Abstract

Sacred heritage landscapes face significant challenges in engaging Generation Z tourists. To understand their visual processing and emotional responses, this study grounded in Cognitive Appraisal Theory (CAT), employed a mixed-methods approach with Chinese youth. Study 1 (N = 35) uses eye-tracking to examine the visual attention of Gen Z to different sacred heritage types, revealing that natural sacred sites yield the highest First Fixation Duration (FFD) and Average Fixation Duration (AFD), alongside stronger subjective preferences—highlighting the role of biophilia and perceptual fluency. Study 2 constructs a moderated mediation model with a questionnaire (N = 300), identifying a “Novelty → Awe → Place Attachment” pathway and the moderating role of mindfulness. The research identifies the specific visual processing patterns of Gen Z and provides a psychological model for place attachment, offering empirical insights for designing intergenerationally inclusive heritage landscapes.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the global cultural heritage tourism market has experienced continuous growth [1]. In 2024, the market reached USD 604.38 billion and is projected to expand to USD 778.07 billion by 2030, with an average annual growth rate of 4.5%, making it one of the fastest-growing sectors in tourism [2,3]. Cultural tourism, rooted in heritage resources, not only satisfies the demand for diverse cultural experiences but also promotes the preservation and revitalization of heritage [1,4]. Notably, according to UNESCO, approximately 20% of World Heritage Sites possess religious or spiritual attributes [5]. Sacred heritage landscapes, as vital carriers of cultural transmission and collective identity, hold a prominent position in heritage tourism [6]. Meanwhile, Generation Z (typically defined as those born between 1995 and 2010) is emerging as a key demographic in the global tourism market [7]. However, sacred heritage landscape faces multiple challenges under the dual pressures of modernization and globalization. These include increasing tensions between tourism development and the preservation of cultural values, as well as issues among young tourists such as insufficient attraction, lack of emotional resonance, and difficulty in conveying spiritual significance. Understanding the perceptual preferences pathways and behavioral patterns of young people has become a crucial topic in heritage communication and revitalization efforts.

Simultaneously, although research in this field has become more abundant in recent years, mainstream methodologies still primarily rely on questionnaires and in-depth interviews [8,9]. These approaches often fall short in capturing tourists’ visual attention and cognitive processing in complex heritage environments. In heritage tourism contexts, how emotional preferences of Generation Z tourists are formed and the underlying psychological mechanisms require further exploration. These factors are critical to enhancing the attractiveness of heritage sites and improving the quality of tourist experiences.

Based on the Cognitive Appraisal Theory (CAT), this study investigates the visual perception and emotional connection of Generation Z tourists with sacred heritage, using a mixed-methods approach that combines eye-tracking and subjective questionnaires. It has two primary objectives: first, to examine how different types of sacred heritage influence the visual preferences of Generation Z tourists; second, to construct the psychological pathway through which place attachment forms, revealing the intrinsic relationship between heritage experience and emotional bonding. Accordingly, the study seeks to answer the following scientific questions:

RQ1.

How do different types of sacred heritage landscapes affect the visual attention and preferences of Generation Z tourists?

RQ2.

How is place attachment to sacred heritage constructed among this cohort?

This study contributes in several key aspects: (1) By integrating eye-tracking experiments with structured questionnaires, this study preliminarily reveals the visual attention and preference patterns of Generation Z. It further examines the psychological pathway to place attachment using a chained mediation and moderation model, based on a combination of traditional subjective ratings and eye-tracking validation, thus expanding the mixed-methods research paradigm in heritage tourism perception studies. (2) The study constructs a mechanistic pathway of “novelty–awe–place attachment,” highlighting the moderating effect of individual mindfulness, thereby deepening the theoretical understanding of place attachment formation mechanisms. (3) It focuses on Chinese Generation Z tourists, addressing the challenges of generational engagement and communication faced by heritage sites, and offers empirical support for research on generational tourism behavior. (4) The perceptual and emotional mechanisms of Generation Z users are analyzed to provide a data-driven foundation and psychological modeling for smart tourism, personalized recommendation systems, and immersive heritage presentations.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Sacred Heritage Landscapes and Generation Z Tourists

Sacred heritage landscape refers to spaces that possess both cultural value and religious or spiritual symbolism, including places of worship, pilgrimage routes, memorial sites, and natural landscapes imbued with spiritual significance [10,11]. As highly ritualized spatial entities, sacred heritage sites evoke a sense of the sacred, convey belief systems and traditions, and enhance visitors’ place attachment and spiritual experiences [12,13], playing a crucial role in community cohesion and cultural identity [6]. Existing studies have primarily focused on the spatial construction of meaning [14], heritage site management and conservation [10], and the visitor experience [15]. While sacred heritage has garnered increasing scholarly attention in cultural heritage research, empirical investigations into its visual appeal mechanisms and tourist perception remain limited.

Research has shown that Generation Z plays a vital role in shaping the future of the tourism industry [16]. Typically defined as individuals born between 1995 and 2010, Generation Z is often described as “digital natives” raised in an era of internet proliferation and digital media. They tend to have strong digital literacy, exhibit distinct consumer behaviors, favor visual and interactive communication channels, and habitually express and share emotions via social media [7]. In the tourism context, Generation Z seeks personalized and experiential cultural interactions, showing a marked preference for visually stimulating and instantly gratifying content [17]. However, current heritage tourism research primarily focuses on general tourists [18] and local communities [19], with limited attention paid to the specific generational characteristics and preferences of Generation Z.

2.2. Heritage Preferences and Eye-Tracking Technology

Numerous studies have been conducted within academia on the perception of heritage preferences, primarily employing methods such as questionnaires and interviews [8,9]. In recent years, with advances in technology, visual methodologies have increasingly been introduced into heritage research. Among these, eye-tracking technology has become a key tool, enabling the quantification of tourists’ visual attention to elements within heritage spaces—such as fixation count and duration—thus revealing characteristics of visual appeal [20,21]. For example, Zheng et al. [20] employed mobile eye-tracking devices at Wanshou Palace in Nanchang to analyze visual perception differences among groups in a commercialized heritage context, finding that participants with architectural backgrounds paid more attention to structural details, while ordinary tourists preferred commercial features. Similarly, Li et al. [22] investigated tourists’ visual attention and preferences toward intangible cultural heritage (ICH) using eye-tracking and questionnaires. Their findings revealed a distinct preference for folk customs and craftsmanship, with tourists primarily focusing on personality traits, cultural elements, and aspects of daily life. These results offer valuable insights for the development of ICH tourism. This study integrates eye-tracking with questionnaires to record the visual metrics of Generation Z participants when viewing sacred heritage images, aiming to identify their visual attention mechanisms and preference tendencies. The following hypotheses are proposed:

H1.

Different types of sacred heritage significantly influence Generation Z tourists’ subjective preferences.

H2.

Different types of sacred heritage induce significant differences in visual attention mechanisms.

2.3. Place Attachment and Cognitive Appraisal Theory

Place attachment is a central concept in human geography, environmental psychology, and tourism studies, referring to the positive emotional connection and psychological sense of belonging between individuals and specific places [23]. It is generally believed that place attachment comprises two dimensions: Place Identity (the integration of place with self-concept) and Place Dependence (the extent to which a place satisfies functional needs) [24]. Research has demonstrated that place attachment not only enhances tourists’ intention to revisit and loyalty, but in the context of heritage tourism, it also plays a significant role in shaping identity and collective memory [25,26,27].

The development of place attachment is linked to tourists’ sensory perception and emotional experiences triggered by environmental stimuli [28], and can be interpreted using the Cognitive Appraisal Theory (CAT). Proposed by Lazarus, this theory emphasizes that emotions do not stem directly from external stimuli but from individuals’ subjective cognitive evaluations of those stimuli [29]. Specifically, individuals typically undergo a primary appraisal, assessing whether a situation is relevant to their goals, followed by a secondary appraisal, evaluating whether they possess sufficient resources to cope with the situation. These appraisal processes collectively determine the emotions experienced by individuals and subsequently influence their attitudes and behavioral intentions [29]. In the field of tourism studies, relevant applications of CAT have emerged; for instance, Li et al. [30] explored whether incorporating modern elements into traditional Chinese opera could attract younger festival participants. Overall, CAT offers critical theoretical support for elucidating the cognitive pathways of tourists’ emotional experiences and their behavioral outcomes.

