External Annular Air Curtain to Mitigate Aerosol Pollutants in Wet-Mix Shotcrete Processes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Materials and Apparatus

2.1.1. Materials

2.1.2. Apparatus

2.2. Experimental Process

2.3. Data Processing

3. Mathematical Models

3.1. Physical Model and Boundary Condition

- (1)

- The concrete aggregates and the aerosol pollutants generated during WMS production are spherical particles;

- (2)

- Ignoring the processes of collision, coalescence, and re-breakage between particles, the volatilization of components in the particles are neglected, and it is assumed that the system is in a steady state;

- (3)

- The heat exchange between the aerosol pollutants and the environment is ignored;

- (4)

- The aerosol pollutant are inert particles, and the motion of these particles in air obeys the three conservation laws of mass, momentum, and energy.

3.2. Mesh Independence and Verification

3.3. Approaches to Data Handling

4. Results and Discussion

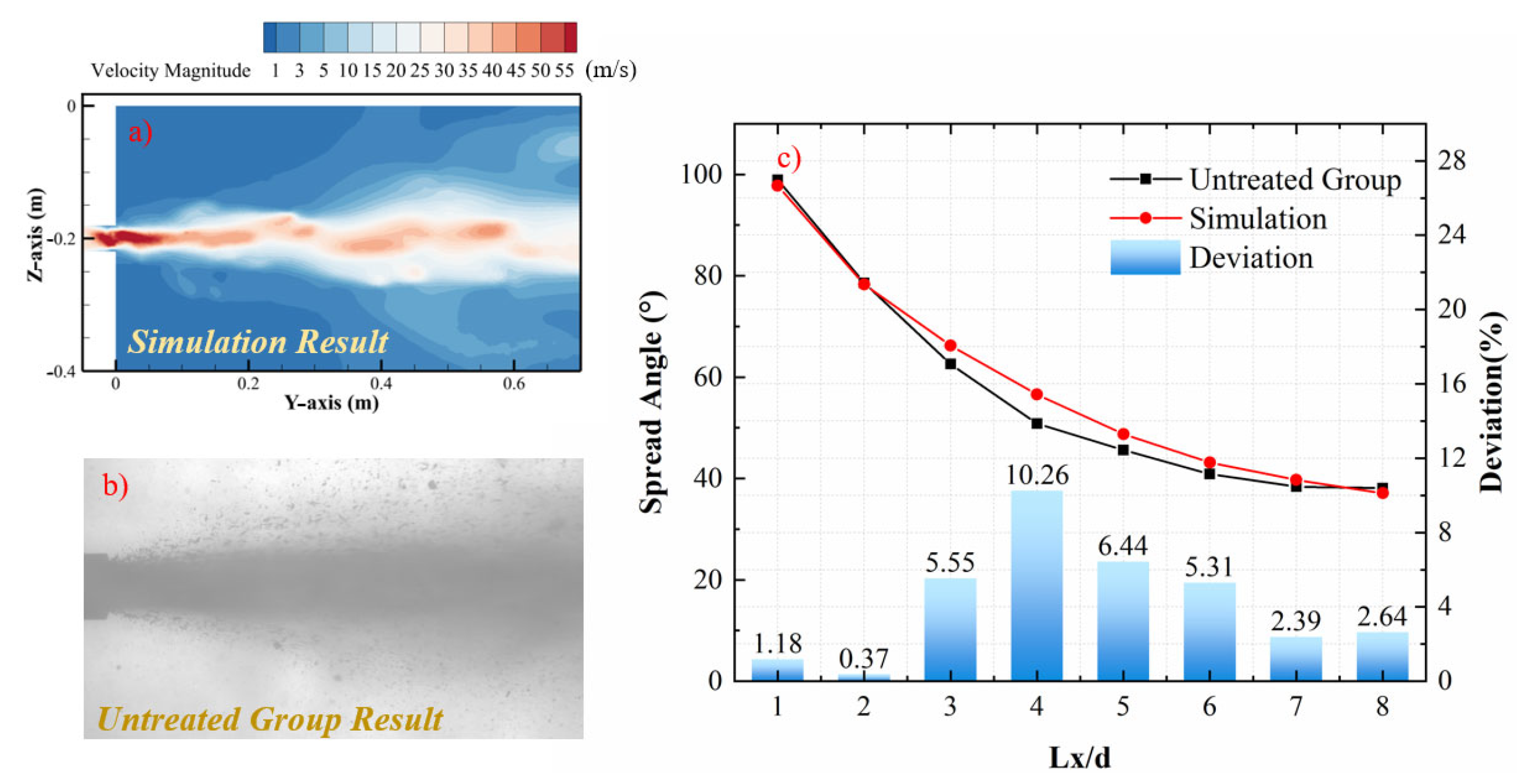

4.1. Evolution of Spread Angle

4.2. Aerosol Pollutant Transport Characteristics

4.3. Characteristic of Flow Field

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The incorporation of an air curtain during the jet aerosol pollutant generation process exhibited three distinct macroscopic effects: reduced aerosol pollutant settling time, decreased aerosol pollutant concentration, and increased average median particle diameter. Through the mutual confirmation of the three parameters, it was demonstrated that the incorporation of an air curtain exhibited encouraging efficacy in suppressing aerosol pollutants during WMS production.

- (2)

- With the incorporation of K-C air curtain (40 m/s), the decrease rate of the jet spread angle reached 52.2%, and the aerosol pollutant control rate reached 57.10%. Meanwhile, the reduction rate in the diffusion phase was 51.92%, demonstrating remarkable effectiveness in aerosol pollutant reduction and control.

- (3)

- The incorporation of K-C air curtain (40 m/s) significantly diminished the velocity gradient between the main jet and ambient air by 33% through momentum mixing, fundamentally inhibiting the energy-driven mechanism of jet breakup and atomization. Additionally, it reconstructed the circumferential flow field, transforming the outward-diffusive velocity profile of free jets into an inward-convergent configuration. The synergistic interplay of these dual mechanisms achieved efficient control over aerosol pollutant generation during the WMS.

- (4)

