Abstract

The Songliao River Basin, as a core area of multicultural integration in Northeast China, still lacks systematic research on the spatial distribution of religious sites and their influencing factors. This study integrates spatial pattern analysis methods (kernel density, standard deviation ellipse, imbalance index) and spatial econometric models (spatial error model, geographically weighted regression model) to explore the spatial distribution characteristics of 1288 religious sites in the basin and the influencing mechanisms of natural, socio-economic, and cultural factors. Results: (1) Religious sites in the basin show a clustered distribution of “higher density in the south than the north, one main cluster and two sub-cores”, with a northeast–southwest trend and poor balance at the prefectural-city scale. (2) Cultural factors are the core driver; cultural memory and social capital in traditional villages promote the agglomeration of religious sites and shape the “one village, multiple temples” pattern. Intangible Cultural Heritage, Major Historical and Cultural Sites Protected at the National Level, and religious sites form a tripartite symbiotic spatial relationship of “cultural practice—spatial carrier—institutional identity”; natural factors lay the basic pattern of spatial distribution. (3) Policy factors have a significant impact: A-rated Tourist Attractions and Performing Arts Venues show a positive effect, while museums exhibit spatial inhibition due to functional competition. (4) Economic, Population, and Transportation factors had no statistically significant effects, indicating that their spatial distribution is driven primarily by endogenous cultural mechanisms rather than external economic drivers. This study fills the gap in research on the spatial distribution of religious sites in Northeast China. By integrating multiple methods, a quantitative demonstration of the coupling mechanism of multiple factors was conducted, providing scientific support for religious cultural heritage protection policies and sustainable development strategies amid rapid urbanization.

1. Introduction

Religious sites, as spaces where religious adherents collectively hold religious rituals, religious education, faith exchanges, and other religious activities, not only act as carriers of cultural dissemination and faith practices but also influence community structure and spatial order [1]. The preservation and development of religious sites play a critical role in fostering a harmonious and stable social environment, safeguarding China’s religious cultural heritage, and promoting the sustainable development of cultural diversity. However, rapid urban development has exerted significant impacts on the form, function, and significance of religious sites [1].

Within geography, religion has emerged as a significant research topic, developing into a specialized sub-discipline: the geography of religion [2,3,4]. Current research is divided into three aspects: First, early foundational studies on the basic framework, origins of the geography of religion. For instance, Sopher established the fundamental research framework for the geography of religion [5], covering core topics such as the origins, diffusion, and spatial relationships of religions; Peach emphasized an empirical research orientation, which remains the mainstream in this field [6]. Second, the spatial evolution of religious sites. For example, TANG Yifan et al. explored the spatial patterns and diffusion models of China’s four major religions from temporal and spatial dimensions, revealing developmental disparities across different types of cities [7]; Orlando Woods notes that religious sites exhibit different spatial distribution patterns amid urban development [8]. Third, factors influencing the spatial distribution characteristics of religious sites are explored. For instance, CHEN Junzi et al. identified historical economic development levels, socio-cultural environments, and governmental religious policies as key factors influencing the spatial distribution of religious architectural heritage [9]; XUE Ximing et al. found that the spatial distribution of Christian churches in Guangzhou was mainly influenced by transportation and demographic factors [10]; In summary, the factors and formation mechanisms influencing the spatial distribution characteristics of religious sites are highly complex, and studies in different geographical contexts may lead to different conclusions. Currently, some domestic scholars have proposed exploring the impacts of natural environments, socio-economic factors, and cultural development on the spatial distribution of religious sites from perspectives of prefectural-level cities [11], provincial-level regions [12,13,14], and specific zones [15], bringing a diversified trend to research. However, some limitations remain. On one hand, many studies examine the factors affecting the spatial distribution of religious sites separately, which hinders prevents comprehensive exploration of their partial distribution characteristics and influence mechanisms. On the other hand, due to factors including historical and cultural foundations, economic development priorities, and data availability [16], domestic research has mainly focused on southeastern coastal China and northwestern regions, while studies on the northeastern region remain relatively limited [17,18]. This study focuses on northeastern China, aiming to analyze the spatial distribution characteristics and influencing mechanisms of religious sites, thereby providing a valuable supplement to domestic research on religious sites.

The Songliao River Basin broadly refers to northeastern China, a region that historically served as the birthplace or key area of dynasties including the Liao, Jin, and Qing [19]. Amid the background of dynastic policies and colonial aggression, diverse regional and ethnic cultures collided and merged in the Songliao River Basin, fostering the formation of a polytheistic cultural phenomenon featuring Han Buddhism, Taoism, Shamanism, and other religious traditions [20,21]. Focusing on religious sites within the Songliao River Basin, this study employs Spatial Error Model (SEM) and Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) to analyze the associations between their macroscopic spatial distribution characteristics and natural environmental, socio-economic, and cultural factors, with the objective of clarifying the underlying influencing mechanisms and providing insights for the preservation and adaptive transformation of these sites.

2. Study Area, Data Sources, and Research Methods

2.1. Study Area

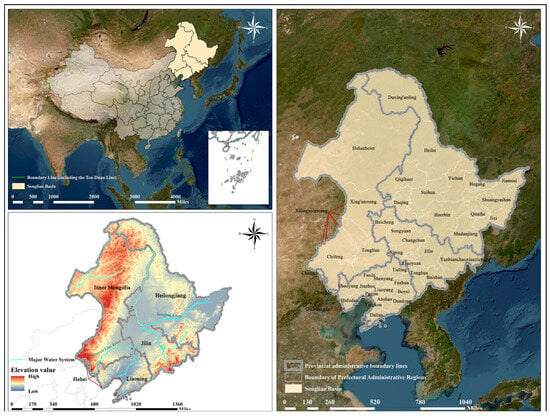

The Songliao River Basin is one of the nine major river basins in China, located in its northeastern region [22]. The administrative divisions of the basin include Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang provinces, the four eastern leagues (prefecture-level cities) of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, and a portion of Chengde City in Hebei Province. The topography is mainly plains and mountains, bordered by the Bohai Sea and the Yellow Sea to the south, with the Liao River and Songhua River systems flowing through the basin (Figure 1). Its population includes 43 ethnic minorities including the Man, Mongolian, and Korean. Its unique geographical environment and diverse ethnic minority cultures have fostered abundant religious cultures [21]. This study focuses on 1288 registered religious sites in the Songliao River Basin, including temples, Taoist temples, mosques, churches, and other fixed religious venues. Of these, 1143 are Buddhist and 145 are Taoist.

