Abstract

To achieve the “dual carbon” goals, green construction technologies (GCTs) are in transition from pilot projects to full-scale promotion in the Chengdu–Chongqing Economic Circle. Previous studies have largely overlooked the quantitative analysis of parameters influencing stakeholder decision-making and the consideration of risk preferences in the process of GCTs of application. Based on evolutionary game and prospect theory, this study establishes a tripartite evolutionary game model involving the government, owners, and constructors. Through model derivation and numerical simulation, it analyzes the strategic evolution and parameter sensitivity of each stakeholder at different lifecycle phases of GCTs. Results uncover a three-stage path: strategy adjustment range, fast convergence range, and slow convergence range. Government funds achieve peak efficiency in the fast convergence range. Owners react most strongly to incentives, contractors to cost changes. State-owned enterprises rely on policy signals, whereas private enterprises focus on market returns and risk expectations. Targeted promotion mechanisms and policy recommendations are proposed, offering a theoretical basis and practical route for precise government intervention and low-carbon transformation of the construction industry.

1. Introduction

The construction industry is a primary contributor to the global climate crisis, accounting for 32% of worldwide energy consumption and 34% of global CO2 emissions [1]. In response to climate risks, a growing number of countries are striving to transition toward low-carbon development through the transformation of the construction industry [2]. As the world’s largest developing country and carbon emitter, China has explicitly committed to achieving peak carbon emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060. Currently, energy consumption in China’s urban and rural construction sectors reaches 2.42 billion tce, representing 44.8% of the national total, while CO2 emissions amount to 5.13 billion tons, accounting for 46.3% of the country’s emissions [3]. These data have motivated the Chinese government to promote the transition of the construction industry toward low-carbon, industrialized, intelligent, and lean practices. The Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Circle is the most developed urbanization region in western China, an important part of building the Ecological Shield of the Yangtze River, and a key strategic support for Western development and the Belt and Road Initiative [4]. In recent years, local government has designated 7 intelligent construction pilot cities, 5 pilot counties/districts, and 149 pilot projects, aiming to explore developmental pathways, regulatory models, policy frameworks, and technological innovations for the construction industry.

However, due to the low market share of GCTs, high capital costs, low short-term returns, and overly rigid incentives and regulations, the application of GCTs remains limited to pilot projects and government-invested projects, falling short of commercialization. According to the “Key Tasks for Promoting Intelligent Construction and Prefabricated Buildings in Sichuan Province by 2025”, over 42% of new buildings in the province are expected to be prefabricated [5]. This target remains considerably lower than Shanghai’s adoption rate of 91.7%. Theoretically, promoting GCTs is a systematic endeavor involving multiple stakeholders: the government as the policy maker and the market regulator, and project owners and constructors as implementers. The widespread adoption of GCTs hinges on a balance of interests among these stakeholders, who often hold divergent goals [6]. Unfortunately, there has been scant research on interest balance and strategic decision-making among stakeholders in the adoption of GCTs, and limited attention has been paid to the high-quality development of the construction industry within the Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Circle.

Drawing on prospect theory and evolutionary game analysis, this study examines how government, owners, and constructors within the Chengdu–Chongqing Economic Circle choose strategies and interact during the adoption of GCTs, thereby providing a reference for government policy design and the high-quality development of the construction industry.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Status of GCTs

Green construction refers to engineering activities that maximize resource conservation while ensuring quality and safety, fulfilling green construction requirements, and producing sustainable building products. Its implementation relies on continuous technological innovation [7].

Developed countries place strong emphasis on the green transformation of construction technologies, prefabricated buildings, digital twins, construction robotics, and other GCTs to advance sustainability in the construction industry [8]. Prefabricated buildings, as a sustainable construction solution, have achieved an adoption rate exceeding 80% in Sweden [9]. Pollutants generated during on-site assembly, such as dust, noise, light, and air pollution, can be effectively managed using Industry 4.0 technologies such as AI, digital twins, wearable devices, and IoT [10]. To enhance productivity and reduce energy waste, stakeholders widely deploy technologies such as automated prefabrication systems, robotics, drones, autonomous vehicles, and exoskeletons [11].

In China, green construction remains at an early developmental stage and has yet to fully meet national sustainability objectives [12]. Qian [13] asserted that intelligent construction is an essential pathway to achieving green construction. He advocated for the integration of IoT, big data, 5G, and AI into engineering practices to enable more automated, efficient, and low-carbon or even zero-carbon construction processes. Current GCTs in China span multiple domains: design innovation, sustainable materials, energy-efficient structural systems, resource recycling, prefabricated buildings, automated machinery and robots, full-process monitoring and virtual simulation, and digital platforms [8]. To upgrade “China’s construction” paradigm, the industry requires breakthroughs in engineering software, construction IoT, intelligent machinery, and intelligent decision-making systems [14], as well as integrated collaboration across the entire industry chain encompassing material production, design, construction, operation, and resource reuse [15].

2.2. Benefits and Barriers of GCTs

GCTs deliver substantial environmental and economic benefits, which are increasingly driving their adoption as environmental awareness grows [16]. Environmental benefits serve as a primary motivator, with studies confirming that GCTs reduce construction waste, minimize ecological disruption, and cut carbon emissions [6,17,18]. Lu et al. [17] evaluated 62 prefabricated building projects and found an average carbon reduction rate of 12.54% compared to traditional concrete buildings. Economic benefits are the core driving force for the application of GCTs. Zhang et al. [19] reported that using BIM for urban rail transit projects optimized construction planning, site layout, and resource allocation, yielding savings of CNY 13.25 million on steel and CNY 5.96 million on labor costs.

Despite these advantages, the commercialization of GCTs faces significant challenges. High initial investment and prolonged payback periods represent major barriers, particularly during economic downturns when financing becomes constrained [9,20]. Additional obstacles include regulatory hurdles and technical constraints exacerbated by a lack of trust among stakeholders under conventional contractual frameworks, which discourages the sharing of knowledge and innovation [21]. Deep-rooted conventional mindsets and resistance to changing established non-green practices further impede GCTs proliferation [22]. To overcome these barriers, government interventions, such as incentive policies, green development initiatives, and collaborative industry–research partnerships, have been identified as vital enabling mechanisms [16].

2.3. Evolutionary Game Theory and Prospect Theory

Game theory offers a mathematical foundation for analyzing strategic interactions among decision-makers [23]. Unlike traditional games, in which players are fully rational, evolutionary games involve players with bounded rationality and partial information, who continuously learn and adjust to gradually approach optimal strategies. This approach aligns more closely with real-world decision-making behavior [6]. Chen et al. [24] employed evolutionary game theory to examine manufacturers’ strategies under various carbon tax and subsidy schemes, demonstrating that dynamic policy mechanisms effectively encourage low-carbon production. Similarly. Qian et al. [25] studied innovation alliances in major engineering projects and identified knowledge absorption capacity, risk perception, and distrust as key constraints on technological innovation.

