Abstract

Optimizing window insulation is crucial for reducing heat loss and energy use in industrial buildings in Northeast China’s severe cold regions. Based on six typical building prototypes identified via cluster analysis of field survey data, this study used DesignBuilder (Version 6.1.0.006) to simulate the influence of key parameters for insulation materials (type, thickness, emissivity) and installation methods (position, air cavity, operation). Simulations reveal that the energy-saving potential is inversely proportional to a building’s existing thermal performance, reaching a maximum of 10.3%. Regarding material selection, results indicate that reducing surface emissivity from 0.92 to 0.05 effectively substitutes for approximately 20 mm of physical insulation thickness. Transparent films prioritize daytime comfort, raising nighttime temperatures by 1.5 °C, whereas opaque panels excel at nighttime insulation with a 2.28 °C increase. Techno-economic analysis identifies low-emissivity foil combined with EPS or XPS as the most cost-effective strategy, achieving rapid payback periods of 0.6–3.2 years. Regarding installation, an external configuration with a 20 mm air cavity and vertical operation was identified as optimal, yielding 1.5–2.0% greater energy savings than an internal setup. This study provides tailored retrofitting strategies for industrial building windows in these regions.

1. Introduction

According to data from the China Building Energy Conservation Association, in China, building energy consumption accounts for approximately 46.5% of the nation’s total energy consumption. Improving building energy performance has become a crucial approach to achieving carbon neutrality goals. Following current consumption trends, research indicates building energy demand could reach 50% of the total by 2030 without strict energy-saving measures [1]. Windows are a primary source of this inefficiency. Despite providing essential functions like daylighting and views [2,3], their poor thermal performance can account for up to 60% of a building’s total heat loss [4,5,6]. Enhancing the thermal performance of windows through passive design strategies is an effective approach to reducing building energy consumption and improving the indoor thermal environment.

As a traditional heavy industrial base, Northeast China saw the construction of a large number of single-story industrial buildings in the mid-20th century. Due to factors such as tight construction schedules and limited building technology, their building envelopes were generally rudimentary with poor thermal performance. Additionally, the region has a typical high-latitude, severely cold climate, characterized by an average winter temperature as low as −16.23 °C and a heating season lasting up to six months. With rising living standards and increased demand for thermal comfort among workers, the use of heating equipment has become more prevalent, further exacerbating energy consumption pressures [7]. According to statistics, winter heating accounts for over 50% of the total energy consumption in these industrial buildings. The annual electricity consumption of unit area fans can reach up to 3500 kWh, and heat loss from windows can account for 30–50% of the total heating energy consumption [8]. Therefore, improving the thermal performance of windows is a crucial aspect of the energy-saving retrofitting of industrial buildings.

Reducing heat loss through windows during the heating season is one of the most effective means of maintaining indoor temperatures, and numerous studies have demonstrated significant energy-saving potential through comprehensive performance enhancements [9,10,11,12,13]. Comprehensive thermal modernization, which includes the insulation of all external partitions and the optimization of HVAC systems, is widely recognized as the most effective approach for enhancing energy efficiency [14]. However, the implementation of such extensive measures faces significant challenges in the target region. Due to economic constraints in Northeast China, typical industrial enterprises often lack sufficient budgets for full-scale retrofits characterized by high capital costs and extended investment payback periods [15]. Furthermore, comprehensive renovations typically require the suspension of production activities, rendering them practically difficult to implement. Consequently, building owners prioritize cost-effective retrofit strategies that minimize operational disruption. As windows are identified as the envelope component with the lowest thermal resistance, targeting them yields the highest marginal energy-saving benefit. Thus, despite the superior theoretical performance of comprehensive retrofits, their application within the existing industrial building stock remains limited due to these practical barriers. This reality necessitates a more pragmatic and low-intrusion alternative.

As a more practical alternative to high-performance windows, the window insulation system is a typical passive energy-saving strategy. It consists of the existing window, an insulation layer, and an air cavity between them, which can effectively increase the overall thermal resistance assembly and compensate for its insufficient insulation performance [16,17,18]. The system enhances solar heat gain during winter days while preventing heat loss at night, improving both thermal performance by enhancing comfort and reducing the heating load and practicality as a retrofit solution by lowering costs and preserving the original window appearance [19]. It can address the energy waste and air quality problems caused by coal-fired heating in the severe cold regions of Northeast China. Furthermore, as the industrial buildings in this region predominantly originate from prefabricated construction systems, they possess inherent potential for sustainable adaptation. Recent cutting-edge research has significantly advanced the understanding of low-carbon strategies in prefabrication. For instance, latest research introduced multidimensional algorithm-based models and hybrid computational visualization techniques to optimize the carbon efficiency of prefabricated structures [20,21,22]. These studies cover aspects ranging from geometric 3D ratios to materialization phases. They underscore the critical role of computational optimization in driving the low-carbon transition of the prefabricated building sector. This theoretical framework supports the necessity of applying targeted parameter optimization, to improve the energy performance of the existing prefabricated industrial stock.

The energy-saving mechanisms of window insulation systems have been extensively studied globally [23,24,25], primarily focusing on winter thermal retention. Previous research also clarified the system’s significant retrofit potential for older windows [26,27], achieving an approximate 60% performance enhancement. The system reduces U-values by about 40% for double-glazed and 25% for triple-glazed windows. These findings provide an important basis for determining the research parameters for the components of the insulation system in this study. Recent advancements representing the latest research have further expanded the scope to include summer cooling and dynamic shading performance. For instance, the energy benefits of advanced window strategies for commercial buildings have been quantified [28], while the thermal performance of thermally activated internal louvers has been explored [29]. However, current research has predominantly focused on residential buildings, lacking a systematic analysis of the energy-saving mechanisms in the unique environment of industrial buildings. Due to their high ceilings, simple spatial division, low occupant density, and thermal comfort standards that differ from residential or office buildings, targeted research is necessary on the applicability and optimization pathways of window insulation systems.

According to previous studies [30,31], it can be demonstrated that changes in the thermal parameters of a window insulation system significantly affect heat loss through windows in winter. Since the basic conditions of the windows are given in a retrofitting project, it is essential to uncover the correlation between the system’s variable thermal parameters and its energy-saving effect. However, most previous research has focused on the comprehensive effects of various component parameters (such as Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR), Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC), and optimal positioning schedules for insulation layers) on energy savings [32,33,34,35], lacking focus on specific application scenarios, making it difficult for the generalized findings to translate effectively into complex practical scenarios. Therefore, it is necessary to systematically investigate the energy-saving mechanisms and optimal configurations of each component under different thermal environments from the perspective of thermal parameter control, while considering actual industrial building scenarios.

To bridge these gaps, this study systematically evaluates the performance of an adjustable window insulation system tailored for industrial building retrofits. The research focuses on traditional single-story industrial buildings located in the severe cold regions of Northeast China, defined by the General code for building environment (GB 55016-2021 [36]). The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

First, this study establishes a representative typological baseline for severe cold regions, offering a region-specific perspective that complements existing generic models. Through field surveys of 40 industrial buildings in Northeast China, this research employs a feature clustering method to extract six representative prototypes. It explores the complex diversity of window structures, orientations, and thermal characteristics, thereby ensuring that the simulation baseline is statistically accurate and reflective of actual retrofit needs (Section 2.1).

Second, it provides a detailed parametric analysis that systematically quantifies the thermal performance governed by material properties and installation configurations, while specifically evaluating the cost-effectiveness of insulation materials. This study establishes an evaluation framework encompassing two primary dimensions, Material and Installation, and systematically analyzes six key secondary indicators including material type, thickness, emissivity, position, cavity thickness, and adjustment method. The results in Section 3.1 explicitly quantify distinct energy-saving mechanisms, revealing that transparent materials utilize the greenhouse effect to reduce heating loads by up to 10.3% while opaque materials rely on thermal resistance to increase nighttime indoor temperatures by 2.28 °C, and confirming the non-linear coupling effects between insulation thickness and surface emissivity. Furthermore, the analysis in Section 3.2 verifies the performance superiority of external placement and the higher airtightness stability of vertical adjustment systems, while determining the optimal 20 mm air cavity threshold.

Third, this research translates theoretical simulation data into practical optimization strategies for engineering applications. By synthesizing simulation findings, the study formulates material selection strategies distinguishing between transparent and opaque types based on operational timing in Section 3.1.3, and evaluates installation strategies comparing the efficiency of single-sided exterior application against the ultimate performance of double-sided additions in Section 3.2.3. Moreover, to bridge the gap between theoretical optimization and engineering practice, Section 3.3 provides precise mechanical operation suggestions through the design of integrated roller and modular folding systems, offering a complete technical pathway for retrofitting implementation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Survey and Prototype Development

2.1.1. Sample Selection and Data Collection

A survey of 40 representative industrial buildings was conducted during the 2024 winter heating season, using on-site observation and field measurements to collect foundational data for subsequent prototype development and simulation analysis. The survey gathered general information (e.g., year of construction, building envelope composition) and utilized advanced instrumentation to rigorously assess thermal performance.

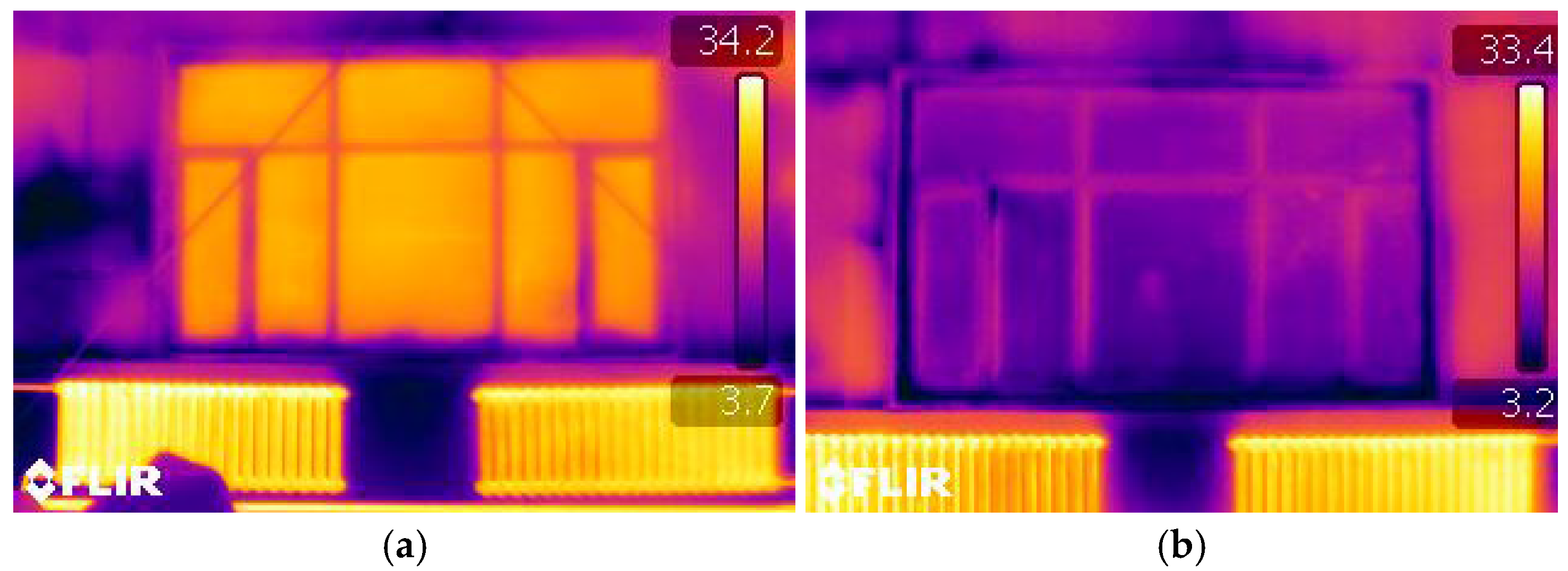

Thermal diagnostic imaging of the building envelopes was performed using a FLIR T560 professional handheld infrared camera (Teledyne FLIR, Wilsonville, OR, USA). The device features an uncooled microbolometer detector with a resolution of 640 × 480 pixels and a spectral range of 7.5–14 µm. To ensure the clarity of thermal patterns, it offers a high thermal sensitivity (NETD) of <40 mK at 30 °C, with measurement accuracy maintained at ±2 °C or ±2% through emissivity correction (0.01–1.0). Simultaneously, indoor environmental data were acquired using Blue Tag TH20 precision temperature and humidity data loggers (Freshliance Electronics Co., Ltd., Zhengzhou, China). These sensors operate within a wide temperature range of −30 °C to +60 °C with an accuracy of ±0.5 °C (Full Scale) and a memory capacity of 65,000 readings, ensuring continuous and stable data recording for establishing baseline thermal conditions.

Based on preliminary analysis and literature review [37], the data collection focused on three baseline architectural parameters identified as having the most critical impact on the performance of the window insulation system. The window structure determines the baseline heat transfer performance of the existing window unit [38,39,40,41] and serves as the fundamental basis for evaluating the effectiveness of any added insulation layer. Building orientation directly affects the optimal material selection and installation strategy for the window insulation system by determining the solar heat gain and heat loss for each facade [42]. Furthermore, the WWR [43,44] governs the distribution of heat flux between the windows and the walls. At high WWRs, the negative impact of thermal bridges from window frames can become prominent, potentially making the addition of an insulation layer a less effective strategy than a full high-performance window replacement.

2.1.2. Analysis of Building Characteristics

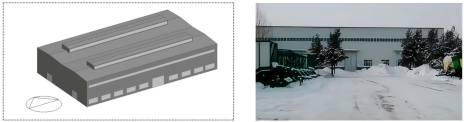

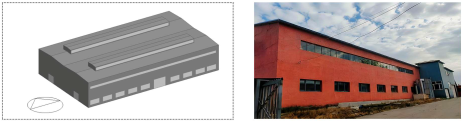

Industrial buildings in the surveyed regions are typically single-story, steel-framed structures utilizing either single-span or multi-span systems (Figure 1). They feature a rectangular floor plan (aspect ratio 1.5–8.0), an area exceeding 2000 m2, and a clear height over 10 m. Radiators were identified as the primary heating method. Indoor occupant activities primarily involve medium-intensity manual labor, and significant indoor heat gains are generated by heavy machinery (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Photos of some surveyed industrial buildings: (a) Multi-span industrial building; (b) Single-span industrial building.

Figure 2.

Main heat sources and personnel activity in industrial buildings: (a) Main heat-generating equipment; (b) The work intensity of the workers.

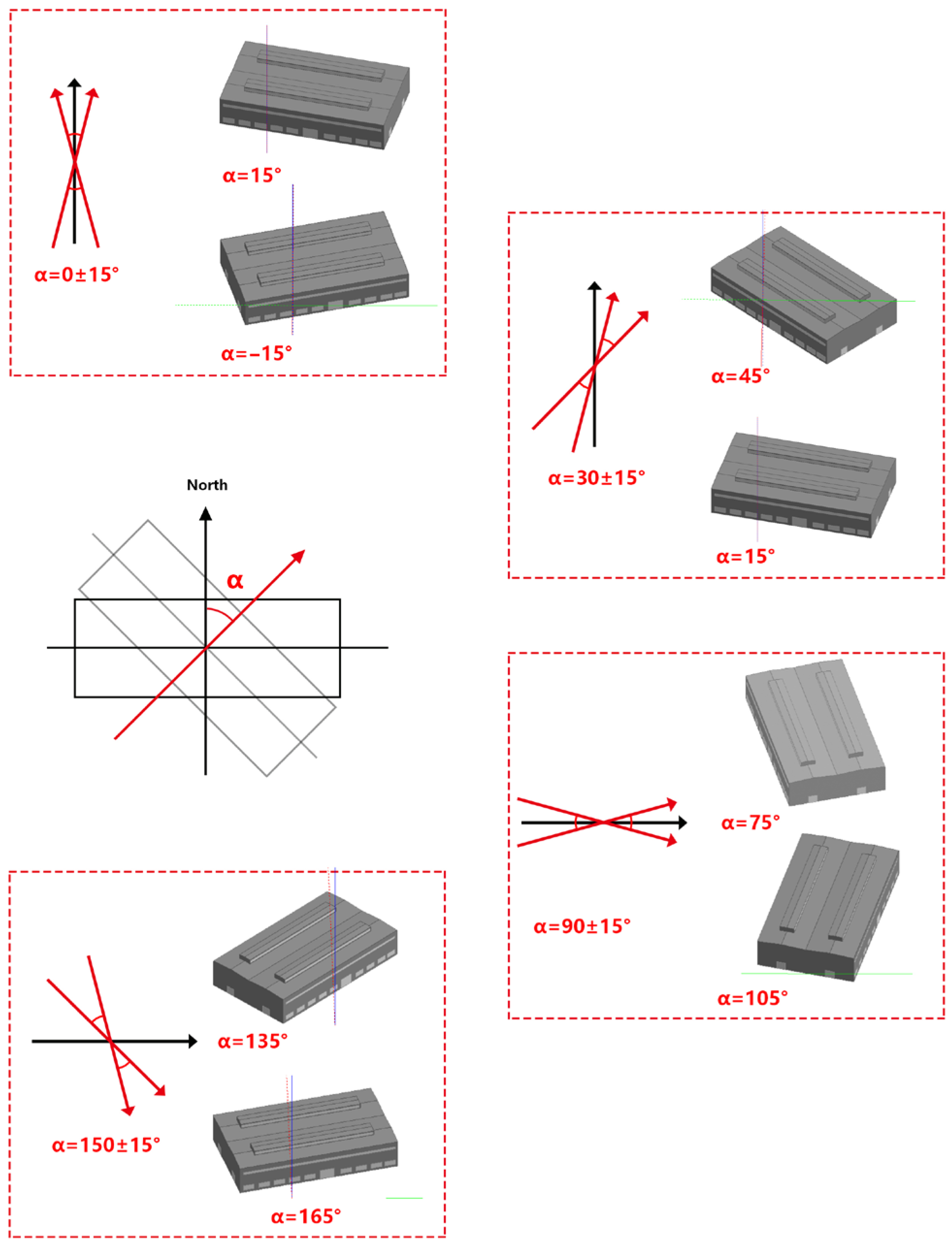

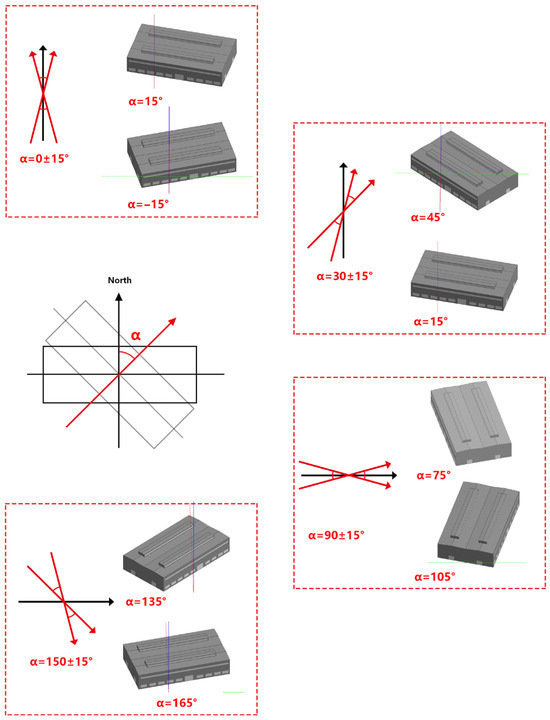

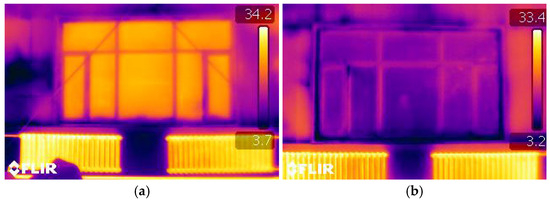

The survey quantified the key architectural parameters that served as the basis for the subsequent clustering analysis. Regarding window structure, three primary types were identified: single-glazed uPVC windows with high solar transmittance but poor insulation; double-glazed thermally broken aluminum windows offering excellent performance at a high cost; and double-glazed uPVC windows as a cost-effective, high-performance option. Regarding building orientation, this study defines the angle “α” as the clockwise rotation from true north (0°), as shown in Figure 3. Based on this, buildings were classified into four categories with a ±15° tolerance. The survey results indicate that a near north–south alignment was most common (>50%). Due to the low winter solar altitude angle in the high-latitude regions of Northeast China, north–south facing windows have a superior capacity for receiving solar radiation, leading to lower heating energy consumption and the best indoor thermal comfort (Table 1). Regarding WWR, the value was determined to be generally between 0.2 and 0.4. Clerestory windows were typically continuous ribbon or discontinuous rectangular windows for ventilation, while larger low-level windows were used for daylighting. Thermal imaging analysis revealed that single window pane areas can reach 10–15 m2, and these areas exhibit significant heat loss compared to the surrounding envelope, even during the day with ample solar radiation (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Orientation diagram.

