Exploring Organizational and Individual Determinants of Construction Workers’ Safety Behavior: An Interpretable Machine Learning Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data

2.1. Variable Selection

2.2. Scale Design

2.3. Data Collection

3. Methodology

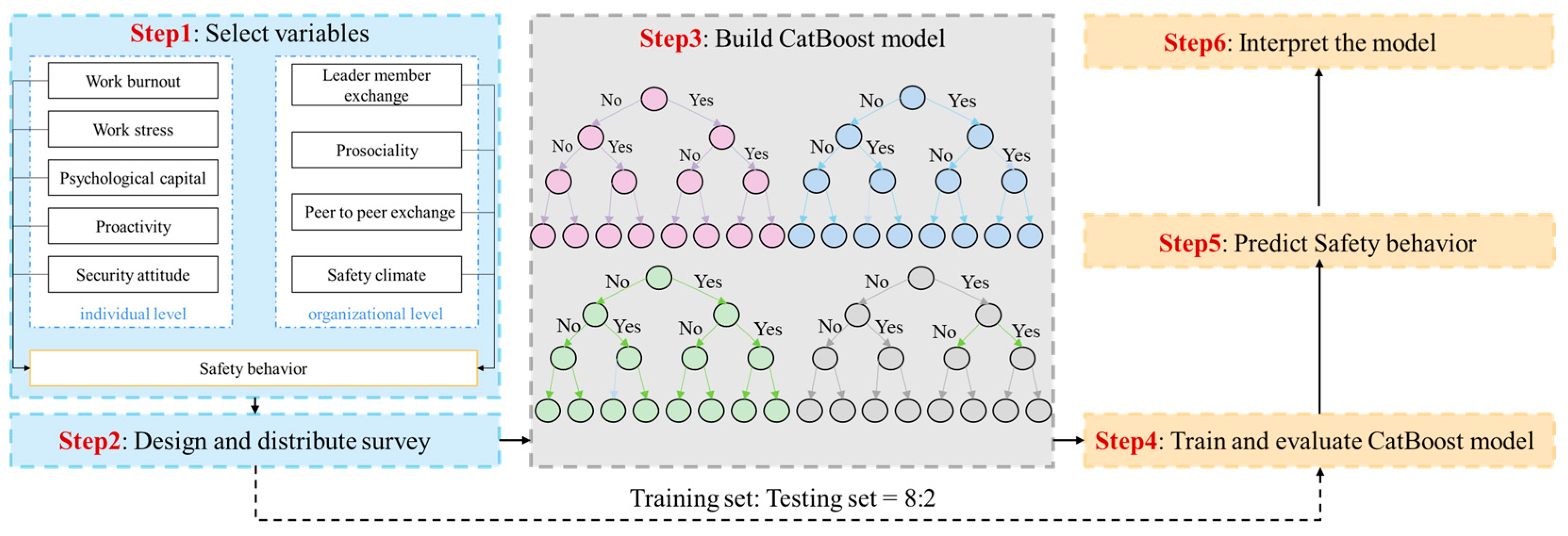

3.1. Analytical Procedure

3.2. CatBoost Algorithm

3.3. SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP)

3.4. Model Optimization and Parameter Selection

3.5. Model Evaluation Indicators

4. Results

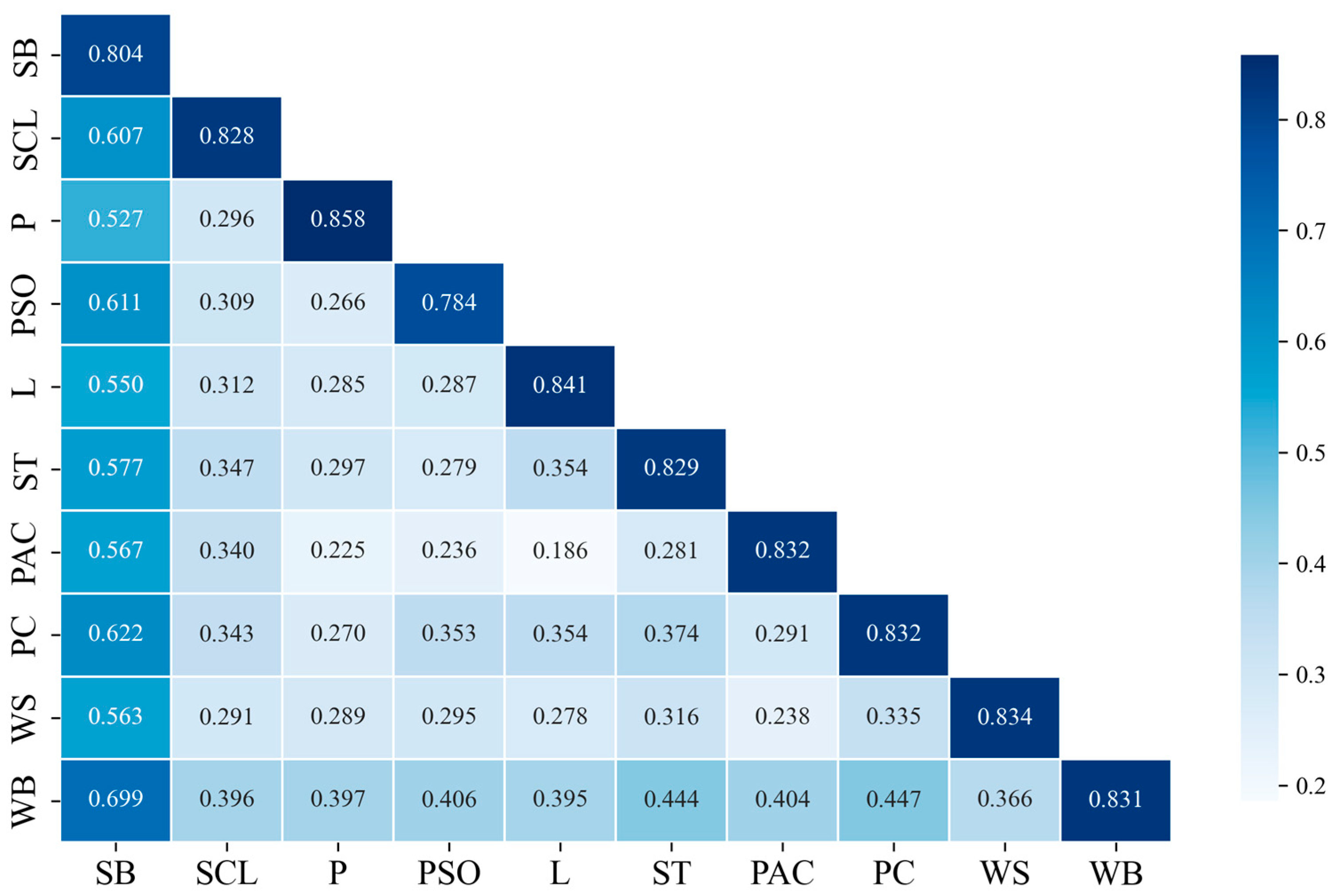

4.1. Data Description

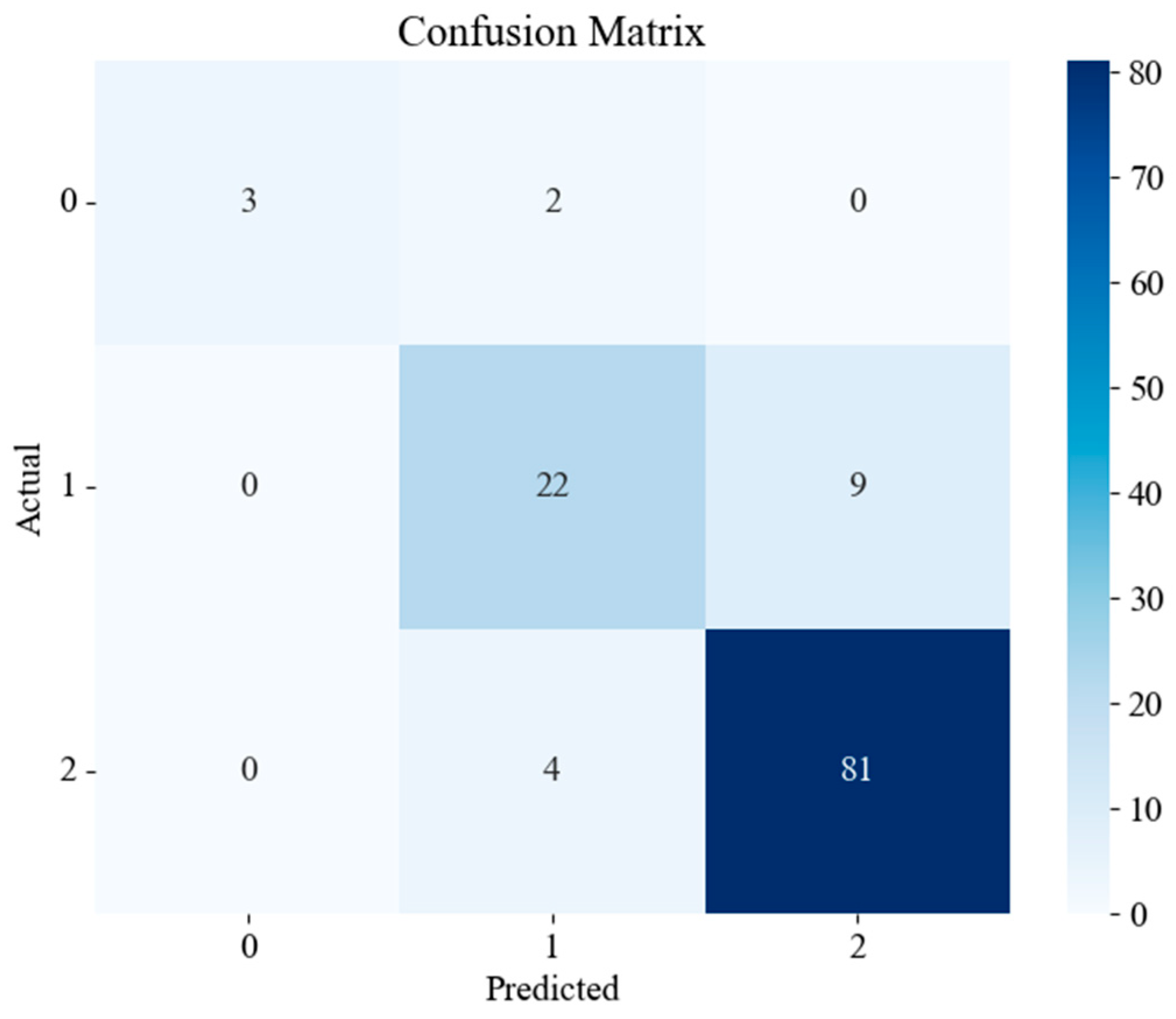

4.2. Model Evaluation

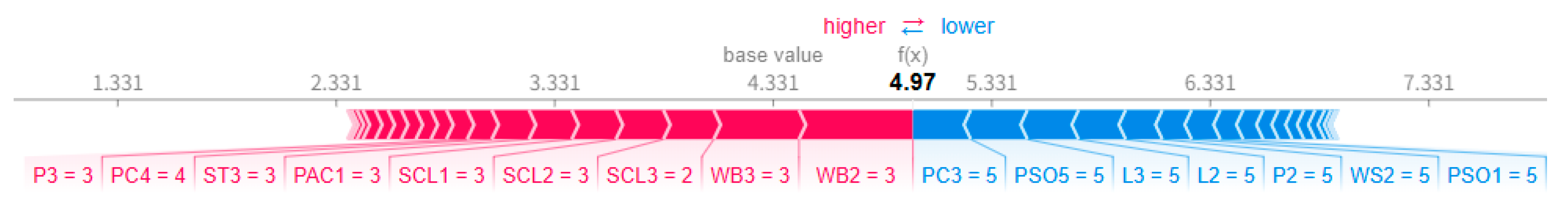

4.3. Model Interpretation

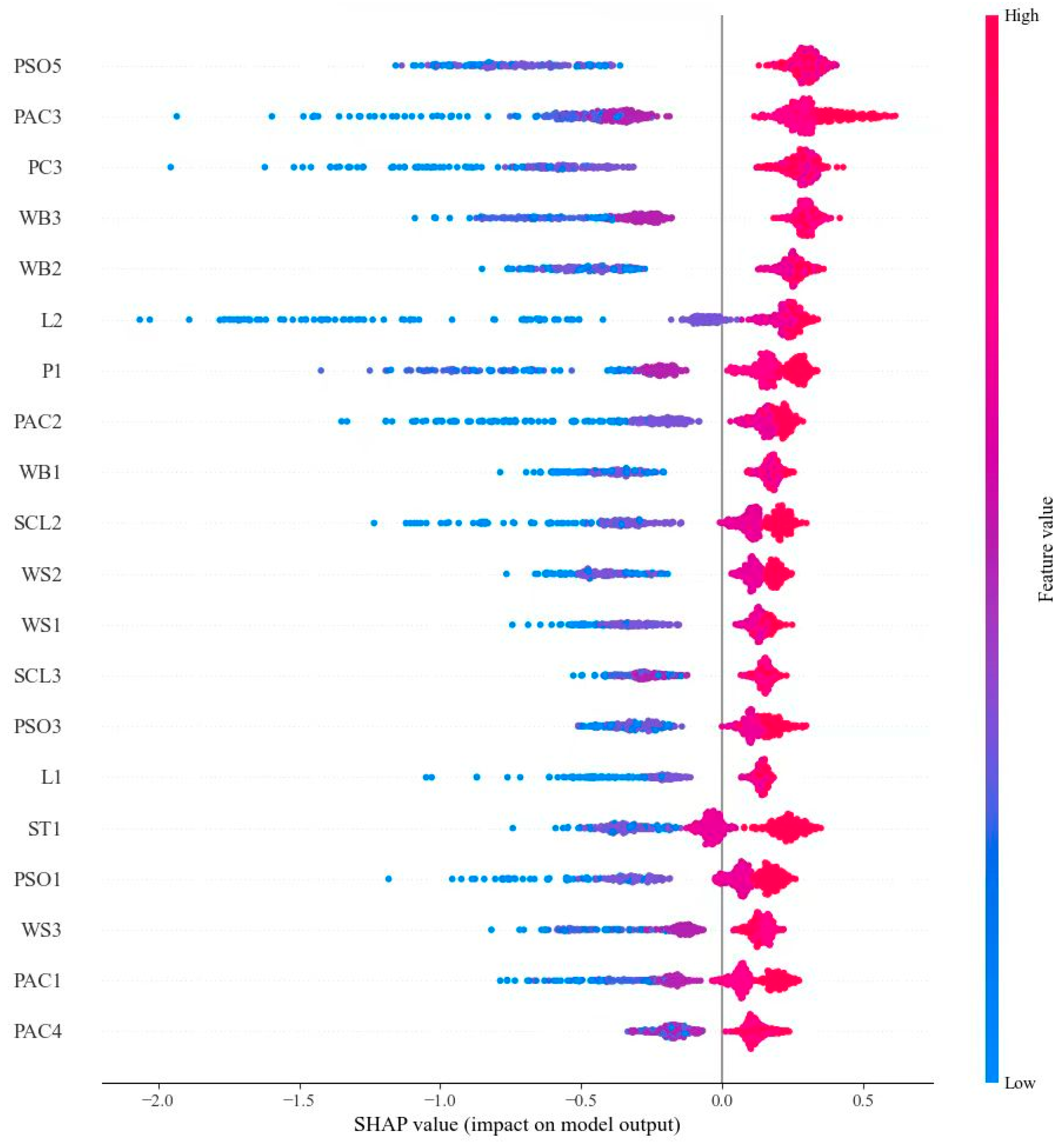

4.3.1. Univariate Analysis

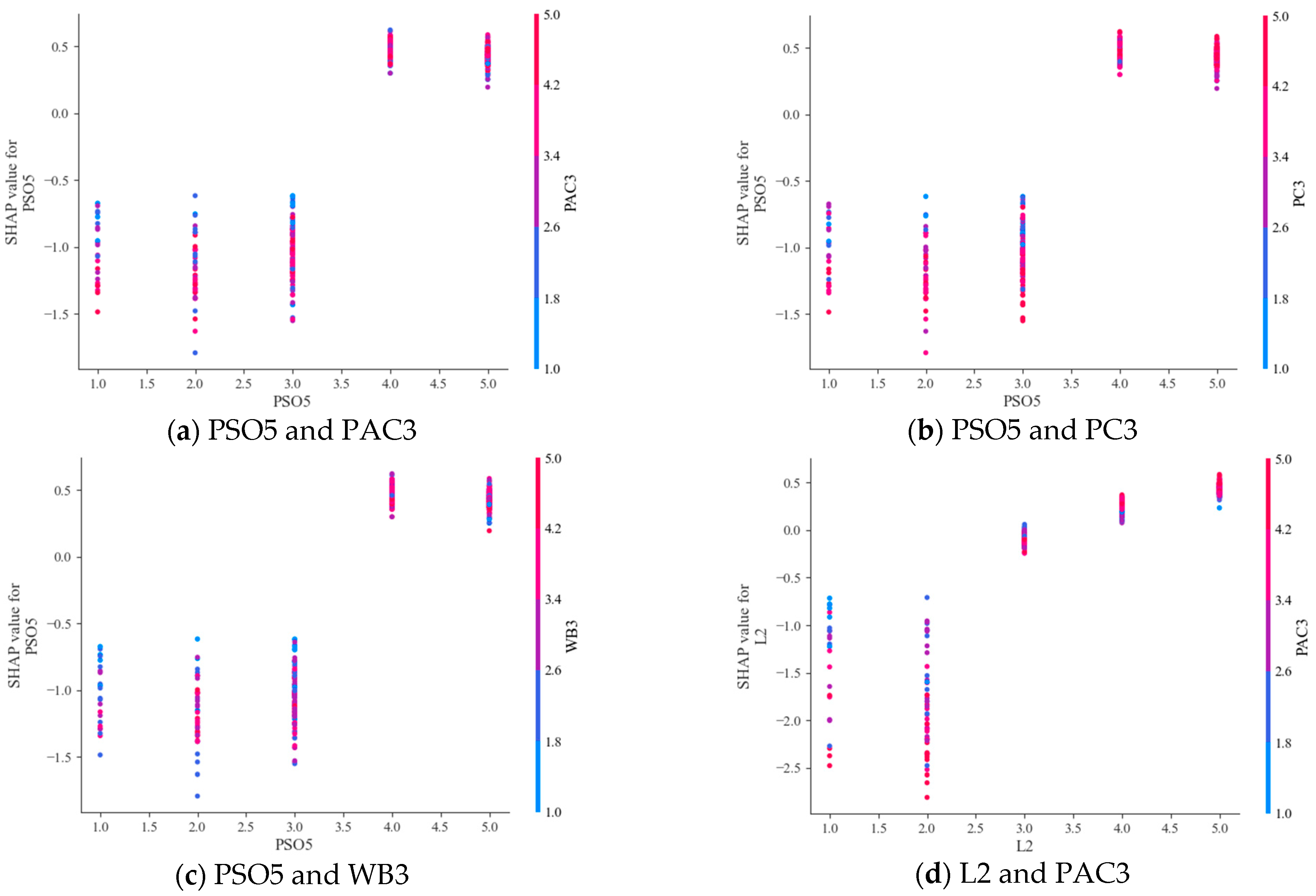

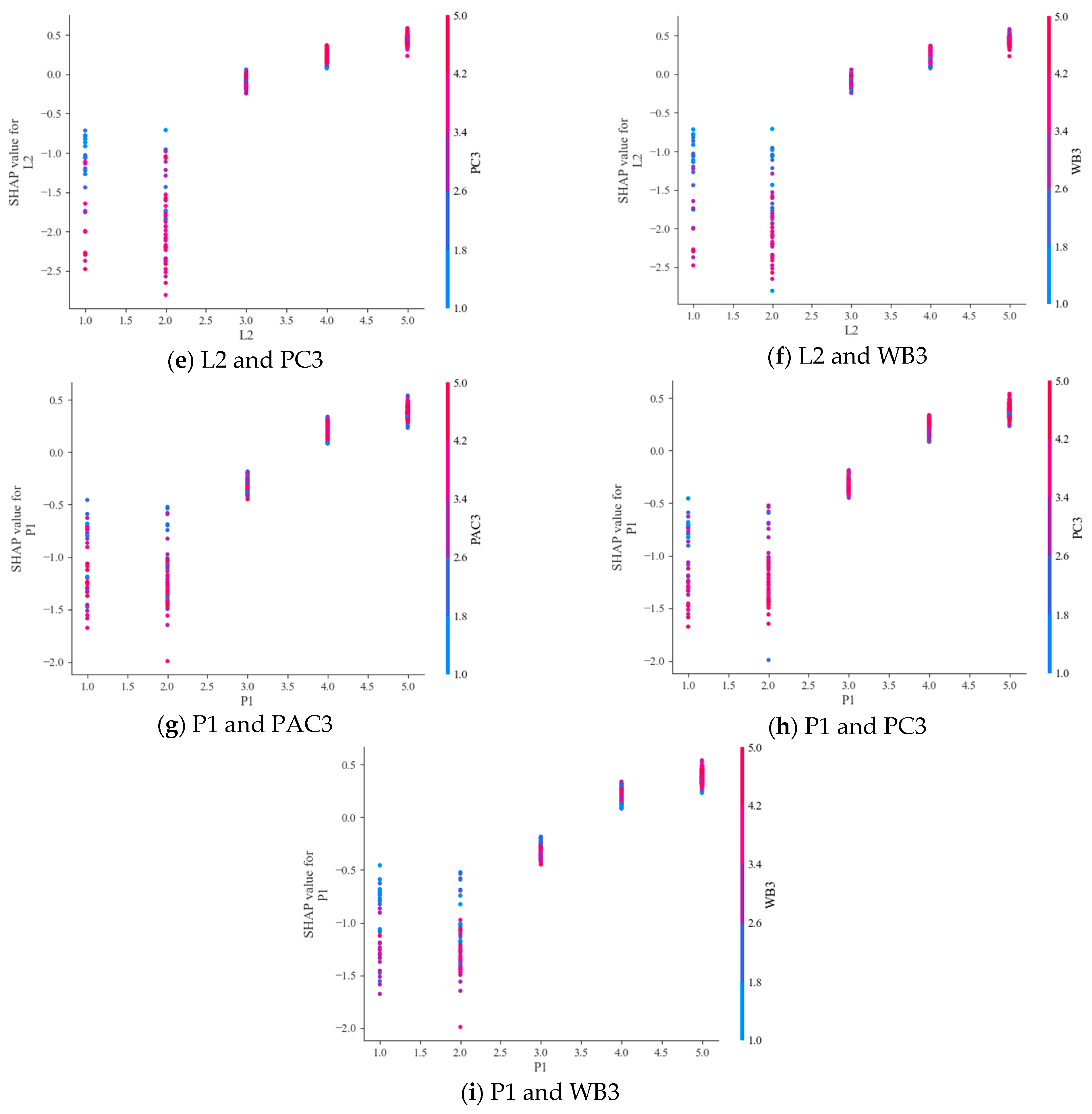

4.3.2. Interaction Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Advantages

5.2. Management Advantages

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Dong, X.; Largay, J.A.; Wang, X.; Windau, J. Fatalities in the construction industry: Findings from a revision of the BLS Occupational Injury and Illness Classification System. Mon. Lab. Rev. 2014, 137, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Wu, H. Development of a Safety Culture Interaction (SCI) model for construction projects. Saf. Sci. 2013, 57, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ye, G.; Xiang, Q.; Kim, M.; Liu, Q.; Yue, H. Insights into the mechanism of construction workers’ unsafe behaviors from an individual perspective. Saf. Sci. 2021, 133, 105004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newaz, M.T.; Davis, P.; Jefferies, M.; Pillay, M. Examining the Psychological Contract as Mediator between the Safety Behavior of Supervisors and Workers on Construction Sites. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04019094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Xu, K. Analysis of the Characteristics of Fatal Accidents in the Construction Industry in China Based on Statistical Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xiang, P.; Zhang, R.; Chen, D.; Ren, Y. Mediating Effect of Risk Propensity between Personality Traits and Unsafe Behavioral Intention of Construction Workers. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwagbala, D.C.; Park, J.Y. A Study of the Foremen’s Influence on the Safety Behavior of Construction Workers Based on Cognitive Theory. Buildings 2023, 13, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; He, Y.; Li, Z. Study on Influencing Factors of Construction Workers’ Unsafe Behavior Based on Text Mining. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 886390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, G.; Lv, L.; Wang, S.; Miao, X.; Fang, Y.; Liu, Q. Formation Mechanism and Dynamic Evolution Laws About Unsafe Behavior of New Generation of Construction Workers Based on China’s Construction Industry: Application of Grounded Theory and System Dynamics. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 888060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Chan, A.H.S. Exerting Explanatory Accounts of Safety Behavior of Older Construction Workers within the Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suraji, A.; Duff, A.R.; Peckitt, S.J. Development of Causal Model of Construction Accident Causation. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2001, 127, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Zhu, H.; Cai, Y.; Pan, Y. Group cognitive characteristics of construction Workers’ unsafe behaviors from personalized management. Saf. Sci. 2024, 175, 106492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Huang, J.; Liu, J.; Jia, L. A Study of Factors Influencing Construction Workers’ Intention to Share Safety Knowledge. Buildings 2024, 14, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ye, G.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y. Linking construction noise to worker safety behavior: The role of negative emotion and regulatory focus. Saf. Sci. 2023, 162, 106093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Guo, H.; Gao, P.; Wang, Y.; Fang, Y. Impact of owners’ safety management behavior on construction workers’ unsafe behavior. Saf. Sci. 2023, 158, 105944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vithanage, S.C.; Sing, M.C.P.; Davis, P.; Newaz, M.T. Assessing the Off-Site Manufacturing Workers’ Influence on Safety Performance: A Bayesian Network Approach. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 04021185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhao, T.; Zhou, W.; Tang, J. Safety risk factors of metro tunnel construction in China: An integrated study with EFA and SEM. Saf. Sci. 2018, 105, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadfam, I.; Ghasemi, F.; Kalatpour, O.; Moghimbeigi, A. Constructing a Bayesian network model for improving safety behavior of employees at workplaces. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 58, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Guo, H.; Wu, Y.; Luo, Z. Causal inference of construction safety management measures towards workers’ safety behaviors: A multidimensional perspective. Saf. Sci. 2024, 172, 106432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Lee, H.S.; Park, M.; Moon, M.; Han, S. A system dynamics approach for modeling construction workers’ safety attitudes and behaviors. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014, 68, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, N.; Jiang, Z.; Fang, D.; Anumba, C.J. An agent-based modeling approach for understanding the effect of worker-management interactions on construction workers’ safety-related behaviors. Autom. Constr. 2019, 97, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayhan, B.U.; Tokdemir, O.B. Accident Analysis for Construction Safety Using Latent Class Clustering and Artificial Neural Networks. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04019114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Ni, P.; Zhu, H.; Cai, Y.; Pan, Y. Artificial Cognition to Predict and Explain the Potential Unsafe Behaviors of Con-struction Workers. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 04024074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farashaei, D.; Honarbakhsh, A.; Movahedifar, S.M.; Shakeri, E. Individual flexibility and workplace conflict: Cloud-based data collection and fusion of neural networks. Wirel. Netw. 2022, 30, 4093–4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashifi, M.T. Investigating two-wheelers risk factors for severe crashes using an interpretable machine learning approach and SHAP analysis. Iatss Res. 2023, 47, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Yao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Y.; Bi, C. Applying an interpretable machine learning framework to the traffic safety order analysis of expressway exits based on aggregate driving behavior data. Physica A 2022, 597, 127277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, M.; Tian, Z.; Bashir, A.K.; Du, X.; Guizani, M. IoT malicious traffic identification using wrapper-based feature selection mechanisms. Comput. Secur. 2020, 94, 101863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Xie, Y.; Wu, L.; Jiang, L. Quantifying and comparing the effects of key risk factors on various types of roadway segment crashes with LightGBM and SHAP. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 159, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chehreh Chelgani, S.; Nasiri, H.; Tohry, A.; Heidari, H.R. Modeling industrial hydrocyclone operational variables by SHAP-CatBoost—A “conscious lab” approach. Powder Technol. 2023, 420, 118416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Qiu, Y.; Armaghani, D.J.; Zhang, W.; Li, C.; Zhu, S.; Tarinejad, R. Predicting TBM penetration rate in hard rock condition: A comparative study among six XGB-based metaheuristic techniques. Geosci. Front. 2021, 12, 101091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM Sigkdd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, S.; Sahin, E.K. Predicting occurrence of liquefaction-induced lateral spreading using gradient boosting algorithms integrated with particle swarm optimization: PSO-XGBoost, PSO-LightGBM, and PSO-CatBoost. Acta Geotech. 2023, 18, 3403–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.Y. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Chang, X.; Hu, S.; Yin, H.; Wu, J. Combining travel behavior in metro passenger flow prediction: A smart explainable Stacking-Catboost algorithm. Inform. Process. Manag. 2024, 61, 103733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; McCabe, B.; Jia, G. Effect of leader-member exchange on construction worker safety behavior: Safety climate and psychological capital as the mediators. Saf. Sci. 2021, 142, 105401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Chan, A.H.S.; Lui, L.K.H.; Fang, Y. Effects of individual and organizational factors on safety consciousness and safety citizenship behavior of construction workers: A comparative study between Hong Kong and Mainland China. Saf. Sci. 2021, 135, 105116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.C.