Abstract

This study examines LEED certification strategies for Existing Buildings 4.1 (LEED-EB v4.1)-certified office projects in major US cities and their relationship with local green building policies. LEED-EB v4.1 is the latest program with an appropriate sample size to conduct significance tests and draw robust statistical inferences. LEED-EB v4.1 features six performance indicators: “transportation”, “water”, “energy”, “waste”, “indoor environmental quality (IEQ)”, and “overall LEED”. The purpose of this study was to evaluate LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects in San Francisco (SF), New York City (NYC), and Washington, D.C. (DC). Exact Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney and Cliff’s δ tests were used to compare the same LEED variables between two cities. Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation tests were used to assess the strength/direction between two LEED variables, and a simple linear regression (SLR) model was applied to predict the overall LEED variable. It was found that SF outperforms NYC in “IEQ” (δ = 0.53 and p = 0.009) and outperforms both NYC and DC in “overall LEED” (δ = 0.66 and p = 0.001; δ = 0.59 and p = 0.001). “Energy” and “waste” were positively and significantly correlated with “overall LEED” in NYC (r = 0.61 and p = 0.001; r = 0.40 and p = 0.044, respectively) and DC (r = 0.83 and p < 0.001; r = 0.65 and p = 0.009, respectively). The SLR results showed that one-point increases in “energy” and “waste” scores resulted in an increase in NYC’s overall LEED scores by approximately 0.78 and 1.72 points, respectively, and one-point increases in “energy” and “waste” scores resulted in an increase in DC’s overall LEED score by approximately 0.96 and 1.97 points, respectively. It is hypothesized that the difference in the “IEQ” of LEED-EB-certified office buildings between SF and NYC may be due to differences in these cities’ green building policies. According to the “overall LEED” indicator, office buildings in SF are more sustainable than those in NYC and DC. “Energy” and “waste” showed a stronger positive relationship with “overall LEED” in NYC and DC than the other indicators. However, the correlation analysis for SF presented in the Limitations Section is speculative due to the small sample size (n = 11).

1. Introduction

1.1. Energy Consumption and Share of Fossil Fuels in the US Building Sector

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the total energy consumption contributed by the building sector (the sum of residential and commercial projects) fell between 40.2% and 36.9% of the total U.S. energy consumption between 2010 and 2024 [1]. The share of fossil fuels (total natural gas, petroleum, and coal) varied between 92.8% and 91.4% of the total energy consumption of the building sector during this time [1].

Although the building sector’s share of total US energy consumption from fossil fuels declined between 2010 and 2024, the latter remains significant. The use of fossil fuels to meet energy needs can lead to a depletion in natural resources and contribute to climate change, resulting in a deterioration in people’s quality of life [2,3]. Considering this, the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) green building rating system is a valuable tool, developed and actively used in the USA, for reducing the use of fossil fuels [4,5].

1.2. Development of LEED Systems

The LEED program is constantly evolving through the introduction of new systems and/or versions [6]. Below are two examples describing a new application of an “old” system and the replacement of the “old” version with a “new” version.

LEED for Existing Buildings (LEED-EB) was originally designed as a program to follow up LEED for New Construction and Major Renovation (LEED-NC)-certified buildings. However, LEED-EB has evolved into a standalone certification system for existing buildings, aimed at improving their environmental sustainability without performing major renovations [7].

Before explaining the differences between the two versions (v4 and v4.1 of the LEED-EB system), it is worth noting that they both include five key indicators: “transportation” (from the location and transportation (LT) category), “energy” (from the energy and atmosphere (EA) category), “water” (from the water efficiency (WE) category), “materials and resources” or “waste” (from the materials and resources (MR) category), and “indoor environmental quality” (IEQ) (from the indoor environmental quality (EQ) category). Recently, the author of this study presented a detailed description of the two versions (v4 and v4.1) of the LEED-EB system in two studies [8,9]. LEED-EB v4.1 features the following performance indicators: “transportation”—14 pts; “water”—15 pts; “energy”—33 pts; “waste”—8 pts; and “IEQ”—20 pts. Additionally, LEED-EB v4.1 has 10 binary LEED credits, each worth a maximum of one point. Four certification levels are featured: certified (40–49 points), silver (50–59 points), gold (60–79 points), and platinum (80–100 points) [9].

1.3. LEED-EB v4 vs. v4.1

Yezioro and Capeluto applied a “prescriptive–descriptive” and “performance” approach for the Israeli Energy Standard (IS5282) [10]. It is important to note that LEED-EB v4 (the “old” version) primarily uses a “prescriptive–descriptive” approach (i.e., scores are recorded by measuring pre-set requirements related to performance), and LEED-EB v4.1 (the “new” version) primarily uses a “performance” approach (i.e., scores are recorded by directly measuring performance). In LEED-EB v4, three indicators—transport, materials and resources, and indoor environmental quality—are assessed using a “prescriptive–descriptive” approach, and two indicators—water and energy—are assessed using a “performance” approach. In LEED-EB v4.1, four indicators (transportation, water, energy, and waste) are assessed via a “performance” approach, while one indicator (indoor environmental quality) is assessed via a “performance” approach to determine 50% of the points; a “prescriptive–descriptive” approach is used to determine the remaining 50% of the points [11].

A major drawback of studies on LEED-certified projects is their design; in particular, it is necessary to determine whether the LEED system or version and the location of the LEED-certified project can influence the choice of certification strategy. Additionally, once an LEED system and version is selected, such as LEED-EB v4.1, the LEED certification level (certified, silver, gold, or platinum) may also influence the choice of LEED certification strategy.

Wu et al. examined all LEED 2009-certified projects registered as of July 2015 ([12], p 372). However, projects certified to the LEED v3 2009 standard from this date were distributed across 10 rating systems, of which three—LEED-NC, LEED-CI, and LEED-EB—accounted for approximately 33%, 24%, and 22%, respectively, of the total number of projects [13]. It can be assumed that each of the three systems, LEED-NC, LEED-CI, and LEED-EB, has unique LEED certification strategies.

Chen and Gou collected LEED-certified projects in 2017, 2019, and 2021 and examined how these projects varied by location and time in the United States [14]. However, during this period, the balance between versions 3 and 4 changed significantly. For example, according to the most popular LEED-NC system, the share of projects certified under version 4 increased from 0.8% in 2017 to 6.2% in 2029 and to 35.5% in 2021 [13]. LEED v4-certified projects have recently been shown to be more adaptable than LEED v3-certified projects for geographic location and environmental performance [15]. Therefore, the LEED version should be included in the study design.

Pushkar studied LEED-CI v4 gold-certified projects in California. San Francisco, which has a high percentage of public transit use, scored highly in location and transportation, while the energy and atmosphere category scored low. Meanwhile, in Sunnyvale, which has a low public transit use percentage, the opposite is true [16].

Goodarzi and Berghorn combined the four LEED certification levels (platinum, gold, silver, and certified (i.e., four independent groups)) into one group to study the relationship between walk, transit, and bike scores (i.e., built environment) and the overall LEED score [17]. However, Pushkar found that the relationship between the built environment and each certification level had unique characteristics [18]. Therefore, the level of LEED certification should be included in the study design as a significant factor.

Consistently following the above steps when selecting LEED-certified projects helps minimize the influence of uncontrollable factors on the evaluation of LEED certification strategies. The research question is as follows: Do LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects vary across US cities, given that LEED is based on a philosophy of sustainability? If differences are found between cities, the strengths and weaknesses can be identified, for example, in local green building policies. The structure of this article is as follows: Literature Review (Section 2), Materials and Methods (Section 3), Results section (Section 4), Discussion section (Section 5), Conclusions (Section 6), Limitations (Section 7), and References.

