Abstract

Basic magnesium sulfate cement (BMSC) exhibits rapid setting, early strength development, high ultimate strength, and good durability, making it a promising construction material for the extreme environments of Mars. Following the principle of in situ resource utilization (ISRU), this study employs the Martian regolith simulant NUAA-1M, developed by Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, as both a mineral admixture and aggregate to prepare Martian basic magnesium sulfate cement (M-BMSC) and Martian basic magnesium sulfate cement concrete (M-BMSCC). The effects of NUAA-1M fines on the setting time, compressive strength, hydration heat evolution, hydration products, microstructure, and pore structure of M-BMSC were systematically investigated. Moreover, the fundamental physical and mechanical properties of M-BMSCC incorporating NUAA-1M as an aggregate were evaluated, and an empirical correlation model was established between its compressive strength (fcu), flexural strength (ft), and splitting tensile strength (fsp). Results indicate that with increasing NUAA-1M fines content, the setting time of M-BMSC was prolonged, while its compressive strength initially increased and then decreased. The incorporation of NUAA-1M fines modified the hydration process and phase assemblage of M-BMSC, promoting the formation of magnesium (alumino)silicate hydrate (M-(A)-S-H) gels and refining the pore structure. Hydration monitoring within 24 h confirmed the rapid hydration characteristics of M-BMSC, demonstrating its suitability for Martian conditions. M-BMSCC exhibited excellent early- and high-strength performance, achieving a 28-day compressive strength of 59.2 MPa at a binder-to-aggregate ratio of 2:1, corresponding to a total NUAA-1M content of 84.75% in the mixture. This work provides a novel ISRU-based material strategy for the construction of Martian bases and infrastructure.

1. Introduction

In 1960, the Soviet Union launched Mars 1960A, the world’s first Mars probe [1], marking the beginning of the era of Martian exploration. As the planet most similar to Earth in the solar system, Mars possesses several conditions necessary for life and is considered a potential destination for future human colonization [2]. With the rapid advancement of space technology, numerous countries and organizations—including the United States, Russia, the European Space Agency (ESA), Japan, and India—have successively formulated and implemented Mars exploration programs [3]. China also initiated its first Mars exploration mission in 2016, with the Tianwen-1 probe successfully landing on Mars in 2021 [4]. As various “manned mission to Mars” programs advance, the construction of permanent Martian bases has become an urgent priority.

Concrete is regarded as an ideal material for Martian base construction and a fundamental resource for extraterrestrial infrastructure [5]. However, due to the immense distance between Earth and Mars, transporting construction materials from Earth would be prohibitively expensive and impractical. Therefore, in situ resource utilization (ISRU) has become the core strategy for developing Martian construction materials [3]. Considerable progress has been achieved in the development of Martian concrete systems. For instance, magnesium silicate–based concretes exhibit high strength and low energy consumption, but their preparation depends on superplasticizers that cannot be synthesized in situ, and the availability of reactive SiO2 on Mars remains uncertain [5,6]. Alkali-activated cements, though mature and resource-efficient on Earth, face challenges under Martian conditions due to limited resource accessibility and slow reaction kinetics [7,8].

Multisource remote sensing has identified various hydrated minerals on Mars, including phyllosilicates, hydrated silica, sulfates, and carbonates [9]. Spectral data from ESA’s Mars Express OMEGA instrument [10] and NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter CRISM spectrometer [11] confirm the widespread presence of hydrated sulfates such as gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O) and hydrated magnesium sulfates (MgSO4·XH2O) [12,13,14,15]. Studies have shown that MgSO4·XH2O decomposes at high temperature to yield MgO and SO3, and that introducing reducing agents (e.g., CO or H2) can significantly lower the decomposition temperature, thereby reducing energy demand while producing highly reactive MgO [16]. The byproduct SO3 can be further converted into sulfuric acid (H2SO4) [17], enabling efficient resource recycling.

Another abundant Martian mineral, olivine ((Mg,Fe)2SiO4), can be chemically converted into magnesium hydroxide (Mg(OH)2) and hydrogen gas (H2) [6,18]. Upon calcination, Mg(OH)2 produces MgO and H2O [19]; the generated H2 can serve both as a reductant for MgSO4·XH2O decomposition and as a potential energy carrier for Martian habitats. Magnesium oxysulfate cement (MOS), composed of reactive MgO, MgSO4·XH2O, and H2O, belongs to the MgO–MgSO4–H2O ternary system and primarily forms the hydration product 3Mg(OH)2·MgSO4·8H2O (3·1·8 phase) [20,21]. These findings confirm that Martian surface materials can provide abundant feedstock for MOS preparation, though its relatively low strength limits engineering applications.

The Martian surface is covered by weathered materials collectively referred to as regolith [22], whose bulk composition closely resembles terrestrial basalt [23,24]. In situ analyses by the Spirit [25], Opportunity [26], and Curiosity [27] rovers revealed, as summarized in Table 1, that Martian soil contains appreciable P2O5 and phosphate minerals such as apatite (Ca5(PO4)3(OH,F,Cl)) [28,29,30]. The coexistence of these phosphates with H2SO4 offers the potential to synthesize phosphoric acid (H3PO4) [31]. More importantly, H3PO4 can act as a modifier for MOS to form basic magnesium sulfate cement (BMSC) [32], in which the primary hydration product transforms into 5Mg(OH)2·MgSO4·7H2O (5·1·7 phase) with significantly improved mechanical strength [33]. As a novel and environmentally friendly binder [34], BMSC exhibits rapid setting, early and high strength, and superior durability [35,36,37,38,39,40], making it a promising candidate for Martian infrastructure.

Water is an indispensable component in the preparation of cementitious materials. The water released during the thermal decomposition processes described above can be collected and reused. Moreover, long-term observations have confirmed the presence of multiple forms of water on Mars—including surface erosion traces, subsurface ice layers, and subglacial liquid water—providing several feasible sources for ISRU-based water utilization [5,41,42,43].

Although actual Martian soil samples have not yet been returned to Earth, coordinated analyses from rovers and orbital instruments have enabled detailed characterization of Martian regolith. Consequently, Martian regolith simulants are synthesized and tested on Earth to support materials research for planetary construction [44,45]. Based on mission data from successive Mars explorers, various representative simulants have been developed, such as the MMS series derived from Saddleback basalt in California’s Mojave Desert [46], the MGS-1S simulant developed by the University of Central Florida based on Curiosity’s observations of aeolian deposits in Gale Crater’s Rocknest region [45], and the NEU Mars-1 simulant produced from basalt of the Chahar Volcano Group in Inner Mongolia, China [47]. As summarized in Table 1, these simulants primarily consist of SiO2, Al2O3, CaO, and MgO, effectively replicating the bulk composition of Martian surface materials.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of NUAA-1M compared with other Martian regolith simulants and in situ soils analyzed by Spirit, Curiosity, and Opportunity.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of NUAA-1M compared with other Martian regolith simulants and in situ soils analyzed by Spirit, Curiosity, and Opportunity.

| Compound | Spirit [25] | Opportunity [26] | Curiosity [27] | MGS-1S [45] | NEU Mars-1 [47] | MMS [46] | NUAA-1M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 45.8 | 43.8 | 42.88 | 29.29 | 43.94 | 49.4 | 42.93 |

| TiO2 | 0.81 | 1.08 | 1.19 | 0.27 | 2.7 | 1.09 | 2.72 |

| Al2O3 | 10 | 8.55 | 9.43 | 6.37 | 17.8 | 17.1 | 14.88 |

| Cr2O3 | 0.35 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.13 | - | 0.05 | - |

| Fe2O3 | - | - | - | - | 15.61 | 10.87 | 16.01 |

| FeO | 15.8 | 22.33 | 19.19 | 11.25 | - | - | - |

| MnO | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.64 |

| MgO | 9.3 | 7.05 | 8.69 | 16.22 | 2.13 | 6.08 | 4.51 |

| CaO | 6.1 | 6.67 | 7.28 | 14.81 | 7.82 | 10.45 | 8.92 |

| Na2O | 3.3 | 1.6 | 2.72 | 2.11 | 5.58 | 3.08 | 4.17 |

| K2O | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 2.96 | 0.48 | 2.51 |

| P2O5 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.94 | 0.32 | 0.99 | 0.17 | 0.39 |

| SO3 | 5.82 | 5.57 | 5.45 | 18.71 | 0.06 | 0.1 | - |

| Cl | 0.53 | 0.44 | 0.69 | - | 0.07 | - | - |

| LOl | - | - | - | - | - | 3.39 | - |

| Total | 99.37 | 99.18 | 99.85 | 100 | 99.84 | 99.24 | 97.68 |

Note: “-” denotes no data available.

In this study, adhering to the Martian ISRU concept, BMSC was selected as the binder, as its key precursors—reactive MgO, MgSO4·H2O, and H3PO4—can all be synthesized entirely in situ on Mars. The NUAA-1M simulant developed by Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics was employed as a mineral admixture in powdered form, and its effects on the mechanical enhancement, hydration evolution, pore refinement, and hydration kinetics of Martian BMSC (M-BMSC) were systematically examined using X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP), and isothermal calorimetry. Furthermore, NUAA-1M in the 0.15–2.36 mm particle size range was utilized as aggregate to design Martian BMSC concrete (M-BMSCC) with various mix ratios. The optimal aggregate proportion was determined through mechanical testing, and an empirical relationship among the compressive strength (fcu), flexural strength (ft), and splitting tensile strength (fsp) was established. This study aims to advance ISRU-based construction technologies for Mars, providing both theoretical foundations and engineering guidance for future extraterrestrial infrastructure development.

