Flexural Performance of Geopolymer-Reinforced Concrete Beams Under Monotonic and Cyclic Loading: Experimental Investigation

Abstract

1. Introduction

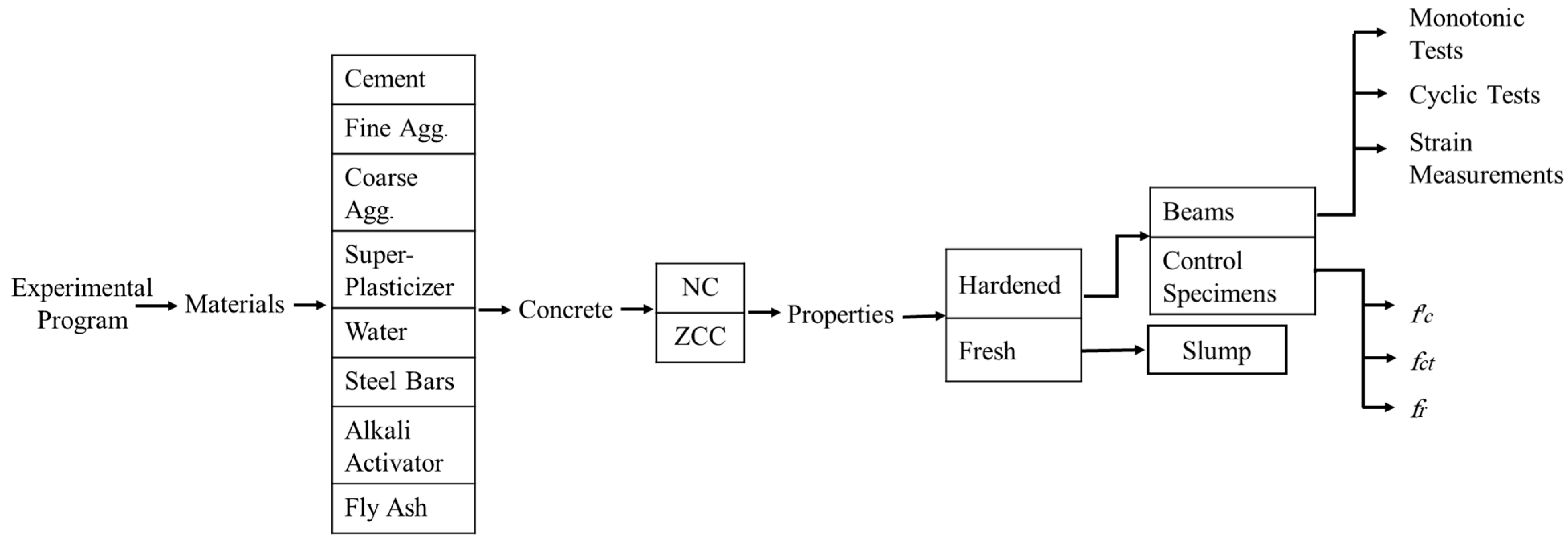

2. Experimental Program

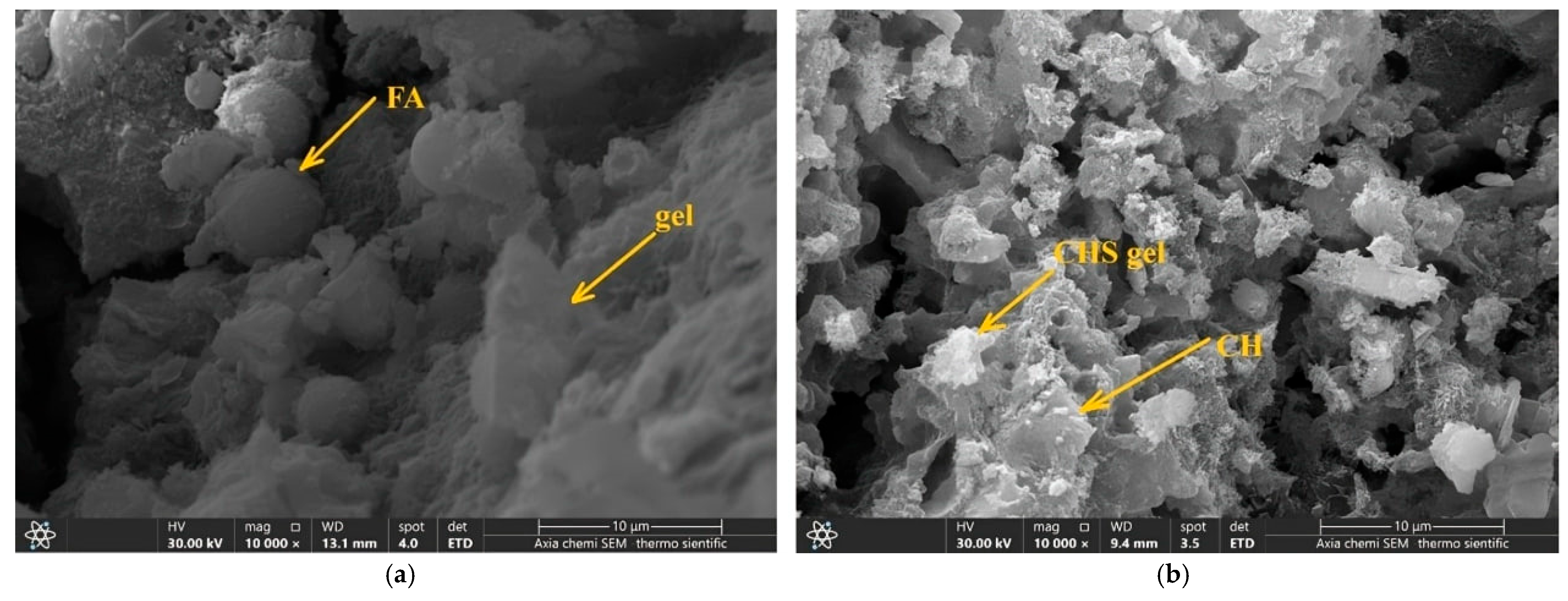

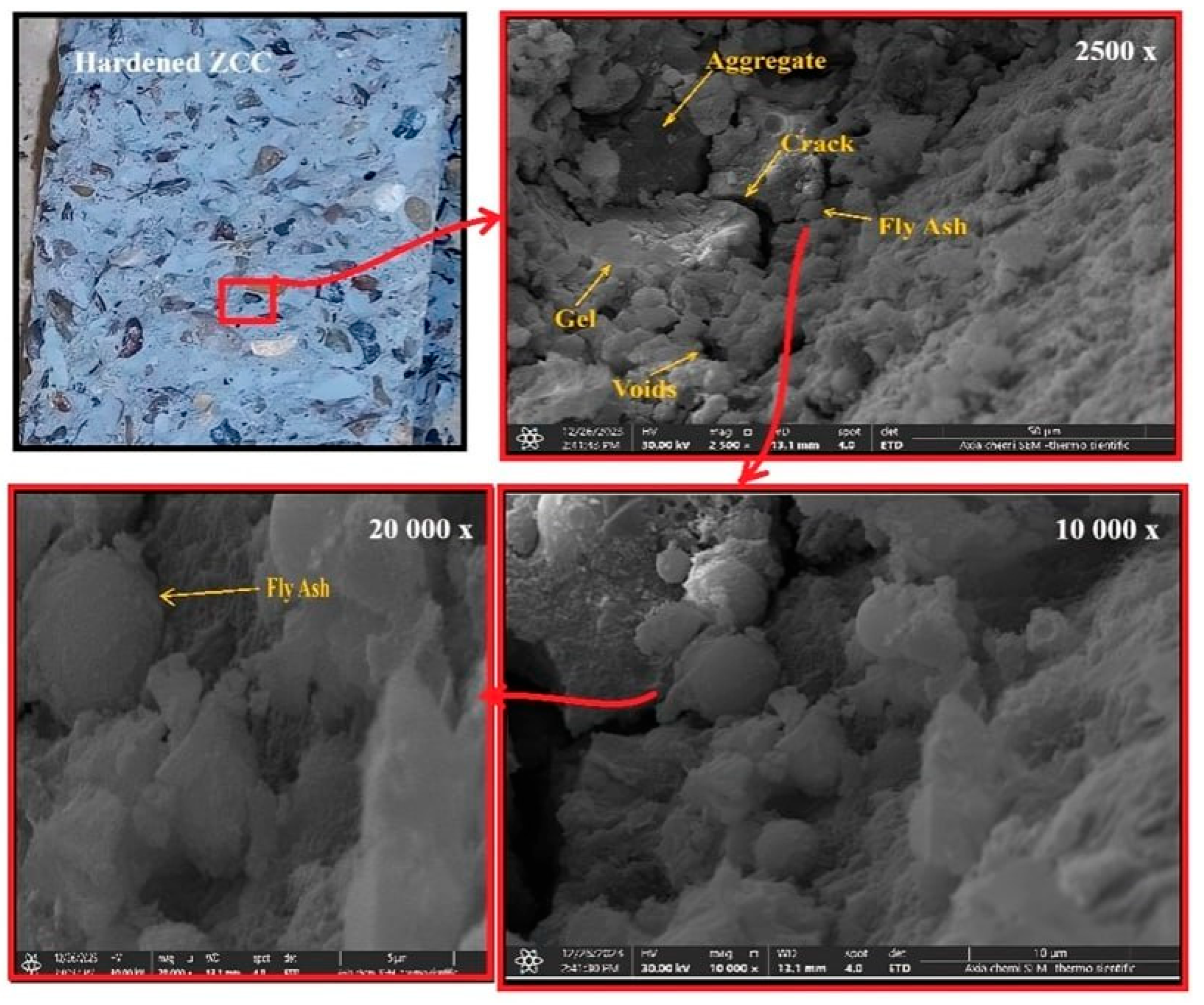

2.1. Materials and Mix Design

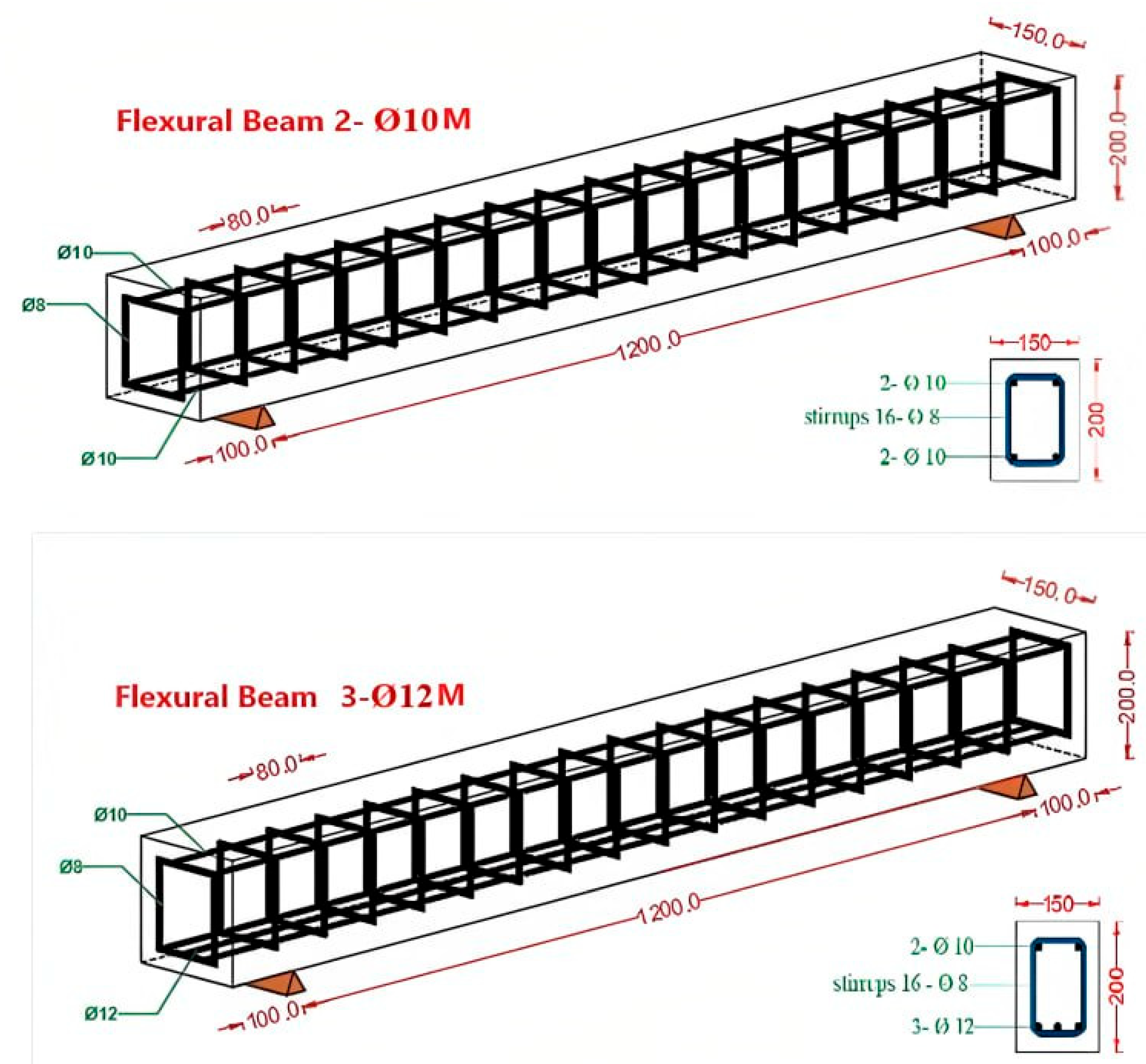

2.2. Beam Specimens and Reinforcement Details

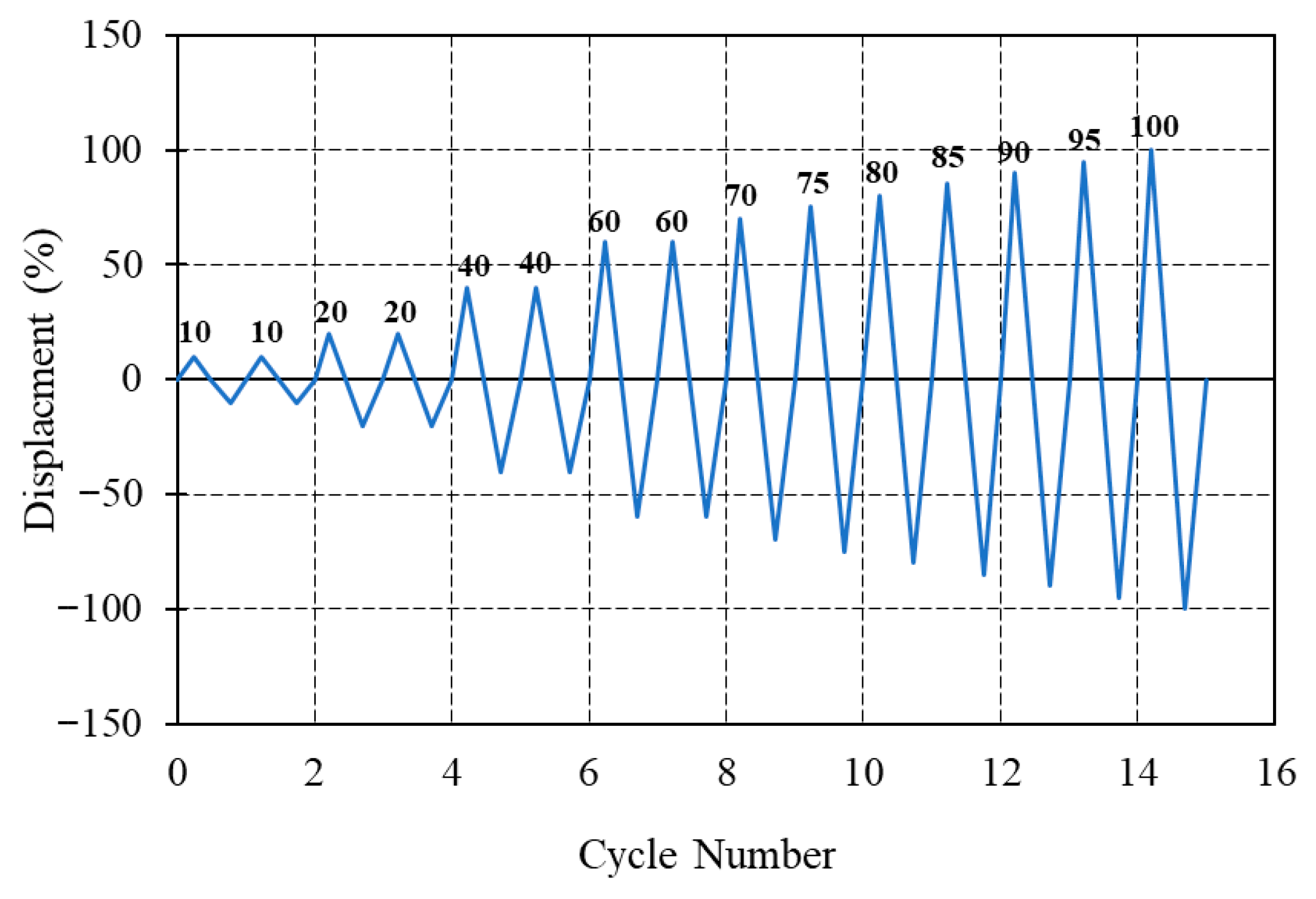

2.3. Testing Setup and Loading Procedure

2.4. Instrumentation and Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

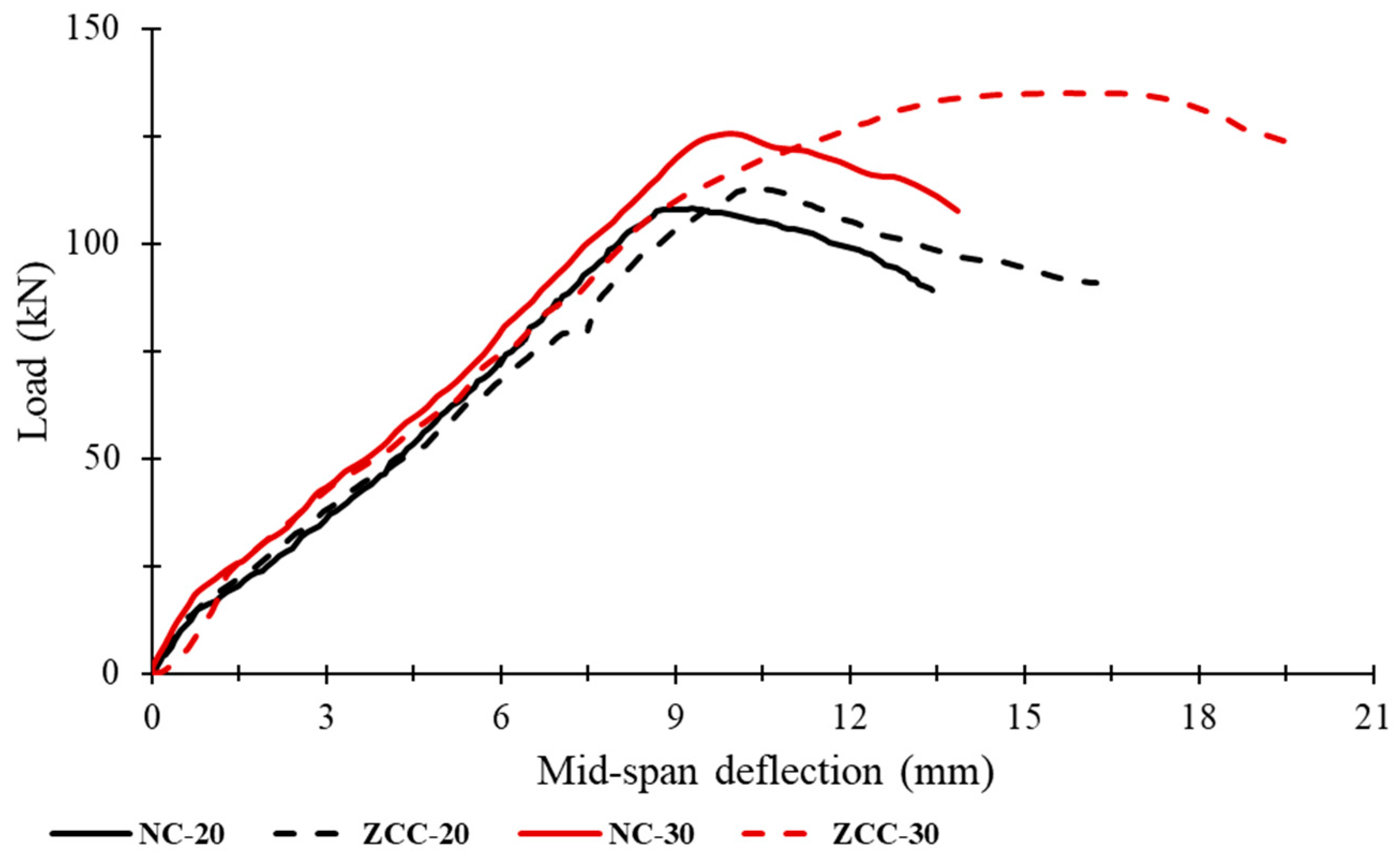

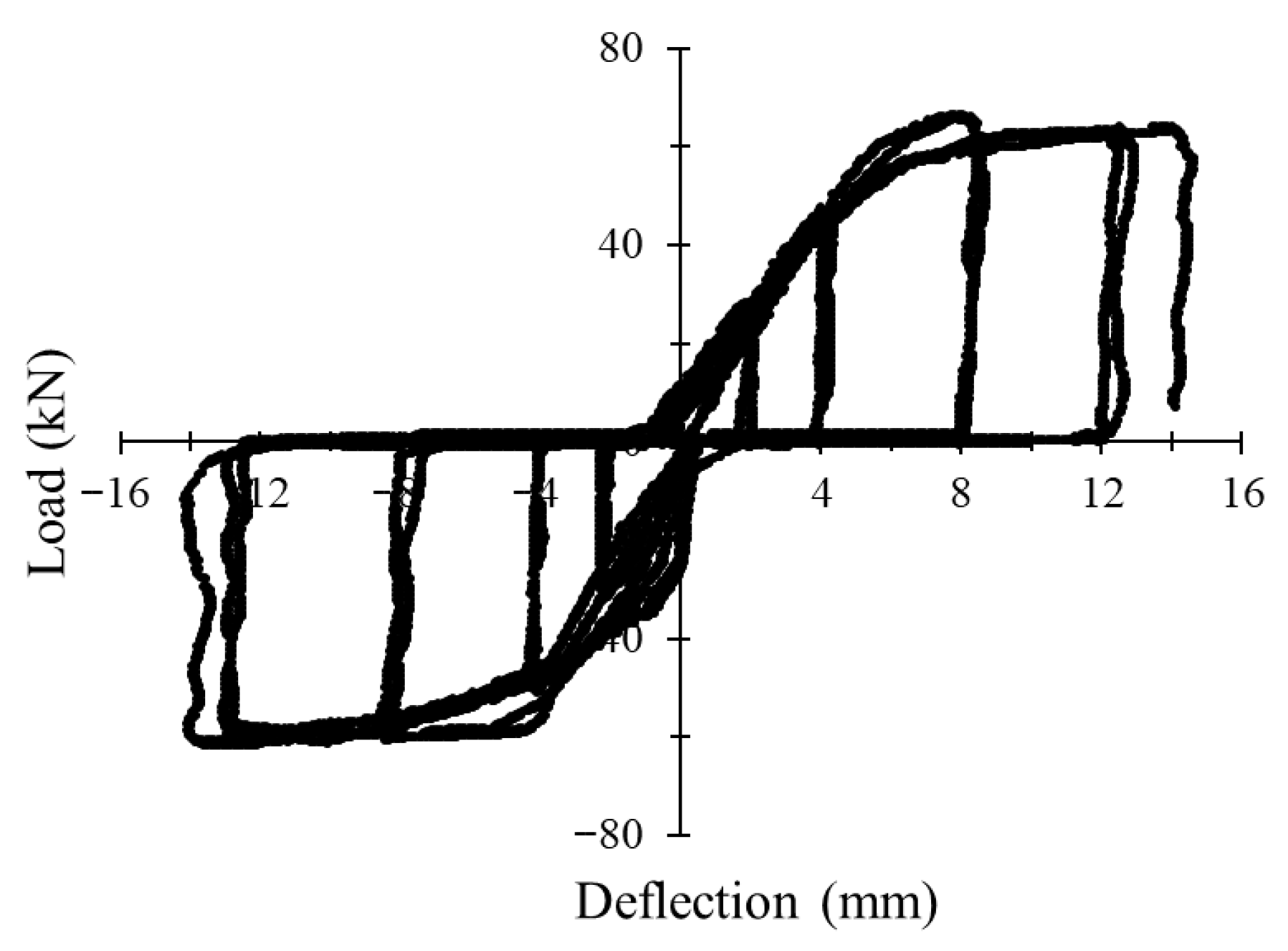

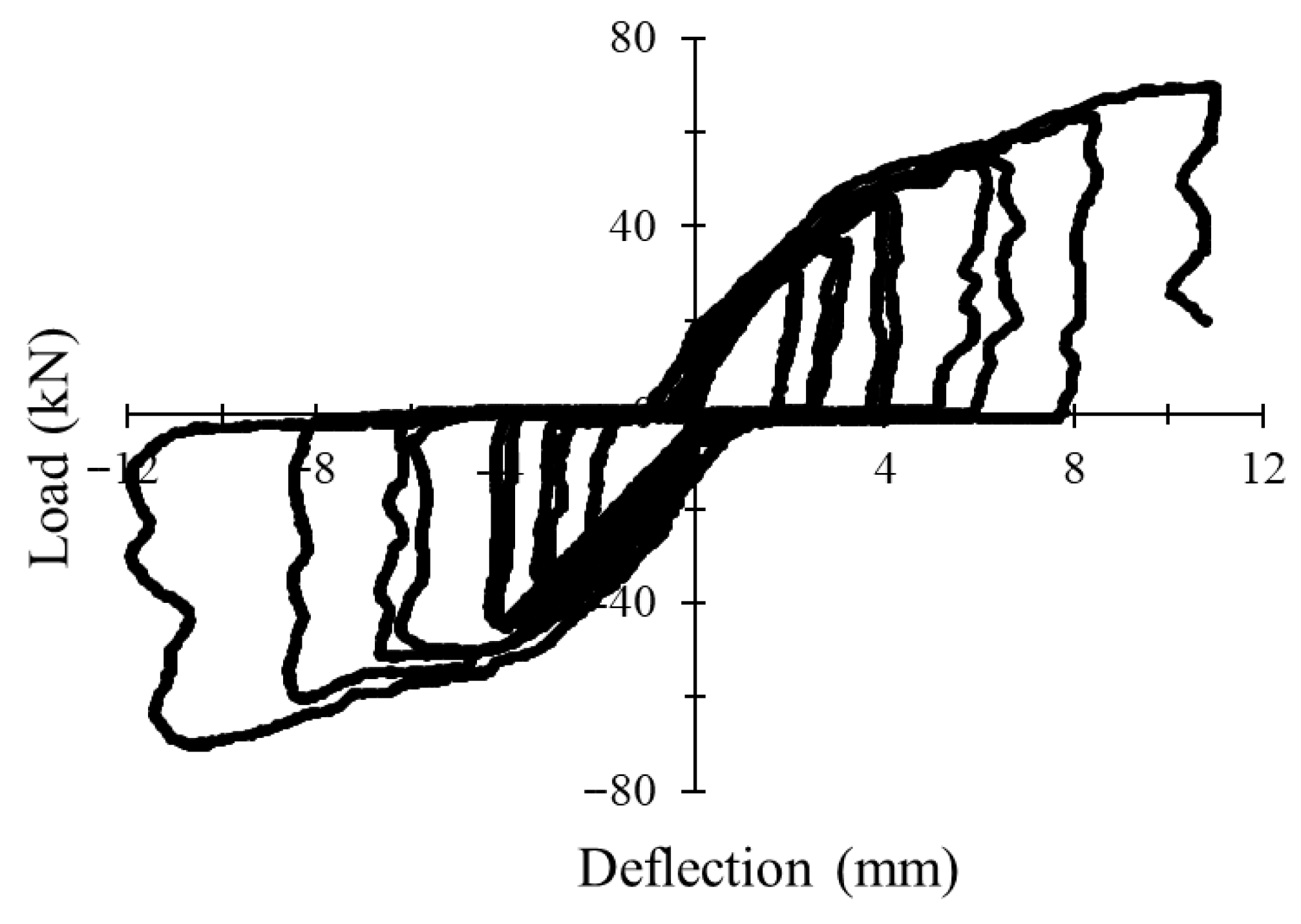

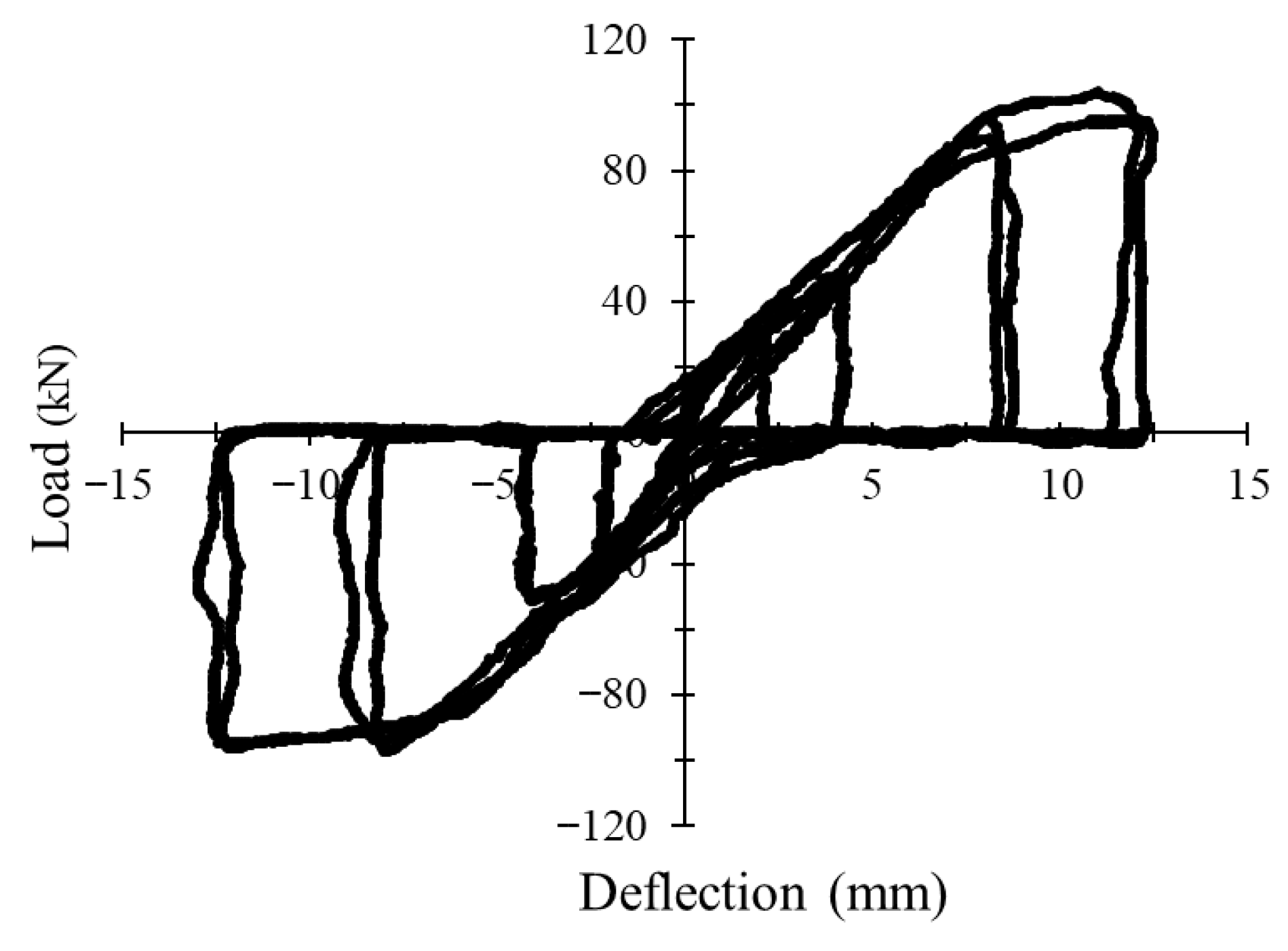

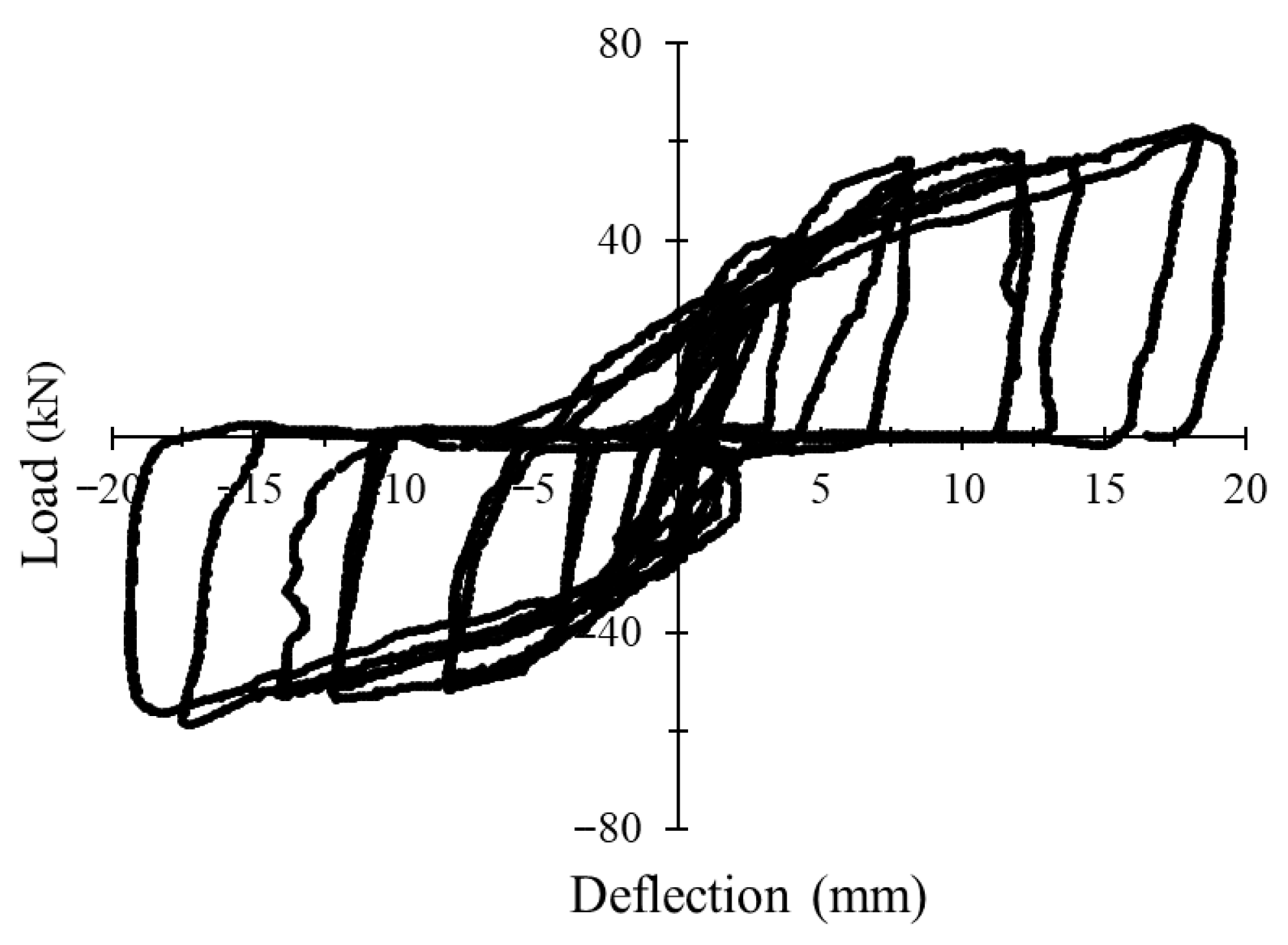

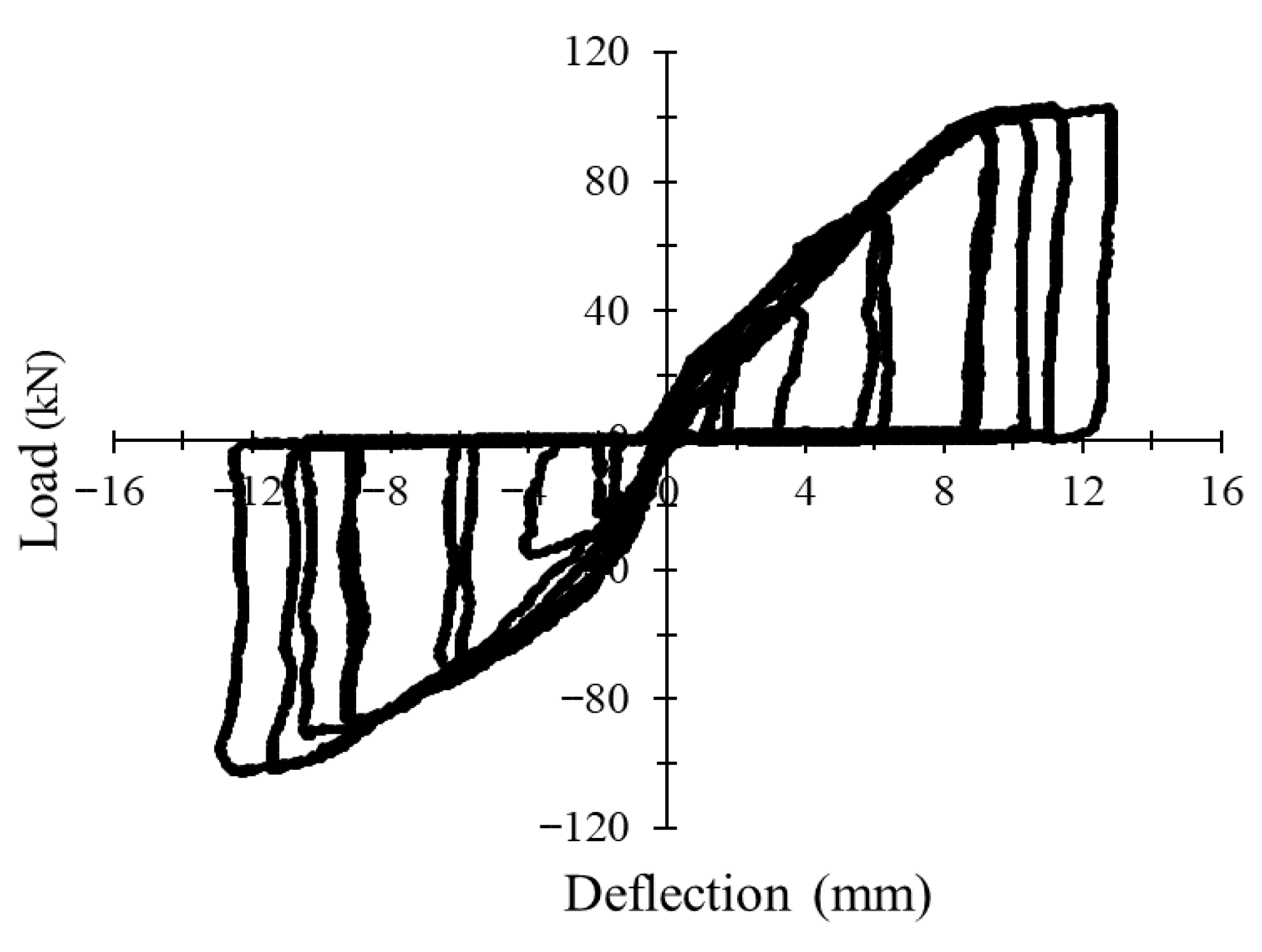

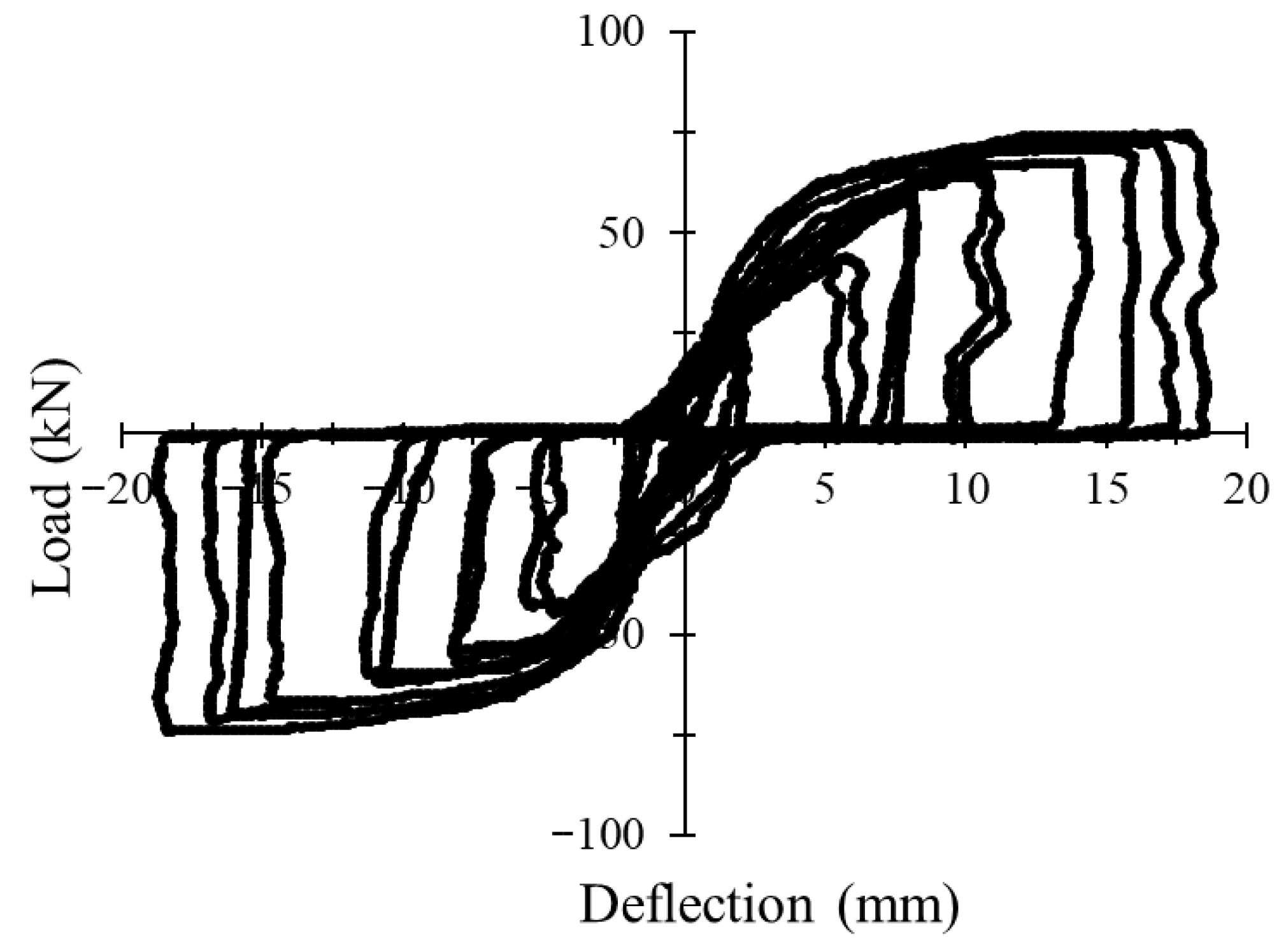

3.1. Load–Deflection Behavior Under Monotonic and Cyclic Loading

3.2. Energy Absorption Capacity and Ductility

3.3. Cracking Patterns and Failure Modes

3.4. Reinforcement Ratio Effects

3.4.1. Influence of Reinforcement Ratio Under Monotonic Loading

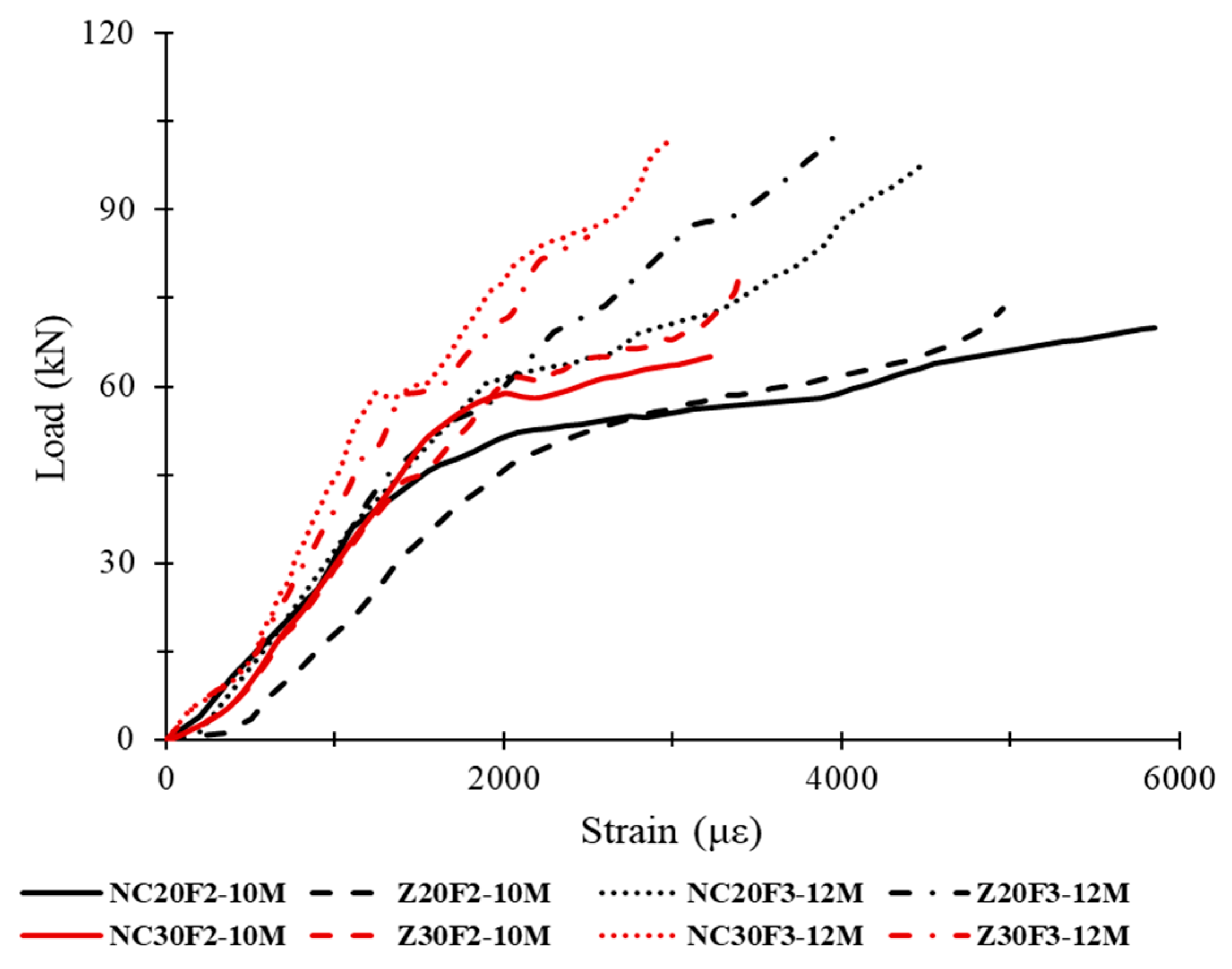

3.4.2. Load–Strain Behavior Under Monotonic Loading

3.4.3. Influence of Reinforcement Ratio Under Cyclic Loading

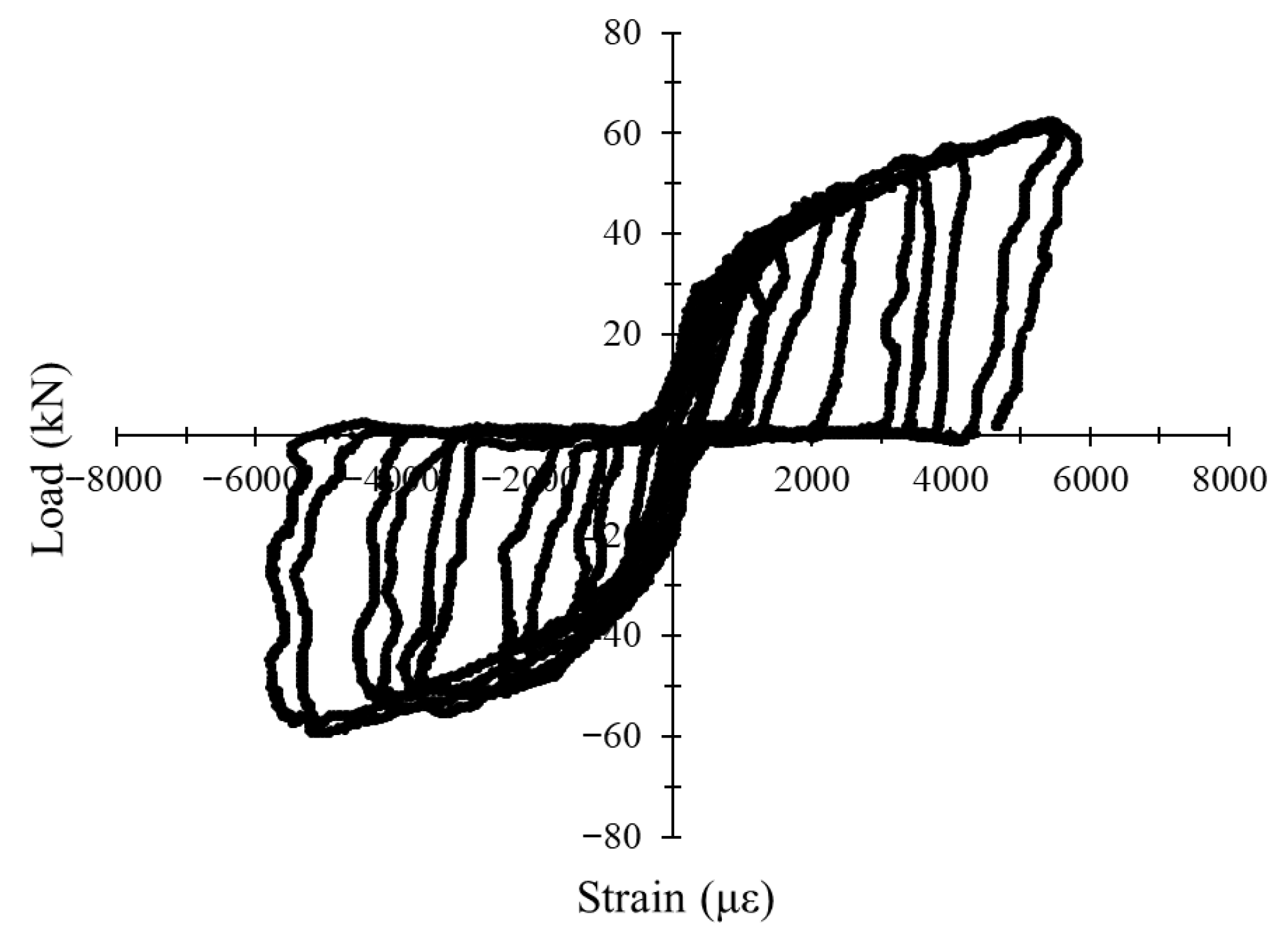

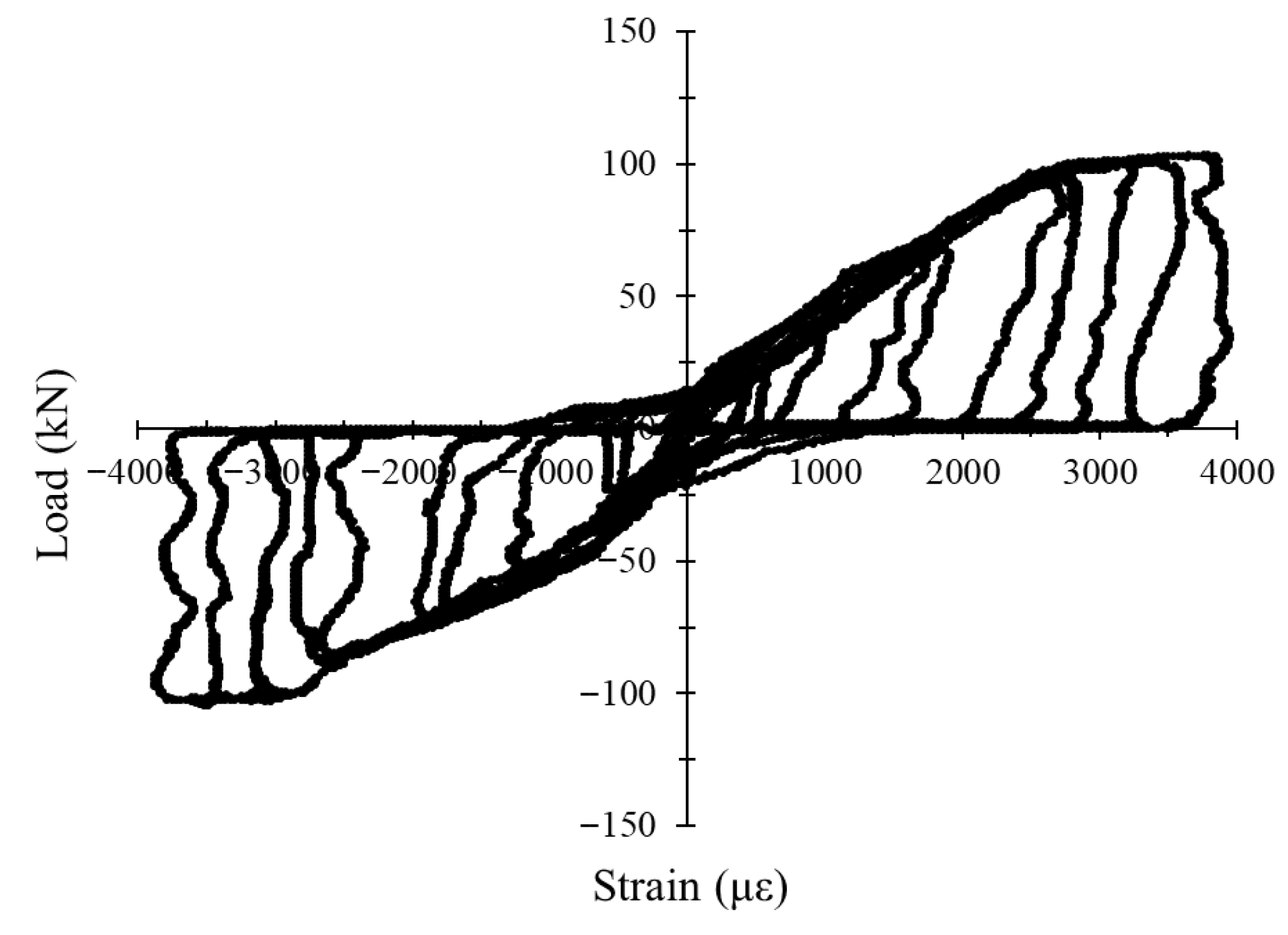

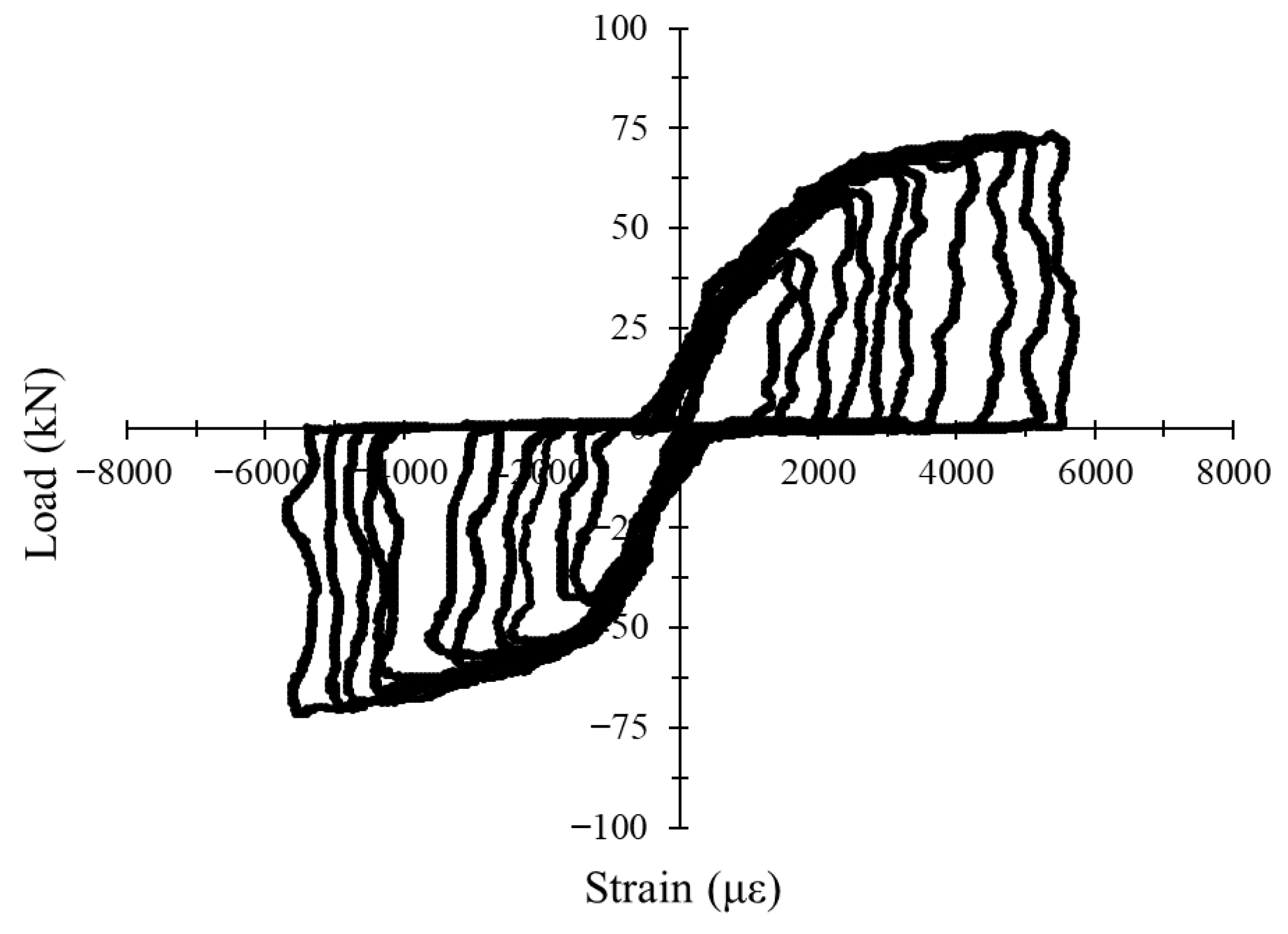

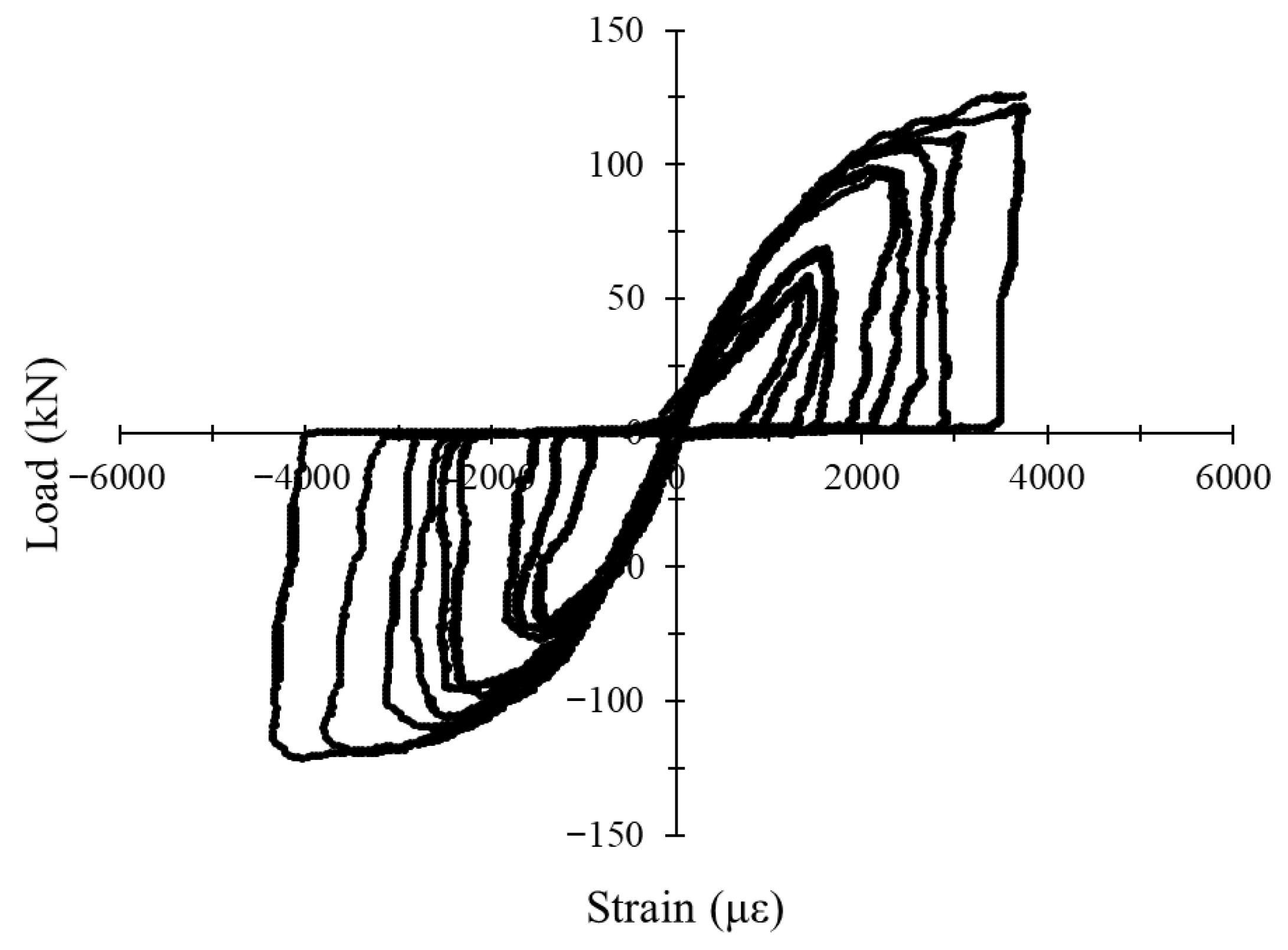

3.4.4. Load–Strain Hysteresis Response Under Cyclic Loading

