Abstract

Post-disaster temporary housing units (PDTHUs) are crucial to the rebuilding process after disasters; however, current designs fall short in several areas, including user comfort, contextual relevance, and long-term flexibility. This situation suggests that design weaknesses emerge through interactions among multiple factors, requiring an analytic approach that goes beyond isolated evaluation. This study aims to (1) identify the main design issues in PDTHUs, (2) explore the relationships among these issues, and (3) prioritize interventions by grouping causes for decision makers. First, eleven primary design problems were identified through a systematic literature review. Next, a matrix-based questionnaire was developed and administered to five experts with experience in post-disaster projects. In the third stage, expert opinions were analyzed using the DEMATEL (Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory) method. As a result, the design problems were classified into “cause” and “effect” groups, and a cause-and-effect diagram was created. The findings indicate that the lack of contextual and cultural integration in design (4.485); the absence of pre-disaster planning and prototyping (3.964); and low thermal, acoustic, and ergonomic comfort (3.385) are the most influential issues because they belong to “cause groups” with high Pi values. This study provides a guiding framework for practitioners and policymakers to allocate resources efficiently, plan strategically, and develop context-sensitive designs.

Keywords:

post-disaster; temporary housing; design challenges; decision-making; DEMATEL; PRISMA; SLR 1. Introduction

Disasters, caused by natural, technological, or human-made events, disrupt societies’ order and lead to significant physical, economic, and social damage [1]. In recent years, factors like climate change, unplanned urbanization, and rising population density have significantly increased both the frequency and severity of disasters. This has prompted the need for more comprehensive, planned, and strategic approaches, especially in post-disaster reconstruction efforts.

Temporary housing areas are among the most vital elements in rebuilding after a disaster. These areas not only provide short-term housing options but also require thorough assessments related to social cohesion, user safety, and environmental sustainability. This situation calls for viewing temporary housing not just as an architectural design challenge but also as a complex system to be designed.

This need for a multidimensional perspective has also shaped the scholarly discourse, leading to a diverse body of research that examines temporary housing design through various methodological lenses and thematic priorities.

The literature has explored the design risks of post-disaster temporary housing (PDTH) from various perspectives and methodological approaches. For instance, Cerrahoglu and Maden [2] investigated design flexibility issues through analytical assessments and model proposals, showing that current typologies are insufficiently flexible to meet evolving user needs. Rahmayati [3], on the other hand, analyzed the Aceh case through qualitative fieldwork and socio-cultural observation, demonstrating that mismatches between housing design and local living practices led to user dissatisfaction and social disengagement. Similarly, Montalbano and Santi [4] studied the life-cycle performance of PDTH, as well as reuse and sustainability risks, by developing a conceptual framework and applying a needs-based assessment. Research linking design choices to local knowledge shows that traditional housing systems can inform the design of temporary shelters [5,6]. Meanwhile, Grundy [7] discussed the structural fragility of temporary housing through theoretical engineering analysis and risk-reduction paradigms, arguing that deficiencies in post-disaster performance arise from inadequate engineering standards.

As can be seen, many sub-topics, such as sustainability and economy, have not been addressed in various scopes in post-disaster temporary housing units. In particular, design issues related to user comfort, contextual appropriateness, and long-term flexibility are widespread in the literature. When existing studies were analyzed according to their methodologies, there were several studies conducted using qualitative ([8,9,10]) and quantitative ([11,12,13]) methods. Although these methods gain significant insight into domain, alone are insufficient to solve these problems [14,15]. At this point, multi-parameter design risks should be addressed holistically for objective evaluation. The following techniques are used in the literature to address these multiple problems objectively: MCDM (Multi-Criteria Decision-Making) [16,17], such as DEMATEL (Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory) [14,18], and fuzzy-based extensions, such as Fuzzy TOPSIS [19], Fuzzy AHP [20], and other methods, like CPM [21].Among these, DEMATEL is emerging as a structural modeling method that decomposes cause-and-effect variables by revealing causal relationships among multiple factors in complex systems [14,18].

The building production process starts with the architectural design phase. The architectural design phase is a thorough, cause-and-effect-driven process. Every decision made during the design phase impacts other methods, including usage and lifespan. Therefore, to minimize problems, the design process must be structured appropriately, and decisions at this stage should be made with minimal errors. The scarcity of studies on causal relationships in this area emphasizes the significance and novelty of this research.

Unlike existing studies in the literature, this research aims to identify the design problems faced in PDTHUs systematically (1), uncover the causal relationships between these issues (2), and develop a strategic framework that prioritizes design concerns for decision makers (3).

In line with the study’s objective, the following Research Questions (RQ) were identified:

- RQ1: What are the main design challenges faced by temporary housing units after a disaster?

- RQ2: Can the causal relationships among the main design risks in post-disaster temporary housing units be analyzed using the DEMATEL method?

This study, conducted by answering these research questions, makes a unique contribution to the literature by addressing issues related to PDTHUs’ design not only descriptively but also through a systematic, cause-and-effect approach.

2. Literature Review and Research Gap

The challenges faced during post-disaster reconstruction are a common issue worldwide. A key part of this process is the provision of temporary housing units. These quickly constructed structures, after a disaster, not only meet the need for shelter but also greatly promote social cohesion, user satisfaction, and sustainability. Therefore, the success of temporary housing units largely depends on selecting the appropriate design approaches.

In the literature, temporary housing units are analyzed in terms of sustainability [22,23], management [24,25], financial [26], environmental [27,28], social [4,29], and design [2,3] dimensions. Among these topics, design issues are of particular importance due to their multidimensional impacts, which directly influence the system’s success [3,6,30].

Users reject THUs that are functionally incomplete, designed out of context, or lose their functionality quickly, leading to inefficient resource use and user dissatisfaction. Conversely, context-sensitive, flexible, and user-oriented designs support both the effective management of the temporary process and the long-term quality of life. Thus, research increasingly recognizes that design decisions influence both the immediate sheltering phase and long-term recovery outcomes [2,31,32].

Design problems encountered in THUs have been addressed through various studies in different contexts [2,3,7,24,31]. In the literature, ignoring the regional context is highlighted as a significant issue; it is noted that this leads to inadequacies in social acceptance, cultural adaptation, and meeting local needs [33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Additionally, the inability of THUs to adequately satisfy basic living needs is often criticized in the literature. Particularly, the lack of functional areas such as storage, wet areas, cellars, and modularity makes these buildings unsustainable [2,27,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47].

One of the most important strategies in designing temporary housing units is to systematically review experiences from past disasters. Otherwise, this leads to repeating similar mistakes and reduces learning capacity [27,48,49].

