Abstract

The Construction Industry-related degree programs in higher education institutions are substantially significant platforms for mandating the excellence of Construction Management Education (CME). The quality enhancement in the built environment is achieved through CME, where contemporary education and research yield advanced construction methods for Industry. The education delivery in Building Construction Science/Technology/Management disciplines is planned through the designated policies of the State and regulatory authorities in the United States of America, in addition to the individual vision and mission of the institutions. With the advent of Artificial Intelligence, the rubrics and teaching methodologies have shifted to an advanced mechanism in higher education. In this research, concentrating on the same aspect of transformations in Construction Education allied with the use of modern tools, various undergraduate programs like Building Construction Science or Construction Management, use of modern education has been focused on; thereby concentrating on ‘Studio’ education as the key objective of this research. The continuing education goal in CME is to deliver life-long learning skills to students, so that they achieve sustainable development as qualified professionals later on. Henceforth, Studio teaching is discussed in this research for its impact on students’ expertise, knowledge development and life-long learning. Studio education is a unique dimension in technical disciplines such as Architecture and Construction Science, and, therefore, to achieve the essential objectives of ‘Studio Instructional Technology’, the students are introduced to real-world challenges, so that they can visualize and ultimately innovate solutions for the industry. This paper determines the effectiveness of teaching practices that instructors are expected to utilize while formulating the concepts and skills in students during Design or Structural Studios at the undergraduate level. Utilizing a structured and methodologically robust analytical research, the study formulates evidence-based recommendations for optimizing Studio-instruction pedagogies within undergraduate degree programs of CME.

1. Introduction

Higher education at the undergraduate level constitutes an applicable mechanism for shaping professional competence in learners of Construction Management and the broader built environment disciplines. It is the Studio curricula that hold the potential of familiarizing the learners with practical skills and tools at the undergraduate level, whereas the education pattern is more analytic and research-oriented theoretical format in the postgraduate level of CME pertaining to Master’s and PhD programs. The building sector significantly influences social well-being, economic development and environmental sustainability of any society. As a considerable responsibility lies upon academic institutions to produce industry-ready graduates capable of responding to complex real-world challenges [1,2], the quality of education related to Construction Management and the built environment requires a structured and outcome-oriented approach that integrates curriculum design with effective teaching and learning practices to successfully strenghten performance of graduates of CME towards industry relevance [3].

In undergraduate Construction education, productivity and professional competency are largely achieved through well-aligned curricula that articulate clear learning outcomes at both course and program levels. Studies emphasize that coherent curriculum frameworks, supported by measurable student learning objectives, are fundamental to achieving desired educational outcomes in Construction and Architectural education [4,5]. Undergraduate programs in construction-related disciplines in the United States are commonly offered under varying nomenclatures, including Building Construction Science, Building Construction Management and Building Construction Technology. These distinctions are not merely semantic but reflect differences in curricular emphasis, professional orientation and accreditation pathways [6].

The variation in degree nomenclature and curricular structure is closely associated with the involvement of distinct regulatory bodies. For instance, programs emphasizing Construction Science and Management are often accredited by the American Council for Construction Education (ACCE), whereas technology-oriented programs typically fall under the accreditation framework of American Buraeu of Engineering & Technology (ABET). Accreditation requirements play a pivotal role in shaping program objectives, curriculum content and assessment mechanisms, thereby influencing graduate competencies and professional trajectories [7,8].

The undergraduate CME represents a period during which foundational knowledge, technical skills and professional values are developed in an in-depth way, and this phenomenon directly impacts future construction industry standards [9]. Within this context, the integration of design-build and Studio-based pedagogies has emerged as a central component of Construction education. Construction Design Studio courses are commonly embedded across any degree program to bridge theoretical instruction with applied learning. Studio-based education in Construction Management and Architectural disciplines is recognized for its distinctive pedagogical structure combining lectures, collaborative problem-solving, individualized critiques, fieldwork, simulations and industry-oriented activities [10,11]. To summarize, these techniques result in innovation produced by the students while designing various spaces, buildings, cities and structural systems during their assignments.

Studio teaching demands a balance in substantial engagement from students, instructors and industry stakeholders. The broad spectrum of Studio courses is also reflected in higher credit allocations and intensive instructional formats in the Studio course briefs. Students’ performance in Studio courses is widely regarded as an indicator of their ability to synthesize theoretical knowledge and practical skills acquired across parallel coursework in the streams of Theoretical and Workshop/Lab based subjects [8,11]. Moreover, exposure to real-world constraints, construction methods and project-based learning environments during Studio education effectively enhances professional readiness and critical thinking capabilities in learners [12]. This establishes that performance of students in Studio courses directly reflects the learners’ understanding level of the theoretical and workshop/lab courses that they study side-by-side in aterm.

In recent years, the transformation of Studio education from traditional to modern tools-based methods has been further accelerated by the integration of advanced digital tools and emerging technologies, including Building Information Modeling (BIM), simulation platforms and Artificial Intelligence (AI). These innovations have contributed to more interactive, data-driven and adaptive learning environments, and this ultimately enables students to produce architectural and construction solutions as enhanced visualization, decision-making and performance assessment in Construction education [13,14,15]. Simultaneously, sustainability-oriented curricula and technology-enabled pedagogies have become essential in addressing contemporary demands and regulatory expectations of the Construction Industry [16].

Against this backdrop, this study addresses the following research objectives:

- To examine whether the precision of educational outcomes in Construction-related undergraduate programs in the United States is influenced by curriculum design, Studio-based pedagogical approaches and compliance with accreditation and state regulatory frameworks.

- To investigate how the integration of advanced teaching methods and Artificial Intelligence, has transformed traditional ‘Construction Studio Teaching’ into more dynamic and responsive learning environments.

2. Literature Review

Studio-based pedagogy has been widely recognized as a core instructional model in construction and built environment education, particularly in preparing graduates to address complex, interdisciplinary challenges associated with contemporary building practice in the real-world. A narrative review of fifteen research articles in this research reveals that, although Studio teaching is not standardized across institutions, its effectiveness lies in aligning pedagogical strategies with clearly defined learning outcomes relevant to the evolving demands of the Building sector. These strategies include collaboration, teamwork, digital integration, analytical skill development and cross-disciplinary resource management. The entire mechanism is developed to help students achieve innovation and sustainability in their solutions for the built environment [17].

The Studio environment functions as both a physical and cognitive space for individual and social learning. Prior studies emphasize the importance of balancing informal peer interaction with opportunities for private experimentation and reflection, enabling students to translate dialogue and critique into meaningful design and construction decisions [18,19]. Such learning environments foster iterative problem-solving and reflective practice, which are essential competencies in building design and construction processes.

Studio pedagogy is best understood as an integrated educational system rather than a collection of isolated teaching components. Quality in Studio instruction emerges through the interconnection of experiential engagement, Instructor’s feedback and reflective critique. It is important that instructors maintain Studio education to remain adaptable while preserving their core pedagogical principles [18]. This flexibility has enabled Studio teaching to remain relevant across individual contexts of Universities within the built environment disciplines.

2.1. Quality Management in Studio Education

In Studio education in CME, knowledge is acquired tacitly through participation and observation rather than formal instruction, and this reinforces the need for structured quality management frameworks in Studio teaching [20]. Construction education programs increasingly align Studio curricula with industry expectations and accreditation standards in the country, particularly those established by ACCE and ABET, to ensure consistency in learning outcomes related to socio-economic, cultural and environmental backgrounds [4,7].

A cross-sectional review of undergraduate curricula and accreditation policies highlights that Studio instruction serves as a primary mechanism for translating regulatory requirements into measurable educational outcomes. This alignment is particularly relevant to the Buildings special issue focus on innovation in education and construction practices, as it ensures that pedagogical approaches respond directly to industry and societal needs.

2.1.1. Pedagogical Techniques in Studio Instruction

Studio instruction in Building Construction Science and Architectural education integrates theory with practice through mentorship-driven techniques, blended with project-based learning models rooted in case-studies and apprenticeship traditions [11,13]. These pedagogical techniques support experiential learning, teamwork and reflective practice, enabling students to develop both cognitive and technical competencies essential to building design and delivery. The literature review further highlights the role of Artificial Intelligence and digital assistance tools in enhancing Studio instruction [21]. AI-supported tools can improve feedback quality, design exploration and predictive analysis without compromising academic originality, aligning with broader digital transformation trends in the building sector [22].

2.1.2. Integrated Learning Environments

Integrated Studio learning environments enable students to incrementally understand the complex systems and processes inherent in building projects. Through peer learning, real-world engagement and structured reflection, students develop transferable problem-solving skills and a systems-oriented understanding of construction and design workflows [12,23]. The conceptualization and evolution of solutions in Studio assignments is attained by the students, through the intricate integration of multi-directional pedagogical techniques in CME where various stages of Construction management are deliberated, as requirements of projects submissions [24].

2.1.3. Digital Tools

Digital tools have become central to Studio instruction by enhancing visualization, coordination and communication in Building Construction Science education. Prior studies demonstrate that tools such as BIM platforms and parametric design software improve students’ ability to analyze patterns, trends and relationships across building systems [25,26]. Their integration into Studio pedagogy is increasingly regarded as essential for preparing graduates to engage with technologically advanced construction practices.

