Abstract

The EPBD 2024 recast sets the deadline for new Zero-Emission Building standards for all new publicly owned buildings to 2028 and to 2030 for all new buildings. In the scope of Life Cycle Assessment stages, all steps resulting in major emissions from buildings must be considered and presented. The research evaluates the life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of a single-family house, focusing on diverse construction types and the hourly method of the annual energy calculations for continental and coastal climate areas in Croatia under the upcoming standards. Embodied carbon of diverse construction types was compared mutually, and required steps to meet the operational zero-emission standards were analyzed. Embodied energy of a 137.0 m2 family house built out of reinforced concrete results in up to 67 tons of CO2eq emissions, while wood in cross-laminated timber structures absorbs more carbon than emitted for all other materials and construction processes—23 tons of CO2eq. Regarding operational energy and accompanying emissions, in order to cost-effectively meet future ZEB standards in Croatia and offset the remaining operational emissions, photovoltaic systems of up to 2.5 kWp are required in continental areas and 1.6 kWp in coastal regions.

1. Introduction

The building sector in the European Union (EU) consumes about 40% of total energy and, as such, has become a primary focus on climate policies and major economies, leading to a climate neutral Europe by 2050 [1,2]. The next step to carbon neutrality is zero-emission building (ZEB) standards which will come into force in the EU in 2028 for new buildings in public ownership and in 2030 for all new buildings [3]. Energy sources with low carbon emissions are mandatory for the current nearly zero-energy building (nZEB) standards as well as for the future ZEB standards [4]. In family buildings, such systems are electrically powered air-to-water heat pumps—one of the optimal solutions [5]. In heat pumps, electricity is used for the mechanical work of thermal energy transfer from, or to, the surrounding environment [6]. Heat pumps are used for heating, cooling, and domestic hot water (DHW) preparation.

Energy sources for electricity production include fossil fuels, nuclear energy, and renewable sources, mostly wind, hydro, and solar. Worldwide, the amount of fossil fuels in electricity production is steadily decreasing while being replaced by renewable sources. In Europe, electricity carbon intensity dropped from 641 g/kWh in 1991 to 207 g/kWh in 2023, with a downward trend expected to continue [7,8], whereas, in Croatia, electricity carbon intensity dropped from 302 g/kWh in 2000 to 174 g/kWh in 2024 [9]. Although fossil sources in electricity production are on the decline, they are still used during periods of high demand on the grid or when renewable sources are not available. Peak demands on the grid are still covered by the fossil-based power plants [10].

Current regulations regarding nZEB requirements vary greatly across the EU, from the strictest Danish regulations, which allow for 27 (kWh/(m2 a)) of specific annual primary energy consumption in family houses, to the most lenient Romanian regulations, which allow for 158 (kWh/(m2 a)) [11]. EU-wide, family houses are of very different levels of energy efficiency. Current regulations in Croatia are more demanding than EU benchmarks, with 45 kWh/(m2a) for family houses in the continental parts of Croatia and 35 kWh/(m2 a) for coastal areas [12]. For Croatia, the prescribed consumption of primary energy is among the lowest in the EU, meaning the energy efficiency of family houses is already at high levels.

Challenges in achieving the ZEB standards also lie in the availability of renewable energy, especially in the production of electricity. The EU countries with an unfavorable ratio of fossil fuels in their electricity mix face greater challenges in reducing annual operational energy emissions, such as Poland, with approximately 650 gCO2eq/kWh. In the case of Croatia, hydropotential reduces electricity generation to below 200 gCO2eq/kWh [13].

The potential for on-site electricity production and emission savings is much greater compared with electricity from the grid. Almost 500 gCO2eq/kWh can be saved because fossil fuel power plants are still used for the residual demand of the load, which renewable sources cannot cover [14]. A series of goals are set for future buildings to achieve zero-emission standards. They will require high energy efficiency, use of 100% renewable energy, or production of energy on site. There is a disproportion in specific emissions of the electricity taken from the grid and potential savings in power plants when excess power is sent to the grid.

As stated in the EPBD 2024 recast, embodied carbon will be reported only informatively, while operational carbon will have to be zero (or almost zero) on the annual time frame [3]. If the forthcoming ZEB standards mandate that operational carbon is to be reduced to zero (or almost zero) annually, the only remaining emissions from buildings will be the ones related to embodied energy. Therefore, the main research questions of this study are what the amount of embodied carbon in various construction types is and what required steps are to nullify the operational carbon to meet the ZEB standards in family houses in Croatia.

Zero-emission buildings have existed as a concept for a few decades now, with different approaches in minimizing GHG emissions from buildings. At first, studies of the zero-emission concept concentrated only on the operational emissions, and then later, embodied emissions were also included. ZEB concepts that were able to offset embodied carbon proved to be difficult to achieve [15]. Previous research of specific embodied emissions in masonry construction resulted in 353 kgCO2eq/m2 and in 218 kgCO2eq/m2 in timber frame buildings in Ireland [16]. Different results were obtained in the UK—571 kgCO2eq/m2 in masonry structures and 385 kgCO2eq/m2 in off-site panelized timber frames; whole life carbon for multi-story buildings varied from 119 kgCO2eq/m2 for timber structures to 185 for reinforced structures [17,18]. The greatest emissions were exhibited in the analysis of residential masonry buildings in Hungary—ranging between 475 and 775 kgCO2eq/m2 [19].

