Abstract

This article demonstrates that ecological art is a very specific art form that follows its own methods of creation and, consequently, of dealing with material and its definitions. This view of ecological art is directed by art theory factors and fundamental questions of art history. Therefore, the main question in discussions on material and the functions of art is that of what contemporary ecological art produces in terms of the concepts ‘natural’ and ‘nature-fair.’ By analysing the artists Thomas Dambo, Aviva Rahmani and Tomás Saraceno, this article finds that, compared to various artistic forms that deal with ecology and the environment, ecological art acts more in the physical reality of the environment and ecosystems. Subsequently, what ecological art is actually producing is ‘a nature thing’, meaning a concrete effect on or intervention in the environment with gestures of appropriation, regeneration and coexistence, being above all ‘art for nature.’ The article shows that, in ecological art, the linear relationship between material and artwork, in that the artist transforms the material to its final form, namely the artwork, is absent. In ecological art, the aim is an ongoing process in which material can have different facets: the material can be a mere auxiliary instrument, the art object itself can become material for something else and the material in general can be understood as an overarching aim and motive: nature.

1. Introduction

This article focuses on contemporary artworks and artists dealing with ecology and climate change from the art theory perspective of materiality. The aim of the article is to show that ecological art has its own methods of producing art, and of also dealing with material and how it is defined. This is not only because modernism art has changed the way materiality is considered, but also because ecological art is a very specific art form. The article first briefly discusses three fundamental issues: the importance of material in art theory since pre-modern times; the general purpose of art, which is essential for ecological art, the intentions of which go beyond aesthetics; and finally, the characteristics and definitions of ecological art. Subsequently, results from analyses of the work of the following artists are presented: Thomas Dambo, Aviva Rahmani and Tomás Saraceno. They not only work and deal with material in different ways, but also have different concepts of artworks and teleological approaches.

2. Methods and Thesis

What ecological art produces in material terms and the purpose of ecological art can be discussed from an interdisciplinary perspective; for example, from the viewpoints of art history, social sciences and media studies (Kagan 2013; Patrizio 2019). However, in this article, the focus is principally theoretical art. The aim is to apprehend the principles and possible definitions of a relatively new art form, because it is necessary to work through the multidisciplinary criteria for ecological art, such as technological, natural scientific and sociological criteria, in terms of art theory and also for scientific methods of art history.1 This methodological approach, which has already been applied to political and social art (Emmerling and Kleesattel 2016), is a new approach regarding ecological art, especially when addressing the question of what ecological art produces in terms of art theory. This question does not attempt to find other new terms for ecological art, but to deepen its actual principles. That is the task of art theory. This will be elaborated on further in the text. Two assumptions underlie the discussion in this article. On the one hand, it is assumed that pre-modern art theory (which was essentially a verbalisation of artistic practice) continued in artists’ theory during and beyond the modern period, which means in artistic concepts such as preparatory considerations, working theses and reflections in constant dialogue between theory and practice, which have determined the theoretical discourse since modernity (Stoltz 2023; cf. also Blunck 2014). On the other hand, there is the consideration that, since the modern period, art theory discourse has gone beyond purely artistic and aesthetic questions, thus expanding the reference space between the artist, the work and the audience. These are concepts, for example, that focus on the significance and status of art activity in relation to world events and generate questions about the tasks and position of art in relation to social, political and ecological changes, such as those regarding migration, war or climate (Stoltz 2023).

Therefore, the focus of this analysis is on artistic activities that, throughout the process of creating a work and in its impact or intended impact target, the principle or concept is ‘natural’. This thesis is that ecological art goes beyond the meaning of the artwork as an object, thus expanding the materiality of artistic action, but at the same time, and this is very striking, ecological artworks refer the audience back to the material (nature, natural materials, non-natural materials, etc.) in a very narrow sense because the tools, aims and principles of ecological art follow the concept of ‘natural’.

3. Fundamental Issues

3.1. Material

Material is “a substance from which something is made or can be made”.2 This sentence is a strictly meant, traditional and still valid principle in the creation of a work of art, especially of visual art. It is also a strictly art theory issue, established, for example, by one of the most important art theorists, Benedetto Varchi, who wrote in his treatise Due Lezzioni (1549) that art always begins with the artist, is a process and pursues its aim according to a certain order and causality in dealing with the corresponding material (Varchi 1549). In the Renaissance, artistic material was also considered a virtual substance, as another art writer, Lodovico Dolce, explained in his dialogue-treatise L’Aretino: “The whole art of painting in my judgement is divided into three parts: inventions, drawing and colouring. Inventions are the fables or histories that the painter chooses for himself, or that are placed before him by others as the material to work with”.3 Nevertheless, it was not the entity of material that was decisive for material as an art-theory question in the Renaissance. Material is a substance to struggle with—also physically4—but above all a subject to deal with in a certain way to solve a problem while creating an art object.5 Additionally, there was the understanding that when the artist sees or recognises the concept or a vision of a figure in material, only the hand has to strain to obey and follow that intellectual concept, while the material now fully complies with the hand. Michelangelo wrote in one of his sonnets in Rime (ca. 1528–1554, first posthumously published in 1623) about a marble sculpture:

- The greatest artist does not have any concept

- which a single piece of marble does not itself contain

- within its excess, although only a hand

- that obeys the intellect can discover it.6

However, the very crucial view of material was the understanding that the material—physical or virtual (like lines and colour strokes)—and also the technique should disappear before the viewer’s eyes as soon as the art object is produced. The art object itself and what it represents (in the Renaissance, of course, an optimal imitation of nature) should only be perceptible to the viewer, not how it was made and with which material.7 This is a principle that actually applies to the art of the present day, for this total virtuality and otherness of the artistic object in relation to the reality of life is the central characteristic of art in general. As the philosopher Susanne Langer wrote in her treatise Feeling and Form (1953), this is the central feature of any art. She discussed her theory of art in isolation from any type of art or historical moment. She wrote: “All forms in art (…) are abstracted forms, their content is only a semblance, a pure appearance” (Langer 1967, p. 50). To create a brief digression following Langer’s principle, the moment Duchamp presented the pissoir as The Fountain, the object became something else beyond its material constitution, and, being ready-made, it became virtual, an illusion outside the reality of the viewer’s life.8

Of course, material has always been discussed in terms of its aesthetic or actual economic value (like gold or bronze) and also iconologically; i.e., in terms of its symbolic and cultural significance (Wagner 2001). Nevertheless, discussions of material in art theory and also in art studies are from a conventional perspective. All theories and debates about material essentially focus on the meaning, transformation, integration and adaptation of material to the artwork to be created, and its aesthetic appearance in the artwork process and after the work is completed. As explained about Varchi’s theory, there is a linear relationship between the material and artwork—the art begins with the artist and ends with the artwork, transforming material—and this principle persists in all theories until modern times and applies from Semper’s Der Stil (Semper 1860, 1863) to Derrida’s Matériau/Matériel/Dématérialisation (Derrida 1985). Now, instead of asking how art or an artist deals with material in order to make an art object, it is much more challenging and revealing, especially since modern art, to ask what art produces beyond the artwork as an aesthetic and virtual object. Surprisingly, for pre-modern art theory, this question does not create contradictions. Every art object also has a function beyond its aesthetic appearance, it is a piece of furniture, a political gift or teaching material.9 In modernism, these features—aesthetics, material, technique and function—have ambivalent relations. This is due, for example, to the concept of Art pour l’art being wrongly considered to imply a functionlessness of art, or the concept of the ‘aura’ or sublimity and uniqueness of an art object, as Benjamin states in his Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit (1936: The work of Art in the age of its mechanical/technological reproducibility).10 In various theoretical discussions since modernism, it appears that only in design can an art object be simultaneously seen as a ‘usable’ object in its materiality and beyond its aesthetic appearance.11 Only in design does being a work of art not exclude or contradict its entry and factual effect in real life.