2.1.4. Experiential Learning

Experiential learning remains a defining characteristic of Studio education in the built environment. Grounded in Kolb’s learning theory that corresponds to the four stages of (i) Concrete Experience (CE), (ii) Reflective Observation (RO), (iii) Abstract Conceptualization (AC) and (iv) Active Experimentation (AE), it becomes further supported that fieldwork and real-world project engagement should be emphasized to enhance students’ spatial awareness, contextual understanding and technical proficiency [27]. These approaches align academic instruction with industry practice and this strategy eventually achieves continuous improvement in CME education.

2.2. Mixed Studio Teaching Methodology

The mixed methods teaching in Studio courses, comprising Studio discussions, dialogues, crit and review, site and environmental analyses, has been further hypothesized in this research as a way to keep Studio learning connected to the outdoor experiential learning of students [17,18,19]. An analysis of a conservation site study, performed in the UK to find out how students can improve their decision-making for solving Studio assignments in a more productive way, in which a field experience was arranged for students by their Department, showed that students developed a better understanding of the materials of construction used in the conservation of a heritage site [20].

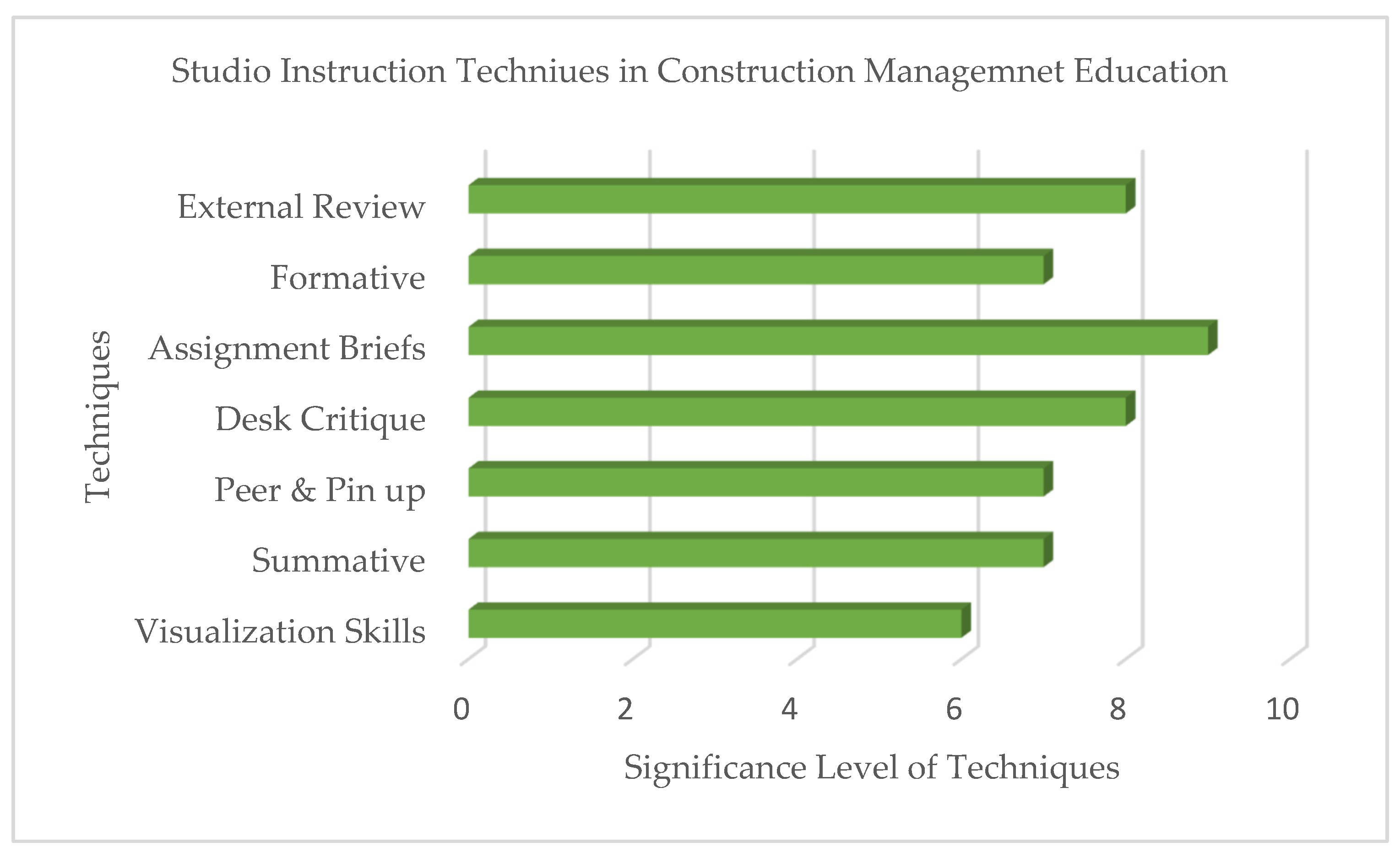

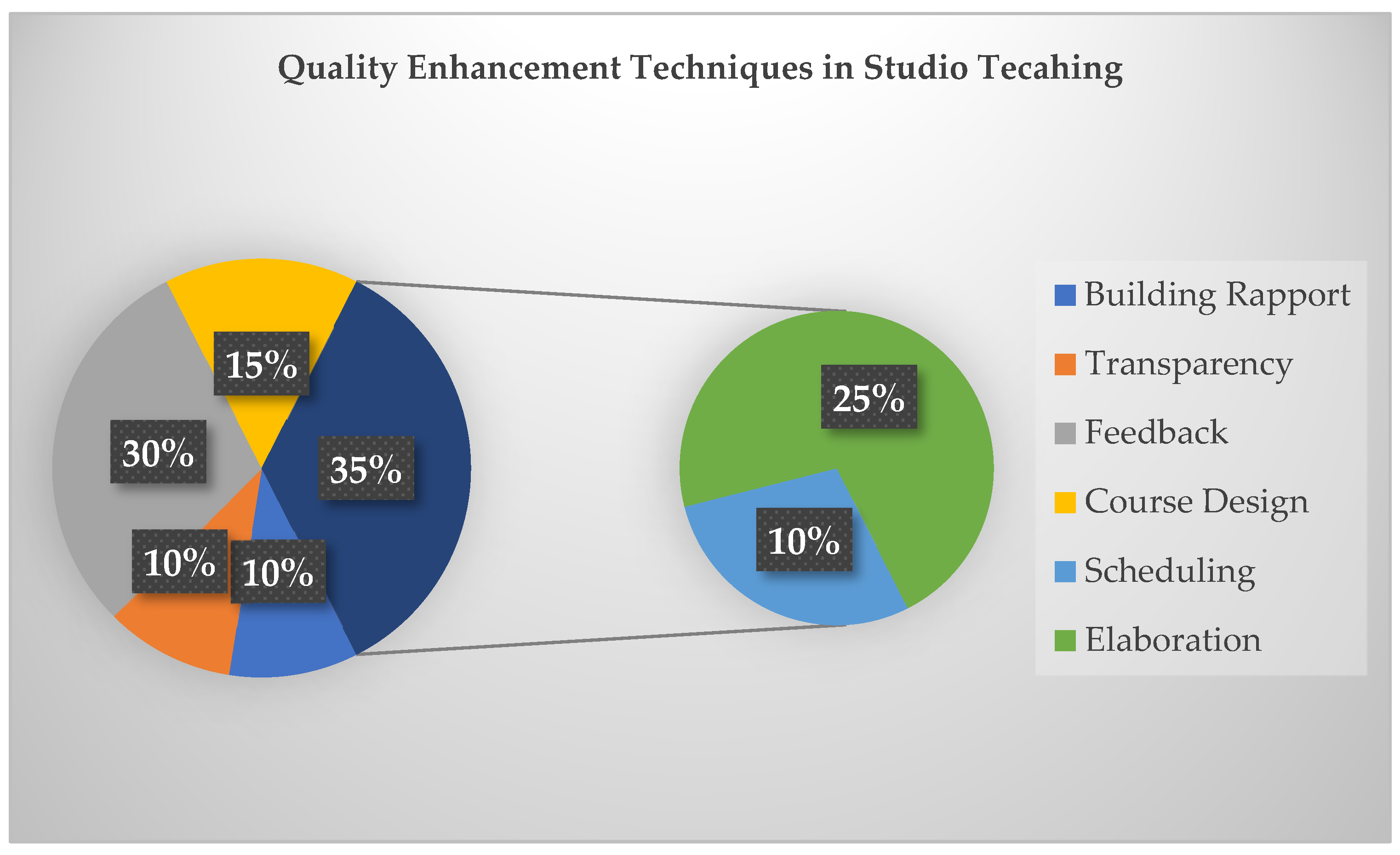

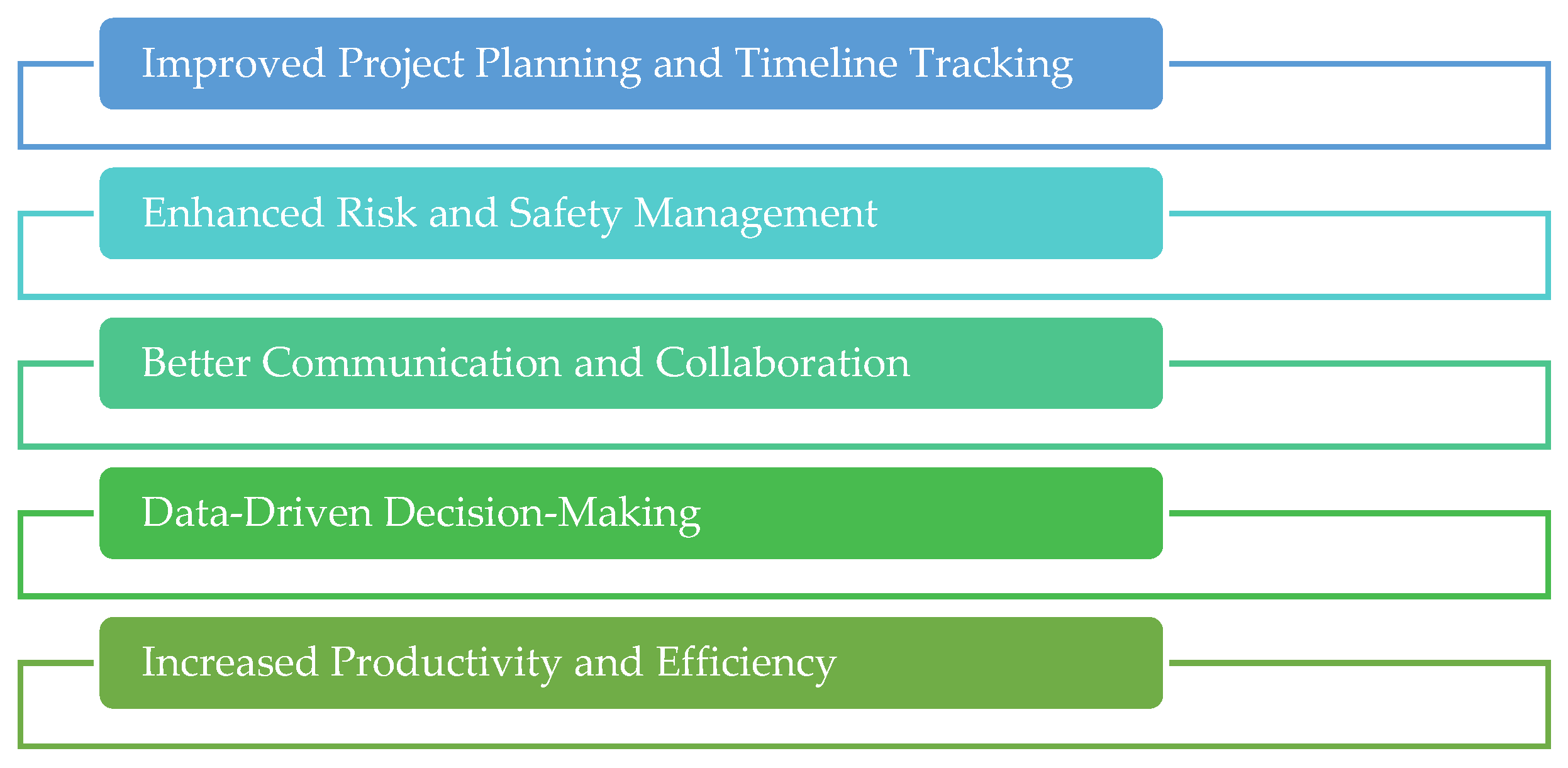

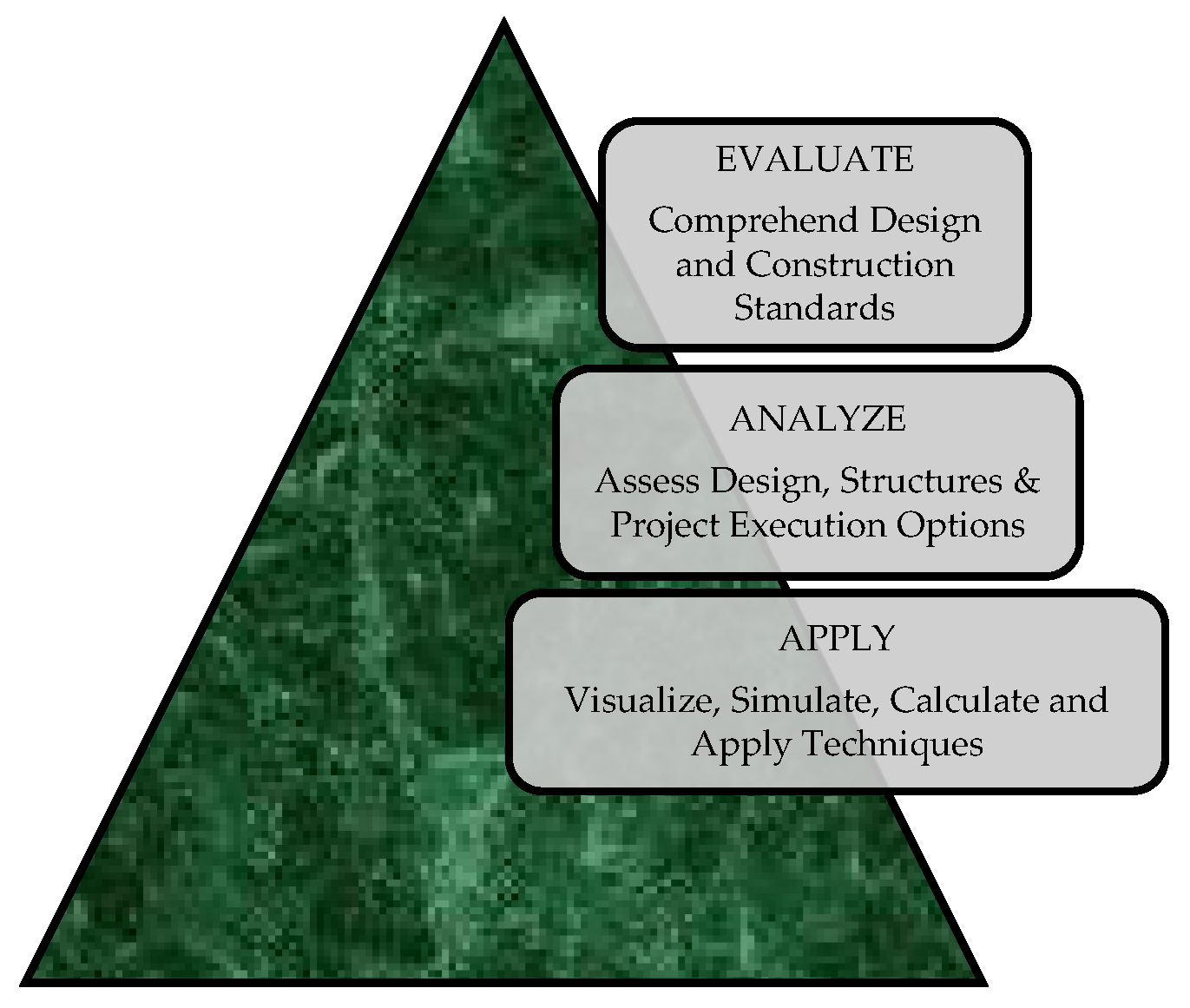

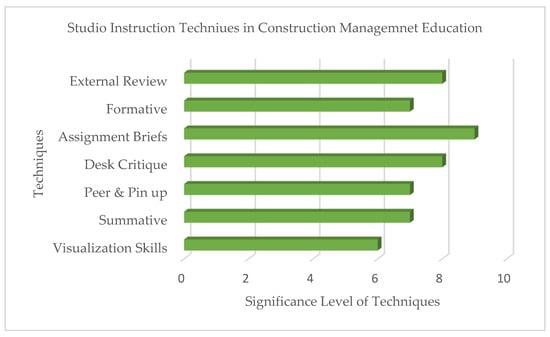

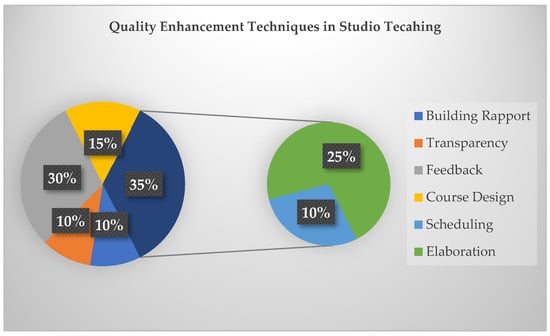

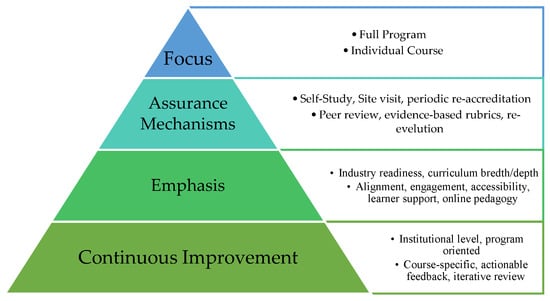

Through a case-based pedagogical exploration of Studio teaching practices within a selected CME program, instructional techniques are summarized, in accordance with the literature review of this research, in Figure 1 below, including iterative critique, collaboration and skill demonstration during Studio learning. The same techniques have been validated in the Results section of this manuscript, as the key strategies to enhance learning and thus formulate the hypothesis of this research paper. Quality enhancement through Hypothesis, shown in Figure 2 here, enables theoretical and contextual triangulation, strengthening the credibility of findings while remaining consistent with the exploratory intent of the study.

