1.2.1. Current Status of Building Load Forecasting Research

Building load forecasting constitutes the foundation for energy margin assessment. In recent years, alongside the advancement of artificial intelligence technologies, significant progress has been achieved in forecasting methods for building loads. Currently, the commonly used forecasting methods mainly include traditional statistical methods, machine learning methods, and deep learning methods.

Among traditional statistical methods, Tarsitano [

5] adopted a dynamic regression model that integrates key external predictive factors into the seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average process, achieving high accuracy in both one-day and nine-day forecasts. Huang [

6] proposed combining sensor networks with Gaussian regression for building load forecasting and compared Gaussian process regression models using different covariance functions to determine the optimal one. These methods are conceptually simple and computationally efficient but show poor adaptability to nonlinear and nonstationary building load data. Within the classical framework of data dimensionality reduction in traditional statistical methods, the “similar day” approach—centered on the core assumption that “load patterns from historically similar scenarios can be transferred to the forecast day”—has been widely applied in building load forecasting. Its academic consensus and contentious focal points provide a design basis for the similar day selection model in this study. Currently, this method faces three core controversies: the first is the controversy over feature vector construction: single meteorological factors fail to capture the coupling effects of multiple factors, necessitating a balance between feature comprehensiveness and computational efficiency [

7]; the second is the controversy over similarity calculation and weight setting: methods such as Euclidean distance and gray relational analysis have been adopted, yet weight configurations mostly rely on experience, leading to strong subjectivity [

8]; the third is the limitation in applicability to complex scenarios: under scenarios like holidays or abrupt weather changes, multifactor coupling complicates load patterns, resulting in scarce similar samples and increased prediction errors in traditional methods [

9]. To address the above controversies, this study optimizes the similar day selection logic from three aspects (indicator system, weight configuration, and scenario adaptability) to enhance the reliability of selection results.

In the research on load forecasting based on machine learning, scholars have gradually improved prediction accuracy and adaptability across different scenarios through algorithmic optimization. As an early core technical framework, the artificial neural network (ANN) established a foundational paradigm for subsequent load forecasting models. In recent years, researchers have innovated its application in data-scarce environments. Li [

10] combined ANN with transfer learning algorithms to effectively address the challenge of insufficient training samples in data-driven models. The backpropagation (BP) neural network, as a classical implementation of ANN, has also been widely applied. Wang [

11] used a BP neural network for power load prediction and analysis, improving the stability of forecasting results. Soon after, support vector machine (SVM) models were introduced into load forecasting. Luo [

12] combined SVM with optimization algorithms, enhancing prediction accuracy while simplifying computation. Tang [

13] developed a support vector regression (SVR) model for three power demand control scenarios, reducing model development time and labor cost. Wang [

14] proposed a Random Forest (RF)-based model for predicting hourly electricity demand in buildings, while Sala [

15] integrated RF with the K-means clustering algorithm for load forecasting in residential buildings.

As a branch of machine learning, deep learning models offer more network layers, enabling them to extract richer information from periodic energy consumption data [

16]. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) can capture valuable information from past sequences. Fang [

17] proposed an improved singular spectrum analysis and multivariate input RNN, integrating multiple features from raw building electricity consumption time series data in Morocco. Rahman [

18] developed an RNN-based method for predicting building electricity consumption, which significantly enhanced prediction accuracy by capturing time series characteristics and provided an efficient tool for energy management in commercial and residential buildings. However, RNNs often suffer from gradient vanishing or exploding issues when handling long sequences, making it difficult to effectively capture long-term dependencies [

19]. To address this limitation, the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network was introduced to capture temporal dependencies between sequences [

20]. Zhou [

21] applied an LSTM model to predict the time series of a university library’s air-conditioning system and demonstrated superior performance in energy consumption forecasting. Sundaram [

22] employed LSTM for early prediction of residential electricity consumption, assisting in identifying energy efficiency improvement measures during early design stages. The temporal characteristics of energy consumption data greatly benefit from the LSTM model’s ability to capture time-based patterns and trends [

23]. A review of the existing literature on deep learning methods shows that the LSTM model is widely used due to its capability to process sequential data, capture long-term correlations, manage missing data, and model complex interactions [

24]. Therefore, the LSTM model is considered the optimal choice for load forecasting based on time series data.

