Abstract

The color design of architectural interior display spaces directly affects the effectiveness of cultural information communication and the visual cognitive experience of viewers. However, there is currently a lack of combined subjective and objective evaluation regarding how to scientifically translate and apply traditional color systems in modern contexts. This study takes the virtual display space of traditional Chinese floral arrangements as a case, aiming to construct an evaluation framework integrating the Semantic Differential Method and eye-tracking technology, to empirically examine how color schemes based on the translation of traditional aesthetics affect the subjective perception and objective visual attention behavior of modern viewers. Firstly, colors were extracted and translated from Song Dynasty paintings and literature, constructing five sets of culturally representative color combination samples, which were then applied to standardized virtual exhibition booths. Eye tracking data of 49 participants during free viewing were recorded via an eye-tracker, and their subjective ratings on four dimensions—cultural color atmosphere perception, color matching comfort level, artwork form clarity, and explanatory text clarity—were collected. Data analysis comprehensively employed linear mixed models, non-parametric tests, and Spearman’s rank correlation analysis. The results show that, regarding subjective perception, different color schemes exhibited significant differences in traditional feel, comfort, and text clarity, with Sample 4 and Sample 5 performing better on multiple indicators; a moderate-strength, significant positive correlation was found between traditional cultural atmosphere perception and color matching comfort. Regarding objective eye-tracking behavior, color significantly influenced the overall visual engagement duration and the processing depth of the text area. Among them, the color scheme of Sample 5 better promoted sustained reading of auxiliary textual information, while the total fixation duration obtained for Sample 4 was significantly shorter than that of other schemes. No direct correlation was found between subjective ratings and spontaneous eye-tracking behavior under the experimental conditions of this study; the depth of processing textual information was a key factor driving overall visual engagement. The research provides empirical evidence and design insights for the scientific application of color in spaces such as cultural heritage displays to optimize visual experience.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Significance

Indoor cultural display spaces, as important venues in contemporary social life, carry the significant functions of cultural dissemination and information exchange. In such spaces, environmental color goes beyond mere decorative function, deeply participating in the shaping of cultural atmosphere and the guidance of audience attention [1,2]. Traditional floral arrangement is an important Intangible Cultural Heritage of China, encompassing not only exquisite traditional floral arrangement skills but also representing the Chinese characteristic concept of garden living, making it a significant display object in Chinese indoor cultural display spaces. Compared to general exhibitions, such spaces need to accurately convey their profound historical and cultural heritage while meeting modern exhibition needs. How to scientifically employ the language of color to construct a display environment that can both evoke historical memory and conform to contemporary visual cognition laws has become a practical challenge faced in realizing the “living inheritance” of traditional culture [3].

Against this background, this study focuses on the display space of traditional Chinese floral arrangements, aiming to explore the mechanism of how specific color schemes function in the visual cognitive process. It seeks to provide empirical evidence and theoretical reference for the display design of related cultural heritage, thereby assisting in the more effective realization of cultural inheritance and dissemination in the contemporary context.

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. Spatial Environmental Color Design

Environmental color has long been viewed as a background or decorative element. However, contemporary design research for indoor cultural display spaces has repositioned it as a strategic medium, a key variable that carries complex cultural significance and profoundly influences audience psychology and cognition [4]. The scientific evaluation of environmental color in cultural display spaces, and understanding its mechanism of action, requires a shift from a unidirectional aesthetic scrutiny to an exploration of the processes of “meaning production” and “information processing.” Based on this, this paper integrates two theoretical perspectives—Semiotics and Cognitive Load Theory—reviews recent related research, and constructs an intersecting analytical framework centered on “meaning encoding-cognitive processing-experience output” under these theories.

From the dimension of Semiotic theory, environmental color is a constructed cultural symbol. In display spaces, it first operates as a visual sign, its meaning rooted in socio-cultural constraints and specific curatorial narratives. Recent research findings indicate that the individual’s association between “color” and “emotion” can confirm that color choice is one way to construct and reinforce cultural identity. For example, the cultural metaphorical function of color can directly evoke cultural identity and historical context [5]; distinctly different display environmental colors can be used to demarcate spatial zones of different dynasties or civilizations, strengthening the cognition of spatiotemporal transformation [6]; through measurement studies, certain colors can be used to metaphorize regional culture in specialized exhibition tasks for specific areas, enhancing exhibition appeal [7].

Analyzing from the perspective of Cognitive Load Theory, when audiences engage in visual exploration and cognitive activities within information-dense cultural display spaces, environmental color design directly affects the allocation and efficiency of cognitive resources [8]. Recent research shows that the color design of architectural cultural display spaces is a key variable guiding audience cognitive effects. First, multiple research findings confirm that environmental color can effectively manage cognitive load and attract audience attention. For instance, using color to guide visitor flow is more intuitive and imposes lower cognitive load than pure text or graphic signage. Placing key exhibits against a contrasting color background can significantly increase viewers’ visual attention and memory retention [9]. Second, several studies indicate that adopting a color scheme harmonized with the theme can guide audiences into deep information processing and optimize germane load by triggering emotional resonance and semantic association. For example, two experiments both demonstrated that ancillary colors are more effective than simple shapes in driving historical memory [10]. Third, multiple studies point out that the hierarchical design of environmental color can purposefully organize complex visual information. For example, using different colors to distinguish cognitive aids such as thematic explanations and exhibit labels around exhibits helps audiences quickly establish information classification schemas, reducing extraneous cognitive load formed during information search [11], which primarily stems from the brain’s nervous system’s ability for rapid classification processing of color. Finally, environmental color design in cultural display spaces also needs to be cautious of inducing visual cognitive fatigue to maintain viewing effectiveness [12].

Although research on environmental color design in indoor cultural display spaces has made some progress in Semiotics and Cognitive Load Theory, respectively, a trend towards increasingly specialized research content in recent years has resulted in less exploration of multi-task interaction and systematization, especially regarding application methods for traditional colors in the indoor cultural display spaces of architecture.

1.2.2. Spatial Environmental Color Application Evaluation

Based on the research framework of “meaning encoding-cognitive processing-experience output,” the evaluation of environmental color in cultural display spaces should be conducted from two dimensions: color psychological perception and cognitive load. Evaluating color psychological perception aims to explore how the selection and matching of spatial environmental colors elicit emotions and meaning associations related to cultural context; evaluating color cognitive load focuses on whether the selection and matching of spatial environmental colors aid in achieving effective information cognition. According to current research, both primarily employ measurement and evaluation methods combined with controlled experiments.

The measurement of cultural psychological perception of spatial environmental color relies mainly on subjective evaluation methods. Measurement tools include standardized scales or custom cultural association questionnaires, with the Semantic Differential Method being a typical representative. This method quantifies abstract, multidimensional psychological feelings into measurable data by using semantic scales for rating, effectively capturing users’ subjective emotions and cognitive evaluations. However, its results are susceptible to interference from subjective factors such as social desirability and individual interpretation differences [13]. In research on the cognitive load of spatial environmental color, technical means primarily involve using eye-tracker devices to record participants’ eye movement trajectories while viewing visual stimuli, collecting data such as fixation points, fixation durations, and saccade paths. This method can reveal unconscious visual attention allocation patterns and information processing processes non-invasively and precisely, providing direct objective evidence for understanding how color guides visual exploration and attracts attention [14,15,16,17]. However, human subjective consciousness is complex, and eye movement behavior characteristics produced by different subjective emotions often overlap. In recent years, research methods have also begun to include multi-task [18] and interactive mode measurement methods [19] to address the shortcomings in systematic research and pattern measurement.

1.2.3. Spatial and Cultural Translation of Traditional Colors

The spatial and cultural translation of traditional colors refers to extracting these colors from their original carriers and re-contextualizing them within new spatial settings, using color as a medium to evoke historical associations in the audience [20].