- This study adopted a combination of experimental and simulation methods to investigate the effects of different air outlet modes and air velocities on dust generation and flow field characteristics during WMS processes. However, it does not fully elucidate the relationships between more annular air curtain parameters and the flow field under varying operating flow rates. Future research could focus on this direction to develop a dust control device design method suitable for wet-mix shotcrete machines, thereby reducing the dust exposure risk for workers during construction operations.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.Q.; Zhang, G.; Tao, Y.C.; Ge, Z.H. The dust pollution characteristic after tunnel blasting and related influence parameters by using experimental method. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 148, 105752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yang, X.E.; Wang, Z.P.; Li, Q.W.; Deng, J. Diffusion characteristics of coal dust associated with different ventilation methods in underground excavation tunnel. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 184, 1177–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.Q.; Du, J.Q.; Chen, J.; Guo, L.W.; Wang, F.S. Dust raising law of gas explosion in a 3D reconstruction real tunnel: Based on ALE-DEM model. Powder Technol. 2024, 434, 119224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhong, H. Experimental and numerical study on airflow-dust migration behavior in an underground cavern group construction for cleaner production. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 144, 105558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Z.; Du, C.F.; Luo, Z.M.; Ding, X.H. Study on starting mechanism and chemical control of road dust under disturbance of automobile tire in open-pit mine. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Armaghani, D.J.; Lai, S.H.; He, X.Z.; Asteris, P.G.; Sheng, D.C. A deep dive into tunnel blasting studies between 2000 and 2023—A systematic review. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 147, 105727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.J.; Zhang, W.; Guo, S.C.; An, H.M. Numerical modelling of blasting dust concentration and particle size distribution during tunnel construction by drilling and blasting. Metals 2022, 12, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.W.; Ruan, C.; Zhao, Z.T.; Huang, C.; Xiao, Y.M.; Zhao, Q.; Lin, J.Q. Effect of ventilation parameters on dust pollution characteristic of drilling operation in a metro tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 132, 104867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.F.; Guo, C.; Song, J.X.; Wang, X.; Cheng, J.H. Occupational health risk assessment based on actual dust exposure in a tunnel construction adopting roadheader in Chongqing, China. Build. Environ. 2019, 165, 106415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.L.; Jiang, Z.A.; Chen, J.W.; Yang, B.; Sun, Y.Q.; Si, M.L.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, F.B.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.H.; et al. Evolutionary mechanism and particle characterization analysis of dust produced by wet-mix shotcrete in tunnels. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, A.; Asadyari, S.; Sahihazar, Z.M.; Hajaghazadeh, M. Monte Carlo-based probabilistic risk assessment for cement workers exposed to heavy metals in cement dust. Environ. Geochem. Health 2023, 45, 5961–5979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.P.; Tian, C.M.; Ye, F.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.Y.; Han, X.B. Reducing Calcium Dissolution in Tunnel Shotcrete: The Impact of Admixtures on Shotcrete Performance. Langmuir 2024, 40, 9911–9925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.M.; Tong, Y.P.; Zhang, J.Y.; Ye, F.; Song, G.F.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, M. Experimental study on mix proportion optimization of anti-calcium dissolution shotcrete for tunnels based on response surface methodology. Undergr. Space 2024, 15, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guler, S.; Öker, B.; Akbulut, Z.F. Workability, strength and toughness properties of different types of fiber-reinforced wet-mix shotcrete. Structures 2021, 31, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.H.; Xiao, L.T.; Zhang, Y.S.; Li, H.Y. Effect of hexadecyltrimethoxysilane modified micro silica particles on workability and compressive strength of ultra-high-performance concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 399, 132480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.H.; Wang, S.; Zhao, J.W.; Guo, Z.; Ou, S.N.; Jin, L.Z.; Cui, J.Y. Understanding aerosol pollutant generation in wet-mix shotcrete for tunnel construction. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 164, 106818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.H.; Wang, S.; Zhao, J.W.; Guo, Z.; Li, K.; Han, X.J.; Jin, L.Z. Optimizing concrete rheology to mitigate aerosol pollutants in wet-mix shotcrete processes. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 36, 103885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.G.; Yan, B.W.; An, X.P. Rheological and flow characteristics of fresh concrete in the rotational rheometer. J. Sustain. Cem.-Based Mater. 2023, 12, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.J.; Li, P.C.; Liu, G.M.; Wang, F. Numerical simulation for optimizing the nozzle of moist-mix shotcrete based on orthogonal test. J. Meas. Eng. 2017, 5, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Cheng, Y.H. Numerical and experimental research on convergence angle of wet sprayer nozzle. Civ. Eng. J. 2018, 4, 1985–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.X.; Islam, M.M.; Zhang, Q. Influence of materials and nozzle geometry on spray and placement behavior of wet-mix shotcrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginouse, N.; Jolin, M.; Bissonnette, B. Effect of equipment on spray velocity distribution in shotcrete applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 70, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginouse, N.; Jolin, M. Experimental and numerical investigation of particle kinematics in shotcrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2014, 26, 06014023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Wu, L.R.; Sun, X.W.; Zhang, J.H. Study on the law of dust isolation by three-dimensional adjustable rotating flow air curtain in fully mechanized mining face. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2025, 262, 106096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Nie, W.; Peng, H.T.; Chen, D.W.; Du, T.; Yang, B.; Niu, W.J. Onboard air curtain dust removal method for longwall mining: Environmental pollution prevention. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Zhang, Y.L.; Guo, L.D.; Zhang, X.; Peng, H.T.; Chen, D.W. Research on airborne air curtain dust control technology and air volume optimization. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 172, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Zhang, Y.L.; Peng, H.T.; Jiang, B.; Guo, L.D.; Zhang, X. Research on the optimal parameters of wind curtain dust control technology based on multi factor disturbance conditions. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.W.; Liu, J.Y.; Liu, J.J.; Li, J.Y. Experimental research on the impact of annular airflow on the spraying flow field: A source control technology of paint mist. Build. Environ. 2021, 207, 108444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.J.; Chen, L.J.; Ma, H.; Ma, G.G.; Li, P.C.; Gao, K. Study on flow characteristics of vertical pneumatic conveying of stiff shotcrete materials based on CFD-DEM. Powder Technol. 2024, 439, 119716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.H.; Ma, C.; Liu, C.; Zhang, K.; Lu, J.; Liu, C.Q. Uniaxial tensile properties of steel fiber-reinforced recycled coarse aggregate shotcrete: Test and constitutive relationship. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.C.; Do, T. Sprayed high-strength strain-hardening cementitious composite: Anisotropic mechanical properties and fiber distribution characteristics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 412, 134862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB2020; The State General Administration of the People’s Republic of China for Quality Supervision and Inspection and Quarantine. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

- JGJ2006; Standard for Technical Requirements and Test Method of Sand and Curshed Stone (or Gravel) for Ordinary Concrete. Ministry of Construction of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2006.

