A Study on Thermal Performance for Building Shell of Modified Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag Replacing Partial Concrete Aggregate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Properties

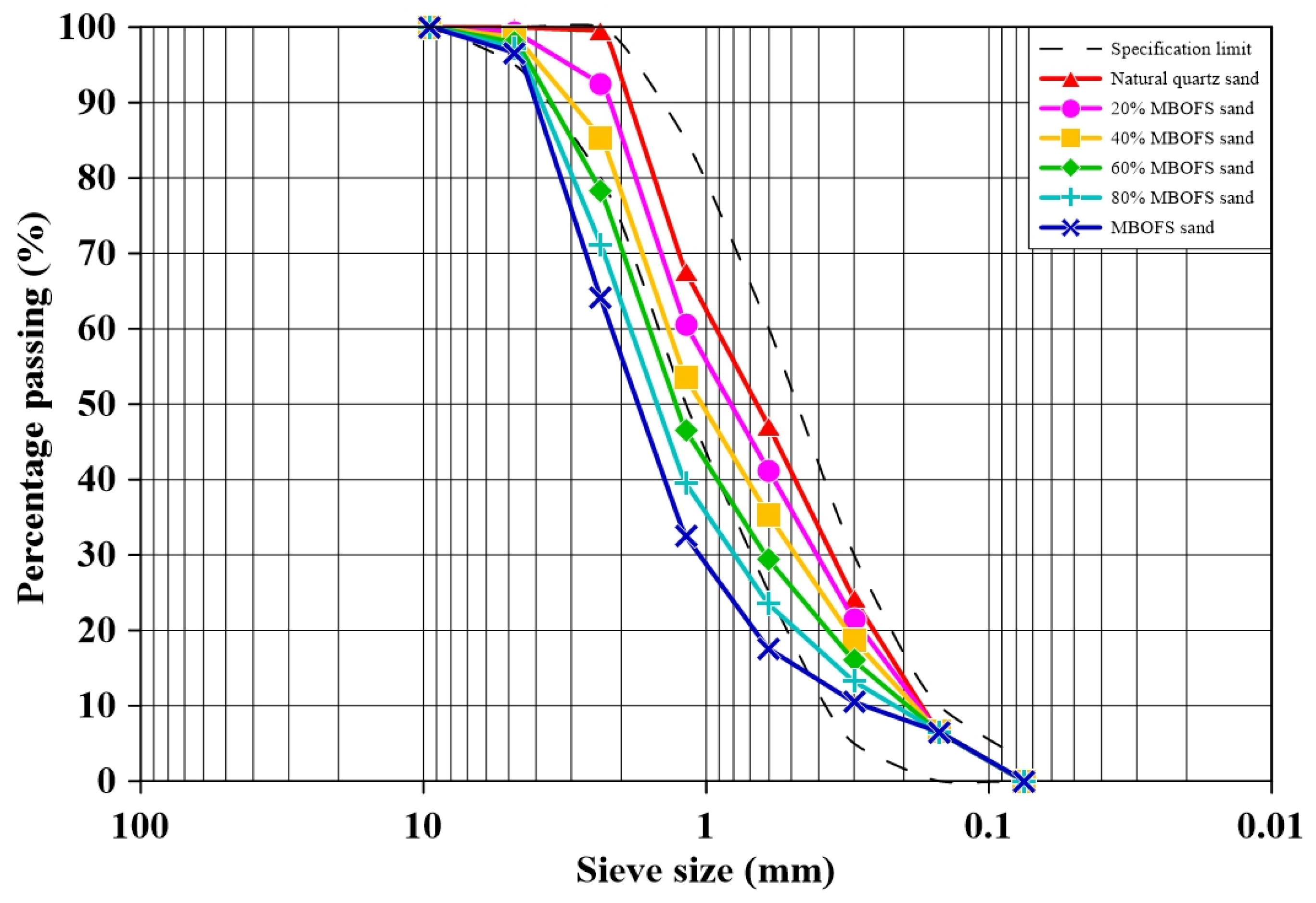

2.1. Cement and Aggregates

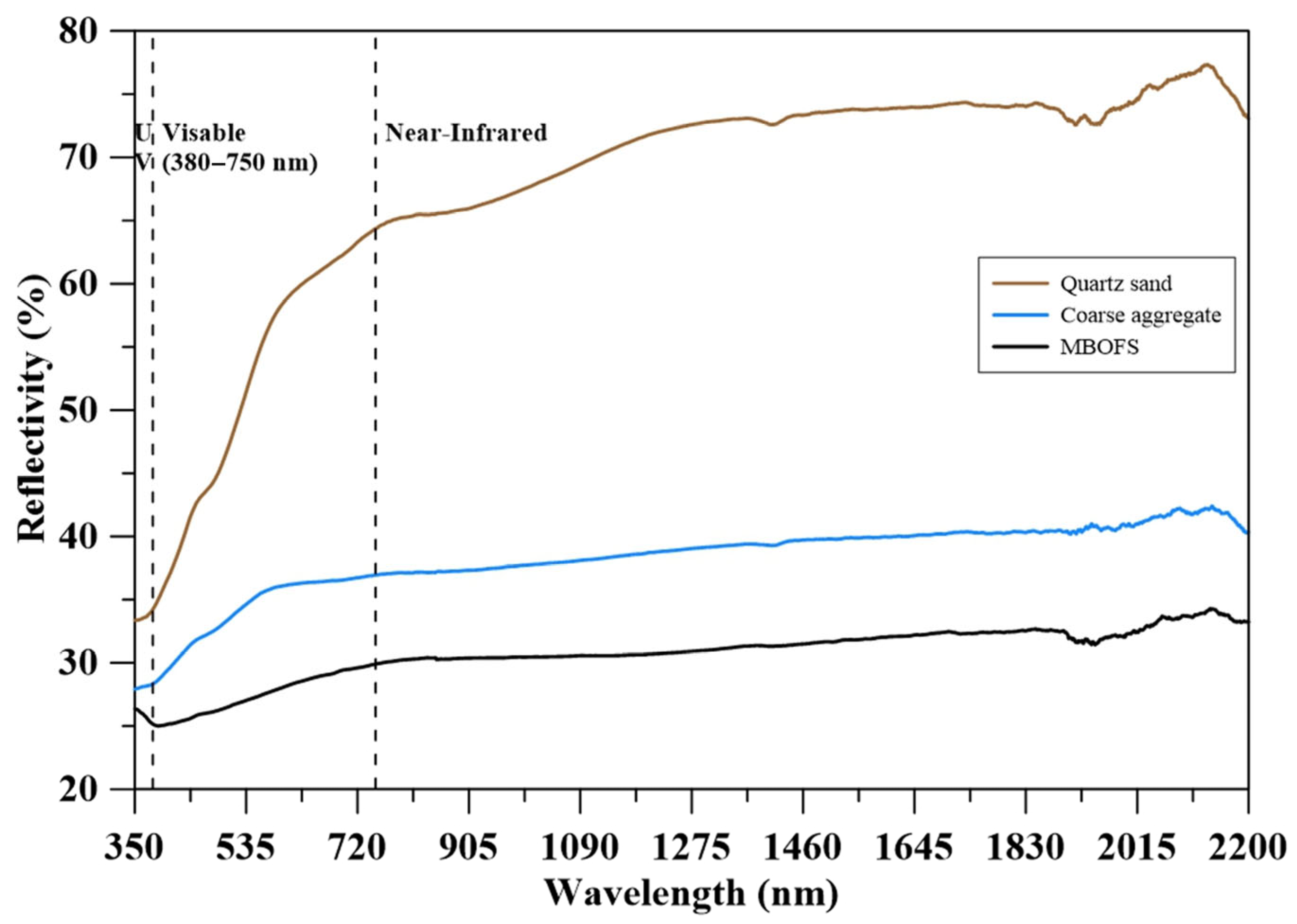

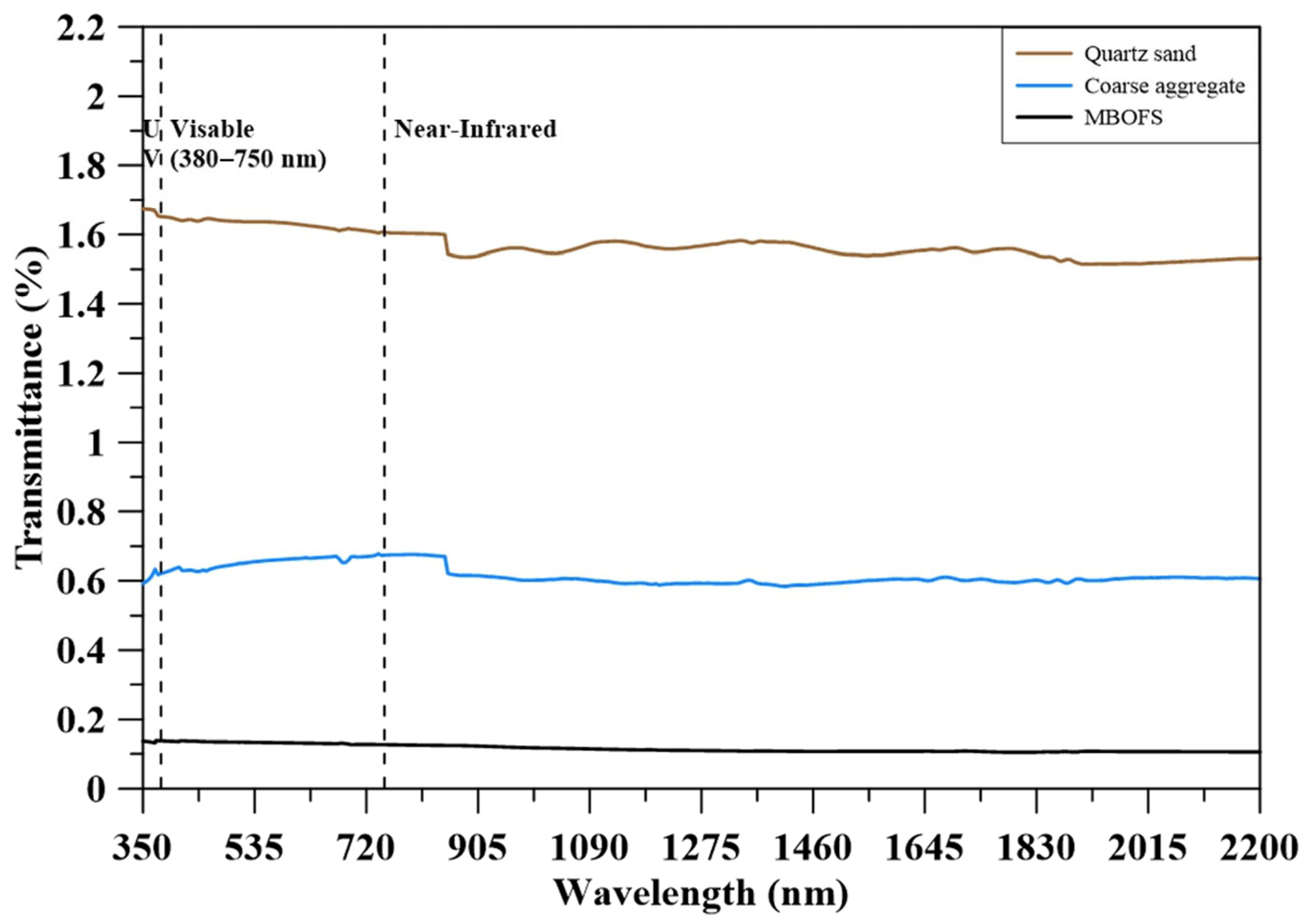

2.2. Optical Properties of Aggregates

2.2.1. Reflectivity

2.2.2. Transmittance

2.2.3. Absorptance

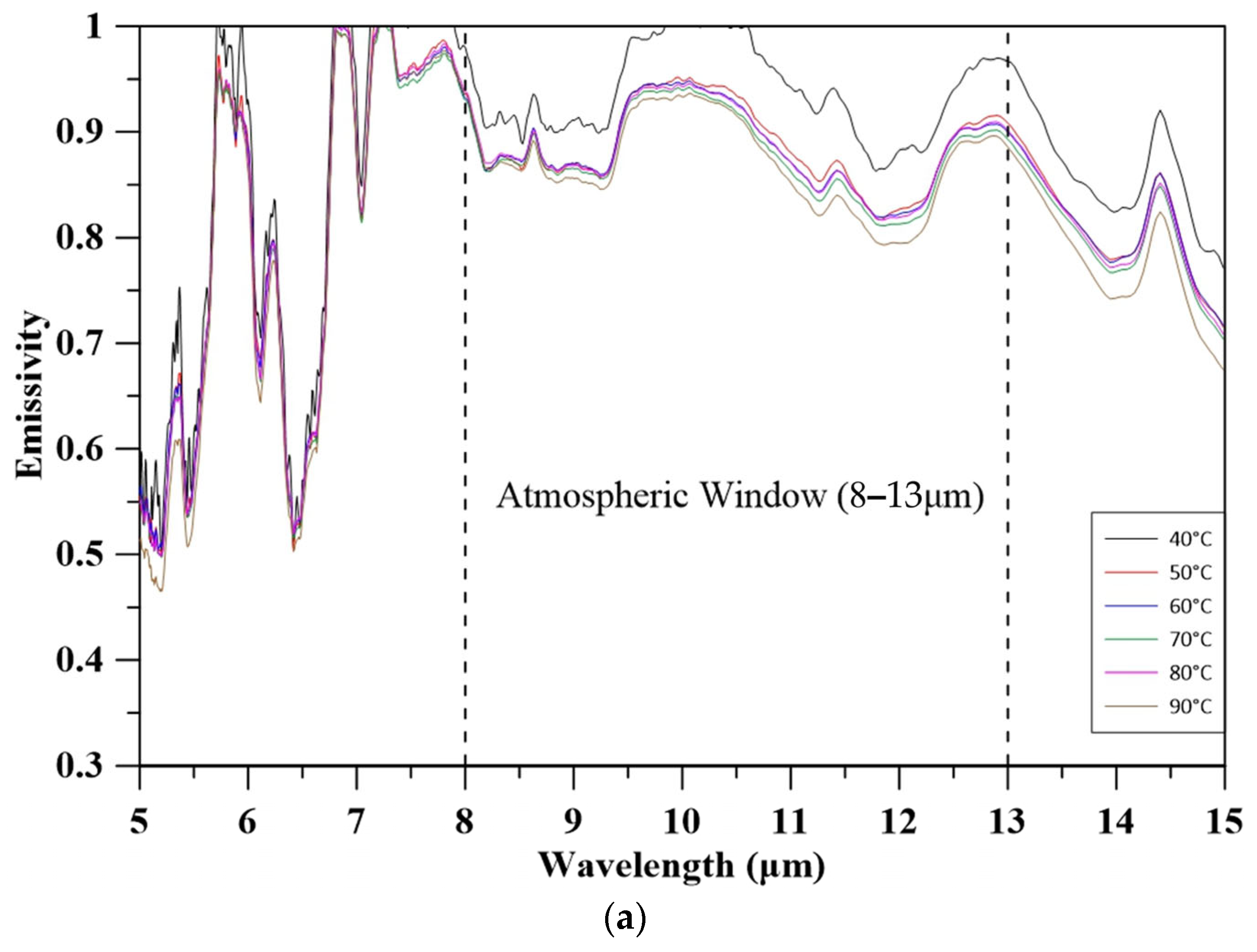

2.2.4. Emissivity

2.3. Mixture Design

3. Test Methods

3.1. Density and Porosity Test

3.2. Compressive Strength Test

3.3. Indoor Irradiation Test

3.4. Emissivity Test

3.5. Thermal Transmittance Test

4. Thermal Performance Theory

4.1. Heat Storage

4.1.1. Total Heat Storage

4.1.2. Layer-Wise Heat Storage

4.2. Specific Heat Capacity

4.3. Effective Heat-Energy Change

4.4. Radiative Heat Loss

