Abstract

In the context of advancing sustainable local building materials, this study evaluates the mechanical impact of polypropylene (PP) fiber reinforcement on adobe bricks, specifically addressing the novel variable of fiber addition timing relative to the traditional 45-day biological fermentation process. Two experimental scenarios were investigated: fiber addition before fermentation and fiber addition after fermentation. In the pre-fermentation scenario, the unreinforced control specimen achieved the highest mean compressive strength (1.92 MPa), followed by reduced values of 1.66 MPa (0.25%), 1.60 MPa (0.50%), and 1.55 MPa (1.00%). In the post-fermentation scenario, the control recorded 1.81 MPa, while the PP-reinforced mixtures reached 1.73 MPa (0.25%), 1.65 MPa (0.50%), and 1.77 MPa (1.00%). Across both stages, PP fibers consistently decreased in strength due to weak bonding at the fiber–soil interface, as their hydrophobic nature disrupts the fermentation-derived biopolymer network formed by straw decomposition. Overall, this study highlights the limitations of synthetic fiber reinforcement within biologically stabilized adobe and contributes to the ongoing development of sustainable earthen construction systems.

1. Introduction

Mud is one of the oldest historical masonry materials in the Arabian Peninsula since it was characterized as a locally available material, safe, easy to shape, and suitable for the climate [1]. Despite these advantages, traditional adobe bricks face significant limitations in contemporary building materials since they have limited resistance to environmental factors and weak structural capacity [2]. Historically, the incorporation of natural fibers, such as straw, served as the primary method for mitigating shrinkage cracks, helped reduce cracks, and improved cohesion [3].

However, some studies have shown that the effectiveness of plant fiber varies depending on the type of fiber used, the proportion of fiber to mud, and the processing method [4]. For example, polyethylene fiber is noted as a popular synthetic fiber and was used historically to compress earth blocks (CEBs) and construct materials like concrete. Polypropylene (PP) is also recognized as one of the most popular types of synthetic fibers used since the early 1960s to enhance the mechanical properties of building materials [5].

In this context, polymer fibers have emerged as a newer option, but research results on their effectiveness remain contradictory [4]. Critical oversight in existing studies is that they focus on fiber content and geometry while largely neglecting the specific processing methodology and the timing of fiber addition relative to the traditional biological fermentation of the clay mixture. Recently in Saudi Arabia (SA), a new architectural framework has emerged, which is known as Salmani Architecture; this framework reconciles authenticity and heritage on the one hand, and sustainability and development requirements on the other hand, optimizing adobe production in a timely manner.

From this perspective, this study aims to bridge this gap by evaluating the effect of PP fibers on the compressive strength of adobe bricks, with a novel focus on the timing of fiber addition (pre-fermentation vs. post-fermentation). This approach is based on the hypothesis that the timing at which hydrophobic inclusions are introduced influences the continuity of the clay matrix. Specifically, this study investigates whether adding fibers prior to fermentation interferes with the development of biopolymer networks derived from straw, versus whether addition of fibers post-fermentation avoids interference with the established biopolymer matrix.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Clay Bricks as an Economical and Sustainable Building Material

Recent decades have witnessed growing interest in adobe bricks as an economical building material associated with local architectural identity. Studies have indicated that the compressive strength of unfired or air-dried adobe bricks ranges from 0.6 to 2.0 megapascals (MPa), while compressed earth bricks can achieve higher strengths of 2 to 5 MPa under optimized manufacturing conditions [1,6]. These results highlight the wide variation in adobe brick performance based on the processing methods.

2.2. The Effect of Natural and Synthetic Fibers

Many researchers have examined the effect of adding natural fibers, such as straw and hay, on improving the properties of clay bricks. It has been demonstrated that adding fiber to clay bricks contributes to reducing shrinkage and cracking as it improves the distribution of internal stresses [3]. However, excessive use of fibers, ranging from 25 to 75%, leads to a significant decrease in the compressive strength of adobe bricks, confirming that the optimal percentage does not exceed 1% of the mud weight [4,7].

