Abstract

To promote the resource utilization of high-titanium blast furnace slag (HTBFS) and advance the development of lightweight prefabricated structures, this study developed a lightweight HTBFS concrete composite beam (HTC composite beam) by replacing natural gravel and sand in concrete with HTBFS coarse and fine aggregates, and incorporating fly ash ceramsite to reduce self-weight. Symmetrically two-point bending tests were conducted on five HTC composite beams with different reinforcement ratios and precast heights, one Integrally cast HTC beam, and one ordinary concrete composite beam. The failure modes, load-carrying capacities, and deformation characteristics were evaluated. The loading process was also simulated using Abaqus, and the numerical results were compared with experimental data for validation. The results indicate that HTC composite beams satisfy the plane-section assumption; increasing the reinforcement ratio improves the load-carrying capacity, and the precast height has positive effect of HTC composite beams’ load-carrying. Compared with the ordinary concrete composite beam, the HTC composite beam exhibited a 12.30% higher load-carrying capacity, smaller deflection, and better deformation capacity. Multiple energy-based indices demonstrated that HTC composite beams possess favorable post-cracking plastic deformation capacity and stiffness retention. The difference between the finite element simulations and experimental results was less than 5%, confirming both the reliability of the numerical model and the accuracy of the experimental data. An economic analysis revealed that this structural system has significant potential for carbon reduction and cost savings, with an overall saving of approximately 141,000–500,000 CNY. These findings provide theoretical and engineering support for the application of HTC composite beams in prefabricated construction and have positive implications for reducing project costs and promoting the industrialization and low-carbon development of prefabricated buildings.

1. Introduction

Industrialization, low-carbon and zero-carbon strategies, and intelligent construction have become global consensus on sustainable development and represent the future trajectory of the construction industry [1,2,3]. Meanwhile, challenges such as declining global labor availability [4,5] and increasing environmental pressures [6] have exposed the inefficiency [7] and severe pollution [8] associated with traditional construction methods. Consequently, the development of new building materials and innovative construction approaches has become an urgent priority for the industry [9].

In recent years, the use of industrial solid waste as an alternative aggregate in concrete has gained widespread application in the production of prefabricated building components [10,11]. Such materials can significantly reduce costs [12], shorten construction periods [13], lower dependence on labor [14], improve construction efficiency [15], and alleviate environmental burdens [16]. Against this backdrop, this study proposes the utilization of high-titanium blast furnace slag (HTBFS) as concrete aggregate for prefabricated components, aiming to promote the green transformation of the construction sector, with both theoretical significance and engineering value.

HTBFS is a dense slag derived from the smelting of vanadium-titanium magnetite, formed via blast furnace melting followed by natural cooling or water granulation, and is classified as a non-hazardous industrial solid waste [17]. Compared to conventional blast furnace slag, HTBFS exhibits markedly different chemical compositions and mineralogical structures, with titanium dioxide (TiO2) contents reaching 20–24% [18]. It possesses stable mineral structure and favorable physical-mechanical properties that meet the technical requirements of Pebbles and Crushed Stone for Construction (GB/T 14685-2022), enabling its use as both coarse and fine aggregates in concrete production [19]. Data indicate that concrete made with HTBFS aggregates can reduce concrete costs by approximately 20% compared to conventional natural-aggregate concrete [20]. Unlike typical recycled-aggregate concretes, HTBFS concrete requires no additional crushing or screening pretreatment [21], simplifying production, lowering energy consumption, and enhancing environmental performance.

In China, the annual production of HTBFS is about 5 million tonnes [22], with cumulative stockpiles exceeding 100 million tonnes [18], yet the recycling rate remains below 3% [23]. Large-scale accumulation not only occupies land resources but also poses safety hazards [24], and improper disposal may lead to environmental pollution and waste of titanium resources (Figure 1). Therefore, promoting the use of HTBFS concrete can efficiently recycle industrial solid waste, mitigate the environmental risks of slag stockpiling, and leverage its low-cost, low-energy, and simple-process advantages, providing a pathway with significant economic and ecological benefits for titanium resource reuse.

Figure 1.

Piled-up HTBFS (photograph by authors).

Historically, many countries have adopted slag as coarse and fine aggregate for concrete in response to resource shortages and environmental pressures. In 1930, the ACI Committee in the United States released a report evaluating the feasibility of slag aggregates in concrete, citing extensive experimental and field data [25]. In the 1950s–1960s, Japan established its JIS standards to promote industrial-scale application of slag aggregates [26]. As a special variant of blast furnace slag, HTBFS has attracted research attention for its distinctive physical-mechanical performance. As early as 1983, Cai et al. [27] introduced HTBFS into aggregate studies. He et al. [28] later demonstrated in 2006 that HTBFS concrete performs comparably to conventional concrete. Sun [29] showed through experiments that C10–C40 HTBFS concretes exhibit higher 28-day cube compressive, axial compressive, and splitting strengths than ordinary concrete; for C15–C55, the 28-day and 60-day cube compressive exceeded those of ordinary and slag concretes. Further studies have extended its application to high-performance concrete, concrete-filled steel tubes, self-compacting concrete, and pumpable concrete [30]. Over the past decade, the research focus has shifted from raw material properties to the use of HTBFS concrete in structural components. Since 2010, our team has carried out continuous research on prefabricated HTBFS reinforced concrete (HTC) members, including beams, columns, slabs, and walls [19,31,32,33,34]. Among them, HTC beams have shown superior cracking and ultimate moments, reduced crack widths, and improved stiffness and ductility compared to conventional RC beams [19]. Ji’an et al. [35] also reported in 2016 that increasing reinforcement ratios significantly enhances the ultimate capacity of HTC beams.

Prefabricated reinforced concrete (PC) structures are widely used due to their construction efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and quality control advantages [36]. Compared with cast-in-place methods, prefabrication—combining factory production with on-site rapid assembly—can greatly shorten project timelines, reduce labor intensity, and enhance standardization [37]. Composite beams, as critical load-bearing components in prefabricated buildings, are designed with a “prefabrication + cast-in-place” approach: the prefabricated part is produced in the factory with embedded longitudinal steel bar extending beyond the beam ends, forming standardized units; during installation, these are precisely positioned on site and integrated with cast-in-place concrete to form a monolithic load-bearing structure [38,39]. This design retains the rapid assembly advantages of prefabrication while ensuring structural integrity, allowing prefabricated units to carry formwork loads during construction and simplifying site operations [40]. This technology system provides a solution that combines efficiency and reliability for modern buildings through the coordination of industrialized production and modular construction.

In the field of composite beam research, scholars have explored new materials and processes. For example, Xiao et al. [41] found that using 100% recycled aggregate concrete for the prefabricated part of composite beams yields flexural performance comparable to that of ordinary cast-in-place beams. Cheng [42] confirmed the applicability of the plane-section assumption to prestressed recycled aggregate composite beams, with good bond between recycled and ordinary concrete. Shang et al. [43] reported that in composite beams made with sintered brick recycled aggregate, replacement ratio had little correlation with stiffness, ductility, or ultimate capacity, though higher ratios increased crack width growth. Zhong et al. [44] tested eight shale-ceramsite lightweight aggregate concrete composite beams reinforced with HRB500 longitudinal bars, finding that their failure modes closely resembled those of monolithic cast beams. Based on the test results, a revised formula for short-term maximum crack width calculation was developed. Li [45] investigated prestressed ceramsite concrete–ordinary concrete composite beams under static and fatigue loading, observing negative correlations between ultimate flexural capacity and fatigue cycles, and deflection, steel bar strain, maximum crack width and fatigue cycles are all positively correlated. Sun [46] tested HRB500 steel bar lightweight-aggregate composite beams and confirmed their similar failure modes and flexural performance to monolithic beams, with the plane-section assumption remaining valid.

Given HTBFS’s favorable water absorption and mechanical properties [17], coupled with existing composite beam technology enables effective control of the interfacial behavior between dissimilar materials [47], the development of HTBFS aggregate prefabricated composite beams is expected to preserve the mechanical advantages of traditional prefabricated structures while enabling the large-scale recycling of industrial waste, offering substantial economic and societal benefits.

In this study, high-titanium blast furnace slag (HTBFS) produced from the smelting of vanadium–titanium magnetite by Panzhihua Iron & Steel (Group) Co., Ltd. (Panzhihua, China) was used to replace natural gravel and sand as the coarse and fine aggregates in concrete, and ceramsite was added to develop a novel lightweight concrete composite beam based on this new material for application in prefabricated construction.

This approach constitutes an important means to realize the resource utilization of HTBFS, advance prefabricated construction, and promote the construction industry’s transition toward zero carbon. Specifically, seven C40-grade beams were fabricated, including one monolithic HTBFS concrete (HTC) beam with ceramsite, five HTC composite beams with ceramsite, and one ordinary Portland concrete (OPC) composite beam with ceramsite. The research objectives were:

- (1)

- to investigate the effects of reinforcement ratio and precast height on the flexural behavior and failure modes of HTC composite beams under identical concrete strength, section dimensions, and loading conditions;

- (2)

- to verify the applicability of the Code for Design of Concrete Structures (GB 50010-2010, 2024 edition) [48] formulas for cracking moment, ultimate capacity, maximum crack width, and deflection to HTC composite beams;

- (3)

- to analyze the consistency and applicability of experimental results and finite element simulations.