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nehdi, M.L.; Marani, A.; Zhang, L. Is Net-Zero Feasible? Systematic Review of Cement and Concrete Decarbonization Technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 191, 114169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Masanet, E.; Tiwari, A.; Akolawala, S. Decarbonizing Concrete: Deep Decarbonization Pathways for the Cement and Concrete Cycle in the United States, India, and China; Industrial Sustainability Analysis Laboratory, Northwestern University: Evanston, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Watari, T.; Cao, Z.; Hata, S.; Nansai, K. Efficient Use of Cement and Concrete to Reduce Reliance on Supply-Side Technologies for Net-Zero Emissions; The University of Tokyo: Kashiwa, Japan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Worrell, E.; Boyd, G. Bottom-up estimates of deep decarbonization of U.S. manufacturing in 2050. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbhuiya, S.; Kanavaris, F.; Das, B.B.; Idrees, M. Decarbonising Cement and Concrete Production: Strategies, Challenges and Pathways for Sustainable Development. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidovits, J. Properties of Geopolymer Cements. J. Therm. Anal. 1991, 37, 1633–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provis, J.L.; Bernal, S.A. Geopolymers and Related Alkali-Activated Materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2014, 44, 299–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, K.M.; Sojobi, A.O.; Zhang, L.W. Green Concrete: Prospects and Challenges. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 156, 1063–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasim, M.; Abadel, A.; Abu Bakar, B.H.; Alshaikh, I.M.H. Future Directions for the Application of Zero-Carbon Concrete in Civil Engineering—A Review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldred, J.; Day, J. Is Geopolymer Concrete a Suitable Alternative to Traditional Concrete? In Proceedings of the 37th Conference on Our World in Concrete & Structures, Singapore, 29–31 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Athira, V.S.; Charitha, V.; Athira, G.; Bathiudeen, A. Agro-Waste Ash-Based Alkali-Activated Binder: Cleaner Production of Zero-Cement Concrete for Construction. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 125429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassoon, M.M.; Qissab, M.A. Performance of Zero Cement Concrete Synthesized from Fly Ash: A Critical Review. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 437, 04002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hason, M.M.; Al-Janabi, M.A.Q. Behavior of Zero Cement Reinforced Concrete Slabs under Monotonic and Impact Loads: Experimental and Numerical Investigations. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassoon, M.M.; Qissab, M.A. Behavior of Reinforced Zero Cement Concrete Slabs under Monotonic Load. Al-Nahrain J. Eng. Sci. 2024, 27, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardjito, D.; Rangan, B.V. Development and Properties of Low-Calcium Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Concrete; Research Report GC1; Faculty of Engineering, Curtin University of Technology: Perth, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.T.; Ji, X.S.; Sarker, P.K.; Tang, J.H.; Ge, L.Q.; Xia, M.S.; Xi, Y.Q. A