Figure 1.

Studio instruction techniques. Source: author.

Figure 2.

Quality Enhancement Techniques. Source: Author.

Despite its strengths, Studio pedagogy faces challenges in balancing creative exploration with technical rigor. The literature suggests that expanding Studio teaching across allied construction disciplines and adopting mixed instructional methods such as critiques, dialogue and field-based learning can enhance interdisciplinary understanding and learning continuity [28]. These strategies support the development of practice-ready graduates capable of addressing contemporary challenges in the Architecture and Construction Industry in the USA. However, at times, there remains a challenge in balancing the allocation of resources and time in terms of the documentation/analytic section and project presentation part, which learners have to compile.

Based on an analytic review of secondary data resources [28], a pie chart is presented in Figure 2, hypothesising the pertinence of disseminating the Course Brief to the learners, building rapport with students and tangible schedules for a transparent road map of a Studio course as the dominant techniques for quality enhancement in Studio instruction. In this context, an elaboration of each course objective and its practical outcome in Construction Industry is very effective in strengthening students’ comprehension and long-term learning of construction techniques. ‘Elaboration’ in the context of Studio teaching in CME refers to a set of multi-dimensional resources relevant to CME, as discussed in the case-study program in the later section of this research [28].

3. Research Methodology

Through a systematic literature review and integrated analysis, this paper explores how curriculum development, instructional communication and administrative leadership collectively contribute to improved educational outcomes in Construction education. In this research, quality enhancement in Construction education has been measured through the significance of Studio teaching in selected undergraduate CME degrees.

To evolve dynamic Studio instructional techniques, the research began with a comprehensive review of curricula from Construction Management and Building Construction Science programs across U.S. universities, identifying the institutions where Studio pedagogy intersects with Construction education. Additionally, accreditation guidelines from bodies such as the American Council for Construction Education (ACCE) and the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology (ABET) were analyzed to extract relevant directives that could inform Studio teaching strategies.

As the corresponding author draws on professional experience as an instructor in an Architectural Design Studio [29], the methodology incorporated insights gained through faculty development workshops conducted by the Center for Instructional Teaching and Excellence (CITE) at Mississippi State University. This was followed by by a thorough review of Quality Matter (QM) guidelines for effective instructional design. This multi-faceted approach provided a robust framework for evolving effective Studio teaching techniques within Construction Management Education [30]. The findings from curriculum analysis, accreditation review and instructional design principles were synthesized to develop a conceptual framework for improving Studio teaching in Construction Management Education. This framework emphasizes active learning, iterative design processes and interdisciplinary collaboration as core components for elevating student performance and professional readiness to meet the rising requirements of sustainable built environment as a common international goal.

3.1. Data Collection

Data for this study was derived exclusively from secondary and institutional qualitative sources belonging to time period between 2021 and 2025, and are narrated as follows:

- Peer-reviewed journal articles addressing Studio pedagogy, objective-based learning, experiential education and digital transformation in Architecture and Construction education.

- Authentic publicly available curriculum documents and Studio syllabi from undergraduate Architecture, Construction Management and Construction Science programs in United States and other countries.

- Accreditation criteria and policy documents issued by recognized accrediting bodies governing Construction and Architectural education.

- Instructional planning materials and qualitative insights obtained from faculty discussions and pedagogical workshops related to techniques for Studio teaching enhancement.

These sources were selected to ensure alignment with contemporary educational practice while maintaining transparency and reproducibility in the research process.

3.2. Sampling Strategy

A purposeful sampling strategy was employed to identify undergraduate programs where Studio education plays a central role in achieving program-level learning outcomes. Ten Construction-related departments across USA were initially reviewed based on curriculum accessibility, clarity of student learning objectives and their alignment with accreditation standards for better built environments, utilizing authentic open access resources.

From this group, a representative program of CME was selected for in-depth exploration and subsequent analysis. The selection was guided by its explicit articulation of studio objectives, structured assessment mechanisms and integration of modern teaching tools [24]. Additionally, an architecture program has also been briefly included in this research for its successful impacts on quality of architectural practice through effective Studio pedagogy.

3.3. Analytical Procedure

The qualitative analysis followed an interpretive thematic approach, aiming on how Studio teaching practices support objective-based learning. Data sources were scientifically translated for their relevance to objectives of this research following interpretations of quality measures of higher education [31] and analyzed across four recurring pedagogical dimensions identified in the literature and institutional documents, as narrated below:

- Alignment of Studio activities with student learning objectives.

- Use of experiential and project-based learning strategies.

- Integration of digital and interactive instructional tools.

- Structuring of feedback, critique and reflective learning processes.

Patterns emerging across these dimensions were synthesized to identify modern Studio teaching practices relevant to Architecture and Construction degree programs.

3.4. Ethical Considerations and Study Scope

All data sources were publicly available at the instructional and research levels. The study is positioned as exploratory, with findings intended to inform pedagogical development rather than prescribe standardized instructional models in Studio Pedagogy.

3.5. Potential References for Studio Teaching by ACCE and ABET

Both these regulatory authorities play a significant role in quality enhancement of the Construction education programs offered by universities in USA. In this regard, a comparative study was conducted in this research about the American Council of Construction Education (ACCE) and the American Board for Engineering and Technology (ABET). The inclusion of ACCE and ABET criteria further highlights the relevance of Studio Instructional Methods in CME and facilitates an assessment of convergent student-learning objectives within an outcome-based and continuously improving instructional framework. The guidelines from both regulatory bodies, operationalized as instructional objectives for CME Studio courses, are detailed in Table 1 [4,7].

Table 1.

ACCE and ABET guidelines for quality enhancement in CME across universities in the USA.

4. Results

The results of this study demonstrate that active learning through real-world projects and collaborative problem-solving constitutes a central instructional objective in Studio-based teaching within Architecture and Construction-related degree programs. Analysis of curricula, Studio briefs and focus-group discussions indicates that practical skill development is enthusiastically supported through field visits, practical exercises and industry–academia collaborative forums. This set of practices is particularly important in Studio projects addressing contemporary construction practices and technologies [32,33,34].

Upper-level Studio and Skills Training courses, such as Virtual Design Construction and Automation in Construction, were found highly beneficial in advancing students’ proficiency in digital construction tools, including Building Information Modeling (BIM), 3D Printing, Robotics and Construction Automation Systems. Course documentation and syllabus requirements show that these tools are not supplementary but embedded as assessed components of Studio learning outcomes. This method is very effective in enabling students to develop applied digital competencies relevant to current industry demands [3].

Adherence to institutional academic policies was identified as an important quality dimension; however, results indicate that Studio teaching often necessitates policy-level flexibility. Departments offering Studio-intensive curricula were observed to pursue formal adjustments through established academic governance mechanisms to accommodate extended contact hours, iterative assessment cycles and alternative evaluation formats when Studio-specific policies were not already in place [35].

4.1. Resultant Studio Teaching Model

The findings confirm that objective-based Studio teaching practices significantly contribute to quality enhancement in Architecture and Construction education. Based on documented evidence from Studio agendas, assessment rubrics and selected faculty workshop records, this research establishes a Studio teaching model comprising:

- Active learning tasks linked to defined learning outcomes. This corresponds to short assignments like ‘Documentation of Social Spaces’ as an example, within the Departments or Campuses, that students may conduct in a week and present to the studios.

- Formative and summative practical assessments: Innovative assignments like the effects of a certain material of construction on the overall carbon emissions of the buildings in a city or a neighborhood. Such assignments may be taken as an amalgam of Mathematical/ Statistical/ Scientific and software-based applications.

- Rapport building through sustained instructor–student interaction.

- Transparency in assessment criteria.

- One-on-one and peer-based reviews for individual and group work.

