Abstract

This study develops a numerical model based on a multi-physics coupled finite element method to predict the carbonation depth of hardened alkali-activated slag under accelerated carbonation curing conditions. Drawing on existing literature data, the chemical composition and porosity of alkali-activated slag at different ages were determined under non-carbonation conditions, supported by thermodynamic and kinetic analyses of alkali activation reactions. A differential equation governing CO2 diffusion—incorporating diffusion rate, diffusion coefficient, carbonation reaction rate, and related parameters—was established using Fick’s second law. The influence of humidity and carbonation degree on the reaction rate was quantified, and a correlation between carbonation degree and porosity was derived through thermodynamic analysis. These equations were solved numerically in a two-dimensional domain to predict carbonation depth over time. The results demonstrate that the proposed model, using only raw material composition and curing conditions, achieves reasonable accuracy in predicting carbonation depth.

1. Introduction

The carbonation of cement-based materials is a critical research area due to its dual implications for durability and sustainability. In reinforced concrete structures, carbonation reduces the alkalinity of the concrete cover, degrading the passive film on steel reinforcements and accelerating corrosion, thereby compromising structural longevity [1]. While conventional concrete absorbs carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere at a negligible rate under natural conditions, recent advancements in carbonation curing and CO2 utilization technologies have enabled cementitious materials to play a more active role in carbon reduction [2,3]. For instance, accelerated carbonation curing and the incorporation of CO2 during material processing can significantly enhance CO2 sequestration, offering a promising pathway to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions [4]. Unlike ordinary Portland cement (OPC), which relies solely on gaseous CO2 absorption for carbonation, alkali-activated materials (AAMs) exhibit two distinct carbon sequestration mechanisms: (1) absorption of gaseous CO2 and (2) the use of carbonates as alkali activators. However, carbonate-based activators can impede early-age strength development [5]. Given the prominence of alkali-activated slag (AAS) as a high-performance AAM [6,7], this study focuses on gaseous CO2 absorption as the primary carbonation pathway for AAS.

Extensive research has been conducted on carbonation in OPC systems, encompassing theoretical, experimental, and numerical approaches. For instance, Reddy [8] employed thermodynamic modeling to analyze phase transformations during carbonation, while Greve-Dierfeld [9] reviewed the influence of environmental factors (e.g., humidity, temperature) on carbonation kinetics in blended cements. Shi [10] numerically simulated carbonation in loaded concrete, correlating stress levels with carbonation depth. In contrast, the carbonation behavior of AAMs remains less systematized, owing to the variability in precursor compositions and activators. Divergent findings persist in the literature: some studies report that carbonation enhances AAM compressive strength [11], while others observe the opposite. Similarly, Zhao [12] attributed reduced carbonation resistance to higher calcium content, whereas Rashad [13] suggested the contrary. Discrepancies also exist regarding porosity evolution—Xie [14] found increased porosity after carbonation, while Azar [15] reported densification. These contradictions stem from the complex, coupled processes governing AAM carbonation, including alkali activation, CO2 diffusion, reaction kinetics, and moisture transport, all influenced by material composition and curing conditions.

For AAS, carbonation involves a multi-stage process. Early-age non-carbonated curing ensures sufficient alkalinity for reaction product formation, while subsequent accelerated carbonation curing introduces CO2-driven physicochemical changes. The latter includes CO2 diffusion, dissolution in pore solution, reaction with hydroxyl ions to form carbonates/bicarbonates, and their subsequent interaction with alkali-activated products (e.g., calcium-alumino-silicate-hydrate, i.e., C-A-S-H). Key factors influencing CO2 transport include slag particle size distribution, pore tortuosity, and saturation degree. Volume changes during solid-phase reactions and water consumption/generation further alter porosity and saturation, complicating the system.

To evaluate carbonation resistance, phenolphthalein indicator tests are widely adopted [16,17,18,19]. After accelerated carbonation, the specimen’s cross-section is sprayed with phenolphthalein; regions with pH < 9.5 remain colorless (carbonated), while uncarbonated zones turn purple-red. The depth of the colorless region serves as a proxy for carbonation resistance.