Figure 1.

Study Area (Note: Created based on the standard map (Approval No. GS(2024)0650) from the National Platform for Common Geospatial Information Services, with no modifications to the base map. The same applies to the figures below.).

2.2. Data Sources

In 2004, the government for the first time included religious sites in the economic census and issued the Regulations on Religious Affairs. With the gradual improvement of the system, the government has tightened its management of religious affairs, and no religious census data has been released to the public since then. To ensure historical benchmark value and institutional authority, the religious sites in this study are based on those registered with the State Administration for Religious Affairs that year. Since the kernel density of religious sites reflects their spatial distribution characteristics more accurately than simple counts [11], the average kernel density per grid unit was used as the dependent variable (Y). Using the sites’ names and addresses, their geographic coordinates were obtained via Amap, and a vector point database of religious sites in the Songliao River Basin was constructed.

Regarding the independent variables, the spatial distribution characteristics of religious sites in the Songliao River Basin result from the interaction of multiple factors. This study focuses on 2023. Based on a theoretical analysis framework, it integrates domestic and international literature on religious heritage and considers the quantifiability of indicators [23,24,25,26], After excluding multicollinearity among related variables, the following influencing factors were selected as independent variables (Table 1). Based on prior experience and multiple experiments in ArcGIS 10.8.1, the Fishnet Tool yielded more accurate analytical results, with each grid assigned a variable value.

Table 1.

Independent variables influencing the spatial distribution of religious sites in the Songliao River Basin.

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. Kernel Density (KDE)

Point data of religious sites cannot be directly used as continuous dependent variables for regression analysis. As a mature non-parametric statistical method, KDE can convert such point data into a continuous density surface, accurately depicting the spatial distribution and agglomeration of religious sites in the basin [27]. Secondly, compared with count statistics, Kernel density can effectively reduce the interference of randomness in individual site location on overall analysis results, and improve the stability and representativeness of the dependent variable. A higher kernel density value indicates a greater degree of agglomeration, while a lower value indicates a lower degree. The calculation formula is as follows [28]:

is the total count of religious sites; refers to the bandwidth, with > 0; denotes the distance between the target point and the event point . is the kernel density function. It exhibits characteristics such as infinite support and excellent smoothness, making it well-suited for analyzing irregularly distributed religious sites [29]. This method also has inherent limitations. Its results are highly sensitive to the choice of bandwidth ; an excessively small bandwidth tends to fragment the density surface, making it difficult to identify agglomeration patterns; an excessively large bandwidth will cause over-smoothing, masking actual local agglomeration characteristics.

2.3.2. Standard Deviational Ellipse (SDE)

KDE alone is insufficient to comprehensively characterize where religious sites in the basin cluster and whether they cluster. SDE can quantitatively interpret the spatial characteristics of these sites from a global perspective, including centrality, directionality, and distribution pattern. The center of the ellipse indicates the distribution position of religious sites in two-dimensional space, the azimuth angle their distribution trend direction, and the long axis denotes the dispersion degree of religious sites along that direction. The calculation formula is as follows [30,31]:

, represent the central coordinates of the ellipse; , denote the coordinate parameters of religious sites inside the basin. , indicate the geometric center of the spatial distribution characteristics of religious sites in the Songliao River Basin. Eccentricity, which measures an ellipse’s deviation from a perfect circle (i.e., its “flatness”), is calculated from the semi-major axis and semi-minor axis, with a value range of (0,1). When Eccentricity is close to 0, it indicates that the dispersion of data points from the mean center of the ellipse to the surroundings is relatively balanced, with no dominant expansion direction. Conversely, when Eccentricity is close to 1, the data distribution shows strong directionality.

2.3.3. Imbalance Index (II)

KDE and SDE characterize the agglomeration locations and patterns of religious sites’ spatial distribution, but cannot directly provide a single, clear numerical value to indicate how imbalanced their distribution is across prefecture-level cities. This study introduces the II to reflect the equilibrium degree of religious site distribution in the Songliao River Basin. It calculates the II (S) using the concentration index formula derived from the Lorenz curve [32]:

represents the number of prefecture-level units in the Songliao River Basin, denotes the proportional share of the region. is within the range of [0, 1], and a larger value indicates a more uneven distribution.

2.3.4. Spatial Econometric Models

If spatial autocorrelation is statistically significant, using a multiple linear regression model to identify factors influencing the spatial distribution characteristics of religious sites in the Songliao River Basin may lead to discrepancies in regression coefficients and goodness-of-fit [33], thus warranting the use of Spatial Econometric Models. Widely adopted spatial econometric models mainly comprise the Spatial Error Model (SEM) and the Spatial Lag Model (SLM). The formulas are as follows:

In the SEM formula, denotes the spatially autocorrelated error component; denotes the spatial error coefficient that measures the spatial dependence of the error term; is the spatial lag of the error term, functions as an independent and identically distributed stochastic error term; In the SLM formula, is the autoregressive coefficient; stands for the dependent variable’s spatial lag; corresponds to the regression coefficient of the explanatory variable; serves as a random error component following a normal distribution. In both formulas, represents the spatial weight matrix, which describes the spatial adjacency relationships between research units. This study constructed the matrix based on the first-order adjacency under the Queen criterion and performed standardization on it. is the dependent variable; is the independent variable.

This study calculated the global spatial autocorrelation index via GeoDa 1.22.012 and ArcGIS 10.8.1, yielding a Moran’s I value of 0.973543 that passed the significance test at the 1% level. This confirms significant spatial agglomeration of religious sites in the Basin, justifying the adoption of spatial econometric models for estimation. To avoid result bias caused by interactions between indicators, multiple linear regression was used to conduct multicollinearity diagnostics on influencing factors. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) of all variables was less than 5, and the model’s R2 reached 66.3%, indicating no multicollinearity among variables. Diagnostic results of spatial dependence in OLS regression residuals (Table 2) show that the p-value of the Moran’s I (error) index passed the significance test, indicating spatial autocorrelation in the regression residuals. LM-Error, LM-Lag, Robust LM -Error and Robust LM-Lag all passed the significance test, necessitating a comparison of the results of spatial econometric models [34].