2. Materials and Methods

To systematically investigate the influence of NUAA-1M fines on the performance of BMSC, dosage levels of 0%, 100%, 150%, 200%, 250%, and 300% were adopted to examine the evolution of its mechanical properties and microstructural characteristics. Furthermore, NUAA-1M fines were used as aggregates in M-BMSCC, and mixes with binder–aggregate ratios of 1:1.75, 1:1.2, and 1:2.25 were prepared to evaluate the fundamental mechanical properties of M-BMSCC. Finally, based on the experimental results, quantitative models were developed to correlate the compressive strength (fcu) of M-BMSCC with its flexural strength (ft) and splitting tensile strength (fsp).

2.1. Raw Materials

2.1.1. MgO, MgSO4·H2O, and Additives

The reactive MgO used in this study was supplied by Hebei Meisheng Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shijiazhuang, China), with a purity of 98.54% and a loss on ignition of 1.03%. The active MgO content, determined by the hydration method, was approximately 87%, and the specific surface area measured by the BET method was 43.78 m2/g. Industrial-grade MgSO4·H2O (purity 99.0%) was obtained from Jinan Yuanbo Chemical Co., Ltd. (Jinan, China). Phosphoric acid (H3PO4, analytical grade) was purchased from Xilong Scientific Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.1.2. Martian Regolith Simulant

The Martian regolith simulant (NUAA-1M) was developed by Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics using basalts from the Huinan volcanic field, Tonghua, Jilin Province, China. NUAA-1M fines and aggregates were obtained through crushing and grinding processes. BET analysis showed that the specific surface area of NUAA-1M fines was 2.03 m2/g. Water absorption tests indicated 1 h saturated absorption rates of 18.57% for fines and 13.5% for aggregates.

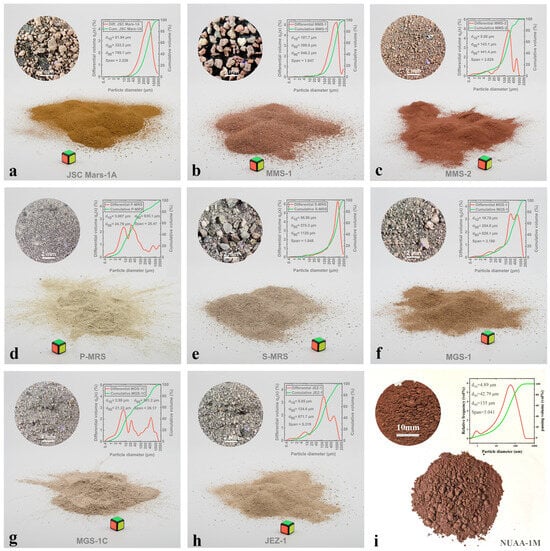

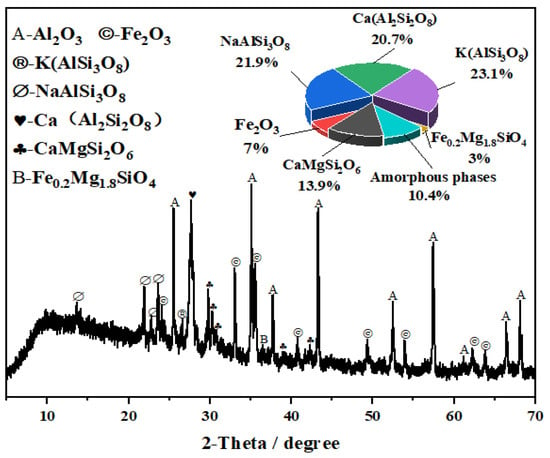

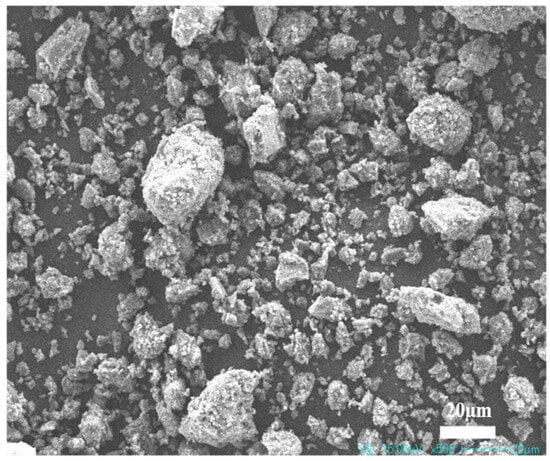

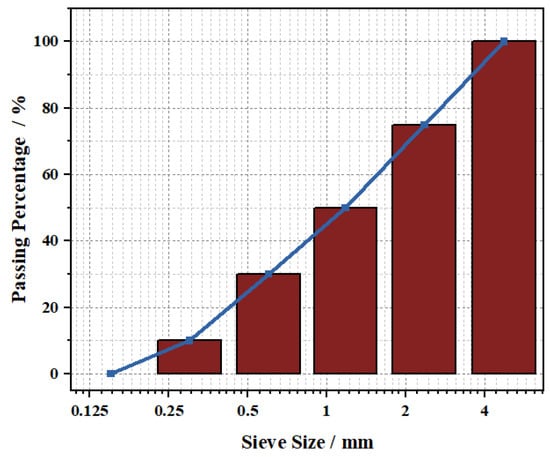

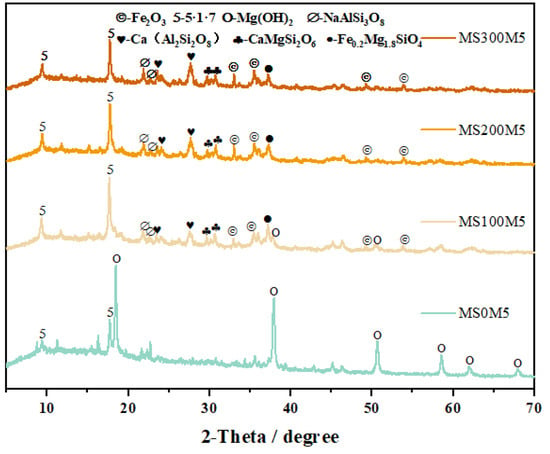

The macroscopic morphology and particle size distribution of NUAA-1M fines, compared with other Martian regolith simulants, are shown in Figure 1. The XRD pattern and microstructure are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3, respectively. XRD analysis revealed that NUAA-1M is primarily composed of anorthite (Ca(Al2Si2O8)), albite (NaAlSi3O8), orthoclase (K(AlSi3O8)), diopside (CaMgSi2O6), olivine (Fe0.2Mg1.8SiO4), and hematite (Fe2O3), with a detectable amorphous phase. These mineralogical characteristics closely correspond to those of actual Martian regolith [27,48,49]. The detailed chemical composition of NUAA-1M is listed in Table 1. Comparison with in situ measurements obtained by Mars missions and with other representative simulants shows that NUAA-1M exhibits good consistency with real Martian soil in terms of the contents of major oxides such as SiO2 and Al2O3 [45,46], although slight differences are observed in the contents of Fe2O3, FeO, and SO3, as summarized in Table 1. Figure 4 and Figure 5 further illustrate the macroscopic appearance and particle size distribution of NUAA-1M aggregates, respectively.

Figure 1.

Macroscopic morphology and particle size distribution of Martian regolith simulants (subfigures (a–h) adapted from David Karl et al. [50]; subfigure (i) shows the morphology and particle size distribution of NUAA-1M; The green line represents the cumulative distribution, and the red line represents the differential distribution).

Figure 2.

XRD pattern of NUAA-1M.

Figure 3.

SEM images of NUAA-1M fines.

Figure 4.

Macroscopic appearance of NUAA-1M aggregate.

Figure 5.

Particle size distribution of NUAA-1M aggregate.

2.2. Mix Design and Preparation of M-BMSC and M-BMSCC

2.2.1. Mix Design and Preparation of M-BMSC

This study aims to systematically evaluate the effects of NUAA-1M fines on the microstructure and mechanical performance of M-BMSC. The mix design was developed with the objective of minimizing the consumption of MgO and MgSO4·H2O. Based on preliminary experimental results and previous studies, the mix proportions listed in Table 2 were determined [38,39,40,51,52]. The main parameters were set as follows: the molar ratio of MgO to MgSO4·H2O was fixed at 5, the water to solid ratio (W/S) was 0.5, and the dosage of H3PO4 was fixed at 1% by mass of MgO. The content of NUAA-1M fines ranged from 0% to 69.2% of the total mass of the M-BMSC system, corresponding to 0 to 3 times the mass of MgO. For clarity, Table 2 also provides the molar ratios of MgO, MgSO4, and H2O after deducting the 1 h saturated water absorption of NUAA-1M fines, as well as the mass fraction of MgO in the cementitious materials.

Table 2.

Mix design of M-BMSC.

The preparation procedure of M-BMSC was as follows: phosphoric acid (H3PO4) was first dissolved in water and stirred to obtain a homogeneous solution. MgO, MgSO4·H2O, and NUAA-1M fines were then premixed uniformly in a mortar. The solution was slowly added to the dry mixture under stirring to form a slurry. The slurry was cast into 20 mm × 20 mm × 20 mm steel molds, vibrated to remove entrapped air, and cured at (20 ± 5) °C and a relative humidity of (60 ± 5)% for 12 h before demolding. The molds and M-BMSC specimens are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

M-BMSC molds and specimens.

