Abstract

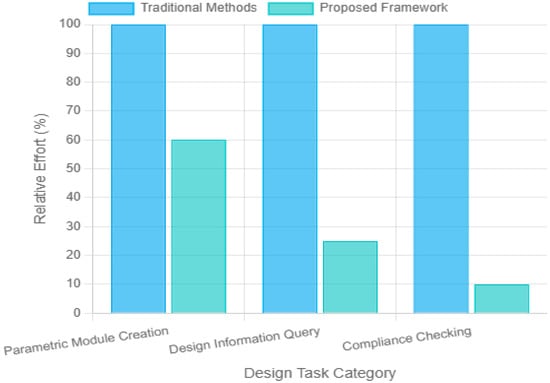

Background: Steel box girders are widely employed in bridge engineering due to their excellent mechanical properties and construction convenience, yet their modular design still encounters bottlenecks such as knowledge reuse difficulties and information silos. This study proposes a BIM-driven framework based on knowledge graphs and data fusion. By constructing a professional knowledge graph comprising 85 core entity types and 150 semantic relationships (integrated with over 15,000 knowledge units), systematic management of design knowledge is achieved. The developed BIM reverse modeling technology improves parametric modeling efficiency by 30–40%, while the data fusion mechanism supports over 90% accuracy in design conflict detection. The intelligent decision-making system built upon this framework meets 75% of business scenario requirements while effectively assisting critical decisions such as module selection. Results demonstrate that this framework significantly enhances design collaboration efficiency and intelligence through knowledge structuring and deep data integration. Although some achievements were validated via simulation due to limited field measurement data, the approach demonstrates strong engineering applicability and provides novel technical pathways and methodological support for advancing digital transformation in bridge engineering.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Development Trends of Modular Steel Box Girder Design

Steel box girder structures have become one of the preferred structural forms for modern long-span bridges, urban viaducts, and special bridges, owing to their advantages of high load-bearing capacity, excellent torsional resistance, superior spanning capability, and ease of construction quality control. They play an increasingly vital role in global infrastructure development. With advancements in engineering technology and growing demands for construction efficiency, cost control, and sustainability, the application of modular design (Modular Design) in the steel box girder field has gained significant attention. Modular design decomposes complex steel box girder structures into several standardized and precisely prefabricated modular units, which can be manufactured in factories and subsequently assembled rapidly and efficiently on-site (Figure 1). This approach significantly mitigates the limitations of on-site operations while improving fabrication accuracy and overall project quality [1]. This design and construction approach not only effectively reduces bridge construction timelines and minimizes environmental and traffic disruptions caused by on-site work but also lowers overall costs through large-scale production while facilitating future maintenance, upgrades, and even the dismantling and reuse of bridge structures.

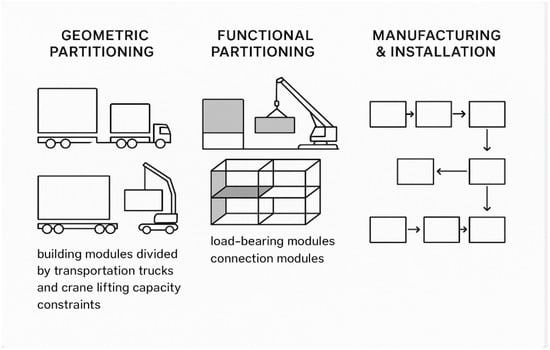

Figure 1.

Steel box girder.

However, the widespread adoption and further development of modular design for steel box girders still face numerous challenges. First, the division of modules requires comprehensive consideration of multiple factors, including geometric configuration, structural functionality, manufacturing processes, transportation conditions, and erection sequences. This complexity far surpasses that of conventional design approaches [2]. Secondly, modular design generates massive amounts of design data, manufacturing information, and assembly parameters. Effectively managing such multi-source heterogeneous data to ensure accurate transfer and consistency across different project phases and stakeholders presents a significant challenge [3]. Moreover, modular design heavily relies on precise interdisciplinary coordination among structural design, manufacturing process planning, and construction organization design. Traditional design workflows and communication methods struggle to meet the demands of such intensive collaboration. Finally, while the accumulation, transmission, and reuse of design experience are particularly crucial in modular design, these valuable insights currently remain fragmented across individuals or projects. The lack of systematic organization and intelligent application methods frequently leads to redundant design work and potential errors throughout the development process [4].

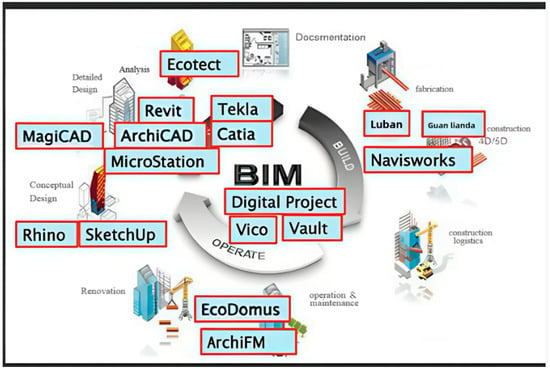

1.2. The Value of BIM, Knowledge Graphs, and Data Fusion Technologies in Engineering

Building Information Modeling (BIM) technology, as a core driver of digital transformation in the construction industry, has demonstrated immense potential throughout the entire building life cycle [5]. By establishing three-dimensional parametric models, BIM integrates geometric, physical, functional, and performance information of buildings. This provides all stakeholders with a collaborative platform for information sharing, thereby improving design quality, reducing engineering changes, optimizing construction plans, and enhancing operational efficiency [6]. However, BIM primarily focuses on the explicit representation of geometric and attribute information, with limited capabilities in processing deep domain knowledge embedded in design standards, construction specifications, and expert experience, as well as complex semantic relationships across different data sources.

Knowledge Graphs (KG), as a technology that uses graph structures to model knowledge and relationships, have achieved remarkable progress in the field of artificial intelligence in recent years [7]. KGs can transform fragmented, unstructured, or semi-structured domain knowledge into machine-understandable structured data, describing concepts and their interconnections through entities, relationships, and attributes. They also support sophisticated knowledge queries, semantic reasoning, and intelligent decision-making. In engineering, KGs are recognized as a promising solution to challenges such as chaotic knowledge management and difficulties in knowledge inheritance, demonstrating promising applications in smart Q&A systems, compliance checking, risk prediction, and other areas [8].

Data Fusion technology refers to the process of integrating information from multiple sensors or diverse sources to achieve more accurate, complete, and reliable inferences or estimates than those obtained from single-source data. In complex engineering projects, data typically originates from various design software, monitoring devices, and management systems, exhibiting multi-source, heterogeneous, and multi-modal characteristics. Through preprocessing, alignment, association, and integration of such data, data fusion technology can effectively eliminate information silos, reduce data redundancy and conflicts, and enhance the comprehensive value of data, thereby providing robust support for holistic analysis and decision-making [9].

Currently, the applications of BIM, knowledge graphs, and data fusion technologies in the construction engineering field, particularly in bridge engineering, remain in the exploratory stage. While BIM technology has been extensively applied in bridge design and construction visualization, its integration with deep domain knowledge remains insufficient. Existing research on knowledge graphs has focused on areas such as construction safety and code interpretation, yet studies on domain-specific knowledge graph construction for particular complex structures (e.g., steel box girder modular design) and their deep integration with BIM remain scarce [10]. Although data fusion technology has been employed in multi-sensor monitoring data processing, significant challenges persist regarding semantic-level fusion of heterogeneous data throughout the entire design and construction process (including drawings, BIM models, construction records, and regulatory knowledge).

1.3. Research Motivation and Core Scientific Issues

Modular steel box girder design represents an advanced construction methodology that demands intelligent technological solutions to improve its efficiency and quality. Current practices encounter significant hurdles, including challenges in effectively managing and reusing dispersed design specifications, standard drawings, construction techniques, and historical case data, which often results in inefficiencies and overlooked risks. Additionally, while BIM models contain extensive geometric and attribute data, their limited integration with external knowledge bases restricts automated compliance verification and knowledge-driven optimization. Furthermore, the disconnect between design decisions and construction feasibility, coupled with insufficient feedback from construction experiences to the design process, inhibits the development of a closed-loop knowledge system.

