Abstract

This study focuses on the operational energy consumption of existing thermal power plant buildings in China’s hot-summer, cold-winter regions. Unlike conventional civil buildings, thermal power plant structures feature intense internal heat sources, large spatial dimensions, specialized ventilation requirements, and year-round industrial waste heat. Consequently, the energy consumption characteristics and energy-saving logic of their building envelopes remain understudied. This paper innovatively employs a combined experimental approach of field monitoring and energy consumption simulation to quantify the actual thermal performance of building envelopes (particularly exterior walls, doors, and windows) under current operating conditions, identifying key components for energy-saving retrofits of the main plant building envelope. Due to the fact that most thermal power plants were designed relatively early, their envelope structures generally have problems such as poor insulation performance and insufficient air tightness, resulting in severe energy loss under extreme weather conditions. An energy consumption simulation model was established using GBSEARE software. By focusing on heat transfer coefficients of exterior walls and windows as key parameters, a design scheme for energy-saving retrofits of building envelopes in thermal power plants located in hot-summer, cold-winter regions was proposed. The results show that there is a temperature gradient along the height direction inside the main plant, and the personnel activity area in the middle activity level of the steam engine room is the most unfavorable area of the thermal environment of the steam engine room. The heat transfer coefficient of the envelope structure does not meet the current code requirements. The over-standard rate of the exterior walls is 414.55%, and that of the exterior windows is 177.06%. An energy-saving renovation plan is proposed by adopting a composite color compression panel for the external wall, selecting 50 mm flame-retardant polystyrene EPS foam board for the heat preservation layer, adopting 6 high-transmittance Low-E + 12 air + 6 plastic double-cavity for the external windows, and adding movable shutter sunshade. The energy-saving rate of the building reached 55.32% after the renovation. This study provides guidance for energy-efficient retrofitting of existing thermal power plants and for establishing energy-efficient design standards and specifications for future new power plant construction.

1. Introduction

Currently, the global energy transition and China’s “dual carbon” strategy (carbon peak and carbon neutrality) impose profound energy-saving and carbon-reduction requirements on the industrial sector, particularly the thermal power industry, a traditional major consumer of energy and emitter of pollutants [1]. Thermal power plants, as a vital segment of the industrial sector, encompass numerous production and auxiliary buildings. Controlling the total energy consumption of these structures is a key economic indicator influencing the future development of thermal power plants, making energy-saving retrofits of existing thermal power plant buildings of significant importance [2,3].

Energy-efficient design and retrofitting of existing buildings optimize resource utilization, significantly reduce environmental pollution, and enhance occupant health while lowering energy consumption [4,5,6]. Implementing green energy retrofits in existing structures-achieving 50% energy savings, 40% water savings, and 35% carbon reduction-has become a core solution to addressing environmental crises [7,8,9].

The hot summer and cold winter areas mainly refer to the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River and its surrounding areas [10], which are the regions with the poorest climatic conditions at the same latitude in the world [11]. Existing buildings in hot summer and cold winter areas generally have the following problems: in summer, due to high temperature and strong sunshine, the building envelope easily absorbs a large amount of heat, resulting in high indoor temperatures, air-conditioning energy consumption increased significantly; in winter, due to the cold and humidity, the building thermal insulation is insufficient, the indoor heat dissipation is faster, and the energy consumption of heating remains high [12]. In addition, many existing buildings are designed without adequate consideration of climate adaptation, and the thermal performance of the envelope is poor, further exacerbating the problem of energy waste [12]. In areas with a low climate of hot summers and cold winters, there are no district heating or centralized heating systems. Under natural ventilation conditions in winter, the indoor air temperature can be as low as 6 °C. Air conditioning units are widely used for heating (accounting for about 60%), which has also led to huge energy consumption in this region [13]. In hot summer and cold winter areas, improving the thermal insulation performance of the envelope is a necessary means to reduce building energy consumption, but the thickness of the insulation layer should not be blindly increased [14]. It has been found that improving the efficiency of heat pump air conditioning is a more effective energy-saving program when the thickness of the insulation layer reaches a certain threshold [14]. Therefore, the energy-saving retrofit of existing buildings in hot summer and cold winter areas is a key link to promote the green and low-carbon development of the construction industry.

Thermal power plants, as an important branch of the industrial sector, have a large number of production and ancillary buildings, and the control of total building energy consumption is an important part of the economic indicators that will affect the future of thermal power plants. Most existing thermal power plant buildings were constructed between the late 20th century and early 21st century. Their envelope designs often only met basic safety and functional requirements, with thermal performance significantly below current residential building energy efficiency standards. However, directly applying residential building energy efficiency theories to retrofit thermal power plants has clear limitations. The unique internal thermal environment of thermal power plants fundamentally alters the energy consumption mechanisms of their building envelopes compared to civil structures. Currently, academic research on industrial building energy efficiency remains relatively underdeveloped. Specifically, there is a lack of detailed analysis on the dynamic thermal performance of thermal power plant building envelopes, and no systematic energy retrofit strategies have been developed that account for the coupling relationship between their industrial characteristics and building energy consumption [15].

Current research indicates that thermal power plants have achieved significant energy savings through fly ash reuse, reduced fuel combustion, and condenser cleaning [16]; the implementation of flue gas waste heat recovery units enables staged utilization of residual heat [17]; post-combustion CO2 injection [18] and optimized scheduling of lighting and air conditioning systems [19] also yield notable energy efficiency gains. Research and policy focus for thermal power plants primarily centers on technical aspects like improving generator efficiency, clean fuel substitution, and carbon capture, while insufficient attention is given to the operational energy consumption of the plant buildings themselves. In reality, thermal power plants contain numerous auxiliary structures such as central control buildings, office buildings, and maintenance workshops. These structures are large in scale and face severe heating and cooling load challenges in regions with hot summers and cold winters. Thermal power plants can also adopt passive energy-saving technologies, such as natural ventilation design for plant buildings [20]; altering building orientation and window-to-wall ratios [21]; and enhancing the thermal performance of building envelopes to reduce energy consumption [22]. As the boundary between indoor and outdoor environments, building envelopes play a critical role in regulating heat flow, directly influencing energy consumption [23]. 60% to 80% of a building’s heating and cooling loads originate from heat exchange within the envelope [24,25]. Energy-saving retrofit design for building envelopes requires modeling and energy simulation, yet static simulation methods often fail to represent dynamic user behavior and actual energy consumption [26]. Energy-saving retrofits for thermal power plant buildings still face significant challenges, as their thermal performance generally falls short of current building energy efficiency standards, and theoretical research on related thermal environment retrofits remains relatively scarce.