Structures that cannot quickly adapt to changing user needs lose their functionality when a temporary period is extended [2,4,43,50,51]. Ignoring aesthetic factors can have negative effects not only on architecture but also on users’ psychological bonding processes [22,52,53]. Issues related to user comfort have also been extensively discussed in the literature. Deficiencies in elements such as thermal insulation, natural ventilation, and noise control restrict the long-term usability of these buildings and negatively impact vulnerable groups like children, the elderly, and others [2,40,44,45,46].

Although these studies offer valuable insights, several gaps persist:

- First, most research treats design deficiencies as independent issues, whereas THU failures often emerge through interaction among multiple risks.

- Second, existing studies seldom analyze causal interdependencies among design problems or identify which risks trigger others.

- Third, while functional, contextual, environmental, and social shortcomings are widely reported, their systemic influence paths are not modeled or prioritized.

- Fourth, quantitative approaches remain limited, with most literature relying on qualitative and case-based reasoning.

- Finally, research rarely provides analytical guidance for design decision-making, leaving policymakers without tools to prioritize design risks.

Taken together, these issues indicate that the literature is rich in diagnosis, yet less developed in explanatory modeling—particularly in identifying how design risks interact or reinforce one another. Therefore, the conceptual and empirical findings discussed must be linked to their positioning within the research field. Table 1 facilitates this linkage by grouping PDTH studies according to focus, method and context, thereby analytically revealing the strengths and weaknesses of the existing literature.

Table 1.

Classification of PDTH studies.

Table 1 synthesizes published PDTHU studies by thematic lens, context, and method. A clear pattern emerges: most research originates in developing settings [5,15,49] (e.g., Türkiye, Iran, India), while studies from developed contexts predominantly focus on institutional or sustainability transitions rather than on design causality [56,59,62]. Methodologically, qualitative and conceptual studies dominate; quantitative and mixed methods are comparatively scarce and rarely examine interaction mechanisms [25,59,61].

These observations underscore a core methodological and knowledge gap: while design challenges are widely recognized, their causal relationships remain insufficiently understood. To address this limitation, this study applies the DEMATEL method to reveal cause-and-effect pathways among eleven design risks, classify factors into driver and dependent groups, and support prioritized design actions for PDTHUs. By doing so, it contributes not only to problem identification but also to a structured explanation of interdependencies, providing decision makers with a diagnostic model rather than isolated descriptions.

3. Research Method

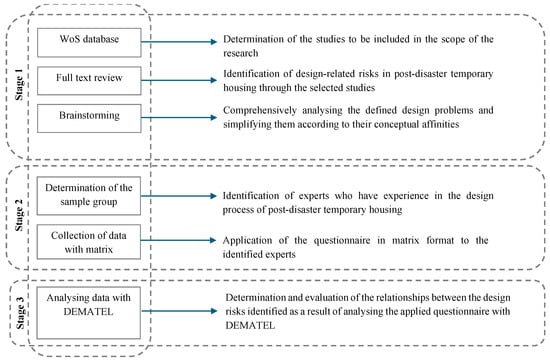

The methodology of this research consists of three main stages designed to systematically identify the design problems related to post-disaster temporary housing units (PDTHUs. To identify design problems associated with PDTHUs, a Systematic Literature Review (SLR) was conducted following the PRISMA protocol in the Web of Science (WoS) database. WoS was preferred not only for its superior algorithmic filtering performance compared to other repositories, but also for its higher indexing quality, stronger citation verification, and reduced risk of duplication, which collectively enhance the reliability of the review process. In the second stage, a matrix-based questionnaire was developed following DEMATEL procedures to evaluate the interactions among these problems. It was administered to five experts directly involved with PDTHUs. In the third stage, the experts’ evaluations were analyzed using the DEMATEL method to uncover causal relationships among the design problems, classifying the factors into “cause” and “effect” groups. As a result of these stages, a strategic framework was created to help decision makers prioritize specific design problems. The research process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram.

3.1. Search Protocol of Design-Related Risks in Post-Disaster Temporary Housing

To identify design problems with PDTHUs, an SLR was conducted following the PRISMA protocol in the WoS database. The reason for choosing WoS as a database is that it provides better algorithm performance than other databases [63].

In the SLR process, establishing well-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria is essential for narrowing the research scope and selecting only studies directly related to the topic [64]. Accordingly, the following search protocol was implemented.

ALL FIELDS = “post-disaster temporary hous*” OR “post disaster temporary hous*” AND “post-earthquake temporary hous*” OR “post earthquake temporary hous*” AND design AND risk*.

The wildcard (*) in this query functions as a wildcard operator to include various spellings and derivations of the main terms.

3.2. Evaluation of Design-Related Risks in Post-Disaster Temporary Housing

Identifying and assessing the design-related risks in PDTHU is essential for developing an effective disaster management strategy. This section aims to go beyond the ranking logic of traditional Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) methods, analyze the causal effects of factors on each other, and thus reveal the main factors. To achieve this, the DEMATEL method, which evaluates the mutual relationships among factors, was selected. A specially designed questionnaire was created for applying the DEMATEL method, and it was completed by five experts directly involved in the design of PDTHUs.

3.2.1. DEMATEL (Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory)

The DEMATEL method for analyzing complex and interconnected systems was developed by the Battelle Memorial Institute in Geneva during the 1970s [15]. This method is an effective tool for identifying and systematically analyzing cause-and-effect relationships among factors, especially when many factors interact [11].

The DEMATEL methodology employs a structural modeling approach based on graphical theory and analyzes causal influence diagrams to visualize the relationships between factors. These diagrams help clarify the structural relationships among the system’s factors by classifying them into two main categories: “cause (driving)” and “effect (dependent).” This allows decision makers to easily identify which factors have greater impact and which are more influenced by these impacts [11]. Compared to other multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) methods like the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM), and Analytic Network Process (ANP), the Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (DEMATEL) method provides significant advantages in analyzing complex systems. While AHP and ANP mainly focus on ranking or weighting criteria and often assume some level of independence among factors, DEMATEL explicitly models the mutual interdependencies and bidirectional causal relationships among them. Similarly, unlike ISM, which offers only a hierarchical structure, DEMATEL reveals both the strength and direction of influence between factors through numerical values and graphical representation. Therefore, DEMATEL is more suitable for this study because it supports a cause-and-effect, feedback-oriented analysis, which is crucial for understanding how design-related problems in post-disaster temporary housing units (PDTHUs) dynamically interact within the system [15].

The method’s application process starts by creating a direct relationship matrix based on expert opinions. It then involves the steps of weighting, normalizing, and transforming this matrix into a total impact matrix. Using the cause-and-effect matrix produced at the end and the impact diagram derived from it, the key factors in the system are identified, and strategic intervention areas can be determined. The DEMATEL method essentially involves 5 stages [14].