Based on existing research, the original carriers of traditional colors are typically categorized into two types: “documentary archives” and “material relics.” Basing the process on “documentary archives” involves utilizing color records found in historical documents, such as the Song Dynasty’s Yingzao Fashi and the Qing Dynasty’s Neiwufu Zaobanchu Huoji Dang, to verify or study the names and quantities of pigments used in the official architectural paintings of those dynasties, ultimately determining the colors [21,22]. Basing it on “material relics” involves analyzing and extracting colors from existing cultural artifacts. Examples include sampling colors from timed images of historical buildings, using the Munsell Color System and referencing standard color charts to determine the colors [23]; for historical paintings, precise color determination can be achieved through experimental analysis of the pigments [24]. However, some “material relics” of high historical value and from long-enduring historical periods, due to being under a high level of protection, can only be accessed through digital reproductions. In such cases, it is necessary to combine multiple lines of evidence, including documentary archives and existing research findings, to verify the authenticity of the image information.

1.3. Research Objectives

The core research question of this study is how traditional colors, after modern translation, influence the subjective perception and objective visual attention behavior of viewers in cultural display spaces through their visual attributes, and what internal relationships exist between the various subjective and objective evaluation dimensions. By constructing a combined analysis framework integrating the Semantic Differential Method and eye-tracking technology to investigate how different traditional color schemes affect users’ environmental perception, information recognition, and other visual behaviors in modern cultural display spaces. Taking the virtual display space of Traditional Chinese Floral Arrangements as an empirical case study, the specific objectives and research hypotheses of this research are as follows:

- (1)

- To propose a method for extracting and modernly translating traditional cultural colors based on historical images and documentary materials.

Hypothesis 1.

Based on Song Dynasty paintings and literature, at least one extracted color scheme will have a significantly higher score on the traditional cultural atmosphere dimension than other schemes.

- (2)

- To construct a multi-factor evaluation framework for display space colors that integrates subjective Semantic Differential evaluations and objective eye-tracking data.

Hypothesis 2.

Different color schemes exhibit significant differences across different subjective perception dimensions.

Hypothesis 3.

Different color schemes exhibit significant differences across different eye-tracking metrics.

- (3)

- To quantitatively analyze the differences between different color schemes across perception dimensions and explore the correlations between the metrics.

Hypothesis 4.

Significant correlations exist among the various subjective perception metrics.

Hypothesis 5.

Significant correlations exist among the various objective eye-tracking metrics.

Hypothesis 6.

Significant correlations exist between subjective perception scores and eye-tracking behavior metrics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Technical Route

The research is divided into three parts: experimental material preparation, data collection, and data analysis, systematically investigating the visual perception effects of traditional Chinese color schemes in the virtual display space of floral arrangements. The technical route is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Technology roadmap.

First, experimental material preparation was conducted. Based on Song Dynasty paintings and literature, traditional colors were extracted and translated to construct 5 culturally representative color samples from five flower arrangement application scenarios, which were subsequently applied to a unified virtual display booth model to synthesize the visual stimulus materials required for the experiment. Second, data collection was carried out. Participants were recruited to observe virtual display booth images sequentially through an eye-tracker in a controlled experimental environment, and their eye movement data were simultaneously recorded. Immediately after observation, they filled out the Semantic Differential questionnaire to collect subjective perception evaluation data. Finally, data analysis was performed. Descriptive and inferential statistics were applied to the subjective questionnaire scores and objective eye-tracking metrics, respectively, and non-parametric correlation was used to explore the relationships between different dimensions of color perception.

2.2. Virtual Display Space Color Design

2.2.1. Color Extraction and Matching

Traditional Floral Arrangement, recognized as a National-level Intangible Cultural Heritage of China, reached its peak of development during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 AD). It thus provides an ideal case for exploring the aforementioned issues. The Song Dynasty not only achieved excellence in floral art, but its paintings and literature depicting architectural environments such as palace halls, studies, and gardens have also preserved extremely rich and systematic examples of color application [25]. This makes it possible to extract representative architectural ambient colors from Song Dynasty visual materials and test their feasibility for application in contemporary display spaces.

To create a specific cultural atmosphere for the Song Dynasty floral arrangement display space, the environmental types where floral arrangements are placed in Song Dynasty paintings were categorized, the constituent elements of floral application scenes were distinguished, and the colors of Song Dynasty floral application environments were extracted as display space color samples by combining Song Dynasty color records and contemporary color restoration literature. The specific steps are as follows.

Within the scope of Song Dynasty paintings included in ‘the Complete Collection of Song Paintings’ [26], 40 clear Song Dynasty image samples depicting container floral arrangements and their application environments were selected based on image clarity and content relevance. Their application environment backgrounds were summarized and categorized into three types: outdoor natural environments, high-status royal palace halls, and lower-status scholars’ studies and pavilions. Some image examples are shown in Table 1. Based on the area ratio of the constituent elements in the application environment within the images, the dominant and accent colors for the display space were distinguished. When the background was a natural environment, the sky color served as the dominant color, and the vegetation color as the accent. For royal palace halls, the wall decoration color was the dominant color, and the column body color the accent. For scholars’ studies and pavilion buildings, the door/window woodwork decoration color was the dominant color, and the color of materials covering the door/window grilles, such as paper or silk, served as the accent.

Table 1.

Summarize the environmental categories and constituent elements of flower arrangement application in Song Dynasty paintings.

Then, based on the descriptions of Song Dynasty architectural colors in the officially published specification Yingzao Fashi, which regulated the styles and colors of buildings of different ranks at the time, and the restoration conclusions of traditional colors in related literature, specific colors were extracted to form five combinations of dominant and accent colors.

The extraction process for each sample color is as follows. As natural elements lack an accurate color description basis, under good weather conditions, a Sony high-definition digital camera A6400 (Sony Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was used to photograph the Beijing summer noon sky and plants, and sky blue and medium green were extracted to construct Sample 1. According to the national architectural code of the Song Dynasty, the Yingzao Fashi, the wall polychrome colors involved applying four different colored limes onto walls, resulting in earth red, gray, light yellow, and white on the plastered surface. Among these, the red-gray surface layer was the main form for imperial palace and pavilion walls, with a color described as brightly colored earth red [27]. Columns belong to the large woodwork of palace and pavilion buildings, and their polychrome decoration styles mainly had three forms. Among them, the “Wucai Bianzhuang” style used vermilion as the base color for columns with blue and green patterns; the “Nianyu Zhuang” and “Qinglv Dieyun Lengjian Zhuang” styles both used green as the base with blue patterns [27]. As the human eye finds it difficult to distinguish the color difference between the “brightly colored earth red” used on walls and the “vermilion” used on columns, the red sampled for this study’s palace/pavilion interior was based on vermilion. Thus, the color combinations “vermilion-green” and “vermilion-blue” were obtained, forming Sample 2 and Sample 3. The doors and windows of scholars’ studies and pavilions belong to small woodwork. Song Dynasty architectural small woodwork polychrome decoration often used “Tuzhu Shua” and “Hezhu Shua” [28]. “Tuzhu Shua” is an earth red brush finish, and its visual difference from “Hezhu Shua” is minimal; therefore, earth red was sampled for this study. The Song Dynasty widely used paper as door/window coverings. The Northern Song poet Guo Zhen described window paper as “white like stream clouds, thin like ice”; sometimes grass curtains were also used to cover doors/windows on pavilions. Based on this, “earth red-white” and “earth red-yellow” were used as Sample 4 and Sample 5.

After determining the color names for the floral arrangement environment’s constituent elements, the specific color values were referenced to the color chart in the book ‘Yingzao Fashi Caihua Yanjiu’ [21]. The CMYK values from the color chart were converted to RGB values for sample construction using formulas. Red (R) is calculated from Cyan (C) and Black (K), Green (G) from Magenta (M) and Black (K), and Blue (B) from Yellow (Y) and Black (K). The formulas are as follows.