Prospect theory describes decision-making under uncertainty by proposing that individuals evaluate outcomes relative to a reference point and make choices based on their risk preferences. This behavioral framework has been integrated with evolutionary game theory to capture the psychological utility of players facing uncertain costs and benefits [20]. Li et al. [26] developed a tripartite evolutionary game model involving the government, social capital, and engineering consulting firms, revealing that risk attitudes affect the speed of strategy adoption but not the final equilibrium. In a study on BIM platform collaboration, An et al. [27] found that greater loss aversion leads players to prefer more aggressive strategies.

2.4. Literature Commentary

Existing literature provides a valuable foundation for this research. However, most studies focus either on technological innovations and case studies of GCTs or on qualitative analyses of drivers and barriers from environmental, economic, social, and managerial perspectives. Few offer quantitative assessments of policy impacts on stakeholder strategies or establish clear implementation priorities. Moreover, the influence of risk preferences on decision-making is often overlooked, despite the fact that varying risk perceptions among individuals significantly affect their choices. To address these gaps, this study employs evolutionary game theory and prospect theory to analyze the strategic interactions among the government, owners, and constructors in adopting GCTs.

3. Research Methods

This study employs prospect theory and evolutionary game analysis to examine the strategy choices and interaction mechanisms among government, owners, and constructors during GCTs adoption. Numerical simulation is then used to clarify the strategy evolution path and parameter sensitivity. The main methods are prospect theory, evolutionary game analysis, and numerical simulation. The research steps are as follows: first, the literature analysis is used to identify the benefit and cost parameters of each stakeholder; second, prospect theory is applied to determine the perceived value of these parameters; third, evolutionary game theory is used to construct the game model and conduct stability analysis; fourth, a specific case and numerical simulation are combined to analyze the strategy evolution process and the sensitivity of each parameter.

3.1. Prospect Theory

Prospect theory captures the asymmetric perception of risk. It employs a value function and a probability weighting function to describe the decision process. The perceived value V is determined by the value function and the weighting function , expressed as:

where = − denotes the difference between the actual outcome and the reference point; in this study = 0. is the gain-sensitivity coefficient, is the loss-sensitivity coefficient, is the loss-aversion factor, pi is the probability of occurrence, and σ is the decision-weight coefficient, , , sensitivity coefficients typically between 0.8 and 0.95, and loss-aversion factors usually between 1.5 and 3.

3.2. Evolutionary Game Theory

Evolutionary game theory uses tools such as payoff matrices and replicator dynamic equations to describe how strategies spread within a population and how equilibria emerge, emphasizing the interaction between selection mechanisms and random mutations. The replicator dynamic equation is expressed as:

where and are the expected payoffs of the player under different strategies, and is the average payoff. when = 0 and , the system is in a unilaterally stable state. Multilateral stability requires analysis using the Jacobian matrix, which is defined as [22]:

When all eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix at an equilibrium point are negative, the equilibrium is an evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS); when 0, the equilibrium is unstable; when eigenvalues are mixed (positive and negative), the equilibrium is a saddle point and remains unstable.

3.3. Numerical Simulation

This study performs the numerical simulation of the evolutionary game model in MATLAB (release 2024b). The routine relies on the ode45 solver; initial conditions, step lengths, and iteration numbers are set separately for each parameter set, as detailed in the numerical-model section, Table 3 and Table 4.

4. Tripartite Evolutionary Game Modeling

4.1. Stakeholder Analysis

Active governmental promotion is a prerequisite for the widespread adoption of GCTs. The government serves as both policy maker and regulatory supervisor, exerting influence through policy formulation, regulatory oversight, and public awareness campaigns, while also providing technical standards, financial subsidies, and talent support to owners and constructors.

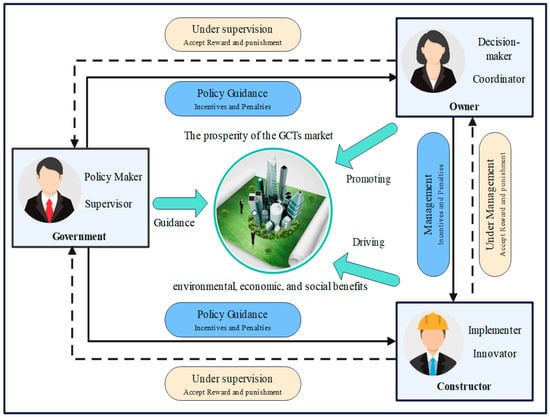

The owners act as the decision-makers and coordinators for GCTs’ application, selecting suitable scenarios under policy guidance and engaging constructors through market mechanisms to implement GCTs. The constructors, as the executor and innovator, are subject to government regulation and the owners’ management, responsible for applying these technologies in projects and participating in innovation. The government, owners, and constructors play distinct yet interconnected roles, mutually influencing and reinforcing each other to advance GCTs’ development and application, thereby achieving environmental, economic, and social benefits [18,24,25]. Their interrelationships are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mechanism of action between the government, owners, and constructors.

4.2. Model Assumptions and Parameter Selection

Given that active governmental promotion and positive government–enterprise interaction are essential for technology diffusion, we propose the following assumptions to simulate these dynamics:

Assumption 1.

The evolutionary game involves three stakeholders: the government, owners, and constructors. All exhibit bounded rationality and diverse risk preferences. They adapt to changes and dynamically adjust their strategies to maximize their benefits.

Assumption 2.

The government has two strategies: participate and not participate. “participate” means providing policies such as special funds, financial incentives, tax breaks, and loan support, along with supervising technology application and penalizing non-compliant stakeholders. “not participate” indicates that the government refrains from intervention due to fiscal constraints or because GCTs have achieved market maturity.

Assumption 3.

Both the owners and constructors have two strategies: adopt and not adopt. “adopt” means adopting GCTs due to government incentives, enhanced brand image, or increased benefits. If they choose “not adopt,” it is because high costs and limited short-term returns lead them to continue using conventional methods.

Assumption 4.

Let x(0 ≤ x ≤ 1) x(0 ≤ x ≤ 1) denote the proportion of government participation in promoting GCTs, and y(0 ≤ y ≤ 1) and z(0 ≤ z ≤ 1) represent the proportions of owners and constructors adopting GCTs.

Throughout the game, each stakeholder’s benefits and costs influence the dynamic interactions, and the outcomes continually reshape the benefits and costs of others, leading to evolving strategies. To analyze this process, we define relevant parameters and their meanings, as shown in Table 1. For conciseness, we do not reiterate cases where one stakeholder’s benefit constitutes another’s cost.

Table 1.

Description of major parameters.

4.3. Model Establishment and Analysis

4.3.1. Prospect Theory

Owing to the bounded rationality of the stakeholders, their risk preferences and subjective perceptions influence the valuation of benefits and costs. Let , 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3 represent the gain and loss sensitivity coefficients for the government, owner, and constructor, respectively. Using Equations (1)–(3), the subjective values of the parameters in Table 1 are computed as follows:

Similarly, the following subjective values are obtained: , , , , , 2, 2, , , , 3, 3. Because constructors are typically more sensitive to losses than owners, the initial values of 2, 3, 2, 3, 2, and 3 were set at 0.88, 0.92, 0.88, 0.94, 1, and 1.5, respectively, while all three coefficients for the government were set at 1.

