Abstract

This study provides a comprehensive three-dimensional Computational Fluid Dynamics analysis of airflow distribution in a surgical operating room under realistic occupancy and equipment conditions. Using integrated modelling in SolidWorks and a subsequent analysis in ANSYS Fluent, a full-scale Operating Room geometry was simulated to assess the effectiveness of a laminar airflow system. The model includes surgical staff mannequins, thermal loads from surgical lights, and medical equipment that commonly disrupt unidirectional flow patterns. A polyhedral mesh with over 2.8 million nodes was employed, and a grid independence study confirmed solution reliability. The realisable k–ε turbulence model with enhanced wall treatment was used to simulate steady-state airflow, thermal stratification, and pressure variation due to door opening. Results highlight significant flow disturbances and recirculation zones caused by the shear zone created by supply air, overhead lights and heat plumes, particularly outside the core laminar air flow zone. The most important area, 10 cm above the surgical site, shows a maximum velocity gradient of 0.09 s−1 while the temperature gradient shows 6.7 K.m−1 and the pressure gradient, 0.0167 Pa.m−1. Streamline analysis reveals potential re-entrainment of contaminated air into the sterile field.

1. Introduction

Surgical procedures demand an exceptionally clean environment to minimise the risk of surgical site infections (SSIs). Among the several sources of viable microorganisms that can contaminate the surgical field, airborne contamination plays a critical role [1]. The transport and deposition of these airborne agents—originating from external sources such as supply air or infiltration, and internal sources such as skin flora and exhaled air from the surgical crew and the patient [2]—are influenced by multiple factors, including air filtration efficiency, air change rate, local turbulence, airflow direction, staff movement [3], and pressure differentials with adjacent zones.

A properly designed Heating, Ventilating, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) system is therefore essential in an operating room (OR) to reduce the risk of SSIs, maintain thermal comfort, and efficiently remove particulate and gaseous contaminants released during surgical procedures [4,5]. The HVAC system mitigates airborne contaminants through effective filtration, dilution, air exchange rate, temperature and humidity control, and carefully engineered airflow patterns.

Ensuring sterility in operating rooms relies heavily on controlled and stable airflow that minimises turbulence and prevents the re-entry of contaminants into the sterile field [6,7,8]. The ventilation design typically aims to achieve unidirectional laminar airflow (LAF) over the surgical site, which effectively prevents the entrainment and flushes contaminants away from the surgical site. However, several studies have questioned the effectiveness of LAF systems under real operating conditions [9,10]. Airflow disruption caused by personnel movement, surgical equipment, and thermal plumes from heated surfaces can compromise the sterility of the surgical field [11].

In this context, Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has emerged as a powerful and flexible tool for analysing airflow characteristics and optimising ventilation performance in complex indoor environments such as ORs [12,13]. However, only a few studies have attempted comprehensive three-dimensional CFD analyses that include realistic human figures, equipment geometry, and actual boundary conditions representative of operating room environments.

For instance, Ho et al. [14] conducted a three-dimensional CFD analysis of airflow and contaminant removal, including patient and surgical staff geometry, and found good agreement with experimental data. Neumann et al. [15] examined how OR layout affects staff ergonomics and hygiene, emphasising the impact of design on surgical performance. Duque-Daza and Murillo-Rincon [16] used quasi-Direct Numerical Simulations (qDNS) to analyse airflow in ultra-clean operating theatres, showing that even with laminar supply air, the geometry of the room fosters turbulence and recirculation zones. Zheng et al. [17] validated a discrete-event simulation of OR workflow with empirical hospital data, demonstrating the operational impact of layout and ventilation. Memarzadeh and Jiang [18] analysed how ceiling height and air change rate affect particle deposition, concluding that ventilation performance degrades significantly with reduced ceiling height.

Previous investigations have shown that inadequate airflow design can induce eddies [19], promote particle recirculation [20], and cause re-entrainment of contaminated air into the sterile region [21]. Moreover, most prior CFD studies simplified the OR environment by modelling personnel and patients as basic cuboids and neglecting essential obstructions such as surgical lights and pendants, which significantly affect airflow behaviour [22]. Such simplifications facilitate easy discretisation and reduce computational load but compromise realism, limiting the applicability of their findings to actual operating room conditions.

The present study addresses these limitations through a full-scale CFD simulation of a realistic operating room that incorporates detailed geometries of surgical lights, pendants, and medical staff. A commercial CFD solver was used to evaluate the airflow patterns, temperature distribution, and pressure fields under realistic operating conditions. The model is validated against experimentally reported data from Ho et al. (2009) [14] and Wang et al. (2021) [5] to ensure reliability of the numerical predictions.

The specific objectives of this study are to

- i.

- Verify the unidirectional nature of the flow field in the surgical site.

- ii.

- Study the effects of obstacles like surgical lights and fixtures in the sterile flow field.

- iii.

- Study the effect of thermal plumes.

- iv.

- Examine variations in the flow patterns due to door opening.

- v.

- Study the nature of flow outside the laminar flow region.

The insights gained from this study will assist hospital HVAC engineers and infection control specialists in optimising ventilation designs for improved sterility, contaminant control, and thermal comfort in operating rooms.

2. Materials and Methods

Integrating ANSYS 19.2 with SolidWorks offers advantages for simulation and analysis by leveraging SolidWorks for design and ANSYS for in-depth analysis. This allows creating detailed three-dimensional (3D) models in SolidWorks and then transferring them to ANSYS for tasks like structural analysis and CFD simulation, maximising the capabilities of both software.

The key assumptions made to enable this study are as follows:

Radiative heat transfer is not considered to reduce the computational load since light emitting diode (LED)-based light sources provide lesser radiation in the infra-red (IR) region contributing to heat. Moreover, the LED driver and related components that produce heat are assumed to be away from the flow field and hence are less significant compared to old incandescent lamps.

Psychrometry is not considered. Due to the high flow rate of air in the flow field, it experiences only a slight temperature variation. The only contributors of water vapour are human beings (surgical operating crew and the patient), and the dry bulb temperature of air is far away from its dew point temperature, avoiding the possibility of condensation. Therefore, it is considered as a single component with the properties of a combined mixture.

The mannequins are simplified, maintaining height proportions and surface area.

Positions of surgical lights are fixed, and booms for light and pendant are omitted.

Positions of surgeons and other crew members are fixed.

The operating room contains two surgeons, two nurses, one assistant and a patient represented by mannequins.

- Geometry Development

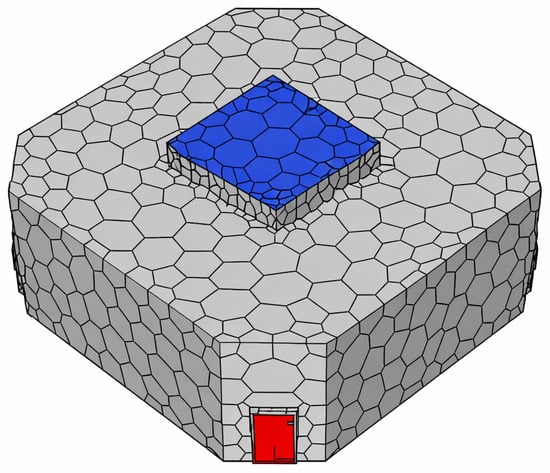

A full-scale 3D model of a surgical operating room was created using SolidWorks Premium 2022 SP5.0.