Table 1.

Window orientation and thermal environment parameters.

Figure 4.

Infrared thermograph of windows: (a) South-facing window; (b) North-facing window.

2.1.3. Establishment of Six Typical Prototypes

A matrix table was constructed based on the preprocessed dataset. This table details the primary thermal characteristics of the surveyed buildings, including key window parameters (Table 2) and envelope compositions such as exterior wall and roof types (Table 3). A frequency analysis of this data was then performed to extract the representative construction parameters of the industrial buildings. Focusing on the thermal performance optimization of window, this study holds other building envelope parameters constant and selects three key variables for analysis: window structure, WWR, and building orientation. These variables were then cross-classified using a feature clustering method to identify six typical combinations (Table 4). Consistent with the definition in Section 2.1.1, “Orientation” refers to the clockwise rotation angle from true north (0°), as illustrated in Figure 3.

Table 2.

Frequency statistics of architectural characteristics for the surveyed industrial buildings.

Table 3.

Frequency statistics of construction characteristics for the surveyed industrial buildings.

Table 4.

The six building prototypes and their parameters.

The six resulting prototypes reflect the prevalent design logic in the region’s industrial buildings. For instance, prototypes with double-glazed uPVC windows accommodate a higher WWR and greater orientation flexibility due to their excellent thermal performance. In contrast, prototypes with single-glazed uPVC windows are typically oriented towards north–south to maximize solar compensation for their higher heat loss, with WWRs generally limited to below 0.3. Similarly, prototypes with high-performance but costly thermally broken aluminum windows are typically designed with a lower WWR to manage overall construction and operational costs. This rationale confirms the validity of the selected prototypes as representative cases for this study.

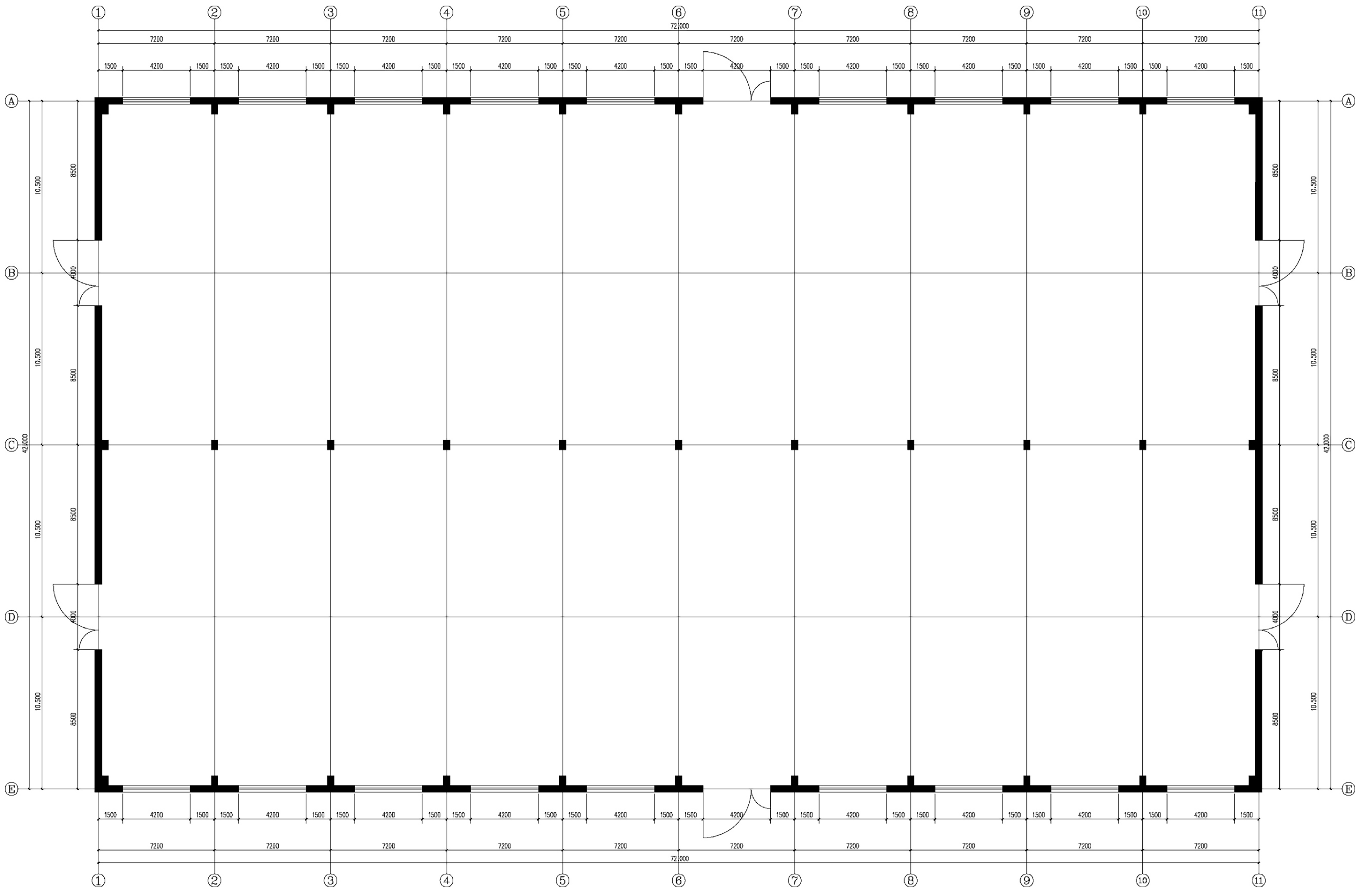

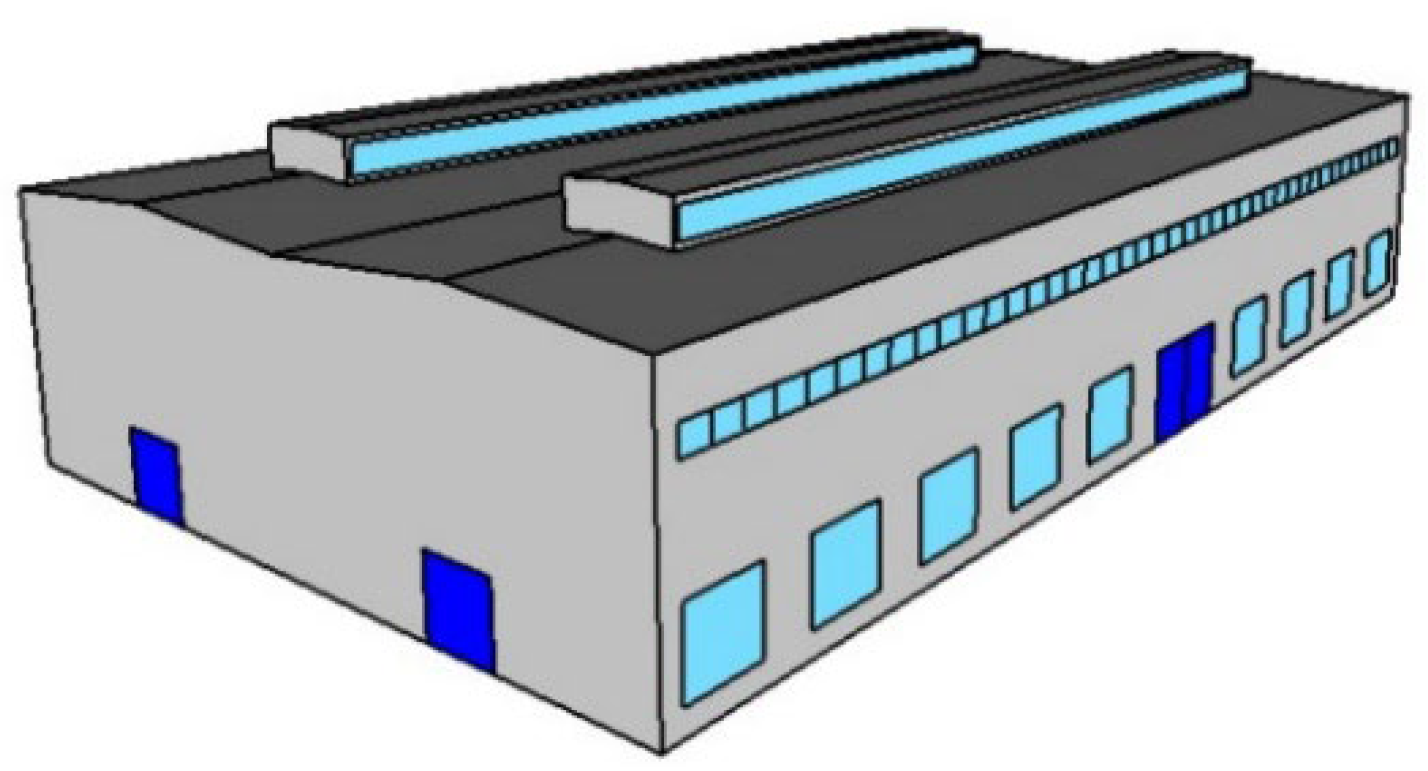

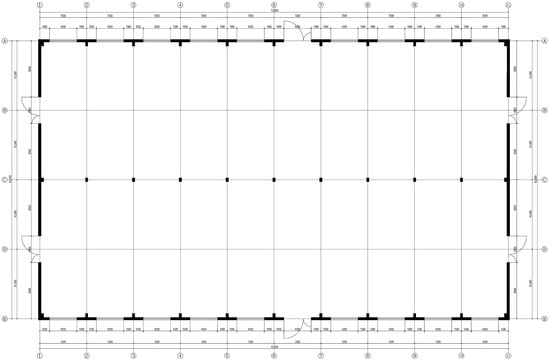

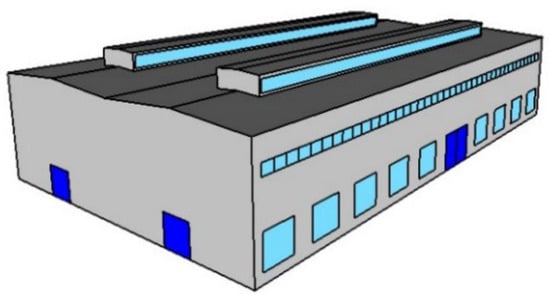

2.2. Baseline Simulation Model and Parameters

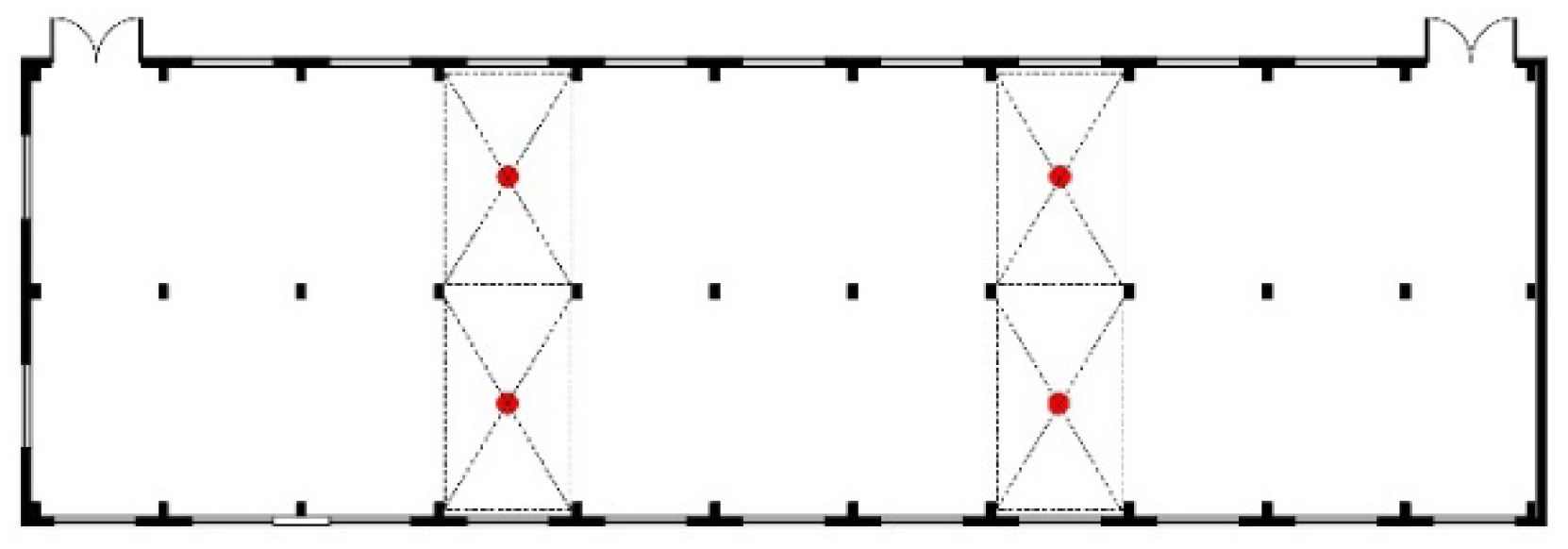

Based on the survey analysis, a representative single-story, double-span industrial building was selected to serve as the baseline simulation model. The building is located in Harbin, China, with a gross floor area of 3024 m2. Its floor plan and main exterior information are shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6, with each window measuring 4.2 m (width) by 3.2 m (height). The building envelope components and their thermophysical performance indicators are derived from a survey of the most common construction types in the region, as detailed in Table 5.

Figure 5.

Industrial building floor plan.

Figure 6.

Baseline model of an industrial building.

Table 5.

Construction and U-values of the main building envelope components.

For the occupants, the activity level was defined as “moderate intensity manual labor” (Grade II) in accordance with the “Unified standard for energy efficiency design of industrial buildings (GB51245-2017 [45])”. To quantify this, the Labor Intensity Index (I) was calculated based on the Measurement of Physical Factors in Workplace (GBZ/T 189.10 [46]) using Equation (1):

where

I = 10·Rt·M·S·W

I: Labor Intensity Index;

Rt: Working time ratio (%), set to 66.7% based on a typical 9-h shift with 6 h of net labor;

M: Average energy metabolic rate per working day (kJ/min·m2), set to 6.98;

S: Gender coefficient (Male = 1, Female = 1.3), set to 1 (Male);

W: Physical labor mode coefficient (Carrying = 1, Carrying on shoulder = 0.40, Pushing/Pulling = 0.05), set to 0.40 (Carrying).

Substituting these values yields I = 18.62, which falls within the range for Grade II intensity (15 < I ≤ 20). This corresponds to an energy metabolic rate of approximately 116 W/m2 (equivalent to 2.0 met). Consequently, assuming a standard body surface area of 1.8 m2, the specific heat gain per occupant in the DesignBuilder (Version 6.1.0.006) simulation was configured as 209 W/person. This setting accurately represents typical industrial activities such as machine operation and intermittent material handling. The occupant density was set to 10 m2/person. The clothing insulation was set to 1.4 clo in accordance with the “Evaluation Standard for Indoor Thermal and Humid Environment in Civil Buildings” (GB/T 50785-2012 [47]).

Based on the data recorded during the field survey, the equipment heat gain density was 10 W/m2 during operation. The indoor temperature setpoints were defined according to the operational requirements of typical heated workshops, with a daytime temperature of no less than 14 °C and a nighttime temperature of no less than 5 °C. Ventilation was set according to the Unified standard for energy efficiency design of industrial buildings (GB 51245-2017), with a minimum fresh air rate of 30 m3/(h·person). Considering the prolonged heating demands characteristic of the severe cold regions in Northeast China, the heating season was defined from 15 October to 15 April. The facility operates on a standard 5-day schedule, running from Monday to Friday, with Saturdays and Sundays designated as non-working days.

