Abstract

Digital twin (DT) is increasingly adopted in the architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) sector to support data-driven modeling, monitoring, and decision-making across the building lifecycle. While Artificial Intelligence (AI) applications in DT have increased rapidly, existing studies remain fragmented, largely task-specific, and weakly integrated into holistic DT frameworks. A comprehensive analysis of the current applications, challenges, and future opportunities is vital for advancing the use of DT in this domain. Guided by three key research questions, this study employs a science mapping methodology to review the application of AI in DT, analyzing 316 publications from 2015 to 2025. The research highlights the most influential journals, countries, and authors, and through a keyword co-occurrence analysis, identifies five emerging research areas. The paper discusses the current implementations and limitations of AI within the realm of DT and offers recommendations for future development. By clarifying the evolving role of AI in DT development, this study provides an up-to-date synthesis of the field and offers structured insights to support the advancement of intelligent, scalable DT applications in the built environment.

1. Introduction

Digital twin (DT) is increasingly adopted in the architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) sector to support real-time monitoring, simulation, and data-driven decision-making across the building lifecycle. As a major contributor to national economies, accounting for approximately 8–10% of gross domestic product in many countries [1], the AEC sector faces growing pressure to improve productivity, coordination, and operational efficiency through digital transformation. However, compared with manufacturing and automotive industries, the adoption of advanced digital technologies in AEC has been relatively slow, largely due to fragmented workflows, heterogeneous data sources, and complex regulatory environments [2,3,4].

DT has emerged as a promising approach to addressing these challenges by enabling continuous data exchange between physical assets and their virtual representations. Originating from the concept of “mirrored spaces” proposed by Grieves in the context of product lifecycle management [5], DTs have evolved into integrated virtual–physical systems that combine models, sensor data, and analytical capabilities to monitor, simulate, and predict asset behavior throughout their lifecycle [6,7,8,9]. In the AEC domain, DT is increasingly used to support project coordination, real-time performance monitoring, and operational management by integrating building models with data from the Internet of Things (IoT), unmanned aerial vehicles, and other sensing technologies [10,11,12].

Despite these advances, the growing scale, heterogeneity, and real-time nature of building data have exposed the limitations of conventional DT implementations that primarily rely on data integration and rule-based simulation. To address this gap, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has been progressively integrated into DT frameworks to enhance data interpretation, prediction, and decision support. Through machine learning, deep learning, and data-driven analytics, AI-enabled DTs can transform real-time and historical data into actionable insights for forecasting, building performance, optimizing operations, and supporting proactive management [11,13]. Visualization technologies such as augmented and virtual reality (VR) further enhance the interpretability of DT outputs and facilitate human–DT interaction in design, construction, and operation stages [14,15,16].

In this study, an AI-enabled DT is defined as a DT system in which AI functions as an embedded intelligence layer that enables learning, reasoning, and interaction across the physical–virtual feedback loop. Existing AI-enabled DT research in the AEC sector can be broadly categorized into two paradigms. The first paradigm focuses on prediction-oriented AI, where machine learning and deep learning models are embedded within DT to forecast building operational states, such as energy consumption, equipment performance, and environmental conditions. The second paradigm emphasizes large language model (LLM)–driven AI agents, which serve as intelligent interfaces between users and DT systems by enabling natural language interaction, automated model generation, and task-oriented assistance. Together, these paradigms extend DTs from data integration and simulation tools toward intelligent, predictive, and user-centered platforms.

Although AI-enabled DT has received increasing attention in both academia and industry, its application in the AEC sector remains fragmented and uneven. Existing reviews primarily focus on DT frameworks, building simulation, and the integration of building information model (BIM) and IoT, with limited systematic analysis of AI integration from a paradigm-level perspective [17]. In particular, the complementary roles of prediction-oriented AI for operational forecasting and LLM-based approaches for intelligent and collaborative DT usage have not been sufficiently synthesized.

To address the gap, this paper conducts an extensive review to investigate existing knowledge and future directions regarding the utilization of AI to advance DT framework implementation. A new approach is proposed by utilizing science mapping to explore the applications, challenges, and future directions of AI in DT development. Bibliometric analysis is one of the important research methods to estimate the academic literature because it can uncover nuances in the evolution of the research field, revealing emerging areas of the research field, which provides a unique perspective for the literature review [18]. The paper solves the key research questions below to advance knowledge and guide future research, thereby enhancing prediction and automation in smart building and construction. To achieve the goal, three research aims (RQs) were formulated:

RQ1. Which journals, countries, and authors have made significant contributions to AI applications in DT within the AEC sector, and what are their interrelationships?

RQ2. What are the main application paradigms and technical approaches of AI integration within DT systems in the AEC sector?

RQ3. What is the status quo, limitations, and future research directions for AI-enabled DT applications in the AEC sector?

This study provides a paradigm-level review of AI-enabled DT research in the AEC sector, conceptualizing AI as an embedded intelligence layer rather than an auxiliary tool. Existing studies are synthesized by distinguishing between prediction-oriented AI approaches for operational forecasting and optimization, and LLM–driven AI agents that enable intelligent, interactive, and collaborative DT use. Through comparative analysis of AI techniques, data sources, application contexts, and implementation maturity across AEC domains, the review elucidates how AI integration shifts DTs from data-centric simulation toward intelligent, human-centered decision support. On this basis, the paper identifies key research gaps and outlines future directions for scalable, interoperable, and user-oriented AI-enabled DT development.

Moreover, the remainder of the article is organized as follows: The research method for this investigation is described in Section 2. The bibliometric study of DT applications in AEC-related research is introduced in Section 3. Section 4 presents the AI application for DT in the AEC. Section 5 discusses the recommendations for further research and limitations. Section 6 summarizes the current trends and major challenges in applying DT in the construction domain.

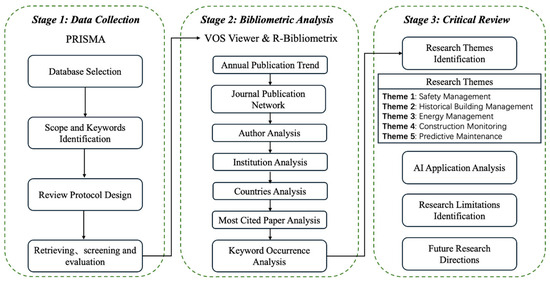

2. Methodology

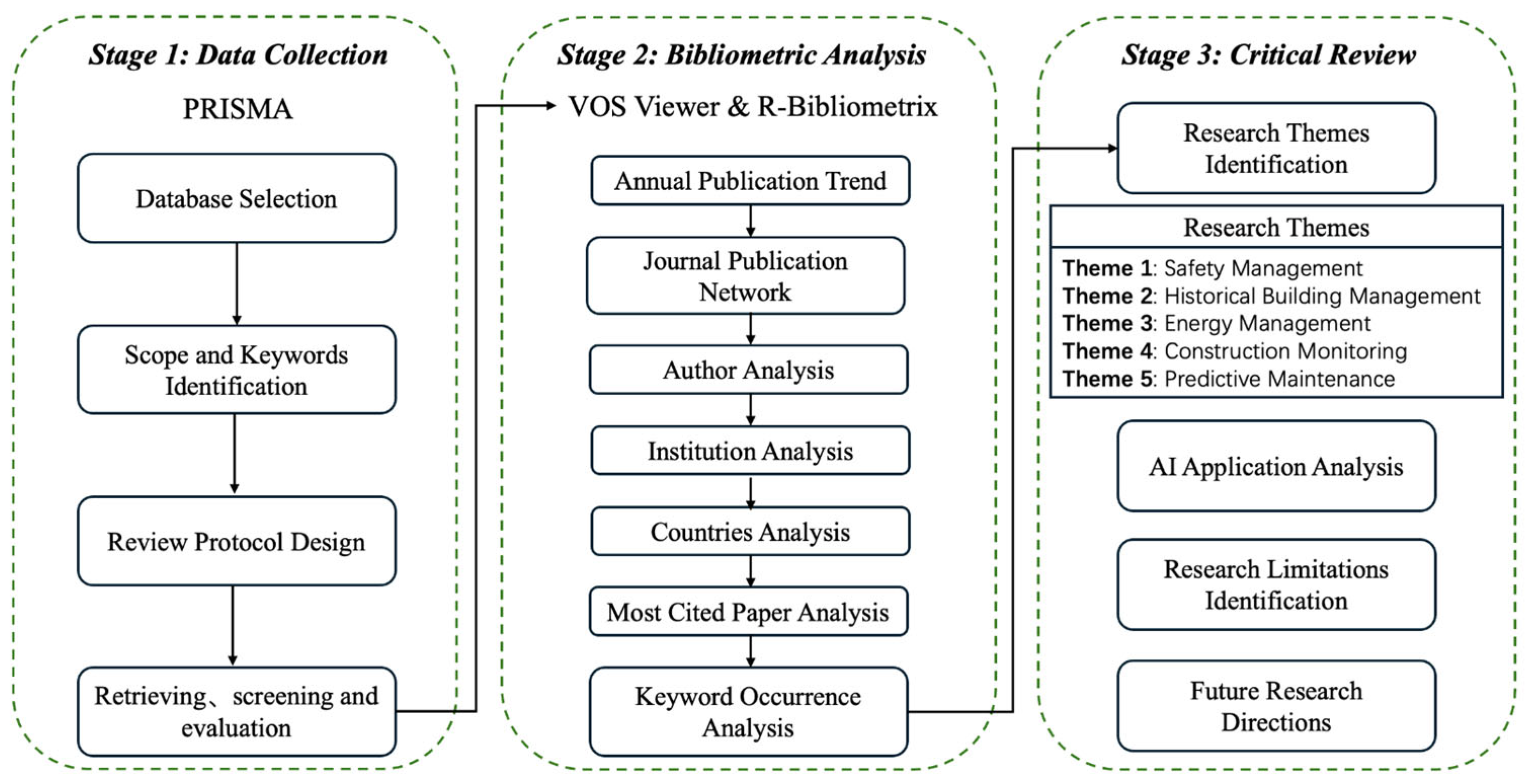

This research adopts a comprehensive three-phase methodological approach, utilizing the PRISMA framework to systematically review the literature on AI applications in DT (Figure 1). The methodology begins with Data Collection, where relevant research articles are retrieved from the Web of Science and Scopus databases. In the bibliometric analysis phase, bibliometric analyses are performed using VOS Viewer and R-Bibliometric to quantify trends, visualize relationships, and assess the impact of key studies. The study employs a science mapping approach, combining both qualitative and quantitative methods, including bibliometric searches and bibliometric analysis [19]. The third phase, the Critical Review, provides an in-depth discussion of the findings. Based on keyword clustering analysis from VOS Viewer, five major research themes related to DT in the AEC sector are identified, and the application of AI in DT is analyzed. The review concludes by discussing the limitations and proposing future research directions.