Until the EPBD definition, previous ZEB definitions varied in the life cycle stages included in the calculation. The Norwegian net zero-emission building concept is proposed to offset both operational and embodied emissions by renewable energy generated on site. The idea of net zero-emission building is the “pay back” of the embodied energy emissions [20]. Electrical energy production on site is proven to be the key factor to balancing out the annual emissions. Only the buildings with PV production manage to nullify the annual emissions [21]. The possibility of sending any excess power to the grid is essential in the decarbonization process [22]. Research that included PV modeling for a zero-emission neighborhood in Norway resulted in 850 kWp per 10.000 m2 of building floor area to offset both operational and embodied emissions [23]. In similar research, a 2449 m2 institute building in South Korea required 116 kWp of installed PV power, and 362 m2 of PV panels were required for a 2405 m2 office building in Italy [24,25].

2. Methodology

In the scope of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) stages, all major steps resulting in major GHG emissions from a building are included in the calculation. The study evaluates the life cycle greenhouse gas emissions for two representative single-family houses—one located in a continental area and the other in a coastal area of Croatia—aiming to capture the impacts of the Product and Construction stage along with the Use stage n alignment with current European regulatory requirements (Table 1).

Table 1.

Life Cycle Assessment stages included in the analysis (data adapted from EN 15978/CEN TC 350 [13]).

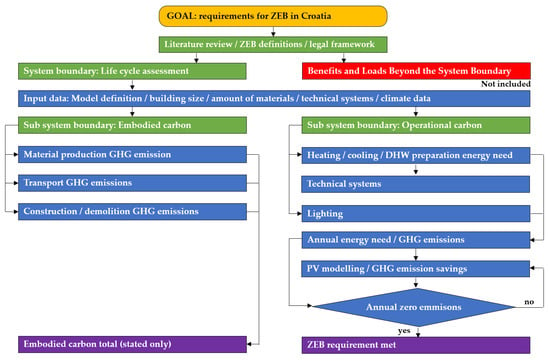

The methodology includes the assessment of embodied and operational carbon, as shown in Figure 1. Different load-bearing structural solutions are analyzed to evaluate their influence on embodied emissions. Operational energy performance is calculated using an hourly time step and real electricity mix data, while photovoltaic production on site is considered to evaluate the building’s potential to achieve zero-emission performance. Calculation of embodied carbon is performed in Microsoft Office Excel (Version 2302). The code for calculation of operational energy is written in Visual Basic, Visual Studio (Version 17.13.5) programming language according to V. Soldo et al. [26].

Figure 1.

Determination of embodied and operational carbon.

2.1. Embodied Carbon

Embodied energy analysis was performed on a model of a 137.0 m2 net area (182.4 m2 gross area) single-family house, shown in Figure 2. Four major components of embodied energy were calculated in this analysis: built-in materials, refurbishment/renovation, material transport, and construction/deconstruction.

Figure 2.

Case study: single-family house.

Embodied carbon is calculated according to following Equations (1)–(4).

where E (kgCO2eq) is the total GHG emissions, n (-) is the number of materials, m (kg) is the mass of the materials, and ematerial (kgCO2eq/kg) is the specific material production CO2eq emission. The same equation is used for the production emissions of built-in and reconstruction materials.

where d (km) is the material transport distance and etransport (gCO2eq/(t km)) is the specific road transport emission of 57 gCO2eq/(t km). Distance includes both the delivery and the disposal distance of materials.

where e(de)construction (kgCO2eq/ton) is the specific construction and demolition emission.

Total embodied carbon is the sum of all the material production emissions, transport emissions, and construction and demolition emissions.

2.1.1. Built-In Materials (Stages A1, A2, A3)

Since embodied carbon primarily depends on the building material, six different types of load-bearing structures were evaluated: reinforced concrete, hollow clay block, porous clay block, aerated concrete block, wood-based sandwich panels, and cross-laminated timber. In the coastal areas of Croatia, masonry and reinforced concrete dominate because of traditional massive construction practices using stone due to availability of this material and its high thermal mass, which provided protection from the Mediterranean climate (high temperatures in summer and strong cold winds during winter). Massive materials also offered resistance to moisture and salt exposure, while timber was scarce and therefore used only when necessary. In contrast, inland regions have extensive forest resources, making timber locally available. From a traditional perspective, in rural regions wooden houses were also easier to heat up during winter, contributing to the widespread use of lightweight timber construction in traditional continental architecture, while masonry was more common for residences, high-rises, and public buildings. Nowadays, all types of construction equally coexist in continental Croatia. Consequently, all six types of construction are analyzed for continental areas, while only reinforced concrete and masonry structures are analyzed for coastal areas. Thermal properties of the envelope are designed according to the regulations for the continental and coastal parts of Croatia. The main difference is in the thickness of thermal insulation in the envelope or, in the case of porous clay block and aerated concrete, the thickness of the bearing wall. The number of other types of materials used in construction is the same for both houses in continental and coastal areas. Specific GHG emissions for material production are obtained from the Baubook Eco2Soft database, compliant with the environmental product declaration (EPD) standard EN 15804 (includes stages A1, A2, and A3) [27,28].

