Abstract

Afghanistan experiences frequent damaging earthquakes, and the widespread use of unreinforced adobe and Pakhsa construction leads to high casualty rates and severe housing losses. Traditional earthen buildings exhibit low tensile capacity, rapid stiffness degradation, and brittle failure, often collapsing at drift levels below 0.5–0.6% or at modest ground motions. Reinforcement techniques evaluated in international experimental studies—such as timber confinement, flexible steel wire mesh, geogrids, and high-quality plastic fencing—have demonstrated measurable improvements, including 30–200% increases in lateral strength, three- to seven-fold increases in ductility, and out-of-plane capacity enhancements of more than two-fold when properly anchored. This study synthesises research findings and global earthen building codes and guidelines to develop a practical, context-appropriate benchmark house model for Afghanistan. The proposed model integrates representative wall geometries, concentrated flat-roof loading, and realistic construction capabilities observed across the country. Three reinforcement alternatives are presented, each designed to be low-cost, compatible with locally available materials, and constructible without specialised equipment. By linking quantitative performance evidence with context-specific construction constraints, the study provides a technically grounded and implementable pathway for improving the seismic safety of rural earthen dwellings in Afghanistan. The proposed benchmark model offers a robust foundation for future national guidelines and for the design and retrofitting of safer, more resilient housing.

1. Introduction

The seismic history of Afghanistan has been documented since the 8th century A.D, although the history of destructive earthquakes in the region exists as far as more than four thousand years ago [1,2]. Afghanistan is located on the southern fringe of the Eurasian plate and its seismicity is mostly due to the northward movements of the Indian plate past eastern and Arabian plate past western Afghanistan with respect to the Eurasian plate. Crustal earthquakes in the country are concentrated at plate boundaries to the east and west of Afghanistan where both the Indian plate and Arabian plate subduct under the Eurasian plate. Mantle earthquakes are mostly concentrated beneath the Hindu Kush and Pamirs. In addition to regional seismicity, the seismic hazard, especially in northeastern Afghanistan, is also influenced by nearby potentially active seismic faults, most of which lack sufficient details for seismic hazard assessments [2,3,4]. These local and regional faults have contributed to triggering strong earthquakes in the past and warn of strong earthquakes in the future.

Civil engineering infrastructure, primarily buildings and houses, often sustains catastrophic damage during earthquakes. In Afghanistan, these devastating consequences stem from the collapse of earthen buildings, mostly houses, which are single- or two-storey buildings made of mud, sun-dried bricks, and stone masonry, with no reinforcement to withstand earthquakes. Only about 25% of the Afghan population lives in cities, of which a small portion lives in engineered buildings, mostly reinforced concrete. The majority of city populations live in non-engineered houses with no means of earthquake resistance. More than 85% of the Afghan population lives in walled houses made of bricks, stone masonry, and mud, which increases the vulnerability of the population and the severity of destruction during major earthquakes.

Over a period of 25 years, from 1998 to 2023, there have been more than 15 significant earthquakes, ranging from Richter magnitudes 5.3 to 7.5, which resulted in over 12,500 deaths, 30,000 injuries, and the destruction of 60,000 homes (Figure 1), leaving 190,000 people homeless (Table 1). It has been reported that almost all these casualties and all this destruction were sustained by the populations living in non-engineered earthen houses [5,6,7]. The aftermath of a strong earthquake that results in thousands of deaths significantly impacts the psychological well-being of survivors, particularly those in mud housing. Grief, anxiety, and feelings of helplessness can overwhelm individuals as they confront loss and destruction. The fear of future earthquakes exacerbates feelings of vulnerability, leading to chronic anxiety and hyper-vigilance. Economic hardship further complicates recovery, as many families lack the resources to rebuild, intensifying despair and hopelessness.

Figure 1.

Earthquake destruction of mud houses (Paktika, Afghanistan, June 2022): (a) out-of-plane collapse of Pakhsa wall, (b) roof collapse, and (c) wall collapse due to large diagonal crack and horizontal cracks at joints between two Pakhsa (monolithic mud wall layer).

Table 1.

Large earthquakes that caused considerable casualties (1998–2023).

Although the damage to earthen buildings is a source of financial loss and causalities during earthquakes, earth/mud is still one of the oldest and most widely used building materials globally, particularly in developing countries such as Afghanistan. It has been reported that 30% to 60% of the global population lives or works in earthen buildings, with a notably higher percentage of the population in developing countries residing in earthen dwellings [20,21,22,23]. In Afghanistan, according to Arya et al. (a) [24], almost 95% of houses were made of earth prior to 2003.

According to Thompson et al. [25], living in earthen houses is not only unavoidable but also desirable, as this building typology embodies cultural values and offers environmental advantages, even though earthquakes are an unavoidable natural phenomenon. Therefore, to mitigate the devastating effects of earthquakes on mud houses, it is essential to construct them with earthquake-resistant designs. The responsibility for ensuring earthquake-resistant construction of earthen buildings primarily falls on the government and technical institutions, which must provide guidelines, raise public awareness, and enforce these standards. However, in Afghanistan, institutions currently lack the necessary capacity and infrastructure for research, development, and enforcement of codes, standards, or guidelines related to earthquake-resistant design and construction of earthen buildings. Consequently, it is crucial to assess how existing reinforcement techniques from other countries can be adapted for use in Afghanistan.

This paper addresses this question by reviewing the literature and relevant earthen building codes and guidelines on seismic strengthening for new and existing earthen buildings. While adobe brick construction is common globally, monolithic mud wall/Pakhsa construction is one of the most common earthen constructions in Afghanistan. Like Arya et al. (a) [24], Foley [26] also reported that 94% of dwellings are made of Pakhsa or mud bricks. Pakhsa construction shares similarities with rammed earth construction, allowing for a review of reinforcement techniques for both adobe and rammed earth to propose strengthening methods for adobe and Pakhsa buildings in Afghanistan. Notably, no research on Afghanistan’s Pakhsa construction is found in the literature.

2. Earthen Construction: Sustainability and Environmental Impact

As noted by Jiménez [27], earthen buildings are sustainable, have low environmental impact, and provide indoor comfort. In Afghanistan, these structures are also vital due to economic, technical, and social factors. While global warming and climate change are critical challenges, the construction sector, as an important contributor, accounts for about one-third of global carbon emissions and nearly 40% of energy use [20,23]. Raw earth is a sustainable material that can be easily sourced locally, minimising embodied energy [21,22].

LaFrance [28] highlighted that CO2 emissions continue to rise, with the IEA projecting a potential doubling by 2050. Thus, reducing energy consumption and carbon emissions in buildings is essential for climate policy, as discussed by Cabeza et al. [29]. While earlier frameworks emphasised operational carbon emissions from lighting and cooling, studies show that embodied carbon from construction materials largely drives overall emission, as demonstrated by [30,31]. According to Kofoworola and Gheewala [32], embodied carbon can be up to 42% of total life cycle emissions.

Cabeza et al. [33] reported that traditional materials like rammed earth, stone, and timber generate the least emissions. According to the authors, earth materials typically range from 0.0 to 0.025 kg CO2/kg, while reinforced concrete ranges from 0.19 to 0.24 kg CO2/kg, and steel averages 2.53 to 2.71 kg CO2/kg. Mud-brick houses have significantly lower carbon intensity compared to reinforced or structural steel. According to Aste et al. [34], thermal efficiency of building envelopes is crucial for reducing overall energy consumption, since the building sector consumes about 32% of global energy, with 37% of that used for heating and cooling [35,36]. Insulating these envelopes can significantly lower energy costs, and unfired clay bricks outperform fired ones in terms of thermal performance as discussed by [37,38]. Bruno et al. [39] as well Indekeu et al. [40] reported that earth walls also provide substantial hygro-thermal inertia, acting as moisture and heat buffers, thereby stabilising indoor humidity and temperature. Additionally, according to Datta and Mustafa [41], raw earth is biodegradable and can be recycled, reducing hazardous waste.

3. Characteristics of Earthen Houses in Afghanistan

Most rural houses in Afghanistan are surrounded by 3 to 5 m high compound walls known as “Qala” (Fort/Castle) covering up to 10,000 square metres for security and privacy and, in addition to the house itself, have spaces for parking, storage, animal shelter, and small gardens. Rooms are constructed along one side inside the Qala to optimise sunlight, with verandas for outdoor gatherings (Figure 2). The architectural design of Afghan mud and brick houses has evolved. Traditionally, these homes had fewer rooms, lower ceilings, narrower doorways, and limited windows, with walls made of mud and straw plaster. They generally lacked electrical and plumbing systems. Contemporary mud houses feature more rooms, taller ceilings, larger windows, and may include amenities, depending on family economics and urban proximity. New constructions may involve engineers or architects, but many remote areas rely on local masons without formal training. Most Afghan earthen buildings can be divided into unfired (adobe) brick houses and layered poured mud (Pakhsa) houses, with Pakhsa houses being more prevalent and larger.

