. General Hospital Psychiatry 16: 413–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, Griselda. 2013. After-Affects|After-Images: Trauma and Aesthetic Transformation in The Virtual Feminist Museum. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Potts, Laura K. 2000. Why Ideologies of Breast Cancer? Why Feminist Perspectives. In Ideologies of Breast Cancer: Feminist Perspectives. Edited by Laura K. Potts. York: St. Martin’s Press, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Presiado, Mor. 2016. A New Perspective on Holocaust Art: Women’s Artistic Expression of the Female Holocaust Experience (1939–1949). Holocaust Studies: A Journal of Culture and History 22: 417–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presiado, Mor. 2018. The Expansion and Destruction of the Symbol of the Victimized and Self-Scarfing Mother in Women’s Holocaust Art. Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies & Gender Issues 33: 177–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presiado, Mor. 2019. Multi-generational Memory of Sexual Violence during the Holocaust in Women’s Art. In War and Sexual Violence: New Perspectives in a New Era. Edited by Sarah K. Danielsson. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh Verlag, pp. 147–82. [Google Scholar]

- Records of the Eichmann Trial. 1961. Sessions 65 to 75. Ministry of Justice Website. Available online: https://www.gov.il/he/Departments/DynamicCollectors/eichmann_written?skip=60 (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- Restany, Pierre. 1973. Alina Szapocznikow: Tumeurs, Herbier. Paris: Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. [Google Scholar]

- Ringelheim, Joan. 1983. The Unethical and the Unspeakable: Women and the Holocaust. Simon Wiesenthal Center Annual 7: 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, Pnina. 2002. Images and Reflections: Women in the Art of Holocaust. Kibbutz Mordei HaGetaot: Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Rosolowski, Tacey A. 2001. Woman as Ruin. American Literary History 13: 544–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothberg, Michael. 2000. Traumatic Realism: The Demands of Holocaust Representation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sadetzki, Siegal, Angela Chetrit, Laurence S. Freedman, Nina Hakak, Micha Barchana, Raphael Catane, and Mordechai Shani. 2017. Cancer Risk among Holocaust Survivors in Israel—A Nationwide Study. Cancer 123: 3335–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaer, Robert. 2005. The Trauma Spectrum: Hidden Wounds and Human Resiliency. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Scheflan-Katzav, Hadara. 2022. Thou Shalt Tell Thy Daughter: Mothers Tell Daughters Their Holocaust Story—Three Case Studies of Contemporary Israeli Women Artists. Arts 11: 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharsheret. 2010. The Impact of the Holocaust on Breast Cancer in Jewish Families Today. Webinar. July 14. Available online: https://sharsheret.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/ImpactOfTheHolocaustOnJewishFamiliesToday.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- Shik, Na’ama. 2010. ‘In Very Silent Screams’: Jewish Women in Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration and Extermination Camp, 1942–45. Ph.D. Thesis, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Shrira, Amit, and Irit Felsen. 2021. Parental PTSD and Psychological Reactions during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Offspring of Holocaust Survivors. Psychological Trauma 13: 438–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontag, Susan. 1978. Illness as Metaphor. Harmondsworth: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel, Gabrielle E. 2007. Revising the Past/Revisiting of the Present: How Change Happens in Historiography. History and Theory 46: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steir-Livny, Liat. 2022. Traumatic Past in the Present: COVID-19 and Holocaust Memory in Israeli Media, Digital Media, and Social Media. Culture & Society 44: 464–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szapocznikow, Alina, Elena Filipovic, Joanna Mytkowska, Corlina Butler, Jola Gola, and Allegra Pesenti. 2011. Alina Szapocznikow: Sculpture Undone, 1955–1972. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. Brussels, Belgium: Mercatorfonds. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, E. Laura. 2013. Living Breast Cancer: The Art of Hollis Sigler. Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 32–33: 219–39. [Google Scholar]

- Tickner, Lisa. 1978. The Body Politic: Female Sexuality and Women Artists since 1970. Art History 1: 236–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Alphen, Ernst. 2006. Second-Generation Testimony, Transmission of Trauma and Postmemory. Poetics Today 27: 473–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardi, Dina. 1992. Memorial Candles: Children of the Holocaust. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, Naomi. 2002. The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used against Women. New York: Harper Perennial. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Iris Marion. 2005. On Female Body Experience: “Throwing Like a Girl” and Other Essays. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Young, James E., ed. 2000. At Memory’s Edge: After-Images of the Holocaust in Contemporary Art and Architecture. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zion-Mozes, Heftzi, Merav Rabinovich, and Rivka Tuval-Mashiach. 2022. “My Body Calls Me”: Narratives of Israeli Women Recovering from Breast Cancer. Society & Welfare Journal 42: 150–70. Available online: https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/reports/molsa-social-and-welfare-magazine-42-2-moses-z/he/SocialAndWelfareMagazine_Magazine-42-2_42-2-MOSES-Z.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2023). (In Hebrew).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).