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Density and Porosity

5.2. Compressive Strength

5.3. Indoor Irradiation Test Results

5.3.1. Heat Storage

5.3.2. Specific Heat Capacity

5.3.3. Effective Heat-Energy Change

5.4. Thermal Radiation

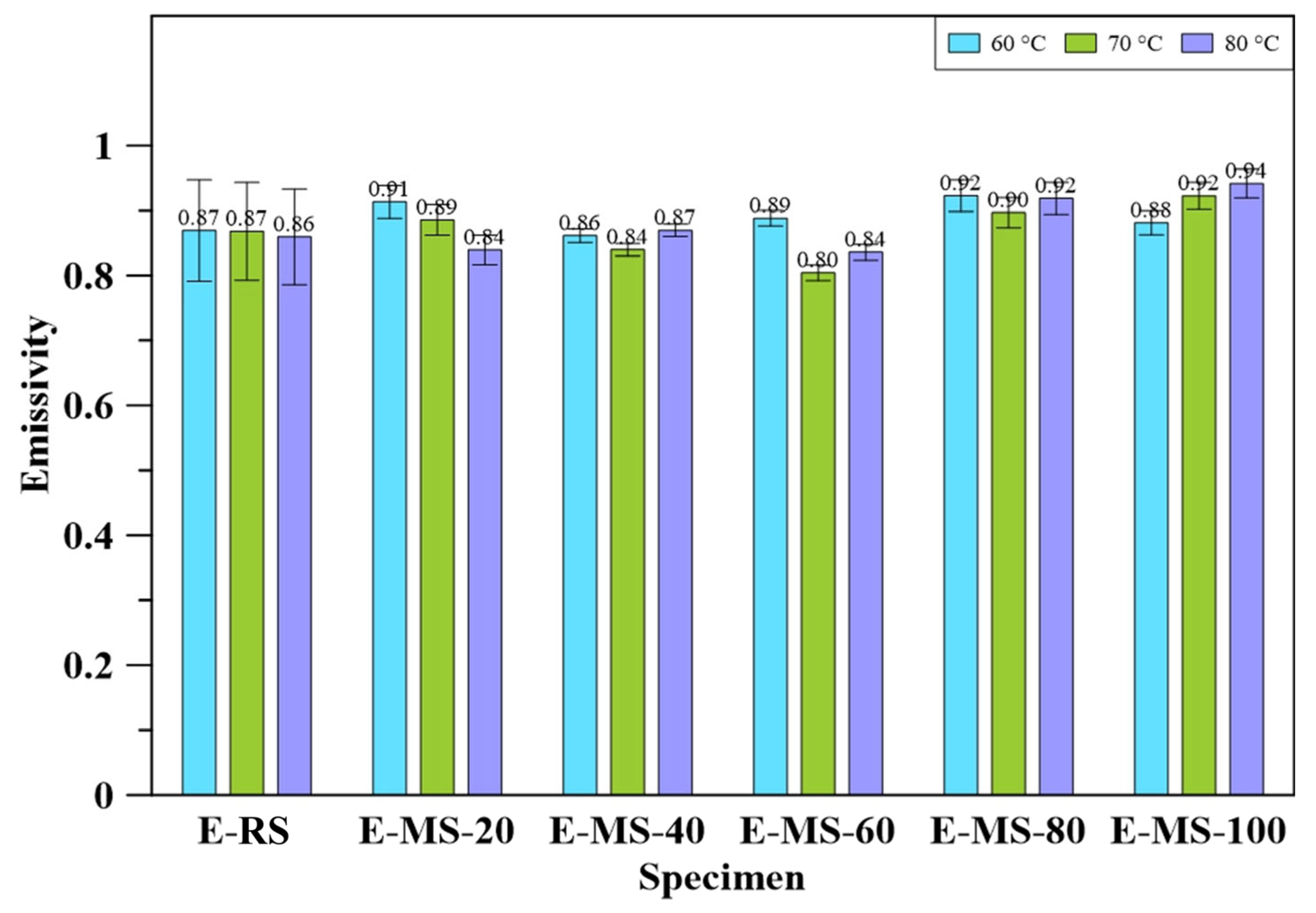

5.4.1. Emissivity

- The observed temperature-dependent emissivity is presumably attributed primarily to the mineralogical composition of MBOFS. The dominant crystalline phases, calcite (CaCO3), calcium silicate (Ca2SiO4), and wüstite (FeO), exhibit lattice and molecular vibrational bands within the mid-infrared range [63,64,65]. Although these minerals are macroscopically non-polar (i.e., they lack a permanent macroscopic dipole moment), their ionic bonds generate well-defined vibrational modes that contribute significantly to absorption. According to Kirchhoff’s law of thermal radiation, the material’s spectral emissivity equals its spectral absorptivity at thermodynamic equilibrium [66]. This relationship dictates the inverse correlation between strong absorption bands (low emissivity) and spectral features like the Christiansen Feature (high emissivity). Planck’s law further provides the blackbody spectral radiance. The combination of the material’s characteristic spectral emissivity and the blackbody spectral radiance explains the strong thermal emission features observed within the 8–13 μm atmospheric window [67].

- Surface roughness, porosity, and the potential desorption of physically adsorbed water may influence the effective emissivity in the MIR range. Although direct experimental evidence for MBOFS concrete is currently limited, previous studies on other materials have shown that surface porosity can visibly affect emissivity, suggesting that micro-structural features could contribute as a secondary factor [68].

