Performance of Drilling–Mixing–Jetting Deep Cement Mixing Pile Groups in the Yellow River Floodplain Area

Abstract

1. Introduction

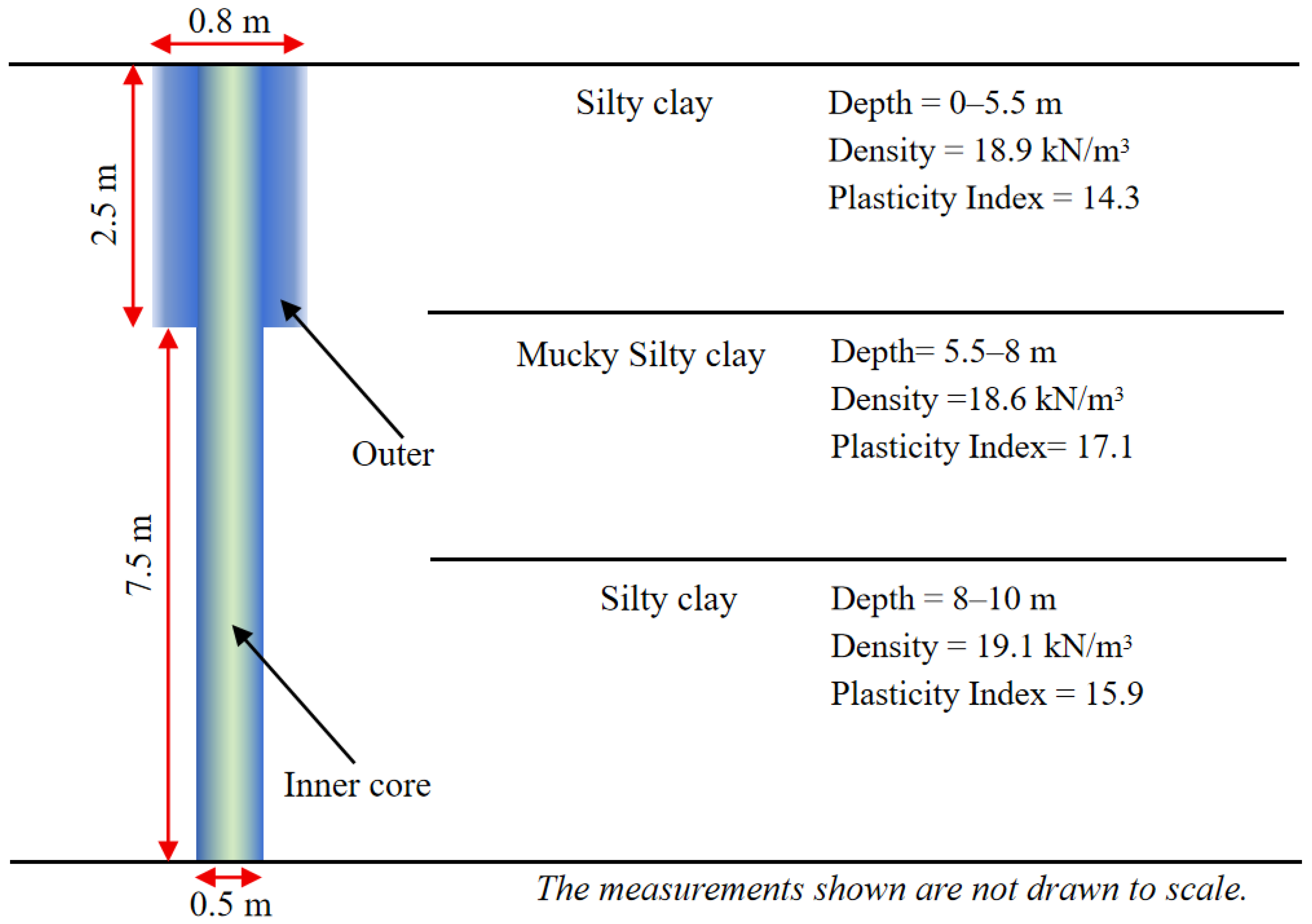

2. Problem Statement and Challenges in Field Installation of DCM Columns in the Yellow River Floodplain

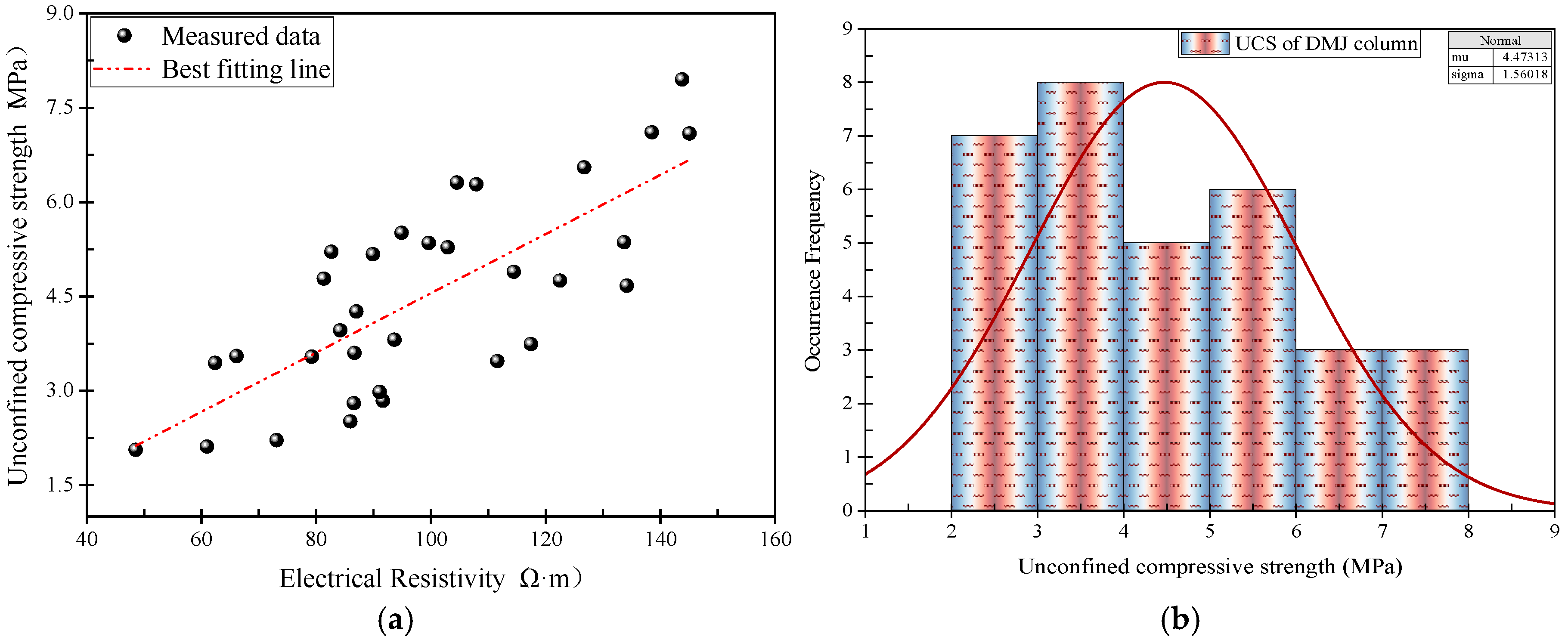

3. Field Testing

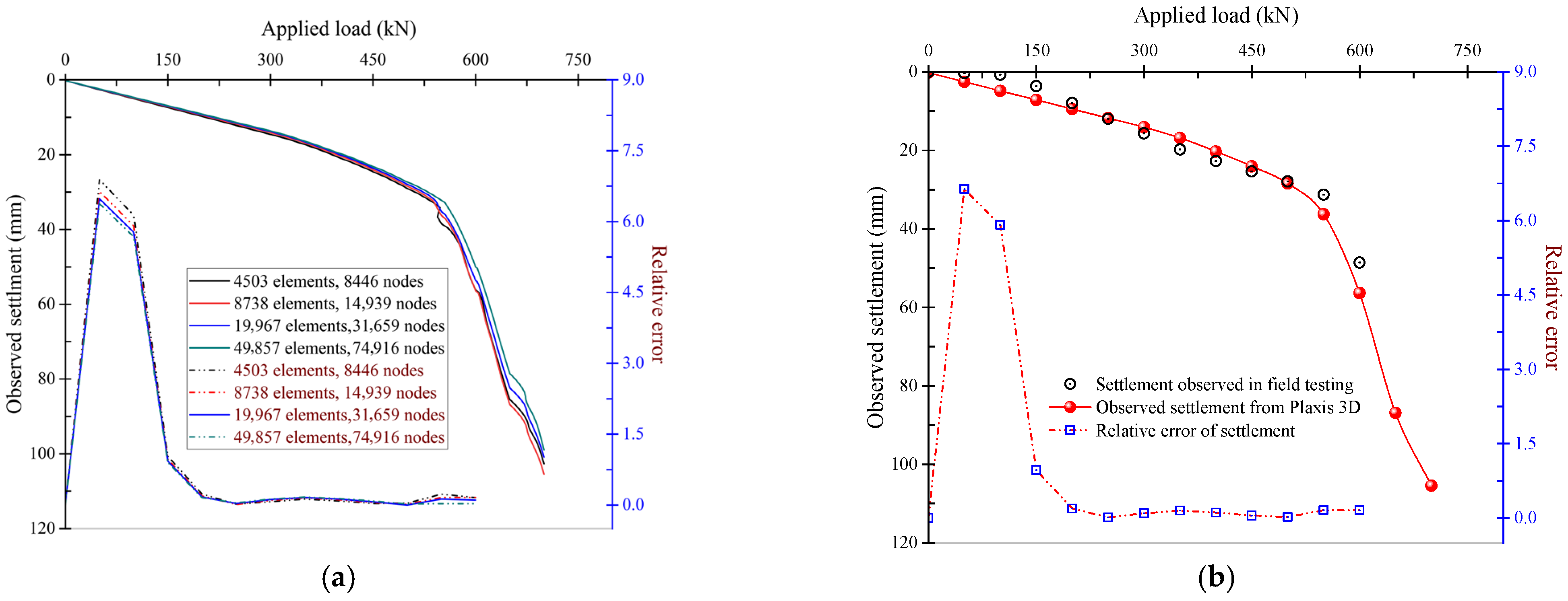

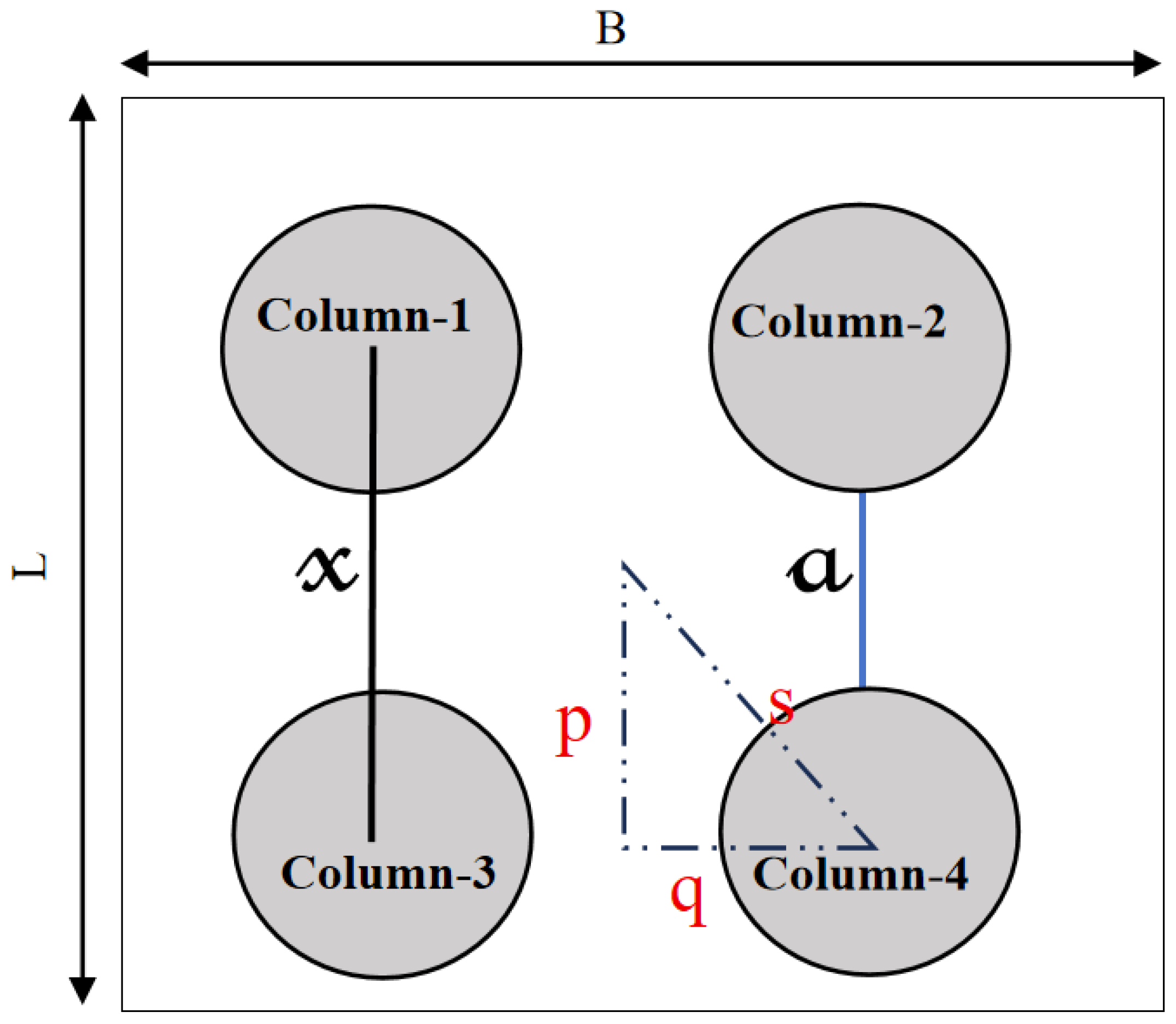

4. Model Development and Validation

5. Results and Discussions