This study seeks to tackle these issues by investigating a crucial scientific question: how to develop an intelligent modular steel box girder design framework that integrates BIM-driven workflows, domain knowledge through knowledge graphs, and multi-phase design-construction data fusion. Addressing this requires overcoming critical technical obstacles, such as constructing a domain-specific ontology for modular steel box girders that ensures both accuracy and extensibility [11], establishing semantic mappings between BIM models and knowledge graphs for effective information interaction, and devising efficient strategies for fusing heterogeneous design-construction data while resolving inconsistencies and conflicts across diverse data sources [12].

A key aspect of this framework involves leveraging integrated BIM and knowledge graph infrastructures to deliver intelligent services for designers and construction teams. These services include query support, recommendations, risk warnings, and decision assistance, ultimately aiming to bridge the gaps in knowledge reuse, BIM application depth, and design-construction interoperability. By focusing on these areas, the proposed methodology strives to enhance modular steel box girder design through computational intelligence while ensuring practicality in real-world engineering scenarios.

1.4. Overview of Main Contributions and Innovations

To address these scientific and technical challenges, this study develops an integrated BIM-driven framework for modular steel box girder design, emphasizing the synergistic integration of knowledge graphs and data fusion technologies. The research establishes a specialized knowledge graph through domain ontology construction and multi-source knowledge extraction from textual documents and drawings. Given the frequent scarcity of engineering data, the work investigates BIM reverse modeling techniques with parametric module representations to support analytical applications [13]. Additionally, a data fusion mechanism bridges design and construction phases by enabling semantic alignment between BIM models and domain knowledge, incorporating association methods and conflict detection logic. A prototype knowledge service system was implemented to validate intelligent query and decision-support capabilities, demonstrating practical viability.

The key innovations include the deep integration of knowledge graphs and data fusion with BIM, specifically tailored to modular steel box girder design complexities. A dedicated ontology model supports knowledge structuring across modularization, connections, fabrication, and installation [14]. The proposed data fusion model facilitates bidirectional information flow, allowing construction insights and regulatory constraints to dynamically influence design. The resulting intelligent knowledge service system provides decision support for design selection, compliance verification, and construction scheme comparisons, leveraging unified knowledge and multi-phase data integration.

1.5. Thesis Structure

The remaining sections of this paper are organized as follows: Section 2 provides a detailed exposition of the BIM-driven modular steel box girder design framework and its core technologies. Section 3 validates the feasibility of the proposed framework and methods through an actual engineering case study (despite limited data availability) while also demonstrating a prototype implementation of the knowledge service system. Section 4 presents an analysis of the results obtained from the case study. Section 5 engages in an in-depth discussion of the research findings, theoretical contributions, practical value, limitations, and future work. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Research Progress

2.1. Research Progress in Modular Steel Box Girder Design

Modular steel box girder design represents an important development direction in modern bridge engineering, aiming to improve project efficiency and quality through standardization, prefabrication, and efficient assembly. Recent studies have primarily focused on the following aspects:

Modular Partitioning Principles and Methods: Researchers have explored rational module divisions from various perspectives. Geometric partitioning serves as the most fundamental method, considering transportation constraints and lifting capacity (Figure 2). Functional partitioning emphasizes the role of modules within the structural system, such as load-bearing modules or connection modules. Manufacturing and installation processes directly influence module division (Figure 2). For instance, Research and Application of Intelligent Manufacturing Technology for Steel Box Girders in Steel Bridge Construction highlights that intelligent manufacturing facilitates “industrialization and standardization” in steel bridge construction, in turn requiring module designs that are more conducive to automated production. Some studies have adopted multi-objective optimization algorithms to comprehensively evaluate factors such as cost, schedule, and structural performance when determining module partitioning.

Figure 2.

Key Considerations in the Modular Division of Steel Box Girders.

Modular Interface Design and Connection Technologies: Connections between modules represent a key challenge in modular design. Research has concentrated on high-strength bolted connections, welded joints, and novel fast connectors. For example, “Ding Yang et al.’s” [15] Research Progress on Connection Joints in Modular Steel Structures systematically examines joint configurations between steel modules, identifying fully bolted connections as a critical factor in improving assembly efficiency. Precision, durability, and their impact on overall structural performance serve as essential criteria for evaluating connection technologies.

Structural Performance Analysis and Optimization of Modular Steel Box Girders: Modularization introduces numerous interfaces, and their mechanical behavior significantly affects the overall stiffness, strength, stability, and fatigue performance of steel box girders [16]. Researchers employ methods such as finite element analysis (FEA) and experimental testing to assess structural responses under various partitioning schemes and connection methods. For example, while Steel Construction (Chinese and English) Journal discusses “Long-term Degradation Mechanisms of Stability and Bearing Capacity in U-stiffened Plates for Steel Box Girders in Cross-sea Bridges,” though not directly addressing modularization, its analytical approach offers insights for durability assessments in modular steel box girders. Structural optimization seeks to achieve an optimal balance between modular solutions and structural performance.

Existing Modular Design Processes, Tools, and Limitations: Currently, modular steel box girder design primarily relies on conventional CAD software (2020) and general FEA tools(2020), lacking dedicated integrated design platforms tailored to modular characteristics [17]. Although BIM technology has been introduced—such as the flattened steel box girder expert system developed by the Guangdong Transportation Planning and Design Institute Group Co., Ltd., which employs parametric and modular techniques to automate 3D modeling and 2D drafting—most such systems focus on geometric modeling and drawing generation, with shortcomings in deep domain knowledge integration, intelligent multi-solution comparison, and linkage with construction-phase information. Existing processes exhibit inefficiencies in knowledge and experience reuse, necessitating advancements in design intelligence.

In summary, while significant progress has been made in modular steel box girder research, challenges persist in intelligent decision-making for module partitioning, highly efficient and reliable connection joints, and the development of integrated and intelligent design tools and platforms. These aspects remain key areas for future research and practical application.

2.2. Knowledge Graph Construction Technology and Its Applications in the Construction Industry

As a semantic network, knowledge graphs (KGs) describe concepts, entities, and their interrelationships in the objective world using subject-predicate-object (SPO) triplets. The construction process typically involves key technical steps such as ontology construction, knowledge extraction, knowledge fusion, and knowledge storage and inference.

Knowledge graphs were initially proposed by Google and applied to its search engine, significantly improving search accuracy and user experience [18]. Subsequently, they have been widely adopted in intelligent Q&A, personalized recommendations, financial risk control, medical diagnosis, and other fields, demonstrating their powerful capabilities in knowledge organization, management, and intelligent applications.

As a knowledge-intensive sector, the construction industry has accumulated vast amounts of valuable knowledge, including design codes, construction standards, engineering case studies, and expert experience. Knowledge graph technology provides a novel approach for the structured, systematic management, and intelligent application of such knowledge.

- Engineering Safety Management: An intelligent intelligent support approach for engineering safety management using knowledge graphs. By constructing safety knowledge graphs, intelligent identification of construction-site hazards and risk warnings can be achieved.

- Regulatory Compliance Checking: Transforming architectural design codes into rules within KGs enables the development of automated compliance-checking tools, enhancing review efficiency and accuracy.

- Fault Diagnosis and Maintenance: In infrastructure maintenance, KGs can integrate equipment information, historical fault data, and repair records to assist in fault diagnosis and predictive maintenance.

- Integration with BIM: Some studies have begun exploring the linkage of BIM model data—rich in geometric and semantic information—with KGs to enhance BIM’s knowledge depth and enable more intelligent analysis and applications [19]. For example, Automated Code Compliance Checking Research Based on BIM and Knowledge Graph (published in Scientific Reports, 2023) proposed a BIM and KG-based automated compliance-checking system.

Despite preliminary achievements, research and application of construction KGs still face challenges:

- Incomplete Domain Knowledge Coverage: The construction knowledge system is vast, yet specialized KGs for specific subfields (e.g., modular steel box girder design) remain underdeveloped.

- Difficulty in Ontology Construction: The lack of a unified, widely accepted top-level ontology for the construction industry necessitates extensive manual effort and expert input, making the process time-consuming and labor-intensive.

