Abstract

This study presents a machine learning framework for predicting the axial compressive strength of circular concrete-filled steel tube (CFST) columns subjected to concentric and eccentrically applied axial loads. A harmonized database of 1287 test specimens was compiled, encompassing diverse material strengths, geometric configurations, and eccentricity levels. Among the trained models, the CatBoost (CatB) algorithm exhibited the highest predictive performance. A 300-run Monte Carlo simulation yielded a mean R2 of 0.966 (Min: 0.804; Max: 0.996), with a mean RMSE of 588.8 kN and MAPE of 8.36%, demonstrating accuracy and robustness across repeated randomized splits. Comparative benchmarking against current design equations revealed that CatBoost substantially reduced prediction scatter, improving the mean ratio and reducing the COV from 70–75% (ACI/AIJ/Wang) to 5.43%, while maintaining a nearly unbiased mean prediction ratio of 1.00. In addition, inverse prediction models based on CatBoost achieved test-set R2 values of 0.908 for compressive strength and 0.945, 0.900, and 0.816 for key design parameters (D, t, L), indicating promising capability for supporting preliminary sizing and parameter selection. The outcomes of this study highlight the potential of data-driven modelling to complement existing design provisions and assist engineers in early-stage decision-making for axially loaded circular CFST columns.

1. Introduction

Concrete-filled steel tube (CFST) columns merge the benefits of steel and concrete, emerging as a favored solution in construction and transportation sectors. These composite structures have been extensively analysed through experimental and theoretical research, highlighting their superior strength, ductility, and energy absorption capabilities compared to their steel and reinforced concrete (RC) counterparts [1,2]. The utilisation of CFST columns in landmark projects, such as Taipei 101, Two Union Square, the Shimizu High-rise Building, KK100, and the Alipay Headquarters, underscores their growing acceptance for both high-rise and large-scale constructions [3,4].

CFST columns combine steel’s lateral support with concrete’s resistance to local buckling, achieving a balance of the constituent materials’ benefits [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Circular CFST columns are preferred for their optimal confinement capabilities and structural aesthetics among various cross-sectional shapes, making them a prominent choice in engineering designs [12].

Predicting axial compressive strength is essential for safely designing structural elements like building columns and bridge piers. Pioneering studies in the 1970s by Furlong [13], Gardner and Jacobson [14], and Knowles and Park [15] initiated the exploration of CFST columns’ axial load behaviour through both laboratory experiments and finite element analysis. Subsequent research has expanded on these foundations, examining various dimensions, material strengths, and cross-sectional shapes and proposing experimental formulas to predict axial compression capacity [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25].

Most current models in current standards are derived through regression analysis with predefined formula forms and adjustable coefficients. Although these models show good fit within specific experimental result ranges (e.g., size and material type), especially for models used to develop guidelines, their accuracy in different ranges remains questionable [26]. For example, both the European code EC4 [27] and the British code BS5400 [28] limit the use of concrete compressive strength to no more than 50 MPa, while this limit is slightly increased to 70 MPa under the American code AISC 360-16 [29] and the Chinese code GB 50936 [30]. Japanese code AIJ [31] and the Australian/New Zealand code ASNZS 2327 [32] are the only two codes that allow high-strength concrete with compressive strengths up to 90 MPa and 100 MPa, respectively. However, these limits are far below the current development of high-strength concrete with compressive strengths up to 200 MPa [33]. In high-rise building construction applications, high-strength materials can reduce the cross-sectional size significantly, even to half that of normal-strength materials [34,35,36,37].

Machine learning (ML) has transformed civil engineering practices, enabling new approaches to analysis and prediction. In the field of civil engineering, ML is increasingly applied to modelling and predicting behaviour across various engineering challenges [38,39,40]. Many ML algorithms like random forests (RF), artificial neural networks (ANN), decision trees (DT), support vector machines (SVM), deep learning (DL), and gradient tree boosting models like XGBoost (XGB), CatBoost have been developed and applied for analysing and predicting structural behaviours [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50].

In concrete-filled steel tube (CFST) column research, machine learning (ML) has become an effective tool for prediction and analysis. The ANN-based prediction model proposed by Tran et al. [51] and Naderpour et al. [52] has explored artificial neural networks (ANNs) to predict CFST and fibre-reinforced polymer (FRP) concrete strengths, achieving greater accuracy than conventional regression methods. Further research by Fei et al. [53] and Vu et al. [54] conducted research into support vector regression and gradient reinforcement learning, underscoring the potential of ML in refining CFST column design parameters.

Furthermore, recent studies have continued to advance the understanding of CFST behaviour under diverse conditions and configurations. For example, Naderpour et al. [52] investigated confinement effects and material interaction in high-strength CFST stub and slender columns, while Lyn et al. [53] explored ML-based performance prediction of CFST columns, emphasizing the feasibility of data-driven approaches for design. In addition, Vu Q-V et al. [54] introduced probabilistic ML-based prediction models to evaluate axial capacity uncertainty in CFST systems, and Mirza et al. [55] developed optimized ensemble models for double-skin CFST columns, reflecting the rapid expansion of ML applications in composite steel–concrete structures.

Despite this progress, several significant research gaps remain:

- (1)

- Limited integration of concentric and eccentrically applied axial loading within a unified predictive model.

- (2)

- Scarce investigation into inverse prediction approaches for determining feasible CFST design parameters to achieve a specified axial capacity.

- (3)

- The absence of systematic benchmarking frameworks comparing ML-based models with widely adopted code-based expressions.

- (4)

- A lack of robust validation strategies, such as repeated Monte Carlo simulations to evaluate predictive stability and uncertainty.

Therefore, the objective of this study is to develop a CatB-based machine learning framework using a harmonised database of 1287 circular CFST column tests to predict axial compressive strength under both concentric and eccentric loading. The study further introduces an ML-driven inverse prediction capability to assist preliminary design, performs a systematic benchmarking against code-based analytical models, and incorporates a Monte Carlo-based robustness evaluation to quantify prediction variability and reliability. In addition, the outcomes of this research are translated into a user-friendly web application to facilitate practical access and adoption by engineers.

The specific contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- Development of a harmonised 1287 test database for circular CFST columns covering concentric and eccentric axial loading.

- A CatB-based predictive model providing both forward and inverse prediction capabilities for axial capacity and design parameters.

- A systematic benchmark comparing the ML model to existing code-based analytical expressions.

- Monte Carlo-based robustness evaluation to quantify prediction stability across randomized train-test configurations.

- Development of a web-based application enabling direct engineering use of the proposed predictive framework.

2. Research Methodology

The methodology of this research encompasses several systematic steps, as outlined below:

- Data Collection: This phase involved compiling a comprehensive dataset of 1287 samples of concrete-filled steel tube (CFST) columns, encompassing centrally and eccentrically loaded columns.

- Initial Model Evaluation and Explanation: Utilising the CatBoost model, optimal parameters were identified via the Gaussian Process (GP) optimisation method across 200 iterations. Concurrently, an analysis of SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) values was conducted to examine the impact and significance of input variables on the predicted outcomes.

- Comparative Analysis: The predictive performance of the CatBoost model was benchmarked against other machine learning models and compared with standard and existing regulatory models to validate its reliability and effectiveness.

- Inverse design: Both the CatBoost model and conventional regulatory models were employed to predict the design parameters of CFST columns inversely, showcasing the model’s application in practical engineering contexts.

- Finally, this study involves integrating the developed model into a user-friendly web application.