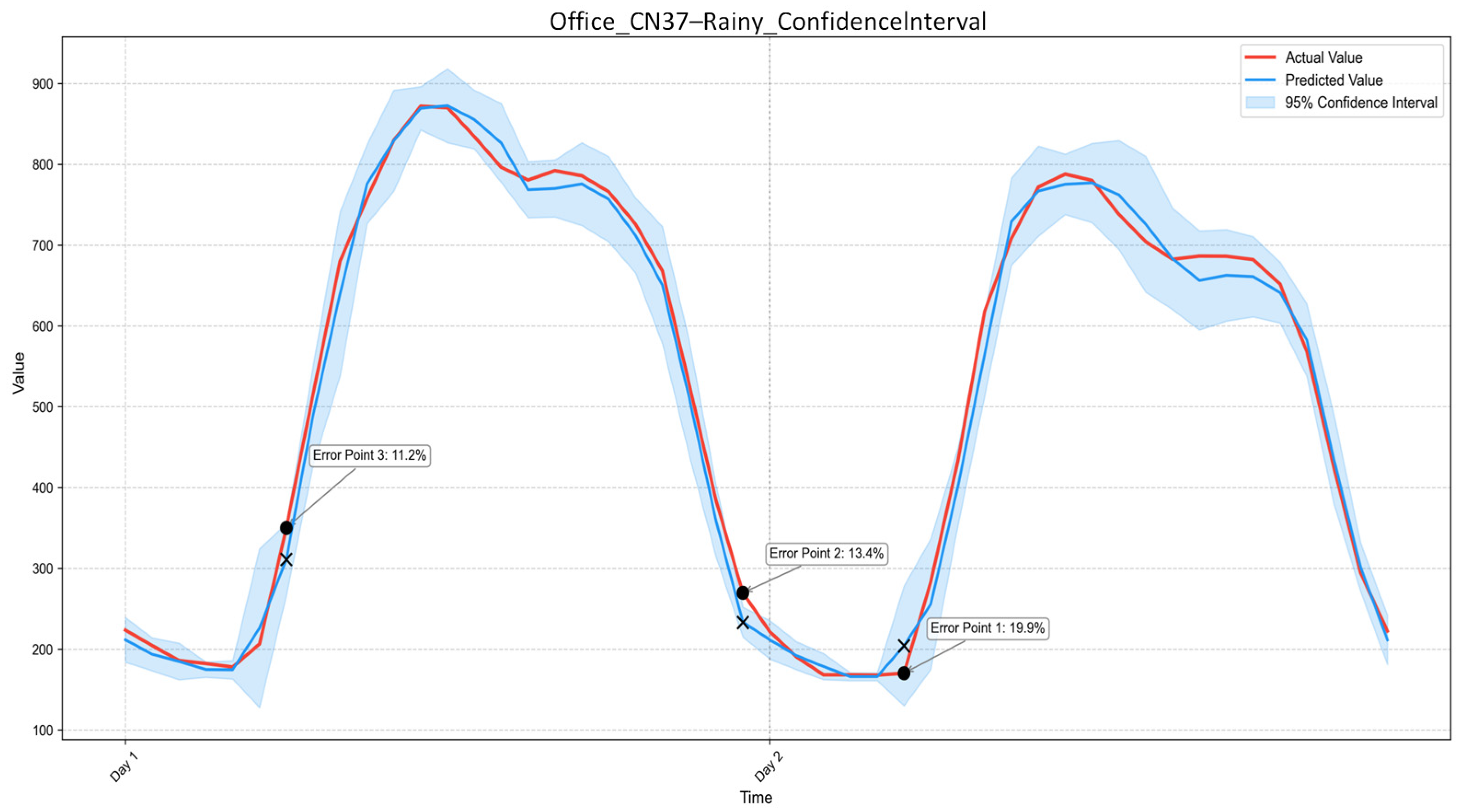

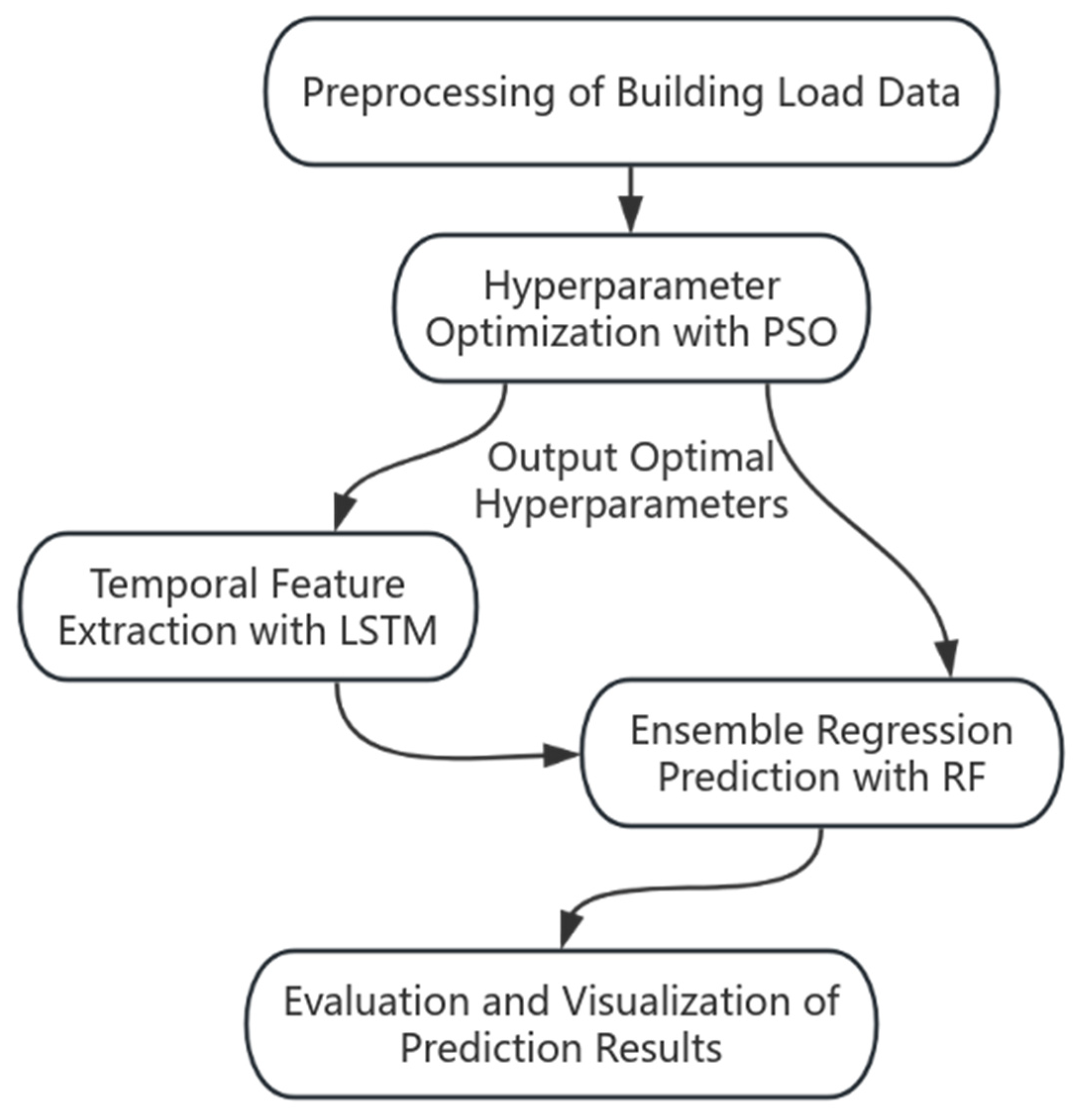

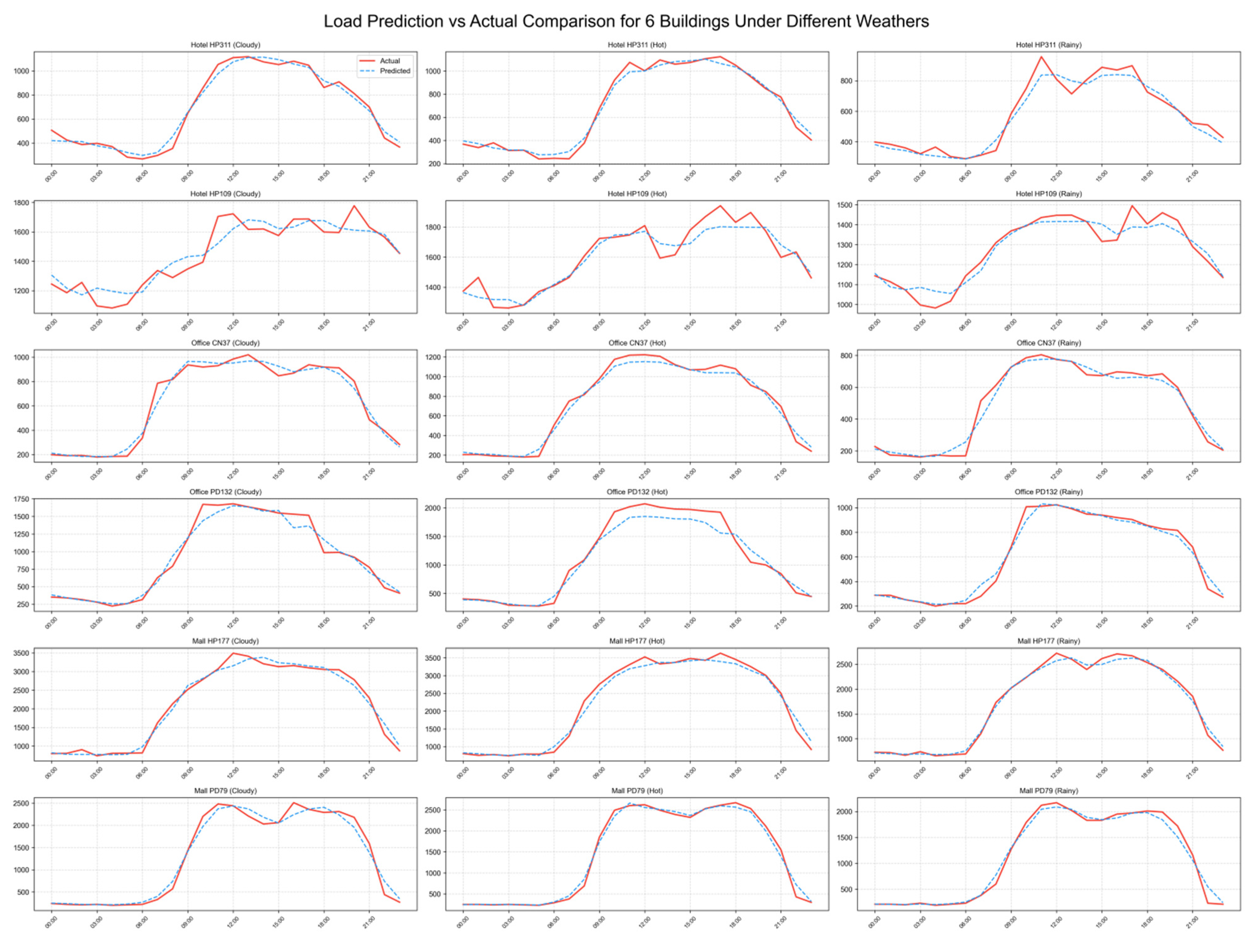

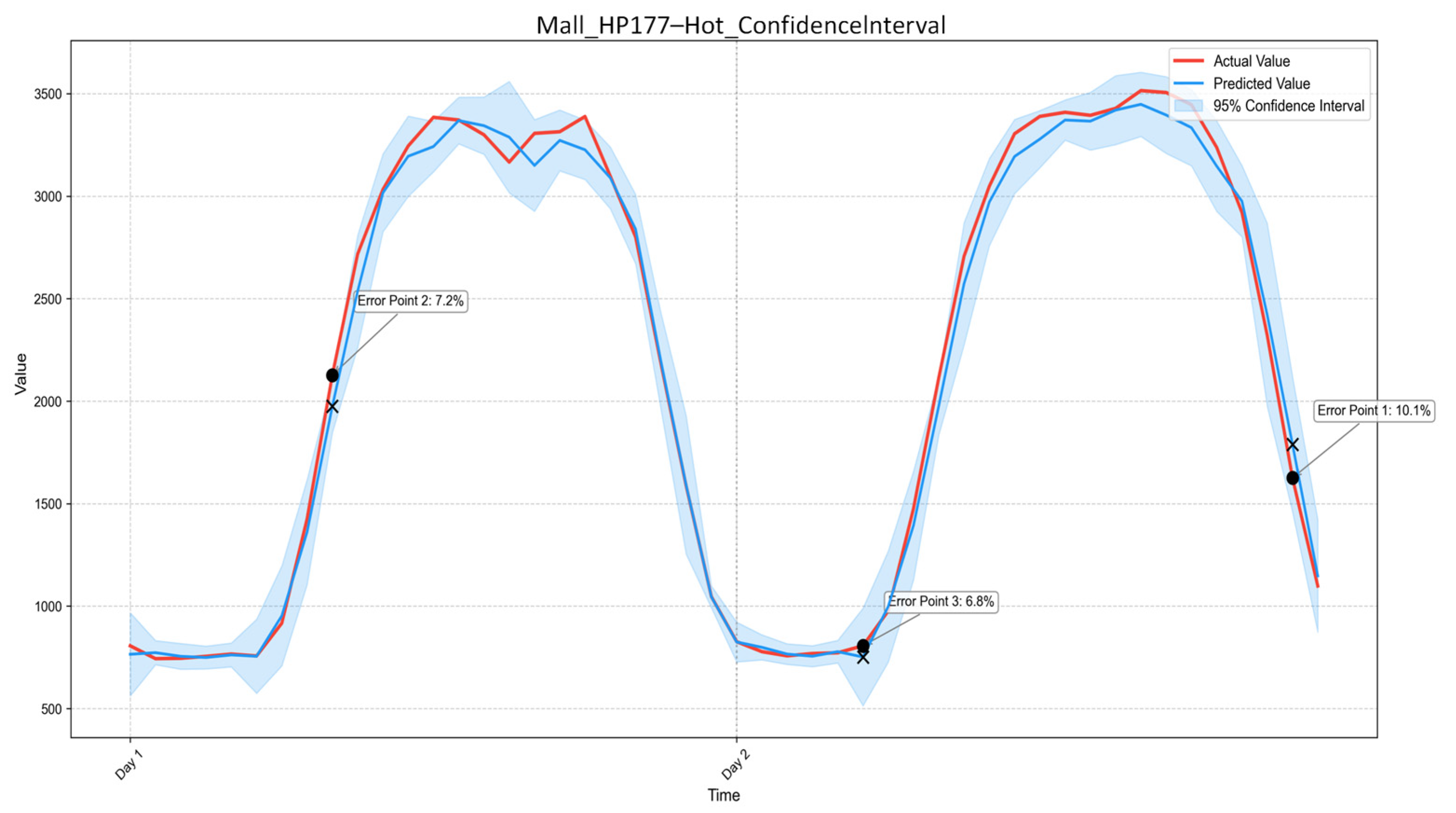

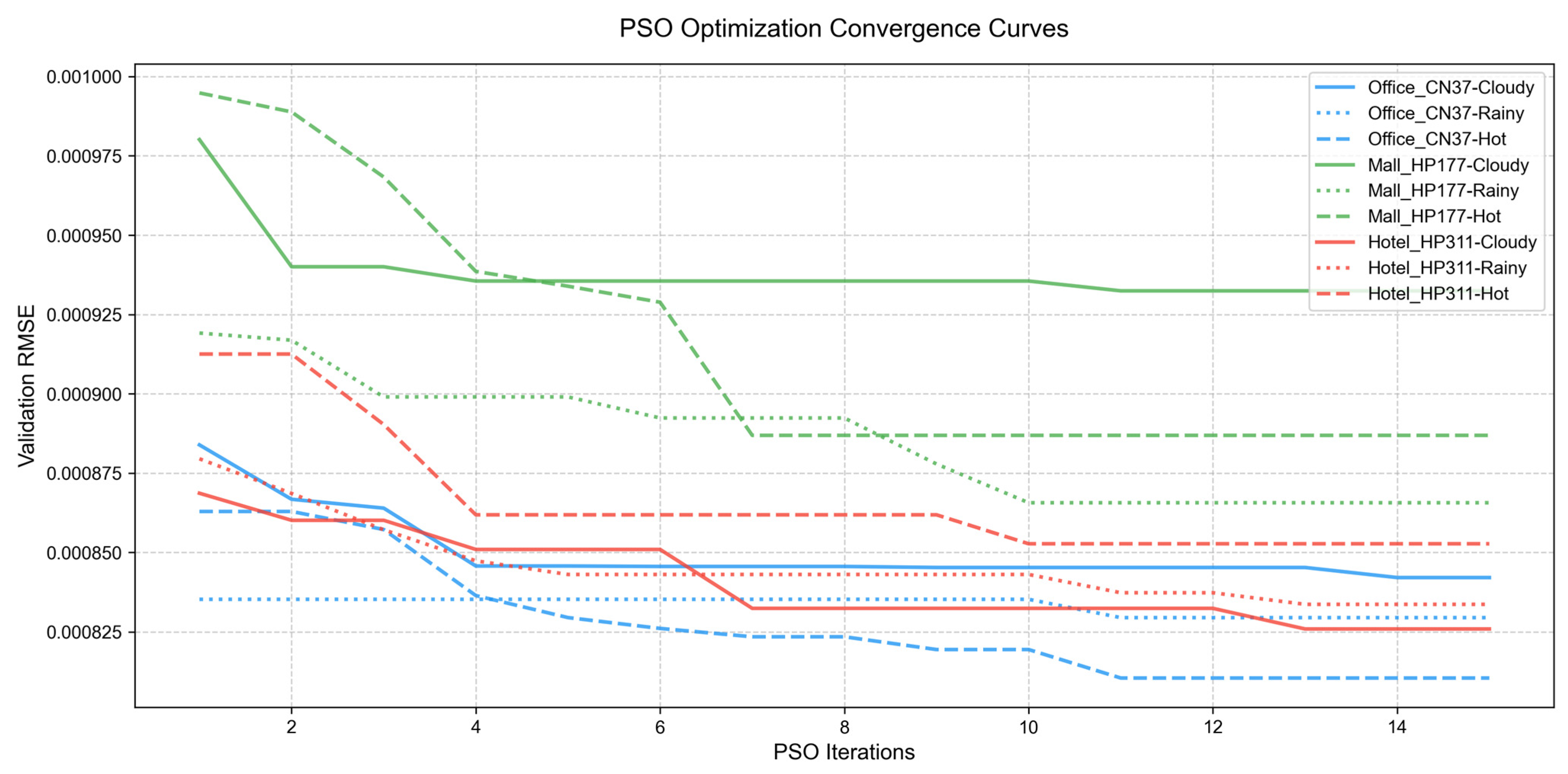

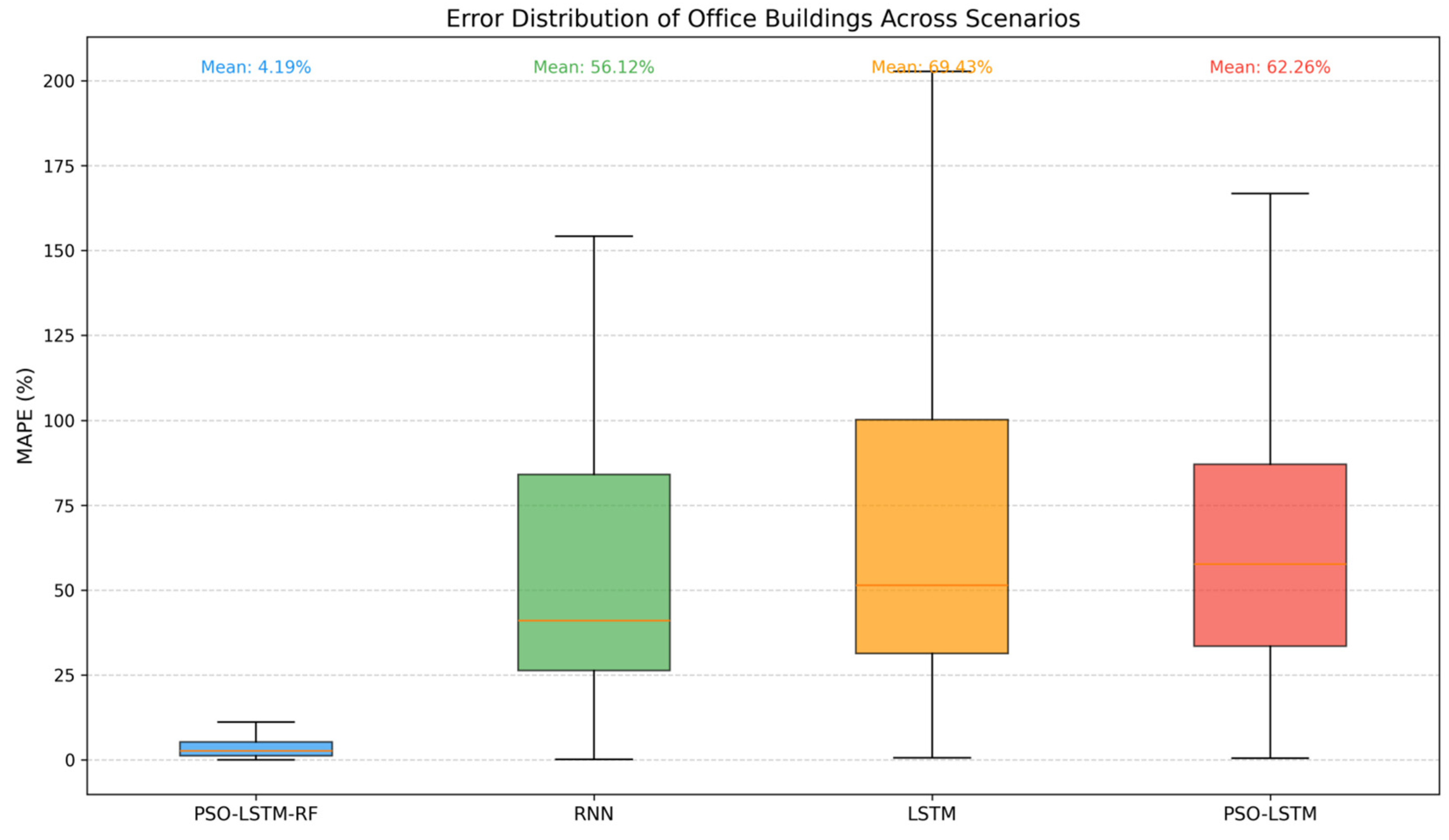

However, building energy consumption data are influenced by multiple factors, such as temporal and meteorological characteristics. A single forecasting model cannot achieve both accuracy and efficiency in this context. Therefore, this study proposes a PSO-LSTM-RF hybrid model that overcomes the limitations of a single architecture. The PSO algorithm provides global optimization, alleviating computational redundancy and overfitting risk; RF, leveraging the advantages of ensemble learning, strengthens the capture of nonlinear coupling relationships among multidimensional features such as weather and time, compensating for the LSTM’s limitations in modeling nontemporal interactions. Together, the