This study addresses the issues of high building energy consumption and energy performance failing to meet current efficiency standards in existing thermal power plants located in regions with hot summers and cold winters. Employing a multi-point temperature monitoring method, it systematically analyzed the vertical temperature stratification characteristics within the main plant building. Utilizing heat flux meters to measure the dynamic thermal performance of the building envelope, it identified key thermal weak points. Building upon this, a refined building energy consumption model was established using GBSWARE 2024 software to simulate energy consumption characteristics under operational conditions. Integrating experimental and simulation findings, targeted retrofitting strategies for building envelopes were proposed, balancing winter insulation and summer heat dissipation. This research contributes to establishing a theoretical framework for industrial building energy conservation and provides scientific rationale for power plant retrofits supporting national carbon reduction objectives. The final paragraph of the introduction has been partially revised to read: This study not only provides an economically viable pathway for energy-efficient retrofits of existing thermal power plants, but its core analytical framework and design strategies also offer forward-looking guidance for the energy-efficient design and standardization of future new power plants.

2. Thermal Power Plant Building Site Measurements

2.1. Introduction to the Actual Test

The research object is a thermal power plant in China, Hubei Province (Figure 1), a hot summer and cold winter region, the main plant building area: 33360.21 m2, building footprint: 10519.3 m2, building volume 32711.1 m3, building height: 48.8 m. The structure is a frame structure. This area is located in the mid-latitudes inland and has a humid continental monsoon climate of the northern subtropical zone. It has abundant light energy, rich heat, plentiful rainfall, a long frost-free period, distinct four seasons, cold winters and hot summers, and thunder and heat occur simultaneously. However, due to the difference of 44 ‘in latitude between the north and south and 48’ in longitude between the east and west, especially the complex and diverse landform types and the obstruction of the Dabie Mountains, there are obvious differences in local climate elements, thus forming a multi-level three-dimensional climate with the characteristics of the transition from subtropical to temperate. Statistical analysis of the 2017–2024 data series from this urban meteorological station reveals: the extreme maximum temperature was 40 °C (August 2022), the extreme minimum temperature was −7 °C (January 2021), the annual average daytime temperature was 23 °C, and the average nighttime temperature was 13 °C. The heating period is calculated as 46 days.

Figure 1.

(a) Location of thermal power plant (b) Real scene picture of the thermal power plant.

The main building over 13.7 m in height adopts blue single-layer profiled steel sheet exterior walls, with purlins provided and fluorocarbon paint applied. No insulation measures have been taken. For areas under 13.7 m, 250 mm thick reinforced concrete blocks are used for enclosure, and elastic acrylic exterior wall coatings are applied. The exterior windows are made of 80 series aluminum alloy sliding windows with double-layer insulating glass. The roof adopts the inverted laying method, with cast-in-place reinforced concrete using profiled steel sheets as the bottom formwork as the roof panel, and perlite board insulation and SBS modified asphalt waterproofing membrane layer are laid on top. The theoretical thermal parameters of the building envelope are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Theoretical values of thermal parameters of the envelope structure.

2.2. Content of the Measurement

Two 16-day tests were conducted on the target building from 6 September to 21 September 2023 and from 6 January to 21 January 2024. The heat transfer coefficient of the building envelope and the indoor thermal environment were tested in accordance with Chinese standard JGJ/T357-2015 [27].

2.3. Methods of Measurement

2.3.1. Experimental Measurement Equipment

The parameters of the experimental equipment are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Measured equipment parameter table.

2.3.2. Indoor Thermal Environment Testing

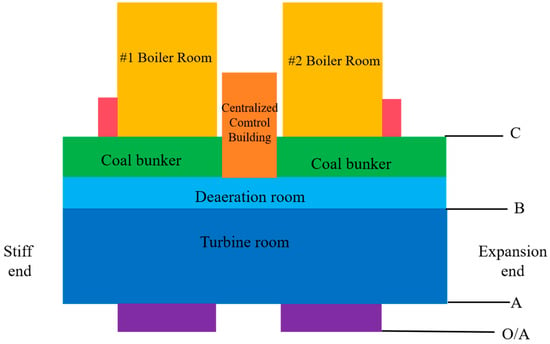

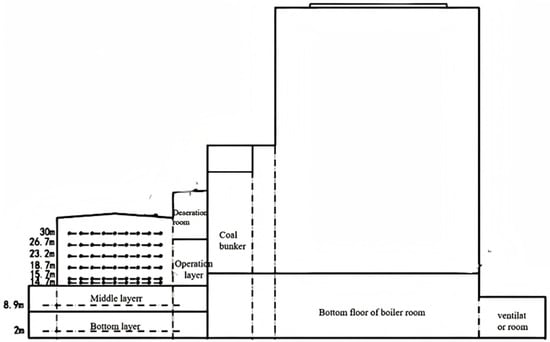

The indoor temperature testing method is consistent throughout the year. Through a large number of temperature measurement points, the indoor temperature distribution at different heights of the main building of the thermal power plant is statistically summarized. The turbine room building is divided into the ground floor, the middle floor and the operation floor. The equipment layout on each floor is different, and different testing methods and measurement point layout schemes are adopted for tests on different floors. The layout of the main plant is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The layout of the main plant. Commentary: OA, A, B, C denotes the coordinate axis. Yellow denotes the boiler room. Green denotes the coal bunker room. Sky blue denotes the deaeration room. Navy blue denotes the turbine room. Orange denotes the centralized control building.

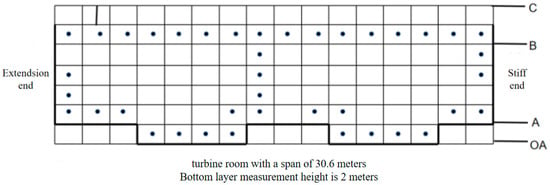

(1) In the ground floor and middle floor areas of the turbine room, due to the complex arrangement of internal equipment in the height direction, only the height hanging temperature self-recording instrument in the personnel activity area was used for measurement. The layout of measurement points on each floor is shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4. The areas without measurement points are the areas that cannot be reached due to the obstruction of the equipment.

Figure 3.

Layout plan of measurement points on the ground floor of the turbine room. Commentary: OA, A, B, C denotes the coordinate axis. Different blue spots denote measurement points at different locations.

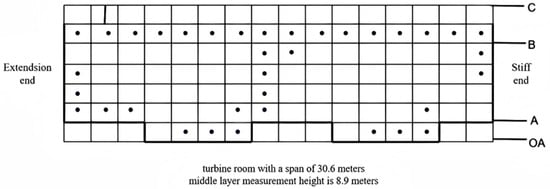

Figure 4.