2. Literature Review

2.1. A Comparative Analysis of LEED-Certified Projects in the United States

2.1.1. At the Country Level

Several studies (2009–2019) by Cidell and Beata [19], Wu et al. [20], Wu et al. [12], and Pushkar and Verbitsky [21] used descriptive and inferential statistics to estimate the difference between LEED-certified strategies for LEED v2.2-, v3-, and v4-certified projects in the United States. They found that LEED certification strategies depended on both internal (e.g., certification level and building type) and external (e.g., climate, location, and U.S. state-level green policies) properties. In 2025, Ahmad et al. [22] used descriptive and inferential statistics to evaluate the difference in LEED-NC v4-certified projects across nine U.S. climate regions (i.e., nine independent groups). Thus, analyzing each new version (e.g., v4) using standard statistical methods (e.g., nonparametric significance and effect size tests) is a relevant scientific approach [22].

2.1.2. At the Level of Two Countries

Da Silva and Ruwanpura [23] used descriptive statistics to compare LEED-certified projects between the US and Canada. Wu et al. [24], Pushkar [15], and Chi et al. [25] used effect size and significance tests to compare LEED-certified projects between the US and China. They found that the differences between these countries are driven by factors such as climate, regional priorities, infrastructure, and the experience of LEED professionals. In this context, the two countries are represented as independent groups.

2.1.3. At the Building-Type Level

Rokde et al. [26] studied LEED-NC 2009 v3-certified fire station projects in the United States and showed that they scored poorly in both the MR and EA categories. They also identified 95 LEED-certified fire stations evenly allocated across the United States, with no significant regional trends. Goodarzi et al. [27] studied LEED NC v2009-certified hotel projects with normalized guest satisfaction scores in the United States. They found that EA and IEQ were the most important LEED categories for predicting satisfaction at the certified and silver certification levels, but not at the gold and platinum levels. Goodarzi and Berghorn [28] surveyed residents of LEED-certified communities and showed that green building characteristics significantly contributed to satisfaction compared to neighborhood design. Lee [29] examined five art museums in the United States certified under both LEED and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and showed that LEED and SDGs act as complementary frameworks to promote the environmental, social, and economic sustainability of museums.

2.1.4. At the US State and City Levels

Pushkar [16] studied LEED-CI v4 gold-certified office projects in California and found that cities with accessible public transportation (e.g., San Francisco) had high scores in the LT category and low scores in the EA category; the opposite was true for cities with non-accessible public transportation (e.g., Sunnyvale). Pushkar [30] studied LEED-CI v4 gold-certified office projects in New York City and found consistently high scores for the LT category, while the EA category had both low and high scores. A critical analysis of the above studies showed that a comparison of LEED-certified projects at the city level is lacking.

2.1.5. Summary of the Key Studies Analyzed

Table 1 summarizes four publications on the different LEED certification strategies in the United States. Climate zones influence the choice of LEED certification strategy; however, this approach does not consider the impact of green building policies on the choice of LEED certification strategy at both the state and city levels in the United States. The LEED certification level is a factor when choosing an environmentally and economically sustainable model for hotels. However, this approach does not consider the city in which LEED-certified hotels are located from a green building policy perspective. Transport accessibility (low or high) can significantly influence the choice of LEED certification strategy. In addition, the energy efficiency of a building (low or high) can be a key determinant of its green building performance, even within a single city [31]. The LEED certification strategy of different cities across the US has not yet been studied.

Table 1.

Comparison of four types of LEED-certified projects in the US.

2.2. A Correlation Analysis of LEED-Certified Projects in the United States

This subsection analyzes six studies that assessed the linear correlation between LEED category scores and overall LEED scores in the United States. Some studies used the correlation coefficient (r), while others used the coefficient of determination (R2) to assess correlation. To maintain consistency with the format used in the present study, R2 was transformed into r.

2.2.1. At the Country Level

Ahmad et al. ([22], p.14) analyzed 1252 LEED-NC v4-certified projects and found that the EA score has a strong positive correlation with the overall LEED score (r = 0.61). The regional priority (RP) score was moderately positively correlated with the overall LEED score (r = 0.40), while the MR, IEQ, SS, LT, and WE scores were weakly positively correlated with the overall LEED score (r = 0.39, 0.37, 0.36, 0.35, and 0.30, respectively). This correlation reflects the general trend in the United States. However, city-level LEED certification strategies or strategies used in different climates remain unexplored. Ahmad et al. ([22], p.13) noted “that in certain [climate] regions, building practices may foster stronger connections, [i.e., moderate correlation] between specific categories”. Combining the four LEED certification levels (i.e., four independent groups) into one group also obscures the LEED certification strategies used for each LEED certification level.

2.2.2. At the Building-Type Level

Goodarzi et al. [32] analyzed 87 LEED-NC v3 2009-certified university residence hall projects. They found a strong positive correlation between the EA score and the overall LEED score (r = 0.80). The SS score was moderately positively correlated with the overall LEED score (r = 0.45), and the MR, IEQ, and WE category scores were weakly positively correlated with the overall LEED score (r = 0.35, 0.28, and 0.28, respectively).

Goodarzi [33] examined 802 LEED-NC v3 209-certified multifamily residential projects. They discovered the following relationships: a strong positive correlation between the EA category scores and the overall LEED score (r = 0.68) and a moderate positive correlation between the SS score and the overall LEED score (r = 0.40). The EQ, WE, and MR scores were weakly positively correlated with the overall LEED score (r = 0.26, 0.25, and 0.23, respectively).

Goodarzi et al. [34] also examined the correlation between RP credits and overall LEED points in 878 LEED-NC 2009 v3-certified multifamily residential projects. They identified a weak positive correlation between the RP score and overall LEED score (r = 0.38).

Goodarzi and Garshasby [35] examined 75 LEED-NC v4-certified multifamily residential projects, finding that the EA, EQ, and LT scores were moderately positively correlated with the overall LEED score (r = 0.52, 0.43, and 0.43, respectively). By contrast, the SS, WE, and MR scores were positively weakly correlated with the overall LEED score (r = 0.28, 0.23, and 0.20, respectively).

Parekh [36] examined 120 LEED-HC v4.1-certified healthcare projects and found a strong positive correlation between the EA score and the overall LEED score (r = 0.60). The WE and SS scores were moderately positively correlated with the overall LEED score (r = 0.58 and 0.46, respectively), and the IEQ and MR scores were weakly positively correlated with the overall LEED score (r = 0.39 and 0.33, respectively). This clearly indicates that LEED-certified projects at different certification levels are pooled into one group. Thus, the presented r values do not reflect the degree of correlation between individual and overall LEED scores in each of the four certification groups. This study design does not allow for an examination of LEED certification strategies at the city level.

2.2.3. Summary of the Key Studies Analyzed

Table 2 shows that the correlation between the EA score and the overall LEED score varies widely from r = 0.52 for LEED-NC v4-certified multifamily residential projects to r = 0.80 for LEED-NC v3-certified university residence hall projects. Table 2 also shows that the correlation between the WE score and the overall LEED score varies widely from r = 0.23 for LEED-HC v4-certified multifamily residential projects [35] to r = 0.58 for LEED-HC v4.1-certified healthcare projects [36].

Table 2.

A summary of the correlation results between individual LEED category points and total LEED points in the United States across six publications using the correlation coefficient (r).

Notably, the correlation coefficients of LEED-NC v4-certified projects across all building types are approximately average when assessing the correlation between individual LEED category scores and the overall LEED score. No studies have examined city-level LEED-certified projects in the United States to identify the LEED certification strategies used in specific cities.

2.3. LEED-Certified Projects and Urban–Rural Classification

According to Ingram and Franco [37], the National Center for Health Statistics’ (NCHS) six-level urban–rural classification, presented in Table 3, is commonly used to study the relationship between the urbanization level of a place of residence and residents’ health status, as well as to monitor the health status of urban and rural residents.

Table 3.

National Center for Health Statistics’ (NCHS) urban–rural classification in the United States.