Figure 1.

Overall flow of the research methodology framework.

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Search criteria are established to include studies within the review scope (as shown in Table 1). First, the temporal scope is set to the last 10 years, up to the beginning of this study (i.e., from 2015 to December 2025). The search query consisted of three sets of keywords: (1) DT-related keywords: “digital twin”, “virtual twin”, “cyber-physical system”, “digital replica”, “Hybrid Twin”; (2) Keywords representing Construction domain: “construction”, “AEC”, “building”, “BIM”; and (3) auxiliary keywords representing AI: “Artificial Intelligence”, “large language model”, “machine learning”, “deep learning”, “ANN”, “deep reinforcement learning”, “computer vision”. In addition, journal publications are included in the search criteria, and the language of research papers was limited to English.

Table 1.

Search criteria for review of the AI application in DT.

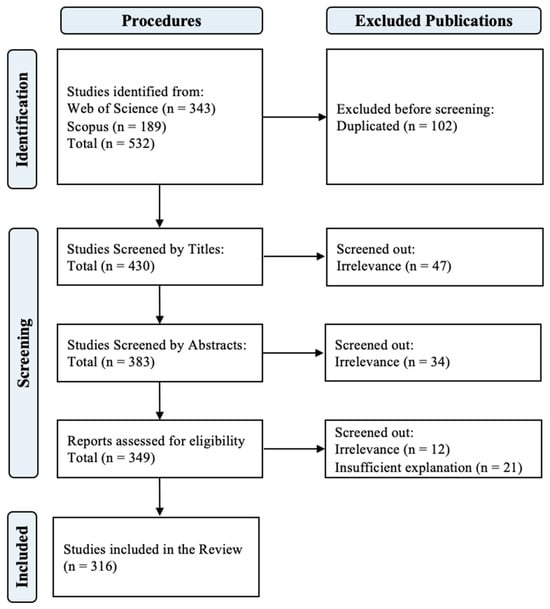

2.2. The Literature Search Program

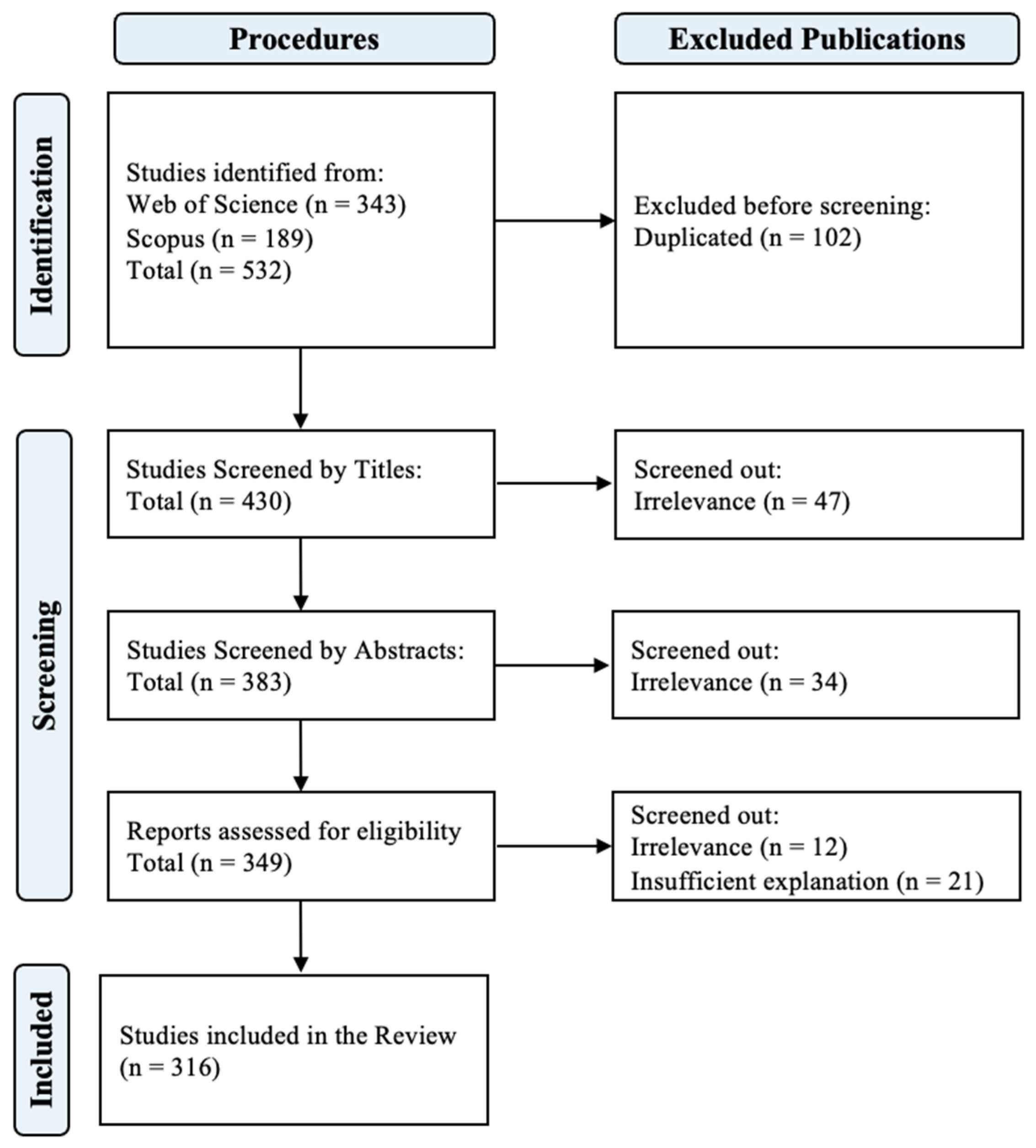

Following the criteria determined above, this work collects and screens the literature using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) procedure, as shown in Figure 2. The detailed description of the PRISMA checklist is provided in the Supplementary Materials (Supplementary_checklist). Then, 316 publications published from 2015 to 2025 December are selected and considered for this work.

Figure 2.

The literature search program based on PRISMA.

2.3. Data Visualization

This study uses VOSviewer for bibliometric analysis, data visualization, and clustering based on correlations to map the knowledge domain of DT research [20,21]. R-Bibliometrix (version 5.2.1) is also employed to enhance the analysis by combining its capabilities with VOSviewer for more comprehensive visual data representation [22]. VOSviewer, widely used in the quantitative literature reviews, creates distance-based visualizations that reveal interrelationships among publications, authors, journals, institutions, countries, keywords, and co-citation patterns [23]. In this stage, bibliometric data from plain text files are imported into VOSviewer (version 1.6.20) and analyzed within the R environment. The results are detailed in Section 3, including key visualizations such as network analysis charts, histograms, and bar charts, which support the explanatory analysis. This section presents descriptive statistics and the co-citation analysis of references, authors, and journals in the DT research field. Additionally, evolutionary analysis is conducted using VOSviewer’s keyword co-occurrence analysis to track the progression of DT research.

3. Results

The summary table was developed to synthesize key dimensions of AI-enabled DT research in the AEC sector, including application domains, primary DT objectives, and typical data sources. The synthesis is based on all 316 studies included in the PRISMA flow diagram, and representative references are explicitly cited in the table and main text. The full list of these publications is provided in the Supplementary Materials (Supplementary_publications). Table 2 summarizes study characteristics at the application-domain level, and more detailed discussions of AI techniques and DT integration modes are presented in Section 3.2 and Section 4.

Table 2.

Application-domain characteristics of AI-enabled DT studies in the AEC sector.