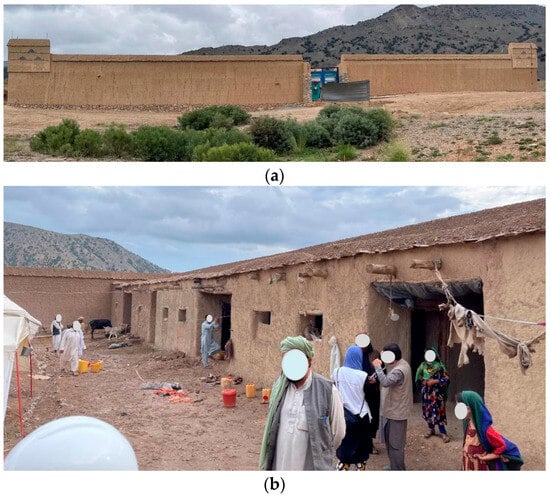

Figure 2.

(a) Monolithic mud (Pakhsa) compound wall, (b) rooms are constructed along one side inside the Qala to optimise sunlight. Reprint with permission [42]; copyright 2022, Miyamoto International, Inc.

3.1. Raw/Unfired Clay Brick Houses: Construction Techniques and Materials

Adobe brick houses are less common than poured layered mud or Pakhsa houses, primarily serving small single-family homes or expedited construction. These single- or rarely double-storey walled buildings are often built on dry-stone masonry wall foundations. The foundations are placed about half a metre to a metre below ground level and the same height above ground level. The foundation width is generally the same as the width of the wall, 350 to 500 mm. After raising the masonry foundation to the desired height above ground level, a layer of mud mortar is applied, forming bedding for the first layer of adobe bricks. Mortar layers range from 1 to 3 cm thick, with wall thicknesses between 35 and 50 cm. Bricks are typically produced on-site using simple tools, often without knowledge of soil properties. As mentioned by Dhandhukia et al. [43], optimal compressive strength is achieved with a soil composition of approximately 55% sand and 45% silt and clay, with a plastic limit of 2–6%. Wood lintels are installed at the desired opening height, often about 500 mm below the level of ceiling, covered by one or two additional brick layers. A final layer of mud mortar is applied before placing the roof beam on top (Figure 3). Roof beams, known as Dastak, are round wood logs with a diameter of at least 150 mm, spaced about 0.6 m apart. Smaller wood members (50 mm round or split, called Walch) or wood planks span the main beams. Reed or similar plants cover the Walch, topped with a 60 to 100 mm layer of foot-compacted clay (Ghora-Gel) and a 3 to 5 cm layer of fine-grained dry clay (Khoshki), which is then waterproofed with polythene sheeting and protected by straw-mud plaster (Kah-Gel). Roofs are flat with a slight slope for drainage, but they are not attached to the walls, leading to common roof failure mechanisms (Figure 1).

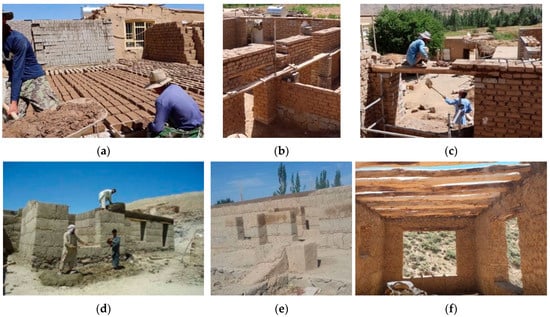

Figure 3.

Construction of earthen houses. (a–c) Adobe brick earthen house construction. Reprinted with permission [44]; copyright 2020, Bamyan TV. (d,e) Pakhsa wall construction. Reprinted with permission [45]; copyright 2022, IMT—Mines Alès. (f) A Pakhsa wall room with wood beams under construction. Reprinted with permission [46]; copyright 2020, ROSTA Film.

3.2. Monolithic Mud/Pakhsa Houses: Construction Techniques and Materials

Mud/Pakhsa houses are primarily single-storey, though occasionally double-storey, earth-walled constructions made from kneaded mud in the form of thick poured layers formed by hand. They feature dry-stone masonry foundations set 0.5 to 1.0 m below ground, generally extending to the same height above ground. Once the masonry foundation is complete, the first layer of the mud wall, known as Pakhsa, is constructed, typically measuring 0.4 to 0.6 m in height.

The construction of each Pakhsa layer involves several steps:

- Soil Procurement: Sufficient cohesive soil is gathered along the length of the wall.

- Wet Mixing: The dry clay is wetted by ponding with water. No fibres or other additives are used in Pakhsa wall construction.

- Kneading: The wet earth is kneaded/puddled and pressed, often by animals walking over the mixture. This process, which may include turning the mixture with a shovel 2–3 times, eliminates air pockets and enhances the consistency of the mud, aligning clay particles to improve plasticity and moldability.

- Application: After a while (less than 24 h), the prepared mud is transferred to the mason using a handheld shovel. Each shovelful is piled and compressed by hand or foot to avoid cavities, achieving a depth of about 500 mm. Thus, a three-metre-tall wall will require six 0.5 m high Pakhsa layers.

- Levelling: The mason levels the wet Pakhsa to prepare it for the next layer using a flat-headed wooden mallet.

- Shaping: Once the Pakhsa has dried sufficiently to support the weight of a person but remains soft enough for carving, the mason shapes both faces using a plumb bob and handheld trowel, ensuring the wall is plumb and maintains the desired thickness. The wall width typically ranges from 500 mm to 700 mm.

After allowing the Pakhsa about five days to attain the necessary strength, this process is repeated for each layer until the desired wall height is achieved. The final Pakhsa is placed atop the wall, on round roof beams. The roofing of mud houses employs techniques and materials like those used in brick houses. According to Alejandro and Dermot [47], this technique resembles cob, traditionally used in the British Isles and Brittany, but without the use of natural fibres.

4. Study Methodology

This paper conducts a comprehensive review of the relevant literature, earthquake-resistant codes, standards, and normative documents related to various techniques and provisions for reinforcing earthen buildings to enhance their seismic resistance. The aim is to evaluate these reviewed techniques and guidelines to develop a unified set of specifications and reinforcement methods in the form of an earthquake-resistant model earthen house, serving as a guide for upgrading adobe and Pakhsa wall houses in rural Afghanistan.

Relevant data from various sources are summarised in tabulated form (Table A1, Table A2, Table A3, Table A4, Table A5, Table A6, Table A7, Table A8, Table A9, Table A10 and Table A11) for analysis and comparison. The review of research papers will provide insights into the different types of tested specimens (Table A1 and Table A2), types and techniques of potential reinforcement (Table A3 and Table A4), assessing their effectiveness (Table A4 and Table A5) and applicability to earthen construction in Afghanistan. Factors such as cost, material availability, sustainability, local architecture, construction typology, and the skills required for implementation will be considered. Additionally, the review of standards, codes, and normative guidelines will summarise key earthquake-resistant design and construction features from various sources into a tabular format (Table A7 and Table A8). After identifying key provisions from each publication, a comprehensive set of unified specifications will be proposed for the construction of both adobe brick (Table A10) and Pakhsa wall earthen buildings (Table A11), considering the unique characteristics of these earthen structures in the country.

As a conclusion, an earthquake-resistant earthen model house will be developed, incorporating specifications from various relevant standards and different reinforcement options and application techniques, which will serve as a guide model for adapting to earthquake-resistant earthen houses.

5. Identification of Relevant Documents for Review

In Afghanistan, the two primary types of earthen buildings are walled un-fired clay brick structures and mud wall/Pakhsa buildings, as previously defined. While numerous laboratory studies (Table 2) have focused on earthquake reinforcement and strengthening adobe brick buildings (some of which have been incorporated into building codes for the design and construction of earthen structures), there has been no laboratory research on earthquake-resistant design and construction for Pakhsa house buildings.

Table 2.

List of journal papers reviewed.

Rammed earth walls share several characteristics with Pakhsa construction, including wall thickness, comparable heights of rammed earth blocks and Pakhsa, and similar unit weights. Given these similarities, the authors propose that reinforcement techniques used in rammed earth construction could also be adapted for mud/Pakhsa wall systems. Consequently, this review examines sources related to earthquake-resistant rammed earth construction to propose earthquake-resistant design and construction guidelines for mud/Pakhsa buildings. The reviewed publications include only those journal papers (JPs), standards (Ss), building codes (BCs), and normative documents (NDs) published by technical organisations that contains seismic design and construction provisions. Table 2 lists the reviewed journal papers, and Table 3 presents the list of reviewed building codes, standards, and technical guidelines relevant to earthquake-resistant design and construction of adobe brick and rammed earth construction.

