Investigation on the Fresh and Mechanical Properties of Low Carbon 3D Printed Concrete Incorporating Sugarcane Bagasse Ash and Microfibers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedure

2.1. Materials and Mix Design

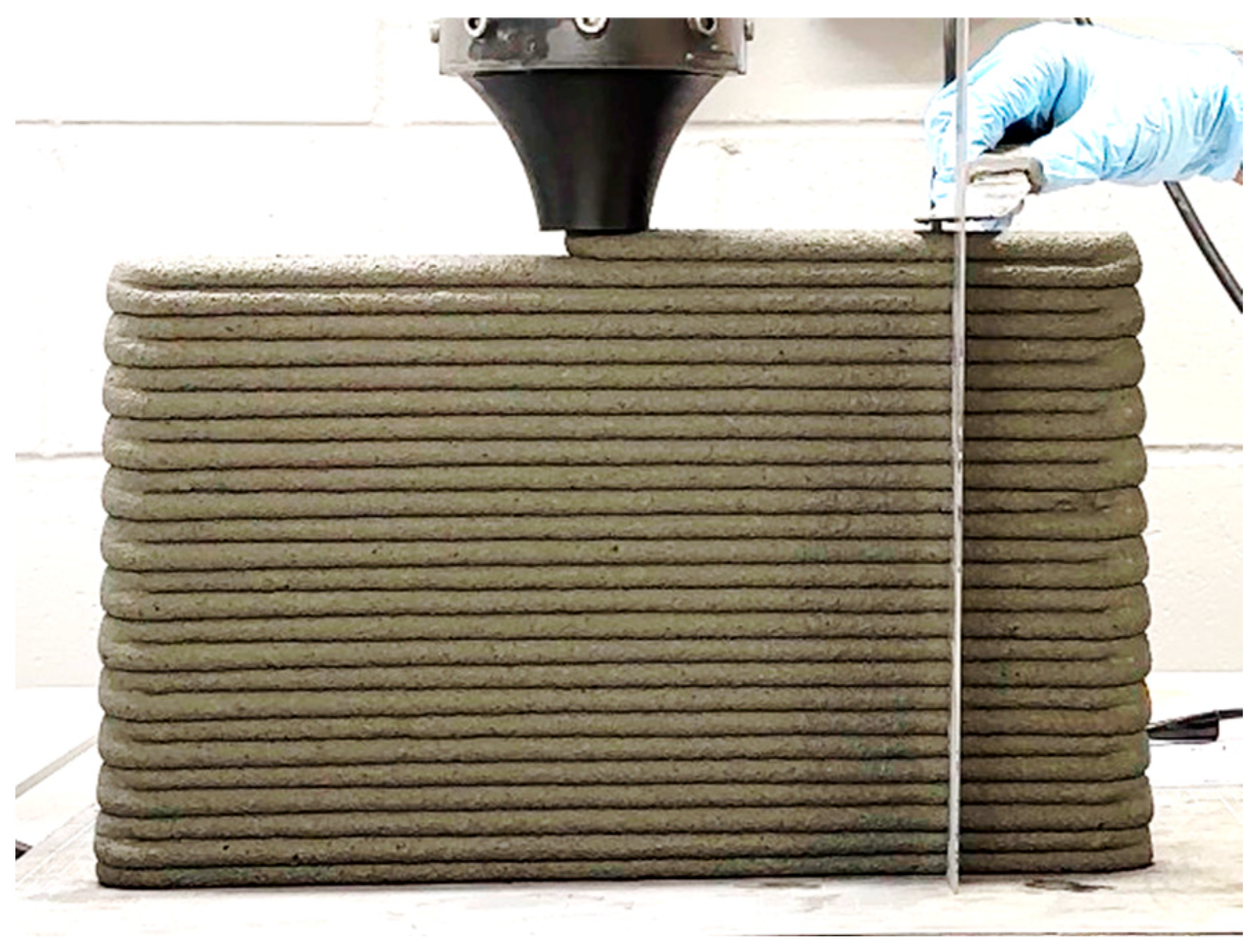

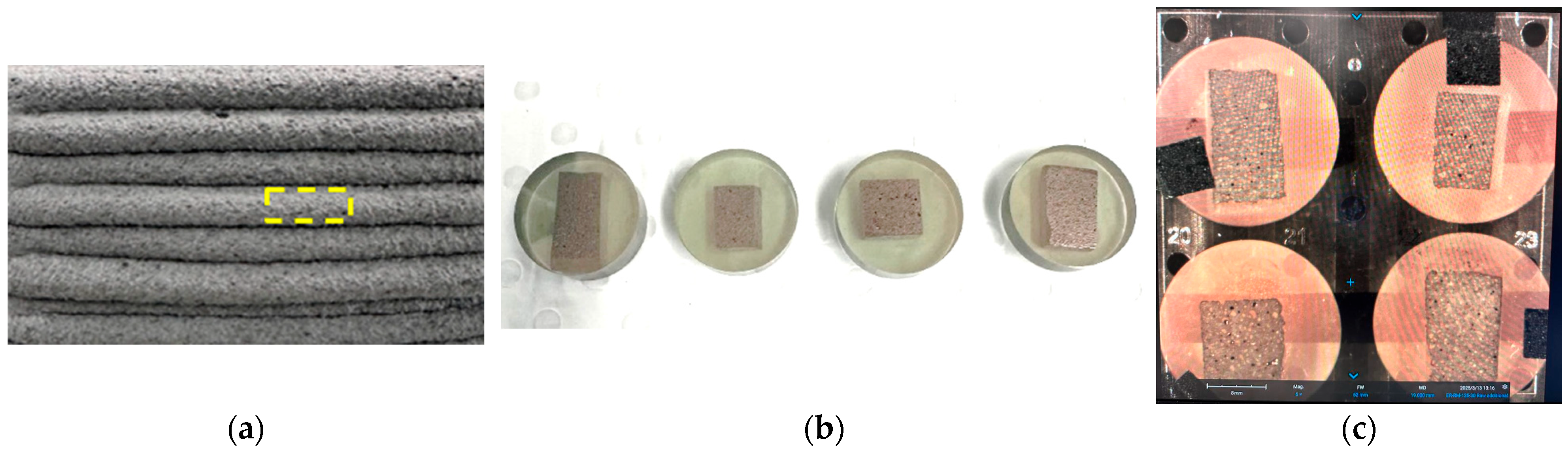

2.2. Mixing and Printing Procedure

2.3. Fresh Properties Test

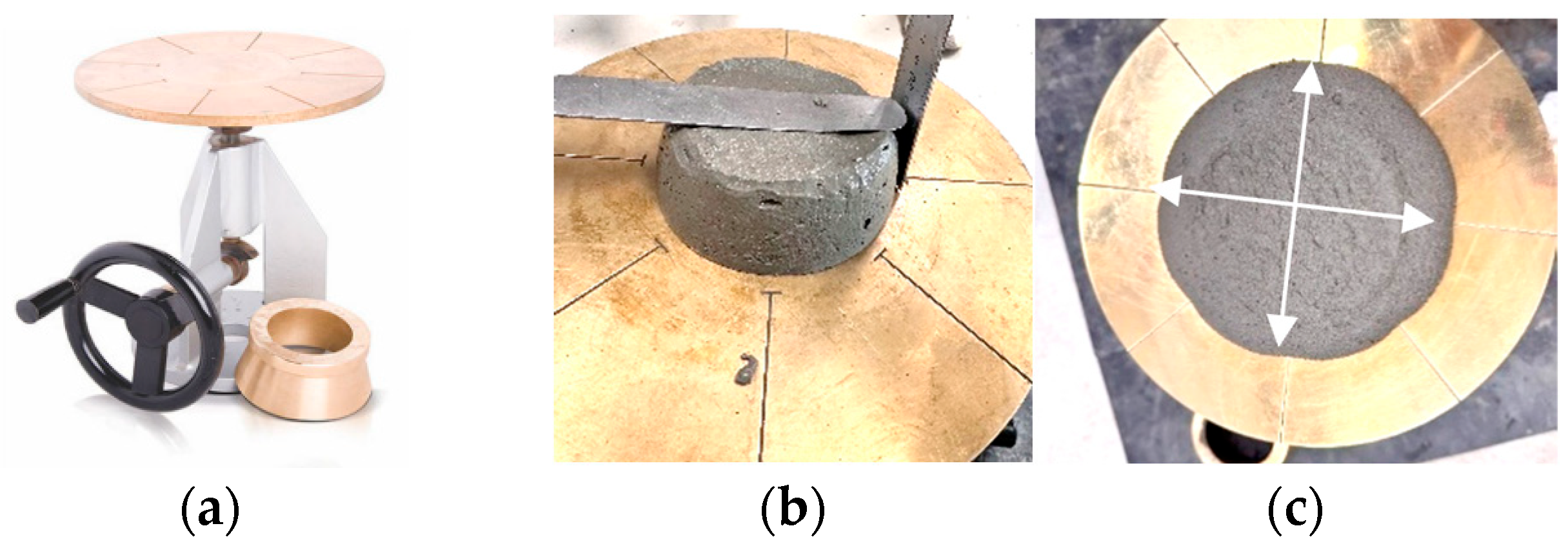

2.3.1. Mini Slump and Flow Table Test

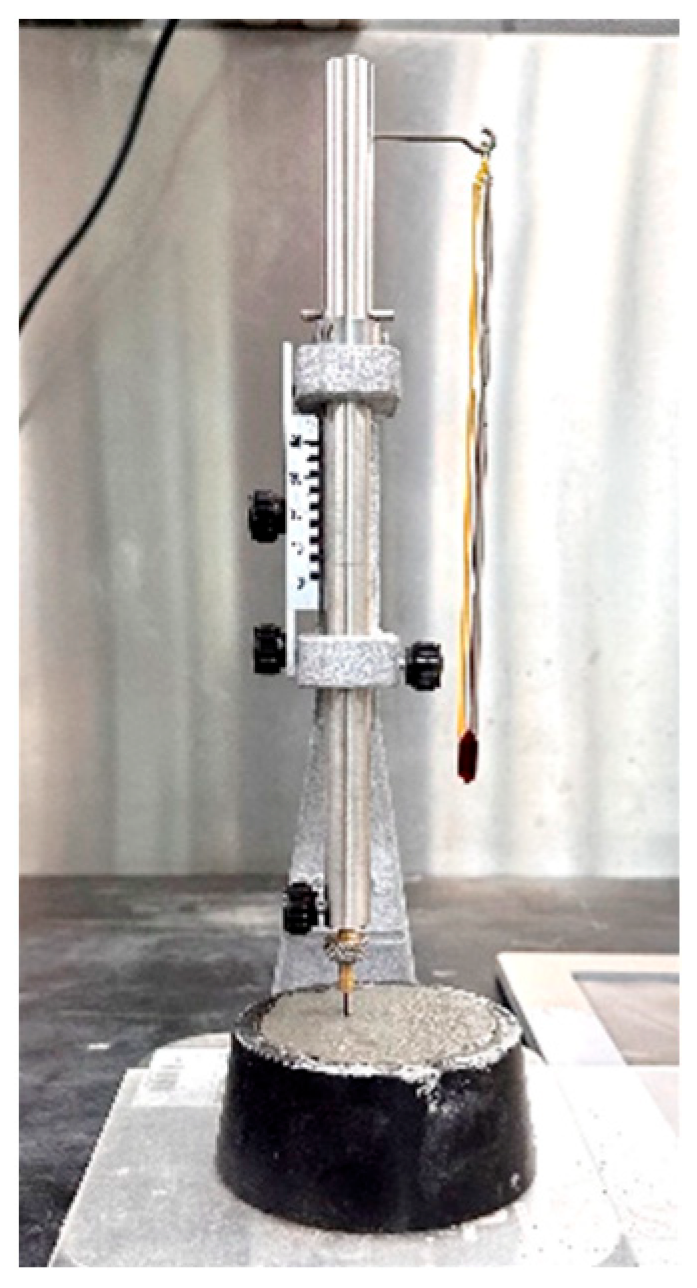

2.3.2. Setting Time

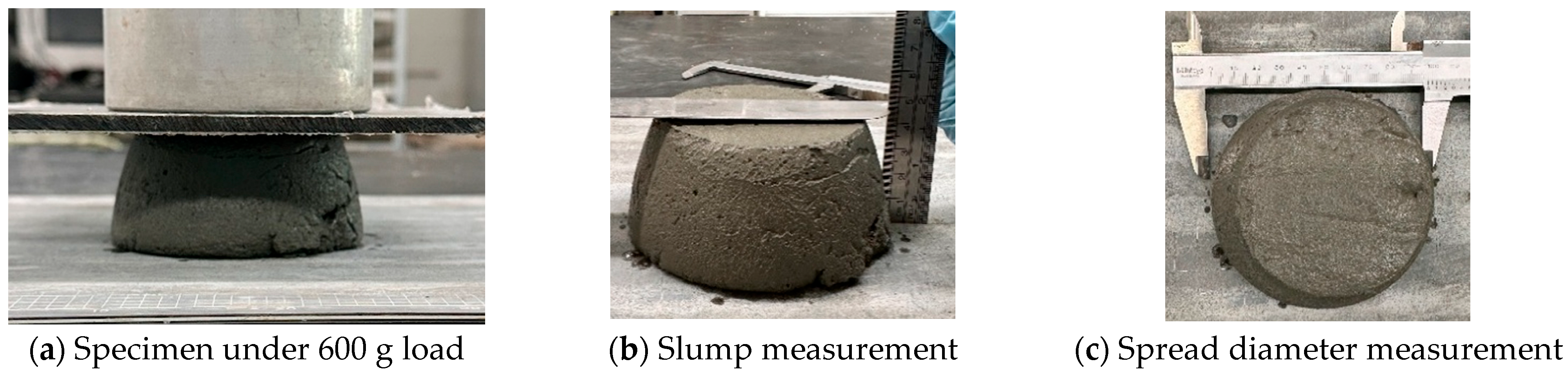

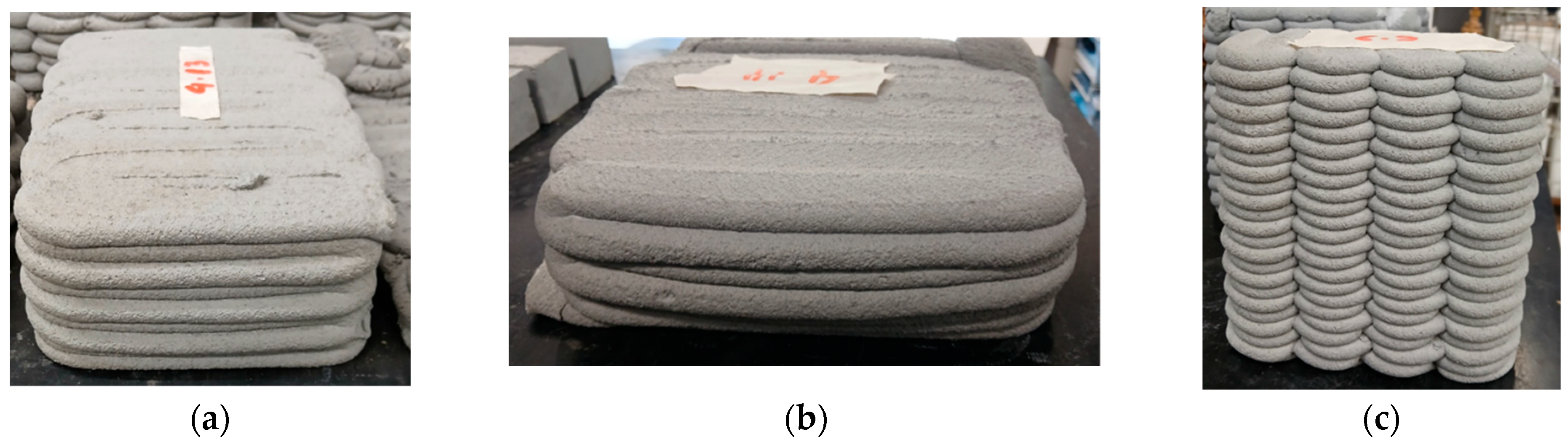

2.3.3. Shape Retention and Buildability

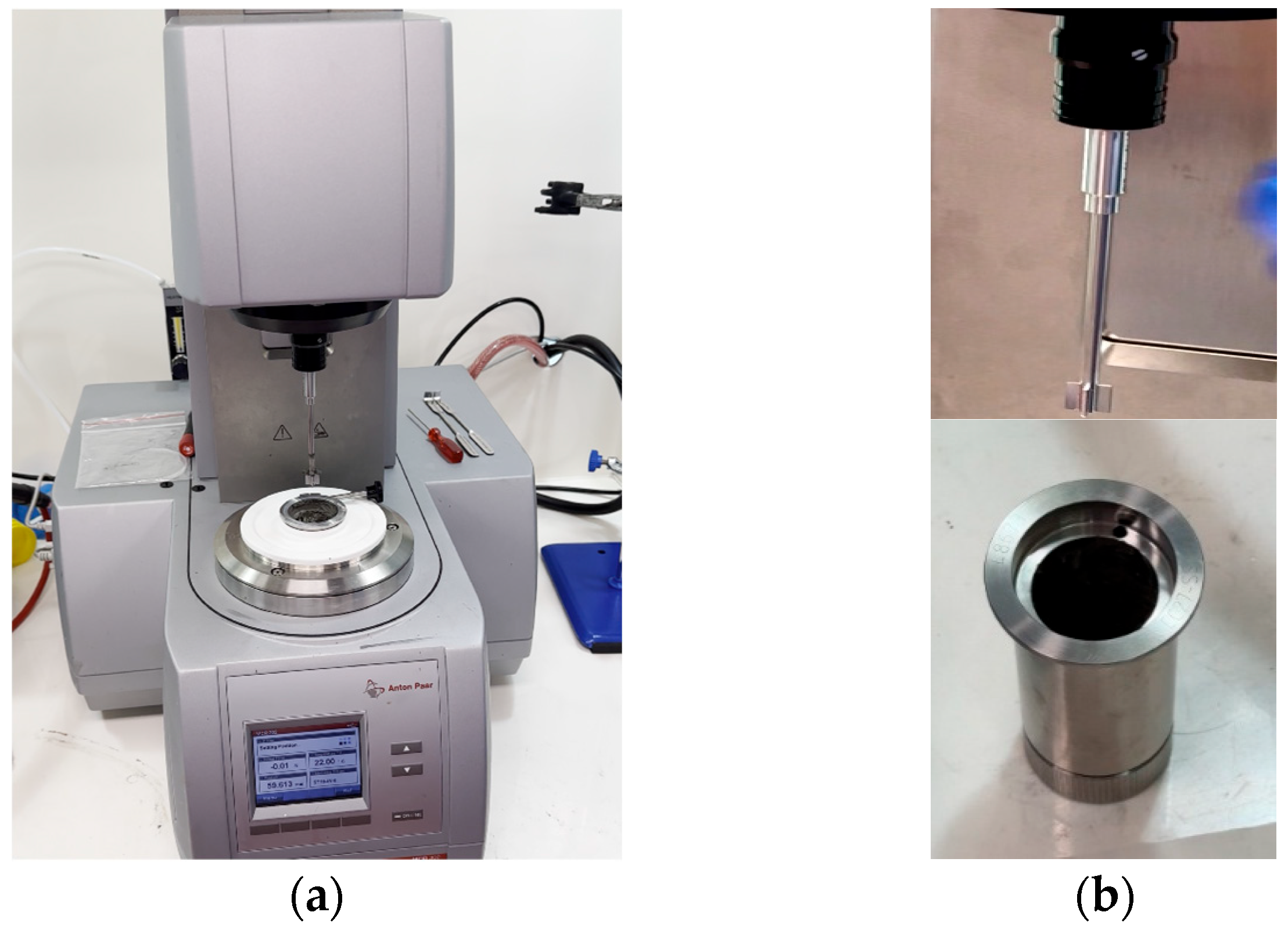

2.3.4. Rheology Test

2.4. Mechanical Properties

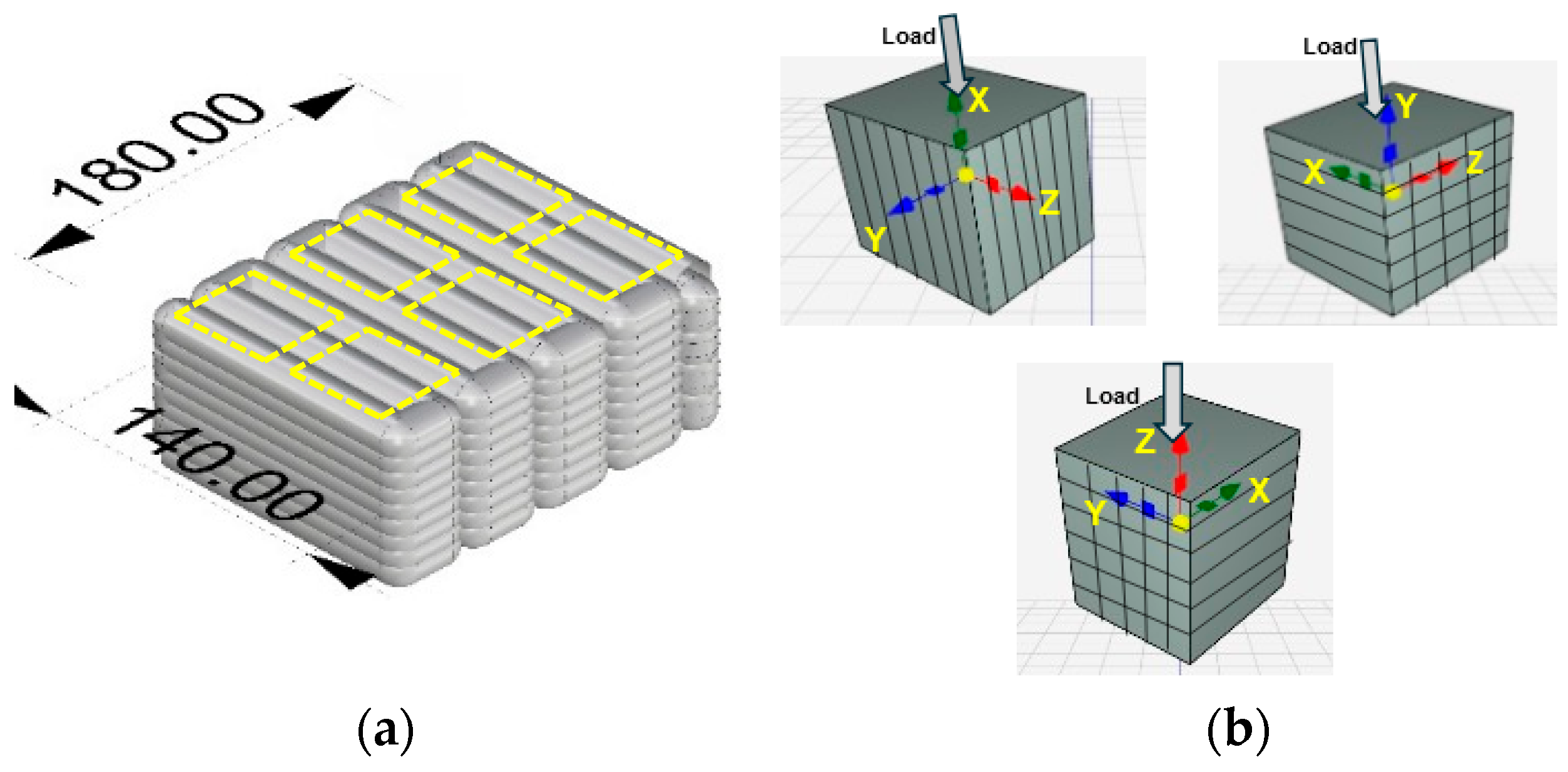

2.4.1. Compressive Strength

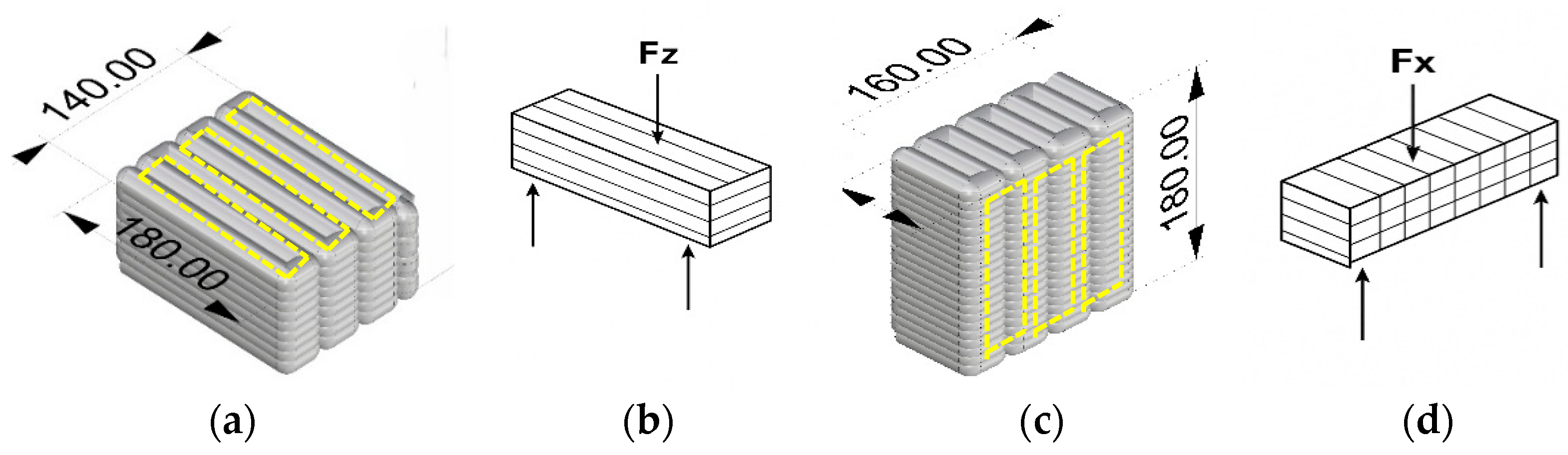

2.4.2. Flexural Strength Test

2.4.3. Interlayer Bond Strength Test

2.5. Microstructural Investigation

3. Results

3.1. Fresh Properties

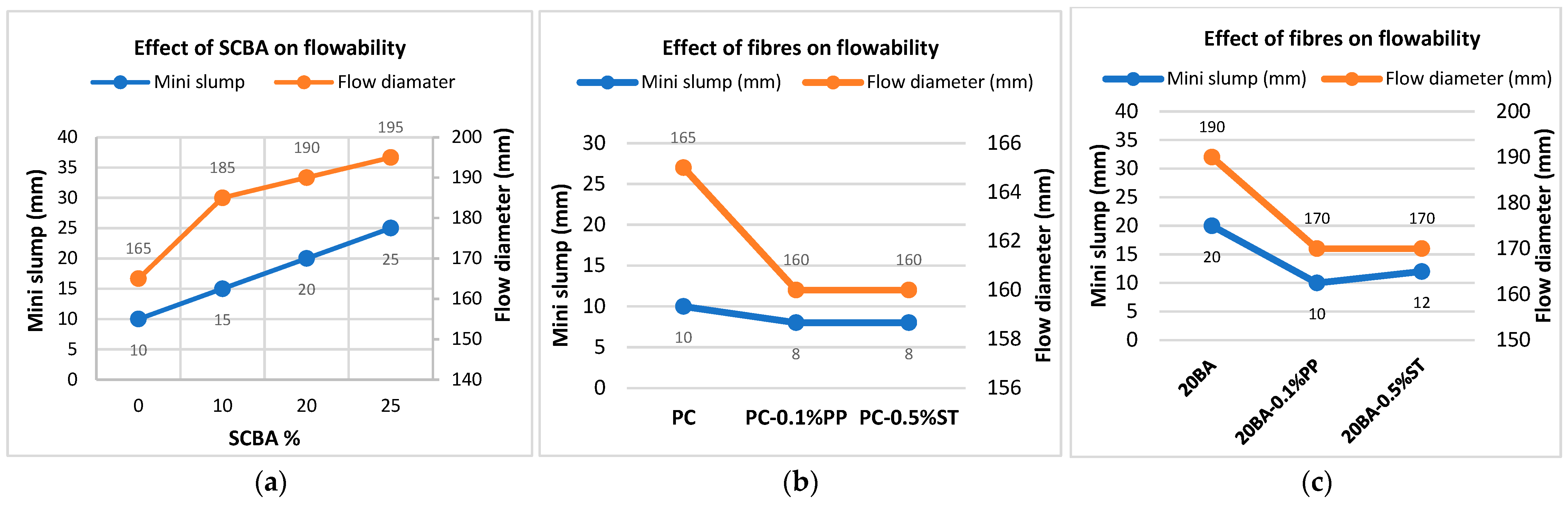

3.1.1. Mini Slump and Flow Diameter

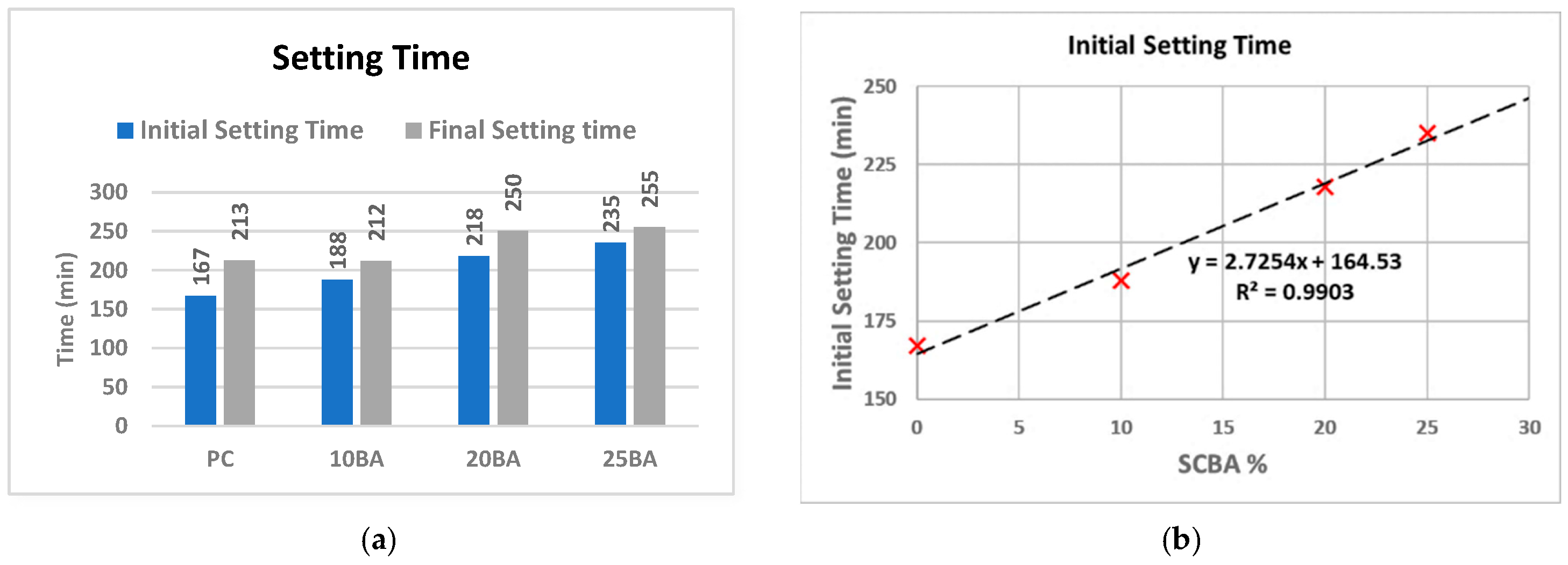

3.1.2. Setting Time

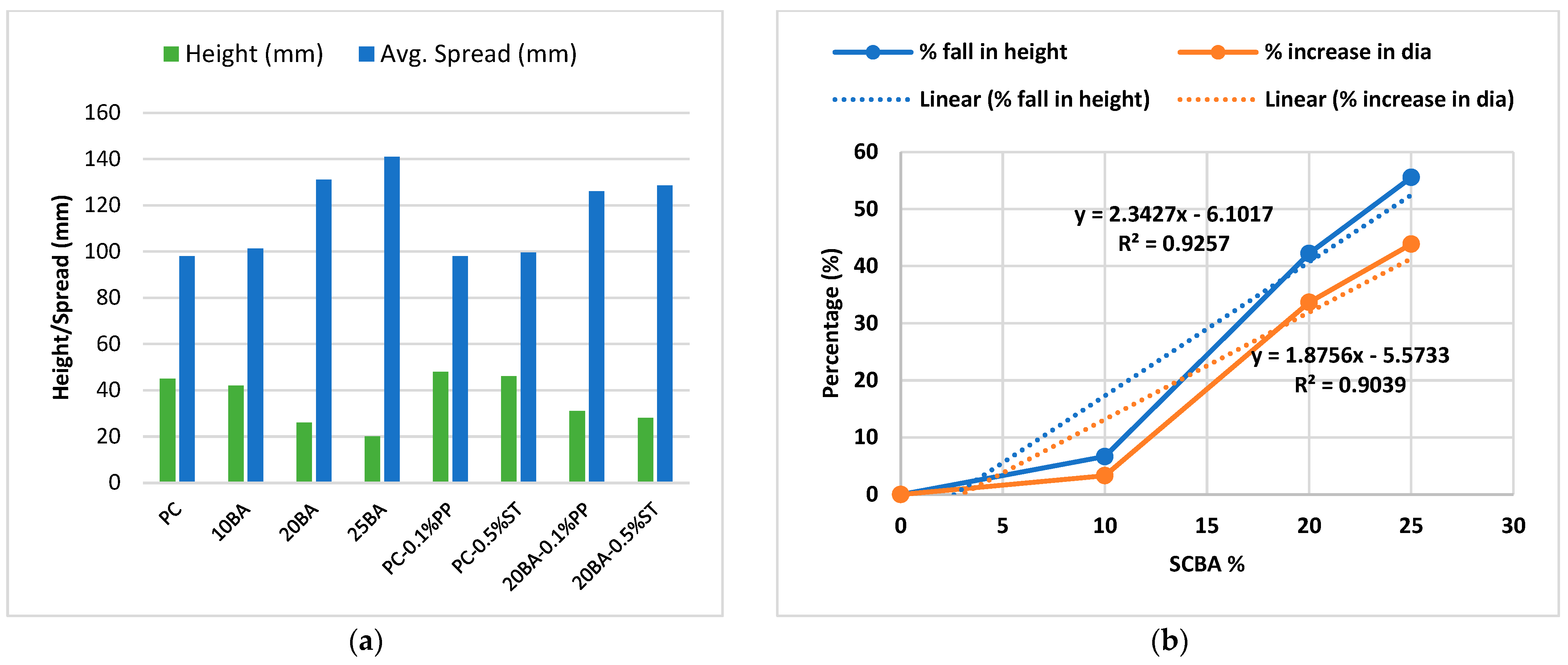

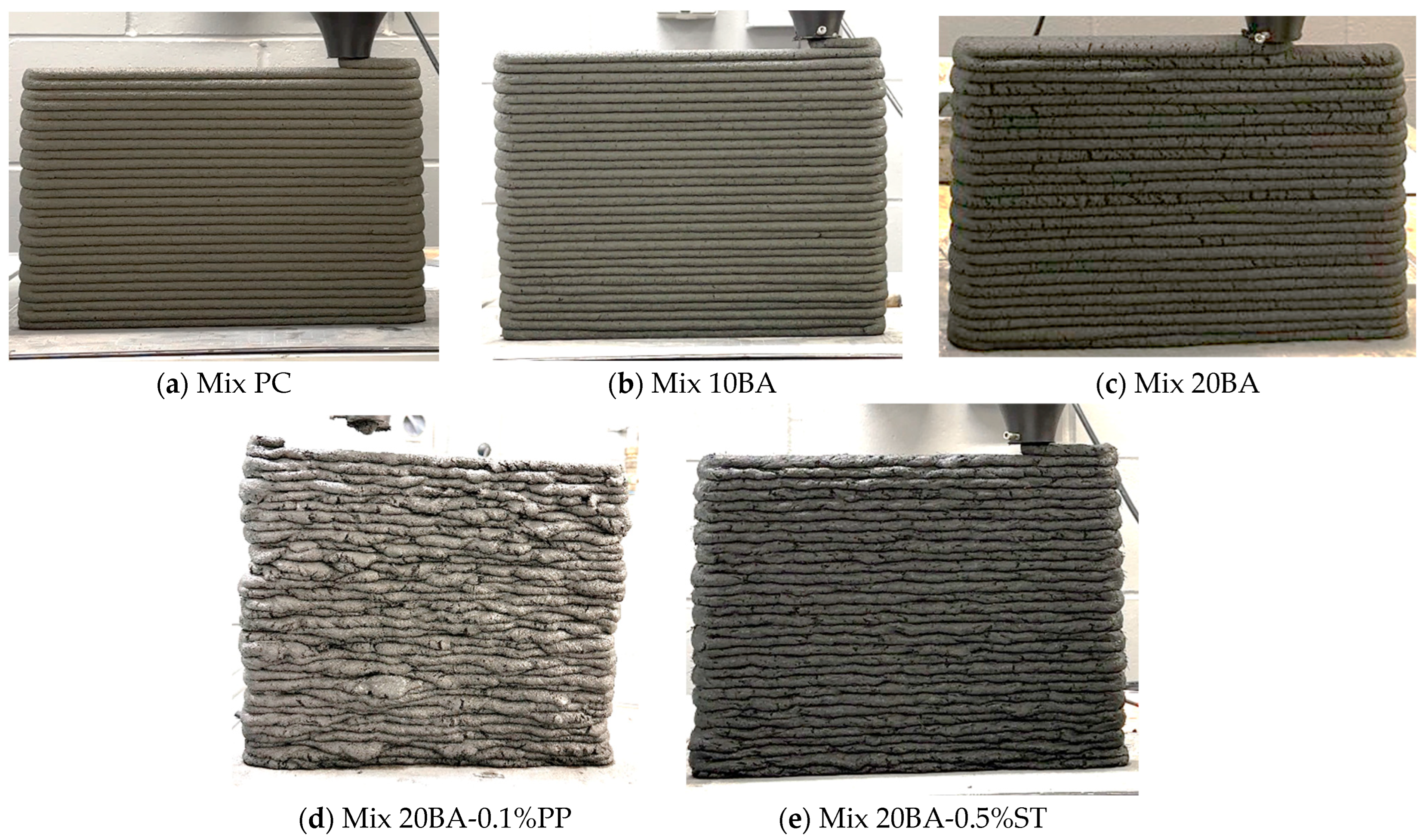

3.1.3. Shape Retention and Buildability

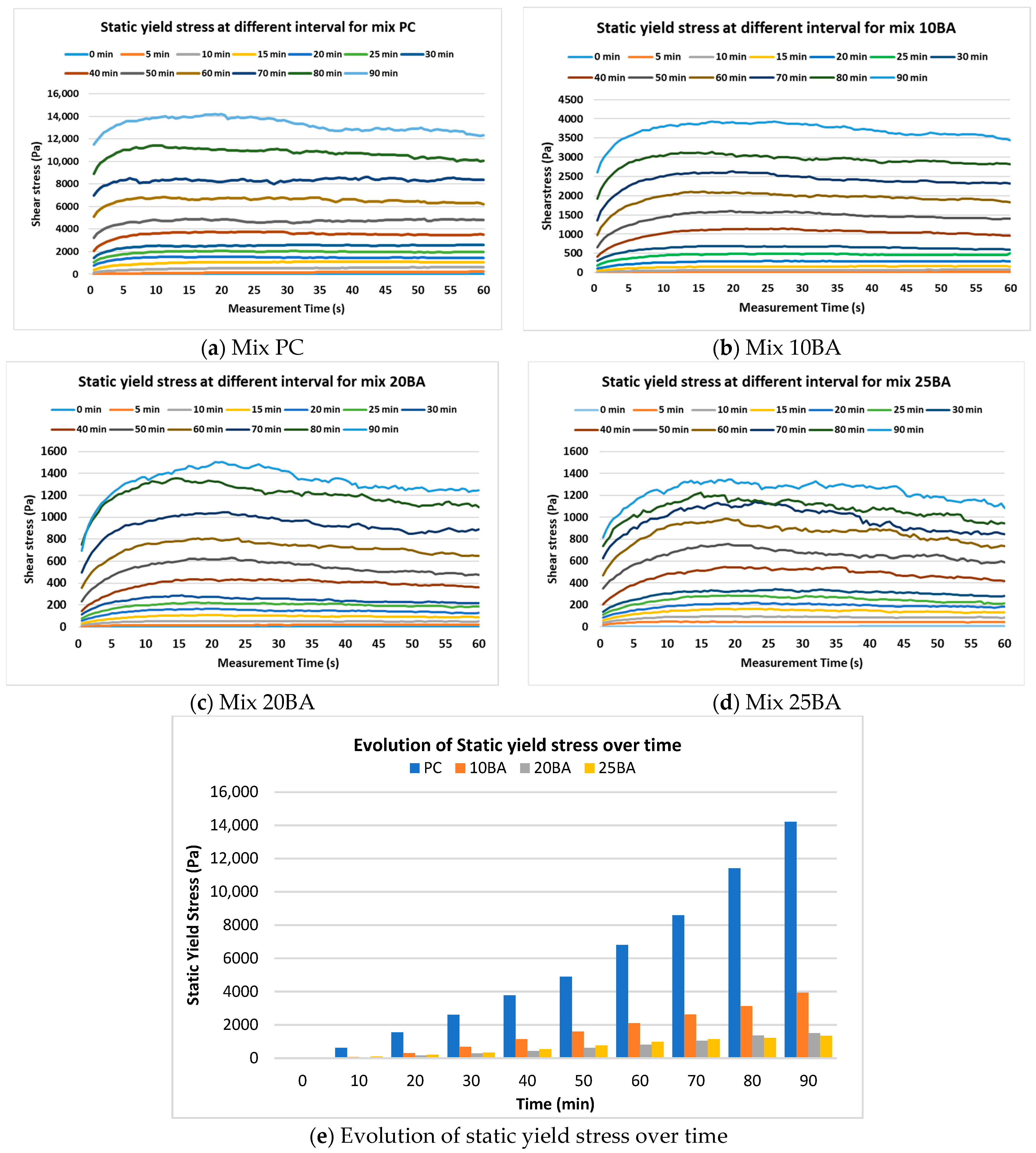

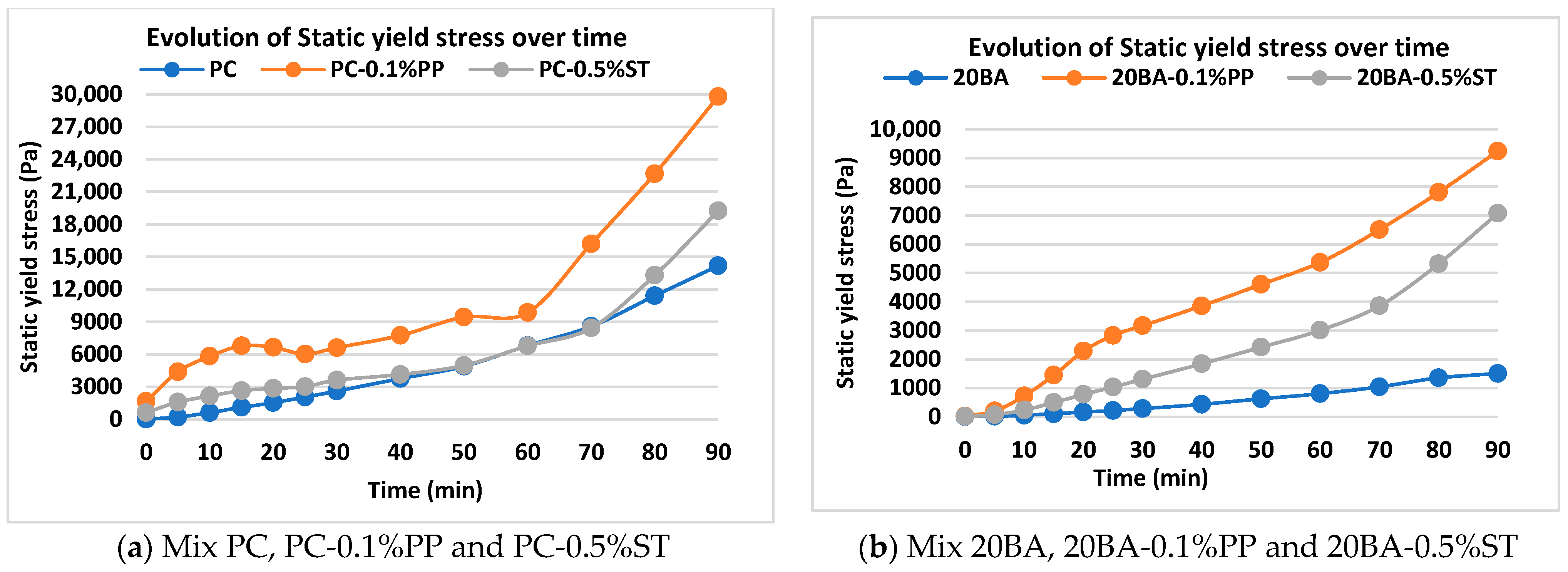

3.1.4. Rheology Test

3.2. Mechanical Properties

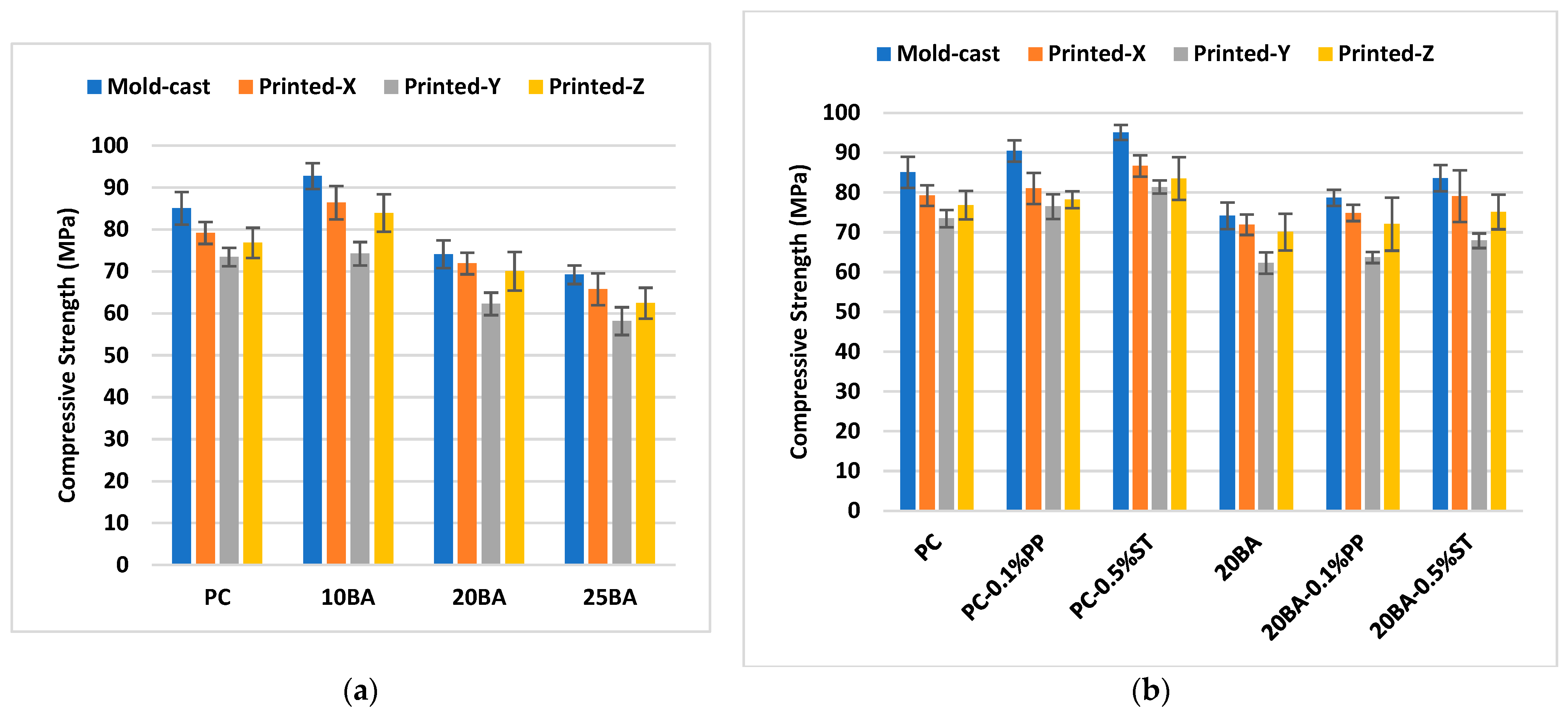

3.2.1. Compressive Strength

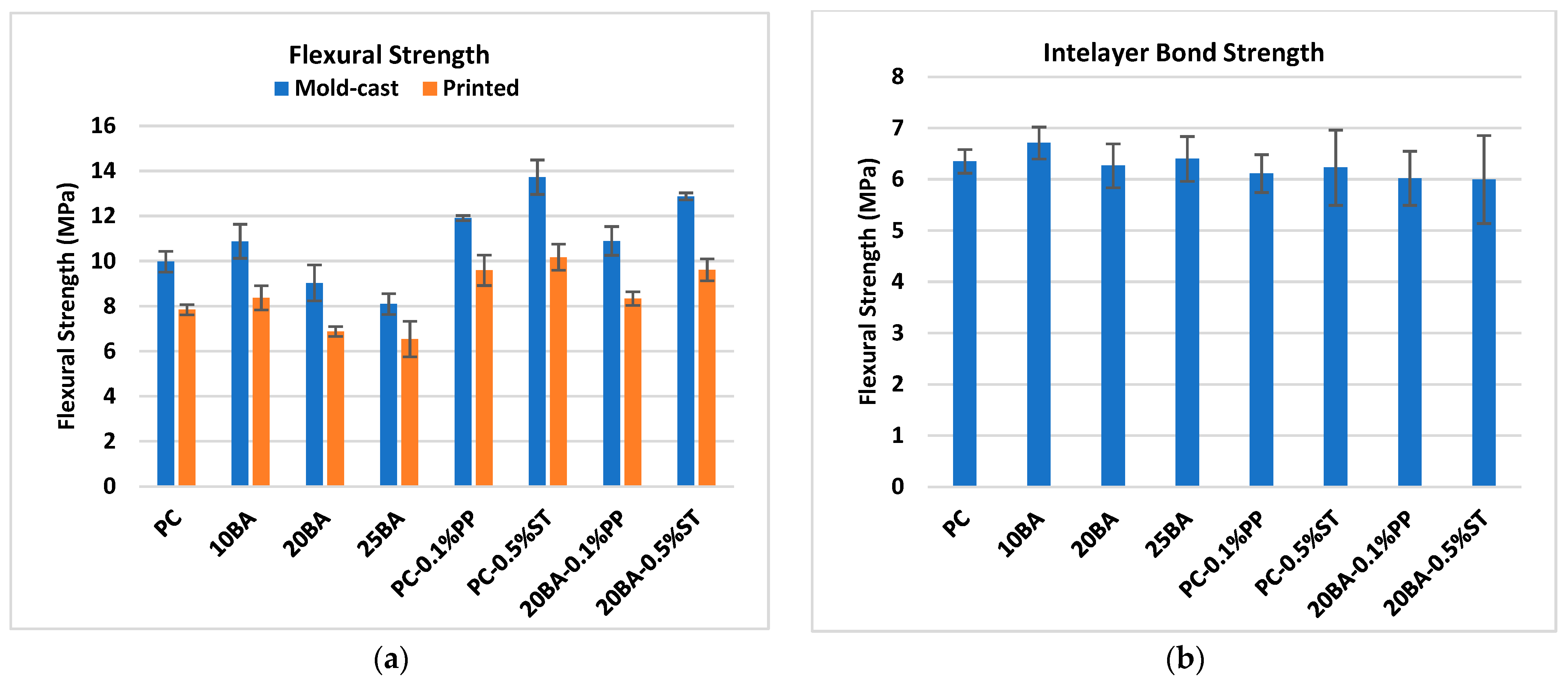

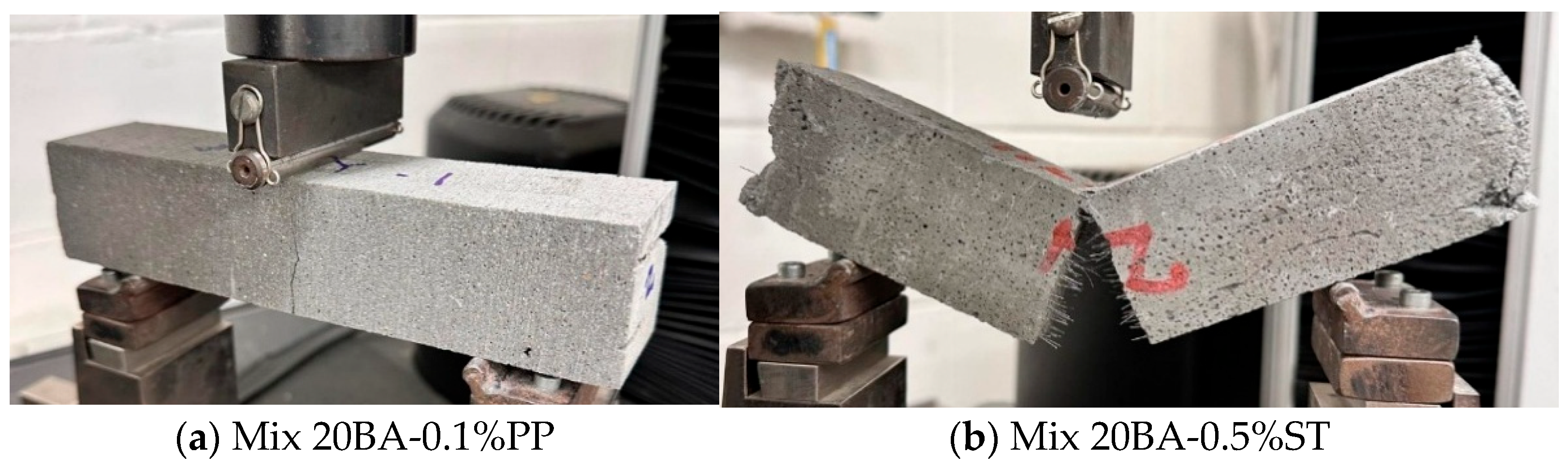

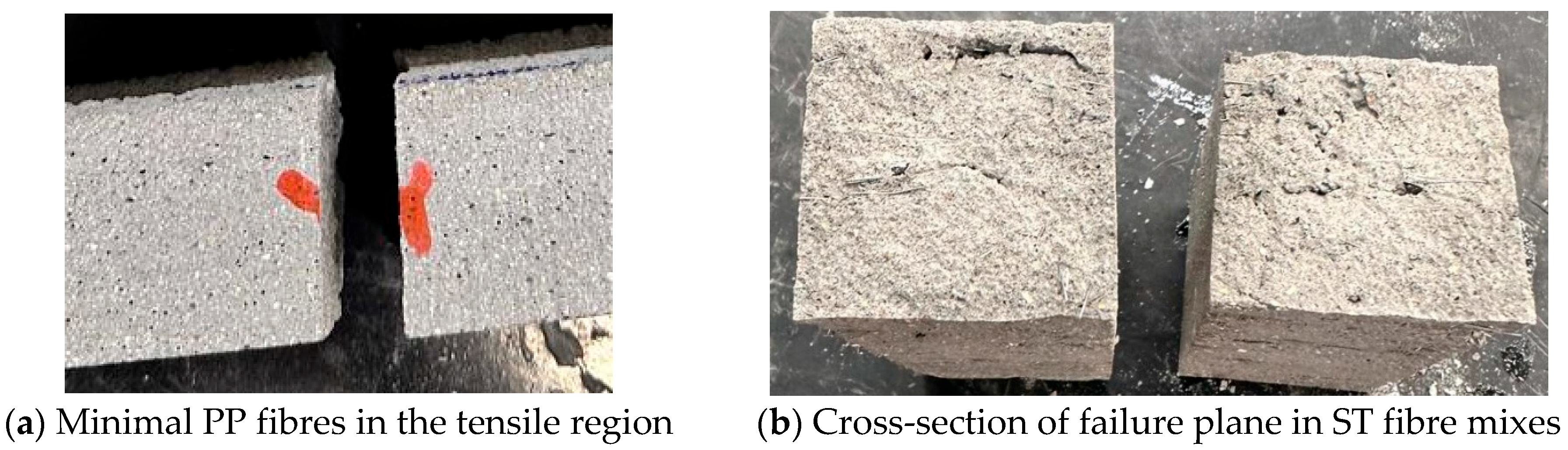

3.2.2. Flexural Strength

3.2.3. Interlayer Bond Strength

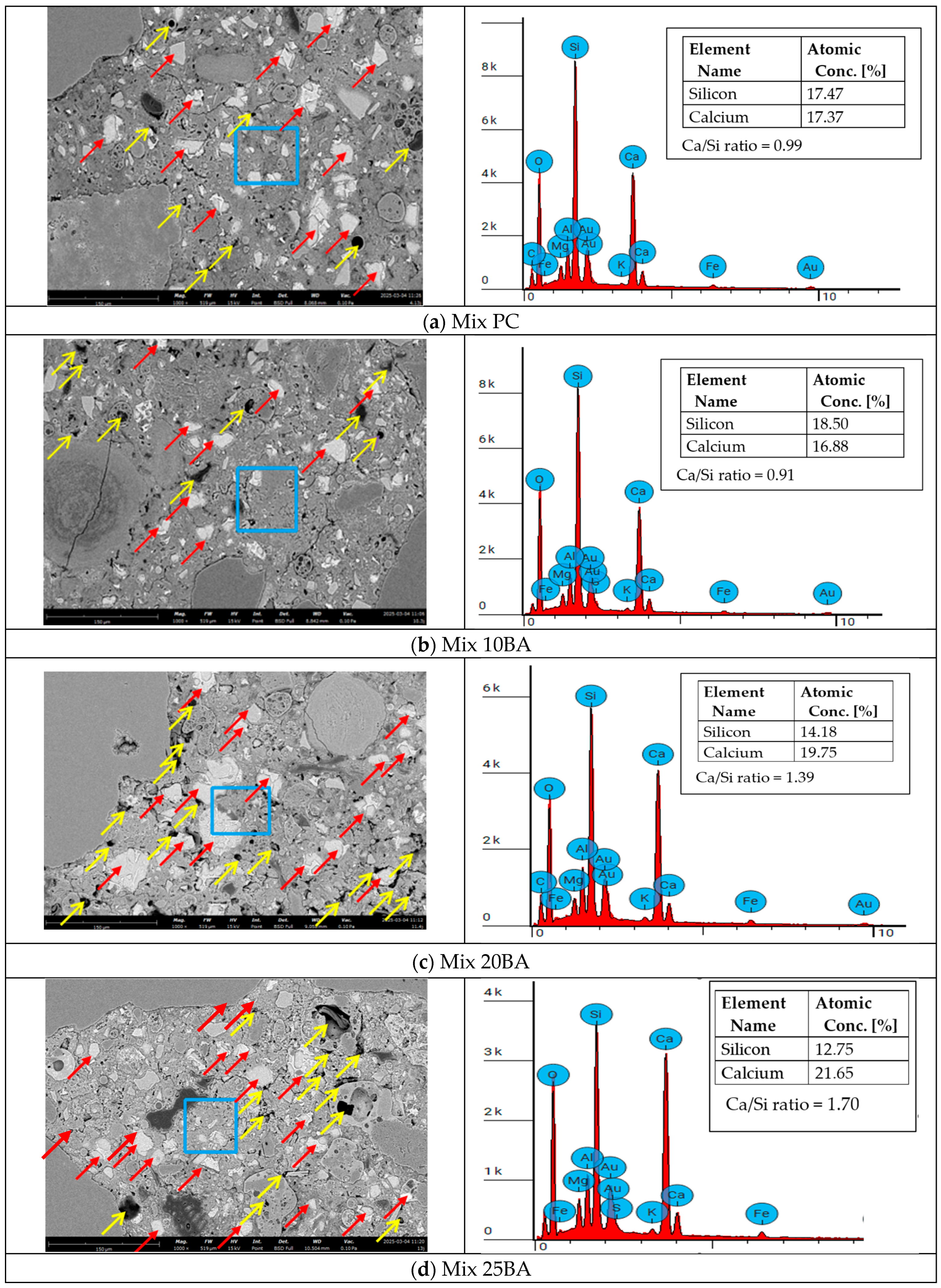

3.3. Microstructural Investigation

4. Discussions

4.1. Printability Characteristics of SCBA-Based Mixes with Microfibres

4.2. Impact of SCBA and Microfibres on Mechanical Performance