Layout of measurement points in the middle floor of the turbine room. Commentary: OA, A, B, C denotes the coordinate axis. Different black spots denote measurement points at different locations.

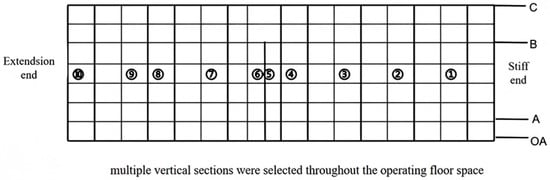

(2) The vertical height of the turbine room’s operating floor is approximately 21 m. Along its height direction, there are almost no pipes or equipment arranged. Therefore, the method of hanging temperature self-recording instruments at different heights and on different planes was adopted for testing, and multiple vertical sections were selected throughout the operating floor space (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the vertical plane position for spatial field measurement in the turbine room operation layer. Commentary: OA, A, B, C denotes the coordinate axis. Numbers 1 to 10 denote measurement points at different locations.

(3) Conduct temperature tests at different heights of each cross-section by suspending temperature automatic calculation. The temperature measurement points at the bottom are arranged at a height of approximately 2 m. The temperature measurement points in the middle layer are arranged at a height of approximately 8.9 m. The measurement points of the operation layer are arranged at six different heights, with the highest measurement point located at a height of approximately 30 m. The test instruments adopt the Jing chuang brand TLOG100E temperature self-recording instrument and RC-4 automatic temperature recorder. The instrument should be placed in a location away from direct sunlight, indoor heat sources and the influence of rain and snow. Data collection should be conducted every 20 min (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of sensor placement at different measurement heights and operational levels in the steam turbine room.

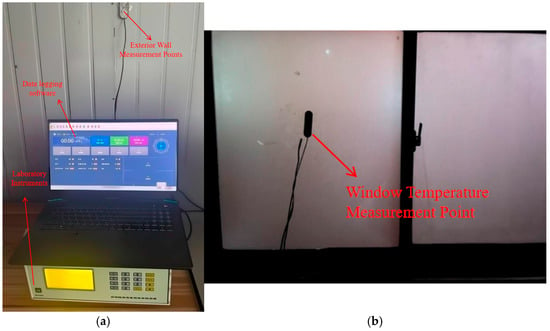

2.3.3. Enclosure Heat Transfer Coefficient Testing

Enclosure heat transfer coefficient test according to the Chinese standard JGJ/T357-2015 [27] in the provisions of the heat flow meter method, respectively, the external wall, external window test, the test instrument is used QTS-8 temperature heat flow recorder, the experimental test point arrangement to avoid close to the building thermal bridges, cracks and air leakage parts, the test point probe should be avoided to rain and snow and direct sunlight. Therefore, the measuring point of the external wall is selected from the northward external wall of the building, and the measuring point of the external window is selected from the external window of the equipment room on the second floor, and the data collection is carried out once every 10 min to record the internal and external heat flux density and the internal and external surface temperatures, respectively. The layout of the measurement points is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Energy Saving Retrofit Achievement Showcase: (a) Exterior wall measurement point (b) Exterior window measurement point.

2.4. Analysis of Measured Results

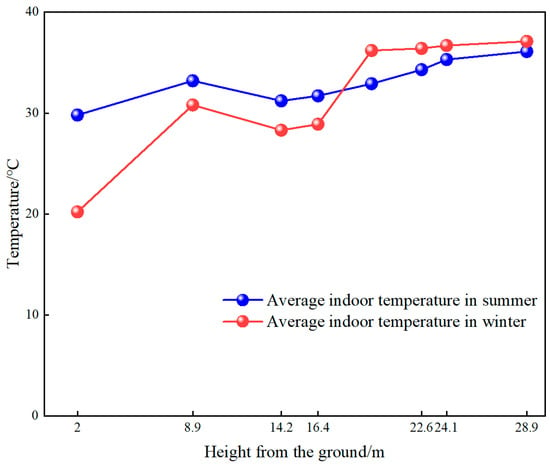

2.4.1. Thermal Environment Analysis

The summer testing commenced on 17 September 2023, conducted in cycles of seven days, with two such cycles completed. During this period, the steam turbine generator units operated at full load. During the test, all the roof fans of the steam engine room were open, all the sliding windows on the operation floor of the steam engine room were open, the air intake louvers on the bottom and middle floors were partially open, and all the sliding windows were open. The door at the bottom of the steam engine room was closed, leaving only one small door for people to pass through, and all other doors were open. The winter testing commenced on 9 January 2024, conducted in two consecutive cycles, each lasting seven days. During this period, the steam turbine generator sets operated at full load. During the test, the roof fan of the turbine room was turned off, the windows on the operation level were generally closed, the windows and shutters on the middle and bottom levels were naturally closed, and the doors on the bottom level of the turbine room were closed (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Comparison of trends in the distribution of mean indoor temperatures at different heights.

During summer, the indoor temperature within the main plant building exhibits distinct vertical stratification. Two primary factors contribute to this phenomenon: firstly, the continuous release of substantial heat generated by operational equipment; secondly, the accumulation of heat within the upper sections of the building driven by thermal pressure.

Comparative analysis of average temperatures across personnel activity zones on different levels of the turbine hall reveals that the middle level maintains the highest temperature. This occurs because the middle level is directly affected by heat dissipation from equipment installed there, while also experiencing upward heat transfer from equipment situated at ground level.

During winter, the pronounced indoor-outdoor temperature differential intensifies the thermal pressure effect, resulting in a significant vertical temperature gradient between the upper and lower sections of the building. Consistent with summer findings, the middle level of the turbine hall continues to exhibit the highest average temperature. Concurrently, the vertical temperature gradient within the building is greater in winter than in summer. The fundamental cause lies in the closure of doors and windows to prevent cold air infiltration; however, the substantial heat emitted by indoor equipment cannot be effectively dissipated through the building envelope, leading to severe heat accumulation in the upper regions of the main plant building.

Measurement results show that a large amount of waste heat is generated during the operation of the equipment in the steam engine room of the main plant. A large amount of waste heat is directly discharged into the atmosphere, which not only causes waste of heat energy and pollution of the outdoor environment, but also leads to a large temperature gradient indoors, which affects the comfort of the staff. Reasonable recovery and utilization of process waste heat in thermal power plants can effectively reduce their building energy consumption and improve energy utilization.