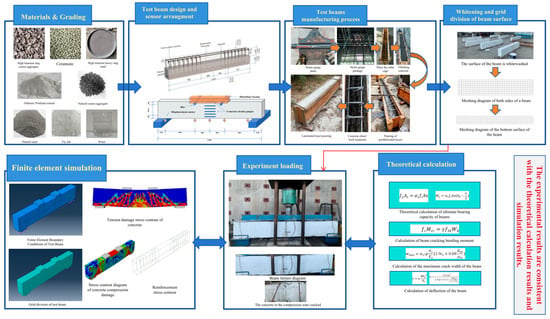

This study provides a theoretical basis and technical support for the engineering application of HTC composite beams in prefabricated structures. The research methodology is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Research Technical Roadmap.

Innovation points: (1) full replacement of concrete natural aggregates with HTBFS to produce prefabricated composite beams, realizing low-carbon, green, economical, and environmentally friendly construction; (2) incorporation of ceramsite to reduce composite beams self-weight, better aligning with the seismic design principle of “strong column–weak beam, strong shear–weak bending”.

Contribution: This study develops a novel lightweight HTC composite beam that meets the requirements of the Code for Design of Concrete Structures (GB 50010-2010, 2024 edition). The proposed beam demonstrates excellent flexural performance, strong energy dissipation capacity, and favorable post-cracking deformation ability, with good interfacial synergy as well as outstanding environmental friendliness and economic viability. The findings provide a reliable theoretical foundation and experimental support for the promotion and application of prefabricated HTC composite beams, and open a new engineering pathway for the large-scale utilization of industrial solid wastes such as HTBFS.

2. Material Properties and Bending Test of HTBFS Reinforced Concrete Composite Beams

2.1. Experimental Materials

The tap water used in the experiments was sourced from the water supply system of the Eastern District, Panzhihua City, China. The cement was ordinary Portland cement (PO 42.5) produced by Dachunshu Cement Co., Ltd. (Yimen County, Yuxi City, China)., Yimen County, China. The coarse aggregate consisted of HTBFS crushed stone produced by Panzhihua Huanye Co., Ltd. (Panzhihua City, China), with a particle size range of 2–26 mm, an apparent density of 2840 kg/m3, and a bulk density of 1350 kg/m3. Fly ash ceramsite aggregate (FAC), supplied by Kunming Huanheng Fly Ash Co., Ltd. (Kunming City, China)., was used to partially replace HTBFS as the coarse aggregate. The fine aggregate was HTBFS sand from produced by Panzhihua Huanye Co., Ltd., with a fineness modulus Mx = 2.9, an apparent density of 3.14 g/cm3, and a bulk density of 1680 kg/m3. The mineral admixtures included Grade II fly ash (supplied by Gongyi Hengnuo Filter Material Co., Ltd., Guangyi City, China) and Grade I Silica fume (SF, model SLT92U), provided by Langtian Resource Comprehensive Utilization Co., Ltd. (Wenchuan County, Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture, China). The water-reducing admixture (WRA) was a polycarboxylate-based high-performance water reducer (model Q8081), produced by Qinfen Building Materials Co., Ltd. (Weinan City, China).

The longitudinal steel bar and erection bar were hot-rolled ribbed steel bars of grade HRB400, with the erection bar of diameter C10, and longitudinal bars of diameters C16, C18, and C20. The stirrups were hot-rolled plain round steel bars of grade HPB300, configured as double-leg stirrups. The tensile test results of the longitudinal steel bar are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data on the tensile testing of longitudinal steel reinforcement bars.

From Table 1, it can be concluded that the steel bars used in the experiment exhibit good mechanical properties and meet the requirements for structural design.

2.2. Specimen Preparation

2.2.1. Concrete Mix Design

The concrete used for the specimens consisted of C40-grade HTBFS concrete with FAC and C40 ordinary commercial concrete with FAC. The mix proportions are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mix proportion of C40 concrete mixed with FAC (unit: kg/m3).

This mix proportion ensures that the concrete possesses good mechanical properties and durability, while the incorporation of FAC optimizes the aggregate structure and reduces the self-weight of the members.

2.2.2. Beams Design

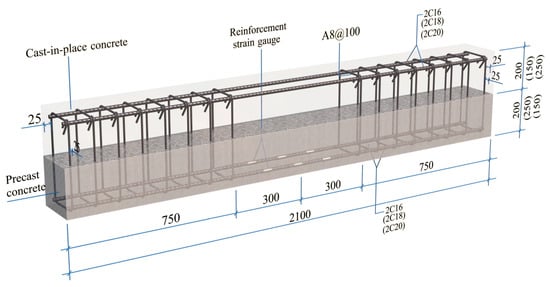

A total of seven test beams were designed, each with a span of 2.1 m and a cross-sectional width of 200 mm. Among them, beams B1–B5 were HTC composite beams with FAC, beam B6 was an HTC monolithic beam with FAC used as a control group, and beam B7 was an OPC composite beam with FAC. The detailed dimensions and steel bar configurations are shown in Table 3. To ensure adequate bond performance between the precast layer and the cast-in-place layer, the interface of the precast layer was roughened to create an uneven surface with a depth of no less than 6 mm. Figure 3 shows the steel bar layout and dimensions of HTC composite beams B1–B3.

Table 3.

Specimen information.

Figure 3.

Reinforcement layout and size of composite beams (unit: mm).

2.2.3. Arrangement of Measurement Points

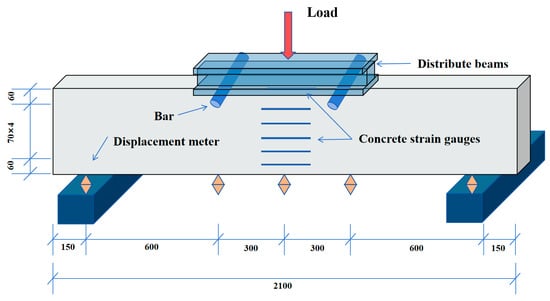

To obtain data on ultimate flexural capacity, crack development, longitudinal tensile reinforcement strain, and deflection, three resistance strain gauges were evenly arranged along the longitudinal bar at the bottom of the beam in the midspan region. The strain values of the longitudinal bars under different loading levels were recorded using a data logger, as shown in Figure 3. Five concrete strain gauges were arranged along the height of the midspan cross section, and one strain gauge was placed on the top surface at midspan to record concrete strain during the test. In addition, to measure beam deflection, linear variable displacement transducers (LVDTS) were installed at the midspan, loading points, and both support ends of the beam, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Arrangement of Measurement Points (mm).

2.2.4. Beams Production

Wooden formwork was used for specimen fabrication. The steel reinforcement cages were tied according to the reinforcement drawings, strain gauges were attached, and the cages were placed into the formwork, with concrete cover thickness controlled by spacers. The formwork was reinforced with steel wires to prevent expansion or deformation during concrete casting. The concrete was poured in two stages: after the first pour, specimens were cured for 14 days, and the surface of the precast layer was roughened to enhance interface bonding before the second pour. The stirrup configuration and interface treatment followed the Technical Standard for Prefabricated Concrete Buildings [49] and the Technical Specification for Prefabricated Concrete Structures [50].

For each pour, three HTC cubes, three OPC cubes, and three temperature-compensation cubes were prepared for strength and environmental compensation testing. The formwork was removed 24 h after casting, and the specimens were covered with wet felt and watered daily for 28 days of standard curing. To facilitate crack observation, the specimen surfaces were painted white and marked with a 50 mm × 50 mm grid, as shown in Figure 2.

2.3. Loading Scheme

This section describes the loading configuration, loading rate control, and termination criteria adopted to evaluate the flexural performance of HTC composite beams.

To investigate the flexural performance of HTC composite beams, a 500 kN hydraulic jack was used to apply a two-point centrally symmetric concentrated loading scheme. The initial loading rate was set to 10 kN/min until the applied load reached 50 kN, after which the loading rate was reduced to 5 kN/min until the first visible crack appeared. After cracking, the loading rate was increased to 10 kN/min until the specimen reached approximately 90% of its ultimate flexural capacity, and then reduced again to 5 kN/min until failure.

The loading process was terminated when any one of the following ultimate limit states was reached [51]:

- (1)

- the midspan deflection reached 1/50 of the span length;

- (2)

- the crack width at the tensile reinforcement exceeded 1.5 mm;

- (3)

- fracture of the bottom tensile reinforcement occurred or the tensile reinforcement strain reached 0.01;

- (4)

- cracking or crushing of the concrete in the compression zone at the top of the beam.

Figure 5 illustrates the loading configuration and force distribution.

Figure 5.

Loading method and force conditions.