3.2. Functions of Art

The relationship of an art object to the reality of life has to do with the question of its function. The teleology of art is primarily a concern of aesthetics and the philosophy of art. It has recently been discussed by philosopher Judith Siegmund (2019). Starting with Adorno’s well-known statement that art presents the world, but in doing so is purified of purpose (Adorno 2017, p. 77), Siegmund targeted, above all, the sociological question of the function of art. One of her important conclusions was that the functions of art signify causal structures in relation to society as a social order, not only in the sense of performance, but also in the sense of the creation of contexts. A change in the function of art is therefore a change in the effect of artistic practices (Siegmund 2019, p. 36). In an essay collection, Funktionen der Künste (Eusterschulte et al. 2020), together with other researchers, she also discussed the functions of art: Here, most contributions see the ambivalence of art and artistic activity in its social role in the sense that if it becomes too involved in the reality of life and, for instance, becomes a social action, its status as art threatens to slide towards ‘non-art.’ Many writers oppose functionality to autonomy and social systems to the distinct position of art. For example, Feige states that the autonomy of art means “being different”, “not being transparent” (Feige 2020, p. 34)—in a similar sense to Langer’s “otherness”. It can have social or political effects, but “to treat a work of art as a work of art is to measure it solely by what it establishes out of itself” (Feige 2020, p. 36). Krüger, on the other hand, suggested a kind of aesthetic bias in socially engaged art, which becomes simply social work when it becomes “unspecific” in the artistic. The social value of art must include the specificity of art (Krüger 2020). Other contributions, however, read the intrusion of artistic actions and artwork in the reality of life and, on the other hand, the intrusion of the audience in the (actual) illusion or virtuality of the artwork as something that is always redefined, but is also always conscious, especially in performance (Van den Berg and Kleinmichel 2020). The ‘rigid’ question of the function of art is, therefore, dissolved in the dynamics of artistic action or works of art as improvisation, learning by doing, rehearsing, trying, work in progress and playing (Maar 2020; Buchmann 2020).

Summarising these critical discussions and following important art theory statements both in pre-modern times and since modern times (as cited above, Varchi, Dolce and Langer, for example), it is possible to conclude that basically any artistic action (as a poietic action) is not only goal-oriented (Varchi 1549) and able to assume a purpose or have a purpose imposed on it (Dolce 1557), but it always follows its proper (autonomous) rules and methods (Varchi 1549)—in design and determinations of form and material, etc. Langer defined this as “art’s own logic”: “Yet the arts themselves exhibit a striking unity and logic, and seem to present a fair field for systematic thought” (Langer 1967, p. 4). Of course, from the perspective of art theory and especially since modern art and its expansion of the concept of art (as also shown in discussions by Eusterschulte et al. (2020), it is not only the completed art object that is focussed on here, but also artistic action and the process of creating itself.12 However, a work of art and also artistic action always have to do with the audience in some way, and therefore, with the social circumstances, and consequently, with the cultural, economic, political and ecological circumstances. This fact already constitutes the ‘functionality of art,’ which, as the discussions in Funktionen der Künste demonstrate, cannot be described with this term since it has the connotation of a fixed determination of a functionality. It is more suitable to speak here of “social effect” (Bertram 2020), which can be variable, individual, diffuse, etc., and of course, dependent on the extent to which the social effect has been conceived in the artwork or artistic action. This is the point of ecological art: it goes far beyond the creation of a virtual artistic object or action as it aims at an actual impact in the reality of life. Therefore, it aims at ‘social effect’.

However, ecological art also goes beyond the “social effect”. This is a central argument for ecological art, which is illustrated in this article. For this reason, two artists are also briefly discussed, Ólafur Elíasson and Barbara Dombrowski. Both are artistically concerned with climate change issues, but their art is not to be understood as ecological art (Section 4). However, in order to explain what actually distinguishes ecological art from an art-theoretical point of view, its most important concept, the concept of the “natural”, will first be explained.

3.3. The Concept of Natural and Definitions of Ecological Art

‘Concept’ in the sense of intellectual abstract syntheses and explanations of artistic practice, which in pre-modern art literature was understood as a discussion of norms and rules and since modernity, as was stated above, can be understood as an artistic programme, ideology or preparatory considerations, working theses and reflections (Stoltz 2023), needs terminological processes such as the concept of ‘mimesis’, which is discussed as ‘imitation,’ ‘contrafactum’, etc. However, a crucial term in discourses on ecological art is not ‘natural’ but ‘sustainable’.13 As Sacha Kagan insightfully summarised, the terms ‘sustainability’ and ‘sustainable development’, which have emerged since the 1970s with ecological movements, cover three areas: “social justice”, “ecological integrity” and “economical well-being” (Kagan 2013, pp. 9–12).14 Kagan also gives a meaning to sustainability that aptly captures the complex relationship among factors operating underneath and affecting the reality of life:

More generally, besides the discussion-point of economic growth, the use of the term ‘sustainability’ suggests a different priority in framing the future of humanity in terms of its balanced evolution, linking social and ecological issues, rather than framing it in terms of a linear development-course with the economy as its main focus.(Kagan 2013, p. 10)

With regard to culture and the arts, on the other hand, the term ‘sustainability,’ as Kagan states (Kagan 2013, pp. 345–49), has been more and more discussed in artistic discourse since the 1990s. Kagan refers above all to Hildegard Kurt’s theory on the “aesthetics of sustainability”15 and generally criticises the various discourses on sustainability as arbitrary when it comes to what is actually happening in the arts (Kagan 2013, pp. 348–49). It should be noted that this is because the authors actually understand sustainability at its core as only the sensitivity of artists and audiences to, for example, nature-friendliness, cultural diversity and the inclusion of social dimensions.16 Kagan then correctly elaborates on the complexity of ecological artistic practice in entrepreneurship discourse (Kagan 2013, pp. 399–429).

Without attempting to define the correct or precise term, however, the paper here focuses on the concept of ‘natural’, even if it is rightly considered too complex and historically associated with romanticism (Kagan 2013, p. 356).17 Kagan plausibly dissociates from the term “naturally”, debating art and ecology from the social, and also philosophical and, above all, economical point of view, understanding this term as too general. Nevertheless, regarding art history and focusing on theoretical perspective, the term ‘natural’ is quite suitable as an overarching concept given the many methodological, technical and material artistic practices that can be subsumed under ecological art and the associated variable vocabulary used in the discourses of artists or critics. From a narrow view of what ecological art produces, the concept of natural can be understood as nature-friendly, nature-appropriate or nature-fair. For example, the material aesthetics term ‘materialgerecht’ (‘material-fair’), which was intensively discussed in the 19th century in Gottfried Semper’s Der Stil (1860–1863), mentioned above, in Alois Riegl’s Stilfragen (Riegl 1893) and in Heinrich Seipp’s Materialstil und Materialbestimmung of 1902 (Seipp 1902), among others. The requirement for art to conform to the properties and determination rules of material (in the iconological and, above all, aesthetic senses) cannot, of course, be applied by analogy to what natural fairness might mean. This term—‘naturgerecht’—is actually only and eventually used in the field of architecture (See Hundertwasser 1996). In relation to the visual and performing arts, however, it would basically cover nature-conscious artistic action in relation to material, which ranges from a strictly sustainable to a non-existent use of materials.

‘Natural’ or ‘nature-fair’ can take on other meanings. However, before investigating the leading question regarding the concept of natural, it is important to ask what ecological art is. There are many different keywords that refer to art forms that deal with ecological, climatic or nature-related issues and that can be subsumed under the general or popular terms eco art, ecological art or climate art. There has long been a critical reception that attempts to define the genres and subgenres of these art forms. For example, a distinction is made between ‘environmental art/environmental design’ and ‘ecological art’, and between ‘ecological restoration’ and ‘sustainable art/design’.18

Environmental art and design are art forms that work with thematic content on nature and natural materials.19 Land art has become an important part of environmental art.20 Ecological art can also be understood as a specific form of art that, for example, creates complex artificial spaces in which to experience nature, in particular by applying the principles of ecosystems, often in the context of artistic research and collaboration with natural scientists, or which generally collaborate with natural science research.21 Ecological restoration of, for instance, polluted land and water areas can also be executed in the form of artistic action and intervention.22 Finally, sustainable art or design consists of the production of artworks that do not have a negative impact on the environment or are recyclable, recycle or use recyclable materials and, last but not least, natural materials.23 All these terms are still being discussed and differently used so they should by no means be regarded as established terms.24 It is obvious that there are also overlaps. However, as is well known, all these genres were already tried out in the 1960s. Lastly, Joseph Beuys is considered in many respects to be a pioneer of ecological art. Referring to here, of course, to his 7000 Oaks in Kassel.25

The works of the artists that this paper will analyse could be discussed under the headings ‘environmental art’, ‘ecological art’ and ‘ecological restoration’. They demonstrate that nature-fair means more than (nature-)conscious handling of material and reveal artistic gestures and aims in relation to nature that can be described as appropriation, regeneration and coexistence, and lead to a specific ecological-artistic attitude. This attitude consists of being at the disposal—not only of the audience and the reality of life but—above all, of nature (sometimes even entirely). With this, the effectiveness of ecological art not only reaches the social reality of life, but actual ecological physical circumstances. It is not just more than ‘art for art’, but ‘art for nature’.