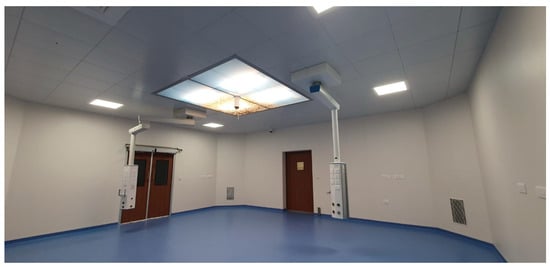

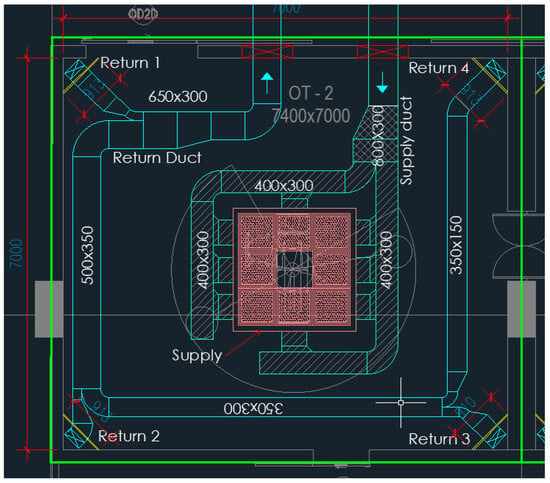

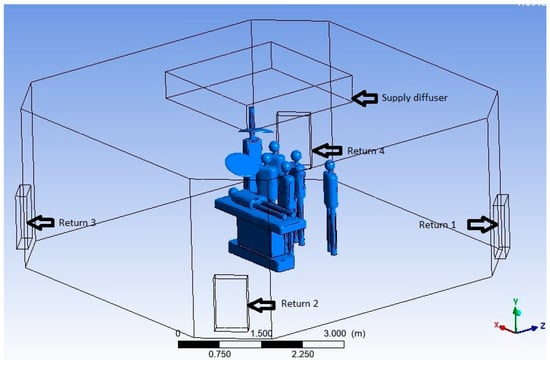

Figure 1 shows the size and expanse of the OR, whereas Figure 2 shows the HVAC ducting layout of the OR. The supply diffuser—called a laminar air flow diffuser—which has a terminal HEPA filter (efficiency 99.97% @ 0.3 µm particle) and four segments, which are connected to the supply duct. The supply duct carries air is treated psychrometrically and filtered with a 20-micron pre-filter and a 5-micron bag filter (Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value MERV 8) in a dedicated Air Handling Unit (AHU). The supply diffusers are placed at the geometric centre of the room above the patient table. The return diffusers of four numbers are placed at the four corners of the room, which are connected to the return duct running above the plenum. Figure 3 illustrates the room layout and placement of fixtures and mannequins in realistic proportions and fixed positions. The model includes all relevant internal components, such as walls, ceiling, floor, supply and return diffusers, surgical lights, pendant, operating table, and six mannequins representing surgical staff and a patient lying on the operating table.

Figure 1.

OR geometry in actual size.

Figure 2.

HVAC duct layout in CAD.

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional model of computational domain.

- Computational domain

The fluid domain represents the air volume inside the OR with the dimensions specified in Table 1, and the specifications of internal objects used in the computational domain are given in Table 2. Figure 3 shows the segmented fluid domain ready for meshing, clearly illustrating the items specified in Table 2 along with walls, the floor and the ceiling of the OR.

Table 1.

Fluid domain dimensions.

Table 2.

Internal objects used in computational domain and their specifications.

- Meshing

The meshing process plays a critical role in capturing the complex flow dynamics within the operating room environment. A high-quality mesh ensures accurate resolution of velocity, pressure, and thermal gradients around obstructions such as surgical lights, medical personnel, and equipment. The geometric model of the OR, developed in SolidWorks, was imported into ANSYS Meshing 19.2 for discretisation.

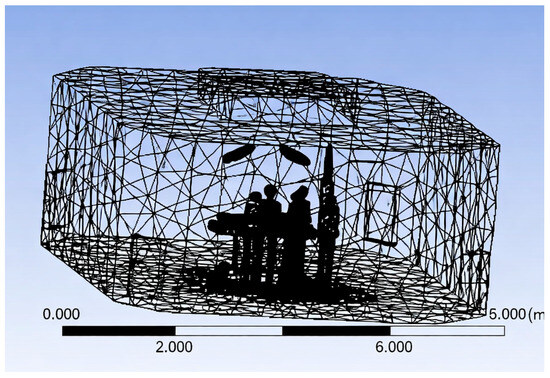

The fluid domain, representing the air volume within the room, was carefully meshed with attention to the regions surrounding internal features, such as mannequins, surgical lights, pendant arms, and diffusers (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional meshing of computational domain.

A polyhedral mesh was adopted for improved convergence behaviour and to efficiently capture complex flow features while keeping computational costs manageable (Figure 5). Mesh refinement was applied near walls, around obstacles, and in the vicinity of the surgical field to resolve boundary layer behaviour and eddy formation with higher fidelity.

Figure 5.

Mesh converted to polyhedron.

- Grid Independence Study

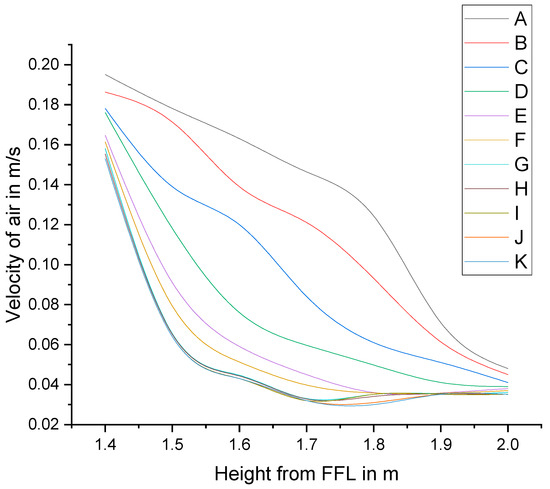

A detailed grid independence study was conducted to ensure solution accuracy. The native meshing tools in ANSYS Fluent were used. A total of eleven sets of meshes were generated with maximum element size varying from one meter to four centimetres (Table 3). All meshes were evaluated for quality using Fluent’s built-in mesh diagnostics. The final mesh exhibited a maximum skewness below 0.85 and a minimum orthogonal quality above 0.15, both within acceptable thresholds for robust convergence.

Table 3.

Mesh details of trial sets.

Simulations were performed using identical boundary conditions and solver settings for each mesh. Since the present study focuses on the local velocity of air at and above the surgical site, the local velocity of air in measured in a vertical line from the surgical site—approximately the mid portion of the bed—to a height of 2 m. The solution was considered grid-independent when the variation in the velocity between successive meshes dropped below 2% and the velocity profile was almost the same (Figure 6). The final analysis was completed with set J.

Figure 6.

Velocity profiles of selected trial meshes.