Table 3.

List of reviewed building codes (BCs), standards (Ss), and normative documents (NDs).

Some references, such as [49,51,54], are not included in the comparative analysis due to limited experimental details, similarity to other studies, or unavailability of the full text, ensuring that the tables are based on sources with sufficiently detailed and verifiable information.

6. Review of Journal Papers, Standards, Building Codes, and Normative Guidelines

This chapter offers a technical review of experimental research and normative documents on the seismic resistance and retrofitting of adobe and rammed earth buildings, presented in two parts: Section 6.1, covering scholarly experimental evidence, and Section 6.2, examining relevant standards and codes. Key numerical results, specimen geometries, loading protocols, reinforcement details, and material properties are cross-referenced with the summary tables in Appendix A (Table A1, Table A2, Table A3, Table A4, Table A5, Table A6, Table A7, Table A8, Table A9, Table A10 and Table A11). Table A1 and Table A2 outlines the tested samples, Table A3 and Table A4 summarise reinforcement types and arrangements, and Table A5 and Table A6 compile the main qualitative and quantitative findings. The features of earthquake-resistant design from the reviewed standards listed in Table 3 are consolidated in Table A7 and Table A8 to support the unified specifications proposed for the model earthquake-resistant earthen house. Each subsection concludes with a brief note on evidence quality.

6.1. Detailed Technical Review of Journal Publications

6.1.1. Studied Samples—Size and Configuration

The experimental corpus encompasses a range of models, from small wall panels to compound configurations, including C-, I-, L-, T-, and U-shaped assemblies, as well as 1:4 to full-scale single-room house models, selected to replicate specific boundary conditions and capture diverse in-plane and out-of-plane failure mechanisms (Table A1 and Table A2). Planar adobe walls have been investigated in [57,58,59,61,62,63,65], whereas rammed earth wall panels were studied in [62,64,67]. Compound adobe and rammed earth wall assemblies (C-, I-, L-, T-, and U-shaped) were examined in [52,55,60,62,63,65,66,69,73,74]. These corner geometries sometimes including openings (e.g., door/window spaces) were used to simulate realistic building layouts and induce out-of-plane actions. The corner geometry provided stiffness restraint in one direction while allowing out-of-plane displacements in the orthogonal wall, effectively capturing torsional effects, wall-wall interaction, and complex load paths typical of actual earthen houses. A relatively smaller portion of laboratory programmes focused on single-span box specimens with relatively thin walls (≤300 mm) [48,49,50,51,53,54,56,68,70,71,72], providing consistent data for characterising shear and diagonal cracking. Specimen dimensions varied widely, with lengths of 0.8–5.8 m, heights of 0.8–3.45 m, and wall thicknesses of 50–600 mm, reflecting both laboratory constraints and attempts to approximate traditional field construction. Fewer studies [62,63,64,65,69,73,74] investigated thicker walls (>400 mm), typical of Afghan adobe and Pakhsa houses, where mass, slenderness, and wall-roof interactions may significantly influence structural behaviour.

6.1.2. Loading Protocols and Measured Response Parameters

The reviewed studies employed a range of loading protocols to characterise the seismic behaviour of adobe and rammed earth walls (Table A1). Two primary approaches dominated: quasi-static cyclic lateral loading and dynamic shaking-table testing. Small- and medium-scale wall panels were most frequently subjected to quasi-static cyclic protocols [55,58,59,60,61,62,63,67,69,73], enabling detailed measurement of initial stiffness, peak shear capacity, displacement or drift limits, ductility indices, and hysteretic energy dissipation (Table A5). These controlled tests provided the most complete quantitative datasets and form the basis for the percentage improvements summarised in Table A5. However, because panel tests omit system-level effects such as diaphragm interaction, corner confinement, gravity mass distribution, and three-dimensional load transfer, their quantitative results cannot be directly generalised to full-scale buildings.

Dynamic and shaking-table tests were used less frequently but provided essential information on the global seismic response of full-scale adobe houses, U- and L-shaped assemblies, and thick rammed earth walls [50,51,52,53,56,62,63,65,68,70,71,72,74]. These experiments produced fewer direct numerical measurements but captured system-level behaviours including cracking progression, rocking response, residual drift, out-of-plane stability, and collapse prevention (Table A5 and Table A6). The geometric scale and configuration of these specimens, often incorporating multi-wall assemblies and wall thicknesses of 0.40–0.60 m, limited the acquisition of complete force-displacement curves, resulting in primarily qualitative descriptions of global performance.

Additional loading arrangements included diagonal compression, tilting-platform tests, monotonic lateral loading, and out-of-plane pull-down tests applied to wall panels, U-shaped assemblies, and full-house specimens [48,57,64,66]. These protocols were used to isolate specific mechanisms such as shear capacity, overturning behaviour, and out-of-plane bending resistance. Across the literature, the choice of loading protocol reflected the targeted failure mode and specimen geometry: cyclic testing provided quantitative comparison of reinforcement strategies, while dynamic and tilt-based methods clarified system-level behaviour and collapse mechanisms. Together, these methodologies define the quantitative and qualitative parameters used for the comparative synthesis in Section 6.1.6.

6.1.3. Boundary Conditions in Experimental Studies

Foundation/Base Restraint

Most investigations mounted specimens on reinforced concrete bases providing fixed or near-fixed support. Studies evaluating strengthening systems incorporating vertical or timber elements—such as bamboo or timber posts, PVC/steel bars, external mesh strips, or tie-rod systems—compared anchored and unanchored configurations. Anchored walls consistently exhibited reduced rocking and sliding, greater lateral stability, and higher energy dissipation. Anchorage of timber frames, vertical tendons, or mesh connectors improved lateral stiffness and limited residual drift, particularly under strong shaking. Tests on adobe and RE walls confirm that mechanical foundation anchorage substantially improves the seismic effectiveness of reinforcement [48,50,55,65,68,70]. These experimental findings were subsequently translated into post-earthquake reconstruction practice in Peru, where reinforced adobe houses incorporated plain concrete foundations, collar beams acting as lintels, improved wall-to-wall connectors, and shear keys at collar-beam intersections to limit sliding and separation under seismic loading [83]. Further refinements proposed the use of vertical dowels connecting foundations to mesh reinforcement and collar beams, shown to reduce rocking response and mitigate shear-friction failures at wall-beam interfaces [84].

Axial (Vertical) Loading

Axial loading was applied to simulate roof mass or gravity stresses (Table A1). Full-scale house models generally relied on their own roof weight [50,51,52,53,56,67,70,71,72], whereas panel tests applied controlled vertical precompression. Adobe walls were commonly loaded between 0.1 and 0.32 MPa [62,63,64,65,69,73], while thicker RE walls were loaded at lower stresses (0.008–0.08 MPa). Some studies varied axial load to quantify its influence: increased vertical stress delayed cracking and enhanced shear resistance within a limited range [62]. Axial compression was introduced through rigid steel or concrete loading beams or collar beams to ensure uniform distribution. Axial load magnitude and uniformity were therefore major determinants of shear capacity and drift performance.

Roof/Diaphragm/Top Boundary Conditions

Shaking-table studies used timber roofs, collar beams, or lightweight roof prototypes [48,53,56,68,70,71,72], which acted as diaphragms contributing to load distribution and top confinement. Some cyclic tests on multi-leaf or geometrically complex walls used stiff crown beams to provide continuity and to apply combined vertical and lateral loading [55,69,73]. In contrast, tests isolating shear or bending mechanisms—such as diagonal compression panels [57] or out-of-plane pull-down tests [66]—often left the top edge unrestrained. Thus, top boundary restraint varied according to the targeted behavioural mode: diaphragms were included when assessing system-level response, whereas free-top or beam-supported conditions were selected for fundamental shear or flexural characterisation.

6.1.4. Reinforcement Materials, Application Techniques, and Anchorage Conditions

Across the reviewed experimental programmes, the seismic effectiveness of adobe and rammed earth reinforcements depends not only on the choice of material but also—often more critically—on how these materials are applied, anchored, and integrated with the substrate (Table A3 and Table A4). Reinforcement performance is governed by three interdependent factors: (i) the mechanical characteristics of the reinforcement material; (ii) the continuity and distribution of the applied system; and (iii) the interface and anchorage conditions that ensure load transfer between the reinforcement and earthen wall. The following synthesis integrates material types, application strategies, and anchorage practices reported in the literature.