- Challenges in Knowledge Acquisition and Updates: A significant portion of engineering knowledge exists in unstructured forms (e.g., text, drawings), necessitating improved automation and accuracy in knowledge extraction. Moreover, KG dynamic updating and evolution mechanisms remain immature.

- Limited Application Scenarios: Current applications are mostly confined to specific project phases, lacking lifecycle-wide implementations that deeply integrate with business workflows.

- Persistent Data Silos: KGs generated across different systems and project stages may remain isolated, hindering knowledge sharing and interoperability.

Therefore, constructing a specialized KG for modular steel box girder design—one that covers the entire process (design, manufacturing, and construction) and deeply integrates with core technologies such as BIM [20]—holds significant research value and addresses urgent practical needs.

2.3. Current State of BIM Reverse Modeling and Data Fusion Technologies

2.3.1. BIM Reverse Modeling

BIM reverse modeling refers to the process of creating 3D BIM models from existing 2D drawings, point cloud data, or other forms of architectural information. This technology holds significant value in areas such as retrofitting existing buildings, as-built model delivery, and digital twin construction.

2D Drawing to 3D BIM Model Conversion: This is a common approach in BIM reverse modeling. Traditionally, the process relied on manual operations, where 3D models were redrawn in BIM software (2020) by referencing 2D drawings—a method that was inefficient and prone to errors. In recent years, semi-automated and automated conversion techniques have emerged, leveraging image recognition, pattern matching, and rule-based reasoning to extract geometric elements (e.g., walls, columns, beams, slabs) and topological relationships from CAD drawings, thereby automating or assisting in the generation of BIM components [21]. For example, A Method for Constructing Spatial Triple-Curved Steel Box Girder Models Based on BIM Technology describes an approach that generates spatial curves from 2D drawing data before constructing the solid framework of a steel box girder, showcasing the transition from 2D to 3D (Table 1). However, fully automated conversion for complex structures and non-standard components remains challenging, often requiring manual intervention and verification.

Table 1.

A comparison of the two primary methodologies for BIM reverse modeling.

BIM Model Reconstruction from Point Cloud Data: With the widespread adoption of 3D laser scanning, using point cloud data for BIM reverse modeling has become a research hotspot. This method involves high-density scans of buildings or components, followed by point cloud segmentation, feature extraction, and geometric fitting algorithms to identify and reconstruct BIM elements. While this approach accurately reflects the as-built geometric state of structures, it faces challenges such as large data volumes, complex processing, and the absence of semantic information (requiring post-processing supplementation). In bridge engineering, point cloud data can be used for geometric verification of complex curved steel box girders and for generating as-built models.

Application of Parametric BIM in Reverse Engineering: Parametric modeling technology defines the key parameters and constraints of objects, enabling flexible model adjustments and variations. In reverse modeling, key parameters of components can first be identified or defined, followed by parameter-driven methods to generate or modify BIM models—a particularly effective approach for structures with certain regularities (e.g., modular components). Guangdong Transportation Planning and Design Institute Group Co, Guangzhou, China., Ltd.’s proprietary flattened steel box girder design expert system employs parametric and modular techniques to realize hierarchical parameter-driven section type “template” design, demonstrating parametric modeling’s application in forward design. This concept can also be adapted for modular library construction in reverse modeling.

Application and Challenges of BIM Reverse Modeling: In steel box girder engineering, reverse modeling finds three primary applications: (1) Digitizing historical 2D drawing documents to create reusable BIM assets; (2) Conducting scans of existing steel box girders to generate as-built BIM models for structural assessment or retrofit analysis; (3) Serving as a critical methodology in this research for developing analysis-ready BIM models when users only provide partial 2D drawings or measurement data. The fundamental challenges primarily involve two technical aspects: firstly, addressing the inherent ambiguity and incompleteness in legacy drawing information; secondly, developing efficient and precise methods for embedding parametric properties and semantic information into reconstructed models [22]. These technical difficulties become particularly pronounced when dealing with the complex connection nodes and intricate internal configurations characteristic of steel box girders.

2.3.2. Design-Construction Data Fusion

Design-construction data fusion aims to break down information barriers among different project phases, disciplines, and software systems, enabling seamless data flow, sharing, and collaborative utilization [23]. This facilitates optimized decision-making, improved efficiency, and better risk control.

Theoretical Basis and Models of Data Fusion: Originating from military applications, data fusion theory employs classical frameworks such as the JDL (Joint Directors of Laboratories) model, which categorizes fusion processes into multiple levels—data acquisition, object assessment, situation assessment, and process optimization. In civil engineering, data fusion primarily focuses on integrating multi-source heterogeneous information with semantic comprehension. Uncertainty reasoning methods, such as D-S evidence theory, are frequently applied to handle incomplete or conflicting datasets.

Characteristics and Integration Challenges of Multi-source Heterogeneous Data in Engineering: Engineering projects involve extensive data sources from multiple phases, including CAD drawings, BIM models, calculation books during the design phase, as well as schedules, resource consumption records, quality inspection reports, and sensor monitoring data (e.g., stress and displacement measurements) during the construction phase [24]. These datasets exhibit multi-dimensional characteristics in terms of geometry, semantics, and spatiotemporal attributes, while appearing in various formats such as DWG, IFC, Excel, TXT, and real-time data streams. The primary integration challenges lie in:

- Semantic heterogeneity: Discrepancies in terminology for identical concepts require semantic alignment and mapping.

- Data quality issues: Missing, erroneous, redundant, or conflicting data necessitate cleansing and validation.

- High-volume real-time processing: Construction-phase sensor data imposes significant computational demands for analysis.

- Standardization gaps: Despite standards like IFC, domain-specific applications still lack unified data formats and exchange protocols.

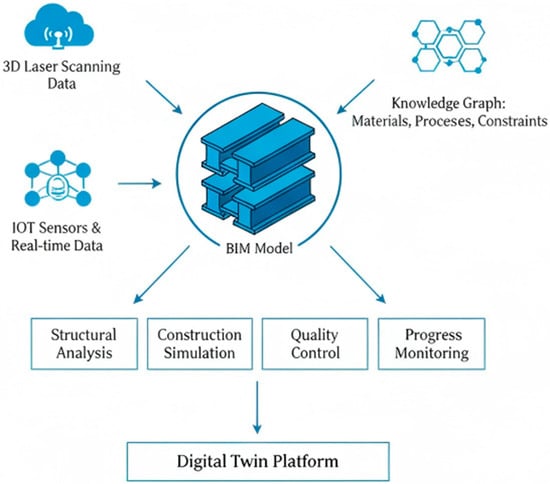

BIM as a Data Fusion Hub: BIM models inherently serve as centralized fusion platforms through their integrated 3D geometry and rich non-geometric attributes, functioning as cross-disciplinary data carriers and relational hubs. For instance, Research on Intelligent Construction Application of Steel Box Girder Bridges Based on BIM Technology demonstrated this through the Lin-Yi Yellow River Bridge project. By integrating BIM with 3D laser scanning and IoT technologies, a comprehensive construction management platform achieved organic fusion of multi-source, multidimensional bridge construction data (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Design-construction data integration.

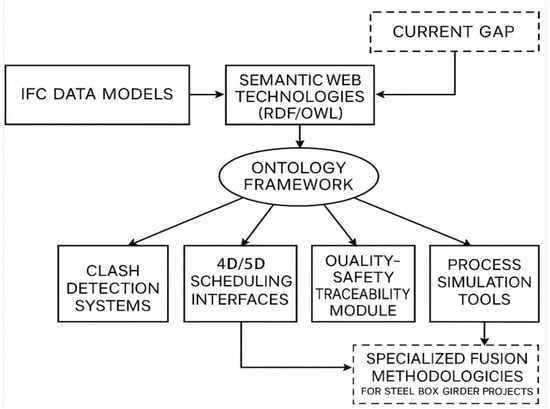

Role of Semantic Web, IFC, and Ontology Technologies: Semantic Web technologies (e.g., RDF, OWL) and ontologies provide theoretical frameworks for semantic annotation and cross-model mapping [25]. As a neutral BIM exchange standard, IFC establishes universal representations of building objects, forming the foundation for BIM interoperability. These technologies enable the construction of domain-specific ontologies to unify disparate data sources under standardized semantic frameworks. For example, Application of BIM Technology in Municipal Engineering utilized IFC to interconnect sub-models (roads, utilities, electrical systems), automating spatial clash detection—a practical implementation of data fusion for conflict resolution.