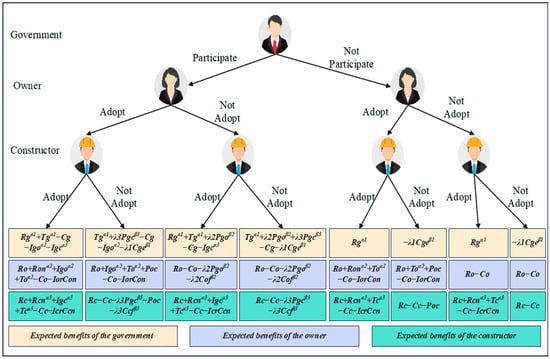

4.3.2. Expected Benefits

Based on the model assumptions, parameter settings, and subjective valuations, the expected benefits for the government, owners, and constructors under different strategy combinations are calculated, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Game tree of the government, owners, and constructors.

4.3.3. Replicator Dynamic Equations

From Figure 2, the expected benefits for the government under participation and non-participation strategies are denoted as and , respectively:

Using Equations (4) and (5), the replicator dynamic equation for government participation in GCTs promotion was obtained. The replicator dynamic equations for the owners and constructors are derived similarly:

4.4. Model Stability Analysis

4.4.1. Unilateral Stabilization Strategy

From the government’s replicator dynamic equation:

- (1)

- If [(+2+3Cg)y(+2)]/(+2), then , and the system is stable for any x.

- (2)

- If , only when or x = 1, .

The first-order partial derivative of with respect to is given by:

- (3)

- If and , then 0 is an ESS.

- (4)

- If and , then 1 is an ESS.

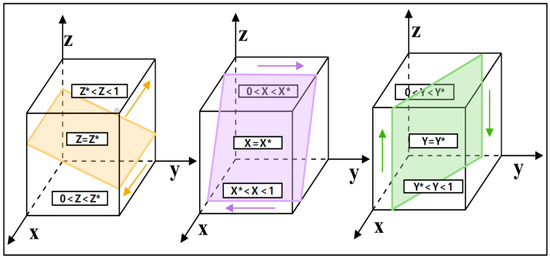

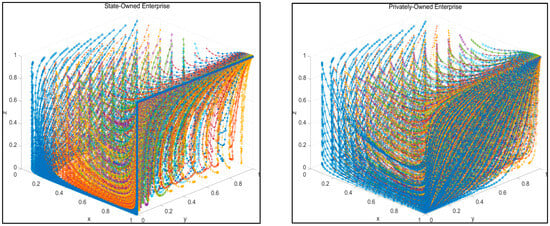

The strategy space is divided by the plane .In the region where , 0 is the equilibrium point; In the region where , 1 is the equilibrium point, as shown in Figure 3. Similar analyses are conducted for the owners and constructors, determining their respective ESS conditions and equilibrium regions, also shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Phase diagram of evolutionary strategy.

4.4.2. Multilateral Stabilization Strategy

When = = = 0, there exist eight pure-strategy equilibrium points: E1(0, 0, 0), E2(1, 0, 0), E3(0, 1, 0), E4(0, 0, 1), E5(1, 1, 0), E6(1, 0, 1), E7(0, 1, 1), E8(1, 1, 1), and one mixed-strategy point E9(x*, y*, z*). By substituting the equilibrium-point values into the Jacobian matrix, we obtain the eigenvalues for each equilibrium point, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Eigenvalues of Equilibrium Points.

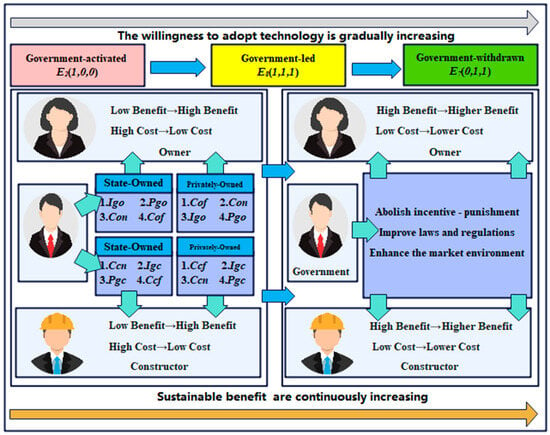

Drawing on industry life cycle theory [26], this study focuses on three equilibrium points corresponding to key phases: E2(1, 0, 0) (government-activated market), E8(1, 1, 1) (government-led market), and E7(0, 1, 1) (government-withdrawn market).

In the government-activated market phase, driven by the high-quality development requirements of the environment, economy, and society, the government must vigorously promote GCTs that benefit environmental improvement and enhance production efficiency. In this phase, owners and constructors maintain a cautious, wait-and-see attitude. According to the eigenvalue 1 of E2(1, 0, 0), as long as the benefits gained by the government from promoting new technology exceed the promotion costs, the government will continue to choose the “Participate” strategy, that is, Tgα1 + λ2Pgoβ2 + λ3Pgcβ3Cg; based on eigenvalues 2 and 3, in the early stage of the government-activated market phase, the additional costs for owners and constructors are greater than the benefits, so they will continue to choose the “Not adopt” strategy, that is, IorConλ2Pgoβ2 + λ2Cofβ2 + Igoα2 + Toα2 + Poc and IcrCcn Igcα3 + λ3Ccfβ3 + λ3Pgcβ3 + Rcnα3 + Tcα3. In this case, E2(1, 0, 0) is the equilibrium point.

In the government-led market phase, the government strengthens incentive policies, implements penalty measures, and cultivates industry talents. According to the eigenvalues 2 and 3 of E8(1, 1, 1), when the benefits for owners and constructors exceed the additional costs, they will choose the “Adopt” strategy, which is IorCon λ2Pgoβ2 + λ2Cofβ2 + Igoα2 + Ronα2 + Toα2 and IcrCcn Igcα3 + λ3Ccfβ3 + λ3Pgcβ3 + Poc + Rcnα3 + Tcα3. In this case, E8(1, 1, 1) is the equilibrium point.

In the government-withdrawn market phase, the costs of GCTs continue to decrease, and benefits continue to increase. When owners and constructors can ensure benefits are greater than the additional costs without government incentives, according to the eigenvalues 2 and 3 of E7(0, 1, 1), they will choose the “Adopt” strategy, which is IorCon Ronα2 + Toα2 and IcrCcn Poc + Rcnα3 + Tcα3. In this case, E7(0, 1, 1) is the equilibrium point, and the application of technology enters a fully market-oriented stage, with the government only needing to perform routine supervision.