Metallic Reinforcement Systems

Metallic solutions—including steel wire meshes, welded wire meshes, steel rebars, steel wire ropes, and A36 steel plates—represent the most widely tested reinforcement category. Wire meshes are typically surface-mounted on both faces and attached with nails and screws; they are tied together with through-wall connectors (steel bolts, rods, solid timber, or tie wires) and then covered with a 1:4 cement-sand mortar to prevent delamination and ensure confinement [52,53,54,55,62,66]. In some studies, rebars were placed vertically and horizontally on both faces and tied across the wall thickness, enhancing global confinement and improving shear transfer [61]. A36 steel plates, mounted externally and clamped through the wall with steel tie rods or bolts, formed stiff confinement jackets that significantly increased lateral load capacity but occasionally introduced brittle post-peak behaviour if not balanced with ductile detailing [63].

Metallic systems generally require robust anchorage at the foundation and/or roof beams to be fully effective. Studies consistently show that the presence of anchored mesh edges or through-rods reduces rocking, mitigates separation at wall-foundation interfaces, and improves cyclic stability. The literature highlights that insufficient anchorage—not material weakness—is the most common cause of premature failure in metallic retrofits.

Polymeric, Geosynthetic, and Textile Reinforcement Systems

A broad array of polymeric solutions has been evaluated, including geogrids, geonets, polyester/PP meshes, nylon ropes, soft plastic fencing, tarpaulin strips, and proprietary geo-meshes (e.g., Tensar products). These systems are generally lighter and more flexible than metallic meshes, permitting easier on-site handling and improved compatibility with irregular earthen surfaces. These systems are mostly applied on both external surfaces of walls, partially or fully covering the walls. Nylon rope mesh systems have also been validated through full-scale shaking-table tests, in which cracked single-storey adobe house models were retrofitted using tensioned rope meshes connected across wall thickness and re-tested under strong ground motions, demonstrating effective collapse prevention and preservation of structural integrity [71,85]. Based on this experimental evidence, an engineering design approach for rope mesh reinforcement was developed and later incorporated into the Peruvian earthen construction code, Norma E.080 [75].

- Geogrids and geo-mesh are typically surface-mounted on both faces of walls. They are sometimes attached to the wall by plastic plugs and mostly tied together using through-wall connectors (nylon/plastic tie wires, steel bolts, and rods) [55,56,58,60,62,68].

- Polypropylene/polyethylene geonets are commonly fixed to the walls using U-shaped steel staples [59].

- Nylon meshes/nylon rope meshes and plastic meshes are attached to the wall using plastic plugs and nylon strings or tie rods to maintain cross-wall continuity [60,71,72,73,74].

- Tarpaulin strips are adhered using specialised adhesives as mechanical fastening is not feasible [64].

Polymeric systems generally exhibit favourable ductile behaviour when plastered, particularly when mesh continuity, overlap, and anchorage at boundary elements are ensured. Several studies reported improved hysteretic stability and enhanced displacement capacity with geogrid systems tied to collar beams or ring beams [55,62,68]. Conversely, insufficient fastening or inadequate bonds can lead to premature peel-off, limiting their contribution to shear resistance. Experimental studies further demonstrate that the effectiveness of polymer and PP-band mesh reinforcement depends strongly on the tightness of mesh installation and the presence of protective plaster layers, which improve load transfer, reduce gap formation, and protect polymers from ultraviolet exposure and temperature-related degradation [86].

Natural Fibre and Traditional Reinforcement Systems

Traditional plant-based materials—bamboo, cane, palm meshes, reed mats, and palm ropes—appear prominently in earlier studies and remain attractive due to local availability and sustainability. Vertical bamboo poles (often 1.5× wall thickness) combined with split canes embedded every fourth adobe course represent a common historical approach [48,49,50,55]. These elements are typically tied or interwoven through the wall thickness, enhancing out-of-plane stability and providing restraining action during cyclic lateral loading.

Palm mesh and reed reinforcements, when tied with palm ropes and embedded in clay-straw plaster, have shown meaningful improvements in energy dissipation and fragmentation control [58]. However, their effectiveness is highly sensitive to anchorage quality, mortar infill, and mesh density; poorly tied systems tend to slip or rupture under cyclic loading.

Timber-Based Reinforcement and Confining Systems

Timber elements—including vertical posts, horizontal belts, timber frames, and surface-mounted planks—provide a versatile means of improving in-plane and out-of-plane resistance. Timber planks and frames are usually anchored through the wall using 8 mm steel bolts or solid timber connectors, while in some studies they are integrated with post-tensioning elements for enhanced confinement [65,66,69]. Continuous timber frames have proven particularly effective in delaying out-of-plane collapse and reducing residual drift, especially when tied to foundation sills or ring beams.

6.1.5. Influence of Key Variables

- 1.

- Material Properties and Additives

Earthen materials are intrinsically brittle with low tensile strength and limited ductility [50,52,55,58]. Mechanical performance improves with the inclusion of fibres, straw, or industrial meshes, which delay crack propagation and enhance post-peak stability [57,58,65]. Synthetic solutions, including polymer mesh, geosynthetics, polypropylene (PP) band meshes, and textile-reinforced mortars (TRMs), provide enhanced energy dissipation, drift capacity, and collapse prevention after cracking, despite their limited contribution to initial stiffness due to low elastic rigidity relative to masonry [55,56,70,73,74,87]. Mortar type, soil composition, and ageing of materials also significantly affect stiffness, strength, and damping properties [57,67].

- 2.

- Wall Geometry, Openings, and Boundary Conditions

Wall height, thickness, aspect ratio, and openings critically influence in-plane and out-of-plane responses [62,65,69,72]. Taller walls and those with large openings are prone to diagonal cracking, shear failure, and overturning. Adequate anchorage at foundations and crown beams is essential, particularly for multi-storey adobe constructions [50,52,65,69,72]. Corners and intersections are high-stress regions; poor reinforcement in these zones reduces the effectiveness of retrofit measures [52,62,72].

- 3.

- Reinforcement Strategies and Retrofitting

Experimental evidence demonstrates multiple effective reinforcement strategies:

- Cane mesh and crowning tie beams: Interior cane mesh with tie beams improves wall integrity, limits separation, and delays collapse [50,52,55]. Horizontal confinement is crucial; its absence causes premature collapse [50,52,55].

- Wood boards with steel rod ties: Provide moderate delay of collapse by distributing tensile stresses [52].

- Rope and nylon mesh: Installed in channels or tied through walls, they reduce drift, confine cracks, and prevent overturning, effective even in two-storey buildings [52,72].

- Wire mesh with mortar: External welded wire mesh covered with cement mortar provides tensile continuity, increases lateral strength, and improves out-of-plane stability [52,55,56,62,70].

- Polymer and geosynthetic meshes: Low-cost alternatives offering high ductility and post-peak stability, capable of preventing collapse under strong seismic motions [55,56].

- Textile-reinforced mortar (TRM): Enhances ductility (peak drift increase up to 700%) and energy dissipation and avoids collapse in rammed earth walls, although original stiffness is not fully restored [73,74].

- Geo-mesh in earth-based mortar: Redistributes stresses under out-of-plane cyclic loading, improves displacement capacity, and delays structural instability [74].

The success of these strategies depends on continuous wall coverage, secure anchorage, and proper detailing at corners and intersections [52,59,62,67].

- 4.

- Cyclic Loading, Dynamic Behaviour, and Energy Dissipation

Shaking-table and cyclic lateral loading tests reveal the following:

- Unreinforced walls exhibit brittle failure, rapid stiffness degradation, limited drift, and minimal energy dissipation [50,52,56,65,72].

- Reinforced walls maintain structural integrity, demonstrate stable hysteresis, allow higher drift, and dissipate more energy [55,57,62,67,69,72,73,74].

- Rope meshes and TRM provide improved recentring and allow repeated seismic events without collapse [72,73].

- Dynamic properties, including period elongation and damping, are improved in reinforced walls, although initial stiffness may remain below that of an undamaged unreinforced wall [73,74].

- 5.

- Axial Load and Confinement Effects

Applied axial compression increases lateral load capacity in unreinforced walls, while reinforced walls show limited sensitivity to vertical loads due to confinement provided by meshes, ropes, or TRM systems [62,65]. Proper confinement at edges and intersections is critical to limit out-of-plane drift and residual displacements [52,65,69,72].

- 6.

- Failure Modes and Collapse Prevention

Common failure modes include diagonal cracking, corner crushing, rocking, plaster detachment, and overturning [50,51,52,58,59,65,72]. Reinforced walls redistribute stresses; reduce crack localization; increase lateral strength and peak-sustained deformation and ductility; and delay/prevent failure, enhancing occupant safety [52,55,56,67,70,71,72,73,74]. Low-cost, locally available reinforcements (rope, polymer mesh, and TRM) are effective in preventing catastrophic collapse even under severe shaking [50,55,56,72].