This study proposes a novel multi-physics finite element model to predict carbonation depth in hardened AAS under accelerated curing, addressing critical gaps in existing research. Unlike previous studies that rely on empirical or simplified approaches, our framework integrates thermodynamic analysis and kinetic modeling to systematically capture the coupled physicochemical processes governing carbonation. Specifically, the model uniquely combines thermodynamic analysis, kinetic modeling, and validation against experimental data.

This approach eliminates the need for extensive experimental trials, reducing time and resource consumption while enabling tailored assessments of AAS formulations. By providing a predictive tool for carbonation depth, the study advances the understanding of carbonation mechanisms in AAS and offers practical insights for optimizing material design, enhancing durability, and maximizing the potential of carbonation curing and CO2 utilization technologies for carbon reduction.

2. Methodology

To accurately predict the carbonation depth of alkali-activated slag (AAS), mathematical models were employed to describe the physical and chemical changes of AAS at different stages of non-carbonation curing and carbonation curing. During the non-carbonization curing stage, numerical simulation methods were used to predict the phase composition and porosity of alkali-activated slag material products based on the chemical composition of raw materials, slag particle size distribution, curing temperature, and curing age. The diffusion process of CO2 in AAS during the carbonation curing stage is described by Fick’s second law equation with a source term. Based on this, the AAS carbonation reaction kinetics equation was employed to describe the relationship between carbonation rate, carbonation degree, and carbon dioxide concentration, and combined thermodynamic modeling to determine the relationship between carbonation reaction degree and porosity.

2.1. Reaction Degree Model

According to Zuo’s [20] research, in the AAS reaction, when NaOH solution is used as an activator, the product grows continuously with slag as the nucleation site, and when Na2SiO3 solution is used as an activator, the product uses slag and soluble silicon in the solution as nucleation sites. Therefore, a partial differential equation can be derived to describe the reaction rate of alkali-activated slag materials with respect to pH value, water content, and other parameters, as shown in Equation (1).

where dδ denotes the penetration depth of slag particles over the time interval dt, while k0 is the alkali-activation rate constant. FT represents the influence of temperature on the reaction rate, with its expression in Equation (2). Fw denotes the effect of water content on the reaction rate. When the initial water content w0 exceeds the water requirement wn for complete slag reaction, Fw = 1. When the initial water content w0 is less than required, Fw is the ratio of remaining water wr to required water wn, i.e., Fw = wr/wn. The term [(δtr/δshell)β1]λ represents the effect of the reaction product shell on reaction rate. For sodium hydroxide-activated slag, it is assumed that the reaction products uniformly coat the surface of slag particles. Based on the volume ratio of the reaction products to the slag, the thickness of the product shell can be derived. When the shell thickness is less than the critical thickness δshell, the product shell does not affect slag dissolution, and λ = 0. When δshell exceeds δtr, the product shell hinders slag dissolution, and λ = 1. β1 is a calibration parameter. FpH, slag represents the effect of pH and slag composition on the dissolution rate of slag, with its expression in Equation (3).

where Ea is the chemical reaction activation energy, T is the temperature, and R is the ideal gas constant.

where VSi is the volume of slag containing 1 mole of silicon (in cubic centimeters), while NBO/T is the ratio of the non-bridging oxygen atoms to oxygen atoms in tetragonal coordination. The formula for calculating NBO/T is shown in Equation (4),

When a mixed solution of sodium hydroxide and sodium silicate is used to activate slag, reaction products form with either slag particles or soluble silicon as nucleation sites. The proportion of products nucleated from soluble silicon is positively correlated with the concentration of sodium silicate solution, as shown in Equation (5),

where y is the proportion of products nucleated from soluble silicon, while x is the concentration of sodium silicate solution, and a is the calibration parameter.

The overall reaction degree can then be calculated using Equation (6).

where k is the type of slag particles, ni denotes the number of particles with a radius of ri, and δin,ri represents the penetration depth.

2.2. Carbonation Depth Model

2.2.1. Carbon Dioxide Diffusion

Based on Yu [21] and Mi’s [22] research, Fick’s second law with a source term was employed to model the CO2 diffusion within AAS, as presented in Equation (7).

where C represents the CO2 molar concentration per unit volume, D is the diffusion coefficient, and RC indicates the rate of CO2 consumption per unit volume and per unit time. It should be noted that the product volume includes the volume of the solid, liquid, and gas phases.