- Mesh Statistics

- Total elements: 517,828

- Total nodes: 2,850,793

- Maximum element size: 0.06 m

- Minimum orthogonal quality: 6.36 × 10−3

- Maximum aspect ratio: 447.1

The minimum orthogonal quality, though relatively low, was within acceptable limits to ensure numerical stability. Local mesh adjustments were made to improve skewness and avoid negative volume cells, especially near curved and narrow regions such as light arms and the edges of the surgical table. The final mesh provided a balanced trade-off between computational efficiency and solution accuracy, enabling a robust simulation of airflow patterns, temperature fields, and pressure distribution across the domain.

After applying targeted local refinement near critical regions—such as the diffuser inlets, patient zone, and surgical lamps—the mesh quality was notably enhanced. The revised mesh exhibited the following qualities:

- Minimum orthogonal quality improved from 6.36 × 10−3 to 2.41 × 10−1.

- Maximum aspect ratio reduced from 447.1 to 78.4.

A grid sensitivity study was conducted to ensure appropriate near-wall resolution. For the realisable k-ε model with standard wall functions, the first-layer height was selected to achieve y+ ≈ 30–50 on most surfaces. Regions of high shear, such as near the surgical table, surgical light fittings, around the patient and air diffusers, were refined to maintain y+ < 10.

- CFD Simulation Setup

Simulations were performed using ANSYS Fluent (Release 19.2) with the following setup:

Turbulence model: Realisable k–ε model with enhanced wall treatment.

Discretisation schemes: Second-order upwind for momentum, energy, turbulence quantities; SIMPLE algorithm for pressure–velocity coupling.

Gradient calculation: Least-squares cell-based.

Boundary conditions:

Supply diffusers: Constant velocity inlet with an inlet air velocity of 0.2 m·s−1.

Return diffusers: Outflow or pressure outlet boundary with a gauge pressure of 2 Pa.

Walls and equipment: No-slip adiabatic or prescribed heat flux (for heated components).

Convergence criteria:

Convergence was assessed based on residual monitoring. A residual target of 1 × 10−4 was set for all governing equations, including continuity, momentum, energy, and turbulence (k, ε).

- Post-Processing

CFD results were analysed in ANSYS CFD-Post, focusing on the following:

Velocity vectors and contours on vertical planes along both length and width of the OR.

Temperature distributions showing thermal plume behaviour and heat stratification.

Streamlines for identifying flow patterns and re-entry paths.

Pressure contours to visualise static pressure gradients and possible backflows.

3. Results and Discussions

Simulation was carried out in ANSYS Fluent. Two planes are used for visualising the parameters. Both planes are cutting the surgical site, approximately centre of the OT table. The plane along the length of the table is called the Lengthwise plane (parallel to XY plane) and that orthogonal to this plane, passing through the centre (parallel to ZY plane) is named the Widthwise plane.

Velocity vectors and contours, streamlines, temperature variation and pressure distribution were obtained along the length and width of the OR.

- Velocity vectors and contours

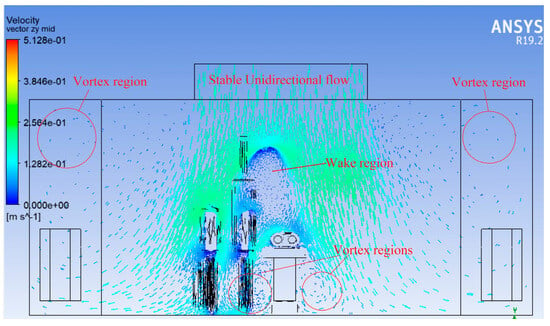

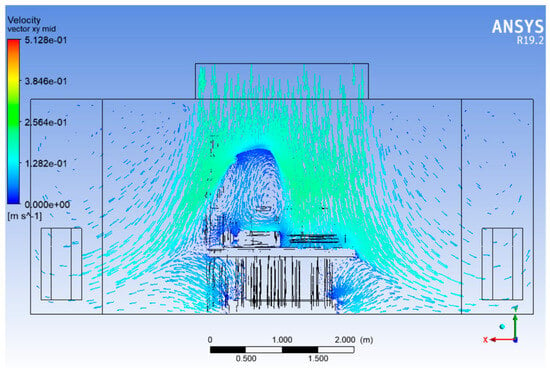

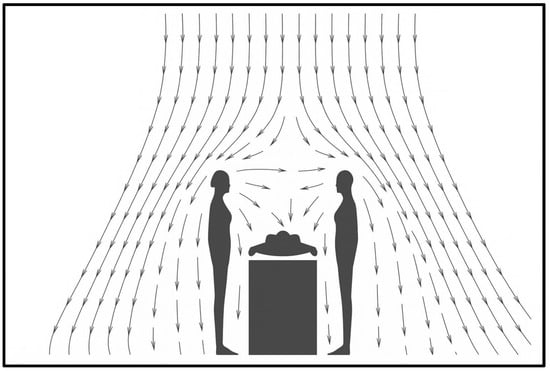

Figure 7 shows the velocity vector plot taken on a vertical plane passing along the width of the operating room, intersecting the centre of the operating table. This plane helps visualise airflow patterns in a cross-sectional slice perpendicular to the length of the OR.

Figure 7.

Velocity vector plot (Widthwise).

At the ceiling level, airflow from the supply diffusers is directed downward, maintaining an initially uniform and laminar profile. As the air approaches the surgical lights and personnel mannequins, disturbance and deflection in the flow vectors are observed. Surgical lights, suspended from the ceiling, act as major obstructions, causing flow separation and deflected streamlines around them. This deflection initiates recirculation zones and eddies, especially on either side of the surgical table.

Flow stagnation and small circulating vortices are visible in regions immediately below and around the light fixtures, indicating areas where the clean, downward flow is disrupted. The formation of eddies is also seen near the walls and floor, where air is forced to change direction toward return diffusers.

Despite the overall downward flow, crossflows and lateral components introduced by obstructions pose a risk of air re-entry or backflow into the sterile surgical zone. This highlights that laminar flow is not preserved uniformly across the entire width and that obstructions above the surgical site significantly affect the airflow integrity.

The vector plot clearly illustrates that the positioning of surgical lights and pendants must be optimised to minimise airflow disruption. There is a need to enhance diffuser design and placement, or to consider local air curtains to protect the sterile area from lateral airflow disturbances.

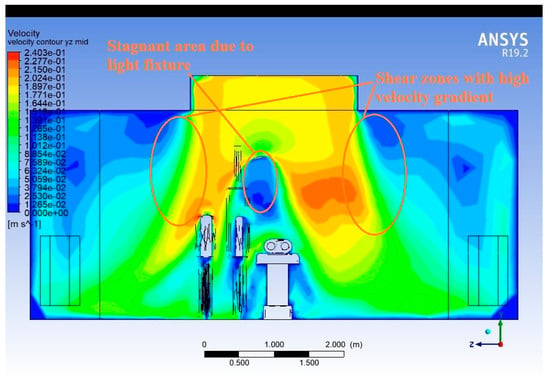

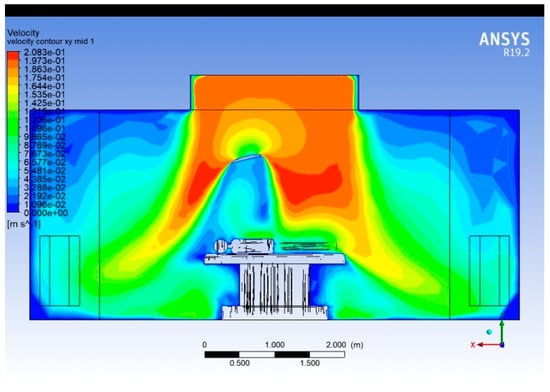

Figure 8 shows the velocity contour plot that is taken on the same vertical cross-sectional plane as the vector plot (Figure 7)—through the width of the operating room and through the centre of the operating table. The contour plot uses a colour gradient to represent airflow velocity magnitudes. Typically, warmer colours (e.g., red, orange) indicate higher velocities, while cooler colours (e.g., blue, green) denote lower velocities or stagnation zones.