- 7.

- Practical Considerations

- Cost and accessibility: Reinforcements are typically low-cost and locally available [50,51,52,55,57,58,70,71,72,73,74].

- Installation and detailing: Correct anchorage, wall coverage, and corner treatment are vital [51,52,59,62,67].

- Sustainability: Natural fibre and rope reinforcements are environmentally friendly and compatible with heritage structures [58,72].

- Multi-storey and heritage buildings: Reinforcement must balance structural performance with architectural preservation; excessive permanent drift may not be acceptable for heritage walls [62,71,72].

6.1.6. Synthesis of Experimental Results

Experimental evidence clearly establishes that unreinforced adobe and RE walls perform poorly under seismic loads due to low strength, stiffness degradation, and brittle mechanisms. Strengthening methods—from meshes and geogrids to TRM, timber, steel plates, NSM bars, and rope nets—substantially improve seismic performance. Strength typically increases by 30–200%, ductility by factors of 3–7, and drift capacity by 2–2.5%. Energy dissipation grows dramatically, and collapse—especially out-of-plane—is consistently prevented (Table A5 and Table A6).

Even where stiffness is not restored, strengthened walls exhibit controlled, ductile deformation and maintain integrity under repeated or strong shaking. Many techniques are low-cost, culturally compatible, and suitable for high-risk, low-resource settings. Together, these findings show that practical, scalable seismic retrofitting of earthen buildings is achievable, effective, and essential for risk reduction and heritage preservation. Field evidence following major earthquakes corroborates these experimental observations, as reinforced adobe houses constructed using mesh-based and collar-beam systems demonstrated excellent seismic performance during the 2007 Mw 8.0 Pisco earthquake, while neighbouring unreinforced dwellings suffered severe damage or collapse [88].

Global Strength and Stiffness Trends

Unreinforced specimens consistently exhibited rapid damage progression, including diagonal shear cracking and shear failure [52,58,63,64], brittle out-of-plane cracking and degradation [62,63], limited deformation capacity due to poor crack accommodation [60,63], pinched hysteresis from repeated crack opening/closure [63], corner separation in multi-wall configurations [60,68], weak mortar-block bond failure [60], and abrupt post-peak collapse [48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,66]. Reinforcement markedly improved performance. Vertical bamboo canes anchored to foundations and tied with horizontal split canes increased wall strength [48], and externally nailed steel wire mesh with cement mortar prevented collapse in full-scale adobe modules [52,53,54], but several studies report that its post-elastic response may become unstable, with stiffness loss and brittle failure modes developing under strong shaking if ductile detailing is insufficient [55,89]. NSM steel bars increased lateral strength by up to 181% [61], flexible welded wire mesh tripled ductility, ultimate displacement, and shear capacity at a low axial load [62], and polyester strips [67], palm/reed meshes [58], plastic/geosynthetic meshes [55,59], and nylon rope nets [72] enhanced load capacity, energy dissipation, and stability. Timber planks provided 70% higher lateral capacity, 2.5-fold displacement capacity, and a 10-fold energy dissipation increase [69], while steel plates raised in-plane and out-of-plane strength by 30% and 60% [63]. Timber confinement more than doubled out-of-plane static capacity, and foundation anchorage significantly reduced rocking and residual drift [65].

Stiffness trends are more nuanced. Some systems—steel plates [63], cement-mortared welded wire mesh [62], and timber confinement [69]—increase initial stiffness. Others, especially TRM [73] and polymer/nylon mesh systems [55,59,70,71], aim not to stiffen but to stabilise, enabling ductile deformation without restoring original elastic stiffness. Thus, while strength gains are consistent across techniques, stiffness outcomes depend strongly on material compatibility and load transfer details.

Deformability, Drift Capacity, and Ductility

Unreinforced walls typically fail at global drifts below 0.5–0.6% for in-plane loading and exhibit similarly limited out-of-plane drift tolerance [63,69]. Dynamic tests show collapse of unretrofitted adobe between PGA 0.14 and 0.39 g [63,65,69].

Strengthening significantly enhances deformation capacity. Plaster meshes and additives [57] and palm/reed systems [58] consistently improve ductility; diagonal near-surface mounted (NSM) reeds increase displacement capacity by up to 60% [58]. Polyester strips [67] allow strengthened walls to withstand four additional displacement cycles, increasing cumulative deformation capacity by a factor of 4–5. TRM [73] yields dramatic gains: drift at peak load increases by 235–700% compared to the original wall. Nylon rope reinforcement [72] multiplies displacement capacity by 3–5 for two-storey buildings under strong shaking. Timber grids with post-tensioning [69] allow walls to reach drifts of 2.5%—five times the original capacity.

Energy Dissipation and Cyclic Stability

Unreinforced adobe and RE exhibit low cumulative energy dissipation and strong hysteretic pinching due to diagonal cracking, sliding, and early stiffness loss [59,61,63]. Strengthened systems substantially increase energy dissipation. Palm and reed retrofits [58] produce fuller hysteresis loops; although palm meshes show more pinching, they achieve higher cumulative energy dissipation than NSM reeds. Polyester strips [67] decrease per-cycle dissipation but increase cumulative dissipation up to four-fold due to extended cycling before failure. Meshes and geonets in [55,56,59,62] improve cyclic stability by delaying crack opening and preserving integrity at large drifts. TRM [73] dissipates ~60% of input energy with stable damping and no collapse. Rope mesh retrofits [72] reduce residual drifts and maintain stable hysteresis, while timber and steel systems [63,65,69] enable extensive cycling without instability.

Out-of-Plane Performance and Collapse Prevention

Unreinforced earthen walls are particularly vulnerable to out-of-plane demands. Studies [63,65,69,74] show brittle rocking-type failures at low accelerations, with rapid loss of stability and little warning. In [65], collapse occurred between 0.91 and 0.95 g in quasi-static tests but at much smaller shaking intensities (0.39 g) on the table.

Strengthening yields transformative improvements. Timber grids [65,69] increase out-of-plane capacity by factors of 2.3–2.4 and prevent overturning even at PGA = 0.72 g. Steel plates [63] enable walls to resist accelerations up to 0.52 g without collapse and maintain stability at roof accelerations >1.64 g. Geogrids, welded wire meshes, and polymer meshes [55,56,62] significantly delay overturning and maintain integrity even when large residual drifts develop. TRM and geo-mesh-based strengthening [73,74] greatly improve out-of-plane deformation limits, preventing catastrophic buckling by redistributing stresses.

Influence of Axial Load, Boundary Conditions, and Damage State

Axial load effects are mixed. For unreinforced walls, increased axial compression generally raises peak strength but reduces displacement capacity and accelerates degradation [61,62]. Strengthened walls show weaker or inconsistent dependence on axial load: meshes in [62] and NSM systems in [61] show little additional benefit at higher vertical stress, as confinement provided by reinforcement dominates over axial compression.

Boundary conditions strongly influence wall performance. Adobe walls with end confinement fail later and at higher accelerations than isolated walls [65], while strengthened walls remain stable even with reduced confinement. Foundation anchorage of timber elements [69] notably decreases residual drift during strong shaking.

Initial damage state also matters. TRM applied to a previously damaged RE wall [73] improved ductility and prevented collapse but could not restore original stiffness. Similar observations apply to mesh systems in [56,74]: reinforcement enhances safety but does not erase the structural effects of pre-existing cracks.

Failure Modes and Mechanism Shifts

Unreinforced walls fail through brittle diagonal shear cracking, sliding, or rocking; out-of-plane failure is sudden and catastrophic. Studies [57,58,59,61,63,71] describe localization of cracks and rapid loss of load capacity.

Strengthening shifts failure to more distributed, ductile mechanisms. Mesh-based systems (polymer, polyester, palm, straw, and geosynthetic) distribute cracking and maintain coherence even after significant wall damage [55,57,58,59,67]. TRM [73] and geo-mesh systems [74] transform localised bending cracks into distributed damage patterns, delaying instability. Nylon rope nets [72] and timber grids [65,69] confine wall segments, preventing separation and changing failure into controlled rocking. Steel plates [63] change the governing mechanism to bearing-driven ductile behaviour, avoiding diagonal cracks.

Practicality, Sustainability, and Applicability

Many studies emphasise low-cost, locally available, and easy-to-apply systems. Polymer meshes [55,56], PP-band meshes [70], nylon rope nets [71,72], and plastic meshes [56] are affordable, easy to install, and compatible with traditional construction. While welded wire mesh systems are technically effective, their relatively high material and labour costs limit large-scale adoption in low-income rural contexts, particularly when compared with polymer, rope, or textile-based alternatives [55,90]. Natural fibres—straw, palm, and reeds [57,58]—offer sustainable, culturally compatible solutions. Timber systems [65,69] provide robust improvement but require careful detailing and may intrude on historic interiors. Steel plates [63] are effective and minimally invasive but require corrosion protection. Bamboo canes greatly improve the strength of adobe models, but their use is limited to internal installation during new construction and is impractical for retrofitting or for regions where bamboo is not readily available. TRM systems [73,74] balance compatibility and reversibility, making them promising for heritage preservation.