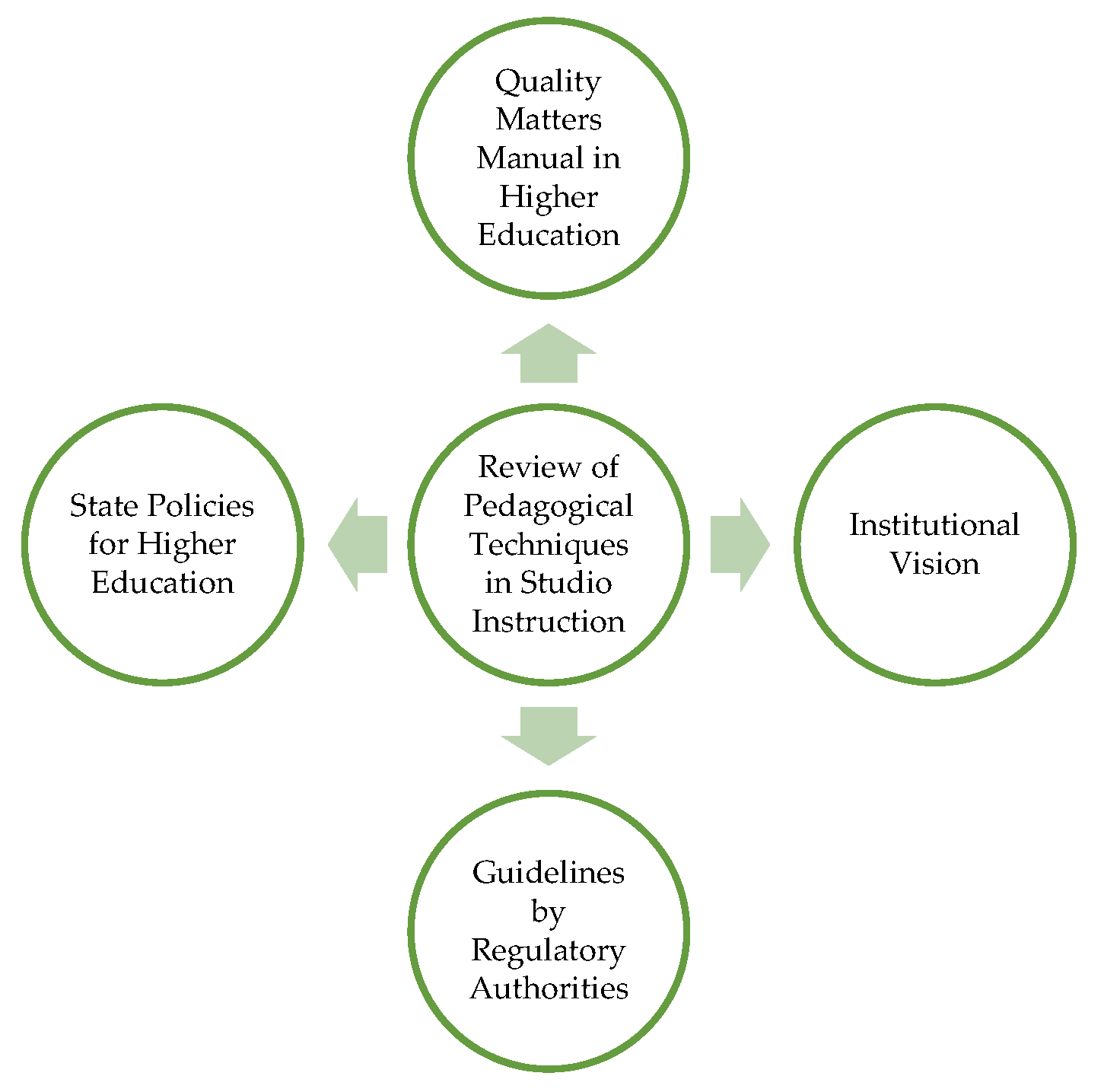

Instructional techniques as identified in this research include iterative design cycles, structured peer reviews, industry feedback loops and the systematic use of BIM-based workflows to reinforce both technical and conceptual learning in context [3,32]. Consistent with experiential learning theory, Studio-based experimental learning enables students to generate more effective problem-solving strategies and design responses, thereby improving readiness for professional practice [36]. In order to strategize the improvement in CME curricula focused on Studio courses, a cyclic curriculum development process is synthesized by the authors and presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Review of pedagogical techniques in Studio instruction.

4.2. Quality Enhancement Techniques in Studio Instruction

The results further indicate that ‘Studio Instruction’ provides a platform for developing leadership skills, continuous learning habits and professional liability among undergraduate students. Evidence from ‘Studio Briefs’ and ‘Mentoring Schedules’, studied by the author, shows that regular instructor guidance supports sustained engagement and progress of learners. Importantly, Studios that explicitly integrate ‘Climate Change’ and ‘Resilience’ as considerations into ‘Design Briefs’ and ‘Evaluation Criteria’ of semester or a year’s Course Outline, enable students to contextualize construction solutions within broader environmental and societal challenges [11]. These findings reinforce the role of higher education in addressing climate-responsive design and construction practices.

Implementation of ACCE and ABET Guidelines

The integration of ACCE and ABET accreditation guidelines for evolving quality management-oriented instructional strategies was found highly dynamic for both technical rigor and educational consistency across Construction Management, Construction Science and Construction Technology programs in the USA. Curriculum documents and accreditation self-study materials show that Studio environments promote student-centered learning through structured activities, skill mastery and continuous feedback mechanisms. These elements are essential for CME where applied competence is important [4,7].

The incorporation of BIM-based workflows, design-build experiences and industry collaboration into Studio instruction ensures curricular relevance while supporting accreditation compliance and quality assurance [24]. Analysis of the selected case study program demonstrates that when Studio instruction adopts a technology-intensive pedagogy, the following ABET-aligned outcomes are achieved:

- Application of skills and technology in CME.

- Integration of Mathematics, Science, Visualization and Engineering in problem-solving.

- Execution and interpretation of standard tests and measurements.

- Effective teamwork within technical groups.

- Identification and resolution of defined Construction Management problems.

- Application of Communication Skills across technical contexts.

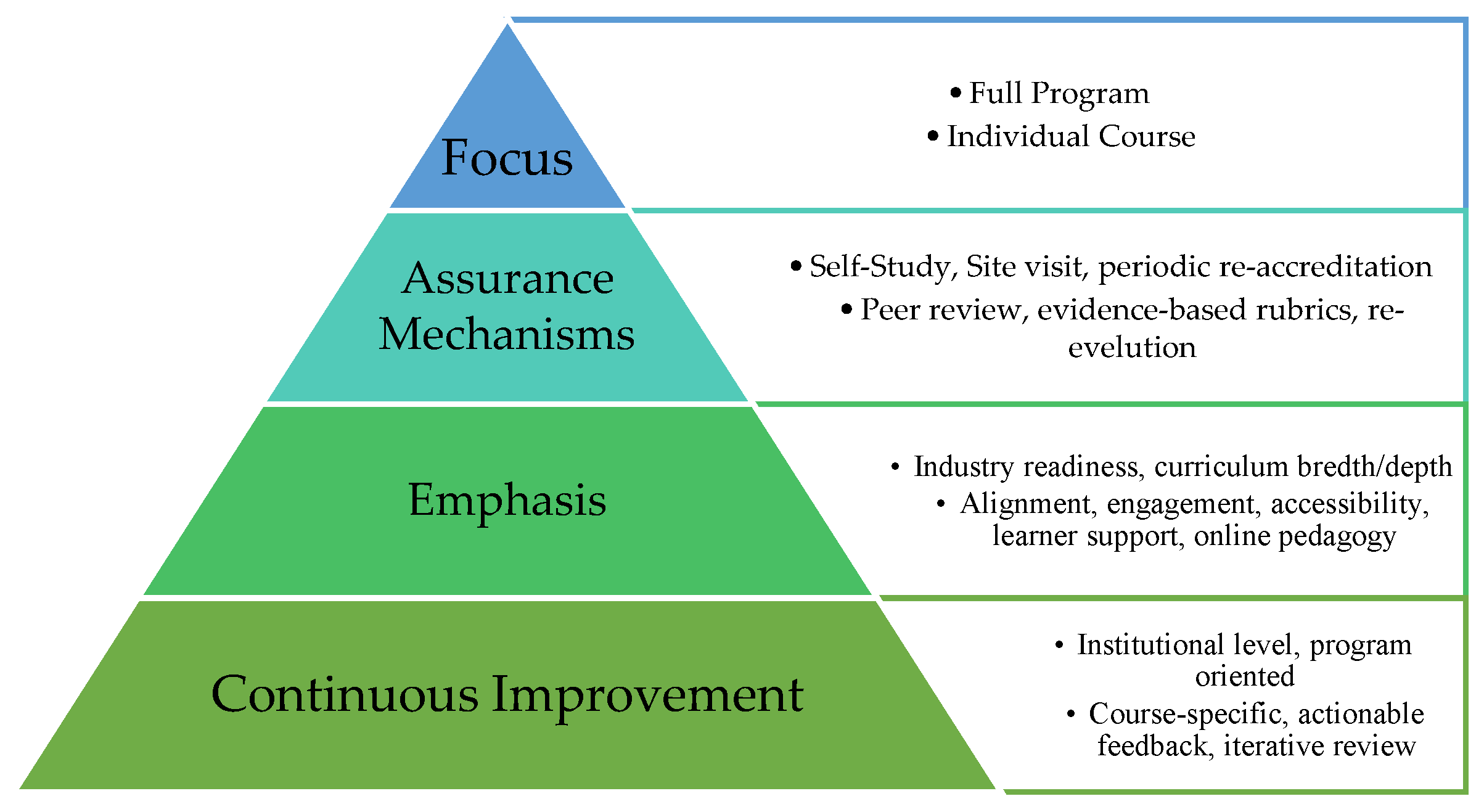

These outcomes are explicitly included in ‘Studio Assessment Rubrics and Workshop Documentation’, confirming their role as program educational objectives rather than aspirational goals in the selected case study Degree Program, in this research. The synthesis of these findings is presented in Figure 4, illustrating a strategic model for achieving continuous improvement and quality assurance in Studio education.

Figure 4.

Strategic model for Studio teaching practices in Construction and Architectural education. Source: author.

4.3. Derivations from Interviews, Focus Groups and Secondary Data Analysis

Findings from faculty interviews, focus-group discussions and secondary institutional data highlight that the accrediting and professional bodies lay down clear guidance on including Resilience, Sustainability and Technology in Construction and Architectural education. Analysis of selected institutions shows that Studios increasingly prioritize active learning, industry partnerships and AI-supported tools to accelerate cognitive processing and strengthen design thinking; and the same has been validated through literature review [3,32].

