Abstract

This study investigates sustainable alternatives for thermal regulation in building materials by incorporating modified basic oxygen furnace slag (MBOFS) as a partial replacement for natural aggregates in concrete. MBOFS was produced by injecting oxygen and silica sand into molten BOF slag to reduce free CaO and MgO, enhancing stability and suitability for cementitious composites. Characterization revealed high mid-infrared emissivity (up to 95.92% in the 8–13 μm range), low solar reflectivity, and high absorptance—properties favorable for passive radiative cooling. Optical, physical, mechanical, and thermal evaluations included spectral analysis, tests for density, porosity, compressive strength, and indoor irradiation with heat flux and temperature monitoring. Increasing MBOFS content raised thermal resistance from 0.034 to 0.069 m2·K/W and lowered thermal transmittance from 3.644 to 3.235 W/m2·K. Higher heat storage capacity and higher emissivity (thermal radiation) suppress the thermal transmittance, thus improving the thermal resistance of the building walls. The 60% replacement showed the most balanced surface thermal response, whereas higher ratios yielded greater energy retention. These results demonstrate that MBOFS can enhance insulation, radiative cooling, and mechanical performance, advancing climate-responsive concrete for urban heat island mitigation.

1. Introduction

According to the National Centers for Environmental Information [1], 2024 was the warmest year on record since the beginning of global temperature monitoring. The increase in global temperatures is primarily attributed to greenhouse gas emissions [2], which drive climate change and intensify the urban heat island (UHI) effect [3]. Transportation and industrial activities in urban areas not only contribute to elevated emissions but also increase the absorption and scattering of radiation, particularly in the infrared spectrum, thereby raising urban ambient temperatures [4]. In addition, artificial surfaces commonly found in cities, particularly concrete and asphalt, exhibit high thermal capacity and thermal inertia, enabling them to absorb large amounts of heat during the day and release it slowly at night—one of the primary mechanisms intensifying the UHI effect [2,5]. These materials absorb solar radiation rapidly during the daytime and release stored heat gradually during the night, leading to prolonged nocturnal warming that further exacerbates the UHI phenomenon [6]. At a broader scale, the built environment and widespread use of such impervious materials further enhance heat storage within cities, amplifying urban temperatures compared with natural surfaces [7].

Solar radiation is absorbed by terrestrial surfaces and subsequently re-emitted as thermal radiation, predominantly in the infrared range (6–15 μm) [8], consistent with the Planck distribution at surface temperatures around 300 K. A portion of this radiation, particularly within the 8–13 μm spectral range [9], especially in 8–12 μm, can pass through the atmosphere and escape into space [10]. This phenomenon, referred to as the infrared atmospheric window, plays a critical role in Earth’s radiative heat dissipation [11]. To mitigate this issue, increasing attention has been given to radiative-cooling materials capable of selectively emitting thermal radiation within the atmospheric window [12,13]. Materials characterized by high solar reflectivity and high infrared atmospheric window emissivity (8–13 μm) can reduce solar heat gain while enhancing long-wave radiative cooling. Their application has shown potential in mitigating the UHI effect by lowering surface and ambient temperatures [14,15].

When integrated into urban infrastructure such as building envelopes, pavements, and rooftops, these materials can significantly improve outdoor thermal comfort and contribute to passive cooling strategies. Reflective coatings and high-albedo building components have been shown to lower surface and ambient temperatures by enhancing solar reflectivity and thermal emissivity, thereby reducing heat accumulation during the day [16]. Pavement materials with optimized radiative and thermal properties can further mitigate local heat islands and improve pedestrian thermal comfort, highlighting the importance of material selection in urban microclimate management [17]. Recent advances in increasing the solar reflectivity of building envelopes not only enhance their long-term passive cooling performance but also provide guidance on sustainable material application and urban-scale energy efficiency [18].

Basic oxygen furnace slag (BOFS) exhibits high emissivity within the infrared atmospheric window and excellent thermal stability, making it a promising material for mitigating UHI effects [19]. Steel-slag aggregates typically exhibit thermal conductivity (3.1 W/m·K) and specific heat capacity (1.4 J/g·K), values markedly higher than those of sedimentary, volcanic, and plutonic rocks [20,21]. BOFS is a primary by-product of steelmaking, generated from the basic oxygen furnace process [22]. Incorporation of BOFS into building and pavement materials has been shown to enhance surface temperature, heating efficiency, and porosity, while reducing internal temperature, thermal transmittance, and thermal diffusivity, thereby improving passive cooling efficiency [23,24]. Beyond its thermal benefits, BOFS offers high hardness, wear resistance, and compressive strength, making it suitable for various civil engineering applications, including road construction, paving tiles, artificial reefs, land reclamation, and railway ballast [25,26]. BOFS is a primary by-product of steelmaking, generated from the basic oxygen furnace process. As a by-product of steelmaking, generated from the basic oxygen furnace process, BOFS production accounts for approximately 9% of global crude steel output (~1.9 billion tons annually) [27,28]. Given its large volume and potential environmental impact, effective utilization of BOFS is critical for both sustainable steel production and leveraging its radiative-cooling properties to reduce urban temperatures [29]. Using steel slag as aggregate reduces natural aggregate extraction and diverts industrial by-products from landfills, improving resource efficiency and lowering life-cycle environmental burden [30]; however, potential heavy-metal leaching requires careful evaluation.

The primary challenge in utilizing BOFS in cementitious systems lies in its expansive behavior, mainly attributed to the presence of free CaO (f-CaO) and free MgO (f-MgO). Additionally, the oxidation of ferrous oxide (FeO) can induce volume instability and surface reddening, ultimately leading to cracking and failure of the material [31,32]. Studies on cement mortars blended with high amounts of BOFS have shown that partial carbonation or optimized replacement ratios can reduce expansion and improve volumetric stability [33,34]. To address this issue, hot slag modification technology has been developed. By injecting oxygen and adding silica sand into molten BOFS at temperatures between 1300 and 1600 °C, FeO is oxidized to Fe2O3, which then reacts with f-CaO to form calcium ferrite (Ca2Fe2O5). Simultaneously, SiO2 reacts with CaO to form calcium silicate (Ca2SiO4), while f-MgO reacts with CaO and SiO2 to produce akermanite (Ca2MgSi2O7). This process significantly reduces the contents of f-CaO, f-MgO, and FeO, lowering the residual expansion rate of BOFS from 37–42% to 0.2–0.6%, thereby enhancing its volumetric stability [35,36]. Recent studies further highlight that oxidative and high-temperature modification of BOFS can improve compressive, flexural, and impact strengths of concrete, making the resulting modified BOFS (MBOFS) a reliable sustainable alternative to natural aggregates [37,38]. Moreover, leveraging BOFS in cementitious materials supports the recycling of steelmaking by-products, conserves natural resources, and provides environmental benefits by reducing dependence on sand and gravel extraction [39,40]. Finally, applications of modified BOFS (MBOFS) have been successfully demonstrated in pavements, structural concrete, and precast elements, indicating MBOFS’s potential as a high-performance, environmentally sustainable construction material [41,42].

In this study, MBOFS is proposed as a sustainable alternative to natural aggregates in concrete, with the objective of mitigating the UHI effect. The physical, mechanical, and thermal properties of MBOFS-incorporated concrete were systematically evaluated. Comprehensive material characterization was performed, including analysis of elemental composition and crystalline phases of MBOFS. In addition, the optical properties relevant to heat transfer were compared between MBOFS and conventional natural aggregates. Furthermore, the heat storage and dissipation behaviors of MBOFS concrete were examined through theoretical analysis based on experimental findings.

2. Materials and Properties

The concrete materials in this study include cement and aggregates, which are detailed in this chapter. A series of experiments were conducted to evaluate the fundamental properties of MBOFS. Finally, the mixed proportions and specimens’ nomenclature were established.

2.1. Cement and Aggregates

Type I Portland cement, manufactured by Taiwan Cement Co., Ltd. (Taipei, Taiwan), was used as the binder for all concrete specimens. The natural aggregates consisted of quartz sand and coarse gravel. The MBOFS used in this study was provided by China Steel Corporation (Kaohsiung, Taiwan). It was produced by injecting oxygen and silica sand into molten BOFS at 1400 °C, facilitating reactions with f-CaO and f-MgO to improve volumetric stability. The resulting MBOFS was crushed and sieved into gravel and sand fractions for use as aggregate. For material characterization, MBOFS was finely ground using a ceramic mortar and pestle and passed through a No. 200 sieve (75 µm). Elemental analysis using X-ray fluorescence (XRF, X-MET8000, Hitachi High-Tech Co., Tokyo, Japan) in accordance with ASTM E1621-22 [43] revealed the contents of Ca, Fe, and Si to be 42.91%, 36.00%, and 10.62%, respectively, as shown in Table 1. X-ray diffraction (XRD; D2 PHASER, Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) was performed in accordance with ASTM E3294-23 [44] under standardized environmental conditions (23 ± 2 °C and 50 ± 5% RH) using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). The diffraction patterns were recorded over a 2θ range of 10–80° with a step size of 0.02° and a scanning speed of 2°/min to identify the predominant crystalline phases of the MBOFS powder, including calcite (CaCO3), dicalcium silicate (Ca2SiO4), wüstite (FeO), and calcium oxide (CaO), as shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Elemental composition of MBOFS.

Figure 1.

Crystal phases of MBOFS.