6.2. Review of Earthquake-Resistant Provisions of Earthen Construction in Seismic Codes, Standards, and Normative Documents

Building codes set minimum safety and performance requirements and have historically evolved following major earthquakes (e.g., Japan after the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake and California after the 1933 Long Beach earthquake, Olshansky [91]). Afghanistan frequently experiences severe seismic damage, particularly to earthen dwellings, and its current guidelines require revision to reflect local materials, vernacular construction practices, and recent advancements. Persistent challenges include limited technical capacity, scarce data, and weak enforcement, as noted by Mashal et al. [92]. In this section, the features of earthquake-resistant design from the reviewed standards listed in Table 3 are consolidated in Table A7 and Table A8 to support the unified specifications proposed for the model earthquake-resistant earthen house.

6.2.1. Codes, Standards, and Normative Documents Reviewed

Peru—Norma E.080:2017

Norma E.080 (2017) [75], issued by the Ministry of Housing, Construction and Sanitation of Peru, is the national regulation governing design, construction, and repair of earthen buildings, including adobe and rammed earth. It provides a modern, comprehensive framework with annexes covering soil testing and detailed reinforcement systems, including plant-based fibres, geogrids, and synthetic rope meshes.

Nepal—NBC 204:2015

NBC 204 (2015) [76], published by the Government of Nepal’s Department of Urban Development and Building Construction, establishes national requirements for earthquake-resistant earthen construction. It is complemented by NBC 203 [93] for low-strength masonry and the Nepal Reconstruction Authority (NRA) Design Catalogues [94], forming a unified set of practical, field-level guidelines.

New Zealand—NZS 4297, NZS 4298, NZS 4299

Developed by Standards New Zealand, these documents constitute the country’s principal earth-building regulatory suite. NZS 4297 [77] provides engineering design procedures; NZS 4298 [78] establishes materials, workmanship, and testing requirements; and NZS 4299 [79] gives acceptable solutions for limited-design and non-engineered earthen buildings. The suite has been updated to incorporate findings from post-earthquake investigations and full-scale testing of adobe walls.

India—IS 13827:1993 (Reaffirmed 2003)

IS 13827:1993 [80], published by the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS), provides guidelines for improving the seismic safety of non-stabilised traditional earthen dwellings (adobe, rammed earth, and similar vernacular systems). It is intended for widespread rural application and focuses on simple construction and strengthening techniques.

IAEE Guidelines—Guidelines for Earthquake Resistant Non-Engineered Construction

Originally issued by the International Association for Earthquake Engineering (IAEE) in 1980 as “Basic Concepts of Seismic Codes, Vol. 1, Part II” [95], this foundational document outlines global principles for seismic provisions in non-engineered construction. A later revised version (Arya et al. [81], adapted from the original [96], which itself is a revision of [95]) consolidates these principles and extends guidance to fired brick, concrete block, confined masonry, timber, stone, and earthen buildings. It remains an important reference where national codes are absent, outdated, or incomplete.

Construction Manual for Earthquake-Resistant Houses Built of Earth (Minke)

This manual by Minke [82], published through GATE-BASIN (Building Advisory Service and Information Network), originated from international research supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG), GTZ GmbH, and the University of Kassel. Rooted in field studies in Latin America and prototype testing, it provides practical construction and reinforcement guidance for adobe, rammed earth, textile earth-filled, and wattle-and-daub systems.

Afghanistan—Guidelines for Earthquake-Resistant Design, Construction, and Retrofitting of Buildings (2003)

These were developed by the United Nations Centre for Regional Development (UNCRD) and the Ministry of Urban Development and Housing (MUDH) of Afghanistan and authored by Prof. Anand S. Arya [24]. These 2003 guidelines consist of five parts, with Part E dedicated to earthen houses, covering site selection, material suitability, and construction and reinforcement details similar in scope to IS 13827 [80].

6.2.2. Technical Review of Codes, Standards, and Normative Documents

Site and General Requirements

National and regional standards for earthquake-resistant earthen construction display notable convergence despite differences in terminology, material culture, and seismic context (Table A7 and Table A8). While Norma E.080 [75] defines four seismic zones, NZS 4297/4298/4299 [77,78,79], IS 13827:1993 [80], Arya et al. (b) [81], and Arya et al. (a) [24] each employ three-tier classifications, whereas NBC 204 [76] and Minke [82] provide non-zonal, nationally applicable provisions. All documents prohibit construction on unstable soils—with a range including loose sands, expansive clays, fills, liquefaction-prone sediments, riverbanks, steep slopes, or areas subject to flooding, erosion, or landslides—and emphasise site drainage, roof overhangs, and protective plinths as primary moisture-defence measures. Environmental protection provisions are consistently embedded in these documents: Norma E.080 [75] mandates plinths, coatings, plasters, and adequate roof eaves; NBC 204 [76] requires damp-proof courses, roof projections, plastering, and drainage; NZS 4299 [79] prescribes rain deflection, drainage, and damp-proof courses; IS 13827:1993 [80] requires plinths, mud plasters, roof overhangs, and site drainage; Arya et al. (b) [81] specifies two-layer plaster, mud stucco, and bitumen application; Minke [82] discusses earthen wall protection conceptually; and Arya et al. (a) [24] mandates plinths, mud plasters, roof overhangs, and drainage. Plan configuration requirements further reinforce structural regularity: Norma E.080 [75] allows rectangular and symmetric plans and even curved walls; NBC 204 [76] requires symmetrical or regular rectangular plans with a maximum 3:1 length-to-breadth ratio; NZS 4299 [79] restricts layouts to rectangular forms; IS 13827:1993 [80] requires rectangular or symmetric plans; Arya et al. (b) [81] prescribes square rooms and symmetric plans; Minke [82] promotes compact square forms with ribbed rammed earth walls; and Arya et al. (a) [24] specifies rectangular and symmetrical plans. Provisions for construction on slopes are limited but explicit where present: NZS 4299 [79] permits building on slopes ≤20°, while NBC 204 [76] and Arya et al. (a) [24] provide slope-related guidance without quantified thresholds. Norma E.080 [75], IS 13827:1993 [80], Arya et al. (b) [81], and Minke [82] do not include equivalent slope criteria. Height limitations are broadly aligned, with the majority of documents restricting earthen buildings to a single storey, permitting attics or a second storey only in lower seismic zones or under controlled geometric conditions.

Footings and Plinths

All standards require continuous, load-bearing footings on firm natural ground. Norma E.080 [75], IS 13827:1993 [80], Arya et al. (b) [81], and Arya et al. (a) [24] allow stone or brick masonry and cyclopean or lean concrete footings; NBC 204 [76] specifies stone or burnt-brick masonry; NZS 4299 [79] mandates reinforced-concrete strip footings with a minimum soil bearing capacity of ≥300 kPa; and Minke [82] provides qualitative guidance rather than prescriptive footing configurations. Minimum footing widths range from the wall thickness to approximately 700 mm, with embedment depths from 400 to 750 mm. Plinths serve both structural and moisture-protection functions. All standards require a minimum plinth height of ≥300 mm above the finished ground level, although NZS 4299 [79] permits 200–375 mm. Waterproofing is addressed through polythene sheets, damp-proof courses, or waterproof muds, with erosion-resistant external facings mandated by IS 13827:1993 [80], Arya et al. (b) [81], and Arya et al. (a) [24].

Materials and Wall Design

Strength criteria vary considerably. Norma E.080 [75] uniquely defines allowable prism compressive, tensile, and shear strengths, while NBC 204 [76], IS 13827:1993 [80], Arya et al. (b) [81], and Arya et al. (a) [24] specify a 1.2 MPa adobe unit strength. NZS 4298 [78] requires ≥0.5 MPa for unstabilised units and introduces standardised test procedures, whereas Minke [82] provides qualitative recommendations without quantification. Minimum wall thicknesses range from 280 to 450 mm, with ≥380 mm being the most common (Table A7 and Table A8). All codes prescribe clay-sand mixtures; some include straw reinforcement (Norma E.080 [75], IS 13827:1993 [80], and Arya et al. (a) [24]), and all require the pre-wetting of adobes or bricks. Slenderness limits are consistent at L/t ≤ 10 and H/t ≤ 6–8, except in NZS 4299 [79], which allows H/t up to 10–12 under engineered design. Opening regulations are closely aligned, requiring pier widths and corner distances ≥ 1.2 m and limiting the opening area to 33–40% of the wall length.