5. Numerical Simulations

5.1. Case Selection

To visualise the evolutionary trajectory and isolate the heterogeneous impacts of parameters on different types of enterprises, we screened the lists including (i) Sichuan Intelligent Construction Demonstration Enterprises, (ii) Sichuan Construction Industry Backbone Enterprises, (iii) the Digital Transformation Application Report for the Construction Sector, (iv) the Digital Development Research Report for Construction Enterprises, and (v) the Research Report on the Development of Private Construction Enterprises. Among the numerous state-owned and private enterprises listed, we selected those whose output value and profit-to-investment ratio were both close to the median, thereby enhancing the representativeness of the sample.

SOE Enterprise 1—Chengdu Construction Engineering Co., Ltd.

An integrated state-owned enterprise engaged in industrial and civil building, mechanical and electrical installation, interior decoration, municipal public works, and construction industrialisation. The enterprise employs more than 900 staff, signed contracts worth CNY 6 billion in 2024, and posted a net profit of CNY 150 million. It allocates roughly CNY 6 million annually to R and D and application of GCTs.

Private Enterprise 2—Mianyang Construction Engineering Co., Ltd.

A private, multi-disciplinary constructor active in housing, highway, and municipal infrastructure. The enterprise has 83 employees, signed contracts worth CNY 400 million in 2024, earned a net profit of CNY 8.16 million, and invests about CNY 1 million per year in green-construction R and D and deployment.

5.2. Parameter Assignment

Building on the above enterprise data, government fiscal files, policy documents, statistical bulletins, and the related literature, we assigned values to the model parameters. The estimation formulae and data sources are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

The parameter values unit: CNY 10k.

Table 3.

The parameter values unit: CNY 10k.

| Param. | Estimation Formula | Data Sources and Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Tg | Tg = OV × ΔCO2 × CP/10k | 1. ΔCO2-Carbon-reduction per unit output Sources: Research/statistical Report Value: 0.0195 tCO2/10kCNY 2. CP-Carbon price Sources: China Carbon Trading Platform Both Value: 68 CNY/t 3. GS-Government subsidy rate Sources: Policy document Both Value: ≤30% of the additional cost 4. GC-Government regulatory cost per unit of output Sources: Government final budget accounts Both Value: 0.0000486 CNY/10k CNY 5. PI-Maximum profit/investment ratio Sources: Research/statistical Report Both Value: 18.87% 6. GI-GCTS implementation contribution rate Sources: [29] Both Value: GIO-Owner 40%; GIC-constructor 60% 7. OV-Corporate output value Sources: Enterprise data Enterprise1 Value: 6 billion CNY Enterprise2 Value: 400 million CNY 8. ROI-Return on Investment Sources: Enterprise data Enterprise1 Value: 75% Enterprise2 Value: 60% 9. MD-Market share decline rate Sources: Enterprise data Enterprise1 Value: 3% Enterprise2 Value: 4% 10. AC-Actual enterprise investment Sources: Enterprise data Enterprise1 Value: 6 million CNY Enterprise2 Value: 1 million CNY 11. NP-Net Profit Sources: Enterprise data Enterprise1 Value: 0.15 billion CNY Enterprise2 Value: 8.16 million CNY |

| Pgo | ≤100 104CNY | |

| Pgc | ≤100 104CNY | |

| Cg | Cg = OV × GC | |

| Igo | Igo = Con × Ior × GS | |

| Igc | Igc = Ccn × Icr × GS | |

| Ron | Ron = Con × Ior × ROI | |

| To | To = Tg × GIO | |

| Poc | ≤100 10K CNY | |

| Con | Con = Ccn × GIO/GIC | |

| Cof | Cof = NP × GIO × MD | |

| Ior | Ior = AC/Con | |

| Rcn | Rcn= Ccn × Icr × ROI | |

| Tc | Tc = Tg × GIC | |

| Ccn | Ccn = NP × PI | |

| Ccf | Ccf = NP × GIC × MD | |

| Icr | Icr = AC/Ccn |

Based on the calculation formulas and data in Table 3, the parameter values can be obtained. It should be noted that both enterprises are currently actively pursuing green transformation, and all data refer to the year 2024, the government-led market phase.

To reproduce the full evolutionary trajectory of GCTs adoption, we back-casted the parameter sets for the other two phases by incorporating changes in external policies, market conditions, and enterprise development observed during the transition from the government-activated to the government-led market stage; the resulting values are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

The parameter values unit: CNY 10k.

Table 4.

The parameter values unit: CNY 10k.

| Param. | Tg | Ron | Igo | To | Pgo | Cof | Rcn | Igc |

| Ent.1 Value(Activated) | 34 | 30 | 10 | 16 | 10 | 0 | 45 | 15 |

| Ent.1 Value(Led) | 80 | 300 | 20 | 31 | 30 | 180 | 450 | 30 |

| Ent.1 Value(Withdrawn) | 0 | 533 | 0 | 191 | 0 | 0 | 800 | 0 |

| Ent.2 Value(Activated) | 3 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 12 | 2 |

| Ent.2 Value(Led) | 6 | 53 | 2 | 2 | 15 | 13 | 80 | 3 |

| Ent.2 Value(Withdrawn) | 0 | 80 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 120 | 14 |

| Param. | Tc | Pgc | Ccf | Cg | Poc | Con | Ccn | Ior/Icr |

| Ent.1 Value(Activated) | 18 | 10 | 0 | 30 | 10 | 1880 | 2800 | 5.3% |

| Ent.1 Value(Led) | 47 | 30 | 270 | 30 | 20 | 1880 | 2800 | 21.2% |

| Ent.1 Value(Withdrawn) | 216 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 1880 | 2800 | 14.4% |

| Ent.2 Value(Activated) | 1 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 102 | 154 | 35.3% |

| Ent.2 Value(Led) | 3 | 15 | 19 | 2 | 10 | 102 | 154 | 64.9% |

| Ent.2 Value(Withdrawn) | 14 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 102 | 154 | 39.1% |

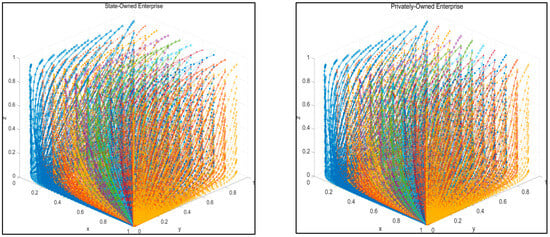

5.3. Multi-Phase Dynamic Evolution Analysis

5.3.1. Government-Activated Market Phase

Using the data from the government-activated market phase in Table 4, the evolutionary game model is simulated in MATLAB to analyze the strategy evolution of the three stakeholders under different initial probabilities.

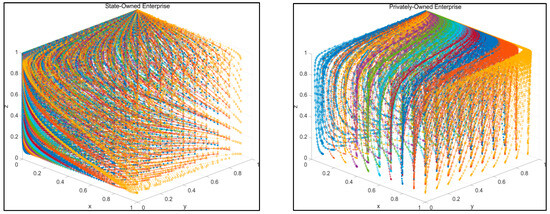

A total of 1000 runs were performed with the three stakeholders’ initial probabilities ranging from 5% to 95% in 10% increments; every trajectory converged to E2(1, 0, 0). In the early promotion phase of GCTs, the government actively advertises the benefits of the new technology, yet—owing to cost pressure and uncertainty about future returns—both SOE and private enterprises still choose the “not adopt” strategy even when they recognize the potential reputation gain. Thus, the profile {participate, not adopt, not adopt} emerges as the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS), as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Evolution process of the system in the Government-activated market phase.

