Abstract

By juxtaposing two ostensibly divergent characters, the Jewish art historian and Egyptologist Hedwig Fechheimer (1871–1942) and Soviet filmmaker and theorist Sergei Eisenstein (1898–1948), this paper investigates how both approaches folded time, creating Cubist chronologies. Fechheimer adapted the philological focus of her Berlin School contemporaries to create an ahistorical, anti-teleological grammar of ancient Egyptian art which espoused an artistic affinity between the Egyptians and the Cubist movement. Eisenstein, who held a copy of one of Fechheimer’s books in his personal library, took a similar approach in the development of his critiques of historical allegory. This paper looks specifically at two shots of a sphinx during the bridge sequence in the 1927 film October to demonstrate how they correspond to Fechheimer’s views on Egyptian art and also function peculiarly within the film. Ultimately, I aim to demonstrate how the interpellations of the sphinx demonstrate a particular critique of historicity that Eisenstein later expands upon in his Ivan the Terrible films.

Keywords:

Hedwig Fechheimer; ancient Egypt; sphinx; Sergei Eisenstein; October; film; avant-garde; historicity The first decades of the twentieth century were effervescent with discoveries in many domains, but two of those, Egyptology and film, have surprising overlaps.1 Much has already been written about the “hieroglyphic language” of film, with Jean Epstein asking if cinema could be considered “[…] une langue d’images pareille aux hieroglyphs de l’ancienne Égypte, dont nous méconnaissons le mystère, dont nous ignorons même tout ce que nous en ignorons?” (Epstein 1974).2 and Abel Gance reflecting that “[…] le cinéma nous ramène à l’idéographie des écritures primitives, à l’hiéroglyphe, par le signe représentatif de chaque chose, et là est probablement le plus grande force d’avenir […] Nous voilà, par un prodigieux retour en arrière, revenus sur le plan d’expression des Egyptiens” (Gance 1926).3 Film scholar Antonia Lant has also articulated the haptic tie between the cinema and the Egyptian bas-relief (Lant 1995). The medium of film, meanwhile, with its ability to preserve a dynamic facsimile of a particular space in time was often described as akin to the ancient Egyptian attempts at corporeal preservation via mummification. In his essay “Ontologie de l’Image Photographique” [The Ontology of the Photographic Image] André Bazin linked mummification and cinema when he stated “[…] le cinéma apparaît comme l’achèvement dans le temps de l’objectivité photographique […] Pour la premier fois, l’image des choses est aussi celle de leur durée et comme la momie du changement” (Bazin 1990).4 Lant has also made the connection, noting that the reanimation of mummies “[…] gave form to cinema’s power to rearrange time and space, as well as providing resonances with death”(Lant 1992). These connections linking ancient Egypt, temporal preservation, mummification and film were also earlier noted by the prolific Soviet filmmaker, Sergei Eisenstein—perhaps most obviously in his 1946 text entitled “Dynamic Mummification: Notes for a General History of Cinema”(Eisenstein 2016). It is this last web of interstices—the supra-temporal aspect of cinema conjoined with the Egyptological—that I wish to elaborate upon in this paper.

I will be juxtaposing two divergent characters: the Jewish German art historian and Egyptologist Hedwig Fechheimer (1871–1942) and Soviet film director and theorist Sergei Eisenstein (1898–1948). I will first give a close reading of the bridge sequence in Eisenstein’s 1927 film October, zooming in on two short shots of a sphinx which interject in the montage. While critics such as Annette Michelson have already given erudite and illuminating attention to the bridge sequence, the importance of the sphinx’s temporal interpellation has thus far been largely neglected. However, as brief as the shots are, they function within the film in a number of interesting and critical ways; ways which are both perhaps serendipitously intriguing details and which also bring into sharper focus Eisenstein’s particular theories of historicity.

The film October was commissioned as a celebration of the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution of 1917 but was only released in March 1928, four months after the official celebrations on 7 November 1927. There were 13,000 reels of film shot, of which 9000 appeared in the final version, further attesting to Eisenstein’s considerable editing efforts (O’Toole 2018).5 The film covers the initial hopefulness of the people with the founding of the Provisional Government after the February Revolution, their disillusionment as the Provisional Government does not usher in the longed for peace and prosperity, the Nevsky Square demonstrations in July 1917 and the final uprising under Lenin’s command in October. By the end of October—and the end of October—the new Soviet government begins reforming the state, redistributing land and finally ending hostilities with Germany.

One of the most studied scenes of the film is that of the bridge sequence. In this scene we see a large mass of protestors who are fired upon by cannons—the rapid firing is emphasized through the repeated split second superimposition of guns and gunner as well as the flashing of the cannon mouths—the protestors reach the bridge and banners are carried up—there is a lone banner-bearer with a sphinx in the background, looking over his shoulder. The melee in the streets is repeatedly interjected into the flow of images—we see the crowd approaching—a soldier and a lady embrace on a boat—the soldier leaps from the boat to apprehend and assault the banner-bearing protestor—the soldier is joined by an older woman who begins beating the protestor with her umbrella—the lady in the boat looks on with scorn—the angry crowd nears, with a horse at the front—the horse is shot and stumbles, a swarm of ladies stab at the protestor with their sun umbrellas—the bourgeoisie laughs—a view of the dead horse and a dead lady with long blonde hair is shown from a multitude of angles—there is a phone call with the order to raise the bridges and cut off the workers from the city centre—the under-girding of the mechanical bridge is shown as the halves are slowly raised—the crowds rush past the dead woman and horse—the dead woman’s hair drapes across the gap in the bridge halves—the horse dangles by its trappings into the chasm between the two bridge halves—the bridge halves are nearly at their peak, appearing to represent a pyramid—a sphinx is shown staring off into the distance—the bridge halves rise again in a near perfect pyramid—a close up of the sphinx’s face, still staring [see Figure 1]—with the bridge halves now nearly perpendicular to the street the dead woman tumbles down to crash onto the pavement below—a prone, presumably dead protester is shown lying with his hair in the Neva—the bourgeoisie runs to the railing to gleefully toss copies of The Pravda into the water—the papers fall like confetti into the water and swirl away along the eddies—the dead horse continues to hang over the city—a revolutionary banner is tossed in the river—the horse is finally free of its ballast and splashes into the water. The many superimpositions and juxtaposed shots enhance the perception of chaos, visually assaulting the viewer with gunshots, crowds, beatings, death and maniacal laughter. They also blatantly reorganize the chronology of events; the horse, for instance, is only shown falling into the Neva after the shots of the dead protestor with his hair in the water and the bourgeoisie throwing The Pravda into the river, although the laws of physics would make it more likely that the actual fall occurs when the bridge halves reach their acme and the woman falls to the pavement.