2.2.2. Mix Design and Preparation of M-BMSCC

The mix design of M-BMSCC is shown in Table 3, where the aggregate-to-binder mass ratio (A/B) was varied to determine the optimal proportion. The reference binder used was M-BMSC with the baseline mix MS200M5. The net water-to-cement ratio (W/C) was fixed at 0.25, and additional water was adjusted according to the 1 h saturated water absorption of NUAA-1M aggregates.

Table 3.

Mix proportions of M-BMSCC.

The preparation procedure of M-BMSCC was as follows: phosphoric acid (H3PO4) was first dissolved in water with stirring until complete dissolution. The components of M-BMSC were weighed according to the MS200M5 mix, dry-mixed uniformly, and then placed in a mixer. The H3PO4 aqueous solution was added, followed by thorough mixing, after which NUAA-1M aggregates were incorporated and mixing continued until a homogeneous mixture was obtained. The fresh mix was cast into 40 mm × 40 mm × 160 mm steel molds, vibrated to ensure compaction, and cured at (20 ± 5) °C and a relative humidity of (60 ± 5)% for 24 h before demolding. The molds and M-BMSCC specimens are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

M-BMSCC molds and specimens.

2.3. Testing Methods

2.3.1. Setting Time

The setting time of M-BMSC was determined using a Vicat apparatus in accordance with the Chinese National Standard GB/T 1346-2001 [53] “Test methods for water requirement of normal consistency, setting time and soundness of Portland cement”.

2.3.2. Physical and Mechanical Properties

Compressive Strength of M-BMSC and M-BMSCC

The compressive strength of M-BMSC and M-BMSCC specimens was tested in accordance with the Chinese National Standard GB/T 17671-2021 [54] “Test method of cement mortar strength (ISO method)”. The loading rates were 0.3 kN/s for M-BMSC and 2.4 kN/s for M-BMSCC, respectively. The compressive strength was calculated using Equation (1).

where is the compressive strength (MPa), is the failure load (N), and is the loaded area of the specimen (mm2).

Flexural Strength of M-BMSCC

The flexural strength of M-BMSCC was tested in accordance with the Chinese National Standard GB/T 17671-2021 [54] “Test method of cement mortar strength (ISO method)”, using a loading rate of 0.05 MPa/s. The flexural strength was calculated according to Equation (2):

where is the flexural strength (MPa), is the failure load (N), is the span between supports (mm), and and are the width and height of the specimen cross-section (mm), respectively.

Splitting Tensile Strength of M-BMSCC

The splitting tensile strength test of M-BMSCC was conducted in accordance with the Chinese National Standard GB/T 50081-2019 [55] “Standard for test methods of concrete physical and mechanical properties”, using a loading rate of 0.05 MPa/s. The splitting tensile strength was calculated according to Equation (3):

where is the splitting tensile strength (MPa), is the failure load (N), and is the splitting surface area of the specimen (mm2).

2.3.3. Phase Composition and Microstructural Characterization

X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

XRD analysis was conducted using a D/max-2500PC diffractometer (Tokyo, Japan) with a Cu/Kα radiation source at 30 kV. The scanning range was 5–70° (2θ). Quantitative phase analysis was performed with full-pattern fitting using Topas 5.0 software. For samples requiring an internal standard, α-Al2O3 was added at a mass ratio of 7:3 (sample:α-Al2O3). The mixture was ground into fine powder, passed through a 75 μm (200 mesh) sieve, and prepared for testing.

Microstructural Analysis (SEM-EDS)

Bulk samples were gold-coated under vacuum using an ETD-2000 ion sputter coater (Boyuan Micro-Nano Technology Co., Beijing, China). Microstructural observations were carried out with an EPMA-8050G electron probe microanalyzer (EPMA, Kyoto, Japan). Elemental analysis of micro-areas was performed using an INCA Energy energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS, Oxford, UK).

Isothermal Calorimetry

The hydration heat release rate was measured at 20 °C using a Calmetrix I-Cal 4000 HPC isothermal calorimeter (Shanghai, China) with four channels.

Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry (MIP)

Pore structure characteristics were measured using an AutoPore IV 9500 high-performance automatic mercury porosimeter (Micromeritics, Shanghai, China). The pore size range was 0.003–1000 μm, with a maximum pressure of 208 MPa and a contact angle of 130°.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fundamental Physical and Mechanical Properties of M-BMSC

3.1.1. Effect of NUAA-1M Fines on the Setting Time of M-BMSC

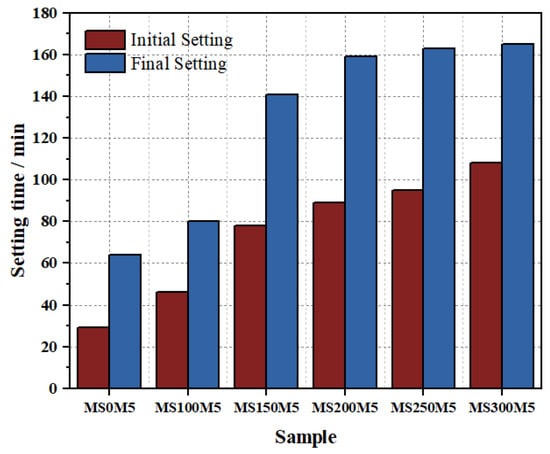

Figure 8 shows the relationship between the setting time of M-BMSC paste (W/S = 0.5) and the dosage of NUAA-1M fines. The reference paste, MS0M5, exhibited initial and final setting times of only 29 min and 64 min, respectively. With increasing NUAA-1M content, the setting time of M-BMSC paste was progressively prolonged. When MS/M = 1.5, the initial and final setting times reached 78 min and 141 min, representing increases of 169% and 120%, respectively. Beyond MS/M = 1.5, the rate of extension slowed, with initial setting times of 89 min and 108 min and final setting times of 159 min and 165 min at MS/M = 2 and 3, respectively.

Figure 8.

Effect of NUAA-1M dosage on the setting time of M-BMSC paste.

3.1.2. Effect of NUAA-1M Fines on Compressive Strength and Strength Contribution of M-BMSC

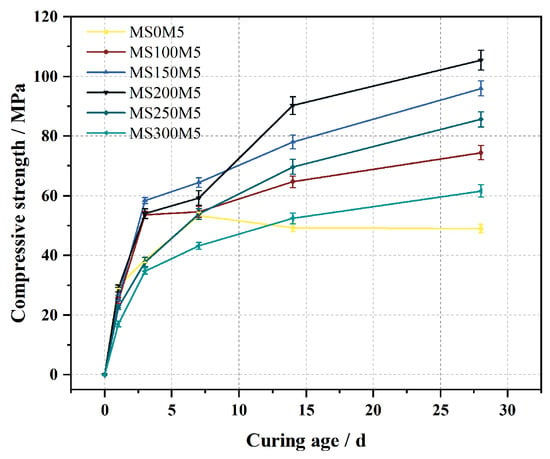

Figure 9 shows the effect of different NUAA-1M fines contents on the compressive strength of M-BMSC. After 1 day of curing, the compressive strengths of MS0M5, MS100M5, MS150M5, MS200M5, MS250M5, and MS300M5 were 29.6 MPa, 24.9 MPa, 25.7 MPa, 29.0 MPa, 22.6 MPa, and 17.0 MPa, respectively, with MS0M5 exhibiting the highest strength. Due to the rapid hydration of highly reactive MgO, the hydration process of MS0M5 was nearly completed at the early stage, and its strength tended to stabilize after 7 days.

Figure 9.

Effect of NUAA-1M dosage on the compressive strength of M-BMSC.

After 3 days of curing, the compressive strengths of MS100M5, MS150M5, and MS200M5 exceeded that of the reference group MS0M5, increasing by 39.3%, 51.7%, and 40.2%, respectively. During the 7–14 day curing period, the compressive strengths of MS250M5 and MS300M5 also surpassed that of MS0M5. By 28 days, MS0M5 exhibited the lowest compressive strength of 49.1 MPa, while MS100M5, MS150M5, MS200M5, MS250M5, and MS300M5 reached 74.4 MPa, 95.9 MPa, 105.4 MPa, 85.6 MPa, and 61.6 MPa, respectively, corresponding to increases of 51.7%, 95.6%, 114.8%, 74.5%, and 25.6% compared with MS0M5.

With the extension of curing age, the compressive strength of all M-BMSC specimens containing NUAA-1M fines continued to increase, indicating that the pozzolanic reactivity of NUAA-1M fines gradually developed during hydration. The reaction facilitated the formation of magnesium (alumino)silicate hydrate (M-(A)-S-H) gels, which enhanced the microstructural compactness and contributed to strength development [56]. Overall, the compressive strength of M-BMSC increased first and then decreased with the increase in NUAA-1M fines content, with MS200M5 consistently maintaining the highest compressive strength after 7 days.

These results indicate that the high strength of M-BMSC primarily originates from the filler effect of NUAA-1M fines and their secondary hydration reaction with the BMSC matrix to form M-(A)-S-H gels. The synergistic action of these two mechanisms results in MS200M5 (MS/M = 2) exhibiting the optimal compressive strength among all formulations.

To evaluate the strength contribution effect of NUAA-1M fines in the M-BMSC system, the method proposed by Pu [57] was adopted. First, the relative strength contribution value of NUAA-1M was calculated according to Equation (4):

where is the relative strength contribution (MPa), is the measured compressive strength (MPa), and is the mass percentage of MgO and MgSO4·H2O in the M-BMSC system. For M-BMSC without NUAA-1M (MS0M5), = 100.