Smith [38], who first analyzed the distribution of LEED-certified projects in the United States using the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) urban–rural classification, identified that these LEED-certified projects are distributed as follows: 57.1% in “Large central metros”; 16.1% in “Large fringe metros”; 15.6% in “Medium metros”; 7.6% in “Small metros”; 1.8% in “Micropolitan”; and 1.8% in “Noncore” areas. Recently, Pushkar [18] studied LEED-EB v4-certified office projects in the United States and showed that these projects are predominantly located in “Large central metro” counties and not in “Large fringe metro” counties: 75.0—22.8% at the platinum level; 89.3—8.9% at the gold level; 78.3—17.3% at the silver level; and 79.4—17.7% at the certified level. In rare cases, LEED-EB v4-certified office projects were found in “Medium metro”, “Small metro”, “Micropolitan”, and “Noncore” cities. However, when evaluating LEED-certified projects, the urban–rural classification should also be considered.

2.4. Research Gap

The LEED-EB v4.1 system, currently used to certify office buildings, will also guide future green building trends in existing buildings to better mitigate climate change, conserve resources, and improve occupant health. The LEED-EB v4.1 system measures five key performance indicators: “transportation”, “water”, “energy”, “waste”, and “IEQ”. The LEED-EB v4.1 “transport”, “water”, “energy”, and “waste” indicators are directly responsible for mitigating climate change and conserving resources, and the “IEQ” indicator is directly responsible for improving human health. Felgueiras et al. indicated that improving IEQ components positively impacts well-being, health, and productivity in office workers [39]. However, there is a significant research gap regarding the “IEQ” performance indicator in LEED-EB certification strategies in major US cities. This gap is particularly relevant given the growing recognition of the impact of IEQ on the well-being, health, and productivity of office workers in LEED-EB-certified office buildings.

The 2025 studies by Ahmad et al. [22] and Pushkar [9] are the closest analogs of the current study. Ahmad et al. [22] used both comparative analysis (i.e., comparison across nine climate zones) and correlation analysis (i.e., correlation analysis within each of the nine climate zones) to study LEED-NC v4-certified projects in the United States. Pushkar [9] performed a comparative analysis (i.e., comparison across six countries) on LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified projects in the Mediterranean and Europe. However, comparative analysis across US cities, as well as correlation and regression analyses between individual indicators and overall LEED performance in each US city, has not yet been conducted for LEED-EB v4.1-certified projects.

2.5. Purpose and Objectives of This Study

The purpose of this study is to evaluate LEED-EB v4.1gold-certified office projects and determine which of the three cities—San Francisco, New York City, and Washington, D.C.—are using the LEED IEQ certification strategy. The first objective of this study is to conduct a pairwise comparison of the same LEED indicators among LEED-certified projects in San Francisco, New York City, and Washington, DC. The second objective is to conduct correlation and regression analyses between individual LEED performance indicators (independent variables) and the overall LEED performance indicator (dependent variable) for LEED-EB v4.1-certified projects within the three abovementioned cities.

2.6. Novelty and Contribution

This study contains a new methodological approach to studying LEED certification strategies, which uncovered a previously unknown result: San Francisco outperforms New York City with regard to the IEQ performance of LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office buildings. This study contributes to the literature: its findings should help LEED professionals better define LEED certification strategies and understand the factors that contribute to higher IEQ scores in office buildings.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Flow Chart of the Study

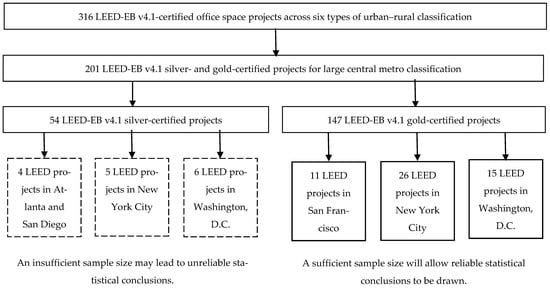

Figure 1 presents a step-by-step flow chart of the study, including data collection, selection, and analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study. Boxes with dotted lines indicate sample sizes that are inappropriate for significance tests. Boxes with solid lines indicate sample sizes appropriate for significance tests.

Data was collected from 316 LEED-EB v4-certified office projects in the United States in three stages: In the first stage, 201 LEED-certified projects with leading certification levels (“silver” and “gold”) and a dominant location in the metropolitan county (“large central metro”) were selected. In the second stage, these projects (54 and 147 LEED silver- and gold-certified projects, respectively) were divided into two groups. In the third phase, projects were separated by city: LEED silver-certified projects were primarily distributed in four cities (four projects each in Atlanta and San Diego, five projects in New York City, and six projects in Washington, D.C.), while LEED gold-certified projects were primarily distributed in three cities (11 projects in San Francisco, 26 projects in New York City, and 15 projects in Washington, D.C.). Then, office projects in San Francisco, New York City, and Washington, D.C., that were LEED v4.1 gold-certified were statistically analyzed using significance tests. The study design and data collection, selection, and analysis are presented in more detail in Section 3.2, Section 3.3, Section 3.4 and Section 3.5, respectively.

3.2. Study Design

To compare LEED-EB v4.1 data between the two US cities, the nonparametric exact Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test was used instead of the parametric t-test because LEED-EB v4.1 contains “tied” data and for two groups the minimum sample sizes (n1 and n2) should be n1 = n2 > 10, where n1 + n2 > 23, to obtain reliable statistical inferences [40,41].

Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation test was used to measure the correlation coefficient (i.e., the strength and direction of a linear or monotonic relationship between two variables if the linearity form is met) between each of the five LEED performance indicators and the overall LEED score within one US city’s LEED-certified projects. If the assumptions of homoscedasticity and/or normality of the residual distribution are met, then Pearson’s test is chosen; otherwise, Spearman’s test is used. The minimum sample size required to conduct a Pearson or Spearman correlation analysis and obtain reliable statistical inferences should be n > 14 [42]. A simple linear regression model was used to predict the overall LEED variable. The interpretation of the correlation coefficient, the coefficient of determination, and the significance of the relationship are presented in Section 3.5.4 and Section 3.5.5, and Section 3.5.7, respectively.

LEED-certified projects required the following design criteria: cities must be in the same country (i.e., the US) and “metropolitan county” (i.e., a “large central metro”) and have the same LEED system (i.e., LEED-EB), LEED version (i.e., v4.1), and certification level (i.e., gold or silver).

3.3. Data Collection

As shown in Table 4, 316 LEED-EB v4.1-certified office projects were identified in the United States [43,44]. LEED data were divided into four certification levels and six urban and rural classification types, showing that projects were generally gold-certified and located in medium, large fringe, and large central metropolitan counties.

Table 4.

Allocation of LEED-EB v4.1-certified office projects across six types of urban–rural classifications.

3.4. Data Selection

Table 5 lists the most common cities for LEED-EB v4.1 silver- and gold-certified office projects. At the silver level, all five cities have sample sizes ranging from 2 to 6, which is significantly smaller than the size needed to draw reliable statistical conclusions. At the gold level, three cities, namely San Francisco, New York City, and Washington, D.C., have sample sizes of 11, 26, and 15, respectively, within the sample size range, which can be used to draw reliable statistical inferences for pairwise comparison. However, for San Francisco, the sample size is below the minimum value required to draw reliable statistical conclusions when conducting correlational analysis. Therefore, the results of the correlation analysis for San Francisco should be treated with caution. Two complete lists of cities with at least one LEED-EB v4.1 silver- or gold-certified project in one metropolitan county (i.e., medium metro, large fringe metro, and large central metro) are presented in Appendix A, Table A1 and Table A2.

Table 5.

Allocation of LEED-EB v4.1 silver- and gold-certified office projects among the most popular cities located in “large central metro” counties.