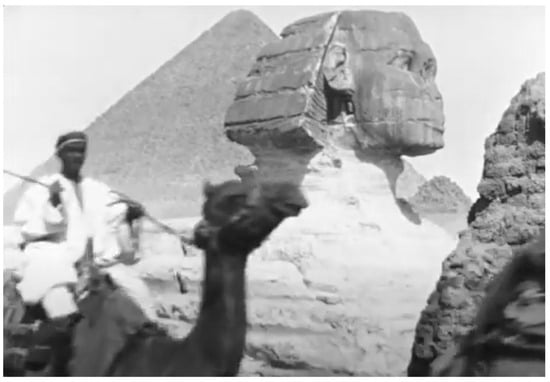

Figure 1.

Screenshot of scene in Sergei Eisenstein’s film October.

The only two moments of stillness in the scene are those of the stony gaze of the sphinx. Even the dead woman and dead horse are surrounded by markers of movement and duration; protestors dash and dart around their inert bodies; the mechanical bridge halves slowly increase their incline, the hair of the woman slips into the widening gap between the bridge halves. The shot of the sphinx is taken from below, giving the impression that the sphinx is staring upward, over the peak of a pyramid below (this is actually the corner of the pedestal the sphinx sits upon in St. Petersburg).

The utter stillness of the monument can be contrasted with the movement of another film of a sphinx: the 1897 short film by Alexandre Promio entitled Les Pyramides (vue générale) [see Figure 2]. Promio was engaged by the Lumière Brothers’ company and had set off over two months to capture films of some of the world’s most celebrated monuments. He arrived in Alexandria, travelled to Cairo, Giza and along the Nile to Upper Egypt. Les Pyramides (vue générale) “consists of a single almost 50-s shot that displays various layers of a sort of visual archaeology, divided into three planes: in the first, a row of travelers moving across the frame; in the second, the face of the Sphinx; and in the third, the towering pyramid” (Allan 2008). With the Great Pyramid in the background and the Sphinx at the centre of the scene, it is the first of these planes which most aptly emphasizes the life and duration of the film.

Figure 2.

Screenshot from Alexandre Promio’s film Les Pyramides (vue générale). Vue N. 381.

The mis-en-scène of Eisenstein, in contrast, has a pyramid shape in the foreground and a sphinx looming overhead, perhaps implying that the riddle of the sphinx supersedes the petty lives (and deaths) of humankind. The lack of spatial contrasts in the Eisenstein shots pluck the sphinx out of space and deny the viewer any reliable indication of the size or location of the statue.

The fact that the two shots of the sphinx in October stand alone as still, silent sculptures make it all the more remarkable that a discussion of them has often eluded scholarship. One of the most in-depth readings of the bridge sequence was done by Annette Michelson in her article “Camera Lucida/Camera Obscura” in 1973, where she notes that in

[o]pening the bridge, Eisenstein opens, as well, a vast wedge of time within the flow or progress of action […] As action is subjected to the extensive analytic reordering, when a multiplicity of angles and positions of movements and aspects alters the temporal flow of the event and of the surrounding narrative structure, the disjunctive relations of its constituents are proclaimed, soliciting a particular kind of attention, and the making of inferences as to spatial and temporal order, adjustments of perception. And the inferences, the adjustments thus solicited reinforce the visibility of things, make for a particular kind of clarity. Eisenstein gives us within this insertion another complex of insertions that intensify our sense of temporal flow in abeyance, conferring upon the sequence […] something we may call the momentousness of the epic style. [Italics in original].(Michelson 1973)

I want to delve into the detail of the sphinx shots, to show why these two short shots of serenity in a staccato montage of seemingly jumbled juxtapositions and dynamism are relevant to Eisenstein’s edited temporal flow.

One reason why the sphinx shots might evade explicit explication is that ostensibly, the sphinx is just a part of the architecture surrounding the bridge. Both shots in the scene are of the “Western” sphinx of Amenhotep III, one of a pair of sphinxes which sit on a quay in front of the Imperial Academy of Arts building in St. Petersburg. The two sphinxes have sat on their pedestals on the University Embankment in St. Petersburg, temporally and geographically exiled from their sunny, sandy homeland, since April 1832 or 1834 (Solkin 2007; Whitehouse 2016; Williams 1985).6 The two sphinxes were greatly admired by Jean-François Champollion, who had attempted to purchase them but was thwarted by Russia. According to Helen Whitehouse, “a pair of Egyptian sphinxes from the mortuary temple of Amenophis III at Thebes was placed on the Neva embankment in St. Petersburg. The site—the landing stage beside the Academy of Arts—was chosen by Nicholas I himself, the setting was designed by the Academy’s Professor of Architecture, Konstantin Thon, and the sphinxes came to number among the most familiar landmarks of the city”(Whitehouse 2016).7 Born beneath the desert sun in the fourteenth century BCE, the two serene, syenite statues have replaced the languid waters of the Nile for the frigid Neva, facing each other in a foreign land.

The placid expression of the face of Amenhotep III gazing off into the distance evokes an eternal complacency of the ruling classes over the suffering of the masses. The eternal element of the Egyptian statue is emphasized when compared with the earlier scene of the dismantling of the statue of the Tsar; with only superficial damage to his postiche, the Egyptian sphinx has, across millennia and continents, largely maintained its integrity. What the sphinx represents, thus, seems to belie the demolishment of the Tsarist regime in favour of the Provisional Government. There is a change in leader, but the old arrangement of power in the hands of a few has remained—or, in the words of Jean-Baptiste Karr, “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose”.8 Perhaps serendipitously the sphinx in St. Petersburg lends itself quite aptly to this reading. Amenhotep III ruled over an Egypt that was peaceful and prosperous, a reign rife with architectural and sculptural achievements (Kozloff 2012). He also ruled on the eve of one of the greatest revolutions of Egypt’s history. Amenhotep III’s son, Amenhotep IV, would later change his name to Akhenaten and radically alter the cultural praxis of his country. The older, traditional polytheism was replaced by a monotheistic worship of Aten, the sun disc. Akhenaten then built an entirely new city, Akhet-Aten (now Tel el-Amarna) and transported the capital thence. Akhenaten was so radical—such an aberration from the traditional pharaohs—that his name was kept off official kings lists and his existence was only discovered in 1911 during excavations done by Alessandro Barsanti, Flinders Petrie and the Deutsche Orientgeselleschaft.

