Abstract

The urgent need for sustainable innovation in the construction industry necessitates a reevaluation of how architecture engages with materials and fabrication processes. This paper introduces tailored fiber placement (TFP) as a novel fabrication method with significant potential for advancing sustainable architectural practice. Originally developed for aerospace and automotive applications, TFP enables stress-oriented fiber alignment, offering precision, material efficiency, and lifecycle-conscious design opportunities. To articulate these capabilities, the paper examines four case studies at multiple scales. Ranging from small-scale seating to medium-scale façade components, these examples demonstrate TFP’s ability to enable mold-less forming and integrative fabrication in support of sustainable construction. Through digitally programmed fiber orientations, the cases achieve both structural and geometric requirements while minimizing waste and improving workflow efficiency. This research positions TFP as a material-aware and performance-driven approach to sustainable architectural production. By bridging material, design, and fabrication, TFP contributes to more circular, adaptable, and efficient construction systems.

1. Introduction

Architecture has always been driven by the need for construction innovation, shaped by evolving cultural, social, and technological contexts. In recent decades, this drive has become increasingly influenced by environmental concerns, calling for a fundamental shift in how buildings are designed and constructed [1]. The climate crisis, resource depletion, and the rising volume of construction waste demand more responsible and efficient practices.

1.1. Background

The building industry significantly impacts the global environment, demanding vast resources and generating substantial waste. Within the European Union, the built environment accounts for approximately 50% of all extracted materials and contributes over 35% of total waste generation [2]. Furthermore, greenhouse gas emissions associated with material extraction and construction product manufacturing represent an estimated 5–12% of total national emissions. These figures highlight the sector’s critical role in the climate crisis. Notably, improving material efficiency alone could reduce up to 80% of emissions within the sector [2,3].

In this context, innovation in construction methods is essential. Developing and adopting innovative production methods that integrate precision, minimize material waste, extend component lifespans, and enable reuse and recycling is essential for building a more resilient and sustainable construction industry.

1.2. Tailored Fiber Placement (TFP) Technology

Among the emerging strategies for sustainable construction, tailored fiber placement (TFP) stands out as a promising technology. TFP was developed in the 1990s at the Leibniz Institute of Polymer Research Dresden, originally designed for high-performance sectors such as aerospace and the automotive industry. This technique is developed from the standard embroidery method. It enables the production of lightweight, structurally optimized, and material-efficient composite components by tailoring fiber orientations to align with specific stress fields [4,5,6].

Process of TFP

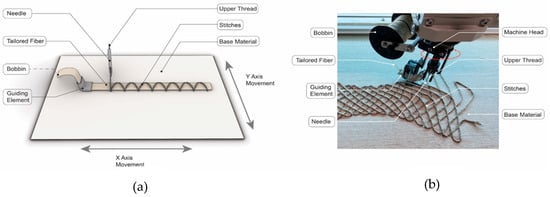

Figure 1 illustrates the general principle of the TFP process. It functions by precisely depositing continuous fiber roving along digitally defined reinforcement paths onto a base material, where it is fixed in place with a zigzag stitch using a sewing thread, while the base material is moved in the X and Y directions according to those paths. The base material can be either a fabric or a nonwoven textile, and the roving may consist of carbon, glass, or natural fiber [4,5,6]. Additionally, wall thickness can be varied locally by layering multiple fibers on top of each other [5]. In addition to the physical fabrication process, the TFP workflow depends on dedicated software to translate digital design information into machine-readable fabrication instructions. Fiber placement paths are generated using EDOpath 2.0, a specialized CAD/CAM environment developed for TFP systems. This software enables the definition of continuous fiber trajectories, stitch parameters, and local layer densities directly within a digital model. It converts these parametric fiber layouts into machine language, including stitch paths and motion commands, allowing the programmed fiber orientations to be executed with high accuracy on TFP machines [4,5,6,7]. After fiber placement, the TFP-reinforced textile is consolidated using a binding matrix and subsequently cured to achieve structural integrity [7,8].

Figure 1.

Principle of tailored fiber placement: (a) Illustration of the TFP process; (b) Photo illustration of the TFP Process with natural-based fiber and non-woven base layer.

1.3. TFP in Industrial Applications

1.3.1. TFP in Automotive and Aerospace Industry

TFP has been applied in the automotive sector to address performance and sustainability demands in complex components. Coppola, Huelskamp, Tanner, Rapking, and Ricchi (2023) [9] developed a TFP-fabricated connecting rod, which serves as a strong example of how fiber orientation can be strategically designed using separate preforms to meet the structural requirements. In this case, the design used 0° parallel direction of fibers that followed the primary load direction, while ±45° diagonal direction layers enhanced cross-directional stability and prevented fiber separation. This specific tailored fiber arrangement improved the strength and reduced unnecessary material use of the component.

Similarly, in aerospace applications, Uhlig, Spickenheuer, Bittrich, and Heinrich (2013) [10] applied TFP to develop a bladed rotor for turbomolecular pumps. In this case, TFP facilitates the production of the preforms with both radial and circular fiber orientations. This directional combination is designed due to different parts of the rotor experiencing different structural demands which are required for production utilizing the TFP.

Additionally, the effectiveness of TFP in adding stress-aligned local reinforcements is demonstrated by Gliesche (2003) [11], where the method was applied to tensile plates with open holes by accurately transferring calculated stress paths onto fiber reinforcements. Although this TFP application is constrained by reliance on precise finite-element modeling and specific controlled loading conditions, these constraints also reveal TFP’s capacity to translate performance logic into fabrication logic, potentially enabling the direct integration of connection details such as bolt holes or joints within structurally informed components. From a sustainability perspective, while these applications in high-performance industries confirm the structural performance of TFP, they primarily rely on synthetic fiber composites, motivating further exploration of alternative sustainable materials and application contexts.