Timber constructions store carbon during a building’s lifetime (50–100 years). Reuse of timber in various elements can prolong carbon storage for additional decades in forms of wood-based panels or construction materials again [29]. Despite the proven benefits, timber reuse and recycling are currently not used widely due to low demand for used timber, lack of standards, and material damaged in deconstruction [30]. However, timber reuse is expected to increase in the following decades. The time frame observed in this analysis is 50 years, at which point, carbon should still be stored in the construction, as timber end-of-life emissions occur much later than the end of a building’s life. Benefits and loads beyond the system boundary for construction materials are not accounted for.

2.1.2. Refurbishment/Renovation (Stages B4, B5)

The usual expected lifetime of a building is 50 years. Some of the building materials and elements are not that durable and must be replaced once or twice during the building’s life cycle. Reconstruction during the usage phase of the building results in CO2 emissions due to material production, the same as during the building phase. GHG emissions from the materials used in phases B4 and B5 also include stages A1, A2, and A3.

2.1.3. Material Transport (Stages A4, C2)

The total weight of materials used in building depends on the type of load-bearing construction. Materials of the greatest weight are used in reinforced concrete buildings, and materials of the least weight are used in light-frame or sandwich panels. Transport-related embodied carbon emissions include four stages of transport: bringing materials to the site for initial construction and later for reconstruction, transporting waste materials to the disposal site or recycling plant at the reconstruction phase, and at the end-of-life phase. Transport-related emissions depend on the type of transport, cargo weight, and distance. Use of locally produced materials is encouraged to reduce the distance of transport. Local transport distance can be considered within the same country or region, up to 300 km [27,31], or 100 km for delivery and 50–100 km for waste recycling or disposal [32]. In this case, transport distances were determined for all used materials and products for two reference cities—from the production site to the construction site in Zagreb and Split. Transport emissions vary by type of transport, with the greatest emissions per ton-km for road transport and the least for maritime transport. Local transport up to 100 km is done by trucks, and there is a difference in emissions for urban and long-haul transport. In urban traffic, emissions reach up to 307 gCO2eq/(t km) due to numerous stops at traffic lights and changes in speed, whereas long-haul transport is much more efficient, with approximately 57 gCO2eq/(t km) [33]. Material transport used in the building phase, reconstruction phase, and deconstruction phases are all accounted for in the transport emissions.

2.1.4. Construction/Deconstruction (Stages A5, C1)

Calculation of emissions related to construction and deconstruction is determined according to fuel and electricity use for machinery, direct process emissions, which include dust or Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC), and other considerations like time of the year, material recycling, etc. If detailed data are not available, estimates according to material amount and type are available—according to building floor area or according to the total mass of the material can be used. Construction-related emissions depend on the material being used for building; for concrete, it is approximately 9 kgCO2eq/m3 [34], which results in approximately 4.5 kgCO2eq per ton. For the deconstruction of concrete structures, estimates per gross floor area vary from 6.19 kgCO2eq/m2 to 17.7 kgCO2eq/m2 [35,36]. According to the mass of the materials in the deconstruction, the estimated range is between 4 and 10 kgCO2eq per ton [37]. In this analysis, an estimate according to the total mass of the materials was performed. A quantity of 5 kgCO2eq/ton was used for the calculation of construction and was the same for deconstruction emissions for all types of load-bearing construction. Emissions for construction and deconstruction are proportional to the weight of the built-in and reconstructed materials and vary greatly depending on the material of the construction.

2.2. Operational Carbon (Stage B6)

The goal of this work is to determine CO2 emissions from electricity use in domestic households in continental and coastal areas of Croatia, as well as the needed energy production on site to achieve the zero-emission standards. Energy consumption in buildings varies throughout the day, just like photovoltaic electricity production. Also, electricity obtained from the grid is produced differently depending on the time of day. Therefore, a one-hour time step method was chosen for the calculation of energy consumption and energy production. Five primary aspects of operational energy were quantified: annual energy need, delivered energy, electricity mix, electricity production on site, and lighting.

2.2.1. Annual Energy Need

Analysis of operational carbon includes emissions from heating, domestic hot water (DHW) preparation, cooling, and lighting. Annual energy consumption for heating QH,nd (kWh/a) and cooling QC,nd (kWh/a) depend on the geometric and physical properties of the building (and ventilation system if applied, which is not the case in this research). The composition of the envelope determines the physical characteristics, which means that different types of load-bearing construction will result in different U (W/(m2 K)) values of the envelope. Table 2 shows the physical characteristics and thickness of thermal insulation in the envelope for all analyzed cases. Annual energy need is calculated according to V. Soldo et al. [26], the hourly method using meteorological information for 8760 h in the year. One-hour time step meteorological data are available for Zagreb, which is a reference location for the continental climate area, and for Split, as a reference location for the coastal climate.