4.3. Applications, Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, H.; Cai, Z.; Tang, S.; Li, W.; Lin, Y.; Liao, Y.; Wang, L. Influential Mechanism Analysis of Modified Absorbent Polymer in Roller-Compacted Cementitious Materials. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2026, 38, 04025538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Y.; Long, Y.; Tang, S. Simulation of low-heat Portland cement permeability and thermal conductivity using thermodynamics. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Transp. 2024, 178, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, G.H. A review of “3D concrete printing”: Materials and process characterization, economic considerations and environmental sustainability. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 66, 105863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, K.; Fawzia, S.; Zahra, T.; Teixeira, M.B.F.; Sulong, N.H.R. Advancement in Sustainable 3D Concrete Printing: A Review on Materials, Challenges, and Current Progress in Australia. Buildings 2024, 14, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Cai, Z.; Deng, F.; Ye, J.; Wang, K.; Tang, S. Hydration behavior and thermodynamic modelling of ferroaluminate cement blended with steel slag. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Li, Z.; Long, Q.; Tang, S.; Zhao, Y. Study on the properties of autoclaved aerated concrete with high content concrete slurry waste. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 17, 100338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Li, H.; Sun, X.; Zhao, K.; Wang, Y. Effect of FA and GGBFS on compressive strength, rheology, and printing properties of cement-based 3D printing material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 339, 127685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Taqa, A.; Mohsen, M.O.; Aburumman, M.O.; Naji, K.; Taha, R.; Senouci, A. Nano-fly ash and clay for 3D-Printing concrete buildings: A fundamental study of rheological, mechanical and microstructural properties. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 92, 109718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, K.-C.; Chi, M.; Yeih, W.; Huang, R. Influence of Slag/Fly Ash as Partial Cement Replacement on Printability and Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed Concrete. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahabizadeh, B.; Pereira, J.; Gonçalves, C.; Pereira, E.N.B.; Cunha, V.M.C.F. Influence of the printing direction and age on the mechanical properties of 3D printed concrete. Mater. Struct. 