Subsequently, the strength contribution rate of NUAA-1M to M-BMSC was determined using Equations (5) and (6):

where is the specific strength (MPa), is the relative strength contribution of M-BMSC (MPa), is the relative strength contribution of M-BMSC without NUAA-1M fines (MPa), and is the strength contribution rate of NUAA-1M fines in the M-BMSC system.

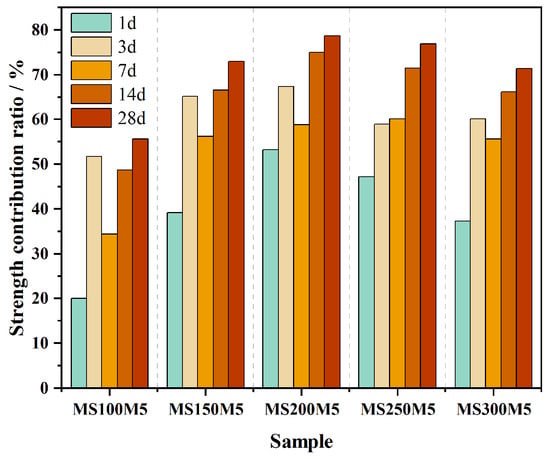

As shown in Figure 10, the strength contribution rates of all mixtures (MS100M5–MS300M5) remained positive across all curing ages (1–28 d), ranging from 20.04% to 78.71%, indicating that the incorporation of NUAA-1M fines provided a continuous and stable enhancement effect on the M-BMSC system. In terms of trends, the contribution rates at 1, 3, 7, 14, and 28 d all exhibited an initial increase followed by a decrease with increasing NUAA-1M dosage. At 1 d, the contribution rates of NUAA-1M fines in MS100M5, MS150M5, MS200M5, MS250M5, and MS300M5 were 20.04%, 39.17%, 53.27%, 47.20%, and 37.30%, respectively, demonstrating a pronounced early-age strengthening effect, which can be primarily attributed to the physical filling action of NUAA-1M fines.

Figure 10.

Strength contribution ratios of NUAA-1M fines in the M-BMSC system at different curing ages and dosages.

With extended curing (3–28 d), the contribution rates of all mixtures continued to increase, reaching 55.66%, 72.94%, 78.71%, 76.91%, and 71.34% at 28 d, respectively. This sustained enhancement is mainly ascribed to the pozzolanic reaction of NUAA-1M fines and the reinforcing effect of the resulting M-(A)-S-H gels. Among the mixtures, MS200M5 exhibited the highest contribution rate, surpassing MS100M5, MS150M5, MS250M5, and MS300M5 by 41.40%, 7.91%, 2.34%, and 10.34%, respectively, indicating that this mix achieved the optimal synergy between filler and pozzolanic effects, thereby maximizing the strengthening potential of NUAA-1M fines.

It is noteworthy that even though MS300M5 had the highest NUAA-1M content, its 28 d contribution rate still reached 71.34%. This suggests that a substantial increase in NUAA-1M dosage can be achieved while maintaining adequate mechanical performance, which aligns well with the ISRU design philosophy.

3.2. Hydration Heat and Hydration Products of M-BMSC

3.2.1. Hydration Heat Evolution of M-BMSC

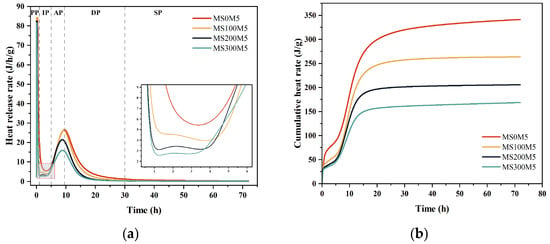

Figure 11 illustrates the effects of different NUAA-1M fines dosages on the heat release rate and cumulative hydration heat of M-BMSC. The hydration of BMSC can be divided into five stages: the pre-induction period (PP), induction period (IP), acceleration period (AP), deceleration period (DP), and steady period (SP) [58].

Figure 11.

Hydration heat evolution curves of M-BMSC with different NUAA-1M dosages: (a) heat flow curves; (b) cumulative heat release curves.

During the pre-induction period (PP), corresponding to the first exothermic peak, MgO and MgSO4·H2O rapidly undergo hydrolysis and release heat. The hydrolysis of MgO proceeds according to Equation (7) [59], forming surface-adsorbed hydrolysis species [Mg(OH)(H2O)x]+ and OH−. With increasing NUAA-1M fines content, the proportions of MgO and MgSO4·H2O in the M-BMSC paste decrease, leading to a corresponding reduction in the heat released from hydration and dissolution.

In the induction period (IP), Table 4 shows that the reference mixture MS0M5 exhibits an extremely short induction time of only 0.13 h. This behavior is attributed to the accumulation of highly reactive MgO in the H3PO4-modified M-BMSC system, where the surface “hydration shell” is unstable. The hydrolysis species [Mg(OH)(H2O)x]+ rapidly react with OH− to form Mg(OH)2 with very low solubility, as described by Equation (8) [58,60], thereby driving the system quickly into the acceleration stage. Upon incorporation of NUAA-1M fines, the induction period is markedly prolonged: it increases to 2.57 h, 2.50 h, and 2.00 h for MS100M5, MS200M5, and MS300M5, respectively. This extension indicates that NUAA-1M fines partially replace MgO and MgSO4·H2O, reducing the relative MgO content (Table 2) and improving the dispersion of MgO, which in turn facilitates the formation of the 5·1·7 phase [61,62]. Notably, with further increases in fines content, the induction period gradually shortens (from 2.57 h to 2.00 h). Combined with the data in Table 2, this trend can be attributed to the increasing molar ratio of H2O in the system, which promotes the dissolution of MgO and MgSO4·H2O and thus shortens the induction stage.

Table 4.

Hydration heat evolution of M-BMSC systems incorporating different dosages of NUAA-1M fines.

During the acceleration period (AP), corresponding to the second exothermic peak, ionic species in the BMSC paste—such as [Mg(OH)(H2O)x]+, Mg2+, SO42−, and OH−—react to form the 5·1·7 phase with the release of hydration heat, as described by Equation (9) [59]. With increasing NUAA-1M fines content, the duration of the acceleration period extends to 4.95 h, 5.03 h, and 5.57 h for MS100M5, MS200M5, and MS300M5, respectively. This behavior is mainly due to the increased H2O content and the reduced SO42− concentration in the M-BMSC system, which delays the formation of the 5·1·7 phase and results in a progressive prolongation of the acceleration stage.

Moreover, as NUAA-1M fines replace MgO and MgSO4·H2O, the maximum heat release rate of MS100M5, MS200M5, and MS300M5 decreases by 1.24%, 19.13%, and 39.9%, respectively, compared with MS0M5. The total cumulative heat release is also reduced by 22.74%, 39.7%, and 50.57%, respectively. Overall, increasing the NUAA-1M fines content leads to a gradual decrease in total hydration heat, a delayed appearance of the exothermic peaks, and lower peak intensities, indicating that NUAA-1M fines effectively regulate the hydration kinetics of the BMSC system.

3.2.2. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis of Hydration Products

Figure 12 presents the phase assemblages of M-BMSC pastes after 28 d of curing. In the reference group MS0M5, the hydration products were dominated by Mg(OH)2, with only minor amounts of the 5·1·7 phase. Notably, with the incorporation and increasing dosage of NUAA-1M fines, the hydration products in most mixtures transformed almost entirely into the 5·1·7 phase, except for MS100M5, in which trace Mg(OH)2 remained. This result is consistent with the calorimetric findings, and no distinct new crystalline phases were detected.

Figure 12.

XRD patterns of M-BMSC with different NUAA-1M dosages.

However, when the NUAA-1M dosage was excessively high, the amounts of MgO and MgSO4·H2O per unit volume decreased, leading to a reduction in the relative formation of the 5·1·7 phase. This was reflected in the gradual weakening of the characteristic diffraction peak of the 5·1·7 phase at 17.86° with higher NUAA-1M contents. Such phase evolution also provides a clear explanation for the earlier observation that the MS/M = 2 (MS200M5) mixture exhibited the highest compressive strength.