According to ASTM C33/C33M-24a [45], the fineness modulus (F.M.) of fine aggregates should fall within the range of 2.3 to 3.1. The F.M. of quartz sand was measured at 2.55. With increasing MBOFS content in the mixed sand, the F.M. values increased accordingly: 2.79 at 20% replacement, 3.02 at 40%, 3.25 at 60%, 3.49 at 80%, and 3.72 at 100% MBOFS. The particle size distribution curves for each replacement level are shown in Figure 2. As the MBOFS content increased, the curves shifted downward and to the left, indicating a reduction in fine particles. At replacement levels of 60% and above, the grading curves exceeded the ASTM C33/C33M-24a specification limits, indicating discontinuous grading. According to Popovics and Mather (1973) [46], such grading can result in insufficient mortar coating around coarse particles, reducing internal compactness and leading to non-uniform particle packing and surface voids.

Figure 2.

Fine particle distribution curve of each ratio.

2.2. Optical Properties of Aggregates

This section presents a comparison of the optical behavior between natural aggregates and MBOFS powders. Reflectance, transmittance, and absorptance were analyzed across the full solar spectrum, while emissivity was evaluated specifically in the infrared region, where thermal radiation is the primary mode of heat transfer.

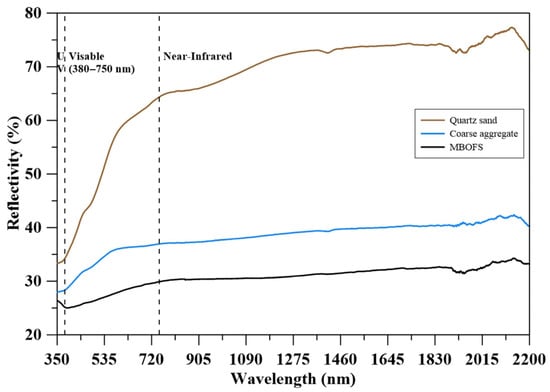

2.2.1. Reflectivity

Reflectivity was measured using a UV–Vis–NIR spectrometer (V-770, Jasco Co., Hachiōji, Japan) equipped with an integrating sphere (ILN-925, Jasco Co., Hachiōji, Japan). Reflectivity of materials was conducted by comparing the reflected intensity of the sample with that of a barium sulfate (BaSO4) standard white plate. The measurement wavelength range was 350–2200 nm.

Figure 3 shows the spectral reflectivity of quartz sand, natural coarse aggregate, and MBOFS powder across the 350–2200 nm wavelength range. MBOFS exhibited the lowest reflectivity (25–35%), indicating a higher capacity for solar energy absorption. In contrast, quartz sand displayed the highest reflectivity, exceeding 70%, while natural coarse aggregate ranged from 35% to 45%. Although high-reflectivity materials can reduce surface and ambient air temperatures, they may also lead to increased cooling loads on adjacent buildings and contribute to glare, ultraviolet (UV) exposure, and thermal discomfort [47].

Figure 3.

Reflectivity of aggregates.

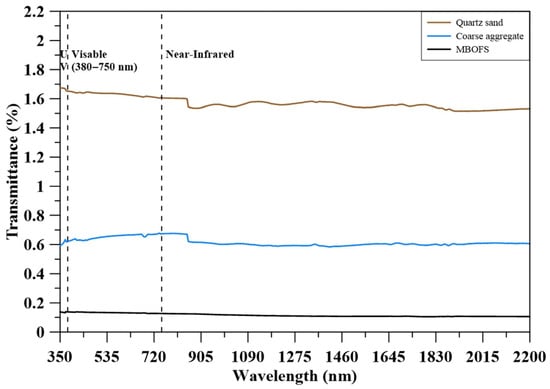

2.2.2. Transmittance

The transmittance of material powder films was measured using a UV–Vis–NIR spectrometer (V-770, Jasco Co., Hachiōji, Japan). Transmittance was calculated by comparing the intensity of light transmitted through the sample with that through a glass reference used as a blank. Measurements were conducted over a wavelength range of 350–2200 nm.

Figure 4 shows the spectral transmittance of quartz sand, natural coarse aggregate, and MBOFS powder over the 350–2200 nm wavelength range. MBOFS exhibited the lowest transmittance, remaining below 0.2% throughout the entire spectrum. In contrast, quartz sand and natural coarse aggregate showed slightly higher transmittance values of approximately 1.5% and 0.6%, respectively. These results confirm that all three materials are highly opaque, with MBOFS demonstrating the greatest effectiveness in attenuating incident solar radiation.

Figure 4.

Transmittance of aggregates.

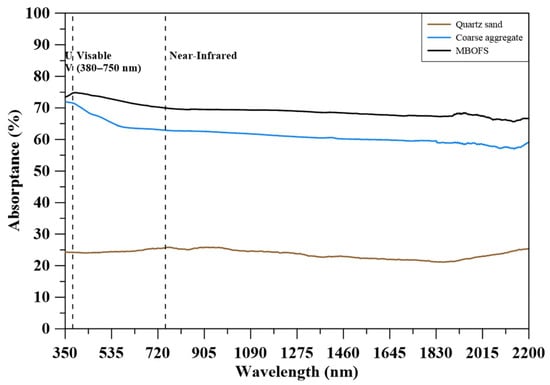

2.2.3. Absorptance

Absorptance represents the proportion of incident light energy absorbed by a material. As defined in Equation (1), the total incident light energy is normalized to 100%. The absorptance is determined by subtracting the percentages of reflected and transmitted light from the incident light. The remaining portion corresponds to the energy absorbed by the material.

where A represents absorptance (%), 100% represents the energy of the incident light, R is reflectivity (%), and T is transmittance (%).

Figure 5 presents the spectral absorptance of quartz sand, natural coarse aggregate, and MBOFS powder across the 350–2200 nm wavelength range. MBOFS exhibited the highest absorptance throughout the measured spectrum, maintaining values between 70% and 75%. Coarse aggregates showed moderately high absorptance, ranging from approximately 60% to 68%, while quartz sand demonstrated the lowest absorptance, remaining below 30%. The consistently high absorptance of MBOFS indicates a strong capacity for solar energy uptake, which may lead to greater heat accumulation under solar exposure.

Figure 5.

Absorptance of aggregates.

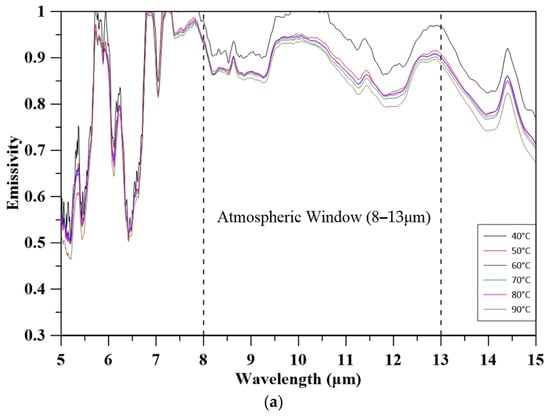

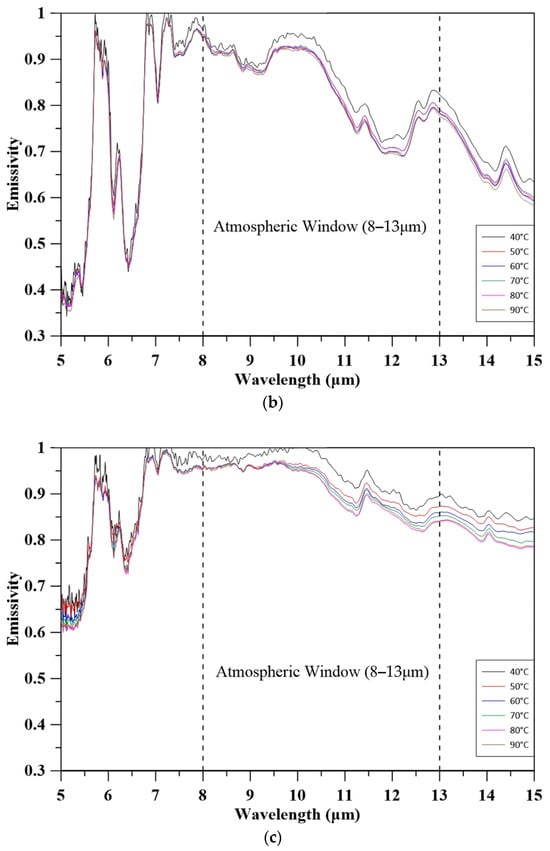

2.2.4. Emissivity

The spectral emissivity of powdered materials was measured using a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR, INVENIO, Bruker, Charlottesville, VA, USA) over the 5–15 μm wavelength range. The measurement procedure followed the FTIR-based relative method described by Zhang et al. (2010) [48]. Specimens were placed in a temperature-controlled heating fixture, and their emitted thermal radiation was recorded and converted into spectral intensity data via Fourier transformation. Emissivity values were obtained at 40 °C, 50 °C, 60 °C, 70 °C, 80 °C, and 90 °C, using 35 °C as the reference temperature.

Spectral emissivity values were derived by comparing the background-subtracted relative spectral intensities of the sample and a blackbody at both measurement and reference temperatures, as shown in Equation (2):

where and denote the relative spectral intensities of the sample and the blackbody, respectively, at the measurement temperature () and reference temperature (). These are not absolute radiometric quantities but FTIR signals under identical optical conditions. Emissivity, , reflects the material’s radiative efficiency, ranging from 0 to 1. This method eliminates background effects and instrument noise, enabling reliable emissivity estimation under controlled thermal conditions.