Through regression analysis of extensive empirical data [23], the CO2 diffusion coefficient can be obtained. Thiery [24] derived an empirical formula to relate the CO2 diffusion coefficient in unsaturated porous media to saturation and porosity, as shown in Equation (8).

where n represents porosity, and S represents saturation. Based on the relationship outlined in Equation (9) [25], which links the CO2 diffusion coefficient at different temperatures to its value at ambient temperature, the relationship between the CO2 diffusion coefficient, porosity, and saturation across various temperatures can be established.

The GEMS3 software was utilized in combination with the Cemdata18 and MINES thermodynamic databases to model the carbonation reactions in AAS; the relationship between the consumption of alkali-activated reaction products and porosity and pore saturation is therefore derived.

2.2.2. Carbonation Reaction

In modeling the carbonation reaction, it is assumed that the dissolution of CO2 in water, its reaction with water to form carbonic acid, and the dissociation of carbonic acid into carbonate and bicarbonate ions occur simultaneously. Equation (10) presents the relationship between the CO2 concentration within the specimen and its concentrations in the gas phase and aqueous solution.

Based on Henry’s law, the CO2 molar concentration relationship between the gas and liquid phases at standard temperature and pressure is given in Equation (11) [26]. By combining Equations (10) and (11), the relationship between CO2 concentration within the specimen and that in the gas phase can be derived, as shown in Equation (12).

Following the carbonation reaction kinetics model proposed by Saetta [27] for Portland cement, a carbonation reaction kinetics equation for AAS was established in this study, as presented in Equation (13).

where Rp denotes the ratio between the volume of alkali-activated reaction products participating in the carbonation reaction and their volume at the onset of carbonation, while kc is the carbonation coefficient. f1(S) represents the influence of saturation on the carbonation reaction rate, with f1(S) assumed to be equal to the saturation level S. f2(Cw) indicates the effect of CO2 concentration in the pore solution on the carbonation rate, with f2(Cw) assumed to equal Cw. f3(Rp) captures the effect of carbonation reaction extent on the reaction rate, and the specific form of f3(Rp) is provided in Equation (14).

Due to the limited research on the activation energy of carbonation reactions in AAS, the activation energy of the carbonation reaction in AAS is assumed to be comparable to that of the carbonation reaction in cement. The expression for f4(T) is thus proposed as shown in Equation (15) [21].

The carbonation coefficient kc represents various factors that are not directly modeled, and its accurate determination is essential for the numerical modeling of carbonation in cementitious materials [28]. Given the known initial chemical composition, porosity, and carbonation curing conditions of AAS, the carbonation coefficient kc is the sole undetermined parameter for modeling carbonation progression. In this study, it is assumed that the carbonation depth—defined as the distance from the specimen’s surface to the fully carbonated front (100% carbonation)—matches the colorless region depth seen when phenolphthalein is applied to the cross-section of the AAS. Based on Nguyen’s [29] experimental findings, a trial-and-error approach was applied to estimate the carbonation coefficient. By iteratively comparing predicted carbonation depths to measured values, an optimal carbonation coefficient value was determined. This process ultimately yielded an estimated coefficient value of kc = 2 × 10−7.

2.3. Experimental Data

This study references the parameter values from Gao’s [30] research and determines the calibration coefficient a through iterative calculations based on experimental data from Ben Haha’s [31] research. Values of the parameters used in this study are shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

The proportion of slag consumption and hydroxide ion consumption.

Table 2.

