Abstract

Urbanization and industrialization have led to the coexistence of winter haze and summer heat island in some cities in northern China, but the mitigation effect of ventilation corridors is lack of quantitative evaluation. This paper introduces circuit theory into urban climate research. Taking Shenyang as a case study, it comprehensively employs three-dimensional urban landscape pattern indices (including SVF, FAD, and Z0) to guide ventilation corridor construction, establishes an analytical framework for PM2.5 and LST, and quantifies the environmental benefits of ventilation corridors. The results show that the corridor generated by circuit theory can make 65.14% of path PM lower than the average level of the city; Among the 7 exit paths of wind corridors, the surface temperature of 4 channels is lower than the average level of the city. FAD is positively correlated with Z0 (R2 = 0.7) and negatively correlated with SVF (R2 = 0.61). Meanwhile, the circuit theory model identifies eight pinch points along ventilation paths. CFD software is employed to simulate atmospheric environments for six typical building layouts to guide subsequent urban planning. Therefore, the reasonable layout of urban morphology indicators and the construction of reasonable ventilation corridors can effectively control the atmospheric particulate pollution and the heat island effect in summer.

1. Introduction

Rapid urbanization has rendered Chinese cities increasingly vulnerable to two dominant atmospheric stressors: pervasive air pollution and intensifying urban heat-islands (UHI) [1,2,3]. In Northeast China, particulate matter (PM) pollution routinely exceeds national and WHO benchmarks during the winter heating season, severely degrading air quality [4,5,6]. In summer, UHI intensifies local thermal extremes, disrupts the urban water cycle, and creates meteorological conditions conducive to the formation and accumulation of secondary aerosols, thereby increasing the PM2.5 concentration [7,8,9]. A significant correlation exists between these two atmospheric environmental issues [9,10]. Both PM pollution and UHI pose direct or potential threats to human health, necessitating our utmost attention and effective collaborative measures for governance [11,12,13,14].

To address the intertwined challenges of urban air pollution and UHI, urban-planning scholars have tested a wide spectrum of mitigation measures. Among them, city-level aeration strategies are increasingly recognized as a promising lever [2,15,16,17]. Constructing ventilation corridors not only prevents heat from accumulating inside the building complex but also channels fresh upwind air into the street canyons [18,19,20]. Coordinating the three-dimensional urban fabric to create such corridors has thus become an effective means of reshaping the local wind–thermal environment [21,22]. Although a growing number of countries and regions have embarked on corridor design under calm or light-wind conditions, most projects have targeted summer heat-islands only [17,23,24,25]. Most cities in Northeast China experience severe winter smog and pronounced summer heat islands, rendering ventilation corridors essential [5,26,27,28]. Wind speed exhibits an inverse relationship with PM concentration, whereas temperature demonstrates a direct correlation [29,30]. This relationship implies that a higher frequency of calm-wind conditions in urban areas will exacerbate air-quality degradation [31,32].

Currently, researchers are progressively refining the methods for constructing ventilation corridors, moving from the macro to the micro scale. To obtain high-resolution regional ventilation corridors, urban canopy models are frequently integrated with the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model for atmospheric simulations [33,34,35,36]. At the mesoscale of urban area, the least cost path (LCP) method is commonly used for simulation [37,38,39,40]. At smaller scales such as neighborhoods and communities, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and wind tunnel tests are often used for small-area wind corridor design [41,42,43]. However, at larger scales, due to limitations in computer power and experimental costs, the other two methods except LCP have certain limitations [44].

In ecology, LCP is commonly used to identify connectivity between animal habitats and species migration [45,46]. Subsequently, this method has been introduced into the construction of wind corridors, with the inlet as the “source point” and the outlet as the “destination point” [37,47]. The relevant landscape-pattern indices of the city are used as the cost grid, which includes three-dimensional building indicators such as floor area ratio, sky view factor (SVF), building density, street height–width ratio, and frontal area density (FAD) [48,49]. These indicators characterize the impact of urban building morphology on airflow movement from different dimensions. Extensive empirical studies and theoretical analyses have converged on the view that, among the above metrics, FAD and SVF are the most appropriate [37,50]. FAD, with its precise depiction of the blocking effect on the horizontal direction of airflow, and SVF, which can intuitively and effectively reflect the degree of smoothness in the vertical direction of airflow, both demonstrate more prominent advantages and scientificity compared to other indicators in quantifying urban ventilation resistance and selecting ventilation corridor paths [51]. This provides a more reliable basis for the refined research and planning of urban ventilation environments. However, applying the LCP to wind-corridor mapping entails a fundamental scientific drawbacks. Unlike animals, which can only migrate along a single path from point to point, airflow in nature is not so constrained [52,53]. Once encountering a “branch node”, even if one branch has higher ventilation resistance and energy consumption, some airflow will still choose to pass through other branches [2]. Moreover, the LCP cannot predict the ventilation conditions in areas beyond the predicted path, and can only obtain linear potential ventilation paths rather than surface data. Therefore, new methods need to be introduced to study ventilation corridors.

Circuit theory, as a network-based modeling framework, has demonstrated broad applicability in interdisciplinary connectivity analysis [53]. This theoretical approach has been successfully employed in fields ranging from chemical systems and neural networks to economic and social systems, reflecting the universality of its methodology. The concept of a ‘circuit’ in circuit theory can be conceptually defined as a network structure composed of nodes interconnected by resistive elements, and this structure adheres to the fundamental electrical relationships described by Ohm’s law [54]. Lower resistance results in a greater current under the same voltage. Among them, resistance distance serves as a native metric for characterizing network connectivity [55]. The core feature of resistance distance is its ability to comprehensively reflect multiple paths between nodes: the more paths there are, the smaller the resistance distance. It not only includes the cost of the shortest path, but also the availability of alternative paths, allowing individuals to have more choices without relying on the shortest path. In recent years, its application has further extended into the domain of landscape ecology, where it has been utilized to simulate gene flow dynamics in heterogeneous habitats [56,57,58]. The theoretical foundation for this expansion lies in the profound mathematical correspondence between fundamental electrical quantities—current, voltage, and resistance—and random walk processes. Previous studies have established that these circuit parameters can be rigorously mapped onto random walk models, with an inherent mathematical isomorphism existing between the two, thereby providing a theoretical basis for the validity and explanatory power of circuit theory in modeling ecological flows [59,60]. Circuit theory is based on the continuation of LCP, and the resistance value in this method can be perfectly replaced by the cost grid in the LCP. However,, the actual movement process is conceptually different. In short, the LCP aims to answer “Where is the optimal path?”, while circuit theory is dedicated to addressing “What is the overall level of landscape connectivity?” [37,61,62].

In recent years, some researchers have used circuit theory to try to construct urban ventilation corridors, and verified them with the mitigation of UHI in China [51,63]. The ventilation system of a city can be analogized with the electrical system to study the urban wind and heat environment. In this model, the wind corridor is understood as a conductor that guides the flow of air, and the buildings and structures on the surface are equivalent resistance elements that generate resistance to the wind. The research on circuit theory in urban ventilation is in its infancy, and scholars have begun to study it in 2020 [51].The circuit theory model has been applied to analyze ventilation corridors and surface temperatures in four major Chinese cities, demonstrating a quantifiable reduction in urban heat island intensity by 2.11–3.22 °C [40]. In a focused study of Wuhan’s main urban area using the Circuit VRC model, ventilation corridor areas were found to mitigate heat island effects 46.3% more effectively than non-corridor areas [2]. Subsequently, in follow-up studies, researchers conducted wind environment simulations using an improved current model. This model effectively mitigated the UHI, and the simulation results were validated and analyzed using CFD [63].These findings collectively confirm that the circuit theory model serves as an effective tool both for identifying ventilation corridors and for quantifying their regulatory impact on the urban thermal environment [64,65].