In recent years, there has been a trend toward using synthetic and polymeric fibers as a modern alternative to natural fibers. Some studies have shown that a limited addition of polymeric fibers (0.25–0.50%) can enhance compressive strength and increase the durability of adobe bricks [4,8]. Crucially, fiber reinforcement addresses the inherent mechanical weaknesses of raw earth; empirical results indicate that an optimal PP fiber content of 0.23% can increase compressive strength by approximately 84%, enabling the bricks to meet the 5 MPa load-bearing standard [9]. Furthermore, this reinforcement reduces the initial rate of water adsorption by 50% and transforms the failure mode from brittle to ductile, preventing catastrophic collapse and confirming the viability of reinforced earth bricks for modern structural applications [9].

However, the results remain contradictory due to differences in soil properties, the chemical and physical nature of the fibers, and manufacturing methods. While the mechanical benefits of PP fibers are well-documented, as detailed above, the existing literature has predominantly focused on fiber dosage and geometry, assuming a standard mixing process. However, traditional adobe production relies heavily on a biological fermentation process involving organic straw to generate biopolymers that stabilize the clay matrix. The interaction between hydrophobic synthetic fibers (like PP) and this hydrophilic biological process remains unexplored. Specifically, it is unknown whether introducing fibers before fermentation interferes with the development of the clay–straw matrix, or if adding fibers after fermentation disrupts the established cohesive bonds. This study addresses this specific gap by isolating the timing of fiber addition as a primary variable.

3. Materials and Methods

This study aimed to test the effect of adding polymeric fibers made of PP to adobe bricks on its compressive strength based on the timing of fiber addition to mud mixtures; the selection of PP fibers was made based on their hydrophobic, alkali-resistant, and chemically inert nature, which provides superior long-term durability in blocks compared to natural fibers, while also providing significant mechanical benefits like ductility and crack control [9,10].

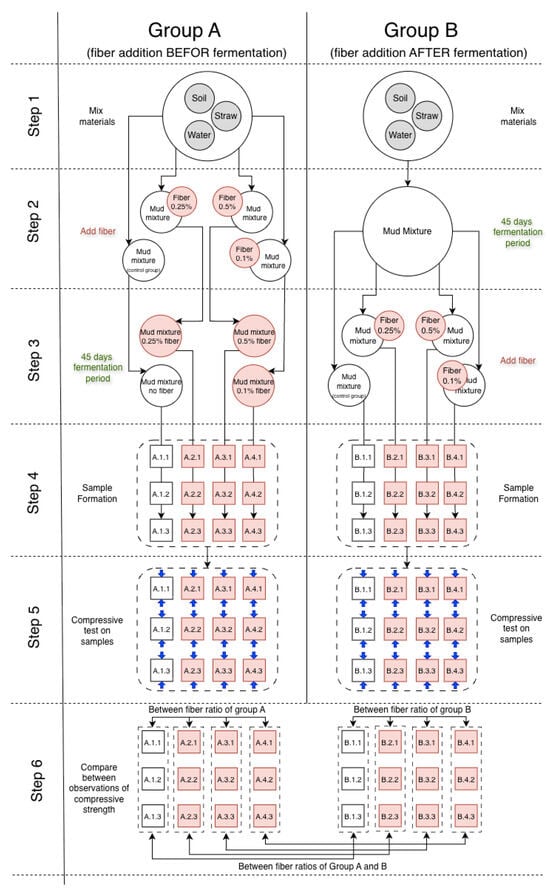

To achieve this, a systematic six-step experimental protocol was established. This methodology was designed to strictly control material properties and ensure the reproducibility of results (Figure 1). The samples were categorized into primary groups based on the fiber introduction phase: Group A (pre-fermentation addition) and Group B (post-fermentation addition). Crucially, all mixtures and forming processes—other than the addition of fiber—were kept constant across all specimens to ensure that the effect of fiber addition was the sole independent variable.

Figure 1.

Research methodology.

The methodology proceeded as follows:

- Material Preparation: The base soil was first processed through a 2 mm sieve to eliminate large aggregates and impurities, while agricultural straw was cut to a uniform length of 15 mm to facilitate homogeneous mixing.

- Mixing: The soil and straw were manually blended with drinking water (approximately 40% by weight) to create a cohesive mud paste. For Group A specimens, PP fibers were gradually integrated during the initial kneading phase.

- Fermentation: The mixture was stored in covered containers for a 45-day fermentation period under ambient outdoor conditions (averaging 37.2 °C and 28% relative humidity), with weekly stirring to maintain moisture equilibrium.