3.5. Data Analysis

In this study, a comparative analysis of independent groups and a correlation analysis of two variables were conducted. Statistical processing of LEED data was performed using MATLAB 2024a [45].

3.5.1. Comparative Analysis of Independent Groups

Recently [9,22], it has been demonstrated that the assumption of normality does not apply to LEED data. In this study, nonparametric statistics, including the median, 25th–75th percentiles, and interquartile range-to-median ratio (IQR/M), were used to analyze LEED data in terms of descriptive statistics. The exact Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney [40] and Cliff’s δ effect size [46] tests were used to compare two independent groups with LEED data to determine the p-value (i.e., statistical significance) and effect size magnitude (i.e., substantive significance), respectively.

3.5.2. Correlation Analysis of Two Variables

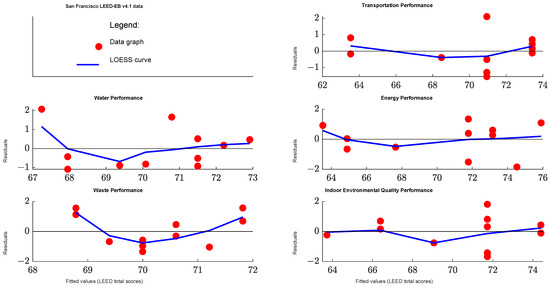

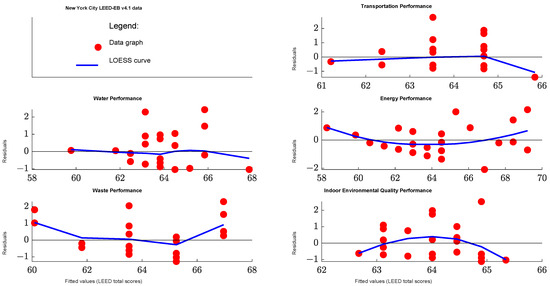

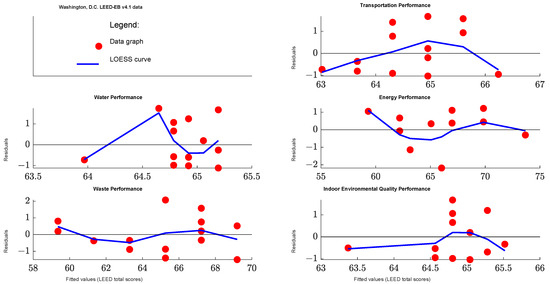

To determine which type of correlation (e.g., parametric Pearson’s correlation or nonparametric Spearman’s correlation) to use when analyzing the relationship between two variables containing interval data, the five Gauss–Markov assumptions (i.e., linearity in form, no correlation between residuals and independent variables, absence of autocorrelation in residuals, homoscedasticity, and normality in residual distribution) must be tested [47]. Linearity in form was determined by superimposing a locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) curve on the residuals versus plotting fitted values. If an LOESS curve is approximately clustered around the zero-horizontal line, then the relationship between the two variables is linear [48]. The results showed that the assumption of linearity in form was met in all cases (Appendix A, Figure A1, Figure A2 and Figure A3).

The next step was to test the remaining four Gauss–Markov assumptions. If these four assumptions were met, Pearson’s test could be applied; if only one of them was not met, Spearman’s test was applied. If judgment regarding any assumption was suspended, it was interpreted as not meeting the criteria (Appendix A, Table A3).

3.5.3. Effect Size Interpretation

Table 6 shows the bounds for the effect sizes of Cliff’s δ, which range between −1 and +1.

Table 6.

Cliff’s δ effect sizes for absolute value.

Cohen [50] defined the effect size (i.e., practical significance) as follows: a medium effect is visible to the naked eye of an attentive observer; a small effect is noticeably smaller than the medium effect but not negligible; and a large effect is the same distance above the medium as a small effect is below it. Some authors have noted that effect size is not a strict criterion, especially under conditions of limited knowledge [51,52]. The interpretation of effect sizes in the field of LEED-certified projects especially requires further research.

3.5.4. Correlation Coefficient Interpretation

Pearson’s correlation coefficient (rp) measures the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two variables. In comparison, Spearman’s correlation coefficient (rs) measures the strength and direction of the monotonic association between two ranked variables [53]. The coefficients (rp and rs) range from +1 to −1, where +1 indicates a perfect positive relationship; −1 indicates a perfect negative relationship; and 0 indicates no relationship. Table 7 demonstrates the absolute strength of a relationship between two variables and its interpretation using five levels of strength.

Table 7.

Interpretation of the correlation coefficient for absolute value (|r|).

3.5.5. Interpretation of Coefficient of Determination (R2) and Simple Liner Regression Model

The coefficient of determination (R2) ranges from 0 to 1. An R2 of 1 indicates that the model explains all variability, with all data points on the regression line, whereas an R2 of 0 indicates that the model explains none of the variability. Table 8 shows the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variable in a regression model.

Table 8.

Interpretation of the coefficient of determination (R2).

The sample linear regression equation is typically written as

where ŷ is the predicted “overall LEED” score (dependent variable), b0 is the estimated value of the overall LEED score when an LEED performance indicator of 0 is used, and b1 is the average change in the overall LEED score for every one-unit increase in the LEED performance indicator. This equation is used to model the linear relationship between a single independent variable and a dependent variable based on observed sample data [56].

3.5.6. Median and IQR/M Interpretation

The median value of LEED-EB v4.1 performance indicators can be represented as low, medium, or high, corresponding to the maximum possible number of points. IQR/M ≤ 0.30 and IQR/M > 0.30 indicate low and high heterogeneity/homogeneity, respectively.

3.5.7. p-Value Interpretation

In this study, the significance level was defined as α = 0.05, and results are reported as “statistically significant” if p ≤ 0.05 or “statistically insignificant” if p > 0.05. A two-tailed p-value was used to interpret the results of all significance tests.

4. Results

This study addresses two research questions. The first is as follows: Is there a statistically significant difference between the three major US cities? In this context, five individual LEED performance indicators and the overall LEED score were defined as independent variables, and the USA cities, including San Francisco, New York City, and Washington, D.C., were defined as three independent groups. The second question is as follows: Is there a correlation and causality between individual LEED performance indicators (independent variables) and the overall LEED score (dependent variable)? The null hypothesis states that there is no difference (if p > 0.05) between the same LEED performance indicator in the three US cities, as well as no relationship (if p > 0.05) between individual LEED performance indicators and the overall LEED score in each of the three US cities. If the null hypothesis is rejected, then the alternative hypothesis is supported, which states that there is a difference (if p ≤ 0.05) between the same LEED performance indicator in the three US cities, as well as a relationship (if p ≤ 0.05) between individual LEED performance indicators and the overall LEED score in each of the three US cities.

4.1. Comparative Analysis of LEED Performance Indicators in LEED-Certified Projects

4.1.1. Transportation

Table 9 indicates high achievement levels in the “transportation” indicator (13.0, 12.0, and 12.0) and low IQR/M values (0.13, 0.08, and 0.17) in San Francisco, New York City, and Washington, D.C., respectively. Pairwise comparisons showed that the difference for “transportation” between San Francisco, New York City, and Washington, D.C., was not statistically significant.

Table 9.

“Transportation” indicator for LEED-EB v4.1-certified office projects in three US cities.

4.1.2. Water

Table 10 indicates moderate achievement levels for the “water” indicator (9.0, 8.0, and 8.0); high IQR/M values in San Francisco (0.50); and low IQR/M values in New York City and Washington, D.C. (0.25 and 0.22, respectively). Pairwise comparisons indicate that the difference between San Francisco, New York City, and Washington, D.C., for the “water” indicator was not statistically significant.

Table 10.

“Water” indicator for LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office space projects in three US cities.

