Durability Assessment of Marine Steel-Reinforced Concrete Using Machine Vision: A Case Study on Corrosion Damage and Geometric Deformation in Shield Tunnels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodologies

2.1. 3D Point Cloud Preprocessing for Shield Tunnels

2.1.1. Point Cloud Registration and Downsampling

2.1.2. Calculation of Tunnel Centerline and Mileage

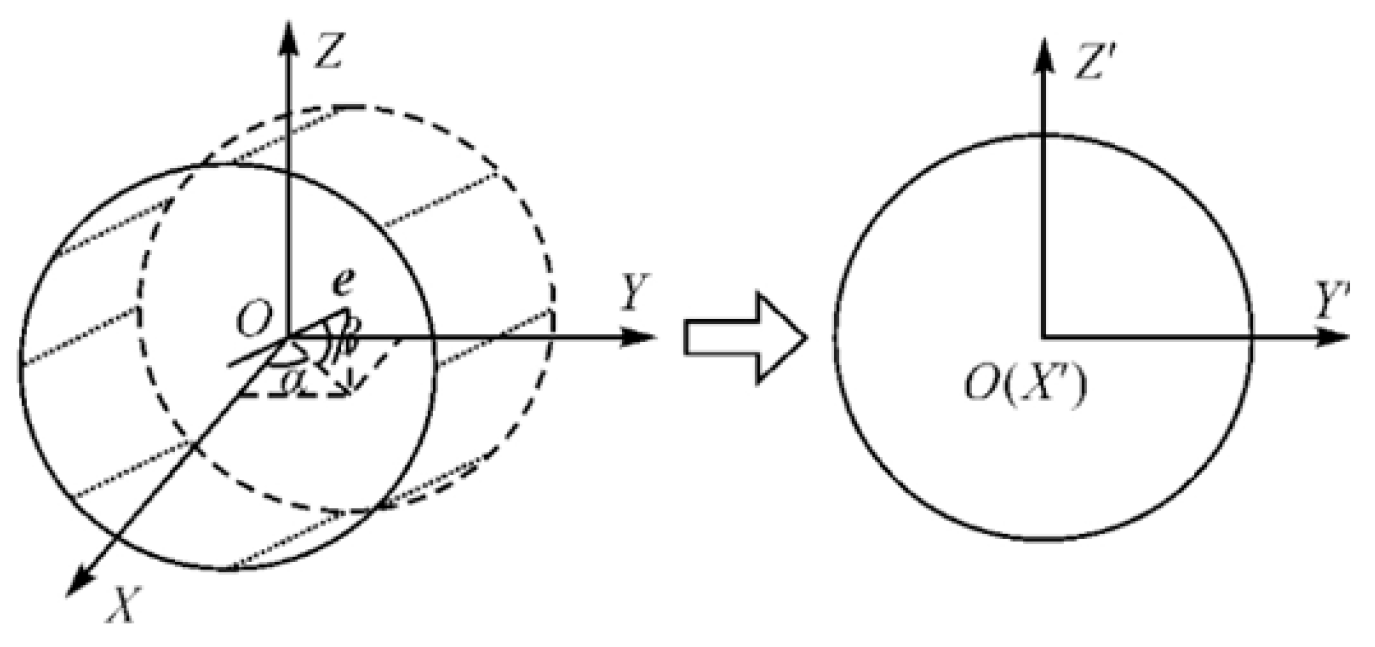

2.1.3. Tunnel Point Cloud Rotation

2.1.4. Tunnel Cross-Section Extraction and Point Cloud Noise Filtering

2.2. Corrosion Damage Identification for Shield Tunnels

2.2.1. Pre-Trained Network

2.2.2. Bounding Box Prediction

2.2.3. Non-Maximum Suppression

3. Experimental Procedures

3.1. Geometric Deformation in Reinforced-Concrete Tunnels

3.2. Corrosion Damage Detection in Reinforced-Concrete Tunnels

3.2.1. Dataset Creation and Training Parameter Configuration

3.2.2. Model Evaluation Index Analysis

4. Risk Scoring-Based Durability Assessment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bao, J.; Wei, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhuang, Z.; Zhao, T. Experimental and Theoretical Investigation of Chloride Ingress into Concrete Exposed to Real Marine Environment. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 130, 104511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Wu, L.; Guan, L.; Liu, M.; Ju, X.; Xiang, Z.; Jiang, X.; Li, Y.; Long, J. Durability Life Evaluation of Marine Infrastructures Built by Using Carbonated Recycled Coarse Aggregate Concrete Due to the Chloride Corrosive Environment. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1357186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjölander, A.; Belloni, V.; Ansell, A.; Nordström, E.; Sjölander, A.; Belloni, V.; Ansell, A.; Nordström, E. Towards Automated Inspections of Tunnels: A Review of Optical Inspections and Autonomous Assessment of Concrete Tunnel Linings. Sensors 2023, 23, 3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincon, L.F.; Moscoso, Y.M.; Hamami, A.E.A.; Matos, J.C.; Bastidas-Arteaga, E.; Rincon, L.F.; Moscoso, Y.M.; Hamami, A.E.A.; Matos, J.C.; Bastidas-Arteaga, E. Degradation Models and Maintenance Strategies for Reinforced Concrete Structures in Coastal Environments under Climate Change: A Review. Buildings 2024, 14, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bao, T.; Huang, X.; Wang, R.; Shu, X.; Xu, B.; Tu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, K. An Integrated Underwater Structural Multi-Defects Automatic Identification and Quantification Framework for Hydraulic Tunnel via Machine Vision and Deep Learning. Struct. Health Monit. 2023, 22, 2360–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, C.; Kun, Z.; Wei, W.; Kun, H.U.; Yang, X.U. Intelligent Identification of Tunnel Water Leakage Based on TR-Unet. J. Basic Sci. Eng. 2025, 33, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Liu, S.; Zhou, M.; Shao, H.; Li, Q.; Thansirichaisree, P. Automated 3D Defect Inspection in Shield Tunnel Linings through Integration of Image and Point Cloud Data. AI Civ. Eng. 2025, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Ishida, T.; Nagata, Y.; Kawamura, H.; Tokuno, T.; Suzuki, K.; Yamaguchi, Y. Automatic Detection of Delamination on Tunnel Lining Surfaces from Laser 3D Point Cloud Data by 3D Features and a Support Vector Machine. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2024, 14, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Yang, J.; Li, Q.; He, J.; Chen, B. 3D Laser Scanning Acquisition and Modeling of Tunnel Engineering Point Cloud Data. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2425, 012064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, M.; Wang, L.; You, Z.; Camara, M.; Wang, L.; You, Z. Three-Dimensional Point Cloud Displacement Analysis for Tunnel Deformation Detection Using Mobile Laser Scanning. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, M.; Wang, L.; You, Z.; Camara, M.; Wang, L.; You, Z. Tunnel Cross-Section Deformation Monitoring Based on Mobile Laser Scanning Point Cloud. Sensors 2024, 24, 7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Tao, Y.; Ji, B.; Gan, Q.; Guo, T.; Tan, D.; Tao, Y.; Ji, B.; Gan, Q.; Guo, T. Full-Section Deformation Monitoring of High-Altitude Fault Tunnels Based on Three-Dimensional Laser Scanning Technology. Sensors 2024, 24, 2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.M.; Nasrabadi, N.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.E.; Eem, S.-H.; Jeon, H. Concrete Crack Detection and Quantification Using Deep Learning and Structured Light. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 252, 119096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning Representations by Back-Propagating Errors. Nature 1986, 323, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeum, C.M.; Dyke, S.J.; Ramirez, J. Visual Data Classification in Post-Event Building Reconnaissance. Eng. Struct. 2018, 155, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Chetverikov, D.; Svirko, D.; Stepanov, D.; Krsek, P. The Trimmed Iterative Closest Point Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2002 International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Quebec City, QC, Canada, 11–15 August 2002; Volume 3, pp. 545–548. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Luo, J. A Framework of Point Cloud Simplification Based on Voxel Grid and Its Applications. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 6349–6357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasifard, M.R.; Ghahremani, B.; Naderi, H. A Survey on Nearest Neighbor Search Methods. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2014, 95, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batu, T.; Lemu, H.G. Comparative Study of the Effect of Chord Length Computation Methods in Design of Wind Turbine Blade. In Proceedings of the Advanced Manufacturing and Automation IX; Wang, Y., Martinsen, K., Yu, T., Wang, K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 106–115. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, L.; Abdullah, M.I. YOLO Series Algorithms in Object Detection of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: A Survey. Serv. Oriented Comput. Appl. 2024, 18, 269–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.H.; Kim, S.Y. Real-Time Object Detection and Segmentation Technology: An Analysis of the YOLO Algorithm. JMST Adv. 2023, 5, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwan, T.; Anirudh, G.; Tembhurne, J.V. Object Detection Using YOLO: Challenges, Architectural Successors, Datasets and Applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 9243–9275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M. YOLO-v1 to YOLO-v8, the Rise of YOLO and Its Complementary Nature toward Digital Manufacturing and Industrial Defect Detection. Machines 2023, 11, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosang, J.; Benenson, R.; Schiele, B. Learning Non-Maximum Suppression. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 6469–6477. [Google Scholar]