- Post-Fermentation Addition: For Group B, fibers were introduced only after the 45-day fermentation period was complete; they were sprinkled into the fermented mud during the secondary kneading stage.

- Molding and Drying: The processed mixtures were compacted into lubricated 50 mm3 metal molds, leveled, and subsequently air-dried in direct sunlight for 14 days to ensure natural hardening.

- Testing: Finally, the cured specimens were subjected to uniaxial compressive strength tests to quantify mechanical performance.

Descriptive statistical analysis (mean and standard deviation) and graphical representation of the compressive strength results were performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft 365, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

3.1. Material Used

Four materials were used in conducting this experimental study: soil, agricultural straw, polymeric fibers, and drinking water. The soil was obtained from a brick factory in the Diriyah area of Riyadh, SA. This local soil represents the traditional base material historically used in the production of adobe bricks in the region. To determine its characteristics and ensure its suitability for mud construction, a comprehensive engineering characterization was conducted.

Grain-size distribution analysis performed in accordance with ASTM D422 [11] indicated that the soil consists of a well-graded sand–silt–clay mixture, with sand ranging between 45 and 52%, silt ranging between 22 and 27%, and clay ranging between 14 and 20%. Gravel content was minimal (1–12%) and did not significantly influence the overall behavior of the adobe mixtures. This particle-size distribution is considered ideal for reducing excessive drying shrinkage and improving volumetric stability during forming and natural curing. Furthermore, Atterberg limits revealed that the soil exhibits medium plasticity, with a Liquid Limit (LL) of approximately 42%, Plastic Limit (PL) of 27%, and Plasticity Index (PI) of 15%, falling within the optimal range for adobe brick production.

Agricultural straw was collected from the same source as the soil. Consistent with traditional Diriyah masonry, the straw was incorporated to enhance cohesion and minimize surface cracking. It was chopped to a uniform length of approximately 15 mm to ensure homogeneous distribution and added to the mixture at a fixed ratio of 3% by weight of the dry soil.

Polymeric fibers made of PP were used due to their chemical stability and inertness during the 45-day fermentation period. These characteristics prevent degradation under the alkaline conditions generated within the clay–straw matrix and ensure that the fibers remain dimensionally stable throughout processing. PP fibers were also selected because they represent one of the most widely studied synthetic fibers in soil stabilization research, making them an appropriate baseline for comparison within adobe systems. Additionally, PP fibers are widely available in local markets as low-cost industrial waste, which aligns with the sustainability objectives of this study. These fibers had a nominal length of 12 mm, a diameter of 0.38 mm, and a density of 0.91 g/cm3, and were incorporated into the mixtures at weight percentages of 0.00%, 0.25%, 0.50%, and 1.00% of the dry soil.

Drinking water was used to adjust the moisture content to approximately 40% of the mixture weight, ensuring appropriate consistency during mixing and molding. Figure 2 illustrates the physical appearance of the materials used, including a 20 cm ruler for visual reference.

Figure 2.

(a) Clay material; (b) agricultural straw; and (c) polymeric fiber with a ruler of 20 cm.

3.2. Preparation of Materials and Mixtures

The preparation process commenced with precise conditioning of raw materials to ensure mixture consistency. The soil was passed through a 2 mm sieve to eliminate impurities and coarse gravel. Concurrently, the agricultural straw was prepared by cutting it to a fixed length of 15 mm and adding it at a ratio of 3% by dry soil weight to facilitate its integration into the clay matrix.

The mixing procedure was conducted manually to ensure thorough blending. The sieved soil and straw were combined with a calculated quantity of water (approximately 40% by weight), which was added gradually until a homogeneous mud paste was achieved. For specimens in Group A, the PP fibers were introduced during the wet mixing phase. To satisfy the requirements for homogeneous distribution, the fibers were sprinkled slowly over the wet mud while continuously kneading the mixture, which is a technique specifically employed to prevent fiber clumping or agglomeration.

3.3. Experimental Groups

The samples were divided into two main groups based on the timing of fiber additions to clay mixtures:

- Group A—Pre-fermentation: Soil, straw, water, and fiber were mixed together before beginning fermentation for 45 days.

- Group B—Post-fermentation: Soil, straw, and water were mixed together, then fermented for 45 days, and fibers were then added immediately before forming.