Guidelines issued by leading professional and academic associations provide structured educational frameworks and quality benchmarks that directly inform curriculum development as well as Studio pedagogy [13]. These frameworks emphasize the need for curriculum adaptation in response to global challenges, including climate change and rapid technological advancement. Table 2 below synthesizes the convergence of ACCE, ABET and QM guidelines, which support the pedagogical importance of Studio-focused coursework within Construction Science and Management education.

Table 2.

Quality enhancement frameworks for Construction-related Higher Education.

4.4. Contextual Analysis of Studio Learning Environments

Primary and secondary data collectively justify Studio teaching as a responsive learning system, where instructional inputs generate observable learning outcomes in the form of students’ step-by-step outputs during the Studio projects. Studio learning is structured around the ‘Design Brief’, which serves as the foundational instructional document guiding students to comprehend the design and structural details, conceptualize solutions in reference to the various theory courses that they study side by side, and then visualize/present their drawings through manual graphics as well as digital tools. Results confirm that deeper learning occurs through extended Studio contact hours compared to conventional lecture-based courses, and this phenomenally supports immersion in disciplinary culture and practice in Architecture and Construction Management Education [18].

Consistent with contemporary scholarship, findings indicate that a Studio need not be confined to a physical space to foster immersion. Rather, immersion is achieved through sustained engagement with disciplinary norms, behaviors and workflows. All this leads to professional enculturation and acculturation in CME and Architectural education, subsequently impacting positively to better standards in the built environment [18]. Data visualization tools used in CME were found to enhance actionable understanding through dashboards, charts, 3D models and spatial mapping. These tools support project monitoring, budgeting, resource allocation, safety management and environmental analysis.

4.5. Integration of Advanced Visualization Tools in Studio Education

Contemporary Architectural Design Studios and Building Construction Science programs increasingly rely on advanced visualization technologies to enhance student engagement with real-world construction scenarios. The latest tools include Autodesk Revit 2025, widely used for Building Information Modeling (BIM); SketchUp Pro 2024, offering intuitive 3D modeling capabilities; Enscape 4.0 (2024) for real-time rendering and immersive visualization; and Twinmotion 2024.2, which integrates photorealistic rendering with VR compatibility. Additionally, Unity Reflect Review 2025 and Unreal Engine 5.3 (2024) are being adopted for Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) applications, enabling interactive design reviews and spatial simulations. These tools support iterative design processes, interdisciplinary collaboration and experiential learning, bridging the gap between conceptual design and practical construction workflows. Their integration into Studio education equips students with industry-relevant skills and prepares them for complex project environments in the built environment [37].

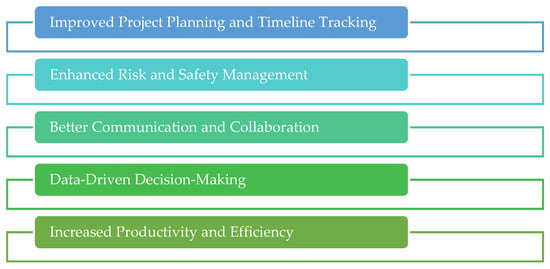

4.6. Key Benefits of Visualization Tools and Graphical Feedback

The results indicate that the logical use of visualization tools in Studio learning and instruction yields multiple operational benefits. Project planning and timeline tracking are improved through Gantt charts and milestone dashboards, enabling early identification of delays and informed resource reallocation [13,16]. Risk and safety management is accessed by visual representations of site conditions and incident patterns, and, thus, supports Risk-Assessment in decisions during Construction projects.

Visualization tools and Machine Learning, also facilitate clear communication and collaboration among students, instructors and industry participants by simplifying complex construction data. Furthermore, data-driven decision-making is strengthened through real-time analytics. The visualization of trends thus further develops timely responses to budgetary, logistical and market-related issues. Finally, students tend to have increased productivity and efficiency when they place greater focus on core Design and Construction tasks in the Studio assignments, with predictive and futuristic Design tools.

Visual clarity was identified as a critical instructional factor in Studio teaching, encompassing the use of presentation software, animations, virtual and augmented reality and simulation-based feedback. These dimensions of quality enhancement are summarized in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Dimensions of Quality Enhancement in Construction and Built Environment Education.

Digitization in Instructors’ Feedback

The analysis confirms the effectiveness of digitization in Instructors’ feedback in Studio coursework, with project submissions pertaining to the following:

- (a)

- Gantt charts for tracking schedules, dependencies and resource allocation.

- (b)

- Heatmaps for identifying safety risk zones and incident clusters.

- (c)

- Dashboards for integrating timeline, budget, risk and progress metrics.

- (d)

- The 3D and 4D models for visualizing construction sequencing and spatial progress

5. Discussion

In Studio teaching for Architecture and CME, the teaching methodology, referring to Objective-Based Education (OBE) techniques, emphasizes measurable learning goals aligned with practical skills and critical thinking. Effective teaching practices in these Studios integrate learner-centered methods that simulate real-world professional design and construction challenges [12,14,22]. Moreover, quality enhancement in construction management and built environment education programs, especially in Construction Studio environments affects teaching techniques that are in line with quality frameworks such as ACCE, ABET and Quality Matters [4,7].

5.1. Teaching Techniques for Studio Instruction Aligned with Objective-Based Education

Students apply their skills in Studio exercises that require research, analysis and solution-driven responses. This aligns with the OBE standards by achieving specific problem-solving skills in project completion in Studio courses [2,3]. Regular feedback by Instructors helps the students gain mastery in skills, whereas group projects help build teamwork and communication skills, and this practice achieves an absolutely important outcome in CME [3,30].

5.2. Integrated Lectures and Visual Demonstrations

Motivated lectures and skill demonstrations in Studio sessions can impart technical knowledge in students corresponding to individual context of a project. This practice significantly matches with OBE’s focus on outcome-driven instruction [8,9] and is reflective through incorporation of BIM, CAD and project management software in CME [7,11].

5.3. Interactive Discussions in Studio Hours

An understandable course brief for building design or construction project with defined objectives and deliverables achieves immediate attention and interest of the learners [21,30]. This interest is further improved by conducting weekly design charrettes or pin-ups; where instructors and peers review students’ work for performance as per goals [14,18]. The mini-lectures and rigorous discussions on a one-on-one basis further enhance students’ understanding and skills in project phases like structural detailing or selection of materials for construction [11,23]. Studio-based learning in construction needs an exclusive supplement of peer-to-peer discussions as well as a collaborative methodology of interactions amongst various semesters/terms within department/college and even institutions [24]. Guidance to students through collaborative team exercises with role assignments mimicking real-world project teams is an effective teaching strategy in Studio courses [25,38].

5.4. Reflective Writing for Continuous Formative Evaluation

As a Studio teaching practice, it acquires the use of digital modeling, project management software labs and the reflective writing practices [17,20]. The midterm and final reviews with internal and external reviewers to assess project outcomes signify the output in a very constructive way [26]. The students’ site visits, fieldwork and construction simulations to connect theory with practice altogether bring quality in the Studio performance of the students [14,16,20]. Precedent studies, historical evolution, comprehension of codes/standards and case analyses to inform design decisions aligned with learning objectives are integral means of Studio Instruction [7,26]. At this stage, the use of predictive Artificial Intelligence methods remains equally important to forecast and analyze students’ performance; however, this practice remains subjective to the institutional policies and parameters.

5.5. ACCE and ABET Guidelines

Accreditation standards for construction programs typically encompass rigorous criteria to ensure educational quality, relevance and continuous improvement to prepare graduates effectively for professional practice. Both ACCE and ABET emphasize quality control, continuous improvement and alignment of curriculum with industry needs and professional competencies [4,7,18]. Construction program accreditation standards require clear program objectives, comprehensive curricula, qualified faculty, assessment of student learning outcomes, institutional support and continuous program improvement processes [15,19]. These standards ensure that graduates are prepared to meet professional and industry expectations in Construction Management and related fields.

Referencing the Accreditation Guide Manual by ACCE, the following strategic practices are found to be supportive of Studio teaching in CME [27,30]:

- A multi-perspective set of teaching resources including videos, slide presentations, case studies, field surveys and interactions with industry should be provided to the learners in CME. In the context of the objectives of this research, this set of teaching resources should be delivered to learners before reaching the summative assignment stage, which is by default the Studio/ Final Term project when offered [4,30].

- The evaluation instrument in the case of Studio courses must correspond to a set pattern and be communicated to the students through a Course Brief document and it should clearly indicate potential improvements for students at any prescribed stage [26].

The ABET Criteria for accrediting Engineering Technology Programs are based upon the knowledge, skills and behavior that students acquire in a program through the curriculum [4,7]. A study of Construction Management Studios conducted at Knoxville Studio in cohorts, where the main objective was to validate the ABET criteria through teaching the modules in studio settings that the faculty had already developed for semesters. The attendees worked in teams of 3–4 to address the criteria of collaboration and teamwork. Presentations and industry tours were also managed during this workshop. The students were made to present their work at the end of this workshop for evaluation by the trainers. The evaluation criteria corresponded to the following dimensions:

- (1)

- Continuous improvement.