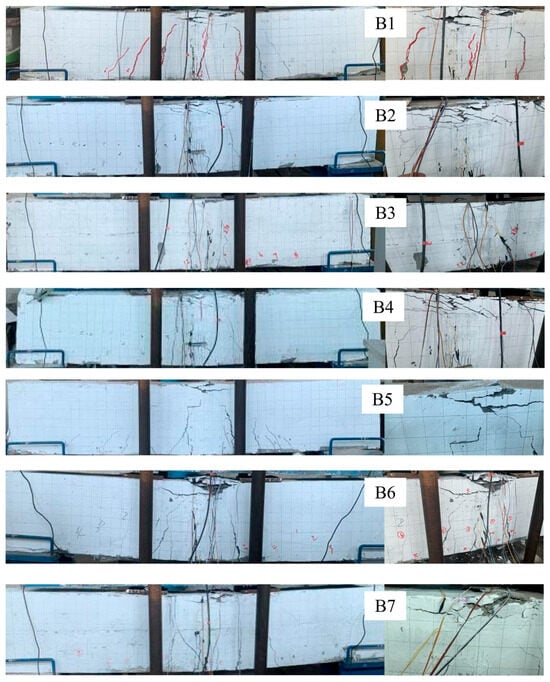

2.4. Experimental Phenomenon

As shown in Figure 6, all specimens underwent four distinct stages during loading: the elastic stage, the cracking stage, the yielding stage, and the ultimate stage. In the initial loading phase, the specimens were in the elastic working stage, exhibiting small deflections and no visible cracks. As the load increased, cracks first appeared in the tensile zone of the pure bending section, accompanied by a sharp rise in tensile reinforcement stress. With further loading, diagonal cracks developed in the bending-shear zones, and existing cracks propagated toward the top compression zone of the pure bending section and toward the two loading points at both ends. At the same time, the deflection and deformation of the specimens increased significantly. As the load continued to rise, the number of cracks increased and their widths widened. The final failure mode was characterized by yielding of the tensile reinforcement and crushing of the concrete in the upper compression zone, leading to the ultimate failure of the specimens. Experimental observations indicated that the failure mode was not affected by the composite height of the beams or the reinforcement ratio of the tensile steel. No slip or delamination occurred along the composite interface in any beam during loading, confirming the effectiveness of the roughening treatment in enhancing interface bonding performance, this phenomenon may be attributed to the formation of a more favorable microstructure at the composite interface within the HTC material system. The details of crack development and the corresponding test data are presented in Table 4.

Figure 6.

Beam B1–B7 Failure diagram of the component and concrete cracking in the compression zone.

Table 4.

Parameters of First Crack Load, Cracking Moment, First crack width Failure Load and Crack Characteristics in Beam Flexural Tests.

From the test phenomena, no interface slip or obvious debonding failure occurred in the HTC composite beam during the loading process, which indicates that it has good interfacial bonding performance and that the chiseling treatment has a significant effect on improving the bonding strength. Combined with the existing materials science theories, this paper holds that this phenomenon may be related to the formation of an optimal microstructure at the composite interface of the HTC material system.

In ordinary concrete, the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) is typically a loosely structured region with high porosity and concentrated Ca(OH)2 precipitation, making it the weakest microstructural area in the material and a common channel for crack initiation and propagation. In contrast, the high-titanium blast furnace slag-based concrete (HTC) used in this study exhibits high mineral reactivity, producing abundant C–S–H gel in the hydration products, which helps fill the pores in the ITZ and improve its density.

Moreover, the roughening treatment significantly increases the interface roughness and the effective contact area, enhancing the mechanical interlock between the interfaces and further improving overall bond performance. Although no direct microstructural testing was conducted in this study, the experimental results suggest that the HTC material system, combined with the interface treatment process, may have jointly facilitated the formation of a denser and more continuous ITZ, thereby achieving excellent interface cooperative performance.

2.5. Test Results and Analysis

2.5.1. Comparison of Load-Bearing Capacity

The results in Table 4 indicate that increasing the longitudinal tensile reinforcement ratio can significantly enhance the load-bearing performance of HTC composite beams. When the reinforcement ratio was increased from 0.54% to 0.68%, the cracking load and cracking moment increased by approximately 5.88%, while the ultimate load and ultimate moment increased by 24.91%. Further increasing the reinforcement ratio to 0.84% resulted in an additional 5.56% increase in cracking load and cracking moment, and a 23.60% increase in ultimate load and ultimate moment. Compared with the monolithically cast HTC beam (B6) of the same material, the HTC composite beam (B2) exhibited identical performance in cracking load and cracking moment but slightly lower ultimate load and ultimate moment, decreasing by about 10.42%. This suggests that the composite beam maintains good overall load-bearing capacity while ensuring structural integrity. In addition, compared with the OPC composite beam (B7), the HTC composite beam (B2) showed similar performance at the cracking stage but exhibited increases of 12.30% in both ultimate load and ultimate moment, confirming the significant advantage of HTC material in enhancing the late-stage load-bearing capacity of composite structures.

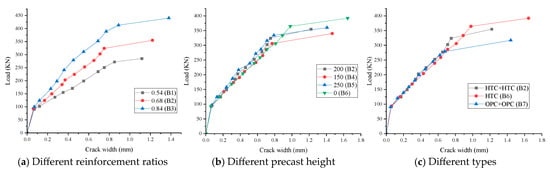

2.5.2. Comparison of Maximum Crack Width

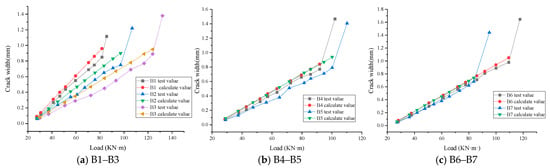

As shown in Figure 7a, for beams B1–B3 under the same load, beams with a higher reinforcement ratio exhibited smaller maximum crack widths, indicating that the restraining effect of the reinforcement can effectively suppress the initiation and propagation of cracks. Figure 7b shows that for beams B2 and B4–B6 under the same load, increasing the precast height can, to some extent, reduce the maximum crack width. Figure 7c demonstrates that for beams B2, B6 and B7 under loads below 330 kN, the HTC composite beams exhibited smaller maximum crack widths than both HTC monolithic beams and OPC composite beams under the same load, indicating that a well-designed HTC composite beam interface can effectively mitigate crack propagation and improve structural durability.

Figure 7.

Load-Maximum Crack Width Diagram.

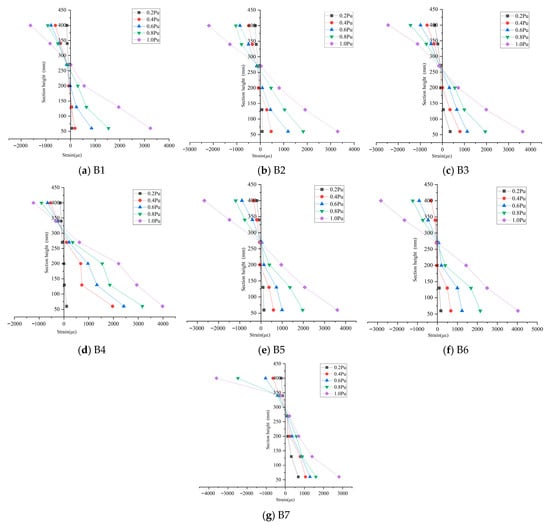

2.5.3. Applicability of the Plane Section Assumption

Based on the measured values from the concrete strain gauges placed at different heights at mid-span of beams B1–B7, strain–section height distribution curves were plotted for each beam under various load levels (see Figure 8a–g).

Figure 8.

Variation Curve of Concrete Strain in Beam Span with Section Height under Different Loads.

The results indicate that from the initial loading stage to the ultimate load, the concrete strain values exhibit an approximately linear relationship with the distance from the corresponding height to the neutral axis, demonstrating that the beam sections consistently satisfy the plane section assumption. Therefore, the plane section design theory specified in the Code for Design of Concrete Structures is applicable to HTC composite beams, HTC monolithic beams, and OPC composite beams alike.

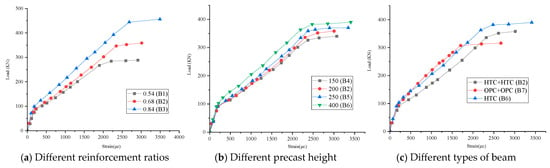

2.5.4. Longitudinal Tensile Reinforcement Strain

The load–strain curves of the longitudinal tensile reinforcement are shown in Figure 9. Overall, the development trends of the load–strain curves for both composite beams and ordinary beams are generally consistent and can be divided into three stages: before cracking, the strain of the tensile reinforcement increases linearly with the load; at the onset of cracking, an inflection point appears in the curve with a reduced slope, and the strain of the tensile reinforcement begins to increase significantly; as the load continues to increase, the tensile reinforcement yields, and after yielding, its strain rises sharply until the member fails.

Figure 9.

Strain diagram of mid span steel bars.

According to Figure 9a, it can be observed that beams with higher reinforcement ratios exhibit smaller reinforcement strain under the same load, indicating greater stiffness and reduced deformation. Figure 9b shows that as the precast height increases, the reinforcement strain of the beams decreases, suggesting that the thickness of the precast layer has a positive effect on stiffness. Figure 9c indicates that after cracking, under the same load conditions, the reinforcement strain of HTC composite beams is slightly higher than that of HTC monolithic beams and OPC composite beams, reflecting the lowest post-cracking stiffness but stronger deformability.

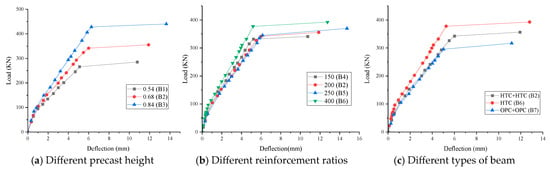

2.5.5. Flexural Deflection Behavior

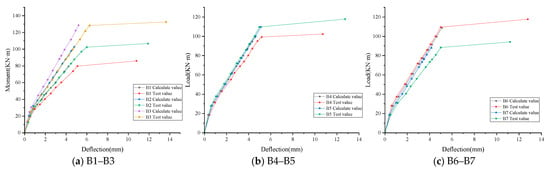

Figure 10 presents the load–midspan deflection curves of the beam specimens. The overall deflection development trends of all beams were similar, exhibiting two critical inflection points: the first inflection point corresponds to the cracking of the concrete, at which the specimens entered an elastoplastic state, the sectional stiffness decreased, and the deflection growth rate accelerated. With the continued increase in load, the load and midspan deflection showed a linear growth relationship. The second inflection point occurred at the yielding of the reinforcement, after which the deflection increased sharply until the specimen failed.