2.4.2. Enclosure Heat Transfer Coefficient Analysis

The measured results of external walls and windows are shown in Table 3. The heat transfer coefficients of the measured parts of the enclosure structure do not meet the requirements of the current energy-saving standards, the heat transfer coefficient of the exterior wall of aerated concrete block exceeds the standard by 146.36%, the heat transfer coefficient of the exterior wall of pressed steel plate exceeds the standard by 654.54%, the average excess rate of the exterior wall is 414.55%, and the heat transfer coefficient of the exterior window exceeds the standard by 177.06%. There is a significant difference between the measured value and the theoretical value of the heat transfer coefficient of the envelope structure. The main causes can be summarized as follows: thermal bridge effect caused by structural design defects, performance aging and deterioration of materials during long-term use, deviations in construction techniques and insufficient quality control, as well as inevitable equipment and measurement errors in on-site testing.

Table 3.

Test results of heat transfer coefficients for exterior walls and exterior windows.

The exterior walls of the target building below the 13.7 m floor are made of 250 mm thick aerated concrete blocks, and the measured heat transfer coefficient is 1.61 W/(m2·K). It does not meet the requirements of the Chinese standards GB 55015-2021 [28] and GB51245-2017 [29] that the heat transfer coefficient of the exterior wall shall not exceed 1.1 W/(m2·K), but its design value is 0.824 W/(m2·K), which meets the specification requirements. Therefore, only renovation and repair are carried out, without energy-saving transformation. The exterior walls of single-layer profiled steel sheets above the 13.7 m floor are not equipped with insulation layers. The designed heat transfer coefficient is as high as 6.66 W/(m2·K), making it a key part of the energy-saving renovation of the building’s envelope structure. The theoretical heat transfer coefficient of the building’s exterior windows is 3.24 W/(m2·K), and the south-facing window-to-wall ratio is 0.22, which meets the requirements of the Chinese standards GB55015-2021 [28] and GB51245-2017 [29]. However, its measured value was 6.02 W/(m2·K), far exceeding the limit of the heat transfer coefficient. The reason is that the exterior windows have been in use for too long, with severe aging problems and a significant decline in sealing performance. Industrial buildings, especially those of thermal power plants, must ensure that the heat transfer coefficients of materials meet the requirements of the specifications while also guaranteeing the stability and corrosion resistance of the materials.

3. Simulation Analysis of Energy Efficiency Retrofits in Thermal Power Plants

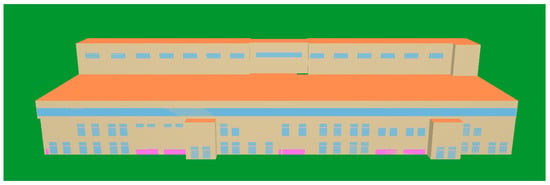

3.1. Establish Energy Consumption Models and Model Verification

The GBSWARE software was selected to establish a typical building model. Energy-saving design and energy consumption calculation functions were used to simulate the energy consumption of the typical building. Outdoor meteorological conditions were based on the typical meteorological annual data of the city. The geographical location of Wuhan City, Hubei Province, is 114.13° east longitude, 30.62° north latitude, and 23 m above sea level. The simulation of heat sources in the main rooms of the power plant’s main building was selected based on the actual conditions of the building. The design humidity for both summer and winter was set to 60%, with a fresh air supply rate of 30 m3/h per person. Simulation parameters of thermal power plant energy consumption include lighting power density, equipment power density, personnel density and heat dissipation, fresh air volume, summer and winter set temperatures of the room, lighting on/off time, equipment utilization rate, personnel occupancy rate, fresh air operation status, heating and air conditioning system operation time, and hourly room temperature were referenced from the Chinese standards GB51245-2017 [29] and GB50660-2011 [30]. Among them, this building adopts a centralized air conditioning system for both cooling and heating. Meanwhile, in accordance with the provisions of this standard, the building is located in a hot summer and cold winter area. The comprehensive efficiency conversion weight of its cooling system is set at 2.5, and that of the heating system is set at 2. The cold source machine room is equipped with two water-cooled screw chiller units and one water source heat pump unit, while the heat source machine room is fitted with one air source heat pump and a heating water pump. The thermal conductivity coefficients of the building envelope are selected based on measured values (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

This study’s thermal power plant model.

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the simulation data, the thermal conductivity coefficients of the existing building envelope were incorporated into the model prior to conducting the energy consumption simulation. A dynamic energy consumption simulation was then performed on the building. The results were compared with the theoretically calculated building energy consumption values to validate the model, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of theoretical calculation values and energy consumption simulation values.

The simulated building energy consumption results, based on the measured thermal conductivity coefficients, were 26.45 kwh/m2, which differed by 5.71% from the theoretical calculation value of 24.94 kwh/m2. This discrepancy may be attributed to the simplification of the model, which may have overlooked certain complex variables or failed to fully account for various uncertainties in real-world environments. Considering the limitations of both simulation and testing, the overall deviation of the model remains within a reasonable range.

3.2. External Wall Energy Efficiency Renovation and Energy Consumption Analysis

3.2.1. Exterior Wall Energy Efficiency Renovation Plan

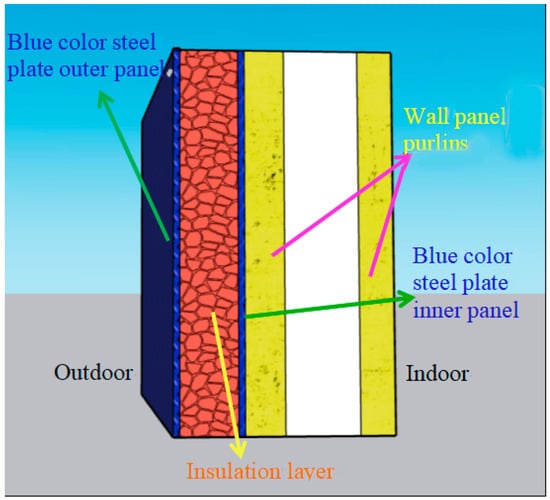

Optimize single-layer colored corrugated steel sheet exterior walls to factory-made composite corrugated steel sheet exterior walls, i.e., insulation composite enclosure panels formed by bonding (or foaming) colored coated steel sheets and base plates with insulation core materials (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Factory composite color pressure plate construction.

The selection of insulation materials should be based on factors such as ambient temperature, thermal conductivity of the material, and minimum thermal resistance value. Currently, there are numerous insulation materials available on the market. This study selected the most commonly used insulation materials: EPS, XPS, rock wool boards, and PU boards. Their characteristics and insulation performance are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Various material parameters of exterior wall insulation layer.