4. Artists

4.1. Thomas Dambo

The Danish artist Thomas Dambo, who calls himself a ‘recycle art activist’, could be described as an environmental artist.26 His projects include activities in which collected plastic waste is transformed into works of art, such as the sculpture park The Future Forest created near Mexico City in 2018.27 This kind of project has already become an artistic genre in its own right. See, for example, similar actions by other artists and artist organisations such as STUDIOKCA and Alejandro Durán.28 These projects also include social or ecological measures initiated by and with the participation of the artists in the form of de facto institutional aid for a certain population or its living space combined with the acquisition of sponsorship for such measures.29

However, other sculptures by Dambo are becoming increasingly well-known: They are made of leftover wood, such as the Trolls and Hidden Giants, which have meanwhile become Dambo’s trademark and are installed not only but primarily in rural places, landscapes, parks and nature reserves. They are walkable, touchable statues that blend into the rural ambience and are available to people (Figure 1).30

Figure 1.

Thomas Dambo, Mama Mimi, Rendevouz Park, Jackson Hole, USA. Source: https://thomasdambo.com/works/mamamimi (accessed on 30 August 2022). Courtesy Thomas Dambo.

For example, Dambo said about the installation of a troll figure: “It’s a kind of treasure hunt, a gift for families in Denmark, who may feel sad that they can’t go on vacation this summer. The trolls help remind us that there are these beautiful places practically in our backyards”. (Cited in Barger 2020). Based on the Nordic tradition of fables and legends about trolls, these giant figures represent, for Dambo, guardians of the environment and guides into nature, regarding especially the idea of the revaluation of nearby places. These sculptures are therefore, in their aesthetic execution and texture, first and foremost art objects which are perceived above all as virtual and, as Dambo says, are the starting point for a narrative about trolls and about nature (Barger 2020). However, on the other hand, the Troll sculptures blend visually—and physically—into the landscape. They become—natural—components of it because they are as much at the mercy of the weather and natural changes as the trees from the remains of which they were created.31

Dambo’s art is suitable, appropriate and pleasing in the aesthetic sense, and in the sense that it is made for people and contact with them. It can be touched, used as a place to sit on, etc. Appropriateness is one of the most concise, aesthetic and moreover social aesthetic rules for art since the pre-modern era, and was of course mainly directed at the content of pictures.32 Here, from the perspective of the ecological question, appropriateness (i.e., specifically nature appropriateness) would mean compliance with the social demand for concrete positive action or influence on conservation of nature and restraint in the use of natural resources for the production of art (here, leftover wood), but above all restraint or rather assimilation of the art object in the ambience. For Dambo, this is entirely appropriateness, virtual and physical, to nature:

I also believe if you make anything in nature, you should do it with respect for the way nature works and the way nature looks. Because of that, I try not spray my sculptures with red plastic paint or slap concrete all over the place. This way, if I leave my sculpture in the forest and no one ever came to clean it up, it is just made of wood and nails that will rust and it will disappear and go back to the earth. Also, aesthetically, I think people don’t find it as intrusive if you find something made of wood in nature than if you find something made of plastic or concrete. Because it feels like it is at home.(Dambo 2021)

4.1.1. Excursus: Land Art

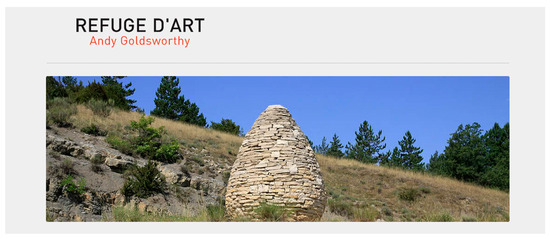

Andy Goldsworthy’s Refuge d’Art can also be entirely set within the above parameters.33 It is a 150 km route in a nature reserve in Provence (Digne-les-Bains) (Refuge d’art 2022) where various sculptures are set up (Refuge d’art 2022). It is a total work of art—which is typical of ‘land art’—in which the individual art objects are bare of what viewers would call artificial or artistic forms and, of course, material.34 Most of these sculptures or objects are made of stones, earth and leaves collected on site and are, in their way, deliberately exposed to their material ephemerality, to change through weathering, and therefore, to transience. Here, the concept ‘natural’ is taken to the extreme (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Andy Goldsworthy, Refuge d’art, sculpture of stones. Musée Gassendi collection, Digne-les-Bains. Source: https://www.refugedart.fr/?la=esp&rr=&ind=&his= (accessed on 30 August 2022). Courtesy Musée Gassendi.35

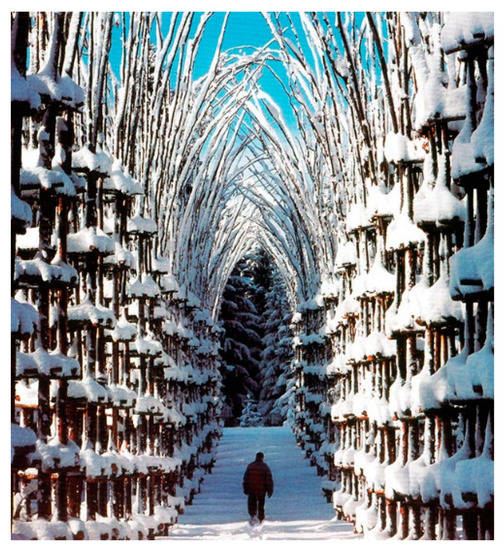

The museum park Arte Sella in South Tyrol operates in a different way, but according to similar principles.36 There, works are exhibited that were also created from wood scraps or stones, but also architecture made from growing plants (Figure 3, Giuliano Mauri, Cattedrale Vegetale, 2001), and finally, from inorganic (but not environmentally harmful) materials such as metal, for example, as floating net bodies interacting with the elements of air and light, and set up, or rather hung, against the backdrop of the sky.37

Figure 3.

Giuliano Mauri, Cattedrale Vegetale, installed at Arte Sella in 2001. Source: http://www.giulianomauri.com/test/cattedrale-vegetale-orobie/, accessed on 12 August 2022. Photo: Aldo Fedele. Courtesy Archivio Giuliano Mauri.

All three examples, by Dambo, Goldsworthy and in Arte Sella, are aesthetic virtual objects—trolls, cathedrals, narratives—and they set themselves apart from their surroundings. However, they have an important thing in common regarding permanence and ephemerality. In most cases, these works are meant to permanently remain on site, but are also meant to conform to the environment and can or should change—by themselves or be changed by the environment—so they are ephemeral in their design. Therefore, the boundary between the environment and the work in its physical condition and in virtuality is abolished because both are constantly changing and a constant interplay between the two is created.38 In this way, these art objects become natural objects; they become things of nature.

4.2. Aviva Rahmani

Aviva Rahmani is one of the most well-known and influential exponents of ecological art.39 She not only creates projects that restore specific ecosystems, but she generally works with ecological systems. Aviva Rahmani’s principle is that art can and should intervene—positively and progressively, of course—in environmental degradation according to the principle of ecological intervention, “ecovention” (Lipton and Spaid 2002).40 In her Blue Rocks project (Figure 4), Rahmani painted forty large rocks around a causeway on Pleasant River on Vinalhaven Island in Maine. She used a water-soluble non-toxic paint mixture with moss content in order to increase the moss growth on these rocks. In this water area, the problem was that the obstruction of water streams and also of intermingling of fresh and salt water caused stagnation of the water. Rahmani’s artistic action was therefore linked to a request for this water area to be cleaned and renatured, which was in fact subsequently approved and funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Later, changes during the renaturation and afterwards were observed.41

Figure 4.

Aviva Rahmani, Blue Rocks, 2002–2012 (above: the rocks painted with blue colour, underneath: the state of the site of Pleasant River after Rahmani’s “blue colour-action” and after the renaturation.). Source: https://www.avivarahmani.com/water-ecosystem-preservation-ecoart (accessed on 30 August 2022). Courtesy Aviva Rahmani.