Figure 10.

Load-midspan deflection curve of beams with different parameters.

Figure 10a indicates that, under the same load, beams with a higher reinforcement ratio exhibited greater load-carrying capacity and smaller deflections. Figure 10b shows that changes in the height of the precast layer had little effect on deflection development, with the overall structural stiffness remaining essentially consistent. Figure 10c demonstrates that, under the same load, the HTC composite beam (B2) exhibited larger deflections compared to the HTC monolithic beam (B6), reflecting relatively weaker deformation capacity; however, compared to the OPC composite beam (B7), the HTC composite beam demonstrated better ductility and deformation capacity.

2.5.6. Energy Dissipation Capacity and Stiffness Degradation Analysis of HTC Composite Beams

To comprehensively evaluate the energy dissipation capacity and deformation performance of HTC composite beams during the loading process, three indicators were selected: energy dissipation area (W), energy ratio (), and stiffness degradation coefficient (). These indicators were used to quantitatively assess the energy dissipation capacity, stiffness retention ability, and post-cracking deformation level of the beams.

- (1)

- Energy Dissipation Analysis

To evaluate the energy dissipation capacity, the envelope area under the load–deflection curve (–) was calculated as an indicator of energy absorption, expressed as:

The energy dissipation area can be approximately calculated using the trapezoidal integration method, expressed as:

where and denote the load and corresponding deflection at the i-th measurement point, respectively.

- (2)

- Energy Ratio Analysis

To further evaluate the nonlinear energy dissipation capacity of the specimens, the energy ratio (η) was introduced, defined as:

where is the total energy dissipation area, and is the theoretical energy input during the elastic stage. When η > 1, it indicates that the specimen possesses significant plastic energy dissipation capacity. A larger η value implies that the specimen can continue to absorb energy after yielding, thereby delaying the failure process. In addition, the equivalent damping ratio () can be estimated using the equivalent energy method as a quantitative reflection of seismic performance:

A larger value indicates stronger energy dissipation capacity of the specimen and better seismic performance.

- (3)

- Stiffness Degradation Analysis

After yielding, the stiffness of structural members generally undergoes degradation. To evaluate their stiffness retention capacity, the stiffness degradation coefficient was introduced, which is defined as:

where represents the post-yield stiffness (average stiffness in the plastic stage), and denotes the initial stiffness.

A higher stiffness degradation index indicates that the specimen retains stronger stiffness capacity in the post-cracking stage, exhibiting superior deformation resistance and energy absorption potential.

Based on the key points obtained from the load–deflection and reinforcement strain curves during the tests, the calculated results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Ductility Coefficient and Energy Dissipation of Each Specimen.

Table 5 presents the comparison results of ductility coefficients, energy dissipation indices, and stiffness degradation coefficients for all specimens. Overall, HTC composite beams exhibited excellent energy dissipation capacity, post-cracking deformation performance, and stiffness retention ability under loading. In most indices, they outperformed the conventional OPC composite beam (B7), and in some cases even surpassed the monolithic HTC beam (B6), thereby verifying the potential of HTC materials in enhancing the seismic performance of precast members.

From the perspective of the energy dissipation index (W), beam B3 (high-reinforcement HTC) achieved an energy dissipation area of 4689.6 kN·mm, the highest among all specimens, which was significantly superior to that of the monolithic beam B6 (4020.1 kN·mm) and the conventional composite beam B7 (2725.1 kN·mm). This result highlights the superior energy absorption capability of HTC materials when combined with high reinforcement ratios. Beam B5 (with a higher precast section) also exhibited favorable energy dissipation, indicating that both reinforcement ratio and precast height are key factors influencing the energy dissipation performance of HTC composite beams.

Regarding the energy ratio (η), the monolithic beam B6 performed slightly better (4.11). However, several HTC beams—such as B5 (4.03), B3 (3.50), and B1 (3.48)—were close to or above 3.5, demonstrating excellent nonlinear energy dissipation potential. Although some HTC beams showed slightly lower η values, such as the composite beam B2 (3.17), its energy dissipation area reached 3246.1 kN·mm, which was still markedly superior to that of the conventional composite beam. This suggests that its overall energy absorption level remains advantageous. Such phenomena may be related to connection detailing, stress concentration, and reinforcement distribution, and could potentially be improved through further optimization of construction details to enhance energy ratio performance.

The stiffness degradation results were relatively complex. On average, the HTC beam group exhibited better stiffness degradation coefficients compared with B6, indicating a certain degree of post-cracking stiffness retention. For example, the values of B1 and B2 were 0.06 and 0.04, respectively, both higher than that of the monolithic beam B6 (0.03), suggesting that some HTC members retained higher stiffness after cracking. However, B3 experienced more significant stiffness degradation (0.02), implying that although high reinforcement improves energy dissipation, it may also accelerate crack development and stiffness reduction, thereby necessitating optimization of construction techniques.

In summary, HTC composite beams demonstrated favorable performance in terms of energy dissipation capacity, ductility, and post-cracking stiffness retention, with several indices’ superior to both conventional monolithic and composite beams. These findings confirm the potential of this novel high-performance material in precast concrete structures. Particularly, with rational design of reinforcement ratio and precast-to-cast-in-place proportion, HTC composite beams can achieve performance-oriented optimization, showing promising prospects for engineering applications.

3. Theoretical Calculation and Comparison with Experimental Results

3.1. Comparative Analysis of Theoretical and Experimental Values of Ultimate Flexural Bearing Capacity

All beams tested in this study are singly reinforced rectangular-section flexural members. According to GB50010-2010 Code for Design of Concrete Structures, the ultimate flexural capacity of a singly reinforced rectangular section can be calculated using Equations (1) and (2):

where is the depth of the compression zone of the flexural member’s normal section; is coefficient of the rectangular stress block for the compressed concrete, taken as 1.0; is the design value of the axial compressive strength of concrete, defined as ; is the standard value of concrete compressive strength; is the width of the beam section; is the design value of tensile strength of steel bar; is the cross-section area of tensile steel bar; is the calculated flexural bearing capacity of the member’s normal section, and is the effective depth of the section.

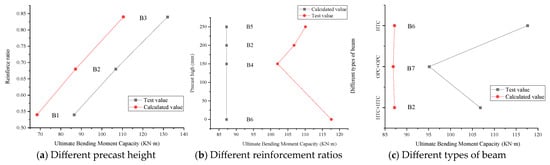

By substituting the parameters of each specimen into the above equations, the theoretical ultimate flexural capacities of beams B1–B7 were obtained. The comparison between the experimental values and theoretical calculations is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Comparison of experimental and calculated ultimate flexural capacity of beams with different parameters.

The results indicate that the experimental capacities of all specimens were greater than their theoretical values. The average ratio of experimental ultimate capacity ( to calculated capacity () was 1.22 (with a standard deviation of 0.07 and a coefficient of variation of 0.06). This demonstrates that the experimental flexural capacities of HTC composite beams, OPC composite beams, and HTC monolithic beams were all greater than the theoretical value, with an approximate safety factor of 1.2, indicating a certain level of safety reserve. Therefore, design in accordance with GB50010-2010 is feasible.

From Figure 11a, it can be concluded that an increase in reinforcement ratio enhances the ultimate flexural capacity of the beams, with the experimental capacities of all three reinforcement levels exceeding their theoretical values. Figure 11b shows that increasing the precast height also improves the ultimate flexural capacity of composite beams. From Figure 11c, it can be observed that the discrepancy between experimental and calculated ultimate loads for HTC monolithic beams was greater than that for composite beams. This may be attributed to the longer curing period of monolithic beams and the higher long-term strength development of HTC concrete containing high-titanium blast furnace slag.

3.2. Comparative Analysis of Theoretical and Experimental Values of the Cracking Moment

According to the Principles of Concrete Structural Design (China) [52], assuming that the strain distribution across the normal beam section remains planar, failure occurs when the ultimate tensile strain at the edge of the tensile zone exceeds . Since no prestressing was applied in this test, the cracking moment of the tensile zone concrete can be calculated using Equation (3):

where is the coefficient accounting for the plasticity influence on the section modulus (for rectangular sections, = 1.55 as specified in the code); is elastic section modulus of the transformed section at the tensile edge (mm3); and is the standard value of concrete tensile strength (for C40 concrete, ).

The value of is determined according to the relevant provisions in Code for Design of Concrete Structures (GB50010-2010) and can be calculated using Equations (4)–(8):

where is the section height (mm). For ≤ 400, is taken as 400 mm, and for ≥ 1600 , h is taken as 1600 mm; is the elastic modulus of reinforcement; is the elastic modulus of concrete, given by ; is the distance from the centroid of the transformed section to the compression edge; is the moment of inertia of the transformed section about its centroidal axis, reflecting the ability of the transformed section to resist bending deformation, and is the Ratio of the elastic modulus of steel bar to that of concrete.

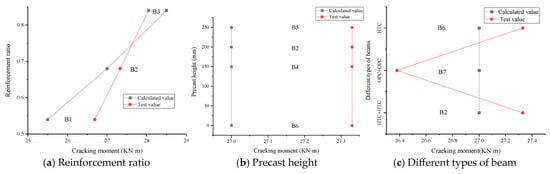

Based on Equations (4)–(8), the theoretical cracking moments of beams B1–B7 were calculated and compared with the experimental results . The results are shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Comparison of calculated and experimental values of cracking moment for beams B1–B7.