Creating the Direct Relationship Matrix

In DEMATEL analysis, the influence between variables was assessed using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (no influence) to 4 (very high influence). The matrix created by averaging the participants’ scores is called the average decision matrix and is usually represented by Z. When multiple decision makers are involved, a direct relationship matrix can be generated by averaging each decision maker’s evaluations [65].

Normalization

At this stage, all values in the direct relationship matrix obtained earlier are normalized by dividing them by the highest value in each row and column sums of the matrix. As a result, all values are scaled to the range [0, 1]. The normalization process follows Equations (1) and (2), which are commonly used in the literature.

Creating the Total Impact Matrix

In this step, the normalized direct relationship matrix from the previous step is subtracted from the unit matrix; the inverse of this matrix is then multiplied by itself to produce the total influence matrix, as shown in Equation (3).

Determination of Affecting and Effect Variables

At this stage, the sum of columns (rj) of the total effect matrix is calculated using Equation (4), and the sum of rows (di) is calculated using Equation (5).

After calculating di and rj values using Equations (4) and (5), Pi and Ei values should be determined. These values will help identify the relationships between variables and group them as “cause-effect”.

Pi value indicates the overall influence of a variable within the system (Equation (6)). In this context, it can be understood that variables with a high Pi value interact more strongly with other variables; meanwhile, variables with a low Pi value have a more limited connection to the system. Additionally, the Ei value shows the causal role of the variable (Equation (7)). Variables with a positive Ei value are classified as the “cause” group, whereas those with a negative Ei value are categorized as the “effect” group.

To build the relationship diagram within the DEMATEL method, a threshold value is chosen to assess the significance levels of the relationships in the overall influence matrix. In this study, the threshold value (θ) was calculated using the following formula:

where represents the arithmetic mean and denotes the standard deviation of all elements in the total influence matrix.

Creating the Casual Effect Diagram

Since the total effect matrix (T) represents the influence of a factor on others, a specific threshold value must be set to eliminate insignificant interactions during the analysis. Once this threshold is established, only effect levels above it is considered and visualized in the cause-and-effect diagram. According to a widely accepted method in the literature, the threshold is calculated by adding the mean and standard deviation of the T matrix [14]. Using this approach, the DEMATEL method was applied to the relevant factors following the outlined steps.

3.3. Determination of the Sample Group

In this study, the DEMATEL method was used, and experts with direct experience in designing PDTHUs were consulted. A purposive sampling strategy was selected to ensure that participants possessed substantial, context-specific knowledge capable of informing causal interpretations of design problems. The purposive approach is suitable for expert-judgment methods because the aim is to gather informed evaluations rather than statistically generalizable responses.

3.3.1. Expert Identification and Screening Procedure

Experts were identified through sectoral mapping of stakeholders engaged in Türkiye’s post-disaster housing processes, including project offices, architectural firms, municipal planning departments, and technical units involved in the delivery of container-based settlements. Potential candidates were first shortlisted through professional referrals and project-based affiliations, particularly those who had taken part in post-earthquake reconstruction initiatives.

A screening checklist was applied to ensure suitability. Inclusion criteria required that experts:

- (i)

- have at least five years of professional experience;

- (ii)

- have documented involvement in PDTHU design, implementation, or related disaster housing tasks;

- (iii)

- demonstrate familiarity with decision-making, technical evaluation, or design coordination processes;

- (iv)

- agree to complete a matrix-based causal questionnaire.

Exclusion criteria eliminated candidates with solely academic familiarity or those lacking field involvement. Furthermore, potential conflicts of interest were addressed by selecting individuals who were not subordinate to, supervised by, or in professional collaboration with the research team. To prevent dominance effects, experts were drawn from different institutions and project environments.

3.3.2. Panel Formation and Representation Rationale

Eight eligible experts were invited to participate, and five accepted, forming the final panel. Although modest in count, this size is methodologically sufficient for DEMATEL, which emphasizes depth of structured judgment over statistical inference. Panel composition was intentionally diversified to capture multiple disciplinary viewpoints affecting PDTHU design performance.

The final group included:

- two civil engineers,

- two architects, and

- one urban and regional planner.

Their professional experience ranged from 5 to 15 years, encompassing work in design offices, site-based implementation, technical coordination, project management, and spatial planning. This balance prevented overrepresentation of any single discipline and ensured that design risks were assessed through technical, spatial, user-oriented, and planning lenses. This diversity enables design problems to be approached not only from technical points of view but also from various perspectives, such as user needs, spatial planning, and management processes. Additionally, field experiences in disaster management and temporary housing enhance the credibility of the experts’ assessments.

Although the panel size (n = 5) is small in number, it is methodologically sufficient for DEMATEL, since the technique aims to gather structured causal relations from information-rich experts rather than generalize results to a larger population through statistical inference. Additionally, DEMATEL involves a fairly high cognitive load due to dense pairwise comparisons across 11 factors; maintaining a small panel helps preserve response quality and internal consistency while still covering the required disciplines. The final composition—two civil engineers, two architects, and one planner—reflects these criteria and aligns with the study’s focus on design-related judgments.

In light of these assessments, it is evident that the panel possesses representative power in terms of both disciplinary diversity and field experience. The experts’ areas of expertise, role responsibilities, and length of experience vary, and this diversity enables a more comprehensive interpretation of causal relationships related to design risks in the DEMATEL analysis. Therefore, the profiles of the experts included in the study are systematically presented in Table 2, demonstrating that the structural characteristics and professional scope of the panel are consistent with the research design.

Table 2.

Profiles of the Experts in the Study.

4. Research Findings

4.1. Determination of Design-Related Risks in Post-Disaster Temporary Housing

The search was conducted in September 2025, and 193 publications were identified during the initial screening. Subsequently, only studies published within the last ten years were filtered, reducing the number of publications to 147 (n = 46). By excluding non-English language studies (n = 3) and publications not indexed in SCI-E, SSCI, and ESCI (n = 27), 117 publications were chosen for inclusion in the study. Through brainstorming by the authors, eleven design problems related to PDTHUs were identified, coded, and presented in Table 3, along with the corresponding references (n: number).

Table 3.

Design-Related Risks in Post-Disaster Temporary Housing.