In her work Rahmani applies ‘trigger-point-theory’, on which she wrote her doctoral thesis. This theory is a guiding principle in Rahmani’s oeuvre and research, not only in relation to the ecosystem itself, but more narrowly in relation to the conservation of species and to tracking climate change.42 Trigger point theory essentially states that regional or generally enclosed activities can trigger developments on a larger scale in a kind of chain reaction, and that art can sharpen this trigger. In the abstract of her PhD thesis, Rahmani synthesises her theory as follows:

By combining art and science methodologies, the author revealed insights that could help small restored sites act as trigger points towards restoration of healthy bioregional systems more efficiently than would be possible through restoration science alone.(Rahmani 2015, p. vi)

In Blue Rocks, the artistic action of painting the rocks was a trigger for the ecological restoration campaign of a small area. It has subsequently been traced whether it had an effect in the region of Pleasant River on Vinalhaven Island. With her installation The Blued Trees Symphony (beginning in 2015 in New York State), Rahmani is saving trees and land areas from pipeline dissemination. The trees become part of a musical composition using GPS, and therefore, they have to be considered pieces of art and cannot be cut or removed for artistic copyright reasons.43 In her project Fish Stories, a series of webcasts and events initiated a study in order to find modalities to remedy pollution of the Gulf of Mexico by the Mississippi River, considering all possible factors from the habitat of the fish to local politics and economy, and even to racism. It is summarised on Rahmani’s website as follows:

The Gulf to Gulf team collaborated to show synergy between environmental factors, including climate change, affecting indicator species of fish in the Mississippi, in the vicinity of Memphis. Many people are not aware that fish are affected by all the same factors causing disruptive droughts, storms, temperature extremes, and flooding worldwide that impact people. The team chose Memphis as a critical point between factory farms upstream and dead zones downstream in the Gulf of Mexico, affecting the survival of fish. (…) the “trigger point” for healing dead zones in the Gulf of Mexico is Iowa, because it’s at the center of Midwestern factory farms releasing nitrogen into the water system flowing into the gulf.(Rahmani 2022a)

Rahmani works with and for ecosystems. She uses the trigger point principle to explore the source of damage to an ecosystem and then to initiate and subsequently pursue its improvement. Her installations, drawings, paintings, photographs and artistic actions are themselves triggers and also aesthetic documentation (Rahmani 2022a). However, the real product of Rahmani’s artistic work is the regeneration and protection of ecological systems, plants and animals, or rather the beginning and continuation of the process of regenerating and protecting nature.44

4.3. Tomás Saraceno

Tomás Saraceno has taken a completely different approach to relating to and being in touch with nature. One could say that Dambo’s and Goldsworthy’s works seek an immediate manifold sensory access to nature for the audience, whereas Saraceno creates sensory experiences with, for example, his net installations that should allow the audience intellectual access and lead to knowledge. Saraceno is concerned with making life systems and their interrelationships tangible and understandable, such as how carbon emissions fill the air, how fine dust enter the lungs and how electromagnetic radiation envelops the earth.45 Saraceno’s net installations are intended not only to change and sharpen the audience’s view of their own immediate physical reality, but to also develop insights into new possible life systems in the experimental confrontation of social systems and ecosystems. His most important projects with this aim are Aerocene and Arachnophilia. Both work with the principles of socio-ecological systems and how they work and could work in the future. Aerocene is a neologism related to the new geo- and social-political term ‘Anthropocene’ (the current geological age with human domination) and it means the current geological age of air. The aim of Aerocene is to develop projects to curb carbon emissions and move towards a “a society free from carbon emissions”.46 Arachnophilia, on the other hand, is a project researching spiders’ webs. Together with researchers from the Technische Universität Darmstadt, Saraceno has created a scanner which allows the construction of a model of spider webs.47 This project aims to think about new systems of social and ecological relations between humans and nature. Saraceno comments on his artistic research as follows:

Ecosystems must be thought of as networks of interaction in which each living being evolves together with the others. By focusing less on individuality and more on reciprocity, we can move beyond the consideration of the means necessary to control the environment and envisage a shared development of our everyday life.48

Ultimately, what Saraceno wants to create through his technological and natural science research is a coexistence community that realises sustainable life. His artistic ecosystems, such as air models, art objects and artistic actions, serve to expand and inform the community. One of his most striking works is his Aerocene sculpture (Figure 5), which combines all these things. It is a symbol of carbon emission reduction and a model experiment to make a balloon fly made of recycled plastic and using only air and kinetics. It is also a perpetual art action that has been made in several versions by the artist and can be made by the audience (with instructions from Saraceno’s website) and a single actual physical art object at the same time (Saraceno 2022b). For this reason, what Saraceno actually creates are imaginary (models and installations) and factual (communities and web) systems of co-existence of human beings in the environment. Saraceno’s website emphasises this:

In an era of ecological upheaval, there is a perceived imperative for anthropocentric worlds to re-attune to other species and more-than-human ways of inhabiting our shared planet. These artistic and scientific enquiries can enable new hybrid encounters and relationships, involving multiple entities: from spiders to humans, from gravitational waves to particles of dust.49

Figure 5.

Tomás Saraceno, Aerocene (Fly with Aerocene Pacha). 21–28 January 2020, Salinas Grandes, Jujuy, Argentina Human Solar Free Flight as part of Connect, BTS, curated by DaeHyung Lee Courtesy the artist and Aerocene Foundation. Photography by Studio Tomás Saraceno, 2020 Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 by Aerocene Foundation. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fly_with_Aerocene_Pacha,_Tom%C3%A1s_Saraceno_for_Aerocene_(2020).jpg (accessed on 12 August 2022).

5. Discussion

5.1. A Nature Thing: What Does Ecological Art Produce? What Is Its Material?

What does ecological art produce? So-called environmental art and land art produce installations and sculptures that visually and, above all, physically fit in with nature because they are made from organic materials or primary non-organic materials that are not taken from nature (such as marble from the caves of Carrara), but are found as waste material from nature and are ‘returned to nature’ by placing the sculpture or object in the landscape and exposing it to the weather. They become parts of nature; nature things. In such objects, the material is defined not only as a substance that is subjected to the artist’s activity, but also to that of nature. On the other hand, however, the material is defined as a substance that has priority, which does not stay behind the artistic work, but becomes a co-protagonist, or even almost the sole protagonist. In works like those by Dambo, this is true not only from an aesthetic sensual point of view but also from an iconographic (the troll narrative) if not also an ideological one, because it is recycled natural material. Finally, the artistic object is also the material itself—a substance that is ‘used’ by nature, for example, also in plant architecture (Giuliano Mauri, Cattedrale Vegetale, Arte Sella). Nonetheless, with all of the possible consistency of artistic action with these natural principles in the use of materials and in production, this natural object, this natural thing, remains an artistic object that may then have to be repaired or cared for, and it is an object made of a material that has been changed, shaped or formed according to the artist’s idea, so it also remains a quintessential art object, a virtual and physical natural thing.

In the art of renaturation, such as Rahmani’s, from the elementary point of view of artistic logic (in Langer’s words), the product is nature itself. Basically, it is the process of regeneration that is artistically created or initiated. The artistic material is only a means to an end, and so is the artistic object made from it (e.g., Rahmani’s trees that become a part of a music piece with an installation of a GPS). Both are subordinate and may even disappear altogether (the GPS, the blue colour of the painted stones in Pleasant River). From a purely art theory point of view, neither the artistic material nor the artistic object play decisive roles here. It is the actual process of regeneration and preservation, of the trees for instance, that is factually in the foreground. Nature is not only the product but the material to preserve—for the existence of life. Of course, the artistic context is always present, be it in documentary photos or drawings of Rahmani’s actions or in symphonies created around the trees preserved in New York state.

In ecological art that virtually and creatively works with ecosystems, i.e., that artificially creates them or explores them with models or images, the significance of the artistic material is just as secondary: it serves as aesthetic and scientific illustration. However, at the same time the material is iconographically, scientifically and also ideologically focussed. It is the thematic protagonist, like air in the Aerocene sculptures. Finally, the material, as in Saraceno’s air-dust models, also tactilely, physically and concretely takes centre stage. The Aerocene sculptures are ‘nature things’ as they realise concrete co-existence in the nature: an aerodynamic balloon made out of recycled plastic. Last but not least, they are not only artistic objects. They turn out to also be material, for experiments by the artist, the audience and the Aerocene community.