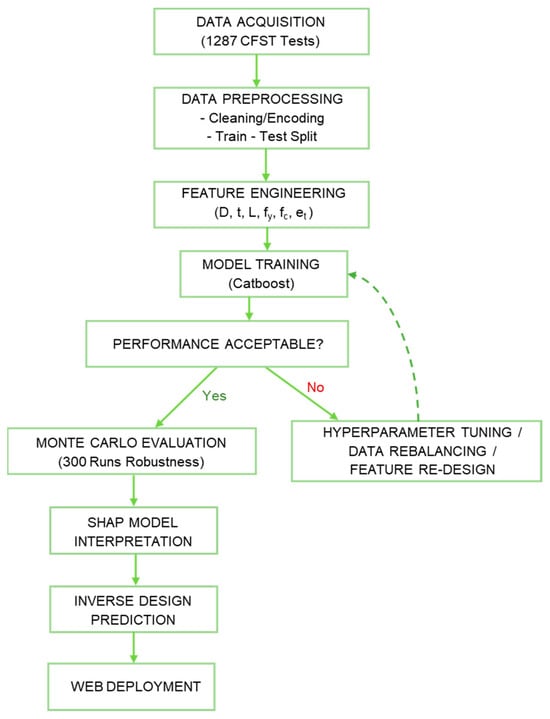

These steps are elaborated upon in detail in Figure 1, providing a visual representation of the research process.

Figure 1.

Research outline.

2.1. Data Collection and Processing

In this study, the dataset was compiled following defined quality control criteria to ensure consistency and comparability of the experimental records. Specimens were included only when uniform axial loading conditions were clearly reported, and compressive strength values could be reliably interpreted. Tests involving non-standard loading configurations, special vibration treatments, or unquantified variations in concrete curing or maturity were excluded to prevent uncertainty in strength normalisation and analytical interpretation. Additionally, incomplete or conflicting records were removed during the screening process.

This approach resulted in a comprehensive dataset comprising 1287 samples, including 425 circular concrete-filled tube (CFT) beam columns and 862 circular CFT columns. The dataset encompasses a broad spectrum of input and output variables, with their respective ranges detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Statistical features of the dataset.

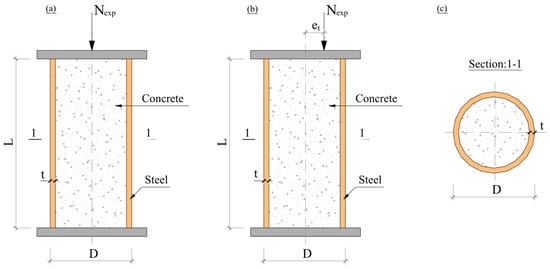

The chosen input parameters for this research include the column diameter (D), steel tube wall thickness (t), column length (L), Yield strength of steel (fy), Compressive strength of concrete (fc), and Eccentricity (et). These parameters were selected due to their recognised significance and well-documented impact on the ultimate bearing capacity, as substantiated in the existing literature. For a visual representation of the selected geometric parameters, refer to Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the CFST columns (a) Front view of Circular CFT columns; (b) Front view of Circular CFT beam-columns; (c) Section type.

In the literature, the compressive strengths of concrete specimens were determined using different testing specimen sizes, including 150 × 150 mm cubes, 100 × 100 mm cubes, and 100 × 200 mm cylinders. Variations in specimen size can lead to inconsistencies in evaluating the ultimate bearing capacity of structural members. To ensure consistency and comparability across studies, all compressive strength values used in this research were standardised to the equivalent strength of a 150 × 300 mm cylindrical specimen, which serves as the unified reference throughout this study.

The equation proposed by L’Hermite [55,56] was applied to convert the strength obtained from 150 × 150 mm cube specimens to the equivalent 150 × 300 mm cylinder strength, as shown in Equation (1):

where fcu and fc represents the standard cube strength and cylinder strength of concrete, respectively, in MPa.

Furthermore, the correlations proposed by Rashid and Mansur [57] were utilised to convert strength measurements obtained from 100 × 200 mm cylinder specimens and 100 × 100 mm cube specimens to the 150 mm standard size before being unified to the 150 × 300 mm cylinder reference, as expressed in Equations (2) and (3):

where and represent the compressive strength of the 100 × 200 mm cylinder specimens and 100 × 100 mm cube specimens, respectively. The converted and standardised concrete strength values were subsequently incorporated into the final database for model development.

fc = 0.96 fc,100

fcu = 0.96 fcu,100

It is acknowledged that these empirical conversion relationships carry inherent uncertainties, typically estimated at ±5–8%, due to variations in aggregate type, curing conditions, and specimen geometry [42]. These correlations were adopted to ensure consistency with established CFST database practices in the literature. The robustness evaluation presented in Section 3.2, based on 300 repeated random data splits, implicitly accounts for data-level variability and confirms stable model performance despite such uncertainties. Future database efforts should prioritize the collection of standardized cylinder strength data where available.

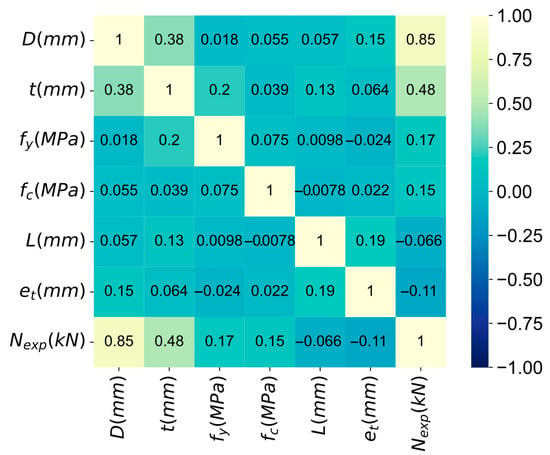

The correlation matrix of six input variables and one output variable is depicted in Figure 3. The correlation matrix shows the pairwise correlation between the variables, which can be positive or negative. A higher correlation value indicates a stronger relationship between two variables. The results indicate that the input variables in the data set are relatively independent, with the highest correlation coefficient of 0.38 observed between steel pipe thickness (t) and CFST column diameter (D). According to the matrix, the variable diameter of the CFST column (D) has the highest positive correlation with the ultimate axial load for the CFST columns. Besides, the linear regression of the axial load of the CFST column against the input parameters is depicted on the graph in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Correlation matrix of the features with the data of 1287 samples.

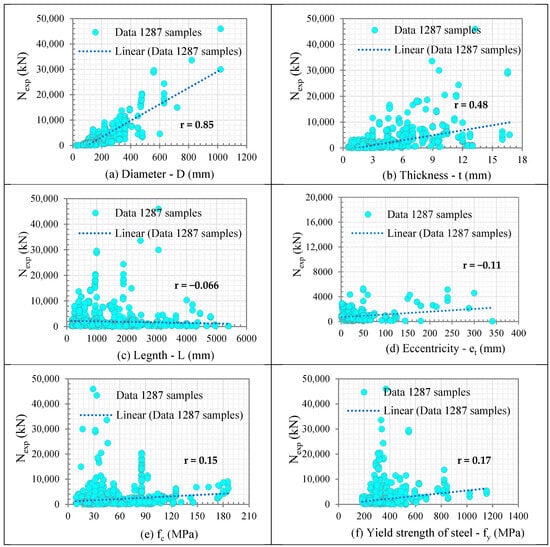

Figure 4.

Linear regression of the axial load of the CFST column against input parameters.

The linear regression graph in Figure 4 describes the correlation between inputs and outputs and the dispersion of samples in the 1287 CFST column data set that was collected and processed. According to observations on the Linear regression graphs of the first six variables with the output variable, the majority of samples converge, corresponding to the value range of Nexp ≤ 10,000 (kN), accounting for 1255 samples out of a total of 1287 samples, especially for the variable eccentricity (et) accounts for most of the column samples with Nexp ≤ 10,000 (kN). In the value range of the ultimate axial load for the CFST columns 10,000 (kN) ≤ Nexp ≤ 20,000 (kN), the samples are distributed relatively more sparsely, corresponding to Nexp ≤ 20,000 (kN); the total number of samples is 1277. Thus, it can be seen that the remaining value range of the ultimate axial load for the CFST columns from 20,000 (kN) to 46,000 (kN) accounts for a relatively small number of samples but covers a relatively wide range of Nexp values.

