Intelligent Prediction of Subway Tunnel Settlement: A Novel Approach Using a Hybrid HO-GPR Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

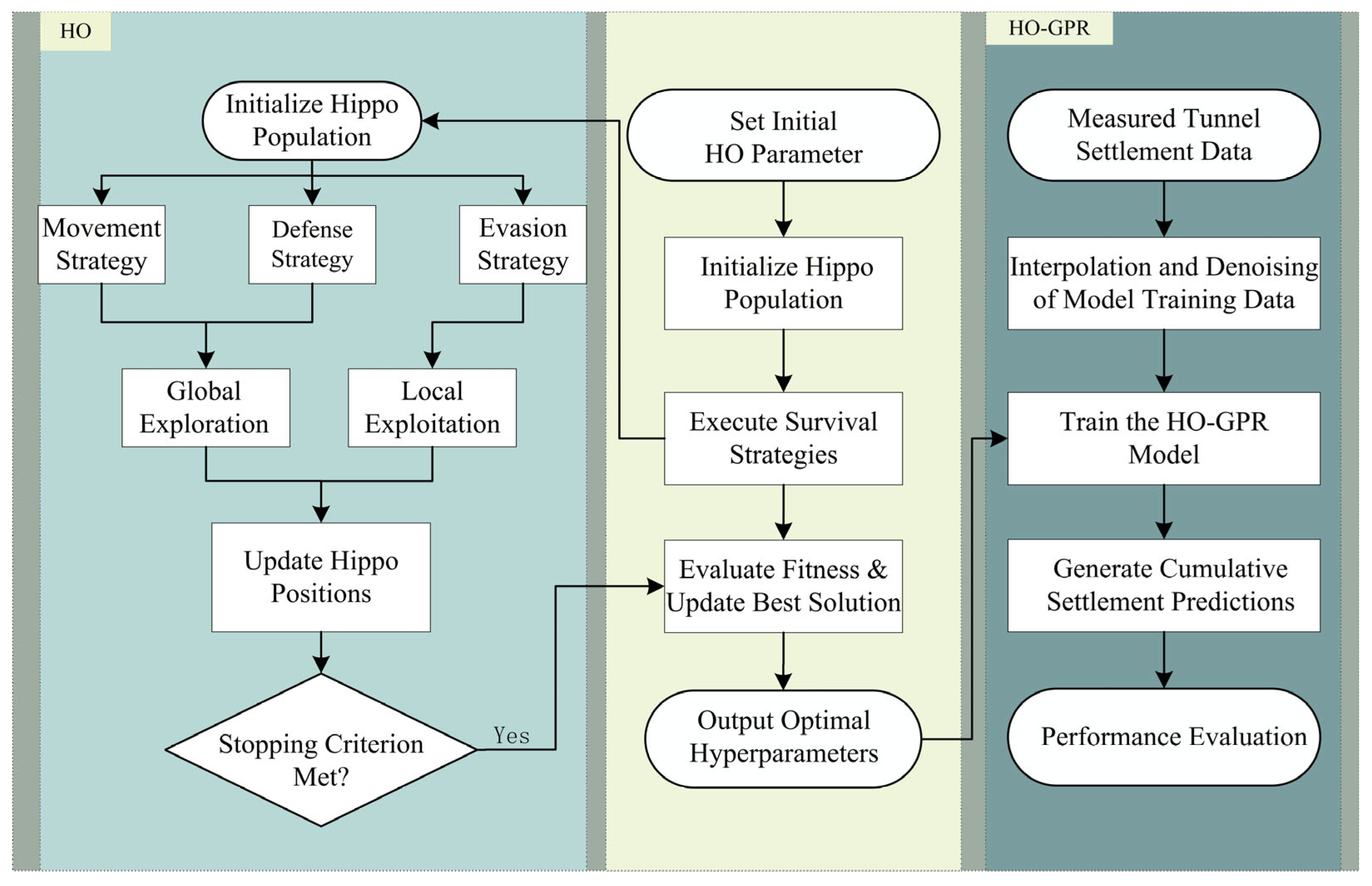

2. An HO-GPR Model for Deformation Prediction

2.1. Hippopotamus Optimization Algorithm

2.1.1. Movement Strategy

2.1.2. Defense Strategy

2.1.3. Evasion Strategy

2.2. Gaussian Process Regression

2.2.1. Principle of GPR Prediction

2.2.2. GPR Model Training

2.3. Construction of the HO-GPR Model

2.4. Evaluation Metrics

3. Case Study and Validation

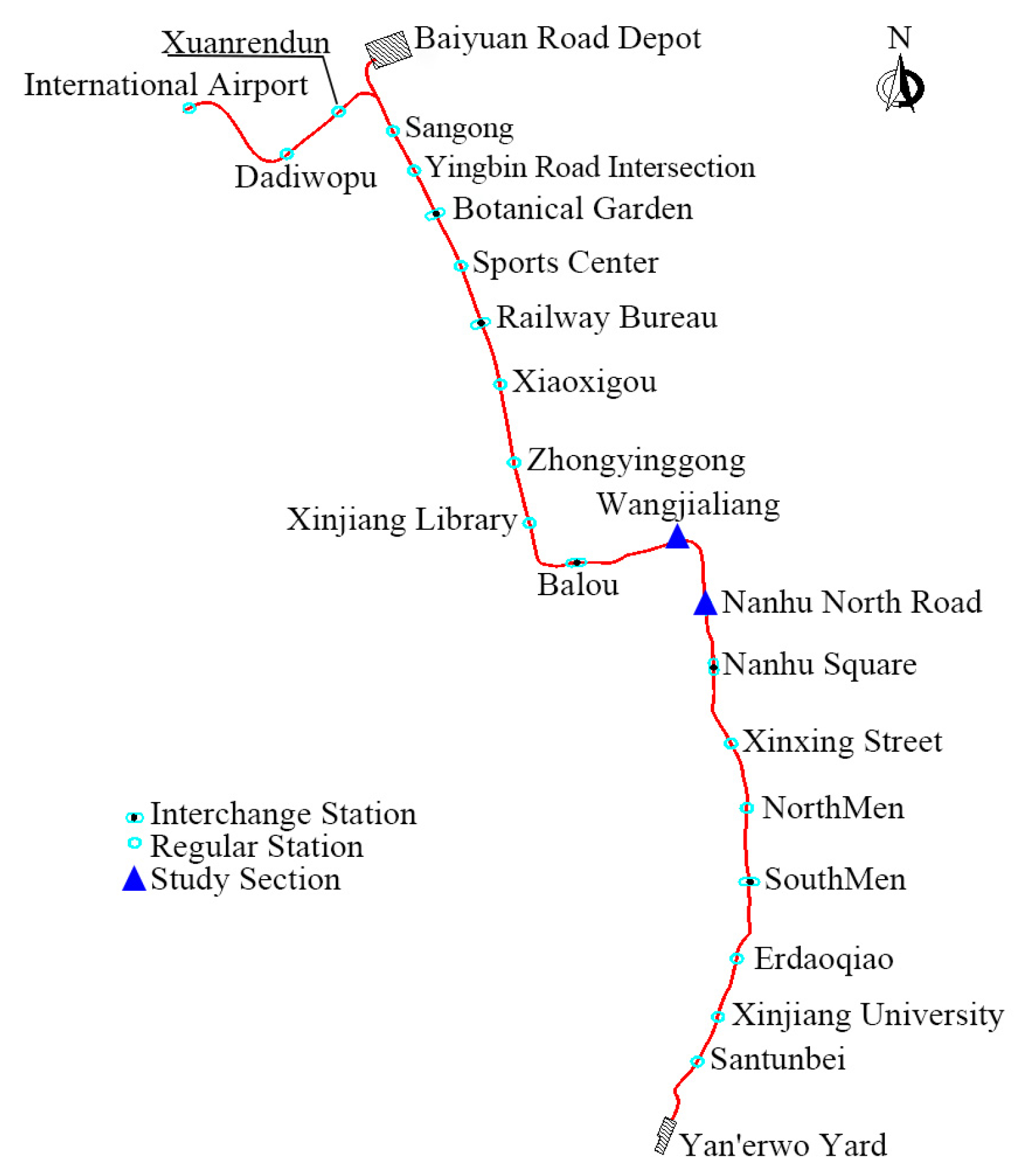

3.1. Project Overview

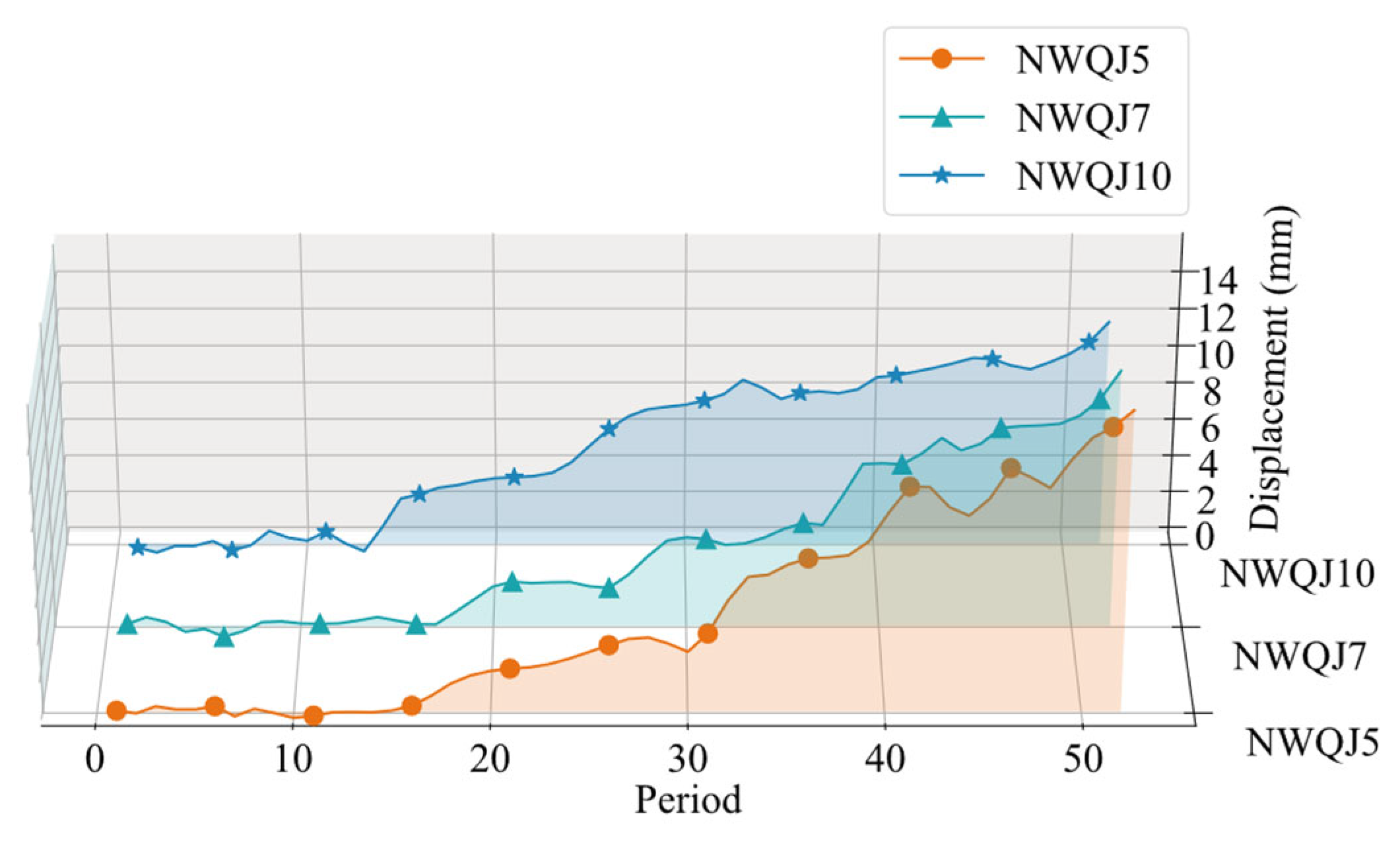

3.2. Deformation Monitoring Data

3.3. Model Construction and Result Analysis

3.3.1. Data Pre-Processing

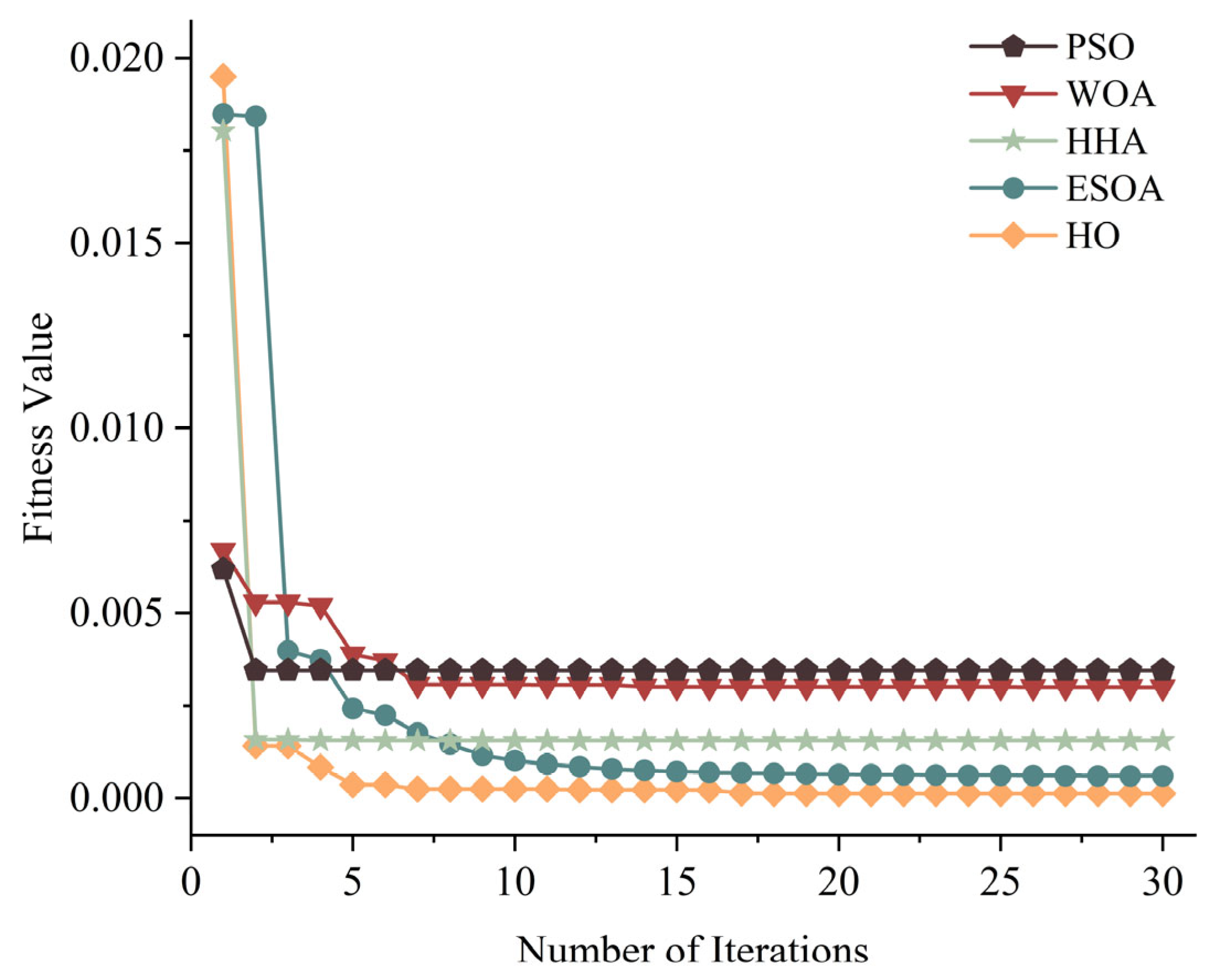

3.3.2. Comparison of Optimization Algorithms

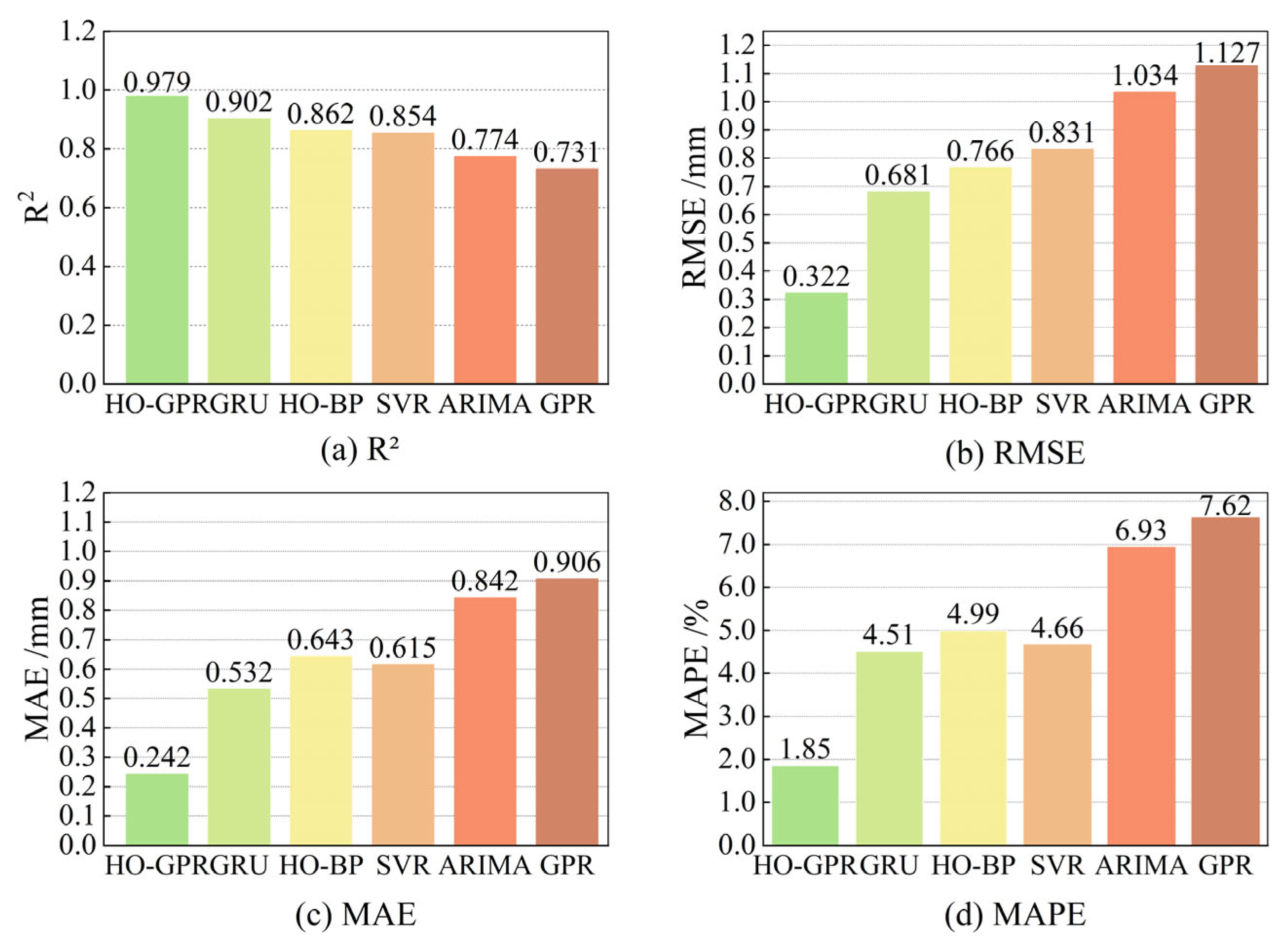

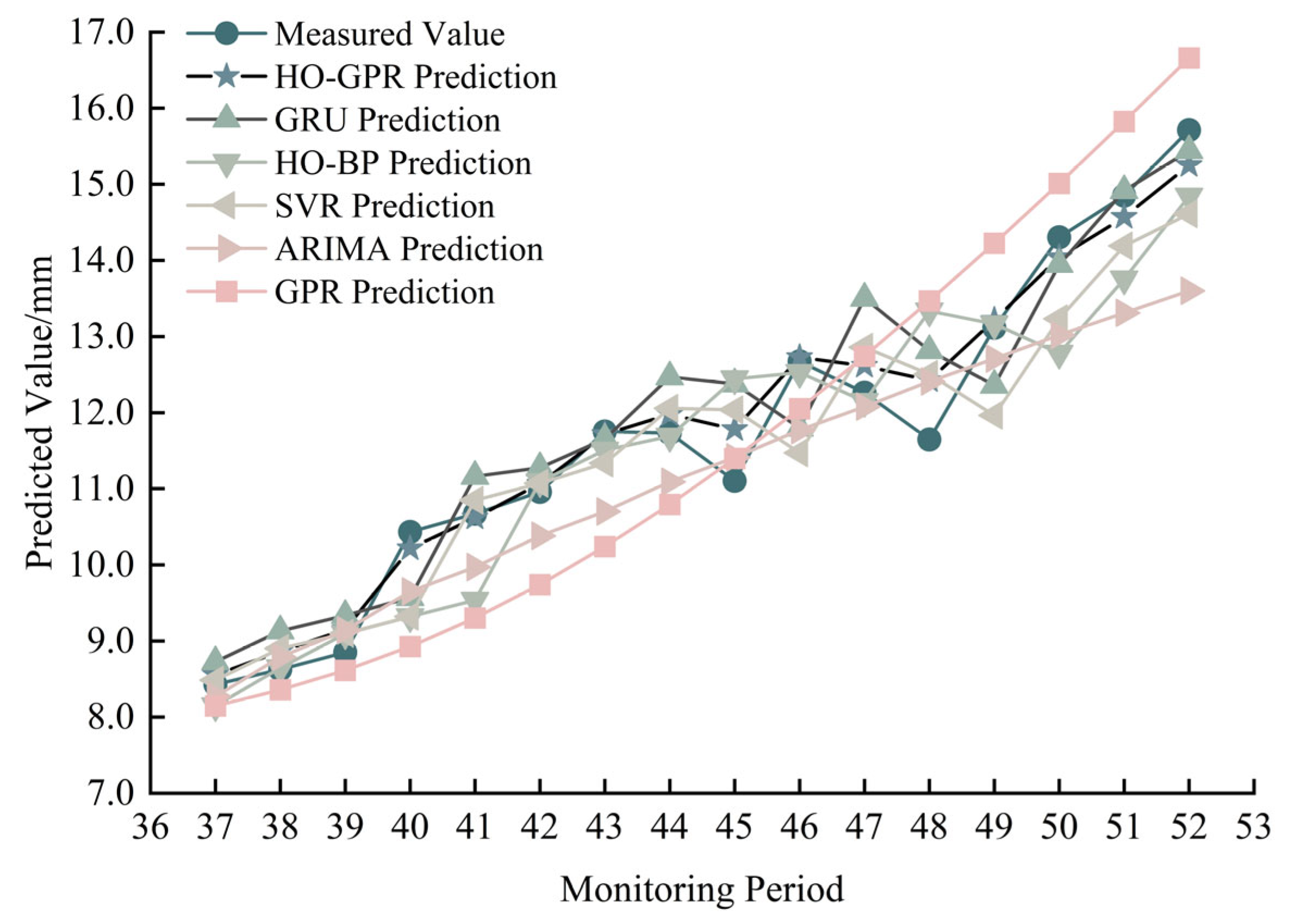

3.3.3. Comparative Analysis of Different Models

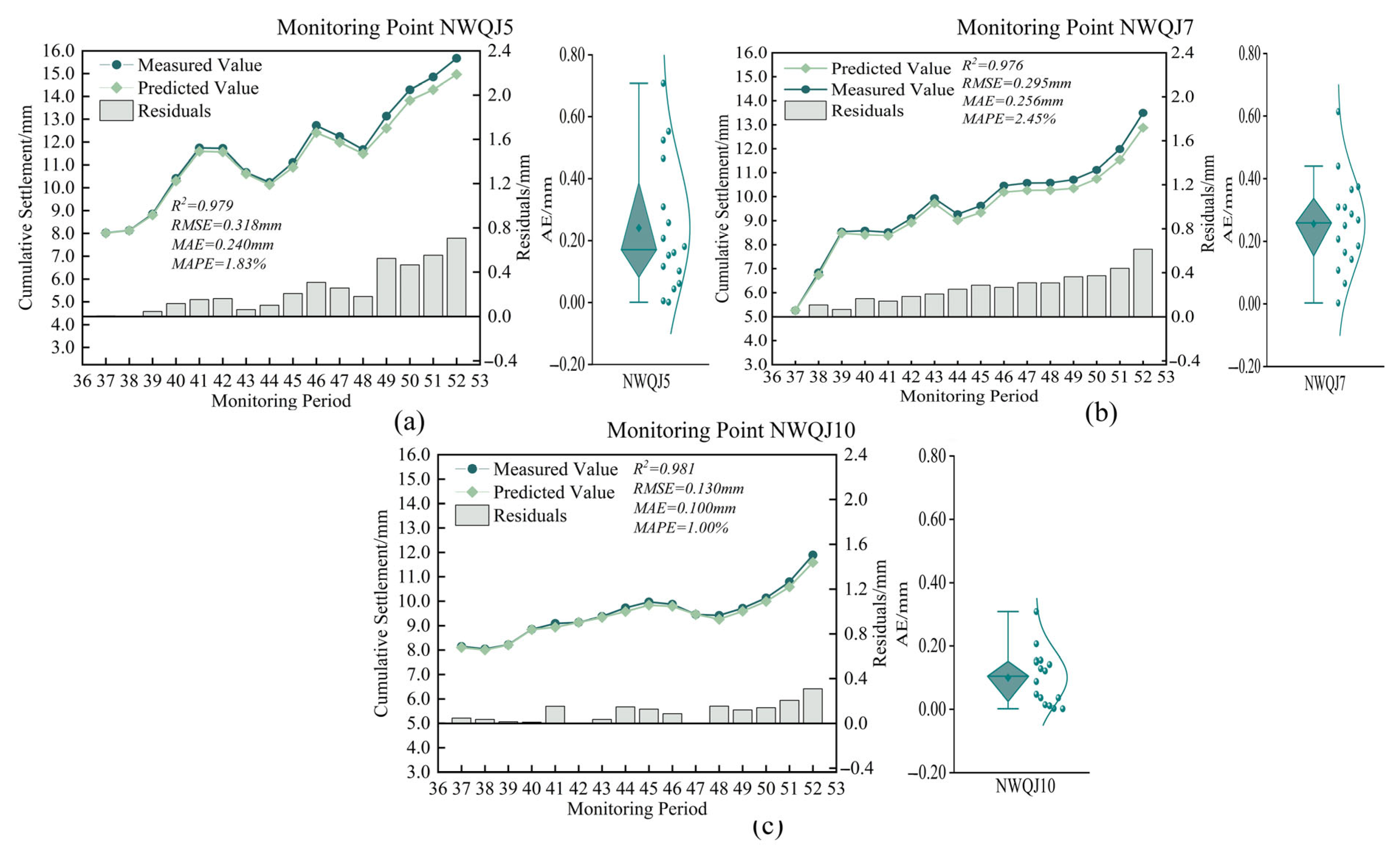