3.1. Scientometric Analysis Results

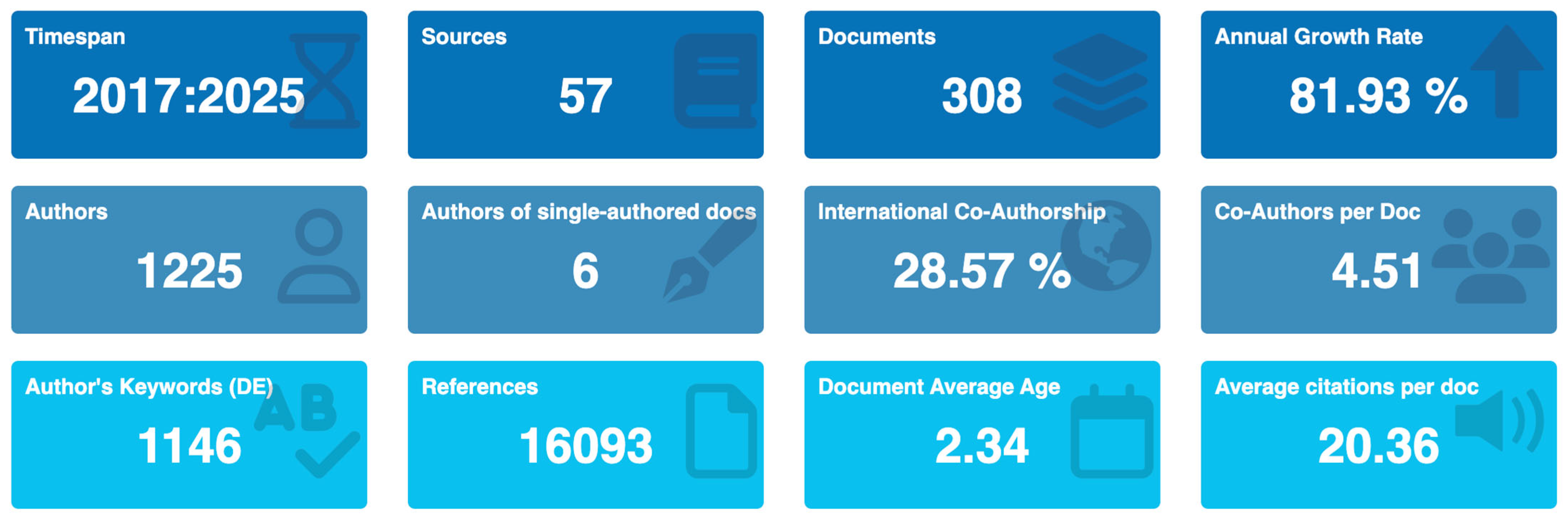

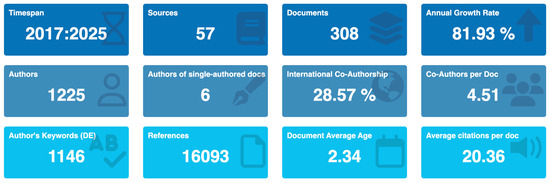

Figure 3 provides an overview of the bibliometric characteristics of AI-enabled DT research in the AEC sector. Following systematic searching and screening using the R-Bibliometrix framework, 316 journal articles published between 2017 and 2025 were retained for analysis. Although the initial search window began in 2015, Figure 3 clearly indicates that substantive research activity only emerged after 2017. The exceptionally high annual growth rate of 81.93% further underscores the accelerated expansion of this research field. This rapid growth can be attributed to several reinforcing factors, including the increasing availability of building sensor data, growing industry demand for intelligent operation and maintenance solutions, and recent advances in machine learning and deep learning techniques. In addition, the low average document age (1.34 years) shown in Figure 3 reveals that the literature remains relatively young and rapidly evolving, implying that research themes, methodological approaches, and application scenarios are still in a formative stage. These indicators highlight that AI-enabled DT has transitioned from an emerging concept to a fast-growing research frontier within the AEC sector.

Figure 3.

General Information on the publications on AI applications in DT.

3.1.1. Annual Publication Trend and Journal Publication Analysis

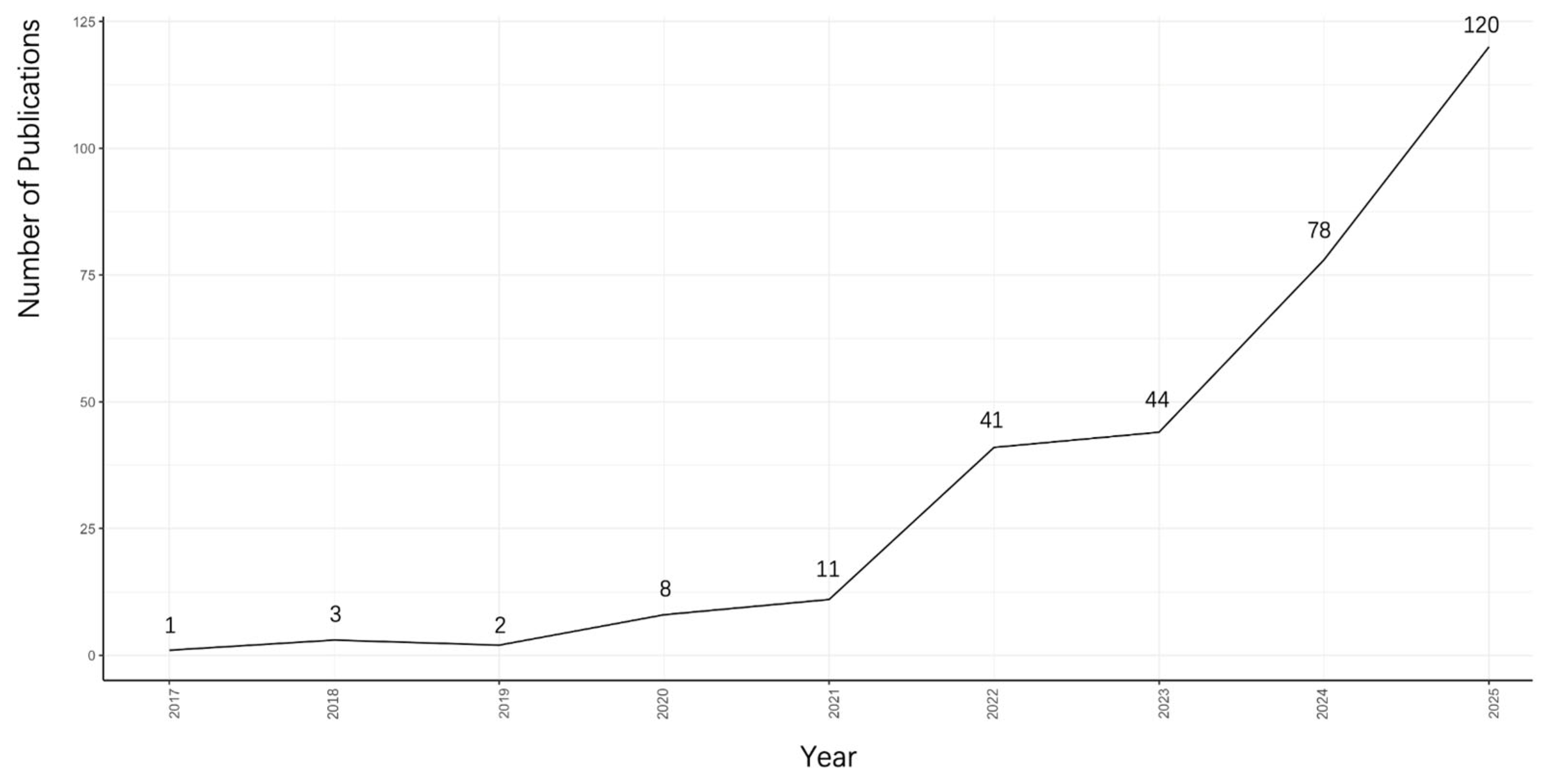

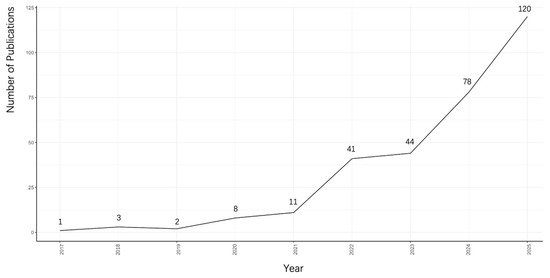

Figure 4 illustrates the publication trend on AI-enabled DT research in the AEC domain between 2017 and 2025. As shown in the figure, the annual number of publications remains relatively low and stable prior to 2020. A pronounced inflection point is observed after 2021, followed by a rapid increase in publication output, culminating in 120 articles in 2025. This acceleration indicates that AI-enabled DT research has transitioned from an emerging topic to a rapidly expanding research stream. The sharp growth observed after 2021 can be attributed to the increasing maturity of building-scale DT platforms, the widespread deployment of IoT sensing infrastructure, and recent advances in data-driven AI techniques that can handle complex, high-frequency building data.

Figure 4.

Publication Trend of AI Applications in DT (2017 to 2025 December).

In addition to temporal growth, journal-level analysis (Table 3) reveals distinct patterns in terms of research productivity and scholarly impact, summarizing the number of publications (NP), total citations (TC), average citations (AC), total link strength (TLS), and the start year of publication (SYP). The 316 publications are distributed across 57 journals, indicating a relatively dispersed publication landscape. By applying a threshold of at least 5 publications and 50 citations per journal, 11 journals were identified as core outlets in this field. Among them, Automation in Construction, Buildings, and Sensors exhibit the highest publication volumes, highlighting their central role in disseminating AI-enabled DT research within the AEC domain. However, publication volume does not directly correspond to citation impact. While Automation in Construction ranks first in both number of publications and total citations, Sensors achieves a higher total citation count than Buildings despite a comparable number of articles. In contrast, the IEEE Internet of Things Journal demonstrates the highest average citations per article, despite a relatively smaller publication volume. This indicates that journals with a stronger focus on data infrastructure and AI methodologies tend to attract higher per-article impact. These patterns reflect a broader global research trend in which domain-specific AEC journals emphasize applied, building-oriented DT implementations, whereas technology-oriented journals contribute fewer but more highly cited methodological studies.

Table 3.

Most impactful Journals of DT and AI in the AEC Field.