2.4. The Mediating Role of Novelty

Novelty refers to the perceived newness and uniqueness of a tourist experience, and is considered one of the key dimensions in the cognitive evaluation of tourism [31]. As a major motivator for exploring new destinations, the perception of novelty can elicit emotions such as interest and surprise, thereby enhancing the memorability and enjoyment of the experience [32]. Previous studies have shown that novelty not only moderates the effect of tourism experiences on positive emotions, but also significantly influences tourists’ subsequent behavioral intentions [33]. For example, Song et al. [34] found that agricultural heritage systems evoke tourists’ sense of novelty through creative elements such as legends and farming knowledge, thereby enhancing enjoyment and confirming the mediating role of novelty in shaping cultural identity. According to CAT, novelty is understood as a cognitive appraisal outcome based on external stimuli [30]. In the context of sacred heritage, the distinctive ambiance and heterogeneous cultural elements present in sacred landscapes may provide Generation Z tourists with potent novelty stimuli. Such novel experiences enhance interest and positive affect, forming the emotional basis for future behavioral intentions [28,35]. Based on the above theoretical foundations and reasoning, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H3.

Generation Z tourists’ perceived novelty of sacred heritage has a positive influence on their place attachment.

2.5. Mechanisms of Awe

Awe is a complex emotion elicited by stimuli that are grand, rare, or that transcend ordinary cognitive frameworks, and is typically characterized by a sense of self-diminishment and subsequent cognitive reappraisal [36,37]. Awe is rooted in religious experiences, aesthetic appreciation, and existential reflection, and is closely associated with psychological states such as the “sublime” and “spiritual elevation” [37]. Powell et al. [38] identified five core dimensions of awe: spiritual connection, transformative experience, clarity of values, harmony between humans and nature, and a sense of humility. Existing research has demonstrated the mediating role of awe in tourism experiences and its capacity to enhance individuals’ openness and tolerance, thereby influencing tourists’ loyalty to and satisfaction with destinations [37,39]. Furthermore, novelty, as a cognitive appraisal, generally precedes emotional responses [30]. Darbor et al. [40] further observed that awe is particularly centered on the perception and observation of novel stimuli. This study posits that, in the context of sacred heritage sites, visual novelty first triggers tourists’ attention and exploratory motivation, which subsequently leads to feelings of humility and smallness, thereby deepening emotional attachment. Based on these theoretical insights, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4.

Awe has a significant positive predictive effect on place attachment.

H5.

Novelty and awe jointly serve as significant chain mediators in the influence of sacred heritage experiences on place attachment.

2.6. The Moderating Role of Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a psychological trait referring to an individual’s conscious focus on present-moment experiences, characterized by non-judgmental awareness of internal sensations and external information [41]. Research has shown that mindfulness enhances tourist satisfaction by increasing self-awareness, thereby contributing to more meaningful travel experiences [41,42]. Individuals with high levels of mindfulness are more adept at perceiving emotional cues and environmental details, demonstrating stronger emotional regulation and immersive engagement [43]. Kiken et al. [44] found that individuals with higher mindfulness levels are more likely to transform appreciation of present-moment experiences into positive emotions, suggesting that mindfulness enhances the emotional benefits derived from positive events. Moreover, Bishop et al. [45] defined mindfulness as the intentional and non-evaluative attention to the present, which entails curiosity and openness toward the current context. Mindfulness also deepens engagement with emotional experiences, allowing individuals to explore and reflect more profoundly on the emotions elicited by awe [46]. In light of the above, this study posits that the level of mindfulness may influence the emotional intensity of Generation Z tourists’ responses to novelty in heritage sites. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6.

Mindfulness moderates the relationship between novelty and awe, such that the positive predictive effect of novelty on awe is stronger under conditions of high mindfulness.

3. Research Design

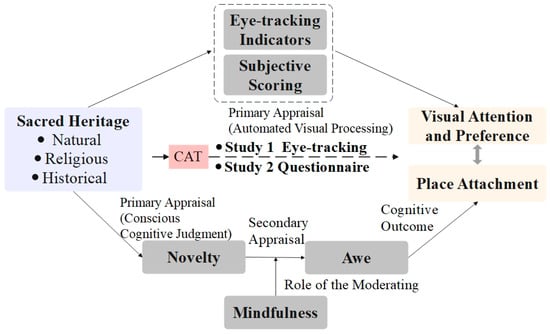

This study is grounded in Cognitive Appraisal Theory (CAT) as its core theoretical framework, integrating approaches from heritage science, environmental psychology, and cognitive neuroscience, and is structured around two sub-studies. Although the participant groups in the two studies were independent, both consisted of Generation Z individuals, allowing the results to be generalized to a shared population inference. Furthermore, the use of multiple independent yet theoretically interconnected experimental designs to construct a mechanism pathway has been widely validated by prior research [30,47] and is recognized as a common and rigorous paradigm in the social sciences. A mixed design combining objective and subjective methods facilitates a deeper understanding of the psychological responses and emotional construction processes of Generation Z tourists in sacred heritage sites (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

Study 1 focuses on the unconscious primary appraisal stage within the framework of CAT, utilizing a within-subject design. It incorporates eye-tracking metrics and subjective preference ratings. The independent variable comprises three types of sacred heritage (historical, religious, and natural). Dependent variables include eye-tracking indicators such as Fixation Count (FC), Total Fixation Duration (TFD), First Fixation Duration (FFD), Average Fixation Duration (AFD), and subjective preference scores. Using Repeated Measures ANOVA (RM-ANOVA), Study 1 addresses the question of “What”: specifically, during the primary appraisal stage, how Generation Z tourists display visual attention and preferences toward different types of sacred heritage landscapes (e.g., showing greater preference for natural landscapes). This study, grounded in the pre-conscious perception stage of CAT, employed eye-tracking experiments to capture automated perceptual data, thereby revealing instantaneous differences in “stimulus attractiveness.”

Study 2 addresses the subjective cognitive appraisal and emotional attribution phases of CAT. It employs standardized scales in a large-sample survey to systematically measure the chained mediators (novelty and awe), the moderator (mindfulness), and the outcome variable (place attachment) associated with sacred landscape experiences. In contrast, Study 2 addresses the questions of “Why” and “How”, namely, how Generation Z, during subjective perception, progresses from primary appraisal (e.g., novelty) and secondary appraisal to the elicitation of emotions (e.g., awe), which ultimately transform into the formation of place attachment. This study not only further validates the preference findings of Study 1 but also reveals the underlying psychological pathways through structural modeling. Therefore, Study 2 is not a mere replication of Study 1 but rather a critical complement at the level of psychological mechanisms, establishing a complete cognitive chain of perception–appraisal–emotion–attachment within the CAT framework.

Specifically, in the process of deeper subjective engagement with sacred landscapes, individuals consciously perform a primary appraisal of dimensions such as novelty when exposed to external stimuli, determining whether the landscape is perceived as novel or intriguing. This process reflects a cognitively engaged mechanism of conscious evaluation within the CAT framework. Subsequently, secondary appraisal is activated, during which individuals engage in deeper cognitive processing of the meaning and impact of the stimuli, thereby eliciting the core emotional experience of awe. Awe further facilitates the formation of a profound emotional bond between the individual and the place, ultimately contributing to the development of place attachment as a cognitive outcome. This reflects an extension of the “cognition–emotion–belonging” chain proposed by CAT. Meanwhile, mindfulness, as a psychological regulatory trait, enables tourists to remain more focused on the present moment, enhancing their perception and integration of external stimuli, which in turn modulates the intensity and nature of their emotional responses during the appraisal process. Study 2 reveals how tourists, through imaginative immersion in sacred landscapes, construct emotional attachment to the destination at the individual level.

Moreover, the eye-tracking experiment offers objective and fine-grained evidence of visual attention, while the questionnaire provides large-sample, mechanism-level subjective psychological data. The combination of the two approaches creates complementary strengths, enhancing the study’s external validity and causal interpretability. This methodological approach has been widely applied in the fields of heritage, tourism, and psychology.

In summary, the two studies jointly establish a CAT-based psychological mechanism pathway, outlining a progressive emotional development process among Generation Z tourists—from perceptual input to emotional construction.