Vertical bracing is achieved by buttresses, transverse walls, or pilasters in Norma E.080 [75], NBC 204 [76], IS 13827:1993 [80], Arya et al. (b) [81], and Arya et al. (a) [24], while NZS 4299 [79] substitutes engineered earth bracing walls. Minke [82] relies on compact, ribbed wall geometries to provide equivalent stability. Horizontal bracing is achieved by collar beams or roof diaphragms where specified.

Lintels and Reinforcement

Lintel materials vary regionally: Norma E.080 [75] specifies cane or timber; NBC 204 [76] requires hardwood; IS 13827:1993 [80], Arya et al. (b) [81], and Arya et al. (a) [24] require timber; and NZS 4299 [79] permits timber or reinforced concrete. Minimum bearing lengths range from 300 to 500 mm. Reinforcement approaches diverge substantially. Norma E.080 [75] employs bamboo, cane, geogrids, and synthetic ropes; NBC 204 [76] uses bamboo or timber posts at regular spacing; IS 13827:1993 [80], Arya et al. (b) [81], and Arya et al. (a) [24] use bamboo or cane bands tied to collar beams; NZS 4298/4299 [78,79] incorporate steel bars and polymer geogrids; and Minke [82] omits reinforcement specifications in favour of robust wall geometry (Table A7 and Table A8). All documents require anchorage at the foundation and collar beam, with reinforcement around openings mandated at least at the top (IS 13827:1993 [80], Arya et al. (b) [81], and Arya et al. (a) [24]) and at both top and bottom in Norma E.080 [75], NBC 204 [76], and NZS 4299 [79].

Roofs and Rammed Earth Provisions

Roofs must be lightweight and well-anchored, typically comprising timber frames or trusses. NZS 4299 [79] uniquely requires diaphragm action via plywood, plasterboard, or sarking. Overhangs range from 450 to 1000 mm across documents. Heavy roofing is discouraged due to seismic vulnerability. Rammed earth provisions are most detailed in Norma E.080 [75], NZS 4298/4299 [78,79], IS 13827:1993 [80], Arya et al. (b) [81], and Arya et al. (a) [24], specifying 100–150 mm loose lifts compacted to ~100 mm (or ≥98% maximum dry density in NZS 4298 [78]) and finished wall thicknesses in the 280–450 mm range; Minke [82] and NBC 204 [76] provide concise, less-quantified guidance.

Foundation and Geotechnical Considerations

Although this review focuses primarily on the seismic behaviour of adobe and Pakhsa walls, the performance of earthen buildings is also influenced by ground conditions. Two hazards are particularly relevant for Afghanistan: soil liquefaction in loose sandy or saturated deposits and differential settlement arising from soft clays, uneven soil profiles, or moisture variations. Both are critical because earthen walls are heavy, brittle, and highly sensitive to foundation movements, and even moderate settlements can initiate cracking long before seismic loading.

In rural Afghanistan—where most earthen houses are located—engineering site investigations, ground improvement, and foundation design optimisation are generally not practiced, not available, and economically impractical. As a result, foundations are often constructed directly on natural ground with limited attention to soil conditions.

The reviewed standards and research provide minimal geotechnical requirements. With the exception of NZS 4299 [79], which specifies a minimum soil bearing capacity of ≥300 kPa, none of the codes (Norma E.080 [75], NBC 204 [76], IS 13827 [80], IAEE Guidelines [81], or Afghanistan 2003 Guidelines [24]) define bearing capacity or settlement criteria. Instead, they offer general recommendations to avoid problematic sites—flood-prone areas, liquefaction-prone soils, steep slopes, riverbanks, marshy land, loose soils, poorly compacted clays, fills, or zones near faults—and to construct on firm natural ground.

Recognising these limitations, the proposed model house specifications (Table A11) incorporate simple, practical measures suitable for rural construction and aligned with the site-avoidance guidance in international standards. The proposed foundations use reinforced concrete or stone masonry, permitted only on firm natural ground, excluding expansive clays, loose sands, loose granular soils, soft cohesive soils, and fills thicker than 500 mm. Although no bearing capacity value is defined—consistent with most reviewed standards—the foundation width is increased to wall thickness + 250 mm for one storey and +350 mm for two storeys, with a minimum embedment of 800 mm or frost depth, whichever is greater (Table A10 and Table A11). These measures aim to reduce settlement risk and enhance overall stability without imposing unrealistic engineering demands on rural builders.

7. Discussion

7.1. Interpretation of Experimental Evidence

The reviewed experimental literature consistently demonstrates that unreinforced adobe and rammed earth (RE) walls possess low lateral strength, rapid stiffness degradation, and brittle failure mechanisms [48,50,52,55,56,58,62,63,64,65,69,72]. Across specimen types—from small wall panels to full-scale box houses—unreinforced walls typically fail at drift levels below 0.5–0.6% in-plane and at even lower out-of-plane deformation limits, with collapse often occurring at modest ground motions (PGA 0.14–0.39 g) [63,65,69]. Thin-wall box models (<300 mm) and thicker walls (400–800 mm) exhibit similar qualitative vulnerability, although thicker walls show increased mass and altered failure modes, particularly out-of-plane rocking [62,65].

Reinforcement strategies markedly improve seismic behaviour but differ in mechanisms and practical applicability. Metallic systems (welded wire mesh, steel plates, and NSM bars) provide substantial strength gains (30–200%) and increased displacement capacity, particularly when plastered and fully anchored [52,53,55,61,62,63,66]. However, welded mesh may introduce stiff, brittle post-peak behaviour if continuity and anchorage are inadequate [55,62]. Polymeric and geosynthetic solutions—geogrids, geonets, PP/PE meshes, and nylon rope nets—reliably improve ductility, energy dissipation, cyclic stability, and collapse prevention [55,56,59,60,67,68,70,71,72,73,74]. When tied through the wall or connected to collar beams, they mitigate delamination and provide stable post-peak behaviour. Textile-reinforced mortar (TRM) systems, although unable to restore original stiffness, significantly increase deformation and energy dissipation capacity, especially for previously damaged walls, delaying instability under both in-plane and out-of-plane loading [73,74].

Natural materials (bamboo, cane, palm, and reeds) improve performance when adequately tied through the wall but are sensitive to anchorage quality and are impractical where such materials are not locally available [48,49,50,55,58]. Timber-based confinement—vertical posts, planks, and grid patterns—consistently increases in-plane strength, out-of-plane capacity (up to 2.4× self-weight), and drift capacity (to ~2.5%), particularly when anchored to the foundation [65,69]. Across reinforcement categories, anchorage to foundation and crown beams emerges as a decisive parameter for performance.

Boundary conditions strongly influence observed performance. Fixed or near-fixed bases reduce rocking, while unrestrained tops promote pure bending or shear mechanisms [55,69,73]. Roof diaphragms, present in full-scale models, distribute lateral demands and delay out-of-plane instability [48,53,68,72]. Studies on thicker adobe and RE walls (>400 mm) indicate that mass and roof-wall interaction significantly modify collapse mechanisms compared to thinner laboratory models [62,65].

Collectively, the evidence indicates that multiple reinforcement systems provide substantial performance gains, but the degree of improvement depends critically on reinforcement continuity, attachment, anchorage at the foundation and roof, and boundary conditions.

7.2. Implications for Seismic Behaviour of Earthen Buildings

7.2.1. In-Plane Behaviour

Reinforced adobe and RE walls exhibit higher lateral capacity, increased drift limits, and fuller hysteresis loops relative to unreinforced walls [55,58,61,62,63,67,69,73]. Strength improvements range from 30% to >180%, especially for NSM bars [61], welded wire mesh [62], timber planks [69], and various polymeric fabrics [55,56,59]. Systems providing continuous tensile paths—meshes, rope nets, and TRM—reduce crack localisation and delay diagonal shear failure. Through-wall connections improve post-peak stability, whereas surface meshes with weak anchorage may debond and contribute little to shear resistance.

7.2.2. Out-of-Plane Behaviour

Unreinforced out-of-plane performance is extremely poor, with overturning occurring at low accelerations [63,65,69]. Reinforcements with through-thickness confinement—timber grids, polymer meshes tied through the wall, and steel plates with bolts—significantly increase out-of-plane strength and prevent catastrophic disintegration [55,56,63,65,69]. Full-scale shaking-table tests demonstrate that mesh- and timber-based systems maintain monolithic behaviour up to PGA ≈ 0.72 g [65,69].