Comprehensive Review on the Applications of Coal Fly Ash. Earth Sci. Rev. 2015, 141, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jabali, H.M.; El-Latief, A.A.; Ezz, M.S.; Khairy, S.; Nada, A.A. GGBFS- and Red-Mud-Based Alkali-Activated Concrete Beams: Flexural, Shear and Pull-Out Test Behavior. Civ. Eng. J. 2024, 10, 1494–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinaei, H.; Shariati, M.; Abna, A.H.; Aghaei, M.; Shariati, A. Evaluation of Reinforced Concrete Beam Behavior Using Finite Element Analysis by ABAQUS. Sci. Res. Essays 2012, 7, 2002–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, U.P.; Kumar, B.S.C. Flexural Behaviour of Reinforced Geopolymer Concrete Beams with GGBS and Metakaolin. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2016, 7, 260–277. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, B.S.C.; Ramesh, K. Analytical Study on Flexural Behaviour of Reinforced Geopolymer Concrete Beams by ANSYS. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 455, 012065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendapudi, S. Studies on Flexural Behavior of Geopolymer Concrete Beams with GGBS. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2019, 7, 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, P.; Sarker, P.K. Flexural strength and elastic modulus of ambient-cured blended low-calcium fly ash geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 130, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardjito, D.; Wallah, S.E.; Sumajouw, D.M.J.; Rangan, B.V. On the