This paper constructs a high-resolution ventilation resistance surface using urban landscape pattern indices and simulates potential ventilation corridors based on the circuit-theory model. Subsequently, by coupling the winter PM2.5 spatial distribution with summer land-surface temperature (LST) across Shenyang, we construct a multidimensional verification framework to quantitatively evaluate the ventilation efficiency of the simulated corridors and their contributions to mitigating particulate pollution and weakening the urban heat island. Furthermore, utilizing the current-density and cumulative-resistance distributions of the circuit-theory model, we accurately identify key “pinch-points” along the corridors. Coupling these locations with the heterogeneity of urban landscape components provides precise spatial coordinates for urban-pattern optimization.

2. Study Area and Data

2.1. Study Area

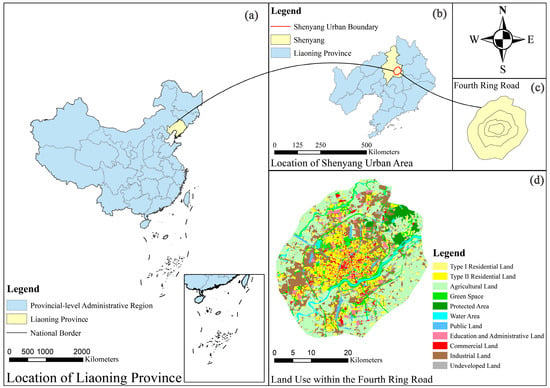

This paper selected Shenyang, the capital of Liaoning Province (122°25′ E–123°48′ E, 41°11′ N–43°02′ N), as the research area (Figure 1). The municipality covers a total area of 12,948 km2, of which the built-up zone occupies 3495 km2 and the area within the Fourth Ring Road amounts to 1227.68 km2. The study area encompasses nine administrative districts: Shenhe, Heping, Dadong, Tiexi, Huanggu, Yuhong, Hunnan, Shenbei New Area, and Sujiatun. Shenyang is designated as “the capital of Liaoning Province, a major central city in Northeast China, an advanced equipment-manufacturing base, and a National Famous Historical and Cultural City”. As the provincial capital of China’s traditional industrial heartland, Shenyang experiences severe winter haze and a pronounced summer UHI [66,67,68,69,70].

Figure 1.

Location map of the study area. (a) The location of Liaoning Province in China; (b) The location of the research area in Liaoning Province; (c) Fourth Ring Road Area of Shenyang City; (d) Land use map of the Fourth Ring Road in Shenyang City.

A temperate semi-humid continental monsoon climate prevails in Shenyang, with pronounced seasonal shifts in prevailing wind direction between winter and summer [4,71,72]. Spring and autumn are brief, winter is cold and protracted, while summer is hot and wet. The annual mean wind speed is 2.9 m/s—moderate on the national scale [73]. To maximize the efficiency of ventilation corridors, continuous linkages among urban green spaces, rivers and open areas must be strategically preserved and enhanced.

Therefore, this study develops a spatial model of urban ventilation corridors and systematically analyzes their regulatory effects on the wind–heat environment coupling mechanism, aiming to provide a scientific basis for urban planning decisions under the guidance of wind and heat safety principles.

2.2. Data Sources

The construction of urban ventilation corridors can take into account the two urban ecological environmental problems of UHI in summer and haze weather in winter in Shenyang. For these two environmental problems, two representative indicators for the construction of ventilation corridors are selected for analysis, namely SVF and FAD.

2.2.1. PM2.5 Concentration Level

Building on the authors’ previous work, Sniffer4D mobile sensors were deployed on five taxis to carry out continuous monitoring throughout the heating season. The fishnet layer, comprising 500 m × 500 m cells, was generated through the Create Fishnet tool in QGIS 3.16.; normalized observations were spatially averaged within each cell to eliminate overlap-induced bias, yielding the horizontal PM2.5 distribution pattern [29].

2.2.2. LST

This study employed the Google Earth Engine (GEE) cloud computing platform and utilized Landsat 8 Collection 2 Tier 1 surface reflectance data to retrieve the land surface temperature (LST) for Shenyang during the summer of 2020, based on the Radiative Transfer Equation (RTE) method.

2.2.3. Urban Land Use and Building 3D Data

The basic building dataset for urban landscape-pattern analysis comprises building footprints and heights. Vector layers were extracted from QuickBird imagery using software Barista 4.2 [74]. The landscape pattern index, such as SVF, FAD, and floor area ratio were all derived through calculations in QGIS.

3. Methods

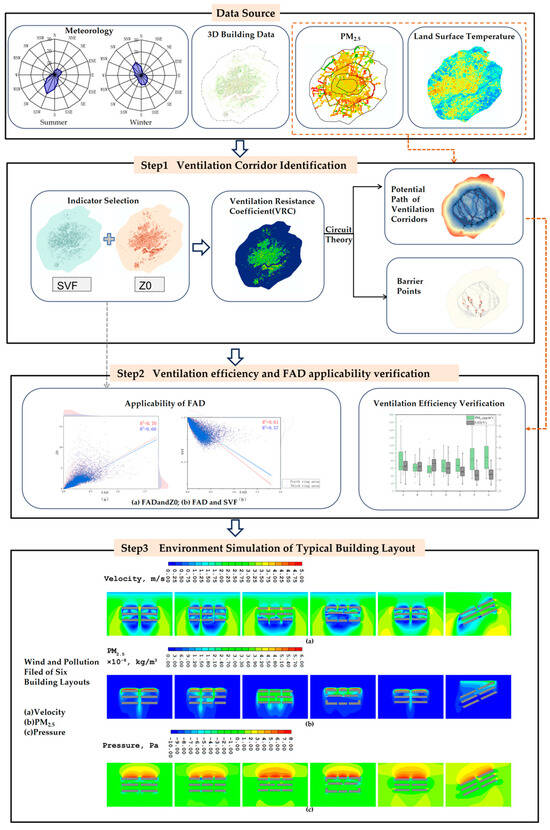

This research aims to measure the effects of ventilation corridors on urban wind-thermal conditions using quantitative methods. Circuit-theoretic modeling was applied to replicate ventilation corridor formation, with the cost path grid and ventilation resistance coefficient (VRC) derived from SVF and roughness length (RL) parameters. Seasonal prevailing wind directions (winter and summer) were employed to determine ventilation corridor paths and simulate airflow barriers. Finally, PM2.5 concentrations and LST served as validation data. The technical roadmap is shown below (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Research technical route.