2.3. Simulation Scenario Design

2.3.1. Analysis of Influencing Factors

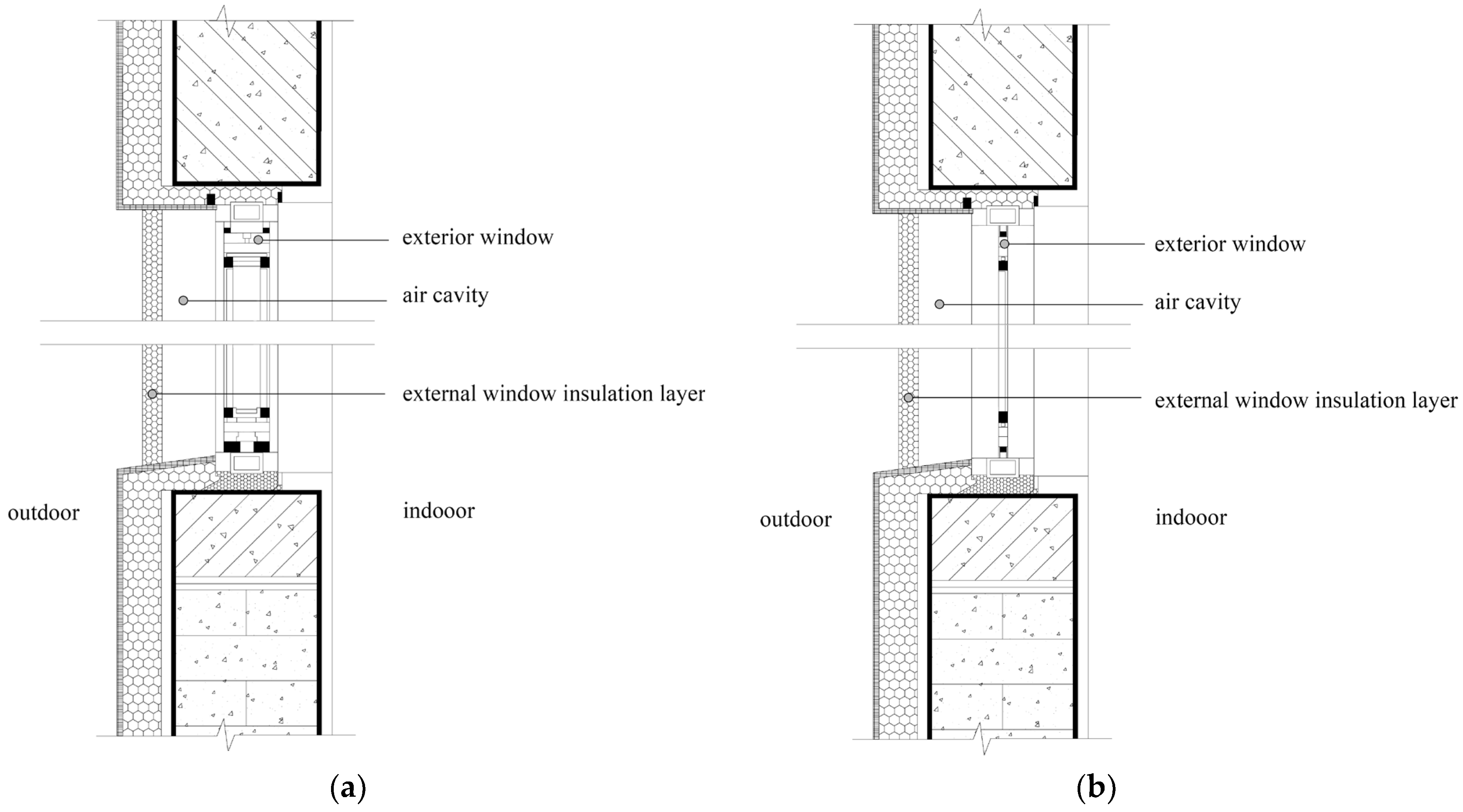

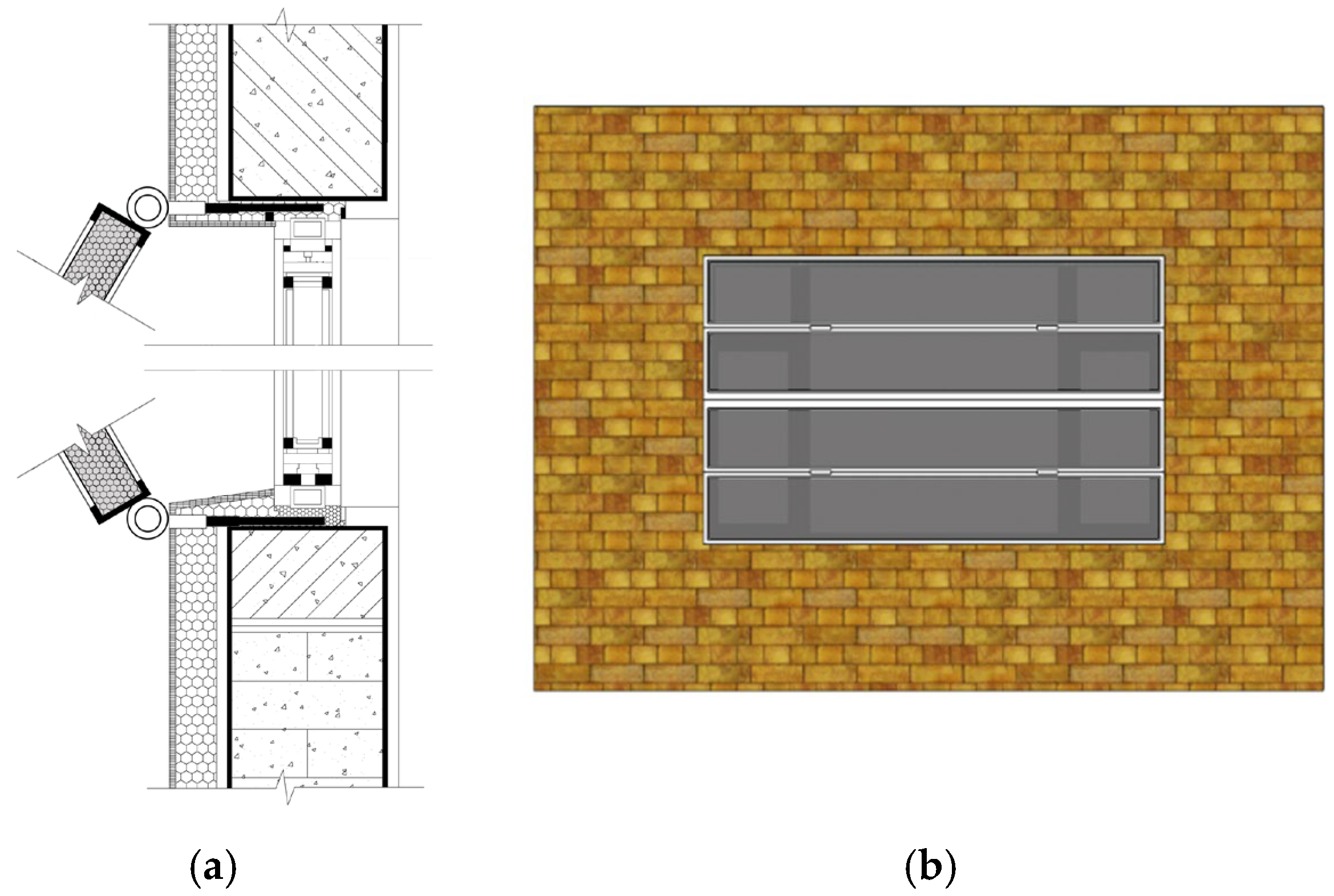

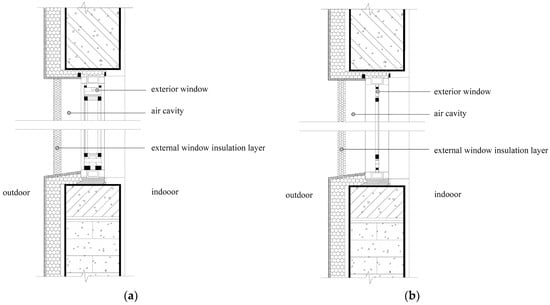

The window insulation system consists of the existing window, an insulation layer, and the air cavity between them (Figure 7). Existing research shows that adding an insulation layer effectively reduces heating loads and increases indoor temperatures while improving thermal comfort by creating more uniform temperatures near the window [48]. In the context of building retrofits, the existing window is considered a fixed condition, meaning the energy-saving performance is primarily governed by the variable parameters of the insulation layer and the air cavity. Therefore, this study systematically analyzes the key mechanisms of these two components from two primary aspects: insulation material selection and installation method.

Figure 7.

Sectional view of the window insulation system: (a) double-glazed window; (b) single-glazed window.

Regarding insulation material selection, the thermal performance of the window insulation system is primarily governed by thermal resistance and surface emissivity. Recent research shows that the layer’s thermal transmittance and surface emissivity are the two most critical performance factors, which can be controlled via the material’s thickness and structure. Materials with low thermal conductivity should be prioritized to reduce conductive heat loss. Moderately increasing the thickness enhances the system’s total thermal resistance by lengthening the heat transfer path and adding interfacial thermal resistance. However, the rate of increase in thermal resistance diminishes as the thickness continues to grow. Furthermore, the surface emissivity of the window insulation layer is influenced by factors such as material surface roughness and surface coatings. Applying a low-emissivity coating is an effective strategy to significantly suppress heat loss at night.

Regarding the installation method, the air cavity is a critical component for thermal resistance and its performance is influenced by multiple parameters. Increasing the cavity’s thickness enhances insulation but only up to a certain threshold where natural convection begins to counteract the gains. Airtightness ensures stable heat flux while the insulation’s operation mode affects potential leakage points [49,50]. The layer’s placement also creates different energy-saving effects because an exterior installation is exposed to a larger temperature gradient while an interior one directly contacts the indoor environment [51].

Based on the principles described above, this study systematically analyzes the six corresponding secondary indicators for the two primary factors of material selection and installation method: (a) insulation material type, (b) insulation layer thickness, (c) surface emissivity, (d) insulation layer position, (e) air cavity thickness, and (f) adjustment method.

2.3.2. Scenarios Based on Insulation Layer Parameters

The energy-saving mechanisms of a window insulation layer are primarily divided into two categories. The first category is transparent insulation materials, which have low thermal resistance and function primarily by creating a sealed air cavity with the window to provide the system’s overall thermal resistance. The second category is opaque materials, which have low thermal conductivity and achieve insulation by suppressing heat conduction.

To evaluate these two distinct strategies, a series of simulation scenarios were designed. For transparent materials, considering that the thickness variation of this material type is limited and its inherent transparency makes the application of surface coatings impractical, only the material type was considered as a variable. Therefore, only the material type was considered as a variable. A 0.3 mm-thick PVC insulating film was selected as the representative material.

For the opaque insulation materials, three common insulation boards (EPS, XPS, and PUR) were selected to represent different ranges of thermal performance. To ensure practical durability and weather resistance for outdoor applications, the insulation materials were modeled with protective facings. Two distinct types of surface finishes were defined to evaluate the impact of emissivity: (1) Reinforced Aluminum Foil (low-emissivity surface, ε = 0.05); (2) Waterproof Canvas (high-emissivity surface, ε = 0.92). The insulation layer’s thickness was varied from 10 to 50 mm in 10 mm increments. In all simulations, the air cavity thickness was set to 20 mm, and good airtightness was assumed. The specific parameters for each simulation scenario are detailed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Configuration of parameters for the insulation layer in simulation scenarios.

2.3.3. Scenarios Based on Air Cavity Parameters

Based on the differences in the energy-saving principles of transparent insulating film and opaque insulation boards, as discussed in Section 2.3.2, this study selected a PVC insulating film (thermal conductivity 0.15 W/(m·K), thickness 0.3 mm) as the research object to more clearly reflect the dominant role of the air cavity in the system’s energy savings. On this basis, this study systematically analyzed the impact of three key variables. The first variable is the placement of the insulation film, fixed on either the interior or exterior side of the window for the entire duration. The second is the thickness of the air cavity, set from 10 mm to 80 mm in 10 mm increments based on a field survey. The third variable is the airtightness of the system. To simulate air leakage from gaps that occur in practical applications due to needs like ventilation and maintenance, the study defined two sliding structures: horizontal and vertical (as shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9). To quantify their impact, three levels of gap width were simulated: 0 mm (ideal airtightness), 5 mm, and 10 mm. The simulation considered top and bottom leakage for the horizontal structure, and left and right leakage for the vertical structure. Detailed parameter settings are shown in Table 7.

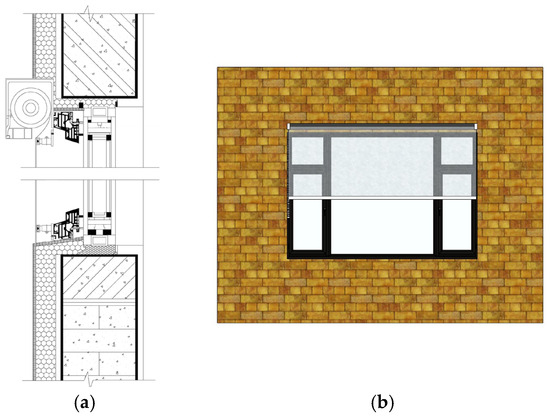

Figure 8.

Horizontal sliding insulation layer.

Figure 9.

Vertical sliding insulation layer.

Table 7.

Configuration of parameters for the air cavity in simulation scenarios.

2.4. Dynamic Simulation

2.4.1. Selection of Simulation Tool

The dynamic simulations in this study were conducted using DesignBuilder (Version 6.1.0.006), a comprehensive graphical interface for the EnergyPlus simulation engine (developed by the U.S. DOE). Unlike simplified steady-state calculation methods, EnergyPlus utilizes the rigorous Heat Balance Method (HBM). This algorithm strictly enforces the first law of thermodynamics on the zone air and all opaque and transparent surfaces at each time step. The core governing equation for the zone heat balance is expressed as Equation (2):

where

: Rate of energy storage in zone air;

: Sum of internal convective loads;

: Convective heat transfer from zone surfaces;

: Heat transfer due to inter-zone air mixing;

: Heat transfer due to infiltration;

: Convective heat transfer from HVAC systems.

This study employed the software to dynamically calculate the building’s heating load and detailed window heat gains and losses under various insulation system configurations [52].

The window insulation system was modeled using DesignBuilder’s “Window Shading” module. Transparent PVC film was defined as “Transparent Insulation,” and opaque materials like EPS, XPS, and PUR were set as “Diffusing Shades.” The opening and closing strategy for the insulation layer and the air cavity parameters were configured in detail under “Openings” within the “Shade Data” module. The model’s initialization period is set via “Interval,” which was set to “Running Period” to simulate the heating season. For dynamic analysis of a typical day, the time step was set to “Hourly” to meet the needs of hour-by-hour data analysis.