For this study, “columns” refer to axially loaded CFST members, while “beam-columns” denote specimens subjected to combined axial load and bending. The stub and slender classifications follow widely adopted criteria in CFST research, where members with L/D ≤ 4 are considered stub, those with L/D ≥ 15 are classified as slender, and intermediate values represent transition behavior. The proposed model is intended for use only within the geometric and material ranges represented in the dataset, and extrapolation beyond these limits is not addressed in this work.

2.2. Machine Learning Approach

2.2.1. Models Overview

This study employs tree-based ensemble learning algorithms, which are particularly well-suited for predicting CFST column strength due to their ability to capture nonlinear interactions between geometric parameters (D, t, L) and material properties (fc, fy) without requiring explicit feature engineering. Unlike parametric regression models, ensemble tree methods automatically detect threshold effects and complex parameter dependencies that characterize composite column behavior. Additionally, these methods are inherently robust to features measured on different scales, which is advantageous given the wide ranges of input variables in the compiled database.

In this research, the CatBoost [58] ensemble learning algorithm was employed to develop predictions for the compressive strength of CFST columns, with a focus on its comparative analysis alongside a suite of ensemble learning models such as XGBoost [59], Gradient Boosting Regression (GBRT) [60], and Random Forest (RF) [61]. This section provides an overview of these models and their comparative advantages.

Boosting Methods: Boosting, a technique used for both regression and classification tasks, incrementally builds a model from weak predictors, improving accuracy by assigning them weights to correct errors at each iteration. Gradient boosting, including its variants like XGBoost [59] and CatBoost [58], iteratively adds weak learners to minimise loss functions, enhancing prediction accuracy.

Gradient Boosting (GBRT): This algorithm focuses on creating a series of weak learners, each aiming to correct the predecessor’s errors, thereby incrementally reducing the model’s loss. It is particularly effective for regression and classification problems, producing an ensemble of decision trees to improve prediction performance.

XGBoost [59]: Standing out for its speed and efficiency, XGBoost builds on GBRT but incorporates a regularisation term in its objective function to prevent overfitting, thus maintaining high performance even with complex datasets.

CatBoost [58]: CatBoost distinguishes itself by handling categorical data, offering high accuracy and faster prediction speeds. It iteratively trains learners to minimise loss, using an oblivious tree model and supporting direct input of categorical features, which enhances model applicability.

Random Forest (RF) [61]: A bagging-based approach that constructs multiple decision trees independently and aggregates their predictions. This method reduces overfitting through its random selection of features for splitting, demonstrating robust performance across various datasets.

2.2.2. Model Evaluation

The dataset was divided into training and testing sets, adhering to an 80-20% split to establish a solid foundation for both training the model and evaluating its performance on unseen data. A 10-fold cross-validation method was employed during the training phase to ensure the model’s reliability and predictive accuracy. This process involved dividing the training dataset into 10 equal parts, with the model being trained on nine folds and validated on one, sequentially rotating through all the folds. This ensured each data portion was used once for validation, thereby improving model stability across different data subsets.

Four metrics, including R2, RMSE, MAE, and MAPE, were used to evaluate the performance of the Machine Learning models.

where pj is the axial compressive strength (axial capacity) of the j-th experimental specimen; pt,j is the corresponding predicted axial capacity from the ML model; is the mean experimental axial capacity; n is the total number of samples in the dataset. All variables (Nexp, Npred, Nu) have been standardized and defined with units throughout the manuscript.

2.2.3. Hyperparameters Tuning

Bayesian Optimisation [62] was employed to optimise the hyperparameters of the machine learning models, providing a systematic approach to model optimisation. This method leverages a probabilistic model to map the relationship between hyperparameters and the objective function, aiming to find the objective function’s minimal (or maximal) value with computational efficiency. In the present study, the objective function is represented by the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) value, which Bayesian Optimization seeks to minimise during the optimisation process.

Further, a Gaussian Process (GP) was utilised as a surrogate model to represent the objective function, approximating the distribution over functions to identify regions in the hyperparameter space likely to yield enhanced model performance. The acquisition function, informed by the GP, strategically navigates the search by balancing the exploration of uncertain hyperparameter spaces with the exploitation of known, promising areas. Through iterative selection of hyperparameters that maximise the acquisition function, Bayesian Optimization converges towards optimal hyperparameter configurations while minimising computational cost by reducing the number of evaluations needed to achieve optimal or near-optimal performance metrics. This method proves particularly advantageous for optimising high-dimensional hyperparameter spaces and when the evaluation of the objective function is computationally expensive, thereby ensuring accurate and efficient hyperparameter tuning. Several studies were conducted using this fine-tune hyperparameter technique [63,64,65,66].

2.3. Design Codes for CFST Compressive Strength Prediction

Various methodologies, including standards, design codes, and empirical formulas, predict the ultimate compressive strength of concrete-filled steel tube (CFST) columns. This study utilises prevalent design methods identified from prior research for comparative analysis with machine learning models. Notably, methods from ACI 318-19 [67], Wang et al. [68], Architectural Institute of Japan (AIJ) [69], DBJ 13-51-2010 (Han) [70], Gia et al. [71], and the Chinese code (CH) [72] are incorporated. Table 2 presents the detailed calculation formulas corresponding to these methods, facilitating a comprehensive comparison between traditional design approaches and modern ML-based predictions.

Table 2.

The equations given in current design codes and the equations suggested by different authors.

It should be noted that ACI 318-19 is a reinforced concrete building code and does not include CFST-specific provisions. In this study, the column strength expression from ACI 318-19 is adapted and used solely as a benchmark reference model for comparative purposes, rather than as a dedicated CFST design standard. This approach is consistent with prior CFST research that employs RC-based expressions as conservative lower-bound references. The inherent assumptions—neglecting confinement effects and composite interaction—contribute to the conservative predictions observed when compared against experimental CFST data.

3. Models Evaluations

3.1. Fine-Tuned CatBoost Model Performances

The hyperparameters of the CatBoost model are summarized in Table 3 and were obtained through Bayesian optimization using a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model. The optimization was conducted within predefined search ranges for the key hyperparameters, including tree depth (3–10), learning rate (0.01–0.30), number of iterations (300–1200), L2 regularization coefficient (1–50), bagging temperature (0–1), and random strength (1–20). Uniform priors were adopted for most parameters, while a log-uniform prior was applied to the learning rate to improve exploration at smaller values.

Table 3.

Hyperparameters for the CatBoost model.

The acquisition function minimized the cross-validated RMSE, and early stopping was activated when improvement fell below 0.1% over 20 consecutive iterations. To restrict excessively complex models and mitigate overfitting, constraints were imposed on the maximum depth and minimum learning rate. Under these settings, the GP-based optimization converged after 200 iterations, yielding the final hyperparameter configuration reported in Table 3.

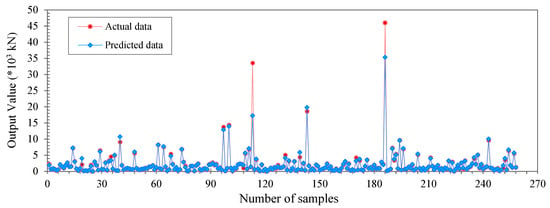

In Figure 4, a comparison is depicted between the observed experimental results and the predicted results produced by the CatBoost model for 20% of the experimental data set, equivalent to 258 samples. The outcomes indicate a substantial agreement between the observed and predicted values.