Table 2.

Physical properties of the envelope, depending on the load-bearing construction, for the continental/coastal climate for the analyzed cases.

2.2.2. Delivered Energy

The amount of energy delivered to DHW preparation and the heating and cooling systems depends on both the annual energy need and the type of system. The current obligatory energy standard in the EU is the nearly zero-energy building (nZEB), which is a standard commonly achieved by optimal envelope insulation and the use of renewable energy sources, such as environmental heat used by heat pumps, biomass boilers, solar energy, etc. In this case, for both continental and coastal climates, an electrically powered air-to-water heat pump is used for heating, DHW preparation, and cooling, while energy production on site is achieved by photovoltaic panels. The time step used in the calculation of delivered energy is one hour according to EN 15316-4-2:2017 for heating and DHW preparation, CEN/TR 16798-14:2017 for cooling, and EN 15316-4-3:2017 for photovoltaic electricity production [38,39,40]. Table 3 shows properties of the heat pump required for the calculation of delivered energy and properties of photovoltaic panels required for the calculation of electricity production on site.

Table 3.

Characteristics of technical systems for houses in the continental/coastal area.

2.2.3. Electricity Mix

Energy sources for electricity production in the EU include fossil fuels, nuclear, and renewables (wind, solar, and hydro). Direct emissions in electricity production from nuclear and renewable sources are almost non-existent, while fossil sources result in up to 1.000 gCO2eq/kWh.

The electricity mix varies throughout the day because it depends on the energy demand and available energy sources. Low energy demand can mostly be covered by renewables and nuclear power, but when demand peaks, compensation from fossil fuel power plants is required. Figure 3 shows average electricity production intensity in gCO2eq/kWh by the hour in the day in Croatia for the year 2024, January 2024, June 2024, and 5 May 2024 (the day with the greatest variations in electricity production emissions).

Figure 3.

CO2 emissions by the hour for electricity production in Croatia in 2024.

Hourly information about real-time carbon intensity in electricity production for the year 2024 in Croatia is obtained from the Electricity Maps platform, which uses various sources. The source for the data used in this research is the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity (ENTSO-E), which is an association of 39 transmission system operators (TSOs) from 35 European countries [42].

2.2.4. Electricity Production on Site

According to the EPBD 2024 recast, ZEBs will have to meet the standards of zero greenhouse gas emissions on site for building use, meaning only renewable sources of heating and cooling energy will be allowed. Regarding electricity, total annual primary energy use must originate from renewable sources, which can be ensured by purchasing renewable electricity from the grid or connecting to renewable energy communities. Production of electricity on site is recommended for use on site and for export to the grid, which increases available renewable supply and reduces CO2 emissions.

In the ZEB variants in this research, PV panels are planned on site to determine the required amount of electricity produced and delivered to the grid to nullify the emissions from fossil fuel power plants annually. The model is designed to show how electricity from solar power plants is used in buildings if electricity is produced and how excess electricity is delivered to the grid when production surpasses the consumption. When demand for the building is greater than the production, residual demand is covered from the grid. Figure 4 shows the hourly distribution of electricity consumption and production for a day when excess energy is sent to the grid.

Figure 4.

Hourly building energy consumption and photovoltaic production for a continental climate, 11 June.

The CO2 emissions from energy use for the cases, as shown in Figure 4, vary greatly. When power is used from the grid, greenhouse gas is emitted at the point of generation proportional to the current electricity mix. In Croatia, in 2024, average electricity generation was 194 gCO2eq/kWh, while emissions varied from 48 gCO2eq/kWh to 433 gCO2eq/kWh depending on the grid load and availability of renewable sources. When energy production on the site is sufficient, there is no requirement for electricity use from the grid. That means each kWh used from a PV power plant results in no greenhouse gas emissions. In cases where excess electricity is sent to the grid, the potential for savings in CO2 emissions is much greater.

The electricity mix for the EU in 2024 consisted of 48% renewables, 25% nuclear, 24% fossil fuels, and 3% other sources (oil, geothermal) [43]. Renewables and nuclear sources result in almost no emissions, while coal plants can emit more than 1.000 gCO2eq per kWh, and highly efficient natural gas combined-cycle plants about 400 gCO2eq per kWh [44]. In electricity production, energy sources are used in a certain order. Renewables produce electricity at low or no cost, so they are always used first. Nuclear power plants run at low fuel cost, but due to the design of the reactors, they are unable to increase or decrease output quickly. Fossil power plants have a higher fuel cost, and they are used lastly to cover residual or peak demand. When electricity is sent to the grid from on-site PV production plants, the amount of electricity from renewable sources in the grid increases and the residual demand covered by fossil sources decreases. That means that every kWh of electricity sent to the grid will save the same amount of kWh of electricity from the fossil fuel power plants. According to the ENTSO-E hourly statistic for electricity carbon intensity in Croatia, in 2024, the average ratio of renewable electricity was 59%, with a 22% minimum and an 87% maximum, meaning that, at all times, fossil-based electricity was used from the grid in various amounts [44]. For Croatia, in 2024, only 3% of electricity was obtained from coal and 12% from gas combined-cycle plants with the carbon intensity of 530 gCO2eq per kWh; the rest of the fossil emissions originated from imported electricity [42]. Considering that approximately 10% of typical electrical losses occur from PV modules to the appliances or the grid [45], 1 kWh of electricity produced and sent to the grid would increase the amount of available green electricity by 0.9 kWh and save 480 gCO2eq emissions if the gas combined-cycle plant is displaced.