2021, 54, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, E.; Ciza, B.; Yalçınkaya, Ç.; Felekoğlu, B.; Yazıcı, H.; Çopuroğlu, O. A comparative study on the effectiveness of fly ash and blast furnace slag as partial cement substitution in 3D printable concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 108, 112841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Wang, T.; Chen, X.; Shen, W.; Shi, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, P. Study of 3D printed concrete with low-carbon cementitious materials based on its rheological properties and mechanical performances. J. Sustain. Cem. Mater. 2023, 12, 832–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.-C.; Wang, W.-C.; Lee, M.-G.; Huang, C.-Y. Development of sustainable 3D printing concrete materials: Impact of natural minerals and wastes at high replacement ratios. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 113, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhlaq, H.; Peng, T.; Ajmal, M.M.; Khan, M.S.; Riaz, M. Impact of GGBS on the rheology and mechanical behavior of pumpable concrete. Front. Mater. 2025, 12, 1614951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zat, T.; Schuster, S.L.; Duarte, E.S.; Daudt, N.D.F.; Cruz, R.C.D.; Rodríguez, E.D. Rheological properties of high-performance concrete reinforced with microfibers and their effects on 3D printing process. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 105, 112406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, Q.; Lombois-Burger, H.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Niu, G.; Zhang, Y. Pore structure, internal relative humidity, and fiber orientation of 3D printed concrete with polypropylene fiber and their relation with shrinkage. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 61, 105250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Geng, J.