development of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. ACI Mater. J. 2004, 101, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.; Hu, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, G.; Hao, Z.; Wang, L. A new ventilation system for extra-long railway tunnel construction by using the air cabin relay: A case study on optimization of air cabin parameters length. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 45, 103480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, P.K.; Kelly, S.; Yao, Z.T. Effect of fire exposure on cracking, spalling and residual strength of fly ash geopolymer concrete. Mater. Des. 2018, 63, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo, P.; García del Angel, G.; Setién, J.; Soto, A.; Thomas, C. Feasibility of silicomanganese slag as cementitious material and as aggregate for concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 364, 129938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, G.A.; Sallam, E.A.; Elbelacy, A.N. Structural Behavior of Reinforced Concrete Beams Containing Nanomaterials Subjected to Monotonic and Cyclic Loadings. Buildings 2022, 12, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C39/C39M-23; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C496/C496M-22; Standard Test Method for Splitting Tensile Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM C78/C78M-21; Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Concrete (Using Simple Beam with Third-Point Loading). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C143/C143M-20; Standard Test Method for Slump of Hydraulic-Cement Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Hamad, A.J.; Sldozian, R.J.A. Flexural and Flexural Toughness of Fiber-Reinforced Concrete—American Standard Specifications Review. GRD J. Eng. 2019, 4, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ghamarian, N.; Hanim, M.A.A.; Penjumras, P.; Majid, D.L.A. Effect of Fiber Orientation on the Mechanical Properties of Laminated Polymer Composites. In Encyclopedia of Materials: Composites; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 746–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee 318. Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete () and Commentary; American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Concrete Type | fcu (Mpa) | f’c (Mpa) | ft (Mpa) | fr (Mpa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC-20 | 24.32 | 21.89 | 2.02 | 3.06 |

| NC-30 | 36.03 | 32.07 | 2.92 | 3.71 |

| ZCC-20 | 26.90 | 23.94 | 2.53 | 3.11 |

| ZCC-30 | 37.37 | 34.38 | 3.06 | 4.04 |

| Concrete Type | Slump Test Result (mm) |

|---|---|

| NC-20 | 55 |

| NC-30 | 80 |

| ZCC-20 | 50 |

| ZCC-30 | 75 |

| Mix Type | Target Strength (Mpa) | Cement (kg/m3) | Fly Ash (kg/m3) | Fine Aggregate (kg/m3) | Coarse Aggregate (kg/m3) | Water (L/m3) | NaOH Solution (kg/m3) | Na2SiO3 Solution (kg/m3) | Superplasticizer (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC-20 | 20 | 350 | – | 650 | 1200 | 175 | – | – | 5.25 |

| NC-30 | 30 | 450 | – | 600 | 1180 | 180 | – | – | 6.75 |

| ZCC-20 | 20 | – | 400 | 640 | 1180 | – | 40 | 80 | 5.00 |

| ZCC-30 | 30 | – | 450 | 600 | 1160 | – | 45 | 90 | 6.00 |