3.3.4. Generalization Validation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, Y.; Fei, G. Deformation prediction model of metro based on GA-BP neural network. J. Hefei Univ. Technol. 2021, 44, 1513–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Di, H.; Xu, Y. Machine learning based prediction model for long-term settlement in a metro-shield tunnel. Urban Rapid Rail Transit 2022, 35, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Kasama, K.; Wang, G.; Takahashi, A. Assessing the influence of geotechnical uncertainty on existing tunnel settlement caused by new tunneling underneath. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 155, 106189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.Q.; Wang, S.H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, P.Y.; Dong, F.R. Prediction method of tunnel deformation based on time series and DEGWO-SVR model. J. Northeast. Univ. 2021, 42, 2275–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.Y.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Ding, H.J.; Rao, Y.-K.; Yang, T.; Zhou, M.-Z. A novel intelligent displacement prediction model of karst tunnels. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Jiang, J.; Bao, W.; Ma, X.; Liu, H. Research on predicting structural deformation of subway tunnels induced by foundation pit construction integrating spatiotemporal features. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 3592–3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Guo, J.; Liu, H. Application of Time Series Analysis Model in Subway Tunnel Settlement Deformation Monitoring. Geomat. Spat. Inf. Technol. 2022, 45, 238–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, R.; Dong, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, K. Prediction of Settlement of Shield Tunnel Subway Tunnel Roof Based on WOA-BP Neural Network. J. Basic Sci. Eng. 2025, 33, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, B.; Tian, L.; Zhang, G. Time Series Prediction on Settlement of Metro Tunnels Adjacent to Deep Foundation Pit by Clustering Monitoring Data. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 27, 2180–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, J.; Shi, Z.; Li, L.; Li, M.; Jin, D.; Dong, G. Prediction of Surface Settlement Induced by Large-Diameter Shield Tunneling Based on Machine-Learning Algorithms. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 4174768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleti, S.; Panchumarthi, L.Y.; Kallam, Y.R.; Parchuri, L.; Jitte, S. Enhancing Forecasting Accuracy with a Moving Average-Integrated Hybrid ARIMA-LSTM Model. SN Comput. Sci. 2024, 5, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Qin, S.; Li, P.; Ge, C.; Yang, M.; Xie, Z. Deep excavation deformation prediction method based on BP Neural Network with integrated attention mechanism. J. Beijing Jiaotong Univ. 2025, 49, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J.; Zhu, J.; Guo, Y.; Xie, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, P. A multi-factor-driven approach for predicting surface settlement caused by the construction of subway tunnels by undercutting method. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, K.; Sharafat, A.; Seo, J. Digital Twin-Driven Framework for TBM Performance Prediction, Visualization, and Monitoring through Machine Learning. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafat, A.; Latif, K.; Seo, J. Risk analysis of TBM tunneling projects based on generic bow-tie risk analysis approach in difficult ground conditions. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 111, 103860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wu, H.-N.; Chen, R.-P.; Chan, T.H. Hybrid meta-heuristic and machine learning algorithms for tunneling-induced settlement prediction: A comparative study. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 99, 103383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, X.; Wang, J.; Lu, L. Adaptive Deformation Feature Analysis Based on Gaussian Process Regression and Its Application. Sci. Surv. Mapp. 2024, 49, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.X.; Zhou, Y. A Prediction Method of Ground Deformation in Subway Tunnel Construction based on Gaussian Process Regression. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Application of Artificial Intelligence (IAAI), Harbin, China, 25–27 December 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Jiang, A.N.; Yang, X.R. Tunnel displacement prediction under spatial effect based on Gaussian process regression optimized by differential evolution. Neural Netw. World 2021, 31, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.Y. Application of Gaussian Process Machine Learning in Deformation Prediction of Foundation Pit of Subway Station Near River. Hebei J. Ind. Sci. Technol. 