Figure 6 illustrates the spectral emissivity of quartz sand, natural coarse aggregate, and MBOFS powder over the 5–15 μm range at varying temperatures. All materials exhibited a slight decrease in emissivity with increasing temperature, which is likely attributed to phonon damping and the consequent reduction in infrared absorption efficiency. Notably, the average emissivity within the atmospheric window (8–13 μm) was highest for MBOFS (91.72–95.92%), followed by natural coarse aggregate (88.77–93.90%) and quartz sand (85.16–88.57%). The enhanced mid-infrared emissivity of MBOFS is primarily associated with its abundant polar oxide phases, such as CaCO3, Ca2SiO4, FeO, and CaO, which enable strong phonon–polariton interactions. These findings suggest that MBOFS possesses superior radiative performance, making it a promising aggregate material for passive cooling applications in building envelopes [49,50].

Figure 6.

Emissivity of aggregates: (a) quartz sand; (b) coarse aggregate; (c) MBOFS.

2.3. Mixture Design

All mix proportions of concrete specimens were prepared with a water–cement ratio of 0.55. In the experimental mixes, natural aggregates in the control group were replaced with MBOFS aggregates at the volumetric replacement percentages of 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100%. The replacement masses were calculated using the specific gravities of natural quartz sand (2.65), natural coarse aggregate (2.66), and MBOFS (3.33) to achieve equivalent volumetric substitution. The detailed mix proportions of cement and aggregates used in each mix are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mix proportions of cement and aggregates used in concrete.

The nomenclature of the experimental specimens is summarized in Table 3. Each code consists of a test type identifier, a material designation, and the curing age. For example, C-MS-20-7d represents a specimen tested in compression (C), incorporating 20% MBOFS aggregate (MS-20), and cured for 7 days (7d). The prefix “RS” denotes the reference specimen without MBOFS, serving as the control. The designation “MS” indicates the use of MBOFS aggregate, and the number (20, 40, 60, 80, 100) following it specifies the percentage of natural aggregate replaced by MBOFS.

Table 3.

Nomenclature of test specimens.

3. Test Methods

The test method for evaluating the physical (density and porosity), mechanical (compressive strength), and thermal properties (heating/cooling behavior, emissivity, and thermal transmittance) of the concrete specimens is presented in this chapter.

3.1. Density and Porosity Test

The density and porosity of all concrete specimens were measured in accordance with ASTM C642-21 [51] using cylindrical specimens (10 cm × 10 cm) cured for 28 days. The procedure involves sequential drying, soaking, and boiling steps to quantify water absorption and calculate apparent density and porosity. The oven-dry bulk density (), and porosity () were calculated based on the oven-dry weight (A), boiled saturated weight (B), and suspended weight (C), as defined by Equations (3) and (4):

where is expressed in kg/m3, in %, and is the water density. , , and are in grams.

3.2. Compressive Strength Test

According to ASTM C39/C39M-24 [52], the compressive strength test for the concrete cylindrical specimens was carried out using a universal material testing machine (model HT-9501, Hung Ta Instrument Co., Ltd., Taichung, Taiwan). The test involves proper specimen alignment, controlled loading at a specified stress rate, and recording the maximum load to calculate compressive strength. Cylindrical specimens with a diameter of 10 cm and a height of 20 cm were tested after curing periods of 7 and 28 days under dry conditions The 7-day tests were included because MBOFS aggregates may affect early-age hydration; verifying early strength is therefore necessary to ensure safe formwork removal and to identify any delay in strength gain, consistent with ACI 318-19 and ACI 214R-11. The tests were performed under a controlled loading rate of 0.25 MPa/s.

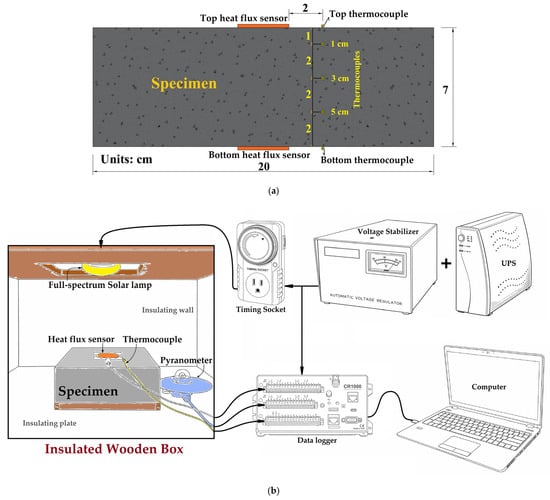

3.3. Indoor Irradiation Test

Previous studies assessed thermal insulation, storage, and release performance by irradiating specimens with heating lamps, and also monitoring the temperature and heat flux. Li et al. (2021) demonstrated a long-duration irradiation methodology using three 500 W halogen lamps plus one 600 W infrared lamp to heat large concrete panels for 20 h, enabling the assessment of surface-temperature evolution and heat flux transmission through geopolymer-coated building envelopes [53]. Zhou et al. (2024) examined the heat storage and release behavior of modified mortars using a controlled thermal-cycling box between 5 and 55 °C. During each cycle, specimens were subjected to programmed heating and subsequent cooling with thermocouples to capture the internal/external thermal response of the material [54].

In this study, a concrete slab (20 cm × 20 cm × 7 cm) was placed inside an insulated wooden box, with a 3 cm-thick foam board lining to reduce ambient interference. A 100 W full-spectrum solar lamp (P95100, REPTI ZOO, Fountain Valley, CA, USA) was used to simulate sunlight. Temperatures were measured by thermocouples (TK-39, Hila International Inc., Taipei, Taiwan) embedded at depths of 0 cm (top surface), 1 cm, 3 cm, 5 cm, and 7 cm (bottom surface). Two flexible thermopile-type heat flux sensors (FHF05-50 × 50, Hukseflux Thermal Sensors B.V., The Netherlands; nominal sensitivity 13 µV/(W/m2), integrated Type-T thermocouple, thickness 0.4 mm) were installed at the center of the upper (top) and lower (bottom) surfaces of the concrete specimen, capturing radiative gain during heating and radiative–convective loss during cooling via the thermopile’s voltage response to the temperature difference across the sensor. A pyranometer (LPPYRA03, Delta Ohm, Padova, Italy) was utilized to ensure the stability of the irradiance during the test. All data were continuously logged using a data logger (CR1000, Campbell Scientific Inc., Logan, UT, USA). Data were recorded continuously at 1 Hz from half an hour before lamp activation until test completion. The test was conducted over a period of 40 h, consisting of 20 h for heating and 20 h for natural cooling. The experimental setup is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Configuration of indoor irradiation test (a) specimen setup; (b) test setup.

3.4. Emissivity Test

The spectral emissivity of concrete specimens was measured using an FTIR (INVENIO, Bruker, Germany) over a wavelength range of 5–15 μm, referring to the procedure reported by Li et al. (2021) [23]. Each specimen (10 cm diameter, 0.7 cm height) was clamped in position and heated to 60 °C, 70 °C, and 80 °C prior to measurement. The spectral emissivity () at a given wavelength () was calculated using Equation (2).

3.5. Thermal Transmittance Test

The thermal transmittance (U-value) of the specimen was calculated by combining the ISO 9869 [55] formulation with standardized surface resistance values recommended by ISO 6946 [56]. Specifically, the internal surface resistance ( m2·K/W) and the external surface resistance ( m2·K/W) were adopted to account for thermal resistances at the air–specimen interfaces. These values, together with the measured material resistance (), were used to compute the ideal thermal transmittance (, in W/m2·K) as shown in Equation (5):

4. Thermal Performance Theory

In this section, the thermal performance of concrete specimens with different MBOFS replacement ratios was derived by the emissivity test, thermal transmittance test, and indoor irradiation test, based on the law of conservation of energy.

4.1. Heat Storage

This part discusses the total and layer-wise heat storage behavior of the specimens. It is assumed that all heat released during the post-irradiation cooling stage originated from thermal energy stored within the material during the preceding heating period.

4.1.1. Total Heat Storage

The total heat storage, denoted as (J), was used as a proxy for the specimen’s overall thermal storage capacity. It was calculated by summing the heat stored at the top, bottom, and lateral surfaces, represented as , , and , respectively, as shown in Equation (6):

This approach is predicated on the assumption that the top and bottom heat fluxes measured by the heat flux sensors are uniformly distributed. For cumulative heat calculations, the signal was integrated using a fixed time step Δt = 30 s. and (J) during the entire cooling period after light-off were calculated by integrating the net heat flux over time, as shown in Equation (7) and Equation (8), respectively:

where and denote the total areas of the top and bottom, respectively (m2); and are the time-dependent net heat fluxes (W/m2) measured at the top and bottom surfaces, respectively; and represent the start and end of the cooling stage, respectively; and is the sampling interval ().