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, G. Comparative analysis of polypropylene, basalt, and steel fibers in 3D printed concrete: Effects on flowability, printabiliy, rheology, and mechanical performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 465, 140098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.; Tran, P.; Sanjayan, J. Steel fibres reinforced 3D printed concrete: Influence of fibre sizes on mechanical performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 250, 118785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Ren, Q. Mechanical anisotropy of ultra-high performance fibre-reinforced concrete for 3D printing. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 125, 104310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Sugarcane, Experimental Regional Estimates Using New Data Sources and Methods. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/industry/agriculture/sugarcane-experimental-regional-estimates-using-new-data-sources-and-methods/latest-release (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- de Sande, V.T.; Sadique, M.; Pineda, P.; Bras, A.; Atherton, W.; Riley, M. Potential use of sugar cane bagasse ash as sand replacement for durable concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 39, 102277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, E.; Clark, M.W.; Lake, N. Sugar cane bagasse ash from a high efficiency co-generation boiler: Applications in cement and mortar production. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 128, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Quero, V.; León-Martínez, F.; Montes-García, P.; Gaona-Tiburcio, C.; Chacón-Nava, J. Influence of sugar-cane bagasse ash and fly ash on the rheological behavior of cement pastes and mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 40, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahurudeen, A.; Kanraj, D.; Dev, V.G.; Santhanam, M. Performance evaluation of sugarcane bagasse ash blended cement in concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2015, 59, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, L.C.d.A.; dos Anjos, M.A.S.; de Sá, M.V.V.A.; de Souza, N.S.L.; de Farias, E.C. Effect of high temperatures on self-compacting concrete with high levels of sugarcane bagasse ash and metakaolin. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 248, 118715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Ji, T.; Huang, P.; Fu, T.; Zheng, X.; Xu, Q. Use of sugar cane bagasse ash in ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) as cement replacement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 317, 125881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quedou, P.G.; Wirquin, E.; Bokhoree, C. Sustainable concrete: Potency of sugarcane bagasse ash as a cementitious material in the construction industry. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 14, e00545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobuz, H.R.; Imran, A.; Datta, S.D.; Jabin, J.A.; Aditto, F.S.; Hasan, N.M.S.; Hasan, M.; Zaman, A.A.U. Assessing the influence of sugarcane bagasse ash for the production of eco-friendly concrete: Experimental and machine learning approaches. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 20, e02839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadesh, P.; Murthy, A.R.; Murugesan, R. Effect of processed sugar cane bagasse ash on mechanical and fracture properties of blended mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 262, 120846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jittin, V.; Bahurudeen, A. Evaluation of rheological and durability characteristics of sugarcane bagasse ash and rice husk ash based binary and ternary cementitious system. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 317, 125965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankeeth, S.; Prabhath, A.; Damruwan, H.; Herath, H.; Priyadarshana, H.; Kumara, S.; Lewangamage, C.; Koswattage, K. Optimizing mechanical properties of concrete using sugarcane bagasse ash. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 105968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, U.; Sarir, M.; Khan, D.; Haq, I.U.; Khawaja, M.W.A.; Mahmood, K. Effect of Sugar Cane Bagasse Ash Incorporated as Viscosity Modifying Agent on Fresh, Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Self-Compacting Concrete. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2025, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupim, R.V.; Júnior, J.A.T.L.; Mesquita, L.C.; Marques, M.G.; de Azevedo, A.R.G.; Marvila, M.T. Rheological and Mechanical properties of mortars made with recycled sugarcane bagasse ash. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 3546–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, J.d.S.A.; de França, M.J.S.; Júnior, N.S.d.A.; Ribeiro, D.V. Effects of adding sugarcane bagasse ash on the properties and durability of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 266, 120959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, M.; Teixeira, J.; Alves, J.L.; Pessoa, S.; Guimarães, A.S.; Rangel, B. Potential Use of Sugarcane Bagasse Ash in Ce-Mentitious Mortars for 3D Printing; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Chourasia, A.; Pal, B.; Kapoor, A. Influence of Printing Direction and Interlayer Printing Time on the Bond Characteristics and Hardened Mechanical Properties of Agro-Industrial Waste–Based 3D Printed Concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2025, 37, 04025065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Piedrahita, J.; Montes-García, P.; Mendoza-Rangel, J.; Calvo, H.L.; Valdez-Tamez, P.; Martínez-Reyes, J. Mechanical and durability properties of mortars prepared with untreated sugarcane bagasse ash and untreated fly ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 105, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, S.M.S.; Munir, M.J.; Patnaikuni, I.; Wu, Y.-F. Pozzolanic reaction of sugarcane bagasse ash and its role in controlling alkali silica reaction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 148, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F.C.; Sales, A.; Moretti, J.P.; Mendes, P.C. Sugarcane bagasse ash sand (SBAS): Brazilian agroindustrial by-product for use in mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 82, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colyn, M.; van Zijl, G.; Babafemi, A.J. Fresh and strength properties of 3D printable concrete mixtures utilising a high volume of sustainable alternative binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 419, 135474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AS 3972; General Purpose and Blended Cements. Australian Standard: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2010.

