Abstract

Building Information Modeling (BIM) is increasingly used to support green building design practices, yet its alignment with established green building assessment (GBA) tools remains underexamined. This study evaluates the extent to which Autodesk Revit, as a BIM tool, supports the calculation of energy-related indicators in GBA tools such as the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) method. A quasi-empirical, multi-method approach was employed, combining content analysis, a Revit-based simulation of a residential building, and structured evaluation by a panel of four experts. Using both subjective and objective measures, the experts assessed Revit’s effectiveness and the role of Revit’s media channels—modeling, simulation, data integration, and text documentation—in supporting and calculating LEED Energy and Atmosphere (EA) indicators. Results reveal that Revit is capable of effectively supporting 7 out of 11 LEED EA indicators. The highly supported indicators included minimum energy performance, building-level energy metering, optimized energy performance, advanced energy metering, renewable energy production, and enhanced refrigerant management while the fundamental refrigerant management indicator was evaluated as a moderately supported indicator. These highly supported indicators are core energy-related indicators; three of them are prerequisite indicators, while the remaining are credit indicators that cover 66.7% of the weight assigned for the EA indicators. The results also demonstrated that the remaining four indicators—fundamental commissioning and verification, enhanced commissioning, demand response, green power, and carbon offsets—were evaluated as poorly supported by Revit. The consistency of results across two rounds of survey, along with the expert’s consensus on 73% (8 out of 11) of the examined indicators, provides empirical validation of Rivet’s capacity to support LEED GBA. Findings also showed that modeling and simulation, followed by data integration, are the most impactful channels in supporting and calculating LEED EA criteria and requirements, with significant statistical correlation confirmed through Kendall’s Tau correlation. The findings have theoretical and practical implications for designers, green building practitioners, and BIM developers and suggest areas for further research.

1. Introduction

As a result of the recent focus on environmental sustainability, the building sector has come under increased scrutiny for its substantial energy consumption and carbon emissions [1,2]. In response, green building assessment tools have emerged as practices that aim to minimize environmental impact across a building’s lifecycle through a process called green building certification [3]. Over the last three decades or so, green building assessment (GBA) tools such as LEED, BREEAM, and Green Star have gained importance due to their ability to assess and rate green building performance in several areas, such as energy efficiency, emissions reduction, and occupant comfort [2,4,5]. However, GBA is a demanding process that includes extensive and highly structured calculations and documentation, and as such, aligning the assessment criteria and requirements of GBA tools with real-world design workflows remains a persistent challenge [6,7,8].

The literature highlights that architects and engineers in the building industry frequently encounter difficulties reconciling and aligning the requirements of GBA tools with the dynamic nature of architectural design processes [9,10]. These challenges pertain to several issues, such as the integration of a wide range of GBA criteria and requirements within the iterative design processes, accommodating the fragmented multidisciplinary inputs related to GBA, and the need for timely performance feedback throughout design [11,12]. Building Information Modeling (BIM) has been proposed to address some of these limitations by offering an integrated design platform for modeling, simulating, and optimizing green building performance [13,14]. While both BIM applications and GBA tools are oriented toward enabling high-performance green building design, the literature points out that they often operate independently and lack the necessary integration [15,16,17]. Although multiple research studies have examined BIM’s potential in facilitating and supporting the design of green buildings [18,19,20], empirical evaluations of BIM’s effectiveness in supporting GBA tools and their criteria are extremely limited or lacking. This paper seeks to fill this gap in knowledge and empirical evaluation. Specifically, this paper aims to examine and assess the capacity of BIM technology—using Autodesk Revit as a case study—to generate analytical data that supports the criteria and requirements of GBA tools, focusing on energy-related indicators in LEED, which are called ‘Energy and Atmosphere’ (EA) indicators. It seeks to evaluate the extent to which BIM outputs align with, support, and automate the calculation of GBA tools requirements, using LEED as a case. The paper reports data from a larger research project that investigates the role and effectiveness of BIM tools in supporting and automating the calculation of a wide range of GBA criteria, including energy-related ones.

Assessment of energy performance is a key parameter in green building design. Energy-related criteria form the core of most—if not all—GBA tools. In LEED, for example, the Energy and Atmosphere (EA) category includes a set of eleven indicators, referred to as prerequisites and credits, that assess key areas of energy performance, including minimum energy performance, optimization of energy use, enhanced commissioning, and energy metering. Quantifying and assessing these energy-related criteria is demanding and requires highly structured calculations and documentation to demonstrate compliance. Addressing these energy performance criteria in the early design stages is essential to ensure that energy performance considerations are deeply embedded into design workflows. Despite its importance, the incorporation of energy performance assessment within early design phases remains inconsistently implemented [21]. The literature indicates that BIM technologies provide substantial support in this regard by offering a building design tool integrated with energy modeling and simulation capabilities [14]. However, there has been limited research examining the actual effectiveness of BIM technologies in supporting GBA tools or the level of alignment between BIM outputs and the complex, documentation-intensive processes required for GBA and green building certification [22]. Research in this area remains limited in size and scope, fragmented, and largely lacking an empirical foundation.