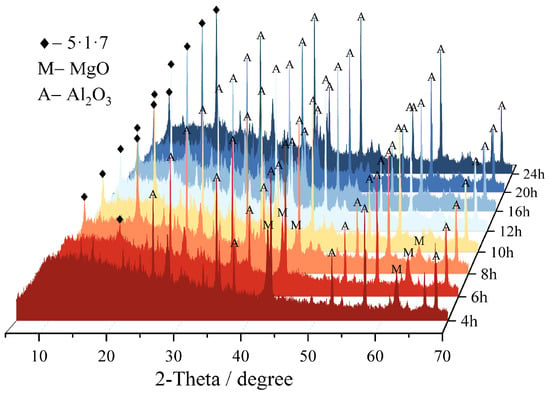

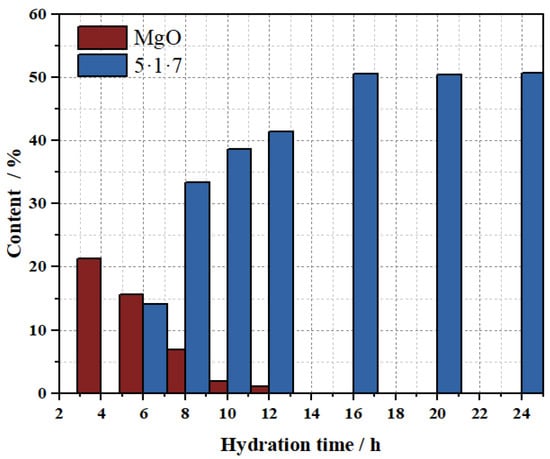

Figure 13 illustrates the phase evolution of MS200M5 within 24 h, with quantitative analysis performed using Topas 5.0 software (results shown in Figure 14 and Table 5. The intensity of the characteristic MgO peaks continuously decreased between 4–8 h, indicating progressive consumption, and by 10 h MgO was nearly fully reacted, with only 1.86% remaining. Meanwhile, the characteristic diffraction peaks of the 5·1·7 phase emerged at 6 h and intensified markedly between 6–10 h, signifying rapid formation during this period. After 16 h, the peak intensity stabilized, and the content of the 5·1·7 phase reached its maximum value of 50.57%, suggesting that its formation reaction was essentially complete. The above results further confirm that the M-BMSC system exhibits rapid hydration characteristics.

Figure 13.

24 h hydration-tracking XRD patterns of MS200M5.

Figure 14.

Phase fractions of MgO and 5·1·7 in the MS200M5 system.

Table 5.

Phase composition of MS200M5 analyzed by Topas 5.0.

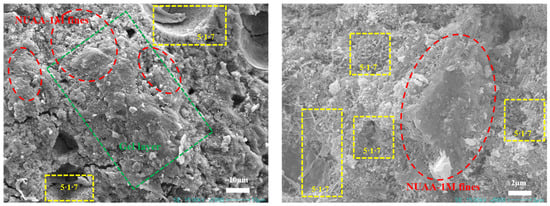

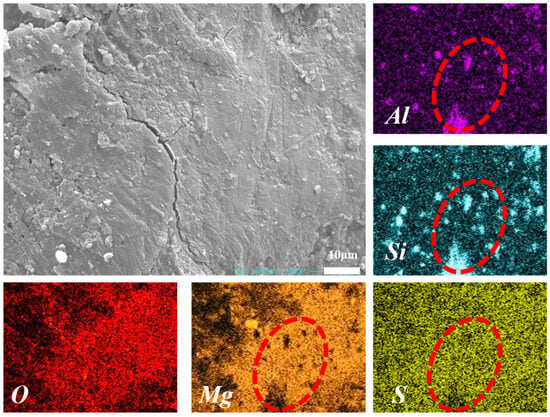

3.3. Microstructural Analysis by SEM-EDS

Figure 15 shows the SEM image of MS200M5 after 28 d of curing. Needle- and rod-like 5·1·7 phases were observed to interweave into a skeleton, forming the primary microstructural framework of MS200M5. Notably, NUAA-1M fines were not only closely bonded to the M-BMSC matrix but also coated with a dense gel layer, suggesting possible reactions between surface-active species of NUAA-1M and the M-BMSC binder. To further investigate the composition of this gel layer, elemental mapping was performed Figure 16. The results revealed a uniform distribution of Mg and S, confirming the abundant formation of the 5·1·7 phase, consistent with XRD analysis. Regions enriched in Si and Al corresponded to unreacted or inert NUAA-1M particles. At the particle–matrix interfaces, overlapping signals of Mg, S, Si, and Al were observed, with partial diffusion of Si and Al into the cement matrix.

Figure 15.

SEM image of M-BMSC (MS200M5).

Figure 16.

SEM image and elemental mapping of M-BMSC (MS200M5).

Previous studies have shown that reactive components in pozzolanic materials undergo hydrolysis in alkaline cement pastes, forming gel-like products [63]. It has been reported that reactive SiO2 in silica fume reacts with Mg(OH)2 in BMSC to produce magnesium silicate hydrate (M-S-H) gels with a talc-like structure [59]. The reaction between amorphous SiO2 and Mg(OH)2 to form M-S-H gels has also been repeatedly confirmed [56,64]. Moreover, Al can be incorporated into the M-S-H structure, forming magnesium aluminosilicate hydrate (M-A-S-H) gels [65]. In the H3PO4-modified BMSC system used in this study, the pH was maintained between 9 and 11, providing the necessary alkaline environment for gel formation [66,67]. The active Al present in NUAA-1M fines may also participate in the reactions, facilitating the formation of M-A-S-H gels. Zhang et al. from our research group have further confirmed, through SEM-EDS, 29Si and 27Al magic-angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance (MAS NMR), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), that the 5·1·n phase, along with minor amounts of low-crystallinity 5·1·7 phase and Mg(OH)2 present in BMSC, can undergo volcanic ash reactions with active silicon and aluminum sources from the simulant regolith glass phase, leading to the formation of M-(A-)S-H gels. These findings have been compiled into a complete manuscript, which is currently under submission for publication.

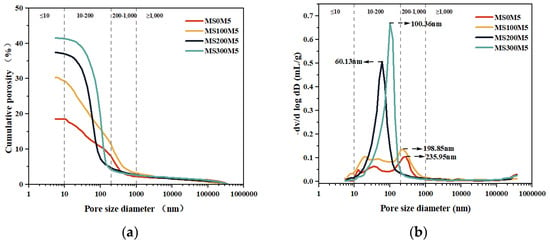

3.4. Pore Structure Analysis by MIP

Figure 17 presents the cumulative porosity and pore size distribution of MS0M5, MS100M5, MS200M5, and MS300M5 specimens after 28 days of curing, Table 6 quantitatively lists the pore volume fractions across different size ranges.

Figure 17.

Effect of NUAA-1M dosage on the pore structure of M-BMSC after 28 days of curing: (a) relationship between pore size and cumulative porosity; (b) relationship between pore size and cumulative intrusion volume.

Table 6.

Proportions of pores with different size ranges in M-BMSC with various mix ratios.

From the cumulative intrusion curves shown in Figure 17a, it is evident that the total porosity increased progressively with the dosage of NUAA-1M fines. As summarized in Table 6, the total porosity of MS0M5, MS100M5, MS200M5, and MS300M5 was 18.63%, 30.31%, 37.43%, and 41.44%, respectively. This increase can be attributed to the reduction in the amounts of MgO and MgSO4·H2O per unit volume with higher NUAA-1M contents, leading to lower and more dispersed formation of the main hydration product, the 5·1·7 phase, thereby increasing overall porosity. Furthermore, since NUAA-1M fines are predominantly tens of micrometers in size and irregular in shape, excessive addition of such particles contributed to looser packing and further increased porosity.

As shown in the differential intrusion curves (Figure 17b), the most probable pore sizes of MS0M5, MS100M5, MS200M5, and MS300M5 were 235.95 nm, 198.85 nm, 60.13 nm, and 100.36 nm, respectively, exhibiting a decrease followed by an increase, with MS200M5 reaching the minimum. Dividing the pores into four ranges (>1000 nm, 200–1000 nm, 10–200 nm, and <10 nm) reveals that MS0M5 and MS100M5 displayed relatively dispersed pore distributions, whereas MS200M5 and MS300M5 exhibited pronounced filling and pore-concentration effects. With increasing NUAA-1M dosage, the proportion of pores larger than 200 nm decreased continuously, while the fraction of pores in the 10–200 nm range increased significantly (56.87–89.33%). The reduction in the most probable pore size and the trend toward a more concentrated pore size distribution are consistent with the highest compressive strength observed for MS200M5.

These pore structure evolutions indicate that NUAA-1M fines optimize the pore structure of the M-BMSC system through two mechanisms: (i) exerting a filling effect that reduces the proportion of pores larger than 200 nm, and (ii) promoting the transformation of hydration products from Mg(OH)2 to the denser 5·1·7 phase. In addition, their reactive components participate in volcanic ash reactions, generating secondary hydration products that further refine and optimize the pore structure. The MIP results are consistent with the compressive strength data and SEM-EDS observations, collectively confirming the regulatory role of NUAA-1M fines in enhancing the performance of the material.