- AS 3582.1; Supplementary Cementitious Materials, Part 1: Fly Ash. Australian Standard: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2016.

- AS 3582.2; Supplementary Cementitious Materials, Part 2: Slag—Ground Granulated Blast-Furnace. Australian Standard: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2016.

- AS 3582.3; Supplementary Cementitious Materials, Part 3: Amorphous Silica. Australian Standard: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2016.

- Abdalla, T.A.; Koteng, D.O.; Shitote, S.M.; Matallah, M. Mechanical and durability properties of concrete incorporating silica fume and a high volume of sugarcane bagasse ash. Results Eng. 2022, 16, 100666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahurudeen, A.; Santhanam, M. Influence of different processing methods on the pozzolanic performance of sugarcane bagasse ash. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2015, 56, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukzon, S.; Chindaprasirt, P. Utilization of bagasse ash in high-strength concrete. Mater. Des. 2012, 34, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Parada, V.; Jiménez-Quero, V.G.; Valdez-Tamez, P.L.; Montes-García, P. Characterization and use of an untreated Mexican sugarcane bagasse ash as supplementary material for the preparation of ternary concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 157, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrant, W.E.; Babafemi, A.J.; Kolawole, J.T.; Panda, B. Influence of Sugarcane Bagasse Ash and Silica Fume on the Mechanical and Durability Properties of Concrete. Materials 2022, 15, 3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, L.R.C.; Junior, J.F.T.; Costa, L.M.; Bezerra, A.C.D.S.; Cetlin, P.R.; Aguilar, M.T.P. Influence of quartz powder and silica fume on the performance of Portland cement. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jittin, V.; Minnu, S.; Bahurudeen, A. Potential of sugarcane bagasse ash as supplementary cementitious material and comparison with currently used rice husk ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 273, 121679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahul, A.; Santhanam, M.; Meena, H.; Ghani, Z. 3D printable concrete: Mixture design and test methods. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 97, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Master Builders Solutions. MasterFiber M 018 Monofilament Micro Polypropylene Fibre for Concrete. Available online: https://master-builders-solutions.com/en-au/products/masterfiber/masterfiber-m-018/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Liao, G.; Wu, R.; He, M.; Huang, X.; Wu, L. The Effect of Steel Fiber Content on the Workability and Mechanical Properties of Slag-Based/Fly Ash-Based UHPC. Buildings 2025, 15, 2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, F.P.; Bosco, E.; Salet, T.A.M. Ductility of 3D printed concrete reinforced with short straight steel fibers. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2018, 14, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, R.D.; Usman, M.; Ali, A.; Majid, U.; Faizan, M.; Malik, U.J. Inclusive characterization of 3D printed concrete (3DPC) in additive manufacturing: A detailed review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 394, 132229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Ji, G.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, G.; Mechtcherine, V.; Pan, J.; Wang, L.; Ding, T.; Duan, Z.; Du, S. Large-scale 3D printing concrete technology: Current status and future opportunities. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 122, 104115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C1437-20; Standard Test Method for Flow of Hydraulic Cement Mortar. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- BS EN 480-2:2006; Admixtures for Concrete, Mortar and Grout—Test Methods—Part 2: Determination of Setting Time. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2006.

- Nematollahi, B.; Vijay, P.; Sanjayan, J.; Nazari, A.; Xia, M.; Nerella, V.N.; Mechtcherine, V. Effect of Polypropylene Fibre Addition on Properties of Geopolymers Made by 3D Printing for Digital Construction. Materials 2018, 11, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliyavaradhan, S.K.; Ambily, P.; Prem, P.R.; Ghodke, S.B. Test methods for 3D printable concrete. Autom. Constr. 2022, 142, 104529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jansen, K.; Zhang, H.; Rodriguez, C.R.; Gan, Y.; Çopuroğlu, O.; Schlangen, E. Effect of printing parameters on interlayer bond strength of 3D printed limestone-calcined clay-based cementitious materials: An experimental and numerical study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 262, 120094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, D.; Tan, M.J.; Qian, S. Investigation of interlayer adhesion of 3D printable cementitious material from the aspect of printing process. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 143, 106386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, B.; Paul, S.C.; Tan, M.J. Anisotropic mechanical performance of 3D printed fiber reinforced sustainable construction material. Mater. Lett. 2017, 209, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunothayan, A.R.; Nematollahi, B.; Ranade, R.; Bong, S.H.; Sanjayan, J.G.; Khayat, K.H. Fiber orientation effects on ultra-high performance concrete formed by 3D printing. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 143, 106384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C109/C109M-23; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Hydraulic Cement Mortars (Using 2-in. or [50 mm] Cube Specimens). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025.

- ASTM C293/C293M-16; Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Concrete (Using Simple Beam with Center-Point Loading). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- Tay, Y.W.D.; Qian, Y.; Tan, M.J. Printability region for 3D concrete printing using slump and slump flow test. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 174, 106968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareei, S.A.; Ameri, F.; Bahrami, N. Microstructure, strength, and durability of eco-friendly concretes containing sugarcane bagasse ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 184, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, H.G.; Mardani, A.; Beytekin, H.E. Effect of Silica Fume Utilization on Structural Build-Up, Mechanical and Dimensional Stability Performance of Fiber-Reinforced 3D Printable Concrete. Polymers 2024, 16, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, J.; Balasubramanian, S.; Si, W.; Khan, M.; McNally, C. Towards Greener 3D Printing: A Performance Evaluation of Silica Fume-Modified Low-Carbon Concrete. Buildings 2025, 15, 3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, N.A.I.A.; Abdullah, S.R.; Ibrahim, M.; Shahidan, S.; Ismail, N. Initial properties of 3D printing concrete using Rice Husk Ash (RHA) as Partial Cement Replacement. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1022, 012055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, K.; Rajagopal, K.; Thangavel, K. Evaluation of bagasse ash as supplementary cementitious material. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2007, 29, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeini, M.A.; Hosseinpoor, M.; Yahia, A. Effectiveness of the rheometric methods to evaluate the build-up of cementitious mortars used for 3D printing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 257, 119551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Zhou, D.; Khayat, K.H.; Feys, D.; Shi, C. On the measurement of evolution of structural build-up of cement paste with time by static yield stress test vs. small amplitude oscillatory shear test. Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 99, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrot, A.; Rangeard, D.; Pierre, A. Structural built-up of cement-based materials used for 3D-printing extrusion techniques. Mater. Struct. 2015, 49, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, N. A thixotropy model for fresh fluid concretes: Theory, validation and applications. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 1797–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrot, A.; Pierre, A.; Vitaloni, S.; Picandet, V. Prediction of lateral form pressure exerted by concrete at low casting rates. Mater. Struct. 2014, 48, 2315–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buswell, R.A.; De Silva, W.R.L.; Jones, S.Z.; Dirrenberger, J. 3D printing using concrete extrusion: A roadmap for research. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 112, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.; Austin, S.A.; Lim, S.; Buswell, R.A.; Gibb, A.G.F.; Thorpe, T. Mix design and fresh properties for high-performance printing concrete. Mater. Struct. 2012, 45, 1221–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.F.W. Cement Chemistry; Hydrated Cement Paste; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, I. The calcium silicate hydrates. Cem. Concr. Res. 2008, 38, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, J.; Odler, I. 5-Hydration, Setting and Hardening of Portland Cement. In Lea’s Chemistry of Cement and Concrete, 5th ed.; PHewlett, C., Liska, M., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 157–250. [Google Scholar]