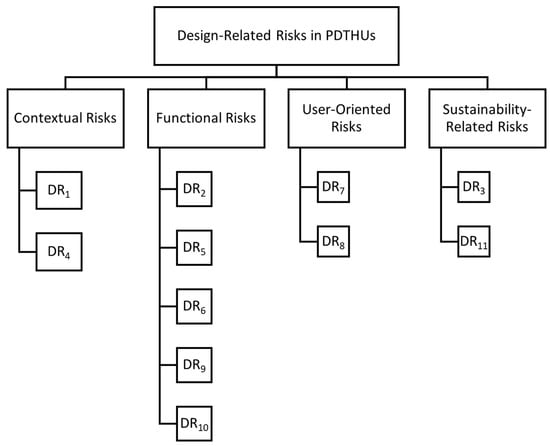

The identified design problems were categorized into four main groups—contextual, functional, user-focused, and sustainability-related—based on their thematic features derived from the literature (Figure 2). This categorization laid the conceptual groundwork for the DEMATEL analysis carried out in the subsequent stages.

Figure 2.

Conceptual classification of design-related risks in PDTHUs.

4.2. DEMATEL

To ensure methodological transparency and reproducibility, the Total Impact Matrix (T), derived from the normalized direct relationship matrix, is shown in Table 4. This matrix quantitatively illustrates the extent to which each design problem influences and is influenced by others within the system.

Table 4.

Total Impact Matrix.

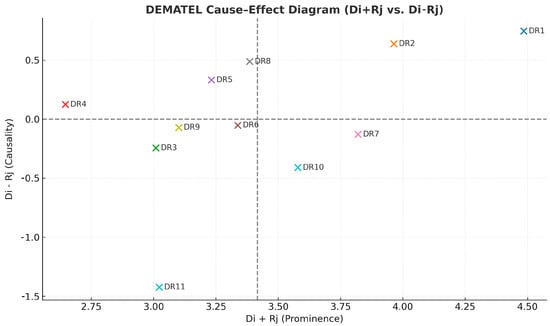

Before presenting the numerical results of the DEMATEL analysis, it is essential to provide an overview of how the results were interpreted within the study framework. This section explains the quantitative findings derived from the total relation matrix and the causal analysis conducted using the DEMATEL method. The computed Di and Rj values represent the degree to which each design problem influences or is influenced by others. In contrast, Pi = Di + Rj (Equation (6)) and Ei = Di − Rj (Equation (7)) values indicate the overall prominence and causal direction of each factor within the system. Based on these indicators, the following table summarizes the causal classification and interaction strength of eleven design problems identified in post-disaster temporary housing units.

According to Table 5, the Pi column (total influence value) indicates the overall interaction level of a factor within the system. Meanwhile, the Ei column shows the causal role of the factor and determines if it is a “cause” or an “effect.”

Table 5.

DEMATEL results.

Considering this data, since the Pi value of the DR1 problem is the highest, it can be said that the relationship between it and other design problems is the strongest. DR2 and DR7 follow DR1. Subsequently, DR10, DR8, DR6, DR5, DR9, DR11, DR3, and DR4 follow in order. Although DR4 (Failure to utilize lessons from previous housing designs) is classified within the cause group due to its positive Ei value, its overall influence on other factors is relatively limited. Therefore, DR4 can be interpreted as a minor causal factor, having a driving role within the system but with a lower impact intensity compared to dominant causal problems such as DR1 and DR2.

After the relationship ranking was established using the DEMATEL method, the influence of each of the eleven design problems on the others was identified. To do this, cause and effect variables were determined based on the Ei column in Table 5. Variables with positive Ei values were categorized as “cause,” while those with negative Ei values were categorized as “effect” (Table 5).

The last step of the DEMATEL method is creating the influence diagram to better understand how the design problems interact with each other. While drawing the influence diagram, the Pi and Ei values from Table 5 are used. The diagram is plotted with Pi values on the x-axis and Ei values on the y-axis. The horizontal dashed line represents the zero reference (Di − Rj = 0), distinguishing cause and effect factors, while the vertical dashed line indicates the mean value of Di + Rj, used to differentiate factors with higher and lower prominence. This diagram also helps to determine the relationships between the criteria. To do this, a threshold value is set based on the total influence matrix. Various methods are used to find this threshold. According to existing research, this process is often done by using the mean and standard deviation of the total influence matrix. The influence diagram developed for this study is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Impact Diagram of Design Problems of PDTHUs.

When the influence diagram is analyzed, it is observed that the DR1 problem with the highest Ei value (0.747) is the variable with the most significant influence on other design problems. The system-wide impacts of DR1 indicate that this factor is of strategic importance in the decision-making process and is a prioritized intervention point for improvement. Moreover, the DR1 factor is not only part of the cause group but also emerges as the most critical influence on the distribution node in the system. This order is followed by DR2 (0.639), DR8 (0.488), DR5 (0.332), and DR4 (0.125). Factors with negative Ei values are positioned as influencers within the system and are considered elements affected by external influences. Especially, DR11 stands out as the most impactful factor with a very low Ei value (−1.424). Similarly, DR10 (−0.410), DR3 (−0.244), DR7 (−0.129), DR9 (−0.071), and DR6 (−0.052) are also vulnerable.

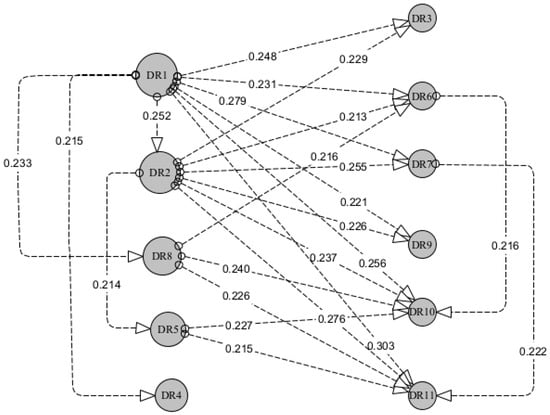

4.3. Creation of Relationship Map

Accordingly, the threshold value was calculated as 0.212 (Equation (8)). In line with this threshold, relationships with lower effects were considered insignificant and excluded from the analysis; only interactions above this threshold were included in the relationship diagram. This method ensures that only statistically significant interactions are included, aiming to reveal cause-and-effect relationships between the factors more reliably and robustly.

The direction of the arrows in the DEMATEL relationship map, created with the yEd Graph Editor (version 3), shows the causal relationships within the system.

For example, if DRi → DRj,

It is interpreted as “DRi factor influences DRj factor.” In other words, if the decision maker wants to solve a problem related to DRj, they should first improve DRi. The relationship diagram, as created, is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Relationship Map of Design-Related Risks in Post-Disaster Temporary Housing.

When the relationship map is analyzed, while DR1, DR2, and DR7 stand out with high Pi values, the limited number of strong relationships in the DR7 factor suggests that it is primarily involved in the system, with widespread but relatively weak interactions. This shows that although DR7 has a high overall system sensitivity, it does not have as decisive an effect on decision-making as DR1 and DR2. The DR7 factor, which has both cause and influence characteristics in the system, has a significant and direct effect on DR11 in particular (0.222). Considering that DR11 is one of the most effective factors in the system, this influence relationship shows that DR7 can be a critical intermediate factor. This effect emphasizes the importance of intermediary impacts rather than direct intervention targets.