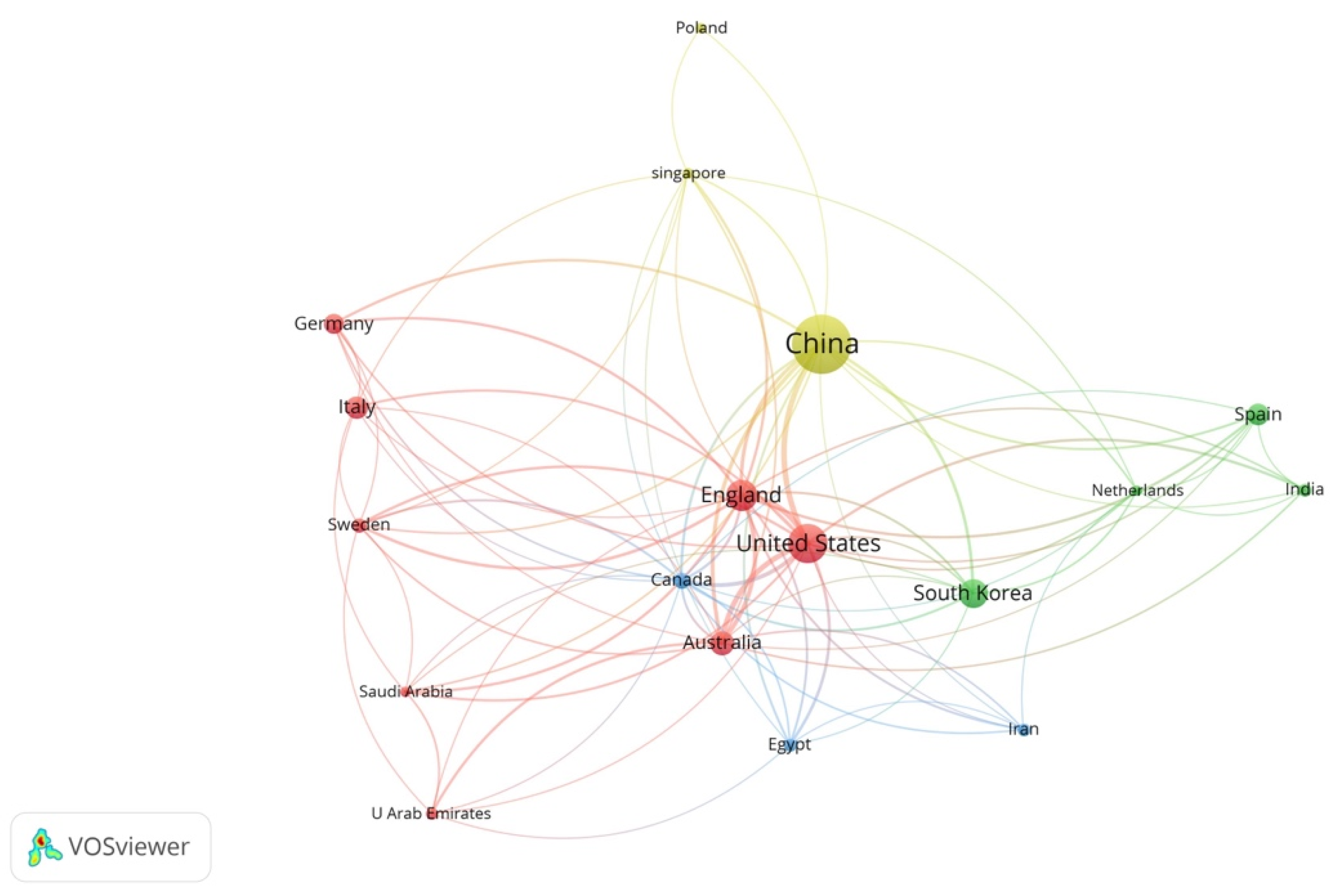

3.1.2. Science Mapping of Countries and Affiliations

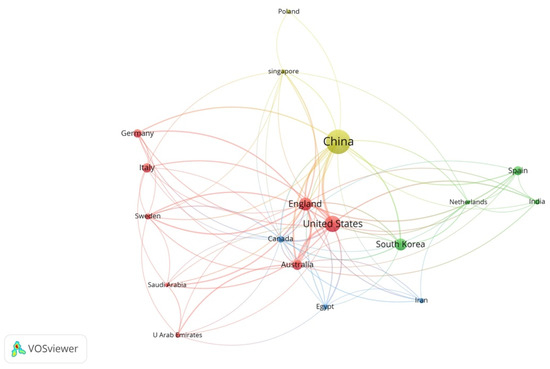

Figure 5 visualizes the international science mapping of countries contributing to AI-enabled DT research in the AEC sector. To ensure analytical robustness, countries with at least 4 publications and 30 citations were included, resulting in 20 representative countries out of the 55 identified. The resulting network highlights both research productivity and the structural patterns of international knowledge exchange [27]. The distribution of publications is highly uneven. China is the most prolific contributor (124 publications), followed by the United States (53) and England (35). While China leads in total output, the United States exhibits the highest average citations per paper (36), followed by England, Australia, and Germany.

Figure 5.

Science mapping of countries.

The clustering structure further reveals structured collaboration patterns based on mutual citation frequency. Seven distinct country clusters are identified, with China, Poland, and Singapore forming a closely connected cluster. This clustering reflects a complementary research dynamic in which Singapore’s methodological advances in DT and smart building analytics are frequently operationalized through application-driven studies supported by China’s extensive pilot projects. In addition, the United States, England, Australia, and European countries function as central bridging nodes, maintaining dense citation links across multiple clusters, highlighting their intermediary role in disseminating methodological advances and shaping global research agendas in AI-enabled DT research.

3.1.3. Most Cited Publications

Table 4 summarizes the five most-cited journal articles in the AI-enabled DT literature within the AEC domain, detailing their publication year (PY), document type, total citations, and publication outlets. These highly cited papers were published between 2020 and 2022, indicating that foundational contributions to this field have emerged relatively recently and have rapidly accumulated scholarly attention. A notable pattern is that the four most-cited papers adopt a case study–based research design, highlighting the critical role of real-world implementations. These studies primarily focus on large-scale or system-level applications, such as campus-scale DT, blockchain-enabled information sharing, supply chain coordination, and real-time safety monitoring, demonstrating the field’s strong orientation toward applied and practice-driven innovation [69]. Collectively, the top five articles account for 846 citations, representing approximately 27.3% of the total citations in the dataset. The distribution of these influential papers across multiple leading journals, including Journal of Management in Engineering, Automation in Construction, Buildings, and Applied Sciences, reflects the interdisciplinary nature of AI-enabled DT research, spanning construction management, building science, and digital technologies.

Table 4.

Top 5 most-cited publications.

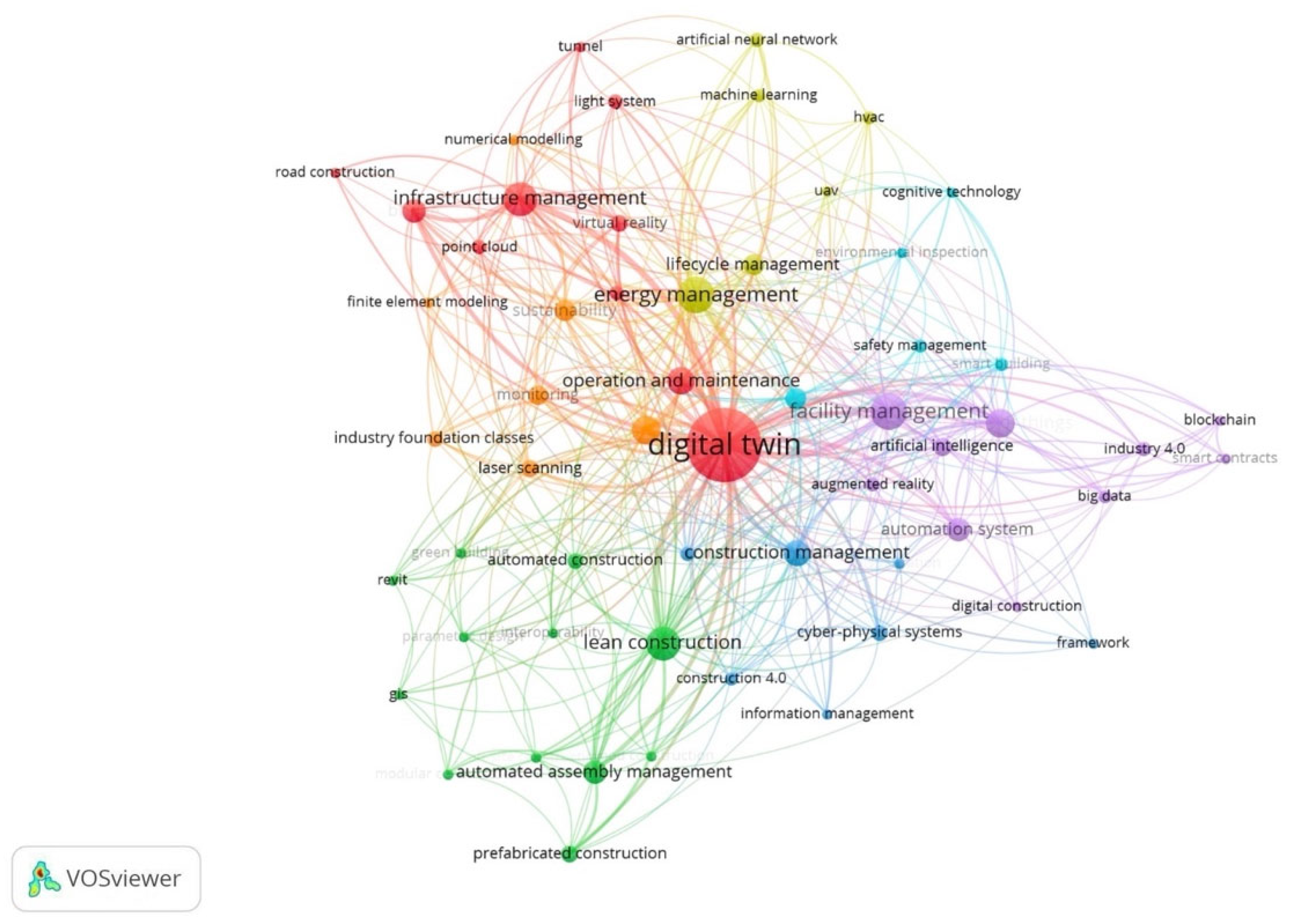

3.1.4. Keywords Co-Occurrence Analysis

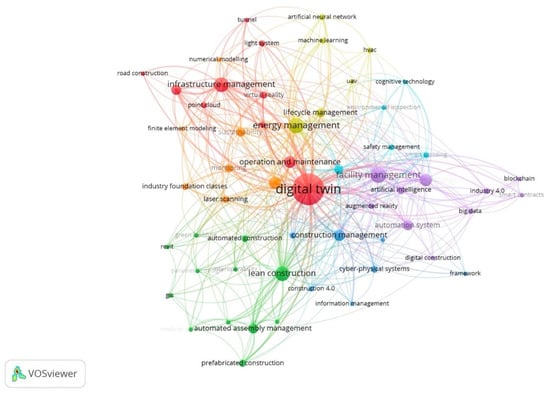

Keywords play a critical role in revealing the research focus and thematic structure of a scientific field [20]. To gain a deeper understanding of current research trends and relationships, a keyword co-occurrence network was constructed by inputting bibliometric data into VOSviewer. The co-occurrence map reveals that 59 high-frequency keywords were identified from 1961 extracted keywords after threshold filtering (Figure 6). The node size represents the frequency of keyword occurrence, while the thickness of links indicates the strength of co-occurrence, reflecting the degree of conceptual association between research topics. The spatial proximity of keywords further illustrates their thematic relatedness and reveals several interconnected research clusters organized around the central concept of the DT.