Recent studies have extended this line of inquiry, yet most remain conceptual or case-based rather than evidence-based and empirical evaluations. For example, “Khan et al. [23] demonstrated BIM’s potential for optimizing energy efficiency through orientation modeling in diverse terrains”, while “Solomon et al. [24] employed a BIM-enabled life-cycle assessment to quantify embodied carbon in construction materials”. Similarly, “Cornely et al. [25] and Chen and Gallardo [26] emphasized the advantages of BIM-based eco-design and multi-objective optimization in supporting sustainable material selection”. Other studies, such as “Najjar et al. [27] and Salem and Elwakil [28], have validated BIM’s role in improving energy performance across climates”. Collectively, these efforts underscore BIM’s growing effectiveness in supporting simulation-based energy analysis and life-cycle assessments; however, they also reveal a disproportionate emphasis on performance modeling over certification alignment. Recent directions, such as BIM-FM integration with IoT for real-time energy management, sustainable BIM-IoT frameworks for dynamic data exchange, and BIM-assisted circular economy applications, extend BIM’s scope beyond design but remain largely exploratory. Even BIM-based material and envelope studies using Revit/GBS [29] focus primarily on predictive efficiency rather than standardized assessment outputs. Together, this body of work highlights a persistent gap: while BIM has evolved into a powerful analytical and management tool, its direct capacity to operationalize and automate the calculation of energy-related indicators required by GBA frameworks—particularly within LEED’s Energy and Atmosphere category—remains empirically underexplored. This study addresses that gap by empirically evaluating Autodesk Revit’s ability to bridge this disconnect between BIM functionality and LEED’s energy-related certification requirements. The study contributes to the growing discourse on the integration of BIM with GBA tools to support and automate the calculation of the metrics required for these tools, focusing on energy assessment.

The paper is organized as follows: this section introduces the status of research on BIM and its support for green building practices, as well as the rationale for the study. Section 2 presents the research methodology adopted in the study. Section 3 outlines the results of the data analysis, while Section 4 presents the findings and discusses their implications. The last section summarizes the conclusions and presents potential areas for further research.

2. Methodology

The study is part of a larger research project that investigates the extent to which BIM tools support and automate the calculation of a wide range of GBA criteria in the context of the Saudi Arabian building industry. To examine the complex relationship between GBA tools and BIM tools, a multi-method approach is used to strengthen the study both theoretically and methodologically. In this regard, the study adopted a quasi-empirical research design that used the following research methods: extensive literature review, content analysis of sample GBA tools, case study of a BIM simulation of a residential building, and expert panel evaluation survey.

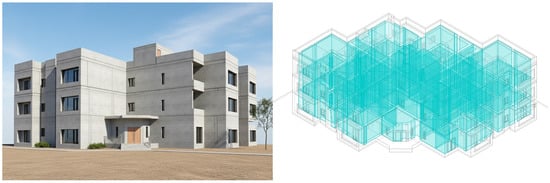

The study used purposive sampling to select a representative sample of BIM tools, GBA tools, and a typical building type. During the scoping phase, and based on an established set of criteria, LEED is selected as a representative GBA tool, while Autodesk Revit is selected as the BIM tool. LEED is a globally recognized and extensively utilized GBA tool worldwide and in the region [30], while Revit is one of the most widely used BIM packages in the building industry [31,32,33]. The specific versions examined in the study are Revit 2023 and LEED for New Construction and Major Renovation, dedicated to residential buildings (LEED BD+C version 4.1). A typical three-floor residential building is used as a case study, as shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. Multi-story residential buildings are among the most common building types in the region and globally. The literature points out that the residential sector is the second largest consumer of electricity in Saudi Arabia and accounts for almost 52% of total national electricity consumption [34].

Table 1.

The information of the simulated residential case study.

Figure 1.

Snapshot of the Revit model of the residential case study.

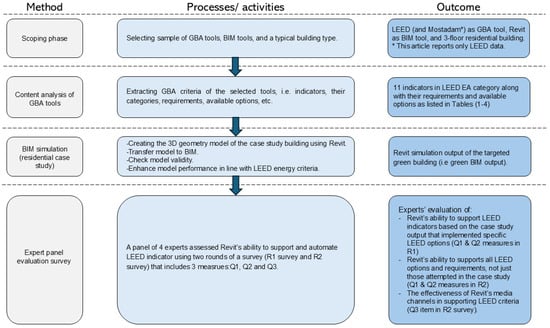

Following the scoping phase, the research methodology, as shown in Figure 2, comprised three phases: (1) extracting green building assessment criteria from LEED; (2) developing a BIM model and simulation of the case study building using Revit and enhancing its performance to meet green building criteria as per LEED standards; and (3) assessing the level of support provided by Revit for LEED’s energy-related criteria using both objective and subjective data.

Figure 2.

Outline of research methodology.

In the first phase, through content analysis of LEED documentation as found in LEED reference guide [35], the researchers extracted all the Energy and Atmosphere (EA) indicators and the various options or sub-indicators available for each indicator. The LEED EA category includes 11 indicators: 4 mandatory prerequisites and 7 optional credits. Compliance with EA indicators involves navigating a total of 29 specific requirements (or sub-requirements within the indicators’ scope), which can be fulfilled through 16 distinct options of compliance. Five of the indicators, such as the minimum energy performance and enhanced commissioning, offer the choice of two to three compliance options, while other indicators define a single set of requirements or options to achieve.

The second phase involved developing a BIM model of the case study building. This process began by creating a detailed 3D model using Revit based on the as-built drawings of the building. The model was then enriched with essential engineering data and other relevant technical information. A structured validation process was implemented to ensure accuracy and reliability. Initially, the model was checked to verify its consistency with the actual building as per available as-built documentation. Subsequently, the energy performance of the simulated building was compared with that of the actual building as reported in the real-life energy consumption data. After verifying the accuracy of the simulation, some modifications were introduced to the model to enhance its performance in line with LEED green building criteria.