three models form a closed loop of “temporal dependency capture–multifeature integration–adaptive parameter optimization”, retaining the LSTM’s core advantage in handling long sequences while enhancing adaptability to complex building energy characteristics through cross-model collaboration, ultimately achieving high-accuracy and low-redundancy load forecasting.

1.2.2. Current Status of Building Adjustable Margin (BAM) Assessment Research

With the transformation of modern power systems toward high renewable energy penetration and power-electronic-dominated operation, electricity market mechanisms are evolving from traditional generation-load balancing to coordinated interaction among generation, grid, load, and storage. As a major flexible resource on the demand side, public buildings play a key role in ensuring the secure and economic operation of power systems through precise utilization of their energy regulation capacity [

25,

26]. Heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems are the core components in this regard, accounting for 40.00–60.00% of total building energy consumption [

27,

28]. The load characteristics and operating patterns of HVAC systems directly determine the potential boundaries of building energy regulation. On one hand, system start–stop operations and temperature setpoint adjustments can rapidly alter energy consumption levels, forming short-term load adjustment potential. On the other hand, the coupling with a building’s passive thermal storage capacity extends the duration of adjustment, providing more stable support for grid response. Therefore, prior forecasting of building flexibility is essential for participation in electricity markets. Whether for bidding in day-ahead markets, providing ancillary services in real-time markets, or enabling precise demand-response participation, buildings must determine in advance their BAM and RD.