The analysis results indicate that the average ratio of / is 0.99, with a standard deviation of 0.02 and a coefficient of variation of 0.02. This demonstrates that the calculation method for the cracking moment of beams specified in the code is well applicable to HTC beams. Specifically, Figure 12a shows that increasing the reinforcement ratio significantly enhances the cracking moment; Figure 12b suggests that variations in precast height have only a minor effect on the cracking moment; and Figure 12c reveals that the discrepancy between calculated and experimental ultimate moments is greater for monolithic beams than for composite beams, which may be attributed to differences in material curing conditions and interface continuity.

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Theoretical and Experimental Values of the Maximum Crack Width

According to the GB50010-2010 code, the maximum crack width can be calculated by the following formula:

The definitions of the parameters in the formula are given in Equations (10)–(13):

where is the characteristic coefficient of member force; for flexural members, it takes the value of 1.9; is the non-uniformity coefficient of longitudinal tensile reinforcement strain between cracks; if < 0.2 it is taken as 0.2; if > 1.0 it is taken as 1.0. is the longitudinal tensile reinforcement stress calculated under quasi-permanent combination. the distance from the outer edge of the longitudinal reinforcement to the bottom edge; if less than 20, it is taken as 20; if greater than 65, it is taken as 65. is the Reinforcement ratio of longitudinal tensile steel bars calculated based on the effective tensile concrete cross—sectional area; if less than 0.01, it is taken as 0.01. is the effective tensile concrete sectional area; in this test, = 0.5bh. is the equivalent diameter of longitudinal tensile reinforcement. is the nominal diameter of the i-th type of longitudinal tensile reinforcement. the number of bars of the i-th type of reinforcement. refers to the relative bond characteristic coefficient of the i-th type of longitudinal tensile steel bar. For ribbed steel bars, its value is taken as 1.0.

By substituting the parameters of each beam into the equations, the theoretical values were calculated and compared with the experimental values (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Comparison between the calculated values and the test values of the short-term maximum crack width.

The results indicate that for the HTC monolithic beam B6, the difference between the experimental and calculated crack widths is within 10%, showing good agreement. In contrast, for the other composite beams, the discrepancy between the experimental and calculated values is relatively large, and the error increases with greater precast height, reaching more than 20% in some cases. This suggests that the current code does not sufficiently account for the composite interface. The possible reasons may include the interface treatment method, material heterogeneity, and the discontinuous development of cracks along the interface, all of which affect the calculation accuracy. Therefore, it is recommended that future studies introduce a modified model that incorporates a “composite interface influence coefficient” to improve the accuracy of crack width calculations.

3.4. Comparative Analysis of Theoretical and Experimental Values of Deflection

The theoretical application range for calculating the deflection of a beam is from the cracking of the beam member until the longitudinal reinforcement yields. According to GB 50010-2010 Code for Design of Concrete Structures and Mechanics of Materials, the formula for calculating the deflection of flexural members is as follows:

where is the deflection of the member; is a coefficient related to load type and boundary conditions (taken as 23/216 for two-point concentrated loading); is the bending moment value calculated according to the quasi-permanent combination of loads; is the calculated span of the member; is the short-term stiffness of the flexural member; is the non-uniform coefficient of reinforcement strain; is the reinforcement ratio of longitudinal tensile bars, taken as for reinforced concrete flexural members; and the ratio of the tensile flange sectional area to the effective web sectional area, which equals 0 or rectangular sections.

Based on Equations (14) and (15), the theoretical deflection values of beams B1–B7 were calculated and compared with the experimental results, as shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Comparison between theoretical value and test value of short-term deflections.

As seen in Figure 14, the mid-span deflection of the monolithic beam B6 shows a high degree of agreement between the experimental and calculated values, confirming the applicability of the formula. However, for the other composite beams, significant deviations are observed between the experimental and theoretical mid-span deflections, indicating that the current code formula does not fully account for factors such as “slip at the composite interface” and “structural detailing effects on deflection”. Therefore, future studies should focus on modifying the deflection calculation formula to address the particular characteristics of composite beams.

4. Finite Element Analysis of Lightweight Aggregate HTC Composite Beams

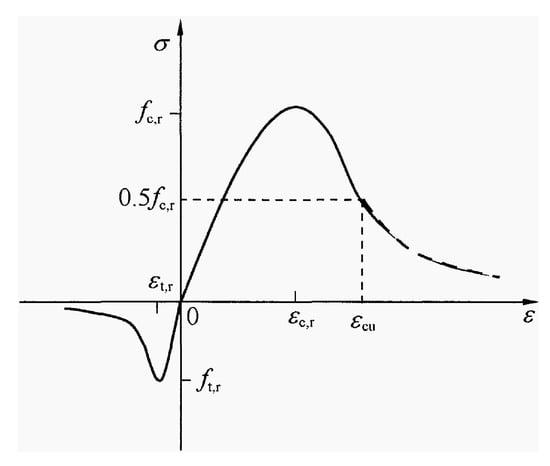

4.1. Selection of Constitutive Models for Concrete and Reinforcement

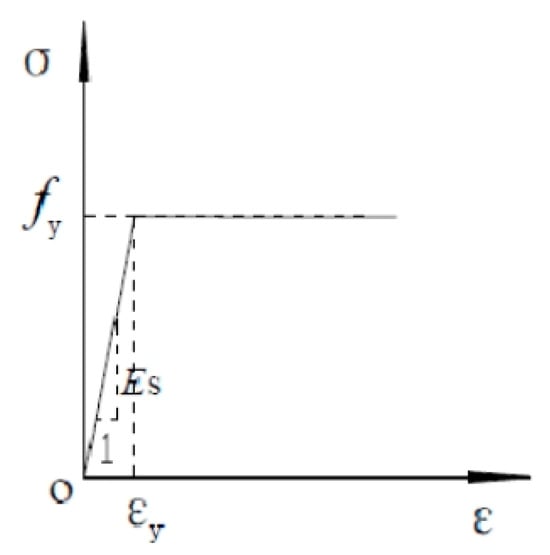

The ABAQUS (2022 FD04 FP.2232) finite element software provides three main constitutive models for concrete, namely the brittle cracking model, the smeared cracking model, and the concrete damage plasticity (CDP) model. In this study, the CDP model was adopted to simulate the nonlinear mechanical behavior of concrete, including plastic deformation and stiffness degradation under both compression and tension. The uniaxial compressive and tensile stress–strain relationships of concrete were defined based on the damage-based constitutive model recommended in the Code for Design of Concrete Structures (GB 50010-2010) [48] (Details can be found in Appendix B). The corresponding elastic properties, strength parameters, and plasticity-related parameters required by the CDP model—such as the elastic modulus, Poisson’s ratio, dilation angle, flow potential eccentricity, biaxial-to-uniaxial compressive strength ratio, yield surface shape parameter, and viscosity parameter—are summarized in Table 6. The yield stress, inelastic strain, cracking strain, and damage parameter were derived from the uniaxial stress–strain curves and implemented in ABAQUS in tabular form. (Details can be found in Appendix B) For the reinforcement, an ideal elastic–plastic constitutive model was employed in the finite element simulation, which has been widely used in reinforced concrete analysis. The elastic moduli of the longitudinal reinforcement corresponding to specimens B1, B2, and B3 were determined from tensile tests and are also listed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Material parameters used in the finite element model (ABAQUS CDP model).

4.2. Establishment of the Finite Element Model

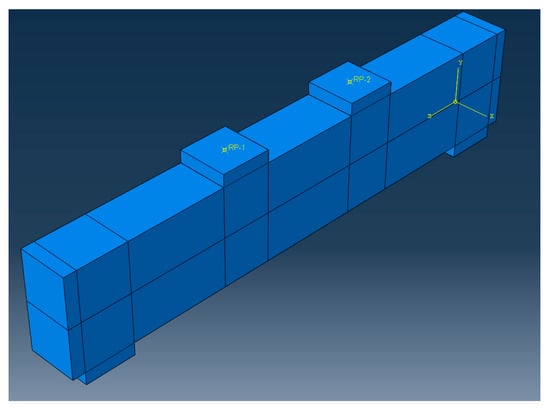

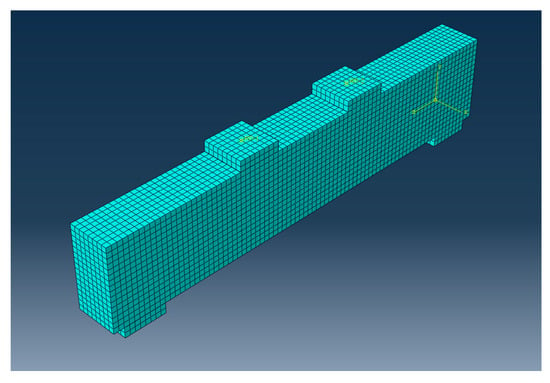

To verify the reliability of the experimental results, a finite element model of composite beams was developed in Abaqus, with parameters consistent with the actual experiments. The specimens have a length of 2.1 m and a cross-section of 200 mm × 400 mm. The bottom longitudinal reinforcement consists of 2C18 bars, the top erection bars consist of 2C10 bars, and the stirrups are C8@100. A pure bending segment is set at mid-span. The finite element model adopts a two-dimensional plane simulation: The concrete and bearing pads were modeled using eight-node linear brick elements with reduced integration (C3D8R), which are well suited for solid concrete simulation in Abaqus as they effectively capture three-dimensional stress–strain states while mitigating volumetric locking. The longitudinal reinforcing bars were modeled using two-node truss elements (T3D2), since truss elements are appropriate for representing the axial behavior of reinforcement. It is assumed that no slip occurs between the reinforcement and the concrete; thus, the reinforcement cage is embedded into the concrete beam solid elements. The steel pads are tied (Tie constraint) to the concrete beams. To simulate the actual working conditions at the composite interface, the precast layer is defined as the slave surface and the cast-in-place layer as the master surface, with a surface-to-surface contact approach applied to model the interface transfer of forces [55,56]. The mesh size is 25 mm for concrete and pads, and 10 mm for reinforcement. The boundary conditions at supports and loading are shown in Figure 15, and the grid division is shown in Figure 16.