R = 255 × (1 − C) × (1 − K)

G = 255 × (1 − M) × (1 − K)

B = 255 × (1 − Y) × (1 − K)

Considering the goal of serving color scheme translation and design application, the HSB color model, widely used in the design industry, was chosen for color quantification. In Adobe Photoshop (version 2021; Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA), the eyedropper tool was used to quantify the RGB values into HSB values for subsequent discussion and analysis. H (hues) represents the hue attribute, indicated by a numerical value on the hue circle; S (saturation) represents the purity attribute, indicated by a numerical value of gray content; B (brightness) represents the lightness attribute, indicated by a numerical value of white content [29]. The quantification results of the color samples are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Color quantification principles and color sample matching and quantification. (a) Principle of RGB attribute quantification. (b) Principle of HSB attribute quantification. (c) Quantitative results of color samples. Since the maximum difference on a hue circle is 180°, when the calculated value is greater than 180, the final is calculated as . The five dominant-accent color combinations (S1–S5) derived from Song Dynasty aesthetics that were tested. S1 (Sky Blue + Medium Green) represents the natural environment. S2 (Vermilion + Blue) and S3 (Vermilion + Green) are based on imperial palace color schemes. S4 (Earth Red + White) and S5 (Earth Red + Light Yellow) represent scholar’s studio settings.

2.2.2. Virtual Display Space Design

This study employs virtual exhibition booths as experimental materials, aiming to construct a standardized, controllable visual evaluation environment. Each virtual booth consists of three main elements: floral arrangement artworks, a solid-color background panel, and text descriptions, forming a complete visual information unit for systematically investigating the impact of color schemes.

To ensure the cultural consistency and comparability of the experimental materials, the images of one large and one small Song Dynasty-style floral arrangement work used in this study were both photographed from the same booth at the 2019 Beijing International Horticultural Exhibition, China Floral Art Exhibition. This exhibition was organized by the China Traditional Floral Art Association, and the exhibits were created by a team of national-level inheritors and floral art masters, ensuring a high degree of homogeneity in artistic style and cultural connotation. Image capture used a Sony high-definition digital camera A6400, shot from a human eye-level perspective to ensure visual perspective authenticity.

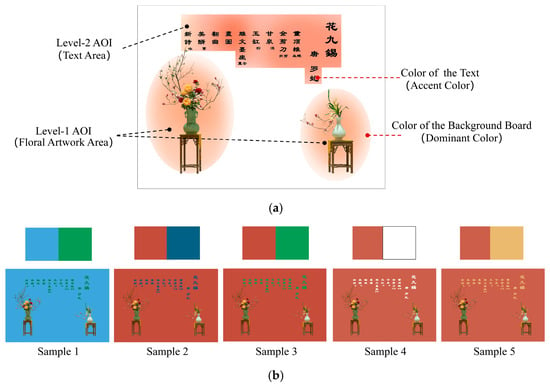

In the layout, the large and small floral arrangement works are placed side-by-side and jointly defined as the Level-1 Area of Interest (AOI); the text description area is independently defined as the Level-2 AOI. Introducing the second floral arrangement work provides an additional natural visual anchor point, avoiding the convergence of visual response patterns that a single focal point might cause. Treating the two floral arrangement works as a single integrated AOI aims to simulate the overall process in real viewing where the line of sight wanders and converges among multiple related exhibits.

The dominant color defined in the previous section serves as the background panel color, and the accent color serves as the text color. By applying different dominant-accent color combinations to a booth template composed of identical visual elements, five sets of experimental images were ultimately synthesized, as shown in Figure 3. The virtual booth samples (Figure 3) feature classical Chinese text to preserve cultural authenticity. The text is an excerpt from Hua Jiu Xi (《花九锡》, The Nine Imperial Honors for Flowers), a seminal treatise on floral art by Luo Qiu of the Tang Dynasty. It outlines nine ceremonial principles for appreciating flowers, which have profoundly influenced East Asian floral aesthetics. The text translates as follows: “花九锡 (Hua Jiu Xi): The Nine Imperial Honors for Flowers”. The honors are: 1. 重顶帷 (Chong Ding Wei): A double-layered canopy (to block the wind); 2. 金剪刀 (Jin Jian Dao): Golden scissors (for cutting); 3. 甘泉 (Gan Quan): Sweet spring water (for immersion); 4. 玉缸 (Yu Gang): A jade vase (for containing); 5. 雕文台座 (Diao Wen Tai Zuo): A carved pedestal (for placement); 6. 画图 (Hua Tu): Painting (i.e., the flower should be worthy of being painted); 7. 翻曲 (Fan Qu): Composing a song (in its honor); 8. 美醑 (Mei Xu): Fine wine (for appreciation); 9. 新诗 (Xin Shi): A new poem (to be recited in its praise). The inclusion of this text is crucial as it defines the rigorous aesthetic and ritual standards that form the cultural context of our study on Song Dynasty-style floral arrangement display. This process ensured strict and consistent control over all other visual elements and compositional factors, except for the color variables.

Figure 3.

Interest area setting and samples composed of different colors in virtual booth images. The text translates as follows: “花九锡 (Hua Jiu Xi): The Nine Imperial Honors for Flowers”. The honors are: 1. 重顶帷 (Chong Ding Wei): A double-layered canopy (to block the wind); 2. 金剪刀 (Jin Jian Dao): Golden scissors (for cutting); 3. 甘泉 (Gan Quan): Sweet spring water (for immersion); 4. 玉缸 (Yu Gang): A jade vase (for containing); 5. 雕文台座 (Diao Wen Tai Zuo): A carved pedestal (for placement); 6. 画图 (Hua Tu): Painting (i.e., the flower should be worthy of being painted); 7. 翻曲 (Fan Qu): Composing a song (in its honor); 8. 美醑 (Mei Xu): Fine wine (for appreciation); 9. 新诗 (Xin Shi): A new poem (to be recited in its praise). (a) An example of the virtual floral display space stimulus, illustrating the definition of Level-1 (Floral Artwork) and Level-2 (Text) Areas of Interest (AOIs). (b) The five dominant-accent color combinations (S1–S5) derived from Song Dynasty aesthetics that were tested. S1 (Sky Blue + Medium Green) represents the natural environment. S2 (Vermilion + Blue) and S3 (Vermilion + Green) are based on imperial palace color schemes. S4 (Earth Red + White) and S5 (Earth Red + Light Yellow) represent scholar’s studio settings.

2.3. Combined Semantic Differential Method and Eye-Tracking Analysis Method

2.3.1. Semantic Differential Evaluation System Establishment

The design of display spaces should enable viewers to clearly perceive the works while obtaining a comfortable visual experience and sensing the thematic atmosphere of the exhibition. As shown in Table 2, this Semantic Differential Method evaluation established 4 indicators centered around three dimensions of color in the floral arrangement display space: “cultural atmosphere perception,” “visual clarity,” and “visual comfort.” Adjective pairs were defined at both ends of the semantic scale for each indicator, and 5 measurement levels were set using the Likert scale. Among these, the Traditional Cultural Atmosphere indicator evaluates whether the color scheme can evoke associations with Chinese traditional culture and the Song Dynasty environment; the Color Matching Comfort indicator evaluates the degree of visual comfort perceived from the overall color scheme of the space; the Work Form Clarity indicator evaluates the clarity of the display of morphological details of the floral arrangement work; the Explanatory Text Clarity indicator evaluates the degree of visual legibility of the text on the background panel.

Table 2.

Semantic Differential evaluation system.