4. Study 1

4.1. Participants

A power analysis for sample size was conducted using G*Power 3.1. Based on a repeated-measures ANOVA model with a medium effect size (f = 0.25), significance level α of 0.05, power of 0.80, and three predictors, the minimum required sample size was calculated to be 28. To account for possible data loss or eye-tracking failures, a total of 35 participants (N = 35), including 15 females, were recruited for the experiment. All participants belonged to the Generation Z cohort (born between 1995 and 2010) and were recruited offline through campus-based methods, had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and reported no neurological or visual impairments. To ensure data integrity, participants were instructed to abstain from alcohol and caffeine prior to the session.

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the College of Architecture and Urban Planning at Tongji University and complied with the ethical standards set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent, agreeing to the use of their data for scientific purposes and were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time. All collected data were anonymized and handled with strict confidentiality. Each participant received a remuneration of RMB 60 upon completing the study.

4.2. Experimental Materials

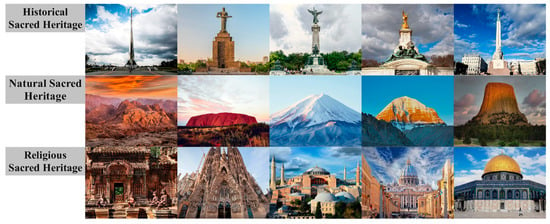

In the early stages of the study, sacred heritage was classified into three categories based on relevant literature [6,48,49], expert consultation, and technical requirements for image stimuli in eye-tracking research: (1) Historical Sacred Heritage—memorial sites revered for their historical significance; (2) Natural Sacred Heritage—natural locations such as sacred mountains, lakes, or forests with spiritual meaning; and (3) Religious Sacred Heritage—sacred and solemn structures such as temples and churches.

Existing studies have shown that images can effectively simulate tourists’ perceptual experiences of actual landscapes [50,51]. Accordingly, from February to March 2025, researchers selected high-quality images of sacred heritage sites with strong typicality and global recognition from the photo-sharing platform Flickr (https://www.flickr.com/). The selection criteria required that images conformed to the category definitions, featured clearly defined subjects, had well-composed visuals, and maintained consistency in shooting angle and dimensions. In addition, to ensure both the representativeness and distinctiveness of each category, images classified under Natural Sacred Heritage primarily featured mountain landscapes; the Religious Sacred Heritage images emphasized architectural symbolism; and the Historical Sacred Heritage images consistently depicted monument-style structures. An initial pool of 56 candidate images was collected. Following established rating methods for experimental stimuli in previous research [52], three professors specializing in cultural heritage and landscape architecture were invited to assess the heritage attributes of each image. The five top-rated images from each category were selected, resulting in a final set of 15 images (3 × 5) for the formal experiment (Figure 2). All images were standardized using Adobe Photoshop 2023, with specifications and resolution uniformly set to 2126 × 1654 pixels at 300 dpi.

Figure 2.

Eye-tracking stimuli for the three types of sacred heritage.

4.3. Experimental Procedure

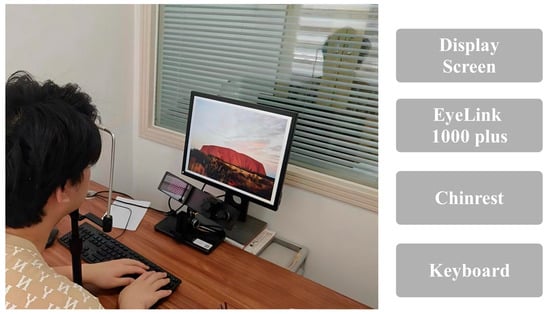

The experiment utilized the EyeLink 1000 Plus desktop eye-tracker, operating at a sampling rate of 2000 Hz. The laboratory environment was softly lit and free from distractions. Participants were seated approximately 60 cm from the monitor, with their heads stabilized by a chinrest (Figure 3). Stimulus presentation and eye movement data collection were controlled by the Experiment Builder software (version 2.3.4).

Figure 3.

During the experiment, participants’ heads were stabilized using a chinrest while eye data were recorded via EyeLink 1000 Plus.

Prior to the experiment, participants received a brief explanation of the task procedure and equipment operation from the researchers. They were then seated in front of the monitor, adjusted to a comfortable posture and optimal eye-tracking angle. All participants completed a standard nine-point calibration, ensuring recording accuracy within 0.5 degrees of visual angle. Before the main task, participants completed a set of practice trials to familiarize themselves with the experimental procedure.

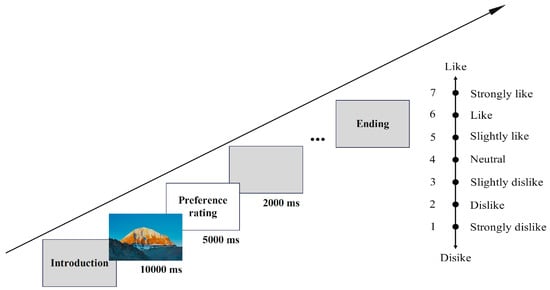

The experimental procedure was as follows (Figure 4): (1) At the beginning of each trial, a fixation cross was presented at the center of the screen for 1000 ms to focus attention and signal the start of the trial; (2) Subsequently, an image of a heritage landscape was displayed for 10,000 ms. Participants were instructed to view the image naturally, as if they were physically present at the site; (3) Immediately after the image presentation, a rating instruction screen appeared: “Please rate your preference for the landscape image just viewed (1 = strongly dislike, 7 = strongly like),” with corresponding key instructions. The rating period lasted 5000 ms; (4) After the rating, a gray screen was presented for 2000 ms as an inter-trial interval before the next trial began. A total of 15 landscape images were shown in random order to control for order effects and visual fatigue. The entire experiment lasted approximately 10–15 min. A researcher monitored the operation of the eye-tracker from an adjacent room and recorded relevant observations. All equipment functioned properly throughout, and all participant data were valid.

Figure 4.

The experimental procedure, where participants were required to rate each image using a 7-point Likert scale after its presentation.

4.4. Data Analysis

Referring to relevant studies [21,53], we selected four eye-tracking metrics: TFD, FC, FFD, and AFD. Definitions are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions and descriptions of the eye-tracking metrics used in this study.

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0. The procedure began with data cleaning (e.g., removal of outliers and merging of short fixations). Heritage category was treated as the independent variable, while preference ratings and eye-tracking metrics served as dependent variables. RM-ANOVA was conducted to examine differences in visual preference and fixation patterns among the three types of sacred landscapes, with Bonferroni post-hoc correction applied when necessary. Additionally, fixation heatmaps were generated via Data Viewer software to visually illustrate participants’ spatial attention patterns based on eye-tracking data.

4.5. Experimental Results

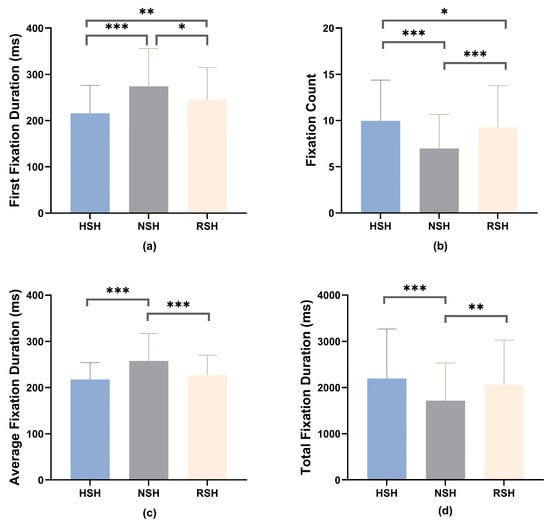

To explore how Generation Z tourists visually process and perceive preferences for different sacred heritage landscapes, this study utilized an eye-tracking experiment to collect four core indicators: FFD, FC, AFD, and TFD. These were complemented by subjective visual preference ratings and analyzed using RM-ANOVA. (Table 2 and Figure 5 present the descriptive statistics and bar charts for the eye-tracking metrics, respectively.)

Table 2.

The statistical results of the four eye-tracking metrics across different types of sacred heritage (M ± SD).

Figure 5.