Figure 6.

Keywords co-occurrence network of AI applications in DT.

The keyword “digital twin” occupies a dominant central position in the network and exhibits the strongest connections with nearly all other keywords, highlighting its role as a core integrative framework for applying AI across the building lifecycle. The keyword co-occurrence network reveals several closely related research directions organized around the central concept of the DT. In the upper-right region, keywords related to safety management, including safety management, environmental inspection, cognitive technology, and machine learning, are strongly interconnected, indicating a growing emphasis on real-time hazard identification, behavior recognition, and proactive risk mitigation enabled by AI-enabled DT platforms. This reflects the increasing use of DT to enhance construction and operational safety through continuous situational awareness and predictive analytics. On the left side of the network, clusters dominated by keywords such as infrastructure management, historical building, laser scanning, point cloud, finite element modeling, and numerical modeling highlight applications in infrastructure and heritage asset management. The dense connections among these terms suggest that AI-enhanced DT are widely used to integrate heterogeneous data sources for structural condition assessment, performance evaluation, and long-term conservation of existing and aging assets. Closely related to this area, energy-focused keywords including energy management, Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC), artificial neural network, machine learning, and lifecycle management form a coherent research direction, demonstrating that data-driven DT are extensively adopted for energy optimization, demand forecasting, and intelligent control throughout the building lifecycle, thereby supporting sustainability objectives. In the lower region of the network, keywords such as construction management, real-time monitoring, cyber-physical systems, augmented reality (AR), visualization, and automation systems indicate a strong focus on construction-phase applications, where DT serve as real-time decision-support tools by linking physical site data with virtual models to enable dynamic monitoring, progress tracking, and process control. Adjacent to the safety-related area, keywords associated with facility management, big data, IoT, blockchain, and smart contracts represent operation and maintenance applications, emphasizing the role of AI-enabled DT in asset performance monitoring, fault diagnosis, and maintenance scheduling. The integration of IoT and advanced data analytics enables a shift from reactive maintenance toward predictive and prescriptive maintenance strategies. Overall, the co-occurrence analysis demonstrates that AI-based DT research in the AEC domain is highly application-oriented and spans the entire building lifecycle, forming an integrated thematic structure that underpins the major application areas discussed in the following section.

3.2. Themes and Application Areas

Through a systematic review of the 316 papers, DT has shown significant advantages in five domains: (i) safety management, (ii) historical building management, (iii) energy management, (iv) construction real-time monitoring control, and (v) predictive maintenance. Table 5 presents the quantitative measurement of the actual keywords as found in the publications related to DT.

Table 5.

Details of keywords related to AI application in DT.

3.2.1. Safety Management

DT plays a pivotal role in building safety management by enhancing the capability to prevent and respond to disasters, which is achieved through the integration of diverse data sources, disaster risk prediction, and the assessment of structural health post-disaster [24,25]. DT helps simulate and evaluate construction disaster scenarios, making safety inspections more efficient. It also provides real-time visual warnings and predicts potential hazards at construction sites by integrating technologies such as deep learning and mixed reality [26,27]. Furthermore, in complex building interiors where manual assessments can be difficult and hazardous, DT offers a more accurate and detailed representation of the space, which greatly enhances personnel safety [28]. Additionally, DT assists in data modeling, evaluating structural performance, and monitoring building health, thereby supporting the reconstruction process [29,30].

While substantial progress has been made in applying DT to safety management, its current development is still largely confined to isolated tasks. Future efforts should focus on integrating existing technologies more effectively and developing more robust DT models capable of addressing complex environments, with the goal of reducing the impact of disasters on buildings [31].

3.2.2. Historical Building Management

DT plays a key role in historical building conservation, restoration, and virtual reconstruction [32]. The research focuses on two main areas: (1) preventive maintenance of heritage buildings through case studies; (2) digital management of heritage building information [32,33,34].

DT frameworks use various digital technologies to detect risks and enable predictive maintenance by monitoring changes and real-time conditions [35]. For instance, a DT-based ventilation system for underground heritage buildings was developed, integrating computational fluid dynamics and IoT to control humidity. Additionally, DT has been applied for quasi-static analysis, combining BIM and finite element analysis to create a more accurate model for real-time historic building control. Moreover, DT also plays a vital role in recording historical building lifecycle data, preventing information loss, and enhancing preservation and dissemination [36]. For example, laser scanning, photogrammetry, and archival research have been integrated into building models, using point cloud data for heritage building classification on the DT framework [37]. In summary, DT offers a novel solution for heritage conservation, promotes preventive maintenance, and aids in processing Heritage Building Information Modeling (HBIM) data. Future research could integrate more operational data into the DT framework for improved decision-making and further enhance the storage and retrieval of heritage information.

3.2.3. Energy Management

DT is transforming energy management by enabling energy monitoring, optimizing control systems, and proposing automated energy-saving strategies [38]. Studies have demonstrated the use of DT with machine learning for predictive monitoring of energy consumption and carbon emissions, and the application of multi-source datasets and Bayesian optimization to calibrate building simulation models, helping reduce greenhouse gas emissions [39,40]. Additionally, DT frameworks integrated with remote sensing technology have been used to estimate carbon reduction potential in residential areas during the operational phase [41]. It has been employed to simulate building structures and thermal systems to achieve optimal design solutions, including the design of thermal systems for lightweight roofs and the optimization of building-integrated solar chimneys using a DT model [42,43]. However, the widespread adoption of DT in energy management remains hindered by data-related challenges, particularly issues with data format compatibility. Further research is needed to optimize energy management models for improved decision-making [44].

3.2.4. Construction Real-Time Monitoring Control

DT is transforming construction management by enabling real-time monitoring and decision-making through integrated IoT and BIM data [58]. Studies have demonstrated that combining DT with AR, AI, and supply chain management enhances operational accuracy and safety on construction sites [46,47]. Additionally, the use of advanced controls and accurate detection systems enables automated progress monitoring, highlighting the positive impact of integrating BIM, IoT, and DT on construction management performance [48]. However, large-scale projects present significant challenges in effectively collecting, integrating, and applying sensor data into DT models for analysis, diagnosis, and decision-making [49,50].

To address these challenges, real-time monitoring can be more effectively and accurately achieved through prefabricated building assembly. Over recent years, DT has shown significant advantages over traditional on-site construction methods by automating the assembly process and enhancing the design of construction programs, assembly path planning, and quality control [51]. Furthermore, DT enables real-time synchronization, facilitating planning, scheduling, and execution of prefabricated assemblies [52]. The integration of IoT, BIM, and Geographic Information System (GIS) within a DT framework supports real-time logistics simulation, enabling the assessment of logistical risks and delivery timelines [53]. Additionally, BIM and IoT within a DT framework aid in planning lifting routes, while long-range radio technology (LoRA) is employed for data collection and monitoring precast movement status [54].

3.2.5. Predictive Maintenance

DT has been widely applied in facility management during the operations and maintenance phase, streamlining tasks such as routine equipment maintenance, real-time equipment status monitoring, and providing remote access and control [57]. However, there is still a lack of a structural framework and model to further link the relationship between DT and the identified influencing factors [58]. The application of visualization tools has been summarized to explain how real-time data updates help managers make informed decisions and automatically propose recommendations [59]. Predictive maintenance systems [60] and machine learning algorithms [61] have significantly supported facility managers in their daily tasks, while contributing to reducing facility failures and improving maintenance quality.

In addition, DT is increasingly applied in infrastructure management [62], with a DT framework for structure inspection, enabling predictive maintenance. For instance, the fatigue life of steel bridges based on different cracks has been predicted [63]. Road and infrastructure damage has been predicted using Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)-acquired data and machine learning modeling, achieving high Mean Average Precision (mAP) values of 95.12% [64]. Additionally, a 6D BIM model based on DT has been developed for the lifecycle management of railway turnout systems, simulating lifecycle management and calculating carbon emissions [65].

DT not only demonstrates immense potential in areas such as building safety, historical building preservation, and energy management, but also plays a crucial role in construction, real-time monitoring, control, and predictive maintenance, driving the AEC industry towards greater intelligence and automation. However, challenges such as complex modeling and large data volumes remain, and issues related to data integration and processing continue to constrain the development of the DT framework. Therefore, the application of AI in DT can greatly address problems related to data processing, prediction, and platform usability.

3.2.6. Cross-Domain Comparison

A cross-domain comparison reveals clear differences in the maturity and depth of AI integration within DT applications. As shown in Table 6, variations in high-frequency keywords and clustering results reflect different application emphases and levels of technological maturity across the five domains. Among them, energy management exhibits the most advanced AI adoption, with mature applications of machine learning, artificial neural networks, and optimization algorithms for energy prediction, system calibration, and intelligent control. These applications are supported by relatively standardized and continuous data streams, which facilitate scalable and data-driven DT implementations. Predictive maintenance also demonstrates a high level of AI integration, particularly in facility and infrastructure management, where machine learning-based fault diagnosis and lifecycle prediction models are increasingly applied. However, the development of unified DT frameworks that can effectively integrate heterogeneous data across lifecycle stages remains a challenge.

Table 6.

Comparative analysis of AI-enabled DT applications across domains.

In contrast, historical building management shows a lower level of AI maturity. While DT is widely used for documentation, visualization, and structural analysis, AI applications are mainly limited to classification and simulation tasks. This is largely due to the lack of real-time operational data and the high complexity of heritage modeling. Safety management and construction real-time monitoring control represent an intermediate level of maturity. These domains benefit from advances in computer vision, IoT, and real-time data acquisition, enabling applications such as hazard detection, progress monitoring, and automated inspection. Nevertheless, existing implementations are often task-oriented and lack comprehensive system-level integration within DT platforms.