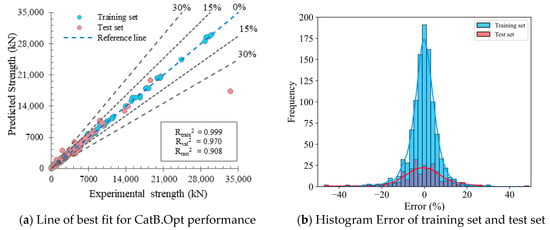

The performance of the CatBoost model is plotted in the form of scatter points in Figure 5 and Figure 6a for both training data (blue color) and test data (red color). Each point represents a unique observation, where the x-axis represents the actual axial load, and the y-axis represents the corresponding predicted values. Points closer to the reference line indicate better predictive performance. Specifically, the predictive capability of the CatBoost model is reflected in the R2/RMSE/MAE/MAPE indices, which are 0.999/92.71/55.61/4.67 and 0.908/1247.71/241.06/9.43 for the training and test sets, respectively. It is important to note that the results presented in this section reflect the performance of the CatB model based on a single hold-out test split after hyperparameter optimisation. A more comprehensive evaluation of model robustness and generalisation capability, including the effects of random train

Figure 5.

Actual and predicted results from the CatBoost model for testing data.

Figure 6.

Predicted performance obtained from the Catboost model for the Training set and the Test set.

Additionally, the histogram plots depicting error distribution for the training and test datasets are illustrated in Figure 6b. Observations indicate that the CatBoost model exhibits high predictive accuracy for both training and test sets, with error distribution concentrated within a 20% range. Notably, there is a high concentration within the 5% error range, peaking at 0% according to the histogram graph.

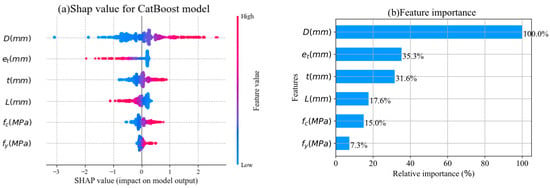

The SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) values technique was employed in conjunction with the CatBoost model to delve into the significance and interplay of input variables affecting the compressive strength of CFST columns. According to the analysis depicted in Figure 7a, an increase in the steel pipe diameter (D), steel tube wall thickness (t), yield strength of steel (fy), and compressive strength of concrete (fc) correlates with an increase in the compressive strength. In contrast, a clear trend for eccentricity (et) and length of the column (L), where an increase correlates with a decrease in compressive strength. In contrast, eccentricity (et) and column length (L) show clear negative correlations with compressive strength. These trends are physically consistent with CFST mechanics: (i) diameter (D) dominates capacity due to the quadratic scaling of cross-sectional area (Ac ∝ D2) and enhanced triaxial confinement in larger circular sections; (ii) tube thickness (t) contributes through direct steel load-carrying capacity and improved hoop confinement of the concrete core; (iii) eccentricity (et) reduces capacity by inducing bending moments that engage only a portion of the section in compression, amplified by second-order P-Δ effects; and (iv) column length (L) negatively influences capacity through increased slenderness and associated stability reductions. These physically meaningful relationships confirm that the CatBoost model has learned fundamental CFST behavior rather than spurious correlations.

Figure 7.

SHAP summary plot and the relative importance of each feature for the CatBoost model.

Simultaneously, Figure 7b shows that the diameter of the steel pipe (D) plays the most critical role and is the dominant input parameter compared to the other five. Second in significance is the eccentricity (et) of the axial load and the thickness of the steel pipe (t). Following these are the length of the steel pipe (L) and the compressive strength of concrete (fc), with the steel strength (fy) being the least influential.

3.2. Performance Comparison: CatBoost vs. Other ML Models

The performance of the CatBoost (CatB) model, along with the proposed optimal parameter set, will be showcased in this section by comparing it with other machine learning models, including XGBoost (XGB), Gradient Boosting (GBRT), and Random Forest (RF). The XGBoost, Gradient Boosting, and Random Forest models were also fine-tuned using the Gaussian Process (GP) method with 200 iterations. The optimal parameters for these three models are detailed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Hyperparameters for XGBoost, Gradient boosting, Random Forest models.

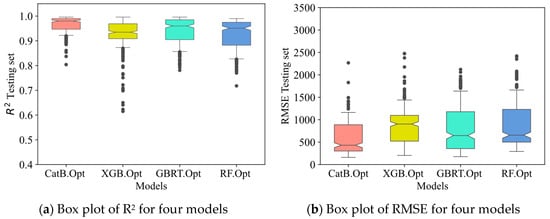

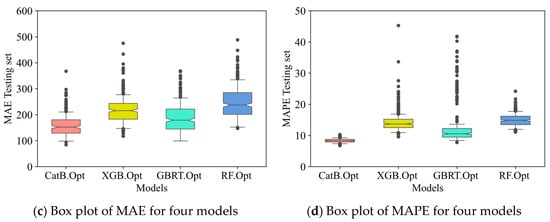

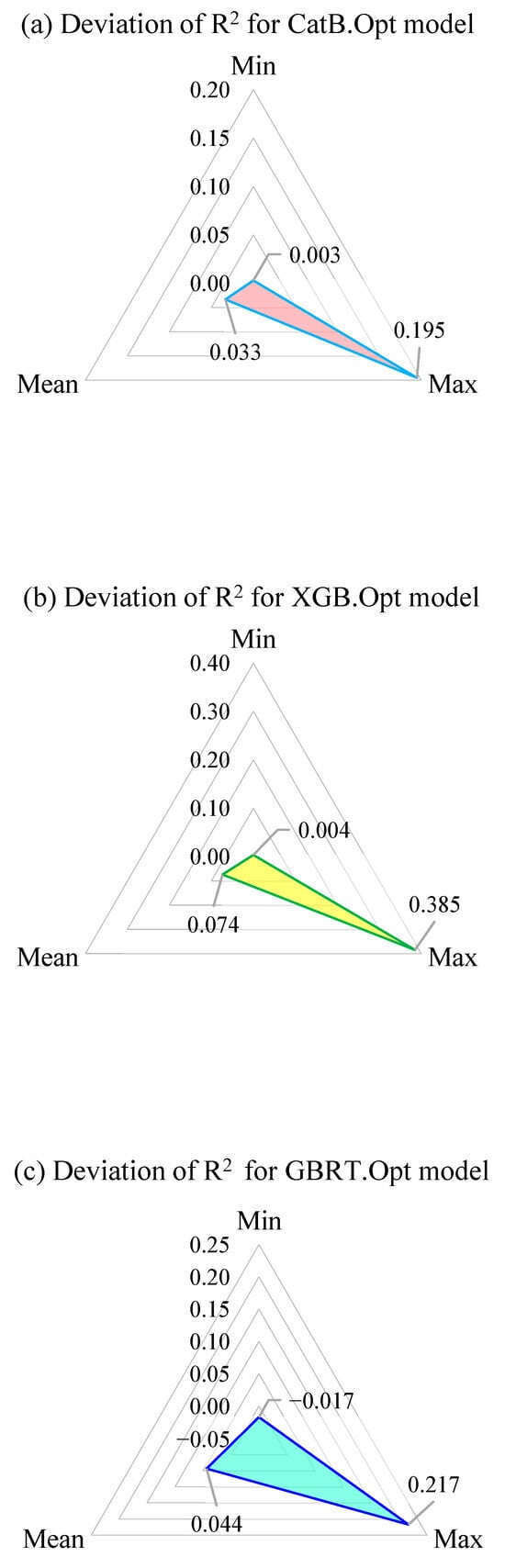

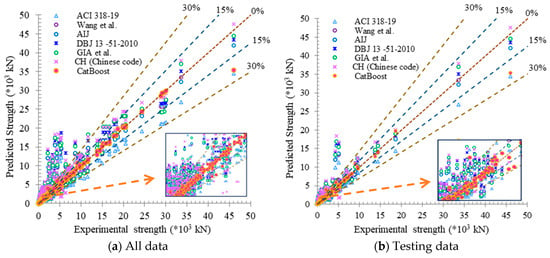

Repeated random sub-sampling validation was employed to assess the predictive stability of the machine learning models. This procedure involves randomly partitioning the dataset into training (80%) and testing (20%) subsets across 300 independent iterations, providing robust estimates of model performance that are independent of any single data split. Four models—CatB, XGB, GBRT, and RF—each with their respective optimized parameter sets, were evaluated on the 1287-sample CFST database, resulting in 1200 total training-testing evaluations. The results of these simulations, encompassing the frequency and convergence of R2, RMSE, MAE, and MAPE indices, are presented in Table 5 and Figure 8.