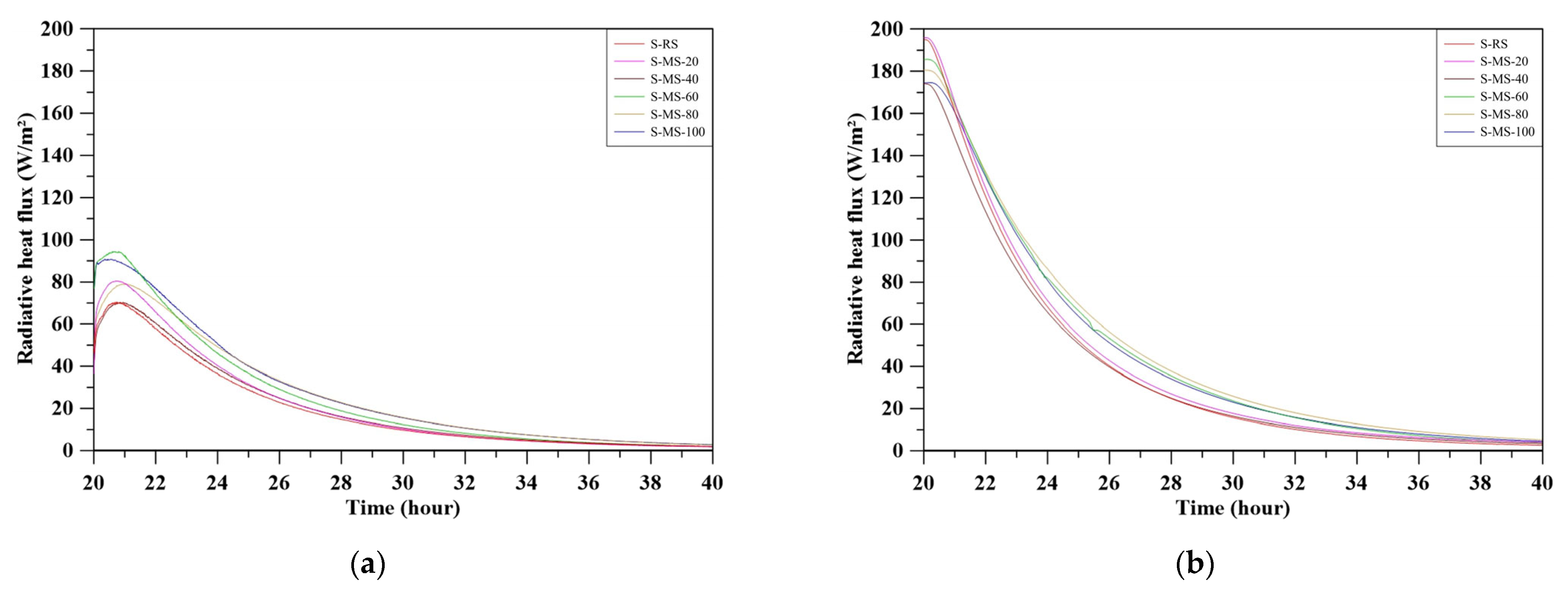

5.4.2. Radiative Heat Loss

5.5. Thermal Transmittance

6. Conclusions and Suggestions

- Optical properties of aggregates: MBOFS aggregates exhibited excellent radiative-cooling potential, with high mid-infrared emissivity (up to 95.92% in the 8–13 μm atmospheric window), low solar reflectance (25–35%), and negligible transmittance (<0.2%). These properties support enhanced thermal radiation while minimizing solar heat gain.

- Density, porosity, and mechanical strength: With increasing MBOFS content, specimen density rose from 2229 to 2611 kg/m3, while porosity increased modestly from 14.5% to 19.0%. Despite this, compressive strength improved, reaching 32.85 MPa at 100% replacement, confirming the structural viability of MBOFS concrete.

- Heat storage and specific heat capacity: High-replacement specimens (S-MS-80 and S-MS-100) exhibited the greatest total and layer-wise heat storage, as well as the highest specific heat capacities (up to 1037 J/kg·K), indicating superior thermal accumulation. In contrast, low-replacement mixes (S-MS-20 and S-MS-40) showed limited heat retention, likely due to uneven internal packing and poor thermal connectivity.

- Emissivity and radiative heat dissipation: MBOFS-modified concretes showed elevated emissivity values across all temperatures compared to the reference mixture. Specimens with 80–100% MBOFS exhibited greater radiative heat loss, particularly from the top and side surfaces, driven by both high emissivity and enhanced thermal mass.

- Cooling dynamics and comparative performance: S-MS-60 demonstrated the fastest cooling rate and most balanced thermal behavior, making it suitable for applications requiring rapid surface-temperature reduction. However, higher replacement ratios (S-MS-80 and S-MS-100) delivered superior cumulative thermal and mechanical performance, supporting their use in energy storage-oriented envelope systems.