Visual attention metrics across three sacred heritage types: Historical Sacred Heritage (HSH); Natural Sacred Heritage (NSH); Religious Sacred Heritage (RSH). (a) First Fixation Duration (FFD); (b) Fixation Count (FC); (c) Average Fixation Duration (AFD); (d) Total Fixation Duration (TFD). Error bars represent ±1 SD. p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***).

The ANOVA results for the FFD metric indicated a significant main effect of heritage type, F (2, 33) = 18.560, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.529. Pairwise comparisons further revealed that the FFD for natural sacred heritage (274.28 ± 13.83 ms) was significantly higher than that for historical sacred heritage (215.80 ± 10.27 ms, p < 0.001) and religious sacred heritage (245.80 ± 11.62 ms, p = 0.037). In addition, the FFD for religious sacred heritage was also significantly higher than that for historical sacred heritage (p = 0.006).

The ANOVA results for the FC metric also showed a significant main effect of heritage type, F (2, 33) = 26.798, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.619. Further pairwise comparisons indicated that the number of fixations on historical sacred heritage (9.97 ± 4.41) was significantly higher than that on natural sacred heritage (6.98 ± 3.68, p < 0.001) and religious sacred heritage (9.25 ± 4.53, p = 0.038). Furthermore, the number of fixations on religious sacred heritage was also significantly higher than that on natural sacred heritage (p < 0.001).

At the level of the AFD metric, heritage type exerted a significant effect on AFD, F (2, 33) = 11.729, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.415. Further analysis showed that participants maintained the longest average fixation duration on natural sacred heritage (257.69 ± 59.76 ms), which was significantly higher than that for religious sacred heritage (227.11 ± 42.92 ms, p < 0.001) and historical sacred heritage (217.44 ± 36.27 ms, p < 0.001). However, there was no significant difference in AFD between the religious and historical sacred heritage categories (p = 0.129).

The variance analysis of the TFD metric revealed a significant main effect of heritage type, F (2, 33) = 9.900, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.375. Subsequent pairwise comparisons showed that participants spent the longest total fixation duration on historical sacred heritage (2195.07 ± 1073.00 ms), significantly more than that on natural sacred heritage (1719.34 ± 810.51 ms, p < 0.001), and more than that on religious sacred heritage (2060.09 ± 968.09 ms), though the latter difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.147). Meanwhile, the TFD for religious sacred heritage was significantly greater than that for natural sacred heritage (p = 0.003).

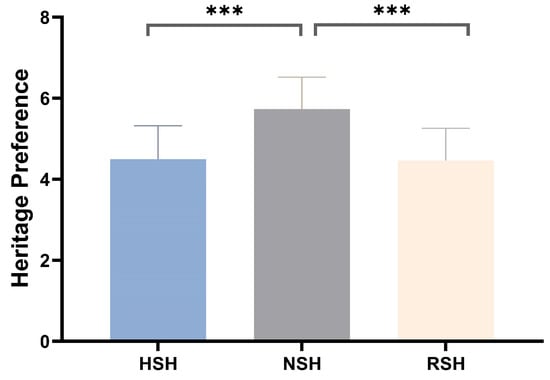

Using a 7-point Likert scale, we conducted key-based ratings to assess participants’ subjective visual preferences for different heritage landscapes. The results of the RM-ANOVA (Table 3 and Figure 6) indicated a significant main effect of heritage type, F (2, 33) = 39.306, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.704, supporting Hypothesis H1. This suggests that different types of sacred heritage significantly influence the subjective preferences of Generation Z tourists. Further pairwise comparisons revealed that natural sacred heritage received the highest preference scores (5.73 ± 0.79), which were significantly higher than those for historical heritage (4.50 ± 0.83, p < 0.001) and religious sacred heritage (4.46 ± 0.80, p < 0.001). In contrast, there was no significant difference between preferences for religious and historical sacred heritage (p = 0.824).

Table 3.

The average preference scores for the three sacred heritage types (M ± SD).

Figure 6.

The differences in preference among the sacred heritages. Error bars represent ±1 SD. p < 0.001 (***).

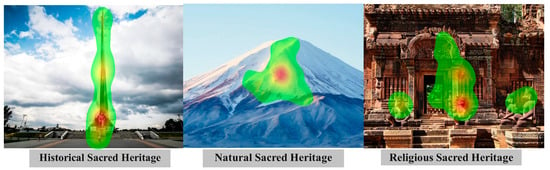

Furthermore, the study generated heatmaps based on gaze behavior prior to stimulus presentation. As shown in Figure 7, the gaze hotspots for historical sacred heritage were highly concentrated along the central axis, particularly focusing on the monument’s main structure and its base. This indicates a heightened attention toward the central and symbolic elements of the site. In contrast, natural sacred heritage exhibited a more dispersed gaze pattern, with hotspots centered around the mountain’s core, suggesting a tendency to process the overall contour rather than specific local details. The religious sacred heritage displayed a strongly structured gaze distribution, with hotspots concentrated around the temple’s main entrance and deity figures, and some fixation points distributed across symmetrically positioned sculptures. This spatial pattern reflects higher visual sensitivity to symbolic components in religious architecture. Overall, the heatmap results support the prior statistical analyses and Hypothesis H2, indicating that different types of sacred landscapes evoke distinct visual processing characteristics.

Figure 7.

Representative gaze heatmaps for the three types of sacred heritage.

5. Study 2

5.1. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

Study 2 utilized a questionnaire to collect data from Generation Z tourists regarding their place attachment to sacred heritage. To ensure adequate statistical power for the chained mediation and moderation regression analyses, a sample size analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1. Based on a multiple linear regression model with a medium effect size (f = 0.15), α = 0.05, power = 0.80, and six predictors, the minimum required sample size was determined to be 98. The questionnaire was distributed via the online platform Credamo (www.credamo.com). To immerse respondents in the context of sacred heritage, the survey began with a set of illustrated introductory materials. These included several example images of sacred sites identical to those used in Experiment 1, accompanied by brief textual descriptions depicting scenarios such as strolling through an ancient temple or visiting a serene sacred mountain. This “guided imagery” aimed to stimulate respondents’ imagination regarding sacred heritage experiences and to establish a shared psychological reference frame prior to answering the questionnaire. After completing the guided imagery, participants proceeded to answer the main body of the questionnaire.

The questionnaire consisted of psychometric scales and demographic questions. The psychological scales were adapted from established instruments and modified to fit the study context, all using a standardized 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) to enhance measurement sensitivity. The novelty dimension was adapted from Kim et al. [54] and Song et al. [34], comprising four items (e.g., “I perceive this as a novel and unique experience.”). Awe was measured using five items derived from Coghlan et al. [55] and Yan et al. [37], including items like “I felt a sense of indescribable solemnity.” Mindfulness was assessed through four items adapted from Lau et al. [56] and Kim and Kim [57], such as “I can focus on the present experience without dwelling on the past or worrying about the future.” Place attachment was measured using a four-item scale developed by Williams and Vaske [58], including statements such as “I have a deep emotional bond with this place” (see Table 4 for details).

Table 4.

Composition of questionnaire items by variable.

Participants were informed that the study was anonymous and conducted solely for academic purposes. The research protocol was approved by the internal review committee of the College of Architecture and Urban Planning at Tongji University. All participants were native or near-native Mandarin speakers. After excluding non-Generation Z individuals (those not born between 1995 and 2010) and invalid responses, a total of N = 300 valid samples were retained, with females comprising 59.7% and males 40.3%. To ensure semantic consistency, all English scales underwent a translation and back-translation procedure, followed by a small-scale pilot test prior to formal data collection. The results indicated that all scales demonstrated strong reliability and construct validity.

5.2. Research Results

The survey data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0. Initially, reliability and validity analyses of the scales were conducted, followed by causal relationship testing among variables using the PROCESS macro in SPSS. The reliability analysis (Table 5) showed that Cronbach’ s α coefficients for all variables ranged from 0.824 to 0.866, exceeding the 0.80 threshold, thus indicating high internal consistency and reliability of the instruments.

Table 5.

Reliability and validity test results of the questionnaire.