Accelerated carbonation conditions.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Verification of the Carbonation Reaction Degree

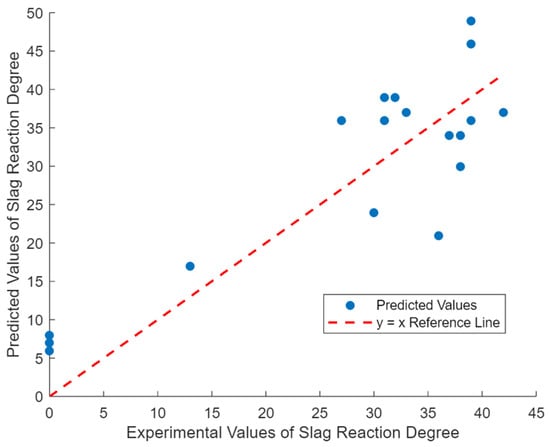

To validate the accuracy of the predicted reaction degree, experimental data from Haha’s study [32] were utilized. Since Haha’s study provided only the specific surface area of the slag without detailing the particle size distribution, this study assumed a Rosin–Rammler distribution for slag particle sizes, employing a typical slag particle size distribution in the prediction model. The predicted reaction extent was calculated using the chemical composition of the alkali-activated slag (AAS), slag particle size distribution, and curing temperature as inputs. As shown in Figure 1, the comparison between the predicted and experimental values for slag reaction degree yielded a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.73, indicating reasonable agreement.

Figure 1.

Experimental and predicted values of AAS reaction degree.

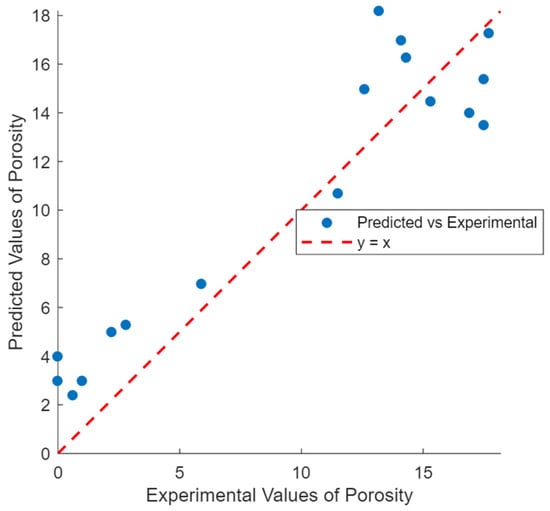

Additionally, thermodynamic modeling was used to calculate the volume of solution within the specimen, assuming that the solution volume equals the pore volume. This allowed for the estimation of the pore volume. Figure 2 compares the predicted porosity with experimentally measured values, achieving an R2 of 0.82, further validating the model’s accuracy in predicting porosity.

Figure 2.

Experimental and predicted values of porosity.

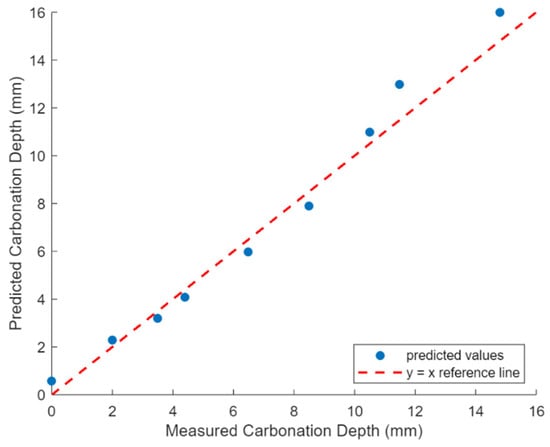

3.2. Verification of the Carbonation Depth Predication

The carbonation depth prediction model was validated using experimental data from Nguyen’s study [33]. The initial chemical composition of AAS and the slag particle size distribution were provided as inputs to the model. The model predicted the proportions of reaction products, porosity, and pore saturation in the AAS specimens at 28 days. Using these predictions, the carbonation depths of the specimens at various ages were calculated. Figure 3 demonstrates the comparison between the predicted and experimental carbonation depths, with the model achieving an R2 of 0.97, indicating high predictive accuracy.

Figure 3.

Comparison of experimental and predicted carbonation depth.

3.3. Model Validation and Limitations

The model’s predictions were validated against experimental data from independent studies, demonstrating strong agreement for reaction degree, porosity, and carbonation depth. However, certain limitations should be noted: (1) The model assumes a Rosin–Rammler distribution for slag particle sizes, which may not capture the full variability in particle size distributions across different slags. (2) The assumption that solution volume equals pore volume may oversimplify the complex relationship between pore structure and solution distribution in AAS. (3) The model relies on input parameters such as chemical composition and curing conditions, which may vary in practice and affect accuracy. (4) The validation was limited to specific datasets, and the model’s performance under broader conditions (e.g., different curing environments or slag sources) remains to be tested.