| Group | Concrete Type | f′c (MPa) | Longitudinal Reinforcement | Stirrups | Loading Type | Number of Beams |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC-20 | NC | 20 | 2Ø10, 3Ø12 | Ø8 @100 mm | Monotonic/Cyclic | 4 |

| NC-30 | NC | 30 | 2Ø10, 3Ø12 | Ø8 @100 mm | Monotonic/Cyclic | 4 |

| ZCC-20 | ZCC | 20 | 2Ø10, 3Ø12 | Ø8 @100 mm | Monotonic/Cyclic | 4 |

| ZCC-30 | ZCC | 30 | 2Ø10, 3Ø12 | Ø8 @100 mm | Monotonic/Cyclic | 4 |

| Group | Longitudinal Reinforcement | Pcr (kN) | ∆cr (mm) | Pu (kN) | ∆u (mm) | K (kN/mm) | Energy Absorption (kN·mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC-20 | 2Ø10 | 11.81 | 0.86 | 71.68 | 11.77 | 6.09 | 1148.8 |

| ZCC-20 | 2Ø10 | 13.80 | 0.76 | 76.52 | 13.27 | 5.77 | 1334.9 |

| NC-30 | 2Ø10 | 19.16 | 1.56 | 75.93 | 12.60 | 6.03 | 1305.3 |

| ZCC-30 | 2Ø10 | 16.89 | 1.48 | 85.01 | 21.72 | 3.91 | 2428.1 |

| NC-20 | 3Ø12 | 13.89 | 0.71 | 107.90 | 9.31 | 11.59 | 1099.1 |

| ZCC-20 | 3Ø12 | 14.54 | 0.77 | 112.60 | 10.57 | 10.65 | 1296.5 |

| NC-30 | 3Ø12 | 19.02 | 0.75 | 125.25 | 10.21 | 12.27 | 1413.4 |

| ZCC-30 | 3Ø12 | 24.12 | 1.35 | 134.92 | 16.22 | 8.32 | 2865.8 |

| Group | Longitudinal Reinforcement | No. of Cycles to Failure | ∆y (mm) | Pu (kN) | ∆u (mm) | Flexural Ductility | Initial Stiffness (K) (kN/mm) | Energy Absorption (kN.mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC-20 | 2Ø10 | 9 (Up) | 5.039 | 65.81 | 14.14 | 2.81 | 4.66 | 5913.96 |

| ZCC-20 | 2Ø10 | 11 (Up) | 4.254 | 61.24 | 19.43 | 4.57 | 3.15 | 7844.52 |

| NC-30 | 2Ø10 | 10 (Up) | 3.145 | 70.57 | 11.03 | 3.51 | 6.40 | 3713.36 |

| ZCC-30 | 2Ø10 | 12 (Up) | 4.257 | 73.69 | 18.32 | 4.30 | 4.02 | 11,899.33 |