XPS boards are more expensive than EPS boards; PU boards have the best thermal insulation performance but poor fire resistance and the highest cost; rock wool boards are low-cost but highly hygroscopic and have low strength, making them unsuitable for regions with complex and variable climates, such as those with hot summers and cold winters. Therefore, the insulation layer material for composite-colored corrugated panels is selected as flame-retardant polystyrene foam (EPS) boards. This material has excellent thermal insulation and cushioning properties. Although EPS boards are inherently flammable, their fire resistance can be significantly improved by adding flame retardants. EPS boards are lightweight, cost-effective, easy to cut and install, and convenient for construction.

3.2.2. External Wall Energy Consumption Simulation Analysis

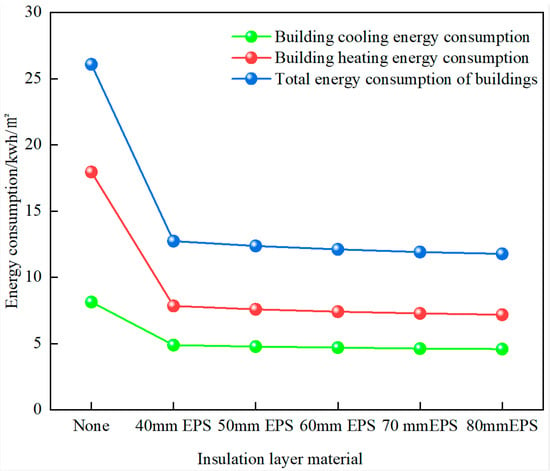

During the simulation, the thermal conductivity coefficients of the aerated concrete exterior walls below the 13.7 m layer and the 80-series aluminum alloy sliding windows were selected based on design values, specifically 0.824 W/(m2·K) and 3.24 W/(m2·K), respectively. Energy-saving renovations were conducted on the building’s exterior walls using fire-resistant expanded polystyrene (EPS) boards of varying thicknesses (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Impact of different insulation layer thicknesses on energy consumption.

As shown by the data, when the thickness of the insulation layer material changes from 0 mm to EPS 50 mm, the total energy consumption of the building decreases by 13.72 kwh/m2, with an energy savings rate of 52.59%. The most significant reductions are observed in cooling and heating energy consumption. As the thickness of the insulation layer increases, the thermal conductivity coefficient of the exterior walls continues to decrease, leading to a reduction in cooling and heating energy consumption. However, the rate of decrease gradually slows down. When the insulation layer thickness is 50 mm and the thermal conductivity coefficient is 0.87 W/(m2·K), the energy-saving trend of the project is evident. At this point, the comprehensive thermal conductivity coefficient of the exterior wall is 0.88 W/(m2·K), meeting the requirement of 1.1 W/(m2·K) specified in the General Specifications for Chinese standard GB55015-2021 [28]. Considering factors such as material costs, thermal conductivity coefficients, and their impact on building energy consumption, this study adopts 50 mm fire-retardant expanded polystyrene foam boards (EPS boards) as the insulation layer material for factory-produced color-coated steel panels in the exterior wall energy-saving renovation scheme.

3.3. Exterior Window Energy Saving Reconstruction and Simulation Analysis

3.3.1. The Influence of the Heat Transfer Coefficient of Exterior Windows

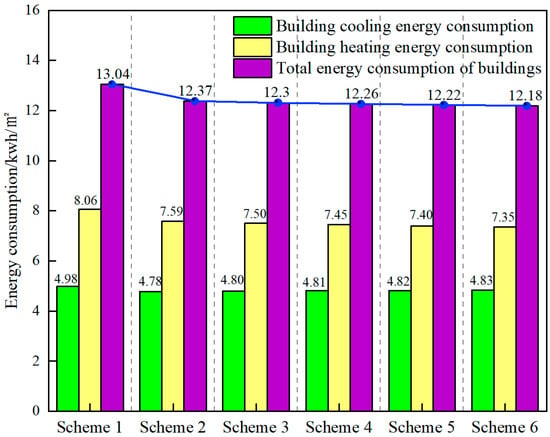

Currently, the market offers a variety of new window frame profiles and high-performance glass materials. Selecting materials with superior thermal performance is essential for renovating the exterior windows of this building. Using the thermal conductivity coefficient of the exterior windows as the sole variable, the thermal conductivity coefficient of the exterior walls is taken as 50 mm EPS insulation, and the solar heat gain coefficient of the exterior windows is set to the default value of 0.766. The control variable method is employed to simulate the project. There are six schemes for the thermal conductivity coefficient energy consumption simulation of the exterior windows. Scheme 1 has a thermal conductivity coefficient of 6.02 W/(m2·K), Scheme 2 has an exterior window thermal conductivity coefficient of 3.24 W/(m2·K), Scheme 3 has a coefficient of 2.7 W/(m2·K), Scheme 4 has a coefficient of 2.4 W/(m2·K), Scheme 5 has a coefficient of 2.1 W/(m2·K), and Scheme 6 has a coefficient of 1.8 W/(m2·K). The energy consumption simulation is shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Influence of heat transfer coefficient of external windows.

As the thermal transmittance coefficient of exterior windows continues to decrease, the total energy consumption of buildings shows a decreasing trend, with heating energy consumption decreasing and cooling energy consumption showing a slight upward trend. When the thermal transmittance coefficient of exterior windows is 2.7 W/(m2·K), a decrease of 0.3 W/(m2·K) in the thermal transmittance coefficient results in a 0.02% increase in cooling energy consumption and a 6.67% decrease in heating energy consumption. The increase in cooling energy consumption is due to the fact that buildings transfer heat to the outdoors at night. However, as the thermal transmittance coefficient of exterior windows decreases, indoor heat becomes increasingly difficult to dissipate, thereby increasing the next day’s cooling energy consumption.