Although the DR4 factor is in the cause group in the system, based on its Ei value (0.125), it does not show a direct effect on any factor in the relationship map, as its total effect size is low and none of its individual effects exceed the threshold of 0.212. This situation shows that DR4 creates widespread but weak effects in the system and is not a prioritized intervention area in critical decision processes.

Similarly, the DR6 factor has an above-threshold effect (0.216) on the DR10 factor, even though it is included in the general classification’s effect group. This shows that DR6, if left unaddressed, may have knock-on effects on another outcome factor, such as DR10. In terms of system dynamics, this effect of DR6 may make it a secondary priority intervention target.

The fact that “effect” factors can sometimes significantly influence other “effect” factors aligns with the unidirectional, non-hierarchical nature of DEMATEL. This shows that some factors in the system may have both cause-and-effect characteristics, and especially, feedback mechanisms should be considered in the analyses.

As a result, the relationship map derived from the DEMATEL analysis provides a clear and versatile visualization of the causal structure among the design problems in the system. When the map is analyzed, it is seen that especially DR1, DR2, and DR8 factors have significant effects on many other factors and play a decisive role in the system. These three factors are the core causal factors shaping the system.

In contrast, DR11 is among the most influenced outputs and is strongly influenced by a large number of factors (e.g., DR1, DR2, DR5, DR7, DR8). The fact that some factors in the semi-influenced position, such as DR6 and DR7, show suprathreshold effects on specific outputs (e.g., DR6 → DR10 and DR7 → DR11) reveals that this system is not only unidirectional but also involves complex and feedback structures.

5. Discussion

This study highlights the analytical power of the DEMATEL method in identifying causal relationships among design-related risks in PDTHUs. The analysis classifies each problem in the system as both a cause and an effect. The structure of the DEMATEL method, which accounts for bidirectional interactions and feedback loops, enables decision makers to conduct strategic evaluations, especially in complex and uncertain situations such as post-disaster periods [11,15].

According to the findings, the DR1 factor (Lack of contextual and cultural integration in design) has the highest Pi (4.485) and Ei (0.747) values and is identified as the most dominant factor in the system. The literature indicates that temporary structures that do not consider local context lead to issues with social cohesion and acceptance [33,34,36,37,38,39,66]. This result is consistent with recent field observations: container settlements deployed after the 2023 Kahramanmaraş earthquakes in Türkiye have revealed recurring complaints regarding gendered spatial needs, neighborhood fragmentation, and insufficient communal spaces [77]. Similar outcomes were documented in Japan following the 1995 Kobe earthquake, where prefabricated settlement clusters lacking communal areas contributed to isolation among elderly residents [78]. These empirical parallels reinforce DR1 as a key strategic priority for PDTHU decision-making.

DR2 (Absence of pre-disaster design planning and prototyping) and DR8 (Low thermal, acoustic, and ergonomic comfort) also attract attention with high Pi and positive Ei values. This suggests that inadequate planning and comfort significantly affect the effective use of temporary housing. The comfort factor is highlighted in the literature as being crucial for psychosocial health, especially in long-term accommodation settings [57,67,68,69,70]. The absence of standardized pre-disaster prototypes was observed in Türkiye’s emergency housing deployments in Kahramanmaraş (2023), where ad hoc layout decisions led to inconsistent quality [79]. Similarly, evaluations of Japan’s 2011 Tohoku prefabricated housing indicated overheating and ventilation limitations that affected resident well-being [80,81,82]. These cases strengthen the practical relevance of DR2 and DR8, confirming their systemic impact on PDTHU performance.

These findings can be attributed to the fact that post-disaster housing initiatives in Türkiye and similar settings often emphasize quick construction over design that considers local context. Previous research has indicated that ignoring local cultural patterns and environmental factors results in user dissatisfaction, social disconnection, and underused housing units [33,34,36,37,38,39,66]. The lack of pre-disaster design standards or prototype models also causes ad hoc decision-making during emergencies, which hampers design quality and consistency [57,67,68,69,70]. Additionally, issues related to comfort are common due to temporary materials and the neglect of environmental design, which diminishes habitability and long-term usability of the units [4,29,71,72,73]. Consequently, these three factors highlight systemic weaknesses in the design process, where adaptation to local context, preparedness, and user comfort are not sufficiently prioritized, despite their vital importance in post-disaster recovery.

DR7 (Insufficient aesthetic and visual quality) has limited interaction with a small range of factors despite its high Pi value (3.820). This shows that DR7 is a common but weakly influential factor in the system. Although indirect effects of aesthetic value on acceptance have been discussed in the literature [83], it is emphasized that aesthetic considerations often take a back seat to technical requirements [8,41,42].

Although the factor DR4 (Failure to utilize lessons from previous housing designs) has a positive Ei value, it does not have an impact above the threshold on any factor in the total impact matrix. This finding indicates that this factor is not prioritized for strategic intervention, even though it is part of the cause group in the system. Similar situations have been observed in previous DEMATEL applications [27].

On the other hand, while the factor DR6 (Lack of flexibility and adaptability in floor plans) was included in the effect group in the general classification, it had a significant effect (0.216) on the factor DR10 (Inadequate natural lighting and ventilation), indicating a bidirectional interaction structure. This non-hierarchical feature of the DEMATEL method allows the analysis of feedback mechanisms [84].

The findings of this study show that factors such as ignoring the local context (DR1) and failing to conduct pre-disaster design processes (DR2) are the leading causes of other design problems. This result aligns with the findings of Félix et al. [43], who indicate that not accounting for regional characteristics reduces social acceptance and delays recovery. Similarly, Hosseini et al. [27] emphasized that the lack of pre-disaster preparation and failure to learn from past experiences increase inefficiencies in housing processes. Additionally, the fact that user comfort inadequacies (DR8) are among the most influential factors supports the findings of Aloisio et al. [40] and Mutch [45], who found that issues with thermal insulation, ventilation, and acoustics limit the long-term habitability of housing units. Field observations from Türkiye and Japan support this causal pattern, validating that strategic interventions in contextual alignment and pre-planning may indirectly improve functionality, comfort, and usability [77,82].