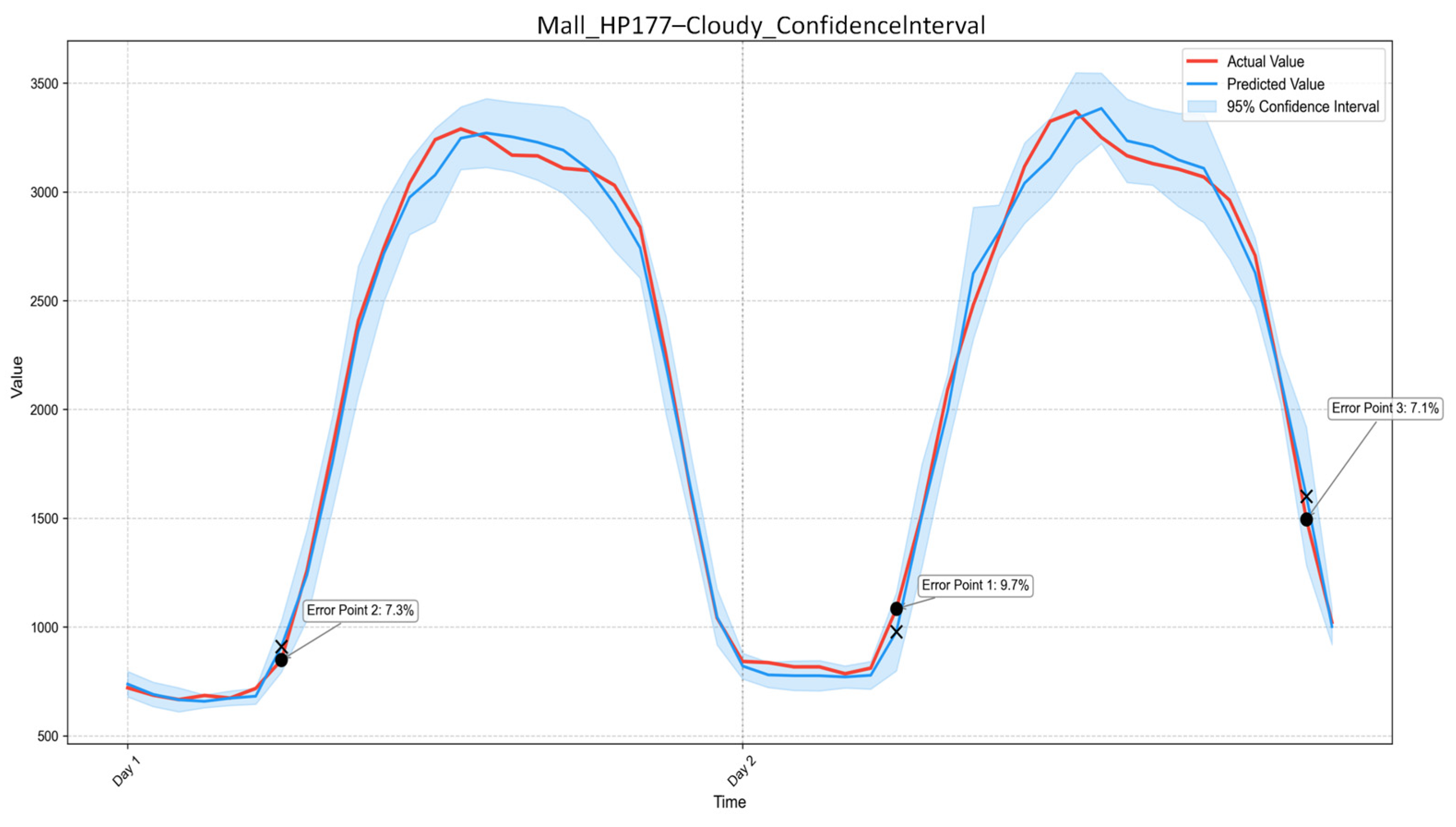

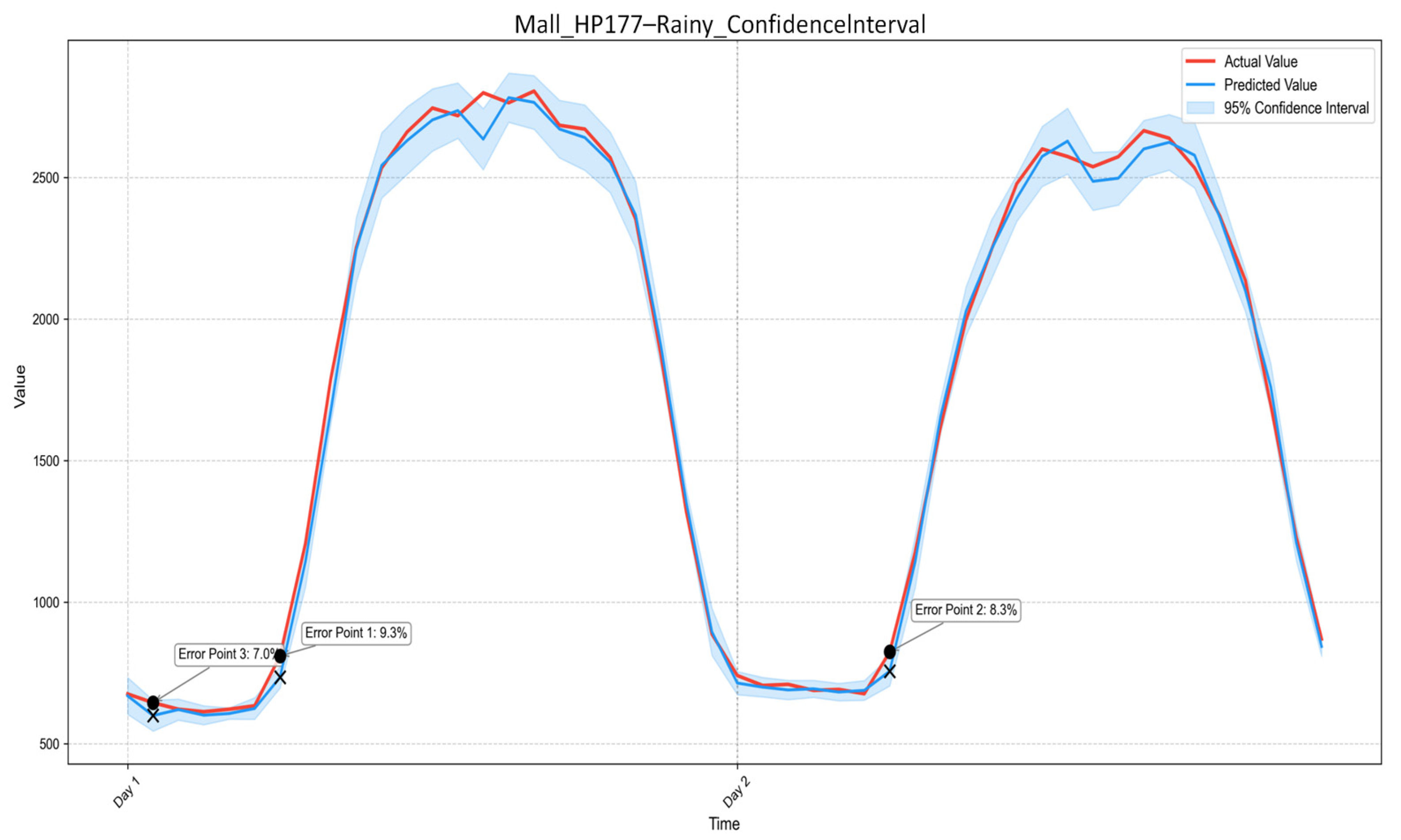

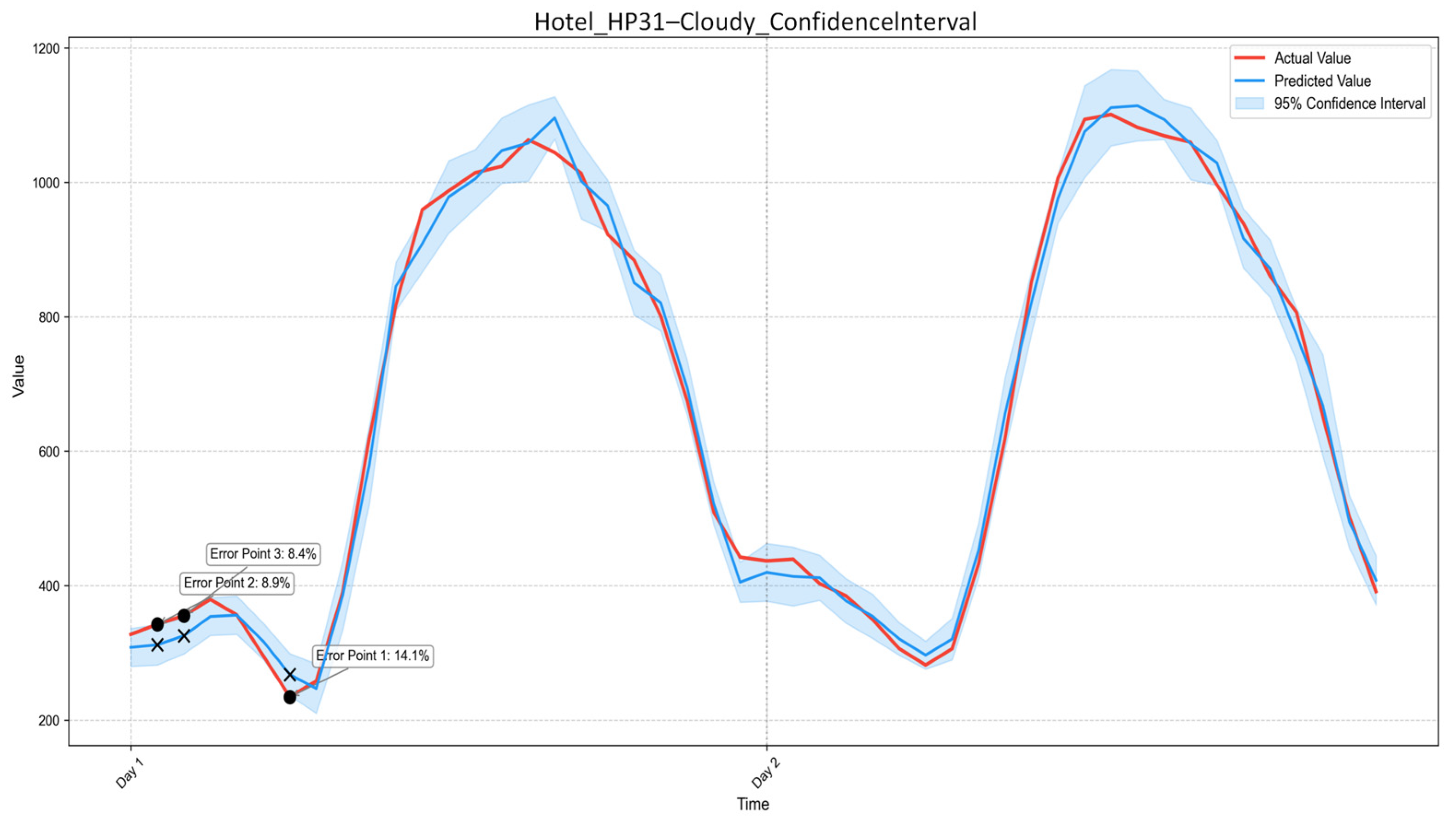

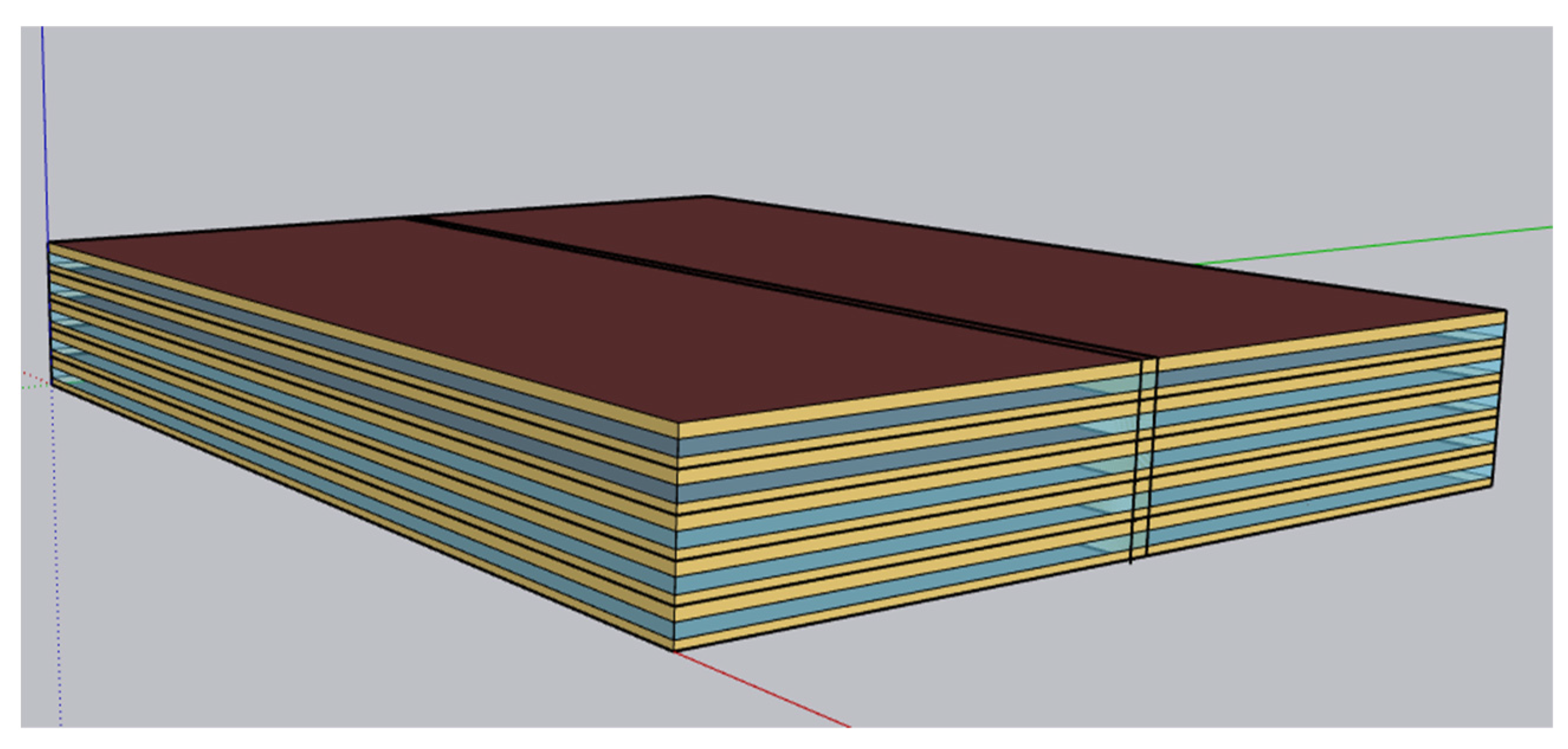

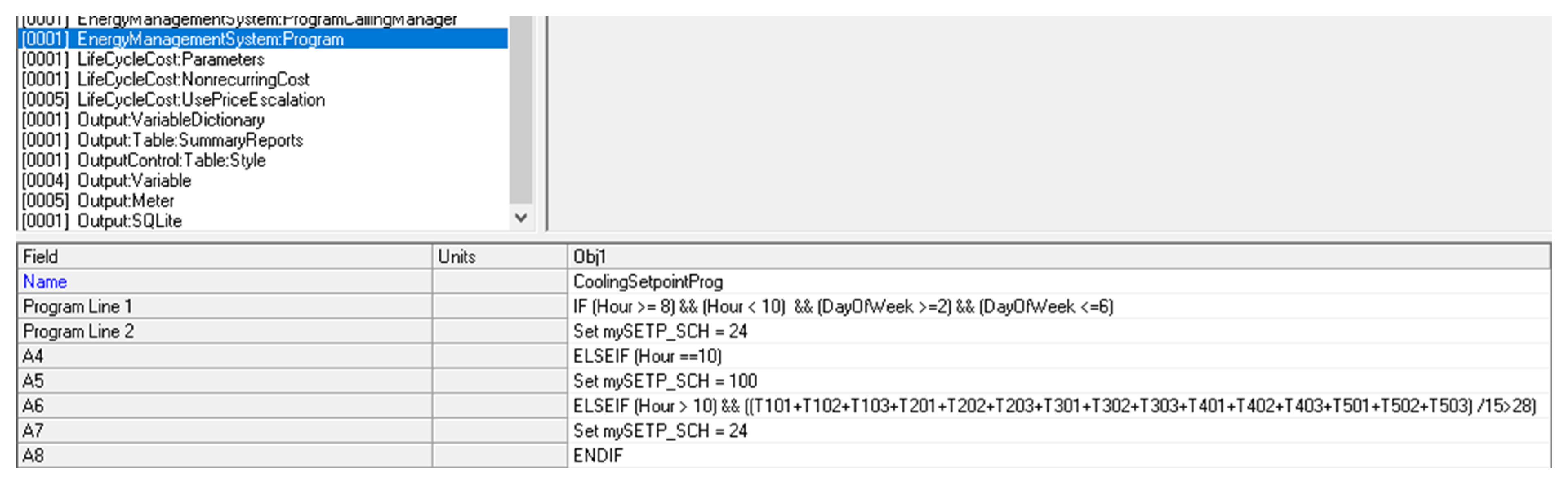

The concept of BAM proposed in this study focuses on quantifying a building’s capacity to regulate energy in both the energy and temporal dimensions—a metric not yet explicitly defined in the current research context. To consolidate existing research and clarify the foundational understanding in this domain, related studies are reviewed using widely adopted terms such as building flexibility and demand-response potential. Yin [

29] constructed detailed models of commercial and multifamily residential buildings using EnergyPlus(24.1.0), generating over 300 million data points to capture load response and thermodynamic characteristics, and fitted regression models incorporating time period, temperature setpoints, and outdoor temperature. Ding [

30] adjusted indoor temperature setpoints and introduced two indicators—electrical flexibility and energy flexibility—to compare the performance of active storage, passive storage, and temperature reset strategies in demand-response processes. Ruan [

31] analyzed how demand-response event types, thermal properties of building envelopes, and meteorological conditions affect preheating performance during the heating season, evaluating energy flexibility from the perspectives of energy efficiency, load reduction, and energy savings in a residential building in Kitakyushu, Japan. Han [

32] proposed a probabilistic model using sampling-based fuzzy analysis to account for major uncertainties, enabling rapid quantification of aggregated flexibility in building clusters under uncertain conditions. Zhu [