For each group, four fiber ratios were prepared (0.00%, 0.25%, 0.50%, 1.00%), with three replicates for each ratio (n = 3). It is crucial to note that the ratio of water to soil and straw to soil was the same across all samples.

3.4. Fermentation

Groups A and B were transferred to covered vessels and subjected to a 45-day fermentation period in an outdoor environment. This phase was characterized by specific environmental conditions, with an average recorded temperature of approximately 37.2 °C and a relative humidity of 28%. To ensure material homogeneity and prevent the formation of a surface crust, the mixtures were stirred on a weekly basis throughout this period. Upon completion of fermentation, PP fibers were gradually sprinkled and kneaded into the Group B mixtures to ensure uniform distribution.

3.5. Sample Formation and Dimensions

Upon completion of the fermentation phases, the mixtures were compacted into lubricated metal molds with dimensions of 50 mm × 50 mm × 50 mm. The top and bottom faces of each specimen were leveled to ensure surface parallelism. Subsequently, the samples were air-dried under direct sunlight for 14 days to facilitate natural and uniform hardening.

3.6. Compression Resistance Test

Following the drying phase, the specimens were subjected to uniaxial compression testing to determine their compressive strength values. This test was conducted using an Advanced Digital Readout (ADR) Touch device from ELE International (Milton Keynes, UK) (Figure 3), following ASTM C67 [12] procedures adapted for unfired earthen materials. The compressive strength (σ) was calculated using the standard relationship σ = P/A, where P is the maximum applied load (N), and A is the loaded surface area (2500 mm2). Results are expressed in megapascals (MPa). Strict adherence to these preparation and testing protocols ensured controlled conditions and highlighted the importance of achieving homogeneous fiber distribution for reproducible results.

Figure 3.

Axial pressure device.

The methodological choice of adapted ASTM C67 is justified, as this standard—when modified—has been widely applied to evaluate unfired adobe- and soil-based construction materials due to its compatibility with their brittle behavior and heterogeneous microstructure. Furthermore, the use of 50 mm cubic specimens was intentional: the reduced specimen size minimized platen friction during compression testing, decreased internal moisture gradients during drying, and aligned with established laboratory protocols for small-scale soil–cement testing. Collectively, these considerations validate the use of adapted ASTM C67 and justify the selection of 50 mm specimens in this study.

3.7. Statistical Analysis Plan

This study hypothesizes that adding polymeric fibers to clay mixtures before and after the fermentation process improves the capacity of adobe blocks to bear higher compressive strength in comparison with adobe blocks with no added polymeric fibers. This study also hypothesizes that the higher the ratio of polymeric fibers in the clay mixture (0.25%, 0.50%, and 1.00%), the higher the compressive strength of adobe blocks.

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) were carried out to compare the compressive strength of adobe bricks of different polymeric fiber ratios with adobe bricks without added fibers. The mean and standard deviation of compressive strength were then used to prepare tables and graphs that conceptualize the relationship between polymeric fiber ratios and compressive strength.

4. Results

4.1. The First Experiment—Adding Polymeric Fibers Before Fermentation (Group A)

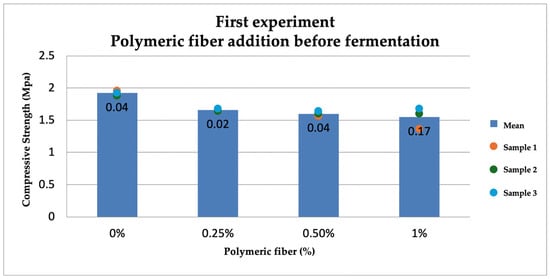

This experiment aimed to test the effect of early addition of polymeric fibers to straw-containing mixes undergoing fermentation. The results (as in Table 1 and Figure 4) show that the control group (0.00% fiber) recorded the highest mean compressive strength of 1.92 MPa, while the mean values of compressive strength gradually decreased as the fiber ratio increased in group A. At 0.25% of polymeric fiber, the strength reached 1.66 MPa; at 0.50% of polymeric fiber, the strength reached 1.60 MPa; and at 1.00% of polymeric fiber, the strength decreased to 1.55 MPa.

Table 1.

Results of the first experiment—adding polymeric fibers to mud mixtures with straw before fermentation.

Figure 4.