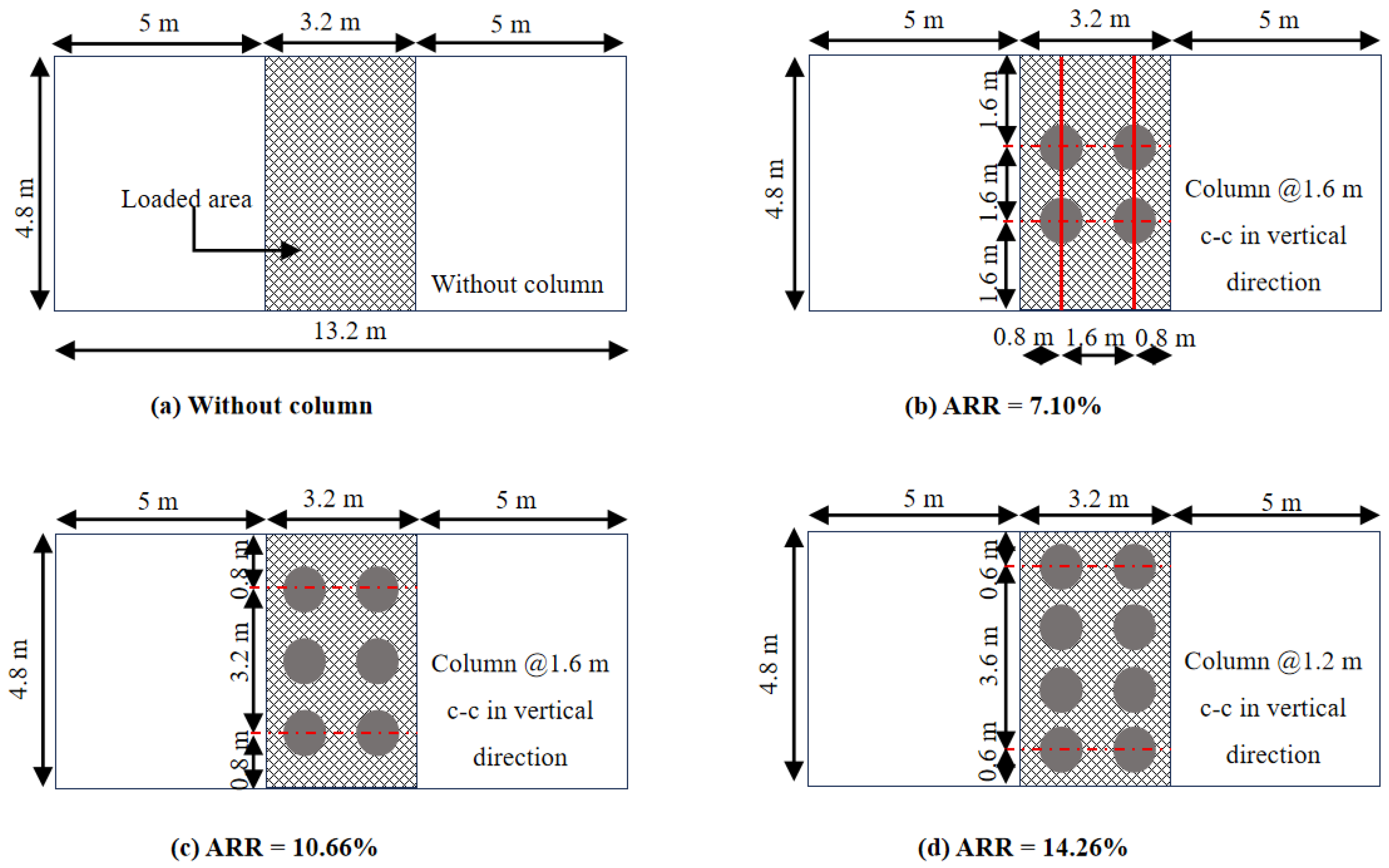

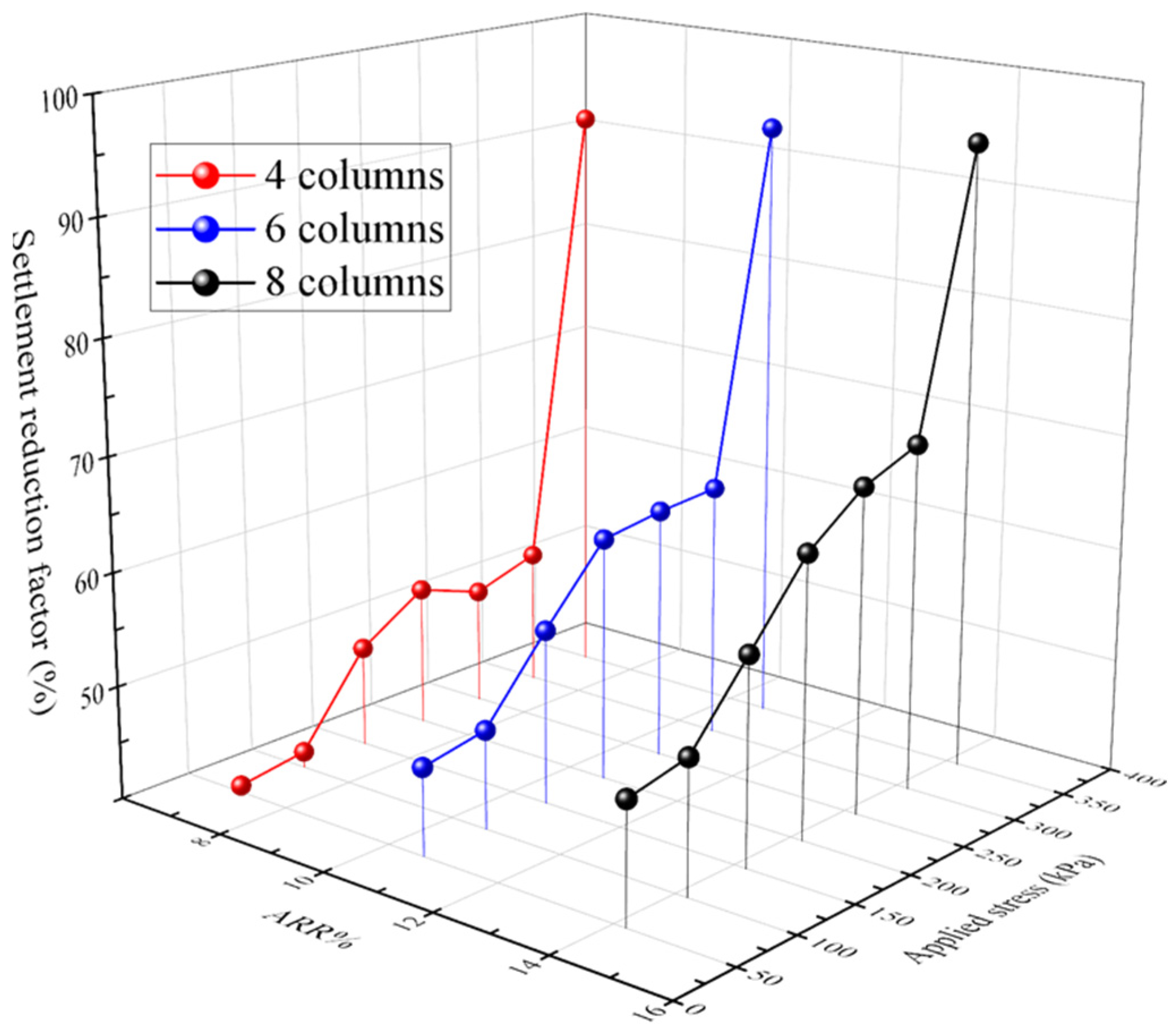

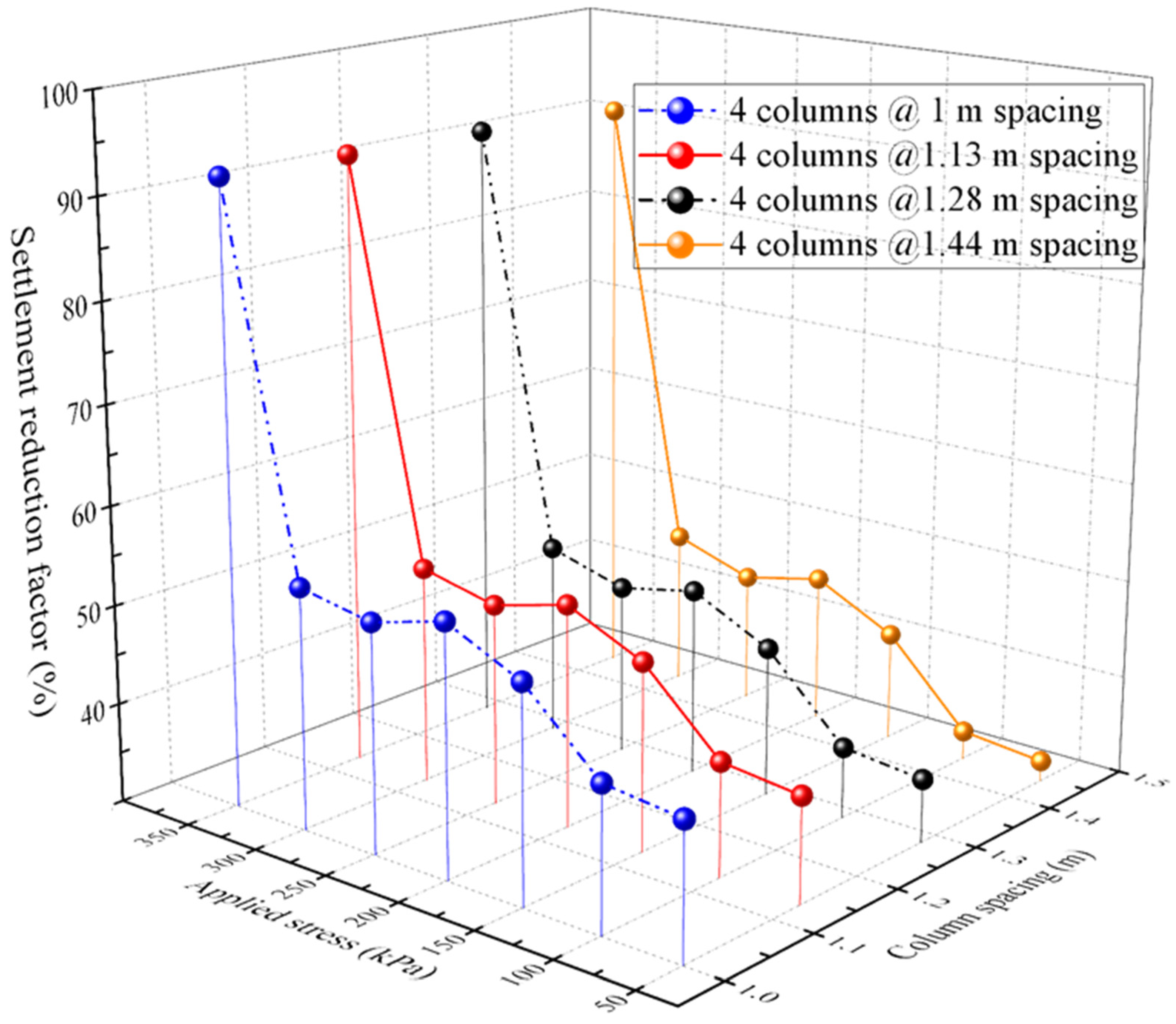

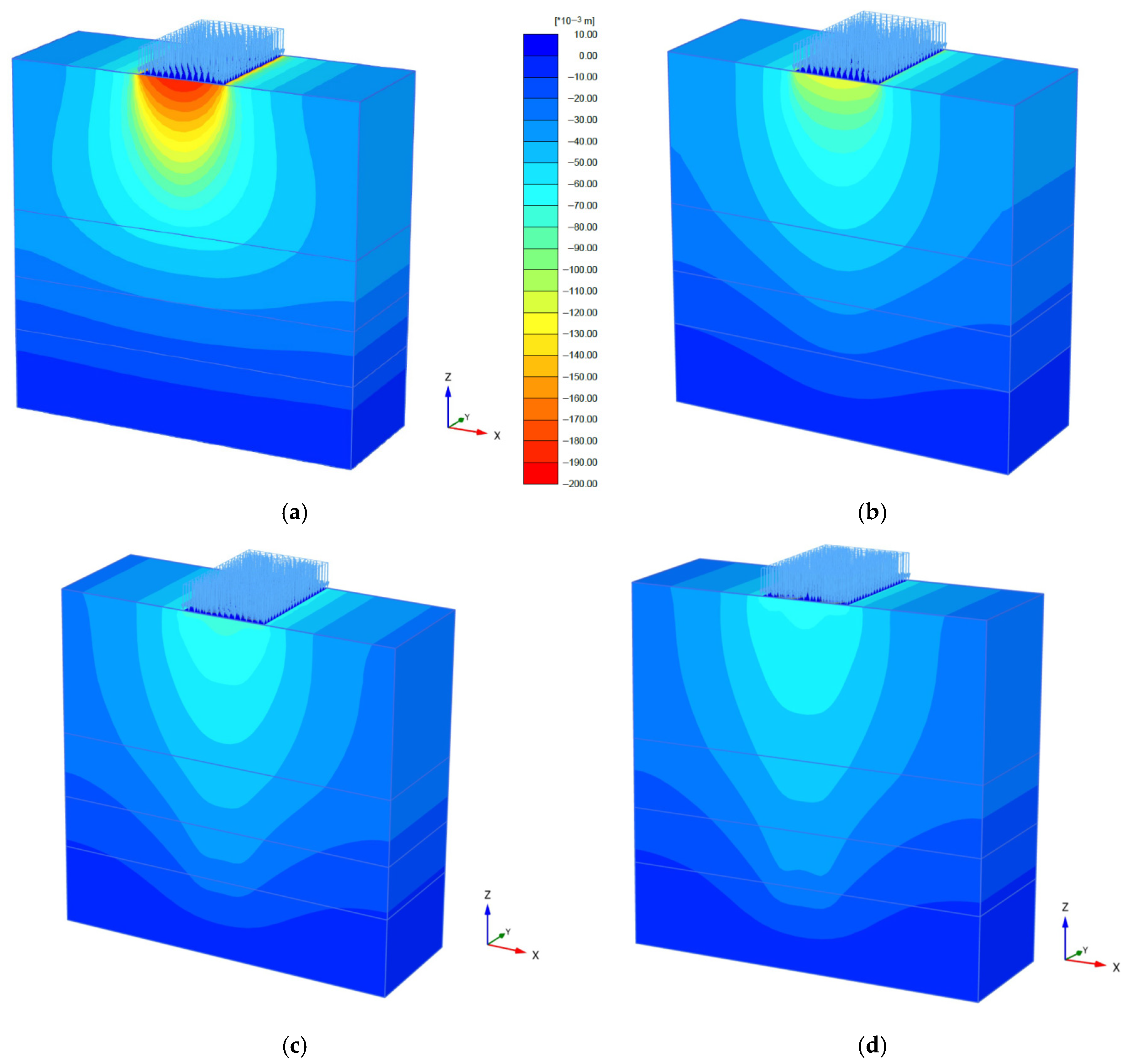

5.1. Influence on Settlement Reduction Ratio

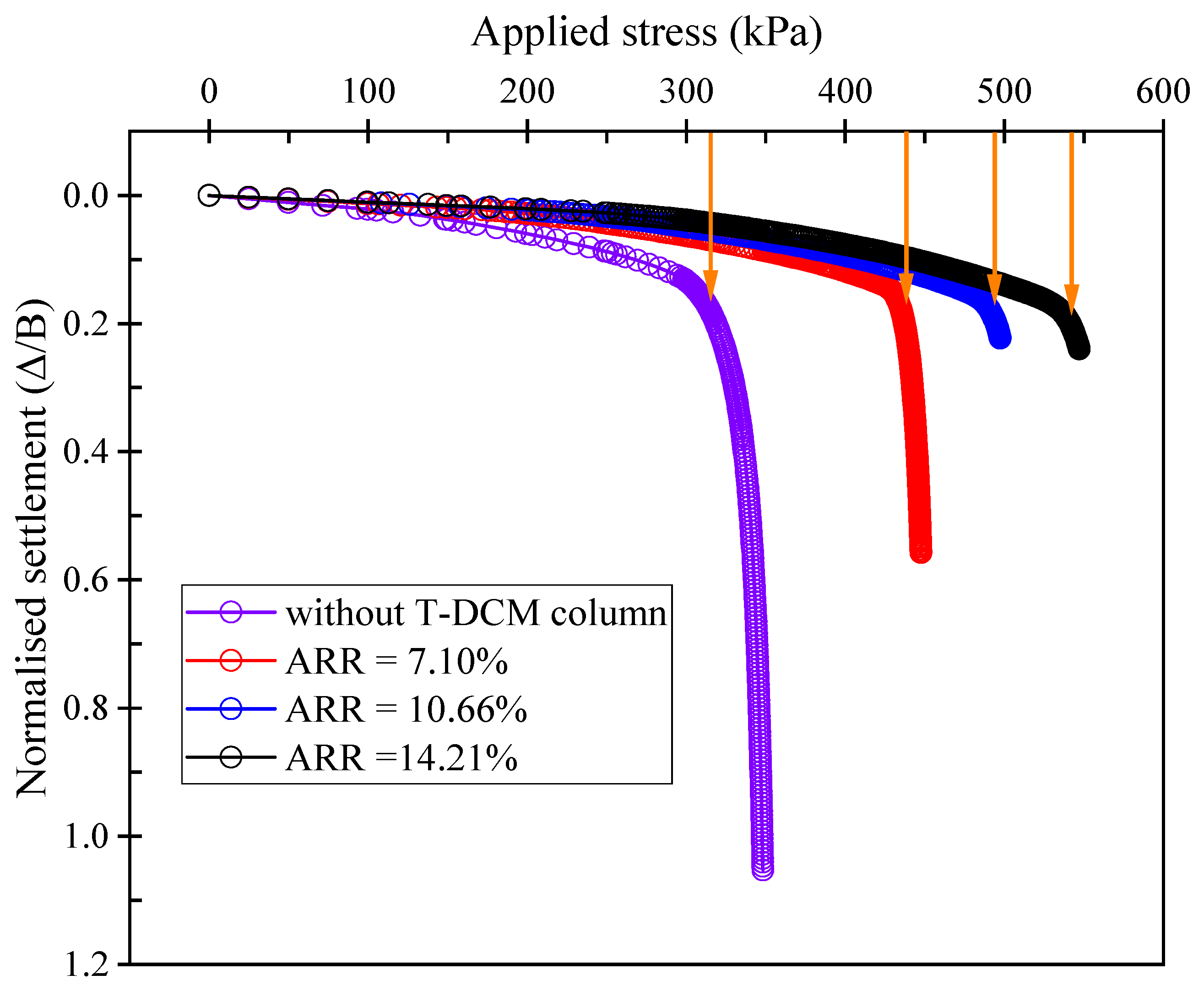

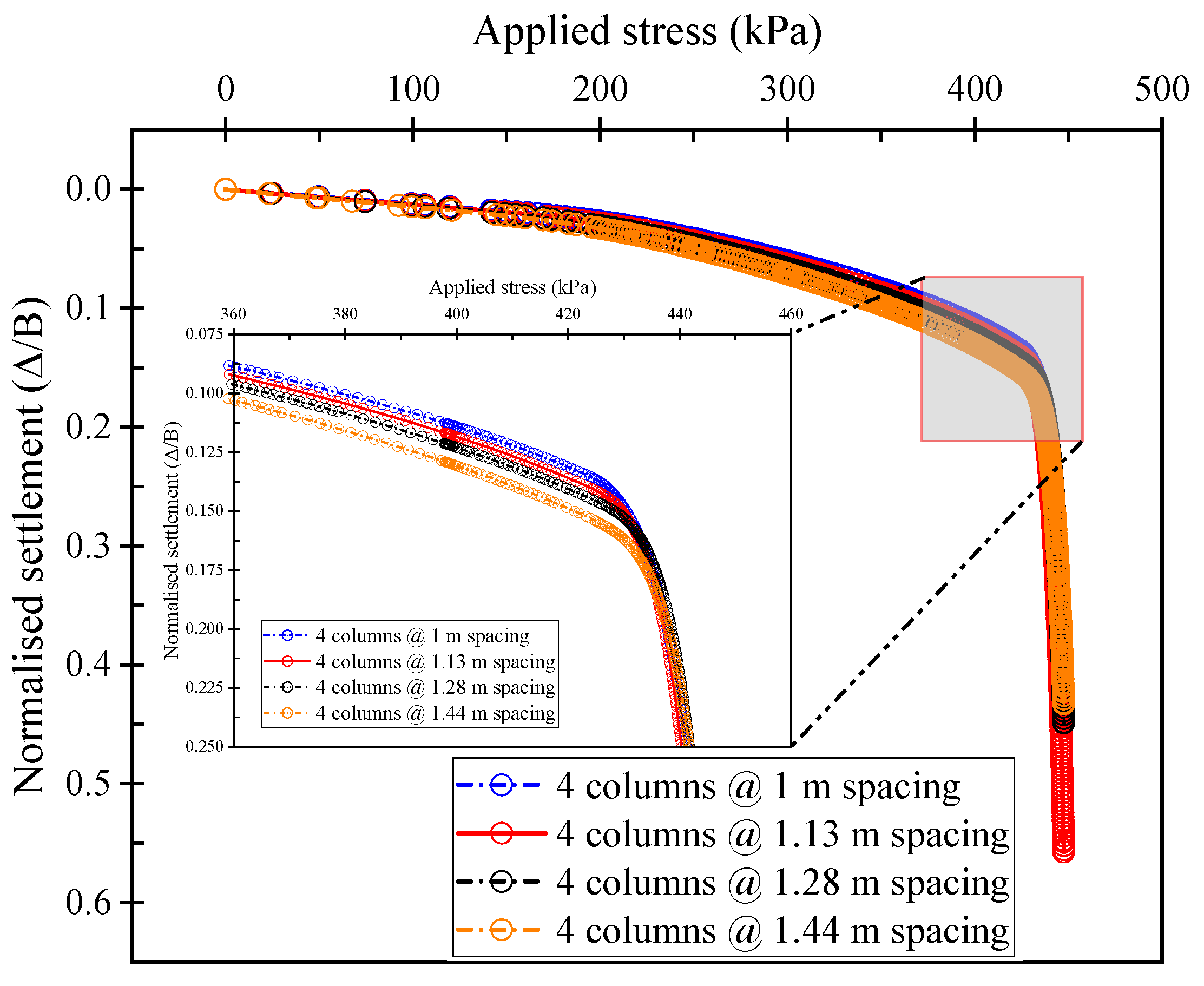

5.2. Load Bearing Capacity

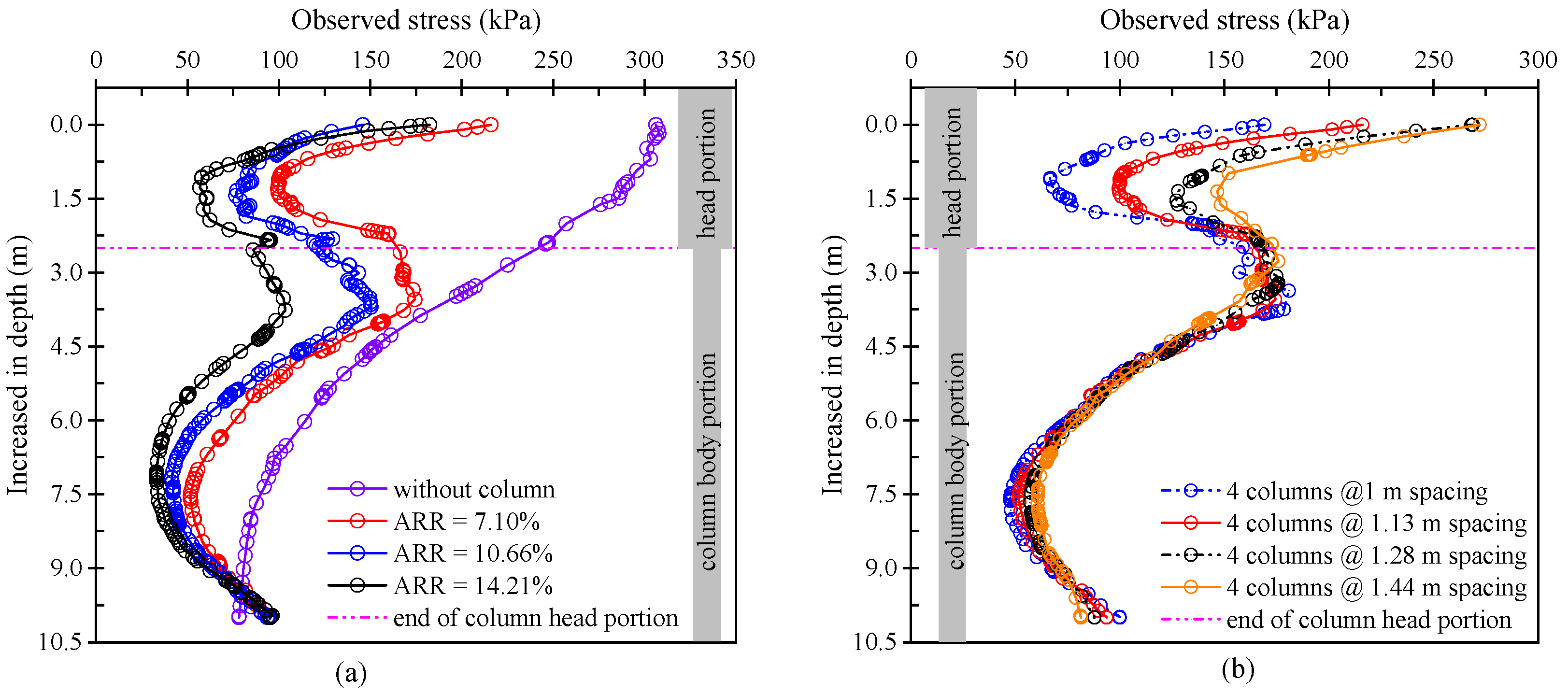

5.3. Stress Variation Along the Depth

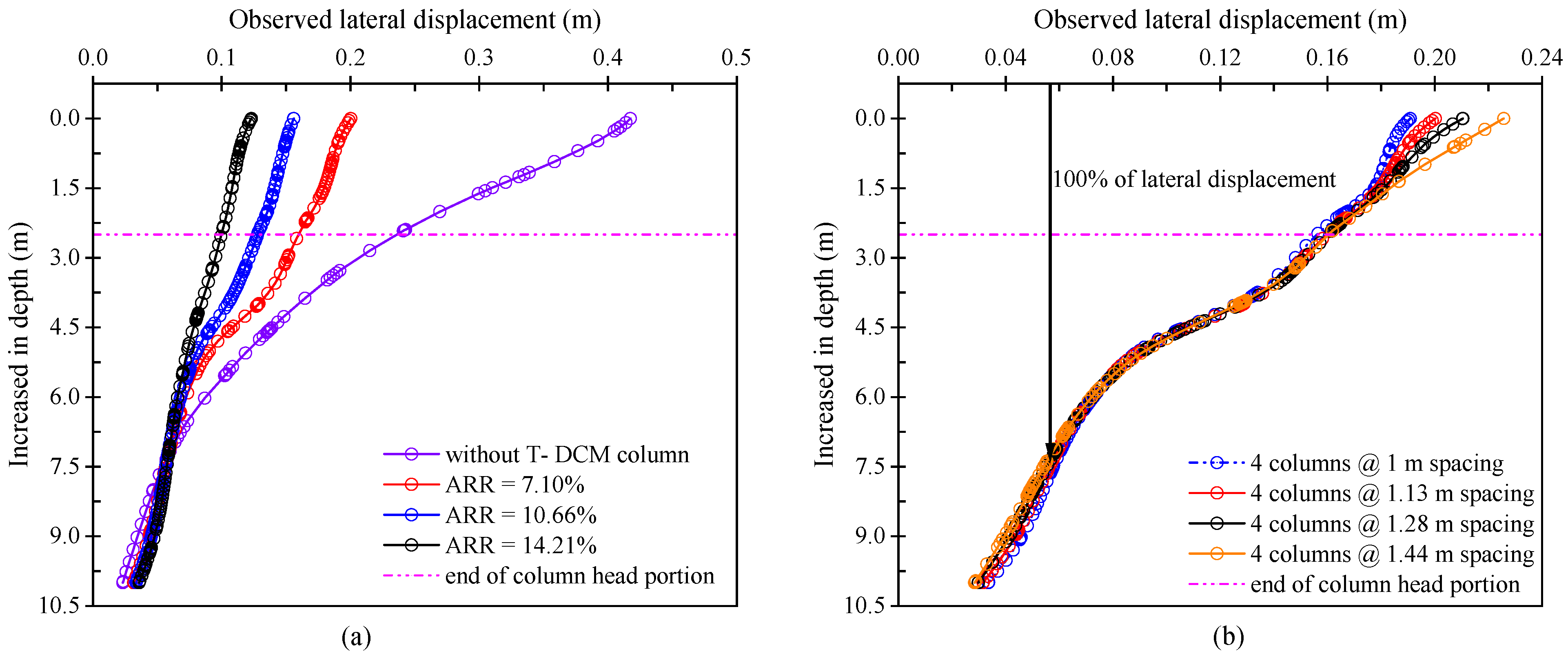

5.4. Lateral Displacement