2.3.2. Eye-Tracking Metrics Selection

To acquire effective information, eye movement during viewing includes two processes: information searching and information processing [30]. The effective information in a floral arrangement exhibition primarily resides in two main visual information areas, the artwork area and the explanatory text area, i.e., the Areas of Interest (AOI). This eye-tracking study only recorded eye movement characteristics within these AOIs, with the floral artwork area denoted as Level-1 AOI and the explanatory text area as Level-2 AOI. As shown in Table 3, “Searching” is the process where the eyes scan the display booth to capture effective information, quantified by the time taken for the eyes to first enter an AOI. A shorter time indicates a more conspicuous AOI and higher search efficiency, measured by the metrics: Time to First Entry into Level-1 AOI and Time to First Entry into Level-2 AOI. “Processing” refers to the internal cognitive process occurring while the eyes are fixated on the effective information area, measured by the duration of fixation on the AOI. A longer duration suggests the AOI is more effective at conveying information and more conducive to cognitive processing, measured by the metrics: Fixation Duration on Level-1 AOI, Fixation Duration on Level-2 AOI, and Total Fixation Duration on AOIs.

Table 3.

Descriptions of eye-tracking metrics.

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Participant Recruitment

To ensure this study possessed sufficient statistical power to detect true effects and avoid Type II errors, a priori sample size estimation was conducted using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7; Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany). For the core analysis of this study, which is to compare the differences among the five color samples on subjective perception questionnaire scores and eye-tracking metrics, a repeated-measures ANOVA (F test) was used for power analysis. The parameters were set as follows: a medium effect size of 0.2, a significance level (α) of 0.050, a desired statistical power (1–β) of 0.95, number of groups as 1, number of measurements as 5, and an assumed correlation among repeated measures of 0.5. The analysis result indicated that a total sample size of 48 was required to meet the above criteria. To examine the correlation between eye-tracking metrics and questionnaire scores, a point biserial correlation model (t test) was used for power analysis. The parameters were set as follows: a medium effect size |ρ| of 0.4, a significance level (α) of 0.050, a statistical power (1–β) of 0.80, and a two-tailed test was selected. The analysis result showed that a total sample size of 44 was required to meet the standards.

Integrating the above two analyses, and to ensure this study could effectively detect both between-group differences and examine correlations among variables, the larger sample size from the two analyses was adopted. This study initially recruited 52 participants. Finally, data from 3 participants were excluded due to an inability to pass calibration or excessively low eye-tracking data sampling rates.

The remaining participants totaled 49, all from Beijing Forestry University, comprising 9 males and 40 females, aged between 17 and 42 years (mean age = 21.43, SD = 4.605), with education levels at undergraduate or above. Twenty participants had backgrounds in color cognition or floral arrangement knowledge, while 29 were non-professionals. All were Chinese nationals. They all had a certain level of familiarity with the traditional style of the Song Dynasty, meaning they had previously viewed images or videos related to the Song period. All participants had no visual impairments, with normal or corrected-to-normal binocular visual acuity (equivalent to Snellen 20/20 or LogMAR 0.0), no strabismus, color blindness, or color deficiency, and were right-handed. Participants were instructed to get adequate rest the day before the experiment, avoiding fatigue, stress, or alcohol consumption. Before the experiment began, participants were informed that their experimental data would be recorded and analyzed for scientific research purposes, and all data would be anonymized. All participants voluntarily took part in the experiment, signed written informed consent forms, and received 10 Chinese Yuan or a gift as compensation for their time.

2.4.2. Experimental Environment and Apparatus

To minimize the influence of irrelevant environmental factors on participants’ perception, the experiment was conducted in an 80 m2 windowless classroom. External light sources were completely blocked throughout the session, and all potential interfering factors such as light, tactile sensations, noise, and odors were minimized. A single experimental station was set up in the classroom. The desktop maintained an average illuminance of ≥300 lux with a uniformity of ≥0.7. The lighting system used LEDs with a correlated color temperature of 6500 K to ensure uniform color perception.

The apparatus used in the experiment was the Tobii Pro Glasses 2 wearable eye-tracker (sampling rate: 100 Hz, accuracy ≤ 0.5°; Tobii AB, Stockholm, Sweden). Calibration was performed using Tobii Pro Glasses Controller software (version 1.95.14258; Tobii AB, Stockholm, Sweden) with a 1-point calibration procedure. The device automatically performs parallax correction and slip compensation based on a 3D eye model, allowing the experiment to proceed in a more natural setting without head fixation, thereby ensuring the validity of the results. Stimulus images were displayed on a 24-inch DELL P2424HT monitor (Dell Technologies Inc., Round Rock, TX, USA) with a screen resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixels and a refresh rate of 60 Hz. The presentation sequence and timing of the stimuli were controlled by Tobii Pro Lab software (version 25.19.1133; Tobii AB, Stockholm, Sweden). The eye-tracking data recorded while participants viewed different scenes was stored on the eye-tracker’s SD card and later imported into Tobii Pro Lab software for data analysis.

To accurately present the color stimuli and ensure consistency across all participant trials and for future study replication, the display monitor was color-calibrated prior to the experiment. An X-Rite i1 Display PRO (X-Rite, Incorporated, Grand Rapids, MI, USA) colorimeter coupled with calibrite ccProfiler V1.1.2 (calibrite GmbH, Eningen, Germany) software was used for color calibration. The settings were: white point set to CIE illuminant D65, luminance set to 120 cd/m2, with the option to adjust the profile based on ambient lighting selected. The ICC profile generated by the software was then applied.

2.4.3. Experimental Procedure

Prior to the formal experiment, a pilot test involving 3 researchers was conducted to verify the feasibility of the experimental materials and the suitability of the participants. The results confirmed that all pilot participants could understand the information conveyed by the color samples and possessed the physical capability to complete the experiment. The pilot test was also used to optimize experimental parameters, such as adjusting the stimulus sequence and inter-stimulus intervals, to mitigate fatigue effects.

At the start of the formal experiment, participants entered the experimental station one by one. The researcher explained the experiment’s objectives, procedures, and precautions in detail. The introduction included a welcome message, an overview of the experimental materials, and the task requirements. After participants confirmed their understanding, they signed the informed consent form. Participants were then asked to wear the eye-tracker and perform a 1-point calibration by looking at the accompanying calibration card placed 1 m away at eye level, ensuring the eye-tracker’s tracking error was below 0.5°. The formal task commenced only after successful calibration. If calibration failed, adjustments were made, and the procedure was repeated until the standard was met.

Before the stimulus images were displayed, participants were instructed to observe the images appearing on the screen carefully, as if viewing an exhibition, while avoiding excessive head movement. Participants were seated 600 to 650 mm from the center of the monitor. Each color sample image was displayed for a preset duration of 15 s, with a 5 s black screen interval between consecutive images. The images were presented in a randomized order to control for order effects. This process was repeated until all 5 images had been presented. The eye-tracking session lasted approximately 5 min. After completion, participants filled out a post-test questionnaire, which collected demographic information (gender, age, education level, professional background) and subjective perception data, with no time limit.

2.5. Data Analysis

Fixation durations and time to first fixation were exported from Tobii Pro Lab (Tobii AB, Stockholm, Sweden) software after filtering and preprocessing. During the preprocessing stage, because a wearable eye-tracker was used without head fixation, the Tobii I-VT (Attention) classifier was employed to filter raw gaze point data and identify events. The velocity threshold filter was set to 100°/s to distinguish between fixations and saccades. To optimize fixation event identification, adjacent fixation merging rules were applied, with a maximum time interval of 75 milliseconds and a maximum angle of 0.5 degrees. Short fixation removal was enabled, reclassifying fixations with durations below 60 milliseconds as saccades. This aimed to ensure effective identification of stable fixations while reducing data noise and preserving valid micro-saccade information. Subsequently, after defining the two AOIs in the software, the corresponding eye-tracking data for each color sample was exported. Questionnaire data were manually entered into Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) by the researchers. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (version 27.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the nine subjective and objective metrics for the five different stimulus images, calculating means and standard deviations to provide a preliminary understanding of the data characteristics. Subsequently, to infer whether significant differences existed among the different color samples across various dimensions while controlling for individual participant differences, linear mixed models were constructed. The models included participant ID as a random intercept to control for inter-individual differences due to repeated measures, with color sample as a fixed effect. The overall significance and effect sizes of the models were reported first. When a significant overall effect was found, Bonferroni-corrected post hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted to clarify the specific patterns of difference.