Inspired by established practices in automotive and aerospace industries, these applications indicate TFP’s potential to enable directional material behavior through controlled fiber pathing, which is crucial for lightweight and performance-based design. By accommodating precise material placement and shape-conforming fabrication, TFP directly responds to the challenges commonly faced in automotive and aerospace manufacturing, where components often involve complex geometries and loading conditions that lead to high material waste and limited geometrical flexibility in aligning material layers [9]. These features make TFP a valuable strategy for achieving more sustainable and efficient production.

1.3.2. TFP in Architecture and the Building Industry

Given its potential for precision, material efficiency, and capacity, TFP offers a powerful tool for advancing sustainable construction not only to engineers but architects as well.

In recent decades, there has been a growing research interest in applying TFP to sustainable construction, driven by the need to reduce material waste and increase design flexibility within the building industry. Institutions such as the BioMat Copenhagen Research Centre at Aalborg University and the BioMat research group at the Institute of Building Structures and Structural Design (ITKE) at the University of Stuttgart have led significant research and development efforts in this area.

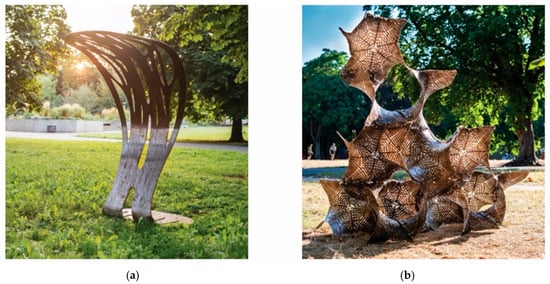

Importantly, BioMat’s research not only extends beyond the use of conventional synthetic fibers like carbon or glass, exploring the substitution of these with fibers derived from annually renewable resources such as flax as a reinforcement, but also further investigates TFP’s programmability by incorporating computational structural optimization to place fibers efficiently based on the component’s stress field, precisely where only structural performance is required. Unlike typical fiber orientations in the automotive or aerospace industries, where fibers are distributed across entire preforms, BioMat’s approach enables optimized, selective reinforcement. This strategy is exemplified in the Tailored Bio-composite Mock-Up 2019 [12] (Figure 2a) and Flat to Spatial Mockup 2020 [13] (Figure 2b). Both projects demonstrate how BioMat’s structurally informed approach to TFP enables further material reduction while also showcasing TFP’s potential for material efficiency and its adaptability to the specific demands of sustainable construction.

Figure 2.

Architectural-scaled TFP mockups produced by BioMat Group: (a) Tailored Bio-composite Mockup 2019 [12]; (b) Flat to Spatial Mockup 2020 [13].

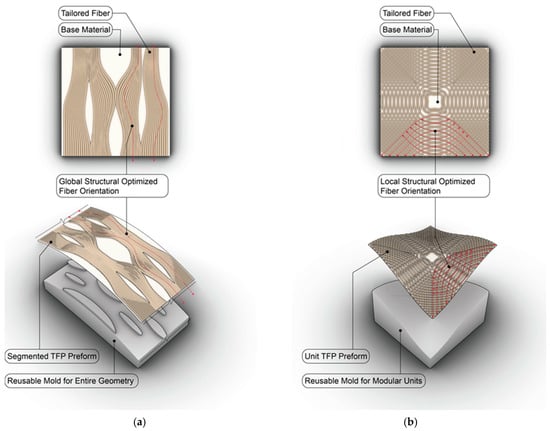

While both cases exemplify TFP’s capability for structurally optimized fiber placement, they differ fundamentally in fabrication logic. The Tailored Bio-composite Mock-Up 2019 employed a reusable mold customized for a larger scale, lightweight, free-standing canopy geometry, with fiber orientation distributed through global structural optimization (Figure 3a). In contrast, The Flat to Spatial Mockup 2020 adopted a modular fabrication strategy, using a smaller reusable mold to produce repeatable units, each optimized locally with discrete reinforcements (Figure 3b). Table 1 illustrates these two distinct design and fabrication logics.

Figure 3.

TFP design strategies in two mock-ups: (a) Global structural optimization of fiber orientation and customized reusable mold across the entire geometry; (b) Local structural optimized fiber orientation and reusable mold for modular units.

Table 1.

Overview of two TFP-based architectural mock-ups.

Compared to the 2019 mock-up strategy, which required a large, less flexible mold for globally optimized fiber placement, the 2020 approach provides greater flexibility and scalability in construction. Its modular and locally reinforced fiber placement method allows for more agile and resource-efficient development. Since the development of the 2020 mock-up, this approach has been primarily used and further developed within BioMat’s ongoing research.

1.4. Scope

This research investigates the potential of tailored fiber placement (TFP) as a sustainable fabrication strategy within architectural design and construction. Analyzing early architectural applications of TFP positions them as a foundation for a broader investigation into how this innovative technique can contribute to sustainable architecture through its fabrication flexibility and material efficiency.

This paper contributes by introducing TFP as a design-integrated fabrication method for architectural applications, demonstrated through the capability of digitally programmed fiber placement to inform geometry and forming strategies, extending its role beyond conventional structural reinforcement.

The scope of the research focuses on TFP’s potential to enable novel and sustainable architectural construction methodologies, including mold-less forming and the integration of multiple fabrication processes, building upon a modular and locally reinforced fiber placement approach and the utilization of nature-based materials. The research examines a series of architectural case studies to analyze the relationship between digital design, fiber placement strategies, and geometric forming.