4.1.3. Energy

Table 11 shows that the “energy” indicator transitioned between high-to-moderate achievement levels (23.0, 20.0, and 19.0) and low IQR/M values in New York City and Washington, D.C. (0.24, 0.25, and 0.26, respectively). Pairwise comparisons indicate that the difference between San Francisco, New York City, and Washington, D.C., for “energy” was not statistically significant.

Table 11.

“Energy” indicator for LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office space projects in three US cities.

4.1.4. Waste

Table 12 indicates moderate achievement levels for the “waste” indicator (5.0, 5.0, and 6.0), and high IQR/M values (0.50, 0.40, and 0.33) in San Francisco, New York City, and Washington, D.C., respectively. Pairwise comparisons indicate that the difference between San Francisco, New York City, and Washington, D.C., for the “waste” indicator was not statistically significant.

Table 12.

“Waste” indicator for LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office space projects in three US cities.

4.1.5. Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ)

Table 13 indicates high achievement levels for the “IEQ” indicator (18.0, 16.0, and 16.0) and low IQR/M values (0.10, 0.19, and 0.11) in San Francisco, New York City, and Washington, D.C., respectively. San Francisco statistically significantly outperforms New York City, while no statistically significant difference was found between Washington, D.C., and New York City for the “IEQ” indicator.

Table 13.

“IEQ” indicator for LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office space projects in three US cities.

4.1.6. Overall LEED

Table 14 shows that the “overall LEED” variable significantly exceeds the minimum value (60.0) required to achieve gold certification in San Francisco (69.0) and slightly exceeds the minimum in New York City (62.0) and Washington, D.C. (62.0). IQR/M showed low values (0.13, 0.11, and 0.15) in San Francisco, New York, and Washington, D.C., respectively. San Francisco statistically significantly outperforms New York City and Washington, D.C., while no statistically significant difference was found between Washington, D.C., and New York City in terms of overall LEED.

Table 14.

“Overall LEED” of LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office space projects in three US cities.

4.2. Correlation and Linear Regression Analyses Between Individual LEED Performance (Independent Variable) and Overall LEED Score (Dependent Variable) in LEED-Certified Projects

4.2.1. New York City

Table 15 shows that “energy” and “waste” exhibit positive and statistically significant correlations with “overall LEED”. A simple linear regression analysis shows that each additional point in the “energy” and “waste” indicators contributes approximately 0.78 and 1.72 points to the overall LEED score, respectively. An R2 of 0.47 means that 47% of the variance in the “energy” variable is predicted by the overall LEED variable in the model, while the remaining 53% is unexplained by the model’s input. An R2 of 0.19 means that 19% of the variance in the “waste” variable is predicted by the overall LEED variable in the model, while the remaining 81% is unexplained by the model’s input.

Table 15.

Correlation and linear regression analyses between each of the five “individual LEED” indicators and “overall LEED” for LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects in New York City.

4.2.2. Washington, D.C.

Table 16 shows that “energy” and “waste” exhibit positive and statistically significant correlations with the “overall LEED” variable. A simple linear regression analysis shows that each additional point for the “energy” and “waste” indicators contributes approximately 0.96 and 1.97 points to the overall LEED score, respectively. An R2 of 0.68 means that 68% of the variance in the “energy” variable is predicted by the overall LEED variable in the model, while the remaining 32% is unexplained by the model’s input. An R2 of 0.42 means that 42% of the variance in the “waste” variable is predicted by the overall LEED variable in the model, while the remaining 58% is unexplained by the model’s input.

Table 16.

Correlation and linear regression analyses between each of the five “individual LEED” indicators and “overall LEED” for LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects in Washington, D.C.

The results of simple linear regression analyses for two pairs of variables (i.e., “energy” vs. “overall LEED performance” and “waste” vs. “overall LEED performance”) for New York City and Washington, D.C., respectively, are presented in standard analysis of variance (ANOVA) and standard regression analysis tabular forms (Appendix A, Table A4, Table A5, Table A6, Table A7, Table A8, Table A9, Table A10 and Table A11). The interpretability of the results for the simple linear regression analyses of indicators, such as “transportation”, “water”, and “IEQ” with the “overall LEED” score for both New York City and Washington, D.C., is unreliable since there is no significant correlation between these two variables.

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparative Analysis

San Francisco outperforms New York City in IEQ, likely due to at least two factors: the age of the office buildings and local environmental policies. In the context of this study, i.e., for LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects, the average year of construction in New York City was 1948, and in San Francisco, it was 1968 (preliminary, unpublished data). The age of office buildings is a significant, indirect factor influencing the IEQ [39]. From a local environmental policy perspective, this is likely due to San Francisco’s stricter city codes, which often exceed state and federal standards, particularly regarding ventilation in commercial spaces (e.g., [57,58]).

It should be noted that “IEQ” is an important indicator that can be used to improve occupants’ quality of life and increase property value [59]. As mentioned earlier, the IEQ score depends not only on CO2 and TVOC measurements (objective measures: 50% of the IEQ score), but also on occupant satisfaction ratings (subjective measures: 50% of the IEQ score) [11]. The effectiveness of subjective assessments depends on both the quality of the survey design (the types of questions included) and how and when the questions are asked [60]. In conclusion, the IEQ value may vary across projects due to differences in subjective perception between individuals in the building, despite physical measurements being the same.

The “overall LEED” in San Francisco was higher (median: 69.0 points) compared to New York City and Washington, D.C. (median: 62.0 in both cities) (Table 14). San Francisco’s higher overall LEED score contrasts with the much lower overall LEED scores (median: 62–65 points) measured in previous research, which studied projects certified under previous LEED-EB versions (3 and 4) [61]. However, this result aligns with previously published LEED-EB v4.1 gold certification results for European countries, such as Ireland, Germany, Italy, and Spain (median: 69.5–70.5 points) [9]. It can be concluded that measuring all main LEED-EB v4.1 indicators leads to promising results, as key factors such as “transportation”, “water”, “energy”, “waste”, and “IEQ” are addressed. This contrasts with the previous LEED-EB v4 version, where only “water” and “energy” were measurable indicators.

5.2. Simple Correlation and Linear Regression Analyses

The correlation between “energy” and “overall LEED” has been well established in the literature [22,32,33,35,36], as the number of points is the highest for this indicator [22]. Regarding the “waste” indicator, in the US, many municipalities have initiated policies to reduce solid waste entering landfills. For example, New York City aims to send zero waste to landfills by 2030 [62].

A simple linear regression model showed a causal relationship between the “energy” performance (independent variable) and the “overall LEED” score (dependent variable), and between the “waste” performance (independent variable) and the “overall LEED” score (dependent variable) in both New York City and Washington, D.C.

The expected positive causal relationship was realized through the fact that higher energy performance indicators (EPIs) generally correlate with higher overall LEED scores, particularly in the LEED-EB rating systems. The current LEED-EB v4.1 system is heavily data-driven and performance-based, making this link explicit [63,64].

It can be hypothesized that the positive causal relationship between the “waste” metric and overall LEED score occurs because LEED-EB v4.1 shifts the assessment from a prescriptive approach to a data-driven and performance-based methodology [11].

6. Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to evaluate LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects in the United States at the city level. Based on comparative and correlation analyses between three cities and within each individual city, the conclusions drawn are as follows:

- Comparative analysis found that San Francisco outperforms New York City for the “IEQ” performance indicator of LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects. San Francisco also outperforms New York City and Washington, D.C., for the “overall LEED” score, demonstrating the higher environmental sustainability of its LEED-certified buildings. No significant differences were found between San Francisco, New York City, and Washington, D.C., for four of the five key performance indicators (“transportation”, “water”, “energy”, and “waste”).

- Correlation analysis showed that two indicators (i.e., “energy” and “waste”) were positively and significantly correlated with “overall LEED” in New York City and Washington, D.C. In contrast, “transportation”, “IEQ”, and “water” were not significantly correlated with “overall LEED” in these two cities.