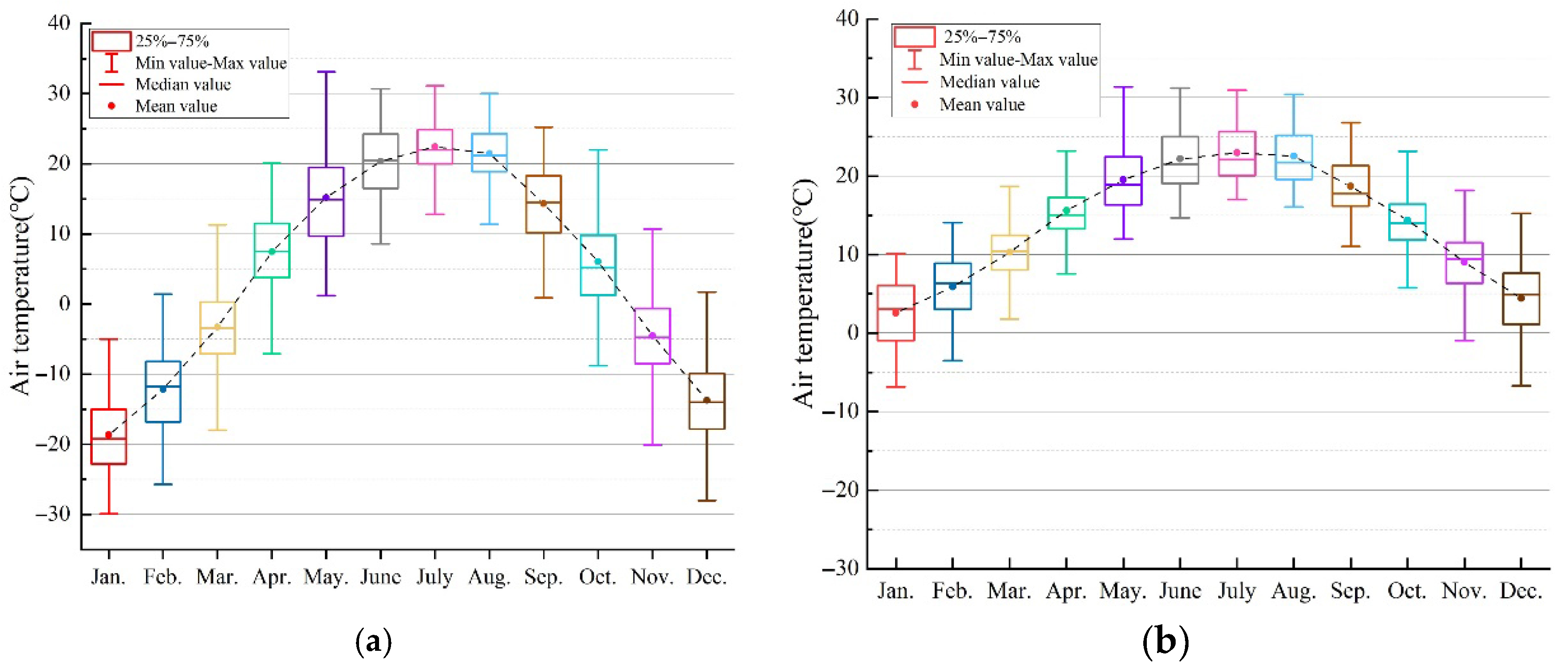

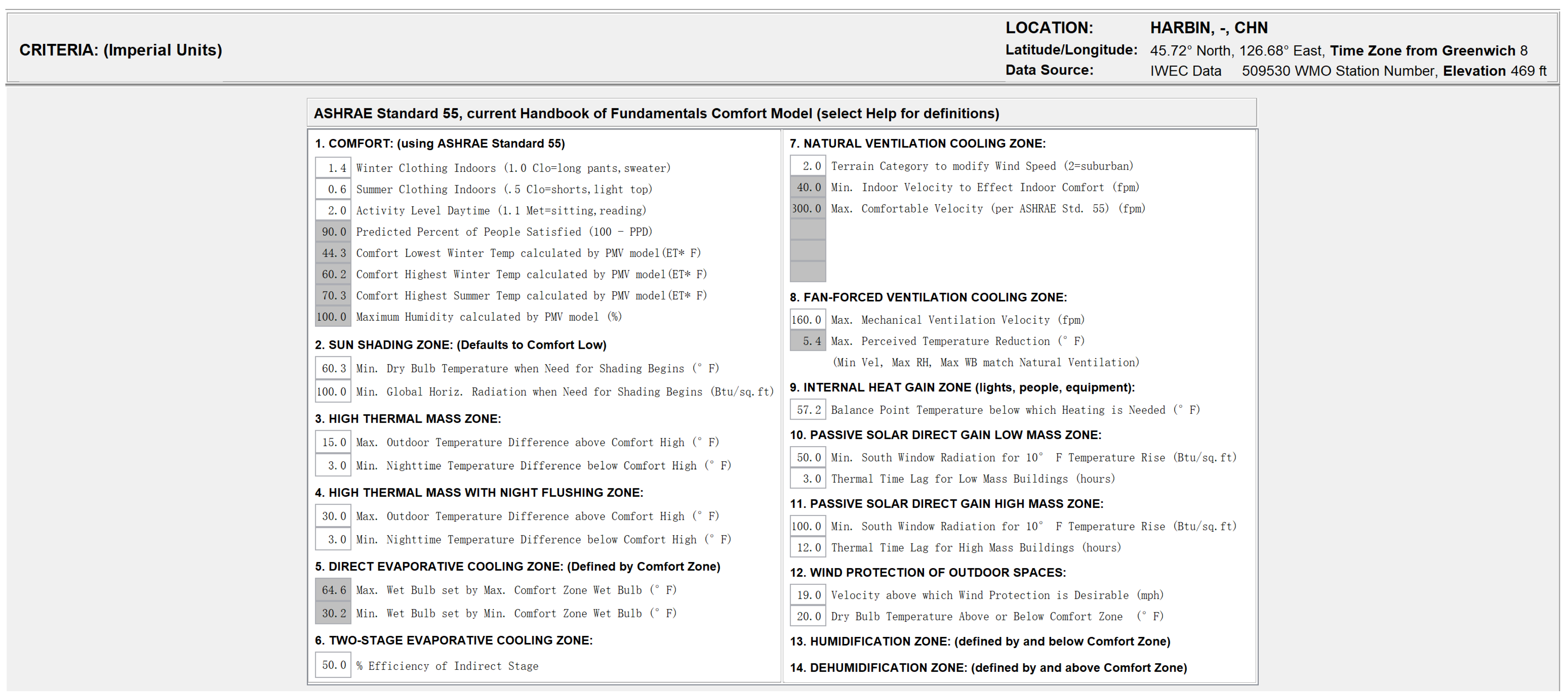

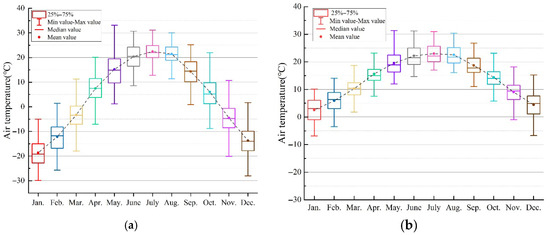

2.4.2. Climatic Data and Boundary Conditions

Simulation meteorological conditions were based on China Standard Weather Data (CSWD) for Harbin. Figure 10a illustrates the annual hourly distribution of outdoor air temperature. Analysis shows that summer temperatures generally remain below 26 °C, while winter minimums approach −20 °C. This climatic profile directly impacts the building’s energy performance. To ensure applicability to the specific industrial context, the simulation input criteria were first adjusted based on actual operating conditions. As detailed in Figure 11 and Figure 12, the metabolic rate was set to 2.0 met (representing medium industrial labor intensity), and winter clothing insulation was set to 1.4 clo. Based on these parameters and the PMV (Predicted Mean Vote) model defined in ASHRAE Standard 55 [53] (Current Handbook of Fundamentals), the thermal comfort boundaries were mathematically calculated. Subsequently, the annual psychrometric chart was generated using Climate Consultant 6.0, as presented in Figure 13.

Figure 10.

Hourly air temperatures for a Typical Meteorological Year (TMY) in Harbin: (a) outdoor; (b) simulated indoor conditions.

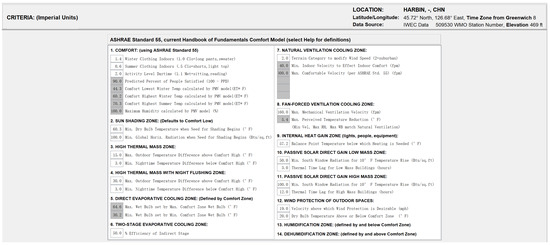

Figure 11.

Simulation criteria and input parameters.

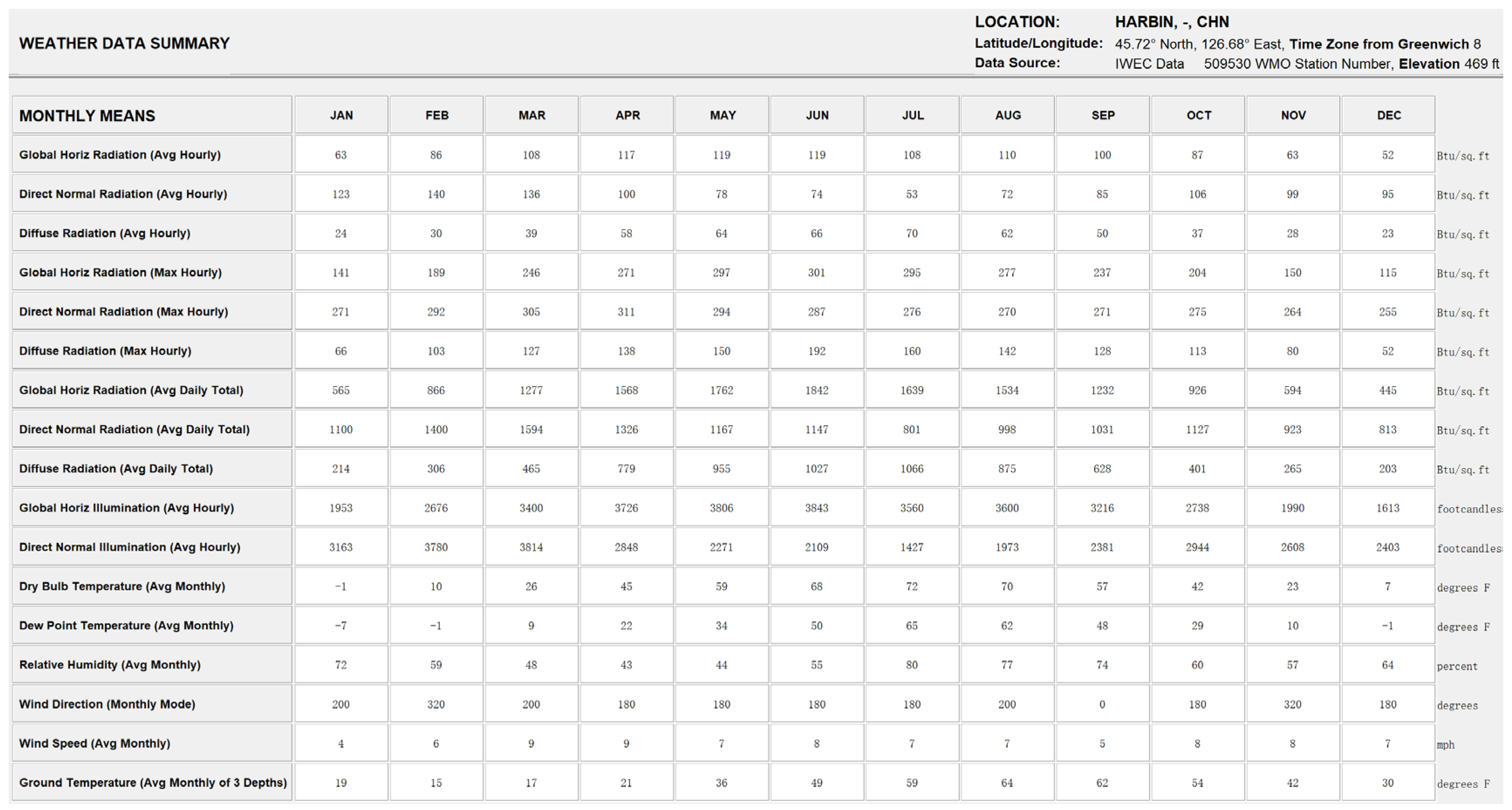

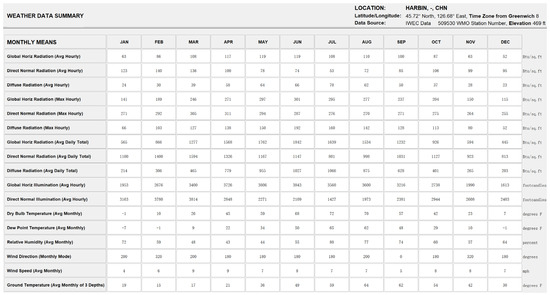

Figure 12.

Weather data summary for Harbin.

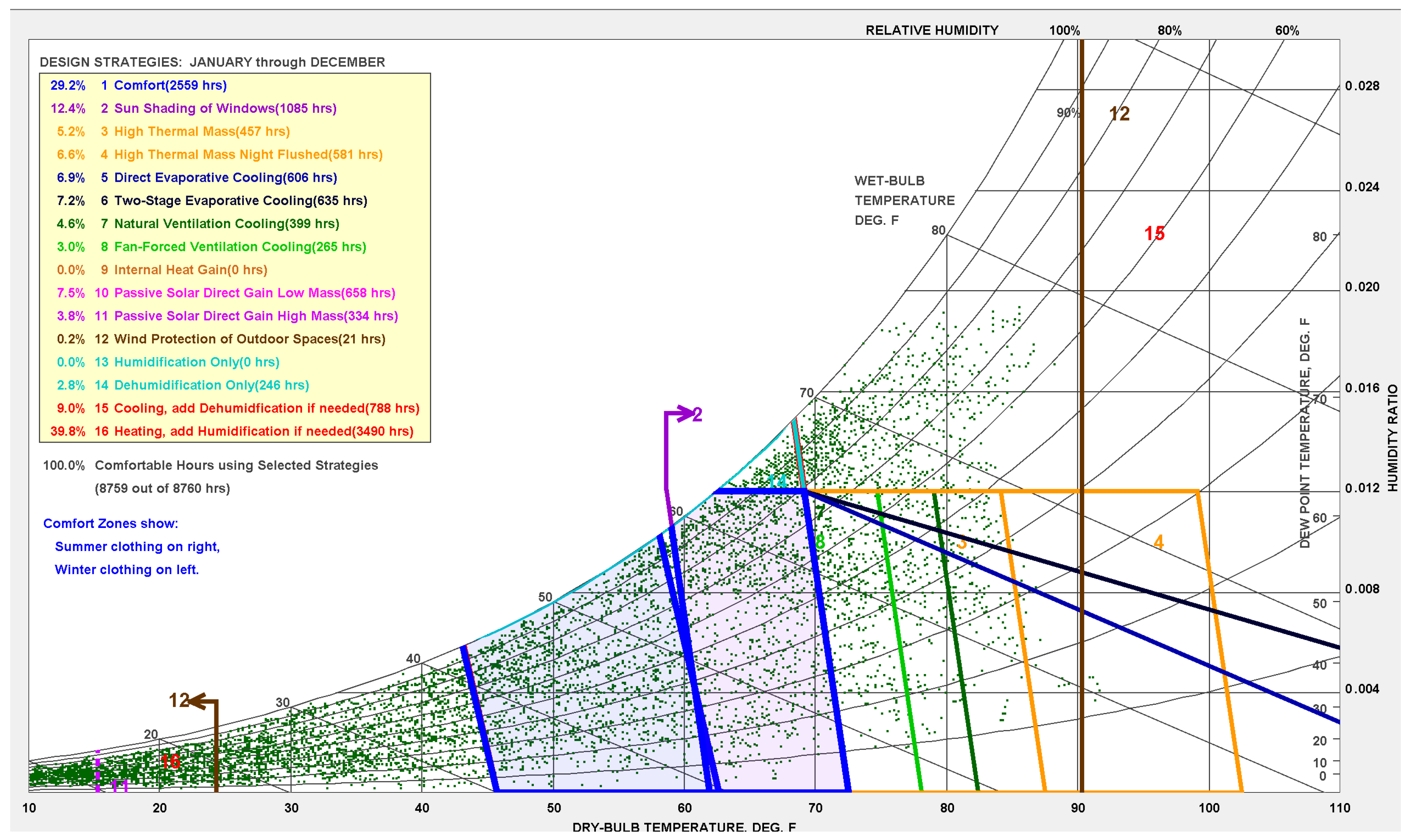

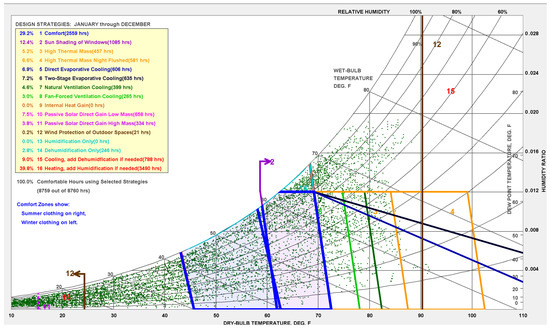

Figure 13.

The annual psychrometric Chart for Harbin defined by ASHRAE Standard 55-2023 [53].

The results reveal the unique thermal characteristics of this industrial facility and highlight the potential for passive operation. Without any mechanical intervention, the building falls naturally within the occupant thermal comfort zone for 29.2% of the year. Furthermore, direct passive solar gain (combining low and high thermal mass effects) provides comfort for approximately 11.3% of the time, effectively alleviating part of the heating pressure.

After accounting for these passive comfort periods, the period requiring active heating constitutes 39.8% of the year. Due to significant internal industrial heat gains and the lower heating setpoint (14 °C), this proportion is indeed lower than that of typical office buildings in severe cold regions. However, heating remains the absolute dominant energy challenge for this facility. This 39.8% demand is concentrated during extreme weather conditions (with temperatures as low as −20 °C), where the massive indoor-outdoor temperature difference (exceeding 30 °C) results in extremely high energy intensity loads. The analysis suggests that while internal industrial loads provide a valuable thermal buffer, the existing building envelope fails to effectively retain this heat. Consequently, despite the moderating effect of the building envelope, the average indoor temperature from November to March remains below 14 °C (Figure 10b). Therefore, retrofit strategies must focus on high-performance insulation to effectively preserve internal heat gains, thereby addressing the facility’s primary winter heating energy burden.

2.4.3. Baseline Model Validation

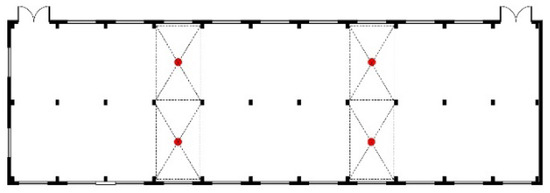

To rigorously validate the accuracy of the baseline model established in this paper, on-site indoor temperature measurements were conducted in a typical industrial building in Pingfang District, Harbin, in January 2025. During the measurement period, the outdoor temperature ranged from −13 °C to 4 °C, with a relative humidity of 61%. Unlike the complex spatial partitioning of residential buildings, the industrial workshop features a high-ceilinged, open-plan layout with a relatively uniform thermal distribution. To ensure data representativeness and minimize the interference of cold drafts caused by frequent door operations, four monitoring points were selected in the central working zone, away from the exterior envelope openings (Figure 14). The sensors were positioned at a height of 0.75 m above the floor, corresponding to the standard working plane. Data acquisition was performed using the Blue Tag TH20 data loggers (Freshliance Electronics Co., Ltd., Zhengzhou, China) described in Section 2.1.1. The device collected data at a 60-min frequency to align with the simulation time step. The arithmetic mean of the four points at each time interval was calculated to generate the measured indoor temperature curve for validation.

Figure 14.

Layout of measurement points on floor plan of the industrial building for model validation.