2.2.5. Lighting

In residential buildings, lighting represents up to 10% of total energy consumption [46]. Such an amount is low compared with heating and cooling but cannot be ignored in greenhouse gas emissions analysis. Electricity consumption for lighting in Croatia is estimated to be 304 kWh/a for a household [47]. Since the time step for the analysis is one hour, it is important to consider when energy consumption and production occur during the day. For the analysis, it was estimated that lighting is used in the period between 7 a.m. and 11 p.m. and that lighting is used inversely proportional to solar irradiance—when solar irradiation in the exterior drops below 50 W/m2 on a horizontal surface.

3. Results

3.1. Embodied Carbon

Embodied carbon emissions include the GHG emissions of built-in materials or materials used in reconstruction, transport-related emissions, and deconstruction at the end-of-life phase. Table 4 and Table 5 show the mass of materials used in various types of construction in the construction and reconstruction phase for continental and coastal models. Construction- and reconstruction-related emissions are calculated from the bill of materials, as shown in Table 6 and Table 7.

Table 4.

Mass of built-in and reconstruction materials (kg) in a continental single-family house.

Table 5.

Mass of built-in and reconstruction materials (kg) in a coastal area single-family house.

Table 6.

Embodied carbon (kgCO2eq) in a continental single-family house.

Table 7.

Embodied carbon (kgCO2eq) in a coastal area single-family house.

3.2. Operational Carbon

The annual energy needs of the building for heating, DHW preparation, cooling, and lighting is shown in Table 8 for the continental climate zone. Because of highly efficient heat pumps, the energy delivered to the technical systems is several times smaller than the need. Energy consumption, in combination with energy production, is shown in the second part of the table.

Table 8.

Annual energy and GHG emissions balance for a continental single-family house.

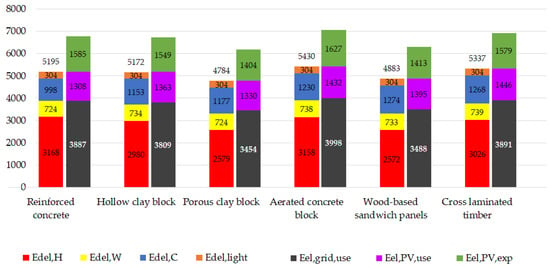

Figure 5 shows annual electricity consumption and production (kWh/a) for the continental family houses, and Figure 6, shows comparison of embodied and operational life cycle GHG emissions (kgCO2eq).

Figure 5.

Annual electricity consumption/production (kWh/a) for a continental single-family house.

Figure 6.

Comparison of lifetime embodied and operational life cycle GHG emissions (kgCO2eq) for a continental single-family house.

The annual energy need is shown in Table 9 for the coastal climate zone. Figure 7 shows annual electricity consumption and production (kWh/a) for the continental family houses, while Figure 8 shows comparison of embodied and operational life cycle GHG emissions (kg CO2eq).

Table 9.

Annual energy and GHG emissions balance for a coastal area single-family house.

Figure 7.

Annual electricity consumption/production (kWh/a) for a coastal area single-family house.

Figure 8.

Comparison of lifetime embodied and operational life cycle GHG emissions (kgCO2eq) for a coastal area single-family house.

4. Discussion

4.1. Embodied Carbon

GHG emissions from material production represent the greatest share of embodied carbon. Table 8 shows the four main components of embodied energy emissions: built-in materials, refurbishment, transport, and construction/deconstruction activities.

It can be observed that built-in materials make up most of the total embodied emissions. The mass of the built-in materials can be seen in Table 4. Due to their notable contribution to the total material mass, load-bearing structures have a major influence on embodied emissions. Reinforced concrete structures are responsible for the greatest specific emissions of 484–489 kgCO2eq/m2 for houses both in continental and coastal areas of Croatia, primarily due to cement production emissions. Masonry houses follow with similar results, which are approximately 307–309 kgCO2eq/m2 for hollow clay blocks, 313–322 kgCO2eq/m2 for porous clay blocks, and 259–266 kgCO2eq/m2 for aerated concrete blocks. The lowest share of embodied carbon is in the massive timber walls and slabs, which have large amount of timber beams and OSB boards; wood-based sandwich panels account for only 53 kgCO2eq/m2, while cross-laminated timber (CLT) results in 170 kgCO2eq/m2 absorbed due to carbon sequestration in biomass. The results considering concrete and masonry constructions are in line with previous research [16,17,18], while timber constructions show much lesser values compared with others [16]. Such a difference is due to the assumption that at the building’s end-of-life phase, timber will not be burned or landfilled but reused and recycled. That way, carbon will be stored for another 30–50 years. Table 6 shows material production-related GHG emissions. Figure 6 and Figure 8 confirm that built-in carbon represents the dominant share of embodied emissions across all types of construction, while other stages of embodied emissions, including construction-related emissions, retrofit, transportation, and end-of-life phases, contribute in a comparatively minor way.