Table 5.

Prediction results for the testing dataset to evaluate ML model on 300 MCS, using 10 CV.

Figure 8.

The box plot of R2, RMSE, MAE and MAPE of testing set with four model: CatB, XGB, GBRT and RF for 300 simulations.

The Monte Carlo simulation analysis results indicate that the CatBoost model yields the best training outcomes, followed by the XGBoost, GBRT, and finally, the RF model.

Notably, the CatBoost model demonstrates superior learning capabilities when the dataset contains a limited number of samples within the range of feature values. CatBoost exhibits the best and most stable training performance on the dataset of 1287 samples for centrally loaded CFST columns as well as eccentrically loaded ones. Specifically, the CatBoost model achieves R2 values ranging from 0.804 to 0.996, with an average R2 value of 0.966. The RMSE values range from 159.88 kN to 2268.49 kN, with an average of 588.78 kN. The MAE values range from 84.21 kN to 367.36 kN, with an average of 157.53 kN. The MAPE values range from 6.75 to 10.30, with an average of 8.36.

In contrast, the XGBoost model exhibits the lowest R2(min) value and convergence, while the Random Forest model provides the lowest values for RMSE, MAE, and MAPE among the four models. These results suggest that the CatBoost model can perform consistently regardless of the specific training-testing split used. Furthermore, observations indicate that the CatBoost model demonstrates higher generalisation ability compared to the other models.

Additionally, the deviation of R2 − ε (ε = R2train − R2test) over 300 random splits with the optimal hyperparameters for four models: CatBoost, XGBoost, Gradient Boosting, and Random Forest, is illustrated in Figure 9. The findings reveal that both GBRT and RF exhibit instances where εmin < 0, indicating these models are not consistently reliable across various data partitions. This suggests a propensity for overfitting in specific data splits for these models. In contrast, the CatBoost model showcases the most consistent and robust predictive performance for estimating the axial compressive strength of CFST columns among the evaluated models. Specifically, the CatBoost model’s R2 deviation spans 0.003/0.195/0.033 for the minimum, mean, and maximum values, respectively.

Figure 9.

Deviation of R2 over 300 random data sets for models.

3.3. Performance Comparison: CatBoost vs. Analytical Models

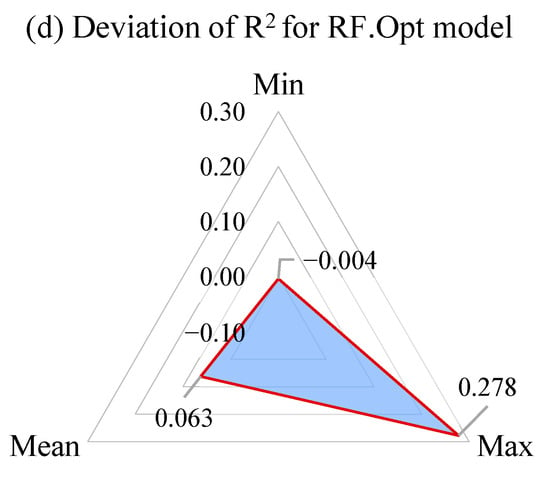

This section presents a comparative evaluation between the predictive capability of the CatB model and six well-established code-based and experimental analytical models for estimating the axial compressive strength of CFST columns. The objective is to assess how effectively the machine learning approach captures the strength behavior relative to traditional design methodologies.

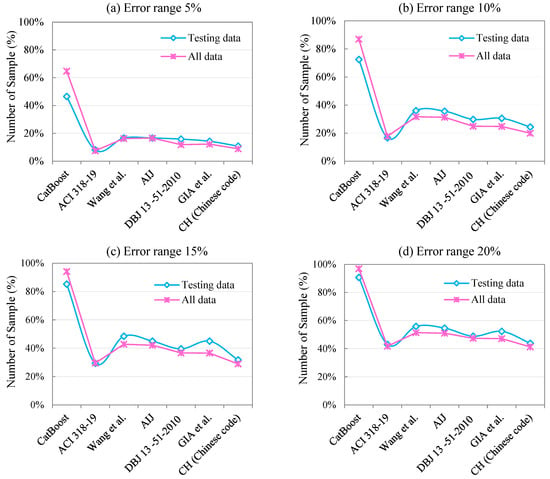

To clarify the scope of comparison, Table 6 reports the performance on the full dataset, providing a consistent and like-for-like basis for comparison, as analytical models do not require model training and are directly applied to all specimens. In contrast, Figure 10b illustrates the prediction results on the test subset, representing the unseen data in the machine learning workflow. This additional comparison emphasizes the generalisation capability of the CatB model and better reflects its potential reliability when deployed for practical design applications.

Table 6.

Performance comparisons between ML model and empirical models.

Figure 10.

Comparison between CatBoost model and the existing equations for testing data [67,68,69,70,71,72].

Simultaneously, it should be acknowledged that the empirical equations listed in Table 2 do not explicitly account for eccentricity or slenderness effects, which contributes to their higher deviation when evaluated against a dataset containing a wide range of loading conditions and member lengths.

The comparative evaluation presented in Table 6 and Figure 10 highlights substantial differences in predictive performance between traditional analytical models and the CatB machine learning model. A key source of variability arises from the fact that each analytical equation was originally calibrated for a limited domain for example, ACI 318-19 for normal-strength concrete and stocky CFST stub columns, AIJ for high-strength concrete but within restricted D/t ranges, and the formulations of Wang et al. and Gia et al. for specific experimental campaigns. In contrast, the present database spans 1287 tests covering a significantly wider spectrum of geometries, D/t ratios, eccentricities, and material strengths. This mismatch in calibration domains partly explains why analytical models exhibit larger deviation and lower goodness-of-fit when applied to the full dataset.

Within this broader and heterogeneous domain, the CatB model demonstrates markedly superior predictive accuracy and stability. CatB achieves a predicted-to-actual strength ratio with a mean of 1.00, a very low COV of 5.43%, and minimal deviation (0.05), reflecting its ability to capture nonlinear interactions across diverse parameter ranges. Among the analytical models, ACI 318-19 shows the closest alignment with experimental values consistent with its conservative calibration objective yet still displays substantially higher dispersion compared to CatB.

The error distribution in Figure 11 further reinforces these findings. At a tight 5% error threshold, CatB reaches accuracies of 46.51% for the test set and 64.80% for the entire dataset. In contrast, ACI 318-19 yields only 8.14% and 7.54%, respectively. Although the empirical formulas of Wang et al. and AIJ perform better than ACI 318-19—doubling its accuracy within the 5% error range they still lag considerably behind CatB across all evaluated thresholds. These results collectively demonstrate that ML-based models, when trained on a harmonised and sufficiently large dataset, offer substantially enhanced predictive capability relative to traditional code-based equations, particularly outside the narrow calibration domains of the latter.

Figure 11.

Distribution of the error range for testing data and all data [67,68,69,70,71,72].