- Safie, S.I.; Kamal, N.S.A.; Yusof, E.M.M.; Tohid, M.Z.-W.M.; Jaafar, N.H. Comparison of SqueezeNet and DarkNet-53 Based YOLO-V3 Performance for Beehive Intelligent Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 13th Symposium on Computer Applications & Industrial Electronics (ISCAIE), Penang, Malaysia, 20–21 May 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 62–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, T.-Y.; Chang, Y.-C.; Chou, H.-H.; Chiu, C.-T. Filter-Based Deep-Compression with Global Average Pooling for Convolutional Networks. J. Syst. Archit. 2019, 95, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Li, X.; Feng, Y.; Han, S. Multiple Attentional Path Aggregation Network for Marine Object Detection. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 2434–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Segment No. | Misalignment/mm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range of Misalignment | Average Value | Measured Value | Error | |

| 1–2 | 0.2~0.8 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 |

| 2–3 | −3.5~1.7 | −0.9 | 1 | 0.1 |

| 3–4 | 0.4~2.0 | 1.2 | 2 | 0.8 |

| Section No. | Ellipticity | Section No. | Ellipticity | Section No. | Ellipticity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 0.0084 | S7 | 0.0087 | S13 | 0.0083 |

| S2 | 0.0107 | S8 | 0.0104 | S14 | 0.0062 |

| S3 | 0.0082 | S9 | 0.0098 | S15 | 0.0108 |

| S4 | 0.0090 | S10 | 0.0112 | S16 | 0.0067 |

| S5 | 0.0082 | S11 | 0.0097 | S17 | 0.0074 |

| S6 | 0.0103 | S12 | 0.0099 | S18 | 0.0071 |

| Augmentation Method | Description | Parameter Range | Application Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Translation | Random horizontal and vertical shifting | ±10% of image width/height | 0.3 |

| Gaussian noise | Addition of Gaussian noise to simulate sensor noise | Mean = 0, Variance = 0.01 | 0.2 |

| Mirror flipping | Horizontal and vertical flipping | Horizontal/Vertical | 0.5 |

| Rotation | Random angular rotation | −15° to +15° | 0.3 |

| Defect Type | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) | mAP@50 (%) | mAP@50–95 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water leakage | 95.6 | 100.0 | 97.8 | 99.0 | 91.2 |

| Crack | 88.5 | 86.7 | 87.6 | 88.2 | 72.6 |

| Concrete spalling | 93.2 | 92.4 | 92.8 | 95.0 | 85.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Qi, Y.; Wang, X.; Ding, Z.; Luo, Y. Durability Assessment of Marine Steel-Reinforced Concrete Using Machine Vision: A Case Study on Corrosion Damage and Geometric Deformation in Shield Tunnels. Buildings 2026, 16, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010107

Qi Y, Wang X, Ding Z, Luo Y. Durability Assessment of Marine Steel-Reinforced Concrete Using Machine Vision: A Case Study on Corrosion Damage and Geometric Deformation in Shield Tunnels. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010107

Chicago/Turabian StyleQi, Yanzhi, Xipeng Wang, Zhi Ding, and Yaozhi Luo. 2026. "Durability Assessment of Marine Steel-Reinforced Concrete Using Machine Vision: A Case Study on Corrosion Damage and Geometric Deformation in Shield Tunnels" Buildings 16, no. 1: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010107

APA StyleQi, Y., Wang, X., Ding, Z., & Luo, Y. (2026). Durability Assessment of Marine Steel-Reinforced Concrete Using Machine Vision: A Case Study on Corrosion Damage and Geometric Deformation in Shield Tunnels. Buildings, 16(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010107