Figure 8.

Velocity contour plot (Widthwise).

The central region directly below the supply diffuser shows the highest velocity, confirming the intended unidirectional laminar flow design. However, as the flow descends, zones of lower velocity emerge. Beneath and around the surgical lights, the velocity sharply drops, suggesting flow deceleration due to obstruction. Near the mannequins, flow slows down and becomes more irregular, indicating boundary layer interaction and wake formation. At the floor level, especially near return diffusers, velocity increases slightly again, as the air is pulled toward the outlets.

Asymmetry in velocity distribution across the width indicates that flow uniformity is compromised by localised disturbances. Low-velocity pockets or stagnation zones near the obstructions are potential hotspots for particle accumulation or reverse diffusion, which are detrimental to maintaining sterility.

This plot visually highlights how airflow velocity is not consistently maintained across the width due to real-world elements, like personnel and equipment. Placement and design of supply and return diffusers must be reassessed to ensure higher flow consistency. Design interventions such as repositioning surgical lights or adding directional flow elements may help restore uniform flow fields.

Figure 9 represents airflow vectors on a vertical plane running along the length of the operating room, intersecting the centreline of the surgical table. It provides a longitudinal view of how air flows from the supply diffusers to the return outlets along the room’s main axis.

Figure 9.

Velocity vector plot (Lengthwise).

Downward flow from the ceiling supply diffusers is clearly visible across the entire domain length. The velocity vectors in the central zone above the surgical table generally indicate vertical and unidirectional motion, as intended in laminar flow HVAC design. However, as air approaches surgical lights, mannequins, and the operating table, the flow is visibly deflected and disturbed, creating regions of non-uniform motion.

The surgical lights, mounted overhead, are major sources of flow blockage, resulting in flow divergence around their surfaces. Downstream of these lights, the vectors show eddies and flow recirculation, especially near the head and foot regions of the surgical table. Mannequins representing surgeons and nurses further distort the flow by creating localised wakes and lateral deflections, breaking the uniform flow trajectory. Air is guided toward the return diffusers near the floor along the walls. In doing so, some streamlines curve backwards or laterally, indicating secondary circulations, especially in regions far from the supply diffusers.

Figure 9 emphasises that true laminar flow exists only in the unobstructed vertical core region, while the periphery suffers from flow instability. The backward and swirling flows raise concern about air re-entry into the sterile field, possibly transporting contaminants.

The vector field strongly suggests that airflow management in the head and foot zones of the table needs improvement. Options include modifying the diffuser layout, introducing local air curtains, or repositioning lights and equipment to preserve vertical flow integrity throughout the OR length.

The velocity contour plot that represents the velocity magnitude on a vertical longitudinal plane passing through the centreline along the length of the operating room, aligned with the operating table, is shown in Figure 10. This view captures how airflow develops from one end of the room to the other and how obstacles influence it along the surgical axis.

Figure 10.

Velocity contour plot (Lengthwise).

The impingement of supply air on the surgical zone generates a downward jet that spreads laterally upon reaching the patient table. This results in velocity attenuation to 0.05–0.08 m·s−1 near the operating table surface—within the recommended range for laminar flow conditions (0.2–0.3 m·s−1 supply velocity reducing to <0.1 m·s−1 in the sterile field). The velocity decay from the diffuser to the surgical zone follows a roughly exponential trend, with a reduction of about 60–70% in magnitude over a vertical distance of 1.5 m. This aligns with expected dissipation in low-turbulence laminar diffusers. The region directly above the patient remains dominated by a unidirectional downward airflow (0.08–0.12 m·s−1), which is consistent with cleanroom ventilation design criteria for operating rooms. This ensures adequate contaminant removal and protection of the sterile field.

Recirculating flow regions are evident near the corners and lower parts of the room, especially around 0.5–1.5 m from the floor and close to the sidewalls, where velocities drop below 0.03 m·s−1. Such low-velocity zones could trap contaminants and should be minimised by optimising diffuser placement or exhaust locations.

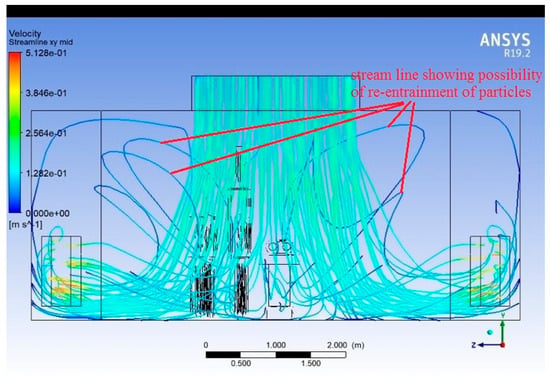

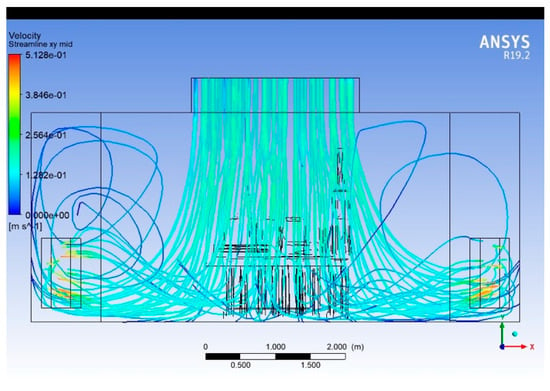

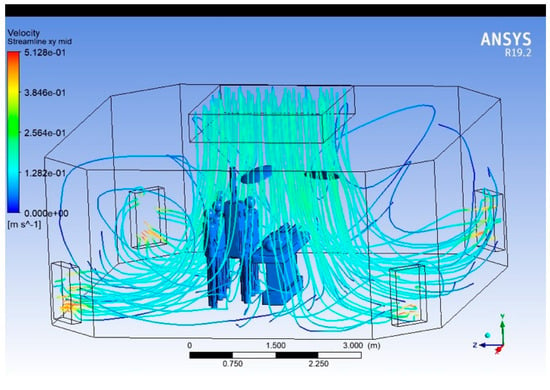

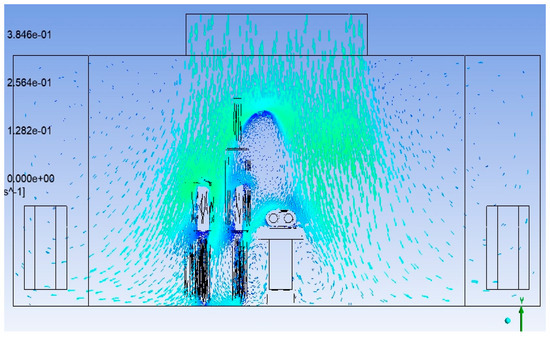

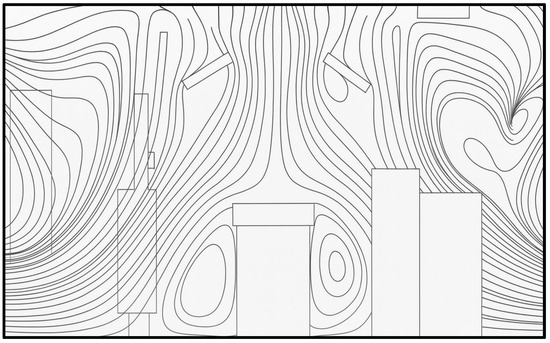

Streamlines

Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13 present the 3D streamlines tracing the path of airflow particles throughout the operating room volume. Streamlines reveal the flow continuity, circulation zones, and possible entrainment or re-entry paths.