Table 2.

Diagnostic results of spatial dependence in OLS regression residuals.

2.3.5. Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR)

The formation of spatial distribution of religious sites in the basin often exhibits both spatial heterogeneity [35] and spatial dependence [36], and spatial econometric models can conduct global analysis of the influencing factors. This study introduces the Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) model to reveal the local spatial variation characteristics of the impact of independent variables on the dependent variable, thereby clarifying the complex relationships between the spatial distribution of religious sites in the basin and their influencing factors. The formula is as follows:

denotes the central geographic coordinates of the i-th study object; represents the intercept term corresponding to the spatial coordinates of the i-th unit; is the local regression coefficient of the k-th independent variable at the coordinate . This study employs a fishing net tool to assign values to variables for enhanced analytical precision. After removing sparsely sampled grids, a total of 1792 research units were obtained.

Calculations of the GWR model’s indicators yield a model fit R2 of 89.1% (Table 3), which is combined with the known data from previous sections. It outperforms the results of traditional linear regression models, confirming that the GWR model has better goodness-of-fit and can effectively explain the impacts of independent variables.

Table 3.

GWR model test results.

3. Research Results and Analysis

3.1. Spatial Distribution Density Characteristics of Religious Sites

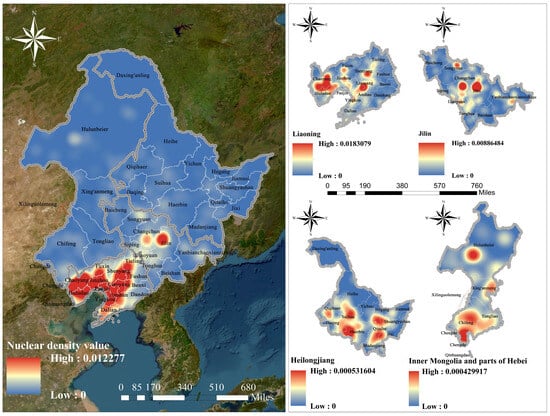

The kernel density of religious sites in the Songliao River Basin shows a spatial distribution pattern of “higher values in the south and lower in the north, with one cluster and two cores.” The southern region presents a clustered agglomeration form, the central agglomeration area is composed of one main core and one sub-core, with the remaining areas showing a scattered distribution (Figure 2). In terms of provinces within the basin, the clustered areas are concentrated in Liaoning Province. Within the province, the kernel density of religious sites shows a “three-core” spatial distribution along the Chaoyang-Liaoyang-Shenyang corridor, radiating to surrounding areas and forming a W-shaped clustered pattern across the province As political military and religious-cultural centers in ancient and modern times, these three regions have shaped the dense distribution of religious sites in the province through their historical centripetal force. The basin’s central core area is concentrated in Jilin Province. A high-density “primary core” has formed at the junction of northwestern Jilin City and Changchun City, while a medium-high density “secondary core” exists in south-central Changchun. This pattern gradually radiates to northwestern Liaoyang, Tonghua, and southeastern Siping, exhibiting distinct hierarchical characteristics. This is related to population movements of southward migration and northward relocation since the late Qing Dynasty. Religious site density in other provinces and cities of the basin is low, contrasting sharply with the central-southern regions.

Figure 2.

Kernel Density of Religious Sites in the Songliao River Basin.

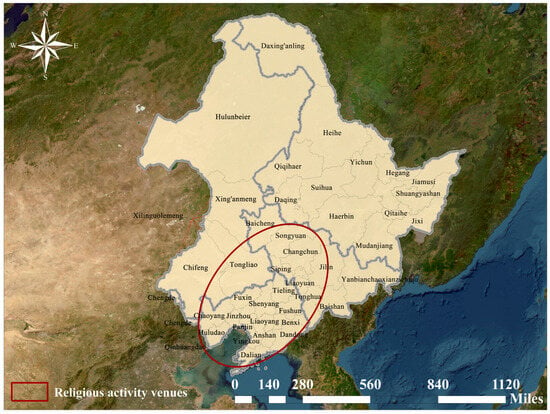

3.2. Spatial Distribution Directional Characteristics of Religious Sites

According to the SDE analysis (Figure 3), the rotation angle of religious sites is 38.47°, with an overall northeast–southwest distribution trend. Religious sites in basin are mainly concentrated within an elliptical area centered at 42.252° N, 123.0° E and with an ellipticity of 0.36, This area covers 530 religious sites, including those in Liaoning Province and central-western Jilin Province. It indicates that religious sites in the Songliao Basin have significantly higher agglomeration in the southwest-northeast direction than the perpendicular one, further confirming this direction as the main distribution axis, along which their spatial diffusion in the Basin mainly unfolds.

Figure 3.

SDE Distribution of Religious Sites in the Songliao River Basin.

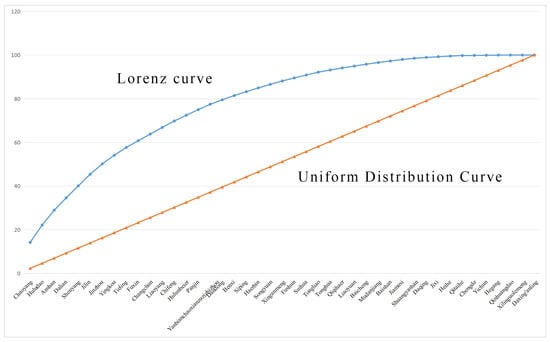

3.3. Spatial Distribution Equilibrium Characteristics of Religious Sites

According to the Lorenz curve generated from statistical data (Figure 4), the geographic concentration index was calculated as G = 23.22. If the 1288 religious sites in the basin were evenly distributed across 43 prefecture-level units, then G0 = 15.25. With G > G0, this indicates a clustered distribution pattern of religious sites within the basin. The imbalance index S = 0.56 demonstrates a highly uneven distribution of religious sites at the prefectural level within the basin. Overall, Liaoning and Jilin provinces within the Songliao River Basin account for nearly 80% of the total number of religious sites. Seven prefectural-level cities—Chaoyang, Huludao, Anshan, Dalian, Shenyang, Jilin City, and Jinzhou—contain approximately 50% of all religious sites, while prefectural-level cities in other provinces account for relatively lower proportions.