The side surface heat storage, (J), was estimated by assuming that the average heat per unit area on the lateral surfaces is approximately equal to the mean of the accurately measured top- and bottom-surface fluxes, which was then multiplied by , the total area of all four side surfaces (m2), since direct measurement of lateral heat flux is impractical due to non-uniform temperature and boundary conditions on the side faces. is defined as expressed in Equation (9):

4.1.2. Layer-Wise Heat Storage

In this study, the specimen was dissected into four layers, including the top to 1 cm, 1 cm to 3 cm, 3 cm to 5 cm, and 5 cm to bottom. The symbol i represents all four layers. The layer-wise heat storage, (J), combines the heat storage from each surface with weighting factors based on the vertical temperature gradient and layer thickness, given in Equation (10):

The layer-wise side surface heat storage was estimated by first computing the weighted sum of and for each layer, and then using the proportion of this value relative to the total weighted sum across all layers to allocate the total side surface heat storage, . The underlying assumption is that if a layer receives a larger share of heat from the top and bottom surfaces (i.e., a higher value of ), then it is expected to store more heat from the lateral surface (), resulting in a larger weighting factor for the side contribution (). is expressed in Equation (11):

The top-surface weighting factor, , reflects the relative contribution of the top-surface heat input to layer , based on the temperature difference between the average temperature of the layer and the bottom surface, as described in Equation (12). Layers closer to the bottom have smaller contributions from the top surface, as defined in Equation (13). Conversely, the bottom-surface weighting factor, , is determined by the temperature difference between the average temperature of the layer and the top surface, assigning greater weight to layers closer to the bottom, as shown in Equation (14):

where is the thickness of each layer, and is the steady-state average temperature of layer i with boundary temperatures and . and denote the steady-state temperatures at the top and bottom surfaces, respectively. This formulation accounts for both geometric and thermal effects, ensuring that the multilayer heat-energy distribution adheres to physical phenomena.

4.2. Specific Heat Capacity

The specific heat capacity of the specimen, (J/kg·K), was estimated using two approaches. The first, referred to as the direct-estimated specific heat capacity (), was calculated from the total heat storage, , specimen mass, (kg), and the overall effective temperature difference between the initial and final time points of the cooling stage, , as defined in Equation (15). The second, denoted as the thickness-weighted specific heat capacity (), was obtained by averaging the layer-wise specific heat capacities , using their relative thicknesses as weights, where is the total thickness of the specimen (7 cm), as shown in Equation (16).

The effective temperature of the specimen at time t, denoted as (t), was estimated using a volume-weighted average of the top and bottom boundary temperatures of each layer, based on the relative thickness of each layer, as expressed in Equation (17):

where and are the measured temperatures (K) at the upper and lower boundaries of layer i, respectively. and represent the effective temperature of layer i at the start and end of the cooling period.

To evaluate the internal heat distribution, the specimen was divided into horizontal layers, assuming uniform density across all layers. The specific heat capacity of each layer, (J/kg·K), is defined as shown in Equation (18):

where is the corresponding layer-wise heat storage (J), and is the mass of each layer (kg), computed based on its relative thickness , under the assumption of uniform density. and are the effective temperature of layer i at the start and end of the cooling period, respectively.

4.3. Effective Heat-Energy Change

To evaluate the thermal energy absorption and dissipation behaviors of the concrete specimens, the effective heat-energy change over each time interval (J) is defined by Equation (19) as follows:

where is the time interval, and , with unit K, is the effective temperature of the specimen at time .

4.4. Radiative Heat Loss

In this analysis, the specimen was assumed to behave as a gray body, exhibiting constant emissivity that is independent of wavelength. Radiative heat transfer was considered to occur between the specimen surfaces (top, bottom, and lateral) and the surrounding environment. It was assumed that the surface temperatures of each specimen’s surface were uniform at any random instant, and that the heat transfer of the specimen only considered the radiative effect. The surface emissivity was treated as temperature-dependent functions, denoted as and for the top and bottom surfaces, respectively. According to the Stefan–Boltzmann law, the instantaneous radiative heat fluxes at the top surfaces and at the bottom surface during the cooling stage are calculated by Equation (20) and Equation (21), respectively:

where is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant (5.67 × 10−8 W/m2·K4), is the temperature-dependent spectral-averaged emissivity in the 8–13 μm wavelength range, and are the top- and bottom-surface temperatures (K), and and are the corresponding top and bottom environmental temperatures inside the chamber (K), each measured at one shaded reference point.

Since the emissivity of the specimen was measured only at 60 °C, 70 °C, and 80 °C, the emissivity at intermediate temperatures was estimated by linear interpolation between 60–70 °C and 70–80 °C, as shown in Equation (22). For surface temperatures below 60 °C, the emissivity was assumed to be equal to the value measured at 60 °C.

where and are two bounding temperatures (60 °C and 70 °C, or 70 °C and 80 °C), respectively, as .

The radiative heat loss of the specimen was evaluated using the integral approach as in Equations (6)–(8), with the net heat flux replaced by the radiative heat flux. The reorganized formulations are given in Equations (23)–(25):

Equations (23)–(25) describe the heat transfer behavior based on measured specimen-side heat fluxes and do not include a direct comparison with the lamp-emitted heat flux. Together, these parameters characterize the specimen’s ability to store, transmit, and buffer thermal energy under transient boundary conditions, offering insight into its potential performance in real-world building environments.

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents the thermal and mechanical performance of concrete incorporating different replacement ratios of MBOFS. The investigation evaluates key properties, including density, porosity, strength, and thermal transmittance, together with the dynamic thermal responses under indoor heating and radiative-cooling conditions. Furthermore, the influences of MBOFS content on heat loss, specific heat capacity, and emissivity are systematically analyzed.

5.1. Density and Porosity

As shown in Table 4, the oven-dry bulk density of concrete increased from 2228.8 kg/m3 (D-RS) to 2611.5 kg/m3 (D-MS-100) with an increasing MBOFS replacement ratio. This trend is attributed to the higher specific gravity of MBOFS compared with natural aggregates, resulting in greater overall mass and enhanced thermal inertia of the concrete.

Table 4.

Oven-dry bulk density of specimens.

As presented in Table 5, the porosity of the specimens increased linearly with the replacement ratio of MBOFS. The reference mix (D-RS) exhibited a porosity of 14.51%, while porosity gradually increased from 14.59% in D-MS-20 to 19.03% in D-MS-100. This trend suggests that although the overall density increased with higher slag content (Table 4), the micro-structure may have become more porous due to the intrinsic characteristics of the slag particles, such as surface roughness or irregular shape, which can introduce micro voids at the interfacial transition zones.

Table 5.

Porosity of specimens.

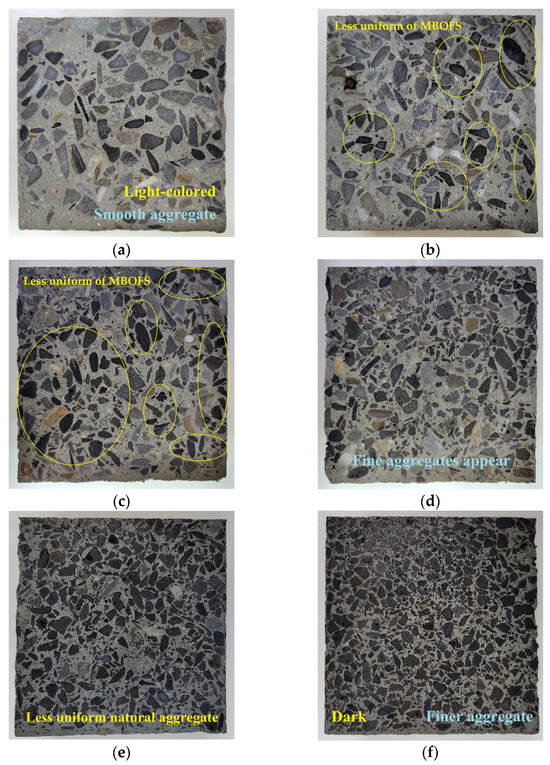

Figure 8 illustrates the cross-sectional morphology of specimens with increasing MBOFS replacement ratios. As the MBOFS content increased, aggregate distribution became progressively more irregular. D-MS-80 exhibited the most heterogeneous texture, characterized by uneven spacing and matrix segregation. This corresponds to the grading deviation observed in Figure 2, where the 80% mix exceeded the ASTM C33/C33M-24a [45] limits due to insufficient fine content and poor gradation. These findings suggest that performance deterioration typically associated with poor aggregate gradation may be mitigated by other beneficial properties of MBOFS, such as high density, absorptance, and emissivity.

Figure 8.

Cross-section morphology of specimens: (a) D-RS exhibiting the lightest color and typical appearance of conventional concrete; (b) D-MS-20, (c) D-MS-40 slight darkening accompanied by a less uniform distribution of MBOFS; (d) D-MS-60, (e) D-MS-80, (f) D-MS-100 pronounced darkening and visibly finer aggregate particle size resulting from the higher replacement levels of natural aggregates with MBOFS.

In contrast, D-MS-20 and D-MS-40 showed localized aggregate accumulation near the casting face, likely due to the higher specific gravity of MBOFS compared to natural aggregates. This sedimentation effect may have led to MBOFS enrichment at the irradiated surface, potentially increasing radiative heat loss and reducing internal heat retention during thermal cycling.

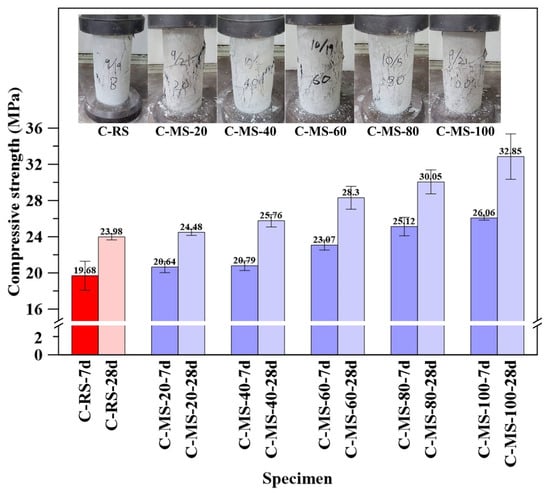

5.2. Compressive Strength

As shown in Figure 9, compressive strength increased with curing age for all specimens, with a more pronounced strength gain observed at higher MBOFS replacement ratios. The reference specimen (C-RS) achieved 19.68 MPa and 23.98 MPa at 7 and 28 days, respectively. In contrast, the C-MS-100 specimen reached the highest 28-day strength of 32.85 MPa.