33] performed large-scale stochastic simulations for two common demand-response strategies, quantifying demand-response potential using metrics such as maximum response duration and maximum power reduction.

However, several limitations remain evident. First, most flexibility assessment studies rely on predefined or historical load profiles and lack predictive support that reflects future operating conditions. Second, flexibility is often quantified either in the energy dimension or the temporal dimension, rather than through a joint evaluation of adjustable margin and response duration. Third, the coupling between data-driven load forecasting and physics-based flexibility assessment has not been fully established, leading to fragmented technical chains and limited practical applicability.

To clearly distinguish existing studies from the proposed approach, a comparative analysis is presented in

Table 1, which summarizes representative research from the perspectives of load forecasting, flexibility evaluation methods, and flexibility dimensions.

As shown in

Table 1, existing studies have achieved notable progress in either high-accuracy load forecasting or detailed flexibility assessment using physical simulation. Nevertheless, these two research streams largely evolve independently. Load forecasting studies typically emphasize prediction performance without linking forecast results to executable flexibility indicators, while flexibility assessment studies often neglect predictive consistency with future operating scenarios.

Motivated by these limitations, this study proposes an integrated framework that couples data-driven load prediction with physics-based simulation through a similar-day matching mechanism, enabling the joint and realistic quantification of building adjustable margin and response duration. The main innovations and contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