Overall, the comparison suggests that domains with continuous and high-quality data availability, such as energy management and predictive maintenance, tend to achieve deeper AI integration and higher implementation maturity. In contrast, data limitations, modeling complexity, and interoperability issues continue to constrain AI adoption in historical building management and large-scale construction environments. These findings highlight the need for future research to strengthen cross-domain data integration, develop scalable DT architectures, and enhance the adaptability of AI-enabled DT systems across different application contexts.

4. AI Applications in DT

Currently, the application of AI in the DT domain primarily focuses on two key areas: (i) integrating AI to predict building operational data within the DT framework; (ii) leveraging LLM to develop AI agents that assist non-experts in using the DT framework for collaborative tasks. These approaches aim to optimize building management and enhance the usability and functionality of DT systems through advanced AI-enabled techniques.

4.1. AI Integration for Building Data Prediction in Digital Twin

AI algorithms, including deep learning, convolutional neural network (CNN), and graph neural network (GNN), have been widely integrated into DT-enabled smart building systems to optimize environmental conditions and operational performance. Existing studies demonstrate that AI plays a central role in smart building operation and management, supporting tasks such as energy consumption prediction [45], load forecasting [66], optimization control [55], and indoor thermal environment regulation [67].

Beyond application domains, prior research reveals relatively consistent technical patterns for AI integration within DT systems. From a system architecture perspective, AI models are typically embedded in the data analytics layer, functioning as the core intelligence that transforms raw sensing data into decision-support outputs. In terms of model selection, deep neural networks and recurrent architectures (e.g., LSTM and GRU) are predominantly employed for time-series prediction tasks such as energy demand and thermal dynamics forecasting. CNN-based models are commonly adopted for spatial feature extraction from sensor grids or temperature fields, while GNN has gained increasing attention for modeling relational dependencies among building components, zones, and energy networks. In addition, hybrid approaches that combine physical constraints with data-driven learning, such as physics-informed or rule-constrained models, are increasingly explored to enhance robustness and interpretability in DT applications.

At the workflow level, AI-enabled DT systems generally follow a closed-loop pipeline comprising real-time data acquisition via IoT sensors, data preprocessing and storage in cloud-based databases, AI model training and inference through API-accessible engines, and feedback of predictive results or optimized control actions to physical building systems. This closed-loop mechanism enables continuous synchronization between physical assets and their virtual counterparts, supporting adaptive learning and dynamic optimization throughout the building lifecycle.

Representative implementations further illustrate this paradigm. Ma et al. integrated an AI engine into the data analytics layer of a DT framework to support multiple smart building operation management tasks, including equipment failure prediction and environmental optimization, by accessing real-time and historical data via APIs [56]. Similarly, Xie et al. proposed an AI- and IoT-enabled fire prediction DT framework that forecasts future temperature fields based on historical data and integrates the results into the DT for real-time disaster prediction [68].

At the implementation level, this pipeline is commonly realized through cloud-based data analytics infrastructures. Static data, such as building geometry and material properties, is typically stored in relational databases (e.g., MySQL or PostgreSQL), while time-series operational and environmental data are managed using cloud-based platforms such as InfluxDB, Azure IoT Hub, or Google Cloud services. AI engines retrieve both historical and real-time data via APIs to train models and generate control commands, which are subsequently transmitted to physical systems through middleware such as MQTT. Cloud deployment of the data analytics layer not only reduces local computational and memory burdens but also facilitates model updating, scalability, and long-term maintenance of DT platforms.

4.2. LLM-Driven AI Agents for Collaborative Digital Twin Use

AI agents bridge the gap between human language and machine comprehension by enabling systems to interpret, reason over, and generate context-aware responses. Recent advances in LLM have significantly enhanced these capabilities, demonstrating human-like performance in language understanding, knowledge encoding, reasoning, and interaction, as exemplified by Generative Pre-trained Transformers (e.g., GPT-4 and GPT-4.5) [74]. In the AEC domain, LLM-driven AI agents are increasingly applied within DT environments to support virtual model construction, data interpretation, and natural language-based human–computer interaction, thereby facilitating more user-centered DT systems [75]. Although agent-based DT approaches show early potential to support lifecycle-wide interaction, their practical deployment remains at an exploratory stage.

Representative studies illustrate the emerging roles of AI agents in DT applications. Jiang et al. [76] integrated EnergyPlus with LLMs to translate natural language building descriptions into geometric configurations, usage scenarios, and equipment loads, enabling automated model generation. Li et al. [77] proposed an AI agent–based virtual instrument calibration method to align physical sensors with virtual building models, reducing manual calibration efforts. Luo et al. [78] developed ChatTwin to simplify interaction with DT platforms, significantly lowering task complexity and expertise requirements for operation and maintenance personnel. Collectively, these studies demonstrate how AI agents enhance DT accessibility and usability rather than replacing existing analytical models.

Beyond natural language interaction, LLM-driven AI agents introduce a distinct technical paradigm for DT systems by functioning as an intelligent orchestration layer. Architecturally, these agents are typically positioned above the data analytics and simulation layers, translating human intent into machine-executable workflows. Technically, LLMs act as the core reasoning engine and are augmented by external tools, including domain-specific databases, building information models (BIM), physics-based simulators (e.g., EnergyPlus), and conventional machine learning models. Through mechanisms such as prompt engineering, tool calling, and retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), AI agents can dynamically access DT data, invoke simulation or prediction modules, and synthesize results into actionable outputs. This enables a shift from model-centric DT interaction toward task-oriented and intent-driven operation.

From an implementation perspective, AI agent–based DT systems generally operate through an execution loop comprising intent parsing, resource retrieval, task decomposition, and result synthesis. When a user submits a query, the agent maps semantic intent to relevant DT services or data sources and executes the required operations via APIs. The resulting outputs—ranging from diagnostic explanations to recommended control actions—are presented to users in an interpretable and context-aware manner. Despite their potential, current LLM-driven DT implementations face limitations related to reasoning transparency, reliance on high-quality domain knowledge, and consistency with physics-based constraints. Consequently, most systems adopt a hybrid architecture in which AI agents support interaction, coordination, and decision assistance, while numerical prediction and control tasks remain grounded in established simulation engines and data-driven models.

5. Discussion

This study adopts a science mapping approach to provide a comprehensive review of AI-enabled DT in the AEC sector. By analyzing 316 journal articles published between 2015 and 2025, the review captures both the rapid expansion and the structural characteristics of this research field. The findings offer insights into how AI has been integrated into DT frameworks, the domains in which these integrations are most mature, and the limitations that currently constrain broader adoption and scalability.

The bibliometric results indicate a sharp growth trajectory in AI-enabled DT research, with publications accelerating markedly after 2020. This trend reflects increased institutional investment in smart buildings, digital construction, and data-driven operation and maintenance. While China leads in publication volume, the United States and several European countries demonstrate higher average citation impact, suggesting differing emphases between large-scale applied experimentation and theory-driven or framework-oriented research. These patterns indicate a maturing field that is expanding rapidly but remains uneven in terms of methodological depth and system integration.

The thematic analysis highlights five dominant application domains: safety management, energy management, historical building management, real-time construction monitoring, and predictive maintenance. Across these domains, DT frameworks are most effective when integrated with BIM and IoT infrastructures, while AI techniques are predominantly used for prediction, optimization, and pattern recognition. In particular, machine learning and deep learning approaches have demonstrated value in forecasting energy consumption, detecting anomalies, and supporting predictive maintenance during the operation and maintenance phase. However, most implementations remain task-specific and are rarely embedded within fully integrated, lifecycle-oriented DT systems.

A key contribution of this review lies in distinguishing between two emerging paradigms of AI integration in DT. The first focuses on AI-assisted data prediction and optimization within DT platforms, where AI models enhance decision-making by processing real-time and historical building data. While effective, these approaches often depend on extensive sensor networks, bespoke data pipelines, and domain-specific calibration, which limits their transferability across building types. The second paradigm involves LLM–driven AI agents designed to improve DT usability and accessibility. These systems aim to reduce the technical barriers associated with DT adoption by enabling natural language interaction, automated model configuration, and assisted operation and maintenance workflows. Although promising, AI agent–based DT remains at an early stage of development, with limited empirical validation and a lack of standardized integration frameworks.

From an industry perspective, this review indicates that the integration of AI and DT has progressed beyond a purely conceptual stage, although its readiness varies across application types. Several AI-enabled DT tools reported in the literature show strong potential for adoption by facility management organizations and real estate asset managers, particularly in the operation and maintenance phase. Typical examples include data-driven energy consumption forecasting, predictive maintenance for HVAC and electrical systems, and anomaly detection for equipment performance monitoring. These tools are generally modular, sensor-driven, and scalable across buildings with similar system configurations, making them suitable for portfolio-level deployment. In contrast, more advanced applications, such as automated DT construction, lifecycle-wide synchronization, and LLM-driven decision support, remain at an early or pilot stage. Despite their potential to reduce expertise barriers and enhance usability, their industrial adoption is constrained by data dependency, integration complexity, and governance issues. Overall, AI–DT development is progressing in a fragmented but tangible manner, with operational optimization representing near-term, industry-ready solutions, while lifecycle-integrated and agent-based DT systems constitute longer-term development directions. This distinction offers a pragmatic reference for stakeholders pursuing incremental adoption strategies.

6. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite notable progress, the scalability and industrial adoption of AI-enabled digital twin (DT) systems remain constrained by several structural limitations. From a technical perspective, the development and maintenance of IoT networks are resource-intensive, and data quality issues persist even in sensor-rich environments. In addition, real-time synchronization between physical buildings and their digital counterparts is still largely manual, especially when building layouts, equipment configurations, or operational strategies change. These issues significantly increase lifecycle maintenance effort and cost. At the organizational level, integrating AI algorithms with domain-specific building knowledge requires substantial interdisciplinary expertise. This increases in implementation complexity and limits the transferability of AI–DT solutions across projects. From a research standpoint, most existing studies rely on pilot projects or highly instrumented buildings, which raises concerns about the generalizability of reported results to more typical building stock.