To further assess the construct validity of the scale, this study conducted both exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). In the EFA, principal component analysis was used with varimax rotation for factor extraction. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value was 0.890, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ2 = 2419.299, p < 0.001), indicating the suitability of the data for factor analysis. The analysis extracted four common factors, which together explained 67.851% of the total variance. All items exhibited factor loadings above 0.60 on their respective factors, with low cross-loadings, suggesting strong structural validity of the scale. The CFA further confirmed the scale’s convergent validity. Results showed that all latent variables had composite reliability (CR) values between 0.846 and 0.879, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70. The average variance extracted (AVE) ranged from 0.565 to 0.645, surpassing the 0.50 benchmark. Overall, the measurement scales demonstrated strong reliability and validity, providing a robust foundation for subsequent causal pathway analysis.

To examine the mediating roles of novelty and awe in the relationship between sacred heritage experience and place attachment, this study employed Hayes’ [59] PROCESS macro (Model 6) and conducted mediation analysis using the bootstrap method with 5000 resamples. The regression analysis results (Table 6) indicated that heritage had a significant positive effect on place attachment (total effect = 0.301, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.201, 0.402]), thereby supporting the proposed hypothesis. Further analysis revealed that heritage landscape significantly and positively predicted novelty (β = 0.376, 95% CI [0.289, 0.463]), and novelty in turn significantly predicted awe (β = 0.313, 95% CI [0.210, 0.415]), confirming the preconditions for the chained mediation pathway.

Table 6.

Results of the regression pathway analysis.

After controlling for the mediating variables, the direct effect of sacred heritage on place attachment was no longer significant (direct effect = 0.076, p = 0.154, 95% CI [−0.028, 0.181]), whereas both novelty (β = 0.257, 95% CI [0.132, 0.382]) and awe (β = 0.385, 95% CI [0.254, 0.516]) significantly predicted place attachment. These results indicate that the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable was fully mediated through the identified pathways, demonstrating a full mediation effect.

Further bootstrap analysis (Table 7) showed a significant indirect effect of sacred heritage landscapes on place attachment via novelty, with an indirect effect size of 0.097 (95% CI [0.044, 0.170]), supporting Hypothesis H3. These results suggest that the novel experiences perceived by visitors when encountering sacred heritage landscapes can effectively foster place attachment. The indirect effect through awe was also significant, with a value of 0.083 (95% CI [0.040, 0.155]), supporting Hypothesis H4. This indicates that awe elicited by sacred heritage serves as an important emotional pathway for establishing emotional bonds between visitors and the destination. Moreover, the chained mediation pathway from novelty to place attachment via awe was also significant (indirect effect = 0.045, 95% CI [0.023, 0.079]), confirming Hypothesis H5. This suggests that visitors’ perception of novelty at heritage sites can further strengthen place attachment by eliciting feelings of awe.

Table 7.

Indirect effect pathway analysis.

The study also employed the PROCESS macro to examine the moderating effect of mindfulness on the relationship between novelty and awe, using a three-step hierarchical regression analysis. The results (Table 8) indicated that in Model 1, novelty significantly and positively predicted awe (β = 0.423, p < 0.01), with R2 = 20.3%. In Model 2, after including the moderating variable mindfulness, the predictive effect of novelty remained significant (β = 0.352, p < 0.001), and mindfulness itself also showed a significant positive effect (β = 0.248, p < 0.001), increasing R2 to 26.2%. In Model 3, the interaction term (novelty × mindfulness) was added and found to be significant (β = 0.212, p < 0.001), with R2 further increasing to 29.1%, indicating that mindfulness significantly moderates the relationship between novelty and awe, thereby supporting Hypothesis H6.

Table 8.

Moderation effect test results.

Simple slope analysis indicated that at low levels of mindfulness (−1 SD), the effect of novelty on awe was not statistically significant (β = 0.1174, p = 0.088). At the mean level of mindfulness (SD), the path became significant (β = 0.2526, p < 0.001). At high levels of mindfulness (+1 SD), the slope further increased and remained significant (β = 0.3878, p < 0.001). This suggests that the higher the level of mindfulness, the stronger the facilitative effect of novelty on awe.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

To explore the psychological processing mechanisms and emotional construction pathways of Generation Z tourists within sacred heritage landscapes, this study integrated eye-tracking experiments and structured questionnaires. Study 1 examined visual responses to different types of sacred heritage sites. Preliminary results based on the Chinese Generation Z sample suggest that natural heritage sites attract more initial attention and sustained gaze, while historical heritage sites prompt more frequent visual searches. Subjective ratings also indicated a clear preference for natural heritage. Based on the cognitive appraisal theory, Study 2 developed a multivariate analytical model to test the chained mediation role of perceived novelty and awe between heritage experience and place attachment, with mindfulness significantly moderating the emotional transition from novelty to awe.

6.1. Visual Preferences and Attentional Processing Mechanisms of Sacred Heritage

Study 1 preliminarily identified key findings through the analysis of eye-tracking indicators and revealed that natural sacred heritage sites elicited the highest First Fixation Duration (FFD), indicating that such sites can instantly capture visitors’ initial attention due to their prominent physical features (e.g., majestic mountain contours) or inherent aesthetic value. This phenomenon may be attributed to the high attractiveness and physiological–psychological compatibility of natural environments with humans. This finding is consistent with related studies [60]. For example, Deng et al. [61] found that, compared to man-made structures, natural environments attract more visual attention. As Sparks and Wang [62] noted, the gentle “charm” of natural elements more easily draws attention. Ulrich’s theory on emotional restoration in natural environments further explains this: humans innately respond positively to non-threatening natural settings (e.g., vegetation, open spaces), an outcome of evolutionary adaptation [63]. For Chinese Generation Z, who grew up in highly urbanized settings, grand natural sacred landscapes may represent a striking “perceptual breakthrough” and take priority in bottom-up attentional processing mechanisms. These landscapes also exhibit higher Average Fixation Duration (AFD), suggesting that they are more likely to trigger deeper cognitive processing and emotional engagement [51,64]. Compared to visually complex and abstract historical or religious architectural landscapes, Generation Z seems to favor sustained yet low-effort attention toward natural sacred heritage, showing a certain degree of visual “gazing” or immersion. This can also be interpreted through the Processing Fluency Theory: natural schemata that are easier to process tend to elicit aesthetic pleasure, thereby enhancing immersive experience [65].

In eye-tracking studies, FC (fixation count) typically represents the frequency of visual searches and the breadth of visual information processing [66], while TFD (total fixation duration) reflects the overall amount of attentional resources allocated during visual processing [53,67]. The results show that both FC and TFD were highest when Chinese visitors engaged with historical commemorative heritage sites, indicating more frequent and sustained visual exploration in these scenarios. Interestingly, although religious sacred heritage sites are structurally complex and richly decorated, they elicited lower levels of visual processing than the relatively simpler historical commemorative landscapes. This may be due to the concentrated visual elements and axial symmetry typically found in monuments that compose historical commemorative heritage [68,69]. While viewing, visitors may need to shift their gaze repeatedly between the base, main body, and symbolic decorations of the monument to integrate its highly symbolic content. This higher fixation frequency suggests that visitors invest more conscious cognitive effort in interpreting environmental cues within historical commemorative settings. This finding aligns with previous research showing that people tend to exhibit higher fixation rates and longer processing times in environments rich in cultural symbolism or dense in information [70,71]. In contrast, although religious architecture is richer in detail, its visual complexity may surpass visitors’ immediate processing capacity, thereby reducing their motivation for deeper exploration. Previous studies suggest that overly complex visual scenes may lead to visual fatigue, causing fragmented gaze patterns and reduced depth of information processing [72]. Additionally, natural sacred heritage sites produced the lowest FC and TFD, suggesting that visitors process such environments more holistically and intuitively [73]. In summary, the variations in FC and TFD across heritage types reveal strategic differences in information processing among Chinese Generation Z visitors: for symbolically rich but less visually compelling landscapes, they tend to conduct extensive searches for meaning, whereas for visually attractive environments, attention is more focused on core elements to enable efficient processing.

