Experimental Study on Seismic Performance of Rammed Earth and Rubble Masonry Walls

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Test Overview

2.1. Test Specimen Design

2.2. Test Setup and Loading Regime

3. Primary Test Phenomena and Failure Patterns

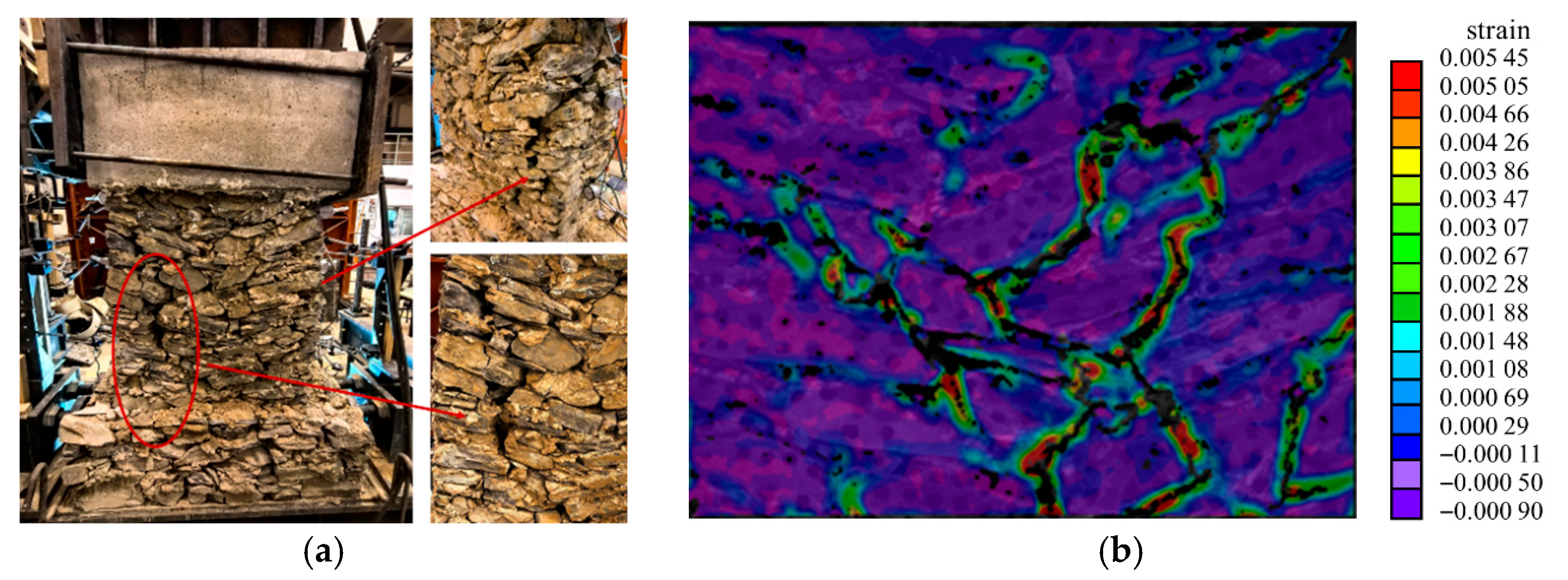

3.1. Formation and Propagation of Microcracks

3.2. Macro Crack Formation and Local Failure

3.3. Failure Stage