To test the validity of the above parametric models, Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests were performed on the standardized residuals of each model. The parameter estimates from models whose residuals met the normality assumption were considered reliable. Adhering to a conservative principle to ensure the robustness of the results, for any variable where either of these two tests was significant (p < 0.050), the non-parametric Friedman test was added as a sensitivity analysis. This non-parametric method does not require variables to satisfy a normal distribution and is suitable for the ordinal and continuous variables in this study.

Finally, Spearman’s rank correlation analysis was used to systematically examine the relationships among variables. This included the internal consistency among questionnaire dimensions, the internal associations among eye-tracking metrics, and the relationships between questionnaire scores and eye-tracking metrics. Correlation coefficients were calculated, and p-values were Bonferroni-corrected.

Unless otherwise specified, the significance level for all statistical tests within the study was set at 0.050. Bonferroni correction was applied to the significance levels for all post hoc pairwise comparisons and multiple correlation tests to control for Type I error inflation due to multiple comparisons.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. SD Evaluation Results

3.1.1. Descriptive Statistics

A descriptive statistical analysis was conducted on the ratings of the four subjective evaluation indicators across the five color samples (N = 49), and the results are shown in Table 4. On the dimension of cultural atmosphere perception, Sample 5 received the highest rating for traditional color atmosphere (M = 4.140, SD = 0.842), indicating that participants generally considered it the most representative of the Song Dynasty traditional style; whereas Sample 1 received the lowest rating (M = 2.550, SD = 1.081), perceived as having the weakest traditional color atmosphere. On the dimension of visual comfort, the evaluation results for color matching comfort showed that Sample 5 (M = 4.040, SD = 0.789) received a relatively high rating, with the order of the remaining samples being Sample 4 > Sample 3 > Sample 1 > Sample 2. On the dimension of visual clarity, the two indicators showed different patterns. For artwork form clarity, the rating differences among samples were small (M range: 3.000–3.470), with Sample 4 having the highest perceived clarity (M = 3.470, SD = 1.063). For explanatory text clarity, the differences were more significant. Sample 4 received the highest rating (M = 4.670, SD = 0.851), approaching a “very clear” level. The order of the remaining samples was Sample 5 > Sample 3 > Sample 2 > Sample 1, with Sample 1 (M = 2.080, SD = 0.909) and Sample 2 (M = 2.410, SD = 1.257) ratings significantly lower.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of subjective perception questionnaire ratings (N = 49).

Overall, based on the mean scores, Sample 5 (M = 3.933) and Sample 4 (M = 3.725) received higher comprehensive subjective evaluations, while Sample 1 (M = 2.628) and Sample 2 (M = 2.645) received relatively lower comprehensive ratings.

3.1.2. Linear Mixed Model Analysis

To further examine the impact of different color samples on the four subjective rating indicators while controlling for individual participant differences, linear mixed models were established. The four subjective evaluation indicators were used as dependent variables, with color sample as a fixed effect and participant as a random intercept.

Type III tests of fixed effects indicated that the color sample had the strongest influence on explanatory text clarity, F(4, 192) = 69.199, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.590, indicating that the color sample factor explained nearly 60% of the variance in text clarity, making it a decisive factor (Table 5). The differences in color samples also had substantial effects on traditional cultural atmosphere perception (F(4, 192) = 23.635, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.330) and color matching comfort (F(4, 192) = 26.002, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.351). In contrast, the effect of color sample on artwork form clarity, while statistically significant (F(4, 192) = 2.485, p = 0.045), had a very small effect size (partial η2 = 0.049). This indicates that although detectable differences exist in artwork form clarity among different color samples, the color factor explains less than 5% of the variance.

Table 5.

Results of Type III tests of fixed effects from Linear Mixed Models examining the impact of color samples on subjective perception metrics (N = 49) 1.

Regarding random effects, the covariance parameter estimates for all four dependent variables showed that the variance components for the participant random intercepts reached statistical significance (traditional cultural atmosphere: variance = 0.301, p = 0.001; color comfort: variance = 0.185, p = 0.020; artwork form clarity: variance = 0.476, p < 0.001; text clarity: variance = 0.184, p = 0.016). This result confirms significant individual differences among participants, justifying the inclusion of a random intercept in the linear model to control for such variation. Furthermore, the residual variances of the models were all significant (all p < 0.001), indicating good model fit.

Post hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction were performed for the four indicators. For the traditional cultural atmosphere indicator (Table 6), the rating for Sample 5 was significantly higher than all other samples (all p < 0.050), indicating it elicited the strongest traditional cultural atmosphere perception. Secondly, the rating for color sample 4 was also significantly higher than samples 1 and 2 (all p < 0.050). The rating for color sample 1 was significantly lower than samples 3, 4, and 5 (all p < 0.050), indicating the weakest traditional sense. Additionally, the pairwise differences between sample 1 and sample 2, sample 2 and sample 3, and sample 3 and sample 4 were not significant (all p > 0.050).

Table 6.

Post hoc pairwise comparisons of mean differences for the traditional cultural atmosphere perception metric based on estimated marginal means (N = 49) 1.

For the color comfort indicator (Table 7), the rating for Sample 5 was significantly higher than all other samples (all p < 0.050). The rating for Sample 4 was significantly higher than samples 1, 2, and 3 (mean differences = 0.878, 1.041, and 0.755, respectively, all p < 0.050) but significantly lower than Sample 5 (mean difference = −0.653, p < 0.050). Furthermore, the pairwise comparisons among samples 1, 2, and 3 did not reach significance (all p > 0.050), suggesting that these three samples were perceived as similarly comfortable, with no statistically significant differences.

Table 7.

Post hoc pairwise comparisons of mean differences for the color comfort metric based on estimated marginal means (N = 49) 1.

For artwork form clarity (Table 8), although mean differences indicated some numerical variation, the possibility that these differences resulted from random fluctuation was greater than the preset significance level (all p > 0.050). The statistical evidence does not support the conclusion that different color samples cause systematic differences in the perception of artwork form clarity.

Table 8.

Post hoc pairwise comparisons of mean differences for the artwork form clarity metric based on estimated marginal means (N = 49) 1.

The perception of explanatory text clarity showed a significant hierarchical order (Table 9). The rating for Sample 5 was significantly higher than samples 1, 2, and 3 (mean differences = 2.163, 1.837, and 1.041, respectively, all p < 0.050). Similarly, the rating for Sample 4 was significantly higher than samples 1, 2, and 3 (mean differences = 2.592, 2.265, and 1.469, respectively, all p < 0.050). Additionally, the rating for Sample 3 was significantly higher than samples 1 and 2 (mean differences = 1.122 and 0.796, p < 0.050). The only comparison that did not reach significance was the difference between Sample 4 and Sample 5 (mean difference = −0.429, p > 0.050). That is, Samples 4 and 5 had the highest clarity ratings without a significant difference between them; both were significantly higher than Sample 3, which in turn was significantly higher than Samples 1 and 2.

Table 9.

Post hoc pairwise comparisons of mean differences for the explanatory text clarity metric based on estimated marginal means (N = 49) 1.

Normality tests were conducted on the standardized residuals of the linear mixed models (Table 10). The residuals for cultural atmosphere perception and artwork form clarity met the normality assumption (all p > 0.050), so the results of their linear mixed models are reliable. However, the residuals for color comfort and text clarity rejected the normality assumption in at least one test (p < 0.050), suggesting that the inferences from the linear mixed models for these measures might be affected by distributional deviations.