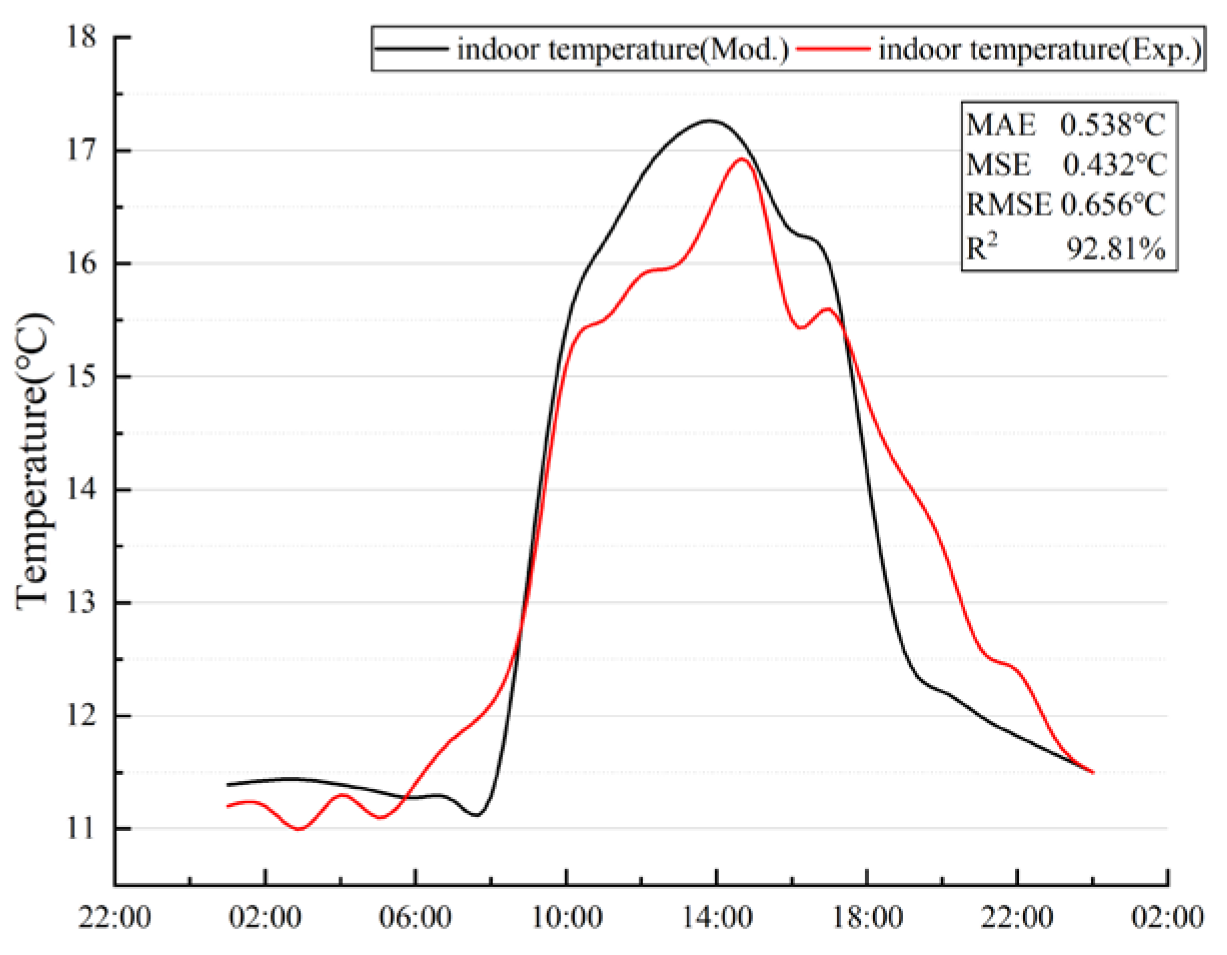

For the comparative analysis, a validation model identical to the measured building was constructed in DesignBuilder, using the meteorological parameters for Harbin from the specific measurement day to simulate the indoor temperature.

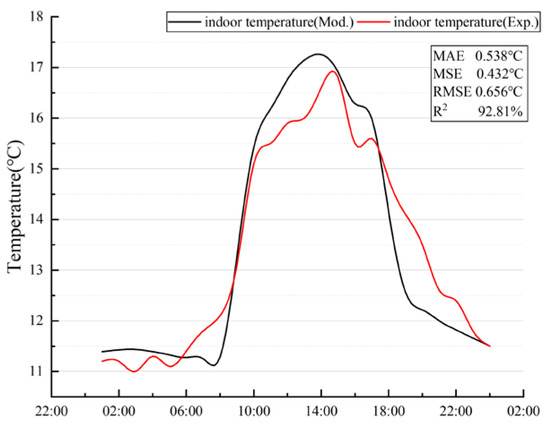

The comparison between the simulated results and the measured data is shown in Figure 15, revealing excellent agreement in both the trends and values. To quantitatively assess the model’s accuracy, we used the following performance measures commonly used in model evaluation: mean absolute error (MAE), root mean squared error (RMSE), mean squared error (MSE), and coefficient of determination (R2). These metrics indicate that the model’s error is within an acceptable range and its accuracy is high.

Figure 15.

Comparison between numerical and experimental results on indoor temperature of test room.

3. Results and Discussion

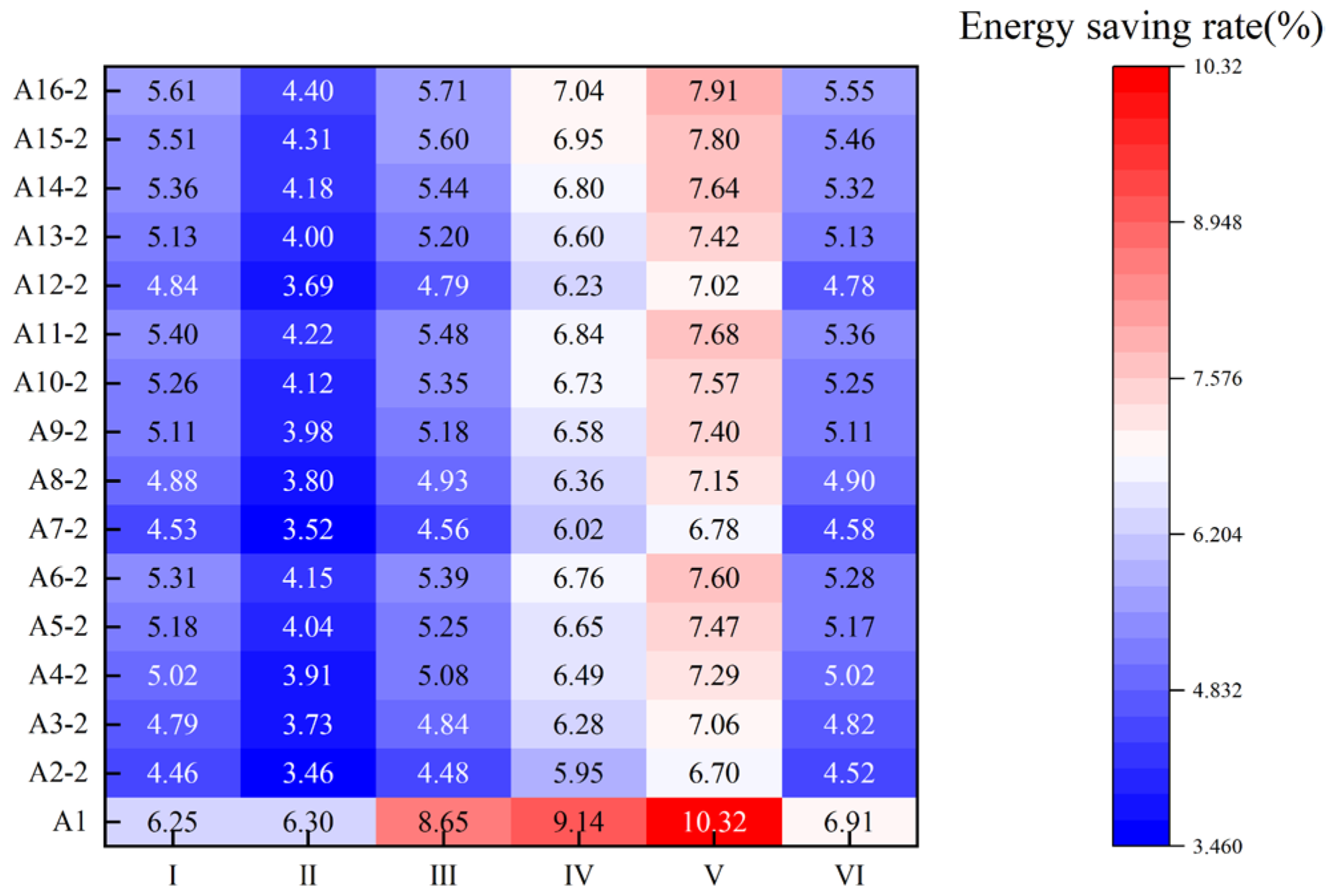

This section quantitatively evaluates the energy-saving performance and potential of the window insulation system. It first assesses the overall energy-saving effect using key metrics such as heating load and window heat loss. The analysis then examines the impact of two primary factors and their secondary indicators on system efficiency across the six prototypes. Finally, optimal energy-saving configurations for various conditions are identified through a comprehensive comparison of all scenarios.

3.1. Parameters of the Insulation Layer

From a material selection perspective, insulation materials are categorized as transparent or opaque based on their optical properties. Transparent PVC film insulates by creating a sealed air cavity and leveraging the greenhouse effect, thus admitting solar gain while reducing heat loss. In contrast, opaque boards like EPS and XPS rely on high thermal resistance to directly block heat transfer. Section 3.1.1 and Section 3.1.2 analyze the energy-saving mechanisms and performance of these two insulation types across the six building prototypes.

3.1.1. Transparent Insulation Materials

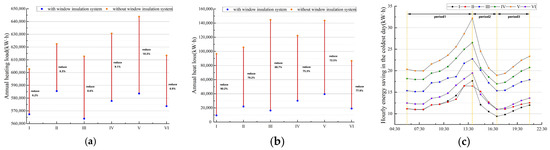

The application of a PVC insulating film demonstrates significant effects by both improving indoor thermal environment quality and reducing heat loss through windows. On the one hand, it effectively enhances the building’s overall insulation performance. This is particularly prominent in Prototype V, which had the poorest initial thermal performance. This prototype achieved the largest reduction in annual heating load (Figure 16a) with an energy-saving rate of 10.3%. Its hourly heating load on the coldest day also decreased substantially while attaining the largest increase in free-floating indoor temperature. This indicates that the energy-saving potential is most significant for windows with poor insulation. On the other hand, the film is also highly efficient at suppressing directional heat transfer. Prototype I provides an ideal validation case for evaluating this capability. North-facing windows receive almost no solar gain throughout the year, and their heat flow is dominated by continuous and stable unidirectional loss. The results show that the net heat loss reduction rate reached 90.2% (Figure 16b), demonstrating the outstanding capability of the PVC thermal film in suppressing directional heat dissipation.

Figure 16.

Thermal performance analysis: (a) a comparison of annual heating load; (b) a comparison of annual heat loss; (c) the hourly energy savings with the PVC insulating film.

The magnitude of the energy-saving benefits is also significantly influenced by the building’s inherent characteristics. For instance, although Prototype IV uses single glazing, its absolute energy-saving improvement is limited because its low WWR (0.20) results in a modest initial heating load. Although Prototype III has the highest WWR (0.40), its 150° orientation leads to unstable solar radiation utilization, thereby constraining the film’s energy-saving effectiveness. Because Prototypes II and VI have better baseline thermal performance, they show a relatively smaller improvement in energy savings after the film is applied, revealing the diminishing marginal returns of applying a PVC insulating film to high-performance envelopes.

An in-depth analysis of the hourly data from the coldest day reveals that the energy-saving effect of the PVC insulating film is not limited to nighttime but is a 24-h phenomenon, with a three-phase mechanism. Period 1 is the daytime heat storage period, during which intensifying solar radiation and the film’s greenhouse effect enhance the window system’s heat storage capacity, causing both the hourly energy savings (Figure 16c) and the indoor free-floating temperature (Figure 17a) to peak around 14:00 and raise the indoor temperature by approximately 1 °C. Period 2 is the evening heat release period, where from late afternoon until after sunset, both the energy savings and the free-floating temperature difference decrease but remain positive as the solar heat supply diminishes. Period 3 is the nighttime heat preservation period. From night until early morning, the indoor free-floating temperature can be up to 1.5 °C higher than the baseline, effectively reducing the overall daily indoor temperature range (Figure 17b) while the energy savings also rebound slightly. This clearly demonstrates that the PVC insulating film effectively suppresses nighttime heat loss through the windows without significantly compromising daytime solar heat gain, thereby improving the diurnal thermal balance and demonstrating high energy efficiency stability and application adaptability.

Figure 17.

Free-floating indoor temperature on the coldest day: (a) hourly; (b) daily.

In summary, the PVC insulating film should be prioritized as an envelope enhancement measure for industrial buildings with poor thermal performance of their windows (e.g., Prototypes V and I). Furthermore, considering the building’s hourly thermal load characteristics, major heat-producing equipment should be scheduled for daytime operation, fully utilizing the building’s thermal storage capacity to maintain indoor temperature at night. This approach reduces or avoids the need to activate conventional heating systems at night, thereby balancing energy-saving goals with indoor thermal comfort.

3.1.2. Opaque Insulation Materials

Because using an opaque insulation layer during the day would severely affect natural daylighting and negatively impact production activities, the analysis scenarios in this section assume it is applied to the exterior of the window only at night.

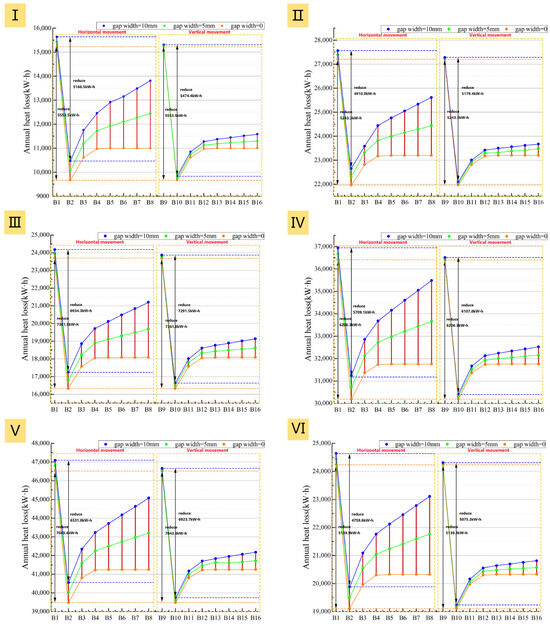

Thermal Performance Analysis

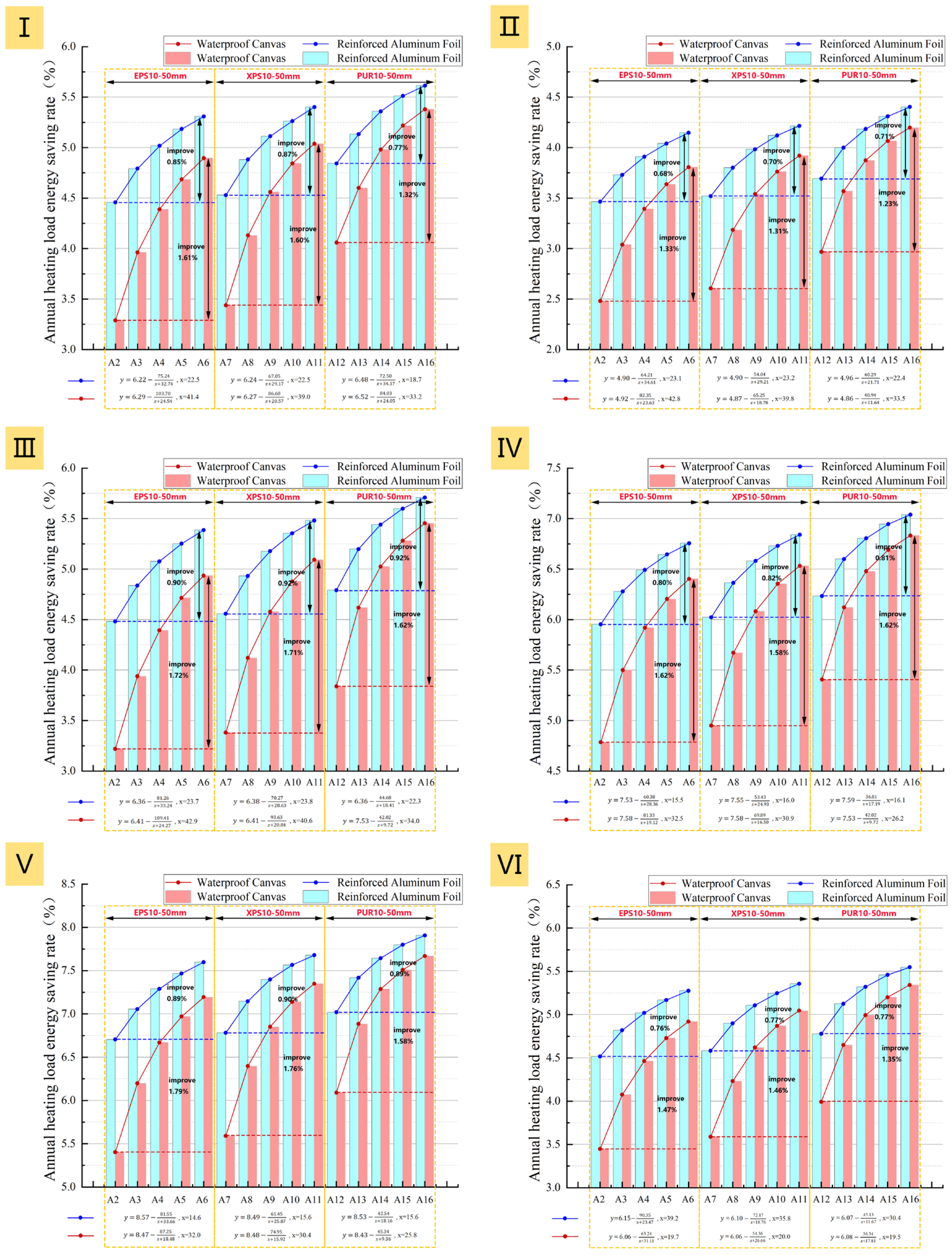

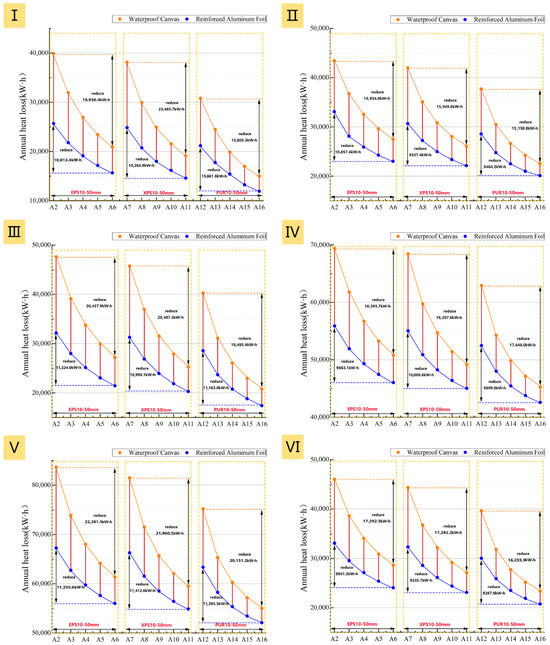

Figure 18 reveals how the material type, thickness, and surface emissivity of the opaque insulation layer jointly affect the energy-saving performance. Overall, applying an opaque insulation layer to windows at night can reduce the heating load (Figure 18), though the benefits vary significantly among different prototypes. For instance, the weakest performance was observed in Prototype II, which had an energy saving rate consistently below 4.5% and even underperformed Prototype IV with its single-glazed windows. This is mainly because Prototype II has a low WWR and an east–west orientation, leading to poor solar radiation utilization and thus limiting the insulation’s heat retention effect. This indicates that retrofitting with window insulation layer is not a priority for east-west oriented industrial buildings with small WWRs.