In the third phase, a panel of four experts in BIM and GBA tools examined the output data generated by Revit and compared it with LEED requirements to evaluate the level of Revit’s support for LEED EA indicators. To conduct a reliable assessment, the expert panel was presented with concise but comprehensive information about Rivet’s output and LEED requirements and expectations for each indicator, as follows: First, the definition and objectives of each indicator were introduced. Then LEED requirements for each indicator were presented in a tabulated format, including the various available options, highlighting the option(s) adopted in the case study. Next, Revit-generated output data mapped to the corresponding LEED requirements were presented. Finally, after a 2 minute period for questions and answers about the presented data, the panelists were asked to assess Revit’s ability to support and automate the addressed LEED indicator using two rounds of a survey instrument (R1 survey and R2 survey). In the first round (R1), the survey consisted of two questions (Q1 and Q2) that evaluated Revit’s ability to support and calculate the requirements of the addressed LEED EA indicator based on the output data generated from the case study that adopted/implemented specific LEED options. The second-round survey (R2) included three questions: the first two of them are the same Q1 and Q2 used in the first round but rephrased in order to evaluate Revit’s ability to generate proper output that supports all options and requirements of the LEED EA indicator, not just those attempted in the case study. The third question (Q3) evaluated the effectiveness of Revit’s media channels in supporting the corresponding LEED indicator. Thus, the round-2 survey collected data based on the expert’s domain knowledge in light of the presented information. Further details about the two rounds of the survey are provided in the analysis and results section.

Data Analysis

Since LEED assigns different point values (or weights) to each indicator, and in order to enable direct comparisons among indicators in terms of “achieved/achievable” points, the achieved points for each indicator as measured in Q1 were normalized to a common 7-point scale. Specifically, the “achieved/achievable” points for each indicator were divided by its assigned weight and then multiplied by 7, such that the resulting values ranged from 0 to 7. This procedure yields normalized values, comparable across indicators without altering their internal proportional relationships.

Data from the expert panel survey was analyzed using a range of statistical measures. Determining the level of consensus and agreement among experts regarding Revit’s support for and automation of LEED criteria and requirements is a key issue in the analysis. Mean or median scores and the interquartile range (i.e., the absolute difference between the 25th and 75th percentiles in a dataset) were used to determine consensus among panel members. The interquartile range (IQR) is a common method to measure consensus, where a smaller value indicates a higher degree of agreement [36,37,38,39,40]. This literature states that for responses measured on a 7-point Likert scale, an IQR of ≤1 indicates strong consensus among experts, while an IQR above 1 reflects a lack of consensus. Accordingly, to determine the level of consensus or agreement among experts, the results of the 7-point Likert scale survey were examined to identify four possible outcomes:

- -

- Consensus that the LEED indicator is highly supported by Revit when (IQR ≤ 1 and the mean score ≥ 5.5).

- -

- Consensus that the LEED indicator is moderately supported by Revit when (IQR ≤ 1 and 3 ≤ mean ≤ 5.5).

- -

- Consensus that the LEED indicator is poorly supported by Revit when (IQR ≤ 1 and the mean < 3).

- -

- When (IQR > 1), no consensus was reached.

3. Analysis and Results

In a quasi-empirical research design, a panel of four experts evaluated the ability and effectiveness of Revit, as BIM software, to support and automate LEED green building criteria related to the ‘Energy and Atmosphere’ category using a survey instrument. The expert panel provided their feedback during two rounds of a survey instrument. The analysis and the result of the experts’ feedback are presented below.

3.1. Results of Round 1: Revit Support for LEED EA Indicators Based on the Case Study Results

During round-1 of the survey, and after presenting the panel with the expected LEED requirements and expectations for the EA indicator being considered along with the corresponding results of the simulated case study, the panel of experts was asked to evaluate the performance of Revit based on the results of the case study using the following two questions: (Q1) “Based on the presented data of the case study, indicate the number of points that Revit is able to achieve out of the ‘possible points’ assigned for the indicator being considered,” and (Q2) “On a 7-point Likert scale, and based on the presented data of the case study, rate the extent to which Revit is able to achieve the requirements of the LEED indicator being considered”.

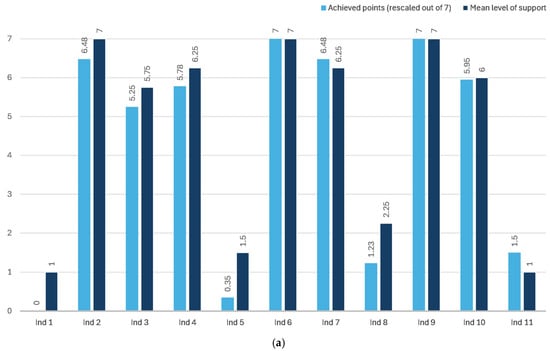

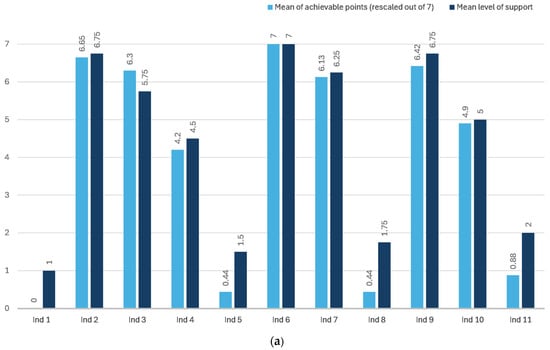

Table 2 presents a summary of the experts’ assessment of Revit’s support for each LEED EA indicator using the two survey items (Q1 and Q2), while Figure 3 provides a visual representation of this data using bar and radar charts. The maximum possible points assigned to LEED EA credit indicators are 33 as shown in Table 2 and the rest of the Tables. The prerequisite indicators have no points assigned but any project cannot be considered for certification if it did not meet all these indicators, and the estimated cut point for each prerequisite indicator is 10 points. Since each indicator has a different number of points, and to enable comparison between indicators, the mean of achieved points (out of possible points) as quantified in Q1 is rescaled to be out of 7. While Q2 captures subjective data on a 7-point Likert scale, Q1 captures objective data since it is based on actual field inspection of the Revit output. These two measures are based on the Revit-generated data based on LEED options implemented/attempted in the case study.

Table 2.