Mechanical characterization and performance evaluation of TFP-reinforced bio-composites are addressed in separate, complementary research and are therefore not the primary focus of this paper. Accordingly, this study prioritizes architectural relevance, fabrication logic, and design potential as the main criteria for case study selection and analysis, as presented in Section 2.

2. Case Studies

To demonstrate how these methodologies are applied in architectural contexts, a selection of case studies is analyzed, emphasizing TFP’s role in enabling new directions in design and construction.

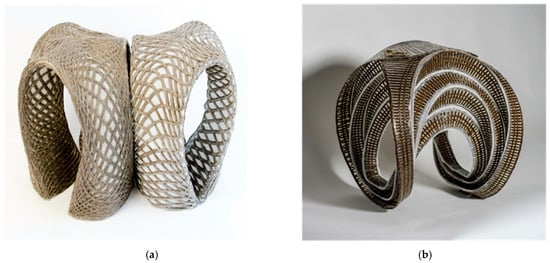

2.1. Curve-Folding and Mold-Less Fabrication

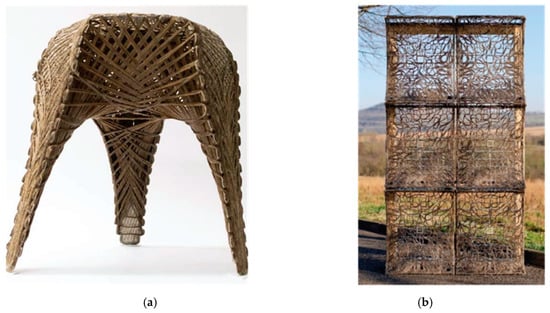

Projects such as FibrFoldr [14] (Figure 4a) and FlaxPack [15] (Figure 4b) have explored how curve folding, achieved by precisely controlling fiber orientation through the TFP process, can produce structurally efficient components with minimal or no formwork in the three-dimensional forming process.

Figure 4.

Photos of prototype fabricated through TFP, utilizing curve-folding strategies to enable mold-less forming: (a) FibrFoldr prototype [14]; (b) FlaxPack prototype [15].

2.1.1. FibrFoldr (2020)

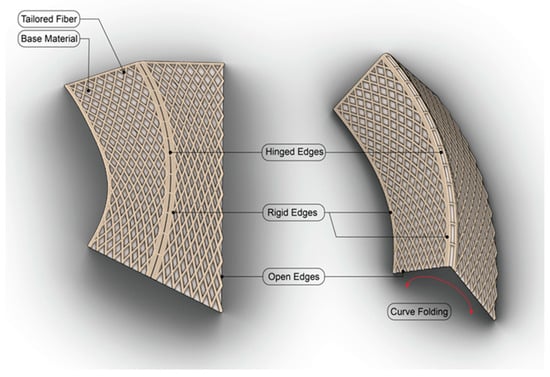

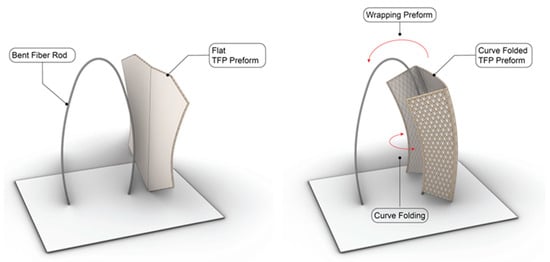

The FibrFoldr [14] project is an example of applying curve folding through TFP for mold-less fabrication. It demonstrates how fiber orientation can be strategically programmed to enable folding without relying on conventional molds.

In this project, the fiber orientation was defined based on three types of edges: rigid edges, hinged edges, and open edges. Among these, hinged edges are specifically designed to allow curvature during forming and serve as the primary mechanism for controlled folding. This is achieved by aligning fiber placement with the curved creases in the geometry to create flexible regions, while an additional layer of fibers crosses the crease at shallow angles to accommodate folding and maintain structural integrity. In contrast, rigid and open edges are defined to support form and overall continuity. By strategically programming these edges into the fiber orientation using TFP, a flat 2D preform can be transformed into a 3D structure through controlled curve folding (Figure 5). The final shape is then stabilized using bent glass fiber rods serving as minimal scaffolding to guide and secure the fold lines, eliminating the need for traditional molds (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Illustration of three defined edge types for guiding curved folding and fiber orientation.

Figure 6.

Illustration of mold-less forming with bent fiber rod scaffolding to stabilize the folded TFP preform.

2.1.2. FlaxPack (2024)

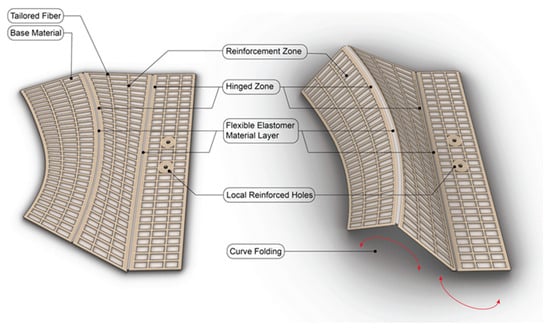

Building on the exploration in FibrFoldr, the FlaxPack [15] project significantly advances a more computationally informed TFP process to enable a curve folding strategy for mold-less fabrication without relying on additional tooling. To achieve this, FlaxPack employs advanced computational simulations to analyze folding behaviors.

Kangaroo Physics [16] was used to simulate the folding dynamics and evaluate deformation under realistic conditions. The simulation began with a flat mesh geometry used to define fold behavior through parametric hinge effects. Mountain and valley folds were created by assigning positive and negative bend angles, respectively, to generate opposing folding directions. After generating the folded geometry using Kangaroo Physics solver, the resulting folded 3D form was input into Karamba3D [17] to evaluate the structural performance.