2022, 39, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Su, Q.; Deng, Z.; Wang, C.; Cui, M.; Zhou, C. Research on Deformation Prediction and Application of Subway Station Foundation Pit Based on GF-GPR. J. Hefei Univ. Technol. 2025, 48, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lyu, C.; Huo, J.; Wang, S.; Chen, J. Gaussian Process Regression for Transportation System Estimation and Prediction Problems: The Deformation and a Hat Kernel. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 22331–22342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.H.; Mehrabi Hashjin, N.; Montazeri, M.; Mirjalili, S.; Khodadadi, N. Hippopotamus optimization algorithm: A novel nature-inspired optimization algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, R.; Floris, G.; Scionis, L.; Piras, G.; Pintor, M.; Demontis, A.; Giacinto, G.; Biggio, B.; Roli, F. HO-FMN: Hyperparameter optimization for fast minimum-norm attacks. Neurocomputing 2025, 616, 128918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Peng, J.; Ren, L.; Gao, B.; Guo, J.; Wang, Z.; Han, H. Forecasting of Horizontal Deformation in Retaining Piles of Subway Station Deep Foundation Pits Based on the CEEMDAN-SSA-ELM-LSTM Model. J. Disaster Prev. Mitig. Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, P.; Liu, F.; Zhang, J. Land Subsidence Prediction Model Based on the Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network Optimized Using the Sparrow Search Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.-S.; Yuan, Y.; Long, M.; Yao, R.-H.; Jia, L.; Liu, M. Prediction of surface settlement around subway foundation pits based on spatiotemporal characteristics and deep learning models. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 168, 106149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Qin, Y.; Meng, X.; Xie, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Y. Prediction model of land surface settlement deformation based on improved LSTM method: CEEMDAN-ICA-AM-LSTM (CIAL) prediction model. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Period | Date | Cumulative Settlement/mm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NWQJ5 | NWQJ7 | NWQJ10 | ||