6. Conclusions

- Settlement reduction ratio increases with the increase in the value of area replacement ratio (ARR) and externally applied stress; however, the increase in the column spacing leads to a considerable reduction. A minimum SRF of 32.11% was recorded for four columns with larger spacing, while a maximum SRF of 94.75% occurred with eight columns.

- The bearing capacity improvement factor was found to increase with the increase of the area replacement ratio (ARR). However, the influence of the column spacing on the bearing capacity improvement factor is found to have a minimal influence and ranges between 423.89 kPa and 431.61 kPa.

- The unreinforced composite soil exhibited a 70.51% higher maximum lateral displacement, which was reduced with column installation and increasing area replacement ratio (ARR). Further, maximum lateral displacement occurred in the upper soil layer and decreased with depth due to increasing confining pressure and restraint from underlying unimproved soil layers.

- Electrical resistivity of soil–cement for a given curing time and water–cement ratio showed strong correlation (linear correlation with Pearson’s R value more than 75%) with unconfined compressive strength and SPT blow count, indicating its potential for practical quality control of soil–cement.

- The DMJ-integrated columns demonstrate enhanced soil–cement strength in the Yellow River Floodplain region, with sample strengths varying between 2 and 8 MPa and an average strength of 4–5 MPa.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wonglert, A.; Jongpradist, P.; Jamsawang, P.; Larsson, S. Bearing capacity and failure behaviors of floating stiffened deep cement mixing columns under axial load. Soils Found. 2018, 58, 446–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellato, D.; Spagnoli, G.; Wiedenmann, U. Engineering and environmental aspects of offshore soil mixing. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Geotech. Eng. 2015, 168, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broms, B. Keynote lecture: Design of lime, lime/cement and cement columns. In Dry Mix Methods for Deep Soil Stabilization; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, D.A.; Geosystems, E.C.O. An Introduction to the Deep Soil Mixing Methods as Used in Geotechnical Applications; United States Federal Highway Administration Office of Infrastructure: Washington, DC, USA, 2000.