Figure 18.

Total annual heating load of the six prototypes at two different surface emissivities: (I): Prototype I; (II): Prototype II; (III): Prototype III; (IV): Prototype IV; (V): Prototype V; (VI): Prototype VI.

Furthermore, regardless of the insulation material or thickness, both the heating load and net heat loss decrease as surface emissivity is reduced. This indicates that by lowering the surface emissivity, the required thickness of the insulation material can be effectively reduced while achieving a similar thermal performance. For instance, in Prototype I, a 30 mm thick XPS board with a surface emissivity of 0.92 showed nearly identical heating load performance to a 10 mm thick XPS board with a surface emissivity of 0.05. This means a 0.75 reduction in surface emissivity can save approximately 20 mm in insulation thickness.

However, the energy savings generated by reducing surface emissivity are related to the thickness of the insulation layer. As the insulation layer becomes thicker, the impact of emissivity on the energy-saving effect diminishes. For both total heating load and net heat loss, the gap between the high- and low-emissivity curves narrows as insulation thickness increases (Figure 18 and Figure 19). Specifically, with a low surface emissivity (0.05), increasing the insulation thickness from 10 mm to 50 mm raises the average energy saving rate of the six prototypes by only 0.85%. In contrast, under high emissivity conditions (0.92), the same increase in thickness yields a 1.67% improvement (Figure 20). This indicates that once the low-emissivity coating effectively suppresses radiative heat transfer, adding thickness only improves performance by increasing conductive thermal resistance, and thus its contribution to energy savings diminishes. Therefore, this analysis reveals a non-cumulative effect between the two energy-saving measures, meaning the benefits from a low-emissivity surface and increased insulation thickness are not simply additive. The high effectiveness of the low-emissivity surface in suppressing radiative heat transfer significantly diminishes the additional performance gains achievable by subsequently increasing the insulation thickness.

Figure 19.

Net heat loss of the six prototypes at two different surface emissivities: (I): Prototype I; (II): Prototype II; (III): Prototype III; (IV): Prototype IV; (V): Prototype V; (VI): Prototype VI.

Figure 20.

Annual heating load energy saving rate and derived critical thickness for two emissivities: (I): Prototype I; (II): Prototype II; (III): Prototype III; (IV): Prototype IV; (V): Prototype V; (VI): Prototype VI.

Synthesizing the results from the total heating load (Figure 18), net heat loss (Figure 19), and energy saving rate (Figure 20), Prototypes III, IV, and V exhibit the most significant energy-saving performance after the application of an insulation layer, but their growth in energy saving rates with increasing thickness also demonstrates a trend of diminishing marginal returns. A further comparison of the different insulation materials reveals that while the material’s thermal conductivity determines its baseline insulation capability (PUR > XPS > EPS), differences in surface emissivity significantly alter their performance ranking. For the same increase in thickness, at a low surface emissivity of 0.05, XPS shows the largest increase in energy saving rate, followed by PUR and EPS. At a high surface emissivity of 0.92, however, the performance diverges: while EPS shows the fastest increase in its energy saving rate, PUR provides the best absolute effect at all thicknesses due to its lowest thermal conductivity.

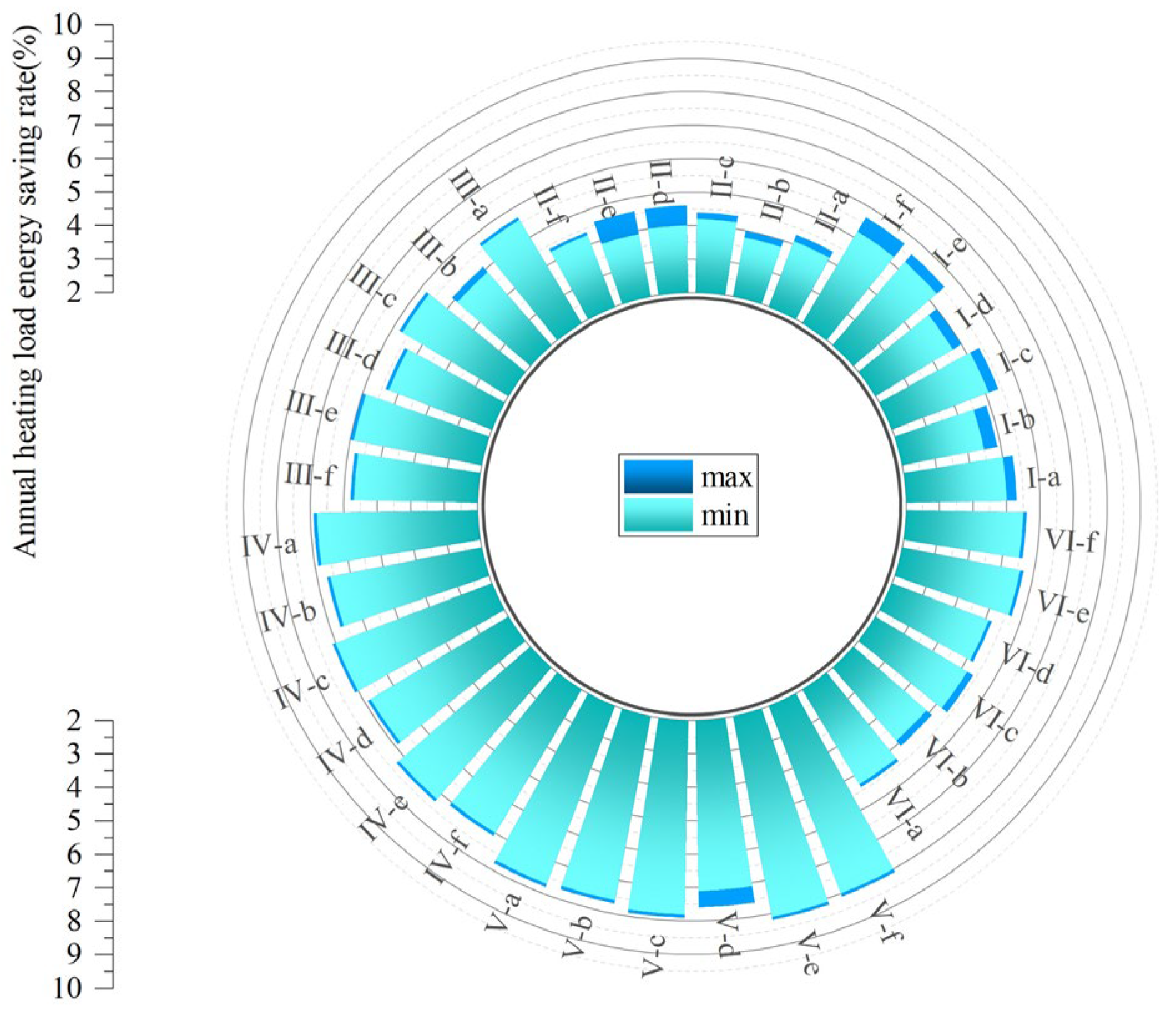

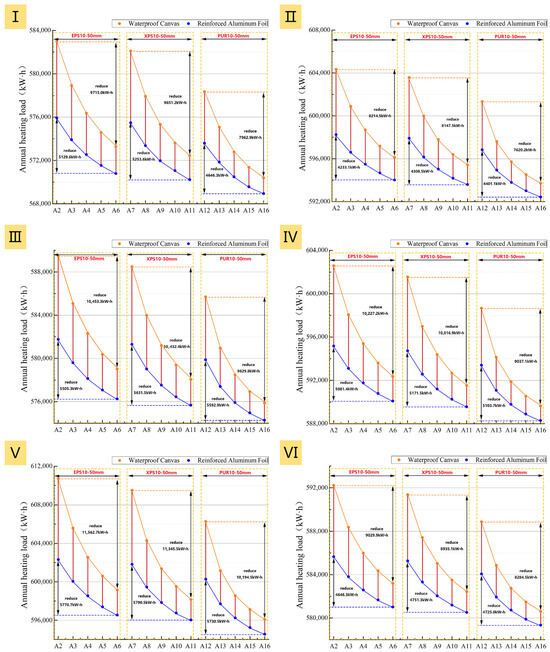

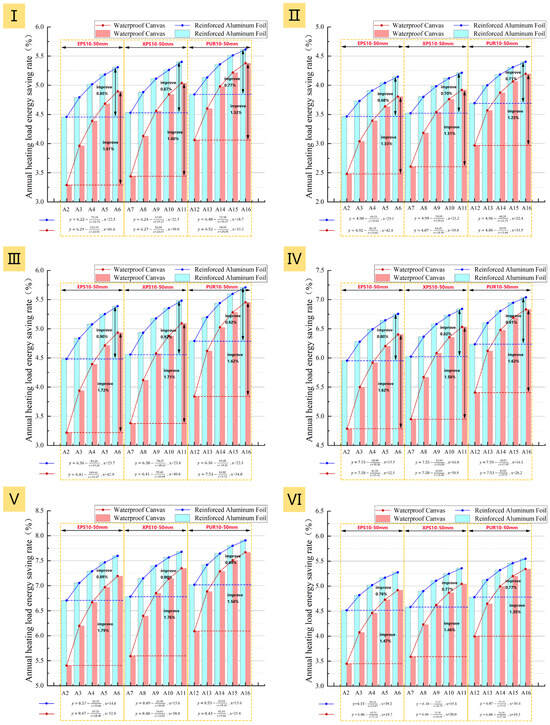

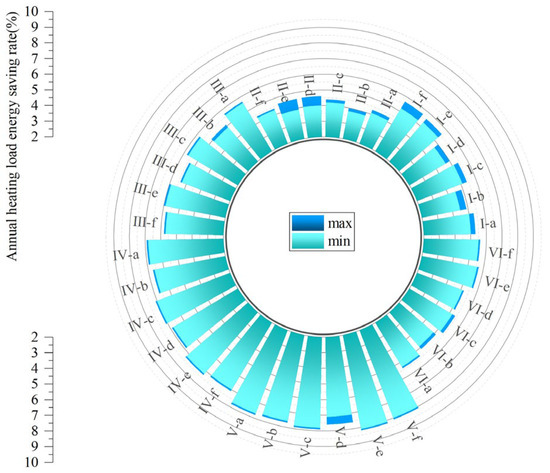

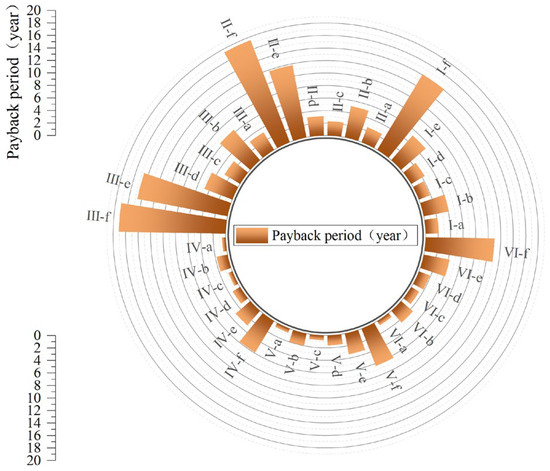

Techno-Economic Analysis and Optimization

In practical applications, the selection of an insulation layer must consider multiple factors, including material, installation, labor, and energy costs. To balance energy efficiency with economic viability, this study fits an Annual Heating Load Energy Saving Rate (y) versus Thickness (x) curve for each prototype. Using this model, the recommended insulation thickness range was determined by identifying the critical point beyond which the marginal growth in the energy saving rate slows significantly (<0.5%), providing a practical reference for material selection in engineering projects (Figure 20). Based on these ranges (Table 8), the solutions were evaluated using two key metrics: the Annual Heating Load Energy Saving Rate (Figure 21), which reflects thermal performance improvement, and the Static Payback Period (Figure 22), which gauges economic viability.

Table 8.

Optimal performance solution candidates for each building prototype.

Figure 21.

Techno-economic analysis of the proposed solutions: range of energy saving rate.

Figure 22.

Techno-economic analysis of the proposed solutions: payback period.

The comparative analysis reveals that while energy savings increase with thickness, economic feasibility is decisively optimized by the use of low-emissivity coatings. Options utilizing Reinforced Aluminum Foil (b, d, f) consistently demonstrate higher energy saving rates and significantly shorter payback periods compared to Waterproof Canvas options. Notably, Option b (EPS + Foil) and Option d (XPS + Foil) exhibit exceptional cost-effectiveness with payback periods ranging from 0.6–3.3 years, and even less than one year for Prototypes IV, V, and VI. Conversely, while PUR offers superior insulation, its high initial cost leads to prolonged return cycles (Option e), though this can be effectively mitigated by applying the aluminum foil coating (Option f).

Consequently, the material selection strategy should be tailored to the project’s primary goal. When prioritizing maximum economic benefit, EPS or XPS combined with Reinforced Aluminum Foil (Options b and d) are the premier choices, offering an optimal balance of performance and rapid capital turnover. For projects aiming for maximum energy performance, PUR combined with Reinforced Aluminum Foil (Option f) is recommended, particularly for Prototypes IV, V, and VI where the payback period remains reasonable. Ultimately, the integration of low-emissivity coatings proves to be a more cost-effective strategy than simply increasing insulation thickness or selecting premium materials alone, highlighting that combining affordable insulation boards with reflective surfaces is the most balanced pathway for widespread industrial building retrofits.

where

Pt: Static Payback Period (years), representing the time required to recover the investment;

CIt: Cash Inflow in year t (CNY), representing the annual heating energy cost savings;

COt: Cash Outflow in year t (CNY), representing the incremental investment cost of the window insulation system (occurring at t = 0).

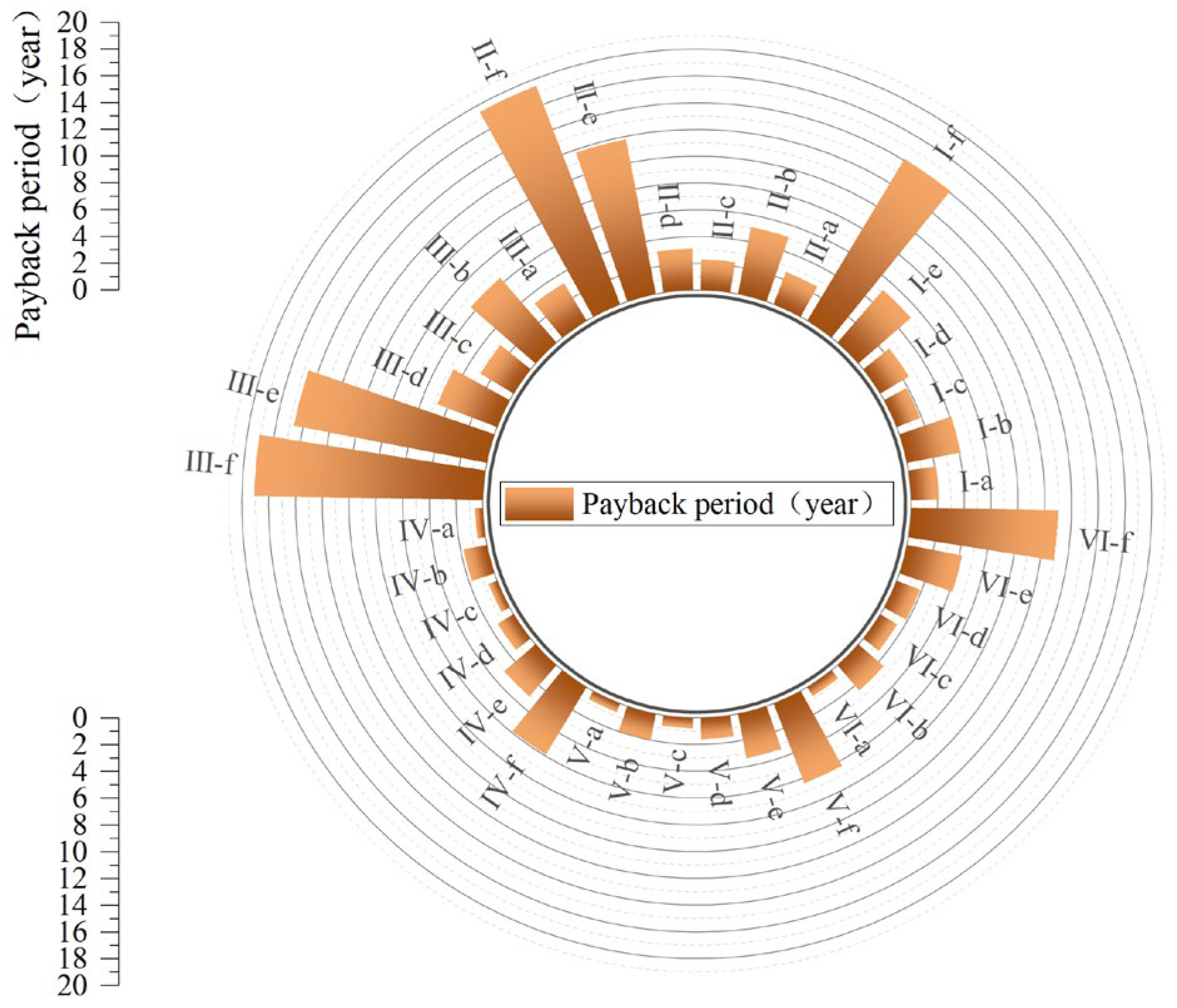

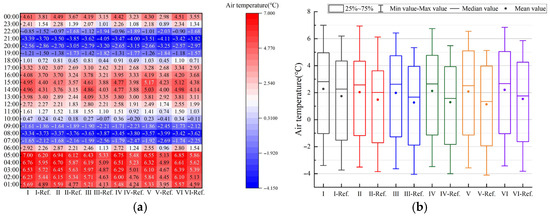

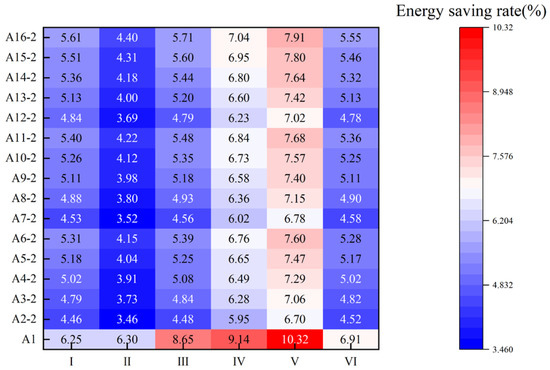

3.1.3. Selection Strategy for Window Insulation Layers

A comprehensive comparison of transparent and opaque insulation materials reveals a trade-off between energy savings and nighttime thermal stability. The data shows that although applying an opaque insulation layer at night (A2–A16) achieves a higher nighttime free-floating indoor temperature compared to the baseline scenario (Ref.), its total heating load is generally higher and its energy saving rate is lower than the full-time application of a PVC insulating film (A1). This holds true even when using materials with a surface emissivity as low as 0.05 (Figure 23). However, applying the method at night results in higher indoor temperatures and a smaller diurnal temperature difference (Figure 24).