Figure 4.

Lorenz Curve of Religious Sites in Prefectural-Level Cities within it.

3.4. Influencing Factors of the Spatial Distribution of Religious Sites

3.4.1. Results and Analysis of Spatial Econometric Models

- Selection of Spatial Econometric Models

Based on all statistical metrics of Spatial Econometric Models (Table 4), the SEM has higher for goodness-of-fit (R2) and log-likelihood values, as well as lower Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Schwarz Criterion (SC) values. Thus, SEM was selected as the optimal model for analysis [37].

Table 4.

Statistics of SEM and SLM.

- 2.

- Results of Spatial Econometric Models

Basin-wide results indicate (Table 5) that cultural factors are the most important factor affecting the spatial distribution of religious sites in the basin. Among these, traditional villages (X13) demonstrated a significantly positive correlation with the spatial distribution of religious sites and contribute the most. Intangible Cultural Heritage (X12) and NLMHCS (X14) also show significantly positive correlations with the distribution and feature relatively high coefficients. From a basin-wide perspective, traditional villages are spatial carriers of accumulated cultural memory and social capital in historical processes. During the migration wave to northeastern China in the Qing Dynasty, numerous ethnic minority groups gathered in the basin, and building temples became a key means for these immigrant communities to anchor and materialize cultural memories while reconstructing their spiritual homelands in foreign lands. Furthermore, drawing on Paul Wheatley’s social capital theory [38], the dense social networks within traditional villages—rooted in geographical and kinship ties—significantly reduced the costs of fundraising, coordination, and mobilization during temple construction. Through “bonding capital” [39] temples unite clans, maintain identity, and use “bridging capital” [39] to mediate disputes and organize inter-village collective activities. The embedded cultural memory and social capital within traditional villages interact and drive each other; when gained a certain economic foundation, they promoted the large-scale construction of religious sites around these villages and the formation of spatial agglomerations. Furthermore, multiple religious beliefs including Han Buddhism and Taoism have intermingled and coexisted in the basin. During this process, some of the resulting religious sites were designated as NLMHCS due to their profound historical and artistic value. Meanwhile, intangible cultural heritage such as Buddhist temple fairs and Taoist rituals—serving as “living” cultural practices—are highly dependent on religious sites as their specific physical spatial carriers. These religious sites bearing such intangible cultural heritage are also designated as NLMHCS due to their historical and cultural value. This has formed a triadic symbiotic relationship in the basin, where cultural practices provide endogenous motivation, physical spatial carriers lay the value foundation, and special identities drive spatial restructuring.

Table 5.

Evaluation Results of SEM for Influencing Factors of Religious Sites in the Songliao River Basin.

Among natural factors, elevation (X1) and temperature (X3) have significantly negative correlations with the spatial distribution of religious sites in the basin, while slope (X2) has a positive correlation. Rivers exert a certain positive influence on them but with a weak effect. These findings align with existing research [40], while NDVI (X5) showed no correlation with them. Religious sites in the basin prefer gentle slopes with lower construction costs and better accessibility. Slope can be interpreted as an adaptive choice in the spatial competition between religious sites and secular activities. Within the basin, prime land is typically occupied by various economic activities, so religious sites are built on suboptimal gentle slopes. This approach avoids both high-flood-risk zones and core areas of secular spatial competition, while also managing natural risks. Consequently, religious sites in the basin are predominantly constructed on gentle slopes with lower elevations and mild climates. Furthermore, in Fengshui theory, rivers are regarded as “auspicious sites” [41], so gentle slopes along rivers have thus become ideal locations for religious sites. The global result of NDVI (X5) may be attributed to the interplay of natural and cultural factors in the basin, which forms a population pattern of “denser in the south and sparser in the north, higher internally and lower externally”. As a cultural phenomenon, the spread and development of religion are linked to population migration routes and settlement distribution, while cultural inheritance and historical context also play important roles in shaping its spatial distribution. Under the influence of multiple factors, their weight is far higher than that of NDVI.

Among socio-economic factors, A-rated tourist attractions (X10) and performing arts venues (X11) promote the spatial distribution of religious sites in the basin, while higher kernel density values of museums (X9) squeeze the development space of religious sites to a certain extent. Furthermore, GDP (X6), population density (X7), and road network density (X8) have no significant impact on the spatial distribution of religious sites. As a key foundation for religious tourism development, A-rated tourist attractions generate resource spillover effects on surrounding religious sites, driving their infrastructure construction and development condition improvement, and enhancing the appeal of nearby religious tourism. Performing arts venues serve as physical carriers of religious culture spread. Performing arts venues, often closely linked to religious cultural activities, boost the basin’s cultural attributes with policy support, promote the spread and directional flow of religious culture, and thus drive the spatial agglomeration of religious sites within the basin. Meanwhile, religious sites are used for prayer, seeking spiritual peace, or participating in religious activities. In contrast, the “museumification” process makes museums focus on exhibition, research, and educational functions, which weakens the sacred attributes of religious items and leads to different needs of service groups and distinct “cultural niches” for the two. The remaining variables showed no correlation, indicating that the spatial distribution of religious sites in the basin is more driven by “endogenous” mechanisms rather than external macroeconomic forces. This means that the construction of these sites is not fully market-oriented or commercialized.

3.4.2. Results and Analysis of Geographically Weighted Regression Model

As shown in Table 6, the ranking of influencing factors based on the absolute values of regression coefficients (in descending order) is: traditional villages (X13) > intangible cultural heritage (X12) > museums (X9) > NLMHCS (X14) > A-rated tourist attractions (X10) > performing arts venues (X11) > slope (X2) > temperature (X3) > GDP (X6) > elevation (X1) > river density (X4) > NDVI (X5) > population density (X7) > road network density (X8). Based on the above SEM results, the GWR model is used to further reveal the local spatial variation characteristics of the impact of independent variables on the dependent variable.

Table 6.

Statistical Results of the GWR Model for Influencing Factors.