Mean compressive strength with error bars (standard deviation) for the first experiment.

This demonstrates that early addition of polymeric fibers did not achieve any improvement but rather was associated with a significant decrease in maximum compressive strength as the percentage of polymeric fiber increased compared to the control group. Moreover, for the set of samples with a 1% fiber ratio, the variation in the compressive strength was high in comparison to the samples with lower fiber ratios.

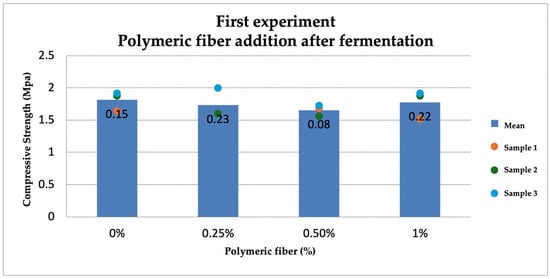

4.2. The Second Experiment—Adding Polymeric Fibers After Fermentation (Group B)

This experiment aimed to evaluate the feasibility of adding polymeric fibers after the completion of the fermentation process. The results (Table 2 and Figure 5) showed that the control group (0.00% fibers) had the highest mean compressive strength (1.81 MPa). Samples with added polymeric fibers recorded lower means of compressive strength, ranging from 1.65 to 1.77 MPa.

Table 2.

Results of the second experiment—adding fibers after fermentation.

Figure 5.

Mean compressive strength with error bars (standard deviation) for the second experiment.

These results confirm that the addition of fibers after fermentation did not improve the compressive strength but rather showed a decrease in the compressive strength similar to that observed in the first experiment. It is useful to note that the decrease in the ratio of maximum pressure was slightly less than that with fibers added during the fermentation period, indicating that polymeric fibers might also have a negative effect on fermentation.

4.3. Summary of Results

A comparison between the two experiments revealed that the control groups (0.00% fiber) had the highest mean compressive strength in both experiments, indicating that the addition of fibers to clay mixtures with straw and fermentation, within the ratios tested, does not improve the compressive strength of adobe blocks.

The results of this experimental study are consistent with the findings of previous research, where the nature of the clay mixture and the timing of fiber addition to it are critical factors in the success of fiber enrichment in clay mixtures of clay bricks [4,13].

5. Discussion

5.1. Ineffectiveness of Added Fibers with Straw

The findings of this study diverge from research on non-fermented soil composites, where PP fibers typically enhance strength. In this investigation, the combination of organic straw and synthetic PP fibers resulted in a net reduction in compressive strength. This phenomenon can be attributed to two primary mechanisms:

- PP fiber is inherently hydrophobic, which limits its adhesion to the surrounding clay particles and leads to the formation of a weak Interfacial Transition Zone (ITZ) around the fibers. This effect becomes more pronounced in the presence of straw, as the hydrophobic PP fibers interfere with the development of the biopolymer network generated during straw fermentation. As a result, the coexistence of straw and PP fibers disrupts matrix continuity and further weakens the ITZ.

- Mechanical Interference with Biopolymer Bonding: Traditional processing relies on the biological decomposition of organic straw: a process which releases natural biopolymers (such as polysaccharides) that act as binding agents for clay particles [10,14,15]. The presence of PP fibers, particularly in Group A, mechanically interrupts this continuous organic network, suggesting that polymeric fibers may interfere with the fermentation process and initiate internal cracking points, consistent with observations from other studies [4]. Unlike straw, which decomposes to chemically enhance cohesion, PP fibers are inert inclusions, potentially creating voids or discontinuities within the matrix where these organic binders fail to bridge the gap.

5.2. Effect of Timing of Addition

The study was designed to test the hypothesis that timing matters. The results confirm this hypothesis: Group A (pre-fermentation) performed worse than Group B. This supports the theory that the physical presence of synthetic fibers during the biological activity of fermentation is disruptive. The fibers likely impede the uniform distribution of moisture and microbial activity required for optimal fermentation. By adding fibers after fermentation (Group B), the biopolymer network is allowed to form undisturbed, resulting in a matrix that, while still weakened by hydrophobic inclusions, is structurally superior to Group A. These results are consistent with previous studies [5,13], which show that excessive addition of fibers at inappropriate timing can affect the structural integrity of the material.