Results of round-1 survey: Experts’ assessment of level of support of Revit for LEED Energy and Atmosphere (EA) indicators based on case study results (i.e., attempted options).

Figure 3.

Expert’s assessment of Revit’s level of support for LEED EA indicators based on the case study results (i.e., attempted options) as per R1 survey. (a) clustered bar chart for the mean of achieved points (Q1 normalized out of 7) and the mean level of support rated on a 7-point scale (Q2); (b) radar chart of mean level of achieved points (Q1), and (c) radar chart of mean level of support (Q2).

3.2. Results of Round 2: Revit Support for EA Indicators Based on LEED General Requirements and Options

In this round, the survey included 3 questions (Q1, Q2, and Q3). The first two questions are rephrased versions of those used in round-1 survey, aiming to evaluate the potential of Revit to achieve all the options and requirements of each LEED indicator, not just those attempted in the case study. The two questions were: Q1) “Considering all possible options specified by LEED for the indicator being considered, indicate the number of points that Revit can achieve out of the ‘possible points’ assigned for the indicator”, and Q2) “On a 7-point Likert scale, and considering all possible options specified by LEED for the indicator, rate the extent to which Revit can achieve the expected requirements of the LEED indicator being considered.”

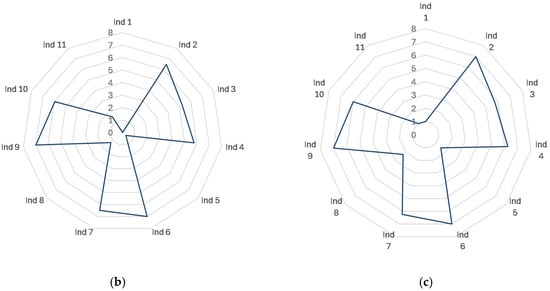

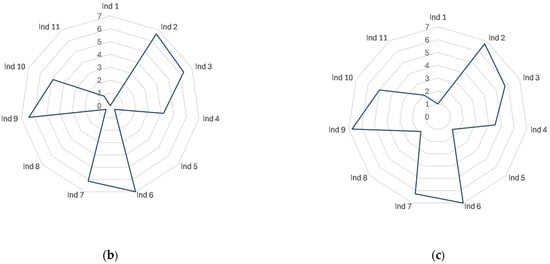

Table 3 presents a summary of the experts’ assessment of Revit’s support for each indicator using the two measures (Q1 and Q2) in round-2 of the survey, while Figure 4 provides a graphical representation of the same data using bar and radar charts. In round-2 of the survey, the two items (Q1 and Q2) measure the experts’ evaluation of Revit’s potential capability to support any of the available options/requirements for each EA indicator as specified in the LEED documentation based on their expertise in the field. As such, both in this round of the survey, Q1 and Q2 measures capture subjective data, as they represent experts’ opinions regarding Revit’s potential to support any of the available options for LEED criteria, including the options/sub-indicators not adopted in the case study. As done in round-1, the mean of achievable points in Q1 is rescaled to be out of 7 for comparison purposes.

Table 3.

Results of round-2 survey: Experts’ assessment of the level of support of Revit for LEED EA indicators based on its potential to achieve required LEED points based on any of the available options, including the not attempted options.

Figure 4.

Expert’s assessment of Revit’s level of support for LEED EA indicators based on its potential to achieve all possible LEED points based on any of the available options and requirements as per R2 survey. (a) clustered bar chart for the mean of achieved points (Q1 normalized out of 7) and the mean level of support rated on a 7-point scale (Q2); (b) radar chart of mean level of achieved points (Q1); and (c) radar chart of mean level of support (Q2).

3.3. Expert Consensus on the Level of Revit Support for LEED Indicators

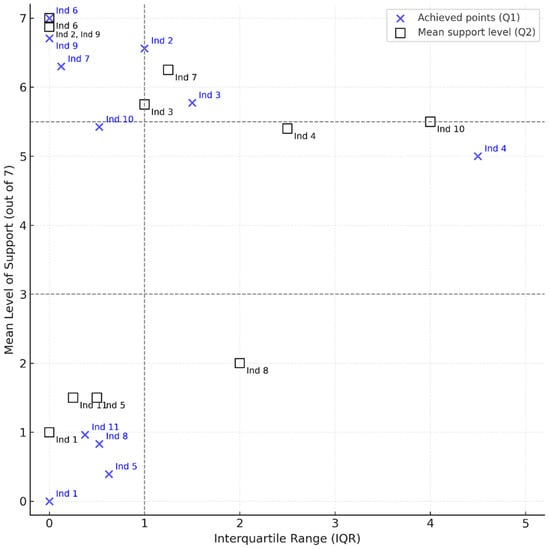

To establish a composite assessment metric, the measurements collected in both round-1 (assessment based on case study results) and round-2 (assessment based on documented LEED requirements including all available options) are aggregated into one score as shown in Table 4. In doing so, corresponding data from the two survey rounds (R1 and R2) were combined to result in two aggregated scores/metrics for the level of support of Revit for LEED indicators: one metric is based on Q1 data (number of points achieved rescaled as a ‘fraction of 7’) aggregated from both rounds, and another metric is based on Q2 data (7-point Likert scale) aggregated from both rounds. In addition to the aggregated mean support level, Table 4 also shows the consensus level among participating experts operationalized as the interquartile range (IQR) as introduced in the methodology section. Figure 5, on the other hand, provides a visual representation of the expert’s consensus and Revit’s level of support across all examined indicators based on IQR and mean support scores.

Table 4.

Aggregate level of support of Revit for LEED EA indicators based on the results of the two rounds, R1 and R2.

Figure 5.

Expert’s consensus on Revit’s level of support across all examined indicators.