4.2. Operational Carbon

As noted in the introduction, Croatian nZEB requirements are among the strictest in the EU. Annual delivered energy and electricity production requirements, as shown in Table 9, confirm that delivered electricity consumption results in comparatively low greenhouse gas impacts. Due to the efficient building envelope and highly efficient heat pumps, the delivered energy for heating, cooling, and DHW is considerably lower than the building’s energy demand. For continental cases, annual specific heating energy consumption ranges from 54 to 61 kWh/(m2 a), and for coastal cases, 23 to 30 kWh/(m2 a), depending on the type of construction. Such consumption for heating is optimal and represents energy performance class B–C for continental cases and classes A–B for coastal cases. Despite Croatia’s relatively low grid carbon intensity (<200 gCO2eq/kWh), electricity consumption still contributes to operational emissions. Therefore, photovoltaic systems are introduced to offset emissions by reducing electricity drawn from fossil-based generation. The findings confirm that photovoltaic production is shown to provide disproportionate emission savings. Approximately 56% of the total energy needs of the building must be produced by a photovoltaic (PV) power plant on site to nullify the operational emissions in continental regions of Croatia and approximately 64% in coastal areas. To reach the zero-emission status for a 137.0 m2 family house, the required PV installed power is, on average, 2.5 kWp for continental family houses with a PV yield of 1.176 kWh/kWp. In coastal areas, the average PV installed power is 1.6 kWp with a PV yield of 1.364 kWh/kWp. Compared with previous research, a smaller PV power plant can suffice due to lower electricity carbon intensity in Croatia than in analyzed countries (Korea and Italy) as well as different building use [24,25]. The PV power plant modeled for the case in Norway is relatively larger because it must also offset embodied carbon emissions [23].

5. Conclusions

This research demonstrates that both embodied and operational carbon must be addressed when designing new zero-emission homes. Built-in materials—particularly the structural systems—have the highest share of embodied emissions, with reinforced concrete showing the worst performance on account of intense emissions in cement production. On the contrary, cross-laminated timber constructions are the most environmentally friendly in terms of GHG emissions. Wooden elements have a negative emission because more CO2 is absorbed in the structure of the wood than is released for its production (stages A1, A2, and A3). For a massive cross-laminated timber structure, the amount of absorbed carbon is three times greater than the emissions for all other built-in materials.

The high energy efficiency of new buildings, low carbon intensity of electricity, and the use of fossil fuel power plants in electricity production create favorable conditions for the ZEB standards in Croatia. Operational emissions in Croatia are already comparatively low due to the favorable electricity mix and high energy efficiency standards for new buildings. In the ZEB model proposed in this paper, the results confirm that electricity production planned on site for use in the building is sufficient to offset residual emissions and enable annual zero-emission operation in both continental and coastal climates, showing the optimal level of energy efficiency of the analyzed family houses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.V. and M.B.; methodology, M.B.; software, M.B.; validation, Z.V. and M.N.M.; formal analysis, M.B. and M.N.M.; investigation, M.B. and M.N.M.; resources, Z.V.; data curation, M.N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.V., M.B., and M.N.M.; writing—review and editing, M.N.M.; visualization, M.N.M.; supervision, Z.V.; project administration, Z.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EPS | Expanded polystyrene (thermal insulation) |