There is a sense then that the stony gaze of Amenhotep III, impervious to the chaotic revolution taking place on the bridge and in contrast to the demolished statue of the Tsar, slyly indicates a wariness with the longevity of the protestors’ project: it is the face of the precursor to the revolutionary Akhenaten who still survives on his pedestal; not Akhenaten. However, it is also possible to simply see the sphinx as representative of ancient Egypt, a period associated with a supreme splendor of wealth and luxury for the elite but presumably built on the backs of multitudinous labourers. Even when eliminating the Akhenaten angle, the sphinx silently speaks to the longue durée of unequal distribution of power and resources. As François Hartog notes, “[j]uxtaposer deux dates, ou plutôt les superposer, c’est exprimer à la fois leur écart, leur impossible coïncidence et les rapprocher l’une de l’autre: renvoyer de l’une à l’autre, produire un effet de réverbération, de contamination.”9 The choice to cut to the sphinx would fit in Eisenstein’s project where, according to Antonio Somaini, “Eisenstein ‘was searching for ce qui ne passe pas dans ce qui passe’ for that which doesn’t change among what changes”(Somaini 2016).10 In this case, whether one reads into the shots as much detail as the particular pharoanic history of Amenhotep III and Akhenaten or not, the stone statue of power remains a reminder of the longevity of the very concept of “the ruling class”. As such, the sphinx becomes metonymic for all rulers, and the almost callously calm disregard for the tumult on the bridge implies that regardless of who is in charge they will never look down and see those below them.

The blank gaze of the sphinx, and the question of what it sees, can also treated with a Nietzschean reading. According to Greek mythology, Oedipus encounters the Sphinx in Thebes while on a journey of self-imposed exile to avoid marrying his mother and murdering his father—actions that eventually do transpire precisely because of Oedipus’ triumph in solving the Sphinx’s riddle. As such, the story is of course the epitome of the saying that “the road to Hell is paved with good intentions” or, as Robert Burns remarked on turning up a mouse’s nest, “[t]he best laid schemes o’ mice an’ men/Gang aft a-gley”. Friedrich Nietzsche questioned the objectivity of truth in 1885 by taking recourse to the Sphinx when he wrote in The Will to Power, “[t]here are many kinds of eyes. Even the Sphinx has eyes—and consequently there are many kinds of ‘truths’, and consequently, there is no truth”(Nietzsche 1968). Tom Tyler has written on the mysteries implied by this gaze of the Sphinx, and the concept of a multiplicity of truths. Arguing that the answer supplied by Oedipus was not, in fact, the only possible answer to the riddle but that the veracity of the possible answers was contingent upon the perspective of the speaker, he states: “Nietzsche would have us remember […] that even the Sphinx, even the keeper of this most vital truth, has eyes. And in virtue of that fact, she, like every other living creature, has her own distinctive ways of seeing, her own distinctive truths”(Tyler 2006). If the Sphinx is an embodiment of the enigmatic mysteries of the female, conquered by the superior wit and ratiocination of the male Oedipus, the larger context of the myth points to a nihilistic futility in the victory; why overthrow the Sphinx only to ultimately fulfil the incestuous parricidal prophesy? What secret truths did the Sphinx take with her into the depths of the abyss? From this angle, the sphinx in October, staring serenely over the chasm of the bridge as workers tumble or are trampled to death also intimates the inevitability of events. What good was the February Revolution if the Provisional Government proves to be only another iteration of the Tsarist regime?

Sergei Eisenstein was a prolific reader. Among his many volumes he held several pertaining to ancient Egypt including Geschichte Aegyptens by James Henry Breasted, Sanctuaires d’Orient. Egypte–Grèce–Palestine by Edouard Schuré, Mystères égyptiens by Alexandre Moret and Kleinplastik der Aegypter by the German Jewish art historian and Egyptologist, Hedwig Fechheimer.11 It is the last volume which I wish to explore more fully. I believe that there are striking resonances between the Cubism that Fechheimer detects in ancient Egyptian sculpture and in the temporal rhythm of Sergei Eisenstein, culminating in a Cubist critique of historicity.

Hedwig Fechheimer, née Hedwig Jenny Brühl, has slowly faded from public memory. Born on 1 June 1871 in Berlin, she spent much of her childhood in Leipzig before training as a teacher in Breslau. It was this teacher training which granted her entrance to the University of Berlin as a guest student of art history and philosophy. Her status as a guest was a function of her sex; it wasn’t until 1908 that women were allowed to matriculate from Prussian universities and even sitting in on the lectures was prohibitively difficult and only possible since the 1890s (Marchand 2009). Female students who wished to attend lectures were required to have permission from the professor and to provide proof of an adequate educational background—although the institutions which would comprise such an adequate education, the Gymnasium and the Oberrealschule, were also only open to male students (Lemberg 1997). Thus, the aspiring female scholar needed not only intellect and the ability to tolerate no small amount of bigotry, she also needed access to the financial resources that would allow her to study abroad or with private tutors. In the domain of Egyptology, which Suzanne Marchand has described as one of increasing exclusivity in the early 20th century, the rise of a Jewish woman to prominence was not only improbable but also demonstrates formidable tenacity on her part (Marchand 2009).

Fechheimer was a close, albeit occasionally critical, companion of a cohort of German Egyptologists known as the Berlin School. With the eminent Egyptologist Adolf Erman at the helm, the Berlin School was characterized by its philological focus. Eschewing the material accumulations of their British and French counterparts, the Berlin School believed that literature was the key to understanding the inner life of a society and, in the words of Christian Bunsen, “[d]ie erste urgeschichtliche Tatsache, die uns hier begegnet, ist die Sprache” (von Bunsen 1845–1857).12 The linguistic emphasis of the Berlin School was manifested in their ambitious endeavor, the Wörterbuch der Altägyptische Sprache [Dictionary of Ancient Egyptian]. This mighty tome would become the largest and most complete dictionary of the ancient Egyptian language in existence (Brewer and Teeter 1999; Silberman 2012).13 Additionally, the first academic journal dedicated exclusively to Egyptology, the Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde [Journal of Egyptian Language and Archaeology], was born in Berlin, 1863 (Brewer and Teeter 1999). The devotion to language inherent to the Berlin School can be partly attributed to a tradition of mining Biblical texts for presumed historical fact, but also largely as a pragmatic consequence of Germany’s exclusion from most Egyptian excavation sites during the First World War (Gertzen 2014).14 Thus, German Egyptologists frequently fell back on philological and lexicographical rigor to recreate ancient Egypt and according to Marchand, “a great part of the scholarly energy in this era [the late 19th and early 20th centuries] was spent, indeed had to be spent, simply in trying to clean up (or besmirch) existing grammars, dictionaries, and lexica”(Marchand 2009). Fechheimer’s attachment to the Berlin School is attested by her studies (she convinced Erman, a professor generally hostile to the notion of women in academia, to allow her to sit in on his lectures), by her associations (she was a friend, confidant and houseguest of Emilie Cohen, wife of Ludwig Borchardt—the Egyptologist credited with finding the famous bust of Nefertiti still contentiously housed in the Berlin Museum as ÄM 21300) and by her reciprocal scholarship with Heinrich Schäfer (Peuckert 2014; 2017).15 However, her critical distance can be discerned by her works, where, unlike the linguistic focus of her cohort, Fechheimer’s philosophy and art history background led her to concentrate on questions of Egyptian art at a general, fundamental level. Until the publication of her first book, Die Plastik der Aegypter [Plastic Arts of the Egyptians] in 1914, this was a topic not dealt with in depth by any members of the Berlin School.