- Simple linear regression analysis showed that each additional point in the “energy” and “waste” indicators contributes approximately 0.78 and 1.72 points to the overall LEED score, respectively, in New York City LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects. Simple linear regression analysis also showed that each additional point in the “energy” and “waste” indicators contributes approximately 0.96 and 1.97 points to the overall LEED score, respectively, in LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects in Washington, D.C.

Future research should apply network analysis to LEED-certified projects. This will provide LEED professionals with an effective decision-making framework for green building certification [65].

7. Limitations

Table 17 presents the results of the correlation test between the five individual LEED-EB v4.1 performance indicators and the overall LEED performance indicator for San Francisco. This is presented only as a preliminary finding due to the small sample size (n = 11) used to conduct the correlation test. The data show that “energy”, “transportation”, and “IEQ” exhibit positive and statistically significant correlations with “overall LEED” in San Francisco, while “water” and “waste” exhibit statistically insignificant correlations with “overall LEED”.

Table 17.

Correlation between “overall LEED” and each of the five “individual LEED” indicators in LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects in San Francisco.

It is hypothesized that the positive and statistically significant correlation between “transportation” and “overall LEED” in San Francisco might be due to the California Global Warming Solutions Act [66,67]. To test this hypothesis, it is necessary to analyze feedback from users of office buildings certified as LEED-EB v4.1 gold to determine whether they changed their commuting patterns between home and work and vice versa. It is also hypothesized that the positive and statistically significant correlation of three of the five key LEED-EB v4.1 performance indicators, i.e., “energy”, “transportation”, and “IEQ”, with “overall LEED” in San Fransico could be attributed to the synergistic effects of the Health Code Article 38 [57], the California Green Building Standards Code [68], and the California Global Warming Solutions Act [66,67].

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

LEED-EB 4.1 silver-certified office projects for the US cities (listed alphabetically).

Table A1.

LEED-EB 4.1 silver-certified office projects for the US cities (listed alphabetically).

| City, US State | Medium Metro | Large Fringe Metro | Large Central Metro |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albuquerque, New Mexico | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Arlington, Virginia | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Atlanta, Georgia | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Austin, Texas | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Bellevue, Washington | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Boston, Massachusetts | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Boulder, Colorado | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Broomfield, Colorado | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Cambridge, Massachusetts | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Charlotte, North Carolina | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Chelmsford, Massachusetts | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Chicago, Illinois | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Columbia, Maryland | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Downers Grove, Illinois | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Fairfax, Virginia | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Falls Church, Virginia | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Golden Valley, Minnesota | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hillsboro, Oregon | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Houston, Texas | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Indianapolis, Indiana | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Jersey City, New Jersey | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Littleton, Colorado | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| McLean, Virginia | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Miami, Florida | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Minneapolis, Minnesota | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Morrisville, North Carolina | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Nashville, Tennessee | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Needham, Massachusetts | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| New York City, New York | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Norfolk, Virginia | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Oakland, California | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Oregon, United States | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Park Ridge, Illinois | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Pinellas Park, Florida | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Plainsboro, New Jersey | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Quincy, Massachusetts | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Raleigh, North Carolina | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Reston, Virginia | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Richmond, Virginia | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Rosemont, Illinois | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Roswell, Georgia | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| San Antonio, Texas | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| San Diego, California | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| San Francisco, California | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| San Jose, California | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Santa Clara, California | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Sarasota, Florida | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Scottsdale, Arizona | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sugar Land, Texas | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Tampa, Florida | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Washington, D.C. | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Weston, Florida | 0 | 4 | 0 |

Table A2.

LEED-EB 4.1 gold-certified office projects for the US cities (listed alphabetically).

Table A2.

LEED-EB 4.1 gold-certified office projects for the US cities (listed alphabetically).

| City, US State | Medium Metro | Large Fringe Metro | Large Central Metro |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alexandria, Virginia | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Anaheim, California | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Arlington, Virginia | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Atlanta, Georgia | 0 | 5 | 2 |

| Austin, Texas | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Baltimore, Maryland | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Bethesda, Maryland | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Beverly Hils, California | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Blaine, Minnesota | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Boca Raton, Florida | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Boston, Massachusetts | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Bradenton, Florida | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Burlington, Massachusetts | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Cambridge, Massachusetts | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Chandler, Arizona | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Charlotte, North Carolina | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Chicago, Illinois | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Cincinnati, Ohio | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Clearwater, Florida | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Colorado Springs, Colorado | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Dallas, Texas | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Decatur, Georgia | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Denver, Colorado | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Fairfax, Virginia | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Franklin, Tennessee | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Golden Valley, Minnesota | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Greenbrae, California | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Hillsboro, Oregon | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Honolulu, Hawaii | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Houston, Texas | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Indianapolis, Indiana | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Irving, Texas | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Lake Mary, Florida | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Las Vegas, Nevada | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Lehi, Utah | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Los Angeles, California | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| McLean, Virginia | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Miami, Florida | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Milwaukee, Wisconsin | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Minneapolis, Minnesota | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Miramar, Florida | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Morrisville, North Carolina | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Mountain View, California | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Needham, Massachusetts | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| New York City, New York | 0 | 0 | 26 |

| Newton, Massachusetts | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Norfolk, Virginia | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Oakland, California | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Orlando, Florida | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Palo Alto, California | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Pasadena, California | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Phoenix, Arizona | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Pleasanton, California | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Portland, Oregon | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Raleigh, North Carolina | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Reston, Virginia | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| Richardson, Texas | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Richfield, Minnesota | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Rock Hill, South Carolina | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Salt Lake City, Utah | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| San Diego, California | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| San Francisco, California | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| San Jose, California | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sandy Springs, Georgia | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sarasota, Florida | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Seattle, Washington | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| St. Petersburg, Florida | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sterling, Virginia | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Sugar Land, Texas | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Tampa, Florida | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Washington, DC | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| Watertown, Massachusetts | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Figure A1.

LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects in San Francisco: residuals vs. fitted values plot. The curved line is a calculated LOESS curve, which shows the directions of the distortions from linearity.

Figure A2.

LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects in New York City: residuals vs. fitted values plot. The curved line is a calculated LOESS curve, which shows the directions of the distortions from linearity.

Figure A3.

LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified office projects in Washington, D.C.: residuals vs. fitted values plot. The curved line is a calculated LOESS curve, which shows the directions of the distortions from linearity.

Table A3.

p-values of the remaining four Gauss–Markov assumptions (A1–A4).

Table A3.

p-values of the remaining four Gauss–Markov assumptions (A1–A4).

| Performance | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US city | Variable 1 | Variable 2 | ||||

| San Francisco | Overall LEED vs. | Transportation | 0.576 | 0.269 | 0.758 | 0.525 |

| Water | 0.252 | 0.989 | 0.120 | 0.060 | ||

| Energy | 0.612 | 0.432 | 0.148 | 0.514 | ||

| Waste | 0.524 | 0.064 | 0.649 | 0.240 | ||

| IEQ | 0.026 | 0.040 | 0.099 | 0.850 | ||

| New York City | Overall LEED vs. | Transportation | 0.194 | 0.327 | 0.572 | 0.003 |

| Water | 0.985 | 0.379 | 0.147 | 0.005 | ||

| Energy | 0.342 | 0.762 | 0.037 | 0.809 | ||

| Waste | 0.665 | 0.281 | 0.338 | 0.031 | ||

| IEQ | 0.100 | 0.631 | 0.153 | 0.002 | ||

| Washington, D.C. | Overall LEED vs. | Transportation | 0.563 | 0.741 | 0.408 | 0.015 |

| Water | 0.440 | 0.432 | 0.632 | 0.032 | ||

| Energy | 0.238 | 0.158 | 0.901 | 0.116 | ||

| Waste | 0.390 | 0.251 | 0.298 | 0.584 | ||

| IEQ | 0.356 | 0.774 | 0.800 | 0.029 | ||

Note: A1, no correlation between residuals and independent variables; A2, absence of autocorrelation in residuals; A3, homoscedasticity; and A4, normality in residual distribution. Bold font: the Gauss–Markov assumption does not hold; ordinal font: the Gauss–Markov assumption holds.