| MW | Mineral wool (thermal insulation) |

| XPS | Extruded polystyrene (insulation) |

| nZEB | Nearly zero-energy building |

| ZEB | Zero-emission building |

| APV,ef (m2) | Effective photovoltaic module area |

| Edel,C (kWh/a) | Delivered energy for space cooling |

| Edel,H (kWh/a) | Delivered energy for space heating |

| Edel,light (kWh/a) | Delivered energy for lighting |

| Edel,total (kWh/a) | Total delivered energy |

| Edel,W (kWh/a) | Delivered energy for domestic hot water |

| Eel,grid use (kWh/a) | Electricity imported from the grid |

| Eel,PV (kWh/a) | Electricity generated by PV system |

| Eel,PV,exp (kWh/a) | PV electricity exported to grid |

| Eel,PV,used (kWh/a) | On-site used PV electricity |

| PPV (kWp) | PV installed power |

| GHG emissions (kgCO2eq/a) | Operational greenhouse gas emissions |

| PV GHG savings (kgCO2eq/a) | Avoided GHG from PV replacing grid electricity |

| Q″C,nd (kWh/(m2·a)) | Net specific space cooling demand (per floor area) |

| Q″H,nd (kWh/(m2·a)) | Net specific space heating demand (per floor area) |

| QC,nd (kWh/a) | Net space cooling demand |

| QH,nd (kWh/a) | Net space heating demand |

| QW,nd (kWh/a) | Net domestic hot water demand |

References

- Maduta, C.; D’Agostino, D.; Tsemekidi-Tzeiranaki, S.; Castellazzi, L. From Nearly Zero-Energy Buildings (NZEBs) to Zero-Emission Buildings (ZEBs): Current status and future perspectives. Energy Build. 2025, 328, 115133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi, M.; Rasheed, E.; Le, A. Systematic Review on the Barriers and Challenges of Organisations in Delivering New Net Zero Emissions Buildings. Buildings 2024, 14, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive (EU) 2024/1275 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 April 2024. 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/1275/oj/eng (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Myint, N.N.; Shafique, M.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, Z. Net zero carbon buildings: A review on recent advances, knowledge gaps and research directions. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajacs, A.; Lebedeva, K.; Bogdanovičs, R. Evaluation of Heat Pump Operation in a Single-Family House. Latv. J. Phys. Tech. Sci. 2023, 60, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjerkeń, H.; Zavrl, M.Ń.; Stegnar, G. Heat Pumps and Cost Optimal Building Performance. Eur. Sci. J. 2014, 10, 330–339. [Google Scholar]

- Scarlat, N.; Prussi, M.; Padella, M. Quantification of the carbon intensity of electricity produced and used in Europe. Appl. Energy 2022, 305, 117901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Information and Observation Network (Eionet). Greenhouse Gas Emission Intensity of Electricity Generation in Europe, EEA Web Team. 2021. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/ims/greenhouse-gas-emission-intensity-of-1 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Carbon Intensity of Electricity Generation. 2025. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/carbon-intensity-electricity?time=2023..latest&mapSelect=~HRV (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Ziegler, M.S.; Mueller, J.M.; Pereira, G.D.; Song, J.; Ferrara, M.; Chiang, Y.M.; Trancik, J.E. Storage Requirements and Costs of Shaping Renewable Energy Toward Grid Decarbonization. Joule 2019, 3, 2134–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BPIE. Policy Briefing Nearly Zero: A Review of Eu Member State Implementation of New Buıld Requırements; BPIE: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tehnički Propis o Racionalnoj Uporabi Energije i Toplinskoj Zaštiti u Zgradama (NN 102/2020) Technical Regulation on the Rational Utilization of Energy and Thermal Insulation of Buildings (Official Gazette 102/2020). 2020. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2020_09_102_1922.html (accessed on 22 September 2025). (In Croatian).