As a first book, Die Plastik der Aegypter was a surprising success.15 Prior to its publication Fechheimer had only two short papers to her name, both published in Cassirer’s Künst und Künstler in 1913. Aimed at a well-read and high-brow, but not necessarily scholarly, audience, the book draws a comparison between the art of the ancient Egyptians and Cubism. In the same vein as Wilhelm Worringer, Fechheimer argues against a teleological approach to art history and the assumption that the Graeco-Romanic works represent the apotheosis of artistic achievement. Rather, she opens Die Plastik with the note that it will examine “[…] das Beste der ägyptischen Kunst, die heute unmittelbar zu wirken beginnt” (Fechheimer 1914).16 This kinship between the work of the ancient Egyptians and her own contemporaneous time is elaborated upon when she claims that

In keiner Kunst ist so wie in der ägyptischen—streng und vielseitig zugleich—das Prinzip der ‘intégration plastique’ moderner Maler und Bildhauer erfüllt, oder Cézannes Grundforderung vorausgenommen: ‘Traiter la nature par le cylindre, la sphère, le cône, le tout mis en perspective, soit que chaque côté d’un objet, d’un plan, se dirige vers un point central. Les lignes parallèles à l’horizon donnent l’étendue -, … les lignes perpendiculaires à cet horizon donnent la profondeur.’ Den Kompositionsmethoden ägyptischer Reliefbildner könnte die folgende (kubistische) Definition der Zeichnung entlehnt sein: ‘Die Kunst der Zeichnung besteht darin, Verhältnisse zwischen Kurven und Geraden festzulegen.(Fechheimer 1914)17

This is a particularly striking take on ancient Egyptian art. The affinity Fechheimer notes between the Cubist artists and the ancient Egyptians derives from what she perceives as their common use of a “point central”; not the receding convergence of perspectival lines à la post-Renaissance art, but rather “the insurpassable plenitude” of “partial views” that Maurice Merleau-Ponty wanted “welded together” to forge a “lived perspective” (Merleau-Ponty 1993). Merleau-Ponty’s explanation was also similar to Carl Einstein’s earlier conception of African sculpture, which he claimed in 1920 is “daß sie eine starke Verselbständigung der Teile aufweisen […] Jene sind nicht vom Beschauer, sondern von sich aus orientiert; die Teile werden von der engen Masse aus empfunden, nicht in abswächender Entfernung; somit werden sie und ihre Grenzen verstärkt sein”(Einstein 1920).18 Fechheimer, who sustained a decades-long friendship with Carl Einstein, was probably heavily influenced by his avant-garde perspective.

Yet, it was Fechheimer’s second book, Kleinplastik der Ägypter [Small Sculpture of the Egyptians], published in 1921, which ties her in the historical record to Sergei Eisenstein. This second book by Fechheimer appeared in 1921 as the third volume in Cassirer’s Exotische Plastik. Die Plastik des Ostens und der Primitiven in Einzeldarstellung [Exotic Sculpture. The Sculpture of the East and the Primitive in Individual Representation]. While not the sensation of Die Plastik der Aegypter, Kleinplastik was nonetheless a success.19 Similar in argumentation to her first book, in Kleinplastik Fechheimer applies the general theory of Die Plastik der Aegypter to the specificities inherent to smaller sculptures of ancient Egypt. The link with modern art is less explicitly pronounced in Kleinplastik, but rather the spiritual, supra-temporal, meta-historical abilities of great art is expounded upon. And it is in this context that we see an interesting overlap with Eisenstein.

What Fechheimer attempts in Die Plastik der Aegypter, and subsequently elaborates upon in Kleinplastik der Ägypter, is a dehistoricized grammar of the plastic arts of ancient Egypt. Her books, while written in an almost floridly lyrical prose and replete with translations of Egyptian texts provided by her fellow scholars of the Berlin School, make no moral judgements on the political times of ancient Egypt nor on the sumptuous excesses she depicts (Kleinplastik der Ägypter opens with an extended quotation running five pages adumbrating the luxuries of the court of Ramses III). Rather, following in the footsteps of Wilhelm Worringer’s 1907 thesis Abstraktion und Einfühlung, she argues for an anti-teleological reception and appreciation of the art of ancient Egypt.20 While her writing places the works within their historical, chronological context, she does not confine them to a trajectory of ever-increasing natural mimesis, nor does she admire rote repetition. Her chronology is chiefly concerned with the changing use values of the objects she is describing: critically, for Fechheimer, plastic arts and sculpture did not immediately arise as an independent domain in ancient Egypt; instead, art was always imbricated with religion—either as a means of embodying composite elements of a personality (an aspect elaborated upon in Die Plastik der Aegypter) or the preservation of the body post-mortem. As such, the “likeness” of a work of art was not intended to be viewed with the modern mendacity of post-Renaissance perspectivism but rather to incorporate a plethora of plastic perspectives; each a distinct unit and yet also a part of a constructed, overriding, whole. It is in this aspect that her work becomes most Cubist.

Sascha Bru offers a succinct overview of the manifold Cubisms of the early twentieth century in his book The European Avant-Gardes, 1905–1935 (Bru 2018). Generally speaking, Bru claims that what united the various manifestations of Cubism was the method of “[s]hattering or fragmenting perspective, rendering multiple perspectives, orienting the observer towards the surface and material of the artwork, moving in and out of recognizable representation” (Bru 2018). These general characteristics of Cubism could then be further characterized into a painterly phase of analytical Cubism wherein “a limited (dark) colour palette was used with minor tonal variation to give shape to subjects whose facets were carefully studied, then broken up into parts, and finally reassembled in a flat grid or diagram that frequently resembled a crystal-like surface” and a synthetic phase which made use of elementary forms, working from memory rather than life, and the introduction of the medium of collage (Bru 2018). Fechheimer’s ambition of a grammar for ancient Egyptian art accords tidily with the notion of a formal language of artistic representation as desired by the analytical phase of Cubism while her descriptions of sculptures given in Kleinplastik emphasize their simple forms and the materials they are composed of in a manner similar to synthetic Cubism. For example, in discussing a series of wooden statuettes of servants from Siut, Fechheimer writes

