Welding Residual Stress and Deformation of T-Joints in Large Steel Structural Modules

Abstract

1. Introduction

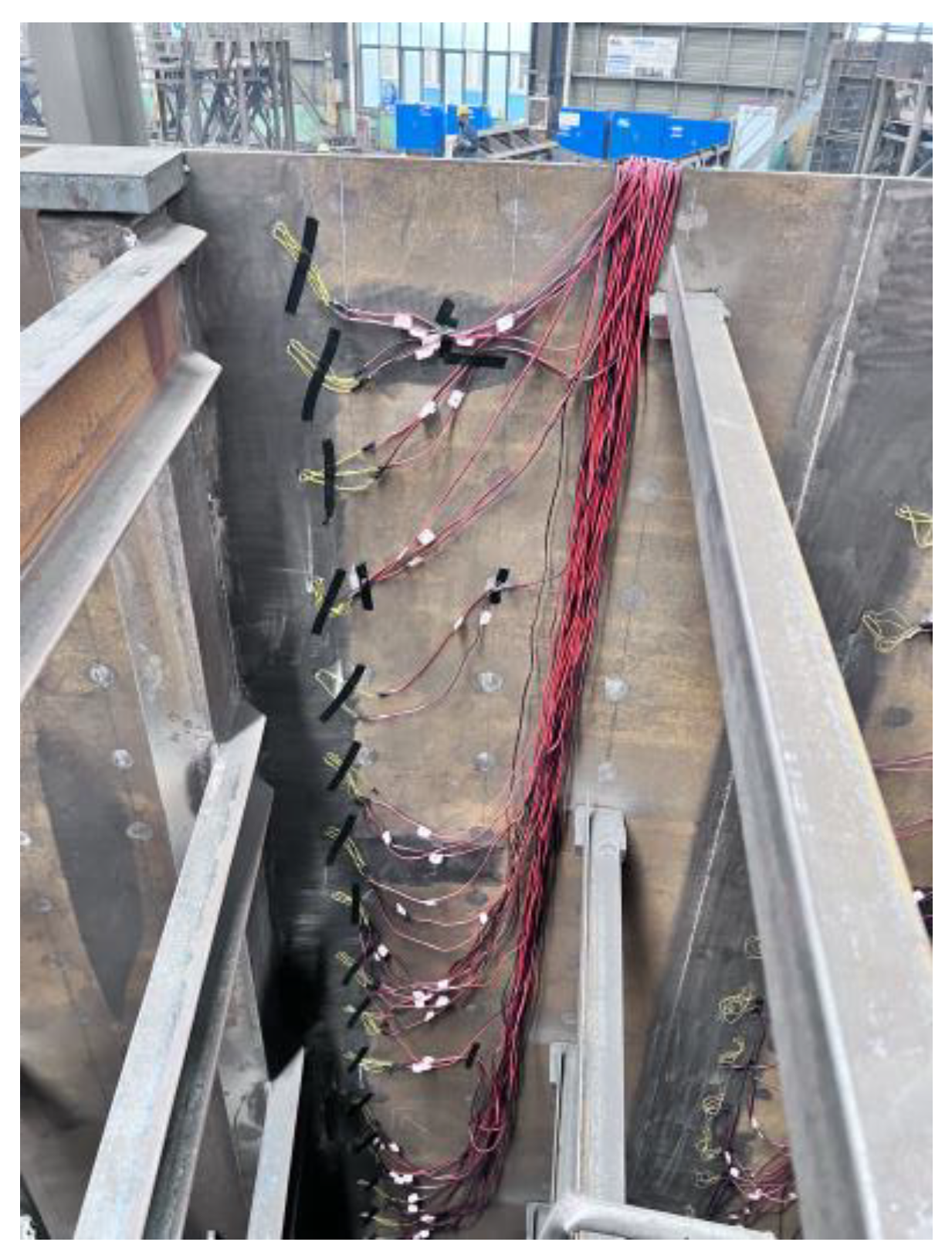

2. Hole-Drilling Test Process

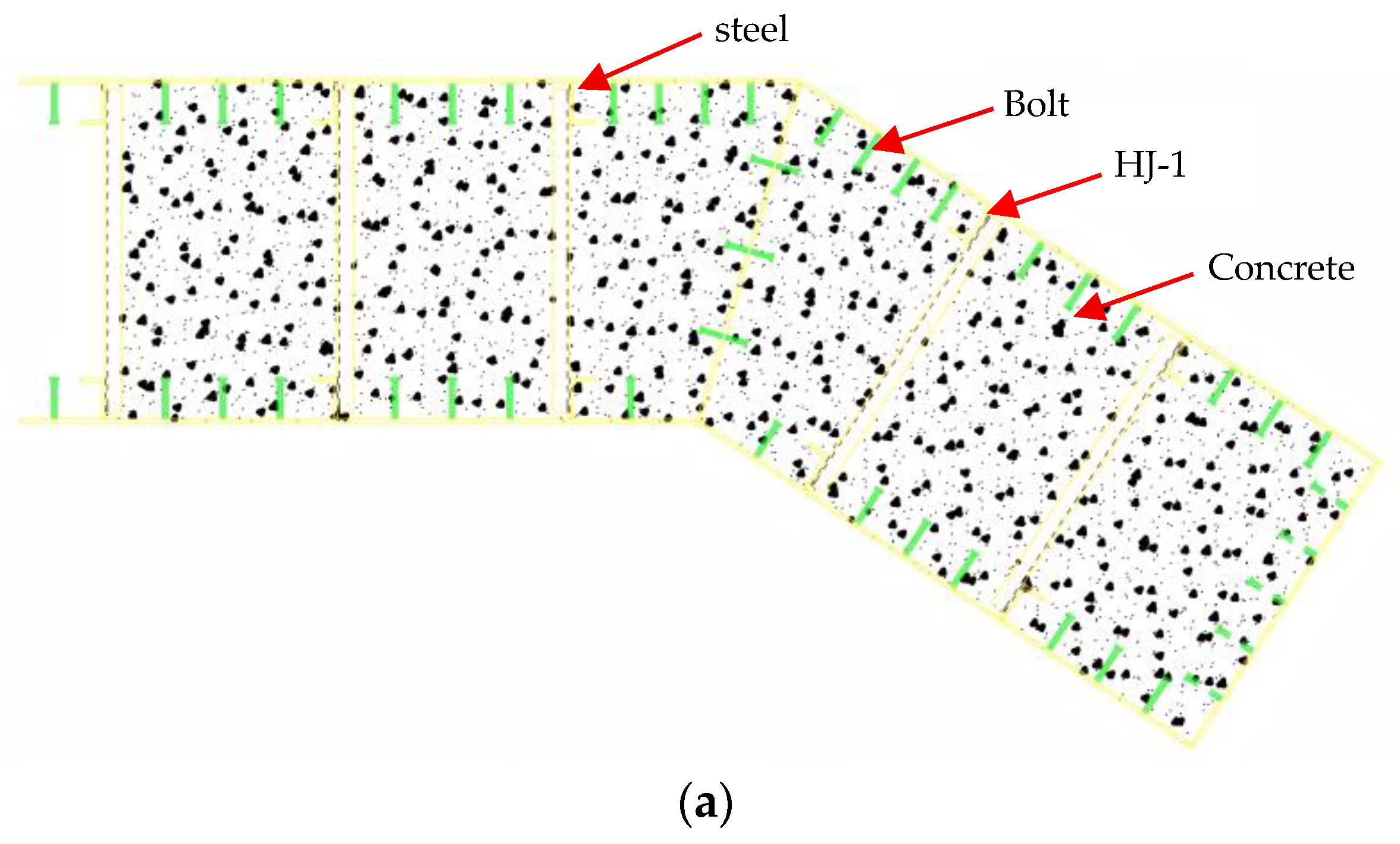

2.1. Selection of Specimens

2.2. Materials and Welding Parameters

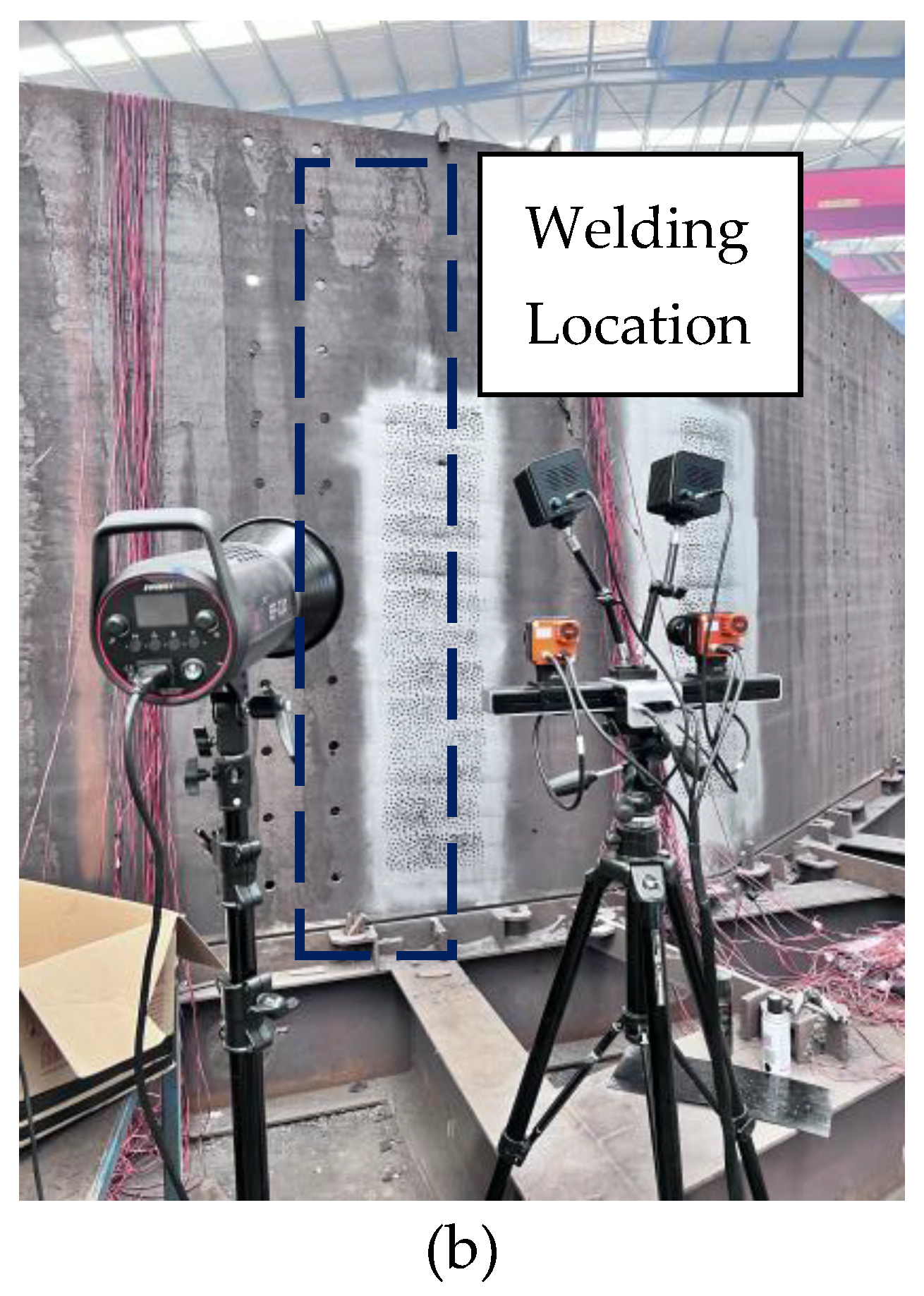

2.3. Measurement Process

3. Numerical Simulation

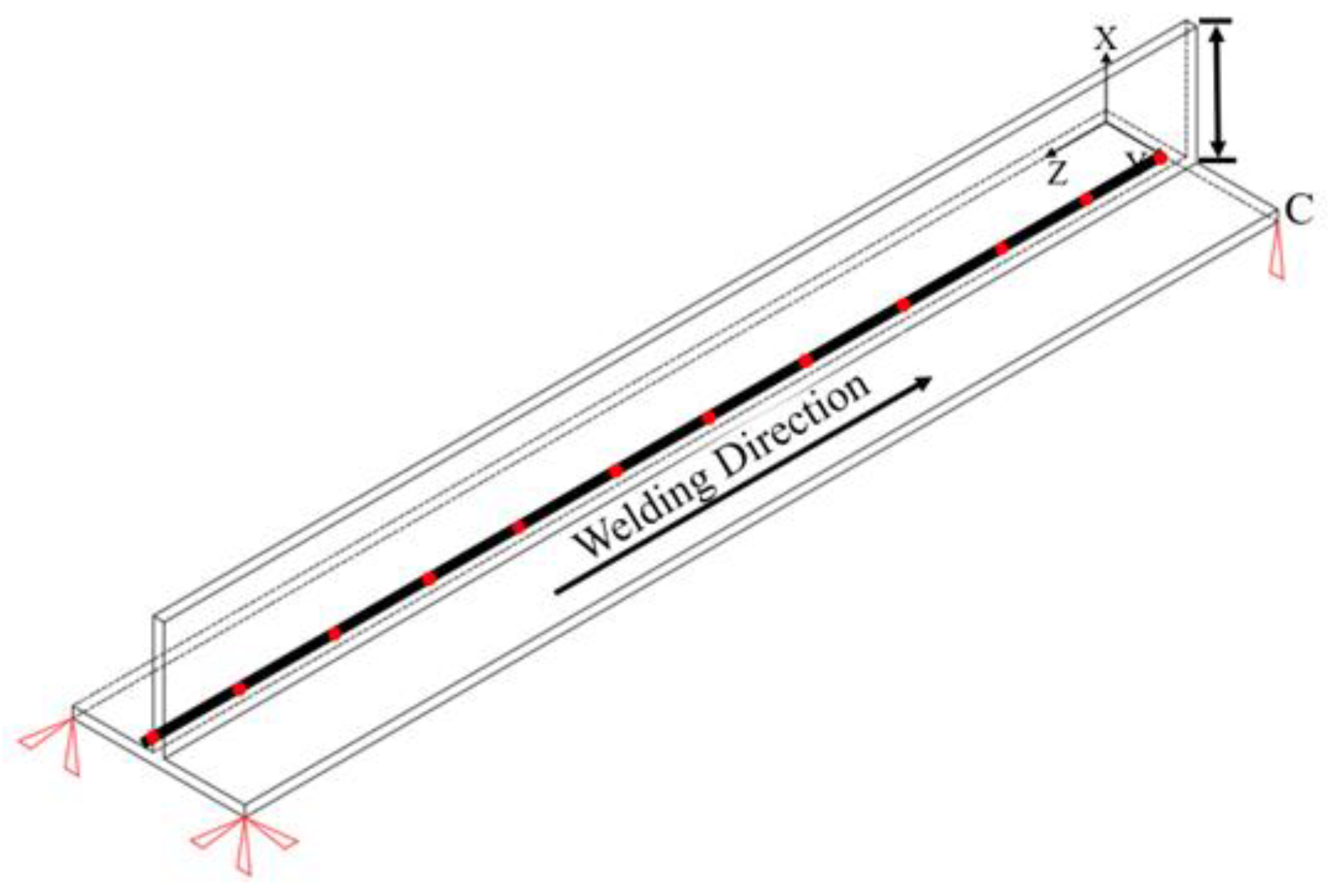

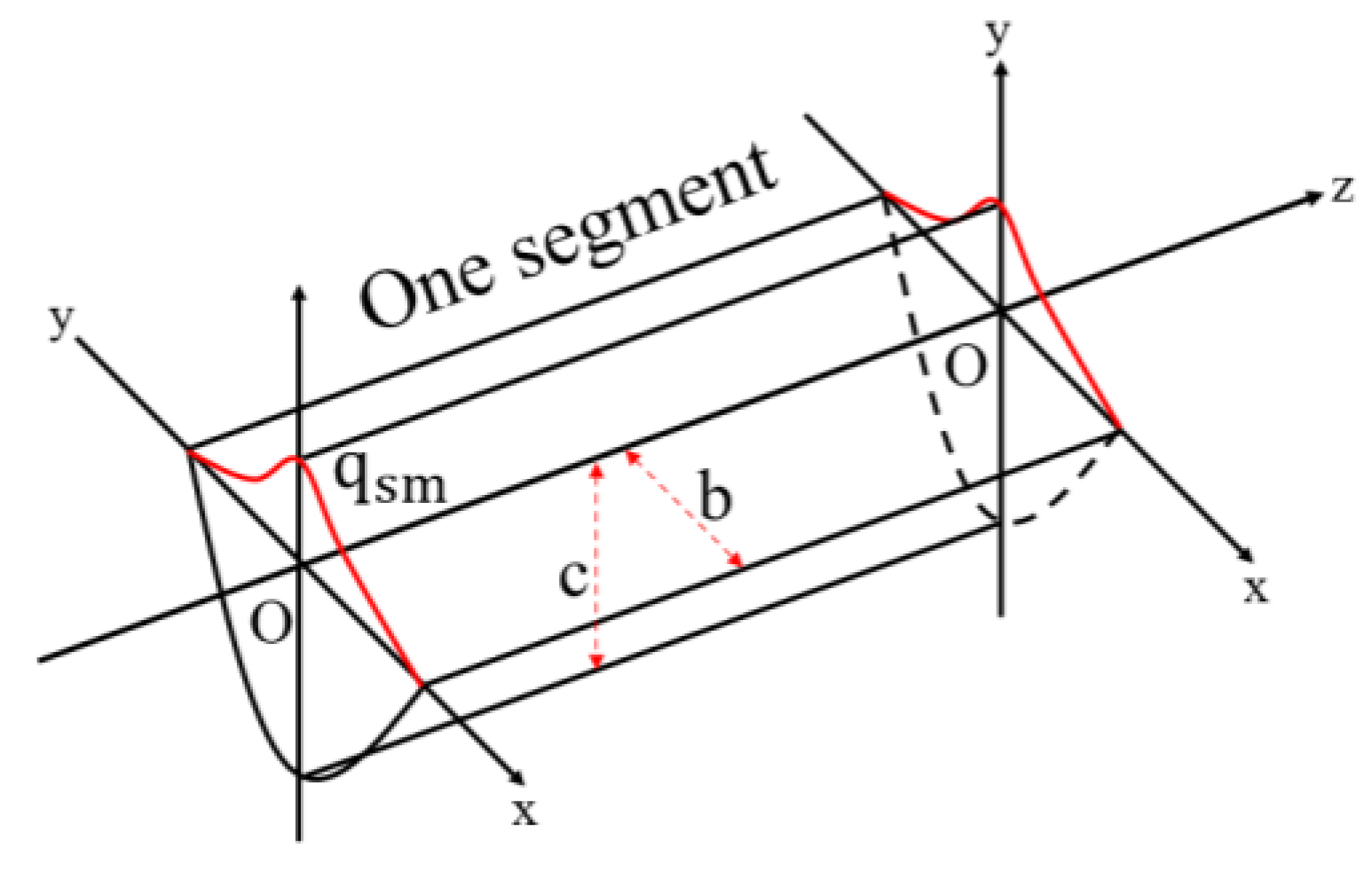

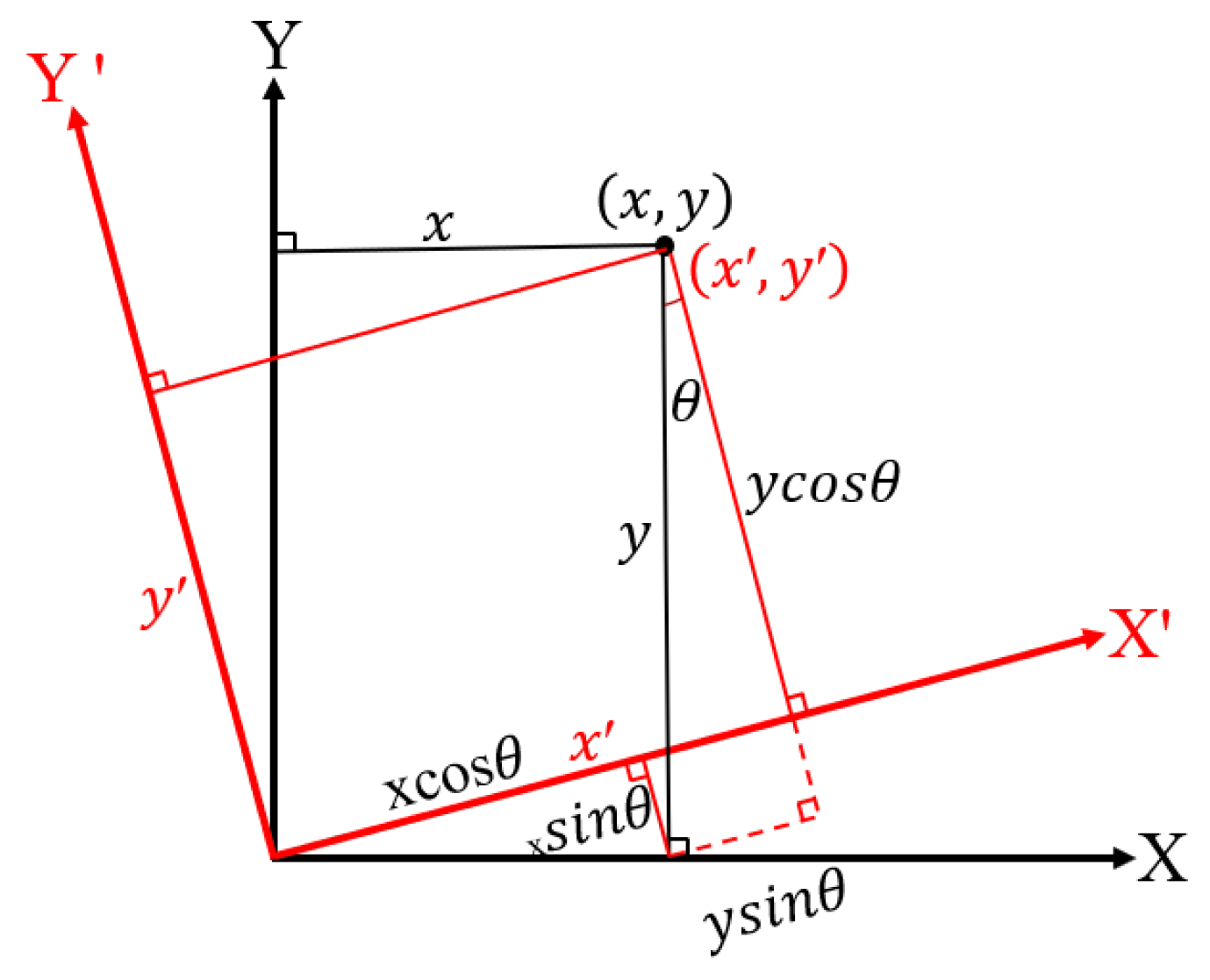

3.1. Segmented Moving Heat Sources

3.2. Finite Element Model

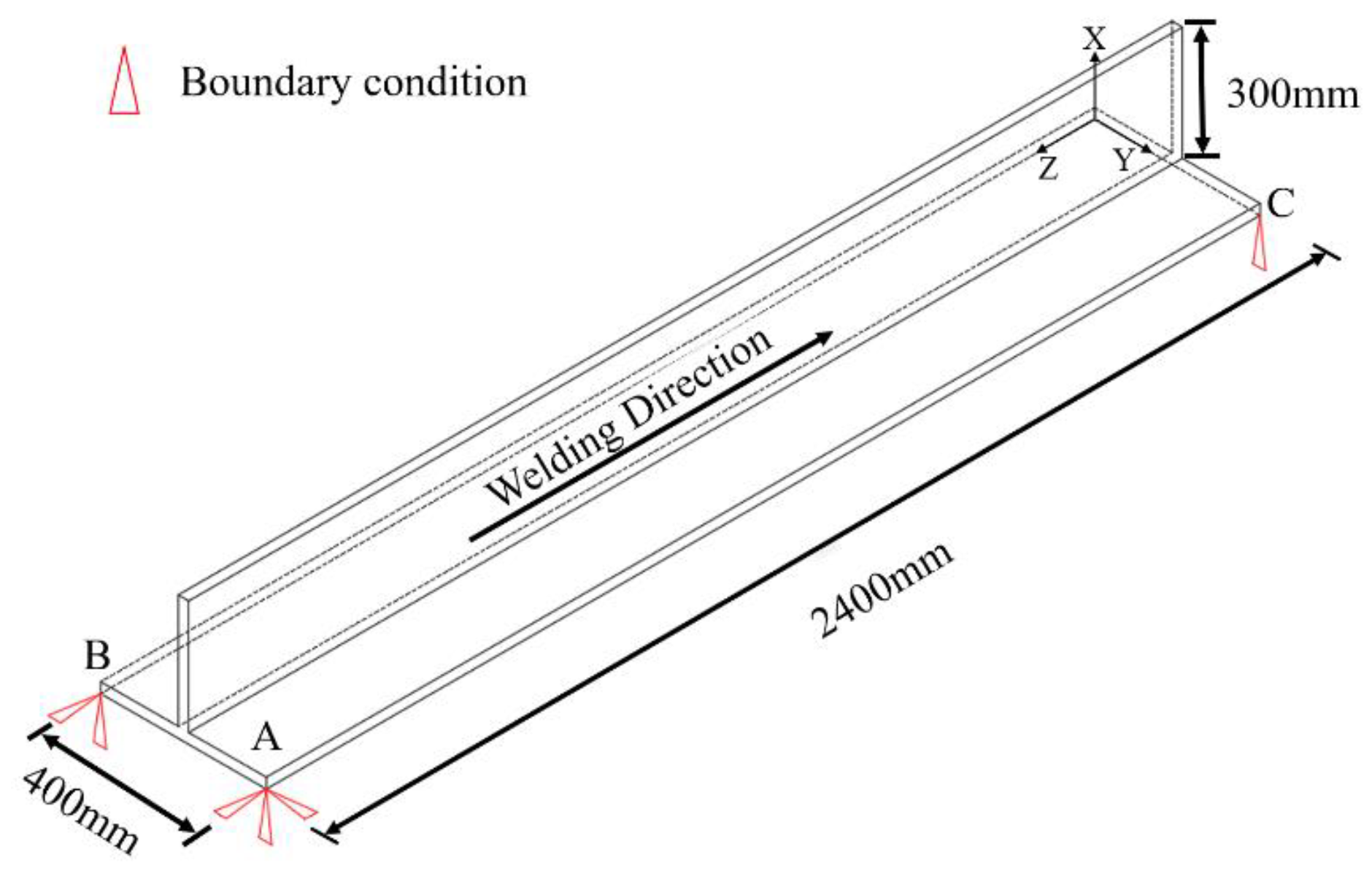

3.2.1. Model Construction

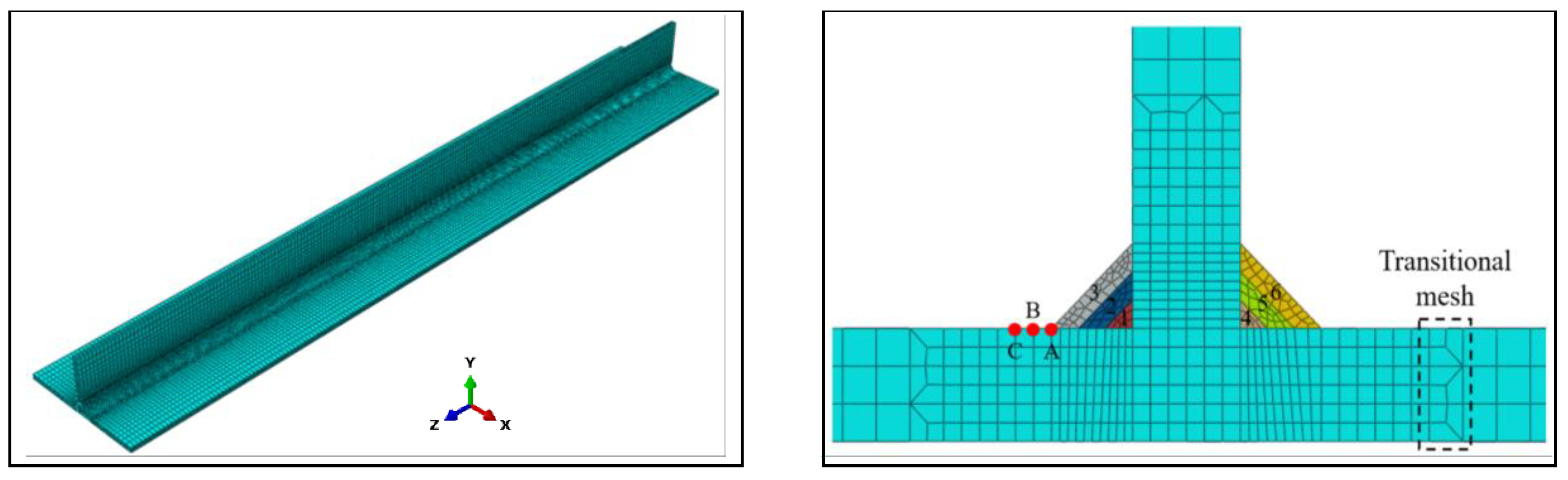

3.2.2. Meshing

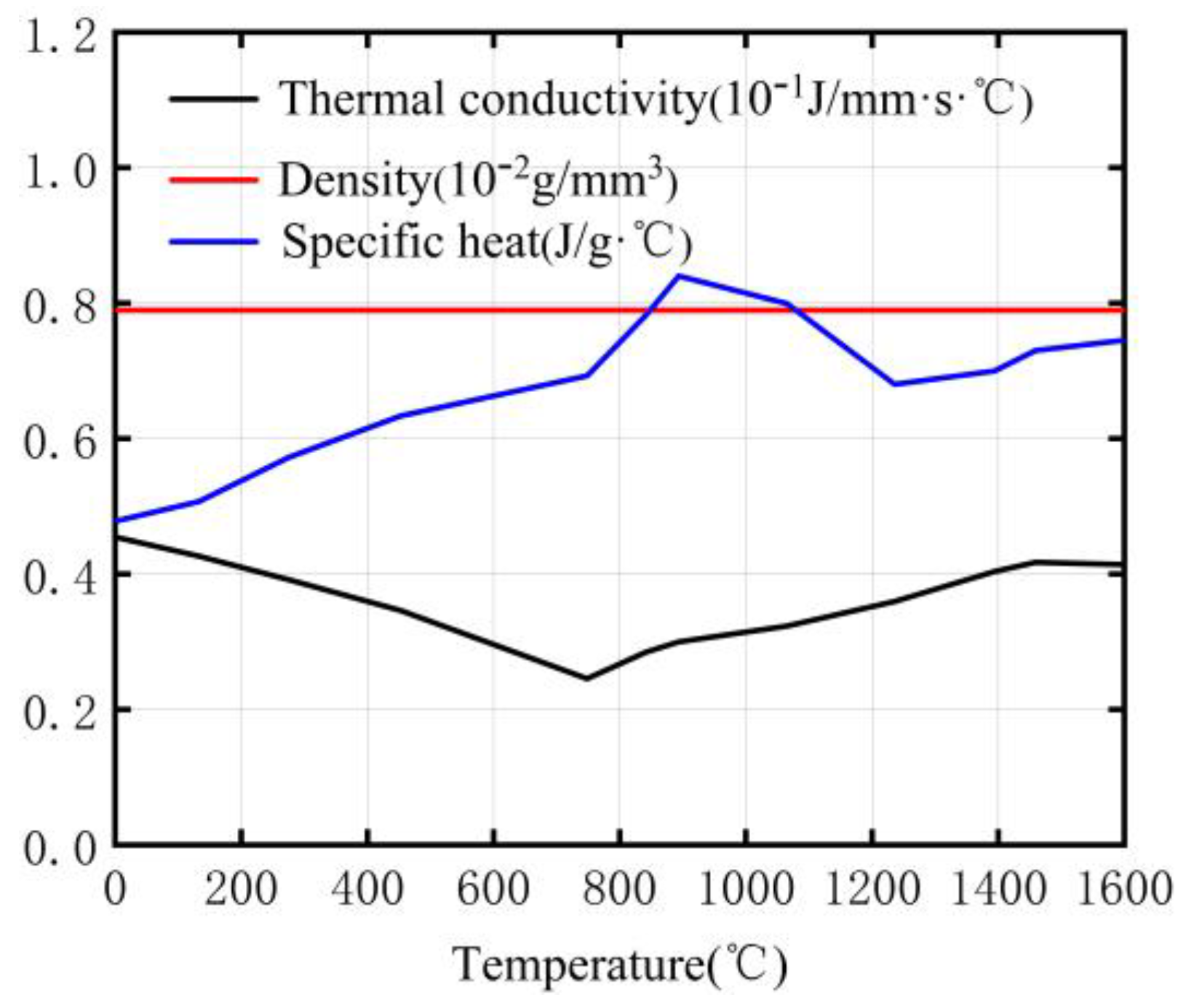

3.3. Thermal Analysis

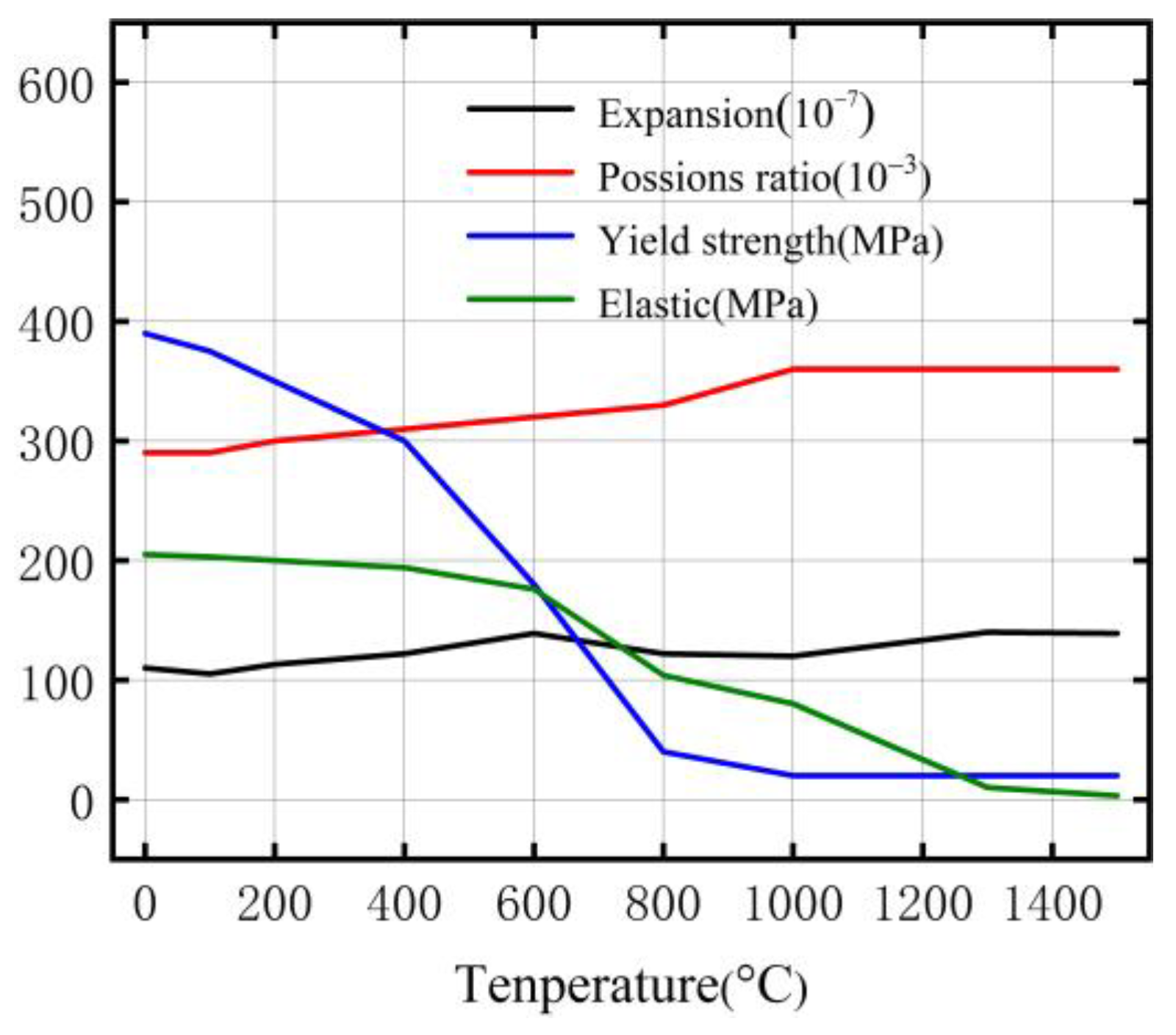

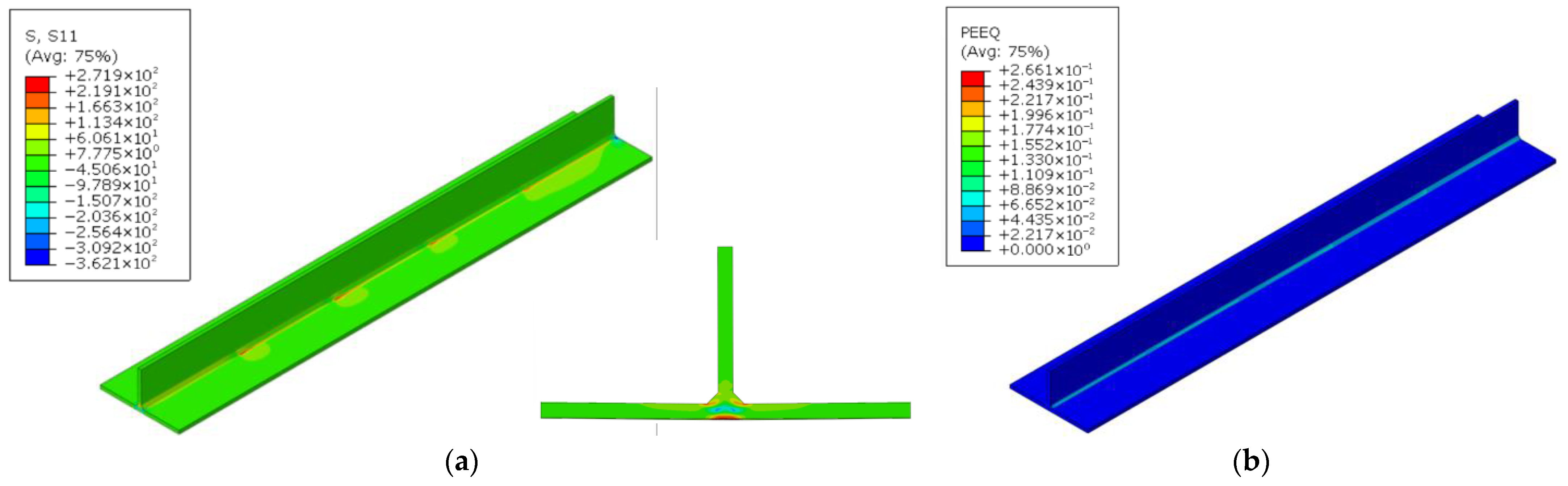

3.4. Mechanical Analysis

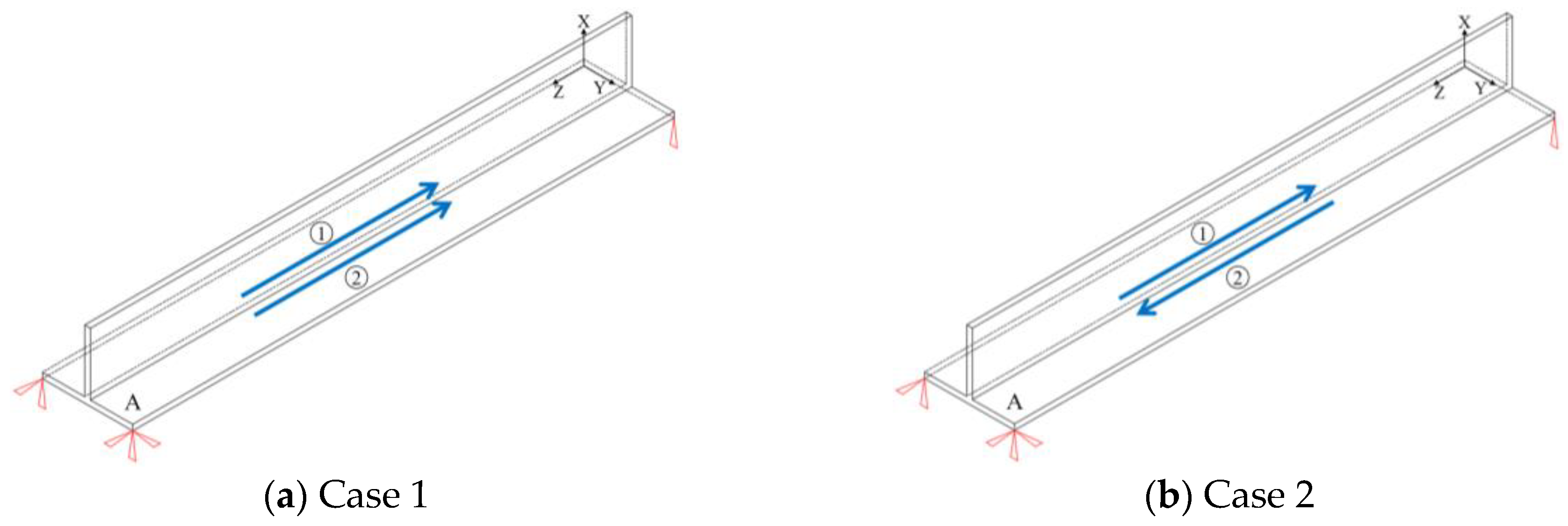

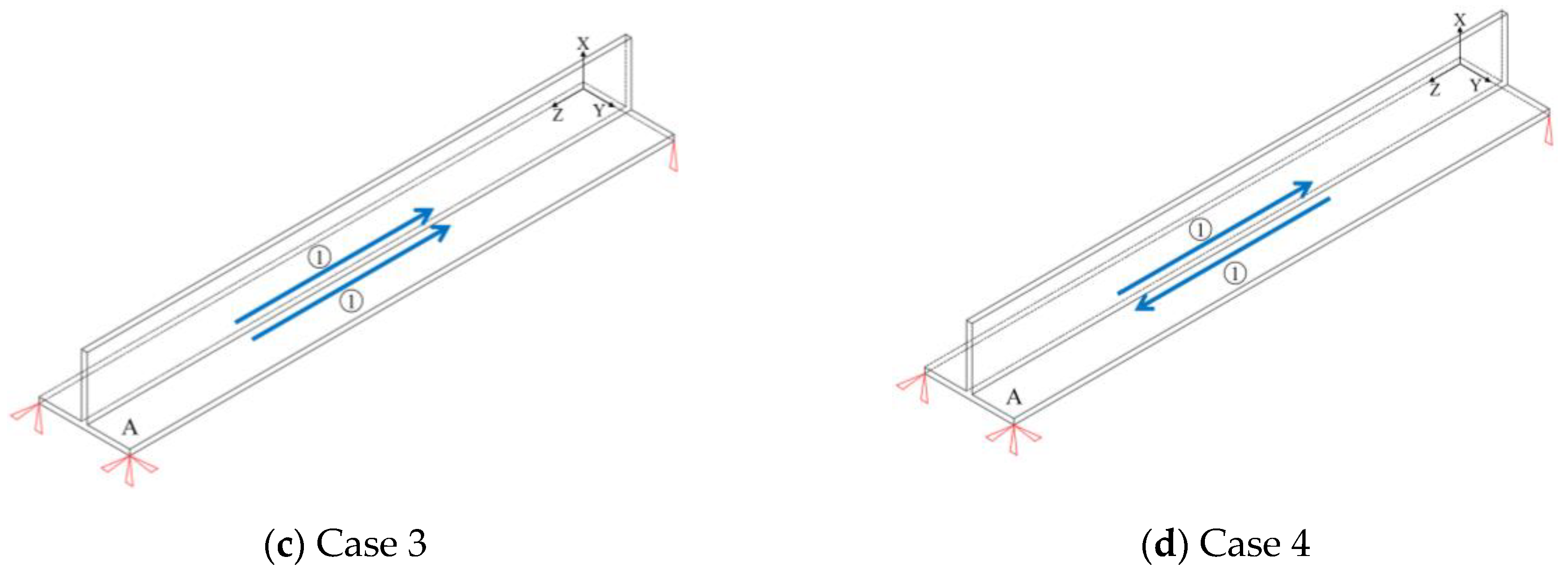

3.5. Welding Sequence Program

4. Results and Discussion

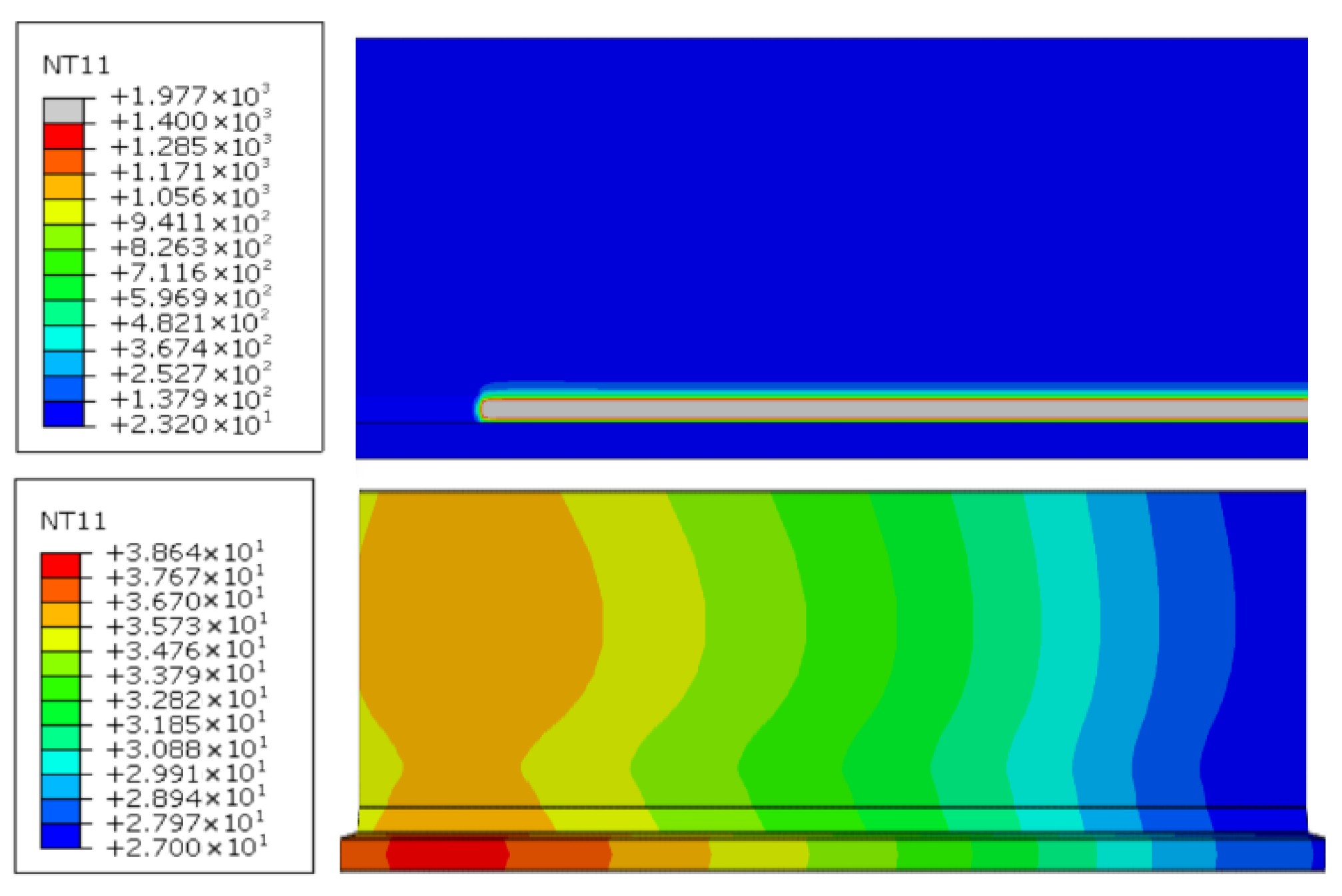

4.1. Temperature Field

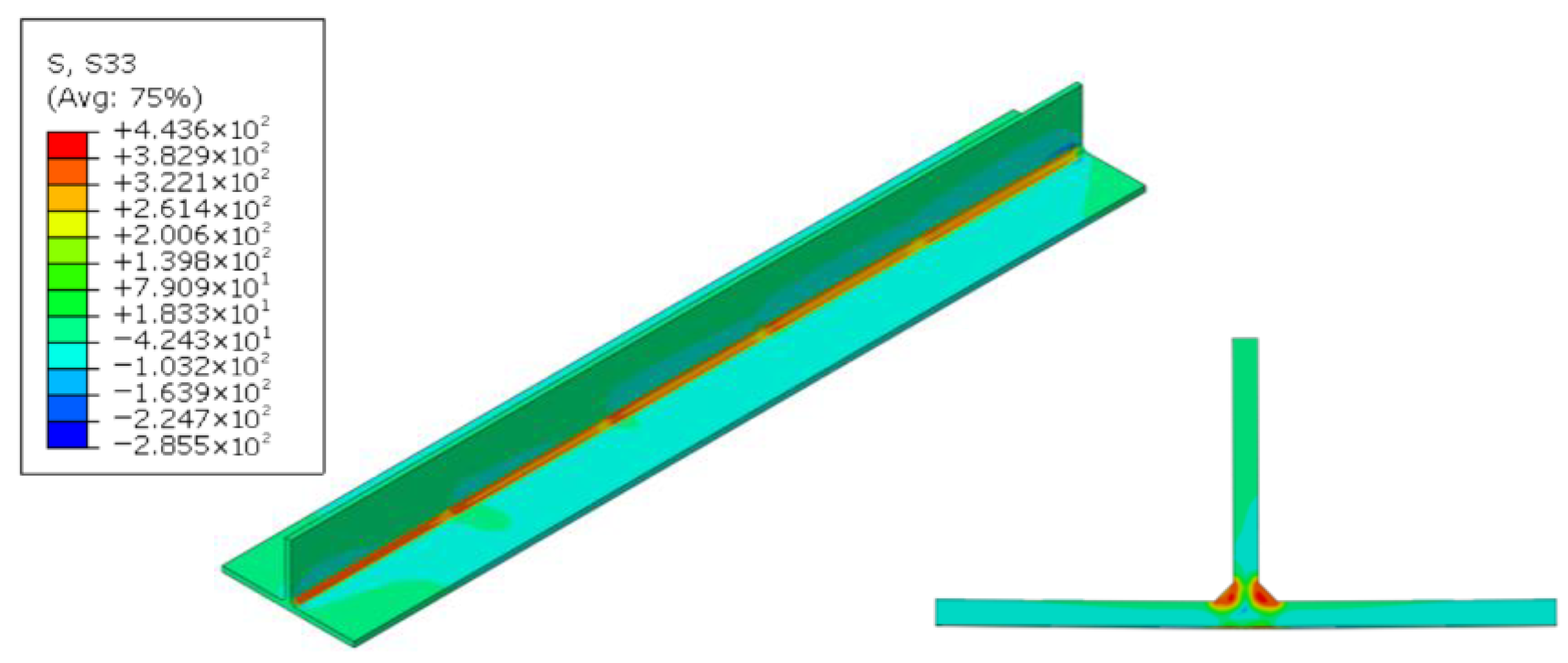

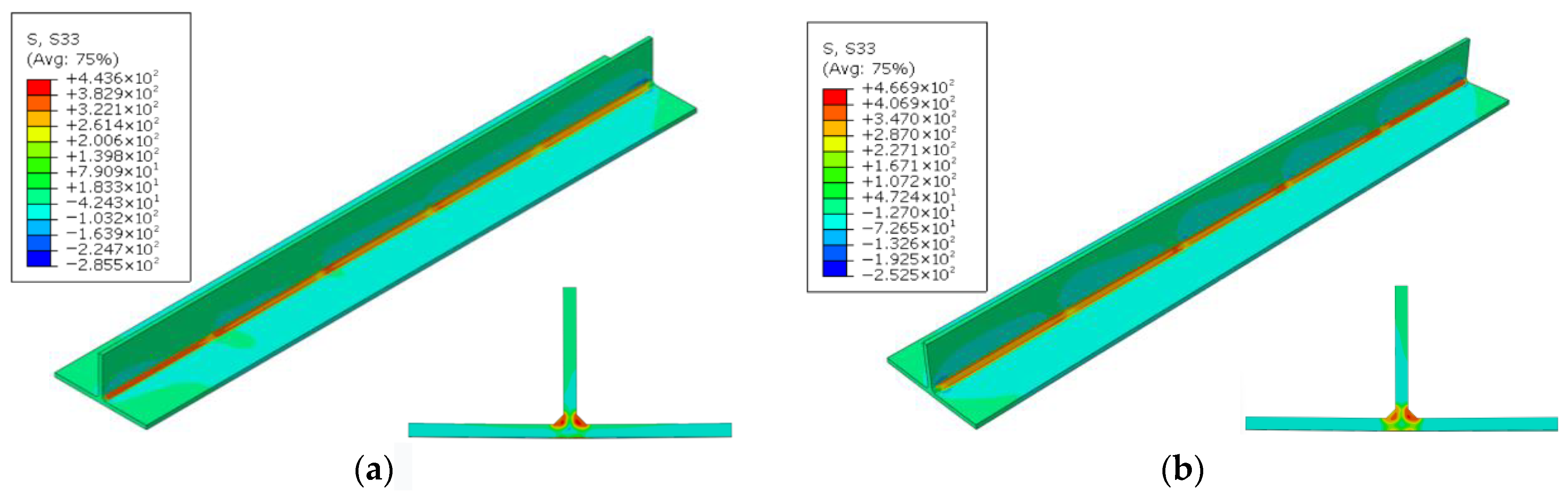

4.2. Stress Field

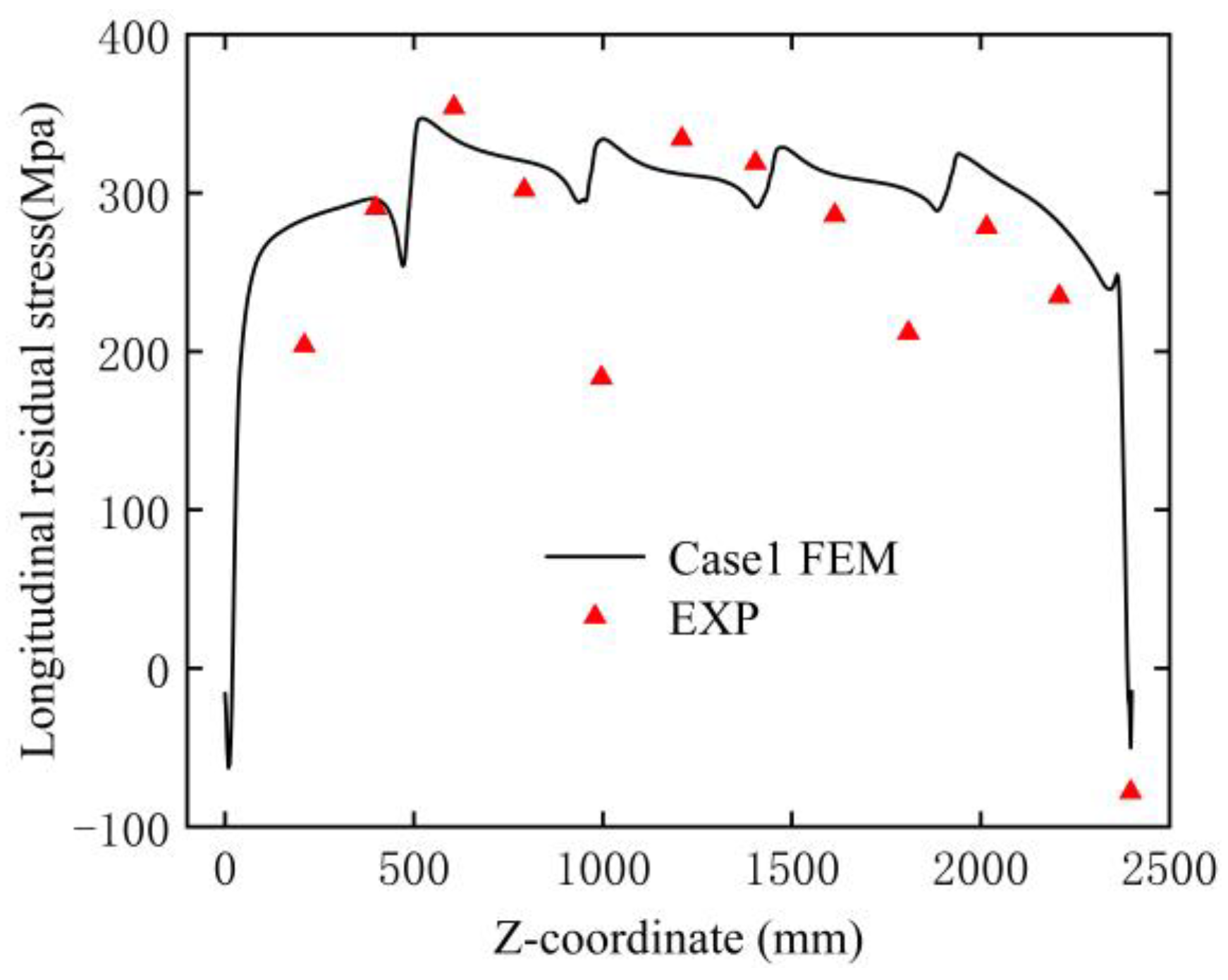

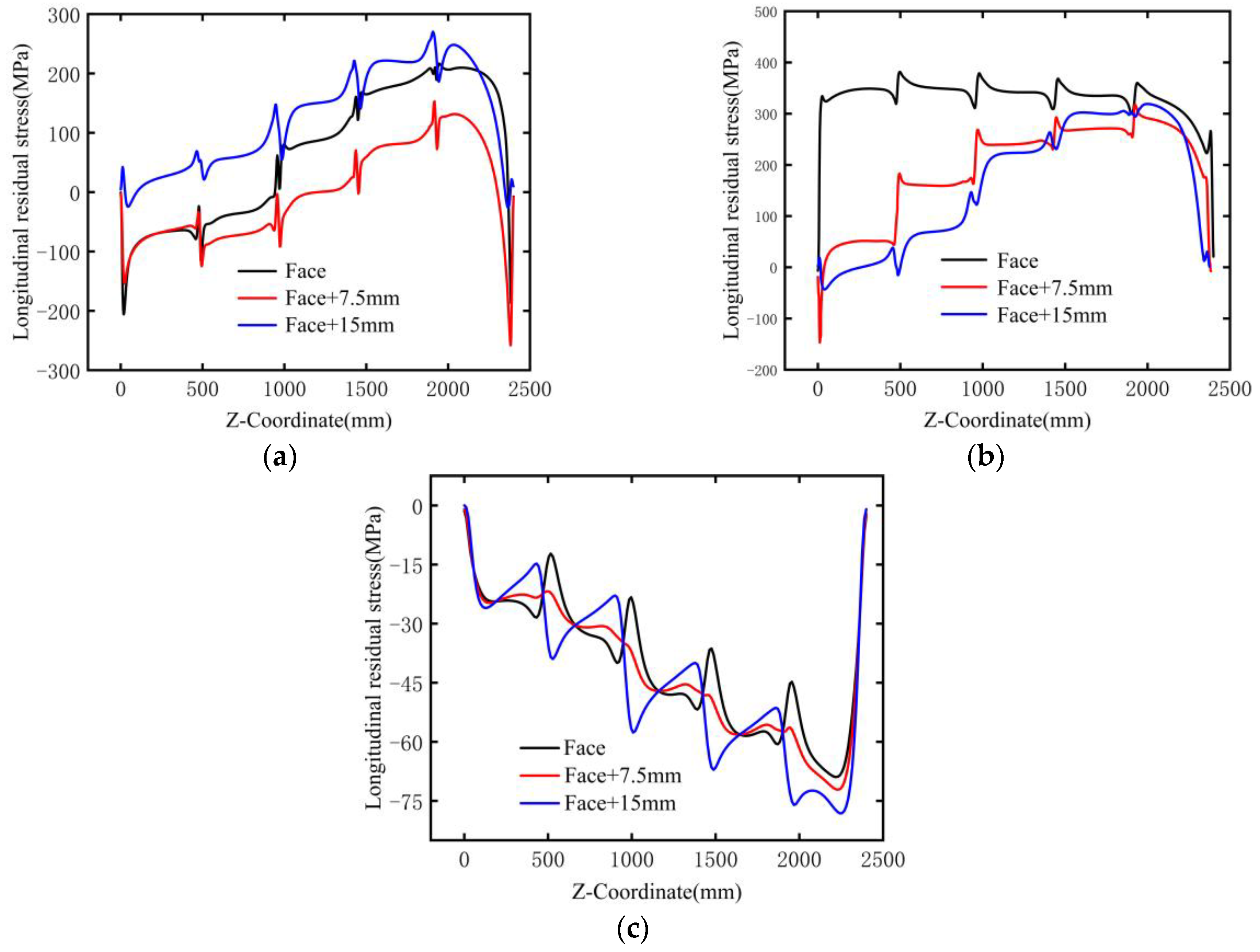

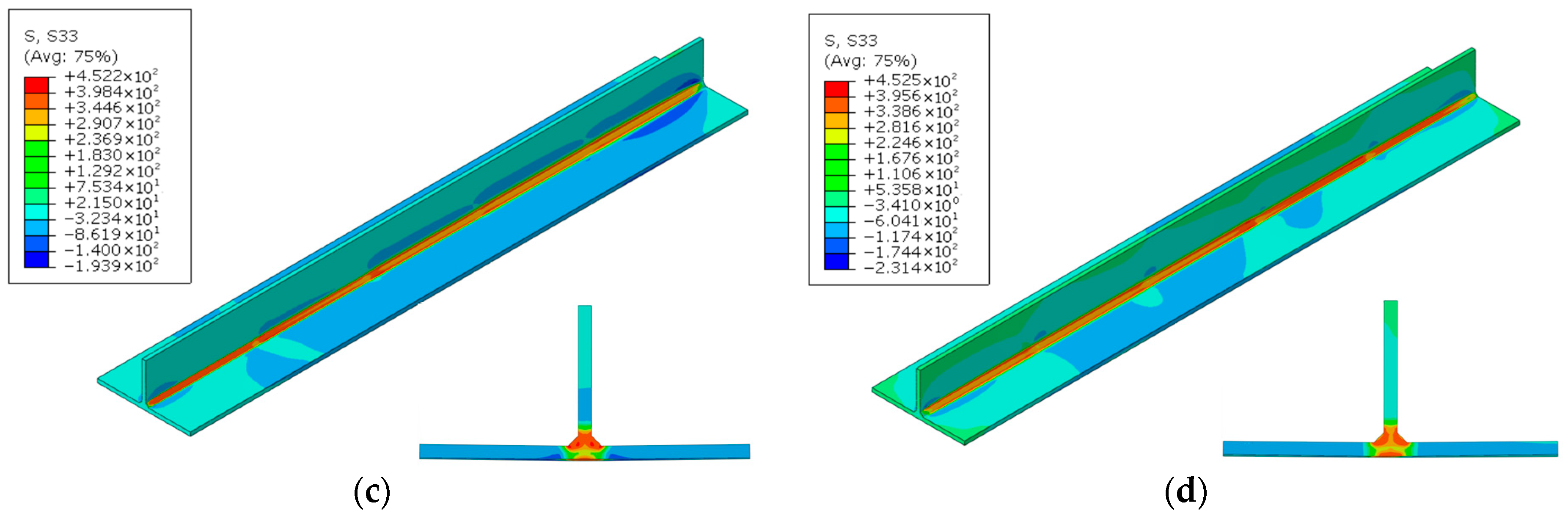

4.2.1. Longitudinal Residual Stresses

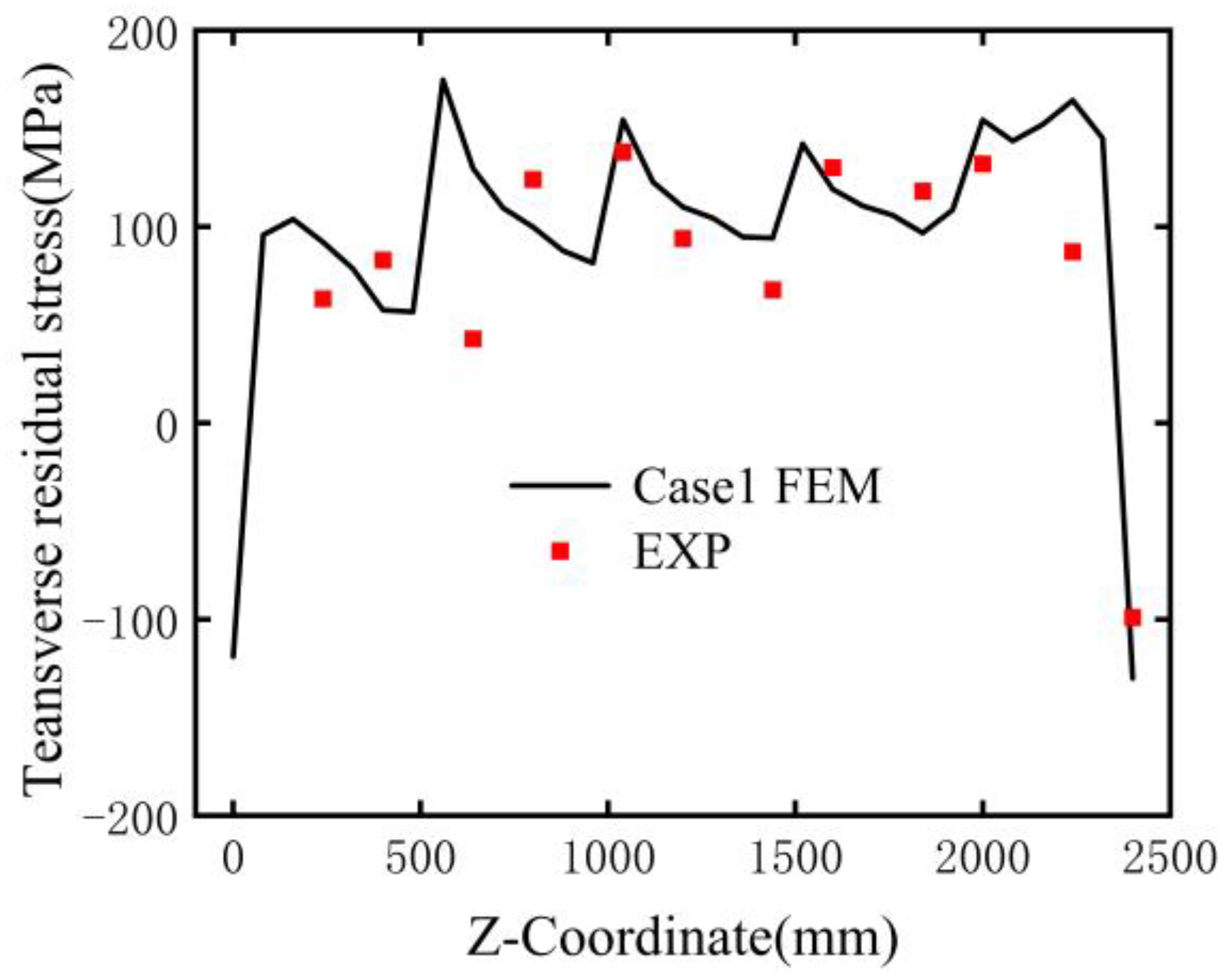

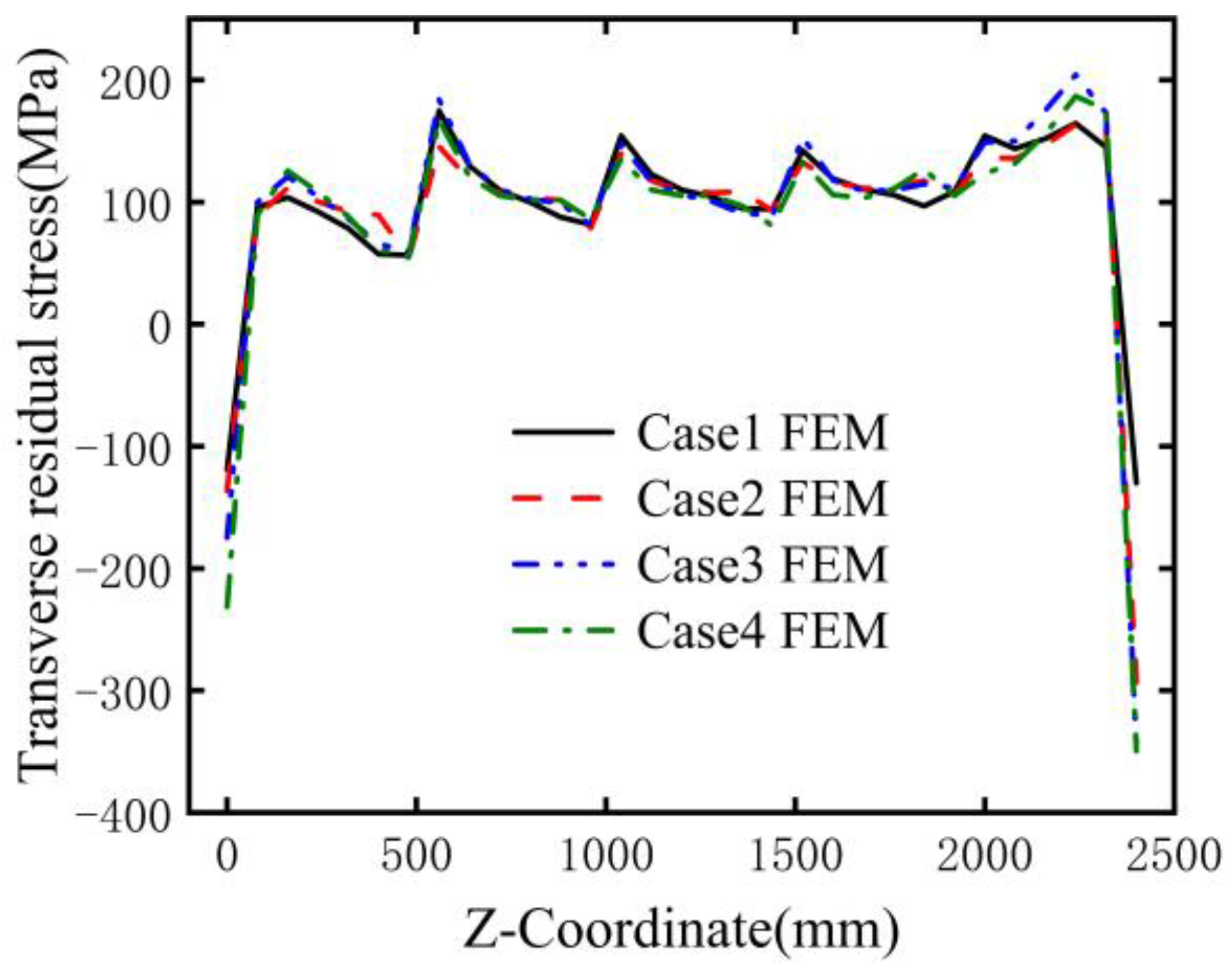

4.2.2. Transverse Residual Stresses

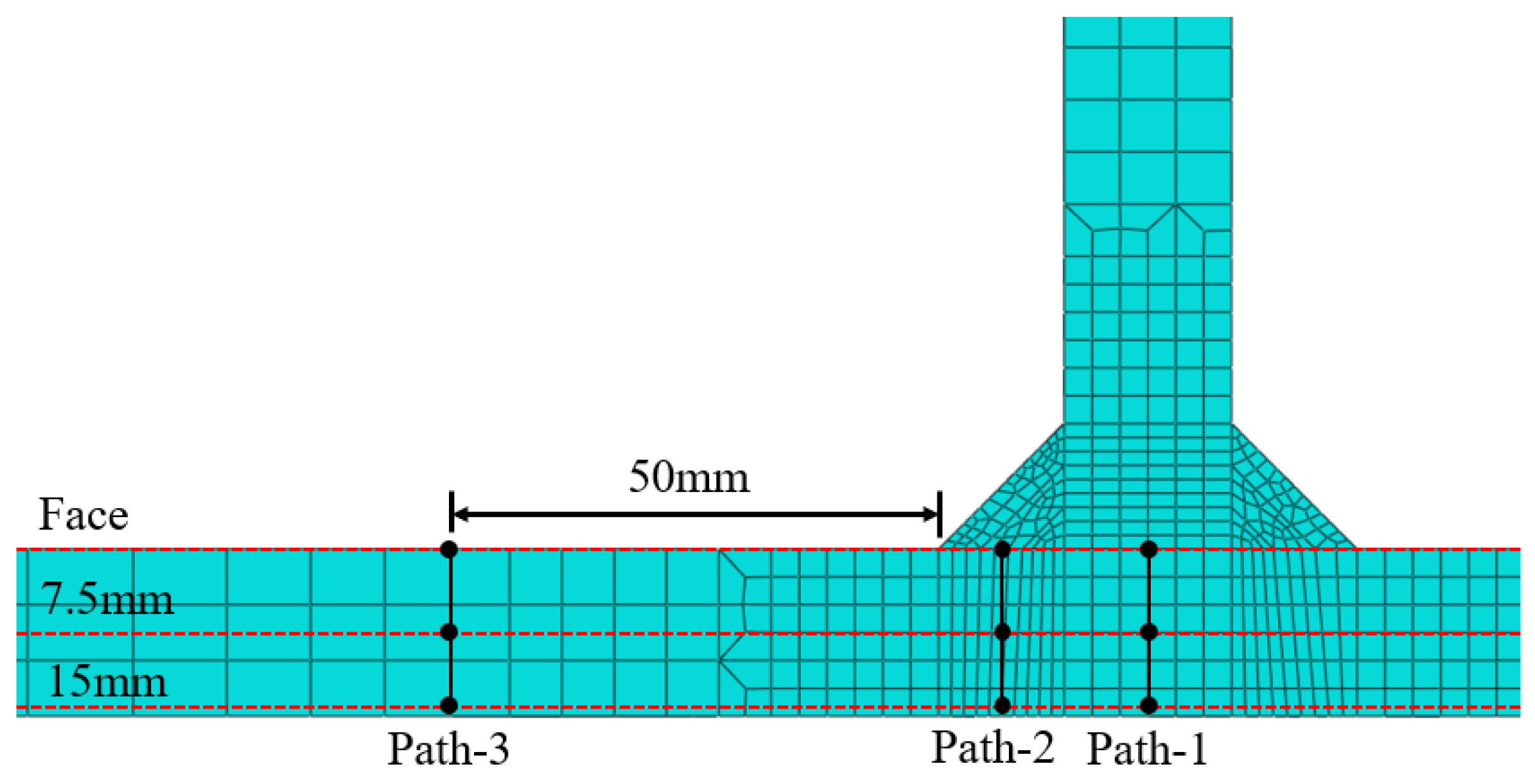

4.3. Distribution of Residual Stress Along the Thickness Direction

4.4. Effect of Welding Sequence

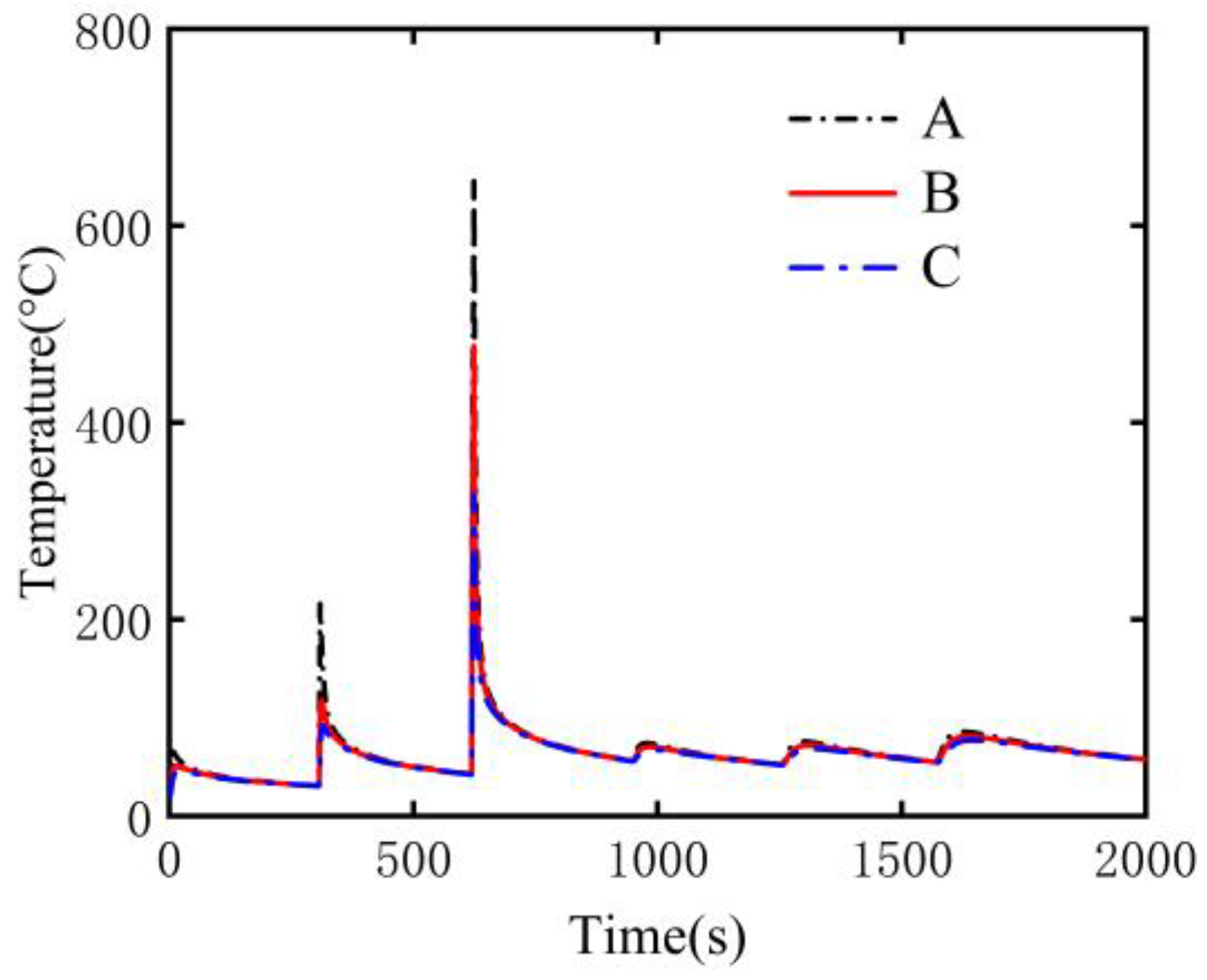

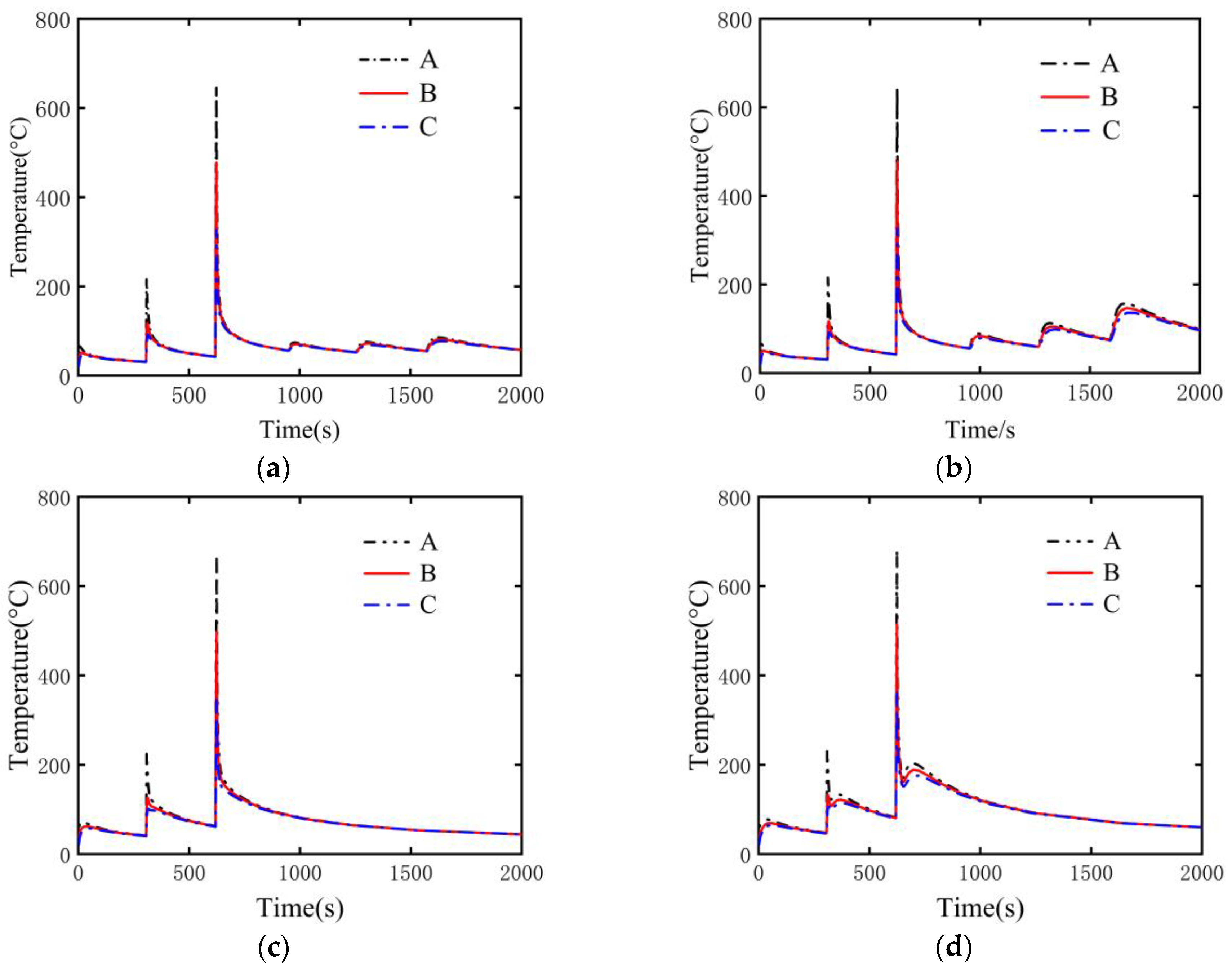

4.4.1. Temperature

4.4.2. Stress