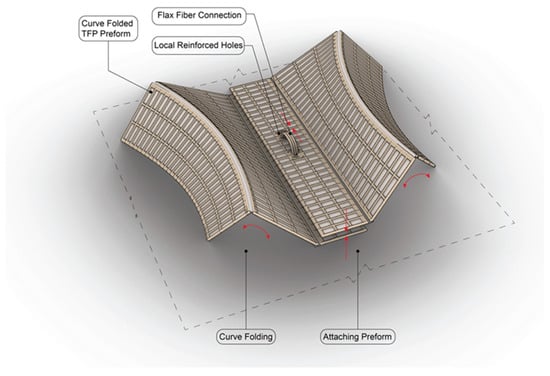

Simulation and structural analysis data directly guided a parametric path-planning algorithm for TFP fiber orientation, aligning the fiber layout with the desired folding behavior. The algorithm differentiated between fold and reinforcement zones and incorporated reinforced eye holes as connection points. To achieve compliant folding, a flexible elastomer layer (e.g., silicone) was selectively applied manually as a surface elastomeric coating to predefined fold zones after the TFP process while the preform remained flat prior to resin infusion. This approach maintained localized flexibility while surrounding areas were hardened (Figure 7). The tailored preform was then folded into a 3D stool and secured with manual stitching at the eye holes (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Illustration of computationally informed and generated folding and reinforcement zones, and the corresponding fiber orientation.

Figure 8.

Illustration of securing the folded 3D geometry through manual stitching at local reinforcement holes.

2.2. Integrative Fabrication Techniques

Expanding on the digitally informed use of TFP, this section investigates projects that combine TFP with manual techniques, flexible forming, and complementary fiber placement methods to expand its potential in integrative fabrication. These integrative approaches demonstrate how TFP can operate across both computational and craft-based contexts, opening new possibilities for adaptive and material-driven construction. Projects such as FlexFlax [18] (Figure 9a) and Bio-composite Tailored Facades [19] (Figure 9b) further illustrate the evolving role of TFP across different design scales and fabrication strategies.

Figure 9.

Photos of prototypes exploring integrative fabrication with TFP: (a) FlexFlax [18]; (b) one façade module from Bio-composite Tailored Facades [19].

2.2.1. FlexFlax (2020)

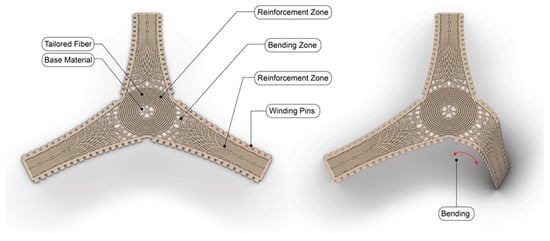

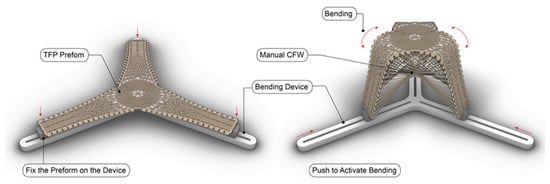

The FlexFlax 2020 [17] demonstrates integrative fabrication by combining TFP, flexible surface bending techniques, and coreless filament winding (CFW) to produce mold-less, lightweight structural systems. The fabrication process unfolds in three interdependent phases: Stitch, Bend, and Weave.

In the Stitch stage, TFP is used to implement a performance-driven fiber layout based on defined parameters of fiber orientation, local stiffness, bending behavior, and simplified topology optimization [20,21]. These differentiated patterns are embedded within an integrated TFP preform, combining reinforcement zones, such as the lower leg areas and top seating surface, where fiber placement is denser for structural strength, and the intermediate bending zones, where reduced fiber density allows for localized flexibility and deformation. Winding pins are also integrated to anchor the subsequent filament winding process (Figure 10). Then, in the Bend and Weave stages, the mold-less fabrication method is applied. During these phases, a bending-active scaffold is created to shape the two-dimensional TFP preform into a three-dimensional structure. This scaffold can be reused and adapted to produce different geometries. Finally, CFW is directly applied onto the bent TFP structure. The wound fibers not only reinforce the system but also lock the geometry into place, securing the final shape as part of the structural system itself (Figure 11). The stool structure was qualitatively validated through seating tests with participants of varying body weights.

Figure 10.

Illustration of a unified TFP preform integrating distinct reinforcement and bending zones with embedded winding pins.

Figure 11.

Illustration of a moldless forming strategy and process utilizing a reusable bending device for shaping TFP preform.

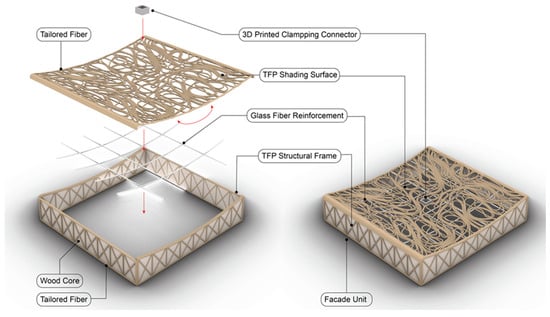

2.2.2. Bio-Composite Tailored Façades (2022)

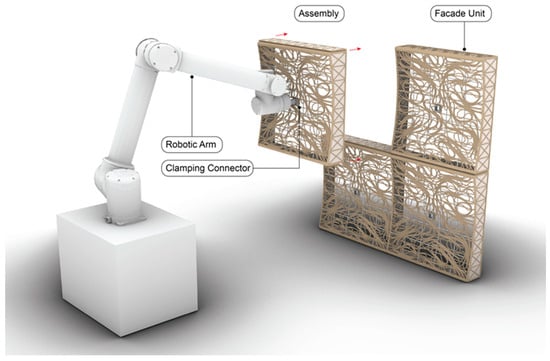

The Bio-composite Tailored Facades 2022 [19] project applied TFP-based integrative fabrication techniques to medium-scale architectural components, exploring mold-less and modular façade systems. It combined computational fiber layout for solar shading with embedded 3D-printed connectors, enabling robotic assembly and supporting sustainable, construction-efficient workflows.