In conclusion, the findings from the DEMATEL method offer strategic insights for decision makers regarding which issues to prioritize in the design of PDTHUs. Supported by comparative observations from Türkiye and Japan, analyzing Pi and Ei values together helps develop more effective, targeted intervention strategies by highlighting both the system’s structural and dynamic aspects.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the challenges in designing post-disaster temporary housing units and used the DEMATEL method to address them comprehensively. The results categorized the issues within the system as “cause” and “effect” factors. They revealed that DR1 (Lack of contextual and cultural integration in design), DR2 (Absence of pre-disaster design planning and prototyping), and DR8 (Low thermal, acoustic, and ergonomic comfort) have the most significant influence on the system.

This research provides a guiding framework for practice by identifying key design problems and arranging them in a causal hierarchy. Based on the DEMATEL results, a three-stage roadmap is recommended for decision makers and practitioners.

- Pre-disaster preparation: Development of design prototypes and standards in advance, systematic consideration of lessons learnt from past disaster experiences (DR2, DR4).

- Contextual and functional integration: Designing temporary housing units to reflect local cultural, social, and environmental conditions and providing adequate functional areas (DR1, DR3, DR5, DR6).

- User-oriented improvements: Developing aesthetic, comfort, and reusability criteria; thus increasing both social acceptance and sustainability (DR7, DR8, DR9, DR10, DR11).

This roadmap facilitates strategic prioritization of interventions, gradual optimization of resource use from the root causes, and increased effectiveness in post-disaster housing processes.

6.1. Conceptual Contributions

The study makes significant contributions to the literature on post-disaster temporary housing units at both the methodological and conceptual levels. While design problems, which were mainly addressed through descriptive approaches in the past, were evaluated, their causal relationships were also examined in this research; thus, the system’s dynamic structure was uncovered. It has been demonstrated that both the technical aspects of design issues and the contextual, cultural, and user-related factors should be considered together, and a new conceptual framework has been added to the literature. This approach provides a more comprehensive framework for future research and paves the way for comparative analyses.

6.2. Practical Contributions

The findings also have practical implications. Specifically, DR1, DR2, and DR8 were identified as having a significant influence, and enhancing these factors became a top priority that can trigger positive chain reactions within the system. This provides a framework for disaster management agencies, architects, engineers, and policymakers that can be directly used in strategic planning, developing design standards, and allocating resources. It is clearly shown that temporary housing units should not only be built quickly but also be livable, culturally appropriate, and sustainable in the long run.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Although this study provides significant insight into design challenges for post-disaster temporary housing units, it has some limitations. To begin with, the set of design factors was derived from a literature review carried out only through the Web of Science database. While WoS includes a wide range of high-quality publications, depending on a single source inevitably narrows the pool of studies that can be captured. Future work could search across WoS, Scopus, and other indexed platforms to provide a broader, more balanced overview of research on temporary housing.

Another limitation concerns the geographical context. The empirical component of this research focuses on Türkiye, a developing country with its own institutional and cultural characteristics. The results should therefore be understood within this specific setting. Studies conducted in other developing countries—or in contrasting contexts with different climate, governance, or socio-cultural conditions—would help determine whether the relationships observed here hold more generally.

A further limitation arises from the expert group used in the DEMATEL analysis. The study relied on purposive sampling and included a small number of professionals with direct experience in temporary housing. Although the selected experts provided detailed and relevant insights, a broader group could offer a wider range of viewpoints. Future research may involve larger panels or combine expert assessments with surveys or interviews from residents and practitioners to enrich the evaluation.

Lastly, the choice of DEMATEL as the analytical method brings its own restrictions. The method relies heavily on expert judgment, and the construction of thresholds during analysis involves a degree of subjectivity. It also captures causal influences in a particular way, which may not reflect all aspects of complex decision environments. Upcoming studies might compare DEMATEL results with findings derived from other approaches—such as ISM, ANP, structural equation modeling, or probabilistic causal models—to test the stability of the relationships identified.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G.A. and M.S.; methodology, M.S.; software, M.S.; validation, G.G.A.; formal analysis, M.S.; investigation, G.G.A. and M.S.; resources, M.S.; data curation, M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.G.A. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, G.G.A.; visualization, M.S.; supervision, G.G.A.; project administration, G.G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of HASAN KALYONCU UNIVERSITY (protocol code E-64922182-050.04-93496 and 12.09.2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Grammarly Pro for the purposes of English language editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PDTHUs | Post-disaster temporary housing units |