Figure 15.

Finite Element Boundary Conditions of Test Beam.

Figure 16.

Grid division of test beam.

4.3. Analysis of Finite Element Results and Comparison with Tests

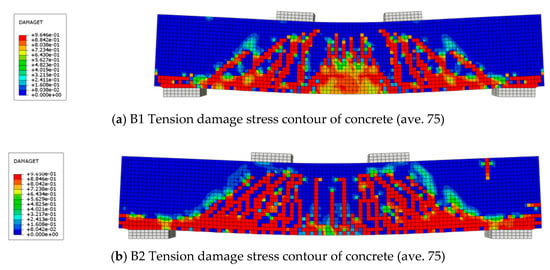

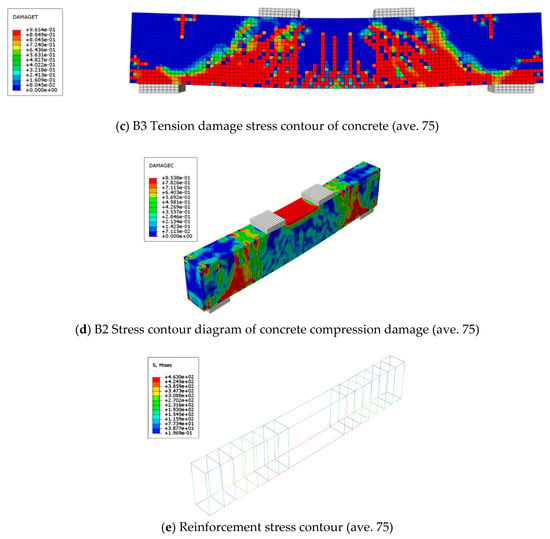

4.3.1. Failure Modes

To investigate the stress–strain development and failure characteristics of HTC composite beams, beams with different reinforcement ratios (B1–B3) are selected as representative specimens for numerical analysis. Figure 17 presents the finite element simulation results of the beams at the ultimate state, including the compressive and tensile damage cloud diagrams and reinforcement stress distribution of beam B2, together with the tensile damage cloud diagrams of beams B1 and B3. As shown in Figure 17, the simulated failure modes of the beams are generally consistent with the experimental observations. Severe damage is concentrated in the concrete compression zone at the top of the beam, while cracks initiate in the bottom pure bending region and gradually propagate upward toward the support regions. The maximum stress in the longitudinal reinforcement consistently occurs at the mid-span section. It is observed that the overall stress–strain evolution and failure patterns of the beams obtained from the Abaqus simulations exhibit similar trends. In all cases, failure is governed by crushing of the concrete in the upper compression zone, and the influence of different precast heights on the damage development is relatively limited. Therefore, beam B2 is selected as a typical specimen for detailed discussion of stress distribution and damage evolution.

Figure 17.

Finite element damage and stress contours for concrete and reinforcement (cloud maps).

Although the overall trends are similar, the influence of reinforcement ratio on the numerical response can still be clearly identified. With increasing reinforcement ratio, the tensile stress in the longitudinal reinforcement develops more gradually after cracking, indicating enhanced crack control and improved stress redistribution capacity. Meanwhile, the tensile damage in the bottom concrete zone is slightly reduced, and the compression damage in the upper concrete develops in a more uniform manner, reflecting increased flexural stiffness and ultimate load-carrying capacity. Overall, the finite element model established in Abaqus can effectively capture the stress distribution characteristics and failure mechanisms of lightweight aggregate HTC composite beams, demonstrating satisfactory accuracy and reliability.

4.3.2. Comparison of Bearing Capacity

Table 7 presents the comparison of cracking load and ultimate load between experimental measurements and Abaqus finite element simulations for HTC composite beams (B1–B7). It can be seen that the finite element simulation results of Abaqus are slightly higher than the actual test values. This is because during the test, there may be errors in the binding of steel bars, the concrete may not be completely uniformly mixed during pouring and stirring, and unexpected issues may occur during the concrete curing process, which leads to the finite element simulation results being higher than the test values. Com-paring beams with different parameters reveals that, under otherwise identical conditions, the cracking and ultimate loads of simulated monolithic beams are higher than those of simulated composite beams, consistent with the experimental trends. Furthermore, the height of the precast layer has little influence on the cracking and ultimate loads of simulated beams.

Table 7.

Comparison between test value and simulation value of load characteristic value of test beam.

4.3.3. Deflection Comparison Analysis

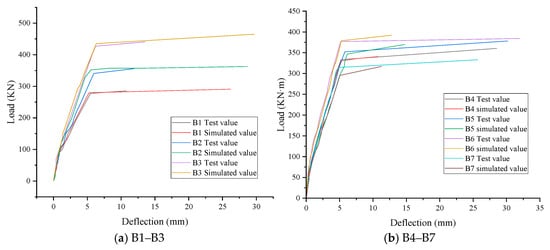

Figure 18 presents the comparison between the experimental and simulated load–deflection curves for each beam.

Figure 18.

Comparison of Load–deflection Curves of Test Beam.

It can be observed that: (1) all beams exhibit consistent deflection trends in the elastic stage, cracking stage, and yielding stage; (2) before yielding, the simulated values show a high degree of agreement with the experimental measurements; (3) the simulation results can be effectively used to predict the deformation performance of HTC composite beams.

5. Economic Analysis

According to the cost information published on Sichuan Province Construction Price Information Network on 12 July 2025 [20] (1 $ = 7.16719 ¥), the price comparison between HTBFS pumped concrete and ordinary pumped commercial concrete is shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Price comparison between HTBFS and ordinary concrete.

Taking a high-rise residential building as an example, with a total construction area of 30,888.18 m2, consisting of 48 stories above ground and 3 underground, and a total construction cost of 76,438,678.96 Yuan, the composite beams were designed with strength grade C30 and required a concrete volume of 2271.806 m3. By replacing the beams with HTBFS concrete, the overall project cost savings mainly derive from three aspects: direct material cost savings, where the unit price difference between HTBFS and ordinary concrete is 72.4 Yuan/m3 and, with an actual usage of 2271.806 m3, the material cost is reduced by approximately 164,478.76 Yuan; carbon emission trading benefits, since HTBFS concrete reduces about 272.62 tons of CO2 emissions compared with ordinary concrete, which at the current carbon trading price of 80 Yuan/ton yields a carbon revenue of about 21,809.60 Yuan; and construction-related organizational costs, where adjustments in construction methods and a slight extension of the construction period are expected to add approximately 40,000 Yuan in management costs and 5000 Yuan in adjustment fees, leading to an overall additional expense of 45,000 Yuan. In summary, after considering all the above factors, the net economic savings amount to approximately 141,288.36 Yuan.

On this basis, further economic potential could be realized through policy incentives and construction management optimization. First, under the green building subsidy policy, 0.5% of the total construction cost can be subsidized, equating to about 380,000 Yuan. Second, if the carbon trading market price rises from the current 80 Yuan/ton to 120 Yuan/ton, the carbon trading revenue would increase from 21,809.60 Yuan to approximately 32,714 Yuan. Furthermore, by optimizing construction organization and scheduling, such as controlling construction delays within 5 days, management expenses can be reduced while improving efficiency and cost control. Overall, with the combined effect of multiple optimization measures, the application of HTBFS concrete can yield enhanced economic benefits in the range of 141,000 to 500,000 Yuan.

6. Conclusions

This study, focusing on the resource utilization of HTBFS and aligned with the development trend of prefabricated concrete structures, designed and verified a lightweight HTC composite beam. Through structural testing and finite element analysis, the research examined structural performance, numerical simulation accuracy, and environmental and economic benefits, leading to the following conclusions:

- (1)

- Structural performance is satisfactory. During the flexural process, the concrete strain along the HTC beam height generally conforms to the plane section assumption [44], and the failure mode agrees with the design expectations. No interfacial slip or delamination occurred, indicating that the surface roughening treatment was effective and the structural integrity was reliable. Under identical reinforcement conditions, the cracking moment of HTC composite beams was comparable to that of HTC monolithic beams, with the ultimate moment being slightly lower by about 10.42%, but still higher than that of OPC composite beams by approximately 12.30%. Increasing reinforcement ratio significantly enhanced the load-bearing capacity of HTC composite beams [35], while greater precast height also had a positive effect. The current design code formulas are applicable for predicting the ultimate flexural capacity of HTC composite beams.

- (2)

- Plastic deformation performance is superior. HTC composite beams demonstrated excellent plastic deformation capacity and stiffness retention under loading, with strong energy dissipation ability. Certain indices of energy dissipation and stiffness outperformed traditional monolithic and ordinary composite beams, reflecting better crack control capacity and enhanced deformation coordination after cracking.