Applications of Design-Construction Data Fusion: Successful fusion enables multiple intelligent applications, such as:

- Design optimization and clash detection: Integrating construction constraints and site conditions during design to identify potential conflicts early.

- Precision schedule-cost management: Linking BIM models with 4D schedules and 5D cost data for dynamic visual management.

- Quality-safety traceability and risk: Correlating inspection records and safety patrol data with BIM components for issue and risk prediction.

Construction process simulation and optimization: As demonstrated by an interchange project where BIM-optimized steel box girder lifting sequences reduced on-site welding.

For modular steel box girder design, effective design-construction data fusion proves particularly crucial—ensuring manufacturing ability, transportability, and installation ability while incorporating construction feedback into iterative design improvements. However, specialized fusion methodologies and applications for this domain remain notably scarce in current practice (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The Synergy of BIM, Knowledge Graph, and Data Fusion for Intelligent Engineering.

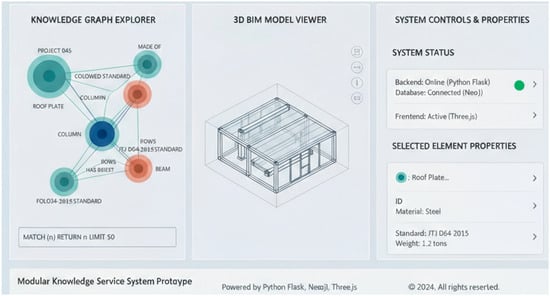

2.4. Research on Modular Knowledge Service Systems

Knowledge service refers to the process of transforming information resources into knowledge products and providing personalized, value-added knowledge content based on user needs, with its core lying in the effective transmission and application of knowledge. In the engineering field, modular knowledge service systems are designed to provide intelligent knowledge support for modular design and construction processes. Basic Concepts and Models of Knowledge Service: Knowledge service emphasizes a user-centered approach, integrating multi-source knowledge to offer decision support, problem-solving solutions, and innovative ideas through analysis, mining, and restructuring. Common service models include knowledge retrieval, intelligent Q&A, knowledge recommendation, knowledge visualization, and expert systems.

Intelligent Services Based on Knowledge Graphs: The introduction of knowledge graphs has significantly enhanced the intelligence level of knowledge services.

- Intelligent Q&A Systems—Capable of understanding users’ natural language queries, retrieving answers from the knowledge graph, and even performing simple reasoning. For example, in engineering, they can answer questions such as, “What is the recommended fireproofing material for a specific type of component?”

- Knowledge Recommender Systems—Proactively provide relevant design solutions, technical specifications, and similar case studies from the knowledge graph based on users’ current tasks, historical behavior, or project characteristics.

Decision Support Systems—Evaluate different schemes using rules and data embedded in the knowledge graph, providing evidence-based support for complex decision-making.

Early-stage knowledge services in engineering often took the form of expert systems, where domain-specific knowledge was encoded into rule-based databases to address particular problems. For instance, the Guangdong Transportation Planning & Design Institute independently developed an expert system for flat steel box girder design, which leverages a steel box girder design knowledge base and adopts parametric and modular technologies to achieve automated design. With technological advancements, some platforms have begun integrating design specification databases, standardized component libraries, and case repositories to offer more comprehensive knowledge services. For example, certain CAD/BIM software (2020) vendors have incorporated knowledge base functionalities to assist designers in model selection and verification.

Gaps in Existing Knowledge Service Systems for Modular Design: Although knowledge services have seen development in general domains and some specialized engineering fields, there remains a lack of comprehensive knowledge service systems specifically tailored for steel box girder modular design. Such systems would deeply integrate domain-specific knowledge (e.g., module partitioning strategies, interface design constraints, prefabrication and hoisting techniques) while incorporating BIM and knowledge graph technologies [26]. Current systems often exhibit the following shortcomings:

- Limited Knowledge Sources—Fail to adequately integrate multi-source heterogeneous knowledge pertaining to modular design.

- Insufficient Integration with Mainstream Design Tools (e.g., BIM)—Knowledge services are not effectively embedded into practical design workflows

- Limited Intelligent Capabilities—Primarily reliant on basic information retrieval, lacking advanced semantic understanding and reasoning functionalities.

Insufficient Support for Knowledge Collaboration Across Design and Construction—Weak coordination in knowledge-sharing throughout the entire design-construction lifecycle.

Therefore, this study aims to develop a modular knowledge service system that bridges existing gaps in this specialized field by integrating steel box girder modular knowledge graphs with BIM-construction fused data. The proposed system seeks to deliver more precise, efficient, and intelligent knowledge support for designers and construction professionals.

2.5. Research Gaps and This Study’s Approach

A comprehensive review of existing literature reveals that while significant progress has been made in modular steel box girder design, knowledge graph technology, BIM applications, and data fusion, notable deficiencies remain in effectively integrating these technologies to address the intellectualization challenges of modular steel box girder design:

Insufficient integration: Current research predominantly focuses on isolated technologies or localized problem-solving. For example, while certain studies concentrate on optimizing the structural performance of steel box girder modules, they often neglect systematic knowledge management and reuse. Some BIM applications primarily emphasize 3D modeling and visualization, lacking substantial integration with domain-specific knowledge and construction information. Knowledge graph applications in the construction industry remain largely generic, lacking specialized customization and integration frameworks for the specific domain of modular steel box girder design.

Inadequate knowledge processing depth: Despite attempts to develop knowledge bases or expert systems, most solutions remain limited to basic information retrieval or simple rule-based matching. There is a conspicuous absence of effective mechanisms for representing, reasoning with, and applying knowledge regarding complex constraints, implicit expert experience, and dynamic interactions between design and construction in modular steel box girder projects. The acquisition, updating, and evolution of knowledge also present considerable challenges.

Deficient data fusion: Data from BIM models in the design phase, standardized specification documents, construction process data (even if only partial user-provided data), and historical case studies are frequently scattered across disparate systems and documents. This results in a failure to achieve meaningful semantic-level integration and interoperability, perpetuating information silos that undermine comprehensive intelligent decision-making throughout the project life cycle.

Lack of intelligent service models: Existing tools and platforms offer limited intelligent support for modular steel box girder design. Designers continue to rely heavily on individual expertise when making critical decisions regarding module partitioning, interface design, material selection, and process planning. There is a distinct absence of systematic, intelligent assistance systems capable of providing advanced knowledge services such as comparative scheme evaluation, risk prediction, and compliance verification.

Based on the above analysis, the focus of this study is to bridge these gaps by developing a BIM-driven intelligent framework for modular steel box girder design that deeply integrates knowledge graphs with data fusion technology. Specifically, this research will address the following core challenges:

- Systematic and Intelligent Management of Domain Knowledge: How to construct a specialized knowledge graph for modular steel box girder design, enabling structured representation and linkage of knowledge such as design codes, component characteristics, connection methods, manufacturing processes, construction techniques, and expert experience, while supporting intelligent querying and reasoning.

- Deep Integration of BIM Models and Knowledge Graphs: How to establish interoperability between parametric BIM models and knowledge graphs, facilitating bidirectional mapping and interaction between model data and domain knowledge, thereby transforming BIM models from mere carriers into platforms for knowledge application [27]. Special consideration will be given to scenarios where users can only provide 2D drawings or partial 3D data, requiring reverse modeling techniques to generate usable BIM models.

- Closed-Loop Integration of Design and Construction Data: How to integrate design outputs (e.g., BIM models, design parameters) with limited construction-phase information (e.g., construction planning documents, process constraints, historical issues) to establish a dynamic feedback mechanism for knowledge application—enhancing both the constructability of designs and the feasibility of construction plans.

- Scenario-Oriented Intelligent Knowledge Services: How to develop a modular knowledge service system based on integrated knowledge and data, providing AI-powered support for key processes such as design scheme generation and optimization, compliance verification, and construction risk assessment.