One of the façade prototypes was developed through an integrative process combining structure, surface, and connection into a single panel unit. It consisted of three main parts: a structural frame and a shading-patterned surface, both fabricated using TFP, and a 3D-printed PLA connector designed for robotic assembly. These elements were consolidated into a unified, mold-less component (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Illustration of Bio-composite façade unit.

The structural frame was fabricated as a sandwich component, consisting of a wood core laminated between two tailored fiber-reinforced layers arranged in a 2D truss pattern to provide directional stiffness and structural stability. It serves as the supporting structure and is connected along all four sides of the shading surface, ensuring overall stability and secure edge attachment. The shading surface features a TFP pattern layer with flax fibers on the front, computationally defined based on solar-shading analysis, and is reinforced on the back with a glass fiber grid layer. It is fixed to the structural frame along its edges to secure its shape without the use of a mold. Additionally, a 3D-printed clamping connector was embedded into the center of the shading surface during fabrication to provide dedicated gripping points for robotic assembly. The position for embedding the connector was predefined and structurally reinforced by the surrounding TFP pattern [22,23] (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

3D-printed clamping connector integrated into the façade unit to support the robotic assembly process.

3. Results and Discussion

All case studies were carried out by the BioMat research group at the Institute of Building Structures and Structural Design (ITKE) at the University of Stuttgart between 2020 and 2024, exploring the broad application potential of TFP. Each project presents a distinct experiment with TFP as an innovative fabrication method that can operate across different architectural scales, mold-less forming strategies, and technical integration. Table 2 provides a comparative overview of how TFP was implemented across the four case studies. It outlines key differences and shared characteristics in a range of criteria.

Table 2.

Analytical comparison between the four case studies regarding scale, fabrication technique, forming strategy, computational design applied, and material choice.

3.1. Comparative Analysis

To analyze these cases systematically, five interrelated categories are considered: application scale, mold-less forming strategies, integration of digital design and fabrication techniques, material choices and reinforcement logic, and implications for sustainability. The first four categories are structured based on the comparison criteria outlined in Table 2. The fifth category builds on insights from earlier analyses to assess each case’s contribution to the goals of environmentally responsive architecture using TFP.

3.1.1. Application Scale

The selected case studies show a progression from small-scale experimental prototypes to a medium-scale architectural application. While the smaller projects mainly focus on geometric design principles and material behavior, the medium-scale project applies these explorations to modular façade components and the construction process possibilities. This transition from exploratory forms to deployable architectural components demonstrates that TFP in architecture is not limited to laboratory-scale innovation but is scalable to larger application-oriented systems.

3.1.2. Mold-Less Forming Strategies

Each case employs mold-less forming strategies, challenging the reliance on traditional formwork. FibrFoldr and FlaxPack both apply curve-folding techniques to transform flat preforms into three-dimensional geometries. In these projects, hinged edges are strategically programmed into the fiber layout using TFP to guide folding behavior. FibrFoldr uses minimal scaffolding to guide and secure the folds, which then remain embedded as part of the internal structure. FlaxPack further develops this logic through computational folding simulation and additional material treatment, enabling fully mold-less forming without any extra tooling. FlexFlax explores a different mold-less strategy by utilizing a surface-bendable TFP preform. The fiber layout is differentiated by density, creating distinct reinforcement zones and bending zones. This zoning enables controlled deformation after fabrication, as areas with reduced fiber content remain more flexible, allowing the structure to bend according to its material properties. The geometry is shaped using a reusable scaffold and then additionally reinforced with the CFW technique. Meanwhile, Bio-composite Tailored Facades adopt a modular, mold-less fabrication approach. The main shading surface maintains its shape without mold, supported by a glass fiber reinforcement layer and secured to the structural frame along its edges. These insights illustrate TFP’s adaptability in forming strategies that minimize or eliminate the need for conventional formwork.

3.1.3. Integration of Computational Design and Fabrication Techniques

Computational design tools and additional fabrication workflows are integrated into the TFP process at various levels of complexity and coordination in these cases. FibrFoldr and FlaxPack both utilize computational modeling to develop folding strategies. FibrFoldr uses digitally defined TFP paths to program specific hinged edges that guide the folding behavior, while FlaxPack employs advanced simulation and optimization tools, including folding behavior analysis and form-finding processes, to directly inform the fiber layout and enhance the foldability of the preform. FlexFlax and Bio-composite Tailored Facades expand this integration by combining TFP with other fabrication technologies, such as CFW, 3D printing, and robotic fabrication. For instance, FlexFlax pairs TFP with CFW to produce structurally reinforced geometries, and Bio-composite Tailored Facades use computational solar analysis to inform climate-adaptive TFP layouts and incorporate additive manufacturing to enable automated assembly. These examples demonstrate TFP’s versatility in bridging computational design with integrated multi-system workflows.

3.1.4. Material Selection and Reinforcement Strategies

All four cases incorporate local reinforcement strategies to optimize material performance while minimizing overall material usage and utilize nature-based materials, particularly flax fiber instead of traditional synthetic-based fiber. Some cases, such as FlaxPack and Bio-composite Tailored Facades, introduce additional materials like silicone layers or PLA-based 3D-printed elements to meet specific performance demands or enable construction connectivity. This material adaptability demonstrates TFP’s capacity to accommodate alternative materials throughout the fiber deposition process and in the functional behavior of the finished preform, all within a unified fabrication logic.