Table 10.

Normality test results of standardized residuals for the linear mixed models on the four subjective perception metrics (N = 49) 1.

3.1.3. Non-Parametric Tests

The non-parametric Friedman test for color comfort was significant (χ2(4) = 69.771, p < 0.001), indicating statistically significant differences in the distribution of comfort ratings among different color samples. Post hoc pairwise comparisons, based on Adjusted Significance, showed a pattern highly consistent with the linear mixed model results: the comfort rating for Sample 5 was significantly higher than Samples 1, 2, 3, and 4 (all Adj. Significance ≤ 0.001); the rating for Sample 4 was significantly higher than Samples 1, 2, and 3 (Adj. Significance = 0.010, <0.001, 0.049, respectively); whereas the difference between Sample 4 and Sample 5 (Adj. Significance = 0.197) and the differences among Samples 1, 2, and 3 (all Adj. Significance = 1.000) were not significant. The conclusions from the non-parametric test further support the significant advantage of Sample 5 in eliciting comfort perception, and this result is robust, not constrained by data distribution assumptions.

The non-parametric Friedman test results indicated significant differences in the distribution of text clarity ratings among different color samples, χ2(4) = 115.036, p < 0.001. Post hoc pairwise comparisons revealed a clear hierarchy among the samples. The ratings for both Sample 4 and Sample 5 were significantly higher than those for Samples 1, 2, and 3 (Adj. Significance < 0.0500 for all relevant comparisons). However, the difference between Sample 4 and Sample 5 did not reach significance (Adj. Significance = 1.000). Among Samples 1, 2, and 3, some comparisons showed significant differences: the rating difference between Sample 1 and Sample 3 was significant (Adj. Significance = 0.004), while the differences between Sample 1 and Sample 2 (Adj. Significance = 1.000) and between Sample 2 and Sample 3 (Adj. Significance = 0.073) were not significant. Overall, text clarity ratings were highest for Sample 4 and Sample 5, with no significant difference between them, while the ratings for Samples 1, 2, and 3 were relatively lower, with a complex pattern of internal differences.

3.2. Eye-Tracking Survey Results

3.2.1. Descriptive Statistics

Due to a small number of missing values in the data exported from the eye-tracker, missing value processing was performed prior to analysis. For missing values in the time to first entry into Level-1 and Level-2 AOIs, indicating that the participant did not fixate on that area in the respective trial, they were imputed with the trial’s maximum value of 15 s, providing a conservative estimate of attentional capture delay. For missing values in the fixation duration on Level-1 and Level-2 AOIs, they were imputed as 0 s, indicating that no fixation time was allocated to that area. Descriptive statistics results, including means and standard deviations, are shown in Table 11.

Table 11.

Descriptive statistics of objective eye-tracking data (N = 49).

Specifically, regarding the time to first entry metric, different levels of Areas of Interest exhibited different patterns. For the Level-1 AOI (floral arrangement area), Sample 1 had the shortest time to first entry (M = 0.654 s, SD = 0.903), indicating it could quickly attract initial visual attention; whereas Sample 3 had the longest time to first entry (M = 2.643 s, SD = 3.910), indicating a relatively slower initial attentional capture. For the Level-2 AOI (text area), Sample 3 had the shortest time to first entry (M = 2.911 s, SD = 4.992), and Sample 4 had the longest (M = 4.632 s, SD = 6.166).

Regarding fixation duration, the fixation duration on the Level-1 AOI was generally longer than that on the Level-2 AOI. Sample 1 had the longest fixation time on the Level-1 AOI (M = 5.762 s, SD = 2.923), while Sample 4 had the shortest (M = 4.749 s, SD = 3.399), with the order being Sample 1 > Sample 3 > Sample 2 > Sample 5 > Sample 4. For the Level-2 AOI, Sample 5 had the longest fixation time (M = 4.187 s, SD = 3.273), with the order of the remaining samples being Sample 2 > Sample 3 > Sample 1 > Sample 4.

Analysis of the total fixation duration showed that the overall attentional investment across samples was relatively stable, with means ranging from 7.44 s to 9.16 s. Among them, Sample 2 had the longest total fixation time (M = 9.156 s, SD = 3.347), and Sample 4 had the shortest (M = 7.441 s, SD = 3.681). The standard deviations of the metrics indicated a certain degree of individual differences in the data.

3.2.2. Linear Mixed Model Analysis

To further investigate the effects of different color samples on the five objective eye-tracking metrics while controlling for individual participant differences, linear mixed models were established. The five subjective evaluation metrics were used as dependent variables, with color sample as a fixed effect and participant as a random intercept.

Type III tests of fixed effects results (Table 12) indicated that color samples had a significant main effect on some eye-tracking metrics, with varying effect sizes. The main effect of color sample on total fixation duration was highly significant (F(4, 192) = 6.318, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.116), indicating that different color samples attracted significantly different levels of overall attentional investment. Furthermore, color samples also had a significant effect on the time to first entry into the Level-1 AOI (F(4, 192) = 3.429, p = 0.010, η2 = 0.067) and the fixation duration on the Level-2 AOI (F(4, 192) = 3.173, p = 0.015, η2 = 0.062), indicating that color influenced early attentional capture and processing depth in specific areas. However, the main effects of color sample on the time to first entry into the Level-2 AOI (p = 0.064) and the fixation duration on the Level-1 AOI (p = 0.144) did not reach statistical significance, indicating no significant differences between color samples for these two metrics; thus, post hoc comparisons were not conducted for them.

Table 12.

Results of Type III tests of fixed effects from Linear Mixed Models examining the impact of color samples on objective eye-tracking data (N = 49) 1.

After the linear mixed model showed a significant main effect, post hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted for the time to first entry into the Level-1 AOI metric across different color samples (Table 13). The time to first entry for color sample 1 was significantly later than for sample 3 and sample 4 (mean differences = −1.989 s and −1.694 s, respectively, all p < 0.050), indicating its lowest efficiency in attentional capture. However, the differences between color sample 1 and samples 2 and 5, as well as all pairwise comparisons among samples 2, 3, 4, and 5, did not reach statistical significance (all p > 0.050). This result indicates that, in terms of initial attentional capture speed, the efficiency of color sample 1 was significantly lower than that of samples 3 and 4, while the efficiency of samples 2, 3, 4, and 5 in attracting initial attention was relatively similar, with no significant differences.

Table 13.

Post hoc pairwise comparisons of mean differences for the time to first entry into level-1 AOI metric based on estimated marginal means (N = 49) 1.

Regarding the fixation duration on the Level-2 AOI (Table 14), the linear mixed model results showed that only the difference in fixation duration between sample 4 and sample 5 reached statistical significance, with the fixation duration of sample 4 being significantly lower than that of sample 5. Apart from this, the differences in fixation duration between all other pairs of color samples were not significant (all p > 0.050). For the Level-2 AOI, sample 5 could elicit a significantly longer visual attention dwell time than sample 4. However, among the other samples, no statistically significant differences in attention dwell time were observed.

Table 14.

Post hoc pairwise comparisons of mean differences for the fixation duration on level-2 AOI metric based on estimated marginal means (N = 49) 1.

Regarding total fixation duration (Table 15), the total fixation duration of color sample 4 was significantly shorter than that of the other samples, with mean differences of −1.259, −1.715, −1.465, and −1.521 compared to samples 1, 2, 3, and 5, respectively (all p < 0.050). In contrast, none of the pairwise comparisons among samples 1, 2, 3, and 5 reached significance (all p > 0.050). The results indicate that color sample 4 exhibited a unique pattern in attracting visual attention investment, with its total fixation duration significantly different from all other samples, while the total attention investment received by samples 1, 2, 3, and 5 was relatively similar.

Table 15.

Post hoc pairwise comparisons of mean differences for the total fixation duration on AOIs metric based on estimated marginal means (N = 49) 1.