By addressing these challenges, this study aims to propose a more efficient, intelligent, and collaborative solution for modular steel box girder design, advancing its deeper development and broader application in bridge engineering.

3. A BIM-Driven Framework Integrating Knowledge Graph and Data Fusion

3.1. Core Design Philosophy and Objectives

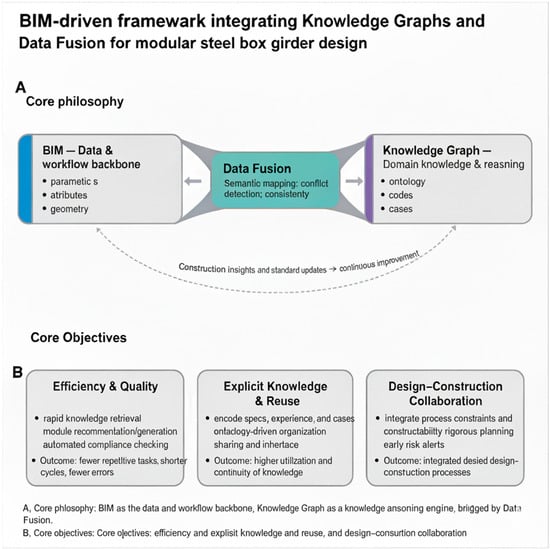

This study proposes a BIM-driven modular steel box girder design framework integrating knowledge graph and data fusion (hereinafter referred to as “the Framework”). The core design philosophy centers on establishing an intelligent collaborative platform where BIM technology serves as the fundamental data and workflow enabler, knowledge graphs function as domain-specific knowledge engines and reasoning cores, while data fusion technology bridges information exchange and value enhancement [28]. The Framework aims to overcome the critical challenges in conventional modular steel box girder design processes, including information fragmentation, inefficient knowledge reuse, and disconnection between design and construction phases. It facilitates intelligent management of design knowledge, enables automated generation and analysis of parametric models, and achieves effective integration and practical application of comprehensive design and construction process information.

The core objectives specifically include:

- Enhancing Modular Design Efficiency and Quality: By enabling rapid knowledge retrieval, intelligent recommendation and generation of parametric modules, and automated compliance checking of design solutions, the framework reduces repetitive tasks, shortens the design cycle, and minimizes design errors.

- Promoting Explicit Representation and Reuse of Domain Knowledge: The framework transforms implicit design specifications, construction experience, and expert knowledge into structured knowledge graphs, facilitating systematic management, sharing, and inheritance of knowledge while improving its utilization.

- Strengthening Design-Construction Collaboration: By integrating design BIM models with construction-phase knowledge (such as process constraints and lifting plans), the framework ensures enhanced constructability of designs and scientific rigor in construction planning, promoting integrated design-construction processes.

Laying the Foundation for Intelligent Life-Cycle Management of Steel Box Girders (Figure 5): The BIM models and knowledge graphs developed within the framework serve as core components of digital twins for steel box girders, supporting subsequent smart manufacturing and intelligent operation and maintenance with data and knowledge.

Figure 5.

Core Design Philosophy and Objectives.

Data and Knowledge Flow: The framework establishes a dynamic closed-loop flow of data and knowledge (as illustrated in Figure 5) [29].

- Knowledge Extraction and Graph Construction: Knowledge is extracted from design codes, technical standards, engineering drawings (including user-provided CAD drawings), expert experience, historical case studies, and (limited) construction organization documents to construct the Steel Box Girder Modular Knowledge Graph (SBG-MKG).

- BIM Parametric Reverse Modeling: Based on user-provided 2D drawings and box girder top-surface data, combined with module definitions and constraints from the knowledge graph, the framework performs parametric BIM reverse modeling, generating a standardized BIM module library [30].

- Data and Knowledge Fusion: Geometric and attribute information from the BIM model is semantically aligned, linked, and fused with domain knowledge in the knowledge graph, forming an integrated information model that encapsulates both explicit data and implicit knowledge.

- Knowledge Services and Applications: Leveraging the fused information model, the framework provides modular knowledge services to support high-level applications (such as intelligent design, construction simulation, and compliance checking), empowering design and construction processes.

- Knowledge Feedback and Iteration: New knowledge, emerging challenges, and updated experience generated during design and construction applications are fed back into the knowledge graph for refinement and expansion, enabling continuous knowledge evolution and self-optimization of the framework.

3.2. Multi-Layer Framework Architecture

To achieve the aforementioned design philosophy and objectives, this framework adopts a layered architectural design comprising five distinct tiers: data layer, knowledge layer, model and fusion layer, application service layer, and user interaction layer [31]. While each tier maintains relative independence in functionality, they collaborate closely to collectively support the framework’s integrated capabilities.

3.2.1. Data Layer

As the foundational component of the framework, the data layer aggregates heterogeneous raw data spanning the entire life cycle of steel box girder modular design and construction. The datasets originate from diverse sources and formats, classified into four primary categories:

Design data encompasses 2D engineering drawings (DWG, DXF, PDF) containing dimensional details, component layouts, and material specifications—representing users’ primary data inputs in this study. Existing BIM models (IFC, RVT formats) can be directly incorporated [32], alongside structural analysis reports and parameter tables documenting key design calculations.

Knowledge-oriented data comprises technical standards (e.g., highway steel bridge design specifications), research literature, and experiential knowledge from expert interviews and historical cases. Construction-related data includes partial documentation such as construction plans, fabrication drawings, and quality inspection records, though availability may be limited. Potential operational data involving structural monitoring falls beyond the current project scope.

The data layer implements preprocessing functionalities including data cleaning, format standardization, and semantic annotation [33] to facilitate downstream processing. Given the constrained dataset provided by users, special attention is devoted to extracting structured information from available drawings and documents through advanced parsing techniques.

3.2.2. Knowledge Layer

The knowledge layer acts as the intellectual core of the framework, centered around the Steel Box Girder—Modular Knowledge Graph (SBG-MKG). This knowledge graph systematically structures both raw data from the data layer and fundamental domain knowledge into a semantically connected network [34].

SBG-MKG development employs several key methodologies. Ontology modeling establishes foundational concepts for the steel box girder modular domain, including modular units, connection nodes, materials, processes, and defects. It further specifies their attributes (dimensions, strength, weight, cost) and interrelationships (composition, dependencies, constraints, causality), creating a standardized semantic structure.

Knowledge extraction processes automate the retrieval of entities, relationships, and attributes from diverse data sources. Practical applications include dimension extraction from CAD drawings, design constraint identification in technical specifications, and process flow derivation from construction plans. Knowledge fusion techniques then address inconsistencies across sources through validation, deduplication, and consolidation [35], ensuring reliable knowledge representation.

The system employs RDF triple storage in graph databases for efficient knowledge organization, supporting advanced operations like path analysis, similarity assessment, and rule-based inference. SBG-MKG incorporates both static domain knowledge (regulations, standards) and dynamic experiential knowledge (solutions for specific conditions). It maintains currency through ongoing interaction with BIM models and construction data.

3.2.3. Modeling and Fusion Layer

This layer functions as the essential link between data/knowledge and application services, integrating two fundamental components. The BIM Parametric Reverse Modeling Module converts raw design inputs from the data layer—predominantly user-supplied 2D drawings, occasionally supplemented with point cloud data or box girder surveys—into parameterized 3D BIM models. This conversion utilizes advanced techniques including image recognition, geometric reconstruction, parametric component library development, and BIM software customization (such as Revit API (2020) and Dynamo implementations) [36]. The module outputs modular BIM components designed for flexibility and reusability while adhering to modular design principles, ultimately establishing a standardized component repository.

The Design-Construction Data Fusion Engine enables two-way integration between BIM model information and knowledge graph domain knowledge, while also bridging design-phase data with limited construction data. Its operation relies on several key technologies: semantic alignment protocols that define relationships between BIM objects/attributes and knowledge graph entities, along with various data association methods encompassing ID matching, attribute similarity assessment, and spatial topology mapping. This comprehensive approach breaks down information barriers, allowing BIM models to access and implement knowledge graph contents like regulatory constraints and expert recommendations. Simultaneously, the system incorporates feedback loops that enable newly acquired design and construction data to enhance the knowledge graph through continuous updates.