3.1. Comprehensive Evaluation of Urban Ventilation Potential

Urban ventilation resistance depends on both RL and SVF. Based on their definitions and equations, this study employed VRC to quantify urban ventilation resistance, as follows:

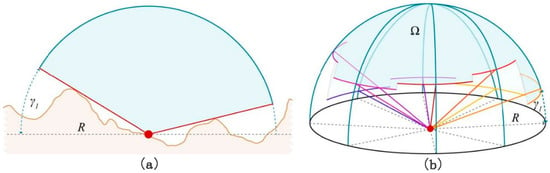

SVF is extensively employed in summer UHI research to quantify spatial openness [21,75]. The calculation of SVF is based on the three-dimensional building vector data of Shenyang and is obtained through the relevant calculation of building height [76,77,78]. The calculation formula and principle are shown in the figure (Figure 3).

where Ω denotes the sky exposure solid angle (rad); ϕ represents the horizontal bearing (rad); indicates the topographic elevation effect on sector i (rad); n stands for the number of azimuthal divisions; and SVF is dimensionless ranging from 0 to 1 [21].

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of SVF [77]. (a) The visible sky proportion (Ω) from a planar view; (b) Computation of the horizon elevation angles () in n directions((eight are presented here) within a search radius R.

Using the QGIS platform, building footprints within the Fourth Ring Road of Shenyang and the ring road boundary were loaded into ArcMap. The SVF calculation formula was input into the Field Calculator through a workflow involving raster conversion, buffer creation, and intersection area calculation. A point radius of 10 m and a grid size of 20 m were adopted, resulting in a spatial distribution map of urban SVF at a 20 m spatial resolution.

FAD is a key morphometric indicator widely used to quantify the aerodynamic roughness of urban surfaces [79,80].The windward area is determined by both building layout and wind direction. Windward surface density λf(θ) quantifies the proportion of aggregate frontal projected building area ΣA(θ) relative to total land area At over a specified domain, and the relevant formula is expressed as:

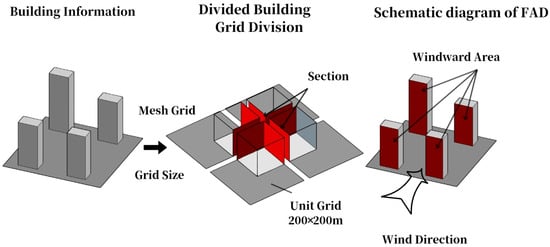

Although scholars have introduced the concept of “effective windward area” in estimating the FAD of Hong Kong to eliminate the impact of front row buildings on the sheltered area, this method still assumes the high-density and extremely limited land pattern of Hong Kong, and its applicable scenario is significantly different from the spatial scale of most inland cities in China [81]. For the spatial form of Shenyang, reasonable requirements have been made for the floor area ratio and daylighting of buildings in the regulatory detailed planning stage, and the “effective” windward area is not applicable in Shenyang. Directional sensitivity of FAD was pronounced, peaking in effectiveness for Shenyang’s dominant wind. Therefore, in this study, the occlusion between the front and rear buildings within the same grid was not considered. The algorithm is shown in the figure (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Illustration of the spatial layout for the algorithm for calculating FAD.

This paper used C language programming and QGIS secondary development plug-in for operation. The calculation principle is as follows. Grids of 200 × 200 m were generated to partition the study area. The grid was used as the calculation unit to traverse the buildings in the grid and calculate the windward area of each building in the given wind direction. In order to alleviate the PM pollution in winter and the UHI in summer, the dominant wind directions (northwest wind in winter and southwest wind in summer) of Shenyang in two seasons were weighted to obtain the upwind density index of each grid.

RL is the position where the wind speed on the wind speed profile is zero. Surface roughness elements and terrain features impede near-surface airflow, elevating the zero-wind-speed level to a height above ground termed RL [15,82,83].

Urban surface roughness estimation followed the morphological framework of Grimmond, with the computational formula given by:

where Zd, RL, and Zh denote zero-plane displacement height, roughness length, and roughness element height (all in m), respectively; and are their normalized counterparts; Uh and u* represent wind speed and friction velocity, respectively; and FAD signifies frontal area density.

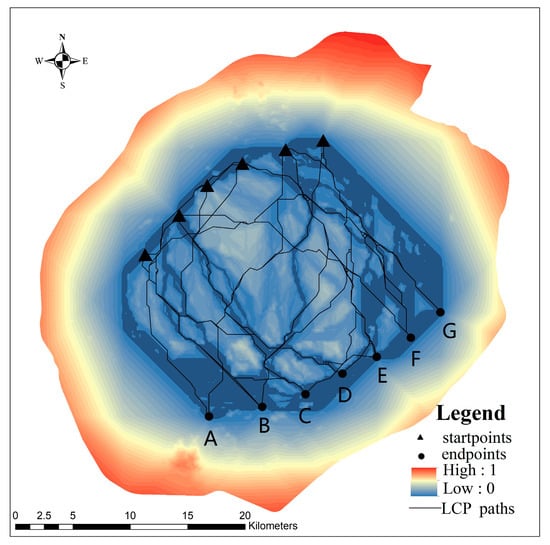

3.2. Methodology for the Generation of Urban Ventilation Corridors

Based on a comprehensive consideration of the urban three-dimensional architectural pattern and the urban meteorological environment, this study used circuit theory to generate the corridor. Circuit theory research is based on three basic concepts, namely current, voltage and resistance, I = V/R [58,84]. Wind pressure, airflow, and obstructing buildings are analogous to voltage, current, and resistance, respectively, constituting a comparable physical framework [51,63].The air inlet can be regarded as a high-voltage node similar to the voltage in the circuit, while the air outlet corresponds to a low-voltage node. The higher the current density, the greater the importance of this area for urban ventilation. In order to maximize the wind pressure difference, the layout of air inlets and outlets should be scientifically planned in full combination with the local dominant wind direction. The east–west Hunhe River acted as a natural main wind channel; therefore, this study focused on ventilation along the northwest-southeast and south–north axes. At the same time, in addition to the above elements, it can also generate pinch points and obstacle points of air flow [53].

When the resistance of a grid element tends to infinity, similar to the area where buildings are densely distributed, the wind will not pass smoothly. The degree of wind resistance of buildings can be quantified as the ratio of RL to SVF, that is, VRC. Using the aforementioned voltage and resistance configurations, the Linkage Mapper toolbox was employed, utilizing its Build Network and Map Linkages modules to plan ecological corridors. The Pinchpoint Mapper tool was subsequently invoked to simulate current conduction between inlet and outlet vents based on circuit theory, thereby identifying key connectivity points areas within the corridors through the calculation of current density; Finally, with the help of Barrier Mapper, potential obstacle points were located to provide decision-making basis for subsequent wind and heat environment optimization and urban space intervention. The parameters were configured as follows: the number of connected nearest neighbors was set to 4; the network adjacency method was selected as Cost-Weighted & Euclidean; the CWD cutoff distance was set to 3000; and the Circuitscape mode for raster centrality calculations was set to All-to-one [49,85].

Circuit theory-derived ventilation corridor paths were overlaid on LST and PM2.5 spatial distribution maps, and the potential path is converted into the point data with a distance of 20 m. QGIS is used for spatial counting and statistics. By setting the control group settings, taking the average value of thePM2.5 concentration level and the LST in the Third Ring Road of Shenyang as the reference, this study made a systematic statistics and analysis of the atmospheric environmental quality on the corridor path through each air outlet.