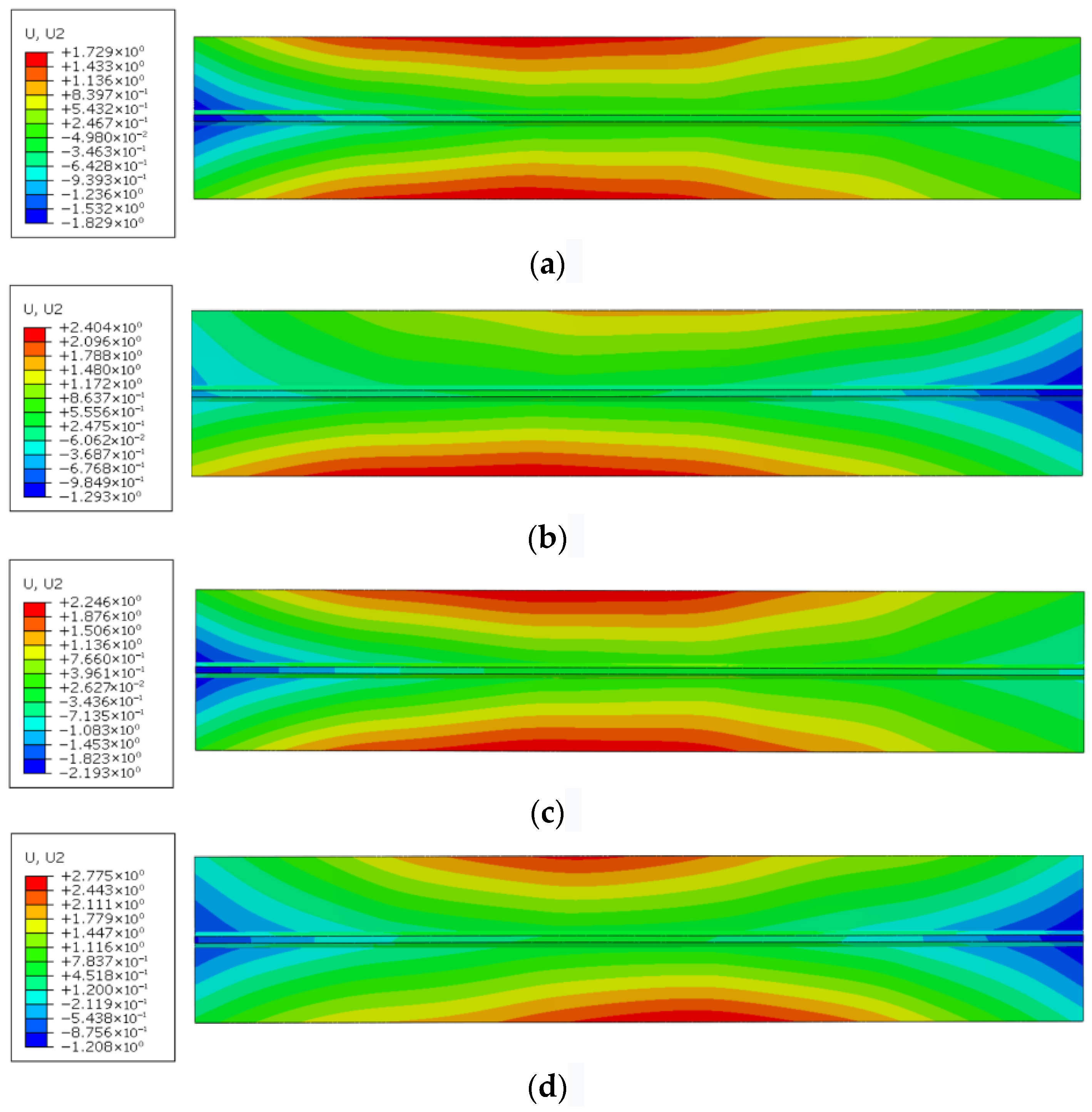

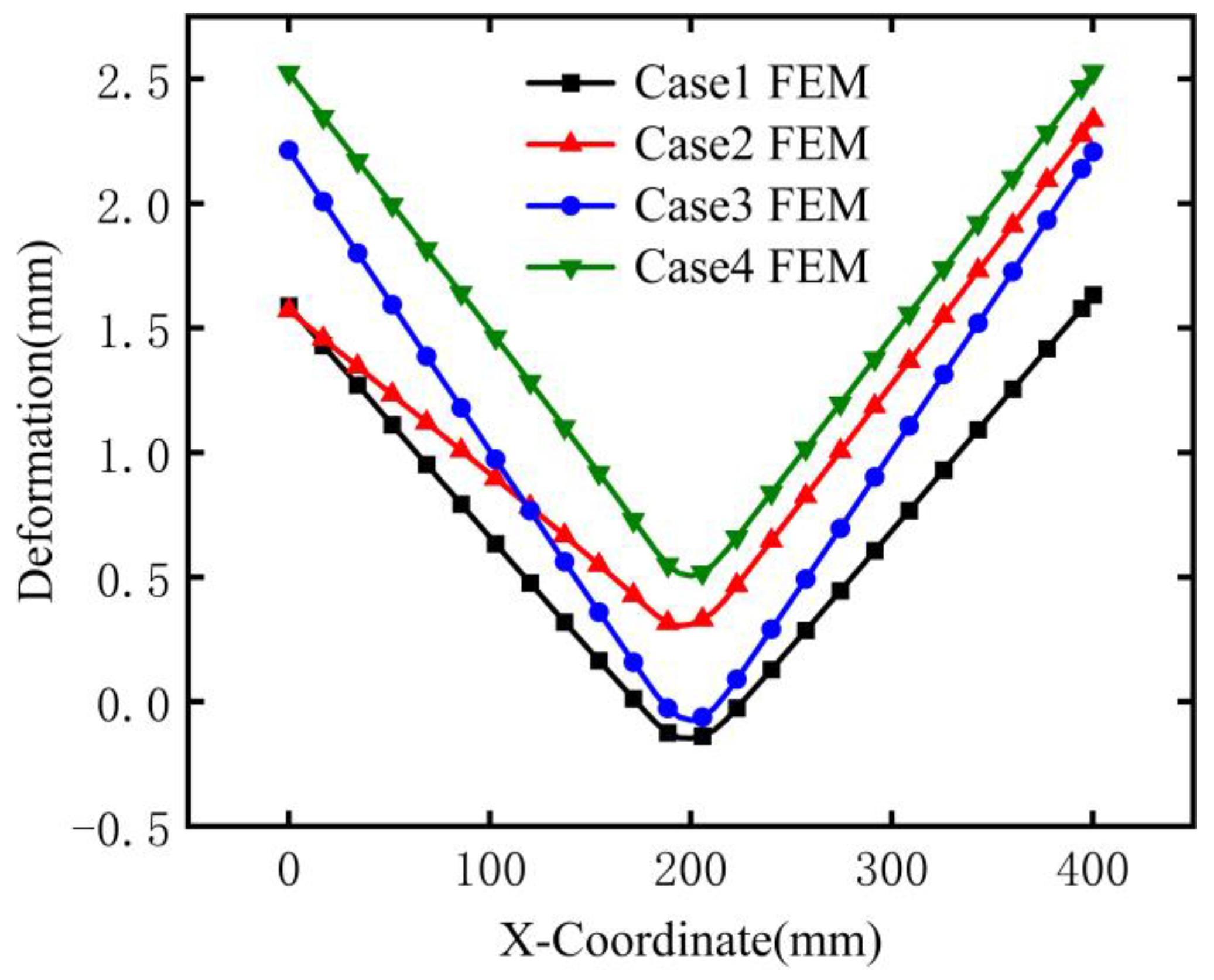

4.4.3. Deformation

5. Conclusions

- The residual stress predictions obtained with the segmented moving heat source show good agreement with experimental measurements, confirming the method’s validity. Furthermore, the required computation time of 38 h is significantly reduced compared to that of the conventional moving heat source approach, demonstrating enhanced efficiency.

- Based on the analysis of temperature–time curves at three fixed points, it was found that the temperature distribution is consistent with the heat source loading sequence. Compared to those during sequential welding, the temperature peaks at points A, B, and C are higher during simultaneous welding.

- The residual stresses along the weld seam exhibit a distribution pattern of being “high in the middle and low on both sides,” with the maximum measured tensile residual stress of 347 MPa occurring at the center of the weld. Compared to simultaneous welding on both sides, continuous welding effectively reduces the temperature gradient, thereby significantly lowering the residual stresses.

- The residual tensile stress on the base metal surface approaches the material’s yield strength, which significantly impairs the fatigue performance of the joint; this stress decays gradually along the thickness direction. Therefore, processes such as shot peening or heat treatment are required to reduce the surface stress and ensure long-term structural safety. Additionally, an alternating tensile–compressive–tensile distribution is observed at the connection between the base plate and the web plate, while regions away from the weld exhibit low-magnitude compressive stress.