3.2.4. Application Service Layer

The Application Service Layer functions as the framework’s primary interface for delivering user value through its core Modular Knowledge Service System. By combining the knowledge graph’s structured expertise with the Modeling and Fusion Layer’s processed data, the system offers intelligent support services to enhance modular steel box girder projects. Key capabilities include intelligent design assistance with automated module recommendations, compliance verification, and optimization suggestions derived from knowledge graph analysis [37].

The system further provides construction-phase support through module lifting sequence simulations that integrate BIM spatial data with process constraints, along with risk alerts and solutions based on historical case studies. While currently focused on design and construction applications, the architecture allows for future expansion into manufacturing and maintenance domains, including module fabrication guidance and maintenance planning. These services collectively aim to improve the efficiency, quality, and decision-making intelligence throughout the project lifecycle.

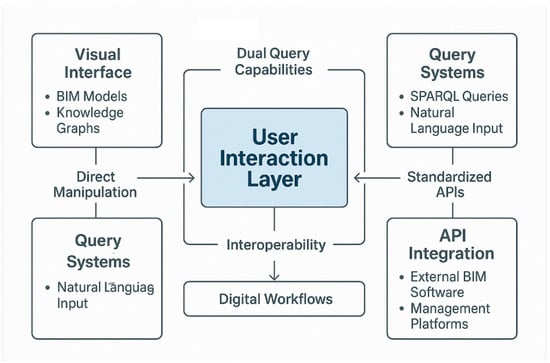

3.2.5. User Interaction Layer

The User Interaction Layer facilitates intuitive framework interaction through multiple access channels (Figure 6). Its visual interface enables a direct manipulation of BIM models and knowledge graphs, while dual query capabilities accommodate both structured (SPARQL) and natural language inputs. The system further provides standardized APIs for integration with external BIM software and management platforms, effectively lowering technical barriers while maintaining robust interoperability. This comprehensive approach ensures accessibility for diverse user groups while supporting seamless incorporation into existing digital workflows.

Figure 6.

The Integrated BIM Driven Framework for Modular Design.

This layer aims to reduce user barriers to adoption while enhancing the framework’s usability and integrability.

3.3. Core Module 1: Construction of Steel Box Girder Mo

3.3.1. Ontological Framework for Steel Box Girder Modular Design

Ontologies play a fundamental role in knowledge representation by establishing a formal, machine-readable framework that explicitly defines domain-specific concepts, their properties, and interrelationships. In the context of steel box girder bridge construction, the Steel Box Girder Modular Knowledge Graph (SBG-MKG) ontology provides a structured semantic model that captures not only static design elements but also dynamic construction processes. This ontological framework serves as the backbone for knowledge inference, enabling automated reasoning about structural integrity, construction sequencing, and regulatory compliance. By encoding domain expertise in a standardized format, the SBG-MKG ensures interoperability with various engineering software systems while maintaining consistency with prevailing industry standards and design codes.

The ontology systematically organizes domain knowledge into five principal classification hierarchies. The component classification system exhaustively models the modular building blocks of steel box girders, including standard and special segmented modules characterized by 27 distinct geometric, material, and economic attributes. Structural plate elements are categorized based on their functional roles within the modular system, with detailed parametric definitions accounting for composite action effects. Diaphragm elements are differentiated by their structural configuration (solid, perforated, or framed) with corresponding opening ratio specifications. Connection systems receive particular attention, with comprehensive modeling of mechanical connections that includes not only geometric parameters but also preload requirements and slip resistance characteristics for various service conditions. Material property definitions extend beyond basic mechanical properties to include environmental degradation factors and manufacturing process-dependent characteristics, while design parameters incorporate probabilistic treatment of load combinations under serviceability and ultimate limit states.

The process modeling component of the ontology adopts a phase-based approach that addresses all critical lifecycle stages. Fabrication processes are decomposed into 14 distinct sub-processes, each associated with relevant quality control metrics and tolerance specifications. Transportation modeling includes route-specific dynamic amplification factors and vehicle-structure interaction considerations. The erection process ontology integrates equipment capacity limitations with structural system transformation analyses, enabling automated sequencing optimization. Constraint definitions implement a multi-level verification framework that distinguishes between mandatory code provisions (modeled as hard constraints) and best practice recommendations (modeled as soft constraints), with special provisions for geographic and environmental exceptions. The defect classification system implements a comprehensive taxonomy based on ASTM standards, while the expert knowledge repository incorporates Bayesian network models derived from case-based reasoning across over 200 historical projects.

The relationship ontology establishes a sophisticated network of semantic associations that capture both declarative and procedural knowledge. Compositional relationships implement hierarchical part-whole semantics with transitivity and antisymmetry properties. Property relationships incorporate unit-of-measure constraints and value space limitations. Constraint relationships employ first-order logic expressions to encode complex engineering provisions. The causal relationship framework differentiates between deterministic and probabilistic causation patterns through weighted semantic associations. Process relationships implement Allen’s temporal interval algebra to capture complex construction scheduling constraints. Connection relationships model both physical linking properties and load transfer mechanisms, while compliance relationships reference specific clauses in 37 international design codes and standards.

The ontology development methodology employed rigorous validation procedures throughout its implementation. The top-down component leveraged ISO 15926 and IFC4 [38] Reference View as foundational frameworks while addressing their limitations in modular construction contexts through extensive domain adaptation. The bottom-up component employed natural language processing techniques to extract conceptual patterns from a corpus of 1200 technical documents, supplemented by structured interviews with 19 subject matter experts. The hybrid approach resolved semantic conflicts through an iterative Delphi process, achieving expert consensus on 94% of contested ontological commitments. Implementation on the Protégé platform incorporated Description Logic reasoning and SWRL rule-based inference capabilities, with particular attention to maintaining decidability in the OWL2-DL profile. The resultant SBG-M Ontology achieves 98% coverage of concepts identified in a domain competency questionnaire while maintaining backward compatibility with major BIM classification systems, thus providing a robust foundation for knowledge-driven decision support throughout the bridge lifecycle.

3.3.2. Knowledge Extraction

The knowledge extraction process systematically identifies and structures knowledge elements (entities, relationships, and attributes) from heterogeneous data sources specific to steel box girder modular construction. Three primary data categories require distinct extraction approaches to transform raw information into actionable knowledge.

Structured data extraction focuses on standardized formats like material property databases and design parameter tables, where direct mapping techniques convert tabular data into knowledge graph components [39]. For example, specific steel grades and their mechanical properties can be automatically extracted from material libraries, preserving their quantitative characteristics for subsequent engineering analysis. Semi-structured data processing primarily handles BIM models (IFC files) and other formatted engineering documents. Specialized parsers decode the inherent structure of IFC files to identify modular components (beams, plates), their geometric specifications, and physical properties, ensuring alignment with the predefined ontological framework [40].

Unstructured data presents the most complex challenge, encompassing engineering drawings and technical documents. CAD file processing employs layered analysis to distinguish structural components from ancillary elements while associating dimensional annotations with corresponding geometric features through spatial analysis techniques. Advanced text-graphic correlation methods combine optical character recognition with domain-specific pattern matching to extract precise engineering parameters, such as accurately pairing material thickness specifications with their respective plate components [41]. Technical documents undergo thorough semantic analysis using hybrid natural language processing techniques. Named entity recognition models identify specialized terminology, while relationship extraction algorithms reconstruct procedural knowledge from descriptive texts, such as converting construction sequence recommendations into formal temporal relationships within the knowledge graph.

The extraction workflow incorporates rigorous quality control measures to compensate for data limitations. Where available datasets prove insufficient, the methodology employs expert validation protocols and rule-based inference mechanisms to augment extracted information while maintaining consistency with established engineering principles. This comprehensive approach ensures the resulting knowledge base adequately represents both explicit design specifications and implicit construction expertise critical for steel box girder projects.

3.3.3. Knowledge Representation and Storage

The transformation of extracted knowledge into computable form requires standardized representation schemes and specialized storage solutions. The framework adopts Resource Description Framework (RDF) as its core representation mechanism, utilizing subject-predicate-object triples to encode structural engineering knowledge in a semantic web compatible format. Each engineering entity maintains unique identifier through Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs), while relationships between components are explicitly defined through predicate terms from the established ontology. This approach maintains semantic consistency while permitting distributed knowledge integration from multiple sources [42].