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, J.J.; Jee, N.Y. Analyzing safety behaviors of temporary construction workers using structural equation modeling. Saf. Sci. 2015, 77, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Jia, G.; McCabe, B.; Chen, Y.; Sun, J. Impact of psychological capital on construction worker safety behavior: Communication competence as a mediator. J. Saf. Res. 2019, 71, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Ye, G.; Shen, L. Unveiling the mechanism of construction workers’ unsafe behaviors from an occupational stress perspective: A qualitative and quantitative examination of a stress–cognition–safety model. Saf. Sci. 2022, 145, 105486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saracino, A.; Curcuruto, M.; Antonioni, G.; Mariani, M.G.; Guglielmi, D.; Spadoni, G. Proactivity-and-consequence-based safety incentive (PCBSI) developed with a fuzzy approach to reduce occupational accidents. Saf. Sci. 2015, 79, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Mei, Q.; Liu, S.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, J. Demographic differences in safety proactivity behaviors and safety management in Chinese small–scale enterprises. Saf. Sci. 2019, 120, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderfeldt, M.; Söderfeldt, B.; Warg, L.E.; Ohlson, C.G. The factor structure of the Maslach Burnout Inventory in two Swedish human service organizations. Scand. J. Psychol. 1996, 37, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawada, T.; Otsuka, T. Relationship between job stress, occupational position and job satisfaction using a brief job stress questionnaire (BJSQ). Work 2011, 40, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B.; Norman, S.M. Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S.E.; Grant, J.M.; Kraimer, M.L. Proactive personality and career success. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugas, C.S.; Silva, S.A.; Meliá, J.L. Another look at safety climate and safety behavior: Deepening the cognitive and social mediator mechanisms. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2012, 45, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, Y.M.; Ubeynarayana, C.U.; Wong, K.L.X.; Guo, B.H.W. Factors influencing unsafe behaviors: A supervised learning approach. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 118, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Maslyn, J.M. Multidimensionafity of Leader-Member Exchange: An Empirical Assessment through Scale Development. J. Manag. 1998, 24, 43–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlo, G.; Randall, B.A. The Development of a Measure of Prosocial Behaviors for Late Adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2002, 31, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubichka, M.M. The Influence of Perceived Same-Status Nurse-To-Nurse Coworker Exchange Relationships, Quality of Care Provided, Overall Nurse Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment on Intent to Stay and Job Search Behavior of Nurses in the Acute Care Nurse Work Environment. Ph.D. thesis, The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Córcoles, M.; Gracia, F.; Tomás, I.; Peiró, J.M. Leadership and employees’ perceived safety behaviours in a nuclear power plant: A structural equation model. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 1118–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.A. A study of the lagged relationships among safety climate, safety motivation, safety behavior, and accidents at the individual and group levels. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehreh Chelgani, S.; Homafar, A.; Nasiri, H.; Rezaei Laksar, M. CatBoost-SHAP for modeling industrial operational flotation variables—A “conscious lab” approach. Miner. Eng. 2024, 213, 108754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeur, S.B.; Ballouk, H.; Mefteh-Wali, S.; Omri, A. Forecasting the macrolevel determinants of entrepreneurial opportunities using artificial intelligence models. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 175, 121353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeur, S.B.; Gharib, C.; Mefteh-Wali, S.; Arfi, W.B. CatBoost model and artificial intelligence techniques for corporate failure prediction. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 166, 120658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imani, M.; Arabnia, H.R. Hyperparameter Optimization and Combined Data Sampling Techniques in Machine Learning for Customer Churn Prediction: A Comparative Analysis. Technologies 2023, 11, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstra, J.; Yamins, D.; Cox, D. Making a science of model search: Hyperparameter optimization in hundreds of dimensions for vision architectures. Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. 2013, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syarif, I.; Prugel-Bennett, A.; Wills, G. SVM parameter optimization using grid search and genetic algorithm to improve classification performance. TELKOMNIKA (Telecommun. Comput. Electron. Control) 2016, 14, 1502–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liashchynskyi, P.B.; Liashchynskyi, P. Grid Search, Random Search, Genetic Algorithm: A Big Comparison for NAS. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.06059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstra, J.; Bardenet, R.; Bengio, Y.; Kégl, B. Algorithms for hyper-parameter optimization. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2011, 24. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2011/hash/86e8f7ab32cfd12577bc2619bc635690-Abstract.html (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Dewancker, I.; McCourt, M.; Clark, S. Bayesian optimization for machine learning: A practical guidebook. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1612.04858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y. The Influence of Social Support on the Prosocial Behavior of College Students: The Mediating Effect based on Interpersonal Trust. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2017, 10, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramarajan, L.; Berger, I.E.; Greenspan, I. Multiple Identity Configurations: The Benefits of Focused Enhancement for Prosocial Behavior. Organ. Sci. 2017, 28, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, A.F.; Chen, C.C.; Xin, K.R. Justice Climates and Management Team Effectiveness: The Central Role of Group Harmony. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2017, 13, 821–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.M.-H. Gifts, Favors, and Banquets: The Art of Social Relationships in China; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.Y.C.; Owens, B.P.; Tesluk, P.E. Initiating and utilizing shared leadership in teams: The role of leader humility, team proactive personality, and team performance capability. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1705–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, K.; Ling, F.; Feng, Z.; Wang, K.; Guo, L. Psychological predictors of mobile phone use while crossing the street among college students: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2017, 18, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammad, H.; Yaman, S.K.; Hassan, F.; Ismail, Z. Determining the Technical Competencies of Construction Managers in the Malaysia’s Construction Industry. MATEC Web Conf. 2016, 47, 04021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Pons, D.; Pearse, J. Why Do Workers Take Safety Risks?—A Conceptual Model for the Motivation Underpinning Perverse Agency. Safety 2018, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhai, H.; Chan, A.H.S. Development of Scales to Measure and Analyse the Relationship of Safety Consciousness and Safety Citizenship Behaviour of Construction Workers: An Empirical Study in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasir, S.; Nasir, N.; Khan, S.; Khan, W.; Akyürek, S.S. Exclusion or insult at the workplace: Responses to ostracism through employee’s efficacy and relational needs with psychological capital. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2023, 37, 659–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinchero, E.; Farr-Wharton, B.; Brunetto, Y. A social exchange perspective for achieving safety culture in healthcare organizations. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2019, 32, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronkhorst, B.; Tummers, L.; Steijn, B. Improving safety climate and behavior through a multifaceted intervention: Results from a field experiment. Saf. Sci. 2018, 103, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMontagne, A.D.; Martin, A.; Page, K.M.; Reavley, N.J.; Noblet, A.J.; Milner, A.J.; Keegel, T.; Smith, P.M. Workplace mental health: Developing an integrated intervention approach. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference | SCL | L | P | PSO | WB | WS | PC | ST | PAC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [37] | ** | - | - | - | * | * | - | - | - |