5.3. Comparison with the Findings of Previous Studies

- Natural fibers: Studies such as [13] have established that natural fiber reinforcement enhances cohesion and mitigates shrinkage cracking. However, the net efficacy of inclusions is variable, contingent upon the specific fiber type utilized and the methodology of addition.

- Polymer fibers: Studies such as [8] support mechanical benefits of low-dosage polymer addition in standard mixes; they also highlight inconsistencies when these fibers are introduced into organic clay mixtures. The results of the present study corroborate these findings, confirming that the presence of organic matter complicates the reinforcement mechanisms.

- A critical comparison clarifies the mechanism behind these discrepancies. For instance, Ref. [9] reported an 84% increase in strength with 0.23% PP fibers. Their study utilized laterite soil without straw fermentation. In contrast, our results align with [4], which observed reductions in strength of organic-rich soils. This discrepancy underscores the fact that the success of synthetic reinforcement is highly context-dependent: PP fibers work well in inert, mechanically stabilized soils but may be counterproductive in biologically stabilized (fermented) traditional adobe.

5.4. Applied Implications

This study presents an important negative finding, showing that the incorporation of modern synthetic fibers into traditional fermented adobe systems does not necessarily lead to strength enhancement. For the preservation of Salmani Architecture and the advancement of sustainable earthen construction in SA, the results indicate that traditional reinforcement mechanisms—particularly the straw-based biopolymer network formed during fermentation—remain superior unless the fiber–matrix interface can be effectively modified. Improving this interface may require chemical surface treatments that increase fiber hydrophilicity or the exploration of alternative biocompatible fibers that do not interfere with the fermentation-based bonding process.

5.5. Alignment with Sustainable Architecture

These findings align with the main principles of sustainable architecture, which mainly aim to lower carbon emissions, improve energy efficiency, and ensure resilience over a project’s duration.

Using natural materials such as soil, straw, and water is expected to reduce the reliance on synthetic materials with a high embodied carbon footprint resulting from raw material extraction, manufacturing, and installation on construction sites. In addition, adobe blocks are valued for their natural thermal insulation properties, making them effective in maintaining a stabilized indoor temperature, reducing energy consumption for heating and cooling buildings. Furthermore, clay, as a natural and locally available material, also allows for easier repair or replacement and minimizes environmental damage from deconstruction.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

This study aimed to evaluate the mechanical impact of PP fiber reinforcement on locally produced adobe bricks in Riyadh, specifically examining whether the timing of fiber addition relative to the traditional fermentation process influences compressive strength. The empirical evidence confirms that, within the specific context of organic-rich, fermented straw–clay mixtures, the inclusion of hydrophobic PP fibers does not enhance mechanical performance. Regardless of whether fibers were introduced before or after the 45-day fermentation period, their presence is associated with a systematic reduction in compressive strength compared to unreinforced control specimens.

These findings challenge the prevailing assumption that synthetic reinforcement is universally beneficial for earthen masonry. Instead, the results underscore a critical incompatibility between inert, hydrophobic synthetic fibers and the biological mechanisms of traditional clay fermentation. The reduction in strength suggests that PP fibers are likely to interrupt the continuous biopolymer network established by decomposing straw, acting as defects rather than reinforcements. Consequently, this research contributes a vital caveat to the field of sustainable construction: the modernization of traditional adobe bricks through synthetic additives must account for the delicate biochemical processes that govern the matrix’s cohesion. Blindly transferring reinforcement techniques from inert engineering soils to biologically active traditional mixes is inadvisable without modifying the fiber–matrix interface.

6.2. Recommendations

- Based on the findings and the identified limitations of this investigation, the following recommendations are proposed to guide future research and practice.

- Future Research Directions

- Future studies should employ Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to visualize the micro-scale interaction between the hydrophobic PP fibers and the fermented clay–straw matrix. Such imaging would provide clearer insight into how fiber hydrophobicity interrupts the biopolymer bonding produced by straw decomposition.

- To address the incompatibility observed in this study, investigations should test the efficacy of chemically treating PP fibers (e.g., plasma treatment or coating) to increase their hydrophilicity and adhesion capability within a wet, fermented clay matrix.

- Detailed biochemical analysis is required to quantify how the presence of synthetic fibers affects the metabolic activity of microorganisms during straw fermentation. Research should determine if specific fiber materials inhibit the production of stabilizing biopolymers.