| ZCC-20 | 3Ø12 | 11 (Down) | 2.904 | 102.42 | 12.54 | 4.32 | 8.17 | 7728.19 |

| NC-30 | 3Ø12 | 8 (Up) | 7.989 | 103.49 | 12.46 | 1.56 | 8.31 | 6156.81 |

| ZCC-30 | 3Ø12 | 12 (Up) | 6.080 | 129.25 | 15.86 | 2.61 | 8.15 | 12,351.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Al-Janabi, M.A.Q.; Al-Jeznawi, D.; Nasser, R.T.; Bernardo, L.F.A.; Pinto, H.A.S. Flexural Performance of Geopolymer-Reinforced Concrete Beams Under Monotonic and Cyclic Loading: Experimental Investigation. Buildings 2026, 16, 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010209

Al-Janabi MAQ, Al-Jeznawi D, Nasser RT, Bernardo LFA, Pinto HAS. Flexural Performance of Geopolymer-Reinforced Concrete Beams Under Monotonic and Cyclic Loading: Experimental Investigation. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):209. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010209

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Janabi, Musab Aied Qissab, Duaa Al-Jeznawi, Rana Talib Nasser, Luís Filipe Almeida Bernardo, and Hugo Alexandre Silva Pinto. 2026. "Flexural Performance of Geopolymer-Reinforced Concrete Beams Under Monotonic and Cyclic Loading: Experimental Investigation" Buildings 16, no. 1: 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010209

APA StyleAl-Janabi, M. A. Q., Al-Jeznawi, D., Nasser, R. T., Bernardo, L. F. A., & Pinto, H. A. S. (2026). Flexural Performance of Geopolymer-Reinforced Concrete Beams Under Monotonic and Cyclic Loading: Experimental Investigation. Buildings, 16(1), 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010209