3.3. Optimization of Ventilation Corridors Based on Barrier Recognition

At the current overall planning stage of ventilation corridor construction in Shenyang, although the Urban Ventilation Corridor has been incorporated into the municipal ecological network system, and potential corridors have been preliminarily identified using the LCP method, spatial obstacles in the LCP model are still represented implicitly through “impedance accumulation.” This approach lacks the ability to explicitly extract obstacle nodes with high positional accuracy. To address this limitation, a circuit theory model will be introduced. This model transforms the landscape resistance matrix into a node-edge equivalent conductance network and uses current density distribution to quantitatively identify “bottlenecks” or “fractures.” Consequently, it can explicitly generate a spatial distribution map of obstacle points, providing a precise and actionable basis for subsequent urban design optimization [40].

3.4. CFD Simulation

CFD simulation restores atmospheric turbulence according to the actual scale of the building complex, and gradually establishes a mathematical model using the turbulence model built into the software, combined with input boundary conditions and initial conditions. Currently, CFD is mostly used for wind environment simulation at the scale of urban blocks, residential areas, and individual buildings [86,87].This paper used the standard k-ε model to simulate the atmospheric environment of building clusters (k = 0.42, Z = 0.22). The exit boundary was set to a free outflow boundary. The bottom of the computational domain was set as a wall boundary condition, using a fully rough wall function with the same roughness coefficient as Z0. The inflow boundary condition was defined by the prevailing northerly winter wind, having a speed of 2.8 m/s. The computational grid was constructed using the built-in structured grid (H-Grid) generator in the CFD software OpenFOAM 8.0. The computational domain was partitioned into two distinct zones: a finely resolved core region enclosing the central building cluster and a peripheral buffer zone representing far-field conditions. Following grid generation, a systematic quality evaluation and a mesh sensitivity analysis were performed.

4. Results

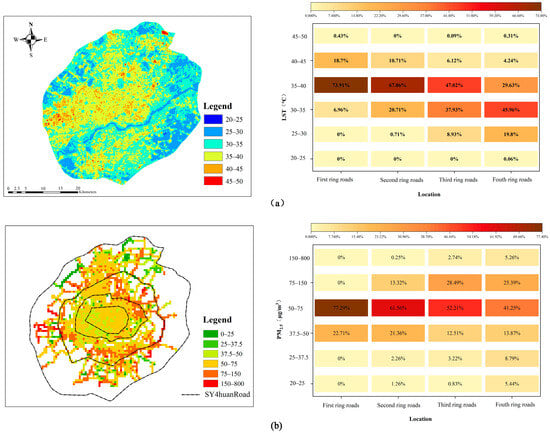

4.1. Ventilation Efficiency Verification

In summer, the mean temperature inside the Fourth Ring Road reached 34.39 °C. Temperatures in the first, second and third ring roads clustered between 35 °C and 40 °C, whereas 45.96% of the Fourth Ring Road area lay in the milder 30–35 °C interval (Figure 5a). This steady outward decrease from the inner core to the urban fringe underlined a pronounced summer UHI.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution and statistics of LST and PM2.5. (a) LST; (b) PM2.5.

Normalized particle-concentration data were averaged for every 500 m × 500 m grid to map the spatial pattern of PM2.5 (Figure 5b). Winter-mean PM2.5 within Shenyang’s Fourth Ring Road was 68.85 µg m−3; the fraction of the area exceeding 50 µg m−3 peaked outside the Third Ring Road, while the 50–75 µg m−3 band dominated every ring from the first to the fourth. Overall, particulate pollution in the city was moderate.

We counted the air outlets as different units (Figure 6) and quantitatively analyzed the distribution of PM2.5 and LST along the potential air corridor paths (A–G). The path with C as the outlet had the lowest average PM2.5 concentration, while the path with G as the outlet had the highest, with a difference of 32.79 μg/m3. The average PM2.5 concentration along 65.14% of the paths was lower than the urban average. From outlet A to outlet G, temperature showed a gradual downward trend. The path with the lowest average temperature was the one with outlet F, at 32.44 °C. Among the seven outlets, the average temperature of four paths was lower than the urban average. Both UHI intensity and particulate pollution levels were reduced through ventilation corridor implementation.

Figure 6.

PM2.5 concentrations and LST along distinct outflow routes.

Using the seven outlets (A–G) as the grouping factor, one-way ANOVA was performed on sampled land-surface temperature and PM2.5 concentration along each path to test whether inter-outlet differences exerted a significant effect on the two variables (Figure 6). Although both temperature and PM2.5 concentration exhibited pronounced inter-group disparities (p < 0.001), the between-group effect size for temperature (η2 = 0.115, medium–small) was far larger than that for PM2.5 (η2 = 0.020, small). This indicated that corridor attributes explained 11.5% of the spatial variance in temperature but only 2.0% of the variance in PM. In other words, ventilation corridors exerted a greater influence on the spatial distribution of temperature than on that of PM2.5. Non-pollutant factors co-varying with corridor structure—such as vegetation cover, building density, and underlying surface properties—were likely to exert a more pronounced spatial buffering or amplifying effect on temperature.

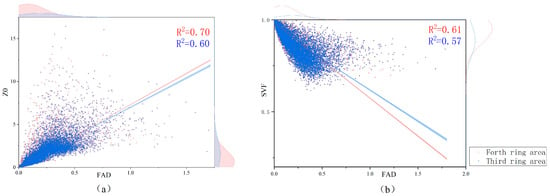

4.2. Results of Urban Ventilation Corridor Indicators

The SVF, RL, and VRC in Shenyang exhibited pronounced spatial heterogeneity, with all three indices bounded between 0 and 1. Within the Fourth Ring Road, their mean values were 0.95, 0.65, and 0.01, respectively.

SVF ranged from 0.08 to 1, with higher values toward the city center and a gradual outward decrease (Figure 7a). RL varied from 0 to 18.61 m; high values occurred in the old cores of Tiexi and Huanggu districts inside the Second Ring Road and in the river-front development zones south of the Hunhe River (Figure 7b). The former reflected the low-rise, high-density, and irregular urban fabric of historically built-up areas, while the latter represented the recent clustered development model characterized by high-rise, large-volume buildings along the riverfront. Together, these two types of areas constituted typical features of the three-dimensional urban form.

Figure 7.

Spatial distributions of three landscape patterns. (a) SVF; (b) RL; (c) VRC.

The 200 m resolution VRC map (Figure 7c) showed a spatial pattern largely consistent with that of RL. High ventilation-resistance zones were concentrated in Hunnan District south of the Hunhe River, riverside residential plots in Heping District, and some areas east of the Second Ring Road. Low-resistance zones were found in open areas such as land beyond the Third Ring Road, the east–west Hunhe River corridor, and several urban parks.

Among the mandatory metrics of urban design, FAD was widely adopted as a readily controllable proxy for development intensity, exerting predictable influences on key ventilation-related parameters. Across the Third and Fourth Ring Roads, a rise in FAD led to a concurrent increase in Z0 (R2 = 0.70 and 0.60; Figure 8a), in contrast to a marked decline in SVF (R2 = 0.61 and 0.57; Figure 8b). These medium-to-strong linear relationships indicated that setting quantitative FAD thresholds could indirectly steer the performance of ventilation corridors, offering planners a straightforward lever for wind-environment optimization.

Figure 8.

Density scatter plots. (a) FADandZ0; (b) FAD and SVF.