- Liu, S.Y.; Du, Y.J.; Yi, Y.L.; Puppala, A.J. Field Investigations on Performance of T-Shaped Deep Mixed Soil Cement Column–Supported Embankments over Soft Ground. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2012, 138, 718–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, S.; Singh, M.J.; Borana, L. Time-dependent settlement behaviour of clayey soil treated with deep cement mixed column. In Smart Geotechnics for Smart Societies; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 752–757. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, S.; Singh, M.J.; Kamchoom, V.; Choi, C.E.; Borana, L. Experimental and numerical modelling of time-dependent behaviour in deep cement mixing column improved montmorillonitic clay. Ocean Eng. 2025, 332, 121451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.J.; Choudhary, S.; Borana, L. Numerical study on stress-strain characteristics of the deep cement mixing column improved soil. In Smart Geotechnics for Smart Societies; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 735–740. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Z.; Ouyang, H.; Dai, G.; Chen, X. A theoretical analysis method for stiffened deep cement mixing (SDCM) pile groups under vertical load in layer soils. Comput. Geotech. 2025, 183, 107211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, K.; Bell, A. Ground Improvement; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sakr, M.A.; Elsawwaf, M.A.; Rabah, A.K. Numerical Study of Soft Clay Reinforced with Deep Cement Mixing Technique. Indian Geotech. J. 2022, 52, 1487–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, S. Consolidation Calculation of Soft Ground Improved by T-Shape Deep Mixing Columns. In GeoCongress 2008; Proceedings; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Chen, Y.; Chen, W.; Wang, J.; Ren, C. The performance of T-shaped deep mixed soil cement column-supported embankments on soft ground. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 369, 130578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.; Singh, M.J.; Rong, Y.; Yao, Z. Optimized T-shaped soil-cement deep mixing column for sustainable ground improvement. Front. Built Environ. 2025, 11, 1628946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamsawang, P.; Voottipruex, P.; Jongpradist, P.; Likitlersuang, S. Field and three-dimensional finite element investigations of the failure cause and rehabilitation of a composite soil-cement retaining wall. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 127, 105532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Phan, T.N.; Likitlersuang, S. Evaluating the Applicability of Large-Diameter Cement Deep Mixing Method for Soft Ground Improvement: A Landmark Case Study in Vietnam. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2025, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Du, G.; Song, T.; Qiao, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhong, S.; Gao, C.; Zhai, S. Bearing characteristics of long enlarged head ultra-deep T-shaped bidirectional dry jet mixing column (TDM) improved ground. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2025, 29, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.-L.T.; Tran, M.H.; Tran, T.D.; Nguyen, B.-P. Numerical Analysis of Arching Behavior of Geosynthetic-Reinforced and DCM Column-Supported Embankment with Geosynthetic Characteristics. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2023, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Mishra, A. Influence of Load Transfer Platforms on the Performance of Embankments on Soft Soils Reinforced with Stone and DCM Columns. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2025, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulambarkar, S.; Manna, B.; Shahu, J.T. Effect of deep mixed column pattern on the performance of basal reinforced embankment resting on soft soil. Soils Found. 2025, 65, 101578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliaei, M.; Heidarzadeh, H.; Mansouri, S. 3D Numerical Analyses for Optimization of Deep-Mixing Columns Combined by Raft Foundations. Indian Geotech. J. 2021, 51, 1338–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.J.; Gong, Q.; Yao, K.; Ma, C.; Jiang, H.; Yao, Z. Time-dependent performance of T-shaped deep cement-mixed columns under embankment loading with varying strength conditions. Structures 2025, 82, 110525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.; Yao, Z.; Song, X.; Zhang, X.; Hu, J.; Pan, X. Settlement evaluation of soft ground reinforced by deep mixed columns. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2016, 9, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, P.; Modoni, G. Design of jet-grouting cut-offs. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Improv. 2007, 11, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lignola, G.P.; Flora, A.; Manfredi, G. Simple method for the design of jet grouted umbrellas in tunneling. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2008, 134, 1778–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.C.H.; Kek, H.Y.; Hu, X.; Wong, L.N.; Teo, S.; Ku, T.; Lee, F.-H. An approach for characterising electrical conductivity of cement-admixed clays. Soils Found. 2022, 62, 101127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Kim, D.-J.; Lee, J.-S.; Tutumluer, E.; Byun, Y.-H. Evaluation of electrical resistivity of cement-based materials using time domain reflectometry. Measurement 2024, 236, 115166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Han, J. Two-dimensional parametric study of geosynthetic-reinforced column-supported embankments by coupled hydraulic and mechanical modeling. Comput. Geotech. 2010, 37, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, P.; Yi, Y.; Liu, S. Bearing capacity optimization of T-shaped soil-cement column-improved soft ground under soft fill. Soils Found. 2021, 61, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, M.A.; Elsawwaf, M.A.; Rabah, A.K. Soft clay improved by deep cement mixing column technique. Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 15, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsamee, W.A. Effect of pile spacing on ultimate capacity and load shearing for piled raft foundation. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2018, 13, 5955–5967. [Google Scholar]

- Mali, S.; Singh, B. Assessing the effect of governing parameters of bearing capacity determination of small piled rafts on clay soil. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.C.; Miura, N.; Koga, H. Lateral Displacement of Ground Caused by Soil–Cement Column Installation. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2005, 131, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Depth | Material | Density (kN/m3) | Cohesion (kN/m2) | Frictional Angle (°) | Young’s Modulus (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5.5 m | Silty Clay | 18.9 | 22.80 | 14.6 | 7.00 |

| 5.5–8.0 m | Mucky Silty clay | 18.6 | 32.90 | 8.9 | 5.00 |

| 8.0–10.0 m | Silty Clay | 19.1 | 26.20 | 14.3 | 5.50 |

| 10.0–20.0 m | Silty Clay | 19.2 | 23.5 | 15.5 | 7.50 |

| Outer | DMJ pile | 20.0 | 350.0 | 20.0 | 240.0 |

| Inner core | DMJ pile | 20.0 | 410.0 | 25 | 350.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, P.; Lei, T.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Wei, H.; Yao, Z.; Yao, K. Performance of Drilling–Mixing–Jetting Deep Cement Mixing Pile Groups in the Yellow River Floodplain Area. Buildings 2026, 16, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010162

Li P, Lei T, Xu C, Zhang Y, Li L, Wei H, Yao Z, Yao K. Performance of Drilling–Mixing–Jetting Deep Cement Mixing Pile Groups in the Yellow River Floodplain Area. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):162. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010162

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Peng, Tao Lei, Chao Xu, Yuhe Zhang, Lin Li, Haoji Wei, Zhanyong Yao, and Kai Yao. 2026. "Performance of Drilling–Mixing–Jetting Deep Cement Mixing Pile Groups in the Yellow River Floodplain Area" Buildings 16, no. 1: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010162

APA StyleLi, P., Lei, T., Xu, C., Zhang, Y., Li, L., Wei, H., Yao, Z., & Yao, K. (2026). Performance of Drilling–Mixing–Jetting Deep Cement Mixing Pile Groups in the Yellow River Floodplain Area. Buildings, 16(1), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010162