| [38] | - | - | - | - | - | - | * | - | - |

| [36] | ** | ** | ** | ** | - | ** | - | - | ** |

| [35] | ** | ** | - | - | - | - | *** | - | - |

| [39] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | *** | - |

| Variable | No. | Item | Reference | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work burnout | WB1 | I often feel exhausted as a result of construction work. | [42] | 0.776 |

| WB2 | Since beginning this job, my interest in the work has noticeably declined. | |||

| WB3 | I believe I am competent in performing construction tasks. | |||

| Work stress | WS1 | Frequent overtime leaves me with insufficient rest. | [43] | 0.781 |

| WS2 | I am unable to work at a pace that feels comfortable to me. | |||

| WS3 | Opportunities for training are regularly available. | |||

| Psychological capital | PC1 | I was able to collaborate with other construction firms to resolve issues. | [44] | 0.851 |

| PC2 | I am generally able to overcome difficulties encountered at work. | |||

| PC3 | When facing uncertainty at work, I tend to expect favorable outcomes. | |||

| PC4 | I usually recover quickly from setbacks and continue with my work. | |||

| Proactivity | PAC1 | I am skilled at reframing problems as opportunities for improvement. | [45] | 0.851 |

| PAC2 | When challenges arise in construction, I address them directly. | |||

| PAC3 | I consistently seek more effective ways of accomplishing tasks. | |||

| PAC4 | If I am confident in an idea, I pursue it despite obstacles. | |||

| Security attitude | ST1 | I regard construction safety as the responsibility of the company and its leaders, rather than my personal duty. | [46,47] | 0.773 |

| ST2 | At work, I make a conscious effort to comply with safety regulations. | |||

| ST3 | During peak workloads, I sometimes view other tasks as taking precedence over safety. | |||

| Leader member exchange | L1 | I maintain a positive working relationship with my leader. | [48] | 0.793 |

| L2 | I believe my leader would defend me if I were criticized or confronted by others. | |||

| L3 | I am willing to put forth my best effort in support of my supervisor’s leadership. | |||

| Prosociality | PSO1 | I can help people better when there are people around to pay attention. | [49] | 0.874 |