- Thermal performance indicators: Thermal transmittance decreased with MBOFS content, from 3.644 to 3.235 W/m2·K. The higher heat storage capacity and higher emissivity (thermal radiation) suppress thermal transmittance, thus improving the thermal resistance of the building walls. These shifts suggest that MBOFS enhances the thermal resistance, improving its suitability for passive thermal regulation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. Monthly Global Climate Report for Annual 2024. January 2025. Available online: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/monthly-report/global/202413 (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Kweku, D.W.; Bismark, O.; Maxwell, A.; Desmond, K.A.; Danso, K.B.; Oti-Mensah, E.A.; Quachie, A.T.; Adormaa, B.B. Greenhouse Effect: Greenhouse Gases and Their Impact on Global Warming. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2018, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuttler, W. The Urban Climate–Basic and Applied Aspects. In Urban Ecology: An International Perspective on the Interaction between Humans and Nature; Marzluff, J.M., Shulenberger, E., Endlicher, W., Alberti, M., Bradley, G., Ryan, C., Simon, U., ZumBrunnen, C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Milesi, C.; Churkina, G. Measuring and Monitoring Urban Impacts on Climate Change from Space. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajerani, A.; Bakaric, J.; Jeffrey-Bailey, T. The Urban Heat Island Effect, Its Causes, and Mitigation, with Reference to the Thermal Properties of Asphalt Concrete. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 197, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulpiani, G. On the Linkage between Urban Heat Island and Urban Pollution Island: Three-Decade Literature Review towards a Conceptual Framework. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, A.M. Energy, Environment and Sustainable Development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2008, 12, 2265–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Cui, G. Influence of Spectral Characteristics of the Earth’s Surface Radiation on the Greenhouse Effect: Principles and Mechanisms. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 244, 117908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettler, J.N.; Quanz, S.P.; Helled, R.; Olson, S.L.; Schwieterman, E.W. Earth as an exoplanet. II. Earth’s time-variable thermal emission and its atmospheric seasonality of bioindicators. Astrophys. J. 2023, 946, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Des Marais, D.J.; Harwit, M.O.; Jucks, K.W.; Kasting, J.F.; Lin, D.N.; Lunine, J.I.; Schneider, J.; Traub, W.A.; Woolf, N.J. Remote sensing of planetary properties and biosignatures on extrasolar terrestrial planets. Astrobiology 2002, 2, 153–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, M.; Schreier, F.; García, S.G.; Kitzmann, D.; Patzer, B.; Rauer, H.; Trautmann, T. Infrared radiative transfer in atmospheres of Earth-like planets around F, G, K, and M stars-II. Thermal emission spectra influenced by clouds. Astron. Astrophys. 2013, 557, A46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlosena, L.; Ruiz-Pardo, Á.; Feng, J.; Irulegi, O.; Hernández-Minguillón, R.J.; Santamouris, M. On the Energy Potential of Daytime Radiative Cooling for Urban Heat Island Mitigation. Sol. Energy 2020, 208, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfeey, A.M.M.; Chau, H.W.; Sumaiya, M.M.F.; Wai, C.Y.; Muttil, N.; Jamei, E. Sustainable Mitigation Strategies for Urban Heat Island Effects in Urban Areas. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M.; Yun, G.Y. Recent Development and Research Priorities on Cool and Super Cool Materials to Mitigate Urban Heat Island. Renew. Energy 2020, 161, 792–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Aili, A.; Zhai, Y.; Xu, S.; Tan, G.; Yin, X.; Yang, R. Radiative Sky Cooling: Fundamental Principles, Materials, and Applications. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2019, 6, 021306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Pérez, I.; Álvarez, G.; Xamán, J.; Zavala-Guillén, I.; Arce, J.; Simá, E. Thermal Performance of Reflective Materials Applied to Exterior Building Components—A Review. Energy Build. 2014, 80, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, J.; Sailor, D.J. Role of Pavement Radiative and Thermal Properties in Reducing Excess Heat in Cities. Sol. Energy 2022, 242, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaeemehr, B.; Jandaghian, Z.; Ge, H.; Lacasse, M.; Moore, T. Increasing Solar Reflectivity of Building Envelope Materials to Mitigate Urban Heat Islands: State-of-the-Art Review. Buildings 2023, 13, 2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; Huang, C.H.; Li, Y.F.; Lee, W.H.; Cheng, T.W. Utilization of Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag in Geopolymeric Coating for Passive Radiative Cooling Application. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Qian, G.; Yu, H.; Lei, R.; Ge, J.; Dai, W.; Zhong, Y.; Huang, L. Research on thermal conduction of steel slag-modified asphalt mixtures considering aggregate properties. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauser, C.; Huenges, E. Thermal conductivity of rocks and minerals. Rock Phys. Phase Relat. A Handb. Phys. Constants 1995, 3, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Steel Association. Raw Materials. Available online: https://worldsteel.org/other-topics/raw-materials/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Li, Y.F.; Yang, P.A.; Wu, C.H.; Cheng, T.W.; Huang, C.H. A Study on Radiation Cooling Effect on Asphalt Concrete Pavement Using Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag to Replace Partial Aggregates. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Sha, A.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Li, J.; Liu, H. Thermal Conductivity Evaluation and Road Performance Test of Steel Slag Asphalt Mixture. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.H.; Lee, Y.C.; Sheu, B.L. Application and Breakthrough of BOF Slag Modification Technique. China Steel Tech. Rep. 2015, 28, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kambole, C.; Paige-Green, P.; Kupolati, W.K.; Ndambuki, J.M.; Adeboje, A.O. Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag for Road Pavements: A Review of Material Characteristics and Performance for Effective Utilisation in Southern Africa. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 148, 618–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Steel Association. Total Production of Crude Steel. January 2025. Available online: https://worldsteel.org/data/annual-production-steel-data/?ind=P1_crude_steel_total_pub/CHN/IND (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Matsuura, H.; Yang, X.; Li, G.; Yuan, Z.; Tsukihashi, F. Recycling of Ironmaking and Steelmaking Slags in Japan and China. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2022, 29, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K.; Sasaki, K. Occurrence of Steel Converter Slag and Its High Value-Added Conversion for Environmental Restoration in China: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 373, 133876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Piloneta, M.; Terrados-Cristos, M.; Álvarez-Cabal, J.V.; Vergara-González, E. Comprehensive analysis of steel slag as aggregate for road construction: Experimental testing and environmental impact assessment. Materials 2021, 14, 3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lun, Y.; Liu, S.; Luo, X. Mechanical Mechanism for Expansion and Crack of Mortars Containing Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag Sand. Mater. Res. Innov. 2015, 19, S5-865–S5-869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodor, M.; Santos, R.M.; Cristea, G.; Salman, M.; Cizer, Ö.; Iacobescu, R.I.; Chiang, Y.W.; van Balen, K.; Vlad, M.; van Gerven, T. Laboratory Investigation of Carbonated BOF Slag Used as Partial Replacement of Natural Aggregate in Cement Mortars. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 65, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.T.; Tsai, C.J.; Chen, J.; Liu, W. Feasibility and Characterization Mortar Blended with High-Amount Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag. Materials 2018, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omur, T.; Miyan, N.; Kabay, N.; Özkan, H. Utilization and Optimization of Unweathered and Weathered Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag Aggregates in Cement Based Mortar. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 64, 105634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.C.; Yang, C.C.; Tsai, L.W.; Yue, M.T. The Application and Breakthrough of BOF Slag Modification Technique in CSC. Min. Metall. 2014, 58, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Su, T.-H.; Yang, H.-J.; Lee, Y.-C.; Shau, Y.-H.; Takazawa, E.; Lin, M.-F.; Mou, J.-L.; Jiang, W.-T. Reductive Heating Experiments on BOF-Slag: Simultaneous Phosphorus Re-Distribution and Volume Stabilization for Recycling. Steel Res. Int. 2016, 87, 1511–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Hu, X.; Chou, K.C. Oxidative Modification of Industrial Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag for Recover Iron-Containing Phase: Study on Phase Transformation and Mineral Structure Evolution. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 171, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Li, G.; Li, Y.; Li, T.; Yuan, C.; Liu, Y. Thermodynamics and Kinetics on Hot State Modification of BOF Slag by Adding SiO2. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2023, 54, 1131–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motz, H.; Geiseler, J. Products of Steel Slags—An Opportunity to Save Natural Resources. Waste Manag. 2001, 21, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baalamurugan, J.; Kumar, V.G.; Padmapriya, R.; Raja, V.B. Recent Applications of Steel Slag in Construction Industry. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 2865–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zago, S.C.; Vernilli, F.; Cascudo, O. The Reuse of Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag as Concrete Aggregate to Achieve Sustainable Development: Characteristics and Limitations. Buildings 2023, 13, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Shukla, S. Utilization of Steel Slag Waste as Construction Material: A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 78, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E1621-22; Standard Guide for Elemental Analysis by Wavelength Dispersive X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.astm.org/e1621-22.html (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- ASTM E3294-23; Standard Guide for Forensic Analysis of Geological Materials by Powder X-ray Diffraction. International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.astm.org/e3294-23.html (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- ASTM C33/C33M-24a; Standard Specification for Concrete Aggregates. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.astm.org/c0033_c0033m-24a.html (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Popovics, S.; Mather, B. Aggregate Grading and the Internal Structure of Concrete. In Highway Research Record No. 441: Grading of Concrete Aggregates; Highway Research Board, National Academy of Science: Washington, DC, USA, 1973; pp. 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Wang, Z.H.; Kaloush, K.E. Environmental Impacts of Reflective Materials: Is High Albedo a “Silver Bullet” for Mitigating Urban Heat Island? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 830–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekhontsev, S.N.; Prokhorov, A.V.; Hanssen, L.M. Experimental Characterization of Blackbody Radiation Sources. In Radiometric Temperature Measurements II: Applications; Zhang, Z.M., Tsai, B.K., Machin, G., Eds.; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 43, pp. 57–129. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai, T.; Satō, T. Temperature Dependence of Vibrational Spectra in Calcite by Means of Emissivity Measurement. Phys. Rev. B 1971, 4, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I. Leveraging Phonon Polariton Modes in Polar Materials for Selective Thermal Emission and Absorption. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, USA, 2021. OCLC No. 1287936739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C642-21; Standard Test Method for Density, Absorption, and Voids in Hardened Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.astm.org/c0642-21.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- ASTM C39/C39M-24; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.astm.org/c0039_c0039m-24.html (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Li, Y.-F.; Xie, Y.-X.; Syu, J.-Y.; Huang, C.-H.; Tsai, H.-H.; Cheng, T.-W.; Chen, Y.-C.; Lee, W.-H. A Study on the Influence of the Next Generation Colored Inorganic Geopolymer Material Paint on the Insulation Measurement of Concrete Building Shell. Sustainability 2021, 14, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, Z.; Tan, J. Heat Storage Properties of the Cement Mortar Incorporated with Composite Phase Change Material. Appl. Energy 2013, 103, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9869-2:2018; Thermal Insulation—Building Elements—In-Situ Measurement of Thermal Resistance and Thermal Transmittance—Part 2: Infrared Method for Frame Structure Dwelling. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/67673.html (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- EN ISO 6946:2017; Building Components and Building Elements—Thermal Resistance and Thermal Transmittance—Calculation Methods. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/65708.html (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Awoyera, P.O.; Kırgız, M.S. Mineralogy and interfacial transition zone features of recycled aggregate concrete. In The Structural Integrity of Recycled Aggregate Concrete Produced with Fillers and Pozzolans; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2022; pp. 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Lin, H.S.; Syu, J.Y.; Lee, W.H.; Huang, C.H.; Tsai, Y.K.; Shvarzman, A. Investigating the Static and Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Incorporating Recycled Carbon Fiber and Modified Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag Aggregate. Recycling 2025, 10, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Liu, M.M.; Song, H.F.; Guan, W.; Yan, H.M. Influence of initial defects on deformation and failure of concrete under uniaxial compression. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2020, 234, 107106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Mediamartha, B.; Yu, S. Simulation of the Mesoscale Cracking Processes in Concrete Under Tensile Stress by Discrete Element Method. Materials 2025, 18, 2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Zou, R.; Jin, F. Experimental Study on Specific Heat of Concrete at High Temperatures and Its Influence on Thermal Energy Storage. Energies 2016, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.H.; Beaucour, A.L.; Ortola, S.; Noumowé, A. Experimental Study on the Thermal Properties of Lightweight Aggregate Concretes at Different Moisture Contents and Ambient Temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 151, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; Dusseault, M.; Xu, B.; Michaelian, K.H.; Poduska, K.M. Photoacoustic Detection of Weak Absorp-tion Bands in Infrared Spectra of Calcite. Appl. Spectrosc. 2021, 75, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, P.; Kirkpatrick, R.J.; Poe, B.; McMillan, P.F.; Cong, X. Structure of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H): Near-, Mid-, and Far-infrared spectroscopy. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1999, 82, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrettle, F.; Kant, C.; Lunkenheimer, P.; Mayr, F.; Deisenhofer, J.; Loidl, A. Wüstite: Electric, thermodynamic and optical properties of FeO. Eur. Phys. J. B 2012, 85, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salihoglu, H.; Xu, X. Near-field radiative heat transfer enhancement using natural hyperbolic material. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2019, 222, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Rada, J.; Tian, Y.; Han, Y.; Lai, Z.; McCabe, M.F.; Gan, Q. Radiative cooling for energy sustainability: Materials, systems, and applications. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2022, 6, 090201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineo, S.; Pappalardo, G. Rock emissivity measurement for infrared thermography engineering geological ap-plications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Content (% by Weight) |