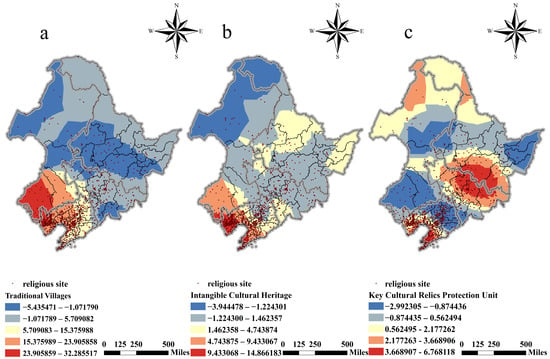

- Cultural Factors

The regression coefficient of traditional villages (X13) decreases from southwest to northeast, showing an overall positive effect and exerting the strongest influence on the spatial distribution of religious sites in the basin among all independent variables. Figure 5a shows that traditional villages are mainly distributed in the southwestern part of the basin, where multi-ethnic culture is strong. Religious sites act as public platforms for residents to hold religious rituals, exchange information, and engage in emotional interactions, thus forming a “one village, multiple temples” in the basin’s southwestern region.

Figure 5.

Spatial heterogeneity of cultural factors. (a) Spatial distribution of regression coefficients for traditional villages; (b) Spatial distribution of regression coefficients for intangible cultural heritage; (c) Spatial distribution of regression coefficients for NLMHCS.

The regression coefficient of intangible cultural heritage (X12) has high values concentrated in the southern part of the basin. Figure 5b shows that it generally decreases from southwest to northeast, with strong positive correlations in Dalian, Huludao, and Chaoyang cities. These areas lie in the core zone of the “Liaoxi Corridor” within the basin, acting as a cultural corridor connecting the Central Plains and northeastern China. Boasting a historical heritage of multicultural integration, they bring more folk cultures and religious beliefs to religious sites, and many religious sites rely on intangible cultural heritage to boost economic development.

The regression coefficients of key cultural relics protection units (X14) presents a spatial structure of “multi-center ring-shaped decline”. Figure 5c shows that multiple influence centers are formed by “Changchun-Jilin-Harbin-Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture-Mudanjiang” and “Dalian-Yingkou”, which are basically consistent with the spatial distribution of religious sites. NLMHCS in these areas are mainly ancient buildings and ancient sites, which are linked to historical economic and trade factors.

- 2.

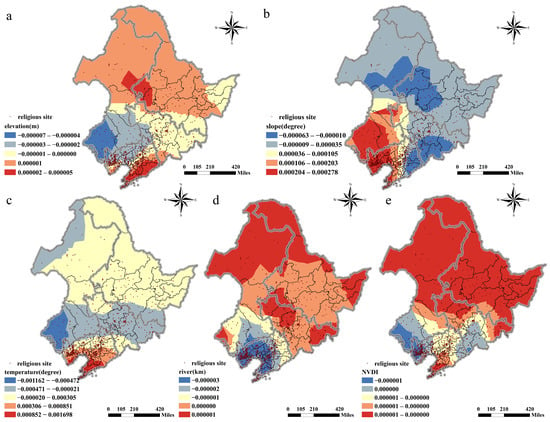

- Natural Factors

Elevation factor (X1). As shown in Figure 6a, its regression coefficient generally show a distribution pattern of “higher in the north and south, lower in the east and west”. According to China’s elevation classification standards, about 84% of religious sites in the basin are located in plain areas at 0–500 m. The “Dalian-Anshan-Dandong” region is a continuation of the Changbai Mountain range. Cultural landmarks of religious historical accumulation, such as Qian Mountains (a “sacred mountain of religious integration”) and the Great Black Mountain (a “religious sacred site”), have helped establish renowned religious sites like Tangwang Palace Taoist Temple in this region. The southwestern part of the basin is a continuation of the Greater Khingan Mountains, with a maximum elevation of 2650 m. Higher elevations make it difficult to establish and maintain religious sites.

Figure 6.

Spatial heterogeneity of natural factors. (a) Spatial distribution of regression coefficients for elevation factor; (b) Spatial distribution of regression coefficients for slope factor; (c) Spatial distribution of regression coefficients for temperature factor; (d) Spatial distribution of regression coefficients for river factor; (e) Spatial distribution of regression coefficients for NDVI factor.

As shown in Figure 6b, the influence of the slope factor (X2) decreases from southwest to northeast, and this trend is linked to flood prevention. The southern part of the basin, adjacent to the Bohai Sea and Yellow Sea, is prone to natural disasters such as floods due to harsh conditions like storm surges and waves. Steeper slopes help reduce damage from these disasters, ensuring the safety and protection of religious sites.

Temperature factor (X3). As shown in Figure 6c, temperature has a positive impact only in the southern part of the basin, with significant spatial heterogeneity. The basin’s annual average temperature ranges from −5.43 °C to 13.35 °C, and religious sites in the 5 °C and 13.3 °C range account for 80.9%. The higher temperatures in the southern basin, which are suitable for human habitation, have to a certain extent facilitated the formation of the spatial distribution of religious sites.

River factor (X4). As shown in Figure 6d, its regression coefficient shows an increasing trend from south to north in basin. On the one hand, the southern part of the basin is close to the ocean, and natural disasters such as floods and typhoons damage religious sites, thus inhibiting the formation of their spatial distribution; On the other hand, with the development of urbanization and industrialization, the water supply-demand conflict in the basin has intensified. Some rivers in the basin have dried up, leading to sharp deterioration of river ecosystems, which poses challenges for the establishment and protection of religious sites near dense river areas.

As shown in Figure 6e, the vegetation coverage (NDVI) factor (X5) has little influence on the spatial distribution of religious sites in the basin. When establishing religious sites in the basin, immigrant groups prioritize basic natural factors such as terrain and temperature, leading to “denser in the south and sparser in the north” spatial distribution pattern for most cultural heritage in the basin [42]. While areas with high vegetation coverage are ideal for religious sites, the unique natural conditions of the basin weaken the influence of NDVI factor.

- 3.