Normality tests were conducted on the standardized residuals of the linear mixed models for the eye-tracking metrics that showed a significant main effect. The results are shown in Table 16. Since the residuals for all three metrics rejected the null hypothesis of normality in at least one test (p < 0.050), non-parametric tests were supplemented.

Table 16.

Normality test results of standardized residuals for the linear mixed models on partial objective eye-tracking metrics (N = 49) 1.

3.2.3. Non-Parametric Tests

A non-parametric related-samples Friedman test was additionally conducted for the time to first entry into the Level-1 AOI. The results differed from the linear mixed model. The Friedman test indicated that the overall distribution of the five color samples on this metric was not statistically significantly different (χ2(4) = 6.663, N = 49, p = 0.155). As the overall test was not significant, no post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed.

Post hoc comparison results from the non-parametric Friedman test for the fixation duration on the Level-2 AOI showed a significant difference in data distribution (χ2(4) = 21.969, N = 49, p < 0.001). The fixation duration for sample 5 was significantly longer than that for sample 1 (Adj. Significance = 0.001) and sample 4 (Adj. Significance = 0.001). All other pairwise comparisons were not significant (all Adj. Significance ≥ 0.0500). In summary, the results of the non-parametric test partially supported the findings of the linear mixed model; both confirmed that the fixation duration of sample 5 was significantly longer than that of sample 4, but the non-parametric test also revealed a more detailed pattern: the fixation duration of sample 5 was also significantly longer than that of sample 1 in the non-parametric test, a difference that did not reach significance in the linear mixed model.

For total fixation duration, there was a significant difference in the data distribution (χ2(4) = 14.955, N = 49, p = 0.005). The results showed that the total fixation duration for sample 4 was significantly longer than that for sample 2 (Adj. Significance = 0.006), sample 3 (Adj. Significance = 0.022), and sample 5 (Adj. Significance = 0.049), but the difference with sample 1 did not reach the corrected significance level (Adj. Significance = 0.127). Furthermore, all pairwise comparisons among samples 1, 2, 3, and 5 were not significant (all Adj. Significance = 1.000). This result corroborates the findings of the linear mixed model.

3.3. Correlation Analysis

3.3.1. Internal Correlation Analysis of Subjective Perception

Non-parametric Spearman rank correlations were calculated for all pairs of subjective perception indicators. The results are shown in Table 17. They indicate that all pairs of subjective perception indicators exhibited statistically significant positive correlations (all p < 0.050), but the strength of the associations varied.

Table 17.

Spearman’s rank correlation matrix among the four subjective perception metrics (N = 49) 1.

3.3.2. Internal Correlation Analysis of Eye-Tracking Indicators

Internal correlation analysis of the five eye-tracking indicators revealed significant patterns of internal relationships among the metrics, shedding light on the patterns of visual attention allocation across different Areas of Interest and different attentional stages. The results are shown in Table 18.

Table 18.

Spearman’s rank correlation matrix among the five objective eye-tracking metrics (N = 49) 1.

Regarding early attentional capture, the time to first entry into the Level-1 AOI and the time to first entry into the Level-2 AOI showed a significant negative correlation (rs = −0.307, p < 0.01), reflecting the competitive relationship of attention during visual search. Regarding sustained attentional investment, the fixation duration on the Level-1 AOI and the fixation duration on the Level-2 AOI showed a significant negative correlation (rs = −0.367, p < 0.01). The strength of this relationship was greater than the negative correlation in the early orienting stage.

Total fixation duration, as an indicator of overall attentional investment, benefited mainly from deep processing of the text area. The analysis showed a strong positive correlation between total fixation duration and fixation duration on the text area (rs = 0.560, p < 0.01), while its positive correlation with fixation duration on the floral area was relatively weaker (rs = 0.482, p < 0.01).

Finally, there was a link between early attention and subsequent processing. For both the floral and text areas, the later the time to first entry into an area, the shorter the total fixation time subsequently invested in that area (Floral: rs = −0.251, p < 0.01; Text: rs = −0.574, p < 0.01). This “late discovery, shallow processing” effect was particularly evident for the text area.

3.3.3. Internal Correlation Analysis of Subjective Perception and Eye-Tracking Behavior

Under the conditions of this study, none of the correlations between the subjective questionnaire scores and the eye-tracking indicators reached statistical significance (all p > 0.050). Specifically, the correlation coefficients between the early attentional orienting indicators (time to first entry into the floral area, time to first entry into the text area) and the four subjective perception dimensions were all close to zero (absolute values all less than 0.11), and the p-values were far above the significance level of 0.050. This indicates that the formation of participants’ subjective perception of the floral arrangement exhibition was not significantly associated with the speed of their initial gaze capture. The results are shown in Table 19.

Table 19.

Spearman’s rank correlation matrix among subjective perception and objective eye-tracking metrics (N = 49) 1.

Regarding sustained attentional investment indicators, no significant correlations were found between fixation duration on the floral area, fixation duration on the text area, total fixation duration, and the various subjective scores. Although individual coefficients showed weak trends—for example, a weak positive trend between comfort and fixation duration on text (rs = 0.124, p = 0.053), and a weak negative trend between text clarity and total fixation duration (rs = −0.123, p = 0.054)—none of these trends reached the statistical significance threshold.

4. Discussion

4.1. Subjective Perception Differences and Internal Associations of Traditional Color Schemes

The subjective evaluation results show that different traditional color schemes elicited significant perceptual differences across dimensions such as cultural atmosphere, comfort, and clarity. Samples 4 and 5 received significantly higher ratings than other samples on three dimensions: traditional cultural atmosphere perception, color matching comfort, and explanatory text clarity. Analyzing the color attributes, the dominant hue of Samples 4 and 5 (H = 11°) is a warm red tone with low saturation (S = 59) and medium-high brightness (B = 71). This color characteristic, originating from historical architectural environments, can effectively evoke viewers’ visual memory of traditional Song Dynasty cultural spaces [31], thereby fostering a high level of traditional cultural atmosphere identification on a subjective level. In contrast, although Samples 2 (Vermilion-Blue Green) and 3 (Vermilion-Medium Green) possess a traditional hue, the excessively large hue difference between their dominant and accent colors (ΔH > 130°) might have diminished the overall sense of historical stability, leading to relatively lower traditional perception scores [32]. However, there was no significant difference in artwork form clarity among the samples. This suggests that for image objects with complex forms and rich details like floral arrangement works, the recognition of their contours and structure may depend more on their own shape, lighting, and texture, with background color having a relatively limited regulatory effect on their clarity.

Internal correlation analysis among the subjective perception dimensions further revealed the underlying structure of the evaluation indicators. Spearman correlation analysis indicated a moderate-strength, significant positive correlation between traditional cultural atmosphere perception and color matching comfort. This reflects a tendency for participants’ perception of cultural traditionality and their experienced visual comfort to co-vary, suggesting that, within the cultural context of this study, color combinations conforming to historical characteristics are more likely to elicit positive emotional reactions. However, the correlation between traditional perception and artwork form clarity was only weakly positive, indicating that aesthetic-cultural evaluation is relatively independent from the functional perception of object form details, and the mechanisms by which they are influenced by color schemes differ.

Sample 4 (Earth Red-White), with its maximum brightness contrast (ΔB = 29), achieved the highest text clarity rating, suggesting that high brightness contrast is a key factor ensuring visual readability in functional information presentation [33]. Meanwhile, Sample 5 (Earth Red-Yellow) achieved a balance between comfort and traditional feel through a moderate hue difference (ΔH = 28°) and brightness difference (ΔB = 16). Therefore, in the color design of display spaces, if ensuring the readability of textual information is a priority, efforts should focus on strengthening the brightness contrast between the background and the text [34,35]. Conversely, if the goal is to create an overall harmonious, immersive cultural experience, priority could be given to employing harmonizing color schemes using analogous hues [23].