Figure 11.

Streamlines (plane along the width of the room).

Figure 12.

Streamlines (plane along the length of the room).

Figure 13.

Streamlines (three-dimensional).

In regions directly under the supply diffusers, streamlines are largely vertical and aligned, indicating stable laminar flow. As streamlines approach surgical lights and mannequins, they bend, diverge, or form loops, indicating disrupted paths and recirculation. Multiple recirculating eddies are visible near the head and foot of the surgical table, and in regions outside the central laminar stream. Some streamlines show re-entry toward the central sterile zone, raising concerns about contaminated air looping back.

The streamline visualisation makes it evident that the OR airflow design is susceptible to backflow, particularly around obstructions. Zones away from central diffusers show stagnant or poorly directed flow, requiring rebalancing of air delivery. Introducing aerodynamic shaping of overhead fixtures or adding local vertical airflow reinforcements could improve streamline coherence. Simulation-guided positioning of HVAC elements could help eliminate undesirable loops.

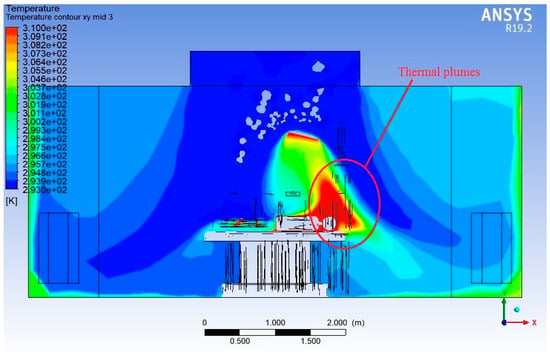

- Temperature

The contour plot in Figure 14 shows the temperature distribution on a vertical plane running along the length of the operating room, intersecting the centre of the surgical table. It helps assess how temperature varies from the ceiling to the floor and across the domain due to thermal loads.

Figure 14.

Temperature contour plot (Lengthwise).

Near the ceiling, the air is at its coolest, consistent with the supply of conditioned air meant to maintain a sterile and thermally controlled environment. As this air travels downward, the temperature increases due to various heat sources, such as the following:

Surgical lights (160 W and 180 W).

Human mannequins (each dissipating ~75 W).

Other elements in the room, like the surgical table and electronic devices.

The temperature within the OR varies from 293 K (20 °C) near the air inlets and floor regions to 310 K (37 °C) near localised heat sources. This corresponds to a temperature difference of approximately 17 K, reflecting thermal gradients generated by internal heat loads described above.

Above the mannequins, especially the patient and standing personnel, vertical thermal plumes are clearly visible. These plumes cause buoyant upward airflow, which interferes with the intended downward laminar flow and may carry particles back upward toward the sterile zone—a major sterility risk. The contour shows localised hot zones rising upward above heat sources, confirming the disruptive effect of thermal buoyancy.

The figure reveals vertical stratification—cooler zones near the floor and progressively warmer layers near the ceiling in undisturbed regions. However, in occupied zones, the stratification breaks down, and temperature becomes more uneven, with recirculating warm air.

The temperature field highlights the need to control thermal plumes in operating rooms by

Optimising equipment placement and minimising radiant heat sources directly over the surgical site.

Enhancing air velocity or using localised cooling to overpower buoyancy-driven disturbances.

Return diffuser design and positioning could also be improved to capture rising warm air more effectively, especially around the lights and personnel.

The temperature contour is plotted (Figure 15) on a vertical plane along the width of the operating room, intersecting the centreline of the surgical table. It provides insights into lateral temperature variations and thermal stratification across the cross-section.

Figure 15.

Temperature contour plot (Widthwise).

The lowest temperatures are observed near the supply diffuser region at the ceiling, where conditioned air enters. As the air moves downward and interacts with thermal loads (lights, mannequins, etc.), its temperature increases.

Localised high-temperature regions near the surgeon and operating lights indicate thermal recirculation zones, with temperatures exceeding 305 K (≈32 °C). These zones can potentially disturb laminar flow and must be controlled through diffuser redesign or optimised lighting ventilation.

Rising warm air due to buoyancy contributes to upward secondary flows, which oppose the intended laminar downward motion. This conflict of direction between forced convection (downward) and natural convection (upward) may disturb sterile airflow across the table width.

Localised cooling near thermal hotspots and strategic placement of return vents at the ceiling level may help mitigate plume re-entry. Proper thermal load distribution in the OR is essential to preserve temperature uniformity and laminar airflow.

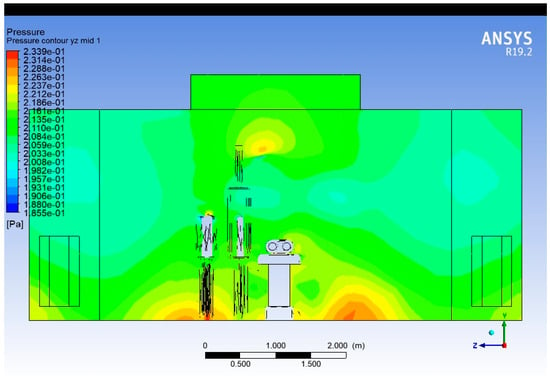

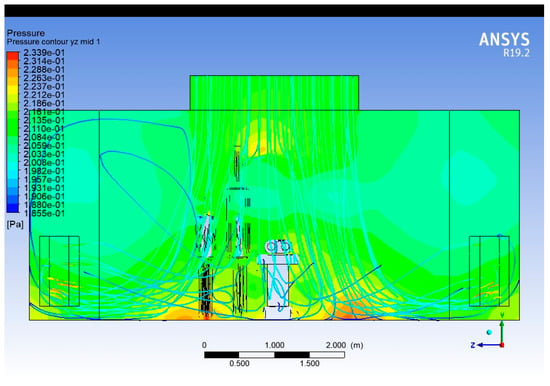

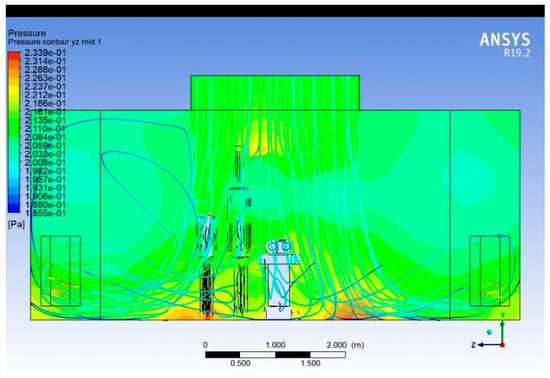

- Pressure Variation

The pressure contour shown in Figure 16 is taken along the length of the operating room, through the vertical midplane of the surgical table. It shows how static pressure varies longitudinally due to ventilation dynamics and obstruction effects. Static pressure shows a gradient, typically where higher-pressure at upstream and lower-pressure in the downstream side of the flow near the returns diffusers.