- (2)

- Student learning objectives.

5.6. Quality Matters (QM)

The Quality Matters framework is a global, research-supported standard for ensuring the quality of online and blended courses in Higher Education at Mississippi (MS) [4], USA. One of its important features is a peer-based and developmental review process guided by structured rubrics focused on continuous improvement. Through a focused review of features of Quality Management, the following techniques are interpreted for improving the CME teaching practices within Studios:

- (a)

- Course Design Rubrics: Quality Management rubrics are divided into ‘General Standards’ and ‘Specific Review Standards’ which determine the alignment of the learning objectives with assessments, instructional materials, learner support, technology and accessibility [4].

- (b)

- Evidence-Based Marking Criteria: Rubrics come straight from an extensive literature review, as well as what educators have found to be most effective recommendations that accommodate both research and what works best within a learning environment [3,4].

- (c)

- Objective Peer Review: Courses are evaluated by peer reviewers to make sure that they are up to standards, and reaching at least 85% compliance will then be QM certified [39].

- (d)

- Continuous Improvement: Feedback is also used to improve course design, student engagement and project cycles. The QM framework helps in keeping the pace of pedagogical techniques productive in studio courses [39].

The QM quality enhancement guidelines validate that the teaching practices in general are based on instructional design, learning objectives, assessment, instructional materials, learners’ interaction, technology use, support and accessibility [30,31]. Explaining this guideline to Studio teaching, the Educational Science corresponds directly to the requirements of Studio teaching, as was explained in the Introduction and Literature Review sections of this research. QM-certified courses have an emphasis on continuous learning and education through not only instructor feedback but also peer feedback, and these practices overlap with techniques required for effective Studio pedagogies [4]. For a Studio course, the QM techniques may be utilized for both the full semester length as well as in individual lessons during a week. Therefore, adopting these QM techniques will result in students’ readiness for the construction industry [4,11].

5.7. A Review of Studio Teaching in Different Institutions

By the increased usage of AI content in higher education, one can see a new trend, with colleges such as University College London’s Bartlett School of Architecture and Carnegie Mellon University as some of those who have already embraced AI-oriented coursework into their required content [7,28]. Various durations of degree programs have serious repercussions on the teaching methodologies and practices in Design studios of Architectural education [32].

The foundational pedagogical techniques for Studio Education; as discussed in the above stated programs, remain consistent in their structure and implementation as learning-by-doing and reviews by internal/external examiners to evolve a crit [13,30]. The key characteristics of studio teaching have been found to be the following, after reviewing the above-mentioned institutions:

- Advanced Design Simulation and Generative AI: Project management and collaboration platforms that have been AI-powered allow better organization with studio group tasks, help to assign each member a responsibility and track each member’s contributions to a project [12,22].

- Collaborative Workflow Automation: AI-powered project management and collaboration platforms help organize studio group tasks, assign responsibilities and track individual contributions aligned with learning deliverables and professional competencies [3,20].

- Data-Driven Decision-Making in Pedagogical Practice: Data given by AI systems may be able to give better help to continuous teaching insights and effective methods, along with student achievement based on course standards, resulting in better teaching practices [7].

- Contemporary Teaching Philosophy by Studio Instructors: The student-centric approaches and outcome-based studio environments where every activity is mapped to specific competencies measurable through objective criteria are encouraged for successful Studio learning [14,34].

5.8. Case Study: ACCE-Accredited Studio-Based Construction Education

Building Construction Science Program, Mississippi State University:

The Bachelor of Science in Building Construction Science (BCS) at Mississippi State University represents a mature and well-established model of Studio-based CME that aligns strongly with Outcome-Based Education (OBE) principles and ACCE accreditation requirements. The program is fully accredited by the American Council for Construction Education (ACCE) and is widely recognized for embedding Studio pedagogy as a central instructional framework rather than a supplementary teaching method [13].

5.8.1. Program Structure and Educational Objectives

The BCS program is designed to prepare graduates for professional roles in Construction Management and related fields by integrating technical knowledge, managerial competencies and applied problem-solving skills. The curriculum is structured around progressive learning outcomes that advance from foundational construction principles to complex as well as interdisciplinary project execution. It has also been analyzed through an in-depth review of the curriculum that there is a consistent alignment between course objectives, instructional activities and measurable student outcomes in Studio courses [13].

A distinguishing feature of the program is its vertical Studio sequence that facilitates student enrollment in Construction Studios across multiple academic years. Continuous feedback by the instructors, peer discussions, scheduled weekly breakdowns and elaboration on the contexts of Construction Projects are adopted as key practices in Studio instruction. This structure reflects the OBE emphasis on mastery of competencies through staged assessment and refinement rather than isolated course completion [3,13].

5.8.2. Studio-Based Pedagogical Model

Unlike traditional lecture-centric construction programs, the BCS curriculum is anchored in formal Studio courses that simulate professional construction environments. Within these studios, students engage in team-based comprehension exercises, project-driven learning, addressing real-world construction scenarios involving estimating, scheduling, materials selection, construction methods and coordination among stakeholders [3,10]. Studio instruction is characterized by the following:

- (a)

- Defined project objectives and deliverables aligned with ACCE student learning outcomes;

- (b)

- Iterative design and construction problem-solving cycles;

- (c)

- Continuous formative feedback from faculty acting as facilitators and mentors;

- (d)

- Structured peer critiques and review sessions resembling professional project meetings.

This pedagogical approach closely mirrors best practices identified in the studio-based learning literature, where knowledge acquisition is reinforced through application, reflection and collaborative engagement [21].

5.8.3. Integration of Technology and Industry Practices

Technology integration is a core component of studio instruction within the BCS program. Students are required to use BIM-based workflows, construction visualization tools, digital estimating platforms and scheduling software as part of studio deliverables. These tools are not taught in isolation but are embedded within project tasks, ensuring that technology fluency directly supports learning outcomes related to coordination, cost control and constructability analysis [7,17]. The studio environment also supports role-based team assignments, reflecting industry practice by assigning students responsibilities such as project manager, estimator, scheduler, or field coordinator. This structure reinforces professional communication, accountability and interdisciplinary coordination—competencies emphasized by both ACCE and ABET frameworks.

5.8.4. Assessment, Accreditation and Continuous Improvement

Assessment within the BCS studio courses follows transparent and rubric-based evaluation instruments, which are consistent with ACCE accreditation standards and OBE assessment principles. Students’ performance is evaluated through a combination of project submissions, oral presentations, peer evaluations and reflective documentation [20,26]. The program demonstrates a strong commitment to continuous improvement, using assessment data, studio outcomes and external advisory input to refine curriculum content and teaching strategies. This approach aligns with accreditation expectations for systematic evaluation and program enhancement, thereby ensuring ongoing relevance to industry needs [19,20].

5.8.5. Alignment with Quality Frameworks and Research Objectives

From a quality enhancement perspective, the BCS program exhibits strong alignment with Quality Matters (QM) principles when Studio instruction is translated into Instructional Design terms. Clear learning objectives, alignment between objectives and assessments, structured learner interaction and meaningful use of instructional technology are consistently evident within Studio courses [4]. The Mississippi State University case illustrates how formal Studio courses within an ACCE-accredited construction program can effectively operationalize OBE principles, enhance student engagement and strengthen industry readiness. The program provides a replicable model for construction education institutions seeking to move beyond traditional lecture-based formats toward integrated, outcome-driven Studio pedagogy that supports professional competence and lifelong learning [25,27,39]. The Building Construction Science (BCS) program at Mississippi State University exemplifies a studio-centered and vertically integrated curriculum, where formal Studio courses correspond to mastery in skills, theoretical/technical specializations and use of technology. This structure represents a key strength of the program, as it enables early, continuous and progressively complex competency development. The BCS program’s integration of BIM-enabled workflows, role-based team structures and iterative assessment within studios closely mirrors professional construction practice, enhancing graduates’ readiness for industry demands [40].

U.S. construction projects consistently confront workforce shortages, schedule delays, cost volatility and regulatory complexity. The challenges can be mitigated when graduates master targeted competencies embedded in Mississippi State University’s Building Construction Science (BCS) curriculum, specifically Estimating, Scheduling, Health and Safety, Construction/Project Management, Financial Management, Construction Law, Building Technology, Construction Systems, Structures, Materials and Methods of Construction and continuous BIM application across all four years and Studio courses (e.g., BCS 1116–4126) [13].