| 1 | March 2019 | −0.18 | −0.2 | −0.49 |

| 2 | April 2019 | −0.37 | 0.2 | −0.78 |

| 3 | May 2019 | 0.02 | 0.0 | −0.42 |

| ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ | ⋯ |

| 50 | April 2023 | 14.30 | 11.92 | 9.30 |

| 51 | May 2023 | 14.85 | 11.98 | 10.80 |

| 52 | June 2023 | 15.71 | 13.49 | 11.90 |

| Optimization Algorithm | R2 | RMSE/mm | MAE/mm | MAPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOA | 0.937 | 0.469 | 0.379 | 2.95% |

| PSO | 0.959 | 0.389 | 0.318 | 2.51% |

| HHA | 0.967 | 0.371 | 0.302 | 2.36% |

| ESOA | 0.968 | 0.364 | 0.295 | 2.42% |

| HO | 0.973 | 0.331 | 0.264 | 2.03% |

| Prediction Model | R2 (95% CI) | p-Value | RMSE (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HO-GPR | 0.976 (0.951–0.987) | - | 0.317 (0.205–0.433) | - |

| GRU | 0.885 (0.741–0.958) | <0.001 | 0.674 (0.431–0.899) | <0.001 |

| HO-BP | 0.853 (0.657–0.944) | <0.001 | 0.756 (0.581–0.922) | <0.001 |

| SVR | 0.839 (0.676–0.918) | <0.001 | 0.816 (0.519–1.129) | <0.001 |

| ARIMA | 0.747 (0.492–0.874) | <0.001 | 1.015 (0.717–1.310) | <0.001 |

| GPR | 0.674 (0.175–0.902) | <0.001 | 1.109 (0.731–1.454) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chai, J.; Yang, X.; Deng, W. Intelligent Prediction of Subway Tunnel Settlement: A Novel Approach Using a Hybrid HO-GPR Model. Buildings 2026, 16, 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010192

Chai J, Yang X, Deng W. Intelligent Prediction of Subway Tunnel Settlement: A Novel Approach Using a Hybrid HO-GPR Model. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):192. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010192

Chicago/Turabian StyleChai, Jiangming, Xinlin Yang, and Wenbin Deng. 2026. "Intelligent Prediction of Subway Tunnel Settlement: A Novel Approach Using a Hybrid HO-GPR Model" Buildings 16, no. 1: 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010192

APA StyleChai, J., Yang, X., & Deng, W. (2026). Intelligent Prediction of Subway Tunnel Settlement: A Novel Approach Using a Hybrid HO-GPR Model. Buildings, 16(1), 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010192