Figure 23.

Energy saving rate during the heating season.

Figure 24.

Average free-floating indoor temperature during night non-working hours on the coldest day.

Therefore, the appropriate selection mechanism is determined by the primary project goal:

(1) For industrial buildings where prioritizing nighttime thermal environment quality and temperature stability is crucial, such as workshops where large equipment must remain on standby overnight to prevent freezing, the nighttime application of opaque insulation boards is the superior choice. The detailed selection strategy for the corresponding material is detailed in the conclusion of Section 3.1.2.

(2) For scenarios with a greater emphasis on daytime thermal comfort and energy savings, the full-time application of the PVC insulating film is the better solution. This approach demonstrates good applicability across all six building prototypes and is particularly effective in industrial buildings with poor existing window conditions.

3.2. Parameters of the Installation Configuration

The choice between an internal or external installation method is another critical factor affecting energy performance. While internal installation is more convenient for construction and maintenance, external installation improves the thermal performance of the window insulation system by shielding the glass from cold air and raising its inner surface temperature. The following subsections compare the energy-saving effects of these two methods across the six prototypes.

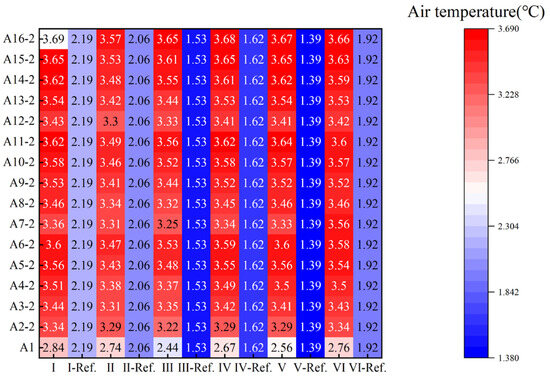

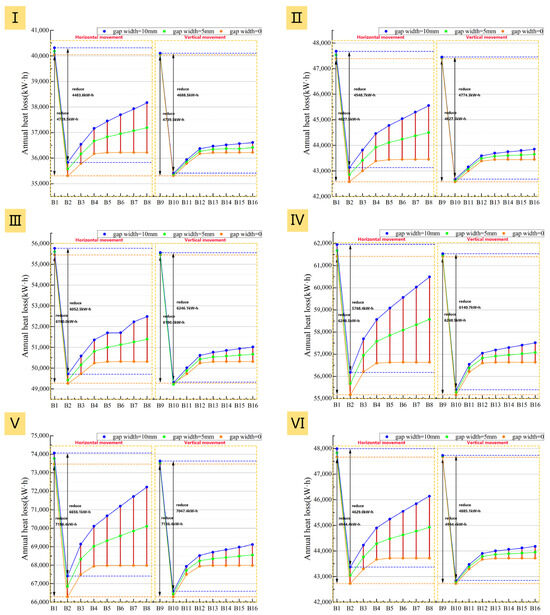

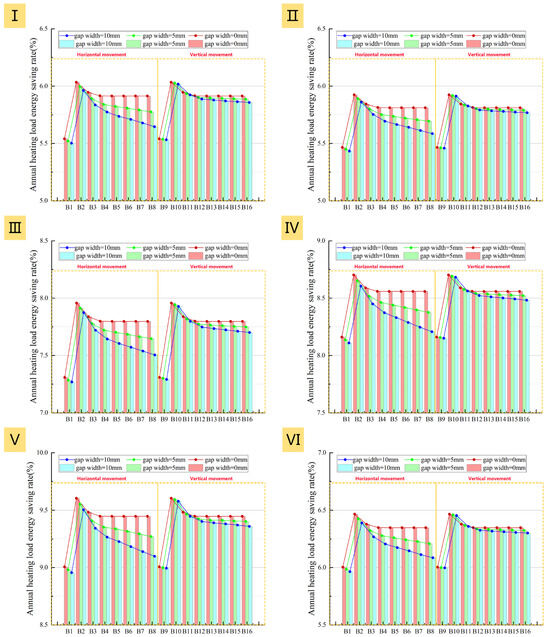

3.2.1. Internal Window Insulation Layer

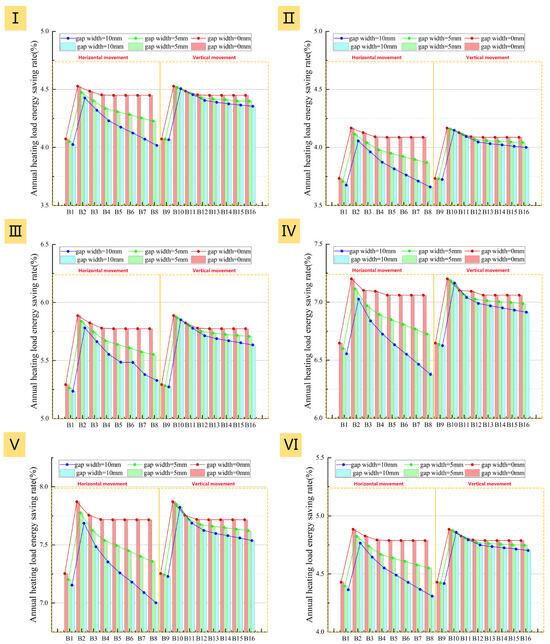

As shown in Figure 25 and Figure 26, for all building prototypes, the vertical adjustment method (B9–B16) significantly reduces the building heating load and net heat loss compared to the horizontal method (B1–B8). In addition to being less sensitive to air cavity thickness and gap width, the vertical system exhibits smaller curve fluctuations and less intra-group variation in figures. This indicates the vertical system possesses greater system stability and airtightness tolerance.

Figure 25.

Variation in total heating load with air cavity thickness under different adjustment methods for the window insulation layer: (I): Prototype I; (II): Prototype II; (III): Prototype III; (IV): Prototype IV; (V): Prototype V; (VI): Prototype VI.

Figure 26.

Effect of air cavity thickness on net heat loss under different adjustment methods: (I): Prototype I; (II): Prototype II; (III): Prototype III; (IV): Prototype IV; (V): Prototype V; (VI): Prototype VI.

The annual heating load energy saving rate curves (Figure 25) clearly show that all six prototypes achieve their peak energy saving rate at an air cavity thickness of 20 mm. Increasing the thickness from 10 mm to 20 mm significantly reduces the heating load and net heat loss for all adjustment methods, with little influence from airtightness (Figure 25 and Figure 26). This thickness range represents a critical phase of thermal resistance improvement, where heat conduction is the dominant heat transfer mechanism. For example, even with a 10 mm gap width in Prototype III, the heating load of B2 (with a 20 mm thick air cavity) is still 3345.2 kWh lower than that of B1 (with a 10 mm thick air cavity). Meanwhile, B10 under the vertical system shows an even greater reduction of 3540.7 kWh compared to B9 and thus holds a slight advantage in energy-saving performance.

However, further analysis shows that once the air cavity thickness exceeds 20 mm, the influence of airtightness on system performance becomes progressively stronger. Under ideally sealed conditions, the heating load and net heat loss first increase with thickness and then level off. In contrast, these two metrics rise continuously with thickness when gaps are present, with the increase being more pronounced as airtightness worsens (Figure 25 and Figure 26). The reason is that the combination of a thicker air cavity and poor airtightness readily induces natural convection loops. These loops allow outdoor air to continuously infiltrate the cavity through the gaps, intensifying convective strength and preventing stable heat retention.

Notably, a comparison of the two adjustment methods reveals that the building’s energy consumption is more sensitive to airtightness when using the horizontal method. This implies that the horizontal adjustment method requires stricter airtightness conditions and has higher construction demands. Therefore, based on a synthesis of energy saving performance and construction feasibility, the recommendation for retrofitting all six prototypes is that the optimal air cavity thickness should be controlled at an optimal value of approximately 20 mm, as smaller values are inadvisable. The vertical adjustment method is recommended, with the airtight interface preferably placed on the left and right sides of the window to mitigate potential leakage risks.

Furthermore, an analysis of the different prototypes’ performance shows that the higher the U-value of the existing window, the better the energy-saving efficacy of the added insulation layer. For example, Prototypes IV and V with single-glazed uPVC windows achieve an energy saving rate of 7.0–8.0%. In contrast, Prototypes I–III with double-glazed uPVC windows only reach 4.0–6.0% (Figure 27). However, it is crucial to note that a high energy saving rate represents the largest savings in heating costs, not necessarily the lowest absolute energy cost, as the absolute heating load remains high for poorly insulated buildings even after the retrofit.

Figure 27.

Effect of air cavity thickness on energy saving rate under different adjustment methods: (I): Prototype I; (II): Prototype II; (III): Prototype III; (IV): Prototype IV; (V): Prototype V; (VI): Prototype VI.

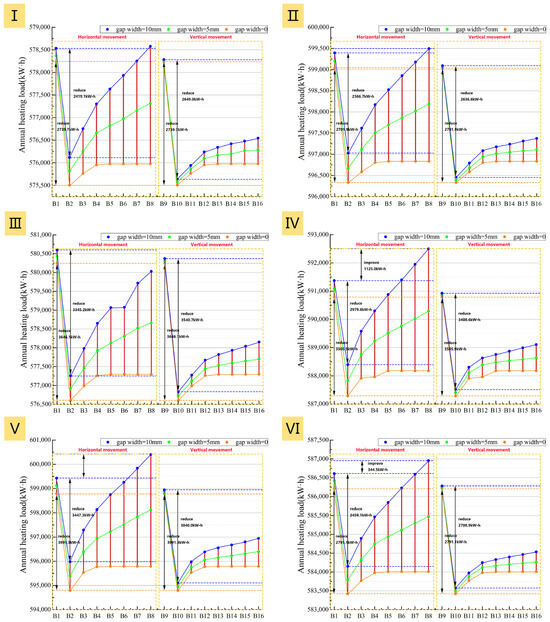

3.2.2. External Window Insulation Layer

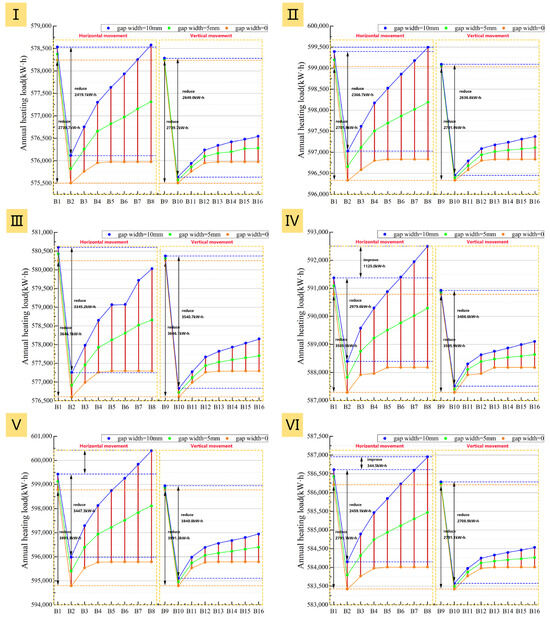

Compared to the internal insulation layer scenarios described in Section 3.2.1, the trends for heating load (Figure 28) and net heat loss (Figure 29) with increasing air cavity thickness are similar when using an external window insulation layer, but the absolute values are consistently lower across all six prototypes. The energy saving rate (Figure 30) is generally 1.5–2.0% higher, indicating a significant energy-saving advantage for exterior placement.

Figure 28.

Impact of insulation layer adjustment method and air cavity thickness on total heating load: (I): Prototype I; (II): Prototype II; (III): Prototype III; (IV): Prototype IV; (V): Prototype V; (VI): Prototype VI.

Figure 29.

Impact of insulation layer adjustment method and air cavity thickness on net heat loss: (I): Prototype I; (II): Prototype II; (III): Prototype III; (IV): Prototype IV; (V): Prototype V; (VI): Prototype VI.

Figure 30.

Impact of insulation layer adjustment method and air cavity thickness on energy saving rate: (I): Prototype I; (II): Prototype II; (III): Prototype III; (IV): Prototype IV; (V): Prototype V; (VI): Prototype VI.

More importantly, when the air cavity thickness exceeds 20 mm, the external installation demonstrates superior performance stability. Unlike the internal installation, the heating load for the external solution remains lower than that at a 10 mm air cavity thickness even with poor airtightness. As shown in Figure 28 and Figure 29, under three different airtightness conditions, the heating load of B8 is consistently lower than that of B1 for all six prototypes, and its energy saving rate is always higher than B1’s. This indicates that for external installation, the thermal resistance gains from increased thickness are not completely negated by potential convective effects, making the system more robust in practice.

Based on the comprehensive evaluation above, the optimal solution for a single-sided insulation layer is to use the external installation method with vertical adjustment, while maintaining the air cavity thickness at 20 mm.

3.2.3. Comparison of Single- and Double-Sided Insulation

The preceding analysis established that the energy-saving performance of an externally placed insulation layer is superior to that of an internally placed one with other parameters held constant. However, considering the low cost and significant insulation effect of the PVC insulating film, it is of practical importance to investigate the energy-saving gain when it is applied to both the interior and exterior surface. This section evaluates the energy-saving effects of the exterior-only and interior–exterior application methods by comparing their theoretically calculated thermal resistance and heat transfer coefficients. When the air cavity thickness is 20 mm, the thermal resistance value for a vertical sealed air layer is set to 0.17 (m2·K)/W, in accordance with ISO 6946:2017 [54] and ASHRAE Handbook—Fundamentals. Calculations were performed for two cases: a double-glazed uPVC window with a low U-value and a single-glazed uPVC window with a high U-value (Table 9). The most important conclusions can be summarized as follows:

Table 9.

Window U-values for single- and double-sided PVC film application.

(1) For window types with good thermal performance (e.g., double-glazed uPVC windows), the performance gain from a double-sided application should be viewed dialectically. On the one hand, adding a second layer on the interior side increases the total U-value reduction by a further 16.3%, a contribution equivalent to 52.5% of the first layer’s benefit, indicating a significant secondary improvement. On the other hand, because the initial performance is already good, the cumulative U-value reduction compared to the existing window is 47.5%, and the resulting absolute energy savings are relatively limited. Therefore, for high-performance windows, a double-sided application is an effective means of pursuing ultimate thermal performance, but the energy-saving gain from the additional interior layer is not significant.

(2) For window types with poor thermal performance (e.g., single-glazed uPVC windows), a double-sided application is the pathway to achieving the maximum energy savings. Adding a second layer increases the total U-value reduction by a further 16.8%, similar to the double-glazed case. Due to their relatively high initial U-value, this increase corresponds to a very considerable amount of energy savings, and the cumulative U-value reduction after the double-sided application is as high as 66.2%. However, from an efficiency perspective, the second layer’s contribution provides an insignificant gain of only 34.0% of the benefit from the first. Therefore, the final decision should be based on a project trade-off. If the primary goal is to maximize energy savings, the double-sided application is the solution with the highest potential. Conversely, if the focus is on the efficiency of the secondary improvement, the single-sided external application is the more reasonable choice due to its extremely high initial efficiency.

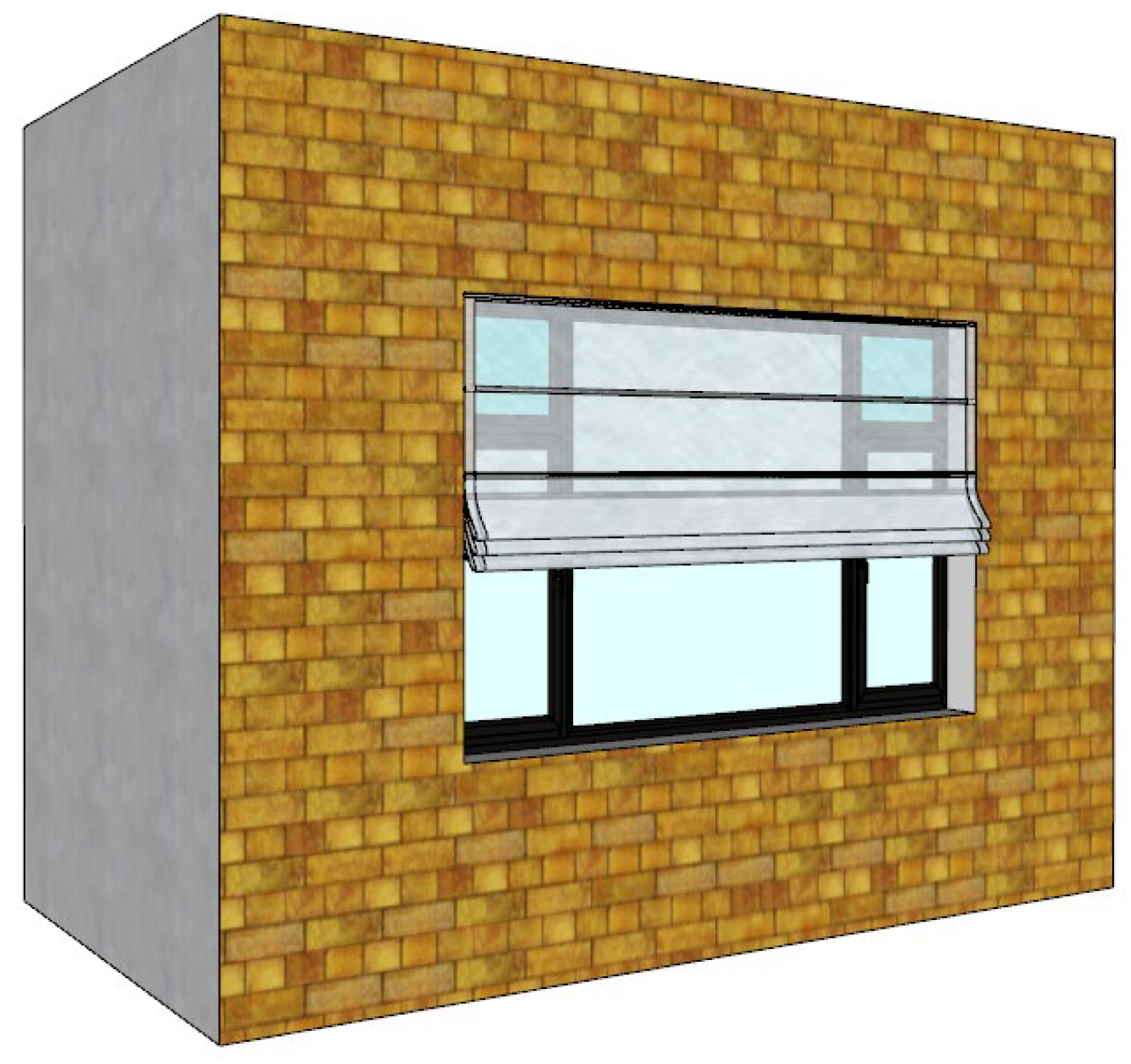

3.3. Integration of Insulation Systems with Prefabricated Facades

To align with the modular characteristics of prefabricated industrial buildings and ensure rigorous airtightness, distinct installation methods were developed. These strategies leverage the standardized fenestration modules and regular grid layouts of prefabricated facades to ensure that the retrofitting solutions are both structurally feasible and thermally effective.