4.2. Attention Allocation Mechanisms Reflected in Eye-Tracking Behavior Patterns

Eye-tracking data reflected the complex mechanisms by which color regulates cognitive resource allocation across multiple levels, from early orientation and sustained processing to overall investment. First, regarding early attentional orientation, descriptive statistics showed differences in the speed with which different color samples attracted initial gaze to the core exhibits: Sample 1 had the shortest time to first entry, while Sample 3 had the longest. Linear Mixed Model analysis showed a significant main effect of color sample, with post hoc comparisons suggesting the time to first entry for Sample 1 was significantly later than for Samples 3 and 4. However, given the severe deviation of the model residuals from a normal distribution, the supplementary non-parametric Friedman test result indicated that the overall difference among the five samples on “time to first entry into the Level-1 AOI” did not reach statistical significance. This inconsistency may stem from the sensitivity of the parametric test to model assumptions. The more robust non-parametric result suggests that the overall effect of different color schemes in rapidly capturing initial attention to the core exhibits may not be as strong and general as indicated by the linear mixed model. Nonetheless, the descriptive trend and LMM post hoc comparisons jointly point to a specific pattern among Samples 1, 3, and 4, warranting further verification in subsequent research.

Secondly, regarding sustained attentional investment, the results indicate that color influenced the dwell depth and allocation of visual attention. For fixation duration on the text area, descriptive statistics showed that Sample 5 had the longest fixation time. Both the Linear Mixed Model and its robustness verification (non-parametric Friedman test) confirmed a significant main effect of color sample. Post hoc comparisons consistently showed that the fixation duration for Sample 5 was significantly longer than for Sample 4, and the non-parametric test further revealed it was also significantly longer than for Sample 1. This indicates that the color scheme used in Sample 5 effectively guided viewers to spend more time reading and processing the auxiliary textual information [36]. This effect might be related to the good readability (high brightness contrast) and overall sense of comfort provided by the color scheme, encouraging viewers to invest more cognitive resources in understanding the text content. Conversely, although Sample 4 scored highest in subjective text clarity, its fixation duration on the text area was relatively shorter. This might be because its extremely high brightness contrast allowed for rapid information extraction without stimulating deeper processing.

At the level of overall attentional investment, the influence of color was most significant and consistent. Descriptive statistics showed that Sample 2 had the longest total fixation duration, while Sample 4 had the shortest. Both linear mixed models and non-parametric tests supported a highly significant main effect of color sample on total fixation duration. Post hoc analyses jointly revealed a core pattern: the total fixation duration for Sample 4 was significantly shorter than for Samples 2, 3, and 5. This indicates that while the “Earth Red-White” scheme of Sample 4 ensured basic information clarity, it was relatively weaker in stimulating and maintaining overall visual exploration and processing motivation. Combining the descriptive data, Samples 2 and 5, which obtained longer total fixation durations, also had relatively higher fixation durations on the text area, suggesting that deep processing of textual information is a key factor driving the increase in overall visual investment.

Internal correlation analysis among the eye-tracking indicators provided a deeper cognitive mechanism explanation for the above findings. First, the significant negative correlation between fixation duration on Level-1 and Level-2 AOIs corroborates the competitive allocation of attentional resources between the core image and auxiliary text. Second, the strong positive correlation between total fixation duration and fixation duration on the text area further supports the inference of “text processing dominating total investment.” Finally, the negative correlation between time to first entry and fixation duration (especially for the text area) reveals an “early capture advantage”: the later an area is noticed, the fewer processing resources it receives. This might partially explain why Sample 4 had high subjective text clarity scores but relatively lower fixation duration—its overall later attentional capture (descriptive statistics showed it had the longest time to first entry into the Level-2 AOI) might have limited subsequent deep processing.

In summary, traditional color schemes systematically influenced attention allocation during the viewing process by modulating visual salience. Successful color translation (e.g., Sample 5) can not only receive positive subjective evaluations but also objectively guide more efficient and in-depth visual information processing patterns, manifested as balanced attention to core exhibits and auxiliary information, along with deep reading of text content, thereby prolonging the overall viewing investment [37]. This provides empirical evidence for evaluating and optimizing display space color design from a cognitive-behavioral perspective.

4.3. Separation of Subjective Perception and Objective Eye-Tracking Behavior

This study, through Spearman rank correlation analysis, found that the absolute values of correlation coefficients between all four subjective perception dimensions and the five eye-tracking metrics were below 0.125, and all p-values were greater than 0.050, not reaching statistical significance. This indicates that, within the visual scene established in this experiment, participants’ subjective evaluations of the traditional cultural atmosphere, comfort, and clarity of the works, and their visual attention patterns during the task-free, free viewing process, may be two relatively independent psychological processes. Subjective evaluations are likely more influenced by individuals’ prior aesthetic experience, cultural background, and intrinsic emotional preferences, factors that do not directly drive low-level, spontaneous eye-tracking behaviors.

Compared to findings in some literature reporting significant correlations between subjective and objective metrics, the “separation” result of this study might be influenced by several moderating variables [38]. First, differences in task type could be a key factor: this study employed a free viewing mode, whereas many studies finding significant correlations often use goal-directed tasks. Under free viewing, eye-tracking behavior is more stimulus-driven, while subjective evaluation is more concept-driven. Second, cultural background might have an effect. The participants in this study were all Chinese university students. Their aesthetic evaluations, rooted in a collectivist cultural context, may place more emphasis on overall harmony and cultural connotation, whereas studies in Western cultural contexts might focus more on individualized visual preferences. Additionally, the nature of the stimulus materials cannot be overlooked. This study used floral arrangement display scenes rich in cultural symbols, while many studies have found significant correlations using abstract graphics or simple interfaces. The latter might allow low-level visual features to more directly influence subjective ratings.

This independence of subjective and objective data highlights the necessity and value of jointly using the Semantic Differential Method and eye-tracking [39]. Subjective questionnaires reveal affective and cognitive evaluations based on cultural background and individual experience, while eye-tracking data reflect immediate, unconscious visual behavioral responses. This illustrates that a single research method cannot comprehensively capture the complex impact of color on user experience. The SD-Eye-tracking combined analytical framework, by revealing such multidimensional relationships, can provide a richer and more profound scientific basis for understanding and optimizing design than a single method.

4.4. Research Limitations and Future Prospects

This study, through the combined analysis of the SD method and eye-tracking, systematically explored the translation effects of traditional colors in modern display spaces. However, there remain some limitations in research design, sample selection, and data interpretation, which also point the way for future research.

First, regarding the study sample, the 49 participants in this study were all from Chinese universities, aged between 17 and 42, and all had some prior knowledge of the traditional Song Dynasty style. While this relatively homogeneous cultural background sample ensured consistency in participants’ understanding of the experimental materials, it also, to some extent, limited the generalizability of the research conclusions. People within the same cultural background often share common perceptions of color [40,41], and viewers from different cultural backgrounds might perceive and interpret traditional colors differently. For example, Western viewers might lack the cognitive foundation for the cultural connotations of traditional Chinese colors, and their evaluation criteria and eye-tracking patterns might differ from the results of this study. Therefore, future research could include participants from a wider range of cultural backgrounds to conduct cross-cultural comparative studies, testing the cultural specificity and universality of color perception.

Additionally, the gender distribution within the sample was imbalanced (9 males, 40 females). Although the linear mixed models controlled for individual baseline differences by including participant ID as a random intercept, the potential influence of gender as a variable on color perception was not specifically tested as a fixed effect. The overrepresentation of female participants may limit the generalizability of the current findings to male populations, as some studies suggest potential gender differences in color preference and emotional responses to color. Future studies should aim for a more balanced gender distribution and explicitly incorporate gender as a factor in the statistical model to examine its potential main or interactive effects.