Figure 16.

Pressure contour plot (Lengthwise).

The total static pressure within the OR varies between 0.2005 Pa and 0.2305 Pa, indicating a controlled low-pressure gradient across the room. The difference of approximately 0.03 Pa demonstrates a stable and well-balanced airflow field.

The highest pressure region (≈0.230 Pa) is located just below the ceiling diffusers and above the surgical table. This corresponds to the supply air jet impingement zone, where dynamic pressure from the high-velocity incoming air increases local static pressure.

Obstructions like lights and mannequins cause localised pressure changes, with minor pressure recovery and drop zones downstream of these elements. Low-pressure pockets near return vents create suction zones, which may unintentionally draw contaminated air toward the sterile field.

Maintaining a slight positive pressure differential in the surgical field is critical for preventing external contamination. These contours can guide HVAC engineers in tuning flow rates and balancing diffuser pressure to preserve this differential.

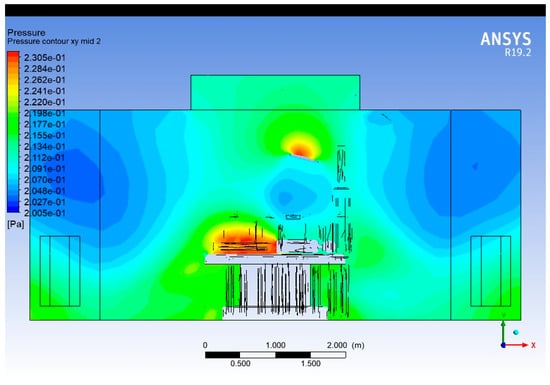

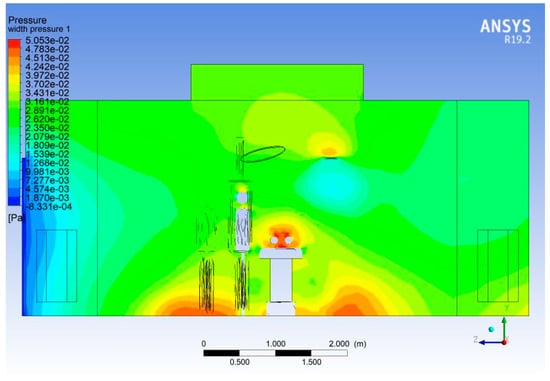

The pressure plot in Figure 17 shows pressure distribution on a cross-sectional vertical plane along the width of the operating room, bisecting the surgical table. As with the Lengthwise plot, high-pressure regions are observed beneath supply diffusers. Obstructions and walls cause pressure gradients across the width, with an asymmetrical distribution being present due to layout constraints and flow deflections.

Figure 17.

Pressure contour plot (Widthwise).

Pressure imbalance across the width suggests that airflow is not equally distributed, which may favour lateral flow or recirculation, undermining the sterility of the central region. A better symmetry in diffuser design and avoiding large lateral pressure gradients will help maintain uniform airflow.

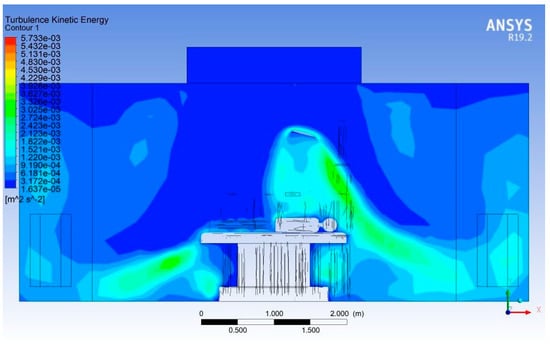

- Turbulent Kinetic Energy Distribution

Figure 18 presents the simulated turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) field within the operating room under steady-state operating conditions. The TKE values range from approximately 1.6 × 10−5 to 5.7 × 10−3 m2/s2, indicating significant spatial variation in turbulence intensity driven by the ventilation configuration, thermal plumes, and obstructions around the operating table.

Figure 18.

Turbulent kinetic energy distribution.

The core laminar region beneath the supply diffuser, directly above the patient zone, exhibits TKE levels below 5 × 10−4 m2/s2, confirming that the vertical airflow remains largely undisturbed in this protected region. This low-TKE zone is essential for reducing entrainment of contaminated air into the surgical field.

A distinct high-TKE band (≈ 3 × 10−3 to 5 × 10−3 m2/s2) appears on the right side of the operating table, coinciding with the upward buoyant plume generated by equipment heat loads and the patient’s body. This plume produces shear-driven turbulence as it interacts with the incoming downward flow. The location and intensity of this zone indicate a potential pathway for upward transport of particles toward the periphery of the sterile field.

At floor level, near the base of the operating table, moderate TKE levels of 1 × 10−3 to 2 × 10−3 m2/s2 are observed. These values correspond to recirculation pockets commonly formed around large geometrical obstructions. Although they do not directly interact with the surgical zone, such recirculation regions can increase particle residence times near the floor and should be minimised through improved exhaust placement.

The sidewalls show predominantly low TKE (<1 × 10−3 m2/s2), confirming that the ventilation layout successfully confines higher turbulence to localised regions rather than the full room volume. However, the elevated TKE region near the right-hand wall indicates entrainment of airflow toward the exhaust, suggesting asymmetry in the flow distribution that may merit optimisation.

A summary of TKE distribution at salient points is given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Statistical distribution of turbulent kinetic energy in the simulated operating room.

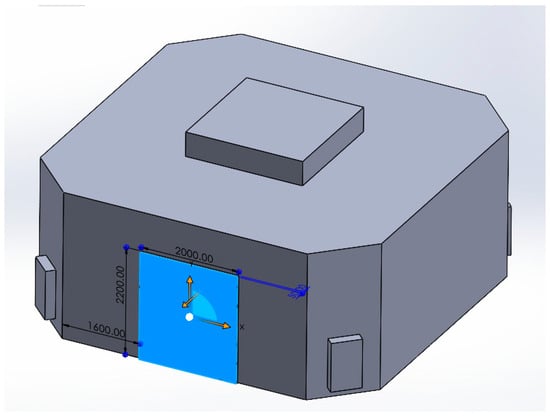

- Effect of door opening

The operating rooms are normally maintained at a relatively high pressure—at least 2.5 Pa [23]—with respect to the adjacent areas to avoid any possible infiltration of air and contaminants [24]. The doors of the operating rooms are normally open towards a sterile corridor associated with the surgical room complex. In the normal course of a procedure, the doors of the operating rooms are kept closed. However, the operation of the doors may become a necessity in instances such as movement of surgical crew, equipment and stationery. The pressure and velocity variation during opening of doors shows an asymmetry, especially in the Widthwise section.