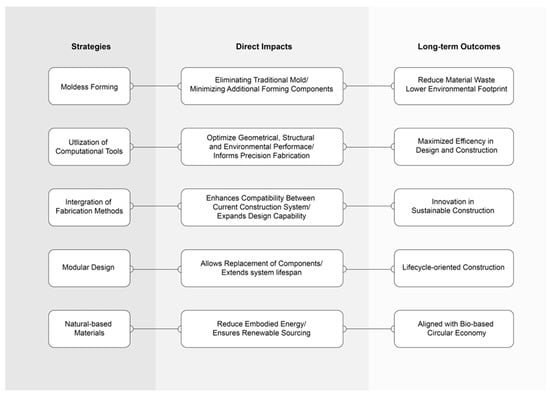

3.1.5. Implications for Sustainable Construction

This final category synthesizes the preceding analysis to articulate TFP’s contribution to sustainable construction practices within the scope of the selected case studies. In the first three small-scale cases, the TFP process is used to enable the integration of multiple functions directly into a single preform. Features like programmable fold edges, differentiated bending and reinforcement zones, and embedded winding pins to interface with other fabrication systems are strategically incorporated during fiber placement into lightweight, transformable systems capable of controlled folding and bending. This functional consolidation enables innovative forming strategies that reduce the need for additional components, minimize material waste, and eliminate reliance on conventional formwork. In the case of the medium-scale façade, life-cycle-aware design is demonstrated through modular construction, material efficiency, and streamlined assembly. The TFP pattern is informed by solar performance analysis, optimizing fiber orientation to produce functional shading while reducing unnecessary material use. Additionally, the incorporation of modular 3D-printed connectors facilitates robotic assembly and allows for future disassembly. This lightweight modular TFP façade system ensures that individual components can be accessed and replaced without dismantling the entire assembly, further extending the overall lifespan of the construction. In addition, the use of nature-based materials contributes to lowering the environmental footprint by sourcing from renewable origins. Figure 14 illustrates the mentioned TFP implementation methods and their direct impacts, ultimately contributing to long-term sustainable construction outcomes.

Figure 14.

From strategies to sustainable impacts.

Collectively, the selected cases demonstrate that TFP supports sustainable architecture by integrating renewable material use, digital precision, and design adaptability. Its capabilities allow fiber placement to be precisely tailored for both structural and environmental performance, pointing to TFP as a driver for circular, resource-conscious, and performance-oriented architectural systems.

3.2. Identified Fabrication Challenges

While the previous analyses highlight the architectural and environmental potential and impacts of the fabrication strategies applied in the case studies, their realization also introduces fabrication-related considerations. Building on the comparative analysis, this section articulates the fabrication-related constraints identified across the case studies based on analysis of the documented fabrication process and outcomes.

In FibrFoldr, folding behavior relies on deliberately reduced reinforcement along hinged edges to enable flexibility, despite adjacent rigid edges, making these zones particularly sensitive during the curve-folding process and prone to damage or over-folding. FlaxPack addresses this challenge through the selective application of elastomeric surface treatments at hinged edges to maintain compliance during folding. However, because these elastomeric layers are manually applied after the TFP process, they introduce additional fabrication issues, including potential inconsistencies in layer thickness and reduced surface uniformity. Although FlaxPack demonstrates the feasibility of fully mold-less forming, the compliant folding depends strongly on computationally driven form-finding and simulation. This introduces tolerances between simulated folding behavior and physical material response.

In FlexFlax, bending behavior is introduced through structurally informed fiber reinforcement within designated bending zones, which may reduce the sensitivity and localized damage risks associated with the hinged folding strategies and external surface treatments employed in the previous two cases. However, after bending, the geometry is secured through integration with additional fabrication techniques. This multi-stage fabrication sequence highlights the need for precise coordination between computationally differentiated fiber layouts, the bending-active scaffold, and the CFW process, as minor misalignments can affect geometric accuracy and performance. The Bio-composite Tailored Facades case indicates challenges related to dimensional tolerances and alignment across fabrication processes, particularly between TFP-fabricated surfaces, structural frames, and embedded 3DP connectors during assembly. This separation affects overall component continuity and increases tolerance sensitivity during assembly. In the context of robotic assembly, precise positioning of embedded connectors becomes critical. Similar to FlexFlax, the integration of multiple fabrication principles increases sensitivity to positional inaccuracies, which can complicate robotic gripping and reliable assembly. As the façade geometry is relatively simple in this case, bending or folding-based forming strategies as explored in the previous three cases could potentially support greater component continuity by reducing segmentation and improving geometric integration.

Additionally, all presented cases utilize natural flax fibers as a sustainable reinforcement alternative, which further introduce fabrication challenges due to material variability. Compared to synthetic fibers, flax fibers exhibit irregular diameters and variable stiffness due to their natural material characteristics, which necessitate additional calibration, adjustment, and iterative prototyping during fabrication [22]. Table 3 presents an overview of fabrication challenges across case studies.

Table 3.

Overview of fabrication challenges and potential design response across all case studies.