In sparsame Flächen aufgeteilt, zeichnet der Körper seine herbe Kurve, verzweigt sich in den reinen Biegungen der Arme, die stützen und tragen. Den vollzogenen Ausgleich der Bewegung, der dem berühmten Kontrapost der Griechen nicht nachgibt, betont die Silhouette. Die Künstler des Mittleren Reiches verstehen sich auf das Summarische, auf Zerlegen und Binden der gegliederten form. Sie denken–gänzlich unprimitv–eine Gestalt zur Säule, zur Ellipse zusammen, ohne ihr Lebendiges zu stören.(Fechheimer 1922)21

Fechheimer focuses here on the surface of the statuette, on its constituent forms of curve, column, ellipse—and most strikingly, what she perceives as the Egyptian tendency to de-compose a subject into its constituent forms in order to re-combine them in what she earlier referred to as “sinnlichen Unmittelbarkeit” [sensual immediacy]—which could also be considered a type of primal embodiment. As Joyce Cheng has aptly articulated in her essay “Immanence Out of Sight”, many of these objects were intentionally buried long ago, their sacred purpose not contingent upon the profane perspective of Western spatial conventions in sculpture (Cheng 2009). As such, their use value lies in their immediate verisimilitude as embodiments of ancient Egyptian religion rather than as re-presentations in a modern form of mimesis. Fechheimer herself compares the statuettes of Siut to the Cubism she and Carl Einstein would consider an integral element of African sculpture (Fechheimer 1922). This Cubism is one that relies on an intentional use of “extreme Form” and wherein “[d]ie Flächen sind heftiger gespannt” [the surfaces are more violently tensed] (Fechheimer 1922).

The reconstitution of a fractured subject is also apparent in Fechheimer’s description of the figure of Mete: “[d]iese Figur ist gegliederter, ihre Teilformen sind schärfer gesondert. Dadurch ist sie reich an unterschiedlichen Ansichten. Jede ist Totaleindruck, doch im Kleinsten durchdacht”(Fechheimer 1922).22 The emphasis on simple forms is one Fechheimer traces through the existence of Egyptian art to its very prehistoric beginnings, claiming that even there “[d]ie Phantasie denkt in Kugeln, Zylindern, Spindeln. Das Dreidimensionale ist so verstärkt, daß man zur Abstraktion einer Silhouette fast nicht kommt. Die Künstler hatten die Gabe des ganz Deutlichen, der nackten Form. Sie erfühlen ein Volumen, das der Moderne konstruiert” (Fechheimer 1922).23 Here, again there is an explication based on the deconstruction of the work of art into its many forms, only to reconstruct it anew.

Additionally, key to Fechheimer’s Cubist grammar of ancient Egyptian art is the element of movement and the different perspectives this creates. Here, there is an intriguing overlap with film. Fechheimer often writes that the various sculptures she treats in Kleinplastik depict subjects frozen in motion. When discussing the function of the ka and the servant statues buried in Egyptian tombs, she writes that they may have depicted moving subjects, meaning that each particular form requires a panoply of perspectives in order to incorporate a diachronic dynamism: “[h]ier waren Vorgänge des Lebens zu übertragen […] das Einmalige, leicht Zersplitterte eines solchen Gestus bewältigt: Bewegung ist ruhendes Bild geworden, Symbol eines Daseins” (Fechheimer 1922).24 This capturing of the multiplicity of views engendered by movement in a moment of stasis resonates deeply with the art form of film. Eisenstein wrote as much in his essay “Laocoön” when he referred to film as the “image of movement” and stated that “[i]f we were to be utterly pedantic, we could say that perception of the phenomenon of any movement consists of the continual break-up of a certain static form into a new form.” (Eisenstein 2010a) [Italics in original]. This iterative process of fracture and reconstitution was frequently referred to by Eisenstein as “The Osiris Principle”, named for the Egyptian god who was torn to pieces by his brother Set, but painstakingly puzzled back to life by his devoted sister-wife Isis. What results from the puzzling together of the disparate pieces (or, in the case of the film, shots) is, according to Eisenstein, “not an idea composed of successive shots stuck together but an idea that DERIVES from the collision between two shots that are independent of one another” (Eisenstein 2010b) [Italics and emphasis in original]. Cubism, in Eisenstein’s use of it (and it is worth noting that Eisenstein did not declare himself a Cubist, and also criticized the painterly, analytical form of Cubism for failing in its ambitious goal of caging a multitude of perspectives within a single canvas) is thus not only a question of a novel form of re-presentation, but also a generative impulse (Eisenstein 2010a). The Cubist film would make a careful collation of shots, akin to the collage of synthetic Cubism, which would produce certain psychological affects and associations. What distinguishes this collage from the Dada exploit was its meticulous curation; the Dadaist collage, in contrast, reveled in the random.

It is in this careful collation of shots that the sphinx appears in the bridge sequence of October. Considering that Eisenstein was familiar with Fechheimer’s work and his own theories coincided with hers on the particularity of parts and the necessity of the many perspectival views to capture movement in a static object, it could be fruitful to push the investigation a little further. Going back to Kleinplastik, the extreme placidity and seeming nonchalance of the sphinx works profoundly well in this particular juxtaposition of eras.

Amenhotep’s blank eyes gaze into nothing, unfocused and unchanging, just as the ruling classes have, by implication, always blithely overlooked the suffering of those below them. One is reminded of this particular passage from Kleinplastik:

While Fechheimer treats such a serenity of gaze as a purely artistic choice implying balance and generalizing the particular statue to encompass all people, Eisenstein uses it as a contrast to the manic suffering on the bridge. The sphinx’s gaze then asks the audience: what does it see and what does it mean in conjunction with the contemporaneous moment?Unter den antiken Völkern haben die Ägypter einen Typus des Menschlichen beseelt, der—gänzlich ägyptisch—doch in Gebärde und Fühlen die Menschen aller Zeiten anruft […] Der durch sich selbst aufgerichtete und verwandelte Mensch, der gänzlich unpathetisch in stiller Gelassenheit auf das Künftige sieht, allzu großer Sorge um die unverläßlichen Dinge entfremdet. Irdisches und Ewiges gleichen sich in ihm aus, der—unvollkommen in einer unvollkommenen Welt—doch nicht würdelos vor Gott steht. Über einer vermessenen Mystik, dem Zwang ererbter Kulte und der Hilflosigkeit wüster Beschwörungen scheint eine hellere Religiosität aufzugehen, die das bestehende Leben annimmt und den Tod mit ruhigem Herzen weiß.25