Table A4.

ANOVA table. Simple linear regression analysis between “energy” and “overall LEED” for New York City LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified projects.

Table A4.

ANOVA table. Simple linear regression analysis between “energy” and “overall LEED” for New York City LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified projects.

| Source | Sum of Squares | Degrees of Freedom | Mean Square | F-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 250.1017 | 1 | 250.1017 | 21.4569 | 0.00011 |

| Error | 279.7445 | 24 | 11.6560 | ||

| Total | 529.8462 | 25 |

Table A5.

Regression table. Simple linear regression analysis between “energy” and “overall LEED’ for New York City LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified projects.

Table A5.

Regression table. Simple linear regression analysis between “energy” and “overall LEED’ for New York City LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified projects.

| Term | Coefficient | Standard Error | t-Statistic | p-Value | R2-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (b0) | 48.1341 | 3.4737 | 13.8568 | <0.00001 | |

| X (Scope b1) | 0.7804 | 0.1685 | 4.6322 | 0.00011 | 0.4720 |

Table A6.

ANOVA table. Simple linear regression analysis between “waste” and “overall LEED” for New York City LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified projects.

Table A6.

ANOVA table. Simple linear regression analysis between “waste” and “overall LEED” for New York City LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified projects.

| Source | Sum of Squares | Degrees of Freedom | Mean Square | F-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 102.1417 | 1 | 102.1417 | 5.7315 | 0.02483 |

| Error | 427.7044 | 24 | 17.8210 | ||

| Total | 529.8462 | 25 |

Table A7.

Regression table. Simple linear regression analysis between “waste” and “overall LEED” for New York City LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified projects.

Table A7.

Regression table. Simple linear regression analysis between “waste” and “overall LEED” for New York City LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified projects.

| Term | Coefficient | Standard Error | t-Statistic | p-Value | R2-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (b0) | 54.9378 | 3.8434 | 14.2941 | <0.00001 | |

| X (Scope b1) | 1.7178 | 0.7175 | 2.3941 | 0.02483 | 0.1928 |

Table A8.

ANOVA table. Simple linear regression analysis between “energy” and “overall LEED” for LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified projects in Washington, D.C.

Table A8.

ANOVA table. Simple linear regression analysis between “energy” and “overall LEED” for LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified projects in Washington, D.C.

| Source | Sum of Squares | Degrees of Freedom | Mean Square | F-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 229.2658 | 1 | 229.2658 | 27.9940 | 0.00015 |

| Error | 106.4675 | 13 | 8.1898 | ||

| Total | 335.7333 | 14 |

Table A9.

Regression table. Simple linear regression analysis between “energy” and “overall LEED” for LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified projects in Washington, D.C.

Table A9.

Regression table. Simple linear regression analysis between “energy” and “overall LEED” for LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified projects in Washington, D.C.

| Term | Coefficient | Standard Error | t-Statistic | p-Value | R2-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (b0) | 44.9638 | 3.8336 | 11.7289 | 0.00000003 | |

| X (Scope b1) | 0.9569 | 0.1809 | 5.2909 | 0.00015 | 0.68 |

Table A10.

ANOVA table. Simple linear regression analysis between “waste” and “overall LEED” for LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified projects in Washington, D.C.

Table A10.

ANOVA table. Simple linear regression analysis between “waste” and “overall LEED” for LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified projects in Washington, D.C.

| Source | Sum of Squares | Degrees of Freedom | Mean Square | F-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 140.8396 | 1 | 140.8396 | 9.3944 | 0.00903 |

| Error | 194.8938 | 13 | 14.9918 | ||

| Total | 335.7333 | 14 |

Table A11.

Regression table. Simple linear regression analysis between “waste” and “overall LEED” for LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified projects in Washington, D.C.

Table A11.

Regression table. Simple linear regression analysis between “waste” and “overall LEED” for LEED-EB v4.1 gold-certified projects in Washington, D.C.

| Term | Coefficient | Standard Error | t-Statistic | p-Value | R2-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (b0) | 53.4579 | 3.8542 | 13.8702 | 0.000000004 | |

| X (Scope b1) | 1.9670 | 0.6418 | 3.0650 | 0.00903 | 0.42 |

References

- Monthly Energy Review, Energy Consumption by Sector, Tables 2.1a, and 2.1b. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=86&t=1 (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Huo, J.; Peng, C. Depletion of natural resources and environmental quality: Prospects of energy use, energy imports, and economic growth hindrances. Resour. Policy 2023, 86, 104049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.R.; Zia-Ul-Haq, H.M.; Ponce, P.; Janjua, L. Re-investigating the impact of non-renewable and renewable energy on environmental quality: A roadmap towards sustainable development. Resour. Policy 2023, 81, 103411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosoughkhosravi, S.; Dixon-Grasso, L.; Jafari, A. The impact of LEED certification on energy performance and occupant satisfaction: A case study of residential college buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 59, 105097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, K.; Hazer, M.; Pyke, C.; Trowbridge, M. Using LEED Green Rating Systems to Promote Population Health. Build. Environ. 2020, 172, 106550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ade, R.; Rehm, M. The unwritten history of green building rating tools: A personal view from some of the ‘founding fathers’. Build. Res. Inf. 2020, 48, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuerst, F. Building momentum: An analysis of investment trends in LEED and energy star-certified properties. J. Retail Leis. Prop. 2009, 8, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkar, S. Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design for LEED Version 4 (LEED-EB v4) Gold Certification Strategies for Existing Buildings in the United States: A Case Study. Buildings 2025, 15, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkar, S. Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design for Existing Buildings Version 4.1 (LEED-EB v4.1) Gold-Certified Office Space Projects in European and Mediterranean Countries: A Pairwise Comparative Analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yezioro, A.; Capeluto, I.G. Energy Rating of Buildings to Promote Energy-Conscious Design in Israel. Buildings 2021, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LEED-EB v4.1. Operation and Maintenance. 2018. Available online: https://dcqpo543i2ro6.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/file_downloads/LEED%20v4.1%20O%2BM%20Guide.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Wu, P.; Song, Y.; Shou, W.; Chi, H.; Chong, H.Y.; Sutrisna, M. A comprehensive analysis of the credits obtained by LEED 2009 certified green buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LEED. 2009. Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/projects?Rating+Version=%5B%22v2009%22%5D (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Chen, S.; Gou, Z. Spatiotemporal distribution of green-certified buildings and the influencing factors: A study of U.S. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkar, S. Evaluating LEED commercial interior (LEED-CI) projects under the LEED transition from v3 to v4: The differences between China and the US. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkar, S. Life-Cycle Assessment in the LEED-CI v4 Categories of Location and Transportation (LT) and Energy and Atmosphere (EA) in California: A Case Study of Two Strategies for LEED Projects. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, M.; Berghorn, G. Research of key LEED-ND criteria for effective sustainability assessment. J. Green Build. 2024, 19, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkar, S. LEED-EB v4-certified projects and the built environment in the U.S.A. J. Green Build, 2026; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Cidell, J.; Beata, A. Spatial variation among green building certification categories: Does place matter? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009, 91, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Mao, C.; Wang, J.; Song, Y.Z.; Wang, X.Y. A decade review of the credits obtained by LEED v2.2 certified green building projects. Build. Environ. 2016, 102, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkar, S.; Verbitsky, O. LEED-NC 2009 Silver to Gold certified projects in the US in 2012–2017: An appropriate statistical analysis. J. Green Build. 2019, 14, 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Shoaib, M.; Abdul Kadar, R. LEED v4 Adoption Patterns and Regional Variations Across US-Based Projects. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, L.; Ruwanpura, J.Y. A review of the LEED points obtained in Canadian building projects to lower costs and optimize benefits. J. Archit. Eng. 2009, 15, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Song, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhao, X.; He, Q. Regional Variations of Credits Obtained by LEED 2009 Certified Green Buildings—A Country Level Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, B.; Lu, W.S.; Ye, M.; Bao, Z.K.; Zhang, X.L. Construction waste minimization in green building: A comparative analysis of LEED-NC 2009 certified projects in the US and China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokde, P.; Valdes-Vasquez, R.; Mosier, R. The green status of fire stations in the United States: An analysis of LEED-NC v3. J. Green Build. 2019, 14, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, M.; Naseri, S.; Tafazzoli, M. Beyond the Green Label: How LEED Certification Levels Shape Guest Satisfaction in USA Hotels. Buildings 2025, 15, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, M.; Berghorn, G.H. Pathways to Project Effectiveness in Sustainable Communities: Insights from a Residential Satisfaction Evaluation Model. J. Archit. Eng. 2025, 31, 04025014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Designing for the future: How LEED and SDGs drive sustainable art museum architecture. Open House Int. 2025, 50, 793–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkar, S. LEED-CI v4 Projects in Terms of Life Cycle Assessment in Manhattan, New York City: A Case Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, A.; Ottelin, J.; Sorvari, J. Are LEED-Certified Buildings Energy-Efficient in Practice? Sustainability 2019, 11, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, M.; Shayesteh, A.; Attallah, S. Assessing the Consistency Between the Expected and Actual Influence of LEED-NC Credit Categories on the Sustainability Score. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Associated Schools of Construction International Conference, Liverpool, UK, 3–5 April 2023; pp. 614–622. [Google Scholar]