Figure 9.

Compressive strength of specimens at 7 and 28 days.

Increasing MBOFS replacement levels (0–100%) increased porosity (14.51–19.03%) and heterogeneity, but the angular morphology and superior hardness of MBOFS enhanced mechanical interlock and load transfer at the paste–aggregate interface, improving compressive strength. Aggregate properties and interface quality govern crack propagation, with cracks tending to develop along a weaker interfacial transition zone between aggregate and cement in concrete [57] and MBOFS aggregates enhancing bonding and strength due to their material polarity and mechanical strength [58], while initial defects of aggregates might affect deformation and failure of concrete [59]. As shown in Figure 9, the crack patterns in compressed cylinders align with mesoscale cracking mechanisms simulated by discrete element methods [60], collectively explaining the strength gains with increasing MBOFS replacement.

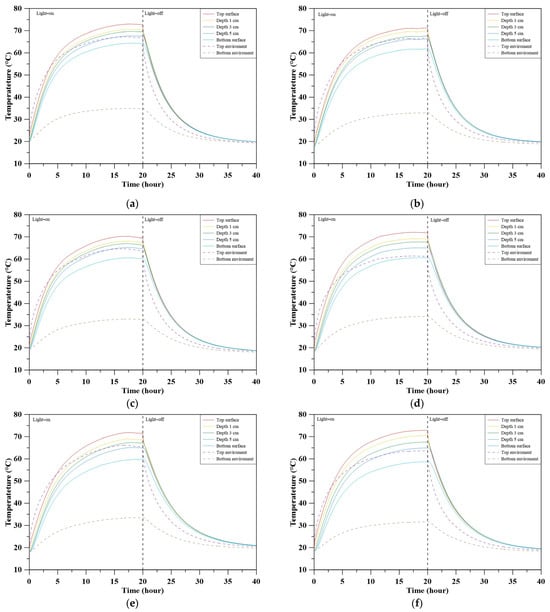

5.3. Indoor Irradiation Test Results

Figure 10 illustrates the transient thermal response of concrete specimens with varying MBOFS replacement ratios during a heating–cooling cycle. During the heating stage (0–20 h), specimens with lower MBOFS content (S-RS and S-MS-20) exhibited a faster surface temperature rise, whereas increasing MBOFS content led to slower heating, indicating improved insulation. During the cooling stage (20–40 h), S-MS-60 showed the steepest temperature drop, suggesting efficient radiative dissipation. In contrast, S-MS-80 and S-MS-100 cooled more slowly, likely due to stronger internal heat retention.

Figure 10.

Temperature changes of specimens: (a) S-RS; (b) S-MS-20; (c) S-MS-40; (d) S-MS-60; (e) S-MS-80; (f) S-MS-100.

Figure 11 presents the steady-state temperature profiles across specimen depths. As MBOFS content increased, internal temperatures declined more significantly, resulting in steeper vertical temperature gradients. The surface-to-bottom temperature difference increased from 8.61 °C (S-RS) to 14.26 °C (S-MS-100), indicating a reduction in internal thermal conductivity. Interestingly, S-MS-20 and S-MS-40 exhibited unexpectedly low surface temperatures despite their relatively low MBOFS content. This anomaly may be due to the higher specific gravity of MBOFS aggregates, which likely caused particle settling during casting (Figure 8b,c). As the irradiated face was the cast bottom surface—typically smoother and richer in cement paste—its potentially higher emissivity may have promoted radiative heat loss and reduced surface heat retention.

Figure 11.

Steady-state temperatures of specimens.

Among all specimens, S-MS-60 exhibited the most balanced thermal performance. It showed sufficient surface heating, effective internal insulation, and the fastest cooling rate, indicating a favorable combination of heat absorption, retention, and dissipation.

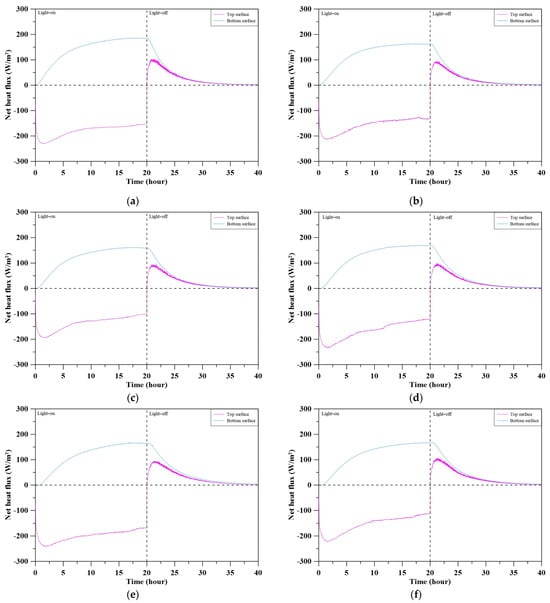

Figure 12 presents the net heat flux profiles at the top and bottom surfaces of concrete specimens with varying MBOFS replacement ratios during a heating–cooling cycle. During the light-on stage, the top surface absorbed heat (negative net flux), while the bottom surface released it (positive flux); after light-off, both surfaces exhibited positive net flux, indicating the release of stored thermal energy. Specimens with lower MBOFS content, such as S-RS and S-MS-20, exhibited larger flux amplitudes (−200 to +120 W/m2) and sharper transitions, whereas higher-replacement specimens showed smoother gradients and reduced thermal responses, consistent with enhanced insulation. Notably, S-MS-20 and S-MS-40 showed lower net heat absorption at the top surface, possibly due to particle settling and the smoother, paste-rich irradiated surface, which may have promoted radiative heat loss. Among all specimens, S-MS-60 demonstrated the most balanced net heat flux profile, reflecting an optimal combination of heat absorption, retention, and dissipation.

Figure 12.

Net heat flux changes at the top and bottom surfaces of specimens: (a) S-RS; (b) S-MS-20; (c) S-MS-40; (d) S-MS-60; (e) S-MS-80; (f) S-MS-100.

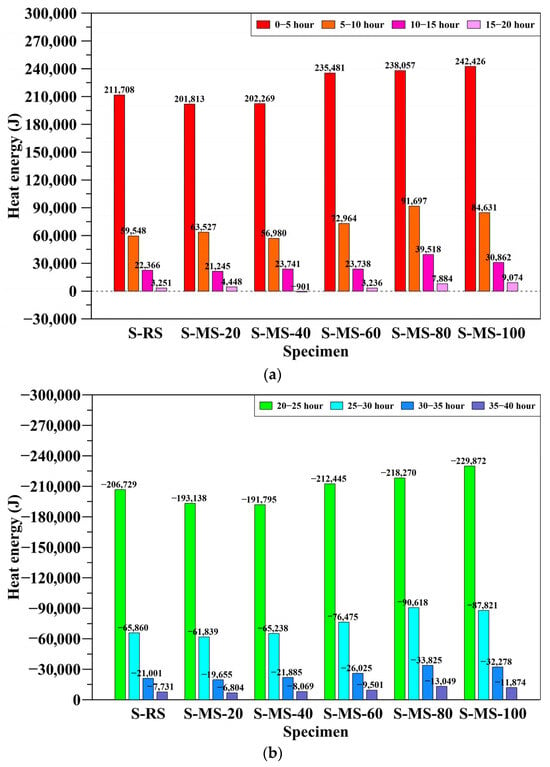

5.3.1. Heat Storage

Table 6 and Table 7 present the total and layer-specific heat storage capacities of the concrete specimens during the heating–cooling cycle. At low MBOFS replacement levels (S-MS-20 and S-MS-40), total heat storage was slightly lower than that of the control (S-RS), reflecting their reduced net heat flux absorption during the heating stage. This suggests that at low MBOFS replacement levels, the aggregates may not have formed an effective thermal storage network. In addition, Figure 4 in Section 5.1 shows localized aggregate accumulation, particularly in MS-20 and MS-40. This surface-enriched distribution may partially explain the unexpectedly low surface temperatures and the diminished thermal storage observed in S-MS-20 and S-MS-40 during the indoor irradiation tests.

Table 6.

Total heat storage of specimens.

Table 7.

Layer-wise heat storage of specimens.

In contrast, specimens with 60% or higher MBOFS content exhibited substantial increases in total heat storage. All three components (, , and ) show progressive growth with increasing replacement ratio. These enhancements indicate improved internal heat retention and more efficient thermal energy absorption, likely resulting from strengthened thermal connectivity and mass-related effects at higher MBOFS contents.

5.3.2. Specific Heat Capacity

Table 8 presents the layer-specific heat storage and specific heat capacity of the specimens. Both parameters generally increased with depth and MBOFS replacement ratio, reflecting enhanced thermal accumulation and storage capability. Specimens with 60–100% MBOFS consistently outperformed the control (S-RS), while S-MS-20 and S-MS-40 exhibited lower capacities, suggesting limited thermal network development at low replacement levels.

Table 8.

Specific heat capacity of specimens.

Among the high-replacement specimens, S-MS-80 exhibited the highest specific heat capacity, with a direct-estimated value of 1027.42 J/kg·K and a thickness-weighted value of 1037.60 J/kg·K. This performance is likely attributable to its smaller temperature drop during cooling (41–49 °C), which increased the calculated heat capacity per unit temperature. In contrast, S-MS-100 showed a slightly lower value, despite its higher total heat storage, due to a greater temperature decline (42–51 °C) and larger mass, which diluted the temperature-normalized storage estimate.