Relevant to the riddle of what the sphinx sees is the exact position in the film of the two shots and the final line of the quote from Fechheimer, “das bestehende Leben annimmt und den Tod mit ruhigem Herzen weiß” [“which accepts the existing life and knows death with a calm heart”] (Fechheimer 1922). The two shots of the sphinx appear at precisely the moment the bridge halves reach their acme and the woman and carriage are loosed from the ballast of the dead horse, careening down to smash onto the pavement. Followed by the dead protestor with his hair in the Neva, the destruction of The Pravda papers and the dramatic fall of the dead horse, the sphinx appears to bridge the gap in time; there was the hopeful riot that stormed the streets heading for the city centre and then the crushing death of the revolutionaries and their enterprise. Situated astride this temporal diremption—the time of hopefulness and the time of despair—the sphinx conjures up, as Fechheimer mentions, the calm uneventful eternity of death and the peace that comes with accepting it. Yet, this leaves us with another quandary: is the sphinx representative of the blindness of the Provisional Government to the desperation of the proletariat, or of the revolutionaries’ willingness to accept death as a consequence of their action? Or, is it possible that the sphinx is susurrating a subversive secret of Sergei Eisenstein: an oblique intimation that the coming ruler (Stalin) is unlikely to go down in the annals of history as a vast improvement on the previous regime? Or is the gaze like that of Nietzsche’s Sphinx: “[t]here are many kinds of eyes. Even the Sphinx has eyes—and consequently there are many kinds of ‘truths’, and consequently, there is no truth”(Nietzsche 1968)?

Eisenstein uses the sphinx as a chronological collision: the ancient Egyptian erupting into the present. The two brief shots are a harbinger of Eisenstein’s later, longer critique of historiography, Ivan the Terrible. As Kevin Platt claims,

[m]ore than any other medium, film could render the past seemingly present while sidestepping the overt articulation of problematic analogies. The fundamental principle of film is that when you move still pictures fast enough you create the illusion of motion. Historical films of the Stalinist era operated according to the reverse principle: if you project enough moving pictures on similar subjects, you can create the illusion of motionlessness […] Eisenstein’s films present a meditation on the instability of historical discourse when it is burdened with the task of rendering comprehensible periods that have been seen as ruptures in collective identity and political formation—liminal epochs such as Ivan’s and the Stalinist era of revolution and war.(Platt 2011)

The sphinx shots are the only two moments of motionlessness in the bridge sequence. Yet, despite their stillness, the silent shots are alive with meaning—all of it contingent upon perspective. That contingency, as Platt explains, becomes almost impossible to pin down when applied to historical analogy. The crux of the problem is that historical time operates like a Cubist film, allowing one object to spawn an almost infinite series of unique perceptions. Michael Allan claims that “time transforms the object into a manifold scattering of objects, based on a manifold scattering of the ‘here and now’”(Allan 2008). By leaving the viewer with more questions than answers, Eisenstein provokes an unease with the use of historical analogy; an unease which would blossom into fruition with his longer, unfinished, trilogy of Ivan the Terrible. The sphinx shots in October are clearly positioned to create an generative collision of chronologies but the resulting historical analogy remains elusively plastic. Perhaps Eisenstein simply did not want to be pinned down too precisely in any sort of criticism. The penalties for doing so could be catastrophic and, as Richard Taylor has pointed out, Eisenstein’s status as a possibly closeted homosexual from the periphery active in a highly competitive field and under the auspices of an increasingly despotic leader meant that he would be under immense pressure to temper or disguise any overt criticism (Taylor 2004). However, the many possible meanings that could be attributed to the sphinx at the specific juncture it appears all chip away at the edifice of a solitary concrete meaning to be derived from historical analogy. Depending on how one views the sphinx allegorically—as a calm member of the elite reposing in luxury on the eve of revolution; as emblematic of the excesses and blindness of the ruling classes; as symbolic of the revolutionaries’ acceptance of death; as a subtle critique of the Stalinist régime—its function within the film shifts.

If Eisenstein and Fechheimer both fold time to bring the past bursting into the present, they do so not allegorically. The exact meaning of any implied allegory between the sphinx and the present time is suggestive but not exclusive nor determinative. Likewise, in Fechheimer’s assertion that her contemporaneous moment bore an affinity with the ancient Egyptian, it was not because the two were producing the same art work all over again; it was because the world of art had come to a moment ripe for similar reflections and contemplations on the fundamental meaning and use value of art. If one were to imagine allegorical time folds as accordion folds, zig zagging back and forth across history in precise layers, the folds of Fechheimer and Eisenstein rather resemble those of origami. With manifold creases and pleats of disparate sections, they nonetheless create a compound of perfectly folded intersections of paper, infinite points centraux ripe with rhisomatic meaning.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | All translations, unless otherwise noted, are my own. |

| 2 | (Le Cinématographe vu de l’Etna, (Epstein 1974, p. 138)) “[a] pictorial language, like the hieroglyphs of ancient Egypt, whose secrets we have scarcely penetrated yet, about which we do not know all that we do not know ?”. English translation from (Jean Epstein Critical Essays and New Translations, (Epstein 2012, p. 293)). |

| 3 | (Gance 1926, pp. 100–1) “Cinema takes us back to the ideography of primitive writing, to the hieroglyph, by means of a symbol representing each thing, and therein lies probably the greatest force for the future […] Here we are, by a prodigious return, back to the expressive plane of the Egyptians.” |

| 4 | (Ontologie de l’Image Photographique, Bazin 1990, p. 14) “the cinema is objectivity in time […] Now, for the first time, the image of things is likewise the image of their duration, change mummified as it were”. [Translation by Hugh Gray in (Bazin 1960, p. 8)]. |

| 5 | (O’Toole 2018, p. 111) O’Toole suggests that much of the excised footage might have been of Trotsky, in an effort to downplay his role in the events for political reasons. In the final version, Trotsky does appear intermittently but often blends in with his revolutionary cohort and his character is certainly eclipsed by the prominence of others such as Lenin and Kerensky. |

| 6 | (Solkin 2007, p. 1713) (Whitehouse 2016, p. 58) (Williams 1985, p. 3) Solkin gives the date as 1834, while Whitehouse and Williams claim the Sphinxes came to rest in St. Petersburg in 1832. |

| 7 | Amenophis III is another name for Amenhotep III. |

| 8 | “The more it changes, the more it’s the same thing”. |

| 9 | (Régimes d’Historicité. Présentisme et Expériences du Temps, (Hartog 2003, p. 100)) English translation: “[…] juxtaposing, or rather superimposing, two dates not only highlights their difference, their ineluctable noncoincidence, it also establishes relations between them, setting off echoes and producing effects of contamination.” (Regimes of Historicity. Presentism and Experiences of Time, (Hartog 2015, p. 88)). |