|---|---|

| CaO | 42.91 |

| Fe2O3 | 36.00 |

| SiO2 | 10.62 |

| MnO2 | 4.10 |

| MgO | 2.41 |

| Al2O3 | 1.68 |

| P | 0.90 |

| V2O5 | 0.47 |

| TiO2 | 0.43 |

| Cr2O3 | 0.29 |

| Others | 0.19 |

| Mixture ID 2 | Volume Replacement Rates of Natural Aggregate by MBOFS (%) | Mix Proportions (Weight Fractions Relative to Cement) 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cement | Water 3 | Natural Aggregates | MBOFS Aggregates | ||||

| Sand (Quartz) | Coarse Aggregate | Sand | Coarse Aggregate | ||||

| RS | 0 | 1.00 | 0.55 | 1.00 | 2.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| MS-20 | 20 | 0.80 | 1.84 | 0.25 | 0.58 | ||

| MS-40 | 40 | 0.60 | 1.38 | 0.50 | 1.15 | ||

| MS-60 | 60 | 0.40 | 0.92 | 0.75 | 1.73 | ||

| MS-80 | 80 | 0.20 | 0.46 | 1.01 | 2.30 | ||

| MS-100 | 100 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.26 | 2.88 | ||

| Type | Description | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Test | Density and Porosity Test | D |