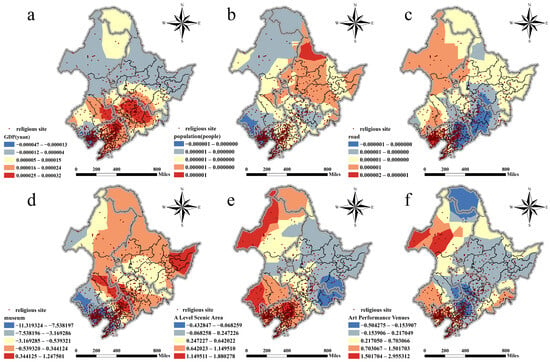

- Socio-economic Factors

Policy factors have a significant influence on the spatial distribution of religious sites in the basin. As shown in Figure 7d, the high regression coefficients of museums (X9) are concentrated in the “Tongliao-Siping-Tieling-Fushun” belt. This region spans three provinces—Inner Mongolia, Jilin, and Liaoning—and includes cultures of multiple ethnic groups such as Manchu, Mongolian, and Han. Religious sites here have both religious and historical attributes, so the growing number of museums in this area promotes the spatial agglomeration of religious sites. The remaining areas have negative regression coefficients, showing a gradual decreasing trend from south to north. In these regions, museums and religious sites maintain a competitive relationship in terms of functional attributes.

Figure 7.

Spatial heterogeneity of socio-economic factors. (a) Spatial distribution pattern of regression coefficients corresponding to the GDP factor; (b) Spatial distribution pattern of regression coefficients corresponding to the population density factor; (c) Spatial layout of the road network density factor’s regression coefficients; (d) Spatial layout of the museum factor’s regression coefficients; (e) Spatial layout of the A-rated tourist attractions factor’s regression coefficients; (f) Spatial layout of the performing arts venues factor’s regression coefficients.

As revealed in Figure 7e, the influence of A-rated tourist attractions (X10) on the spatial distribution of religious sites in the basin decreases gradually from west to east, and shows a nuclear-shaped distribution in the “Shenyang-Liaoyang” area. In these areas, the resource spillover effects of A-rated tourist attractions effectively promote the development and protection of surrounding religious sites, boosting the appeal of local religious tourism.

As shown in Figure 7f, the regression coefficients of performing arts venues (X11) within the Songliao River Basin increase radially from the core area of “Tongliao-Shenyang-Fushun-Tieling-Siping” to surrounding regions. These venues, likely functioning as major policy-oriented public cultural projects, may consequently compress the spatial presence of religious sites in these areas to some extent; In surrounding areas with ample land resources, many performing arts venues integrate religious activities with cultural performances, enhancing the local cultural atmosphere and boosting religious activities, which leads to a relatively clustered spatial distribution of religious sites in these areas.

4. Conclusions

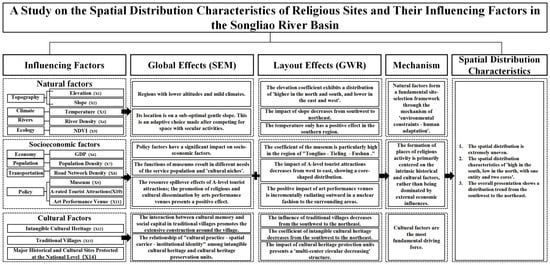

This study focuses on 1288 religious sites in the basin and uses SEM and GWR to analyze their spatial distribution characteristics and influencing mechanisms (Figure 8), providing a quantitative research support for the development of such sites [43].

Figure 8.

Analysis of Influencing Factors for Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Religious Sites in the Songliao River Basin.

- First bullet; The distribution of religious sites in the basin is overall uneven, showing the pattern of “higher in the south, lower in the north, one cluster and two cores”, and the northeast to southwest direction is the main extension direction. Within the basin, Liaoning Province shows a W-shaped agglomeration feature, while Jilin Province forms an agglomeration structure with a high-density “primary core” and a medium-high density “secondary core”.

- Second bullet; Cultural factors are the core driving force for religious sites in the basin. The global results of the SEM show that traditional villages (X13) promote the agglomeration of religious sites through the linkage of cultural memory and social capital. Combined with the GWR model results, this influence decreases from southwest to northeast, forming a spatial pattern of “one village, multiple temples”. In contrast, in the northeastern part of the basin, the cultural centripetal force of traditional villages (X13) is relatively weak. Intangible cultural heritage (X12), NLMHCS (X14) and religious sites form a triadic symbiotic mechanism of “cultural practice, spatial carrier, institutional identity”. The GWR model reveals that high-value areas of intangible cultural heritage (X12) are concentrated in the “Liaoxi Corridor”, a cultural passageway that plays a key role in faith integration and folk practice; NLMHCS (X14) have high-influence zones that are highly consistent with historical regional political and economic centers.

- Third bullet; Among natural factors, the influence of NDVI (X5) was not significant in both models, which is slightly different from existing research [15]. Results of the SEM show that religious sites in the basin tend to be located in areas with lower elevation and warm climate. Combined with GWR model results, the positive effect of slope (X2) is particularly prominent in the southern coastal flood-prone areas. Religious sites clearly avoid flood risks and secular spatial competition, choosing suboptimal gentle slopes. The setting of implicit boundaries for multiple selective natural conditions jointly weakens the influence of NDVI (X5).

- Fourth bullet; Among socio-economic factors, GDP (X6), population density (X7), and road network density (X8) have no significant influence. This indicates that the spatial distribution of religious sites in the basin is dominated by the “endogenous cultural mechanism” rather than external economic drivers. The global results of the SEM show that: A-rated tourist attractions (X10) and performing arts venues (X11) exert significantly positive effects on the spatial distribution of religious sites, while museums (X9) have a spatial suppression effect. The GWR model reveals that museums (X9) have positive regression coefficients in Tongliao City, Siping City, Tieling City, Fushun City, and show negative competition in most other regions, verifying the “cultural niche” differentiation mechanism. The high-influence areas of A-rated tourist attractions (X10) are concentrated in the Shenyang, Liaoyang area, highlighting the resource spillover effect of religious tourism. The influence of performing arts venues (X11) increases outward from policy-driven core areas, exhibiting a dual role of “squeezing” and “promoting”.

Based on the Songliao River Basin case, this study’s conclusions have certain generalizability for other regions in China; future research can advance related studies via comparative case analyses.

5. Discussion

This study takes religious sites in the Songliao River Basin as a case to explore their spatial distribution characteristics and the mechanisms of influencing factors, filling the research gap in relevant studies on Northeast China. The above conclusions are discussed from multiple aspects below.