| 10 | (Somaini 2016, p. 61) The quotation Somaini uses is taken from Sergei Eisenstein’s notes for his work Metod, also quoted by Naum Kleiman in his introduction to the same. |

| 11 | From personal correspondence with Vera Rumyantseva, archivist at the Eisenstein Archive in Moscow, dated 18 May 2020. |

| 12 | (von Bunsen 1845–1857, p. 20) “[t]he greatest prehistorical fact we encounter here is language.” [Own translation]. |

| 13 | (Brewer and Teeter 1999, p. 11) (Neil Asher Silberman 2012, p. 482) The work on this project began in 1897 but was interrupted by both world wars; thus, at the time that Fechheimer became associated with the Berlin School, research was in full swing. In the post-WWII period work resumed until 1961, and since 1992 the project has been resuscitated as the hybrid digital and hard copy Altägyptisches Wörterbuch. (Schneider 2022, footnote 1). |

| 14 | The First World War saw all German excavation concessions in Egypt withdrawn and all objects housed in the Cairo Museum credited to German excavations were confiscated. (Gertzen 2014, p. 40). |

| 15 | Published in 1914, a second edition was already issued in the same year and a third in 1918. A fourth edition was issued in 1920 with the inclusion of 14 additional plates of artifacts discovered by Ludwig Borchardt at Tel el-Amarna and a fifth followed by the year’s end. A small print run was also done of a French translation by Charlotte Marchand. (Peuckert 2014). |

| 16 | (Die Plastik der Aegypter, Fechheimer 1914) “[…] the best of Egyptian art, which today begins to have an immediate effect” [Own translation]”. |

| 17 | (Die Plastik der Aegypter, Fechheimer 1914, p. 4) “In no other art than Egyptian—at once strict and versatile—is the principle of ‘intégration plastique’ of the modern painters and sculptors fulfilled, or Cézanne’s basic requirement anticipated: ‘Treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone, all put into perspective, that is, each side of an object, of a plane, goes towards a central point. The lines parallel to the horizon give the extent -, … the lines perpendicular to this horizon give the depth.’ The following (Cubist) definition of drawing could be borrowed from the compositional methods of Egyptian artists, who created images in relief: ‘The art of drawing is to determine the relationships between curves and straight lines.’” [Own translation]. |

| 18 | Negerplastik, Einstein (1920, p. 14) English translation: “marked by a pronounced individuation of their parts; […] The parts are oriented, not according to the beholder’s point of view, but from within themselves; they are perceived as confined by mass, not as diminished by distance; as a result, both the individual parts and their contours will be reinforced.” (Negro Sculpture, Einstein 2019, p. 49). |

| 19 | A second printing of 13–17 thousand copies was already issued in 1922 and a third followed in 1923. |

| 20 | In this thesis Worringer states that “Jeder Stil stellte für die Menschheit, die ihn aus ihren psychischen Bedürfnissen heraus schuf, die höchste Beglückung dar. Das muss zum obersten Glaubenssatz aller objektiven kunstgeschichtlichen Betrachtung werden. Was von unserem Standpunkt aus als grösste Verzerrung erscheint, muss für den jeweiligen Produzenten die höchste Schönheit und die Erfüllung seines Kunstwollens gewesen sein. So sind alle Wertungen von unserem Standpunkte, von unserer modernen Aesthetik aus, die ihre Urteile ausschliesslich im Sinne der Antike oder Renaissance fällt, von einem höheren Standpunkt aus Sinnlosigkeiten und Plattheiten. Nach dieser notwendigen Abschweifung kehren wir wieder zu dem Ausgangspunkt, nämlich zu der These von der beschränkten Anwendbarkeit der Einfühlungstheorie, zurück.” (Abstraktion und Einfühlung: ein Beitrag zur Stilpsychologie, Worringer 1921, p. 17). English translation: “Every style represented the maximum bestowal of happiness for the humanity that created it. This must become the supreme dogma of all objective consideration of the history of art. What appears from our standpoint the greatest distortion must have been at the time, for its creator, the highest beauty and the fulfilment of his artistic volition. Thus all valuations made from our standpoint, from the point of view of our modern aesthetics, which passes judgement exclusively in the sense of the Antique or the Renaissance, are from a higher standpoint absurdities and platitudes.” (Abstraction and Empathy: A Contribution to the Psychology of Style, (Worringer 1997, p. 13)). |

| 21 | (Kleinplastik der Ägypter, Fechheimer 1922, p. 17) English translation: “Divided into sparse surfaces, the body draws its austere curve, branching out into the pure bends of the arms that support and carry. The silhouette emphasizes the completed balance of the movement, which does not give in to the famous contrapossto of the Greeks. The artists of the Middle Kingdom understand the summary, the decomposition and binding of the articulated form. They think—entirely un-primitively—a shape to form a column, an ellipse together, without disturbing what is alive.” |

| 22 | (Kleinplastik der Ägypter, Fechheimer 1922, p. 14) English translation: “This figure is more articulated, its partial forms are more sharply separated. As a result, it is rich in different views. Each is a total impression, but well-thought out in the smallest details.” |

| 23 | (Kleinplastik der Ägypter, (Fechheimer 1922, p. 11)) English translation: The imagination thinks in terms of spheres, cylinders, spindles. The three dimensional aspect is so intensified that it is almost impossible to abstract a silhouette. The artists had the gift of very clear, naked form. You feel a volume that the modern constructs.” |

| 24 | (Kleinplastik der Ägypter, (Fechheimer 1922, p. 17)) English translation: “Life processes were to be transferred here […] the unique, lightly fragmented aspect of such a gesture is matured: movement has become a still image, a symbol of existence.” |

| 25 | (Kleinplastik der Ägypter, (Fechheimer 1922, pp. 21–22)) “Among the ancients, the Egyptians animated a type of human who—although entirely Egyptian—nevertheless recalls in gesture and feeling people of all times […] The man who is erected and transformed by himself, who looks completely unpathetic in quiet serenity to the future, unconcerned with unreliable things. The earthly and the eternal are balanced in him, who—imperfect in an imperfect world—does not stand undignified before God. Above a presumptuous mysticism, the compulsion of inherited cults and the helplessness of wild incantations, a lighter religiosity seems to rise, which accepts the existing life and knows death with a calm heart.” |

References

- Allan, Michael. 2008. Deserted Histories: The Lumière Brothers, the pyramids and early film form. Early Popular Visual Culture 6: 159–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazin, André. 1960. The Ontology of the Photographic Image. Film Quarterly 13: 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazin, André. 1990. Ontologie de l’Image Photographique. In Qu’est ce que le Cinema? Edited by André Bazin. Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, Douglas J., and Emily Teeter. 1999. Egypt and the Egyptians. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bru, Sascha. 2018. The European Avant-Gardes, 1905–1935. A Portable Guide. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- von Bunsen, Christian Karl Josias. 1845–1857. Ägyptens Stelle in der Weltgeschichte. 5 vols. Hamburg: Friedrich Perthes, vol. 1.