4. Inverse Prediction of Design Parameters of CFST Columns

Inverse prediction leverages a model to determine input parameters—such as column diameter, steel tube wall thickness, column length, steel yield strength, and concrete compressive strength—required to achieve a predetermined target, notably the expected axial compressive strength of CFST columns. This method is critical for design optimisation and informed decision-making, as it allows for the identification of specific conditions or configurations necessary to meet designated performance criteria.

In this study, the CatBoost algorithm is employed for inverse prediction to ascertain the behavior of CFST columns under various conditions to ensure the desired structural integrity. To achieve this, the research involved training and fine-tuning the CatBoost model on six distinct datasets derived from the original dataset of 1287 data points, each corresponding to a different design parameter: diameter, pipe wall thickness, column height, steel strength, concrete strength, and eccentricity.

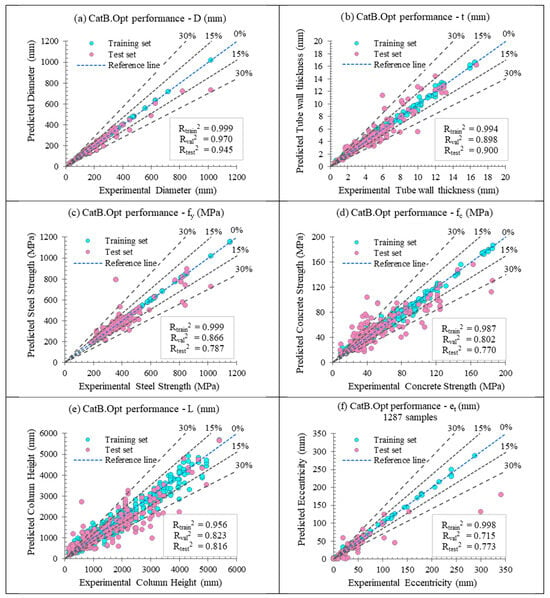

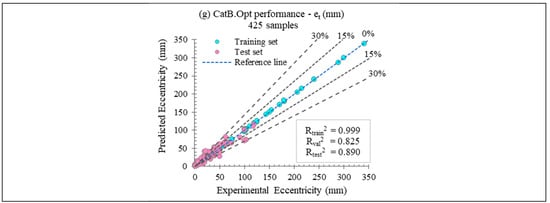

The outcomes of this back-prediction analysis are visually depicted in Figure 12, with the correlation coefficient (R2) for each design parameter detailed in Table 7. Due to the variations in units and scales across the parameters, traditional comparison metrics such as RMSE, MSE, MAE, or MAPE were not applied in the analysis, acknowledging the distinct nature of each parameter’s contribution to the model’s performance.

Figure 12.

CatBoost model performance (R2) of the training set, validation, and test set of backward prediction with database 1287 samples.

Table 7.

Results R2 of the backward prediction of fine-tuned CatBoost models.

Figure 12 illustrates the back prediction performance of the CatB models across six key design parameters. Among these, the column diameter exhibits the highest predictive accuracy, reflected by R2 values of 0.999 for the training set, 0.970 for the validation set, and 0.945 for the test set. Steel tube thickness also performs strongly, with R2 values of 0.994, 0.898, and 0.900 for the training, validation, and test sets, respectively. Predictions of column height, steel strength, and concrete strength demonstrate similarly favorable levels of accuracy, although concrete strength presents the lowest R2 in the test set (approximately 0.77), consistent with its broader variability and weaker correlation to other geometric parameters.

A notable observation concerns eccentricity prediction. When using the full dataset of 1287 specimens, the prediction accuracy is lower due to the highly unbalanced distribution of eccentricity values; over half of the tests report zero eccentricity. To address this imbalance, a separate model was trained exclusively on the 425 eccentrically loaded specimens, yielding substantially improved results (R2 = 0.999, 0.825, and 0.890 for the training, validation, and test sets, respectively). This highlights the importance of targeted model training for parameters with limited variation.

This approach also notably enhances prediction accuracy for column height and steel strength, outperforming previous studies. For example, Nguyen et al. [45] reported considerably lower predictive accuracies, with R2 values of 0.64 and 0.66 for concrete strength and column height. The improved performance achieved in this study underscores the ability of the CatB framework to capture complex nonlinear interactions across a broader and more heterogeneous dataset, reinforcing its suitability for inverse design applications that require simultaneous recovery of geometric and material parameters.

A comparison between the CatBoost inverse predictions and those of existing analytical models are summarized in Table 8. CatBoost demonstrates consistently high accuracy across all parameters, whereas several empirical models show substantial degradation in performance. In particular, some analytical formulas produce negative R2 values during back-prediction (e.g., for tube thickness and steel strength), indicating that they perform worse than a naïve mean-value predictor. This occurs because these equations were originally formulated for forward capacity prediction, not inverse estimation, and lack sensitivity to individual parameter variations. When applied outside their narrow calibration domains, they produce large systematic errors that exceed the variance of the dataset, resulting in R2 < 0.

Table 8.

Back Prediction Performance: CatBoost Models vs. Empirical Formulas.

Overall, the results confirm that the CatBoost-based inverse prediction framework offers significantly higher accuracy, robustness, and generalizability compared with traditional analytical models, making it a reliable tool for preliminary CFST design and parameter identification.

To illustrate the practical application of the inverse prediction framework, consider a design scenario requiring a circular CFST column with target axial capacity Ntarget = 5000 kN under concentric loading. The column length is constrained to L = 3000 mm based on story height requirements.

Step 1: Inverse Prediction Using the trained CatBoost inverse model with inputs Ntarget = 5000 kN and L = 3000 mm, and assuming standard material grades (fy = 345 MPa, fc = 40 MPa), the model predicts:

- Diameter: D = 325 mm

- Tube thickness: t = 8.5 mm

Step 2: Code Verification The predicted parameters are verified against ACI 318-19 (adapted for CFST):

- D/t = 325/8.5 = 38.2 (within typical limits for circular CFST)

- L/D = 3000/325 = 9.2 (intermediate slenderness, acceptable)

- Nu,ACI = 0.85 × 40 × π (325 − 2 × 8.5)2/4 + 345 × π [(325)2 − (325−2 × 8.5)2]/4

- Nu,ACI = 0.85 × 40 × 74,506 + 345 × 8445 = 2533 + 2914 = 5447 kN

The ACI-based estimate (5447 kN) exceeds the target capacity with approximately 9% margin, confirming the feasibility of the inverse-predicted dimensions.

Step 3: Design Refinement The engineer may adjust the design based on practical considerations:

- Round D to standard pipe size: D = 323.9 mm (NPS 12)

- Select standard wall thickness: t = 8.38 mm (Schedule 40)

- Apply appropriate resistance factors per governing code

This example demonstrates that inverse predictions serve as efficient starting points for preliminary sizing, subject to code verification and engineering judgment. The non-uniqueness of the inverse problem—alternative combinations of D, t, and material properties could achieve similar capacity—allows engineers flexibility in optimizing for secondary objectives such as cost, weight, or constructability.

It is important to recognize that the inverse CFST design problem is inherently non-unique: multiple combinations of geometric and material parameters can produce equivalent axial capacities. This characteristic is fundamental to structural design optimization and not specific to the machine learning approach. Engineers should therefore interpret inverse predictions as preliminary design suggestions rather than unique solutions. Recommended practice includes: (i) verifying predictions against applicable design codes (e.g., checking D/t and L/D limits); (ii) considering constructability constraints such as available steel sections and standard concrete grades; (iii) evaluating alternative configurations for cost-effectiveness or architectural requirements. The inverse prediction framework is intended to accelerate the preliminary design phase while retaining the engineer’s judgment in final design selection.