4.3. Improving Ventilation Corridors Through Barriers Repair

Guided by circuit theory, we integrated Shenyang’s landscape pattern with its seasonal wind patterns (northwesterly in winter, southerly in summer) to identify ventilation corridors. A total of six air inlets and seven air outlets were positioned at evenly spaced intervals. The ventilation corridor path generated by the model (as shown by the red curve) corresponds to the low resistance channel where current (i.e., airflow) preferentially passes through in circuit theory (Figure 9a). The potential ventilation-corridor paths tended to converge when crossing open spaces such as low-density residential areas or green spaces. Within urban built-up areas the paths produced branches, bends and constrictions, because high-density districts formed inflection points that hindered the approaching flow and deflected the wind direction. It is particularly noteworthy that in the north–south direction, multiple ventilation paths gradually converge into a comprehensive main corridor, which ultimately leads to outlet B. This corridor directly traverses the urban core area, forming a critical ventilation axis that connects the northern and southern wind sources with the internal urban heat island region.

Figure 9.

Potential path analysis of ventilation corridors. (a) Spatial distribution of ventilation corridors; (b) Identification of barrier points and pinchpoints; (c) Obstacle point details.

Using the natural-breaks method, we divided barrier-point values into five classes; resistance > 1.12 was denoted as “very high,” and the maximum value reached 2.19. We quantified their impact on the airflow corridors and identified eight primary barriers (Nos. 1–8) along the potential routes (Figure 9b). These barriers appeared chiefly as patchy or belt-like clusters of urban buildings, concentrated on the southern paths, and created several “high-density building resistance belts” on the routes leading to outlets B and C. High-resolution imagery and urban 3D architectural patterns revealed that barriers 2, 3 and 4 lay within urban-renewal zones: although high-rises were sparse there, enclosed arrays of low-rise shanty and industrial buildings severely reduced ventilation efficiency, making them priority targets for redevelopment (Figure 9c). Based on the natural breaks method applied to the Connectivity Restoration Potential, the study area was classified into five priority levels of ecological pinch points. Spatial overlay analysis revealed that the pinch point with the highest priority (i.e., the highest current density) completely coincided spatially with the key barrier area identified as Barrier No. 7 by the Barrier Mapper. This spatial overlap indicates that the area not only serves as a structural bottleneck essential for maintaining landscape connectivity, but also represents a critical barrier currently impeding ecological flow, thereby warranting the highest urgency for conservation and restoration efforts.

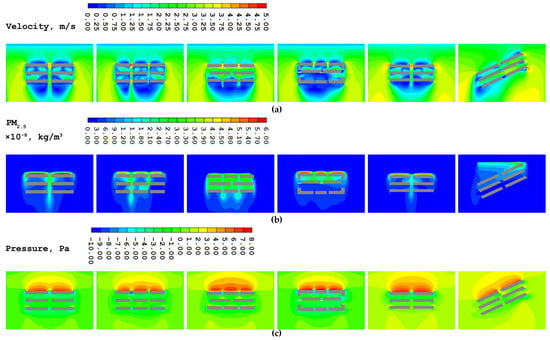

4.4. Atmospheric Environment Simulation of Typical Building Layout

The improvement of the ventilation environment contributed to mitigating the UHI and enhancing pollutant dispersion. The architectural layout in the city had a direct impact on air-corridor obstruction, temperature and particle concentration. However, in actual planning and construction the plot parameters had already been fixed at the regulatory-detail planning stage. Without altering rigid indicators such as plot ratio and building density, we compared and analyzed the wind environment of six residential groups with different layout forms in the experimental design (Figure 10). Layout 1 was a traditional determinant layout that served as the baseline for variants with reduced building length, scattered arrangement, enclosure, height variation (increased folding degree) and inclined arrangement (changed windward area). While satisfying rigid requirements such as reasonable unit size and sunshine spacing, we built the basic models of the six layouts in SketchUp on a plot measuring approximately 235 m × 125 m. The inflow condition was the dominant wind direction in winter-northerly wind with a speed of 2.8 m s−1. A line source parallel to the building complex was set on the North Road as the pollution source of PM2.5. Wind field and PM2.5 were simulated.

Figure 10.

6 architectural layouts.

Dark blue in the wind-speed field indicated the calm-wind zone with low wind speed (Figure 11a). From orange to red, the wind speed gradually increased, reaching a maximum of 5 m s−1. Compared with Layout 1, Layout 2 truncated the buildings into smaller blocks, which reduced and fragmented the wind-shadow zone on the leeward side. In Layout 3, wind speed inside the plot increased (green), but a large calm-wind zone persisted in the outer southern field, where pollutant dispersion was slow. Layout 4 exhibited extensive calm-wind areas both inside the plot and in the outer field. Layout 5 possessed a smaller calm-wind zone than Layout 1 on the 1.5 m horizontal plane and also reduced the calm zone south of the plot. Layout 6, with its smaller building windward area, yielded lower average wind speed and PM2.5 concentration; its low-wind-speed area (0–1 m s−1) was the smallest among the six layouts, while the area with wind speed > 3 m s−1 increased markedly. The ranking of average wind speed from high to low was: Layout 6 > Layout 5 > Layout 3 > Layout 2 > Layout 1 > Layout 4.

Figure 11.

Wind and pollution filed of six building layouts. (a) Wind speed; (b) PM2.5; (c) Wind pressure.

In the comparative analysis of PM2.5 dispersion simulations across six layouts, the average PM2.5 concentrations within Layouts 3 and 4 were relatively high, while Layout 6 exhibited the lowest PM2.5 concentration (Figure 11b). The reasons for these differences can be attributed to the following factors: In Layout 3, the staggered arrangement facilitates faster airflow, which allows line pollution sources from the roads to rapidly enter the site and disperse uniformly within the area. Consequently, the PM2.5 concentration on the roads (i.e., the forecourt of the site) remains relatively low. In Layout 4, due to its enclosed configuration, PM2.5 is obstructed and accumulates on the northern side of the site, exhibiting a dispersion pattern similar to that of Layout 1. Within the building cluster of Layout 4, PM2.5 tends to concentrate in the upper region. The PM2.5 dispersion pattern of Layout 5 at a height of 1.5 meters is comparable to that of Layout 1; however, PM2.5 disperses more rapidly on the forecourt roads in Layout 5. Both wind simulations and PM2.5 dispersion simulations indicate that Layout 6 achieves the optimal performance in terms of ventilation and PM2.5 dispersion. The ranking of average PM2.5 concentrations is as follows: Layout 3 > Layout 4 > Layout 1 > Layout 5 > Layout 2 > Layout 6. Although Layout 3 demonstrates relatively effective PM2.5 dispersion capacity, it is unsuitable for deployment in heavily polluted areas, as it may lead to excessively high pollutant concentrations within the site. Overall, the characteristics of wind speed distribution align closely with those of PM2.5 dispersion.

As observed from the wind pressure contour maps, the six layout configurations exhibit numerous internal negative pressure zones with relatively small overall pressure differentials (Figure 11c). The windward row of buildings demonstrates significant pressure differences between the front and rear surfaces (>5 Pa). Although turbulence intensity is substantially enhanced at building corners, this merely augments localized mass transfer, while the horizontal transport and diffusion of PM2.5 remain constrained. A particularly notable distinction emerges between Layout 1 and Layout 6: an orthogonal building orientation relative to the northerly wind yields lower environmental wind pressures compared to an oblique arrangement.