3.3.2. The Influence of the Solar Heat Gain Coefficient of Exterior Windows

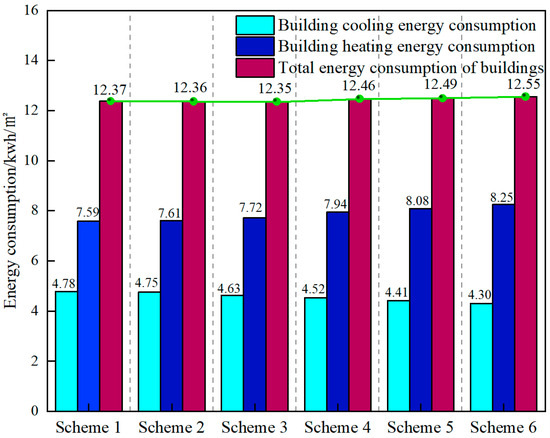

Using the solar heat gain coefficient of exterior windows as the sole variable, the thermal conductivity coefficient of exterior walls is taken as 50 mm EPS insulation, and the thermal conductivity coefficient of exterior windows is taken as the default value of 3.24 W/(m2·K). The building is simulated using the control variable method. There are six simulation schemes for the solar heat gain coefficient of exterior windows. Scheme 1 has a solar heat gain coefficient of 0.766, Scheme 2 has a solar heat gain coefficient of 0.7, Scheme 3 has a solar heat gain coefficient of 0.6, Scheme 4 has a solar heat gain coefficient of 0.5, Scheme 5 has a solar heat gain coefficient of 0.4, and Scheme 6 has a solar heat gain coefficient of 0.3. The energy consumption simulation is shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Influence of the solar heat gain coefficient of exterior windows.

The most typical climatic feature of a hot summer and cold winter region is that it is extremely hot in summer and cold in winter. This kind of climatic condition leads to a significant “contradiction” or “trade-off” characteristic in the impact of the solar heat gain coefficient on building energy consumption. In summer, excessively high SHGC can cause a large amount of solar radiation to enter the room. After the solar radiation energy is converted into heat, it leads to a significant increase in indoor temperature. To maintain indoor thermal comfort, air conditioning systems have to operate for longer periods and at higher loads, which leads to a significant increase in cooling energy consumption. In winter, a lower SHGC not only effectively blocks the overheating of summer but also suppresses the entry of solar radiation heat required in winter, thereby increasing the building’s reliance on active heating systems and pushing up heating energy consumption.

It can be seen from the diagram relationship that as the solar heat gain coefficient decreases, the energy consumption for building cooling shows a continuous downward trend, while the energy consumption for heating increases accordingly. The underlying mechanism lies in the fact that a lower SHGC can block more solar radiation heat from entering the room in summer, thereby effectively reducing the demand for cooling. However, in winter, the heat gained from solar radiation obtained by the exterior windows decreases accordingly, resulting in an increase in the heating load. Therefore, in regions with hot summers and cold winters, it is not scientific to simply pursue extremely high or extremely low SHGC values. A reasonable strategy should be to take a lower SHGC as the basic basis for the selection of exterior windows, giving priority to meeting the heat insulation demands in summer. At the same time, low SHGC windows with a lower heat transfer coefficient (K value) should be chosen to improve the insulation performance in winter in a coordinated manner and achieve a comprehensive optimization of energy consumption throughout the year.

3.3.3. Energy-Saving Renovation Plan for Exterior Windows

Window frame materials have a significant impact on heat loss through windows. Different window frame materials exhibit substantial differences in thermal resistance, which in turn significantly affects the thermal transmittance coefficient of windows. Window frame materials primarily consist of solid wood, PVC, and aluminum alloy, each with its own advantages. Table 6 lists the thermal conductivity coefficients of different window frames using the same type of glass. As shown in the table, among windows of the same design, aluminum alloy windows have the highest thermal conductivity coefficient, while plastic windows have the lowest. After thermal break treatment, the thermal performance of aluminum alloy windows is significantly improved; however, aluminum alloy windows with thermal break treatment have higher costs.

Table 6.

Heat transfer coefficients of common window frames.

PVC plastic windows are a rapidly developing new type of energy-efficient window and door system. The primary material used is polyvinyl chloride (PVC), which offers excellent thermal insulation, poor thermal conductivity, and superior sealing performance. As a result, PVC window frames have become increasingly popular in recent years. Low-E glass with a low solar heat gain coefficient is suitable for regions with hot summers and cold winters. It effectively reduces solar radiation entering the indoor space during summer, thereby saving air conditioning energy consumption. Therefore, a double-pane window with 6 mm high-transmittance Low-E glass + 12 mm air space + 6 mm plastic is selected. The specific parameters are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Exterior window retrofit option.

3.3.4. Energy Consumption Simulation Analysis

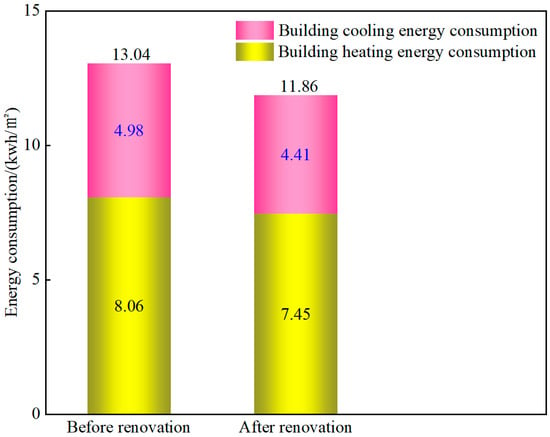

Energy consumption analysis was conducted using the GBSWARE 2024 software for the two types of exterior window constructions before and after renovation. After the energy-saving renovation, the thermal conductivity coefficient decreased, as did the solar heat gain coefficient and transmittance ratio. The building’s cooling energy consumption decreased by 0.57 kwh/m2, heating energy consumption decreased by 0.61 kwh/m2, and the total energy consumption of the building decreased by 1.18 kwh/m2, with an energy savings rate of 9.15%. The energy consumption simulation is shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Comparison of energy consumption before and after energy-saving renovation.

3.4. Sunshade Energy-Saving Renovation and Simulation Analysis

During the summer, buildings are exposed to intense solar radiation, and the large amount of heat entering the interior through radiation can lead to high cooling energy consumption. Installing external shading components can effectively reduce solar radiation and achieve good thermal insulation, but this can also reduce solar heat gain in the interior during the winter, thereby increasing heating energy consumption. In regions with significant seasonal temperature fluctuations, such as those with hot summers and cold winters, adjustable louvered shading systems can be adjusted in response to changes in solar radiation. During summer, the louvers are opened to reduce solar radiation heat indoors, thereby lowering cooling energy consumption. During winter, the louvers are closed to allow sufficient solar radiation indoors, reducing heating energy consumption.

In the GBSWARE software, external window louvered shading is implemented with the following parameters: louver tilt angle adjustment set to 60 degrees, downward angle adjustment set to 20 degrees, horizontal diffusion angle adjustment set to 30 degrees, and louver panel transmittance ratio set to 0.15. According to software calculations, the summer external shading coefficient is 0.507, and the comprehensive shading coefficient after renovation is 0.266. The building’s cooling energy consumption after adding shading is 4.21 kwh/m2, a reduction of 0.2 kwh/m2 compared to without shading.