The Songliao River Basin is a region with multi-ethnic integration [44]. Existing studies mostly adopt a single disciplinary framework, some using descriptive statistics or traditional regression analysis, with limitations of ignoring spatial autocorrelation and failing to reveal the spatial heterogeneity of influencing factors [11,16]. This phenomenon has occurred multiple times in the basin [45]. This study introduces the coupling method of SEM and GWR model. Using Geoda 1.22.012 and ArcGIS 10.8.1, the global autocorrelation Moran’s I index is calculated as 0.973543 (p < 0.01), confirming that religious sites in the basin have a strong spatial agglomeration feature. The global goodness of fit R2 of the SEM is 0.978883, revealing the “average” effect of influencing factors [46]. The GWR model’s goodness of fit R2 is 89.1%, significantly better than the 66.3% of traditional OLS regression, and successfully captures the “local” effect of influencing factors. For example, in the SEM model, the correlation coefficient of traditional villages (X13) reaches 3.61049 (p < 0.001), ranking the highest among all influencing factors, showing a significant positive correlation with the spatial distribution of religious sites overall. However, the GWR model shows that its regression coefficient is as low as −5.4355 in some areas of Jilin Province, presenting a negative effect. This feature of “global consistency, local heterogeneity”, which is difficult to capture by a single model, is consistent with the relevant conclusions of TANG, Y et al. in the study on the spatial distribution of the four major religions in China [7]. In addition, this study attempts to introduce social capital theory as an analytical perspective for understanding the human-land-religion interaction. Religious sites are not only spaces of faith, but also important nodes in social networks, capable of uniting communities and inheriting culture. However, this study is only a preliminary theoretical exploration. Future research will deepen this perspective. For example, it can specifically explore the differences in various types of religious sites in accumulating social capital and maintaining village structures, as well as their coupling relationship models with the spatial forms of traditional villages. This has important theoretical value for understanding the formation of single or multi-religious communities by ethnic minorities and Han people at different spatial scales.

Most existing show that GDP [47], population density [11] and road network density [48] all have significant impacts on their spatial distribution characteristics. However, the global analysis results of SEM show that none of the three passed the significance test. On the contrary, policy factors have become a significant driving force at the global level and exhibit strong spatial heterogeneity in the GWR model, revealing that top-down planning and policy interventions have become the dominant force shaping the religious spatial pattern in the basin. Policy documents such as the 14th Five-Year Plan for the Integrated Development of Culture and Tourism in Tongliao City explicitly propose integrating historical temples, A-level tourist attractions and performing arts venues in the region to build distinctive “cultural tourism corridors” or “tourism clusters”. In this model, the location selection of religious sites does not depend on the basin’s economic strength or population size, but on their node positions and cultural endowments in the cultural tourism network under policy planning. This is highly consistent with the research conclusion of Fang, W et al. that “the protection of cultural heritage in the basin is dominated by policies” [18]. The basin has experienced rapid urbanization and population migration over the past two decades. Traditionally, the distribution of religious sites has followed population agglomeration [43]. However, in some new districts within the basin, despite high population density, the allocation of religious land has not grown naturally in proportion to the population. This is underpinned by strict land use planning and regulatory policies. Religious land is tightly controlled, and its approval and supply lag far behind the growing demand of religious believers, resulting in a situation of “more believers but fewer temples”. As some studies have pointed out, state power and government policies are key external forces shaping the religious spatial pattern. The results of this study provide strong empirical evidence for this argument in Northeast China.

The planning and construction of religious sites should fully consider the actual situation of religious believers. The particularity of the facilities makes traditional hierarchical support and adaptive management inapplicable. To a certain extent, this study also reveals the response mode of regional policies to multicultural spaces, religious governance and their spatial development. Based on the results of this study, the government and functional departments can formulate classified protection strategies according to the influence mechanism of religious sites.

This study also has several limitations. It only involves Buddhism and Taoism, and does not cover Christian churches, Islamic churches, or other folk belief sites. The reason is that the term “religious sites” is clearly defined by the government. The State Administration for Religious Affairs of China has established the “Basic Information of Religious Sites” Database, but this database mainly discloses information about Buddhism and Taoism. Future research will establish a multi-source data fusion mechanism, supplement the spatial coordinates of other types of religious sites through POI data and community field surveys, and build a full-religion-type database for the Songliao Basin. Meanwhile, due to data acquisition limitations, some influencing factors have not been fully included. In addition, research on the micro-behavior patterns and subjective ideology between migrant groups and religious sites in this basin is still insufficient, and these issues can be taken as directions for further research in the future.

Author Contributions

Manuscript writing by T.L.; data processing and assistance in writing by Y.W.; data collection and compilation by Y.Y. and X.Y.; review and revision by P.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by “The Major Project of Philosophy and Social Sciences Research in Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions in 2025” (Number: 2025SJZD147); “The Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities” (Number: NJ2025012); “Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics Undergraduate Education Reform Research Project—General Category in 2025” (Number: 2025JGYB18).

Data Availability Statement

Some of the data used in this study were provided by the Resources and Environmental Science Data Center (https://www.resdc.cn, accessed on 21 May 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, X. Religious activity sites. China Religion 2023, 90. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, L. Geography and religion: Trends and prospects. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1990, 14, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddard, R.H.; Prorok, C.V. Geography of Religion and Belief Systems. In Geography in America at the Dawn of the 21st Century; Gaile, G.L., Willmott, C.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 760–768. [Google Scholar]