Further limitations are evident in the context of AI agent–based DT systems. Current research mainly focuses on energy modeling and simulation assistance, while applications related to DT construction, lifecycle management, and collaborative workflows remain limited. Moreover, the roles of DT administrators, knowledge engineering processes, and governance mechanisms are rarely discussed. Human–computer interaction (HCI) considerations are also insufficiently addressed, resulting in DT interfaces that are technically powerful but poorly aligned with user needs and operational practices. Overall, these issues indicate that existing AI–DT implementations remain fragmented, with strong task-level performance but limited system–level integration and usability.

To overcome these limitations, future research should prioritize the development of integrated AI–DT frameworks that combine prediction, reasoning, and interaction within coherent system architectures. In particular, reference architectures for AI agent–based DT systems are needed to clarify the functional roles of AI agents and their interactions with BIM, IoT, and simulation modules. Such architectures should clearly distinguish data-driven learning components, domain knowledge representations, and decision logic to support more scalable and comparable system development.

Another important direction concerns benchmark datasets and standardized evaluation protocols. Open, multi-modal datasets that integrate BIM models, sensor data, and operational records are essential for validating AI–DT solutions across different building types and lifecycle stages. In parallel, standardized performance metrics, such as prediction accuracy, synchronization latency, robustness, and usability, would enable more consistent assessment of system effectiveness and transferability. Future research should also focus on automated model updating and continuous synchronization. AI-enabled methods that detect physical and operational changes and incrementally update DT models could significantly reduce manual intervention and lifecycle maintenance costs. This capability is particularly important for extending DT applications beyond operation and maintenance toward lifecycle-oriented use.

In addition, knowledge-enhanced and hybrid AI approaches deserve greater attention. Combining machine learning with building physics models, expert rules, and domain ontologies can improve the generalizability, interpretability, and trustworthiness of DT-based decision support, especially in safety-critical and regulated contexts. Finally, the socio-technical dimensions of AI-enabled DT adoption require more systematic investigation. Beyond technical performance, empirical studies are needed to examine stakeholder acceptance, skill gaps, and organizational change associated with DT integration in AEC practice. Greater attention to governance structures, training strategies, role redefinition, and HCI design is essential to ensure that AI-enabled DT systems are not only technically advanced but also usable, trustworthy, and institutionally viable.

7. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive review of AI-enabled DT research in the AEC sector, synthesizing 316 journal articles published between 2015 and 2025. By combining bibliometric science mapping with thematic analysis, the paper captures the evolution, dominant application areas, and emerging directions of AI-enabled DT development at the building scale.

The review demonstrates that DT has been most actively applied in five key domains: safety management, energy management, historical building management, real-time construction monitoring, and predictive maintenance. Across these areas, DT frameworks are commonly supported by BIM and IoT infrastructures, while AI techniques are primarily employed for prediction, optimization, and anomaly detection. These integrations enable more responsive building operations, improved risk management, and enhanced decision-making throughout the building lifecycle, particularly during operation and maintenance phases.

Beyond cataloging applications, this study identifies two distinct and increasingly influential paradigms of AI integration within DT systems. The first paradigm centers on AI-assisted prediction and optimization, where machine learning and deep learning models enhance the analytical capabilities of DT platforms by processing large volumes of real-time and historical building data. The second paradigm involves the emerging use of LLM–driven AI agents to improve DT usability, accessibility, and collaboration by enabling natural language interaction and automated support for model construction and operational tasks. While the former has reached a higher level of technical maturity, the latter remains in an early developmental stage with significant potential for transforming how DT is adopted and used in practice.

Despite substantial progress, the review highlights several persistent challenges that limit the scalability and broader adoption of AI-enabled DT in the built environment. These include the complexity and cost of IoT network deployment, difficulties in maintaining real-time synchronization between physical assets and digital models, limited integration between AI algorithms and domain-specific building knowledge, and restricted generalizability beyond highly instrumented pilot projects. In addition, the lack of standardized frameworks for AI agent integration, insufficient attention to governance and knowledge engineering processes, and underdeveloped human–computer interaction (HCI) design further constrain the effectiveness of DT platforms in real-world settings.

The findings of this review suggest that future research should move beyond isolated technical solutions toward integrated, lifecycle-oriented AI–DT frameworks. Priority areas include automated model updating, transferable AI solutions applicable across diverse building types, user-centered DT interface design, and systematic integration of AI agents with expert knowledge and operational workflows. Addressing these challenges is essential for advancing DT from experimental and project-specific implementations toward scalable, industry-ready systems that can support the long-term digital transformation of the AEC sector.

This study is subject to several limitations. The review is based on journal articles indexed in Web of Science and Scopus and restricted to English-language publications, which may exclude relevant studies in other languages or publication formats. Future reviews could expand the scope of data sources and incorporate additional analytical perspectives to provide a more comprehensive understanding of AI-enabled DT development. Nevertheless, the findings presented here offer a robust and up-to-date synthesis of current research and provide a structured foundation for future academic inquiry and practical implementation of AI-enabled DT in the built environment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/buildings16040809/s1. Table S1: PRISMA Checklist; Table S2: Publications’ list.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W. and M.A.S.; methodology, Y.W., K.W. and F.G.; software, Y.W., Y.Z. and F.G.; validation, Y.W.; formal analysis, Y.W.; investigation, Y.W.; data curation, Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.W. and M.A.S.; visualization, Y.W.; supervision, M.A.S.; project administration, M.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the authors used Generative Artificial Intelligence (GPT-4, OpenAI) to improve the readability and language of the manuscript. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed. The authors consent to this acknowledgment and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AEC | Architecture, engineering, and construction |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| AR | Augmented reality |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| BIM | Building information modeling |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DT | Digital Twin |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| HCI | Human–computer interaction |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning |

| HBIM | Heritage Building Information Modeling |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| VR | Virtual reality |

References

- Dixit, S.; Mandal, S.N.; Sawhney, A.; Singh, S. Relationship between Skill Development and Productivity in Construction Sector: A Literature Review. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2017, 8, 649–665. [Google Scholar]

- Leviäkangas, P.; Mok Paik, S.; Moon, S. Keeping up with the Pace of Digitization: The Case of the Australian Construction Industry. Technol. Soc. 2017, 50, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetik, M.; Peltokorpi, A.; Seppänen, O.; Holmström, J. Direct Digital Construction: Technology-Based Operations Management Practice for Continuous Improvement of Construction Industry Performance. Autom. Constr. 2019, 107, 102910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaei, R.S.; Burgess, G. Non-Technical Inhibitors: Exploring the Adoption of Digital Innovation in the UK Construction Industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 185, 122036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M.W. Product Lifecycle Management: The New Paradigm for Enterprises. IJPD 2005, 2, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Digital Twin Paradigm for Future NASA and U.S. Air Force Vehicles. Available online: https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/10.2514/6.2012-1818 (accessed on 17 January 2026).