5. Discussion

5.1. Validation and Uncertainty Analysis of the Circuit Theory

To validate the efficacy and reliability of circuit theory in identifying urban ventilation corridors, we conducted a comparative analysis between the circuit theory model and the classical LCP (Figure 12). Based on identical data for air inlets, outlets, and surface ventilation resistance coefficients, the least-cost path analysis generated 42 single linear optimal paths with the lowest cumulative resistance. The majority of these paths were located within the spatial range of the high current density core corridors identified by circuit theory. This spatial consistency demonstrated that circuit theory could reliably extract the primary potential pathways in the urban ventilation system.

Figure 12.

The superposition of the path generated by LCP and the comprehensive resistance surface of circuit theory.

The analysis indicates that ventilation corridors identified through circuit theory are associated with reduced PM2.5 concentrations along 65.14% of their paths, compared to the urban average. Furthermore, among the seven primary wind corridor outlets, four exhibit LST lower than the citywide mean. The ventilation corridor paths identified through circuit theory demonstrate certain mitigating effects on atmospheric pollution and urban temperature reduction [2,51].

Further comparison revealed that the current density distribution map output by circuit theory more comprehensively delineated continuous zonal areas with higher ventilation potential and multiple secondary connectivity branches, thereby constructing a more complex ventilation network structure. Additionally, the circuit theory model was able to identify localized high-resistance obstacle points within the corridors, providing a basis for subsequent optimization of the urban spatial layout for ventilation.

The primary limitations in applying circuit theory lie in its static and simplified nature: it reduces complex three-dimensional dynamic wind fields to a two-dimensional steady-state resistance network, failing to capture variations in wind direction and turbulent details; the assignment of its core parameters (resistance values) relies on empirical knowledge, introducing a degree of subjectivity; and the model outputs a composite resistance surface rather than actual physical wind volumes, making direct validation challenging [63].

5.2. The Applicability of Circuit Theory in Urban Planning

A key advantage offered by the circuit-theory-based model over the LCP model was its adherence to ventilation corridor fundamentals coupled with its capacity to identify multiple low-resistance pathways from air inlets to outlets [40,47,88]. By constructing a vector-based resistance surface, the circuit model explicitly identified urban areas where air movement was strongly obstructed, offering high-value guidance for refining future building layouts [48].

In the current urban built-up area, the arrangement of building groups is basically stable and cannot be demolished and rebuilt on a large scale. It is unrealistic to form a natural and wide ventilation corridor like forests or rivers [52,89]. Using circuit theory, planners can pinpoint the building masses that block wind flow, enabling targeted micro-scale redevelopment while controlling the building-area frontal-density index along ventilation routes, so that wind-friendly design can be planned and implemented in a practicable way.

5.3. Research Deficiencies

Because the PM2.5 concentration data were derived from single-season mobile monitoring in winter, they were limited in temporal representativeness. The evaluation system only included architectural-form indices and did not couple underlying land-use type, a potentially key parameter. In follow-up studies, seasonal-scale samples of particulate-matter concentrations should be expanded to cover the annual pollution spectrum. NDVI, land-use type and other quantitative indicators should be incorporated into the ventilation-potential-cost framework to improve the model’s explanatory power and predictive accuracy for the coupling mechanism between urban ventilation capacity and pollutant dispersion [90].

During corridor construction, the short spring and autumn transition seasons and unstable wind directions in Shenyang may reduce corridor efficiency in non-monsoon periods. Winters are cold and long, so excessive ventilation should be avoided to prevent increased building energy consumption. This paper employed CFD for conceptual numerical simulation, using an independently constructed idealized building layout model, which therefore cannot be directly validated through on-site monitoring. However, comparison with findings from existing literature on similar layouts shows that the patterns identified in this paper are largely consistent with prior results, thereby indirectly supporting the reliability of the simulation [91,92]. CFD simulations can be further conducted to evaluate how different corridor schemes affect wind speed and temperature [93,94]. Further, building energy simulation tools were employed to quantify energy use along ventilation corridor pathways [95].Among these approaches, reinforcement learning has been demonstrated as an effective method for AI-driven building energy management [96].

The methodological framework developed in this study is suitable for plain cities with gentle terrain. Given that Shenyang exhibits minimal overall slope gradients (<2%) and does not generate significant topographic-induced circulation at the macro scale, elevation was not incorporated as a factor in the construction of the resistance surface. However, it should be noted that if this approach is applied to mountainous cities, elevation must be included as a key resistance factor in the cost raster calculation to accurately characterize the influence of topography on ventilation or ecological connectivity.

6. Conclusions

This paper employs Shenyang’s urban area as a case study to construct urban ventilation corridors by applying circuit theory and ventilation resistance coefficients, with the aim of mitigating the UHI and improving air quality.

We found that the spatial structure of ventilation corridors is significantly more effective at mitigating the UHI than at regulating particulate pollution. Therefore, urban cooling strategies should be synergistically advanced alongside comprehensive measures such as source emission reduction. Compared with the mainstream LCP model currently used to identify ventilation corridors, circuit theory can more precisely identify barrier points and pinch points along corridor paths, providing a basis for subsequent research on optimizing the morphological layout of localized urban spaces. Additionally, the “current density” output by the circuit theory method better approximates ventilation potential rather than providing a quantitative prediction of actual wind speed. To accurately assess whether ventilation corridors suffer from issues such as insufficient wind speed or uncomfortable wind environments, future research could build upon this work by integrating CFD simulations and other methods to conduct quantitative analysis of corridor ventilation efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L. (Chong Liu), J.W. and C.L. (Chunlin Li); methodology, C.L. (Chong Liu); software, C.L. (Chong Liu) and F.S.; validation, C.L. (Chong Liu), M.Z. and X.Z.; formal analysis, C.L. (Chong Liu); investigation, C.L. (Chong Liu); resources, C.L. (Chong Liu) and Y.H.; data curation, C.L. (Chong Liu); writing—original draft preparation, C.L. (Chong Liu); writing—review and editing, J.W.; visualization, C.L. (Chong Liu); supervision, J.W., C.L. (Chong Liu) and Y.C.; project administration, J.W. and M.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.H. and Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number No. 41730647 (funder: Y.H.); the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number No. 52308070 (funder: Y.C.).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PM | Particulate matter |

| UHI | Urban heat-islands |

| LCP | Least cost path |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| SVF | Sky view factor |