5. Practical Implications

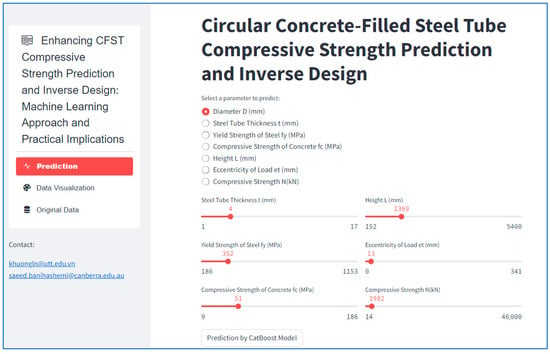

The fine-tuned models, as discussed in the preceding sections, were retrained using the entire dataset and subsequently integrated into a web application designed for predicting the key parameters of concrete-filled steel tube (CFST) columns. This integration of advanced predictive models into an accessible web application optimises the use of complex engineering analyses and promotes innovation, efficiency, and a deeper understanding of CFST column behaviour.

The homepage of the application, illustrated in Figure 13, provides a user-friendly interface that allows users to select an output parameter and input the values for the remaining parameters using intuitive sliders. Powered by sophisticated machine learning models, the application processes these inputs to predict the selected output, simplifying complex computational tasks into a seamless user experience. The complete source code and model may be accessed on GitHub at https://github.com/lekhuong/cfst_columns_ML_prediction. The app was also deployed on Streamlit Cloud: https://cfst-columns-ml-prediction.streamlit.app/.

Figure 13.

User Interface of the Web Application for CFST Compressive Strength Prediction.

This application serves multiple practical purposes:

- Design Optimisation: Engineers can leverage this tool in the early stages of design to swiftly assess the compressive strength of diverse CFST configurations, facilitating the optimisation of dimensions and materials for enhanced performance and cost-efficiency.

- Educational Tool: Enabling students to explore the effects of various parameters on the strength of CFST columns and to witness firsthand the application of machine learning in civil engineering contexts.

6. Conclusions

This study developed a machine learning–based approach for predicting the axial compressive strength of circular CFST columns subjected to concentric and eccentrically applied axial loads. Using a harmonized database of 1287 test specimens, the CatB model demonstrated reliable performance and consistent accuracy across repeated randomized train–test splits. Benchmark comparisons indicate that the proposed approach provides improved prediction capability relative to current design equations for the dataset investigated.

The SHAP-based interpretability analysis revealed that column diameter (D) is the most influential parameter, followed by load eccentricity (et) and tube thickness (t), while column length (L) and material strengths (fc, fy) exhibited moderate influence. This hierarchy is consistent with CFST mechanics, where geometric parameters governing cross-sectional capacity and confinement effects dominate over material properties within typical strength ranges. Practitioners should prioritize accurate specification of diameter and eccentricity when using the predictive framework, as these parameters most significantly affect prediction reliability.

The study also explored the potential of inverse prediction, using the trained model to estimate feasible design parameters for targeting specific axial capacities. While this offers a practical direction for supporting preliminary engineering decisions, the inverse problem is not unique; multiple combinations of geometric and material parameters may produce similar capacities. Therefore, these predictions should be interpreted as design guidance subject to code provisions, structural limitations, and engineering judgment.

A prototype web-based tool was developed to facilitate accessibility and support design evaluation in practice. Future research should expand the model to incorporate additional loading scenarios, non-circular sections, cyclic behavior, and multi-objective design constraints to enhance the applicability of machine learning frameworks to CFST design.

Author Contributions

Software, H.T.T. and K.L.N.; Validation, S.B. and A.A.; Formal analysis, A.A.; Investigation, H.T.T. and K.L.N.; Resources, S.B.; Writing—original draft, H.T.T., K.L.N., S.B. and A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Han, L.; Li, W.; Bjorhovde, R. Developments and advanced applications of concrete-filled steel tubular (CFST) structures: Members. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2014, 100, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.-X.; Wang, W.; Liu, X.-M.; Wang, L.; Sun, Y. Mechanical behavior of outer square inner circular concrete-filled dual steel tubular stub columns. Steel Compos. Struct. 2021, 38, 305–317. [Google Scholar]

- Samarakkody, D.I.; Thambiratnam, D.P.; Chan, T.H.; Moragaspitiya, P.H. Differential axial shortening and its effects in high rise buildings with composite concrete filled tube columns. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 143, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, F.; Goto, Y.; Kawanishi, N.; Xu, Y. Three-dimensional numerical model for seismic analysis of bridge systems with multiple thin-walled partially concrete- filled steel tubular columns. J. Struct. Eng. 2020, 146, 04019164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, Y.; Ebisawa, T.; Lu, X. Local buckling restraining behavior of thin-walled circular CFT columns under seismic loads. J. Struct. Eng. 2014, 140, 04013105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.R.; Wang, W.J.; Ding, F.X.; Liu, X.M.; Fang, C.J. The impact ofstirrupson the composite action of concrete-filled steel tubular stub columns under axial loading. Structures 2021, 30, 786–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Cotsovos, D.M.; Lagaros, N.D. Assessing the Reliability of RC Code Predictions Through the Use of Artificial Neural Networks; CONFAB: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ghumman, A.R.; Pasha, G.A.; Shafiquzzaman, M.; Ahmad, A.; Ahmed, A.; Khan, R.A.; Farooq, R. Simulation of quantity and quality of Saq aquifer using artificial intelligence and hydraulic models. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 5910989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afaq Ahmad, A.A.; Arshid, U.; Elchalakani, M.; Abed, F. Prediction of Columns with GFRP Bars Through Artificial Neural Network and ABAQUS; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 247–255. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, C.F.; Cheema, A.; Qayyum, W.; Ehtisham, R.; Ahmad, A. Detection of Pavement Cracks of UET Taxila Using Pre-Trained Model Resnet 50; CNN: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wahab, S.; Mahmoudabadi, N.S.; Waqas, S.; Herl, N.; Iqbal, M.; Alam, K.; Ahmad, A. Comparative Analysis of Shear Strength Prediction Models for Reinforced Concrete Slab-Column Connections. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2024, 2024, 1784088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Liu, Y.; Lyu, F.; Lu, D.; Chen, J. Cyclic loading tests of stirrup cage confined concrete-filled steel tube columns under high axial pressure. Eng. Struct. 2020, 221, 111048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, R.W. Strength of steel-encased concrete beam columns. J. Struct. Div. 1967, 93, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, N.J.; Jacobson, E.R. Structural behavior of concrete filled steel tubes. J. Proc. 1967, 64, 404–413. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, R.B.; Park, R. Strength of concrete filled steel columns. J. Struct. Div. 1969, 95, 2565–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Usami, T. Strength of concrete-filled thin-walled steel boX columns: Experiment. J. Struct. Eng. 1992, 118, 3036–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeder, C.W.; Cameron, B.; Brown, C.B. Composite action in concrete filled tubes. J. Struct. Eng. 1999, 125, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakino, K.; Nakahara, H.; Morino, S.; Nishiyama, I. Behavior of centrally loaded concrete-filled steel-tube short columns. J. Struct. Eng. 2004, 130, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea, T.; Leon, R.T.; Hajjar, J.F.; Denavit, M.D. Full-scale tests of slender concrete-filled tubes: Axial behavior. J. Struct. Eng. 2013, 139, 1249–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ma, H.; Li, Z.; Tang, Z. Size effect in circular concrete-filled steel tubes with different diameter-to-thickness ratios under axial compression. Eng. Struct. 2017, 151, 554–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Chan, T.M. EXperimental investigation on octagonal concrete filled steel stub columns under uniaxial compression. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2018, 147, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Kotsovos, G.; Cotsovos, D.M.; Lagaros, N.D. Assessing the Load Carrying Capacity of RC Members Through the Use of Artificial Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the HSTAM International Congress on Mechanics, Athens, Greece, 27–30 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Arshid, M.U.; Shabbir, F.; Hussain, J.; Elahi, A.; Ahmed, A.; Tahir, I.K. Assessment of variation in soil parameters, for design of lightly loaded structural foundations. Life Sci. J. 2013, 10, 217–220. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, A.; Arshid, M.U.; Mahmood, T.; Ahmad, N.; Waheed, A.; Safdar, S.S. Knowledge-Based Prediction of Load-Carrying Capacity of RC Flat Slab through Neural Network and FEM. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sayegh, A.T.; Mahmoudabadi, N.S.; Behbehani, L.J.; Saghir, S.; Ahmad, A. Estimating the axial strain of circular short columns confined with CFRP under centric compressive static load using ANN and GRA techniques. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Zhao, Y. Suggested empirical models for the axial capacity of circular CFT stub columns. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2010, 66, 850–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1994-1-1; Eurocode4. Design of Composite Steel and Concrete Structures, Part 1. 1, General Rules and Rules for Buildings. European Committee for Standardization, British Standards Institution: Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- BS5400-5; Steel, Concrete and Composite Bridges. Code of Practice for Design of Composite Bridges. British Standards Institute (BSI): London, UK, 2005.