- Research should explore biocompatible synthetic fibers or alternative natural fibers that possess the durability of polymers but do not disrupt continuity of fermentation.

- Implications for Practice and Policy

- Practitioners utilizing traditional fermentation methods for Salmani architecture projects should prioritize traditional straw reinforcement. Synthetic fibers should only be introduced if the mix design is not fermented or if specific adhesives are used to ensure bonding.

- Regulatory bodies and code developers should work towards establishing testing standards that differentiate between “inert stabilized earth” (e.g., cement-stabilized) and “biologically stabilized earth” (e.g., fermented adobe), as the reinforcement requirements for each differ significantly.

- For projects requiring the durability of PP fibers, field trials should focus on minimizing fiber length and optimizing mixing protocols to prevent the agglomeration observed in this study, ensuring that the structural integrity of the brick is not compromised by processing defects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Y.A. and H.A.A.; Methodology, A.Y.A. and H.A.A.; Validation, H.A.A.; Formal analysis, A.Y.A., K.A. and A.A.A.; Investigation, A.Y.A.; Data curation, A.Y.A., K.A. and A.A.A.; Writing—original draft, A.Y.A.; Writing—review and editing, A.Y.A., K.A., H.A.A. and A.A.A.; Visualization, A.Y.A., K.A. and A.A.A.; Supervision, H.A.A.; Project administration, A.Y.A., K.A. and A.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to thank Ongoing Research Funding Program, (ORFFT-2025-147-1), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for financial support.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ongoing Research Funding Program, (ORFFT-2025-147-1), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PP | Polypropylene |

| SA | Saudi Arabia |

| MPa | Megapascal |

| ADR | Advanced Digital Readout |

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| IBC | International Building Code |

References

- Houben, H.; Guillaud, H. Earth Construction: A Comprehensive Guide; Intermediate Technology Publications: Rugby, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Silveira, D.; Varum, H.; Costa, A.; Martins, T.; Pereira, H.; Almeida, J. Mechanical properties of adobe bricks in ancient constructions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 28, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minke, G. Earth Construction Handbook: The Building Material Earth in Modern Architecture; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bertelsen, I.M.G.; Belmonte, L.J.; Fischer, G.; Ottosen, L.M. Influence of synthetic waste fibres on drying shrinkage cracking and mechanical properties of adobe materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 286, 122738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.; Uddin, N. Experimental analysis of compressed earth block (CEB) with banana fibers resisting flexural and compression forces. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2016, 5, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, P.J. Strength and erosion characteristics of earth blocks and earth block masonry. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2004, 16, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guettala, A.; Abibsi, A.; Houari, H. Durability study of stabilized earth concrete under both laboratory and climatic conditions exposure. Constr. Build. Mater. 2006, 20, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millogo, Y.; Morel, J.-C.; Aubert, J.-E.; Ghavami, K. Experimental analysis of pressed adobe blocks reinforced with Hibiscus cannabinus fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 52, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaou, N.M.L.; Thuo, J.; Kabubo, C.; Gariy, Z.A. Performance of polypropylene fibre reinforced laterite masonry bricks. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2021, 9, 2178–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazıcı, M.F.; Keskin, N. Zeminlerin doğal ve sentetik lifler ile güçlendirilmesi üzerine bir derleme çalışması. Erzincan Üniv. Fen Bilim Enst. Derg. 2021, 14, 631–663. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D422-63(2007)e2; Standard Test Method for Particle-Size Analysis of Soils. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2007; Reapproved 2016.

- ASTM C67/C67M-24; Standard Test Methods for Sampling and Testing Brick and Structural Clay Tile. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- Laborel-Préneron, A.; Aubert, J.E.; Magniont, C.; Tribout, C.; Bertron, A. Plant aggregates and fibers in earth construction materials: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 111, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labiad, Y.; Meddah, A.; Beddar, M. Performance of sisal fiber-reinforced cement-stabilized compressed-earth blocks incorporating recycled brick waste. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2023, 8, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajerani, A.; Hui, S.-Q.; Mirzababaei, M.; Arulrajah, A.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Abdul Kadir, A.; Rahman, M.T.; Maghool, F. Amazing types, properties, and applications of fibres in construction materials. Material 2019, 12, 2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).