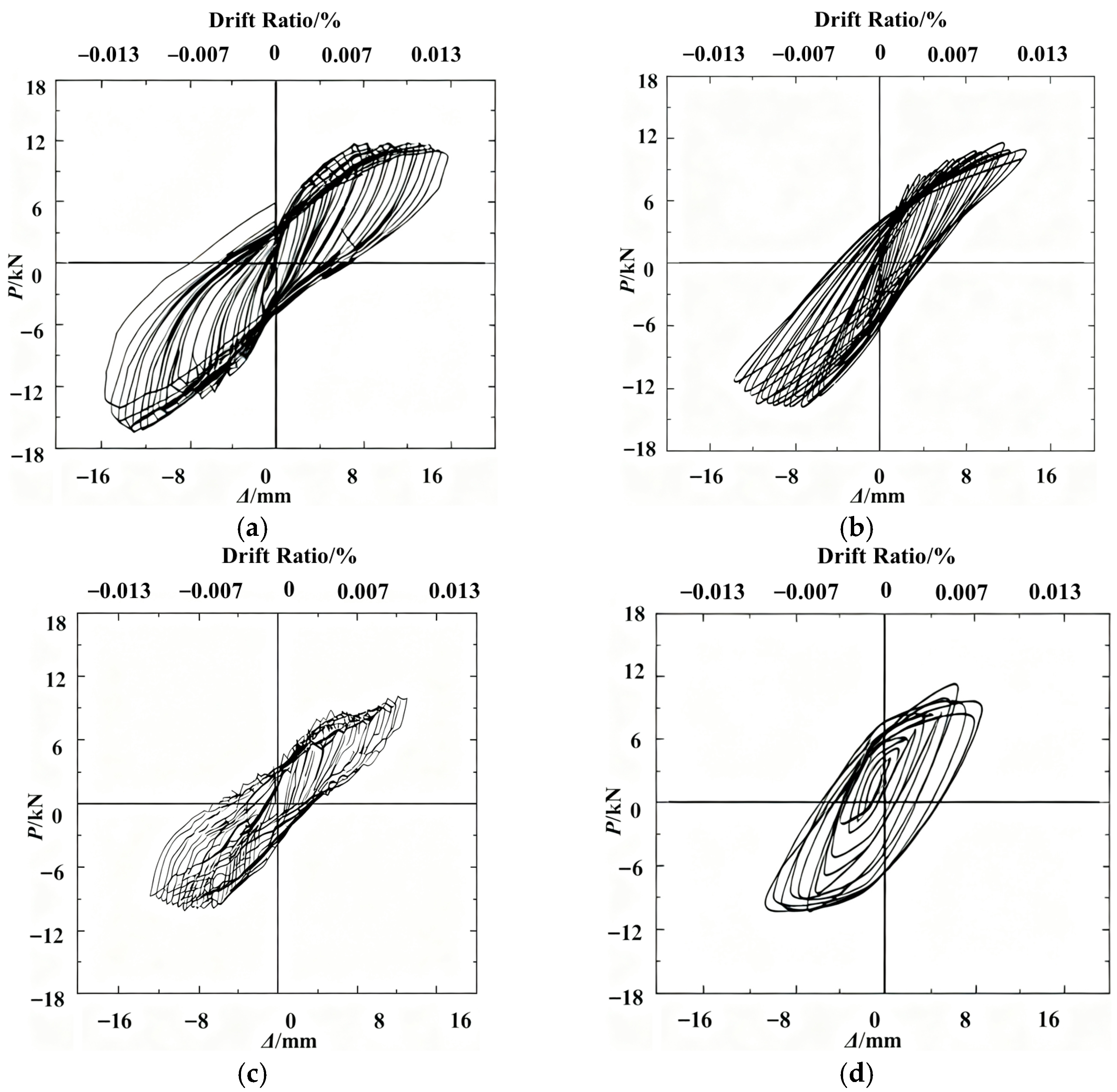

3.4. Hysteresis Curves

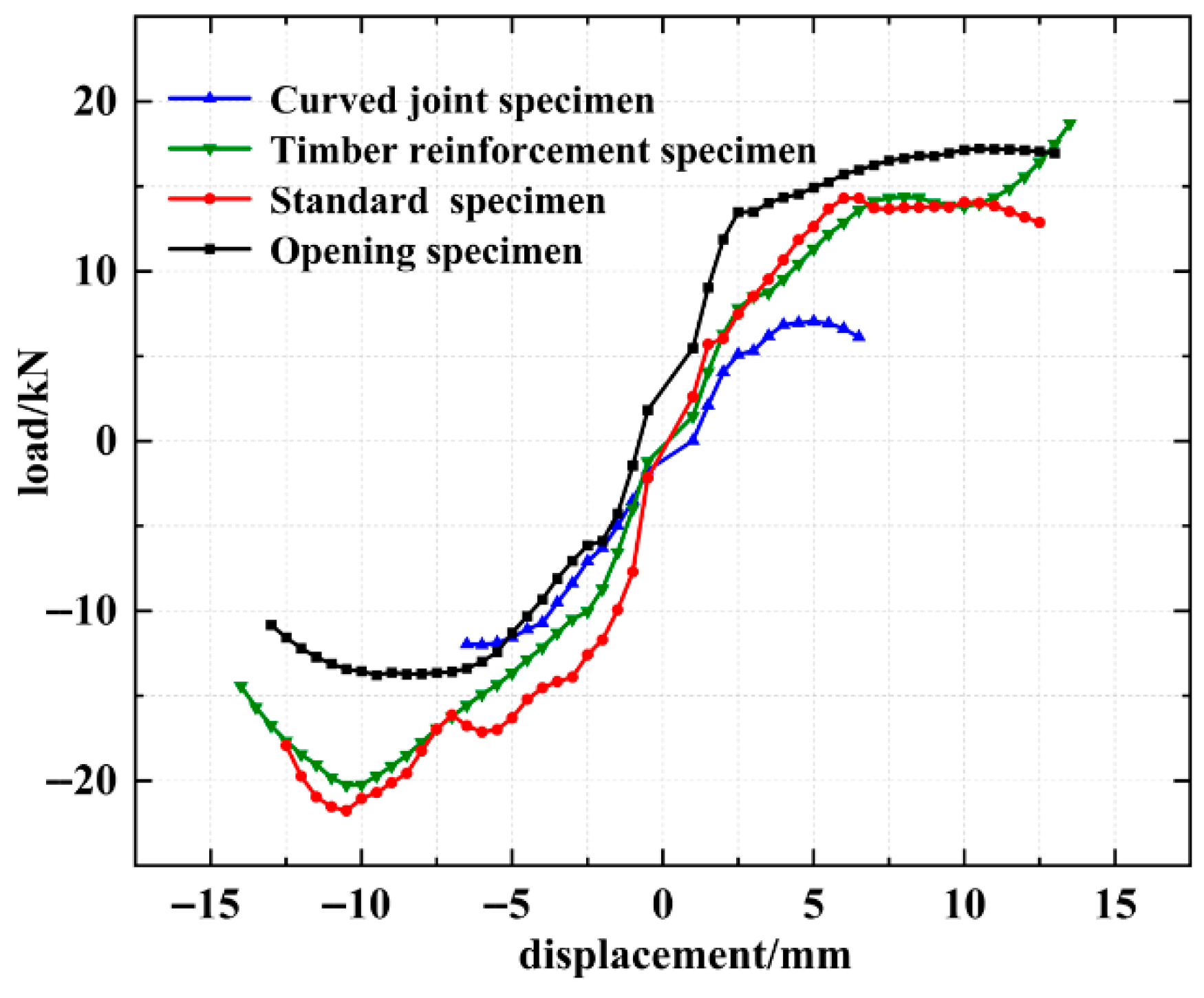

3.5. Skeleton Curves

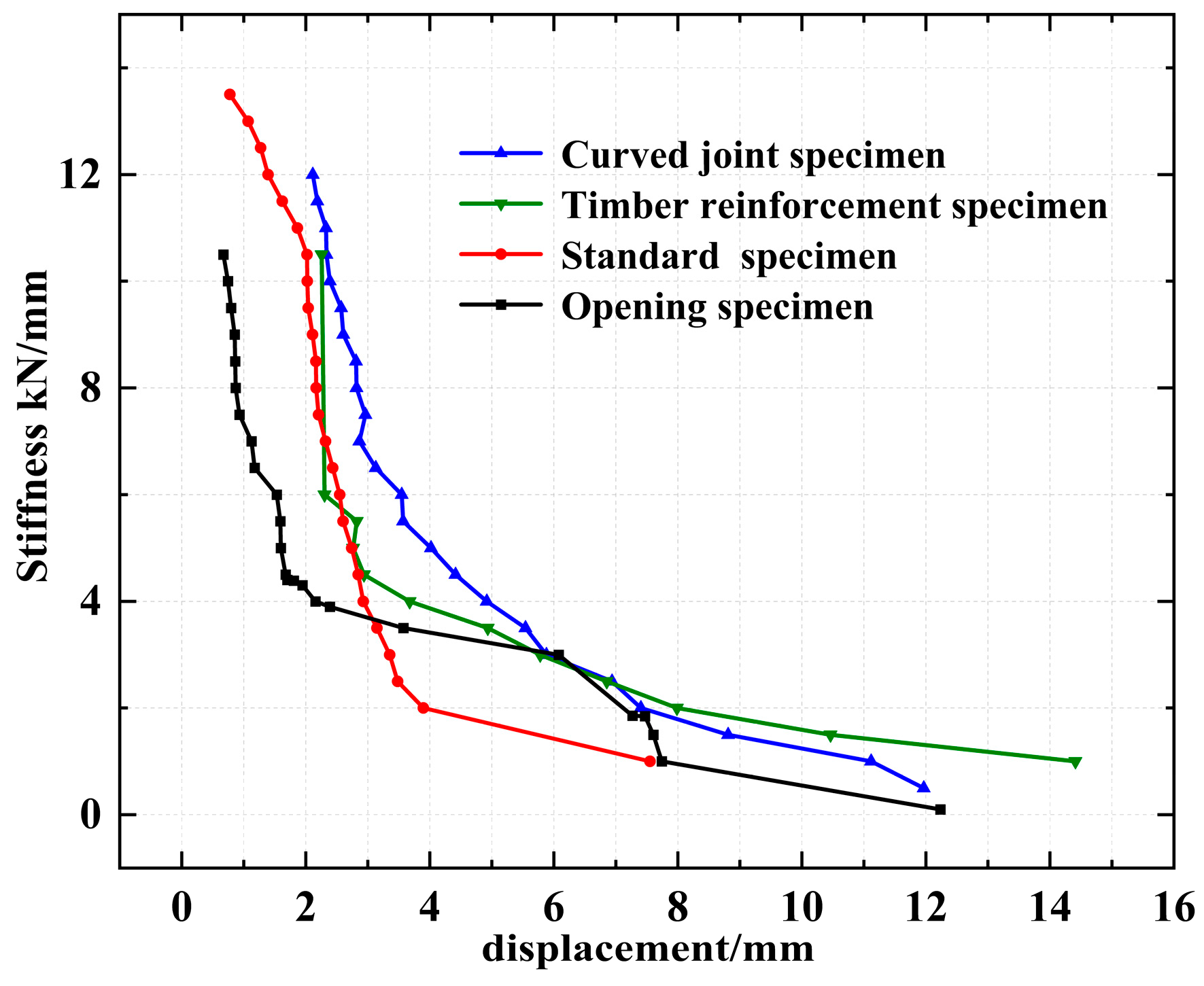

3.6. Stiffness Deterioration Curves

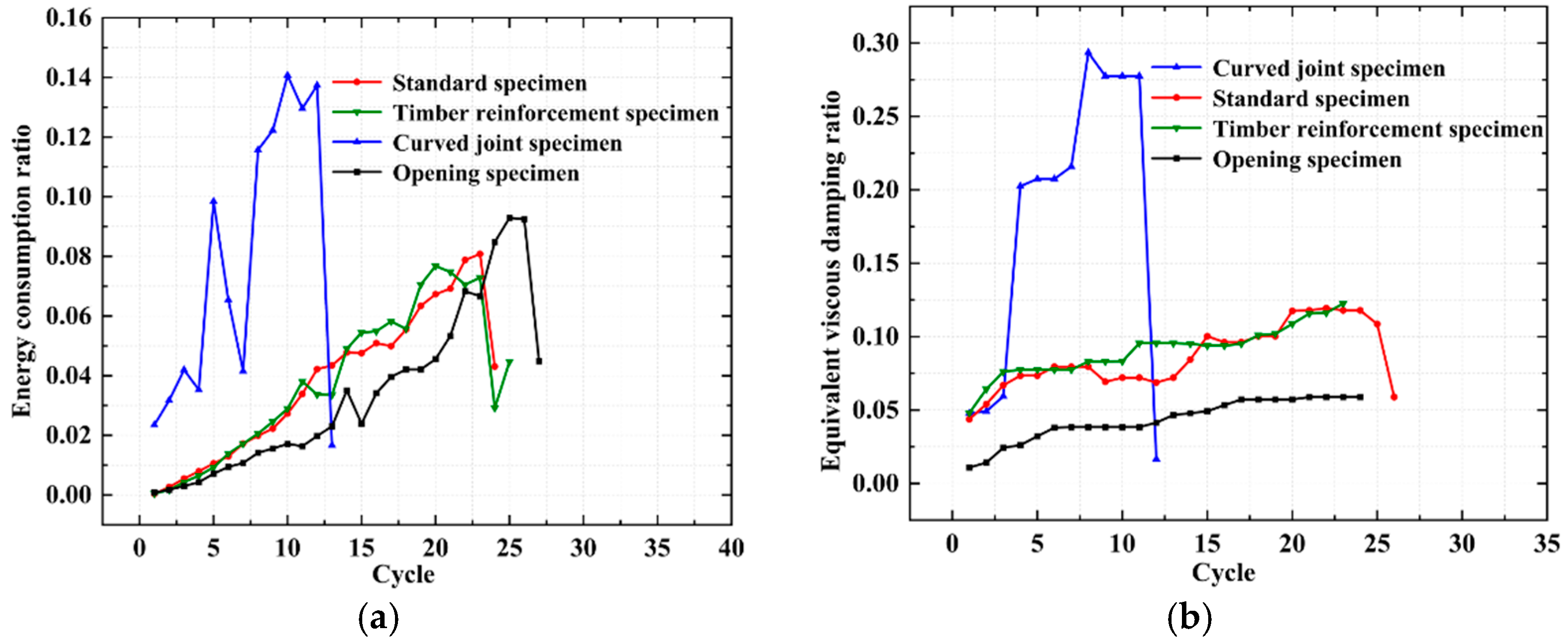

3.7. Energy Dissipation Capacity

4. Shear Capacity of Raw Rammed Earth and Rubble Masonry Wall

5. Discussions

5.1. Analysis of Factors Affecting Testing

5.2. Research Outlook

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The ultimate failure of rammed earth and rubble masonry walls occurs when cumulative damage reaches a critical threshold, leading to final instability failure. Wall failure progresses through three stages: microcrack initiation and propagation, macrocrack formation and local failure, and ultimate failure. However, as damage accumulates, a large through-crack forms in the wall’s midsection, ultimately causing the wall to collapse.

- (2)

- The placement of openings weakens the integrity and load-bearing capacity of rammed earth and rubble masonry walls, reducing their lateral stiffness. Stress concentration is easily induced around openings, particularly at corners, leading to the initiation and propagation of cracks, which results in low deformation resistance. The timber tie-in technique effectively enhances wall integrity and seismic performance, limiting out-of-plane deformation and preventing disintegration during earthquakes. Curved walls exhibit arching effects that improve structural stability. They convert horizontal seismic forces into pressure along the wall’s curved surface, improving overall stability and collapse resistance.