5.3.2. Government-Led Market Phase

Substituting the government-led market phase data into the evolutionary game model, the resulting strategy evolution is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Evolution process of the system in the Government-led market phase.

In the government-led market phase, under the combined pressure of well-targeted subsidies and tougher penalties, both SOE and private enterprises realize that failure to adopt GCTs will land them on integrity blacklists and push their tender scores downward, ultimately eroding market share. Consequently, the “not adopt” strategy flips to “adopt”, and (participate, adopt, adopt) emerges as the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS).

5.3.3. Government-Withdrawn Market Phase

Using the government-withdrawn market phase data in the evolutionary game model, the resulting strategy evolution is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Evolution process of the system in the Government-withdrawn market phase.

In the government-withdrawn market phase, policies, regulations, and technical standards are well established; both SOE and private enterprises adopt GCTs at scale, driving costs down and benefits up. Spurred by pure self-interest, firms continue to apply GCTs even without government incentives, so {not participate, adopt, adopt} becomes the ESS and full marketization is achieved.

5.4. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

According to the evolutionary game model, parameter values significantly influence the strategic choices of the stakeholders. Currently, the green construction industry in the Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Circle is between the government-activated and government-led phase, with GCTs not yet widely adopted. Thus, we focus on how parameter variations for owners and constructors affect the evolution from E2(1, 0, 0) to E8(1, 1, 1), which represents a key government concern. All subsequent sensitivity analyses are based on parameters at the E2(1, 0, 0). The evolution from E8(1, 1, 1) to E7(0, 1, 1) is straightforward, requiring only that owners and constructors remain profitable without direct government involvement, as discussed earlier; thus, it was not simulated again.

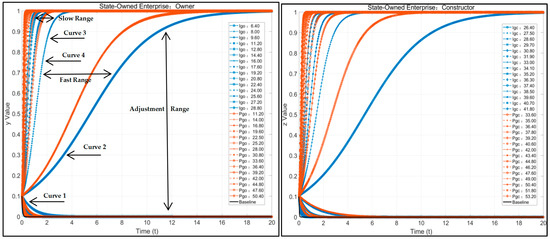

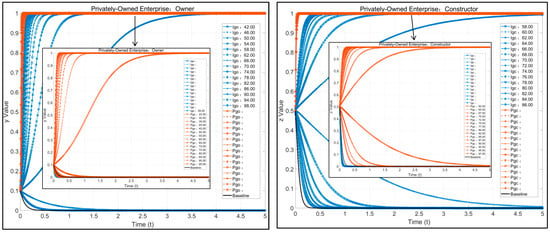

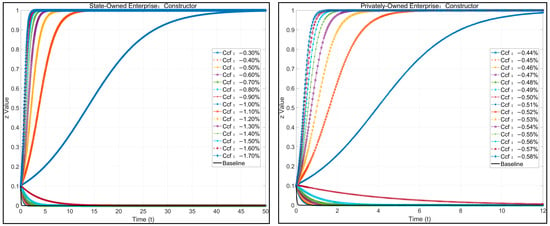

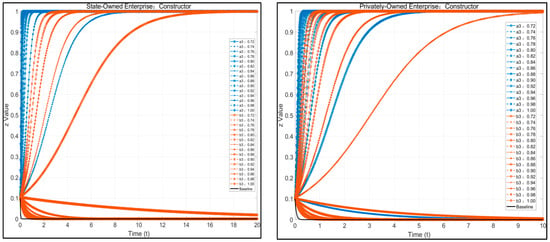

5.4.1. Incentive and Penalty

Incentives and penalties are pivotal for firms’ green and low-carbon transitions and represent the government’s standard tool kit for rolling out new technologies; different reward–punishment bundles produce markedly different evolutionary outcomes. Holding all other parameters constant, and respecting the current policy caps (incentives ≤ 30% of incremental cost; penalties ≤ CNY 1 million), we increased Igo, Pgo, Igc, and Pgc in fixed steps, running 15 replicates per group and sweeping the full admissible range until the simulations produced both convergence-to-zero and convergence-to-one outcomes. The resulting strategy trajectories for SOE and private enterprises are displayed in Figure 7 and Figure 8, respectively.

Figure 7.

SOE Owners and constructors’ response to incentives and penalties.

Figure 8.

Private-enterprise owners and constructors response to incentives and penalties.

Figure 7 simulates the strategy shift of SOE enterprises under incremental steps of Igo = 1.6, Pgo = 2.8, Igc = 1.1, and Pgc = 1.4 (all in CNY 10k). Once Igo, Pgo, Igc, and Pgc are raised by 22.4, 25.2, 37.4, and 37.8 (CNY 10k) above their baseline values, owners and constructors swing rapidly from “not adopt” to “adopt”. The required increment is smaller for incentives than for penalties, implying that, for the same budget, incentives deliver a stronger nudge. Owners also react more sensitively than constructors to external policy changes.

Figure 8 repeats the exercise for private enterprises with steps of Igo = 4, Pgo = 5, Igc = 2, and Pgc = 2.5 (CNY 10k). Here, the critical increments are 70, 75, 82, and 82.5 (CNY 10k), after which the same sharp switch from “not adopt” to “adopt” occurs. The qualitative pattern and relative sensitivity ranking mirror those observed for SOE, but private enterprises require markedly larger policy impulses to alter their strategies.

Examining the curve families in Figure 7 and Figure 8 reveals that, under identical step lengths, each set passes through the same three canonical intervals: strategy adjustment, fast convergence, and slow convergence (Curves 1–4 in Figure 7). Numerically, under the same step length, the reduction in convergence time between Curves 2 and 3 is significantly larger than that between Curves 3 and 4, as reported in Table 5. Table 5 shows that for Igo, Curves 2, 3, and 4 converge to 1 at t = 29.98, 6.69, and 3.87, respectively; the ratio is then computed with the formula:

Table 5.

Convergence Time and Ratio.

Based on the Table 5 results, the interval where the strategy first shifts is labelled the strategy-adjustment Range (e.g., the region between Curves 1 and 2); an interval in which the convergence-time reduction factor is more than seven times larger than in the remaining regions is designated the fast-convergence Range (e.g., the region between Curves 2 and 3); all remaining intervals are referred to as the slow-convergence Range (e.g., the region beyond Curve 3).