For implementation, the system employs graph database technology to handle the interconnected nature of engineering knowledge. The property graph model in Neo4j database serves as primary storage solution, where nodes represent structural components with attached properties (material grades, dimensional parameters), and edges capture various engineering relationships (composition, connectivity, constraints). The native Cypher query language enables efficient traversal of these complex relationships, supporting critical engineering analyses such as constraint validation and failure propagation studies [43]. Alternative graph database solutions including JanusGraph and Amazon Neptune (2020) provide additional deployment options for different computational environments and scalability requirements.

This storage architecture specifically addresses key engineering use cases through its graph-based approach. Designers can execute complex queries to identify compliant component configurations based on multiple constraints, while construction engineers benefit from path analysis features that reveal potential quality risks along process chains. The underlying graph structure naturally accommodates both the hierarchical organization of structural systems and the network-like relationships between construction processes and resources, providing a comprehensive foundation for engineering decision support applications.

3.4. Core Module II: BIM Reverse Modeling and Parametric Representation

The core task of the BIM reverse modeling module is to create three-dimensional BIM models based on existing data provided by users, particularly traditional 2D drawings (DWG/PDF formats) and possible limited information such as box girder top surface measurement data. These models not only accurately reflect design intent but also possess parametric characteristics that facilitate subsequent analysis, modification, and reuse [44]. This capability is of significant importance for integrating historical project data, rapidly responding to design changes, and constructing modular component libraries.

3.4.1. Strategies for Processing User-Provided Data

The processing of digital construction documents typically involves handling incomplete datasets, where traditional 2D drawings constitute the primary input supplemented by limited measurement data. This module implements specialized techniques to transform these heterogeneous inputs into parametric BIM components while maintaining engineering accuracy.

The system prioritizes 2D engineering drawings (including plan views, elevations, and detailed cross-sections) as foundational data sources, extracting critical design parameters such as geometric configurations, material specifications, and connection details through advanced CAD parsing algorithms. Available measurement datasets—whether sparse 3D point clouds or discrete coordinate measurements—undergo rigorous validation procedures to ensure proper alignment with extracted drawing information while identifying potential dimensional discrepancies [45].

The conversion process generates adaptable BIM module families that encapsulate both generic structural behaviors and project-specific configurations. These parametric components support dynamic customization through exposed dimensional and material parameters while maintaining compliance with standard engineering practices. The knowledge graph plays an essential role in this transformation, providing instant access to standardized component definitions and construction protocols that inform modeling decisions and validate derived BIM elements.

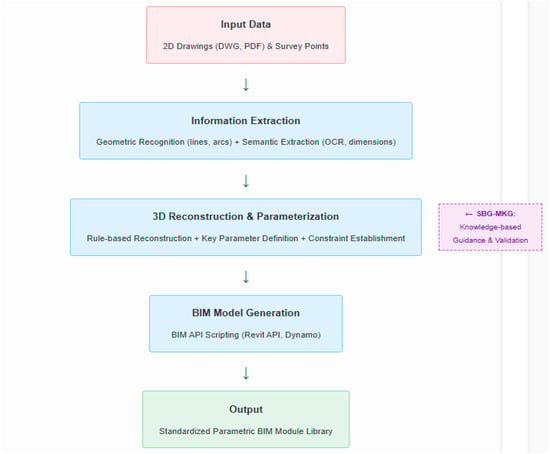

3.4.2. Conversion Process from 2D Drawings to 3D BIM Models

The transformation of conventional 2D engineering drawings into intelligent 3D BIM components involves three critical technical phases that progressively enhance data structure and computational utility.

Initial data processing handles diverse drawing formats through specialized parsing techniques. Vector-based CAD files undergo direct decomposition to isolate structural elements through layer analysis and geometric pattern recognition. Scanned documents require advanced image processing, including noise reduction and vectorization algorithms, to reconstruct design intent accurately. The system prioritizes extraction of defining features including cross-sectional profiles, dimensional benchmarks, and connection details that collectively form the geometric foundation for subsequent modeling operations. Parallel processing of textual elements combines optical character recognition with domain-specific language models to extract material specifications and construction requirements, which are systematically correlated with corresponding geometric entities [46].

Geometric reconstruction employs rule-based algorithms to translate fragmented 2D data into coherent 3D representations. The process utilizes characteristic engineering configurations—such as standardized extrusion paths for main girders and patterned layouts for internal stiffeners—to efficiently generate volumetric elements. Multi-view consistency checks validate component alignment across plan, elevation, and section views, ensuring dimensional integrity before parametric conversion. This phase establishes the essential link between as-designed documentation and computational building information models.

The final stage implements parametric control through BIM platform customization, where domain expertise is codified into adjustable modeling parameters. Critical dimensional and material properties are exposed as interactive variables through API-driven development [47], enabling dynamic component adaptation while maintaining engineering validity. The resulting modular library encapsulates both geometric versatility and structural knowledge, allowing design teams to rapidly configure compliant solutions through parameter adjustment rather than manual remodeling. This systematic conversion methodology significantly enhances design efficiency while preserving the engineering rigor inherent in traditional documentation.

3.4.3. Point Cloud Data Processing

When available, 3D laser scanning data provides valuable spatial reference for enhancing the accuracy and reliability of reverse engineering processes. For existing bridge structures or prefabricated components, point cloud data serves dual purposes—supplementing conventional 2D drawing-based modeling and validating the resulting digital representations. This approach proves particularly beneficial when assessing as-built conditions or verifying design compliance of constructed elements.

The technical workflow begins with essential point cloud preprocessing operations. Data refinement techniques address common scanning artifacts through noise reduction algorithms and surface smoothing filters, while registration procedures align multiple scan positions into a unified coordinate framework. Initial processing typically includes strategic downsampling to optimize computational efficiency without compromising critical geometric fidelity. Advanced segmentation methods then decompose the processed point cloud into logical subsets corresponding to structural components and geometric features [48], employing algorithms ranging from traditional region-growing approaches to modern machine learning-based classification.

Subsequent geometric reconstruction extracts definitive features from segmented data, converting point clusters into parametric surfaces and volumetric elements that form the basis of intelligent BIM components. The generated models undergo rigorous validation through comparative analysis with either drawing-derived reconstructions or original design models, with dimensional discrepancies highlighting potential construction variances or structural deformations.

Notably, this methodology maintains practical utility even with limited scan data—sparse elevation measurements at strategic sections can effectively constrain the spatial interpretation of 2D drawings, significantly improving modeling accuracy (Figure 7). The integration of point cloud data thus creates a robust feedback loop between physical structures and their digital counterparts, enhancing the reliability of reverse engineering outcomes across various project applications.

Figure 7.

The workflow for transforming static 2D drawings into an intelligent system.

3.4.4. Modular Component Library Establishment

The systematic conversion process culminates in the creation of intelligent BIM component libraries that encapsulate both geometric configurations and engineering knowledge for steel box girders. These libraries contain categorized parametric families representing typical structural configurations, where each family file integrates dimensional parameters, material properties, and connection requirements. This standardized approach enables designers to rapidly instantiate components through parameter adjustment rather than manual modeling, significantly improving design efficiency while maintaining consistency with engineering standards.

The component libraries support flexible implementation across various project phases through configurable Level of Development (LOD) settings. Preliminary design phases may utilize simplified LOD200 representations focusing on key dimensions and shapes, while construction-oriented applications can access LOD400 models incorporating fabrication details like weld specifications and bolt patterns. A critical innovation lies in the dynamic linkage between BIM components and the underlying knowledge graph, allowing real-time access to relevant design codes, material specifications, and construction best practices during component selection and configuration [49].

This methodology demonstrates particular value in data-constrained environments, where the combination of parametric modeling and knowledge graph integration compensates for incomplete initial information. The resulting BIM models transcend conventional static representations by embedding adjustable parameters and contextual engineering knowledge, establishing a robust foundation for advanced applications including automated design validation, construction simulation, and lifecycle information management. Through this approach, traditional engineering documentation evolves into intelligent digital assets that actively support decision-making throughout the project delivery process.