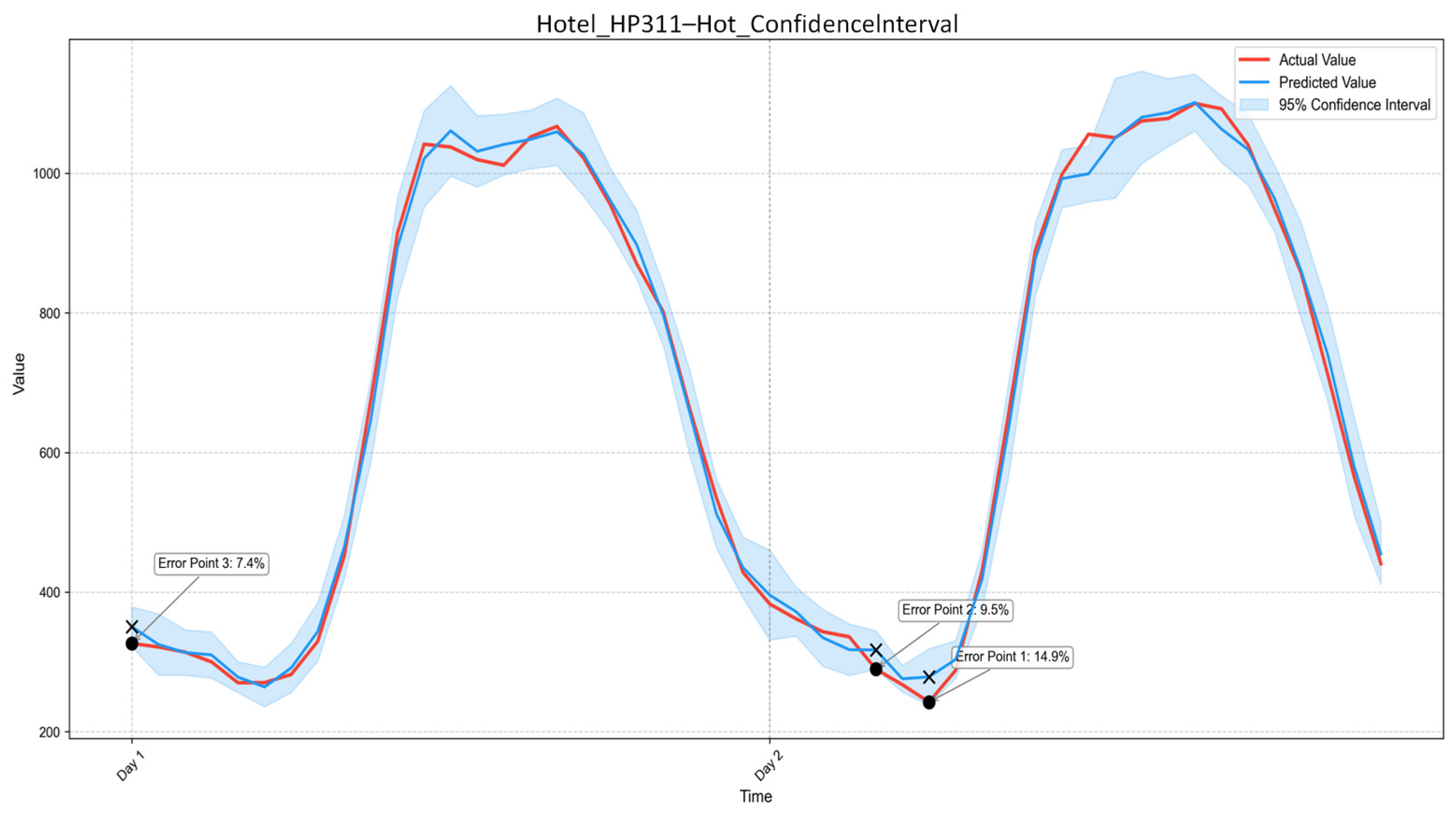

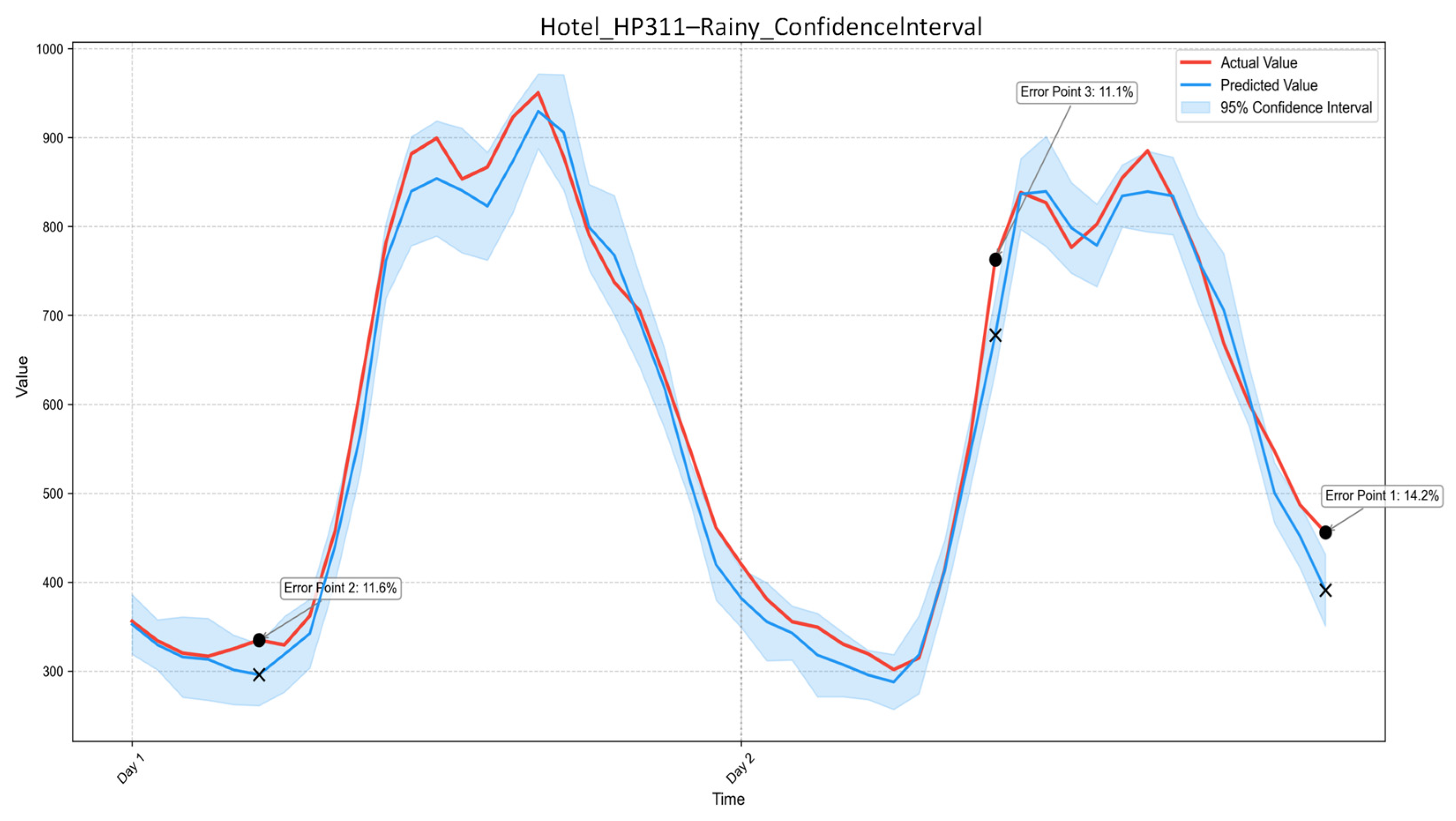

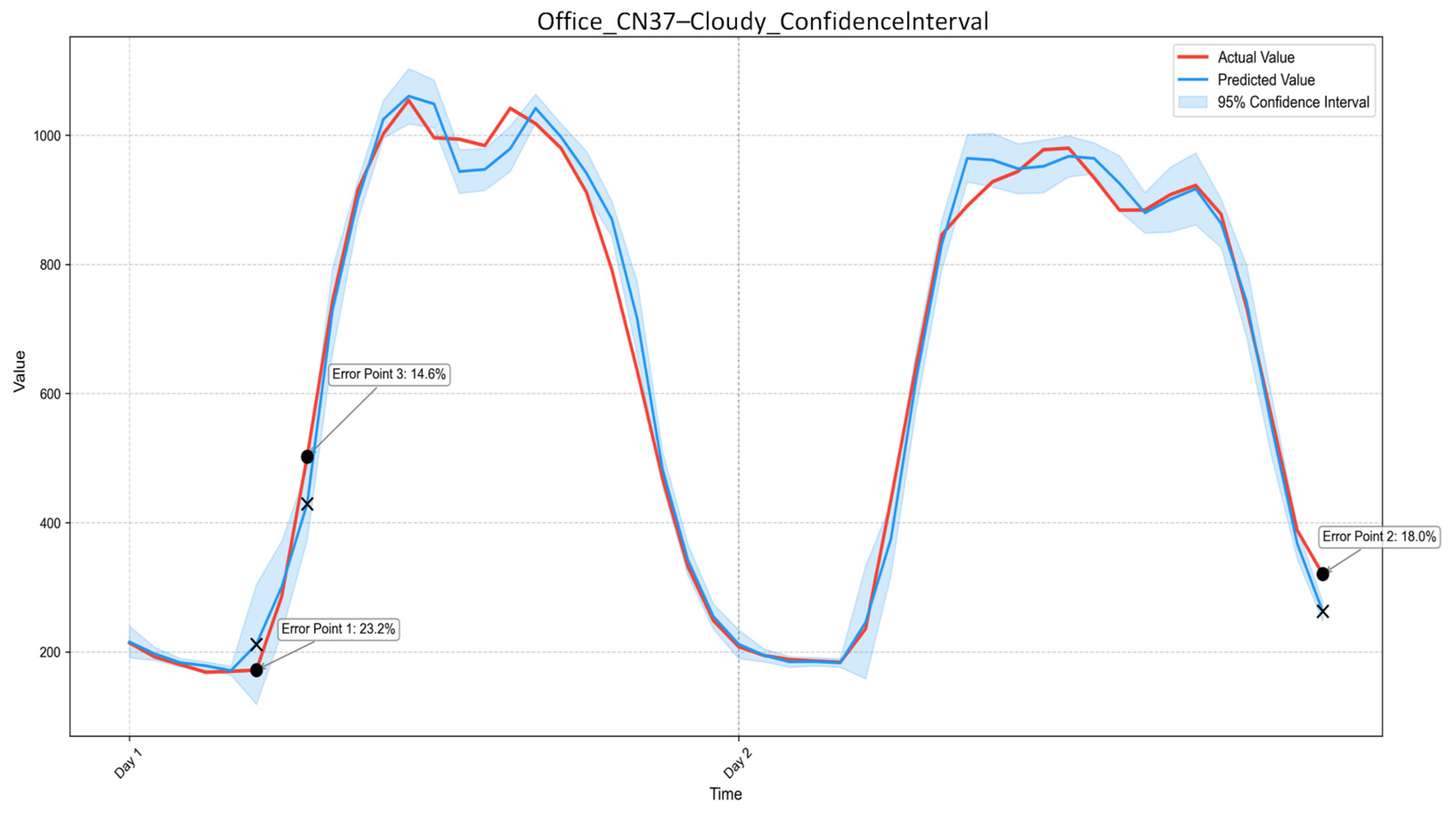

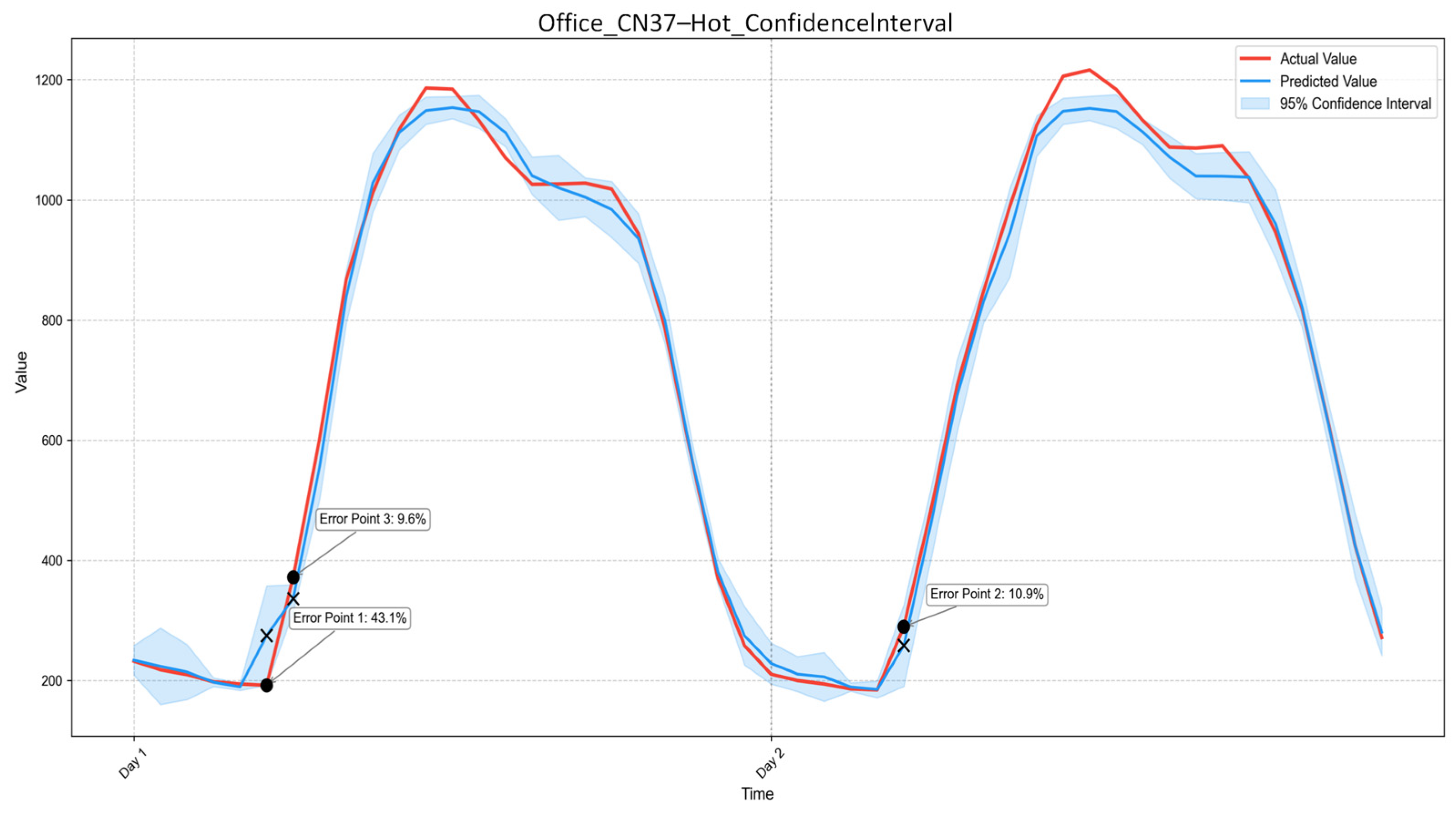

A closed-loop framework integrating load prediction and flexibility quantification is developed. Unlike existing studies that separately address building load forecasting or flexibility assessment, this study establishes an integrated technical chain that links high-accuracy data-driven load prediction with physics-based EnergyPlus simulation. By coupling prediction, similar-day matching, scenario construction, and margin calculation, the proposed framework resolves the long-standing disconnect between forecast results and practically executable flexibility indicators.

A joint and physically constrained quantification of building adjustable margin and response duration is proposed. This study explicitly defines and quantifies