| PSO2 | I think that helping others without them knowing is the best type of situation. | |||

| PSO3 | I tend to help people who are in a real crisis or need. | |||

| PSO4 | I am most responsive to assisting others in emotionally charged situations. | |||

| PSO5 | I readily provide help whenever others request it. | |||

| PSO6 | I offer assistance without expecting anything in return. | |||

| Peer-to-peer exchange | P1 | My colleagues collaborate and support one another on projects. | [50] | 0.820 |

| P2 | Colleagues are generally open to sharing methods and experiences. | |||

| P3 | I maintain positive and cooperative relationships with colleagues. | |||

| Safety climate | SCL1 | Management places strong emphasis on monitoring rule compliance. | [51] | 0.845 |

| SCL2 | In the event of an accident, management responds appropriately at the outset. | |||

| SCL3 | Substantial resources are invested in providing workers with safety training. | |||

| SCL4 | I currently work within a safe and supportive environment. | |||

| Safety behavior | SB1 | I consistently adhere to established work procedures. | [52] | 0.818 |

| SB2 | I make deliberate efforts to uphold the highest safety standards in my work. | |||

| SB3 | I actively propose suggestions aimed at improving construction safety. | |||

| SB4 | I will take the initiative to correct the wrong actions or ideas of my colleagues. |

| Categories | Classification | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 311 | 51.7% |

| Female | 290 | 48.3% | |

| Age | ≤30 | 172 | 28.6% |

| 31–40 | 143 | 23.8% | |

| 41–50 | 122 | 20.3% | |

| 51–60 | 92 | 15.3% | |

| 60 above | 72 | 12% | |

| Education | Middle school and below | 128 | 21.3% |

| High school and vocational school graduate | 136 | 22.6% | |

| Associate degree | 191 | 31.8% | |

| University and above | 146 | 24.3% | |

| Years of working | Below 5 | 172 | 28.6% |

| 6–10 | 79 | 13.1% | |

| 11–15 | 64 | 10.7% | |

| 16–20 | 64 | 10.7% | |

| 20 above | 222 | 36.9% | |

| Working hours | Below 8 | 158 | 26.3% |

| 8–10 | 305 | 50.7% | |

| 10 above | 138 | 23% |

| Variables | Items | Factor Loading | AVE | CR | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WB | WB1 | 0.833 | 0.691 | 0.777 | 0.776 |

| WB2 | 0.829 | ||||

| WB3 | 0.833 | ||||

| WS | WS1 | 0.833 | 0.696 | 0.782 | 0.781 |

| WS2 | 0.836 | ||||

| WS3 | 0.833 | ||||

| PC | PC1 | 0.859 | 0.692 | 0.855 | 0.851 |

| PC2 | 0.804 | ||||

| PC3 | 0.819 | ||||

| PC4 | 0.844 | ||||

| PAC | PAC1 | 0.803 | 0.692 | 0.854 | 0.851 |

| PAC2 | 0.852 | ||||

| PAC3 | 0.843 | ||||

| PAC4 | 0.828 | ||||

| ST | ST1 | 0.834 | 0.688 | 0.773 | 0.773 |

| ST2 | 0.823 | ||||

| ST3 | 0.830 | ||||

| L | L1 | 0.837 | 0.707 | 0.795 | 0.793 |

| L2 | 0.854 | ||||

| L3 | 0.832 | ||||

| PSO | PSO1 | 0.804 | 0.614 | 0.875 | 0.874 |

| PSO2 | 0.784 | ||||

| PSO3 | 0.789 | ||||

| PSO4 | 0.771 | ||||

| PSO5 | 0.781 | ||||

| PSO6 | 0.772 | ||||

| P | P1 | 0.860 | 0.735 | 0.821 | 0.820 |

| P2 | 0.865 | ||||

| P3 | 0.848 | ||||

| SCL | SCL1 | 0.851 | 0.685 | 0.848 | 0.845 |

| SCL2 | 0.831 | ||||

| SCL3 | 0.802 | ||||

| SCL4 | 0.825 | ||||

| SB | SB1 | 0.801 | 0.647 | 0.819 | 0.818 |

| SB2 | 0.791 | ||||

| SB3 | 0.827 | ||||

| SB4 | 0.799 |

| Parameter | Search Range | Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | depth | (4, 10) | 5 |

| 2 | learning_rate | (0.01, 0.3) | 0.132 |

| 3 | bagging_temperature | (0, 1) | 0.813 |

| 4 | l2_leaf_reg | (1, 10) | 2 |

| Models | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.73 | 0.79 |

| XGBoost | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.82 |

| CatBoost | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.79 | 0.84 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tang, T.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, M.; Guo, Y.; Lin, X.; Li, J. Exploring Organizational and Individual Determinants of Construction Workers’ Safety Behavior: An Interpretable Machine Learning Approach. Buildings 2026, 16, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010191

Tang T, Liu Z, Yuan M, Guo Y, Lin X, Li J. Exploring Organizational and Individual Determinants of Construction Workers’ Safety Behavior: An Interpretable Machine Learning Approach. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010191

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Tianpei, Zhaopeng Liu, Meining Yuan, Yuntao Guo, Xinrong Lin, and Jiajian Li. 2026. "Exploring Organizational and Individual Determinants of Construction Workers’ Safety Behavior: An Interpretable Machine Learning Approach" Buildings 16, no. 1: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010191

APA StyleTang, T., Liu, Z., Yuan, M., Guo, Y., Lin, X., & Li, J. (2026). Exploring Organizational and Individual Determinants of Construction Workers’ Safety Behavior: An Interpretable Machine Learning Approach. Buildings, 16(1), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010191