3.4. Revit Media Channel Support for LEED EA Indicators

During round-2 survey, the panel of experts also evaluated the importance or effectiveness of each Revit media channel in supporting or achieving the requirements of each LEED EA indicator based on the data presented. In Q3 of round-2 survey, the experts were asked, “On a scale of 1–10, rank the importance/effectiveness of each Revit media channel in achieving the requirements of the LEED indicator being considered”. A rank of 10 indicates that the media channel is most effective/important in achieving the indicator requirements; a rank of 1 indicates the least effectiveness or importance.

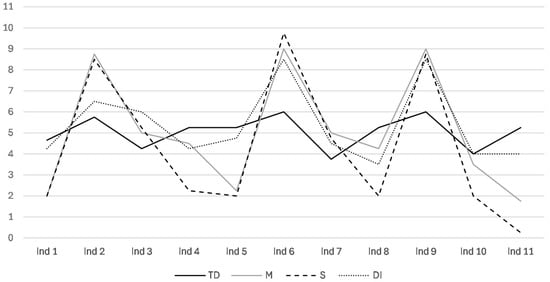

Four Revit media channel types were evaluated: text documentation (TD), modeling (M), simulation (S), and data integration (DI). Table 5 summarizes the importance/effectiveness ranking of the Revit media channel in supporting LEED EA indicators as assessed by the experts. Figure 6, on the other hand, presents a line chart of the data in Table 5.

Table 5.

Effectiveness of Revit media channels in supporting LEED EA indicators as assessed by the Experts’ Panel.

Figure 6.

Effectiveness of Revit media channels in supporting LEED EA indicators as assessed by the Experts’ Panel. (TD: text documentation, M: modeling, S: simulation, and DI: data integration).

3.5. Association Between Revit Media Channels and the Support for EA Indicator

Kendall’s Tau (τ) correlation analysis was conducted to examine whether there is a statistically significant association between Revit’s level of support for LEED EA indicators (measured by Q2 of the survey) and the type of Revit’s media channel (DI, M, S, TD). The values of Q2 measure are used rather than that of Q1 because Kendall’s Tau works best with ordinal data. Kendall’s Tau was chosen due to its robustness to tied ranks, which are frequent in Likert-type scales. The results of Kendall’s Tau analysis are presented in Table 6. The results revealed significant differences in the perceived effectiveness of the four evaluated media channels, that is; modeling (M), simulation (S), data integration (DI), and text documentation (TD).

Table 6.

Correlation between Revit’s media channels and the level of support in achieving LEED criteria and requirements.

4. Findings and Discussion

This study examined the extent to which Autodesk Revit, as a BIM tool, supports and automates the calculation of energy-related criteria as defined by LEED requirements. The major findings are discussed below.

4.1. Revit’s Support for LEED EA Indicators

The results of examining the level of Revit’s support for LEED EA criteria are presented in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 and Figure 4 and Figure 5. The findings demonstrated that Revit provided diverse levels of alignment with and support for LEED’s EA indicators.

Highly and moderately supported indicators. As shown in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4, six out of 11 (63.6%) indicators are evaluated as highly supported by Revit (mean support score ≥ 5.5), while one indicator is moderately supported. The mean support score for highly supported indicators ranges between 5.5 and 7 (out of 7). The highly supported indicators by Revit are minimum energy performance, building-level energy metering, optimized energy performance, advanced energy metering, renewable energy production, and enhanced refrigerant management. These indicators were consistently evaluated as highly supported on both Q1 measure (objective measure of achieved points) and Q2 measure (subjective assessment on the Likert-scale). These indicators received mean scores of 6.56, 5.78, 7.0, 6.3, 6.71, and 5.43 out of 7 for achieved points (Q1) and mean scores of 6.88, 5.75, 7.0, 6.25, 6.88, and 5.5 out of 7 for the perceived level of support (Q2), respectively.

The findings, as presented in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4, also revealed that Revit provides moderate support for one indicator, the fundamental refrigerant management, which received a score of 5.0 (out of 7) for achieved points (Q1 measure) and 5.38 for perceived support level (Q2 measure), which reflects some level of disagreement on Revit’s capacity to provide high support for refrigerant management. The aggregate score for the level of support of the fundamental refrigerant management indicator (on both Q1 and Q2 measures) is about 5.18 (out of 7), which is very close to the lower bound of the highly supported range (i.e., 5.5); thus, one may consider that highly supported indicators are 7 indicators.

The seven indicators evaluated as highly supported by Revit span over a range of key energy-related areas. Three of these core indicators (minimum energy performance, building-level energy metering, and fundamental refrigerant management) are prerequisite indicators, which means they must be fully achieved before even considering a project for LEED certification. The other four are complex and performance-intensive indicators that are assigned high weight (22 out of 33 points assigned for energy-related indicators). This result means that Revit is evaluated as effective in supporting most prerequisite indicators (3 out of 4) and a set of credit indicators that weigh 22 out of 33 total points. This finding provides empirical evidence of BIM’s capacity to play a major role in supporting and automating LEED energy-related criteria.

Poorly Supported Indicators. As presented in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4, the findings show that the remaining four indicators (i.e., fundamental commissioning and verification, enhanced commissioning, demand response, green power, and carbon offsets) are rated as poorly supported by Revit (mean support score < 3). Across the two survey rounds, these indicators were evaluated consistently as poorly supported by Revit, with mean support scores ranging from 0.0 to 0.96 (out of 7) for achieved points (Q1) and from 1.0 to 2.0 for perceived level of support (Q2). The low support ratings of these indicators, accompanied by consensus among experts as evidenced by low IQR values, highlight the limited capacity of Revit to meet the requirements of these indicators. These indicators typically require environmental impact and procedural tracking capabilities, which are outside Revit’s primary modeling and simulation functionalities. The finding regarding highly and poorly supported indicators are aligned with prior research on BIM support for green certification, which highlights that BIM is strongest in analytical, model-based criteria and weakest in documentation- or management-intensive indicators [41,42,43]. These studies suggest that BIM-based energy workflows can streamline LEED energy modeling and automate point calculations for performance-intensive indicators.