Opening the door causes the average internal static pressure to drop by approximately 0.18–0.20 Pa, corresponding to a relative reduction of 80–85% compared to the closed-door condition. This indicates a significant breach in the positive pressurisation barrier that normally prevents the inflow of contaminated air. Under closed-door conditions, the pressure field is uniform and symmetric, with the highest pressure near the ceiling diffusers (~0.233 Pa), gradually decreasing toward the exhausts (~0.185 Pa).

The door in its fully open condition is modelled as an opening—pressure outlet—with 2 m width and 2.2 m height (Figure 19). Figure 20 and Figure 21 show the pressure asymmetry due to the door opening.

Figure 19.

Door opening on the computational domain.

Figure 20.

Symmetric distribution of the static pressure while the door is closed.

Figure 21.

Pressure asymmetry on door opening.

- Validation Methodology

Due to ethical constraints, restricted access to operational hospital environments, and the high cost of setting up a full-scale mock operating room, experimentation could not be conducted in the present study.

To ensure the reliability of the numerical predictions, the simulation results were validated against results from published articles. Validation focused on airflow velocity profiles and temperature distributions within the OR. The predicted airflow patterns exhibited good qualitative agreement with the references. This consistency confirms that the developed CFD model accurately captures the flow and thermal characteristics of the operating room, making it suitable for further analysis of airflow optimisation.

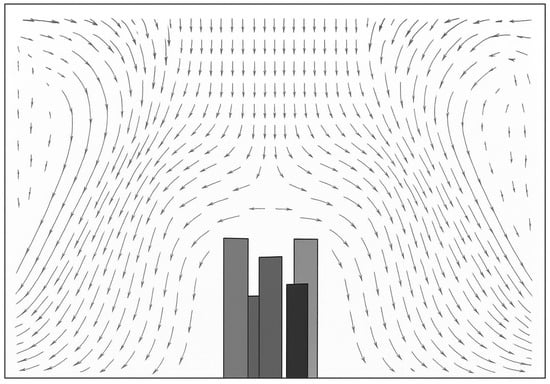

Husain et al. [25], in their research paper, have carried out a similar CFD study, mainly focusing on thermal comfort. The study uses a simpler geometry without surgical pendant and lights. The velocity vector plot in the present study (Figure 22) follows a similar pattern as (Figure 23), except for the disturbances created by the surgical lights. The eddy formation at corners outside the sterile flow field follows the same pattern.

Figure 22.

Velocity vector plot in the present study.

Figure 23.

Velocity vector plot at 0.35m·s−1 supply velocity (redrawn for validation) [25].

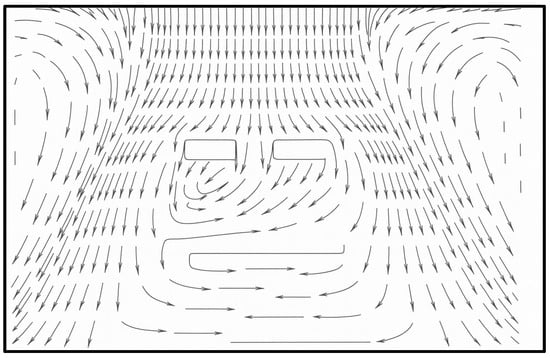

The CFD study by Mohamed et al. [26] (Figure 24) with a single laminar diffuser placed centrally with two return grills near the floor, comparable to our layout, shows a similar downward flow pattern inside the sterile LAF zone. This study was mainly focusing on thermal comfort, and the difference in the profile of surgical lights causes a significant variation in the turbulence in this region.

Figure 24.

Velocity vector plot (redrawn for validation) [26].

A similar diffuser arrangement—with a ceiling central laminar flow supply diffuser and lower level return grills at two opposing walls instead of four corners—was used by Liu et al. [27] in their attempt to find the effect of thermal plumes caused by human beings. The mannequins are arranged on both sides of the surgical table. The velocity vector plot shown in Figure 25 shows a similar pattern except for the absence of surgical lights. The circulating flow at the upper level of the room outside the LAF region is visible in the plot.

Figure 25.

Velocity vector plot (redrawn for validation) [27].

An interesting aspect that can be noted in the numerical study conducted by Nan Hu et al. [28] is the shifting of the recirculating region from the top corner of the room to the bottom corners. The velocity vector plots are not available with this study and, instead, the streamlines (Figure 26) are provided. The OR under study uses uni-directional flow inlets at the ceiling instead of a laminar flow diffuser that was used for our study.

Figure 26.

Streamline distribution with upper level exhaust (redrawn for validation) [28].

4. Conclusions

A CFD simulation of a full-scale, realistic surgical operating room was carried out using ANSYS Fluent and SolidWorks. The effectiveness of laminar airflow in the presence of common OR obstructions, the influence of thermal plumes and room geometry on flow stability, and pressure and temperature distributions throughout the domain were investigated.

The following conclusions can be drawn from the study:

The downward supply jet from the ceiling diffusers maintains a velocity between 0.18 and 0.21 m·s−1, which falls within the typical design range of 0.15–0.25 m·s−1 for ultra-clean surgical zones. This ensures effective removal of airborne particles and microbial contaminants from the critical operating field.

As the air descends and spreads over the surgical table, the velocity reduces to 0.06–0.09 m·s−1, promoting minimal turbulence while maintaining sufficient sweeping action across the sterile field. These results suggest that the airflow configuration provides a controlled unidirectional stream over the patient and surgical staff, thus minimising cross-contamination risks.

The observed recirculation zones near the sidewalls and lower boundaries correspond to low-velocity regions (<0.03 m·s−1), which, although typical in room-scale flows, should be minimised by optimising exhaust placement or diffuser design to prevent the accumulation of contaminants. The velocity symmetry about the room’s centreline indicates a well-balanced diffuser performance, supporting uniform environmental control.

The cold air supplied from the ceiling diffusers establishes a stable, downward laminar flow that cools the surgical zone while sweeping contaminants toward the exhausts. A temperature of 293–295 K (20–22 °C) at the diffuser outlets aligns with ASHRAE 170 [23] and ISO 14644 cleanroom ventilation criteria, ensuring a general thermal comfort condition.

The presence of a thermal plume above the patient, where temperatures rise to 305–310 K, is consistent with expected convective behaviour due to patient metabolism and surgical lighting.

A temperature gradient within 1.5 K confirms the presence of thermal stratification but in a controlled manner, still maintaining sterile air stability in the critical zone. However, minor hot spots detected above lighting fixtures highlight potential areas for localised ventilation enhancement—such as integrating laminar diffusers around the lighting array or using thermally controlled air curtains.

The nearly symmetrical pressure field further implies that diffuser configuration and exhaust placement are properly balanced, contributing to uniform air delivery and minimised stagnation zones. Localised high-pressure regions around equipment and lighting structures are acceptable as long as they do not disrupt the downward laminar airflow, and their influence can be mitigated through diffuser design optimisation.

The simulation results indicate that the presence of surgical lighting fixtures significantly disrupts the intended unidirectional airflow, particularly in the critical zone directly above the surgical table. Streamline analysis further reveals the formation of localised recirculation regions and flow re-entry into the sterile field, primarily near the corners and around large equipment surfaces. Although the central region beneath the ceiling diffusers sustains a relatively stable laminar flow pattern, flow uniformity deteriorates rapidly beyond this confined core area.