| THUs | Temporary housing units |

References

- Ergünay, O. Afete Hazırlık ve Afet Yönetimi; Türkiye Kızılay Derneği Genel Müdürlüğü Afet Operasyon Merkezi: Ankara, Turkey, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cerrahoğlu, M.; Maden, F. Design of Transformable Transitional Shelter for Post Disaster Relief. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2024, 15, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmayati, Y. Post-Disaster Housing: Translating Socio-Cultural Findings into Usable Design Technical Inputs. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 17, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalbano, G.; Santi, G. Sustainability of Temporary Housing in Post-Disaster Scenarios: A Requirement-Based Design Strategy. Buildings 2023, 13, 2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorshidian, A.; Fayazi, M. Critical Factors to Succeed in Post-Earthquake Housing Reconstruction in Iran. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 94, 103786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza Mojahedi, M.; Vafamehr, M.; Ekhlassi, A. Designing Post-Disaster Temporary Housing Inspired by the Housing of Indigenous Nomads of Iran. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2021, 16, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, P. Structural Design for Disaster Risk Reduction. Aust. J. Struct. Eng. 2013, 14, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dishar, M.M.; Altaie, M.R. Use Risk Score Method to Identify the Qualitative Risk Analysis Criteria in Tendering Phase in Construction Projects. J. Eng. 2022, 28, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzepka, I.; Zehetmair, C.; Roether, E.; Kindermann, D.; Cranz, A.; Junne, F.; Friederich, H.-C.; Nikendei, C. Impact of and Coping With Post-Traumatic Symptoms of Refugees in Temporary Accommodations in Germany: A Qualitative Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.J. Using Fuzzy DEMATEL to Evaluate the Green Supply Chain Management Practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 40, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbarzadeh Ghomi, S.; Wedawatta, G.; Ginige, K.; Ingirige, B. Living-Transforming Disaster Relief Shelter: A Conceptual Approach for Sustainable Post-Disaster Housing. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2021, 11, 687–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rian, I.M.; Chang, D.; Park, J.-H.; Ahn, H.U. Pop-Up Technique of Origamic Architecture for Post-Disaster Emergency Shelters. Open House Int. 2008, 33, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.; Denis Granja, A.; Fregola, A.; Picchi, F.; Portioli Staudacher, A. Understanding Relative Importance of Barriers to Improving the Customer–Supplier Relationship within Construction Supply Chains Using DEMATEL Technique. J. Manag. Eng. 2019, 35, 04019002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, J.I.; Wu, H.H.; Huang, K.K. A DEMATEL Method in Identifying Key Success Factors of Hospital Service Quality. Knowl. Based Syst. 2010, 23, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappi, M.M.L.; Nappi, V.; Souza, J.C. Multi-Criteria Decision Model for the Selection and Location of Temporary Shelters in Disaster Management. J. Int. Humanit. Action. 2019, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadnazari, Z.; Mousapour Mamoudan, M.; Alipour-Vaezi, M.; Aghsami, A.; Jolai, F.; Yazdani, M. Prioritizing Post-Disaster Reconstruction Projects Using an Integrated Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Approach: A Case Study. Buildings 2022, 12, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, A. A Multi-Criteria Decision Approach Based on DEMATEL to Assess Determinants of Shelter Site Selection in Disaster Response. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 31, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoodi, A.I.; Khalilzadeh, M. Identification and Evaluation of Construction Projects’ Critical Success Factors Employing Fuzzy-TOPSIS Approach. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 1593–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyoud, S.H.; Kaufmann, L.G.; Shaheen, H.; Samhan, S.; Fuchs-Hanusch, D. A Framework for Water Loss Management in Developing Countries under Fuzzy Environment: Integration of Fuzzy AHP with Fuzzy TOPSIS. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 61, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrucci, D.V.; Wilson, J.; Brown, R.; Mireles Camey, J.; Doktycz, C.; Perry, M.; Buitrago, G.C. Using the Critical Path Method (CPM) for Evaluating Allocation Potential of Temporary Housing Units. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2025, 40, 1113–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, H.; Cosgun, N. Reuse and Recycle Potentials of the Temporary Houses after Occupancy: Example of Duzce, Turkey. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.C.S.; Pereira, N.N. Reducing the Response Time to the Homeless with the Use of Humanitarian Logistics Bases (BLHs) Composed of Shipping Containers Adapted as Temporary Shelters. Rev. Gest. Ambient. Sustentab. 2021, 10, e19494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D.; Van Aken, J.E. Developing Design Propositions through Research Synthesis. Organ. Stud. 2008, 29, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C. Strategic Planning for Post-Disaster Temporary Housing. Disasters 2007, 31, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Valcárcel, J.; Aragón, J.; Muñiz, S.; Freire-Tellado, M.; Mosquera, E. Transportable Temporary Homes with Folding Roof. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2024, 20, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.A.; Pons, O.; de la Fuente, A. A Sustainability-Based Model for Dealing with the Uncertainties of Post-Disaster Temporary Housing. Sustain. Resilient Infrastruct. 2020, 5, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ng, Y.Y.E. Post-Earthquake Housing Recovery with Traditional Construction: A Preliminary Review. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2023, 18, 100283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakes, T.R.; Deane, J.K.; Rees, L.P.; Fetter, G.M. A Decision Support System for Post-Disaster Interim Housing. Decis. Support Syst. 2014, 66, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrucci, D.; Baroud, H. A Review of Temporary Housing Management Modeling: Trends in Design Strategies, Optimization Models, and Decision-Making Methods. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, E.; Stokmans, M. Developing Strategic Targeted Interaction Design to Enhance Disaster Resilience of Vulnerable Communities. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 547–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.A.; Yazdani, R.; Fuente, A. de la Multi-Objective Interior Design Optimization Method Based on Sustainability Concepts for Post-Disaster Temporary Housing Units. Build. Environ. 2020, 173, 106742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgington, D.W. Planning for Earthquakes and Tsunamis: Lessons from Japan for British Columbia, Canada. Prog. Plan. 2022, 163, 100626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignoux, J.; Menéndez, M. Benefit in the Wake of Disaster: Long-Run Effects of Earthquakes on Welfare in Rural Indonesia. J. Dev. Econ. 2016, 118, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Han, S.; Gong, H.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, D. Disaster Resilience Assessment Based on the Spatial and Temporal Aggregation Effects of Earthquake-Induced Hazards. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 29055–29067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzica, C.; Cutini, V.; Bleil de Souza, C. Mind the Gap: State of the Art on Decision-Making Related to Post-Disaster Housing Assistance. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 53, 101975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, J.P.; Sandoval, V.; Jerath, M. The Influence of Land Tenure and Dwelling Occupancy on Disaster Risk Reduction. The Case of Eight Informal Settlements in Six Latin American and Caribbean Countries. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 5, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, W.M.; Rajakannu, G.; Kordestani Ghalenoei, N. Potential of Modular Offsite Construction for Emergency Situations: A New Zealand Study. Buildings 2022, 12, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.R.; Orchiston, C.H.R. Context, Culture, and Cordons: The Feasibility of Post-Earthquake Cordons Learned through a Case Study in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Earthq. Spectra 2023, 39, 2152–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloisio, A.; Rosso, M.M.; De Leo, A.M.; Fragiacomo, M.; Basi, M. Damage Classification after the 2009 L’Aquila Earthquake Using Multinomial Logistic Regression and Neural Networks. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 96, 103959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmaca, A.; Atmaca, N. Comparative Life Cycle Energy and Cost Analysis of Post-Disaster Temporary Housings. Appl. Energy 2016, 171, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Anwar, O.; El-Rayes, K.; Elnashai, A. An Automated System for Optimizing Post-Disaster Temporary Housing Allocation. Autom. Constr. 2009, 18, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, D.; Monteiro, D.; Branco, J.M.; Bologna, R.; Feio, A. The Role of Temporary Accommodation Buildings for Post-Disaster Housing Reconstruction. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2015, 30, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardena, T.; Ngo, T.; Mendis, P.; Aye, L.; Crawford, R. Time-Efficient Post-Disaster Housing Reconstruction with Prefabricated Modular Structures. Open House Int. 2014, 39, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutch, C. How Schools Build Community Resilience Capacity and Social Capital in Disaster Preparedness, Response and Recovery. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 92, 103735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Sakurai, M. Voluntary Isolation after the Disaster: The Loss of Community and Family in the Super Aged Society in Japan. J. Disaster Res. 2015, 10, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Mithraratne, N.; Zhang, H. Life-Time Performance of Post-Disaster Temporary Housing: A Case Study in Nanjing. Energy Build. 2016, 128, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oggioni, C.; Chelleri, L.; Forino, G. Challenges and Opportunities for Pre-Disaster Strategic Planning in Post-Disaster Temporary Housing Provision. Evidence from Earthquakes in Central Italy (2016–2017). Ital. J. Plan. Pract. 2019, 9, 96–129. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, P.; Porebska, A. Towards a Revised Framework for Participatory Planning in the Context of Risk. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lines, R.; Faure Walker, J.P.; Yore, R. Progression through Emergency and Temporary Shelter, Transitional Housing and Permanent Housing: A Longitudinal Case Study from the 2018 Lombok Earthquake, Indonesia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 75, 102959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.Y.; Baber, K.; Gattas, J.M. A Novel Tension Strap Connection for Rapid Assembly of Temporary Timber Structures. Eng. Struct. 2022, 262, 114320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, D.; Branco, J.M.; Feio, A. Temporary Housing after Disasters: A State of the Art Survey. Habitat. Int. 2013, 40, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.A.; De La Fuente, A.; Pons, O.; Mendoza Arroyo, C. A Decision Methodology for Determining Suitable Post-Disaster Accommodations: Reconsidering Effective Indicators for Decision-Making Processes. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2020, 17, 20180058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Han, Z. Emergency Management in China: Towards a Comprehensive Model? J. Risk Res. 2019, 22, 1425–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaddar, S.; Okada, N.; Choi, J.; Tatano, H. What Constitutes Successful Participatory Disaster Risk Management? Insights from Post-Earthquake Reconstruction Work in Rural Gujarat, India. Nat. Hazards 2017, 85, 111–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feather, C. Footing the Reconstruction Bill: An Appraisal of the Financial Architecture for Disaster Rebuilding in the United States of America. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 61, 102315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Li, J.; Li, D. Effect of Natural Hazards on the Household Financial Asset Allocation: Empirical Analysis Based on CHFS2019 Data. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1003877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, T.; Okada, S. Financial Imbalances in Regional Disaster Recovery Following Earthquakes-Case Study Concerning Housing-Cost Expenditures in Japan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundiers, K. Disasters as Opportunities for Sustainability: The Case of Christchurch, Aotearoa New Zealand. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1075–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharami, H.J.; Teimouri, S. Towards Sustainability in Post-Disaster Constructions with a Modular Prefabricated Structure. Aust. J. Struct. Eng. 2023, 24, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkoumas, I.; Mavridou, T.; Seymour, V.; Nanos, N. Post-Disaster Housing and Social Considerations. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 124, 105537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, T.; Welch, E.W.; Liu, B. Power of Social Relations: The Dynamics of Social Capital and Household Economic Recovery Post Wenchuan Earthquake. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 66, 102607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valderrama-Zurián, J.C.; Aguilar-Moya, R.; Melero-Fuentes, D.; Aleixandre-Benavent, R. A Systematic Analysis of Duplicate Records in Scopus. J. Inf. 2015, 9, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlin, C. Guidelines for Snowballing in Systematic Literature Studies and a Replication in Software Engineering. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, London, UK, 13–14 May 2014; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ayçin, E. Çok Kriterli Karar Verme: Bilgisayar Uygulamalı Çözümler; Nobel Akademik Yayıncılık: Ankara, Turkey, 2019; ISBN 9786057846174. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Z.; Tang, M.; Li, S. Research on Disaster Resilience of Earthquake-Stricken Areas in Longmenshan Fault Zone Based on GIS. Environ. Hazards 2020, 19, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasmen, T.; Sen, M.K.; Hossain, N.U.I.; Kabir, G. Modelling and Assessing Seismic Resilience of Critical Housing Infrastructure System by Using Dynamic Bayesian Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 428, 139349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Ludovico, D.; Capannolo, C.; d’Aloisio, G. The Toolkit Disaster Preparedness for Pre-Disaster Planning. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 96, 103889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KamacI-Karahan, E.; Kemeç, S. Residents’ Satisfaction in Post-Disaster Permanent Housing: Beneficiaries vs. Non-Beneficiaries. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 73, 102901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Peng, X.; Pang, R.; Li, L.; Song, Z.; Ye, H. Information Preference and Information Supply Efficiency Evaluation before, during, and after an Earthquake: Evidence from Songyuan, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrucci, D.V.; Hassan, M.M.; Baroud, H. Planning for Temporary Housing through Multicriteria Decision Analysis. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2022, 38, 541–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.A.; Farahzadi, L.; Pons, O. Assessing the Sustainability Index of Different Post-Disaster Temporary Housing Unit Configuration Types. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 42, 102806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin Hosseini, S.M.; De La Fuente, A.; Pons, O. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Method for Assessing the Sustainability of Post-Disaster Temporary Housing Units Technologies: A Case Study in Bam, 2003. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 20, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Anwar, O.; El-Rayes, K.; Elnashai, A. Multi-Objective Optimization of Temporary Housing for the 1994 Northridge Earthquake. Proc. J. Earthq. Eng. 2008, 12, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Wang, N. Stochastic Post-Disaster Functionality Recovery of Community Building Portfolios II: Application. Struct. Saf. 2017, 69, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahanvati, M.; McEvoy, D.; Iyer-Raniga, U. Inclusive and Resilient Shelter Guide: Accounting for the Needs of Informal Settlements in Solomon Islands. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2023, 14, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabacak, V.; Özkaymak, C.; Sozbilir, H.; Tatar, O.; Aktug, B.; Ozdag, O.C.; Cakır, R.; Aksoy, E.; Kocbulut, F.; Softa, M.; et al. The 2023 Pazarcık (Kahramanmaraş, Türkiye) Earthquake (Mw 7.7): Implications for Surface Rupture Dynamics along the East Anatolian Fault Zone. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 2023, 180, jgs2023-020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogabe, T.; Maki, N. Do Disasters Provide an Opportunity for Regional Development and Change the Societal Trend of Impacted Communities?: Case Study on the 1995 Kobe Earthquake. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 67, 102648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidvar, B.; Zafari, H.; Khakpour, M. Evaluation of Public Participation in Reconstruction of Bam, Iran, after the 2003 Earthquake. Nat. Hazards 2011, 59, 1397–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubokura, M.; Takita, M.; Matsumura, T.; Hara, K.; Tanimoto, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Hamaki, T.; Oiso, G.; Kami, M.; Okawada, T.; et al. Changes in Metabolic Profiles After the Great East Japan Earthquake: A Retrospective Observational Study. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshikata, C.; Watanabe, M.; Ishida, M.; Kobayashi, S.; Kubosaki, A.; Yamazaki, A.; Konuma, R.; Hashimoto, K.; Kobayashi, N.; Kaneko, T.; et al. Increase in Asthma Prevalence in Adults in Temporary Housing after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 50, 101696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, A.; Sato, S.; Sugiura, M.; Abe, T.; Imamura, F. Personality Traits and Types of Housing Recovery after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deelstra, A.; Bristow, D.N. Assessing the Effectiveness of Disaster Risk Reduction Strategies on the Regional Recovery of Critical Infrastructure Systems. Resilient Cities Struct. 2023, 2, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.; Haukaas, T. The Effect of Resource Constraints on Housing Recovery Simulations. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 55, 102071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.