4.2. Expert Consensus on Revit Support for LEED Indicators

In addition to investigating the level of Revit support for each indicator, the study also examined the level of agreement/consensus among the expert panel regarding this issue to provide more insights into the level of BIM alignment with and support for GBA criteria. This study has used mean scores along with the interquartile range (IQR) to assess the degree of consensus among the experts. As shown in Table 4 and depicted in Figure 5, the findings show that there is a consensus/agreement among experts regarding Revit’s level of support for 73% (8 out of 11) of the indicators. Although the findings reveal that 7 out of 11 LEED EA indicators were evaluated as highly supported (mean support score ≥ 5.5), the expert panel has reached consensus/agreement (IQR ≤ 1 and mean score ≥ 5.5) on only five of them, which are minimum energy performance, building-level energy metering, optimized energy performance, advanced energy metering, and renewable energy production, while there is no agreement (IQR > 1 and mean score ≥ 5.5) reached on the other two indicators (i.e., fundamental refrigerant management and enhanced refrigerant management). On the other hand, out of the remaining four indicators that were evaluated as poorly supported by Revit (mean support score < 3), there was consensus (IQR ≤ 1 and mean < 3) on three of them, which are fundamental commissioning and verification, enhanced commissioning, and green power and carbon offsets, while no agreement (IQR > 1 and mean < 3) was reached on the ‘demand response’ indicator. The lack of consensus/agreement among experts regarding 3 indicators (2 highly supported indicators and 1 poorly supported) highlights the need for further investigation using more rigorous and specialized research methods, such as the Delphi approach, to explore the level of agreement on this issue and the reasons behind it. It also may suggest a need for further enhancements in Revit’s functionalities. Here, it is worth mentioning that, as shown in Figure 5, the objective measures (evaluating and counting achieved points) resulted in more consensus among panel members compared to subjective measures (perceived support level), where in the first case, the panel reached agreement on 9 indicators (out of 11) compared to agreeing on 7 indicators in the second case.

4.3. Importance and Effectiveness of Revit Media Channels

The results of examining the role of the various media channels within Revit in supporting and facilitating LEED criteria are presented in Table 5 and Figure 6. The results reveal significant differences in the effectiveness of Revit’s various media channels in supporting the calculation of LEED EA indicators. As shown in Table 5 and Figure 6, the findings show that modeling (M) and simulation (S), followed by data integration (DI) received the highest importance rankings regarding their role in supporting LEED EA criteria. This importance is mainly associated with specific complex and performance-intensive EA indicators such as minimum energy performance, optimize energy performance, and renewable energy production. The importance of the modeling channel is rated 8.75 (out of 10) for minimum energy performance, and 9.0 for both optimize energy performance and renewable energy production, while the simulation channel importance is rated 8.5, 9.75 and 8.75, and data integration is rated 6.5, 8.5 and 8.5 for the same indicators, respectively. These high importance ratings, accompanied by expert consensus, suggest that modeling (M) and simulation (S) capabilities of Revit play a major role in facilitating and supporting energy-related criteria. Data integration (DI) comes after modeling and simulation and plays a moderate role, particularly in cases where different and incompatible data types are used. On the other hand, text documentation (TD) received the lowest rank. These results are closely aligned with findings in existing research, which positions BIM primarily as a performance-simulation and data-integration system. Several studies [6,7,42,43] emphasize that BIM’s value in green building certification lies in its ability to integrate geometric, thermal, and material properties to support energy simulation and performance optimization. Our results—showing strong correlations between modeling/simulation channels and LEED EA support—provide empirical, indicator-level validation of this claim.

Kendall’s Tau correlation analysis, as shown in Table 6, confirmed these observations statistically. The results of Kendall’s Tau analysis reveal a strong positive correlation between the expert-rated importance of the modeling (M) and simulation (S) channels and the level of Revit’s support for LEED indicators (τ = 0.835, p = 0.001) and (τ = 0.768, p = 0.002), respectively. This suggests that modeling and simulation media play a major role in supporting and automating the calculation of LEED EA criteria. Results also revealed a moderate-to-strong positive correlation between the data integration (DI) channel and the level of Revit’s support for the indicators (τ = 0.549, p = 0.025), which suggests a moderate role in facilitating LEED EA certification criteria. The expert’s feedback highlighted the importance of integrating a wide range of engineering data with different formats within one platform in increasing the efficiency of calculating and preparing the required green building requirements. In a very fragmented field like the building and construction industry, where several stakeholders with diverse needs and expectations interact and work together, data integration is a very crucial aspect. The results reveal that the integrated computational functionalities within Revit (i.e., modeling, simulation, and data integration) are evaluated as more impactful in green certification workflows compared to traditional alternative procedures that utilize standalone, task-specific software to calculate and achieve the required green building objectives and criteria. On the other hand, the results indicate that no statistically significant correlation was observed for text documentation (TD) (p > 0.25), which highlights its limited role in automating and supporting the assessment of LEED EA requirements. Although these results demonstrate that Revit is able to support a wide range of LEED EA criteria and requirements, they also suggest that this support still faces a range of limitations and constraints. It is worth mentioning here that the feasibility of using BIM to support and automate green building certification to a large degree depends on the level of BIM adoption and the ability to seamlessly integrate BIM with existing working processes and existing systems in the building industry.

5. Conclusion and Further Work

The built environment, particularly residential buildings, consumes a significant quantity of energy and raw materials and produces large amounts of carbon emissions and waste materials, which significantly raise the environmental footprint impact of buildings. These impacts are expected to further increase in the future as a result of the continuous and rapid increase in urbanization. One alternative solution to overcome this current and future environmental challenge is to develop high-performing green buildings. This paper provides quasi-empirical validation of the role of BIM—specifically Autodesk Revit—in supporting and automating the calculation of energy-related criteria in the LEED green residential building certification process.