- Grieves, M.; Vickers, J. Digital Twin: Mitigating Unpredictable, Undesirable Emergent Behavior in Complex Systems. In Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems: New Findings and Approaches; Kahlen, F.-J., Flumerfelt, S., Alves, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 85–113. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, R. About the Importance of Autonomy and Digital Twins for the Future of Manufacturing. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2015, 48, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schluse, M.; Rossmann, J. From Simulation to Experimentable Digital Twins: Simulation-Based Development and Operation of Complex Technical Systems. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Systems Engineering (ISSE), Edinburgh, UK, 3–5 October 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.; Snider, C.; Nassehi, A.; Yon, J.; Hicks, B. Characterising the Digital Twin: A Systematic Literature Review. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Tao, F.; Liu, A. New Paradigm of Data-Driven Smart Customisation through Digital Twin. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 58, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Lv, H.; Lv, Z. Big Data Analysis of the Internet of Things in the Digital Twins of Smart City Based on Deep Learning. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 128, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, M.M.; Shah, S.A.; Shukla, D.; Bentafat, E.; Bakiras, S. The Role of AI, Machine Learning, and Big Data in Digital Twinning: A Systematic Literature Review, Challenges, and Opportunities. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 32030–32052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafsanjani, H.; Nabizadeh, A. Towards Digital Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) Industry through Virtual Design and Construction (VDC) and Digital Twin. Energy Built Environ. 2023, 4, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, M.A. Framing Mixed Realities. In Mixed Reality In Architecture, Design And Construction; Wang, X., Schnabel, M.A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y. Intelligent Building Construction Management Based on BIM Digital Twin. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2021, 2021, 4979249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Yang, J.; Wang, F. Application and Enabling Digital Twin Technologies in the Operation and Maintenance Stage of the AEC Industry: A Literature Review. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 107859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to Conduct a Bibliometric Analysis: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.; Yuan, H.; Chen, Q. Science Mapping Approach to Assisting the Review of Construction and Demolition Waste Management Research Published between 2009 and 2018. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 140, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souley Agbodjan, Y.; Wang, J.; Cui, Y.; Liu, Z.; Luo, Z. Bibliometric Analysis of Zero Energy Building Research, Challenges and Solutions. Sol. Energy 2022, 244, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyükkıdık, S. A Bibliometric Analysis: A Tutorial for the Bibliometrix Package in R Using IRT Literature. JMEEP 2022, 13, 164–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.; Zayed, T. Crane Operations and Planning in Modular Integrated Construction: Mixed Review of Literature. Autom. Constr. 2021, 122, 103466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomfors, M.; Lundgren, K.; Zandi, K. Incorporation of Pre-Existing Longitudinal Cracks in Finite Element Analyses of Corroded Reinforced Concrete Beams Failing in Anchorage. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2021, 17, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, Y.; Lee, S.J.; Chowdhury, A.G. Imaging-to-Simulation Framework for Improving Disaster Preparedness of Construction Projects and Neighboring Communities. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2017, 2017, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamari, M.; Ham, Y. AI-Based Risk Assessment for Construction Site Disaster Preparedness through Deep Learning-Based Digital Twinning. Autom. Constr. 2022, 134, 104091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Hou, L.; Zhang, G.; Chen, H. Real-Time Mixed Reality-Based Visual Warning for Construction Workforce Safety. Autom. Constr. 2022, 139, 104252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosamo, H.H.; Nielsen, H.K.; Kraniotis, D.; Svennevig, P.R.; Svidt, K. Digital Twin Framework for Automated Fault Source Detection and Prediction for Comfort Performance Evaluation of Existing Non-Residential Norwegian Buildings. Energy Build. 2023, 281, 112732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, N.; Spencer, B. Post-Earthquake Building Evaluation Using UAVs: A BIM-Based Digital Twin Framework. Sensors 2022, 22, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Sun, C.; Li, Y.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, G. Applications of Digital Twin Technology in Construction Safety Risk Management: A Literature Review. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibrandi, U. Risk-Informed Digital Twin of Buildings and Infrastructures for Sustainable and Resilient Urban Communities. ASCE-ASME J. Risk Uncertain. Eng. Syst. Part A Civ. Eng. 2022, 8, 04022032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Hucks, R.G. Preserving Our Heritage: A Photogrammetry-Based Digital Twin Framework for Monitoring Deteriorations of Historic Structures. Autom. Constr. 2023, 152, 104928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angjeliu, G.; Coronelli, D.; Cardani, G. Development of the Simulation Model for Digital Twin Applications in Historical Masonry Buildings: The Integration between Numerical and Experimental Reality. Comput. Struct. 2020, 238, 106282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Liu, Y.; Karlsson, M.; Gong, S. Enabling Preventive Conservation of Historic Buildings Through Cloud-Based Digital Twins: A Case Study in the City Theatre, Norrköping. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 90924–90939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Feng, H.; Chen, Q.; Garcia de Soto, B. Developing a Conceptual Framework for the Application of Digital Twin Technologies to Revamp Building Operation and Maintenance Processes. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 49, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyano, J.; Carreño, E.; Nieto-Julián, J.E.; Gil-Arizón, I.; Bruno, S. Systematic Approach to Generate Historical Building Information Modelling (HBIM) in Architectural Restoration Project. Autom. Constr. 2022, 143, 104551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, A. A Comprehensive Heritage BIM Methodology for Digital Modelling and Conservation of Built Heritage: Application to Ghiqa Historical Market, Saudi Arabia. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Naeem, G.; Khalid, M. Digitalization for Sustainable Buildings: Technologies, Applications, Potential, and Challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 450, 141814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, S.; Wichern, G.; Laughman, C.; Chong, A.; Chakrabarty, A. Calibrating Building Simulation Models Using Multi-Source Datasets and Meta-Learned Bayesian Optimization. Energy Build. 2022, 270, 112278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsiwala, A.; Elghaish, F.; Zoher, M. Digital Twin with Machine Learning for Predictive Monitoring of CO2 Equivalent from Existing Buildings. Energy Build. 2023, 284, 112851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Wang, F.; Li, H.; Pang, B.; Yang, J. Carbon Emissions Accounting and Estimation of Carbon Reduction Potential in the Operation Phase of Residential Areas Based on Digital Twin. Appl. Energy 2024, 376, 123155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lydon, G.P.; Caranovic, S.; Hischier, I.; Schlueter, A. Coupled Simulation of Thermally Active Building Systems to Support a Digital Twin. Energy Build. 2019, 202, 109298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, R.; Torres-Aguilar, C.E.; Xamán, J.; Zavala-Guillén, I.; Bassam, A.; Ricalde, L.J.; Carvente, O. Digital Twin Models for Optimization and Global Projection of Building-Integrated Solar Chimney. Build. Environ. 2022, 213, 108807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdaus, M.M.; Dam, T.; Anavatti, S.; Das, S. Digital Technologies for a Net-Zero Energy Future: A Comprehensive Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 202, 114681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, H.; Xu, P.; Yan, C.; Ji, Y.; Zhou, K.; Chen, F. Development of a Key-Variable-Based Parallel HVAC Energy Predictive Model. Build. Simul. 2022, 15, 1193–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqar, A. Intelligent Decision Support Systems in Construction Engineering: An Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Approaches. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249, 123503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejeb, A.; Keogh, J.G.; Leong, G.K.; Treiblmaier, H. Potentials and Challenges of Augmented Reality Smart Glasses in Logistics and Supply Chain Management: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 3747–3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaloul, W.S.; Qureshi, A.H.; Musarat, M.A.; Saad, S. Evolution of Close-Range Detection and Data Acquisition Technologies towards Automation in Construction Progress Monitoring. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 43, 102877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Ma, L.; Broyd, T.; Chen, K. Digital Twin and Its Implementations in the Civil Engineering Sector. Autom. Constr. 2021, 130, 103838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, L. A BIM-Data Mining Integrated Digital Twin Framework for Advanced Project Management. Autom. Constr. 2021, 124, 103564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasim, M.; Han, T.M.; Huang, H.; Madiyev, M.; Ngo, T.D. An Approach for Sustainable, Cost-Effective and Optimised Material Design for the Prefabricated Non-Structural Components of Residential Buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, M.; Li, M.; Liu, X.; Zhong, R.Y.; Pan, W.; Huang, G.Q. Digital Twin-Enabled Real-Time Synchronization for Planning, Scheduling, and Execution in Precast on-Site Assembly. Autom. Constr. 2022, 141, 104397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Ma, Y.; Chen, L.; Pedrycz, W.; Skibniewski, M.J.; Chen, Z.-S. Artificial Intelligence for Production, Operations and Logistics Management in Modular Construction Industry: A Systematic Literature Review. Inf. Fusion 2024, 109, 102423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cao, C.; Liu, Z. A Framework for Prefabricated Component Hoisting Management Systems Based on Digital Twin Technology. Buildings 2022, 12, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chong, A.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, C.; Lam, K.P. Whole Building Energy Model for HVAC Optimal Control: A Practical Framework Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Energy Build. 2019, 199, 472–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Xiao, F.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Xu, K.; Luo, X. Digital Twin for 3D Interactive Building Operations: Integrating BIM, IoT-Enabled Building Automation Systems, AI, and Mixed Reality. Autom. Constr. 2025, 176, 106277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Xie, X.; Parlikad, A.K.; Schooling, J.M. Digital Twin-Enabled Anomaly Detection for Built Asset Monitoring in Operation and Maintenance. Autom. Constr. 2020, 118, 103277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teisserenc, B.; Sepasgozar, S.M.E. Software Architecture and Non-Fungible Tokens for Digital Twin Decentralized Applications in the Built Environment. Buildings 2022, 12, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Pishdad-Bozorgi, P. BIM-Enabled Facilities Operation and Maintenance: A Review. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2019, 39, 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Es-sakali, N.; Zoubir, Z.; Idrissi Kaitouni, S.; Mghazli, M.O.; Cherkaoui, M.; Pfafferott, J. Advanced Predictive Maintenance and Fault Diagnosis Strategy for Enhanced HVAC Efficiency in Buildings. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 254, 123910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chan, A.P.C.; Darko, A.; Chen, Z.; Li, D. Integrated Applications of Building Information Modeling and Artificial Intelligence Techniques in the AEC/FM Industry. Autom. Constr. 2022, 139, 104289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Cao, J.; Zhu, S. Data-Driven Monitoring and Predictive Maintenance for Engineering Structures: Technologies, Implementation Challenges, and Future Directions. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 14527–14551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Ding, Y.; Song, Y.; Geng, F.; Wang, Z. Digital Twin-Driven Framework for Fatigue Life Prediction of Steel Bridges Using a Probabilistic Multiscale Model: Application to Segmental Orthotropic Steel Deck Specimen. Eng. Struct. 2021, 241, 112461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem Khan, M.; Obaidat, M.S.; Mahmood, K.; Batool, D.; Muhammad Sanaullah Badar, H.; Aamir, M.; Gao, W. Real-Time Road Damage Detection and Infrastructure Evaluation Leveraging Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Tiny Machine Learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 21347–21358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewunruen, S.; Lian, Q. Digital Twin Aided Sustainability-Based Lifecycle Management for Railway Turnout Systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 1537–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, G.; Wu, L. Room Thermal Load Prediction Based on Analytic Hierarchy Process and Back-Propagation Neural Networks. Build. Simul. 2022, 15, 1989–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, D.; Shi, L. Thermal-Comfort Optimization Design Method for Semi-Outdoor Stadium Using Machine Learning. Build. Environ. 2022, 215, 108890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wong, H.Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Z.; Wu, X.; Shi, J.; Huang, X.; Xiao, F.; et al. AIoT-Powered Building Digital Twin for Smart Firefighting and Super Real-Time Fire Forecast. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, S.; Hu, Z.; Zayed, T. Micro-Electromechanical Systems-Based Technologies for Leak Detection and Localization in Water Supply Networks: A Bibliometric and Systematic Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Parlikad, A.; Woodall, P.; Ranasinghe, G.; Xie, X.; Liang, Z.; Konstantinou, E.; Heaton, J.; Schooling, J. Developing a Digital Twin at Building and City Levels: Case Study of West Cambridge Campus. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 05020004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Lee, S.H.; Masoud, N.; Krishnan, M.S.; Li, V.C. Integrated Digital Twin and Blockchain Framework to Support Accountable Information Sharing in Construction Projects. Autom. Constr. 2021, 127, 103688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Shafiq, M.; Douglas, D.; Kassem, M. Digital Twins in Built Environments: An Investigation of the Characteristics, Applications, and Challenges. Buildings 2022, 12, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Lee, S. Digital Twin for Supply Chain Coordination in Modular Construction. Appl. Sci. Basel 2021, 11, 5909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J. Prompt Engineering to Inform Large Language Model in Automated Building Energy Modeling. Energy 2025, 316, 134548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T. A Knowledge-Guided and Data-Driven Method for Building HVAC Systems Fault Diagnosis. Build. Environ. 2021, 198, 107850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J. EPlus-LLM: A Large Language Model-Based Computing Platform for Automated Building Energy Modeling. Appl. Energy 2024, 367, 123431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Koo, J.; Lee, J.; Wang, P.; Zhao, T.; Yoon, S. AI Agent-Driven Virtual in-Situ Calibration for Intelligent Building Digital Twins. Energy 2025, 339, 138968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Wen, X.; Jiang, Y.; Pärn, E.; Brilakis, I. ChatTwin: Bridging the Usability Gap to Digital Twin Adoption in Infrastructure Operations and Maintenance with a Natural Language Interface. Autom. Constr. 2026, 181, 106655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.