3.5. Fundamental Mechanical Properties of M-BMSCC

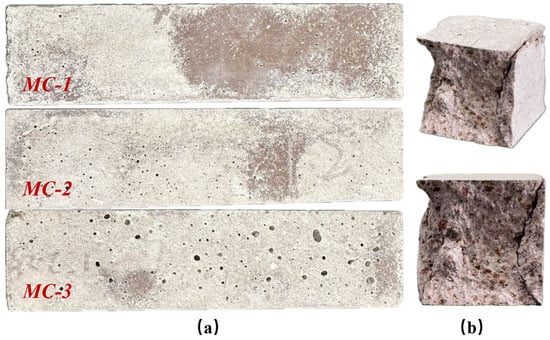

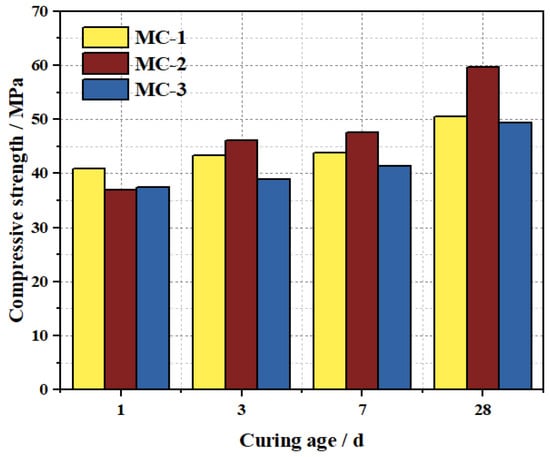

3.5.1. Cubic Compressive Strength

Compressive strength was tested using 40 mm × 40 mm × 40 mm cubes, which were cut from the intact segments of 40 mm × 40 mm × 160 mm prisms after flexural testing. The macroscopic morphology of M-BMSCC specimens with different mix ratios is shown in Figure 18a, while all specimens exhibited a typical conical failure mode under compression (Figure 18b). The compressive strength results of three mixes (MC-1, MC-2, and MC-3) are presented in Figure 19. The results indicate that compressive strength increased continuously with curing age for all mixes, with outstanding early strength. At 1 d, the compressive strengths of MC-1, MC-2, and MC-3 reached 40.9, 36.9, and 37.4 MPa, respectively, highlighting the rapid hydration and high early strength of M-BMSCC. Strength development in MC-2 was particularly pronounced: 46.1 MPa at 3 d (24.9% higher than 1 d), 47.5 MPa at 7 d (3.1% higher than 3 d), and 59.6 MPa at 28 d (25.5% higher than 7 d). From 1 d to 28 d, the compressive strength of MC-2 increased by 61.5% in total. By comparison, the 28 d strengths of MC-1 and MC-3 were 50.5 MPa and 49.4 MPa, 15.3% and 17.1% lower than MC-2, respectively. Nevertheless, all mixes achieved compressive strengths exceeding 49 MPa at 28 d, confirming the excellent high-strength characteristics of the M-BMSCC system.

Figure 18.

(a) Appearance of M-BMSCC specimens with different mix ratios; (b) failure modes after compressive testing.

Figure 19.

Compressive strength of M-BMSCC with different mix ratios.

3.5.2. Flexural Strength and Its Relationship with Compressive Strength

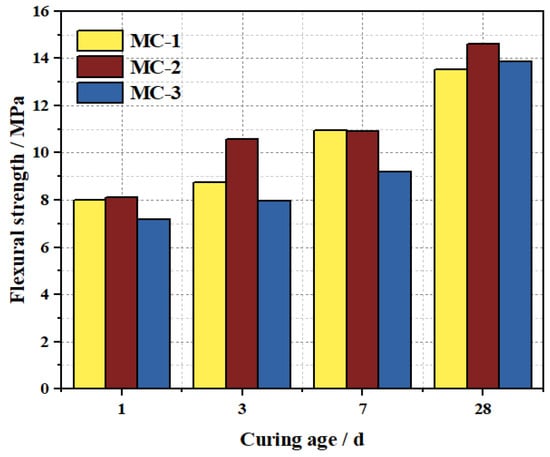

The flexural strength results of M-BMSCC with three mix ratios are shown in Figure 20. The flexural strength increased with curing age, exhibiting favorable early-age performance. At 1 d, the flexural strengths of MC-1, MC-2, and MC-3 were 8.01, 8.10, and 7.17 MPa, respectively. By 3 d, the values increased to 8.74, 10.56, and 7.96 MPa, with MC-2 achieving the highest flexural strength at this age. At 28 d, the strengths further increased to 13.54, 14.62, and 13.87 MPa, respectively. From 1 d to 28 d, the growth rates of flexural strength for the three mixes were 69.0%, 80.5%, and 93.4%.

Figure 20.

Flexural strength of M-BMSCC with different mix ratios.

Currently, various national and industrial organizations have established empirical models relating the flexural strength (ft) to the compressive strength (fcu) of concrete. For instance, the Japan Cement Association (JCA) and the Ministry of Transport of China (MOT) have proposed the following relationships [68,69], given in Equations (10) and (11):

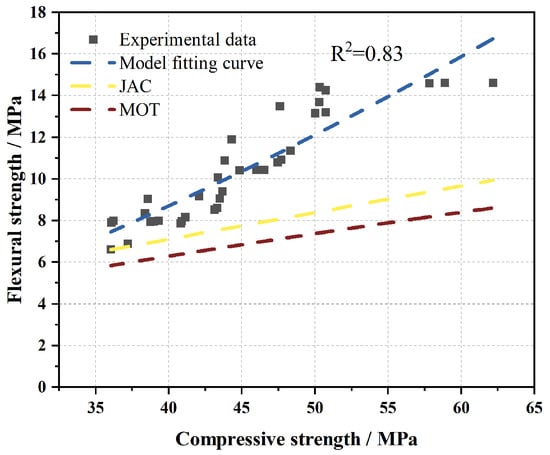

To evaluate the applicability of existing models (JCA and MOT) in describing the relationship between flexural strength (ft) and compressive strength (fcu) of M-BMSCC, and to establish a more suitable correlation for this material, the predictions of different models were compared with experimental data (Figure 21). The results showed that both the JCA and MOT models exhibited significant deviations from the measured values of M-BMSCC. However, the experimental data indicated that the relationship between ft and fcu generally followed a power function. Based on regression analysis of 36 specimens, a new ft–fcu relationship model tailored for M-BMSCC was established:

Figure 21.

Comparison between existing flexural–compressive strength models and the proposed flexural–compressive strength model for M-BMSCC.

The degrees of freedom were df = n − 2 = 34. According to the critical values of the Pearson correlation coefficient (Table 7), when df = 34, the critical value at the highly significant level α = 0.001 is 0.525. The correlation coefficient obtained in this study (R = 0.91) exceeds this threshold, indicating an extremely significant power–law correlation between flexural strength and compressive strength. Specifically, flexural strength increases monotonically with compressive strength, consistent with the established power function model.

Table 7.

Critical values of the Pearson correlation coefficient (R) (partial).

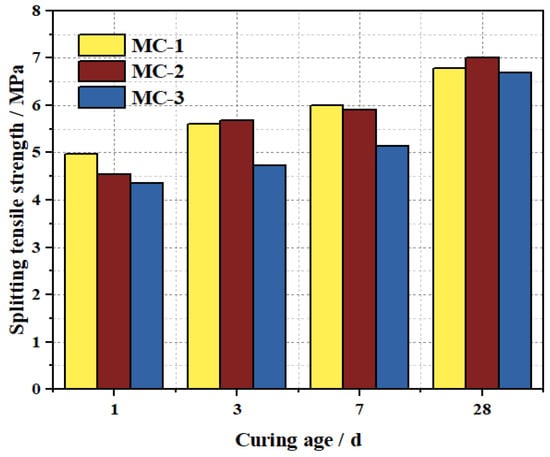

3.5.3. Splitting Tensile Strength and Its Relationship with Compressive Strength

Figure 22 shows the splitting tensile strength results of M-BMSCC with three mix ratios. In all cases, the splitting tensile strength increased continuously with curing age. At 1 d, the strengths of MC-1, MC-2, and MC-3 were 4.97, 4.54, and 4.36 MPa, respectively. By 3 d, the values increased to 5.61, 5.68, and 4.73 MPa; by 28 d, they further rose to 6.79, 7.01, and 6.68 MPa, respectively. Among them, MC-2 exhibited the highest splitting tensile strength at 28 d, with MC-1 and MC-3 being 7.4% and 5.1% lower, respectively. This trend is consistent with that observed for compressive and flexural strengths, further confirming that MC-2 represents the optimal mix design in terms of overall performance.

Figure 22.

Splitting tensile strength of M-BMSCC with different mix ratios.

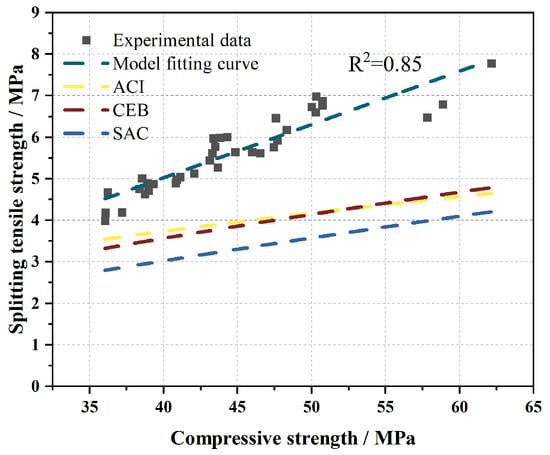

Similarly, several organizations—including the American Concrete Institute (ACI), the Comité Euro-International du Béton/Fédération Internationale de la Précontrainte (CEB-FIP), and the Standardization Administration of China (SAC)—have established empirical models relating splitting tensile strength (fsp) to compressive strength (fcu) of concrete [69,70]. These relationships are expressed in Equations (13)–(15):

Figure 23 compares the predicted values from the aforementioned models with the experimental results of M-BMSCC, revealing significant discrepancies between existing models and the measured data. Based on 36 specimens, it was found that the relationship between splitting tensile strength (fsp) and compressive strength (fcu) also followed a power–law function. Through regression analysis, an fsp–fcu relationship model applicable to M-BMSCC was established:

Figure 23.

Comparison between existing splitting tensile–compressive strength models and the proposed splitting tensile–compressive strength model for M-BMSCC.

At a significance level of α = 0.001 with degrees of freedom (df = 34), the critical value of the Pearson correlation coefficient is 0.525. The correlation coefficient obtained in this study (R = 0.92) exceeds this threshold, confirming that the correlation passes the test of extreme significance. This demonstrates that compressive strength and splitting tensile strength of M-BMSCC exhibit a highly significant power–law relationship.

3.5.4. Comparative Analysis of Different Types of Martian Concretes

Based on the foregoing analyses and discussions, Table 8 [5,7] systematically summarizes and compares various types of Martian concretes in terms of raw material availability, primary advantages, and existing limitations.

Table 8.

Comparison of different types of Martian concretes).

4. Conclusions

Based on the ISRU strategy, this study successfully developed novel Martian construction materials M-BMSC and M-BMSCC. The effects of NUAA-1M on the microstructure and mechanical properties of the M-BMSC system were systematically investigated. Furthermore, M-BMSCC was prepared using M-BMSC as the binder and NUAA-1M as the aggregate, and its mechanical performance was comprehensively evaluated. The main conclusions are as follows:

- The incorporation of NUAA-1M fines markedly prolonged the setting time of M-BMSC. Moderate addition significantly enhanced strength, with the highest 28 d compressive strength achieved when the mass ratio of NUAA-1M fines to MgO was 2:1 (MS/M = 2). Strength contribution analysis revealed that at this ratio, the synergistic effects of filler and pozzolanic activity were maximized. Exceeding this dosage led to a pronounced decline in mechanical properties.

- Hydration monitoring over 24 h indicated that MgO was fully consumed within 10 h, while the 5·1·7 phase was essentially formed within 16 h, demonstrating the rapid hydration capacity of M-BMSC, favorable for construction under Martian extreme environments.

- The addition of NUAA-1M fines promoted the abundant formation of needle- and rod-like 5·1·7 phases and extended the induction period. With increasing dosage, dilution effects further delayed the acceleration stage and reduced both heat release rate and cumulative heat, indicating that NUAA-1M fines regulated the hydration process. Microstructural analysis confirmed that NUAA-1M fines not only acted as fillers to refine pore structure but also participated in secondary hydration reactions, generating M-(A-)S-H gels. The mechanical enhancement was therefore attributed to their dual role in optimizing hydration products and microstructure.

- M-BMSCC exhibited both rapid strength development and high strength, with all mixes exceeding 35 MPa in compressive strength at 1 d. At an aggregate-to-binder ratio of 2:1, where NUAA-1M accounted for 84.75% of the system, the 28 d compressive, flexural, and splitting tensile strengths reached 59.6, 14.62, and 7.01 MPa, respectively, representing the optimal performance. Moreover, empirical ft and fsp relationships were established, providing key parameters and theoretical basis for the structural design of future Martian bases.

As human exploration of Mars continues to advance, the construction of extraterrestrial bases has become a critical step toward sustained planetary migration. The Martian environment is extremely complex, characterized by long term exposure to low gravity, high vacuum, extremely low temperatures, large temperature fluctuations, and frequent meteoroid impacts. Under these conditions, M-BMSCC, as a potential ISRU based construction material, still requires systematic experimental verification with respect to its mechanical behavior under low vacuum and low gravity, long term durability, and the feasibility of extraterrestrial 3D printing construction technologies, to ensure its reliability and adaptability in practical engineering applications.

Author Contributions

M.L.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft. H.M. (Haiyan Ma): Supervision, Writing—review & editing. C.W.: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Project administration. H.Y.: Conceptualization, Project administration, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. H.Z.: Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization. H.X.: Investigation. L.L.: Investigation. K.Z.: Investigation. W.L.: Investigation. H.M. (Haoxia Ma): Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 52208254 and 52462004) and the Key R&D and Transformation Program of Qinghai Province (No. 2023-GX-105).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Koca, E.; Turer, A. Design, optimization, and autonomous construction of Martian infrastructure including slabs using in-situ CO2-based polyethylene. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, G.; Ochsendorf, J. Building on mars. Civ. Eng. Mag. Arch. 2005, 75, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, H.; Sun, L.; Guo, Z.; Harvey, J.; Tang, Q.; Lu, H.; Jia, M. In-situ resources for infrastructure construction on Mars: A review. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Bai, Y.; Wang, L.; Jia, Y.; Shen, W.; Fan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, A. Scientific objectives and payloads of Tianwen-1, China’s first Mars exploration mission. Adv. Space Res. 2021, 67, 812–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.J.; Shi, T.; Cen, M.Q.; Wang, J.M.; Zhao, X.Y.; Zeng, C.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, Y.J.; Liu, Y.M.; Zhao, Z.F. Research progress on lunar and Martian concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 343, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.N.; Oze, C. Constructing Mars: Concrete and Energy Production From Serpentinization Products. Earth Space Sci. 2018, 5, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reches, Y. Concrete on Mars: Options, challenges, and solutions for binder-based construction on the Red Planet. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 104, 103349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascardi, A.; Verre, S.; Micelli, F.; Aiello, M.A. Durability-aimed performance of glass FRCM-confined concrete cylinders: Experimental insights into alkali environmental effects. Mater. Struct. 2025, 58, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlmann, B.L.; Edwards, C.S. Mineralogy of the Martian Surface. In Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences; Jeanloz, R., Ed.; Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences; Annual Reviews: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2014; Volume 42, pp. 291–315. [Google Scholar]