4. Conclusions

This study consolidates previous findings on the reaction kinetics of alkali activation and carbonation in alkali-activated slag (AAS) to develop a numerical model for predicting carbonation depth. The model incorporates input parameters such as the chemical composition of raw materials, particle size distribution of slag, curing conditions, and time, achieving satisfactory accuracy in its predictions. While the model is specifically applied to AAS, its framework is adaptable to other types of alkali-activated binders, offering a valuable tool for evaluating the carbonation resistance of alkali-activated materials (AAMs) without extensive experimental testing. This capability facilitates the broader application of AAMs in practical engineering contexts.

However, discrepancies in predicted carbonation depth were observed and are largely attributable to the following factors:

- (1)

- Moisture Evaporation: The effect of moisture evaporation on the reaction process during both non-carbonation and carbonation curing stages was not accounted for.

- (2)

- Crack Formation: The impact of cracks within the AAS specimens on the diffusion coefficient of carbon dioxide was omitted.

- (3)

- Pore Tortuosity: The influence of pore tortuosity, which affects the diffusion path and the effective diffusion coefficient of carbon dioxide, was not considered.

- (4)

- Pore Structure: The ratio of closed to open pore volumes, which affects gas permeability, was disregarded.

- (5)

- Drying Shrinkage: The influence of drying shrinkage on the porosity of the specimen was not included in the analysis.