In terms of subjective preference, the results revealed that Chinese Generation Z tourists tend to prefer natural sacred heritage to some extent, while their average level of appreciation for religious and historical commemorative heritage is significantly lower and nearly identical. These results align with existing literature, which has found that natural landscapes tend to evoke higher levels of affection among the general population [61,74], a trend also evident in Gen Z. Natural sacred heritage often features magnificent scenery and a unique atmosphere, fulfilling Gen Z tourists’ visual and emotional expectations. Psychologically, Gen Z tends to perceive travel as an opportunity to escape daily routines and pursue mental and physical well-being. Natural environments, with their novelty and restorative qualities absent in urban settings, thus gain their favor more easily [75,76]. Kellert and Wilson’s “Biophilia Hypothesis” also posits that humans possess an innate tendency to form emotional bonds with nature [77]. This study also challenges certain stereotypes about Generation Z, who are commonly viewed as digital natives favoring technology and creativity [78], with limited engagement in natural sacred environments [79]; however, the findings contradict this assumption. Moreover, although visitors demonstrated the highest cognitive engagement with historical memory landscapes (evidenced by the highest FC and TFD), their preference for these sites remained as low as that for religious landscapes. This finding challenges existing theories suggesting that visual attention drives preference formation [74]. One possible explanation is that religious beliefs and specific historical events often diverge significantly from the lived experiences of Chinese Generation Z, creating substantial “cultural distance.” In the absence of sufficient background knowledge or guided interpretation, the analytical cognitive effort required to comprehend such complex symbolism may lead to frustration, impeding the development of positive and seamless emotional experiences.

6.2. Place Attachment to Sacred Heritage Sites

Study 2 revealed that novelty plays a significant mediating role in the relationship between the experience of sacred heritage sites and place attachment. This implies that Chinese Generation Z tourists develop emotional bonds with destinations partly due to the unique and extraordinary experiences they encounter in these settings. This finding aligns with Marques et al. [80]. In the context of sacred heritage tourism, from awe-inspiring temples previously unseen to natural sanctuaries imbued with mystery—each offering refreshing experiences for Generation Z. The present study further confirms that Generation Z tourists do not passively receive environmental stimuli; instead, they actively engage in cognitive evaluations. When an environment is perceived as “novel” or “distinct from everyday life”, it triggers deeper emotional processing [81], serving as a crucial starting point for attributing special meaning and emotional value to the destination.

Beyond the sense of novelty, the study reveals that awe plays a crucial mediating role in the process by which sacred landscape experiences foster place attachment. Within the context of this research, sacred heritage sites—such as majestic mountains, grand religious architecture, and solemn ritual atmospheres—constitute vast and novel cultural environments that naturally evoke awe among Generation Z. Previous research has demonstrated that religious buildings, artistic expressions, and symbolic elements within sacred settings are vital conduits for eliciting awe [82]. When individuals are confronted with experiences beyond their cognitive grasp, they undergo cognitive stimulation [36,83]. Thus, awe can be regarded as a key bridge that transforms cognitive experience into emotional affiliation.

This study validated the chained mediation pathway from “novelty” to “awe”, revealing the progressive mechanism through which place attachment is formed among Chinese Generation Z tourists, and confirming the coherent emotional process posited by CAT [29]. Specifically, tourists initially perceive novel elements in the environment, which stimulate cognitive interest and evaluation of the destination (e.g., “This place is unique”). Subsequently, this sense of cognitive surprise evokes intense emotional responses such as awe (e.g., “I feel overwhelmed and awed by this place”). Ultimately, these emotional experiences are gradually internalized, transforming into place attachment and a sense of belonging (e.g., “I like it here and feel connected”). Furthermore, this study aligns closely with Scherer’s Component Process Model, which also positions the “novelty check” at the forefront of the stimulus appraisal sequence [84]. Some studies have also indicated that the core of experiencing awe lies in triggering cognitive accommodation, a process inherently involving novelty [85]. The chained mediation findings of this study exemplify this process within the context of sacred heritage tourism.

Notably, this study found that mindfulness significantly moderates the mediation pathway from perceived novelty to awe, indicating that individual differences among tourists can influence the strength of the cognition-to-emotion transformation. Specifically, tourists with high levels of mindfulness are more likely to experience intense emotions such as awe in response to novel experiences. The results align with existing research indicating that mindfulness is a receptive and attentive mental state toward present experiences, which enhances the depth of emotional involvement, including feelings of awe [57,86]. The research further points out that mindfulness training can enhance cognitive resources, allowing individuals to interpret information from new perspectives and remain open to novel experiences [41]. Therefore, when a highly mindful Generation Z tourist is immersed in a sacred heritage site, they are more likely to notice and engage with the unusual or distinctive aspects of their surroundings, deeply experiencing each novel detail. This heightened awareness allows novel stimuli to effectively activate emotional circuits, thereby naturally giving rise to a sense of awe. This finding also supports the notion that mindfulness enhances the richness and depth of emotional experiences, enabling individuals to fully appreciate the highlights of their travels [41,87]. In contrast, tourists with lower mindfulness levels may struggle to notice novel elements due to distraction or biased perception, resulting in a diminished or absent sense of awe.

From a theoretical perspective, this study integrates the Cognitive Appraisal Theory (CAT) across both perceptual and emotional dimensions, constructing a comprehensive psychological mechanism model within the context of heritage tourism. Study 1, based on eye-tracking data, reveals tourists’ visual attention preferences toward different landscape types. For instance, natural sacred landscapes, due to their strong sensory appeal, elicit prolonged gaze durations and higher levels of favorability. This suggests that tourists rapidly assess environmental stimuli in terms of value and aesthetics at the moment of encounter, reflecting an automatic, primary cognitive appraisal under the CAT framework. This initial perceptual judgment lays the foundation for subsequent emotional processing. Study 2, from a broader perspective, illustrates the emotional affiliation constructed after landscape experiences: feelings of novelty and awe indicate deep cognitive and emotional engagement with the environment (corresponding to the primary-secondary appraisal stages), and the formation of place attachment represents the cognitive outcome of this psychological process. Prior research has noted that emotional attachment to the environment often stems from initial sensory impressions and becomes progressively deepened through cognitive and emotional processing [32,88]. This study empirically echoes such theories.

In summary, the two parts of this study are aligned under the framework of CAT, combining eye-tracking experiments with structural equation modeling to preliminarily construct a path—from visual preference formation to place attachment—among Gen Z tourists at sacred heritage sites, based on a Chinese sample. Study 1 found that although historical commemorative landscapes elicited the highest levels of visual attention (FC, TFD), they received the lowest subjective preference ratings. In contrast, natural sacred landscapes achieved the highest preference ratings with relatively lower visual search costs, suggesting that cognitive investment and preference are not necessarily positively correlated. Due to their salient sensory features, natural sacred landscapes demonstrated advantages in both initial attention capture and sustained visual processing, receiving the highest subjective preference scores. These findings indicate that Generation Z tourists exhibit perceptual affinity and visual preference for natural elements, challenging the stereotype that they primarily favor digital and technological experiences. Study 2 further demonstrated that the construction of place attachment in response to sacred landscapes is mediated by perceived novelty and awe. The moderating role of mindfulness further highlights that individual psychological traits significantly influence the emotional depth of heritage experiences, emphasizing the importance of matching visitors’ mental states in future tourism planning. Both studies to some extent suggest that Chinese Generation Z tourists’ emotional connections to place originate from the coupling of visual attraction, cognitive novelty, and emotional arousal in response to the environment.

6.3. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The theoretical implications are as follows: (1) This study focuses on Chinese Generation Z tourists, addressing the importance of generational differences in cultural heritage tourism and expanding the understanding of emotional place-bonding mechanisms in emerging generations. Additionally, by adopting a “sacred heritage” perspective, it enriches the typological dimensions of heritage research. (2) By integrating eye-tracking technology with moderated mediation questionnaire modeling in a mixed-methods paradigm, this study enhances the causal validity of its inferences beyond conventional single-measure survey approaches, promoting interdisciplinary integration between heritage science and environmental psychology. (3) This study incorporates both “perceived novelty” and “awe” as dual constructs in the formation of place attachment, and is the first to empirically verify their chained mediation effect, clarifying how cognitive appraisal and emotional response jointly shape tourists’ emotional connection to heritage landscapes. (4) By introducing the mindfulness level as a moderating variable, this research demonstrates that individual psychological traits influence the emotional processing intensity of sacred landscapes, offering a valuable addition to cognitive appraisal theory through the lens of individual differences.