5.4.2. Future Development

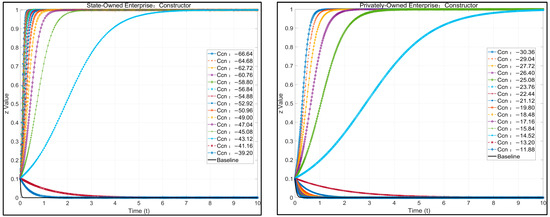

The future-development parameters Cof and Ccf directly capture how changes in market share affect enterprise growth and strategic choice. Market share is driven by external factors such as technology maturity, competitive pressure, and consumer demand; thus, varying Cof and Ccf for both SOE and private enterprises allows us to indirectly assess the influence of these external drivers on strategy selection, as illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

SOE and private-enterprise constructors’ response to future-development coefficients.

Since the evolutionary trends of owners and constructors are almost identical, the owner panels are omitted, and only the key figures are reported. Figure 9 illustrates the constructor Ccf response for both SOE and private enterprises under market share step decreases of 0.1 per cent and 0.01 per cent, respectively. A 1 per cent drop for SOE constructors (or 0.51 per cent for private constructors) triggers an immediate switch from “not adopt” to “adopt”, passing through the same three ranges: the strategy adjustment range, the fast convergence range, and the slow convergence range; the larger the share loss, the faster the switch. Market share erosion is therefore the starkest early warning signal and the most powerful catalyst for technological change. The corresponding thresholds for owners are 1.1 percent for SOEs and 0.37 percent for private enterprises. The data confirm that private enterprises, whose survival hinges on the market, exhibit inherently high sensitivity, whereas SOEs, constrained by bulky management and longer decision chains, display lower market responsiveness.

5.4.3. Cost

Cost is the single most critical parameter in the “adopt” versus “not adopt” decision; holding all other variables constant, we simulated the separate impact of Ccn variations on SOE and private-enterprise constructors, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

SOE and private-enterprise constructors response to costs.

Figure 10 simulates strategy evolution for SOE and private-enterprise constructors under step sizes of 1.96 and 1.32 (CNY 10k) for Ccn, respectively. A cost reduction of 43.12 (CNY 10k) for SOE constructors and 23.76 (CNY 10k) for private constructors triggers an immediate switch from “not adopt” to “adopt”, passing through the strategy adjustment range, the fast convergence range, and the slow convergence range; the larger the cost cut, the faster the switch. Numerically, SOEs require a larger absolute cost reduction to trigger adoption. Yet, owing to different initial outlays, the required percentage reductions are 43.12% and 59.4%, respectively, meaning private enterprises need a significantly higher cost-drop ratio. The corresponding thresholds for owners are 48% for SOEs and 72% for private enterprises. The data confirm that private enterprises, guided purely by market profit, adopt new technologies only when costs fall enough to boost margins visibly; SOEs follow a mixed rationale in which cost is only one factor, alongside the demonstration role demanded by the government during technology roll-out.

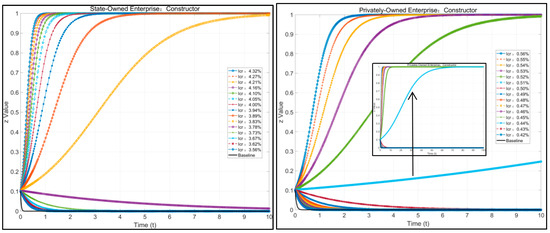

5.4.4. Investment Rate

Investing in GCTs is not a binary “adopt” or “not adopt” decision; the portfolio of available technologies is large, and enterprises typically introduce them in phases and on a selective basis. To examine this staged uptake, we hold all other parameters constant and simulate the separate effects of varying the constructor investment-rate parameter Icr for both SOE and private enterprises, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

SOE and private-enterprise constructors response to investment rate.

The figure simulates the constructor strategy evolution under step sizes of 0.05% and 0.01% for Icr for SOE and private enterprises, respectively. An investment-rate increase of 3.83% for SOE constructors and 0.44% for private constructors triggers an immediate switch from “not adopt” to “adopt”, passing through the strategy adjustment range, the fast convergence range, and the slow convergence range. As the investment rate rises, government incentives increase, and future-development penalties diminish, accelerating the strategy shift. The corresponding thresholds for owners are 3.61% for SOEs and 0.37% for private enterprises. The data reveal that, because private enterprises are markedly smaller, their post-pilot investment-rate increments are lower than those of SOEs; they therefore follow a cautious strategy of small-scale trials and rapid iterations.

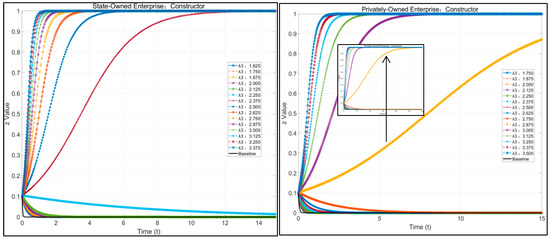

5.4.5. Risk Preference

Since owners’ and constructors’ risk preferences and subjective perceptions shape their choices, we simulated the separate effects of λ2, λ3, α2, β2, α3, and β3 on strategy selection, as shown in Figure 12 and Figure 13.

Figure 12.

SOE and private-enterprise constructors’ response to loss-aversion coefficients.

Figure 13.

SOE and private-enterprise constructors’ response sensitivity coefficients.

Figure 12 simulates the constructor strategy evolution under a step size of 0.125 for λ3 for both SOE and private enterprises. When λ3 rises to 2.375 for SOE constructors and 2.875 for private constructors, the constructor switches rapidly from “not adopt” to “adopt”, passing through the strategy adjustment range, the fast convergence range, and the slow convergence range. Higher λ3 values accelerate the shift. The corresponding thresholds for owners are 1.875 for SOEs and 2.125 for private enterprises. The results indicate that SOEs always sit in the lower loss-aversion interval, showin markedly higher tolerance for potential losses than private enterprises.

The figure simulates the constructor strategy evolution under a step size of 0.02 for α3 and β3 for both SOE and private enterprises. When α3 and β3 reach 0.74 and 0.82 for SOE constructors and 0.88 and 0.94 for private constructors, the constructor switches rapidly from “not adopt” to “adopt”, passing through the strategy adjustment range, the fast convergence range, and the slow convergence range. Higher α3 and β3 values accelerate the shift. The corresponding thresholds for owners are 0.70 and 0.78 for SOEs and 0.84 and 0.90 for private enterprises. The results indicate that government promotion campaigns that emphasize potential economic losses and unsustainable development from non-adoption can nudge enterprises toward proactive strategies, an approach that is particularly effective for private enterprises.

5.4.6. Parameter Sensitivity

The preceding analyses show that incentives, penalties, costs, and risk-preference coefficients all shape enterprise strategy choices; during parameter adjustment, each strategy transition passes through the adjustment range, the fast convergence range, and the slow convergence range. Because the parameters operate at different scales, a direct quantitative comparison of sensitivity is not feasible. We therefore extracted the underlying MATLAB data to obtain a unified sensitivity metric for every parameter.