- Cheng, Joyce. 2009. Immanence out of sight. Formal rigor and ritual function in Carl Einstein’s Negerplastik. Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 55–56: 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, Carl. 1920. Negerplastik. Munich: Kurt Wolff Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, Carl. 2019. Negro Sculpture. In A Mythology of Forms: Selected Writings on Art. Edited by Charles Haxthausen. Translated by Charles Haxthausen. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, pp. 32–59. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein, Sergei. 2010a. Laocoön. In Towards a Theory of Montage. Edited by Michael Glenny and Richard Taylor. Translated by Michael Glenny. London and New York: I.B. Taurus & Co. Ltd., pp. 109–202. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein, Sergei. 2010b. The Dramaturgy of Film Form (The Dialectical Approach to Film Form). In Sergei Eisenstein Writings, 1922–1934. Edited by Richard Taylor. Translated by Richard Taylor. London and New York: I.B. Taurus & Co. Ltd., pp. 161–80. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein, Sergei. 2016. Dynamic Mummification. In Notes for a General History of Cinema. Edited by Naum Kleiman and Antonio Somaini. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 119–206. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Jean. 1974. Le Cinématographe vu de l’Etna. In Écrits dur le Conéma 1921–1953. Paris: Seghers, vol. 1, pp. 131–69. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Jean. 2012. Jean Epstein Critical Essays and New Translations. Edited by Sarah Keller and Jason Paul. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fechheimer, Hedwig. 1914. Die Plastik der Aegypter. Berlin: Cassirer. [Google Scholar]

- Fechheimer, Hedwig. 1922. Kleinplastik der Ägypter. Berlin: Bruno Cassirer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Gance, Abel. 1926. Le temps de l’image est venu! L’Art Cinématographique 2: 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Gertzen, Thomas L. 2014. The Anglo-Saxon Branch of the Berlin School. In Histories of Egyptology: Interdisciplinary Measures. Edited by William Carruthers. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hartog, François. 2003. Régimes d’Historicité. Présentisme et Expériences du Temps. Paris: Éditions du Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Hartog, François. 2015. Regimes of Historicity. Presentism and Experiences of Time. Translated by Saskia Brown. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kozloff, Arielle. 2012. Amenhotep III: Egypt’s Radiant Pharaoh. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lant, Antonia. 1992. The Curse of the Pharaoh, or How Cinema Contracted Egyptomania. October 59: 86–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lant, Antonia. 1995. Haptical Cinema. October (MIT Press) 74: 45–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemberg, Margret. 1997. Einleitung: Die ersten Frauen an der Universität Marburg. In Es begann vor hundert Jahren. Die ersten Frauen an der Universität Marburg und die Studentinnenvereinigungen bis zur “Gleichscahltung” im Jahre 1934. Marburg: Schriften der Universitätsbibliothek Marburg, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Marchand, Suzanne L. 2009. German Orientalism in the Age of Empire: Religion, Race, and Scholarship. Washington, DC, Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo and Delhi: German Historical Institute and Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1993. Cézanne’s Doubt. In The Merleau-Ponty Aesthetics Reader: Philosophy and Painting. Edited by Michael B. Smith. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, pp. 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Michelson, Annette. 1973. Camera Lucida/Camera Obscura. Artforum 11: 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1968. The Will to Power. Edited by W. Kaufmann. Translated by Walter Kaufmann, and Reginald John Hollingdale. New York: Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole, Michael. 2018. Eisenstein in October. In The Hermeneutic Spiral and Interpretation in Literature and the Visual Arts. New York and Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 109–14. [Google Scholar]

- Peuckert, Sylvia. 2014. Hedwig Fechheimer und die ägyptische Kunst: Leben und Werk einer jüdischen Kunstwissenschaftlerin in Deutschland. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Peuckert, Sylvia. 2017. Überlegungen zu Heinrich Schäfers ‘Von ägyptischer Kunst’ und zu Hedwig Fechheimers ‘Plastik der Aegypter’. Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache (De Gruyter) 144: 108–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, Kevin. 2011. Terror and Greatness: Ivan and Peter as Russian Myths. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Thomas. 2022. Hermann Grapow, Egyptology, and National Socialist Initiatives for the Humanities. In Betrayal of the Humanities: The University During the Third Reich. Edited by Bernard M. Levinson and Robert P. Ericksen. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Silberman, Neil Asher. 2012. The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, 2nd ed. 3 vols. Oxford, New York, Auckland, Cape Town, Dar es Salaam, Hong Kong, Karachi, Kuala Lumpur, Madrid, Melbourne, Mexico City, Nairobi, New Delhi, Shanghai, Taipei and Toronto: Oxford University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Solkin, Victor. 2007. The Sphinxes of Amenhotep III. in St. Petersburg: Unique Monuments and their Restoration. Edited by Jean-Claude Goyon and Christine Cardin. In Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta. Proceedings of the Ninth International Congress of Egyptologists. Grenoble: Uitgeverij Peeters & Departement Oosterse Studies, pp. 1713–920. [Google Scholar]

- Somaini, Antonio. 2016. Cinema as “Dynamic Mummification” and History as Montage: Eisenstein’s Media Archaeology. In Sergei M. Eisenstein: Notes for a General History of Cinema. Edited by Naum Kleiman and Antonio Somaini. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 19–105. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Richard. 2004. Sergei Eisenstein: The Life and Times of A Boy from Riga. The Montage Principle. Eisenstein in New Critical Contexts 21: 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, Tom. 2006. Snakes, Skins and the Sphinx: Nietzsche’s Ecdysis. Journal of Visual Culture 5: 365–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehouse, Helen. 2016. Egypt in the Snow. In Imhotep Today: Egyptianizing Architecture. Edited by Jean-Marcel Humbert and Clifford Price. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Edward. 1985. Voices of Ancient Trumpets. In The Bells of Russia. Edited by Edward Williams. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Worringer, Wilhelm. 1921. Abstraktion und Einfühlung: Ein Beitrag zur Stilpsychologie. Munich: R. Piper & Co. Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Worringer, Wilhelm. 1997. Abstraction and Empathy: A Contribution to the Psychology of Style. Edited by Hilton Kramer. Translated by Michael Bullock. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).