4. Outlook and Future Research

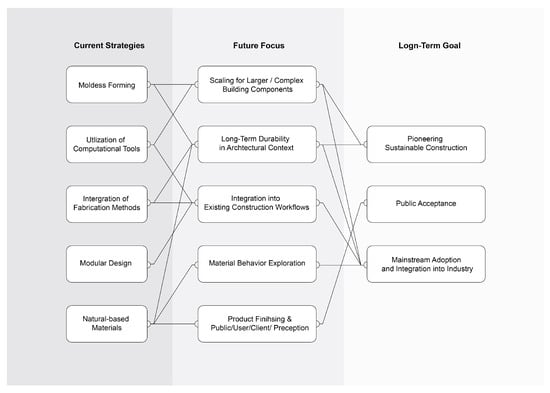

Beyond the fabrication-related constraints identified through the case studies, this section addresses broader challenges that must be resolved for the wider adoption of tailored fiber placement (TFP) in architectural construction.

One such challenge lies in the scaling of fabrication, as current TFP machinery is constrained by limited working areas, restricting the production of large or complex building components as single elements. Addressing this limitation will require further research into upscaling techniques, segmentation strategies, and modular construction approaches. At a broader system level, if this scalability challenge is not fully addressed, it also limits the advancement of TFP toward a standardized and widely adopted construction method and introduces challenges related to industrial integration, particularly under requirements for high-speed, large-volume production and established material systems [22]. This is largely due to the fact that existing TFP machinery and workflows are optimized for small- to medium-scale, high-precision components and are primarily configured for synthetic fiber composites, constraining TFP-reinforced bio-composite transfer to sustainable architectural construction requiring larger-scale elements, bio-based materials, and long-term durability.

In this context, TFP-reinforced bio-composites may initially be more readily applied to smaller-scale or modular load-bearing systems, such as infrastructural or temporary components, which can serve as an intermediate application approach before translation to larger architectural elements [7,24]. While architecture remains the primary focus of this study, future research may build on insights gained from such intermediate applications to support the broader implementation of TFP within architectural construction. Accordingly, further work should focus both on developing TFP as an independent construction method and on embedding it within existing industrial construction workflows, ensuring compatibility with standards relevant to the built environment. From a future sustainable construction perspective, research may further investigate the potential of TFP applications with thermoplastic composite systems as a direction toward material reuse and circular construction strategies that support more adaptable and resource-conscious architectural lifecycles. This direction aligns with current and ongoing investigations and contribution within the EU Horizon project REPurpose.

Another key challenge, as noted previously, concerns the durability and material behavior of TFP-based bio-composite components. While synthetic fiber composites in TFP have been tested in industrial contexts [5,25,26], the long-term performance of TFP-reinforced bio-composite elements remains less explored. Their response to environmental exposure, aging, and mechanical loading has yet to be fully characterized. Addressing these aspects will require systematic durability testing and targeted material studies.

Finally, beyond technical and industrial constraints, the acceptance of TFP-based components within architectural contexts remains an open question. Future research should explore how design-related factors, such as surface finish, texture, and material expression, influence perception among users, clients, and the public, and how these qualities can be effectively communicated through architectural design strategies and demonstration projects.

Limitation of the Work

This research is limited to an architectural design and fabrication-oriented investigation of TFP. The presented case studies are exploratory prototypes, and the analysis mainly focuses on design potential, fabrication logic, and material-driven form generation. Considerations related to detailed mechanical testing, long-term performance evaluation, or cross-industry comparison are not extended in this study, as they would require different criteria and evaluation frameworks beyond the scope of this work.

The scale of the investigated prototypes is influenced by the working area of existing TFP machinery. While modularity is indicated in the medium-scale façade case as a sustainability-oriented design strategy (Section 3.2) supporting component replacement and assembly efficiency, the study does not evaluate its effectiveness as a general solution for larger-scale building systems. While nature-based fibers are employed to investigate the sustainability potential of TFP, aspects related to long-term durability, environmental exposure, and the aging behavior of TFP-reinforced bio-composites are not examined in detail.

5. Conclusions

In response to the increasing pressure on the built environment to minimize waste, emissions, and resource consumption, this paper has examined the relationship between architecture, materials, design processes, and construction methodologies with TFP as the central fabrication strategy. By introducing TFP as an innovative design-integrated fabrication approach, the study highlights its potential to align material intelligence with digital precision in support of more sustainable architectural practices.

Through the comparative analysis of four TFP-centered case studies, this paper demonstrates a range of fabrication-driven strategies relevant to sustainable architectural construction. These include mold-less forming enabled through curve-folding and surface-bending techniques, computationally informed fiber layout design responsive to geometric and structural constraints, and the integration of TFP with complementary fabrication processes such as CFW, 3D printing, and robotic assembly. In addition, the application of modular design principles and the use of nature-based reinforcement materials support material efficiency, component adaptability, and lifecycle-oriented construction approaches, contributing to reduced embodied energy and renewable material sourcing. Together, these strategies highlight TFP’s capacity to operate as a flexible and integrative fabrication method that aligns environmental responsibility with design adaptability and technical versatility in architectural practice.

The findings of this research point toward longer-term goals of establishing TFP as a viable approach for sustainable construction, supporting its mainstream adoption and integration within the construction industry, securing broad public and professional acceptance (Figure 15). Achieving these goals will require sustained research, iterative prototyping, and interdisciplinary collaboration. With these long-term goals in mind, this paper represents an initial effort to position TFP as a tool for aligning architectural design and construction with principles of environmental responsibility and material-driven innovation.

Figure 15.

TFP adoption roadmap: from current strategies to future focus and long-term goal.