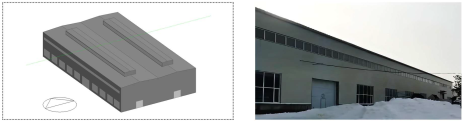

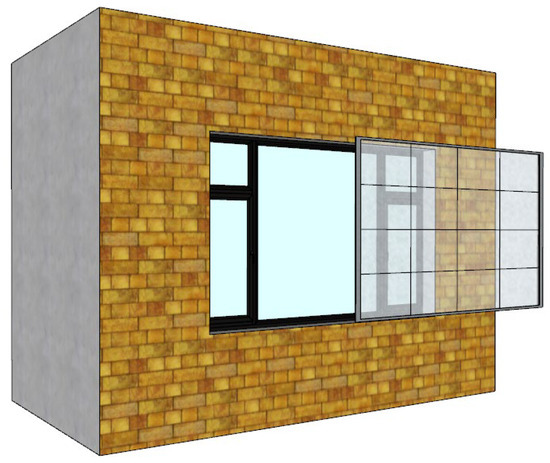

3.3.1. Integrated Roller Shutter System for Flexible Materials

The Integrated Roller Shutter System is engineered specifically for flexible insulation materials such as PVC films (Figure 31). It utilizes a motorized housing unit containing a rotating shaft, integrated seamlessly at the top of the existing window frame, along with lateral guide rails installed along the window opening. When retracted, the PVC thermal screen is wound neatly around the shaft within the top housing, ensuring no obstruction to window operation or natural ventilation. When insulation is required, the electric control mechanism deploys the PVC film along the guide rails until its bottom edge creates a flush seal with the windowsill. Crucially, the side rails and bottom seal provide a tight fit against the prefabricated facade elements, effectively preventing air leakage—a critical factor for thermal performance. The compact nature of the rolled film allows for a low-profile housing design that respects the standardized industrial facade rhythm, while its remote control capability makes it ideal for high-bay windows or skylights.

Figure 31.

Roller Shutter System: (a) Section; (b) Exterior.

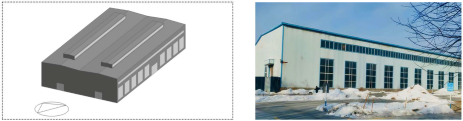

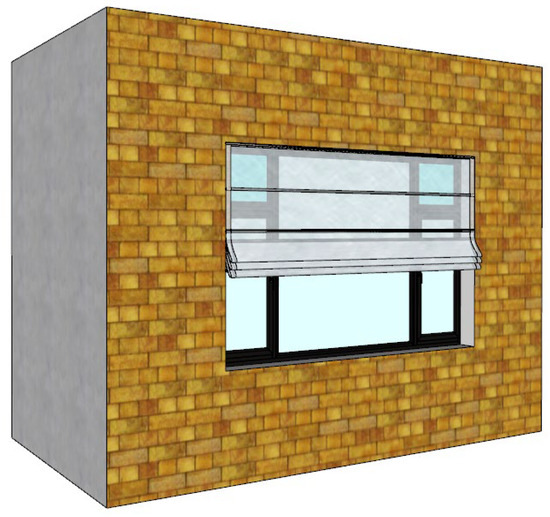

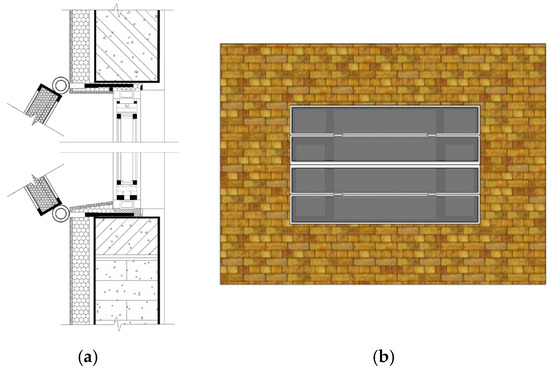

3.3.2. Modular Folding Panel System for Rigid Materials

The Modular Folding Panel System is designed for rigid insulation materials like EPS panels or semi-rigid films, adapting the kinematics of folding doors for retrofitting contexts (Figure 32). In this system, sliding tracks are installed on the exterior wall surface adjacent to the window opening, anchoring firmly to the load-bearing elements of the prefabricated wall panels. The mechanism consists of bi-folding insulation frames, where connecting pivots at the bottom of the frames are linked to sliders within the tracks via motor-driven rollers. This configuration allows the insulation panels to fold and unfold with precision. Beyond its primary insulation function, this modular design offers adjustable opening angles; users can partially deploy the panels to facilitate natural ventilation when needed, or fully close them to form a com30plete, sealed thermal barrier against the prefabricated structure during extreme cold periods.

Figure 32.

Folding Panel System: (a) Section; (b) Exterior.

4. Conclusions

This study evaluates a low-cost, easy-to-install window insulation system for the energy retrofitting of industrial buildings in the severe cold regions of Northeast China. A significant advantage of this system is that it requires minimal alteration to the existing building envelope, offering a practical and easily adoptable solution for improving window energy efficiency. Based on six typical building prototypes, this study conducts a systematic analysis using thermal simulation. The analysis clarifies the impact of two key factors (insulation material selection and installation method) and their secondary indicators on the system’s energy-saving mechanisms and applicability. Ultimately, this leads to the proposal of targeted application recommendations. The main conclusions can be summarized as follows:

(1) This study confirms that applying a low-cost insulation system to windows is an effective technical approach for improving the winter indoor thermal environment of industrial buildings in China’s severe cold regions. Because the system is easy to install and has minimal impact on the existing building, it holds high application value as a readily adoptable retrofit solution. The system’s energy-saving potential is primarily determined by the building’s initial thermal performance, with the poorer the initial performance leading to a higher energy-saving benefit. However, for industrial buildings with an east–west orientation and low Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR), the marginal energy-saving potential is limited (consistently below 2.0%), indicating a lower retrofitting priority for such typologies.

(2) The key advantage of transparent insulating film lies in its excellent full-time energy-saving performance and outstanding diurnal thermal balancing capability, making it the optimal choice for scenarios focused on daytime thermal comfort and overall energy savings, especially as a retrofit for windows with initially poor performance. Through a dynamic process of daytime heat storage and nighttime heat preservation, it effectively suppresses nighttime heat loss while maintaining daytime solar gain, allowing its energy saving rate to reach up to 10.3% and the nighttime indoor temperature to increase by as much as 1.5 °C.

(3) Opaque insulation boards are the superior choice for scenarios prioritizing high nighttime insulation demands, such as for equipment frost protection, capable of increasing the average nighttime indoor temperature by up to 2.28 °C. Although a material’s U-value determines its baseline insulation capability, its surface emissivity is a critical variable that can alter the performance. Reducing surface emissivity from 0.92 to 0.05 can effectively substitute for approximately 20 mm of physical insulation thickness, potentially allowing a material with poorer baseline performance to outperform a better one, but it also significantly diminishes the marginal benefit of adding further thickness. Therefore, for projects prioritizing economic benefits, combining low-emissivity foil with EPS (payback period 0.6–3.2 years) or XPS (payback period 0.7–2.9 years) is recommended, while PUR combined with foil is the choice for maximum performance.

(4) The study ultimately identifies the optimal installation method for the window insulation system. For a single-sided application, the optimal strategy is to install an externally applied PVC film that is vertically adjusted for daily control and maintain a 20 mm air cavity. This not only achieves the best overall energy-saving effect but also minimizes the negative impacts of airtightness, thereby lowering the demands on construction technique. In most cases, this single-sided application strategy is sufficient, and a double-sided application should only be considered when pursuing ultimate thermal performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.; software, M.C.; validation, M.C.; formal analysis, M.C.; investigation, M.C.; data curation, M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.; writing—review and editing, L.F.; supervision, L.F.; project administration, L.F.; funding acquisition, L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Project, grant number 2022YFC3800303.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TMY | Typical Meteorological Year |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| PVC | Polyvinylchloride |

| EPS | Expanded Polystyrene Foam |

| XPS | Extruded Polystyrene Foam |

| PUR | Polyisocyanurate Foam |

| WWR | Window–wall Ratio |

| SHGC | Solar Heat Gain Coefficient |

References

- Guo, S.Y.; Yan, D.; Hu, S.; Zhang, Y. Modelling building energy consumption in China under different future scenarios. Energy 2021, 214, 119063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.Y.; Chen, P.K. Human response to window views and indoor plants in the workplace. Hortscience 2005, 40, 1354–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.S. The influence of forest view through a window on job satisfaction and job stress. Scand. J. Forest Res. 2007, 22, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R.; Selkowitz, S.; Curcija, C. Thermal performance and potential annual energy impact of retrofit thin-glass triple-pane glazing in US residential buildings. Build. Simul. 2019, 12, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelle, B.P.; Hynd, A.; Gustavsen, A.; Arasteh, D.; Goudey, H.; Hart, R. Fenestration of today and tomorrow: A state-of-the-art review and future research opportunities. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2012, 96, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.J.; Zhou, C.Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, S.C.; Chan, S.H.; Long, Y. Emerging Thermal-Responsive Materials and Integrated Techniques Targeting the Energy-Efficient Smart Window Application. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1800113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.X.; Zhong, X.Y.; Cai, W.G.; Ren, H.; Huo, T.F.; Wang, X.; Mi, Z.F. Dilution effect of the building area on energy intensity in urban residential buildings. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.J.; Liu, Y.W.; He, B.J.; Xu, W.; Jin, G.Y.; Zhang, X.T. Application and suitability analysis of the key technologies in nearly zero energy buildings in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 101, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalapati, G.K.; Kushwaha, A.K.; Sharma, M.; Suresh, V.; Shannigrahi, S.; Zhuk, S.; Masudy-Panah, S. Transparent heat regulating (THR) materials and coatings for energy saving window applications: Impact of materials design, micro-structural, and interface quality on the THR performance. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 95, 42–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T. Solar shading and daylighting by means of autonomous responsive dimming glass: Practical application. Energy Build. 2003, 35, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Liu, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, T.; Li, D.; Ma, L. Energy performance of window with PCM frame. Sustain. Energy Technol. 2021, 45, 101109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsaif, M.A.; Jalil, J.M.; Baccar, M. Experimental Investigation of the Thermal Performance of Triple Glazed Windows Integrated with PCM and Low-e Glass. Int. J. Heat Technol. 2024, 42, 1735–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yang, H.X.; Peng, J.Q. Solar PV vacuum glazing (SVG) insulated building facades: Thermal and electrical performances. Appl. Energy 2024, 376, 124323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Qiu, Y.M.; James, T.; Ruddell, B.L.; Dalrymple, M.; Earl, S.; Castelazo, A. Do energy retrofits work? Evidence from commercial and residential buildings in Phoenix. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2018, 92, 726–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banti, N. Existing industrial buildings—A review on multidisciplinary research trends and retrofit solutions. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruner, M.; Matusiak, B.S. A Novel Dynamic Insulation System for Windows. Sustain. 2018, 10, 2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.Y.; Liu, X.; Ming, Y.; Liu, X.; Mahon, D.; Wilson, R.; Liu, H.; Eames, P.; Wu, Y.P. Energy and daylight performance of a smart window: Window integrated with thermotropic parallel slat-transparent insulation material. Appl. Energy 2021, 293, 116826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzempelikos, A.; Athienitis, A.K. The impact of shading design and control on building cooling and lighting demand. Sol Energy 2007, 81, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariosto, T.; Memari, A.M.; Solnosky, R.L. Development of designer aids for energy efficient residential window retrofit solutions. Sustain. Energy Technol. 2019, 33, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.W.; Sun, L.N.; Liu, D.Y.; Xu, B.Y.; Mo, Z.J. Potential of indoor room 3D ratio in reducing carbon emissions by prefabricated decoration in chain hotel buildings via multidimensional algorithm models for robot in-situ 3D printing. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 101, 111757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.W.; Guo, X.T.; Sun, Y.G. Prefabricated building construction in materialization phase as catalysts for hotel low-carbon transitions via hybrid computational visualization algorithms. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, G.; Liu, D.; Wu, Z. Multidimensional algorithms-based carbon efficiency model of building geometric 3D ratios for prefabricated 3D printing design and construction. npj Clean Energy 2025, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaco, S.G.; Kurian, C.P.; George, V.I.; Colaco, A.M. Prospective Techniques of Effective Daylight Harvesting in Commercial Buildings by Employing Window Glazing, Dynamic Shading Devices and Dimming Control-A Literature Review. Build. Simul. 2008, 1, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Paik, T. Recent Advances in Fabrication of Flexible, Thermochromic Vanadium Dioxide Films for Smart Windows. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunwar, N.; Cetin, K.S.; Passe, U.; Zhou, X.H.; Li, Y.H. Full-scale experimental testing of integrated dynamically-operated roller shades and lighting in perimeter office spaces. Sol Energy 2019, 186, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.T.; Liu, H.B.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, N.; Yang, L.; Jin, X. Thermal analysis of the window-wall interface for renovation of historical buildings. Energy Build. 2024, 310, 114108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.Y.; Diao, J.X.; Yao, S.; Yuan, J.Y.; Liu, X.; Li, M. Seasonal optimization of envelope and shading devices oriented towards low-carbon emission for premodern historic residential buildings of China. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 64, 105452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohene, E.; McGehee, M.D.; Krarti, M. Quantifying energy benefits from window improvement strategies for commercial buildings. Energy Build. 2025, 347, 116239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, R.S.; Rhee, K.N. Experimental study on the thermal performance of thermally activated internal louvers. Build. Environ. 2025, 284, 113440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basok, B.; Novikov, V.; Pavlenko, A.; Koshlak, H.; Goncharuk, S.; Shmatok, O.; Davydenko, D. Sustainable Increase in Thermal Resistance of Window Construction: Experimental Verification and CFD Modelling of the Air Cavity Created by a Shutter. Materials 2025, 18, 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbagh, M.; Krarti, M. Experimental evaluation of the performance for switchable insulated shading systems. Energy Build. 2022, 256, 111753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamus, J.; Pomada, M. Analysis of the Influence of External Wall Material Type on the Thermal Bridge at the Window-to-Wall Interface. Materials 2023, 16, 6585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Clayton, M.J. Parametric behavior maps: A method for evaluating the energy performance of climate-adaptive building envelopes. Energy Build. 2020, 219, 110020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krarti, M. Performance of PV integrated dynamic overhangs applied to US homes. Energy 2021, 230, 120843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ali, A.S.; Haratian, S.; Stephens, B.; Heidarinejad, M. A framework to evaluate the thermal and energy performance of smart building systems in existing buildings: A case study on automated interior insulating window shades. Methodsx 2025, 14, 103378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 55016-2021; General Code for Building Environment. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Djokovic, J.M.; Nikolic, R.R.; Bujnak, J.; Hadzima, B.; Pastorek, F.; Dwornicka, R.; Ulewicz, R. Selection of the Optimal Window Type and Orientation for the Two Cities in Serbia and One in Slovakia. Energies 2022, 15, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.Z.; Akashi, Y.; Sumiyoshi, D. Optimization of passive design measures for residential buildings in different Chinese areas. Build. Environ. 2012, 58, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hee, W.J.; Alghoul, M.A.; Bakhtyar, B.; Elayeb, O.; Shameri, M.A.; Alrubaih, M.S.; Sopian, K. The role of window glazing on daylighting and energy saving in buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Tzempelikos, A. Sensitivity analysis on daylighting and energy performance of perimeter offices with automated shading. Build. Environ. 2013, 59, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Li, Q.; Xie, J.C.; Zhao, M.J.; Liu, J.P. Optimization of window-to-wall ratio with sunshades in China low latitude region considering daylighting and energy saving requirements. Appl. Energy 2019, 233, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krarti, M. Optimal energy performance of dynamic sliding and insulated shades for residential buildings. Energy 2023, 263, 125699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altun, A.F. Determination of Optimum Building Envelope Parameters of a Room concerning Window-to-Wall Ratio, Orientation, Insulation Thickness and Window Type. Buildings 2022, 12, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Lazarus, I.J.; Kishore, V.V.N. Effect of internal woven roller shade and glazing on the energy and daylighting performances of an office building in the cold climate of Shillong. Appl. Energy 2015, 159, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 51245-2017; Unified Standard for Energy Efficiency Design of Industrial Buildings. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2017.

- GBZ/T 189.10-2007; Measurement of Physical Factors in Workplace—Part 10: Classification of Physical Workload. People’s Medical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2007.

- GB/T 50785-2012; Evaluation Standard for Indoor Thermal and Humid Environment in Civil Buildings. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Atzeri, A.; Cappelletti, F.; Gasparella, A. Internal versus external shading devices performance in office buildings. Energy Procedia 2014, 45, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Múcka, M.; Sedivka, P.; Bomba, J.; Blazek, J. Influence of Spacer Frames for Wooden Roof Windows on the Formation of Surface Condensation. Bioresources 2016, 11, 6174–6184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.Y.; Jo, J.H.; Yeo, M.S.; Kim, Y.D.; Song, K.D. Evaluation of inside surface condensation in double glazing window system with insulation spacer: A case study of residential complex. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 940–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]