As illustrated in Figure 7, Curves 2 and 3 for the SOE owners Igo correspond to values of 32.4 and 34, converging to unity at t = 29.98 and 6.69; thus, each additional CNY 1 million accelerates convergence by 14.556 units in the fast convergence range, whereas the subsequent slow-range values are 1.763 and 0.919. This metric gauges parameter responsiveness under equal budget injections: the higher the value, the greater the sensitivity. All parameter sensitivities are summarized in Table 6. Calculations show that sensitivities in the fast convergence range exceed those in the slow range by at least sevenfold, consistent with Table 5.

Table 6.

Parameter sensitivity.

Table 5 further reveals that, within the fast convergence range, the sensitivity ranking for SOE owners is Igo > Pgo > Con > Cof, while for constructors it is Ccn > Igc > Pgc > Ccf. For private enterprises, the owner ranking is Cof > Con > Igo > Pgo, and the constructor ranking is Ccf > Igc > Ccn > Pgc. When the system moves from the fast to the slow range, sensitivities drop sharply (e.g., Igo falls from 14.556 to 1.763 and 0.919), yet the sensitivity order remains intact. These rankings provide an intuitive guide to the relative influence of each parameter on strategy choice, enabling the government to set policy priorities rationally.

6. Discussion and Policy Implications

Based on the foregoing analysis and numerical simulations, this section proposes a promotion mechanism and policy recommendations for the application of GCTs within the Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Circle.

6.1. Promotion Mechanisms of the GCTs Industry

Previous sections have examined the conditions necessary for transitioning among the following stages: government-activated market E2(1, 0, 0), government-led market E8(1, 1, 1), and government-withdrawn market E7(0, 1, 1). The role of various parameters in facilitating these transitions has also been explored. Building on these insights, a structured promotion mechanism is proposed, as illustrated in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Promotion Mechanism for GCTs Adoption E2(1, 1, 1) → E7(0, 1, 1): After this development stage, the technologies achieve economies of scale, industrial chains mature, costs fall, and the labor pool expands; enterprises can profit without incentives or subsidies. Government should now phase out direct carrots and sticks, retain only arms-length oversight, and continuously refine laws, regulations, and monitoring systems to deter opportunism and maintain a healthy market environment.

E2(1, 0, 0) → E7(0, 1, 1): In the initial promotion phase, GCTs lack economies of scale, supply chains are underdeveloped, R and D and purchase costs are high, and skilled talent is scarce. Because traditional methods still guarantee profits, the new technology becomes an extra burden that pushes profits into the red. To curb environmental risk and deliver high-quality development, the government must take the lead in promoting the technology. Research shows it can use incentives, penalties, restrictions on future expansion, and cost-cutting measures to mobilize both SOE and private enterprises. Interventions must be tailored: SOE owners should receive incentive-first packages—land discounts, tax breaks, cash subsidies, extra floor-area allowances, and preferential loans—while SOE constructors need cost reduction first, topped up with subsidies covering part of the incremental cost, and help in training a skilled workforce. For private enterprises, the focus must be on market share, supported by reserved “green-construction lots” in public procurement so that their technology spending translates into visible market gains. Meanwhile, the government can intensify publicity through demonstration-project roadshows and industry-association training, stressing the downside of non-adoption, such as tender-score deductions and blacklisting for excess carbon emissions. Any policy adjustment passes through an adjustment range, a fast convergence range, and a slow convergence range; after implementation government must track market response to keep enterprise strategies inside the fast convergence range and maximize fiscal efficiency.

6.2. Policy Implications

GCTs are vital for advancing the construction industry’s sustainable development. Based on the study findings, we propose the following policy recommendations:

First, establish a dynamic market-feedback mechanism. Parameter sensitivity is directly linked to the evolutionary range. Before the adjustment range, funding has little effect and may even encourage rent-seeking behavior aimed at obtaining subsidies without genuine adoption. In the slow range, the same injection produces markedly weaker effects than in the fast range. A digital platform should therefore be built to collect and analyze real-time data on green-construction uptake, with particular attention to the growth rate of applications before and after policy changes. When this rate drops by more than sevenfold, the relevant parameter is moving from the fast to the slow range, and policy should be redirected toward other levers.

Second, introduce a dynamic incentive–penalty mechanism. Rewards and sanctions stimulate technology uptake and strategy adjustment passes through the adjustment, fast and slow ranges; hence, incentives and penalties must be varied to match each developmental stage. Begin by ensuring a critical mass of early adopters, then intensify stimuli so that remaining players move rapidly to adoption and scale is achieved, finally tapering support and leaving uptake to market forces. The mechanism must be differentiated: SOEs can receive large-project matching subsidies, while private enterprises should be offered small, fast disbursements and tender-score or loan-rate links that adjust in real time.

Third, create a government-procurement set-aside. Private enterprises are more concerned than SOEs with future growth and market share. To secure sustainable private investment in green construction, BIM, and other new technologies, public tenders should institutionalize set-asides for private firms and replace asset-size thresholds with technology-capability scores at the pre-qualification stage, preventing elimination on the basis of net assets or past performance.

Finally, implement a publicity and education mechanism. Enterprises exhibit loss aversion; regular policy briefings and case studies that highlight the impact of non-adoption on future profitability and market survival can shift behaviour away from carbon-intensive habits. Because constructors are highly cost-sensitive, diversified incentives should be complemented by public–private–academic partnerships that train industry talent and substantially reduce the cost of applying new technologies.

7. Conclusions

During the high-quality development and transformation of the construction industry in the Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Circle, the strategic choices of government, owners, and constructors shape the adoption rate of GCTs. Previous studies have not offered a full account of stakeholder decision-making behaviors and influencing factors inside this region, nor have they incorporated bounded rationality and risk preferences. Drawing on evolutionary game and prospect theories, we build a tripartite model that embeds government, owners, and constructors; theoretical analysis, a case study, and numerical simulation are then combined to reveal how SOEs and private stakeholders select strategies and respond to parameter changes across successive promotion phases. The main findings are as follows:

The life cycle of GCTs can be partitioned into the government-activated market phase E2(1, 0, 0), the government-led market phase E8(1, 1, 1) and the government withdrawn market phase E7(0, 1, 1). By tuning parameter values, the government can shift equilibrium conditions and steer the evolutionary path along E2(1, 0, 0) → E8(1, 1, 1) → E7(0, 1, 1), thereby achieving full marketisation.

Throughout this evolutionary process, incentives, penalties, restrictions on future expansion, cost reduction initiatives, and risk preferences all significantly influence enterprise strategy choices. As parameters vary, strategies traverse the strategy adjustment range, the fast convergence range, and the slow convergence range; government funds attain their highest efficiency inside the fast convergence range.

The stimulative effects of the above instruments differ between SOEs and private enterprises. Inside the fast convergence range, the parameter sensitivity ranking for SOE owners is Igo > Pgo > Con > Cof, while for constructors it is Ccn > Igc > Pgc > Ccf; for private owners, the ranking is Cof > Con > Igo > Pgo, and for private constructors it is Ccf > Igc > Ccn > Pgc. Consequently, owners, especially SOE owners, should be approached with an incentive first package supplemented by other measures, whereas constructors require a cost reduction first strategy backed by auxiliary incentives; private enterprises additionally need guarantees on market share protection.