3.5. Total Renovation Scheme and Energy Consumption Analysis

Set the model enclosure structure according to Table 8. Keep the other indoor parameters and HVAC parameters the same as in the original building simulation.

Table 8.

Enclosure energy efficiency retrofit schemes.

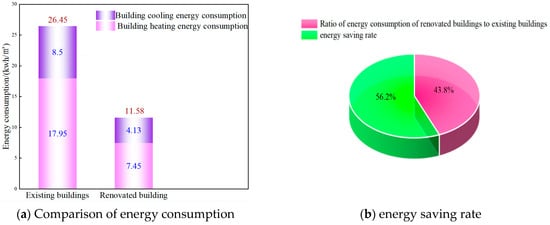

Energy consumption simulations of the building were conducted using the GBSWARE software. A comparative analysis of energy consumption data before and after the renovation reveals that the energy-saving renovation measures have significantly reduced the building’s energy consumption. Specifically, the heating energy consumption of the renovated building decreased by 10.50 kwh/m2 compared to the existing building, the cooling energy consumption decreased by 4.37 kwh/m2, and the total energy consumption of the building decreased by 14.87 kwh/m2 overall, with an energy savings rate as high as 56.2%, meeting the requirements of Chinese standards GB51245-2017 [29] and GB/T51141-2015 [31]. This result indicates that the energy-saving renovation measures have achieved significant in improving the thermal performance of the building and reducing energy consumption (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Energy Saving Retrofit Achievement Showcase: (a) Comparison of energy consumption (b) energy saving rate.

The significant reduction in heating energy consumption is primarily attributed to improvements in the thermal insulation performance of building envelopes, such as optimized exterior wall insulation materials, enhanced thermal insulation of exterior windows, and improved airtightness. These measures effectively reduce heat loss from indoor spaces during winter, thereby lowering heating requirements. The reduction in cooling energy consumption is closely related to the optimization of building exterior shading systems and the application of roof insulation materials. These measures effectively block the entry of solar radiation heat during summer, thereby reducing the load on air conditioning systems.

By the end of 2022, China’s total installed thermal power capacity exceeded 1.3 billion kilowatts, with existing power plants in hot summer and cold winter regions featuring auxiliary buildings covering tens of millions of square meters. If the retrofitting strategy proposed in this paper is widely adopted, with an estimated 50% energy savings rate, it is projected to conserve millions of tons of standard coal annually. This would correspondingly reduce carbon dioxide emissions by over 10 million tons—equivalent to the total annual building carbon emissions of a medium-sized city—making a significant contribution to China’s goal of achieving carbon peak by 2030. Scaling up this energy-saving retrofit solution would not only lower power plant operating costs and enhance competitiveness but also help optimize the national energy structure, demonstrating the synergistic benefits of green transition and economic development.

This study confirms that energy-saving retrofits of existing thermal power plant buildings, achieved through on-site energy consumption measurements and simulations, can significantly enhance building energy efficiency without requiring large-scale demolition and reconstruction. This provides an economically viable pathway for the green renewal of industrial buildings in China and globally. China’s industrial emissions reduction practices carry broad implications. This study indicates substantial potential for energy conservation and emissions reduction remains in traditional sectors like thermal power generation. Such research helps bolster international confidence in technological and management-driven emissions reductions, propelling the global energy system toward a more efficient and cleaner transformation.

4. Conclusions

(1) The on-site measurement results show that the main building of this thermal power plant has significant indoor temperature gradients in both summer and winter, among which the thermal environment in the personnel activity area of the middle floor of the turbine room is the most unfavorable. The test data further shows that the heat transfer coefficients of the building’s exterior walls and windows do not meet the current code limits, with the over-limit rates reaching 414.55% and 177.06%, respectively.

(2) Energy consumption simulation analysis shows that building energy consumption is closely related to the thickness of the exterior wall insulation layer. When the exterior wall insulation material was changed from no insulation (with a thickness of 0 mm) to 50 mm thick flame-retardant polystyrene foam board (EPS), the reduction in building energy consumption was the most significant. When the thickness of the insulation layer exceeds 50 mm, the reduction in building energy consumption tends to level off. Therefore, 50 mm thick flame-retardant expanded polystyrene (EPS) boards represent the optimum insulation thickness. The energy consumption per unit area decreasing by 13.72 kWh/m2, and the energy-saving rate reaching 52.59%.

(3) The simulation results also show that the energy consumption of buildings is jointly affected by the heat transfer coefficient (K value) of exterior windows and the solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC). The lower the heat transfer coefficient of the exterior windows, the lower the total energy consumption of the building shows a downward trend. As the heat gain coefficient of the sun decreases, the energy consumption for cooling continues to drop, while the energy consumption for heating rises accordingly. After the exterior window renovation, the energy consumption per unit area of the building decreased by 1.18 kWh/m2, with an energy-saving rate of 9.15%. In view of the climatic characteristics of hot summers and cold winters, it is recommended that the exterior windows of thermal power plant buildings be equipped with movable louver shading systems. The simulation shows that after adding this shading measure, the cooling energy consumption is 4.21 kWh/m2, which is 0.2 kWh/m2 lower than before it was set.

(4) Proposed building energy-saving renovation plan: Replace single-layer colored corrugated steel plates on exterior walls above the 13.7 m level with factory-made composite-colored corrugated panels (insulation material: 50 mm-thick flame-retardant EPS foam boards); replace 80-series aluminum alloy sliding windows with 5 + 9A + 5 double-pane insulated glass with 6 high-transmittance Low-E + 12 air + 6 plastic double-cavity windows; install movable louvered sunshades. After the renovation, the building’s heating energy consumption was reduced by 10.5 kwh/m2, cooling energy consumption was reduced by 4.37 kwh/m2, and total building energy consumption was reduced by 14.87 kwh/m2, achieving an energy savings rate of 56.2%, which meets the requirements of current energy efficiency standards.

Author Contributions

L.Q.: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing—review and editing. J.Q.: Methodology, Validation, Software, Writing—original draft. Y.Q.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing—review and editing. W.S.: Investigation, Funding acquisition, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51208082) and Key Projects of Scientific and Technological Research of Jilin Provincial Department of Education (Jilin Educational Science and Technology Co-ordination [2013] No. 113).