From the perspective of heritage practice, CAT offers managers a practical framework to diagnose and enhance visitor experiences. It prompts managers to consider several key questions: During the primary appraisal stage, which specific elements of our heritage site (e.g., architecture, natural scenery, spatial features) are most likely to be perceived by Gen Z tourists as relevant, novel, or appealing in relation to their personal goals? In the secondary appraisal stage, what resources do we offer—such as interpretive systems, digital guides, or staff interactions—that assist tourists in understanding or coping with complex historical or spiritual meanings, thereby fostering positive emotional experiences rather than confusion or frustration? Addressing these questions is central to applying the CAT theory in guiding the revitalization and management of heritage sites. Specifically, this can be achieved by the following:

(1) Analyzing eye-tracking data, differences in visual attention and preference evaluations among various types of sacred landscapes were identified. These findings can inform the optimization of spatial circulation planning and visual focal point design, such as using natural elements as core visual guides to enhance first impressions of a site, or adjusting focal points, circulation flow, and composition proportions to reduce visual load, improve spatial order, and enhance visitors’ cognitive fluency. (2) Generation Z tends to favor novelty and emotional triggers. This study highlights the crucial role of awe in fostering place attachment, suggesting that heritage sites should reinforce symbolic, grand, or multisensory scenes—such as through light and shadow, sound, and storytelling—to enhance perceived sacredness and immersive experiences. (3) The study underscores the moderating effect of visitors’ mindfulness levels on emotional pathways. This suggests that targeted tourism product design can cultivate or activate a mindful state in visitors. For example, heritage destinations can promote the concept of “slow tourism” through initiatives like mindful hiking, meditation spaces, or tranquil garden designs to encourage immersive environmental experiences approached with focus, openness, and awareness.

6.4. Limitations

The limitations of this study are as follows: (1) This study primarily focuses on a sample of Chinese Generation Z university students. Due to the relatively homogeneous cultural and educational background of the participants, the findings may not fully represent the general characteristics of Gen Z in diverse cultural contexts, and instead reflect specific phenomena observed in this study. Future research could incorporate cross-cultural samples with diverse cultural backgrounds, educational levels, and travel experiences to enhance the external validity of the findings and broaden the theoretical framework. (2) The study employed static scene images, which may not fully replicate the atmosphere of real-life sacred sites. Future research could utilize technologies such as Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) to more accurately simulate complex environments and capture visitors’ psychological states more comprehensively. (3) Although the combination of eye-tracking and questionnaires effectively captured visual attention and subjective experience, it was insufficient in uncovering deeper neural processing mechanisms. Subsequent studies could integrate multimodal physiological techniques, such as electroencephalography (EEG), functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), or galvanic skin response (GSR), to obtain more timely and objective psychophysiological data and to deepen the multilayered understanding of the cognitive mechanisms behind “sacred experiences.”

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C.; data curation, Y.C. formal analysis, Y.C.; investigation, Y.C.; supervision, W.C.; visualization, Y.C.; writing—original draft, Y.C.; writing—review and editing, Y.C. and W.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Young Scientists Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42501290); the Key Research Project of the Sichuan Provincial Department of Culture and Tourism, (Grant No. 2024SYSYB05); the Social Science “14th Five-Year Plan” Fund Project of Jiangxi Province (2025) (Grant No. 25YS15).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University (TJ-CAUP20241120, approval date: 20 November 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, S.; Liang, J.; Su, X.; Chen, Y.; Wei, Q. Research on Global Cultural Heritage Tourism Based on Bibliometric Analysis. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. Tourism and Culture Synergies; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2018; ISBN 978-92-844-1897-8. [Google Scholar]

- Grand View Research. Heritage Tourism Market Size, Share & Trends Report. 2030. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/heritage-tourism-market-report (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Cai, Z.; Fang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, F. Joint Development of Cultural Heritage Protection and Tourism: The Case of Mount Lushan Cultural Landscape Heritage Site. Herit. Sci. 2018, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO Initiative on Heritage of Religious Interest. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/religious-sacred-heritage/ (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Isnaeni, H.; Muafiroh, S.; Ummah, Z.R.; Turner, S.; Lekakis, S.; Adianto, J.; Hermawan, R.; Iriyanto, N.; Kersapati, M.I.; Atqa, M. Sacred Places, Ritual and Identity: Shaping the Liminal Landscape of Banda Neira, Maluku Islands. Land 2025, 14, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivasciuc, I.-S.; Candrea, A.N.; Ispas, A. Exploring Tourism Experiences: The Vision of Generation Z Versus Artificial Intelligence. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, N.; Njuguna, M.; Dennis, K. Residents’ Visual Preference Dimensions of Historic Parklands in Nairobi, Kenya. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2022, 13, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katahenggam, N. Tourist Perceptions and Preferences of Authenticity in Heritage Tourism: Visual Comparative Study of George Town and Singapore. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2020, 18, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuuren, B.; Ormsby, A.; Jackson, W. How Might World Heritage Status Support the Protection of Sacred Natural Sites? An Analysis of Nomination Files, Management, and Governance Contexts. Land 2022, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, R.; Bell, J.; Book, A.; Fear, C.; Hinkin, O.; Hobbs, S.; Matravers, J.; Meggitt, J.; Phillips, N.; Ruhlig, V. Immersive Sacred Heritage: Enchantment through Authenticity at Glastonbury Abbey. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2025, 31, 857–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.; Stoffelen, A.; Bolderman, L.; Groote, P. Place Agency and Visitor Hybridity in Place-Making Processes at Sacred Heritage Sites. Tour. Geogr. 2025, 27, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristić, N.D.; Ćulafić, I.K. Sacred Networks and Spiritual Resilience: Sustainable Management of Studenica Monastery’s Cultural Landscape. Land 2025, 14, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Progano, R.N. Christian Pilgrimage Landscape and Heritage: Journeying to the Sacred. Tour. Geogr. 2021, 23, 1143–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Wang, G.; Zeng, B.-Y.; Li, S.-J.; Xiong, L.; Yang, H. Revealing the Pattern of Causality between Tourist Experience and the Perception of Sacredness at Shamanic Heritage Destinations in Northeast China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pricope Vancia, A.P.; Băltescu, C.A.; Brătucu, G.; Tecău, A.S.; Chițu, I.B.; Duguleană, L. Examining the Disruptive Potential of Generation Z Tourists on the Travel Industry in the Digital Age. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbe, D.; Neuburger, L. Generation Z and Digital Influencers in the Tourism Industry. In Generation Z Marketing and Management in Tourism and Hospitality: The Future of the Industry; Stylos, N., Rahimi, R., Okumus, B., Williams, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 167–192. ISBN 978-3-030-70695-1. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, C. Understanding the Relationship between Tourists’ Perceptions of the Authenticity of Traditional Village Cultural Landscapes and Behavioural Intentions, Mediated by Memorable Tourism Experiences and Place Attachment. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 28, 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Zheng, Z.; Tian, D.; Zhang, R.; Law, R.; Zhang, M. Resident-Tourist Value Co-Creation in the Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism Context: The Role of Residents’ Perception of Tourism Development and Emotional Solidarity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Zhang, J.; Zu, R.; Li, Y. Visual Perception Differences and Spatiotemporal Analysis in Commercialized Historic Streets Based on Mobile Eye Tracking: A Case Study in Nanchang Wanshou Palace, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusnak, M.; Szmigiel, M.; Geniusz, M.; Koszewicz, Z.; Magdziak-Tokłowicz, M. Exploring the Impact of Cultural Context on Eye-Tracking Studies of Architectural Monuments in Selected European Cities: Sustainable Heritage Management. J. Cult. Herit. 2024, 66, 326–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Wu, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Fang, H.; Deng, S. Tourists’ Visual Attention and Preference of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 29, 753–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place Attachment: How Far Have We Come in the Last 40 Years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, A.; Yuksel, F.; Bilim, Y. Destination Attachment: Effects on Customer Satisfaction and Cognitive, Affective and Conative Loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, L.; Weiss, J. Evidence on the Relationship between Place Attachment and Behavioral Intentions between 2010 and 2021: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Wei, W.; Ding, S.; Xue, J. The Relationship between Place Attachment and Tourist Loyalty: A Meta-Analysis. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 43, 100983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.D.T.; Brown, G.; Kim, A.K.J. Measuring Resident Place Attachment in a World Cultural Heritage Tourism Context: The Case of Hoi An (Vietnam). Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2059–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Marques, C.P.; Carneiro, M.J. Place Attachment through Sensory-Rich, Emotion-Generating Place Experiences in Rural Tourism. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 17, 100455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Emotion and Adaptation; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; ISBN 978-0-19-506994-5. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Li, S.; Fong, L.H.N.; Li, Y. When Intangible Cultural Heritage Meets Modernization—Can Chinese Opera with Modernized Elements Attract Young Festival-Goers? Tour. Manag. 2025, 107, 105036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.; Farahani, S.; Xie, Y.; He, X. Exploring the Psychological Restoration of Tourists in Natural and Cultural Destinations: The Moderating Roles of Novelty and Familiarity. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2025, 57, 101362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skavronskaya, L.; Moyle, B.; Scott, N. The Experience of Novelty and the Novelty of Experience. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitas, O.; Bastiaansen, M. Novelty: A Mechanism of Tourists’ Enjoyment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 72, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Chen, P.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, W. The Impact of the Creative Performance of Agricultural Heritage Systems on Tourists’ Cultural Identity: A Dual Perspective of Knowledge Transfer and Novelty Perception. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 968820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roseman, I.J. Appraisal in the Emotion System: Coherence in Strategies for Coping. Emot. Rev. 2013, 5, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltner, D.; Haidt, J. Approaching Awe, a Moral, Spiritual, and Aesthetic Emotion. Cogn. Emot. 2003, 17, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.Q.; Shen, H.J.; Ye, B.H.; Zhou, L. From Axe to Awe: Assessing the Co-Effects of Awe and Authenticity on Industrial Heritage Tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 2821–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, R.B.; Brownlee, M.T.J.; Kellert, S.R.; Ham, S.H. From Awe to Satisfaction: Immediate Affective Responses to the Antarctic Tourism Experience. Polar Rec. 2012, 48, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Huang, Y. Awe of Intangible Cultural Heritage: The Perspective of ICH Tourists. Sage Open 2020, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darbor, K.E.; Lench, H.C.; Davis, W.E.; Hicks, J.A. Experiencing versus Contemplating: Language Use during Descriptions of Awe and Wonder. Cogn. Emot. 2016, 30, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eck, T.; Zhang, Y.; An, S. A Study on the Effect of Authenticity on Heritage Tourists’ Mindful Tourism Experience: The Case of the Forbidden City. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.G.; Romate, J.; Rajkumar, E. Mindfulness-Based Positive Psychology Interventions: A Systematic Review. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Eck, T.; Woosnam, K.M.; Jiang, L. Applying Mindfulness Theory to Enhance Voluntourism Experiences. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2024, 50, 101203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiken, L.G.; Lundberg, K.B.; Fredrickson, B.L. Being Present and Enjoying It: Dispositional Mindfulness and Savoring the Moment Are Distinct, Interactive Predictors of Positive Emotions and Psychological Health. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 1280–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, S.R.; Lau, M.; Shapiro, S.; Carlson, L.; Anderson, N.D.; Carmody, J.; Segal, Z.V.; Abbey, S.; Speca, M.; Velting, D.; et al. Mindfulness: A Proposed Operational Definition. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2004, 11, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M. Integrative Emotion Regulation: Process and Development from a Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Dev. Psychopathol. 2019, 31, 945–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, D.; Sun, R.; Zhu, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, R.; Qin, S. Language Styles, Recovery Strategies and Users’ Willingness to Forgive in Generative Artificial Intelligence Service Recovery: A Mixed Study. Systems 2024, 12, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishchenko, O.V. Classification Scheme of Sacred Landscapes. Eur. J. Geogr. 2018, 9, 62–74. [Google Scholar]