- Bibring, J.-P.; Soufflot, A.; Berthé, M.; Langevin, Y.; Gondet, B.; Drossart, P.; Bouyé, M.; Combes, M.; Puget, P.; Sémery, A. OMEGA: Observatoire pour la Minéralogie, l’Eau, les Glaces et l’Activité. In Mars Express: The Scientific Payload; Wilson, A., Ed.; Scientific Coordination: Agustin Chicarro; ESA SP-1240; ESA Publications Division: Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 1240, pp. 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Murchie, S.; Arvidson, R.; Bedini, P.; Beisser, K.; Bibring, J.P.; Bishop, J.; Boldt, J.; Cavender, P.; Choo, T.; Clancy, R. Compact reconnaissance imaging spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) on Mars reconnaissance orbiter (MRO). J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2007, 112, E05S03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidson, R.E.; Poulet, F.; Bibring, J.P.; Wolff, M.; Gendrin, A.; Morris, R.V.; Freeman, J.J.; Langevin, Y.; Mangold, N.; Bellucci, G. Spectral reflectance and morphologic correlations in eastern Terra Meridiani, Mars. Science 2005, 307, 1591–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendrin, A.; Mangold, N.; Bibring, J.-P.; Langevin, Y.; Gondet, B.; Poulet, F.; Bonello, G.; Quantin, C.; Mustard, J.; Arvidson, R. Sulfates in Martian layered terrains: The OMEGA/Mars Express view. Science 2005, 307, 1587–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Jolliff, B.L.; Liu, Y.; Connor, K. Setting constraints on the nature and origin of the two major hydrous sulfates on Mars: Monohydrated and polyhydrated sulfates. J. Geophys. Res.-Planets 2016, 121, 678–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutolo, B.M.; Hausrath, E.M.; Kite, E.S.; Rampe, E.B.; Bristow, T.F.; Downs, R.T.; Treiman, A.; Peretyazhko, T.S.; Thorpe, M.T.; Grotzinger, J.P.; et al. Carbonates identified by the Curiosity rover indicate a carbon cycle operated on ancient Mars. Science 2025, 388, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheidema, M.N.; Taskinen, P. Decomposition Thermodynamics of Magnesium Sulfate. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 9550–9556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Z.; Zhu, Q.W.; Yi, Q.J.; Zuo, W.J.; Feng, Y.P.; Chen, S.Y.; Dong, Y. Experimental method for observing the fate of SO3/H2SO4 in a temperature-decreasing flue gas flow: Creation of state diagram. Fuel 2019, 249, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutolo, B.M.; Leong, J.A. Serpentine Solid Solutions and Hydrogen Production on Early Earth and Mars. Elements 2025, 21, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, V.; Pandit, M. Surface properties of magnesium oxide obtained from magnesium hydroxide: Influence on preparation and calcination conditions of magnesium hydroxide. Appl. Catal. 1991, 71, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demediuk, T.; Cole, W.F. A study on magnesium oxysulphates. Aust. J. Chem. 1957, 10, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.Y.; Yu, H.F.; Dong, J.M.; Zheng, L.N. Effects of Material Ratio, Fly Ash, and Citric Acid on Magnesium Oxysulfate Cement. Aci Mater. J. 2014, 111, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J., III; McSween, H., Jr.; Crisp, J.; Morris, R.; Murchie, S.; Bridges, N.; Johnson, J.; Britt, D.; Golombek, M.; Moore, H. Mineralogic and compositional properties of Martian soil and dust: Results from Mars Pathfinder. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2000, 105, 1721–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, M.B.; McSween, H.Y., Jr. Spectral evidence for weathered basalt as an alternative to andesite in the northern lowlands of Mars. Nature 2002, 417, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandfield, J.L.; Hamilton, V.E.; Christensen, P.R. A Global View of Martian Surface Compositions from MGS-TES. Science 2000, 287, 1626–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellert, R.; Rieder, R.; Anderson, R.; Bruckner, J.; Clark, B.; Dreibus, G.; Economou, T.; Klingelhofer, G.; Lugmair, G.; Ming, D. Chemistry of rocks and soils in Gusev Crater from the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer. Science 2004, 305, 829–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieder, R.; Gellert, R.; Anderson, R.; Bruckner, J.; Clark, B.; Dreibus, G.; Economou, T.; Klingelhofer, G.; Lugmair, G.; Ming, D. Chemistry of rocks and soils at Meridiani Planum from the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer. Science 2004, 306, 1746–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, D.F.; Morris, R.V.; Kocurek, G.; Morrison, S.M.; Downs, R.T.; Bish, D.; Ming, D.W.; Edgett, K.S.; Rubin, D.; Goetz, W.; et al. Curiosity at Gale Crater, Mars: Characterization and Analysis of the Rocknest Sand Shadow. Science 2013, 341, 1239505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McSween, H.Y., Jr.; McGlynn, I.O.; Rogers, A.D. Determining the modal mineralogy of Martian soils. J. Geophys. Res.-Planets 2010, 115, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizovski, T.V.; Schmidt, M.E.; O’Neil, L.; Jones, M.W.M.; Tosca, N.J.; Klevang, D.A.; Hurowitz, J.A.; Adcock, C.T.; Hausrath, E.M.; Siebach, K.L.; et al. Fe-phosphates in Jezero Crater as evidence for an ancient habitable environment on Mars. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausrath, E.M.; Adcock, C.T.; Berger, J.A.; Cycil, L.M.; Kizovski, T.V.; McCubbin, F.M.; Schmidt, M.E.; Tu, V.M.; Vanbommel, S.J.; Treiman, A.H.; et al. Phosphates on Mars and Their Importance as Igneous, Aqueous, and Astrobiological Indicators. Minerals 2024, 14, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awwad, N.S.; El-Nadi, Y.A.; Hamed, M.M. Successive processes for purification and extraction of phosphoric acid produced by wet process. Chem. Eng. Process. 2013, 74, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.Y.; Yu, H.F.; Zhang, H.F.; Dong, J.M.; Wen, J.; Tan, Y.S. Effects of phosphoric acid and phosphates on magnesium oxysulfate cement. Mater. Struct. 2015, 48, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runčevski, T.; Wu, C.; Yu, H.; Yang, B.; Dinnebier, R.E. Structural characterization of a new magnesium oxysulfate hydrate cement phase and its surface reactions with atmospheric carbon dioxide. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2013, 96, 3609–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Gao, X.; Chen, T. Recycling of raw rice husk to manufacture magnesium oxysulfate cement based lightweight building materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 191, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Applications of basic magnesium sulfate cement in civil engineering. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2018, 66, 1189–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, X.; Yu, H. Study on large eccentric compression column of basic magnesium sulfate cement concrete. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 2017, 38, 852–858. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, X.; Yu, H.; Wu, C. An overview of study on basic magnesium sulfate cement and concrete in China (2012–2019). KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 23, 4445–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yu, H.; Ma, H.; Wu, C.; Zhang, N.; Wang, N. Theoretical Foundation, Hydration Mechanism, and Concrete Performance of Basic Magnesium Sulfate Cement. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 111, 113120. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Lei, H.; Tao, J.; Wu, C. Effect of MgO/MgSO4 molar ratio on the hydration and mechanical properties of bms containing steel slag. Ceram. Silik. 2022, 66, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Yu, H.; Yang, D.; Feng, T. Basic magnesium sulfate cement: Autogenous shrinkage evolution and mechanism under various chemical admixtures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 128, 104412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.H.; Liu, H.; Meng, X.; Duan, D.W.; Lu, H.J.; Zhang, J.H.; Zhang, F.S.; Elsworth, D.; Cardenas, B.T.; Manga, M.; et al. Ancient ocean coastal deposits imaged on Mars. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondro, C.A.; Fedo, C.M.; Grotzinger, J.P.; Lamb, M.P.; Gupta, S.; Dietrich, W.E.; Banham, S.; Weitz, C.M.; Gasda, P.; Edgar, L.A.; et al. Wave ripples formed in ancient, ice-free lakes in Gale crater, Mars. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, Z.J.; Cardenas, B.T. Modeling Lake Bonneville Paleoshoreline Erosion at Mars-Like Rates and Durations: Implications for the Preservation of Erosional Martian Shorelines and Viability as Evidence for a Martian Ocean. J. Geophys. Res.-Planets 2025, 130, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banin, A. The Enigma of the Martian Soil. Science 2005, 309, 888–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, K.M.; Britt, D.T.; Smith, T.M.; Fritsche, R.F.; Batcheldor, D. Mars global simulant MGS-1: A Rocknest-based open standard for basaltic martian regolith simulants. Icarus 2019, 317, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.H.; Abbey, W.; Bearman, G.H.; Mungas, G.S.; Smith, J.A.; Anderson, R.C.; Douglas, S.; Beegle, L.W. Mojave Mars simulant—Characterization of a new geologic Mars analog. Icarus 2008, 197, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.-z.; Liu, A.-m.; Xie, K.-y.; Shi, Z.-n.; Kubikova, B. Preparation and characterization of Martian soil simulant NEU Mars-1. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2020, 30, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bish, D.L.; Blake, D.F.; Vaniman, D.T.; Chipera, S.J.; Morris, R.V.; Ming, D.W.; Treiman, A.H.; Sarrazin, P.; Morrison, S.M.; Downs, R.T.; et al. X-ray Diffraction Results from Mars Science Laboratory: Mineralogy of Rocknest at Gale Crater. Science 2013, 341, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilles, C.N.; Downs, R.T.; Ming, D.W.; Rampe, E.B.; Morris, R.V.; Treiman, A.H.; Morrison, S.M.; Blake, D.F.; Vaniman, D.T.; Ewing, R.C.; et al. Mineralogy of an active eolian sediment from the Namib dune, Gale crater, Mars. J. Geophys. Res.-Planets 2017, 122, 2344–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, D.; Cannon, K.M.; Gurlo, A. Review of space resources processing for Mars missions: Martian simulants, regolith bonding concepts and additive manufacturing. Open Ceram. 2022, 9, 100216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, J.; Yu, H.; Ma, H.; Wu, Z. Experimental and 3D mesoscopic investigation of uniaxial compression performance on basic magnesium sulfate cement-coral aggregate concrete (BMSC-CAC). Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 236, 109760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, J.; Yu, H.; Ma, H. Dynamic compressive behaviour of basic magnesium sulfate cement–coral aggregate concrete (BMSC–CAC) after exposure to elevated temperatures: Experimental and analytical studies. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 382, 131336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 1346-2011; Test Methods for Water Requirement of Normal Consistency, Setting Time and Soundness of Portland Cement. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2011.

- GB/T 17671-2021; Test Method of Cement Mortar Strength (ISO Method). China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2021.

- GB/T 50081-2019; Standard for Test Methods of Concrete Physical and Mechanical Properties. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Simoni, M.; Woo, C.L.; Zhao, H.; Iuga, D.; Svora, P.; Hanein, T.; Kinoshita, H.; Walkley, B. Reaction mechanisms, kinetics, and nanostructural evolution of magnesium silicate hydrate (MSH) gels. Cem. Concr. Res. 2023, 174, 107295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.C. Numerical analysis of volcanic ash effect in high strength and highperformance concrete. Concrete 1998, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.Y.; Chen, W.H.; Zhang, H.F.; Yu, H.F.; Zhang, W.Y.; Jiang, N.S.; Liu, L.X. The hydration mechanism and performance of Modified magnesium oxysulfate cement by tartaric acid. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 144, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.S.; Yu, H.F.; Sun, S.K.; Wu, C.Y.; Ding, H. Properties and microstructure of basic magnesium sulfate cement: Influence of silica fume. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 266, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Feng, W.J.; Su, Y.; Yu, H.F.; Ba, M.F.; He, Z.M. Different effects for phosphoric acid and calcium citrate on properties of magnesium oxysulfate cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 374, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Liu, A.X.; Chen, L.; Xue, X.Y.; Yu, H.F.; Ba, M.F. A study of hydration reaction on the MgO-MgSO4-H2O system. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 485, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Yu, H.F.; Ma, H.Y.; Ma, H.X.; Ba, M.F. The phase composition of the MgO-MgSO4-H2O system and mechanisms of chemical additives. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 247, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupwade-Patil, K.; Palkovic, S.D.; Bumajdad, A.; Soriano, C.; Büyüköztürk, O. Use of silica fume and natural volcanic ash as a replacement to Portland cement: Micro and pore structural investigation using NMR, XRD, F’TIR and X-ray microtomography. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 158, 574–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lothenbach, B.; Nied, D.; L’Hôpital, E.; Achiedo, G.; Dauzères, A. Magnesium and calcium silicate hydrates. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 77, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, E.; Lothenbach, B.; Cau-Dit-Coumes, C.; Pochard, I.; Rentsch, D. Aluminum incorporation into magnesium silicate hydrate (M-S-H). Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 128, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Yu, H.F.; Ma, H.Y.; Ba, M.F. Effects of different pH chemical additives on the hydration and hardening rules of basic magnesium sulfate cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 305, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walling, S.A.; Provis, J.L. Magnesia-based cements: A journey of 150 years, and cements for the future? Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 4170–4204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.K. Study on contradictory relationship between compressive and bending srtength and conception of synthetic value. Concrete 2003, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.M.; Yu, H.F.; Tan, Y.S.; Wu, C.Y.; Wu, P.; Ma, H.Y.; Ding, Z.G.; Liu, L.X. Mechanical Properties, Corrosion Damage Evolution Laws, and Durability Deterioration Indicators of High-Performance Concrete Exposed to Saline Soil Environment for 8 Years. Materials 2025, 18, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinpelu, M.A.; Odeyemi, S.O.; Olafusi, O.S.; Muhammed, F.Z. Evaluation of splitting tensile and compressive strength relationship of self-compacting concrete. J. King Saud Univ.-Eng. Sci. 2019, 31, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.