5.2. Excursus: Ecological Art and Its Variability?

Before summarising the art theory considerations on ecological art of this paper, a brief digression on the different approaches or typologies that can be subsumed under ‘eco’ art is presented. The question, however, is not about the definitions themselves, but about the methods and ideas behind the definitions of typologies and categories of art.50 Weintraub, for example, points out in her book on ecological art, To Life (Weintraub 2012), in which she discusses over forty eco artists, the artistic and conceptual approach of ecological art is extremely different, even though, for Weintraub, it has the same aim: “All (…) augment humanity’s prospects for attaining a sustainable future” (Weintraub 2012, p. XIV). In several figures, she pointedly illustrates the different types of art, artistic strategies and approaches that she recognises in the oeuvres of the artists studied. Here, we find general and well-established types of arts, such as performance and social practice, and newer ones, such as digital art, bio art and generative art, but also conventional forms such as sculpture and print (Weintraub 2012, pp. xviii–xxxv). The growing diversity of artistic genres and their combination together with the diversity of techniques and materials has been, of course, an artistic phenomenon since the 1960s, so that it can also be generally observed that artists either iconographically orient their techniques and materials, i.e., in terms of the content of their works, or that they actually work with a certain material and aesthetically play it out in many ways (Stoltz 2015). It changes, as Weintraub shows in her book, when an artist has an aim that goes far beyond the aesthetics of an art object or art activity. Here, the various art forms, techniques and materials in use flow into one channel. This is the case of political art, social art and, of course, eco art.51

Weintraub sees the variations in ecological art more from the point of view of its various aesthetic art genres, but she establishes an important aspect of the definition of ecological art, namely its goal: “sustainable future”. However, the distinction of ecological art, be it environmental art (land art), ecological (or ecosystems) art or ecological restoration, can be done, as shown by Dambo, Rahmani and Saraceno, from one more point of view, namely from the perspective of their actual effects, or rather the aim of the concrete effect on the environment. This is explained by a brief discussion on two abovementioned artists, Barbara Dombrowski and Ólafur Elíasson.

Barbara Dombrowski is an artist who is more and more well-known, and whose work is dedicated to the theme of the environment. She mainly works with photographs and uses them as communication strategies.52 One of her prominent works is the Tropic Ice project, which has been running for about ten years and consists of photograph exhibitions and photographic installations to draw attention to the global impact of climate change and the interdependencies between regions. The photographs are mostly individual portraits of people from various regions, which she takes on her targeted travels in all five continents. A photo installation in Greenland best represents Dombrowski’s project. It is a series of close-up portraits of people from Amazonia and Greenland installed in front of an iceberg in Greenland (Figure 6). Similar images were then installed in Amazonia.53

Figure 6.

Barbara Dombrowski, Tropic Ice. Source: https://www.barbaradombrowski.com/installationamazonia-greenland (accessed on 30 August 2022). Courtesy Barbara Dombrowski.

With these installations, Dombrowski connects two places—east Greenland and the Amazon basin in Ecuador—and their populations, and thus two regions that are in the most critically vulnerable areas in the current climate crisis. Even though Dombrowski uses specific materials for her installations—the photos are printed on light textiles that are quickly damaged by the weather—to draw more attention to the vulnerability of nature and living conditions, her work is primarily visual and, being supported by exhibitions, web presentations and lectures, purely communicative.

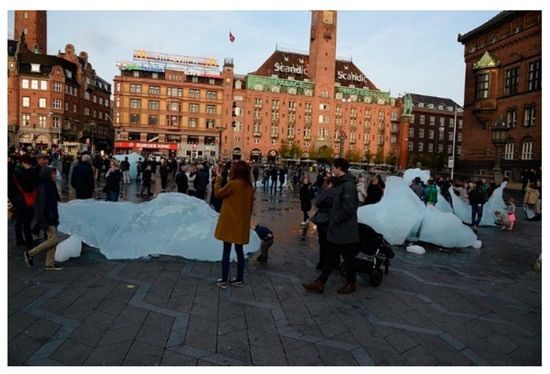

The work of Ólafur Elíasson, on the other hand, is the epitome of eco art. He is one of the best known and studied artists, not only in the context of ecological art but also regarding the aesthetic theme of sensorial experience.54 His oeuvre ranges across various installations, projects and activities. These include, for example the provocative action Green River (1998), in which he coloured rivers in various cities with green colouring that is usually applied by biologists to track water streams in order to recall the importance of water and human dependence on nature. Another work is The Weather Project (2003), an installation created by collaborating with scientists to create indoor weather and day-rhythm phenomena (Tate Modern Gallery). Maybe less known, but mostly seen as ‘useful’ by critics, is the Little Sun project (2012), which produces and distributes millions of solar LED lamps worldwide, a social practice project with the ecological aim of “clean energy”.55 More famous, however, is the Ice watch action. In 2014, Elíasson initiated this project with a spectacular installation of ice blocks from Greenland that was first set up in Copenhagen’s City Hall Square—to mark the publication of the UN’s climate report. The ice blocks were formed into a clock in the squares to boldly demonstrate the temporal urgency of stopping the ongoing ice melt (Figure 7). These ice blocks, weighing several tonnes, were cut out at Nuuk and transported by ship and not by aeroplane. Nevertheless, this action was criticised as being too histrionic and not really environmentally friendly.56

Figure 7.

Ólafur Elíasson. Ice watch (Copenhagen, 2014, (Foto: Jorge Láscar, Melbourne, Australia)). Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ice_Watch_%2837898431101%29.jpg (accessed on 30 August 2022). Licensed under the terms of the cc-by-2.0.

Comparing the two artists discussed, Dombrowski and Elíasson, with Dambo, Rahmani and Saraceno, it becomes clear that the question of the definition of ecological art in general is still open between the parameters of artistic means, genres and impact aims, but here, the definitional view of ecological art can perhaps be narrowed. Ecological art aims first at the product, which is not only far beyond the aesthetic, but wants to achieve an actual intervention in nature and for nature. The works and activities of Dombrowski and Elíasson also go far beyond the aesthetic, but their intervention is actually first directed at society and the human condition (solar lamps for underprivileged populations); society, that in turn should make more ecological interventions. This would define Dombrowski and Elíasson’s art as social practices that address the themes of nature and ecology. Their influence on climate issues can therefore be considered indirect. Finally, human involvement is the common point of all the artists presented here, be it in the communication practices about the climate change issue by Dombrowski, the audience participation by Rahmani and Saraceno or in Dambo’s Giants for everyone. However, the crucial aspects that define Dambo, Saraceno and Rahmani as ecological artists are the goal of an immediate or concrete impact on nature. As stated in the chapter on the functions of art, ecological art goes beyond “social effect”.

6. Conclusions

Considering the question of what ecological art actually produces and, consequently, how it deals with material, it turns out that it must be defined more precisely. In this article, the components of a more stringent definition have been proposed on the basis of the artistic concept of ‘natural.’ ‘Natural’, which—if one reviews the works of Dambo, Rahmani and Saraceno discussed—is basically an active and concrete intervention in nature and for nature, with the premises of nature appropriateness, nature regeneration and the creation of systems for sustainable co-existence between humans and nature. Ecological art is, therefore, a very specific art, as it has concrete intervention in nature as its primary aim, from which artistic strategies are than developed. The artworks by Dombrowski and Elíasson, on the other hand, focus on the moment of communication. They want to change society’s attitude to ecology or climate change, and basically conduct artistic social intervention under the heading of ecology.

This distinction is, of course, by no means a qualitative judgment, but an attempt to make a clarifying contribution to the still open art history discourse (as could be seen with Weintraub) about the enormous variability of art since the post-war period. The impossibility of fixed definitions—here, regarding ecological art—is obvious given the many overlaps and border crossings. (The solar lamps by Elíasson could also be considered concrete action for a sustainable system of coexistence, like Saraceno’s Aerocene sculptures.) The individual iter of an artistic oeuvre must also be taken into account (the recycled plastic sculpture park for children in Mexico by Dambo might instead be called social practice art). Nonetheless, regarding the ecological artists presented here, one can emphasise that in attempts to circumscribe and define art forms, not only materials, techniques and strategies should be considered, but also what they produce and their actual intervention in the reality of life.

Subsequently, it is not only necessary to see ecological art from an aesthetic perspective, but it is also necessary to see reality-related actions, motivations and products of art in their artistic essence because they belong to the artistic conception. This means that non-artistic components and artistic components do not have to be opposed in artistic practice in order to distinguish between art and non-art. For this reason, the non-artistic part of ecological art, here the effect on nature, should also become an issue for art history. For example, it could be discussed how Rahmani’s ‘ecovention’—the abovementioned water regeneration or the preservation of the trees in her chosen area—actually succeeded.57

This article established that ecological art creates things of nature or for nature. Among these are actual objects, like Dambo’s Troll sculptures. Here too, a clarification is needed, namely between the two terms ‘art object’ and ‘artwork’. The term ‘artwork’ actually refers to all products and activities that can be grouped under a certain overarching title such as Aerocene, Blue Trees and Troll. The artists Saraceno, Rahmani and Dambo rightly also speak here of art projects. It is obvious that ecological art produces nature things, but not art objects in the conventional sense (and in its uniqueness and ‘aura’) (Cfr. also, Crowther 2020). This is clear in Rahmani’s project, because regenerated nature is no longer an object at all; and also in the Trolls and Aerocene sculptures, it is not only that they are changeable and ephemeral, but that they become something that is further used (Wagner 2001, p. 867) by nature in the case of the Trolls and by the audience experimenting with the Aerocene sculptures. They become ‘material’.