- Liutikas, D. Sacred Space in Geography: Religious Buildings and Monuments. In Geography of World Pilgrimages: Social, Cultural and Territorial Perspectives; Lopez, L., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 77–112. ISBN 978-3-031-32209-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J.Y. Landscape Visual Evaluation and Place Attachment in Historical and Cultural Districts: A Study Based on Semantic Differential Scale and Eye Tracking Experimental Methods. Multimed. Syst. 2024, 30, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, K.; Li, J.; Hao, T.; Zhou, Z. Comparative Study of Cognitive Differences in Rural Landscapes Based on Eye Movement Experiments. Land 2024, 13, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Hou, G.; Xiao, X. Research on the Preference of Public Art Design in Urban Landscapes: Evidence from an Event-Related Potential Study. Land 2023, 12, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, P.; Li, L.; Liu, J. The Influence of Architectural Heritage and Tourists’ Positive Emotions on Behavioral Intentions Using Eye-Tracking Study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Ritchie, J.R.B.; McCormick, B. Development of a Scale to Measure Memorable Tourism Experiences. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, A.; Buckley, R.; Weaver, D. A Framework for Analysing Awe in Tourism Experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1710–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, M.A.; Bishop, S.R.; Segal, Z.V.; Buis, T.; Anderson, N.D.; Carlson, L.; Shapiro, S.; Carmody, J.; Abbey, S.; Devins, G. The Toronto Mindfulness Scale: Development and Validation. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 62, 1445–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S.-H. The Impacts of the Dual Path of Awe on Volunteer Tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2025, 63, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The Measurement of Place Attachment: Validity and Generalizability of a Psychometric Approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-60918-230-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Ruan, R.; Deng, W.; Gao, J. The Effect of Visual Attention Process and Thinking Styles on Environmental Aesthetic Preference: An Eye-Tracking Study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1027742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Lin, Y.; Chen, L. Exploring Destination Choice Intention by Using the Tourism Photographic: From the Perspectives of Visual Esthetic Processing. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 713739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, B.A.; Wang, Y. Natural and Built Photographic Images: Preference, Complexity, and Recall. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 868–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. View Through a Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samson, M.G.M.; Leichty, J.G. Images of the Urban Religious Landscape: Gen Z Seek out the Sacred in the City. J. Cult. Geogr. 2022, 39, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, R.; Schwarz, N.; Winkielman, P. Processing Fluency and Aesthetic Pleasure: Is Beauty in the Perceiver’s Processing Experience? Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 8, 364–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhu, F.; Li, J. Research on a Quantification Model of Online Learning Cognitive Load Based on Eye-Tracking Technology. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2025, 84, 18993–19007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Shan, Q.; Chen, L.; Liao, S.; Li, J.; Ren, G. Survey on the Impact of Historical Museum Exhibition Forms on Visitors’ Perceptions Based on Eye-Tracking. Buildings 2024, 14, 3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole-Jones, K. Historical Memory, Reconciliation, and the Shaping of the Postbellum Landscape: The Civil War Monuments of Forest Park, St. Louis. Panorama 2020, 6, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautamaki, R.; Laine, S. Heritage of the Finnish Civil War Monuments in Tampere. Landsc. Res. 2020, 45, 742–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. The Museum Experience Revisited; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-315-41785-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, S.; Hou, R.; Zhang, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C. Visual Behavior Characteristics of Historical Landscapes Based on Eye-Tracking Technology. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 24, 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Hou, W. Research on Interface Complexity and Operator Fatigue in Visual Search Task. In Engineering Psychology and Cognitive Ergonomics; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoki, K.; Saito, T.; Onuma, T. Eye-Tracking Research on Sensory and Consumer Science: A Review, Pitfalls and Future Directions. Food Res. Int. 2021, 145, 110389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, A.; Rutherford, P.; McGraw, P.; Ledgeway, T.; Altomonte, S. Gaze Correlates of View Preference: Comparing Natural and Urban Scenes. Light. Res. Technol. 2022, 54, 576–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojsavljević, R.; Vujičić, M.D.; Stankov, U.; Stamenković, I.; Masliković, D.; Carmer, A.B.; Polić, D.; Mujkić, D.; Bajić, M. In Search for Meaning? Modelling Generation Z Spiritual Travel Motivation Scale—The Case of Serbia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachyuni, S.S.; Wahyuni, N.; Wiweka, K. What Motivates Generation Z to Travel Independently? Preliminary Research of Solo Travellers. J. Tour. Econ. 2023, 6, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R.; Wilson, E.O. The Biophilia Hypothesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]