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, Z.; Deng, Z.; He, G.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Lin, J.; Qi, Y.; Liang, X. Challenges and opportunities for carbon neutrality in China. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 3, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, T.; Eicker, U. Energy performance of industrial buildings: A systematic review. Energ. Build. 2020, 223, 110189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Cooper, P.; Daly, D.; Ledo, L. Existing building retrofits: Methodology and state-of-the-art. Energ. Build. 2012, 55, 889–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50378-2019; Assessment Standard for Green Building. China Construction Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2025. Available online: https://www.ccsn.org.cn/Zbbz/Show.aspx?Guid=308451fc-1063-40a9-8568-accef8d1aa2f (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Liu, Y.; Li, T.; Xu, W.; Wang, Q.; Huang, H.; He, B.-J. Building information modelling-enabled multi-objective optimization for energy consumption parametric analysis in green buildings design using hybrid machine learning algorithms. Energ. Build. 2023, 300, 113665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Liu, X.; Feng, G.; Wang, C.; Huang, K.; Hou, X.; Chen, J. Research on the evaluation of the renovation effect of existing energy-inefficient residential buildings in a severe cold region of China. Energ. Build. 2024, 312, 114184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solla, M.; Elmesh, A.; Memon, Z.A.; Ismail, L.H.; Al Kazee, M.F.; Latif, Q.B.A.I.; Yusoff, N.I.M.; Alosta, M.; Milad, A. Analysis of BIM-Based Digitising of Green Building Index (GBI): Assessment Method. Buildings 2022, 12, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Li, X. Research on BIM Technology of Green Building Based on GBSWARE Software. Buildings 2025, 15, 2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ge, Z.; Yang, Y.; Hao, J.; Xu, L.; Du, X.; Træholt, C. Carbon reduction and flexibility enhancement of the CHP-based cascade heating system with integrated electric heat pump. Energ. Convers. Manag. 2023, 280, 116801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Cheng, B.; Gou, Z.; Zhang, F. Outdoor thermal comfort and adaptive behaviors in a university campus in China’s hot summer-cold winter climate region. Build. Environ. 2019, 165, 106414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Yao, R.; Han, S.; Du, C.; Yu, W.; Chen, S.; Li, B.; Yu, H.; Li, N.; Peng, J.; et al. How do urban residents use energy for winter heating at home? A large-scale survey in the hot summer and cold winter climate zone in the Yangtze River region. Energ. Build. 2020, 223, 110131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Han, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Lian, Y.; Chen, H. Potential of carbon emissions from heating in hot summer and cold winter urban residential areas in China through 2050. Energ. Build. 2025, 341, 115790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gong, G. Exergy analysis of the building heating and cooling system from the power plant to the building envelop with hourly variable reference state. Energ. Build. 2013, 56, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-J.; Moon, J.-H.; Choi, D.-S.; Ko, M.-J. Application of the Heat Flow Meter Method and Extended Average Method to Improve the Accuracy of In Situ U-Value Estimations of Highly Insulated Building Walls. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, N.; EL Mghouchi, Y.; Hamdaoui, S.; EL Asri, N.; Mouqallid, M. Multi-objective optimization of passive energy efficiency measures for net-zero energy building in Morocco. Build. Environ. 2021, 204, 108141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, N.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z.; Xu, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, K. A Comprehensive Energy Saving Potential Analysis of a 660 MW Coal-Fired Ultra-Supercritical Power Plant. J. Therm. Sci. 2025, 34, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Xin, H.; Liu, M.; Wang, L.; Yan, J. The pressure sliding operation strategy of the carbon capture system integrated within a coal-fired power plant: Influence factors and energy saving potentials. Energy 2024, 307, 132737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luo, Q.; Jiang, J.; Xiang, W.; Chen, S. Techno-economic assessment and optimization of PZ/MDEA-based CO2 capture for coal-fired power plant. Energy 2025, 327, 136395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.; Martín, M. Cooling limitations in power plants: Optimal multiperiod design of natural draft cooling towers. Energy 2017, 135, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Chikamoto, T.; Lee, M.; Tanaka, T. Impact of Building Orientation on Energy Performance of Residential Buildings in Various Cities Across Afghanistan. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.E.; Suwaed, M.S.; Shakir, A.M.; Ghareeb, A. The impact of window orientation, glazing, and window-to-wall ratio on the heating and cooling energy of an office building: The case of hot and semi-arid climate. J. Eng. Res. 2025, 13, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, S.; Lu, B. Experimental comparisons on optical and thermal performance between aerogel glazed skylight and double glazed skylight under real climate condition. Energ. Build. 2020, 222, 110028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruta, G.; Ascione, F.; Iovane, T.; Mastellone, M. Thermal resilience to climate change of energy retrofit technologies for building envelope. Energy 2025, 327, 136489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Xu, X.; Sun, Y. A study on pipe-embedded wall integrated with ground source-coupled heat exchanger for enhanced building energy efficiency in diverse climate regions. Energ. Build. 2016, 121, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Chen, L.; Suolang, B.; Liu, K. An Investigation of the Energy-Saving Optimization Design of the Enclosure Structure in High-Altitude Office Buildings. Buildings 2024, 14, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, A.C.; Cripps, A.; Bouchlaghem, D.; Buswell, R. Predicted vs. actual energy performance of non-domestic buildings: Using post-occupancy evaluation data to reduce the performance gap. Appl. Energ. 2012, 97, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JGJ/T357-2015; Technical Specification for In-Situ Measurement of Thermal Transmittance of Building Envelope. China Construction Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2015. Available online: https://www.ccsn.org.cn/newweb/standardQuery?guid=6ad2afaa-5651-44fa-b06c-afb0f691c897&showDetail=true (accessed on 1 October 2015).

- GB 55015-2021; General Code for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Application. China Construction Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2021. Available online: https://www.mohurd.gov.cn/gongkai/zc/wjk/art/2024/art_17339_762460.html (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- GB 51245-2017; Unified Standard for Energy Efficient Design of Industrial Buildings. China Construction Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2017. Available online: https://www.mohurd.gov.cn/gongkai/zc/wjk/art/2017/art_17339_233404.html (accessed on 1 January 2018).

- GB 50660-2011; Code for Design of Fossil Fired Power Plant. China Plans Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2011. Available online: https://www.ccsn.org.cn/newweb/standardQuery?guid=61433&showDetail=true (accessed on 1 March 2012).

- GB/T 51141-2015; Assessment Standard for Green Retrofitting of Existing Building. China Construction Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2015. Available online: https://www.ccsn.org.cn/newweb/standardQuery?guid=8921f9c3-8d58-4370-b163-b08fe969f4c1&showDetail=true (accessed on 1 August 2016).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.