7.2.3. Role of Axial Load, Roof Mass, and Boundary Restraints

Moderate axial compression can increase shear capacity in unreinforced walls but reduces deformability [61,62]. Reinforced walls are less sensitive to axial load variations because confinement dominates over gravity effects [62]. Roof diaphragms improve global stability by delaying crack propagation and reducing differential displacement [48,53,68]. However, most laboratory studies assume uniformly distributed roof mass, whereas traditional flat-roof construction in Afghanistan applies highly concentrated loads via timber beams. These concentrated loads induce stress concentrations not captured in most experiments, limiting the direct applicability of laboratory results to Afghan adobe and Pakhsa houses.

7.2.4. Damage Progression and Mechanism Shifts

Reinforcement consistently transforms brittle failure into controlled, distributed cracking with stable deformation. Polymeric meshes, TRM, and rope nets redistribute stresses and prevent sudden destabilisation [55,56,67,72,73]. Steel plates and welded meshes provide higher strength but require careful detailing to avoid brittle hinge formation [55,63]. Timber systems effectively restrain rocking and wall separation [65,69]. These observations are central for collapse prevention in high-seismicity contexts.

7.3. Alignment and Gaps Between Experimental Evidence and Existing Codes

Comparison of the experimental literature with existing seismic codes reveals significant alignment in foundational principles but equally important gaps in detailing, reinforcement specification, and recognition of system-level behaviour. International standards—including Peru’s Norma E.080 [75], Nepal’s NBC 204 [76], New Zealand’s NZS 4297/4298/4299 [77,78,79], India’s IS 13827 [80], the IAEE Guidelines [81,95,96], and the Afghan 2003 guidelines [24]—share a broadly consistent framework regarding site selection, wall geometry, opening limits, material suitability, and moisture protection. These provisions correspond well with experimental observations showing that regular building configurations, adequate thickness-to-height ratios, and strict moisture control mitigate cracking, preserve stiffness, and delay degradation in adobe and rammed earth structures [50,52,55,58,62].

However, the greatest divergence emerges in reinforcement detailing. Laboratory investigations demonstrate that reinforcement effectiveness is governed more by anchorage, through-thickness continuity, and load transfer mechanisms than by the material type alone [52,55,59,62,67]. Many codes nevertheless specify reinforcement in prescriptive terms—often bamboo or cane bands—without the interface detailing experimentally shown to be essential for ensuring cyclic stability and collapse prevention. For example, geogrids, geonets, polymer meshes, nylon rope nets, welded wire meshes, and TRM systems have repeatedly been shown to increase ductility, drift capacity, and energy dissipation by factors of 3–7, while preventing out-of-plane collapse [55,56,62,70,72,73,74]. Yet only NZS 4298/4299 explicitly incorporates geogrids or engineered reinforcement, and no code fully addresses TRM despite robust experimental evidence [73,74].

A second notable gap concerns roof-wall interaction. Experimental studies emphasise that roof stiffness, diaphragm action, and concentrated beam loads influence crack patterns, out-of-plane stability, residual drift, and overall distribution of seismic forces [50,51,52,53,56,65,70,71,72]. In particular, heavy flat roofs supported on discrete timber joists introduce concentrated vertical loads—conditions that significantly affect seismic performance but are absent from most codes, which assume uniform axial loading. Similarly, complex wall assemblies (C-, L-, T-, and U-shaped) display torsional and out-of-plane behaviours not adequately captured by current prescriptive rules [52,55,60,62,63,65,66,69,73,74]. While some standards provide general requirements for buttresses and transverse walls, they do not reflect experimentally observed stress concentrations at corners or the critical importance of intersection anchorage.

Finally, many codes provide general geometric and material rules but lack analytical design pathways. New Zealand remains the only jurisdiction offering a full engineering design methodology for earthen buildings [77], whereas other standards rely on prescriptive limits that cannot account for variations in wall thickness, reinforcement type, or roof mass. Given the diversity of seismic behaviours documented across the experimental studies, the absence of analytical validation limits the adaptability of existing provisions to contexts where vernacular construction differs significantly from the conditions assumed in foreign codes.

7.4. Implications for Afghanistan

Contextualising the experimental evidence for Afghan adobe and Pakhsa buildings reveals significant gaps between existing standards and local construction practices. Afghan Pakhsa walls typically range from 400 to 800 mm in thickness, substantially exceeding the ≤300 mm walls tested in most laboratory studies in Latin America, South Asia, and New Zealand [48,50,53,56,68,70,71,72]. This increased thickness produces different stiffness and mass characteristics, alters crack trajectories, and heightens out-of-plane vulnerability. The associated mass amplification increases seismic inertia, while the larger cross-section modifies shear and flexural stress paths, making Afghan walls prone to both diagonal cracking and sudden out-of-plane instability.

Traditional Afghan flat roofs, composed of round timber beams placed at intervals, impose concentrated vertical loads on supporting walls. In contrast, most experiments simulate gravity through uniform axial compression [62,63,64,65,69,73], which does not capture the discrete load paths or stress concentrations produced by timber beams. Concentrated roof loads can induce local crushing, alter crack initiation sequences, and intensify shaking-induced damage—particularly in dwellings lacking collar or ring beams, which are uncommon in vernacular Afghan construction. This mismatch limits the direct applicability of experimental capacity measurements to Afghan building response.

A further divergence relates to material availability. Codes such as IS 13827 [80], IAEE [81], and the Afghan 2003 guidelines [24] assume the use of bamboo or cane for reinforcement. However, bamboo is scarce in Afghanistan, and installing cane belts within existing walls is impractical for retrofitting. In contrast, several reinforcement systems validated experimentally—including polymer meshes [55,56,59], geogrids [55,62,68], nylon rope meshes [71,72], TRM overlays [73,74], and timber planks or grids [65,69]—are feasible and locally obtainable. These systems provide substantial increases in lateral strength, ductility, and energy dissipation, yet none are reflected in current Afghan guidance. Their absence restricts the adoption of reinforcement methods that have proven both effective and compatible with low-resource contexts.

The 2003 Afghan guidelines [24], adapted largely from Indian practice, do not address Pakhsa construction, despite its prevalence compared to adobe construction. They also omit treatment of concentrated roof loading, anchorage detailing, and wall-intersection strengthening, even though experimental evidence consistently shows that corners and intersections are among the most failure-prone zones [52,60,68,72]. Equally absent are provisions for retrofitting damaged walls. Modern studies show that systems such as geogrids and TRM can significantly enhance the residual capacity of cracked earthen walls, although without restoring original stiffness [56,73,74].

Another critical gap lies in seismic hazard classification. Afghanistan’s current zoning, embedded in the 2003 guidelines, precedes contemporary PSHA-based hazard assessments. Recent models indicate significantly higher shaking intensities in many regions, meaning that permissible wall geometries, reinforcement requirements, and performance objectives in the existing guidelines underestimate actual demands. Reliable interpretation of experimental improvements—whether in drift capacity, strength, or collapse prevention—requires alignment with an updated hazard framework.

Taken together, these discrepancies highlight that foreign standards and experimental findings should be adapted and verified before being applied to Afghanistan. A revised national guideline should draw on reinforcement strategies demonstrated to be effective internationally, but their suitability for Afghan adobe and Pakhsa construction should be confirmed through context-specific experimental testing and/or numerical modelling that reflects local wall geometries, mass characteristics, roof-wall interaction, and boundary conditions such as concentrated roof loads and corner behaviour. Through such validation and adaptation, seismic provisions can be appropriately tailored to reduce the vulnerability of Afghanistan’s earthen building stock.

7.5. Toward Updated Guidelines for Earthen Construction

The synthesis of experimental results and international standards points to several priorities for updating Afghan earthquake-resistant earthen construction guidelines. Reinforcement systems should be selected based on demonstrated seismic effectiveness and local availability. Experimental studies show that geogrids, welded wire meshes, nylon rope nets, PP/PE meshes, timber confinement, and TRM systems [52,55,56,62,69,70,71,72,73,74] consistently improve lateral strength, drift capacity, hysteretic stability, and out-of-plane resistance. These materials and techniques represent realistic options for Afghan construction, unlike bamboo-based systems prevalent in other countries.

Anchorage must be explicitly addressed. Studies emphasise the importance of securing reinforcement for foundations and collar beams to reduce rocking and prevent wall-foundation separation [48,50,55,65,68,70]. Updated guidelines should therefore specify anchor spacing, embedment depth, and connection detailing for both new construction and retrofitting of existing earthen walls.

Given the prevalence of thick adobe and Pakhsa walls, the guidelines should include provisions tailored to high-mass, low-slenderness configurations. These should consider altered failure modes, higher inertial demands, and the susceptibility of thick walls to out-of-plane rocking. Similarly, explicit treatment of roof-wall interaction is required, incorporating roof diaphragm effects and accounting for concentrated loads from timber beams—features not currently represented in Afghanistan’s guidelines [24].