| FAD | Frontal area density |

| LST | Land-surface temperature |

| VRC | Ventilation resistance coefficient |

| RL | Roughness length |

References

- Gao, C.; Zhang, F.; Fang, D.; Wang, Q.; Liu, M. Spatial characteristics of change trends of air pollutants in Chinese urban areas during 2016–2020: The impact of air pollution controls and the COVID-19 pandemic. Atmos. Res. 2023, 283, 106539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Dou, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. Circuit VRC: A circuit theory-based ventilation corridor model for mitigating the urban heat islands. Build. Environ. 2023, 244, 110786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, A.; Sheriff, G.; Chakraborty, T.; Manya, D. Disproportionate exposure to urban heat island intensity across major US cities. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, M.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, R.; Huang, N.; Wu, W.; Liu, C. Spatial distribution characteristics of gaseous pollutants and particulate matter inside a city in the heating season of Northeast China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 61, 102302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Hu, Y.; Liu, M.; Li, C.; Zhang, C.; Liu, C. Land use regression modelling of PM2. 5 spatial variations in different seasons in urban areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 743, 140744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Deng, S.; Li, M. Spatial patterns of satellite-retrieved PM2.5 and long-term exposure assessment of China from 1998 to 2016. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulpiani, G. On the linkage between urban heat island and urban pollution island: Three-decade literature review towards a conceptual framework. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, K.; Mabon, L.; Bi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Hayabuchi, Y. Balancing conflicting mitigation and adaptation behaviours of urban residents under climate change and the urban heat island effect. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 65, 102585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shepherd, J.M. Atlanta’s urban heat island under extreme heat conditions and potential mitigation strategies. Nat. Hazards 2010, 52, 639–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, A.M.; Dennis, L.Y. A review on the generation, determination and mitigation of Urban Heat Island. J. Environ. Sci. 2008, 20, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Hoeven, F.; Wandl, A. Amsterwarm: Mapping the landuse, health and energy-efficiency implications of the Amsterdam urban heat island. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2015, 36, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gago, E.J.; Roldan, J.; Pacheco-Torres, R.; Ordóñez, J. The city and urban heat islands: A review of strategies to mitigate adverse effects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 25, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Adams, M. Dry Deposition of Fine Particulate Matter by City-Owned Street Trees in a City Defined by Urban Sprawl. Land 2025, 14, 1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, K.J.; Dikshit, A.K.; Arora, M.; Deshpande, A. Estimating premature mortality attributable to PM2.5 exposure and benefit of air pollution control policies in China for 2020. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, K.; Fang, Y.; Qian, Z.; Sun, Z.; Wang, A. Spatial planning for urban ventilation corridors by urban climatology. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2020, 6, 1747946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Lau, K.K.-L.; Ng, E. Urban tree design approaches for mitigating daytime urban heat island effects in a high-density urban environment. Energy Build. 2016, 114, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.-J.; Ding, L.; Prasad, D. Enhancing urban ventilation performance through the development of precinct ventilation zones: A case study based on the Greater Sydney, Australia. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 47, 101472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, Y. Identification of ventilation corridors through a simulation scenario of forest canopy density in the metropolitan area. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 95, 104595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-M.; Yu, C.-Y.; Shao, L.-Y. Improving the local wind environment through urban design strategies in an urban renewal process to mitigate urban heat island effects. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2023, 149, 05023003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccolo, S.; Kämpf, J.; Scartezzini, J.-L.; Pearlmutter, D. Outdoor human comfort and thermal stress: A comprehensive review on models and standards. Urban Clim. 2016, 18, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ng, E. Quantitative urban climate mapping based on a geographical database: A simulation approach using Hong Kong as a case study. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2011, 13, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, X. Identification and cooling effect analysis of urban ventilation corridors in coastal hilly cities: A case study of Shenzhen. Urban Clim. 2025, 61, 102393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, T.R. Boundary Layer Climates; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Arnfield, A.J. Two decades of urban climate research: A review of turbulence, exchanges of energy and water, and the urban heat island. Int. J. Climatol. A J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2003, 23, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Z.; Wu, C.; Zhao, D.; Xu, X.; Yang, J.; Feng, L.; Sun, Z.; Liu, L. Determining the boundary and probability of surface urban heat island footprint based on a logistic model. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.; Bashir, M.; Zaineb, S. Analysis of daily and seasonal variation of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) for five cities of China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 12095–12123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yan, Q.; Zhang, C. Spatial–temporal distribution characteristics of PM2. 5 in China in 2016. J. Geovisualization Spat. Anal. 2018, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhao, C.; Fan, H.; Yang, Y.; Sun, Y. Toward understanding the differences of PM2.5 characteristics among five China urban cities. Asia-Pac. J. Atmos. Sci. 2020, 56, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Hu, Y.; Chang, Y.; Liu, M.; Xiong, Z.; Chen, T.; Li, C. Spatial patterns and influencing factors of intraurban particulate matter in the heating season based on taxi monitoring. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2022, 8, 2130826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.P.; Millet, D.B.; Marshall, J.D. Air quality and urban form in US urban areas: Evidence from regulatory monitors. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 7028–7035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C.; Cheng, T.; Gu, X.; Shi, S.; Wang, W.; Wu, Y.; Bao, F. Contribution of meteorological factors to particulate pollution during winters in Beijing. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 656, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Xu, C.; Lu, D.; Ye, C.; Wang, Z.; Bai, L. Quantifying the influence of natural and socioeconomic factors and their interactive impact on PM2.5 pollution in China. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 241, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liang, S. Impacts of land cover transitions on surface temperature in China based on satellite observations. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 024010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathsara, K.; Suzuki, N.; Kusaka, H. WRF-UCM simulations of urbanization impacts on land–sea breeze circulations during three heatwaves in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2025, 156, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M. Three-dimensional landscape features impact on urban surface wind velocity during a heatwave: Relative contribution and marginal effect. Urban Clim. 2024, 58, 102227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.-G.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Li, J.-N.; Lin, W.-S.; Dai, G.-F.; Li, H.-R. Application of WRF/UCM in the simulation of a heat wave event and urban heat island around Guangzhou. J. Trop. Meteorol. 2011, 17, 257. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.; Gu, K.; Qian, Z.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, A. Performance evaluation on multi-scenario urban ventilation corridors based on least cost path. J. Urban Manag. 2021, 10, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Deng, W.; Zhang, J.-f. Evaluating mountain water scarcity on the county scale: A case study of Dongchuan District, Kunming, China. J. Mt. Sci. 2019, 16, 744–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Xie, P. A Machine Learning Framework for Urban Ventilation Corridor Identification Using LBM and Morphological Indices. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, A.; Yue, W.; Yang, J.; Li, M.; Xie, P.; He, T.; Zhang, M.; Yu, H. Quantifying the impact of urban ventilation corridors on thermal environment in Chinese megacities. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 156, 111072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, W.; Chen, B.; Chang, M.; Wang, X. Identification of ventilation corridors using backward trajectory simulations in Beijing. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 70, 102889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Lin, P.; Lau, S.S.Y.; Song, D. Influence of site and tower types on urban natural ventilation performance in high-rise high-density urban environment. Build. Environ. 2020, 179, 106960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toparlar, Y.; Blocken, B.; Maiheu, B.; van Heijst, G.J.F. A review on the CFD analysis of urban microclimate. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 80, 1613–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badas, M.G.; Ferrari, S.; Garau, M.; Querzoli, G. On the effect of gable roof on natural ventilation in two-dimensional urban canyons. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2017, 162, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, S.C.; Epps, C.W.; Brashares, J.S. Placing linkages among fragmented habitats: Do least-cost models reflect how animals use landscapes? J. Appl. Ecol. 2011, 48, 668–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etherington, T.R.; Penelope Holland, E. Least-cost path length versus accumulated-cost as connectivity measures. Landsc. Ecol. 2013, 28, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, D.; Chen, H.; Wang, B.; Chen, X. Identifying urban ventilation corridors through quantitative analysis of ventilation potential and wind characteristics. Build. Environ. 