- AISC 360-16; Specification for Structural Steel Buildings. American Institute of Steel Construction’s: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016.

- GB 50936; Technical Code for Concrete-Filled Steel Tubular Structures. China National Standards: Beijing, China, 2014.

- Architectural Institute of Japan (AIJ). Recommendations for Design and Construction of Concrete Filled Steel Tubular Structures; Architectural Institute of Japan (AIJ): Tokyo, Japan, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- AS/NZS 2327; Composite Structures—Composite Steel-Concrete Construction in Buildings. Standards Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2017.

- Azmee, N.M.; Shafiq, N. Ultra-high performance concrete: From fundamental to applications. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2018, 9, e00197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, J.Y.R.; Xiong, M.; Xiong, D. Design of concrete filled tubular beam-columns with high strength steel and concrete. Structures 2016, 8, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uy, B. Concrete-filled fabricated steel box columns for multistorey buildings: Behaviour and design. Prog. Struct. Mat. Eng. 1998, 1, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, H.-T.; Uy, B.; Khan, M.; Tao, Z.; Mashiri, F. Numerical modelling of concrete-filled steel box columns incorporating high strength materials. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2014, 102, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, F.; Bahrami, A.; Ahmad, I.; Shakouri Mahmoudabadi, N.; Iqbal, M.; Ahmad, A.; Özkılıç, Y.O. Experimental and numerical investigation of construction defects in reinforced concrete corbels. Buildings 2023, 13, 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, Y. Machine learning techniques for civil engineering problems. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 1997, 12, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melhem, H.G.; Nagaraja, S. Machine learning and its application to civil engineering systems. Civil Eng. Syst. 1996, 13, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, J.; Fu, J. Review on application of artificial intelligence in civil engineering. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2019, 121, 845–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Ha, J.; Zokhirova, M.; Moon, H.; Lee, J. Background information of deep learning for structural engineering. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2018, 25, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, H.; Lieu, Q.X.; Lee, J. CNN-based image recognition for topology optimization. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 198, 105887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.T.; Lee, S.; Lee, J. An artificial neural network-differential evolution approach for optimization of bidirectional functionally graded beams. Compos. Struct. 2020, 233, 111517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Zokhirova, M.; Nguyen, T.T.; Lee, J. Effect of hyper-parameters on deep learning networks in structural engineering. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Computational Mechanics (ACOME), Phu Quoc Island, Vietnam, 2–4 August 2017; pp. 537–544. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Lee, S.; Nguyen-Xuan, H.; Lee, J. A novel analysis-prediction approach for geometrically nonlinear problems using group method of data handling. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2019, 354, 506–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, H.; Burgueno, R. Emerging artificial intelligence methods in structural engineering. Eng. Struct. 2018, 171, 170–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghumman, A.R.; Jamaan, M.; Ahmad, A.; Shafiquzzaman, M.; Haider, H.; Al Salamah, I.S.; Ghazaw, Y.M. Simulation of pan-evaporation using penman and hamon equations and artificial intelligence techniques. Water 2021, 13, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.; Mir, J.; Husain, S.S.; Shahid, M.L.U.R.; Ahmad, A. Concrete forensic analysis using deep learning-based coarse aggregate segmentation. Autom. Constr. 2024, 162, 105372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana Ehtisham, W.Q.; Camp, C.V.; Plevris, V.; Mir, J.; Khan, Q.U.Z.; Ahmad, A. Classification of defects in wooden structures using pre-trained models of convolutional neural network. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, W.; Ehtisham, R.; Bahrami, A.; Mir, J.; Khan, Q.U.Z.; Ahmad, A.; Özkılıç, Y.O. Predicting Characteristics of Cracks in Concrete Structure using Convolutional Neural Network and Image Processing. Front. Mater. 2023, 10, 1210543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.-L.; Thai, D.-K.; Kim, S.-E. A new empirical formula for prediction of the axial compression capacity of CCFT columns. Steel Compos. Struct. 2019, 33, 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Naderpour, H.; Kheyroddin, A.; Amiri, G.G. Prediction of FRP-confined compressive strength of concrete using artificial neural networks. Compos. Struct. 2010, 92, 2817–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, F.; Fan, X.; Ding, F.; Chen, Z. Prediction of the axial compressive strength of circular concrete-filled steel tube columns using sine cosine algorithm-support vector regression. Compos. Struct. 2021, 273, 114282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, Q.-V.; Truong, V.-H.; Thai, H.-T. Machine learning-based prediction of CFST columns using gradient tree boosting algorithm. Compos. Struct. 2021, 259, 113505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, S.; Lacroix, E.A. Comparative strength analyses of concrete-encased steel composite columns. J. Struct. Eng. 2004, 130, 1941–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Hermite, R. Idées actuelles sur la technologie du béton. In La Documentation Technique du Batiment et des Travaux Publics; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, M.; Mansur, M.; Paramasivam, P. Correlations between mechanical properties of high-strength concrete. J. Mater. Civil. Eng. 2002, 14, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorogush, A.V.; Ershov, V.; Gulin, A. CatBoost: Gradient boosting with categorical features support. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.11363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD ’16), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoek, J.; Larochelle, H.; Adams, R.P. Practical Bayesian Optimization of Machine Learning Algorithms. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1206.2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, P.I. A Tutorial on Bayesian Optimization. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.02811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Nguyen, K.; Thi Trinh, H.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, H.D. Comparative study on the performance of different machine learning techniques to predict the shear strength of RC deep beams: Model selection and industry implications. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 230, 120649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Nguyen, K.; Trinh, H.T.; Banihashemi, S.; Pham, T.M. Machine learning approaches for lateral strength estimation in squat shear walls: A comparative study and practical implications. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 239, 122458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.L.; Do, T.T.; Nguyen, G.H.; Ahmad, A. Low-Code Application and Practical Implications of Common Machine Learning Models for Predicting Punching Shear Strength of Concrete Reinforced Slabs. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2023, 2023, e8853122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACI 318.19; Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary. ACI Committee 318. American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2022.

- Che, Y.; Wang, Q.L.; Shao, Y.B. Compressive performances of the concrete filled circular CFRP-steel tube (C-CFRP-CFST). Adv. Steel Constr. 2012, 8, 331–358. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.G.; Tao, M.X.; Fan, J.S.; Hajjar, J.F. Comparative study of design procedures for CFST-to-steel girder panel zone shear strength. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2014, 94, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, F.Y.; Han, L.H.; He, S.H. Behavior of CFST short column and beam with initial concrete imperfection: Experiments. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2011, 67, 1922–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giakoumelis, G.; Lam, D. AXial capacity of circular concrete-filled tube columns. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2004, 60, 1049–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB50936-2014; Code for Design of Concrete Filled Steel Tubular Sturtures. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Construction of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2014.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.