Minor variations in ambient conditions may have also contributed to this difference. S-MS-80 cooled under a slightly warmer air temperature range (18.41–19.23 °C) than S-MS-100 (17.78–18.11 °C) and maintained a higher final temperature at 40 h (20.9 °C vs. 19.5 °C). Although these factors may introduce some uncertainty, all calculated specific heat capacities fall within the commonly reported range for conventional concrete (900–1000 J/kg·K) [61,62], confirming the physical validity of the results.

Additionally, Figure 2 illustrates that the aggregate grading of MS-80 and MS-100 exceeds the ASTM C33/C33M-24a [45] limits. Despite this discontinuous gradation, both mixes exhibited favorable thermal and mechanical performance, with MS-80 achieving the highest specific heat capacity and MS-100 displaying the greatest compressive strength (Section 5.2). This suggests that the performance deterioration typically associated with poor aggregate grading may be offset by the intrinsic properties of MBOFS—such as its high density, strong absorptance, and elevated emissivity—which collectively enhance heat storage and structural behavior. Overall, these results demonstrate that even at high replacement ratios, where grading deviation becomes more pronounced, the thermal accumulation capacity and mechanical robustness of MBOFS concrete remain well preserved.

The direct-estimated specific heat capacity, derived from total heat storage, mass, and overall effective temperature drop, serves as a bulk-level indicator. In contrast, the thickness-weighted value accounts for layer-specific differences, incorporating the relative thickness of each layer. Across specimens, the two estimates were in close agreement, with deviations generally within ±3%, indicating moderate internal temperature gradients and validating the reliability of the layer-wise approach. The strong alignment between the two measures—especially in S-MS-80—further underscores the consistency of its thermal performance across depth.

5.3.3. Effective Heat-Energy Change

Figure 13 illustrates the change in heat energy over time. During the heating stage (0–20 h), S-MS-60, S-MS-80, and S-MS-100 exhibited higher energy uptake, especially within the first 10 h. In the cooling stage (20–40 h), they also showed greater energy release.

Figure 13.

Effective thermal energy change of each specimen over time: (a) heating stage; (b) cooling stage.

However, heat loss alone does not reflect dissipation efficiency. Surface-temperature data (Figure 10) reveal that S-MS-60 experienced the steepest drop, indicating more effective radiative cooling. In contrast, S-MS-80 cooled more slowly, suggesting delayed internal heat release. These results underscore the need to consider both heat-energy change and surface temperature in evaluating thermal behavior.

5.4. Thermal Radiation

Thermal radiation is a key mechanism that governs the passive cooling behavior of concrete surfaces after external heating. In this study, most radiative parameters, including emissivity, radiative heat flux, and total heat loss, were estimated based on measured surface temperatures and established thermophysical equations, rather than directly measured.

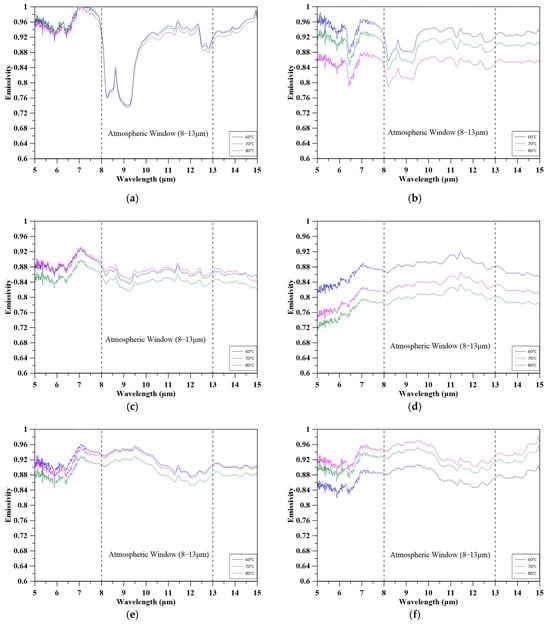

5.4.1. Emissivity

Figure 14 and Figure 15 illustrate the spectral and average emissivity of concrete specimens at 60 °C, 70 °C, and 80 °C within the mid-infrared atmospheric window (8–13 μm), which is critical for radiative heat dissipation. Compared to the reference specimen (E-RS), most MBOFS-modified concretes exhibited higher emissivity, particularly in this wavelength range. While E-RS maintained stable emissivity across temperatures, MBOFS specimens showed varying thermal responses.

Figure 14.

Emissivity at 60 °C, 70 °C, and 80 °C of specimens: (a) E-RS; (b) E-MS-20; (c) E-MS-40; (d) E-MS-60; (e) E-MS-80; (f) E-MS-100.

Figure 15.

Average emissivity (8–13 μm) at 60 °C, 70 °C, and 80 °C of specimens.

The emissivity of most common rock-forming minerals, such as quartz and feldspar, is generally considered nearly temperature-independent in the mid-infrared (MIR) region. However, in the present study, the E-MS-80 and E-MS-100 exhibited a measurable increase in emissivity with rising surface temperature (60–80 °C) within the 8–13 μm atmospheric window, whereas lower-replacement mixtures (E-MS-20 and E-MS-60) showed decreases. Although the exact mechanism underlying this temperature-dependent behavior requires further investigation, several factors are likely to contribute simultaneously:

- The observed temperature-dependent emissivity is presumably attributed primarily to the mineralogical composition of MBOFS. The dominant crystalline phases, calcite (CaCO3), calcium silicate (Ca2SiO4), and wüstite (FeO), exhibit lattice and molecular vibrational bands within the mid-infrared range [63,64,65]. Although these minerals are macroscopically non-polar (i.e., they lack a permanent macroscopic dipole moment), their ionic bonds generate well-defined vibrational modes that contribute significantly to absorption. According to Kirchhoff’s law of thermal radiation, the material’s spectral emissivity equals its spectral absorptivity at thermodynamic equilibrium [66]. This relationship dictates the inverse correlation between strong absorption bands (low emissivity) and spectral features like the Christiansen Feature (high emissivity). Planck’s law further provides the blackbody spectral radiance. The combination of the material’s characteristic spectral emissivity and the blackbody spectral radiance explains the strong thermal emission features observed within the 8–13 μm atmospheric window [67].

- Surface roughness, porosity, and the potential desorption of physically adsorbed water may influence the effective emissivity in the MIR range. Although direct experimental evidence for MBOFS concrete is currently limited, previous studies on other materials have shown that surface porosity can visibly affect emissivity, suggesting that micro-structural features could contribute as a secondary factor [68].

These observations are consistent with the average emissivity values shown in Figure 15. E-RS had the lowest and most stable values (0.86–0.87), whereas all modified specimens exceeded this baseline. E-MS-100 reached the highest emissivity at 80 °C (0.94), followed by E-MS-80 (0.92), both demonstrating strong radiative potential. Conversely, E-MS-60 exhibited the greatest decline (from 0.89 to 0.80), highlighting the importance of considering both emissivity magnitude and thermal stability when evaluating radiative-cooling performance. Taken together, the observed increase in emissivity for the E-MS-80 and E-MS-100 is most reasonably interpreted as the combined result of mineralogical composition and, possibly, micro-structural characteristics, rather than a single isolated mechanism.

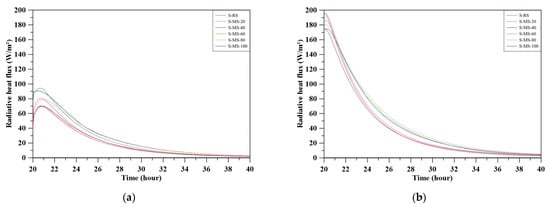

5.4.2. Radiative Heat Loss

The instantaneous radiative heat flux, as shown in Figure 16, exhibits a time-dependent decrease for both the top and bottom surfaces, indicating continuous specimen cooling following light-off. The bottom surface consistently exhibited higher flux values than the top, primarily due to a greater temperature gradient with the ambient environment.

Figure 16.

Instantaneous radiative heat flux during cooling for specimens: (a) top surface; (b) bottom surface.

On the top surface (Figure 16a), the flux peaked shortly after the onset of cooling and then declined. Specimens with higher MBOFS replacement levels (e.g., S-MS-80 and S-MS-100) exhibited higher peak fluxes and slower decay rates, indicating enhanced surface emissivity and improved thermal retention.

In contrast, the bottom surface (Figure 16b) displayed a relatively uniform exponential decay across all specimens. Nevertheless, specimens with lower MBOFS replacement ratios cooled more rapidly, whereas those with higher replacement levels showed slower flux reduction.

Since radiative heat flux is driven by the surface–ambient temperature difference, and initial temperatures varied between specimens, the results represent relative cooling behavior under consistent heating conditions rather than absolute comparisons of emissivity performance.

Table 9 summarizes the total radiative heat loss of the specimens during the cooling stage, with contributions from the top (), bottom (), and side surfaces (). In general, total radiative loss () increased with MBOFS replacement ratio, peaking at 360,037 J for S-MS-80. Most modified specimens exhibited greater radiative losses than the reference specimen S-RS (286,020 J), reflecting their enhanced thermal storage and elevated emissivity. An exception was S-MS-40, which showed a slightly lower value (284,002 J), suggesting a non-linear relationship between replacement ratio and radiative performance. Notably, S-MS-60 to S-MS-100 demonstrated substantially higher top and side surface losses, indicative of more effective outward radiation.

Table 9.

Total radiative heat loss of specimens.