To improve the accuracy and applicability of the model, some areas such as incorporating moisture evaporation, crack formation and propagation, pore tortuosity and structure, drying shrinkage effects are recommended for further investigation. By addressing these limitations and incorporating the suggested improvements, the model can be refined to provide more accurate and reliable predictions, ultimately enhancing the understanding and practical application of AAMs in carbonation-prone environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, resources, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition: X.Z.; Investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization: K.W., Y.L. (Yu Lei), L.Z., and Y.L. (Yang Liu). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Shenzhen Science and Technology Plan Projects, grant number GJHZ20220913143007013 and grant number KCXST20221021111408021. The support provided by the laboratory staff is gratefully acknowledged.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be provided upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Lei Zhang and Yang Liu are employed by the Shenzhen Construction Engineering Group Co., Ltd. Author Yu Lei is employed by the China Jiangxi International Economic and Technical Cooperation Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Fuhaid, A.F.A.; Niaz, A. Carbonation and Corrosion Problems in Reinforced Concrete Structures. Buildings 2022, 12, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Lin, R.S.; Wang, X.Y. Semi-wet CO2 mineralized modified wollastonite: Application in high-early strength cement and comparative analysis with common supplementary cementitious materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2025, 164, 106254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Ishak, S.; Zhang, G.Z.; Wang, X.Y. Carbonation curing behavior and performance improvement of recycled coral waste concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 90, 109473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Roijen, E.; Sethares, K.; Kendall, A.; Miller, S.A. The climate benefits from cement carbonation are being overestimated. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesina, A. Influence of various additives on the early age compressive strength of sodium carbonate activated slag composites: An overview. J. Mech. Behav. Mater. 2020, 29, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, I.; Kohail, M.; El-Feky, M.S.; Rashad, A.; Khalaf, M.A. A review on alkali-activated slag concrete. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2021, 12, 1475–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awoyera, P.; Adesina, A. A critical review on application of alkali activated slag as a sustainable composite binder. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2019, 11, e00268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.C.; Melaku, N.S.; Park, S. Thermodynamic Modeling Study of Carbonation of Portland Cement. Materials 2022, 15, 5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Greve-Dierfeld, S.; Lothenbach, B.; Vollpracht, A.; Wu, B.; Huet, B.; Andrade, C.; Medina, C.; Thiel, C.; Gruyaert, E.; Vanoutrive, H.; et al. Understanding the carbonation of concrete with supplementary cementitious materials: A critical review by RILEM TC 281-CCC. Mater. Struct. 2020, 53, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Z.; Van den Heede, P.; Wang, L.; De Belie, N.; Yao, Y. Numerical modeling of the carbonation depth of meso-scale concrete under sustained loads considering stress state and damage. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 340, 127798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamaa, G.; Duarte, A.P.C.; Silva, R.V.; de Brito, J. Carbonation of Alkali-Activated Materials: A Review. Materials 2023, 16, 3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Li, Z.; Peng, S.; Liu, J.; Wu, Q.; Xu, X. State-of-the-art review of geopolymer concrete carbonation: From impact analysis to model establishment. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, E03124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, A.M. A synopsis of carbonation of alkali-activated materials. Green Mater. 2019, 7, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.Y.; Wei, H.; Zuo, X.B.; Cui, D. Effect of Carbonation on Microstructure Evolution of Alkali-Activated Slag Pastes. Key Eng. Mater. 2022, 929, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, P.; Patapy, C.; Samson, G.; Cussigh, F.; Frouin, L.; Cyr, M. Effect of natural and accelerated carbonation on microstructure and pH of sodium carbonate alkali-activated slag. Cem. Concr. Res. 2024, 181, 107525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; Feng, H.; Jin, N.; Jin, X.; Wu, H.; Shao, Y.; Yan, D.; et al. Comparison of detection methods for carbonation depth of concrete. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bui, H.; Delattre, F.; Levacher, D. Experimental Methods to Evaluate the Carbonation Degree in Concrete—State of the Art Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RILEM. CPC-18 Measurement of hardened concrete carbonation depth. Mater. Struct. 1988, 21, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.; Boutouil, M.; Levacher, D.; Sebaibi, N. Evaluation of the influence of accelerated carbonation on the microstructure and mechanical characteristics of coconut fibre-reinforced cementitious matrix. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 39, 102269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Ye, G. Lattice Boltzmann simulation of the dissolution of slag in alkaline solution using real-shape particles. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 140, 106313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, X.; Yu, M.; Ye, J.; Feng, G. Numerical modeling of supercritical carbonation process in cement-based materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 72, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, R.; Pan, G.; Shen, Q. Carbonation modelling for cement-based materials considering influences of aggregate and interfacial transition zone. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 229, 116925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X.; Hu, X.; He, P.; Liu, J.; Shi, C. A review on the modelling of carbonation of hardened and fresh cement-based materials. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 125, 104315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiery, M.; Dangla, P.; Belin, P.; Habert, G.; Roussel, N. Carbonation kinetics of a bed of recycled concrete aggregates: A laboratory study on model materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2013, 46, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maekawa, K.; Ishida, T.; Kishi, T. Multi-Scale Modeling of Structural Concrete; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Gao, X.; Qin, L. Mathematical modeling of accelerated carbonation curing of Portland cement paste at early age. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 120, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saetta, A.V.; Vitaliani, R.V. Experimental investigation and numerical modeling of carbonation process in reinforced concrete structures: Part I: Theoretical formulation. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londhe, S.N.; Kulkarni, P.S.; Dixit, P.R.; Silva, A.; Neves, R.; De Brito, J. Predicting carbonation coefficient using Artificial neural networks and genetic programming. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 39, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Phung, Q.T.; Yu, Z.; Frederickx, L.; Jacques, D.; Sakellariou, D.; Dauzeres, A.; Elsen, J.; Pontikes, Y. Alteration in molecular structure of alkali activated slag with various water to binder ratios under accelerated carbonation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Ye, G.; Wei, J.; Yu, Q. Extension of the Hymostruc3D model for simulation of hydration and microstructure development of blended cements. Heron 2019, 64, 125–148. [Google Scholar]

- Haha, M.B.; Le Saout, G.; Winnefeld, F.; Lothenbach, B. Influence of activator type on hydration kinetics, hydrate assemblage and microstructural development of alkali activated blast-furnace slags. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haha, M.B.; Lothenbach, B.; Le Saout, G.; Winnefeld, F. Influence of slag chemistry on the hydration of alkali-activated blast-furnace slag—Part I: Effect of MgO. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Phung, Q.T.; Frederickx, L.; Jacques, D.; Dauzeres, A.; Elsen, J.; Pontikes, Y. Microstructural evolution and its impact on the mechanical strength of typical alkali-activated slag subjected to accelerated carbonation. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 19, 100519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.