- Goodarzi, M. Assessing LEED Credit Weighting: A Dual Perspective on Sustainable Construction and Educational Implications. In Proceedings of the 2024 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Portland, OR, USA, 23–26 June 2024; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Goodarzi, M.; Naseri, S.; Garshasby, M.; Tafazzoli, M. A Data-Driven Study of Regional Priority Credits and Their Impact on LEED Certification in Multifamily Residential Projects. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual ASC International Conference, Calgary, AB, Canada, 22 April 2025; Volume 6, pp. 371–380. [Google Scholar]

- Goodarzi, M.; Garshasby, M. Identifying the Leading Credit Categories in Determining the Overall LEED NC Score of Multifamily Residential Projects. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Associated Schools of Construction International Conference, Auburn, AL, USA, 3–5 April 2024; Volume 5, pp. 387–395. [Google Scholar]

- Parekh, R. Trends and challenges in LEED v4.1 certification: A comprehensive analysis of U.S. hospital scores in 2024. World J. Adv. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2024, 12, 726–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, D.D.; Franco, S.J. NCHS urban-rural classification scheme for counties. Vital Health Stat. 2012, 154, 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.M. Planning for urban sustainability: The geography of LEED®–Neighborhood Development™ (LEED®–ND™) projects in the United States. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2015, 7, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felgueiras, F.; Mourão, Z.; Moreira, A.; Gabriel, M.F. Multi-domain indoor environmental quality and worker health, well-being, and productivity: Objective and subjective assessments in modern office buildings. Build. Environ. 2025, 286, 113320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, R.; Ludbrook, J.; Spooren, W.P.J.M. Different outcomes of the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test from different statistics packages. Am. Stat. 2000, 54, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Pushkar, S. Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design Commercial Interior Version 4 (LEED-CI v4) Gold-Certified Office Space Projects: A Pairwise Comparative Analysis between Three Mediterranean Countries. Buildings 2024, 14, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Rudan, I.; Cousens, S. Setting health research priorities using the CHNRI method: VI. Quantitative properties of human collective opinion. J. Glob. Health 2016, 6, 010503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USGBC Projects Site. Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/projects (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- GBIG Green Building Data. Available online: http://www.gbig.org (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- MATLAB and Statistics Toolbox Release, 2024a; The Math Works, Inc.: Natick, MA, USA, 2024.

- Cliff, N. Dominance statistics: Ordinal analyses to answer ordinal questions. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 114, 494–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldina, I.; Beninger, P.G. Strengthening statistical usage in marine ecology: Linear regression. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2016, 474, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, W.S.; Devlin, S.J. Locally weighted regression: An approach to regression analysis by local fitting. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1988, 83, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, J.; Corragio, J.; Skowronek, J. Appropriate statistics for ordinal level data: Should we really be using t-test and Cohen’s d for evaluating group differences on the NSSE and other surveys? In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Florida Association of Institutional Research, Cocoa Beach, FL, USA, 1–3 February 2006; Florida Association for Institutional Research: Cocoa Beach, FL, USA, 2006; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volker, M.A. Reporting effect size estimates in school psychology research. Psychol. Sch. 2006, 43, 653–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J.A. How to select, calculate, and interpret effect sizes. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2009, 34, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.H. Handbook of Biological Statistics, 2nd ed.; Sparky House Publishing: Baltimore, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.D. Straightforward Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences; Brooks/Cole Publishing: Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guan, Y.; Li, X. Correlation and Simple Linear Regression. In Textbook of Medical Statistics; Guo, X., Xue, F., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- San Francisco Health Code, Article 38 (Enhanced Ventilation for Urban Infill). Available online: https://codelibrary.amlegal.com/codes/san_francisco/latest/sf_health/0-0-0-6054 (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Silveira, S.S.; Alves, T.D.C.L. Target Value Design Inspired Practices to Deliver Sustainable Buildings. Buildings 2018, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, S.; Zhao, T. LEED Certification in Residential Buildings: Assessing Economic Implications and Occupant Experiences. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual ASC International Conference, Calgary, AB, Canada, 22 April 2025; Volume 6, pp. 360–370. [Google Scholar]

- Awolesi, O.; Ghafari, F.; Reams, M. Indoor Environmental Quality Assessment in the Built Environment: A Critical Synthesis of Methodologies and Energy Integration Practices. Energy Built Environ. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Pushkar, S. Impact of “Optimize Energy Performance” Credit Achievement on the Compensation Strategy of Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design for Existing Buildings Gold-Certified Office Space Projects in Madrid and Barcelona, Spain. Buildings 2023, 13, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventola, V.; Brenman, E.; Chan, G.; Ahmed, T.; Castaldi, M.J. Quantitative analysis of residential plastic recycling in New York City. Waste Manag. Res. 2021, 39, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodarzi, M.; Goodarzi, A.N.; Naseri, S.; Parsaee, M.; Abazari, T. Assessing Climate Sensitivity of LEED Credit Performance in U.S. Hotel Buildings: A Hierarchical Regression and Machine Learning Verification Approach. Buildings 2025, 15, 4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuziemko, J. LEED Buildings Outperform Market Peers According to Research. 2025. Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/articles/leed-buildings-outperform-market-peers-according-research (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Goodarzi, M.; Shayesteh, A.; Garshasby, M.; Son, J.J. Mapping sustainable synergies: A network analysis of LEED-NC v3 credits in multifamily residential projects. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- California Air Resources Board (CARB). AB 32: Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006. Available online: https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/resources/fact-sheets/ab-32-global-warming-solutions-act-2006/printable/print (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- CARB. California Transportation Carbon Reduction Strategy. 2023. Available online: https://dot.ca.gov/-/media/dot-media/programs/esta/documents/carbon-reduction/final-carbon-reduction-strategy-a11y.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- California Building Standards Commission. 2022 California Green Building Standards Code (CALGreen); California Building Standards Commission: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2021. Available online: https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/building-decarbonization/building-standards-code#:~:text=While%20the%20scope%20of%20the,in%20residential%20and%20nonresidential%20buildings (accessed on 20 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.