These estimates were obtained using interpolated emissivity values at 60 °C, 70 °C, and 80 °C, but a constant emissivity corresponding to 60 °C was applied throughout the entire cooling period. This simplification overlooks the temperature dependence of emissivity, introducing a certain degree of estimation error. Consequently, the radiative heat loss trends in Table 9 deviate slightly from those in Table 6, which more directly reflect actual heat dissipation via net heat flux measurements. Nevertheless, the differences between radiative loss and total heat storage values remained within ±10% for all specimens, with most values falling within ±5%, indicating a strong overall consistency. Thus, despite methodological limitations, the radiative loss estimates remain valid and provide meaningful insight into the specimens’ thermal dissipation behavior.

5.5. Thermal Transmittance

Thermal transmittance, also known as the U-value, measures the ease with which heat flows through a building wall, window, or roof, indicating its insulating ability. Table 10 presents the ideal thermal transmittance () and material resistance () of concrete specimens with varying MBOFS replacement ratios. As the replacement increased from 0% (T-RS) to 100% (T-MS-100), rose from 0.034 to 0.069 m2·K/W, while declined from 3.644 to 3.235 W/m2·K. This inverse trend indicates improved insulation performance with higher MBOFS content, consistent with the standardized assumptions in ISO 6946. The higher heat storage capacity and higher emissivity (thermal radiation) of T-MS-100 suppress thermal transmittance, thus improving the thermal resistance of the building walls.

Table 10.

Thermal transmittance of specimens.

6. Conclusions and Suggestions

This study systematically evaluated the thermal and mechanical behavior of concrete incorporating modified basic oxygen furnace slag (MBOFS) as a sustainable alternative to natural aggregates. In summary, the integration of MBOFS into concrete not only improves radiative cooling and insulation but also enhances structural strength and thermal storage. These combined effects make MBOFS concrete a promising material for reducing UHI intensity and supporting the sustainable reutilization of steelmaking by-products in the construction industry. Key findings are summarized as follows:

- Optical properties of aggregates: MBOFS aggregates exhibited excellent radiative-cooling potential, with high mid-infrared emissivity (up to 95.92% in the 8–13 μm atmospheric window), low solar reflectance (25–35%), and negligible transmittance (<0.2%). These properties support enhanced thermal radiation while minimizing solar heat gain.

- Density, porosity, and mechanical strength: With increasing MBOFS content, specimen density rose from 2229 to 2611 kg/m3, while porosity increased modestly from 14.5% to 19.0%. Despite this, compressive strength improved, reaching 32.85 MPa at 100% replacement, confirming the structural viability of MBOFS concrete.

- Heat storage and specific heat capacity: High-replacement specimens (S-MS-80 and S-MS-100) exhibited the greatest total and layer-wise heat storage, as well as the highest specific heat capacities (up to 1037 J/kg·K), indicating superior thermal accumulation. In contrast, low-replacement mixes (S-MS-20 and S-MS-40) showed limited heat retention, likely due to uneven internal packing and poor thermal connectivity.

- Emissivity and radiative heat dissipation: MBOFS-modified concretes showed elevated emissivity values across all temperatures compared to the reference mixture. Specimens with 80–100% MBOFS exhibited greater radiative heat loss, particularly from the top and side surfaces, driven by both high emissivity and enhanced thermal mass.

- Cooling dynamics and comparative performance: S-MS-60 demonstrated the fastest cooling rate and most balanced thermal behavior, making it suitable for applications requiring rapid surface-temperature reduction. However, higher replacement ratios (S-MS-80 and S-MS-100) delivered superior cumulative thermal and mechanical performance, supporting their use in energy storage-oriented envelope systems.

- Thermal performance indicators: Thermal transmittance decreased with MBOFS content, from 3.644 to 3.235 W/m2·K. The higher heat storage capacity and higher emissivity (thermal radiation) suppress thermal transmittance, thus improving the thermal resistance of the building walls. These shifts suggest that MBOFS enhances the thermal resistance, improving its suitability for passive thermal regulation.

Given its reduced thermal transmittance, enhanced radiative-cooling capability, and 28-day compressive strength exceeding 32 MPa, MBOFS concrete shows strong potential for practical applications. Suitable uses might include the following: (i) non-structural or semi-structural building envelopes (e.g., façades, rooftop slabs) in hot regions to mitigate urban heat island effects; (ii) mass-concrete elements requiring high thermal inertia to moderate diurnal temperature fluctuations, such as parking areas and port pavements; and (iii) precast cladding or pavement panels where rapid surface-temperature reduction and waste valorization are desired. Replacement levels of 80–100% provide the greatest benefits in heat storage capacity, radiative-cooling performance, and mechanical behavior. For applications in categories (i) and (ii), a two-stage casting approach is recommended to maximize radiative-cooling performance while avoiding structural uncertainty. The structural bottom layer should be cast with conventional concrete, followed by a top layer of MBOFS concrete placed before the initial set of the underlying layer.

Despite these advantages, several engineering considerations must be acknowledged. At high replacement ratios (≥80%), the increased density and angularity of MBOFS aggregates may reduce workability, requiring adjustments in admixture dosage or mixing procedures to avoid segregation or excessive compaction effort. In addition, the long-term durability of MBOFS concrete, such as its resistance to cyclic thermal loading, freeze–thaw damage, carbonation, and sulfate attack, has not yet been fully established and warrants further investigation.