- (3)

- The calculated shear capacity of the opening specimen is 14% lower than that of the standard specimen, and its energy dissipation capacity is slightly lower than that of the standard specimen. As long as the opening area of the wall remains below the corresponding threshold, it will not significantly impact the seismic performance of the wall. The shear capacity of timber-reinforced specimens increased by no more than 5% compared to standard specimens. However, timber reinforcement enhances the wall’s integrity, significantly improving its ductility relative to standard specimens. Walls with curved mortar joints exhibit the most robust hysteresis curves, demonstrating the highest energy dissipation capacity and superior seismic performance. The shear capacity of curved mortar joint specimens increased by 19.8% compared to standard specimens. Correctly setting the curvature radius of curved mortar joints and ensuring high-quality construction can significantly enhance the seismic performance of Tibetan-style rammed earth and rubble masonry walls.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Teng, D.Y.; Yang, N. Research on the features of complete stress-strain curves of Tibetan-style stone masonry under compressive load. Eng. Mech. 2018, 35, 172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.Q. Tibetan Folk House Numerical Simulation Analysis of Seismic Performance. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Petroleum University, Daqing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, M.; Fan, X.M.; Zhou, K.C.; Zhao, W.H.; Liu, Y. Seismic damage simulation and dynamic response inversion of Tibetan dwellings in Dingri County, Xizang, during the MS 6.8 earthquake in January 2025. J. Chengdu Univ. Technol. (Sci. Technol. Ed.) 2025, 52, 185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.X.; Zhao, K.P.; Wang, T.T.; Liu, H.; Li, L. Structural features and seismic performance of Tibet and wellings in Amdo, Northwest Sichuan. World Earthq. Eng. 2022, 38, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, H.; Gao, S.Y.; Jia, B.; Wang, R.H.; Deng, C.L. Seismic performance analysis of Tibetan rubble stone walls based on irregular block geometry indexes. J. Build. Struct. 2022, 43, 200–208. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, X. Study on Compressive Properties of Tibetan Stone Wall. Master’s Thesis, Southwest University of Science and Technology, Mianyang, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, N.; Teng, D. Shear performance of Tibetan stone masonry under shear-compression loading. Eng. Mech. 2020, 37, 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, A.J. Study on Compressive Static Performance of Tibetan Ancient Stone Masonry. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Huang, H.; Wu, Z.H. Research on compressive performance of Tibetan rubble wall based on ANSYS. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Dyn. 2023, 43, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, L.F.; Sun, J.G.; Wang, Z.; Liu, W.; Li, X. Experimental study on earthquake-simulated shaking table test of Tibetan village of No.194 Yang’ fort in Ganbao. Build. Struct. 2018, 48, 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Romanazzi, A.; Oliveira, D.V.; Silva, R.A.; Candeias, P.X.; Costa, A.C.; Carvalho, A. Out-of-plane shake table test of a rammed earth sub-assembly. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 20, 8325–8356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senaldi, I.E.; Guerrini, G.; Comini, P.; Graziotti, F.; Penna, A.; Beyer, K.; Magenes, G. Experimental seismic performance of a half-scale stone masonry building aggregate. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2020, 18, 609–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallioras, S.; Correia, A.A.; Graziotti, F.; Penna, A.; Magenes, G. Collapse shake-table testing of a clay-URM building with chimneys. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2020, 18, 1009–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrini, G.; Senaldi, I.; Graziotti, F.; Magenes, G.; Beyer, K.; Penna, A. Shake-Table Test of a Strengthened Stone Masonry Building Aggregate with Flexible Diaphragms. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2019, 13, 1078–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouris, L.A.S.; Penna, A.; Magenes, G. Dynamic Modification and Damage Propagation of a Two-Storey Full-Scale Masonry Building. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019, 2396452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.B.; Xue, J.Y.; Zhang, F.L. Experimental seismic performance of a reduce-scale stone masonry loess cave with traditional buildings. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 20, 5233–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Hu, P.; Zhang, F.; Zhuge, Y. Seismic behavior of brick cave dwellings: Shake table tests. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 43, 102886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, I.; Penna, A.; DeJong, M.; Butenweg, C.; Correia, A.A.; Candeias, P.X.; Senaldi, I.; Guerrini, G.; Malomo, D.; Beyer, K. Shake table testing of a half-scale stone masonry building aggregate. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 22, 5963–5991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBT 50129-2011; Standard for Test Method of Basic Mechanics Properties of Masonry. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- JGJ/T101-2015; Specification for Seismic Test of Buildings. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015.