Based on these conclusions, we propose that the government establish (i) a dynamic market feedback mechanism, (ii) a dynamic incentive penalty mechanism, (iii) a government procurement set-aside mechanism, and (iv) a publicity and education mechanism, so as to heighten market responsiveness, improve resource allocation, and raise the efficiency of public spending. The analysis, however, covers only the principal actors and key drivers; moreover, the evolutionary game framework does not capture social network effects on interaction opportunities. Future research will therefore introduce additional stakeholders and influencing factors through network evolutionary game modelling, bringing the analysis closer to real-world complexity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and N.X.; data curation, J.L. and Q.L.; formal analysis, J.L. and Q.L.; funding acquisition, J.L.; investigation, H.Z. and N.X.; methodology, Q.L.; software, J.L.; supervision, N.X. and Q.L.; validation, Q.L., J.L. and H.Z.; visualization, H.Z.; writing-original draft, J.L.; writing-review and editing, N.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Tuojiang River Basin High-quality Development Research Center, grant number XD024009, Research on the Internal Logic and Practical Pathways of New Quality Productive Forces Driving High-Quality Development in the Construction Industry along the Tuojiang River Basin.

Data Availability Statement

The case analysis data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviation is used in this manuscript:

| GCTs | Green Construction Technologies |

References

- Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction 2024/2025. Available online: https://globalabc.org/sites/default/files/2025-03/Global-Status-Report-2024_2025.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Dinesh, S.; Kirubakaran, K.; Kumar Ranjith, G. A Review on Green Energy and Technology in Construction. IJRASET 2020, 8, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.J.; Wang, N.; Zhu, T.; Xiao, X.W. Research on Development Strategy of Green Construction Technologies in China Based on Carbon Peak and Carbon Neutrality Goals. Constr. Technol. 2024, 53, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Deng, X.; Qi, Y. Factors Driving Coordinated Development of Urban Green Economy: An Empirical Evidence from the Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Circle. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key Points for Promoting the Development of Intelligent Construction and Prefabricated Building in the Province in 2025. Available online: https://jst.sc.gov.cn/scjst/otherDocument/2025/3/3/668f9b09e8b6420599c294cbefa0d645.shtml (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Yuan, M.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, S.; Luo, X. How to Promote the Sustainable Development of Prefabricated Residential Buildings in China: A Tripartite Evolutionary Game Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 349, 131423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.W. State and Development Strategy for Green Construction. Constr. Technol. 2018, 47, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.J.; Liu, Y.C.; Wang, N.; Xiao, X.W. Experience and Enlightenment of Green Construction Development in Foreign Countries. Green Constr. Intell. Build. 2024, 4, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Navaratnam, S.; Satheeskumar, A.; Zhang, G.; Nguyen, K.; Venkatesan, S.; Poologanathan, K. The Challenges Confronting the Growth of Sustainable Prefabricated Building Construction in Australia: Construction Industry Views. J. Build. Eng 2022, 48, 103935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.J.; Oyekan, O.; Stergioulas, L.; Griffin, D. Utilizing Industry 4.0 on the Construction Site: Challenges and Opportunities. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform 2021, 17, 746–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, J.M.D.; Oyedele, L.; Ajayi, A.; Akanbi, L.; Akinade, O.; Bilal, M.; Owolabi, H. Robotics and Automated Systems in Construction: Understanding Industry-Specific Challenges for Adoption. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 26, 100868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.C.; Zhu, T.; Lu, Y.J.; Zhang, W.J. China’s Green Construction: Development Concepts, Leading Directions and Technological Innovation. Strateg. Study CAE 2024, 26, 190–207. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Q.H. Thinking on Green Development and Intelligent Construction. Archit. Technol. 2022, 53, 951–952. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Ding, L.Y. Development of Key Domain-Relevant Technologies for Smart Construction in China. Strateg. Study CAE 2021, 23, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.A.; Zhang, A.M.; Xue, Y.Q.; Zhang, C.J.; Ma, C.; Zhao, P. Research on Green Construction Development Path Under the ”Dual Carbon” Strategy. Constr. Technol. 2022, 23, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A.P.C.; Darko, A.; Ameyaw, E.E. Strategies for Promoting Green Building Technologies Adoption in the Construction Industry-An International Study. Sustainability 2017, 9, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.J.; Yang, X.; Li, P.X.; Xiao, X.W. A Meta-analysis of Embodied Carbon Emissions of Prefabricated Buildings. Build. Sci. 2024, 40, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Chen, H.; Ao, Y.; Liao, F. Spatiotemporal Differentiation and Influencing Factors of Green Technology Innovation Efficiency in the Construction Industry: A Case Study of Chengdu-Chongqing Urban Agglomeration. Buildings 2023, 13, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, K.; Jing, J.L. Research on Construction Cost Control of Urban Rail Transit Projects Based on BIM. Constr. Econ. 2022, 43, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Darko, A.; Chan, A.P.C.; Ameyaw, E.E.; He, B.-J.; Olanipekun, A.O. Examining Issues Influencing Green Building Technologies Adoption: The United States Green Building Experts′ Perspectives. Energy Build. 2017, 144, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.-G.; Ngo, J.; Teo, J.Z.K. Challenges and Strategies for the Adoption of Smart Technologies in the Construction Industry: The Case of Singapore. J. Manag. Eng. 2022, 38, 05021014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, D.G.J.; Perera, S.; Osei-Kyei, R.; Rashidi, M.; Famakinwa, T.; Bamdad, K. Drivers for Digital Twin Adoption in the Construction Industry: A Systematic Literature Review. Buildings 2022, 12, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, H.; An, Y.; Bai, H.; Shi, J. Intergovernmental Collaborative Governance of Emergency Response Logistics: An Evolutionary Game Study. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 705–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Hu, Z.-H. Using Evolutionary Game Theory to Study Governments and Manufacturers’ Behavioral Strategies under Various Carbon Taxes and Subsidies. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 201, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Yu, X.; Chen, X.; Song, M. Research on Stability of Major Engineering Technology Innovation Consortia Based on Evolutionary Game Theory. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 186, 109734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jin, Y.; Meng, Q.; Chong, H.-Y. Evolutionary Game Analysis of the Opportunistic Behaviors in PPP Projects Using Whole-Process Engineering Consulting. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2024, 30, 04024021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Ren, S.; Wang, L.; Huang, Y. Evolutionary Game Analysis of Collaborative Application of BIM Platform from the Perspective of Value Co-Creation. ECAM 2024, 32, 4458–4474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Xiong, F.; Hu, Q.; Liu, R.; Li, S. Incentive Mechanism of BIM Application in Prefabricated Buildings Based on Evolutionary Game Analysis. Buildings 2023, 13, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Gao, X.; Hua, C.; Gong, S.; Yue, A. Evolutionary Process of Promoting Green Building Technologies Adoption in China: A Perspective of Government. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.