Author Contributions

C.-H.L. contributed to conceptualization; methodology; software; validation; formal analysis; investigation; visualization; writing—original draft preparation; writing—review and editing. H.D. contributed to supervision; writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is partially funded by the European Unioin’s Horizon Europe Programme through the project REPurpose (Grant Agreement No. 101057971).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research took place in BioMat@Copenhagen (Bio-Based Materials and Materials Cycles in the Building Industry Research Centre) and the related infrastructure within MakerSpace for Sustainability, Department of Sustainability and Planning, Faculty of IT and Design, Aalborg University, which provided facilities, resources, and an interdisciplinary research environment that enabled this research to take place.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dahy, H. ‘Materials as a Design Tool’ Design Philosophy Applied in Three Innovative Research Pavilions Out of Sustainable Building Materials with Controlled End-Of-Life Scenarios. Buildings 2019, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU Commission. A New Circular Economy Action Plan; EU Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hertwich, E.; Lifset, R.; Pauliuk, S.; Heeren, N. Resource Efficiency and Climate Change; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Spickenheuer, A.; Schulz, M.; Gliesche, K.; Heinrich, G. Using Tailored Fibre Placement Technology for Stress Adapted Design of Composite Structures. Plast. Rubber Compos. 2008, 37, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattheij, P.; Gliesche, K.; Feltin, D. Tailored Fiber Placement-Mechanical Properties and Applications. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 1998, 17, 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carosella, S.; Hügle, S.; Helber, F.; Middendorf, P. A Short Review on Recent Advances in Automated Fiber Placement and Filament Winding Technologies. Compos. B Eng. 2024, 287, 111843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sippach, T.; Dahy, H.; Uhlig, K.; Grisin, B.; Carosella, S.; Middendorf, P. Structural Optimization through Biomimetic-Inspired Material-Specific Application of Plant-Based Natural Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites (NFRP) for Future Sustainable Lightweight Architecture. Polymers 2020, 12, 3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spickenheuer, A.; Scheffler, C.; Bittrich, L.; Haase, R.; Weise, D.; Garray, D.; Heinrich, G. Tailored Fiber Placement in Thermoplastic Composites. Technol. Lightweight Struct. (TLS) 2018, 1, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, A.M.; Huelskamp, S.R.; Tanner, C.; Rapking, D.; Ricchi, R.D. Application of Tailored Fiber Placement to Fabricate Automotive Composite Components with Complex Geometries. Compos. Struct. 2023, 313, 116855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlig, K.; Spickenheuer, A.; Bittrich, L.; Heinrich, G. Development of a Highly Stressed Bladed Rotor Made of a CFRP Using the Tailored Fiber Placement Technology. Mech. Compos. Mater. 2013, 49, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliesche, K. Application of the Tailored Fibre Placement (TFP) Process for a Local Reinforcement on an “Open-Hole” Tension Plate from Carbon/Epoxy Laminates. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2003, 63, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahy, H.; Petrs, J.; Baszynski, P. Biocomposites from Annually Renewable Resources Displaying Vision Of Future Sustainable Architecture. In FABRICATE 2020; UCL Press: London, UK, 2020; pp. 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Building Structures and Structural Design (ITKE). BioMat Flat to Spatial Mockup 2020. Available online: https://www.itke.uni-stuttgart.de/research/built-projects/biomat-flat-to-spatial-mockup-2020/ (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Rihaczek, G.; Klammer, M.; Başnak, O.; Petrš, J.; Grisin, B.; Dahy, H.; Carosella, S.; Middendorf, P. Curved Foldable Tailored Fiber Reinforcements for Moldless Customized Bio-Composite Structures. Proof of Concept: Biomimetic NFRP Stools. Polymers 2020, 12, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saslawsky, K.; Steixner, C.; Tucker, M.; Costalonga, V.; Dahy, H. FlaxPack: Tailored Natural Fiber Reinforced (NFRP) Compliant Folding Corrugation for Reversibly Deployable Bending-Active Curved Structures. Polymers 2024, 16, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piker, D. Kangaroo Physics. Available online: https://www.food4rhino.com/en/app/kangaroo-physics (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Preisinger, C. Karamba3D. Available online: https://karamba3d.com (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Costalonga Martins, V.; Cutajar, S.; van der Hoven, C.; Baszyński, P.; Dahy, H. FlexFlax Stool: Validation of Moldless Fabrication of Complex Spatial Forms of Natural Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (NFRP) Structures through an Integrative Approach of Tailored Fiber Placement and Coreless Filament Winding Techniques. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BioMat at ITKE, U.S. Bio-Compsite Tailored Facades 2022. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rmYZ17d2itM (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Stevens, C. Industrial Applications of Natural Fibres:Structure, Properties and Technical Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 10, ISBN 9780470695081. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering, K.L.; Efendy, M.G.A.; Le, T.M. A Review of Recent Developments in Natural Fibre Composites and Their Mechanical Performance. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 83, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyridonos, E.; Costalonga, V.; Petrš, J.; Kerekes, G.; Schwieger, V.; Dahy, H. Enhancing Construction Accuracy with Biocomposites through 3D Scanning Methodology: Case Studies Applying Pultrusion, 3D Printing, and Tailored Fibre Placement. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahy, H. Materials as Design Tool: Digital Fabrication Strategies for Sustainable Architecture. Technol. Archit. Des. 2023, 7, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrš, J.; Spyridonos, E.; Grabowska, P.; Grisin, B.; Carosella, S.; Middendorf, P.; Dahy, H. Exploring Tailored Fiber Placement in Biocomposite Modular Structures. Technol. Archit. Des. 2025, 9, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koricho, E.G.; Khomenko, A.; Fristedt, T.; Haq, M. Innovative Tailored Fiber Placement Technique for Enhanced Damage Resistance in Notched Composite Laminate. Compos. Struct. 2015, 120, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, G.d.A.; Lisbôa, T.d.V.; Elschner, C.; Spickenheuer, A. Experimental Global Warming Potential-Weighted Specific Stiffness Comparison among Different Natural and Synthetic Fibers in a Composite Component Manufactured by Tailored Fiber Placement. Polymers 2024, 16, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.