Conclusively, regarding the art projects of these three artists, it is possible to state that the vision on the material is stripped of its conventional purpose: The linear relationship of material to artwork is absent. (As was explained with Varchi’s theory: the art begins with the artist and ends with the artwork transforming material). Subsequently, what happens with the material in the ecological art of Dambo, Rahmani and Saraceno is that it attains various facets: The material submits to nature, not to the artist (as explained with Michelangelo), and is used as an auxiliary tool in various moments of artistic creation and processes: blue paint to initiate renaturation, recycled plastic for carbon dioxide-free flying, old wood and nails that appear as the troll that will eventually disappear into nature. Secondly, the art object itself can become material to use for further purposes, Dambos’s Giants and Trolls for playing and climbing on, Rahmani’s trees with GPs to stop patrol pipes, Saracenos Aerocene-baloons for experimenting alternative ways of flying. Finally, material, the natural material, the elements—air, earth, water or wood—actually and concretely, iconographically and ideologically become the main protagonists— because all art projects are about this material; they work for this material: nature.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Here, the very striking methodological view is that of Andrew Patrizio, who sees all aspects and issues of art in a coherent “non-hierarchy” compared to conventional art history and its frequent ideologies (Patrizio 2019, pp. 2–4). I fully agree with Patrizio. Nevertheless, he considers non-hierarchy very much in a socio-political way. Patrizio additionally speaks of an “ecological eye.” He looks at ecological art above all from the point of view of aesthetics, but his book actually discusses more the methodological crisis in art history regarding how it deals with politics, social issues and, of course, ecology. See particularly (Patrizio 2019, part II, pp. 79–129). My aim here is to go back to the principles and bases of artistic activity. Therefore, I look at ecological art regarding its two aspects—artistic and non-artistic—as inclusive, in the sense that they always belong together. See below in the text. |

| 2 | See the entry ‘material’ in the Encyclopaedia Britannica (Britannica n.d.). As the art historian and one of the most important researchers on artistic material, Monika Wagner, explains in the Ästhetische Grundbegriffe dictionary, the term material is a derivative of ‘matter,’ which in turn is the philosophical counterpart to ‘form’, and which, in the narrow sense, only means natural or artificial substances that are intended for further processing. However, both terms are equally used in pre-modern art literature. See the entry ‘material’ in the Ästhetische Grundbegriffe dictionary (Wagner 2001) and, for example, Wagner’s article: “Studio matters: materials, instruments and artistic processes” (Wagner 2013). |

| 3 | Author’s translation: “Tutta la somma della Pittura a mio giudicio è divisa in tre parti: Inventione, Disegno, e Colorito. La inventione è la favola, o historia, che ‘l Pittore si elegge da lui stesso, o gli è posta inanzi da altri per materia di quello, che ha da operare.” (Dolce 1557, pp. 22r–22v). |

| 4 | See the anecdote told by the artist Benvenuto Cellini in his autobiography La vita di Benvenuto Cellini (Cellini 1949, p. 368) about the effort and problem-solving needed to create his Perseus and Medusa bronze (1545–1554), which even gave him a fever. In addition, see the discussion in (Stoltz 2021, pp. 52–54). |

| 5 | With the term ‘invention’ Dolce summarises the entire process of designing an image with various drawings as constant problem-solving and changing. He writes, for example: “I would also like to point out that when the painter tries to put the ideas he has in mind into initial sketches he must not be satisfied with just one but should find more inventions and then choose the one that succeeds best (…).” Author’s translation. “Voglio ancora avertire, che quando il Pittore va tentando ne’ primi schizzi le fantasie, che genera nella sua mente la historia, non si dee contentar d’una sola, ma trovar più inventioni, e poi fare iscelta di quella, che meglio riesce (…).” (Dolce 1557, p. 27v). |

| 6 | (Trans.: Ryan 1998, p. 150): “Non ha l’ottimo artista alcun concetto/c’un marmo solo in sé non circonscriva/col suo superchio, e solo a quello arriva/la man che ubbidisce all’intelletto” (Girardi 1967, nr. 151, v. 1–3); Sonnet, ca. 1538–1544, cited and discussed also by Benedetto Varchi in Due Lezzioni (Varchi 1549, esp. pp. 17–18). |

| 7 | The art writer Van Mander discusses the harmony of the components of a picture as lines and colour by comparing them with music: “Not unlike the poets who unite their verses and poems with the lyre or other instruments to please the ear, we must do the same and pair drawing with painting for the delight of the eyes, as the voice with a stringed instrument.” Paraphrase by the author. “Iet onghelijck, maer recht op de maniere/Dat Poeten hun versen en ghedichten/Al singhend’, om t’ghehoor fraey van bestiere/Houwelijcken eendrachtich met der Liere/Oft ander speel-tuygh, moeten wy beslichten/Dat wy, om verlustighen de ghesichten/Oock de Teyckeningh en t’ Schilderen paren/Ghelijck men de stemmen doet met der snaren (Schilder-Boeck, Van Mander 1604, Grondt, XII, 3). |

| 8 | For Duchamp’s ready-mades see Blunck (2017). |

| 9 | For the history of functions in art, see above all Busch’s essay collection (Busch 1987). |

| 10 | For an introduction, see the anthology of theoretical texts on the principle of L’art pour l’art in Luckscheiter (2003) and the historical overview by Olma (2018). Among notable remarks by Benjamin is “It is significant that the existence of the work of art with reference to its aura is never entirely separated from ritual function. In other words, the unique value of the ‘authentic’ work of art has its basis in ritual (…)” (Harrison and Wood 2003, p. 522). See also Benjamin ([1936] 2006, pp. 21–22). |

| 11 | For design theories especially regarding the issue of function, see (Kosok 2021). |

| 12 | The concept of art and its expansion is, of course, a constant theme in the essays of Funktionen der Künste (Eusterschulte et al. 2020). Recent contributions on the concept of art are, for example, the essay by Tiziana Andina, What is Art? The Question of Definition Reloaded (Andina 2017) and Crowther’s book on theories of the art object (Crowther 2020). |

| 13 | Numerous contributions are dedicated to the topic of sustainability and art, for example Ans Wabl, Die Verschränkung von Kunst und Nachhaltigkeit, (Wabl 2015) and Anna Markowska’s conference papers, Sustainable art (Markowska 2015). |

| 14 | See the critical annotation on the derivation of the term ‘sustainability’ from the German term ‘Nachhaltigkeit’ used in 18th century scientific writing on forestry (Kagan 2013, p. 9, n. 1). |

| 15 | A major and current contribution on art, culture and sustainability is Kurt’s book with Bernd Wagner, Kultur-Kunst—Nachhaltigkeit (Kurt and Wagner 2002). |

| 16 | See above all the citation of Kurt in (Kagan 2013, p. 346). |

| 17 | Here, Kagan is referring to Weintraub’s book Ecocentric Topics (Weintraub 2006). |

| 18 | In recent decades, numerous exhibition catalogues and introductions to ecological art have been produced, such as Performing Nature (Giannachi and Stewart 2005). For a critical introduction, see for example the anthology of essays Environment and the Arts (Berleant 2002). |

| 19 | A good in-depth introduction to environmental art as a specific art form is given in the anthology in the journal Tate papers 17, edited by Nicholas Alfrey, Stephen Daniels and Joy Sleeman. See Alfrey et al. (2012). |

| 20 | For a critical and art historical overview, see Landscape into Eco Art by Marc Cheetham (2018). |

| 21 | See, for example, an article written from a scientific point of view: Art/Science Collaborations: New Explorations of Ecological Systems, Values, and their Feedbacks in Bulletin Ecological society of America (Ellison et al. 2018). |

| 22 | See, for example, the article “Environmental Art as Eco-cultural Restoration” (Ball et al. 2011). |

| 23 | For example, see the exhibition catalogue Goehler (2011) and the ongoing cultural activity Zur Nachahmung Empfohlen. Examples to follow, “z-n-e,” supported also by the German Federal Cultural Foundation (z-n-e website 2022). |

| 24 | For discussion on definitions of genres of ecological art as environmental art etc., see above all (Kagan 2013, esp. pp. 271–74). |

| 25 | See the interview “Gespräch über Bäume” (Talking about trees) from 1982. (Beuys 2006). |

| 26 | Thomas Dambo was born in 1979 in Odense, Denmark and lives in Copenhagen. He started an apprenticeship as a carpenter and later graduated from the Design School in Kolding. He has been active with projects and has exhibited since around 2010. For example “250 Birdhouses.” See https://thomasdambo.com/works/250-birdhouses (accessed on 15 August 2022), (Dambo 2022). |