5.8.6. BS Sustainable Architecture + Engineering

The Studio model, as a core of architectural pedagogy, is retained as a method for engaging students in the deeper complexities of real-world construction practice. The Sustainable Architecture + Engineering (SA + E) program at Stanford University demonstrates this trend by embedding a rigorous sequence of Studios into an interdisciplinary Engineering–Architecture curriculum. This analysis examines the mechanisms through which Studio instruction in the SA + E program enhances students’ understanding of construction practice, emphasizing iterative inquiry, spatial–technical integration, sustainability and real-world problem-solving [41]. The findings underscore importance of Studio pedagogy as an educational bridge between conceptual design and the material realities of building in a resource-constrained yet climate-sensitive world [41,42]

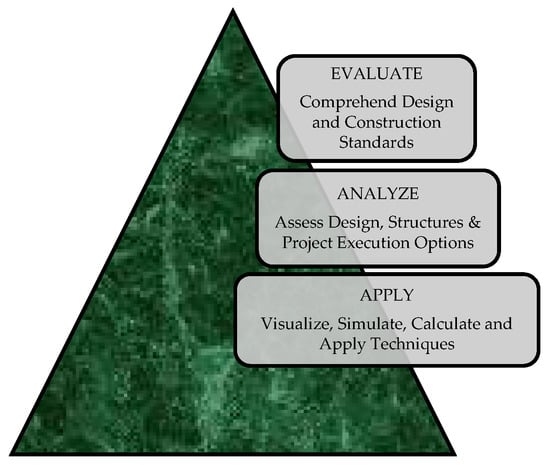

From a cognitive perspective, studio-based learning environments naturally operate at the upper levels of the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy, emphasizing analyzing, evaluating and creating. The integration of AI further strengthens this alignment by enabling students to engage with complex datasets, predictive simulations, generative design options and real-time performance feedback. The sequential pyramid in Figure 6 translates the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy into Studio Instruction and Learning stages; when transitioning a from formative to a summative level, the students are to execute the application of tools on more higher-level work, including critical evaluation, synthesis, and creative problem-solving, for their assignments related to Construction and Built Environment courses.

Figure 6.

Interpretation of Bloom’s Taxonomy in Studio Instruction.

6. Conclusions

The findings drawn from the literature synthesis, accreditation analysis and review of various institutions clearly address the two research objectives introduced at the outset of this research. It is with the Studio courses that the teaching achieves a connection within industry and academia, as the design practices are learnt through a multi-directional resource (comprising faculty and practitioner-led guidance) in Studios. The comprehensive Studio pedagogical practices render the learning environment of Studios an actual reflection of the real-world requirements and solutions of the Construction Industry.

This study confirms that Studio-based pedagogy is inherently compatible with OBE guidelines, as it enables measurable learning outcomes through iterative project cycles, staged deliverables and continuous formative feedback. Research in applied higher education consistently shows that Studio- and project-based learning environments yield higher gains in skill acquisition and problem-solving performance compared with traditional lecture-centric models. These outcomes are particularly evident in Construction and Architectural education, where professional competencies such as teamwork, communication skills, predictive analysis and decision-making under socio-econmic and environmental constraints are best learnt by the students through experiential learning. It has been clearly validated in the research that Studio-based instruction, particularly when implemented through structured modern tools and multi-year Studio course sequences provides a robust and scalable model for quality enhancement. ACCE and ABET accreditation requirements enforce systematic assessment of student learning outcomes and alignment with industry needs, while the QM framework [43] reinforces instructional coherence through objective assessment alignment, structured feedback and interactive methods. The research analysis demonstrates that quality assurance frameworks significantly support trends in Studio teaching by embedding transparency, technology, curriculum alignment towards the industry and continuous improvement in course delivery.

This study concludes by situating Studio-based Architectural and Construction education as an eminent quality enhancement element in Higher Education for Construction-related disciplines, and as phenomenal in the eventual ‘better built environment’ produced by qualified graduates of CME.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.A., R.U.F. and S.M.A.; methodology, Y.A. and S.M.A.; software, Y.A.; validation, R.U.F. and S.M.A.; formal analysis, Y.A. and S.M.A.; investigation, Y.A.; resources, Y.A.; data curation, Y.A.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.A.; writing—review and editing, R.U.F. and S.M.A.; visualization, Y.A.; supervision, S.M.A.; project administration, R.U.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge the support of the Department of Building Construction Science, College of Architecture, Art and Design at Mississippi State University for providing us a conducive research environment, and elevating our ambition to conduct research on quality enhancement in higher education for Construction Industry-related disciplines. We are thankful to all the respondents, including faculty and students in various universities, for providing us with feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations Environment Programme. Buildings and Climate Change: Summary for Decision-Makers; UNEP: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. Shaping the Future of Construction: A Breakthrough in Mindset and Technology; WEF: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, J.; Tang, C. Teaching for Quality Learning at University, 4th ed.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology (ABET). Criteria for Accrediting Engineering Programs, 2024–2025. Available online: https://www.abet.org/accreditation/accreditation-criteria/ (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Felder, R.M.; Brent, R. Designing and teaching courses to satisfy the ABET engineering criteria. J. Eng. Educ. 2003, 92, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, K.H.; Ayer, S.K.; Lamanna, A.J.; Eicher, M.; London, J.S.; Wu, W. Construction Education Needs Derived from Industry Evaluations of Students and Academic Research Publications. Int. J. Constr. Educ. Res. 2021, 19, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Council for Construction Education (ACCE). Standards and Criteria for Accreditation; ACCE: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.acce-hq.org/accreditation (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Anteet, Q.; Binabid, J. Investigating the discourse on pedagogical effectiveness in the architectural design studio. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2025, 21, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prados, J.W.; Peterson, G.D.; Lattuca, L.R. Quality assurance of engineering education through accreditation. J. Eng. Educ. 2005, 94, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Salama, A.M. (Ed.) Spatial Design Education New Directions for Pedagogy in Architecture and Beyond; Routledge Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- College of Architecture, Art and Design, Mississippi State University. Building Construction Science. Available online: https://www.caad.msstate.edu/academics/majors/building-construction-science (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Nicol, D.; Pilling, S. Changing Architectural Education: Towards a New Professionalism; Spon Press: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks, R.; Barak, R. Teaching Building Information Modeling as an Integral Part of Freshman Year Civil Engineering Education. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2010, 136, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abioye, O.F.; Oyedele, L.O.; Akanbi, L.; Ajayi, A.; Davila Delgado, J.M. Artificial intelligence in the construction industry: A review of present status and future innovations. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 103299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibert, C.J. Sustainable Construction: Green Building Design and Delivery, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, M. Does active learning work? A review of the research. J. Eng. Educ. 2004, 93, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D.A. Educating the Reflective Practitioner; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, P.; Fisher, K.; Gilding, T.; Taylor, P.G.; Trevitt, A.C.F. Place and space in the design of new learning environments. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2000, 19, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, H. The architectural review: A study of ritual, acculturation and reproduction in architectural education. Arts Humanit. High. Educ. 2006, 5, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkwein, J.F.; Lattuca, L.R.; Terenzini, P.T.; Strauss, L.C.; Sukhbaatar, J. Engineering Change: A Study of the Impact of EC2000. Int. J. Eng. Ed. 2004, 20, 318–328. [Google Scholar]

- Luckin, R.; Holmes, W.; Griffiths, M.; Forcier, L.B. Intelligence Unleashed: An Argument for AI in Education; Pearson: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kolmos, A.; De Graaff, E. Problem-based and project-based learning in engineering education. In Cambridge Handbook of Engineering Education Research; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 141–161. [Google Scholar]

- Eastman, C.; Teicholz, P.; Sacks, R.; Liston, K. BIM Handbook; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, J. Virtual Reality and the Built Environment; Architectural Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Succar, B. Building information modelling framework. Autom. Constr. 2009, 18, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strategy Leadership. Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle. Available online: https://strategy-leadership.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Kolbs-Experiential-Learning-Cycle.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Ahmed, Y. Yasmeen Ahmed, Gold Medalist, PhD, Architect, Post Doc|LinkedIn. 2026. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/ (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Winkelmes, M.A. Transparency in Teaching: Faculty Share Data and Improve Students’ Learning. Lib. Educ. 2013, 99, n2. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, J.A. Reflection in Learning and Professional Development; RoutledgeFalmer: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, H. Facilitating Critically Reflective Learning: Excavating the Role of the Design Tutor in Architectural Education. In Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education; Academia: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004; Volume 2, pp. 101–111. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/2465937/Facilitating_critically_reflective_learning_excavating_the_role_of_the_design_tutor_in_architectural_education (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Gray, C. Inquiry through practice. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 1996, 15, 232–243. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, S.; Shreeve, A. Art and Design Pedagogy in Higher Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rodwell, D. Conservation and Sustainability in Historic Cities; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Project Management Institute. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 7th ed.; PMI: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Auto Desk. Buy Autodesk Software|Get Prices & Buy Online|Official Autodesk Store. Available online: https://www.autodesk.com/ (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Fidan, I.; Chitiyo, G.; Singer, T.; Moradmand, J. Additive Manufacturing Studios: A New Way of Teaching ABET Student Outcomes and Continuous Improvement. In Proceedings of the 2018 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 24–27 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- AIA National, AIA California Council. Experiences in Collaboration: On the Path to IPD. Available online: https://gsappworkflow2010.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/experiences-in-collaboration.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Nasir, O. AI Education in Architecture: Revolutionizing Learning. Available online: https://parametric-architecture.com/ai-education-in-architecture/?srsltid=AfmBOoptnqays_JPU97dVEiziU2Wns66nVzoHDrpfY8DYhGY1QWVgeXz (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Stanford University. Architectural Design program requirements. In School of Engineering Undergraduate Handbook; Stanford Engineering: Stanford, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://ughb.stanford.edu/majors-minors/architectural-design-program (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- School of Architecture, Syracuse University. Arc 409: Integrated Building Design Studio Syllabus; Internal Document; Syracuse University: Syracuse, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Quality Matters. Quality Matters Higher Education Standards. Available online: https://www.qualitymatters.org/qa-resources/rubric-standards/higher-ed-rubric (accessed on 7 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.