| Compression test | C | |

| Emissivity test | E | |

| Thermal conductivity test | T | |

| Indoor irradiation test | I | |

| Specimen material | 100% natural aggregate (reference specimen) | RS |

| MBOFS and natural aggregate replacement percentage (20–100) | MS-20 |

| Specimen | No. | Density (kg/m3) | Average Density (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-RS | 1 | 2322.8 | 2228.8 |

| 2 | 2224.8 | ||

| D-MS-20 | 1 | 2338.0 | 2337.8 |

| 2 | 2337.6 | ||

| D-MS-40 | 1 | 2418.8 | 2418.0 |

| 2 | 2417.3 | ||

| D-MS-60 | 1 | 2481.1 | 2481.9 |

| 2 | 2482.8 | ||

| D-MS-80 | 1 | 2557.6 | 2555.5 |

| 2 | 2570.3 | ||

| D-MS-100 | 1 | 2617.7 | 2611.5 |

| 2 | 2605.3 |

| Specimen | No. | Porosity (%) | Average Porosity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-RS | 1 | 13.66 | 14.51 |

| 2 | 15.35 | ||

| D-MS-20 | 1 | 13.62 | 14.59 |

| 2 | 15.56 | ||

| D-MS-40 | 1 | 16.44 | 15.38 |

| 2 | 14.32 | ||

| D-MS-60 | 1 | 17.34 | 16.29 |

| 2 | 15.25 | ||

| D-MS-80 | 1 | 15.90 | 17.04 |

| 2 | 18.17 | ||

| D-MS-100 | 1 | 18.90 | 19.03 |

| 2 | 19.15 |

| Specimen | S-RS | S-MS-20 | S-MS-40 | S-MS-60 | S-MS-80 | S-MS-100 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat storage (J) | 74,777 | 67,162 | 71,263 | 76,209 | 82,252 | 87,560 | |

| 101,779 | 96,665 | 98,145 | 110,351 | 124,984 | 121,760 | ||

| 123,589 | 114,679 | 118,586 | 130,592 | 145,065 | 146,524 | ||

| 300,145 | 278,506 | 287,995 | 317,151 | 352,302 | 355,845 | ||

| Specimen | S-RS | S-MS-20 | S-MS-40 | S-MS-60 | S-MS-80 | S-MS-100 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Layer heat storage (J) | 0–1 cm | 37,855 | 34,369 | 36,157 | 39,046 | 42,555 | 44,508 |

| 1–3 cm | 81,320 | 74,789 | 77,882 | 85,085 | 93,792 | 96,083 | |

| 3–5 cm | 86,121 | 79,967 | 82,647 | 91,070 | 101,223 | 102,131 | |

| 5–7 cm | 94,848 | 89,380 | 91,308 | 101,950 | 114,731 | 113,123 | |

| Specimen | Layer-Specific Heat Capacity (J/kg·K) | Thickness-Weighted Specific Heat Capacity (J/kg·K) | Direct-Estimated Specific Heat Capacity (J/kg·K) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 cm | 1–3 cm | 3–5 cm | 5–7 cm | |||

| S-RS | 786.64 | 873.26 | 952.05 | 1107.64 | 950.36 | 945.83 |

| S-MS-20 | 717.98 | 810.07 | 897.86 | 1068.12 | 895.73 | 889.97 |

| S-MS-40 | 724.44 | 805.80 | 880.29 | 1041.68 | 882.85 | 877.76 |

| S-MS-60 | 751.65 | 855.71 | 975.54 | 1190.14 | 970.63 | 948.14 |

| S-MS-80 | 797.25 | 920.27 | 1034.67 | 1278.04 | 1037.60 | 1027.42 |

| S-MS-100 | 752.23 | 856.05 | 964.00 | 1178.77 | 964.27 | 953.20 |

| Specimen | Heat Loss (J) | Difference with (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-RS | 55,735.11 | 112,511.92 | 117,772.92 | 286,019.95 | −4.7 |

| S-MS-20 | 61,461.31 | 119,125.91 | 126,411.06 | 306,998.28 | 10.2 |

| S-MS-40 | 58,680.89 | 108,409.38 | 116,942.19 | 284,002.47 | −1.4 |

| S-MS-60 | 71,942.52 | 132,191.34 | 142,893.70 | 347,027.55 | 9.4 |

| S-MS-80 | 74,179.23 | 137,605.58 | 148,249.37 | 360,037.18 | 2.2 |

| S-MS-100 | 78,423.49 | 129,608.82 | 145,622.62 | 353,654.93 | −0.6 |

| Specimen | Material Resistance (m2·K/W) | Thermal Transmittance (W/m2·K) |

|---|---|---|

| T-RS | 0.034 | 3.644 |

| T-MS-20 | 0.039 | 3.582 |

| T-MS-40 | 0.049 | 3.485 |

| T-MS-60 | 0.053 | 3.414 |

| T-MS-80 | 0.062 | 3.306 |

| T-MS-100 | 0.069 | 3.235 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Syu, J.-Y.; Li, Y.-W.; Li, Y.-F.; Huang, C.-H.; Chen, S.-H.; Lee, W.-H. A Study on Thermal Performance for Building Shell of Modified Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag Replacing Partial Concrete Aggregate. Buildings 2026, 16, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010108

Syu J-Y, Li Y-W, Li Y-F, Huang C-H, Chen S-H, Lee W-H. A Study on Thermal Performance for Building Shell of Modified Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag Replacing Partial Concrete Aggregate. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010108

Chicago/Turabian StyleSyu, Jin-Yuan, Yu-Wei Li, Yeou-Fong Li, Chih-Hong Huang, Shih-Han Chen, and Wei-Hao Lee. 2026. "A Study on Thermal Performance for Building Shell of Modified Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag Replacing Partial Concrete Aggregate" Buildings 16, no. 1: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010108

APA StyleSyu, J.-Y., Li, Y.-W., Li, Y.-F., Huang, C.-H., Chen, S.-H., & Lee, W.-H. (2026). A Study on Thermal Performance for Building Shell of Modified Basic Oxygen Furnace Slag Replacing Partial Concrete Aggregate. Buildings, 16(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010108