- Nowtricity. Real Time Electricity Production Emissions by Country, 2025. Available online: https://www.nowtricity.com/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Brizmohun, R.; Ramjeawon, T.; Azapagic, A. Life cycle assessment of electricity generation in Mauritius. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, I. Towards Zero Energy and Zero Emission Buildings—Definitions, Concepts, and Strategies. Curr. Sustain. Energy Rep. 2017, 4, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.; McAulliffe, B. Study of the Embodied Carbon in Traditional Masonry Construction vs. Timber Frame Construction in Housing; Jeremy Walsh Project Management: Tralee, Ireland, 2020; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Monahan, J.; Powell, J.C. An embodied carbon and energy analysis of modern methods of construction in housing: A case study using a lifecycle assessment framework. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.; D’Amico, B.; Pomponi, F. Whole-life embodied carbon in multistory buildings: Steel, concrete and timber structures. J. Ind. Ecol. 2021, 25, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalay, Z. A parametric approach for developing embodied environmental benchmark values for buildings. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2024, 29, 1563–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, C.; Georges, L.; Kristjansdottir, T.; Wiberg, A.H.; Hestnes, A.G. A Comparative Study of Different PV Installations for a Norwegian NZEB Concept. In Proceedings of the EuroSun 2014, Aix-les-Bains, France, 16–19 September 2014; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristjansdottir, T.F.; Heeren, N.; Andresen, I.; Brattebø, H. Comparative emission analysis of low-energy and zero-emission buildings. Build. Res. Inf. 2018, 46, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduta, C.; Melica, G.; D’Agostino, D.; Bertoldi, P. Towards a decarbonised building stock by 2050: The meaning and the role of zero emission buildings (ZEBs) in Europe. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2022, 44, 101009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinel, D.; Korpås, M.; Lindberg, K.B. Cost Optimal Design of Zero Emission Neighborhoods’ (ZENs) Energy System: Model Presentation and Case Study on Evenstad; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.J.; Joo, H.J.; Park, J.W.; Kim, S.K.; Lee, J.B. Power generation performance of building-integrated photovoltaic systems in a zero energy building. Energies 2019, 12, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannino, R.; Ronchetti, L.; Di Turi, S. Pathway to Zero-Emission Buildings: Energy and Economic Comparison of Different Demand Coverage by RES for a New Office Building. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldo, V.; Noval, S.; Horvat, I. Algoritam za Proračun Potrebne Energije za Grijanje i Hlađenje Prostora Zgrade Prema HRN EN ISO 13790 [Algorithm for Calculating the Energy Needs for Space Heating and Cooling of a Building According to HRN EN ISO 13790]. Zagreb, 2017. Available online: https://mpgi.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/dokumenti/EnergetskaUcinkovitost/meteoroloski_podaci/Algoritam_HRN_EN_13790_2017.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- EN 15804:2012+A2:2019/AC:2021; Sustainability of Construction Works—Environmental Product Declarations—Core Rules for the Product Category of Construction Products. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- baubook GmbH Baubook Eco2soft. Eco2Soft—Ökobilanz für Gebäude, (n.d.). Available online: https://www.baubook.at/eco2soft/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Pronk, A.; Brancart, S.; Sanders, F. Reusing Timber Formwork in Building Construction: Testing, Redesign, and Socio-Economic Reflection. Urban Plan. 2022, 7, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristescu, C.; Honfi, D.; Sandberg, K.; Sandin, Y.; Shotton, E.; Walsh, S.J.; Cramer, M.; Ridley-Ellis, D.; De Arana-fernández, M.; Llana, D.F.; et al. Design for Deconstruction and Reuse of Timber Structures—State of the Art Review; RISE Research Institutes of Sweden: Göteborg, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 15978:2011; Sustainability of Construction Works—Assessment of Environmental Performance of Buildings—Calculation Method. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- Gervasio, H.; Dimova, S. Model for Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Buildings; EUR 29123 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018; ISBN 978-92-79-79973-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragon, P.; Rodríguez, F. CO2 Emissions from Trucks in the EU: An Analysis of the Heavy-Duty CO2 Standards Baseline Data. 2021. Available online: https://theicct.org/publication/co2-emissions-from-trucks-in-the-eu-an-analysis-of-the-heavy-duty-co2-standards-baseline-data/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Chen, S.; Teng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Leung, C.K.Y.; Pan, W. Reducing embodied carbon in concrete materials: A state-of-the-art review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 188, 106653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backes, J.G.; Traverso, M.; Horvath, A. Environmental assessment of a disruptive innovation: Comparative cradle-to-gate life cycle assessments of carbon-reinforced concrete building component. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2023, 28, 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigert, M.; Melnyk, O.; Winkler, L.; Raab, J. Carbon Emissions of Construction Processes on Urban Construction Sites. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizirici, B.; Fseha, Y.; Cho, C.S.; Yildiz, I.; Byon, Y.J. A review of carbon footprint reduction in construction industry, from design to operation. Materials 2021, 14, 6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EN 15316-4-2:2017/AC:2017; Energy Performance of Buildings—Method for Calculation of System Energy Requirements and System Efficiencies—Part 4-2: Space Heating Generation Systems, Heat Pump Systems, Module M3-8-2, M8-8-2, (n.d.). European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- EN 15316-4-3:2017; Energy Performance of Buildings—Method for Calculation of System Energy Requirements and system Efficiencies—Part 4-3: Heat Generation Systems, Thermal Solar and Photovoltaic Systems, Module M3-8-3, M8-8-3, M11-8-3. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- CEN/TR 16798-14:2017; Energy Performance of Buildings—Ventilation for Buildings—Part 14: Interpretation of the Requirements in EN 16798-13—Calculation of Cooling Systems (Module M4-8)—Generation. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- Lončar, D.; Dović, D.; Horvat, I. Algoritam za Određivanje Energijskih Zahtjeva i Učinkovitosti Termo Tehničkih Sustava u Zgradama—Sustavi Kogeneracije, Sustavi Daljinskog Grijanja, Fotonaponski Sustavi [Algorithm for Determining Energy Requirements and Efficiency of Thermotechnical Systems in Buildings—Cogeneration Systems, District Heating Systems, Photovoltaic Systems]. Zagreb, 2017. Available online: https://mpgi.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/dokumenti/EnergetskaUcinkovitost/Propisi/2017/Algoritam-SustaviGrijanjaProstora.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025). (In Croatian)

- Electricity Maps, Carbon Intensity Data (Version 27 January 2025). 2025. Available online: https://www.electricitymaps.com (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- European Commission. Electrification, 2025. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/eus-energy-system/electrification_en (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- ENTSO-E. Power Statistics. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.entsoe.eu/data/power-stats/ (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Bruno, J.C.; Pulido, T. Review and Analysis of Energy Losses and Inverter Sizing in Photovoltaic Plants, 2024. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5001650 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- DNV KEMA Energy and Sustainability; Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Residential Lighting End-Use Consumption Study: Estimation Framework and Initial Estimates; Pacific Northwest National Lab. (PNNL): Richland, WA, USA, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Ministarstvo Gospodarstva i Održivog Razvoja/Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development. Pravilnik o Sustavu za Praćenje, Mejrenje i Verifikaciju Ušteda Energije (NN 98/21) Ordinance on the System for Monitoring, Measuring and Verification of Energy Savings (Official Gazzete 98/21). 2021. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2021_09_98_1772.html (accessed on 25 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.