- The deformation analysis across welding sequences shows two key findings: the location of maximum deformation is consistently at the web end and unconstrained edge, while the magnitude peaks under reverse simultaneous welding and minimizes under forward continuous welding. Our comprehensive assessment therefore recommends Case 1 as the optimal choice for practical engineering.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, Z.; Guo, Y. Research progress on welding residual stress and deformation in large or complex steel structure. J. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2016, 33, 108–119. [Google Scholar]

- De, A.; DebRoy, T. Aperspective on residual stresses in welding. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2011, 16, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramy, G.; Hidekazu, M.; Masakazu, S. Investigation of thickness and welding residual stress effects on fatigue crack growth. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2023, 201, 107760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, F.; Thomas, P.N. Residual stress relaxation in welded large components. Mater. Test. 2015, 57, 750–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Luo, J.; Li, L.; Long, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, S. Control of Welding Residual Stress in Large Storage Tank by Finite Element Method. J. Met. 2022, 12, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, G.; Cai, C.; Gao, H.; Wu, L. Numerical simulation of three-dimension stress field in double-sided double arc multipass welding process. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 499, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nose, M.; Amano, H.; Okada, H.; Yusa, Y.; Maekawa, A.; Kamaya, M.; Kawai, H. Computational crack propagation analysis with consideration of weld residual stresses. J. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2017, 182, 708–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, Z.; Wang, K.; Liang, S. Residual stress influence on fatigue crack propagation of CFRPstrengthened welded joints. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2022, 196, 107443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Luo, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, J.; Tu, S.-T. Residual stresses evolution during strip clad welding, post welding heat treatment and repair welding for a large pressure vessel. J. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2021, 189, 104259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, G.; Pu, X.; Deng, D. Influence of welding sequence on residual stress distribution and deformation in Q345 steel H-section butt-welded joint. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 13, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R.; Sunny, M.R.; Sarkar, A. Prediction of weld induced residual stress reduction by vibration of a T-joint using finite element method. Ships Offshore Struct. 2022, 17, 2722–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, H.; Correia, J.A.; Veljkovic, M.; Berto, F.; Manuel, L. Residual stress effects on fatigue life prediction using hardness measurements for butt-welded joints made of high strength steels. Int. J. Fatigue 2021, 147, 106175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Guan, Y.; Luo, K.; Wang, Q. Corrugated steel web I-girder welding deformation and residual stress research. J. Structures 2023, 58, 105602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri, M.; Ahola, A.; Ahn, J.; Björk, T. Welding-induced stresses and distortion in high-strength steel T-joints: Numerical and experimental study. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2022, 189, 107088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yin, D.; He, W.; Xie, D. Influence of welding sequences and boundary conditions on residual stress and residual deformation in DH36 steel T-joint fillet welds. J. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 204, 112337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, S.; Hu, L.; Deng, D. Effects of pass arrangement on angular distortion, residual stresses and lamellar tearing tendency in thick-plate T-joints of low alloy steel. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2019, 274, 116293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Fei, F.; Yu, S.; Liu, C.; Tang, J.; Yang, X. Numerical simulation of temperature field and residual stresses in stainless steel T-Joint. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2020, 73, 751–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Chang, Y.; Xu, J.; Huang, Y.; Lei, T.; Wang, C. Numerical analysis of welding deformation and residual stress in marine propeller nozzle with hybrid laser-arc girth welds. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2017, 158, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, M.; Nižetić, S.; Garašić, I.; Gubeljak, N.; Vuherer, T.; Tonković, Z. Numerical calculation and experimental measurement of temperatures and welding residual stresses in a thick-walled T-joint structure. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020, 141, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad, A.; Churiaque, C.; Sánchez-Amaya, J.M.; Abdel-Nasser, Y. Experimental and numerical investigation of hybrid laser arc welding process and the influence of welding sequence on the manufacture of stiffened flat panels. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 61, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Perrera, D.; Chung, H. Multi-Pass Welding Distortion Analysis Using Layered Shell Elements Based on Inherent Strain. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Luo, C.; Shen, J.; Zhang, Y. Numerical prediction of welding deformation in ship block subassemblies via the inhomogeneous inherent strain method. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 80, 860–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Liu, S.; Yuan, M.; Dai, X.; Lan, J. Immune optimization of double-sided welding sequence for medium-small assemblies in ships based on inherent strain method. J. Met. 2022, 12, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busari, Y.O.; Manurung, Y.H.P.; Shuaib-Babata, Y.L.; Ahmad, S.N.; Taufek, T.; Leitner, M.; Dizon, J.R.C.; Muhammad, N.; Mohamed, M.A. Experimental validation on multi-pass weld distortion behavior of structural offshore steel HSLA S460 using FE-based inherent strain and thermo-mechanical method. J. MRS Commun. 2022, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busto, V.; Coviello, D.; Lombardi, A.; De Vito, M.; Sorgente, D. Thermal finite element modeling of the laser beam welding of tailor welded blanks through an equivalent volumetric heat source. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 119, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, R.M.; Teixeira, P.R.F.; Vilarinho, L.O. Variable profile heat source models for numerical simulations of arc welding processes. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2022, 179, 107593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H.; Jin, H. An automated optimization procedure for geometry parameters calibration of two-curvature conical heat source model. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2024, 197, 108788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Cao, W.; Xu, X.; Shan, P.; Bu, X. Combined distribution band segmented moving heat source model. J. Trans. China Weld. Inst. 2010, 31, 95–97+104+117–118. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Bai, P.; Hu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R. Optimized segmented heat source for the numerical simulation of welding-induced deformation in large structures. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2018, 117, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Lei, M.; Luo, J.; Guo, X.; Deng, D. A segmented heat source for efficiently calculating the residual stresses in laser powder bed fusion process. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 79, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Lei, M.; Luo, J.; Guo, X.; Deng, D. Effect of structural restraint caused by the stiffener on welding residual stress and deformation in thick-plate T-joints. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 21, 3397–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wu, S.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, J. Establishment of segmented moving double ellipsoid heat source model in electron beam welding numerical simulation. J. Mech. Eng. 2004, 40, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Chen, Z.; Luo, Y. Welding Simulation of T-Shape Joint in Hull by Segmented Moving Heat Source. Shipbuild. China 2014, 55, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Alloy | C | Mn | Si | S | P | Cr | Mo | V | Cu | Ni |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q390B | 0.16 | 1.48 | 0.25 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Welding Consumable | C | Si | Mn | P | S | Mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFR-81A1 | 0.029 | 0.273 | 0.95 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.428 |

| Weld Pass | Voltage (V) | Current (A) | Welding Speed (mm/s) | Gas Flow (L/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22.3–27.6 | 146–195 | 4 | 18–26 |

| 2 | 21.4–27.6 | 130–178 | 3.3 | 18–27 |

| 3 | 21.6–27.6 | 135–184 | 3.1 | 19–27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yu, F.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Z.; Yan, Q.; Chen, Z.; Li, W.; Zhao, Y.; Niu, Y. Welding Residual Stress and Deformation of T-Joints in Large Steel Structural Modules. Buildings 2026, 16, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010153

Yu F, Li M, Zhang J, Ma Z, Yan Q, Chen Z, Li W, Zhao Y, Niu Y. Welding Residual Stress and Deformation of T-Joints in Large Steel Structural Modules. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010153

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Fengbo, Mingze Li, Jigang Zhang, Zhehao Ma, Qingfeng Yan, Zaixian Chen, Wei Li, Yang Zhao, and Yun Niu. 2026. "Welding Residual Stress and Deformation of T-Joints in Large Steel Structural Modules" Buildings 16, no. 1: 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010153

APA StyleYu, F., Li, M., Zhang, J., Ma, Z., Yan, Q., Chen, Z., Li, W., Zhao, Y., & Niu, Y. (2026). Welding Residual Stress and Deformation of T-Joints in Large Steel Structural Modules. Buildings, 16(1), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010153