| 27 | https://thomasdambo.com/about (accessed on 12 August 2022), (Dambo 2022). |

| 28 | See for example the work “Skyscraper, the Bruges Whale” installed in Bruges (Belgium), made of rubbish collected in the Pacific Ocean and coloured in white and blue tones. See http://www.studiokca.com/projects/skyscraper-the-bruges-whale/_DSC5998_1 (accessed on 15 August 2022). (STUDIOKCA 2022). Alejandro Durán, born 1974 in Mexico City, graduated among others from Tufts University. His projects include litter collection campaigns at the seaside. The litter is then coloured and displayed on site and photographed as a subsequent action calling for more environmental protection. See “The washed up project.” https://alejandroduran.com/photoseries (accessed on 12 August 2022), (Duran 2022). |

| 29 | See about the activity The Future Forest, https://thomasdambo.com/about/ (accessed on 12 August 2022). (Dambo 2022). |

| 30 | See the article in National Geographic by Jennifer Barger (2020). |

| 31 | Dambo does not use toxic or damaging lacquers for his sculptures. See an interview by immagieexibition.com, accessed on 31 March 2021 (Dambo 2021). See also the citation below. |

| 32 | From the Renaissance, it was widely discussed in art literature what can be depicted or shown and how, for example whether the depiction of a figure blowing a trumpet is actually “appropriate,” as in a chapter of an art treatise by Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo (Trattato, Lomazzo 1584, book 2, XIII, 151). Since modernism, art has translated appropriateness beyond the norms and principles of art into the complex problem of ethics. For a historical overview of ethics and arts in the modern period see, for example, the article collection Art and ethical criticism (Hagberg 2008). For discussion on contemporary art see the article by Nieslony (2022). |

| 33 | Andy Goldsworthy was born in 1956 in Cheshire, England and belongs to an earlier generation of artists dealing with ecological issues. He has been worked for some time with natural material. For his artistic biography, see William Malpas, The art of Andy Goldsworthy (Malpas 2013). |

| 34 | For research on land art in relation to ecology and the aesthetics of landscape, see Cheetham (2018). In his discussion on ‘art objects,’ also Crowther writes about land art, especially about the question of reciprocity in formation between an art object and its surroundings, regarding the definition of sculpture (Crowther 2020, pp. 76–88). See also Ilschner (2004). |

| 35 | Under this image on the website, the following thought of Goldsworthy is cited: “The sculpture here isn’t just the stone, it’s the home, it’s the entire trail.” https://www.refugedart.fr/?la=esp&rr=&ind=&his= (accessed on 12 August 2022). (Refuge d’art 2022). |

| 36 | See above all the online archive for the works exhibited there: http://www.artesella.it/it/multimedia-archivio.html (accessed on 12 August 2022), (Arte Sella 2022). |

| 37 | See also for example ‘The Flying Man’, Cédric LeBorgne, made of wire mesh, http://www.artesella.it/it/progetti-speciali/sky-museum.html (accessed on 12 August 2022) (Arte Sella 2022). |

| 38 | Of course, there are also exceptions, practical obstacles or artistic choices that differ from these parameters. In Arte Sella, for example, there is an installation by Kintera made of old lamps that form a kind of iceberg. This is a purely visual adaptation to the environment and an ecological action in the sense of recycling old lamps (similar to Duran and Dambo with sculptures from plastic waste.) See also below in the text. Krištof Kintera, Memoriale della luce che fu (Memorial of Passed Light), installed in 2021, http://www.artesella.it/it/news/2021/kritof-kintera-memoriale-della-luce-che-fu.html (accessed on 12 August 2022), (Arte Sella 2022). |

| 39 | Aviva Rahmani was born in 1945 and studied Arts, Multimedia, Geographic Information Systems and Aesthetics (with a doctorate thesis entitled Trigger point theory as Aesthetic Activism, 2010–2015) in the United States and the United Kingdom. See for an introduction and overview of her oeuvre the book by Aviva Rahmani: Diving Chaos (Rahmani 2022b). |

| 40 | https://www.avivarahmani.com/water-ecosystem-preservation-ecoart (accessed on 12 August 2022), (Rahmani 2022a). |

| 41 | Blue Rocks, 2002–2012, Pleasant River, Maine, https://www.avivarahmani.com/blue-rocks (accessed on 12 August 2022), (Rahmani 2022a). |

| 42 | https://www.avivarahmani.com/endangered-species-ecoart (accessed on 12 August 2022) and https://www.avivarahmani.com/climate-change-ecoart (accessed on 12 August 2022), (Rahmani 2022a). |

| 43 | https://www.avivarahmani.com/endangered-species-ecoart (accessed on 12 August 2022), (Rahmani 2022a). |

| 44 | On Rahmani, see also (Kagan 2013, pp. 296–300). |

| 45 | Tomás Saraceno was born in 1973 in San Miguel de Tucumán (Argentina). He studied art and architecture in Buenos Aires, Frankfurt am Main and Venice, and has a studio in Berlin. See, for example, the project “Particular Matters,” https://studiotomassaraceno.org/particular-matters-the-shed/ (accessed on 12 August 2022), (Saraceno 2022a). |

| 46 | https://studiotomassaraceno.org/about/ (accessed on 12 August 2022). |

| 47 | “(…) a novel, laser-supported tomographic technique that allowed precise 3-D models of complex spider/webs.” |

| 48 | “Gli ecosistemi devono essere pensati come reti di interazione al cui interno ogni essere vivente si evolve insieme agli altri. Focalizzandoci meno sull’individualità e più sulla reciprocità, possiamo andare oltre la considerazione dei mezzi necessari per controllare l’ambiente e ipotizzare uno sviluppo condiviso del nostro quotidiano.” Citation from an exhibition presentation, transl. by the author, (Strozzi 2020). |

| 49 | https://studiotomassaraceno.org/about/ (accessed on 12 August 2022). (Saraceno 2022a). |

| 50 | While Dambo, as the excursus shows (Section 4.1.1), can be considered representative of land art, and land art is certainly one of the most important parts of ecological art, the art of Rahmani and Saraceno is very specific in its own individual modalities. Some similar caracteristics can be seen by Rahmani and Lynne Hull, especially in her “trans-species-art” (Kagan 2013, pp. 300–2) or in Saraceno and Elíasson (see below), but my point is not to recreate categories of ecological art, but to ask what ecological art should have as a principle from an art-theoretical point of view. See furher in the text. |

| 51 | On political art, see (Hegenbart 2021). |

| 52 | She studied communication science at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts in Dortmund and worked in an advertising agency. |

| 53 | https://www.barbaradombrowski.com/installationamazonia-greenland and https://www.barbaradombrowski.com/tropicice (accessed on 20 August 2022). (Dombrowski 2022). |

| 54 | See, for example, the papers from the Experience symposium (Jones et al. 2016) and the dissertation Zeit-Raum-Bilder (“Time-Space-Pictures”) (Nafe 2019). |

| 55 | See (Elíasson 2022a, 2022b). It is known and obvious that Elíasson has influenced many artists such as Saraceno and Rahmani, but this cannot be discussed here for reasons of space. |

| 56 | See, for example, the article in Der Standard (Rustler 2019). The instalation Ice watch was also set in Paris, at the Place du Panthéon—on the occasion of the 2015 climate conference—and finally, in London at the Tate Gallery and outside Bloomberg Headquarters between December 2018 and January 2019. |

| 57 | Kagan does this from a social point of view: “How many social processes occur through artistic processes that would potentially generate social change (Kagan 2013, p. 400 and passim, esp. 400–29). |

References

- Adorno, Theodor W. 2017. Ästhetik (1958/1959). Edited by Eberhard Ortland. Nachgelassene Schriften. Abteilung IV: Vorlesungen, vol.3. Berlin: Suhrkamp. [Google Scholar]