- (3)

- Finite element simulation shows high accuracy. The finite element model of HTC composite beams developed in Abaqus effectively simulated their mechanical behavior. The simulated results agreed well with the experimental outcomes in terms of failure mode, load-bearing capacity, and load–deflection relationships. The average errors of cracking and ultimate loads were both within 5%, confirming the reliability of the numerical model and the accuracy of the experimental data.

- (4)

- Environmental and economic benefits are significant. HTBFS, a harmless by-product of metallurgical processes, is characterized by abundant reserves, low utilization, and a small carbon footprint. Its application in concrete production not only reduces the consumption of natural aggregates but also effectively lowers unit energy consumption and carbon emissions. Through integrated economic and technical analysis, using a 48-story residential building project as an example, replacing all ordinary concrete composite beams with HTBFS composite beams reduced overall costs by approximately 141,000–500,000 Yuan, highlighting both strong cost control potential and the promising prospects of green construction materials.

In summary, HTC composite beams exhibit outstanding flexural performance, crack control capacity, plastic deformation behavior, and sustainability advantages, demonstrating excellent engineering feasibility and significant potential for practical application. This research provides both theoretical and experimental support for the engineering application of high-titanium blast furnace slag in prefabricated concrete structures. Notably, the HTBFS composite beam investigated in this study has already been incorporated into the technology reserve of Panzhihua Iron and Steel Group, and a related invention patent has been filed and granted in Luxembourg [57]. These developments indicate that the proposed composite beam system has reached a high level of technical maturity and is expected to be applied in future engines. It should be noted that, due to the relatively high fabrication cost of individual specimens, a composite beam composed of HTC and OPC was not included as a direct control specimen in this study, which constitutes a limitation of the experimental program but does not affect the main conclusions drawn. Moreover, the present work mainly focuses on the flexural behavior of HTBFS composite beams under short-term loading conditions. Future studies are therefore recommended to investigate their mechanical performance under long-term loading, as well as other structural and durability-related properties, such as shear behavior, fire resistance, chloride penetration resistance, and freeze–thaw performance, in order to achieve a more comprehensive evaluation of this type of composite member.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.; Methodology, L.L. and J.S.; Software, Z.W. and C.D.; Writing—original draft, L.L.; Writing—review & editing, L.L. and J.S.; Supervision, J.S.; Funding acquisition, J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HTBFS | High Titanium Blast Furnace Slag |

| HTC | HTBFS-based concrete |

| OPC | Ordinary Portland concrete |

| PC | Prefabricated reinforced concrete |

| SF | Silica fume |

| WRA | water-reducing admixture |

| FAC | Fly ash ceramsite |

Appendix A

Energy Calculation and Image Generation Code

clear all;clc

% Example data (replace with actual data)

x = [0, 0.36077, 0.54095, 1.0227, 1.53517, 1.86648, 2.99709, 3.31336, 3.79574, 4.47386, 4.7903, 5.48368, 5.99636, 11.89942]; % Deflection (unit: mm)

y = [0, 41.34607, 67.76693, 105.08067, 128.59857, 151.55777, 199.15897, 220.39537, 241.04237, 276.03987, 292.67857, 323.65173, 341.42267, 355]; % Load (unit: kN)

% Yield point (replace according to experimental results)

Fy = 341.42267; % Yield load (kN)

Dy = 5.99636; % Yield displacement (mm)

% Ultimate point (maximum load and its index)

[Fu, idx_u] = max(y);

Du = x(idx_u);

% -------------------------

% 1. Calculate energy dissipation (area)

energy = trapz(x, y); % Unit: kN·mm

% 2. Energy ratio η

E_elastic = 0.5 * Fy * Dy; % Elastic energy

eta = energy/E_elastic;

% 3. Equivalent damping ratio ξ_eq

xi_eq = (1/(4*pi)) * eta;

% 4. Stiffness degradation coefficient (slope change rate)

K0 = Fy/Dy; % Initial stiffness

Ksec = (Fu − Fy)/(Du − Dy); % Post-yield average stiffness

K_ratio = Ksec/K0; % Stiffness degradation coefficient

% -------------------------

% -------------------------

figure;

hold on;

grid on;

box on;

fill([x, fliplr(x)], [y, zeros(size(y))], [0.8, 0.9, 1], …

‘EdgeColor’, ‘none’, ‘FaceAlpha’, 0.5);

plot(x, y, ‘-o’, ‘Color’, [0, 0.45, 0.74], ‘LineWidth’, 2);

xlabel(‘Deflection (mm)’);

ylabel(‘Load (kN)’);

title(‘Load–Deflection Curve and Performance Indicators’);

info_str = {

sprintf(‘Energy dissipation area = %.1f kN·mm’, energy)

sprintf(‘Energy ratio η = %.2f’, eta)

sprintf(‘Equivalent damping ratio ξ_{eq} = %.3f’, xi_eq)

sprintf(‘Stiffness degradation coefficient = %.2f’, K_ratio)

};

x_text = max(x) − 8;

y_text = max(y)/2;

text(x_text, y_text, info_str, …

‘FontSize’, 12, ‘FontWeight’, ‘bold’, …

‘HorizontalAlignment’, ‘left’, …

‘VerticalAlignment’, ‘middle’, …

‘BackgroundColor’, ‘white’, …

‘EdgeColor’, ‘black’, …

‘Margin’, 8);

% Console output of calculation results

fprintf(‘=======================\n’);

fprintf(‘Performance indicator calculation results:\n’);

fprintf(‘-----------------------\n’);

fprintf(‘Energy dissipation area = %.1f kN·mm\n’, energy);

fprintf(‘Energy ratio η = %.2f\n’, eta);

fprintf(‘Equivalent damping ratio ξ_eq = %.3f\n’, xi_eq);

fprintf(‘Stiffness degradation coefficient = %.2f\n’, K_ratio);

fprintf(‘=======================\n\n’);

Appendix B

Concrete constitutive relationship, GB50010-2010.

Figure A1.

Constitutive curve of concrete.

Figure A2.

Constitutive relationship of reinforcement.

Tensile stress–strain equation

Compression stress–strain equation

where denotes the damage evolution parameter of concrete under uniaxial tension;

- αt denotes the descending-branch parameter of the uniaxial tensile stress–strain curve of concrete;

- denotes the representative value of the uniaxial tensile strength of concrete

- denotes the peak tensile strain of concrete corresponding to the uniaxial tensile strength.

Table A1.

Compressive/tensile behavior.

Table A1.

Compressive/tensile behavior.

| Yield Stress | Inelastic Strain | Damage Parameter | Yield Stress | Cracking Strain | Damage Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29.09660676 | 0 | 0 | 1.951363778 | 0 | 0 |

| 30.28610312 | 0.000488399 | 0.204984672 | 2.169095168 | 2.31554 × 10−5 | 0.150395904 |

| 30.91423268 | 0.000636918 | 0.242719493 | 2.327171202 | 2.91817 × 10−5 | 0.170311253 |

| 31.0992 | 0.000797713 | 0.279434598 | 2.39 | 3.78465 × 10−5 | 0.202333712 |

| 29.68718964 | 0.001168664 | 0.35732306 | 2.180107001 | 6.4471 × 10−5 | 0.304542541 |

| 26.7388209 | 0.001582174 | 0.43531545 | 1.884684147 | 9.34647 × 10−5 | 0.401343698 |

| 23.54127539 | 0.002002586 | 0.504374321 | 1.628732486 | 0.000121365 | 0.479420364 |

| 20.63186688 | 0.002415016 | 0.562546588 | 1.424710617 | 0.000147827 | 0.540961232 |

| 18.15010885 | 0.0028156 | 0.610754665 | 1.263822998 | 0.000173094 | 0.589842727 |

| 16.08055244 | 0.003204766 | 0.650668347 | 1.135702694 | 0.000197453 | 0.62928234 |

| 14.3625874 | 0.003584192 | 0.683910901 | 1.032085411 | 0.000221134 | 0.661643529 |

| 12.93140222 | 0.003955674 | 0.711839179 | 0.946914865 | 0.000244303 | 0.688619737 |

| 11.73061641 | 0.004320774 | 0.735527696 | 0.875828974 | 0.000267083 | 0.71142884 |

| 10.71455868 | 0.004680757 | 0.75581144 | 0.81567142 | 0.00028956 | 0.730958495 |

| 7.386107542 | 0.006432145 | 0.824419365 | 0.615343657 | 0.00039916 | 0.797627659 |

| 5.587308286 | 0.008141159 | 0.863411193 | 0.501831913 | 0.000506356 | 0.836538145 |

| 4.477688714 | 0.009831083 | 0.888377917 | 0.428167559 | 0.000612448 | 0.862166894 |

| 3.729688304 | 0.01151099 | 0.905683854 | 0.376118307 | 0.000717942 | 0.880398809 |

| 3.193037216 | 0.013185042 | 0.918368873 | 0.337154652 | 0.000823072 | 0.89407661 |

| 2.789975901 | 0.014855394 | 0.928058785 | 0.306747509 | 0.000927966 | 0.904744172 |

| 2.476485293 | 0.016523264 | 0.935699156 | 0.282262888 | 0.001032696 | 0.913313957 |

| 1.583085338 | 0.024843945 | 0.958023586 | 0.206915815 | 0.00155504 | 0.939399878 |

| 1.16235496 | 0.033151532 | 0.968850349 | 0.167150807 | 0.002076399 | 0.952830472 |

| 0.91804369 | 0.041454232 | 0.97523944 | 0.142042589 | 0.002597352 | 0.961107884 |

| 0.758508895 | 0.049754584 | 0.979454415 | 0.124524181 | 0.003118095 | 0.966757896 |