- JGJ2015; Dust Concentration Measuring Instruments, General Administration of Quality Supervision. Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2015.

- GB/T2016; Standard for Test Method of Performance on Ordinary Fresh Concrete. Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Zhang, G.L.; Jiang, Z.A.; Li, X.C.; Chen, Y.; Yang, B.; Si, M.L.; Feng, R.; Wang, M. Impact of high-altitude environments on the motion and settling characteristics of wet-mix shotcrete dust in tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 149, 105807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.W.; Su, X.C.; Bensow, R.; Krajnovic, S. Drag reduction of ship airflow using steady Coanda effect. Ocean Eng. 2022, 266, 113051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | Cement | Fine Aggregate | Coarse Aggregate | Admixture | Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark | 479 | 817 | 817 | 4.31 | 192 |

| Mass ratio | 1.0 | 1.71 | 1.71 | 0.009 | 0.4 |

| Type | Parameter |

|---|---|

| Viscous model | k-ε, standard |

| Multiphase flow model | Volume of fluid (VOF) |

| Inlet_concrete boundary type | Velocity-inlet |

| Inlet_air boundary type | Velocity-inlet |

| Outlet boundary type | Pressure-outlet |

| Hydraulic diameter | 40 mm |

| Time step | 1 × 10−5 s |

| Computational duration | 3 s |

| Dynamic viscosity of concrete | 26.8 Pa·s |

| Groups | Velocity (m/s) | C1 | C2 | C3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (s) | Concentration (mg/m3) | Time (s) | Concentration (mg/m3) | Time (s) | Concentration (mg/m3) | ||

| K-A | 10 | 99 | 55.99 | 267 | 47.20 | 318 | 9.57 |

| 20 | 96 | 53.72 | 234 | 40.34 | 312 | 10.10 | |

| 30 | 96 | 51.65 | 201 | 43.31 | 240 | 14.39 | |

| 40 | 84 | 50.81 | 198 | 44.34 | 228 | 14.43 | |

| K-B | 10 | 93 | 59.32 | 138 | 33.53 | 297 | 7.63 |

| 20 | 66 | 65.93 | 171 | 54.87 | 288 | 10.01 | |

| 30 | 66 | 50.94 | 129 | 47.98 | 279 | 6.47 | |

| 40 | 84 | 52.89 | 132 | 51.24 | 324 | 4.51 | |

| K-C | 10 | 99 | 61.43 | 228 | 48.18 | 261 | 6.90 |

| 20 | 81 | 53.34 | 213 | 41.34 | 282 | 10.37 | |

| 30 | 87 | 43.89 | 180 | 40.17 | 246 | 10.65 | |

| 40 | 75 | 48.62 | 150 | 41.79 | 177 | 6.59 | |

| K-D | 10 | 72 | 60.77 | 210 | 44.55 | 279 | 7.39 |

| 20 | 87 | 50.91 | 165 | 38.94 | 237 | 7.90 | |

| 30 | 87 | 60.27 | 186 | 46.73 | 213 | 6.94 | |

| 40 | 78 | 53.37 | 201 | 40.13 | 228 | 7.89 | |

| Untreated Group | / | 72 | 67.30 | 228 | 45.55 | 369 | 13.53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, K.; Wang, S.; Guo, Z.; Jin, L.; Cui, J. External Annular Air Curtain to Mitigate Aerosol Pollutants in Wet-Mix Shotcrete Processes. Buildings 2026, 16, 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010110

Liu K, Wang S, Guo Z, Jin L, Cui J. External Annular Air Curtain to Mitigate Aerosol Pollutants in Wet-Mix Shotcrete Processes. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):110. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010110

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Kunhua, Shu Wang, Zhen Guo, Longzhe Jin, and Junyong Cui. 2026. "External Annular Air Curtain to Mitigate Aerosol Pollutants in Wet-Mix Shotcrete Processes" Buildings 16, no. 1: 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010110

APA StyleLiu, K., Wang, S., Guo, Z., Jin, L., & Cui, J. (2026). External Annular Air Curtain to Mitigate Aerosol Pollutants in Wet-Mix Shotcrete Processes. Buildings, 16(1), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010110