The TKE analysis reveals that the largest contribution of turbulence is created by the surgical light fitting (1 × 10−3–5.7 × 10−3 m2/s2) caused by upward buoyant flow of the thermal plume interacting with supply air and the obstruction created by the light.

Additionally, door opening events were found to induce noticeable pressure imbalances, leading to transient disturbances in the established airflow structure. These findings suggest that enhancements in operating room ventilation design can be achieved through the following:

- Optimisation of Surgical Lighting Design

Surgical lights should be designed to minimise obstructions to the airflow within an operating room. LED-based lighting systems featuring annular openings have demonstrated superior aerodynamic performance by reducing flow disturbance.

- 2.

- Positioning of Surgical Lights

The surgical lighting units should be positioned to avoid direct placement above the surgical site, thereby reducing potential interference with the laminar airflow pattern over the sterile field.

- 3.

- Minimisation of Heat Dissipation in the Critical Flow Field

Heat generation within the critical airflow zone should be minimised. This can be achieved by relocating the LED driver and associated control circuitry outside the laminar flow field, thus preventing unwanted thermal disturbances.

- 4.

- Control of Door Operations in the Operating Room

Operating room doors should remain closed at all times except when absolutely necessary. When door opening is unavoidable, the duration should be kept to a minimum to limit disruption of the controlled airflow environment.

- 5.

- Enhancement of Scavenging through Exhaust Placement

The strategic installation of additional high-level exhaust vents can mitigate the formation of eddies near the ceiling outside the laminar airflow zone. This configuration promotes effective particle scavenging and reduces the likelihood of re-entrainment into the sterile field.

Such design modifications are expected to improve the stability of the laminar airflow field, enhance contaminant control, and strengthen compliance with cleanroom and healthcare ventilation standards.

Author Contributions

V.V.K.: conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, and preparation of the original draft of the paper. C.M.: methodology and review and editing of the paper. A.P.: validation and review and editing of the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study can be made available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Whyte, W.; Hodgson, R.; Tinkler, J. The importance of airborne bacterial contamination of wounds. J. Hosp. Infect. 1982, 3, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiletzari, S.; Barbouni, A.; Kesanopoulos, K. Impact of microbial load on operating room air quality and surgical site infections: A systematic review. Acta Microbiol. Hell. 2025, 70, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brohus, H.; Balling, K.D.; Jeppesen, D. Influence of movements on contaminant transport in an operating room. Indoor Air 2006, 16, 356–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASHRAE. HVAC Design Manual for Hospitals and Clinics; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.J.; Permana, I.; Rakhsit, D.; Azizah, R.S. Thermal Performance Improvement and Contamination Control Strategies in an Operating Room. J. Adv. Therm. Sci. Res. 2021, 8, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.L.; Hanssen, A.D. Principles of a Clean Operating Room Environment. J. Arthroplast. 2007, 22, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Li, J. The effect of type of ventilation used in the operating room and surgical site infection: A meta-analysis. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020, 42, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H.; Kim, M.; Song, Y.J. A systematic review of operating room ventilation. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 43, 102577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Wang, Q.; Li, X.; Zhang, T.; Rastogi, S. Laminar airflow ventilation systems in orthopaedic operating room do not prevent surgical site infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023, 18, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, C.; Hott, U.; Sohr, D.; Daschner, F.; Gastmeier, P.; Rüden, H. Operating Room Ventilation with Laminar Airflow Shows No Protective Effect on the Surgical Site Infection Rate in Orthopedic and Abdominal Surgery. Ann. Surg. 2008, 248, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnankutty, V.V.; Muraleedharan, C.; Palatel, A. Analysis of Disruption of Airflow and Particle Distribution by Surgical Personnel and Lighting Fixture in Operating Rooms. Fluids 2025, 10, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çoşgun, A.; Koyun, T. Assessment of indoor air quality at a university hospital using CFD and GIS. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 2071–12082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhalaf, M.; Ilinca, A.; Hayyani, M.Y. CFD Investigation of Ventilation Strategies to Remove Contaminants from a Hospital Room. Designs 2023, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.H.; Rosario, L.; Rahman, M.M. Three-dimensional analysis for hospital operating room thermal comfort and contaminant removal. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2009, 29, 2080–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, J.; Angrick, C.; Höhn, C.; Zajonz, D.; Ghanem, M.; Roth, A.; Neumuth, T. Surgical workflow simulation for the design and assessment of operating room setups in orthopedic surgery. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2020, 20, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Daza, C.A.; Murillo-Rincón, J.; Espinosa-Moreno, A.S.; Alberini, F.; Alexiadis, A.; Garzón-Alvarado, D.A.; Thomas, A.M.; Simmons, M.J. Analysis of the airflow features and ventilation efficiency of an Ultra-Clean-Air operating theatre by qDNS simulations and experimental validation. Build. Environ. 2024, 256, 111444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, Q.; Shen, J.; Kong, Y.; Li, J. Modeling and Analysis of Operating Room Workflow in a Tertiary A Hospital in Beijing, China. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 7006–7013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memarzadeh, F.; Jiang, Z. Effect of Operation Room Geometry and Ventilation System Parameter Variations on the Protection of the Surgical Site. In Proceedings of the IAQ Conference, National Institutes of Health; 2004. Available online: https://orf.od.nih.gov/TechnicalResources/Bioenvironmental/Documents/OperationRoomGeometry_508.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Tang, Y.; Guo, B. Computational fluid dynamics simulation of aerosol transport and deposition. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. China 2011, 5, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, F.; Tacutu, L.; Croitoru, C.; Nastase, I. Numerical and experimental study for the development of an advanced model of an operating room with surgeons and patient. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Energy and Environment (CIEM), Bucharest, Romania, 19–20 November 2017; pp. 447–451. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.; Zargar, O.A.; Lin, K.Y.; Juiña, O.; Sabusap, D.L.; Hu, S.C.; Leggett, G. An experimental study of the flow characteristics and velocity fields in an operating room with laminar airflow ventilation. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 29, 101184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Menezes, G.M.; Suzuki, E.H.; Lofrano, F.C.; Kurokawa, F.A. Simple or simplistic? Sensitivity of an operating room CFD model to refinement and detailing. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 108003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE (American Society of Heating, ASHRAE Standard 170P: Ventilation of Health Care Facilities. 2017. Available online: https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/standards-and-guidelines/standards-addenda/ansi-ashrae-ashe-standard-170-2017-ventilation-of-health-care-facilities (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Oo, G.M.; Kotmool, K.; Mongkolwongrojn, M. Case Study on the design optimization of the positive pressure operating room. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, H.; Samidi, M.Z.M.; Meon, M.S. CFD analysis of thermal comfort in hospital operation room with different air distribution design and operative temperature. J. Appl. Eng. Des. Simul. 2021, 1, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, O.E.; Ahmed, A.; Abubker, M. CFD of Human Comfort and Contaminants Control in a Hospital Operating Room. J. Fluid Flow Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 11, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopps, H.; Touchie, M.F. Load shifting and energy conservation using smart thermostats in contemporary high-rise residential buildings: Estimation of runtime changes using field data. Energy Build. 2022, 255, 111644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Lans, J.; Gram, A.; Luscuere, P.; Sadrizadeh, S. Ventilation performance evaluation of an operating room with temperature-controlled airflow system in contaminant control: A numerical study. Build. Environ. 2024, 259, 111619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.