The results reveal that Revit is capable of effectively supporting 7 out of 11 LEED EA indicators, with mean support scores ranging between 5.18 and 7 (out of 7). In both survey rounds, six indicators (i.e., minimum energy performance, building-level energy metering, optimized energy performance, advanced energy metering, renewable energy production, and enhanced refrigerant management) were evaluated as highly supported by Revit, while the fundamental refrigerant management indicator was evaluated as moderately supported with a score close to the lower bound of the highly supported range (i.e., 5.5). The seven highly supported key energy indicators include three prerequisite indicators and four key performance-intensive energy-related indicators with high weight. In other words, this result shows that Revit is evaluated as effective in supporting most of the prerequisite indicators (3 out of 4) and a set of credit indicators that weigh 22 out of 33 total points assigned for the EA category. On the other hand, the results demonstrated that four indicators (i.e., fundamental commissioning and verification, enhanced commissioning, demand response, green power, and carbon offsets) were evaluated as poorly supported by Revit on both rounds of the survey. These results may indicate that either Revit modules need to be enhanced to better integrate GBA tool demands, or LEED requirements may need further transformation to enable GBA support. The strength of these results comes from the fact that these results were consistent throughout the two rounds of the survey and that the experts reached a consensus/agreement regarding Revit’s level of support for 73% (8 out of 11) of the indicators. Lack of consensus/agreement among experts appeared in three indicators (2 highly supported indicators and one poorly supported), which suggests the need for further investigation using more rigorous and specialized research methods.

Findings also show that modeling, simulation, and data integration are the most impactful channels in terms of supporting LEED compliance, with significant statistical correlation confirmed through Kendall’s Tau correlation. Findings showed that these three Revit channels were reliably used to streamline LEED requirements. Text-based documentation, on the other hand, was the least correlated with supporting GBA requirements. The results suggest that the integration of several media channels and computational functionalities such as modeling, simulation, and data integration within one platform increases significantly the efficiency of Revit as a BIM tool to support and calculate the requirements of most indicators and the compilation of the needed/required green building documentation. However, these results also suggest that there is a need for further development and improvement to enhance Revit’s computational functionalities and its capabilities to optimize LEED certification outcomes. By shedding light on the nuanced intersection between BIM functionality and green building certification, this study contributes to the evolving dialogue on parametric design and its contribution to green design, highlighting capabilities, limitations, and implications for practicing professionals.

The study also demonstrated that the adopted multi-method approach to assess the ability of BIM tools to support green building practices is a viable one, as it provides a range of qualitative and quantitative measures. This study is limited to residential buildings in the Saudi context. Potential improvement areas for future studies include conducting comparative studies across different BIM platforms and GBA tools; comparing the performance of various BIM tools and functionalities; and investigating the challenges associated with the ability of BIM tools to generate the set of documentations required to be submitted for green certification of other building types, including time, cost, data exchange, incompatibility and integration challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.-Q. and A.O.; methodology, A.O.; software, A.O.; validation, J.A.-Q., A.O. and Z.A.; formal analysis, A.O.; investigation, A.O.; resources, A.O.; data curation, A.O.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.-Q.; writing—review and editing, A.O. and Z.A.; visualization, A.O.; supervision, J.A.-Q.; funding acquisition, J.A.-Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals—KFUPM] grant number [INCB2527] and the APC was funded by [King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals—KFUPM].