- Sopher, D.E. Geography and Religions. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1981, 5, 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopher, D.E. Geography of Religions; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1967; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Peach, C. Social geography. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1999, 23, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Lin, X.; Lu, Y. Spatial distribution and diffusion patterns of four major religions in China: A discussion of religious development in different types of cities. Geogr. Res. 2023, 42, 2466–2489. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, O. The geographies of religious conversion. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2012, 36, 440–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhu, A.; Liu, Q. Spatial distribution characteristics of religious architecture heritages in China and the influential factors. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2018, 5, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, X.; Zhu, H.; Tang, X. SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION AND EVOLUTION OF URBAN RELIGIOUS LANDSCAPE—A Case Study of the Protestant Churches in Guangzhou after 1842. Hum. Geogr. 2009, 24, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, N.; Ding, L.; Qu, J.; Zhou, Q. Spatial evolution and influencing factors of religious places from a socio-spatial perspective: An empirical analysis of Christianity in China. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zou, K.; Duan, K.; Shen, Y. Spatial differentiation characteristics and influencing factors of buddhist monasteries in Yunnan province. Trop. Geogr. 2024, 44, 315–325. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L.; Zhong, Y.; Feng, X.; Huang, J. Research on spatial-temporal pattern and evolution model of religious sites in Jiangxi province. World Reg. Stud. 2016, 25, 166–176. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Wang, G.; Hu, W. Study on the spatial pattern of religious landscape in Shanxi Province. World Reg. Stud. 2019, 28, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, D.; Zoh, K. Study on the spatial distribution patterns and formation mechanism of religious sites based on XGBoostSHAP and spatial econometric models: A case study of the Yangtze River Delta, China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 24, 5853–5874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannan, P.; Liangwen, G. Cultural space practice of intangible cultural heritage of festival activities and its evolution: A case study of Dragon Boat Festival (Shenzhou Events). Econ. Geogr. 2023, 43, 227–235. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, T.; Duan, L.; Liritzis, I.; Li, J. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of intangible cultural heritage in the Yellow River Basin. J. Cult. Herit. 2024, 66, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Zhuoqi, L.; Ying, D.; Leye, W. Cultural Heritage Conservation from the Perspective of River Basin. Herit. Arch. 2024, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.C.; Li, B.J.; Qiu, S. Geographical Spatial Pattern and Spatiotemporal Suitability Evolution of Cultural Heritage in the Liao River Basin. Landsc. Archit. 2025, 32, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y. The Historical Evolution and Contemporary Value of Northeastern Immigrant Culture. Soc. Sci. Front 2025, 268–273. [Google Scholar]

- TIAN, J.; LIN, Y. The Regional Development of the Song-Liao Culture. Cent. Plains Cult. Res. 2014, 2, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Yanchun, X.; Ke, N.; Xuelan, L. Spatial-temporal dynamic changes of land use and ecological effects in Songliao Basin. J. China Inst. Water Resour. Hydropower Res. 2024, 22, 84–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Han, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Dai, J. Spatiotemporal Distribution and Evolution of Global World Cultural Heritage, 1972–2024. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Yu, Y.; Liang, L.; Ma, Z. Spatial distribution of the carrier of the folk religion and its influencing factors: A case study of Temple in Yuzhong County. Arid Land Geogr. 2019, 42, 363–375. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Li, S.; Liu, W. Study on the Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Intangible Cultural Heritage Along the Great Wall of Hebei Province. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhu, H. The Spatial Characteristics and the diffusion of foreign religions in a port city: A case study of the protestant churches in Fuzhou. Prog. Geogr. 2011, 30, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, R.-Z.; Lin, L.; Xu, J.-F.; Dai, W.-H.; Song, Y.-B.; Dong, M. Spatio-temporal characteristics of cultural ecosystem services and their relations to landscape factors in Hangzhou Xixi National Wetland Park, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, B.W. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Y. The scope and spatial correlation features of the core area of hierarchic culture of Beijing Xuan Nan in Qing Dynasty from the field view. Geogr. Res. 2020, 39, 836–852. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wei, P.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, X.; Pang, C. Explore the mitigation mechanism of urban thermal environment by integrating geographic detector and standard deviation ellipse (SDE). Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Newsam, S. Spatio-temporal sentiment hotspot detection using geotagged photos. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, San Francisco, CA, USA, 31 October 2016–3 November 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Runze, Y. A study on the spatial distribution and historical evolution of grotto heritage: A case study of Gansu Province, China. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daqian, L.; Dan, W.; Jun, X.; Hanjie, S. The Spatial Pattern of Rural Settlements and Its Influencing Factors in Changbai Mountain Region. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2024, 31, 383–390. [Google Scholar]

- Xinyu, H.; Hengrui, C.; Pengwen, Z.; Yuxiao, J.; Ning, Q. Driving Factors and Spatial Distribution of Disabled People in Tianjin. J. Hum. Settl. West China 2023, 38, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Xinming, Z.; Xiaoning, S.; Pei, L.; Ronghai, H. Spatial downscaling of land surface temperature with the multi-scale geographically weighted regression. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 2021, 25, 1749–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Cai, J. Progress of spatial statistics and its application in economic geography. Prog. Geogr. 2010, 29, 757–768. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Bao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Ge, Q. Impact of accessibility on housing prices in Dalian city of China based on a geographically weighted regression model. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, L.Z.; Hong, Q.W. Public Cultural Space in Traditional Village and the Village Governance in Ethnic Regions—A Case Study of “La Si Festival” in Benzilan Village, Deqin County, Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan Province. Acad. Explor. 2011, 4, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Chenhall, R.H.; Hall, M.; Smith, D. Social capital and management control systems: A study of a non-government organization. Account. Organ. Soc. 2010, 35, 737–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoyue, X.; Chengcai, T.; Wenqi, L. Spatial distribution and cultural features of traditional villages in Beijing and influencing factors. J. Resour. Ecol. 2022, 13, 1074–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, X.; Wu, J. Dynamics of spatial pattern between population and economies in Northeast China. Popul. J. 2018, 40, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C. The Evolution of Landscape Layout Concept of Lingnan Taoist Zuting Temples in the Qing Dynasty. Nat. Resour. 2023, 14, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Cheng, G.; Wang, M. Study on the Influencing Factors of the Spatial Distribution of Ancient religious sites in Inner Mongolia. Acad. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 3, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Luo, R. Unravelling uneven livelihood transformations in China’s multi-ethnic Southeast Asian borderland: Perspectives from spatial interactions. Area 2025, 57, e70006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Wang, L.; Ge, F.; Yan, J. Detecting the interaction between urban elements evolution with population dynamics model. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Cao, Y. Study on the spatial distribution and influential factors of rural poverty in Xinjiang. World Reg. Stud. 2020, 29, 650. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Exploring Determinants of GDP Growth: The Significant Role of Religion. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Econ. Res. 2024, 9, 2297–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, B.; Li, H.; Li, L.; Zhang, J. Sustainable tourism at nature-based cultural heritage sites: Visitor density and its influencing factors. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.