- Scrivener, K.L.; Juilland, P.; Monteiro, P.J. Advances in understanding hydration of Portland cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 78, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, B.; Unluer, C.; Tan, M.J. Extrusion and rheology characterization of geopolymer nanocomposites used in 3D printing. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 176, 107290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.K.; Monteiro, P.J.M. Concrete: Microstructure, Properties, and Materials, 4th ed.; Mehta, P.K., Monteiro, P.J.M., Eds.; McGraw-Hill’s Access Engineering; McGraw-Hill Professional: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chindaprasirt, P.; Jaturapitakkul, C.; Sinsiri, T. Effect of fly ash fineness on microstructure of blended cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2007, 21, 1534–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, F.L.; Cordeiro, G.C. Partial cement replacement by different sugar cane bagasse ashes: Hydration-related properties, compressive strength and autogenous shrinkage. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 272, 121625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.-C. Effects of sugar cane bagasse ash as a cement replacement on properties of mortars. Sci. Eng. Compos. Mater. 2012, 19, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucen, H.; Long, L.; Shipeng, Z.; Huanghua, Z.; Jianzhuang, X.; Sun, P.C. The synergistic effect of greenhouse gas CO2 and silica fume on the properties of 3D printed mortar. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 271, 111188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, G.; Yang, Y.; Wu, M.; Pang, B. Fresh properties of a novel 3D printing concrete ink. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 174, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeev, P.; Ramesh, A.; Navaratnam, S.; Sanjayan, J. Using Fibre recovered from face mask waste to improve printability in 3D concrete printing. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 139, 105047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tran, P.; Van, V.N.; Gunasekara, C.; Setunge, S. 3D printing of cementitious mortar with milled recycled carbon fibres: Influences of filament offset on mechanical properties. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 142, 105169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Althoey, F.; Alotaibi, B.S.; Gamil, Y.; Iftikhar, B. An overview of recent advancements in fibre-reinforced 3D printing concrete. Front. Mater. 2023, 10, 1289340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, B.; Si, W.; Khan, M.; McNally, C. Recent Advancements in Polypropylene Fibre-Reinforced 3D-Printed Concrete: Insights into Mix Ratios, Testing Procedures, and Material Behaviour. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhu, L.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xi, X. The Influence of Polypropylene Fiber on the Working Performance and Mechanical Anisotropy of 3D Printing Concrete. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2021, 19, 1264–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landa-Ruiz, L.; Landa-Gómez, A.; Mendoza-Rangel, J.M.; Landa-Sánchez, A.; Ariza-Figueroa, H.; Méndez-Ramírez, C.T.; Santiago-Hurtado, G.; Moreno-Landeros, V.M.; Croche, R.; Baltazar-Zamora, M.A. Physical, Mechanical and Durability Properties of Ecofriendly Ternary Concrete Made with Sugar Cane Bagasse Ash and Silica Fume. Crystals 2021, 11, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.A.E.; Shafiq, N.; Nuruddin, M.F.; Memon, F.A. Compressive strength and microstructure of sugar cane bagasse ash concrete. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2014, 7, 2569–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, T.A.; Hussein, A.A.E.; Ahmed, Y.H.; Semmana, O. Strength, durability, and microstructure properties of concrete containing bagasse ash—A review of 15 years of perspectives, progress and future insights. Results Eng. 2024, 21, 101764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunothayan, A.R.; Nematollahi, B.; Khayat, K.H.; Ramesh, A.; Sanjayan, J.G. Rheological characterization of ultra-high performance concrete for 3D printing. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 136, 104854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yang, L.; Zheng, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, P.; Lu, L.; Cheng, X. Rheological behaviors and structure build-up of 3D printed polypropylene and polyvinyl alcohol fiber-reinforced calcium sulphoaluminate cement composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 10, 1402–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfs, R.J.M.; Bos, F.P.; Salet, T.A.M. Hardened properties of 3D printed concrete: The influence of process parameters on interlayer adhesion. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 119, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; She, W.; Yang, L.; Liu, G.; Yang, Y. Rheological and harden properties of the high-thixotropy 3D printing concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 201, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | Descriptions | Products and Manufacturers |

|---|---|---|

| Cement | Type GP Cement | Bastion GPC, Bunnings, Australia |

| SF | Micro Silica Fume | MasterLife SF100, MB Solutions Pty Ltd., Australia |

| FA | Fly Ash (Grade 1) | Millmerran Flyash Pty Ltd., Australia |

| GGBS | Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag | Wagners Cement Pty Ltd., Australia |

| SCBA | Sugarcane Bagasse Ash | Rocky Point Sugar Mill, Woongoolba, QLD, Australia |

| Fine Aggregate | Sand (<1 mm) | EasyMix Infill Sand, River Sands Pty Ltd., Australia |

| Water | Tap water | |

| SP | PCE base Superplasticiser | MasterGlenium SKY 8379, MB Solutions Pty Ltd., Australia |

| VMA | Viscosity Modifying Agent | MasterMatrix 362 (Liquid), MB Solutions Pty Ltd., Australia MasterMatrix 220 (Powder), MB Solutions Pty Ltd., Australia |

| PP Fibre | Polypropylene Microfiber | MasterFiber M018, MB Solutions Pty Ltd., Australia |

| ST Fibre | Steel Microfiber | ConForce CCM 13, Conforce (Australia) Pty Ltd., Australia |

| Parameter | Equipment/Method | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Morphology/ Elemental composition | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)/ Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) | Physical structure and elemental composition of materials were investigated under Phenom XL G2 Desktop Scanning Electron Microscope operated at 5 KV~20 KV accelerating voltage and using Secondary Electron Detector (SED). Samples were coated with 10 nm Gold (Au) using Gatan Model 682 Precision Etching and Coating Systems (PECS) before imaging. |

| Particle size distribution (PSD) | Laser diffraction particle size analyser | Particle size distribution was determined by laser diffraction using Malvern Mastersizer 3000. Materials were dispersed in water by mechanical stirring, and a laser beam was passed through the dispersed sample, where scattered light intensity at various angles was analysed to calculate the particle size distribution based on Mie theory. |

| Crystallinity | X-ray diffraction (XRD) | XRD patterns were acquired using a Bruker D8 Advance powder diffractometer operating in Bragg–Brentano geometry with a cobalt source (35 kV, 40 mA). Patterns were collected for 60 min from 2 to 90°2θ at a step size of 0.015°. Samples were spun during data collection at 15 rpm. Incident optics included 2.5° Soller slits and a variable divergence slit with an illuminated length of 10 mm. |

| Compound analysis | X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy | Oxide compositions were investigated using a Bruker S8 Tiger Series II Wavelength Dispersive X-ray Fluorescence (WD-XRF) Spectrometer. |

| Oxide | Cement | FA | GGBS | SF | SCBA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaO | 61.75 | 3.12 | 41.18 | 0.16 | 3.97 |

| SiO2 | 19.68 | 53.79 | 33.92 | 95.95 | 60.84 |

| Al2O3 | 4.41 | 32.19 | 14.69 | 0.26 | 10.33 |

| Fe2O3 | 3.2 | 2.3 | 0.52 | 0.08 | 5.87 |

| MgO | 3.45 | 1.07 | 5.92 | 0.34 | 1.36 |

| Na2O | 0.08 | 0.34 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 1.22 |

| SO3 | 2.78 | 0.07 | 1.58 | - | 0.12 |

| K2O | 0.45 | 0.67 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 2.2 |

| LOI | 3.14 | 0.49 | 1.09 | 3.84 | 10.55 |

| Crystaline Structure | Cement | FA | GGBS | SF | SCBA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartz | 0.6 | 3.8 | 0.2 | 1.5 | 31.1 |

| Magnetite | 0.5 | 3.7 | |||

| Periclase | 2.7 | ||||

| Calcite | 8.2 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 1.3 | |

| Gypsum | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.4 | ||

| Alite, C3S | 58.8 | 1.0 | |||

| Belite, β-C2S | 6.9 | ||||

| α′-C2S | 3.3 | ||||

| Aluminate, C3A | 2.1 | ||||

| Ferrite, C4AF | 11.0 | ||||

| Plagioclase | 1.2 | 4.9 | |||

| K-Feldspar | 5.8 | ||||

| Mullite (2:1 + 3:2) | 28.7 | ||||

| Amorphous | 0.3 | 64.5 | 96.8 | 97.2 | 52.0 |

| Particle/Spot ID | Particle Morphology | Major Oxides from EDS Elemental Identification |

|---|---|---|

| 1, 4, 8 | Prismatic/Tubular | SiO2, Al2O3 |

| 3 | Spherical | SiO2, Al2O3, CaO, Fe2O3 |

| 2, 5 | Irregular porous | SiO2, Al2O3, CaO, Fe2O3 |

| 6, 7 | Irregular | SiO2, Al2O3 |

| PC | 10BA | 20BA | 25BA | PC-0.1%PP | PC-0.5%ST | 20BA-0.1%PP | 20BA-0.5%ST | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPC | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.60 |

| FA | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| GGBS | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| SF | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| SCBA | - | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.25 | - | - | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| Sand/Binder ratio | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| VMA (L) | 0.57 | 0.57 | 057 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.57 |

| VMA (P) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| SP | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| PP Fibre (% of binders) | 0.10 | - | 0.10 | - | ||||

| Steel Fibre (% of concrete volume) | - | 0.50 | - | 0.50 | ||||

| Water/Binder | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Mix ID | PC | 10BA | 20BA | 25BA | PC-0.1%PP | PC-0.5%ST | 20BA-0.1%PP | 20BA-0.5%ST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mini slump (mm) | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 12 |

| Flow dia. (mm) | 165 | 185 | 190 | 195 | 160 | 160 | 170 | 170 |

| Mix ID | Height (mm) | Spread (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| PC | 45 | 98 |

| 10BA | 42 | 101.25 |

| 20BA | 26 | 131 |

| 25BA | 20 | 141 |

| PC-0.1%PP | 48 | 98 |

| PC-0.5%ST | 46 | 99.5 |

| 20BA-0.1%PP | 31 | 126 |

| 20BA-0.5%ST | 28 | 128.5 |

| Mix ID | PC | 10BA | 20BA | 20BA-0.1%PP | 20BA-0.5%ST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual height (mm) | 202 | 201 | 198 | 200 | 201 |

| Vertical Deformation (mm) | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Mix ID | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Flexural Strength (MPa) | Interlayer Bond Strength (MPa) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mould-Cast (MC) | Printed-X | Printed-Y | Printed-Z | Mould-Cast (MC) | Printed | Printed | |

| PC | 85.08 | 79.20 | 73.45 | 76.83 | 9.97 | 7.84 | 6.35 |

| 10BA | 92.76 | 86.41 | 74.25 | 83.94 | 10.88 | 8.37 | 6.71 |

| 20BA | 74.13 | 71.92 | 62.28 | 70.06 | 9.03 | 6.88 | 6.27 |

| 25BA | 69.24 | 65.75 | 58.18 | 62.45 | 8.10 | 6.54 | 6.40 |

| PC-0.1%PP | 90.40 | 81.05 | 76.46 | 78.19 | 11.91 | 9.59 | 6.11 |

| PC-0.5%ST | 95.08 | 86.65 | 81.34 | 83.51 | 13.72 | 10.17 | 6.23 |

| 20BA-0.1%PP | 78.65 | 74.85 | 63.66 | 72.06 | 10.89 | 8.34 | 6.02 |

| 20BA-0.5%ST | 83.56 | 79.06 | 67.89 | 75.13 | 12.87 | 9.61 | 6.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Talukdar, A.H.M.J.H.; Belek Fialho Teixeira, M.; Fawzia, S.; Zahra, T.; Kangavar, M.E.; Ramli Sulong, N.H. Investigation on the Fresh and Mechanical Properties of Low Carbon 3D Printed Concrete Incorporating Sugarcane Bagasse Ash and Microfibers. Buildings 2026, 16, 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010230

Talukdar AHMJH, Belek Fialho Teixeira M, Fawzia S, Zahra T, Kangavar ME, Ramli Sulong NH. Investigation on the Fresh and Mechanical Properties of Low Carbon 3D Printed Concrete Incorporating Sugarcane Bagasse Ash and Microfibers. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):230. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010230

Chicago/Turabian StyleTalukdar, A. H. M. Javed Hossain, Muge Belek Fialho Teixeira, Sabrina Fawzia, Tatheer Zahra, Mohammad Eyni Kangavar, and Nor Hafizah Ramli Sulong. 2026. "Investigation on the Fresh and Mechanical Properties of Low Carbon 3D Printed Concrete Incorporating Sugarcane Bagasse Ash and Microfibers" Buildings 16, no. 1: 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010230

APA StyleTalukdar, A. H. M. J. H., Belek Fialho Teixeira, M., Fawzia, S., Zahra, T., Kangavar, M. E., & Ramli Sulong, N. H. (2026). Investigation on the Fresh and Mechanical Properties of Low Carbon 3D Printed Concrete Incorporating Sugarcane Bagasse Ash and Microfibers. Buildings, 16(1), 230. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010230