Author Contributions

J.-Y.S.: data curation, formal analysis, validation, writing—original draft. Y.-W.L.: data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft. Y.-F.L.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing—review and editing. C.-H.H.: formal analysis, funding acquisition, validation, writing—review and editing. S.-H.C.: data curation, formal analysis. W.-H.L.: validation, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the “Research Center of Energy Conservation for New Generation of Residential, Commercial, and Industrial Sectors” from the Ministry of Education in Taiwan under contract No. L7131101-19.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. Monthly Global Climate Report for Annual 2024. January 2025. Available online: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/monthly-report/global/202413 (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Kweku, D.W.; Bismark, O.; Maxwell, A.; Desmond, K.A.; Danso, K.B.; Oti-Mensah, E.A.; Quachie, A.T.; Adormaa, B.B. Greenhouse Effect: Greenhouse Gases and Their Impact on Global Warming. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2018, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuttler, W. The Urban Climate–Basic and Applied Aspects. In Urban Ecology: An International Perspective on the Interaction between Humans and Nature; Marzluff, J.M., Shulenberger, E., Endlicher, W., Alberti, M., Bradley, G., Ryan, C., Simon, U., ZumBrunnen, C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Milesi, C.; Churkina, G. Measuring and Monitoring Urban Impacts on Climate Change from Space. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajerani, A.; Bakaric, J.; Jeffrey-Bailey, T. The Urban Heat Island Effect, Its Causes, and Mitigation, with Reference to the Thermal Properties of Asphalt Concrete. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 197, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulpiani, G. On the Linkage between Urban Heat Island and Urban Pollution Island: Three-Decade Literature Review towards a Conceptual Framework. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, A.M. Energy, Environment and Sustainable Development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2008, 12, 2265–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Cui, G. Influence of Spectral Characteristics of the Earth’s Surface Radiation on the Greenhouse Effect: Principles and Mechanisms. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 244, 117908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettler, J.N.; Quanz, S.P.; Helled, R.; Olson, S.L.; Schwieterman, E.W. Earth as an exoplanet. II. Earth’s time-variable thermal emission and its atmospheric seasonality of bioindicators. Astrophys. J. 2023, 946, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Des Marais, D.J.; Harwit, M.O.; Jucks, K.W.; Kasting, J.F.; Lin, D.N.; Lunine, J.I.; Schneider, J.; Traub, W.A.; Woolf, N.J. Remote sensing of planetary properties and biosignatures on extrasolar terrestrial planets. Astrobiology 2002, 2, 153–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, M.; Schreier, F.; García, S.G.; Kitzmann, D.; Patzer, B.; Rauer, H.; Trautmann, T. Infrared radiative transfer in atmospheres of Earth-like planets around F, G, K, and M stars-II. Thermal emission spectra influenced by clouds. Astron. Astrophys. 2013, 557, A46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlosena, L.; Ruiz-Pardo, Á.; Feng, J.; Irulegi, O.; Hernández-Minguillón, R.J.; Santamouris, M. On the Energy Potential of Daytime Radiative Cooling for Urban Heat Island Mitigation. Sol. Energy 2020, 208, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfeey, A.M.M.; Chau, H.W.; Sumaiya, M.M.F.; Wai, C.Y.; Muttil, N.; Jamei, E. Sustainable Mitigation Strategies for Urban Heat Island Effects in Urban Areas. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M.; Yun, G.Y. Recent Development and Research Priorities on Cool and Super Cool Materials to Mitigate Urban Heat Island. Renew. Energy 2020, 161, 792–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Aili, A.; Zhai, Y.; Xu, S.; Tan, G.; Yin, X.; Yang, R. Radiative Sky Cooling: Fundamental Principles, Materials, and Applications. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2019, 6, 021306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Pérez, I.; Álvarez, G.; Xamán, J.; Zavala-Guillén, I.; Arce, J.; Simá, E. Thermal Performance of Reflective Materials Applied to Exterior Building Components—A Review. Energy Build. 2014, 80, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, J.; Sailor, D.J. Role of Pavement Radiative and Thermal Properties in Reducing Excess Heat in Cities. Sol. Energy 2022, 242, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaeemehr, B.; Jandaghian, Z.; Ge, H.; Lacasse, M.; Moore, T. Increasing Solar Reflectivity of Building Envelope Materials to Mitigate Urban Heat Islands: State-of-the-Art Review. Buildings 2023, 13, 2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; Huang, C.H.; Li, Y.F.; Lee, W.H.; Cheng, T.W. Utilization of Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag in Geopolymeric Coating for Passive Radiative Cooling Application. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Qian, G.; Yu, H.; Lei, R.; Ge, J.; Dai, W.; Zhong, Y.; Huang, L. Research on thermal conduction of steel slag-modified asphalt mixtures considering aggregate properties. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauser, C.; Huenges, E. Thermal conductivity of rocks and minerals. Rock Phys. Phase Relat. A Handb. Phys. Constants 1995, 3, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Steel Association. Raw Materials. Available online: https://worldsteel.org/other-topics/raw-materials/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Li, Y.F.; Yang, P.A.; Wu, C.H.; Cheng, T.W.; Huang, C.H. A Study on Radiation Cooling Effect on Asphalt Concrete Pavement Using Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag to Replace Partial Aggregates. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Sha, A.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Li, J.; Liu, H. Thermal Conductivity Evaluation and Road Performance Test of Steel Slag Asphalt Mixture. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.H.; Lee, Y.C.; Sheu, B.L. Application and Breakthrough of BOF Slag Modification Technique. China Steel Tech. Rep. 2015, 28, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kambole, C.; Paige-Green, P.; Kupolati, W.K.; Ndambuki, J.M.; Adeboje, A.O. Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag for Road Pavements: A Review of Material Characteristics and Performance for Effective Utilisation in Southern Africa. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 148, 618–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Steel Association. Total Production of Crude Steel. January 2025. Available online: https://worldsteel.org/data/annual-production-steel-data/?ind=P1_crude_steel_total_pub/CHN/IND (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Matsuura, H.; Yang, X.; Li, G.; Yuan, Z.; Tsukihashi, F. Recycling of Ironmaking and Steelmaking Slags in Japan and China. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2022, 29, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K.; Sasaki, K. Occurrence of Steel Converter Slag and Its High Value-Added Conversion for Environmental Restoration in China: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 373, 133876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Piloneta, M.; Terrados-Cristos, M.; Álvarez-Cabal, J.V.; Vergara-González, E. Comprehensive analysis of steel slag as aggregate for road construction: Experimental testing and environmental impact assessment. Materials 2021, 14, 3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lun, Y.; Liu, S.; Luo, X. Mechanical Mechanism for Expansion and Crack of Mortars Containing Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag Sand. Mater. Res. Innov. 2015, 19, S5-865–S5-869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodor, M.; Santos, R.M.; Cristea, G.; Salman, M.; Cizer, Ö.; Iacobescu, R.I.; Chiang, Y.W.; van Balen, K.; Vlad, M.; van Gerven, T. Laboratory Investigation of Carbonated BOF Slag Used as Partial Replacement of Natural Aggregate in Cement Mortars. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 65, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.T.; Tsai, C.J.; Chen, J.; Liu, W. Feasibility and Characterization Mortar Blended with High-Amount Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag. Materials 2018, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omur, T.; Miyan, N.; Kabay, N.; Özkan, H. Utilization and Optimization of Unweathered and Weathered Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag Aggregates in Cement Based Mortar. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 64, 105634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.C.; Yang, C.C.; Tsai, L.W.; Yue, M.T. The Application and Breakthrough of BOF Slag Modification Technique in CSC. Min. Metall. 2014, 58, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Su, T.-H.; Yang, H.-J.; Lee, Y.-C.; Shau, Y.-H.; Takazawa, E.; Lin, M.-F.; Mou, J.-L.; Jiang, W.-T. Reductive Heating Experiments on BOF-Slag: Simultaneous Phosphorus Re-Distribution and Volume Stabilization for Recycling. Steel Res. Int. 2016, 87, 1511–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Hu, X.; Chou, K.C. Oxidative Modification of Industrial Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag for Recover Iron-Containing Phase: Study on Phase Transformation and Mineral Structure Evolution. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 171, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Li, G.; Li, Y.; Li, T.; Yuan, C.; Liu, Y. Thermodynamics and Kinetics on Hot State Modification of BOF Slag by Adding SiO2. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2023, 54, 1131–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motz, H.; Geiseler, J. Products of Steel Slags—An Opportunity to Save Natural Resources. Waste Manag. 2001, 21, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baalamurugan, J.; Kumar, V.G.; Padmapriya, R.; Raja, V.B. Recent Applications of Steel Slag in Construction Industry. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 2865–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zago, S.C.; Vernilli, F.; Cascudo, O. The Reuse of Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag as Concrete Aggregate to Achieve Sustainable Development: Characteristics and Limitations. Buildings 2023, 13, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Shukla, S. Utilization of Steel Slag Waste as Construction Material: A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 78, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E1621-22; Standard Guide for Elemental Analysis by Wavelength Dispersive X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.astm.org/e1621-22.html (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- ASTM E3294-23; Standard Guide for Forensic Analysis of Geological Materials by Powder X-ray Diffraction. International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.astm.org/e3294-23.html (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- ASTM C33/C33M-24a; Standard Specification for Concrete Aggregates. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.astm.org/c0033_c0033m-24a.html (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Popovics, S.; Mather, B. Aggregate Grading and the Internal Structure of Concrete. In Highway Research Record No. 441: Grading of Concrete Aggregates; Highway Research Board, National Academy of Science: Washington, DC, USA, 1973; pp. 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Wang, Z.H.; Kaloush, K.E. Environmental Impacts of Reflective Materials: Is High Albedo a “Silver Bullet” for Mitigating Urban Heat Island? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 830–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekhontsev, S.N.; Prokhorov, A.V.; Hanssen, L.M. Experimental Characterization of Blackbody Radiation Sources. In Radiometric Temperature Measurements II: Applications; Zhang, Z.M., Tsai, B.K., Machin, G., Eds.; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 43, pp. 57–129. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai, T.; Satō, T. Temperature Dependence of Vibrational Spectra in Calcite by Means of Emissivity Measurement. Phys. Rev. B 1971, 4, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I. Leveraging Phonon Polariton Modes in Polar Materials for Selective Thermal Emission and Absorption. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, USA, 2021. OCLC No. 1287936739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C642-21; Standard Test Method for Density, Absorption, and Voids in Hardened Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.astm.org/c0642-21.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- ASTM C39/C39M-24; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.astm.org/c0039_c0039m-24.html (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Li, Y.-F.; Xie, Y.-X.; Syu, J.-Y.; Huang, C.-H.; Tsai, H.-H.; Cheng, T.-W.; Chen, Y.-C.; Lee, W.-H. A Study on the Influence of the Next Generation Colored Inorganic Geopolymer Material Paint on the Insulation Measurement of Concrete Building Shell. Sustainability 2021, 14, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, Z.; Tan, J. Heat Storage Properties of the Cement Mortar Incorporated with Composite Phase Change Material. Appl. Energy 2013, 103, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9869-2:2018; Thermal Insulation—Building Elements—In-Situ Measurement of Thermal Resistance and Thermal Transmittance—Part 2: Infrared Method for Frame Structure Dwelling. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/67673.html (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- EN ISO 6946:2017; Building Components and Building Elements—Thermal Resistance and Thermal Transmittance—Calculation Methods. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/65708.html (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Awoyera, P.O.; Kırgız, M.S. Mineralogy and interfacial transition zone features of recycled aggregate concrete. In The Structural Integrity of Recycled Aggregate Concrete Produced with Fillers and Pozzolans; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2022; pp. 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Lin, H.S.; Syu, J.Y.; Lee, W.H.; Huang, C.H.; Tsai, Y.K.; Shvarzman, A. Investigating the Static and Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Incorporating Recycled Carbon Fiber and Modified Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag Aggregate. Recycling 2025, 10, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Liu, M.M.; Song, H.F.; Guan, W.; Yan, H.M. Influence of initial defects on deformation and failure of concrete under uniaxial compression. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2020, 234, 107106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Mediamartha, B.; Yu, S. Simulation of the Mesoscale Cracking Processes in Concrete Under Tensile Stress by Discrete Element Method. Materials 2025, 18, 2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Zou, R.; Jin, F. Experimental Study on Specific Heat of Concrete at High Temperatures and Its Influence on Thermal Energy Storage. Energies 2016, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.H.; Beaucour, A.L.; Ortola, S.; Noumowé, A. Experimental Study on the Thermal Properties of Lightweight Aggregate Concretes at Different Moisture Contents and Ambient Temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 151, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; Dusseault, M.; Xu, B.; Michaelian, K.H.; Poduska, K.M. Photoacoustic Detection of Weak Absorp-tion Bands in Infrared Spectra of Calcite. Appl. Spectrosc. 2021, 75, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, P.; Kirkpatrick, R.J.; Poe, B.; McMillan, P.F.; Cong, X. Structure of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H): Near-, Mid-, and Far-infrared spectroscopy. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1999, 82, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrettle, F.; Kant, C.; Lunkenheimer, P.; Mayr, F.; Deisenhofer, J.; Loidl, A. Wüstite: Electric, thermodynamic and optical properties of FeO. Eur. Phys. J. B 2012, 85, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salihoglu, H.; Xu, X. Near-field radiative heat transfer enhancement using natural hyperbolic material. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2019, 222, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Rada, J.; Tian, Y.; Han, Y.; Lai, Z.; McCabe, M.F.; Gan, Q. Radiative cooling for energy sustainability: Materials, systems, and applications. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2022, 6, 090201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineo, S.; Pappalardo, G. Rock emissivity measurement for infrared thermography engineering geological ap-plications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.