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to funding restrictions and that the project is still in progress.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge with appreciation the necessary support provided by the Interdisciplinary Research Center for Construction and Building Materials (IRC-CBM) at King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals (KFUPM), Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, under Project No. INCB2527.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdel-Hamid, M.; Abdelhaleem, H.M.; Abd El-Razek Fathy, A.E. Assessing the implementation of BIM for enhancing green building certification evaluations. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Masood, R. Assessment of Sustainable Building Design with Green Star Rating Using BIM. Energies 2025, 18, 3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qawasmi, J. Selecting a contextualized set of urban quality of life indicators: Results of a Delphi consensus procedure. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsehrawy, A.; Amoudi, O.; Tong, M.; Callaghan, N. A review of the challenges to integrating BIM and building sustainability assessment. AIP Conf. Proc. 2021, 2428, 020005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyanya, D.; Paulillo, A.; Fiorini, S.; Lettieri, P. Evaluating sustainable building assessment systems: A comparative analysis of GBRS and WBLCA. Front. Built Environ. 2025, 11, 1550733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun Solomon, A.; Akila Agnes, S.; Sridhar, J. A BIM-enabled life cycle approach to evaluate global warming potential and embodied carbon in building materials. Eng. Res. Express 2025, 7, 045118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balo, F.; Sagbansua, L.; Boydak, H. Toward a Greener Building Envelope: Analyzing Sustainable Cladding Materials through BIM for Energy Efficiency. J. Build. Mater. Sci. 2024, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berges-Alvarez, I.; Martínez-Rocamora, A.; Marrero, M. A Systematic Review of BIM-Based Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment for Buildings. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolognesi, C.; Bassorizzi, D.; Balin, S.; Manfredi, V. An Overview on LCA Integration in BIM: Tools, Applications, and Future Trends. Digital 2025, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Feng, K.; Wang, Y. The Application of Building Information Modeling in Sustainable Construction: A Literature Review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Construction and Real Estate Management 2018; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2018; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gallardo, S. A Multi-Objective Optimization Method for the Design of a Sustainable House in Ecuador by Assessing LCC and LCEI. Sustainability 2024, 16, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornely, K.; Ascensão, G.; Ferreira, V.M. A Case Study on Integrating an Eco-Design Tool into the Construction Decision-Making Process. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula, N.; Jyo, L.K.; Melhado, S.B. Sources of Challenges for Sustainability in the Building Design—The Relationship between Designers and Clients. Buildings 2022, 12, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Antwi-Afari, M.F.; Anwer, S.; Chen, Z.S.; Li, H. A state-of-the-art review of digital twin-enabled human-robot collaboration in smart energy management systems. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazal, I.; Monna, S. Green building progress assessment: Analysis of registered and certified buildings for LEED rating system. An-Najah Univ. J. Res.-A (Nat. Sci.) 2024, 38, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollberg, A.; Genova, G.; Habert, G. Evaluation of BIM-based LCA results for building design. Autom. Constr. 2020, 109, 102972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.C.; Sandford, B.A. The Delphi technique: Making sense of consensus. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2007, 12, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Jalaei, F.; Jrade, A. Integrating building information modeling (BIM) and LEED system at the design stage of sustainable buildings. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2015, 18, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Mwambegele, B.; Abraham, A.; Basheer, S.; Garia, S. A comprehensive review on building information modelling (BIM), its implementations and applications. Discover Civ. Eng. 2025, 2, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.M.; Tariq, M.A.; Alam, Z.; Alaloul, W.S.; Waqar, A. Optimizing energy efficiency through building orientation and building information modelling (BIM) in diverse terrains: A case study in Pakistan. Energy 2024, 311, 133307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kineber, A.F.; Othman, I.; Famakin, I.O.; Oke, A.E.; Hamed, M.M.; Olayemi, T.M. Challenges to the Implementation of Building Information Modeling (BIM) for Sustainable Construction Projects. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Maurya, K.K.; Mandal, S.K.; Mir, B.A.; Nurdiawati, A.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Life Cycle Assessment in the Early Design Phase of Buildings: Strategies, Tools, and Future Directions. Buildings 2025, 15, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.-W.; Seghier, T.; Ahmad, M.; Leng, P.; Mat Yasir, A.; Abdul Rahman, N.; Chan, W.L.; Mahdzar, S. Green Building Design and Assessment with Computational BIM: The Workflow and Case Study. In Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Design, Construction and Operations IV; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2021; Volume 205, pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; Ma, M.; He, Y.; Wang, B. From Energy Efficiency to Carbon Neutrality: A Global Bibliometric Review of Energy Conservation and Emission Reduction in Building Stock. Buildings 2025, 15, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, L.; Kiroff, L. BIM Use in Green Building Certification Processes. In Proceedings of International Structural Engineering and Construction; ISEC Press: Fargo, ND, USA, 2023; Volume 10, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Motalebi, M.; Rashidi, A.; Nasiri, M.M. Optimization and BIM-based lifecycle assessment integration for energy efficiency retrofit of buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 49, 104022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, M.K.; De Araujo, L.O.C.; Oladimeji, O.; Khalas, M.; Figueiredo, K.V.; Boer, D.; Soares, C.A.P.; Haddad, A. Influence of Ventilation Openings on the Energy Efficiency of Metal Frame Modular Constructions in Brazil Using BIM. Eng 2023, 4, 1635–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Adhikari, S. Bridging the Gap: Enhancing BIM Education for Sustainable Design Through Integrated Curriculum and Student Perception Analysis. Computers 2025, 14, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numan, M.; Saadat, E.U.; Farooq, M. BIM and Sustainable Design: A Review of Strategies and Tools for Green Building Practices. J. Eng. Res. Sci. 2024, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olu-Ajayi, R.; Alaka, H.; Egwim, C.; Grishikashvili, K. Comprehensive Analysis of Influencing Factors on Building Energy Performance and Strategic Insights for Sustainable Development: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, L.; Badarch, T. Exploration of Revit Software Aided Architectural Design Education Based on Computer BIM Technology. Am. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2022, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raouf, A.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Framework to Evaluate Quality Performance of Green Building Delivery: Project Brief and Design Stage. Buildings 2021, 11, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskin, M.S. The Delphi Study in Field Instruction Revisited: Expert Consensus on Issues and Research Priorities. J. Soc. Work Educ. 1994, 30, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayens, M.K.; Hahn, E.J. Building Consensus Using the Policy Delphi Method. Policy Politics Nurs. Pract. 2000, 1, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.-S.; Park, C.-S. A Study on the LEED Energy Simulation Process Using BIM. Sustainability 2016, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, M.; Hu, A.; Alshehri, A.; Waqar, A.; Khan, A.; Bageis, A.; Elaraki, Y.; Ali, A.; Shohan, A.; Benjeddou, O.; et al. BIM-driven energy simulation and optimization for net-zero tall buildings. Front. Built Environ. 2024, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, E.; Elwakil, E. Optimizing building energy performance using BIM and climate-driven site data. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2025, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyis, S. BIM-based energy analysis and design tools in support of LEED v4 certification for residential projects. Bursa Uludağ Univ. J. Fac. Eng. 2021, 26, 985–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Sherko, R. BIM Based Design Optimization Framework for the Energy Efficient Buildings Design in Turkey. Tamap J. Eng. 2018, 2018, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirovasilis, E.; Katafygiotou, M.; Psathiti, C. Comparative Assessment of LEED, BREEAM, and WELL: Advancing Sustainable Built Environments. Energies 2025, 18, 4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USGBC (U.S. Green Building Council). LEED Reference Guide for Building Design and Construction, v4; USGBC: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- von der Gracht, H.A. Consensus measurement in Delphi studies: Review and implications for future quality assurance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2012, 79, 1525–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahhaj, A.; Asif, M. BIM-based techno-economic assessment of energy retrofitting residential buildings in hot humid climate. Energy Build. 2020, 227, 110406. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.