BAM and RD as complementary indicators in the energy and temporal dimensions, under strict indoor thermal comfort constraints. By embedding comfort limits directly into the simulation-based evaluation process, the proposed method moves beyond abstract flexibility potential and provides practically feasible flexibility boundaries for demand-response applications.

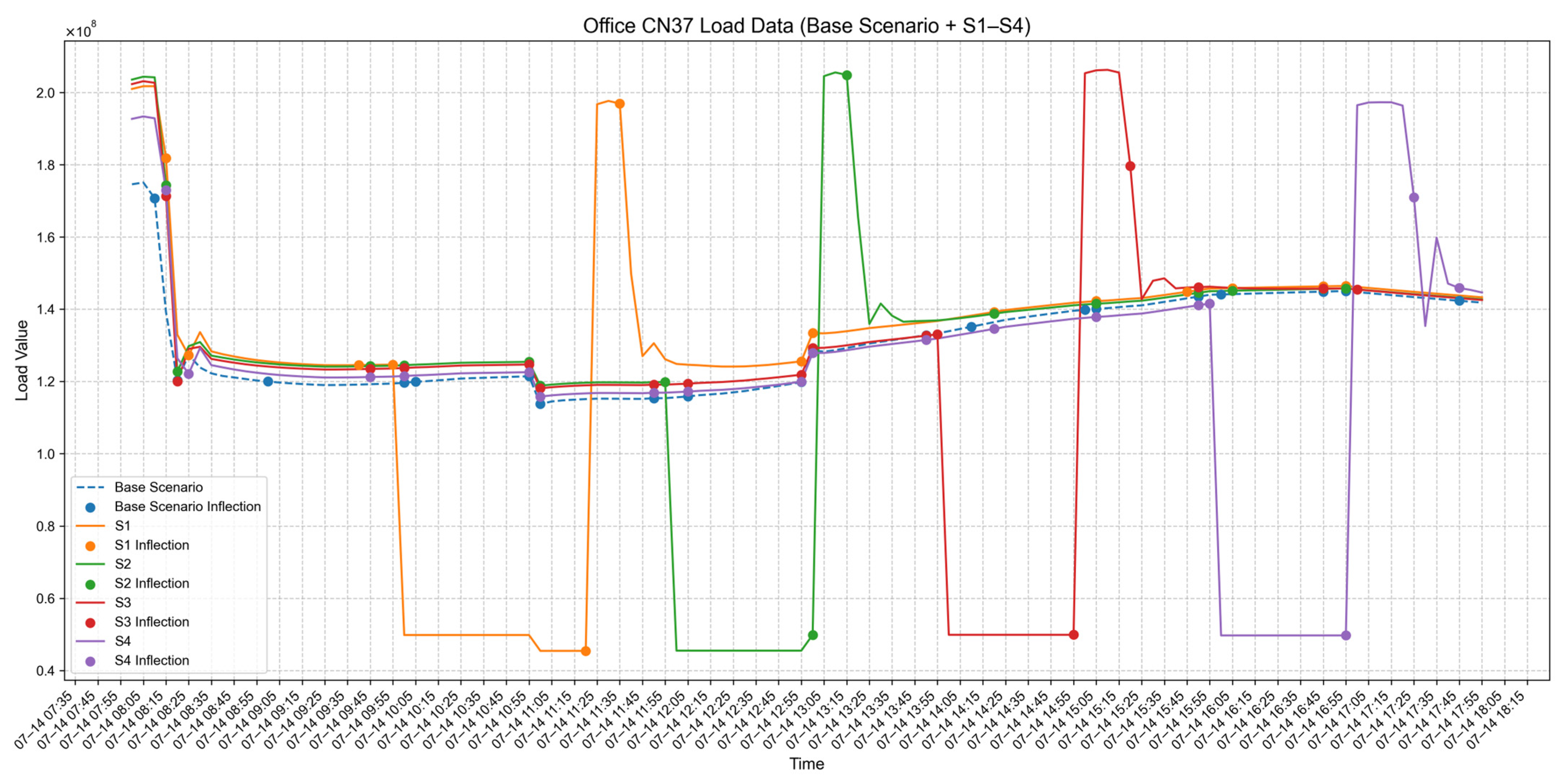

Building-type-dependent flexibility characteristics are systematically revealed through real-world case studies. Comparative analyses of office buildings, shopping malls, and hotels demonstrate distinct BAM–RD patterns across demand-response scenarios. The results provide actionable insights for selecting optimal response strategies for different building functions, supporting refined demand-response planning and the aggregation of heterogeneous building resources in virtual power plants.