- GB 50003-2011; Code for Design of Masonry Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- GB 55007-2021; General Code for Masonry Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Shi, Y.H. Improved Coulomb formula for calculating the shear strength of masonry. Eng. Mech. 1995, 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Chen, S.Y.; Chen, L.; Tao, C.Z.; Gao, X. Beam-type shear resistance model for grouted block masonry. Eng. Mech. 2010, 27, 140–145+151. [Google Scholar]

- Lagomarsino, S.; Cattari, S. Seismic performance of historical masonry structures through pushover and nonlinear dynamic analyses. Geotech. Geol. Earthq. Eng. 2015, 39, 265–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanazzi, A.; Oliveira, D.V.; Silva, R.A.; Barontini, A.; Mendes, N. Performance of rammed earth subjected to in-plane cyclic displacement. Mater. Struct. 2022, 55, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50005-2017; Code for Design of Timber Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Zhang, L.; Cheng, L.; Li, H.Y.; Gao, J.; Yu, C.; Domel, R.; Yang, Y.; Tang, S.; Liu, W.K. Hierarchical deep-learning neural networks: Finite elements and beyond. Comput. Mech. 2021, 67, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Lin, Y. Evolutionary probability density reconstruction of stochastic dynamic responses based on physics-aided deep learning. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 246, 110081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material Type | Material Performance Specifications | Experimental Measured Values |

|---|---|---|

| Stone | Compressive strength | 42.7 MPa |

| Density | 2811 kg·m−3 | |

| Elastic modulus | 2682 MPa | |

| Yellow clay | compressive strength | 0.676 MPa |

| Density | 1388.59 kg·m−3 | |

| Elastic modulus | 120 MPa | |

| Bond strength between yellow clay and stone | Ultimate bond strength | 3.6134 × 10−5 MPa |

| Wall | Ultimate failure load | 577 kN |

| Specimen Type | A (mm2) | δ0 (MPa) | Fcr (kN) | Fu (kN) | V (kN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard specimen | 32,000 | 0.59375 | 13.3324 | 21.27353 | 7.88480 |

| Opening specimen | 23,000 | 0.59375 | 10.14874 | 18.18453 | 5.10048 |

| Curved joint specimen | 32,000 | 0.59375 | 10.8398 | 12.99544 | 9.31801 |

| Timber reinforcement specimen | 32,000 | 0.59375 | 15.6134 | 22.14756 | 7.98492 |

| Specimen Type | Peak Displacements (mm) | Peak Loads (kN) | Stiffness Values (kN/mm) | Energy-Dissipation Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard specimen | 8 | 21.66 | 13.5 | 0.119 |

| Opening specimen | 11 | 18.18 | 10.5 | 0.059 |

| Curved joint specimen | 7 | 12.09 | 12 | 0.293 |

| Timber reinforcement specimen | 14 | 22.14 | 10.5 | 0.123 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Chang, M.; Pei, Z. Experimental Study on Seismic Performance of Rammed Earth and Rubble Masonry Walls. Buildings 2026, 16, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010149

Liu Y, Zhou Z, Chang M, Pei Z. Experimental Study on Seismic Performance of Rammed Earth and Rubble Masonry Walls. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):149. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010149

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yang, Zhenchao Zhou, Ming Chang, and Zuan Pei. 2026. "Experimental Study on Seismic Performance of Rammed Earth and Rubble Masonry Walls" Buildings 16, no. 1: 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010149

APA StyleLiu, Y., Zhou, Z., Chang, M., & Pei, Z. (2026). Experimental Study on Seismic Performance of Rammed Earth and Rubble Masonry Walls. Buildings, 16(1), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010149