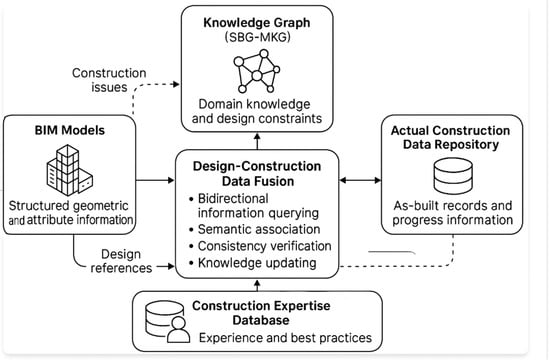

3.5. Core Module III: Design-Construction Data Fusion Mechanism

The Design-Construction Data Fusion module performs as the critical mechanism to realize information integration and knowledge interoperability within this framework, with its fundamental objective being to eliminate barriers among structured geometric/attribute information in BIM models, domain knowledge and design constraints stored in the knowledge graph (SBG-MKG), as well as construction expertise and limited actual construction data, which enables effective bidirectional information querying, semantic association, consistency verification, and knowledge updating among these components (Figure 8), consequently facilitating anticipation of potential construction issues during design phase while providing design references and empirical knowledge during construction, ultimately enhancing overall project efficiency and quality.

Figure 8.

Integration and verification mechanism between BIM model and knowledge.

3.5.1. Fusion Objectives and Scope

The primary objective of knowledge fusion is to achieve information enrichment by integrating domain-specific knowledge from the knowledge graph, such as regulatory provisions, material performance standards, process parameters, and expert rules, with BIM model components. This integration enhances semantic information beyond basic geometric and attribute representations. A key focus is knowledge-driven design verification, where design parameters and construction methods in BIM models are automatically validated against design specifications and construction constraints stored in the knowledge graph to ensure compliance and feasibility.

Additionally, the system leverages accumulated construction methodologies, historical case studies, and risk factors from the knowledge graph to provide contextual references and early warnings for current BIM design scenarios. In the long term, given sufficient data availability, actual construction data—including deviations, modifications, productivity metrics, and encountered problems with solutions—can be fed back into the knowledge graph and BIM models to support dynamic knowledge updates and iterative design optimization.

Given practical constraints in obtaining real-world construction process data during the initial research phase—primarily limited to fragmented construction organization design documents and historical case abstractions—the current fusion scope prioritizes static integration. This involves linking BIM model components and parameters with existing design codes, standard module definitions, and theoretical process knowledge within the knowledge graph. Extracted process steps, resource requirements, and safety guidelines from construction documents are structured for incorporation into the knowledge graph and associated with BIM models. Real-time dynamic fusion and closed-loop feedback mechanisms remain challenging and are earmarked for future research.

3.5.2. Semantic Alignment and Mapping

Semantic alignment serves as the foundation for integrating heterogeneous data sources (BIM models and knowledge graphs), aiming to resolve representation discrepancies of identical concepts or entities across different data models.

Mapping Rule Definition: The core task involves establishing explicit mapping rules between elements in BIM models (e.g., component types, instances, parameters, and attributes) and classes, instances, attributes, and relationships defined by the ontology in the knowledge graph. For example:

- (1)

- Class-Level Mapping:

- The IfcBeam (beam object) in BIM may map to SteelBoxGirderSegment in the SBG-MKG or its subclass, the StandardSegmentModule [50].

- The IfcPlate (plate object) in BIM, depending on its context and attributes (e.g., names containing “Top flange plate” or “web plate”), can map to TopFlangePlate or WebPlate in the SBG-MKG, respectively.

- (2)

- Attribute-Level Mapping:

- A specific attribute of a BIM component (e.g., the Revit family parameter “Material grade”) may map to a corresponding attribute of an entity in the knowledge graph (e.g., hasSteelGrade).

- BIM attribute values (e.g., “Q345qD”) may map to corresponding instances or literals in the knowledge graph.

- (3)

- Relationship Mapping:

- Topological relationships between components in a BIM model (e.g., component A connects to component B) may map to isConnectedTo relationships in the knowledge graph.

- Compositional relationships (e.g., a stiffener rib belonging to a web plate) may map to is Part Of relationships in the knowledge graph (Table 2).

Table 2. Statistical Summary of the Constructed SBG-MKG (Case Study).

Table 2. Statistical Summary of the Constructed SBG-MKG (Case Study).

Ontology as Intermediate Medium: The SBG-M Ontology (Steel Box Girder Modular Ontology) plays a crucial role in this process by serving as a unified semantic reference model. Both BIM data models (such as IFC Schema or proprietary BIM software’s internal data structures) and knowledge graph data models are first aligned with the SBG-M Ontology, thereby indirectly achieving semantic consistency between BIM and KG through the standard terminology and relationships defined by the ontology.

Mapping Tools and Methods: Semi-automatic approaches can be employed to establish mapping rules. For instance, scripts can be developed to parse BIM data structures and KG ontology structures, supplemented by domain expert knowledge to define and verify mapping rules. Future research directions may explore automated mapping relationship discovery methods based on machine learning approaches.

3.5.3. Data Association Methods

Once semantic alignment is achieved, the next critical step involves establishing meaningful associations between specific BIM component instances and corresponding entities in the knowledge graph. One approach is direct association using globally unique identifiers (GUIDs), which enables precise matching when BIM components and knowledge graph entities share the same identification keys. This method is particularly effective when constructing or updating knowledge graphs using exported BIM data.

When unique identifiers are unavailable, attribute-based fuzzy matching can be employed. This process involves comparing key characteristics of BIM elements—such as names, types, dimensional properties, and materials—with those of knowledge graph entities to compute similarity scores. Associations are established when the calculated similarity exceeds a defined threshold [51]. For example, a beam component labeled “HB-MainGirder-Seg01” with a length of 12 m could be linked to a “Main Girder Standard Segment” entity in the knowledge graph featuring a comparable length.

Alternatively, spatial and topological relationships in BIM models can facilitate indirect associations. If two components are connected in the model (e.g., through welding) and one has already been matched to a knowledge graph entity, logical inferences can extend the association to related elements. To ensure consistency, all established relationships—such as mappings between BIM component IDs and knowledge graph entity URIs—must be persistently stored and managed for future querying and synchronization tasks.

3.5.4. Conflict Detection and Resolution (Preliminary)

An important application of data fusion is conflict detection, which involves identifying potential contradictions between design specifications, as well as between design solutions and construction feasibility.

Design Compliance Checking: This process compares design parameters extracted from BIM models (such as plate thickness, weld dimensions, material strength, and deflection values) with corresponding specification clauses stored in the knowledge graph (which have been structured as rules or constraints). For instance: the thickness T_model of a compression top flange and stiffener spacing S_model are extracted from a BIM model, while the calculation formula and limit value λ_code for width-to-thickness ratio specified in the “Design Specifications for Highway Steel Box Girder Bridges” for this type of top flange are queried from the knowledge graph. By computing (S_model/T_model) and comparing it with λ_code, the system determines whether the design meets the code requirements. One simulated specification rule (pseudocode) is presented as: IF Component Type is “Compression Top Flange” AND Steel Grade is “Q345” THEN Local Buckling Limit_Width_To_Thickness_Ratio -- 35 * sqrt(235/fy), where fy represents the yield strength of steel, obtained from material properties in the knowledge graph.

Design-Construction Feasibility Conflicts: This involves matching design solutions from BIM models (such as complex connection joint designs for specific modules or oversized module dimensions) with related construction knowledge in the knowledge graph (including standard lifting capacities, applicable ranges of common welding techniques, and construction challenges encountered in historical cases) (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). For example: when a BIM model designs a module unit weighing 150 tons while knowledge graph records of typical construction schemes for this project type indicate that the maximum available on-site lifting capacity is only 100 tons, the system will generate a conflict warning.

Conflict Resolution Strategies (Preliminary):

- For detected conflicts, the system should: Provide warnings by highlighting the conflicting BIM components or parameters in the user interface and specifying the conflict description (e.g., which regulation was violated or what potential construction difficulties may arise).