- Alfrey, Nicholas, Stephen Daniels, and Joy Sleeman, eds. 2012. To the Ends of the Earth: Art and Environment. Tate Papers, No. 17. Available online: https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/17/to-the-ends-of-the-earth-art-and-environment (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Andina, Tiziana. 2017. What is art? The question of definition reloaded. In Art and Law. Leiden and Boston: BRILL, Issue 1.2. pp. 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- Arte Sella. 2022. Museum Park. Available online: http://www.artesella.it (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Ball, Lillian, Tim Collins, Reiko Goto, and Betsy Damon. 2011. Environmental Art as Eco-cultural Restoration. In Human Dimensions of Ecological Restoration. Society for Ecological Restoration. Edited by Dave Egan, Evan E. Hjerpe and Jesse Abrams. Washington, DC: Island Press, pp. 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Barger, Jennifer. 2020. This Copenhagen Artist Turns Trash into Trolls. In National Geographic. Online Resource, June 15. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/this-copenhagen-artist-turns-trash-into-trolls/ (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Benjamin, Walter. 2006. Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit. Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp. First published 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Berleant, Arnold, ed. 2002. Environment and the Arts. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Betram, Georg W. 2020. Improvisation als Paradigma künstlerischer Wirksamkeit und ihrer sozialen Dimension. In Funktionen der Künste.Transformatorische Potentiale künstlerischer Praktiken. Edited by Birgit Eusterschulte, Christian Krüger and Judith Siegmund. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, pp. 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Beuys, Joseph. 2006. Gespräche über Bäume, new ed. Edited by Bernhard Blume and Rainer Rappmann. Wangen: FIU-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Blunck, Lars. 2014. Theoriebildung als Praxis. Zum kunsthistorischen Stellenwert der Künstlertheorie. In Theorie2. Potenzial und Potenzierung künstlerischer Theorie. Edited by Eva Ehninger and Magdalena Nieslony. New York: Peter Lange Pub Inc., pp. 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Blunck, Lars. 2017. Duchamps Readymade. Munich: Edition Metzel. [Google Scholar]

- Britannica. n.d. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/dictionary (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Buchmann, Sabeth. 2020. (Politische) Kunst oder (soziale) Praxis? Eine Versuchsanordnung über die 1990er. In Funktionen der Künste.Transformatorische Potentiale künstlerischer Praktiken. Edited by Birgit Eusterschulte, Christian Krüger and Judith Siegmund. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, pp. 147–64. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, Werner, ed. 1987. Funkkolleg Kunst. Eine Geschichte der Kunst im Wandel ihrer Funktionen. Munich and Zürich: Piper Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Cellini, Benvenuto. 1949. The Life of Benvenuto Cellini. Written by Himself. Translated by John Addington Symonds. London: Phaidon. [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham, Mark. 2018. Landscape into Eco Art: Articulations of Nature Since the ‘60s. University Park: Penn State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther, Paul. 2020. Theory of the Art Object. New York and London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Dambo, Thomas. 2021. Interview. immagieexibition.com, 31 March. Available online: https://www.imagineexhibitions.com/blog/an-interview-with-artist-thomas-dambo (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Dambo, Thomas. 2022. Available online: https://thomasdambo.com (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Derrida, Jacques. 1985. Matériau/Matériel/Dématérialisation. In Les immatériaux. Exhibition catalogue, Centre Georges Pompidou. Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, vol. 3, esp. pp. 42, 124, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Dolce, Lodovico. 1557. Dialogo della Pittura intitolato L’Aretino. Nella quale si ragiona della dignità di essa Pittura, e di tutte le parti necessarie, che a perfetto Pittore si acconvengono. Venice: Gabriel Giolito De’ Ferrari. [Google Scholar]

- Dombrowski, Barbara. 2022. Available online: https://www.barbaradombrowski.com (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Duran, Alejandro. 2022. Available online: https://alejandroduran.com (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Elíasson, Ólafur. 2022a. Available online: https://olafureliasson.net (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Elíasson, Ólafur. 2022b. Little Sun. Project-Website. Available online: https://littlesun.org/ (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Ellison, Aron M., Carri J. LeRoy, Kim J. Landsbergen, Emily Bosanquet, Paul J. CaraDonna, Katherine Cheney, Robert Crystal-Ornelas, Ardis DeFreece, Lissy Goralnik, Ellie Irons, and et al. 2018. Art/Science Collaborations: New Explorations of Ecological Systems, Values, and their Feedbacks. Bulletin Ecological society of America 99: 180–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerling, Leonhard, and Ines Kleesattel, eds. 2016. Politik der Kunst: über Möglichkeiten, das Ästhetische politisch zu denken. Bielefeld: Transcript. [Google Scholar]

- Eusterschulte, Birgit, Christian Krüger, and Judith Siegmund, eds. 2020. Funktionen der Künste. Transformatorische Potentiale künstlerischer Praktiken. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler. [Google Scholar]

- Feige, Daniel Martin. 2020. Die Funktionalität der Kunst? Für einen revidierten Begriff künstlerischer Autonomie. In Funktionen der Künste. Transformatorische Potentiale künstlerischer Praktiken. Edited by Birgit Eusterschulte, Christian Krüger and Judith Siegmund. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, pp. 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Giannachi, Gabriella, and Nigel Stewart, eds. 2005. Performing Nature: Explorations in Ecology and the Arts. Bern: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Girardi, Enzo, ed. 1967. Rime. Michelangelo Buonarotti. Bari: Editori Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Goehler, Adrienne, ed. 2011. Zur Nachahmung Empfohlen!: Expeditionen in Ästhetik und Nachhaltigkeit. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz. [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg, Garry, ed. 2008. Art and Ethical Criticism. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Charles, and Paul Wood, eds. 2003. Art in Theory. 1900–2000. An Anthology of changing Ideas. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hegenbart, Sarah. 2021. Restoring beauty to politics: Working towards a distinction between art and political activism against the backdrop of the Centre for Political Beauty. 21: Inquiries into Art, History, and the Visual 2: 125–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundertwasser, Friedensreich. 1996. Architektur: Für ein natur- und menschengerechteres Bauen. Köln: Taschen Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Ilschner, Frank. 2004. Verkörperte Zeiträume: Eine Auseinandersetzung mit der Land-Art in den Werken von Andy Goldsworthy, Richard Long und Walter De Maria. Duisburg, Essen University. Online-Ressource. Available online: http://www.ub.uni-duisburg.de/ETD-db/theses/available/duett-09152004-222429/unrestricted/ilschnerdiss.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- Jones, Caroline, David Mather, and Rebecca Uchill, eds. 2016. Experience: Culture, Cognition, and the Common Sense. Cambridge and London: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan, Sacha. 2013. Art and Sustainability. Connecting Patterns for a Culture of Complexity, 2nd emended ed. Bielefeld: Transcript. [Google Scholar]

- Kosok, Felix. 2021. Form, Funktion und Freiheit: über die ästhetisch-politische Dimension des Designs. Bielefeld: Transcript. [Google Scholar]

- Krüger, Christian. 2020. Überengagement. In Funktionen der Künste. Transformatorische Potentiale künstlerischer Praktiken. Edited by Birgit Eusterschulte, Christian Krüger and Judith Siegmund. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, pp. 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kurt, Hildegard, and Bernd Wagner, eds. 2002. Kultur-Kunst–Nachhaltigkeit. Die Bedeutung von Kultur für das Leitbild Nachhaltige Entwicklung. Bonn: Klartext. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, Susanne. 1967. Feeling and Form. A Theory of Art, 4th ed. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Lipton, Amy, and Sue Spaid. 2002. Ecovention: Current Art to Transform Ecologies. London: Contemporary Arts Center. [Google Scholar]

- Lomazzo, Giovanni Paolo. 1584. Trattato dell’Arte de la Pittura. Diviso in sette libri. Ne’ quali si contiene tutta la Theorica, & la prattica d’essa pittura. Milan: Paolo Gotardo Pontio. [Google Scholar]

- Luckscheiter, Roman, ed. 2003. L’art pour l’art: Der Beginn der modernen Kunstdebatte in französischen Quellen der Jahre 1818 bis 1847. Bielefeld: Aisthesis. [Google Scholar]

- Maar, Kristen. 2020. Zur Funktion des Tanzes. In Funktionen der Künste. Transformatorische Potentiale künstlerischer Praktiken. Edited by Birgit Eusterschulte, Christian Krüger and Judith Siegmund. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, pp. 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- Malpas, William. 2013. The Art of Andy Goldsworthy. Kent: Crescent Moon Publ. [Google Scholar]

- Markowska, Anna, ed. 2015. Sustainable Art: Facing the Need for Regeneration, Responsibility and Relations. Warsaw: Polish Institute of World Art Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Nafe, Nadja. 2019. Zeit-Raum-Bilder: über Bewegung und Entschleunigung in ausgewählten Arbeiten von Olafur Eliasson und Katharina Grosse. Oberhausen: ATHENA. [Google Scholar]

- Nieslony, Magdalena. 2022. Moralische oder ethische Wende des gegenwärtigen Kunstdiskurses? Bemerkungen zur Geschichte und Gegenwart moralischen Urteilens über zeitgenössische Kunst. 21: Inquiries into Art, History, and the Visual 3: 343–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]