2022, 214, 108943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Jian, L.; Ouyang, K.; Liu, X.; Liang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B. Assessment of Ventilation Potential and Construction of Wind Corridors in Chengdu City Based on Multi-Source Data and Multi-Model Analysis. Land 2024, 13, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhong, Q.; Zhang, G.; Yi, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Q. Applying Circuit Theory and Risk Assessment Models to Evaluate High-Temperature Risks for Vulnerable Groups and Identify Control Zones. Land 2025, 14, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Wang, K.; Yang, S.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Fu, Y.; Liu, X.; Run, Y.; Chubwa, O.G. Warming effort and energy budget difference of various human land use intensity: Case study of Beijing, China. Land 2020, 9, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. A New method of simulating urban ventilation corridors using circuit theory. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 59, 102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zhao, L. Assessing the environmental benefits of urban ventilation corridors: A case study in Hefei, China. Build. Environ. 2022, 212, 108810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, B.H.; Dickson, B.G.; Keitt, T.H.; Shah, V.B. Using circuit theory to model connectivity in ecology, evolution, and conservation. Ecology 2008, 89, 2712–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yang, G. How to build a heat network to alleviate surface heat island effect? Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, D.J.; Randi, M. Resistance distance. J. Math. Chem. 1993, 12, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Z.; Min, C. The Construction of Regional Ecological Security Pattern Based on a Multi-Factor Comprehensive Model and Circuit Theory. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2021, 20, 1115–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Shi, J.; Zhao, L.; Ji, T.; Meng, X. Urban ventilation network identification to mitigate heat island effect. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 125, 106364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcrae, B.H. Isolation by Resistance. Evolution 2006, 60, 1551–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, P.G.; Snell, J.L. Random Walks and Electric Networks. In Carus Mathematical Monograph; Mathematical Association of America: Washington, DC, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, A.K.; Raghavan, P.; Ruzzo, W.L.; Smolensky, R.; Tiwari, P. The electrical resistance of a graph captures its commute and cover times. Comput. Complex. 1996, 6, 312–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Li, J. Using Least Cost Path Analysis to Plan a New Bypass Route on Highway 401 to Mitigate Traffic Congestion and Impacts in the City of Toronto, Ontario. Abstr. ICA 2023, 6, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danser, R.A. Applying Least Cost Path Analysis to Search and Rescue Data: A Case Study in Yosemite National Park. Master’s Thesis, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, P.; Yang, J.; Sun, W.; Xiao, X.; Xia, J.C. Urban scale ventilation analysis based on neighborhood normalized current model. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 80, 103746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tian, N.; Chen, A.; Qiu, J.; He, C.; Cao, Y. Identification of a wetland ecological network for urban heat island effect mitigation in Changchun, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 150, 110248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Xia, J.C. Urban ventilation corridors and spatiotemporal divergence patterns of urban heat island intensity: A local climate zone perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 74394–74406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Yao, J.; Niu, J.; Hou, Y. Driving Mechanism of Urban Heat Island Spread in the Central-southern Liaoning Urban Agglomerations, China (2013–2020). Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 28, 100962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Cui, Y.; Yang, J.; Ren, J.; Yu, W.; Xiao, X.; Xia, J. Contribution of suburban land use landscape characteristics to urban heat island intensity at varying gradients in Shenyang. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 18411–18422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Mao, Y.; Ma, Y.; Liao, H. Impact of urbanized atmosphere-land processing to the near-ground distribution of air pollution over Central Liaoning Urban Agglomeration. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 339, 120866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ren, K.; Su, H.; Zhou, C.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. Analysis of air quality changes and causes in the Liaoning region from 2017 to 2022. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1344194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Ren, K.; Wang, J.; Lu, Z.; Lu, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y. Comparative analysis of multi-directional long-distance pollution transport effects on heavily polluted weather in the Liaoning region. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1382233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Zhao, D.; Liu, S.; Yu, W. Study on the virtual reality evolution of modern settlements along Liaohe River. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 236, 03031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zheng, T. Establishing a “dynamic two-step floating catchment area method” to assess the accessibility of urban green space in Shenyang based on dynamic population data and multiple modes of transportation. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 82, 127893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Feng, L.; Wu, K. Air pollutant emission characteristics and HYSPLIT model analysis during heating period in Shenyang, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Hu, Y.-M.; Li, C.-L. Landscape metrics for three-dimensional urban building pattern recognition. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 87, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, J. Intra-urban relationship between surface geometry and urban heat island: Review and new approach. Clim. Res. 2004, 27, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gál, T.; Unger, J. Detection of ventilation paths using high-resolution roughness parameter mapping in a large urban area. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakšek, K.; Oštir, K.; Kokalj, Ž. Sky-view factor as a relief visualization technique. Remote Sens. 2011, 3, 398–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ng, E.; An, X.; Ren, C.; Lee, M.; Wang, U.; He, Z. Sky view factor analysis of street canyons and its implications for daytime intra-urban air temperature differentials in high-rise, high-density urban areas of Hong Kong: A GIS-based simulation approach. Int. J. Climatol. 2012, 32, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burian, S.; Brown, M.; Linger, S. Morphological Analyses Using 3D Building Databases; LAUR020781; Los Alamos National Laboratory: Los Angeles CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Grimmond, C.S.B.; Oke, T.R. Aerodynamic properties of urban areas derived from analysis of surface form. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1999, 38, 1262–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.S.; Nichol, J.E.; To, P.H.; Wang, J. A simple method for designation of urban ventilation corridors and its application to urban heat island analysis. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 1880–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fang, X.; Cheng, C.; Luan, Q.; Du, W.; Xiao, X.; Wang, H. Research and application of city ventilation assessments based on satellite data and GIS technology: A case study of the Yanqi Lake Eco-city in Huairou District, Beijing. Meteorol. Appl. 2016, 23, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Shu, W. A preliminary study on the influence of Beijing urban spatial morphology on near-surface wind speed. Urban Clim. 2020, 34, 100703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarov, Y.V. Circuit theory of Andreev conductance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1994, 73, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qu, Z.; Zhong, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, R.; Yi, Y.; Zhang, G.; Li, X.; Liu, J. Delimitation of ecological corridors in a highly urbanizing region based on circuit theory and MSPA. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 142, 109258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, R.; Rosenlund, H.; Johansson, E. Urban shading—A design option for the tropics? A study in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Int. J. Climatol. A J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2007, 27, 1995–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfour, O.S. Prediction of wind environment in different grouping patterns of housing blocks. Energy Build. 2010, 42, 2061–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Liu, D.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. A least cumulative ventilation cost method for urban ventilation environment analysis. Complexity 2020, 2020, 9015923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, H.; Lai, Y. Modeling airflow dynamics and their effects on PM2. 5 concentrations in urban ventilation corridors of Hangzhou. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 957, 177794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Xiao, H.; Gu, X. Integrating species distribution and piecewise linear regression model to identify functional connectivity thresholds to delimit urban ecological corridors. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2024, 113, 102177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, J.; Li, Y. Ventilation strategy and air change rates in idealized high-rise compact urban areas. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 2754–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Mak, C.M. Effects of wind direction and building array arrangement on airflow and contaminant distributions in the central space of buildings. Build. Environ. 2021, 205, 108234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Qingming, Z. Study on urban Street ventilation corridor based on GIS and CFD: A case study of Wuhan. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2019, 35, 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Yan, T.; Fu, X. CFD simulation technology based analysis on urban wind environment of Shenzhen. Constr. Qual. 2009, 11, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Ma, J.; Dong, Q.; Qian, H. Patient movement and ventilation effects on respiratory aerosol dynamics in hospital corridors: A combined CFD and field study. Build. Environ. 2025, 281, 113225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Chen, R.; Guan, S.; Li, W.-T.; Yuen, C. BuildingGym: An open-source toolbox for AI-based building energy management using reinforcement learning. Build. Simul. 2025, 18, 1909–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.