References

- Liu, Y.; Tong, W.; Li, Q.; Yao, F.; Li, Y.; Li, H.X.; Huang, J. Study on Complexity of Precast Concrete Components and Its Influence on Production Efficiency. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 9926547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Luo, L.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Bi, G.; Antwi-Afari, M.F. An Analysis on Promoting Prefabrication Implementation in Construction Industry towards Sustainability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. Research and Application of Intelligent Construction in Prefabricated Building Construction. Sustain. Environ. 2023, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Robinson, E.J.Z. The labour force in a changing climate: Research and policy needs. PLoS Clim. 2023, 2, e0000131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestas, N.; Mullen, K.J.; Powell, D. The Effect of Population Aging on Economic Growth, the Labor Force and Productivity; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Nurdiawati, A.; Kanwal, Q.; Al-Humaiqani, M.M.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Assessing and mitigating environmental impacts of construction materials: Insights from environmental product declarations. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 110929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, V.; Soares, N.; Raposo, N.; Marques, P.; Freire, F. Prefabricated versus conventional construction: Comparing life-cycle impacts of alternative structural materials. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 41, 102705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Wang, F.; Yang, X. The Efficiency of the Chinese Prefabricated Building Industry and Its Influencing Factors: An Empirical Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwokediegwu, Z.Q.S.; Ilojianya, V.I.; Ibekwe, K.I.; Adefemi, A.; Etukudoh, E.A.; Umoh, A.A. Advanced materials for sustainable construction: A review of innovations and environmental benefits. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 2024, 5, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, C.; Siddiqua, S.; Arnepalli, D.N. Utilization of Recycled Industrial Solid Wastes as Building Materials in Sustainable Construction. In Advances in Sustainable Materials and Resilient Infrastructure; Reddy, K.R., Pancharathi, R.K., Reddy, N.G., Arukala, S.R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 61–75. ISBN 978-981-16-9744-9. [Google Scholar]

- Sandanayake, M.; Bouras, Y.; Haigh, R.; Vrcelj, Z. Current Sustainable Trends of Using Waste Materials in Concrete—A Decade Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Ruan, Y. Prefabricated concrete components combination schemes selection based on comprehensive benefits analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Chen, Y.; Chang, R. Scheduling optimization of prefabricated construction projects by genetic algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertram, N.; Fuchs, S.; Mischke, J.; Palter, R.; Strube, G.; Woetzel, L. Modular Construction: Modular Construction: From Projects to Products. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/operations/our-insights/modular-construction-from-projects-to-products (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- Ferdous, W.; Bai, Y.; Ngo, T.D.; Manalo, A.; Mendis, P. New advancements, challenges and opportunities of multi-storey modular buildings—A state-of-the-art review. Eng. Struct. 2019, 183, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghasizadeh, S.; Tabadkani, A.; Hajirasouli, A.; Banihashemi, S. Environmental and economic performance of prefabricated construction: A review. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 97, 106897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Huang, B. Application of Pre-Wetted High Titanium Heavy Slag Aggregate in Cement Concrete. Materials 2022, 15, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Shen, J.; Guo, P. High titanium heavy slag powder as a sustainability filler and its influence on the performance of asphalt mortar. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 25, 5586–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.K.; Chen, W.; Huang, S.H.; Li, Y.M. Mechanics performance of complex high titanium heavy slag reinforcement concrete beam. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 168, 2013–2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sichuan Province Engineering Cost Information Network. Sichuan Province Material Price Information Reporting and Release System. Available online: http://202.61.90.35:8032/pubpages/pricelist.aspx (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Pedro, D.; De Brito, J.; Evangelista, L. Performance of concrete made with aggregates recycled from precasting industry waste: Influence of the crushing process. Mater. Struct. 2015, 48, 3965–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Xu, L.; Cai, J.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, W.; Pan, J. Feasible use of titanium slag in improving properties of low carbon fire-resistive cementitious composites at elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 416, 135272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yang, Y.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, L. The restructuring-sintering mechanism of calcium alumino-titanate in tundish permanent lining castables. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 29282–29289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Deng, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Deng, G.; Yang, T.; Yang, Y. Effect of different curing methods on the preparation of carbonized high-titanium slag based geopolymers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 342, 128023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACI Committee. Blast Furnace Slag As Concrete Aggregate. J. Proc. 1930, 27, 183–219. [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita, H. Experimental study on the chemical durability of concrete mixed with blast furnace slag powder. In Proceedings of the Symposium on the Application of Blast Furnace Slag Fine Powder in Concrete; Japan Society of Civil Engineers: Tokyo, Japan, 1987; pp. 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.L. Research and application of high titanium heavy slag of Panzhihua iron and steel as concrete coarse aggregate. Sichuan Build. Sci. 1983, 3, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.L. The Research and Application of High Titanium and Heavy Mineral Residue Concrete. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.K. Basic Research on the Application of Full-Height Titanium Heavy Slag Concrete. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, T. Preparation and application of high performance pumping C50 concrete using heavy titanium slag sand. Concrete 2014, 59, 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Li, R.Y.M.; Jiao, T.; Wang, S.; Deng, C.; Zeng, L. Research on the development and joint improvement of ceramsite lightweight high-titanium heavy slag concrete precast composite slab. Buildings 2023, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, R.Y.M.; Su, D.; Gong, H.; Zhang, X. Experimental Study on Seismic Performance of Precast High-Titanium Heavy Slag Concrete Sandwich Panel Wall. Buildings 2024, 14, 2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yi Man Li, R.; Jotikasthira, N.; Li, K.; Zeng, L. Experimental Study on Lightweight Precast Composite Slab of High-Titanium Heavy-Slag Concrete. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6665388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Chen, W.; Ruan, X.; Tang, X. Experimental study on axial compression behavior and bearing capacity analysis of high titanium slag CFST columns. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.W.; Guo, X.Y.; Song, L. Experimental study on flexural behavior of High Titanium Heavy Slag Concrete beam. In Green Building, Materials and Civil Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Ren, D. Quantitative study on external benefits of prefabricated buildings: From perspectives of economy, environment, and society. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 86, 104132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, Y.A.; Dinata, Y. Innovation of Prefabrication Construction Methods for Cost and Time Efficiency in The High Rise Building Project of Perum Perumnas. Media Komun. Tek. Sipil 2022, 28, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W. Experimental investigation on composite beams under combined negative bending and torsional moments. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2020, 24, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, A.A.; Eng, P. Structural and economic benefits of precast/prestressed concrete construction. PCI J. 2001, 46, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Gu, R. Experiment and Analysis of Mechanical Properties of Lightweight Concrete Prefabricated Building Structure Beams. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2022, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.Z.; Gao, G.; Xu, Y.L.; Fan, S.L. Experimental study on flexural mechanical properties of recycled concrete composite beams. Struct. Eng. 2012, 28, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Wang, K.; Song, C. Experimental study on flexural performance of prestressed recycled concrete composite beams. J. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2022, 39, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Huang, L.; Tu, W. Experimental study on flexural behavior of concrete composite beams in precast part with recycled fired brick aggregates. Build. Struct. 2022, 52, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Experimental Study on Mechanical Properties of Shale Ceramsite Lightweight Aggregate Concrete Composite Beams with HRB500 Reinforcement. Master’s Thesis, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Feng, C.; Zhu, C.; Xiao, Z.; He, Z.; Wang, J. Experimental study on fatigue properties of prestressed ceramsite concrete composite beams. Ind. Build. 2022, 52, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Zhong, X.; Yu, Q.; Li, X. Experimental study on flexural performance of HRB500 reinforced lightweight aggregate concrete composite beams. Build. Struct. 2019, 49, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Qin, F.; Yang, Q.; Peng, X.; Xu, B. A Review of Research on the Interfacial Shear Performance of Ultra-High-Performance Concrete and Normal Concrete Composite Structures. Coatings 2025, 15, 414. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. Concrete Structure Design Code GB50010-2010, 1st ed.; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2024; ISBN 9787508209173. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 51231-2016; Technical Standards for Prefabricated Concrete Buildings. China Architecture Press: Beijing, China, 2016.

- JGJ1-2014; Technical Specification for Prefabricated Concrete Structures. China Architecture Press: Beijing, China, 2014.

- GB/T 50152-2012; Standard for Test Methods of Concrete Structures. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development PRC: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Shen, P.S. Principles of Concrete Structure Design; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2020; ISBN 9787040539318. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.K.; Chen, W.; Li, B. The influence of adding fine powder on the performance of high-titanium heavy slag mortar. Shanxi Archit. 2006, 157–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, H.; Sun, J.; Wang, X.; Deng, C. Study on the Influence of Titanium Dioxide Content Variation on Concrete Properties. Sichuan Cem. 2023, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C. Study on Basic Mechanical Properties of High-Content Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer and Flexural Properties of Prefabricated Composite Beams. Master’s Thesis, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hai, C. Experimental Study on Mechanical Properties of Prefabricated Concrete Bonding Surface and Composite Beams. Master’s Thesis, Anhui University of Science and Technology, Huainan, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.K.; Xu, M.; Yu, Y.; Xie, G.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Li, L.; Su, D.; Shi, X.; Zhang, X. Ein Stapelbalken Aus Hochtitanhaltigem Hochofenschlackenbeton und Sein Herstellungsverfahren. LU Patent 508,659, 28 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |