Abstract

Despite growing interest in positive-energy and net-zero-energy buildings (NZEBs), few studies have addressed the integration of biobased construction with building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) under hot–dry climate conditions, particularly in Morocco and North Africa. This study fills this gap by presenting a simulation-based evaluation of energy performance and renewable energy integration strategies for a residential building in the Fes-Meknes region. Two structural configurations were compared using dynamic energy simulations in DesignBuilder/EnergyPlus, that is, a conventional concrete brick model and an eco-constructed alternative based on biobased wooden materials. Thus, the wooden construction reduced annual energy consumption by 33.3% and operational CO2 emissions by 50% due to enhanced thermal insulation and moisture-regulating properties. Then multiple configurations of the solar energy systems were analysed, and an optimal hybrid off-grid hybrid system combining rooftop photovoltaic, BIPV, and lithium-ion battery storage achieved a 100% renewable energy fraction with an annual output of 12,390 kWh. While the system incurs a higher net present cost of $45,708 USD, it ensures full grid independence, lowers the electricity cost to $0.70/kWh, and improves occupant comfort. The novelty of this work lies in its integrated approach, which combines biobased construction, lifecycle-informed energy modelling, and HOMER-optimised PV/BIPV systems tailored to a hot, dry climate. The study provides a replicable framework for designing NZEBs in Morocco and similar arid regions, supporting the low-carbon transition and informing policy, planning, and sustainable construction strategies.

1. Introduction

The 2015 Paris Agreement, adopted by 196 signatories under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), established an ambitious global mandate to limit the increase in global temperatures to well below 2 °C above preindustrial levels [1]. This commitment underscores the urgency for transformative energy planning and systemic changes to effectively combat climate change. Achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 is a pivotal milestone, as outlined in the International Energy Agency (IEA) Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector [2].

Buildings account for a substantial share of global energy use and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, positioning the sector as a critical driver of climate change mitigation [3]. Therefore, reducing the environmental footprint of the built environment requires a coordinated international response. Among the most influential strategies is the concept of net zero energy building (NZEB), which defines buildings whose annual energy demand is balanced by renewable generation [4,5]. Beyond lowering emissions, NZEBs represent a paradigm shift in sustainable construction and urban planning.

Complementing this approach, the International Energy Agency (IEA) promotes the concept of zero carbon buildings, which are designed to adapt to evolving user needs while maximising efficiency in energy, materials, and space [6,7]. Closely related is the zero-energy building (ZEB) paradigm, which integrates renewable energy technologies to offset annual consumption [8]. These principles have been embedded in European policy through EU regulations on nearly-zero energy buildings, catalysing advances in energy efficient design and the widespread adoption of solar technologies [9]. More recently, the scope has expanded from single buildings to zero energy districts, which emphasize systemic energy interactions on the urban scale to achieve even greater performance [10].

A further evolution is positive energy building (PEB), which produces more energy annually than it consumes. PEBs are evaluated using Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs), where the energy labels range from ‘A’ (high efficiency) to “G” (high consumption) [11]. Originating from the success of low-energy buildings (Bâtiment Basse Consommation, BBC), the PEB concept gained traction through initiatives such as the Énergie-Carbone (E+C-) standard [12,13]. Although natural gas was initially considered a transitional energy source, the contemporary PEB design increasingly relies on renewable energy technologies and advanced engineering solutions [12].

Central to the success of PEB is bioclimatic architecture, which takes advantage of local environmental conditions to optimise the comfort of the occupant and reduce mechanical energy demand [14]. Strategies include optimised orientation, careful site selection, high-performance glazing, solar-shading devices, and compact building forms to minimise losses [15]. Passive measures such as solar heating, natural ventilation, and improved thermal insulation further decrease the reliance on active mechanical systems, while the integration of renewable energy sources strengthens overall sustainability [16].

Meeting global net-zero goals requires deep reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and large-scale investments. The IEA estimates that fossil fuel demand must decline by over 25% by 2030 and by approximately 80% by 2050, while clean energy investment must rise from 1.24% of global GDP in 2020 to approximately 2.05% annually between 2025 and 2050—equivalent to 44.8–47.3 trillion USD [17,18]. The achievement of this transition depends on technological innovation and robust policy frameworks. Breakthroughs in carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) and green hydrogen will be crucial, as nearly half of the required emission reductions by 2050 rely on technologies still in development [19]. Currently, governments must implement policies that phase out unabated fossil fuels, incentivise renewable-energy deployment, and promote electrification in all sectors [20].

Ultimately, global cooperation is indispensable. International initiatives such as Mission Innovation and Clean Energy Ministerial underscore the importance of multilateral collaboration for technology transfer, coordinated investment, and policy harmonisation [21,22]. Together, these efforts frame the pathway to a decarbonized building sector and a resilient, net-zero future.

Despite these global advances, knowledge gaps remain for Morocco and the wider North African region, where the combined application of biobased construction, building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPV), and positive or net-zero energy building (NZEB) strategies in hot–dry climates is still rarely documented. Existing local studies typically focus on the thermal performance of single construction materials or the standalone deployment of rooftop photovoltaic (PV) systems, leaving limited evidence on how integrated bioclimatic design and BIPV solutions can be scaled to full-building or district contexts.

Furthermore, synergies between BIPV and passive design measures are underexplored, despite growing international recognition that hybrid approaches, such as combining BIPV façades with green roofs and other vegetative envelopes, can simultaneously enhance thermal performance and moderate peak cooling loads [23,24]. Similarly, the potential of BIPV to mitigate the effects through surface-energy balance and façade shading remains not adequately studied [25].

Addressing these gaps is especially critical for Morocco, where hot–dry climatic zones cover nearly 60% of the territory and where national low-carbon strategies call for replicable and cost-effective NZEB/PEB solutions. To respond, the present work sets out the following research questions:

- Material impact: How do biobased wood construction materials influence operational energy demand and carbon emissions compared to conventional masonry in a representative Moroccan hot–dry context?

- Renewable integration: What technoeconomic configuration of rooftop photovoltaic and BIPV systems can achieve net zero or positive energy performance when coupled with energy storage and intelligent management?

- Design framework: How can passive bioclimatic strategies and active renewable systems be integrated into a replicable design methodology suitable for residential buildings and adaptable to urban scale applications?

In this context, this study contributes a first-of-its-kind framework for Morocco and North Africa by integrating three key dimensions that are rarely combined in regional NZEB/PEB research: (i) detailed climatic characterisation and passive bioclimatic design tailored to a hot–dry context, (ii) a life-cycle carbon accounting that captures operational emissions, and (iii) techno-economic optimisation of photovoltaic and building-integrated photovoltaic (PV/BIPV) systems using the HOMER platform.

By coupling these elements, the research generates high-resolution energy and carbon benchmarks for a representative Moroccan city (Fes) and provides a replicable methodology that can guide national NZEB standards, district-scale zero-energy planning, and renewable-integration strategies across North Africa. This integrated approach establishes the study’s novel contribution to both scientific understanding and practical implementation of positive-energy building concepts in climates and markets that remain under investigated.

2. Review of the Literature and Research Gaps

2.1. Review of the Literature

2.1.1. Evolution of Positive Energy and Net Zero Energy Buildings

NZEBs and PEBs have seen a remarkable conceptual and technological evolution since their initial formulation. Early studies have mainly addressed the energy balance at the level of individual buildings [26]. However, recent advances have considerably broadened this perspective, shifting from isolated energy-efficient structures to integrated urban systems that address climate resilience, energy justice, and environmental sustainability on the district and city scales [27]. One of the most significant developments in this domain has been the transition from single NZEBs to positive energy districts (PEDs) [28]. This evolution is driven by the growing complexity of urban energy needs and the recognition that localised, building-level solutions are insufficient to meet broader climate goals [29]. Smart grid integration has played a pivotal role in this transformation. For example, foundational work on decentralised energy-sharing has explored how distributed control and cluster-based management can enhance the integration and schedulability of renewable energy in distribution networks [30]. This initiative demonstrates how blockchain-enabled peer-to-peer trading can boost renewable energy utilisation by 36% [31]. Furthermore, the Horizon Europe PED Programme is currently funding 38 demonstration cities to explore innovative governance and business models for urban energy positivity [32]. Complementing these developments are advances in multivector energy systems, which integrate thermal, electrical, and hydrogen storage networks to improve renewable energy penetration and energy autonomy. Recent simulations suggest that combining these energy carriers can achieve up to 91% renewable integration at the district scale [33]. A prominent example is the Helsinki Digital Twin project [34], which achieved 72-h energy autonomy through AI-optimised management of second-life EV batteries, seasonal storage of thermal energy storage, and building-integrated proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzers. These technologies collectively support dynamic energy balance and resilience in the face of grid fluctuations and supply interruptions. Simultaneously, climate-adaptive building design has become a central feature of next-generation NZEB and PEBs. The Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [35] underscores the need to update the NZEB standards to account for more frequent and severe climate extremes. In response, initiatives such as [36,37] integrate high-performance phase change material (PCM) facades capable of reducing cooling loads by up to 40%, adaptive ventilation systems responsive to wet-bulb temperatures, and flood-adapted ground floor designs collectively redefining the boundaries of passive and active climate resilience in building envelopes.

Despite these advances, several persistent challenges remain. Performance gaps continue to plague many NZEB implementations; approximately 68% of projects perform less than 15% relative to predicted energy performance metrics [38]. Emerging digital twin technologies offer promising solutions. These systems can reduce performance gaps to below 5% by employing real-time Bayesian calibration, machine learning models for predicting occupant behaviour, and autonomous fault detection and diagnostics [39]. In parallel, the environmental burden of construction materials, particularly embodied carbon, is receiving increasing attention. Consequently, embodied emissions account for 55 to 70% of the environmental impacts during the life cycle of NZEBs [40]. Recent innovations such as mycelium-based insulation materials, which are both carbon-negative and thermally efficient, as well as robotic deconstruction technologies that achieve up to 89% material recovery [41], are paving the way toward a circular construction economy.

Another critical dimension is social equity. Studies indicate that only 18% of the NZEB benefits currently reach low-income or marginalised populations [42], raising concerns about distributive justice in energy transitions. However, new models are emerging to address this imbalance. Barcelona’s Energy Commons (2024) initiative allows the community to own the renewable energy infrastructure, promoting both energy autonomy and inclusivity [43].

Looking to the future, the field is expanding beyond the pursuit of energy neutrality to embrace regenerative and biologically integrated design principles. Biohybrid buildings, exemplified by microalgae facades, are capable of sequestering up to 120 kgCO2/m2/year while contributing to thermal performance and daylight modulation [44]. This expansive trajectory underscores the transition of NZEBs and PEBs from technical energy accounting exercises to holistic, multidimensional platforms for sustainable urbanism. To fully realise its transformative potential, future research must adopt transdisciplinary methodologies that integrate behavioural economics (for example, occupant engagement), advanced manufacturing (for example, adaptive materials), and climate justice frameworks that ensure equitable access and benefit sharing. The continued convergence of technological innovation, policy reform, and inclusive design marks a new era for the built environment, one that not only meets energy goals but redefines the social and ecological roles of buildings in a rapidly changing world.

2.1.2. Bioclimatic Architecture and Passive Design Strategies

Bioclimatic architecture has gained traction as a sustainable approach to building design, utilising local environmental resources for natural heating, cooling, and ventilation [45]. Recent studies [46] demonstrated the effectiveness of passive solar design, building orientation, and thermal insulation in reducing energy demand by up to 40%. However, the scalability of these strategies in high-density urban environments remains uncertain. Researchers have explored the application of bioclimatic principles in African climates, revealing challenges in balancing thermal comfort and energy efficiency due to high humidity levels [47,48]. This highlights the need for location-specific adaptations and innovations in passive design strategies.

2.1.3. Integration and Life Cycle Assessment

Integration of renewable energy sources, such as photovoltaic systems and wind turbines, is essential to achieve the energy-positive status of PEB [49]. Several studies emphasise the role of advanced photovoltaic technologies, including bifacial solar panels, in improving energy generation efficiency [12,50]. Similarly, hybrid renewable systems, which combine solar and wind energy, have been shown to provide stable energy supplies for NZEB and PEB [51]. Technological innovations, particularly in energy management systems, have further advanced PEB. The application of machine learning models for predictive energy optimisation and demand-response strategies has been explored in recent studies [52]. Machine learning algorithms have been shown to reduce energy consumption in smart buildings by up to 15% [53], although their application in PEB remains limited. Although the operational energy performance of Nearly Zero Energy Buildings (Nearly ZEBs) and PEBs has been extensively studied, life cycle assessments (LCAs) focussing on embodied carbon remain less explored but increasingly critical. Recent research underscores that embodied carbon emissions associated with material extraction, manufacturing, transportation, construction, maintenance, and end-of-life stages constitute a significant and growing portion of the total carbon footprint, particularly as operational energy efficiency improves [54,55]. Embodied carbon can contribute to approximately 50% or more of the total carbon emissions of a building in the lifecycle carbon emissions of high-performance structures, with the predominant share coming from the material production and construction phases of the materials [56]. These initial emissions are irreversibly determined at the start of construction, underscoring the critical importance of mitigation strategies during the early design stage.

In response, the latest LEED v5 certification standards (2025) now require comprehensive lifecycle carbon assessments, requiring embodied carbon reductions through material substitutions, design optimisation, and circular economy strategies such as reuse and recycling [57]. This observation is consistent with existing research, which demonstrates that applying the principles of circular economy, including the use of recycled and biobased materials, the design for disassembly (DfD), and the adoption of low carbon materials such as cross-laminated wood (CLT) and geopolymer concrete can reduce embodied carbon emissions by 30–60% in both commercial and residential buildings [58,59]. Furthermore, recent advances in life cycle assessment (LCA) methodologies have improved the precision of embodied carbon throughout the life cycle of buildings, enabling data-driven material selection and optimised decarbonisation strategies [60,61].

2.2. Research Gap

Despite notable advances in the development of energy-efficient buildings, research on Net Zero Energy Buildings (NZEBs) in Morocco and the broader North African region continues to exhibit critical gaps. Notably, there is a scarcity of research focused on scaling NZEB and positive energy building concepts from individual buildings to broader urban districts. This gap is particularly evident in terms of assessing the economic feasibility and social acceptance of zero-energy districts within these contexts [62]. Existing regional studies often neglect comprehensive lifecycle assessments and embodied carbon assessments, particularly overlooking the role of ecological construction approaches that can substantially reduce embodied emissions while enhancing long-term building performance under the unique climatic variability of North African environments [63]. Additionally, the adaptation of bioclimatic architectural principles to the diverse and resource-constrained climates of North Africa remains underexplored, limiting optimal design strategies that could improve building resilience and energy efficiency [64]. Furthermore, the integration of renewable energy technologies at the district level known as zero energy districts remains underexplored, particularly in terms of their economic feasibility, technical challenges and social acceptance [65]. Secondly, the prevailing research focus remains on technical solutions like efficiency measures and renewable energy systems [66,67], often neglecting holistic lifecycle assessments that account for embodied carbon in materials and durability under future climate scenarios. Furthermore, the application of bioclimatic architecture is limited by a lack of research on its adaptation for diverse climates and resources-constrained settings [68]. Finally, the utilisation of advanced computational methods, such as machine learning, for predictive energy management in positive energy buildings remains a nascent and inadequately explored field.

Recent advances in sustainable building have widened technological, socioeconomic, and regulatory gaps. AI-based energy optimisation suffers up to 30% efficiency loss from algorithmic bias, a risk that federated learning can mitigate by enabling decentralised model training while preserving data privacy [69,70]. Integration of nanomaterials also introduces concerns related to environmental toxicity, requiring the implementation of rigorous certification standards, such as those defined by EU-OSHA [71]. From a socioeconomic perspective, approximately 78% of contractors lack proficiency in advanced sustainable construction methods, a gap that can be addressed through immersive virtual reality (VR) training platforms [72]. Furthermore, the increased rental costs associated with nearly ZEB, averaging 23% above conventional buildings, underscore the need for targeted subsidies to improve affordability [73]. On the regulatory front, the rise of quantum computing presents new cybersecurity threats to energy infrastructures, prompting the adoption of post-quantum cryptographic protocols. Additionally, the absence of harmonised NZEB standards has led to inconsistencies between regions, a challenge partially addressed by the introduction of ISO 21931-2:2024 [74,75,76]. (Table 1). Addressing these interconnected challenges is imperative for the effective and equitable advancement of sustainable building frameworks.

Table 1.

Emerging Challenges and Research Gaps [74,75,76].

2.3. Description and Methodology

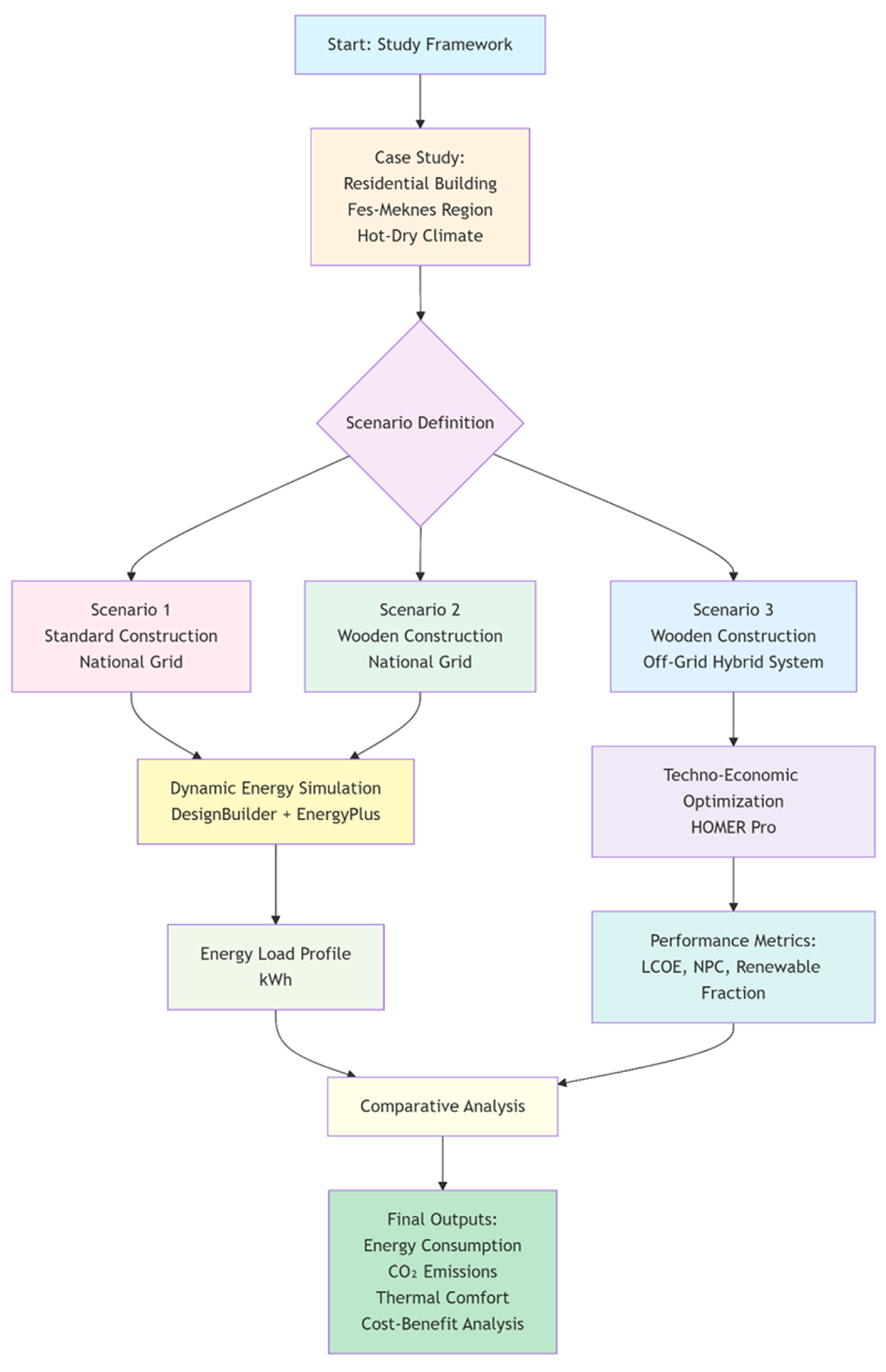

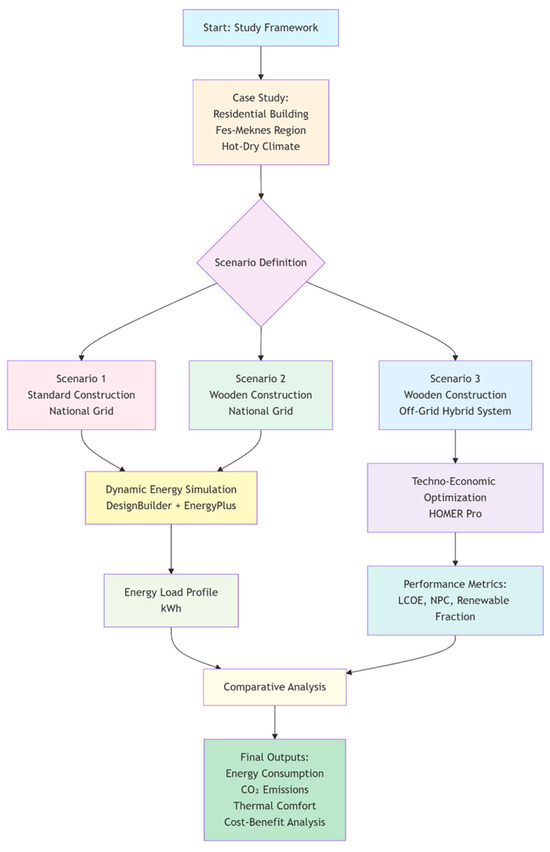

This study employs a comprehensive, multistage simulation framework to assess the energy performance and renewable energy integration potential of a residential building in the Fes-Meknes region. The methodology, visually summarised in Figure 1, integrates architectural modelling, climatic analysis, dynamic energy simulation, and techno-economic optimisation to evaluate three distinct scenarios.

Figure 1.

Research flow and methodology framework.

A detailed architectural model of the Africa Golden Riyad project was developed, based on realistic geometric, construction, and operational data. Three scenarios were defined and simulated:

- Scenario 1: Standard Construction with Grid Supply

Represents a typical Moroccan residential building constructed with concrete and brick, exclusively connected to the national electrical grid. This baseline scenario reflects common urban housing practices without the integration of renewable energy technologies.

- Scenario 2: Eco-Constructive Wooden Building with Grid Supply

Models a building using wood-based construction systems with high-performance insulation, maintaining connection to the national grid. This scenario evaluates the impact of passive design and low carbon construction materials on energy consumption without introducing energy generation on-site.

- Scenario 3: Wooden Construction with Integrated Photovoltaic/BIPV Systems

Builds on Scenario 2 by integrating photovoltaic and BIPV systems for on-site electricity generation. This configuration was further simulated using HOMER Pro to model hybrid energy system performance and assess energy self-sufficiency and load management potential.

For all scenarios, energy simulations were conducted on an hourly basis over a full year to quantify total electricity and gas consumption (in kWh), identify seasonal demand patterns, and assess the benefits of construction alternatives and integration of renewable energy on overall building performance.

The following subsections detail each step of this integrated approach.

2.3.1. Simulation Approach and Case Study Selection

The evaluation of modern building performance increasingly relies on sophisticated computational tools that have been thoroughly tested and validated through scientific research. These Building Performance Simulation (BPS) tools allow for an integrated analysis of buildings across all stages of the life cycle, from early design to operational use. Contemporary BPS platforms are capable of modelling not only energy consumption, but also more intricate aspects such as occupant usage patterns and various comfort domains. Selecting the appropriate simulation tool is a vital methodological step, and recent studies propose structured evaluation criteria based on both technical features and user expectations. Among the leading options, DesignBuilder is frequently selected by architects and engineers due to its powerful EnergyPlus-based engine, user-friendly interface, and comprehensive modelling capabilities.

In this work, we adopted a dynamic simulation approach to evaluate the energy performance of the Africa Golden Riyad residential project under different design and operation scenarios. Simulations were carried out using DesignBuilder to assess the influence of architectural layout, material characteristics, and local climate data. The modelling process also included the integration of renewable technologies, specifically photovoltaic (PV) and building-integrated photovoltaic (BIPV) systems, alongside energy storage components, to explore potential self-sufficiency gains. The regional focus of the study was guided by a climatic classification of Morocco, where hot-arid zones dominate almost 60% of the national land area. The city of Fes was selected as a representative case due to its typical environmental conditions and its relevance to the local construction context.

2.3.2. Data Collection and Climatic Analysis

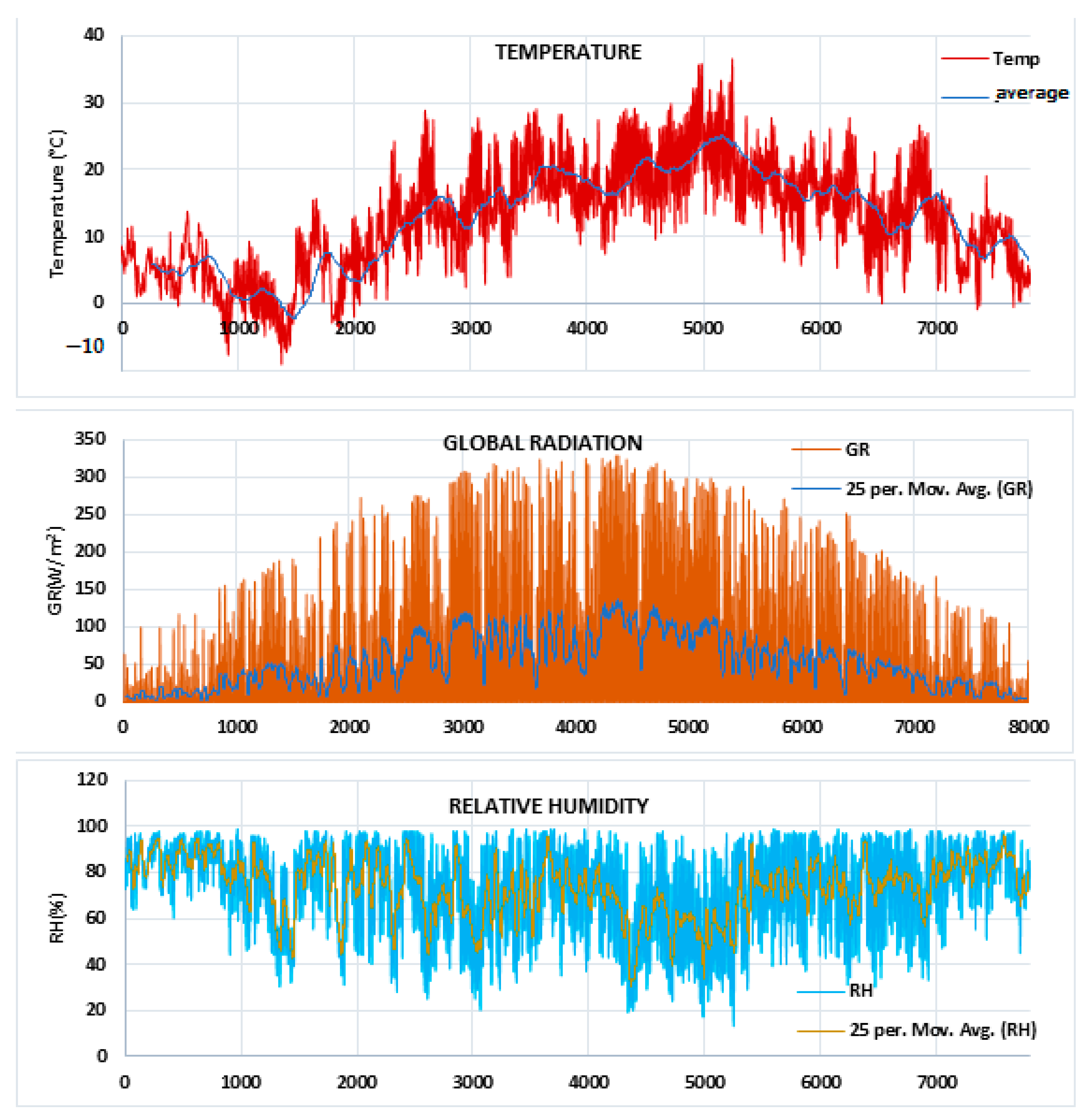

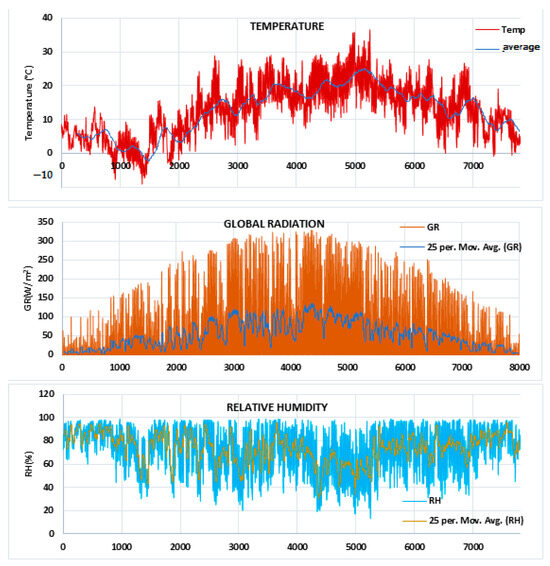

Accurate and representative climatic data are essential to evaluate building energy performance under realistic conditions. In this study, Fes, Morocco (34.0° N, 5.0° W), was selected as the reference location due to its well-documented meteorological profile and representativeness for much of Moroccan territory. Meteonorm 7.1 software was used to provide high-resolution data on solar irradiation, dry-bulb temperature, and relative humidity, which formed the inputs for dynamic thermal simulations. According to the Köppen–Geiger classification. Fes falls within the BSh (hot semi-arid) zone, marked by pronounced seasonal contrasts: hot, dry summers with peak temperatures around 36 °C in August and high solar radiation, and cold winters with temperatures dropping to approximately 4 °C in January [77]. Degree-day analysis (base 18 °C) yielded 1025 heating degree days and 1480 Cooling Degree-Days, confirming cooling as the dominant challenge and underscoring the importance of passive strategies (e.g., natural ventilation, thermal insulation, solar control) alongside active systems (HVAC, photovoltaic and BIPV). The region’s high solar potential (≈5.4 kWh/m2/day) underscores the economic and technical feasibility of renewable integration [78]. Integrating local climate data with material, design, and operational inputs improved the precision of the simulation, supporting energy efficient and climate-responsive architecture for the hot–dry conditions of North Africa’s hot–dry conditions. Figure 2 shows monthly variations in solar irradiation, ambient air temperature, and relative humidity.

Figure 2.

Climatic data profiles for the city of Fes.

2.3.3. Building Description and Simulation Scenarios

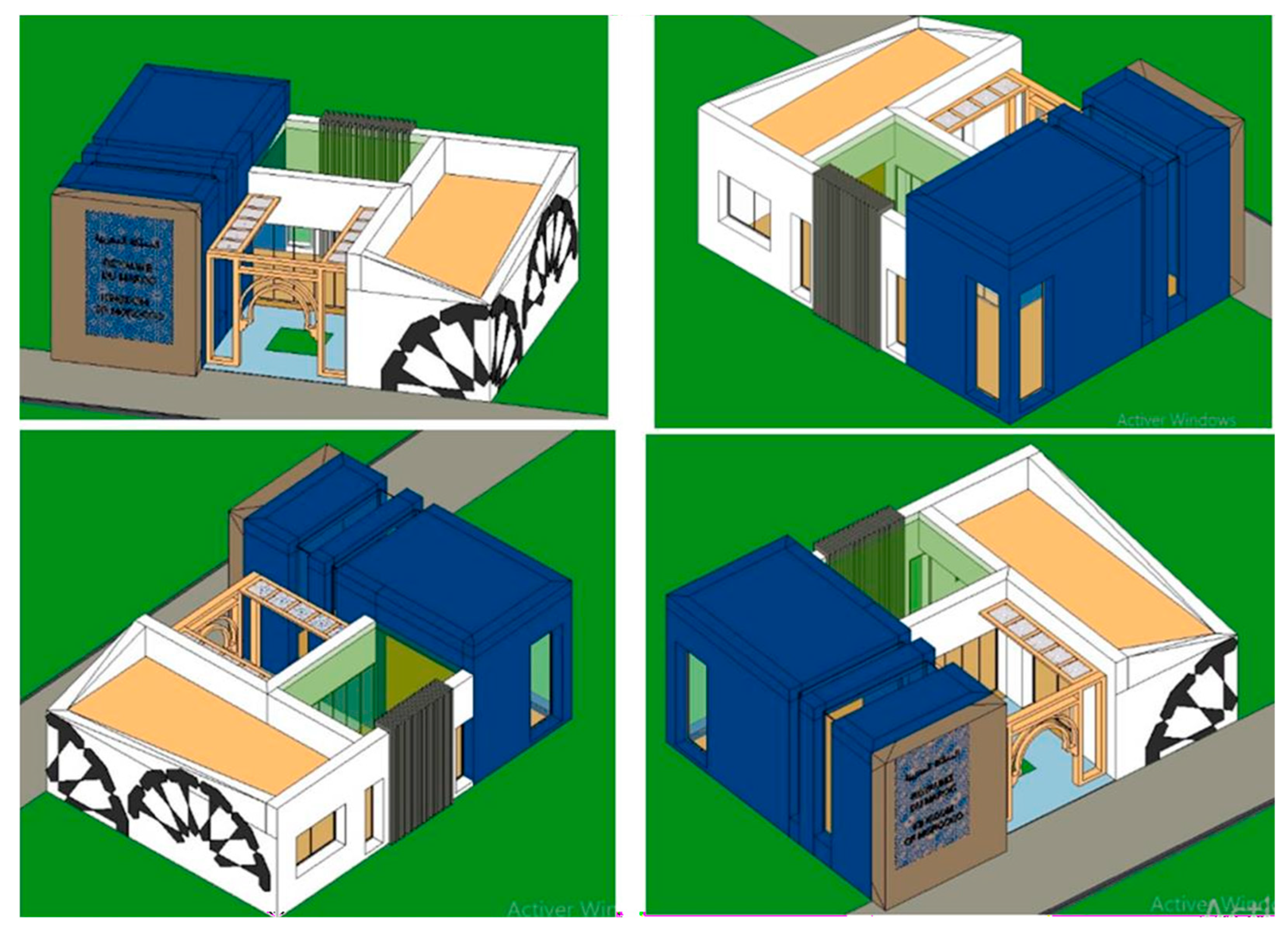

The Africa Golden Riyad project was digitally modelled using DesignBuilder Version 4, a comprehensive building performance simulation platform powered by the EnergyPlus engine. The modelling process incorporated detailed three-dimensional geometry, internal spatial layouts, and HVAC zoning to accurately reflect the operating characteristics of the building. Additionally, site-specific topographic and geographic data were integrated to simulate the environmental interactions between the building envelope and its immediate surroundings. This high-fidelity digital model provided a robust foundation for conducting dynamic energy simulations under realistic conditions.

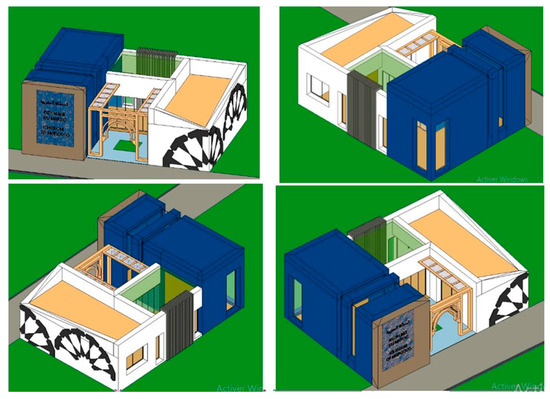

To ensure geometric accuracy and visual validation, a series of architectural renderings were generated using ArchiCAD. These 3D visualisations, illustrated in Figure 3, depict various internal and external perspectives of the building and were used to verify structural integrity and volumetric consistency within the simulation environment.

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional model of Riyad building.

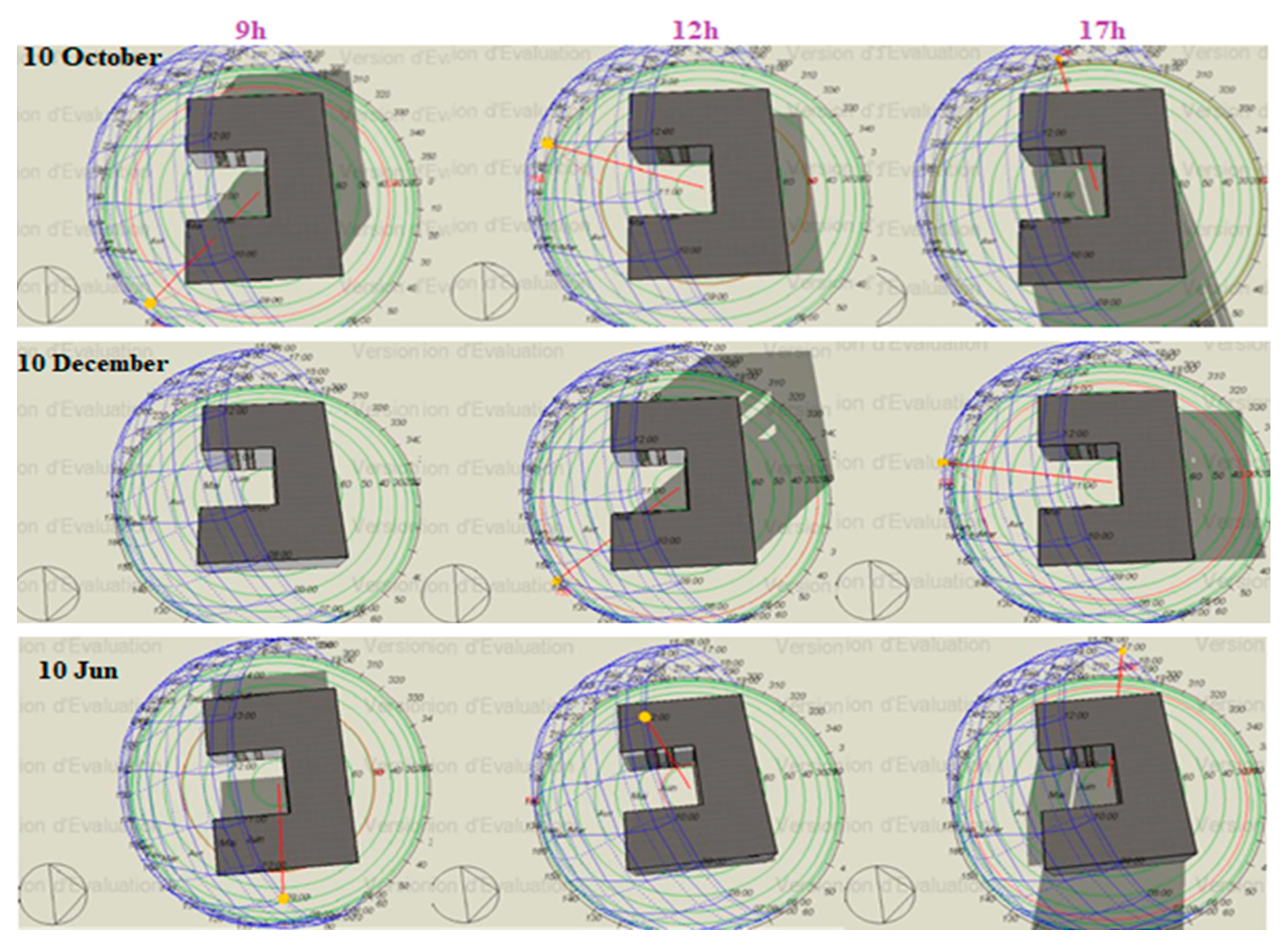

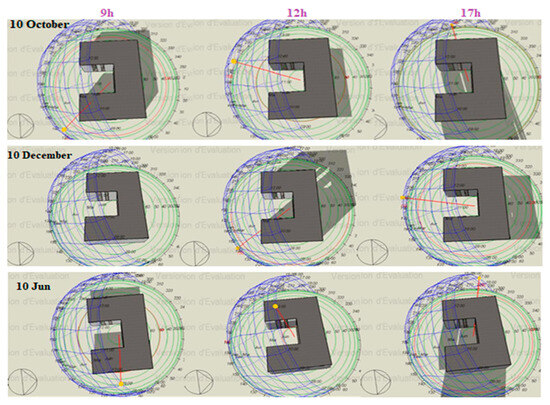

As part of the energy performance analysis, a solar path study was performed to quantify solar exposure across different seasons. This analysis evaluated the trajectory and its interaction with the façades on three representative dates. 10 October, 10 December, and 10 June, corresponding to the mid-season, winter, and summer periods, respectively. For each date, the solar incidence was evaluated at three key times (9:00 AM, 12:00 PM, and 5:00 PM) to capture daily variation in the solar gain (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Solar path analysis for the Riyad building.

The results revealed seasonal fluctuations in solar radiation, highlighting the critical role of passive solar strategies, including optimised window orientation, external shading devices, and thermal mass, in minimising heating and cooling loads. These insights informed the development of energy-efficient design alternatives tailored to the local climate. The combination of advanced 3D modelling and seasonal solar analysis allowed for a comprehensive scenario-based evaluation of the energy behaviour. This methodological framework supports the identification of design interventions that improve energy efficiency and climate response, particularly under the hot–dry climatic conditions of the Fes-Meknes region.

To evaluate the energy performance of the Africa Golden Riyad project under varying construction methods and energy strategies, three distinct scenarios were developed and simulated. These scenarios were designed to reflect a progression from standard building practices to advanced energy-efficient and environmentally sustainable solutions. Each scenario incorporated specific material properties, construction techniques, and operational assumptions aligned with regional practices and international standards. The simulations were supported by inputs from the energy modelling that comply with Moroccan thermal regulations.

Scenario 1: Standard Construction with Grid Electricity Supply

This baseline scenario represents a conventional residential building typical of the urban areas of Morocco. The structure was modelled using standard construction techniques, primarily employing concrete and brick as building materials. These materials are prevalent due to their availability, durability, and relatively low initial cost. The energy needs were fully met through a connection to the national electricity grid, without integrated renewable energy systems. The thermal envelope was characterised by moderate insulation and relatively high thermal transmittance values, contributing to elevated heating and cooling loads throughout the year. Table 2 summarises the physical and thermal properties of the construction materials used in this model, including the walls, roof, ground floor, and windows, along with their respective thermal transmittance (U values), convective and radiative heat transfer coefficients, and surface resistances.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Standard Construction Material Model 1.

Scenario 2: Eco-Constructive Model Using Sustainable Materials

The second scenario introduces an eco-constructive approach, employing wood-based construction techniques. Wood, a renewable and low carbon material, provides superior natural thermal insulation compared to conventional masonry systems. This scenario was designed to reduce the environmental impact and energy consumption of the building while maintaining a connection to the national electricity grid to ensure operational reliability.

The building envelope was designed using bioclimatic principles, incorporating layered wall assemblies with rock wool insulation, high-performance roof insulation, and double-glazed low-emissivity windows. These enhancements significantly reduced the thermal transmittance of all envelope elements, resulting in improved indoor thermal comfort and reduced HVAC demand. Table 3 presents detailed thermal specifications of the eco-constructive materials used in this scenario.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Model 2 Eco-Constructive Material.

Scenario 3: Positive Energy Building with Integrated Photovoltaic and BIPV Systems

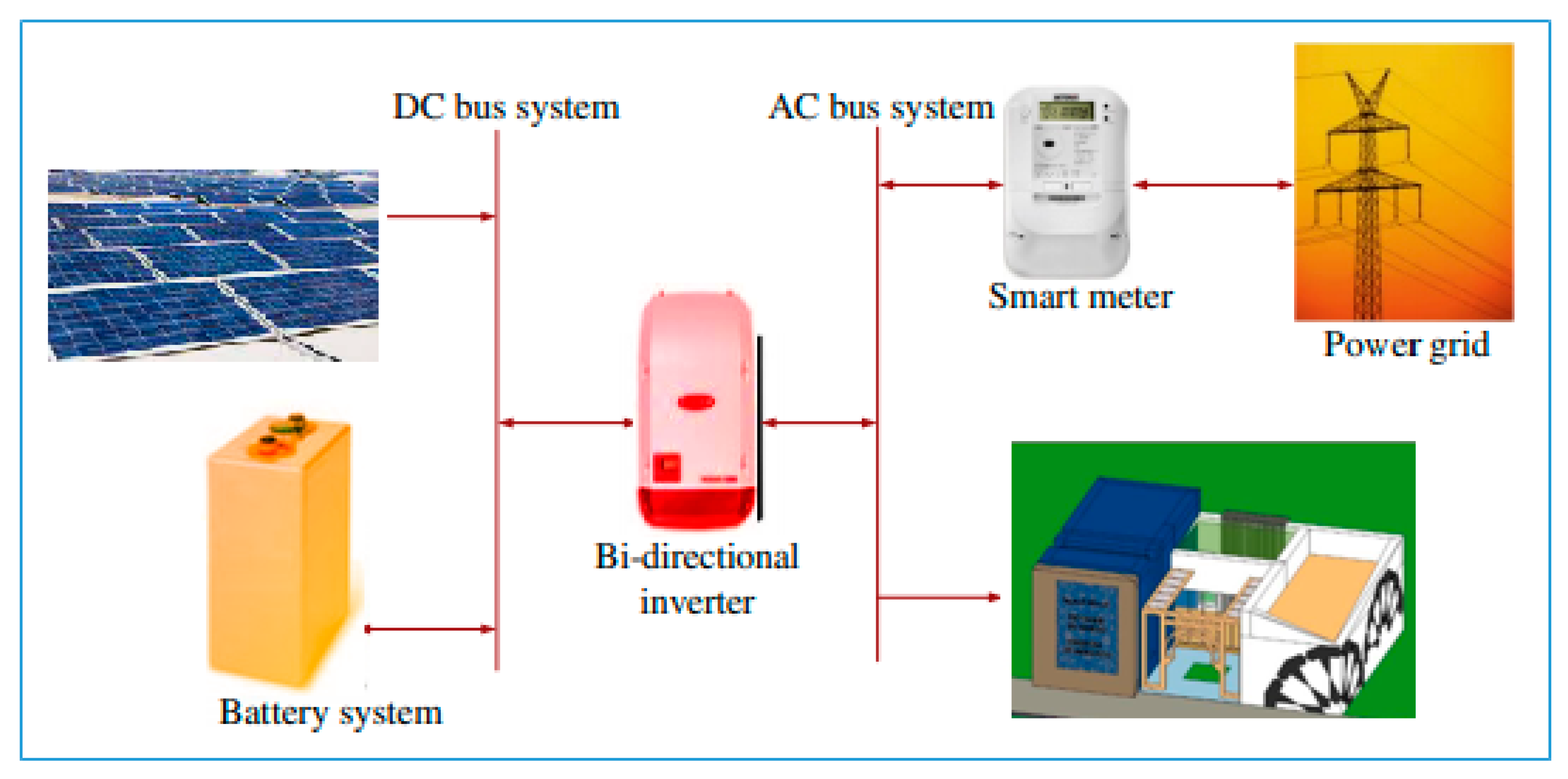

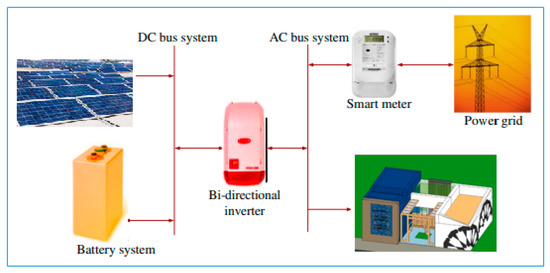

The third and most advanced scenario extends the eco-constructive measures of Scenario 2 by combining bioclimatic design with on-site renewable generation to achieve a positive-energy building (PEB). Photovoltaic (PV) and building-integrated photovoltaic (BIPV) arrays are paired with battery storage and intelligent energy management, as modelled in HOMER Pro (Figure 5). Construction is based on sustainably sourced wood and passive measures optimal orientation, enhanced natural ventilation, and high-performance insulation so that active PV generation operates on a reduced load base, allowing net-zero or surplus energy performance under Moroccan climatic conditions. Annual residential load profiles, including hourly peak demand, were modelled with typical meteorological year (TMY) data gathered from regional stations and cross-validated by spatial triangulation. The HOMER mixed-integer optimisation was constrained by:

Figure 5.

Hybrid proposed system for Golden Riyad building.

- Battery ageing: a cycle life model assuming 80% end-of-life capacity and a 4% annual degradation rate.

- Economic parameters: real discount rate of 5% and 25-year project horizon.

- Reliability targets: 98% minimum renewable fraction and 1% probability of loss of load.

The optimisation minimised the total net present cost (NPC) while meeting these reliability and degradation constraints. The results show that a photovoltaic on-grid configuration with limited storage yields the lowest levelized cost of energy (LCOE), while batteries remain essential for nighttime autonomy and grid-outage resilience.

In addition to using wood as the main construction material, this scenario emphasises passive design strategies, such as optimal building orientation, improved natural ventilation, and the use of high-performance insulation. These features work in synergistic ways with active photovoltaic systems to significantly reduce dependence on external energy sources and potentially generate surplus energy, positioning the building toward net zero or positive energy performance. This scenario demonstrates the potential for sustainable construction to meet both comfort and environmental goals within the Moroccan context.

Using Hybrid Multiple Energy Resource Optimisation (HOMER) v4.10 software, the applied loads were the annual consumption of residential buildings taking into account the consumption in peak hours, while the climatic data for the different regions are collected and processed by triangulation. The results showed that the PV-On-grid are more suitable; when configured with the lowest current net cost (CNP) and LCOE, the use of batteries will be critical to ensure night-time power supply.

The following Table 4 summarises the assessment of technology components.

Table 4.

Specifications of the photovoltaic system.

2.4. Annual Energy Load Assessment

To assess energy demand in all three scenarios, simulations were carried out using a consistent set of baseline parameters for occupancy, internal heat gain, lighting and equipment loads, and thermal comfort setpoints, as defined by the ASHRAE 90.1 standards and Moroccan building regulations.

The simulation assumed an average occupant density of 0.11 persons/m2, with internal heat gains from occupants estimated at 120 W/person. Lighting and equipment loads were modelled at 5 W/m2 and 7 W/m2, respectively. The thermal set points were fixed at 20 °C for heating and 26 °C for cooling, in accordance with national guidelines. The window-to-wall ratio (WWR) was assumed to be 20% on the south, east and west façades, and 30% on the north façade, to reflect realistic Moroccan residential design practices.

Both infiltration and mechanical ventilation rates were modelled at 1 air change per hour (ACH), ensuring adequate indoor air quality and consistent simulation conditions in all scenarios. These baseline inputs are summarised in Table 5, which details the standardised assumptions for annual energy demand and forms the basis for comparing the performance outcomes of the three scenarios.

Table 5.

Baseline Parameters for Annual Building Energy Demand Simulation.

3. Results

3.1. Hygrothermal Performance of Alternative Construction Systems

This section presents a detailed comparative analysis of the hygrothermal behaviour of two construction scenarios: the conventional concrete-based structure (Scenario B1) and the eco-constructed wooden alternative (Scenario B2). Using dynamic simulation in an annual cycle (8760 h), significant differences were observed in thermal buffering and humidity control, both of which directly influence energy performance and indoor environmental quality.

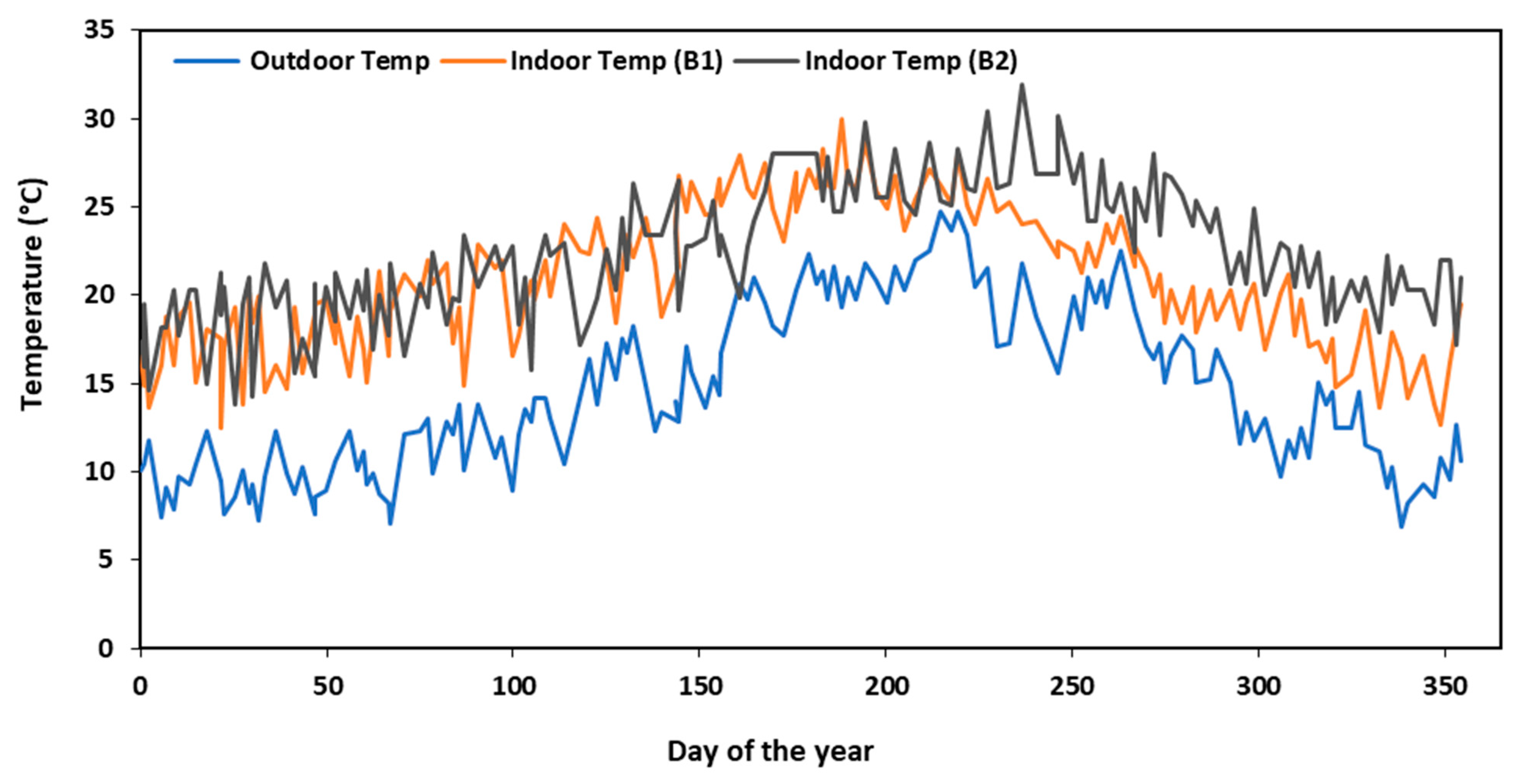

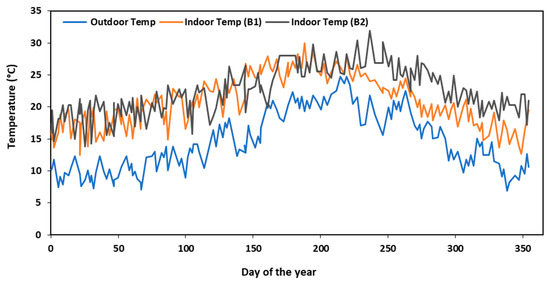

Figure 6 illustrates the annual profiles of outdoor and indoor air temperatures for both scenarios. During the winter months (December to February), Scenario B1 exhibited higher thermal volatility, with diurnal temperature swings averaging 4.2 °C wider than those observed in B2. The wooden structure maintained 2.1 °C higher minimum indoor temperatures, providing improved thermal comfort during cold periods. This performance is attributed to the enhanced thermal inertia of the wood, which delays heat transfer. Temperature fluctuations from the exterior took approximately 8.7 h to influence indoor conditions in B2, compared to only 5.2 h in B1. During the summer season (June to August), the wood construction also demonstrated superior thermal performance. It achieved a maximum indoor temperature attenuation of 3.8 °C, significantly exceeding the conventional structure, which managed only 1.2 °C. Furthermore, the heat dissipation was more gradual in the wooden building, with cooling rates averaging 0.4 °C per hour, half the rate observed in the concrete structure (0.8 °C/h). These findings underscore the ability of the wooden envelope to moderate heat gains and losses more effectively.

Figure 6.

Comparison of Indoor Temperature Regulation under Two Scenarios Relative to Outdoor Conditions.

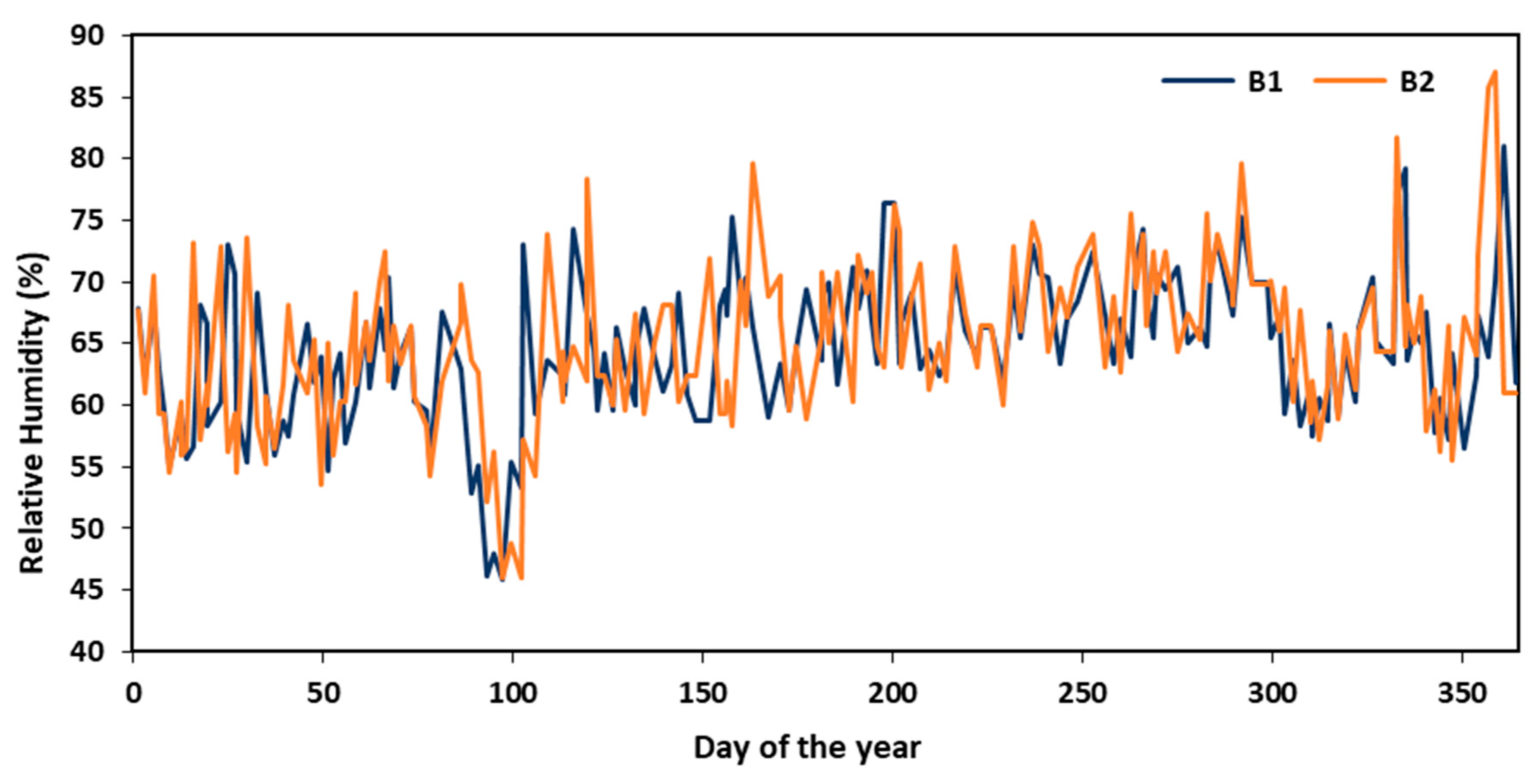

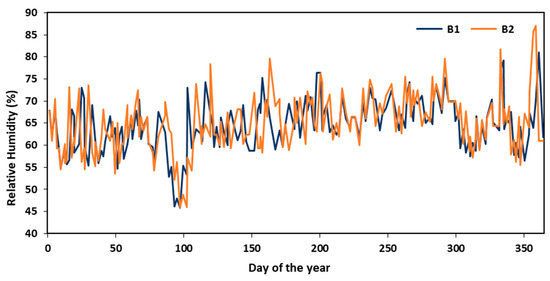

In terms of humidity regulation, Figure 7 compares the annual variation in relative humidity between both models. Although the mean annual difference in humidity between the two scenarios was marginal (approximately 1%), this difference had notable implications for comfort. Scenario B2 maintained the relative humidity within the optimal 40–60% range for 83% of the occupied hours, compared to only 74% in Scenario B1. This improvement translated into a 9% increase in annual thermal comfort hours equivalent to approximately 790 additional hours, determined by adaptive comfort modelling.

Figure 7.

Comparison of Indoor Relative Humidity Control in Two Scenarios.

The superior performance of Scenario B2 stems from the hygroscopic nature of the wood, which actively regulates the humidity at home. Furthermore, the improved indoor humidity control in scenario B2 had perceptible benefits for the occupants. According to simulated indoor air quality metrics, the wooden construction achieved a mean olfactory comfort rating of 2.1, compared to 1.7 in the conventional building, indicating a better perceived freshness and comfort.

Therefore, these results underscore the value of treating temperature and humidity as interdependent parameters when evaluating building energy performance. The wooden construction system not only improves thermal regulation, but also improves indoor environmental quality, making it particularly suitable for semi-arid climates such as that of the Fes-Meknes region.

3.2. Comparative Performance Analysis of Construction Systems

This section presents a comparative analysis of two building typologies conventional construction using concrete and brick, and Eco construction using wood based on dynamic energy simulations. The aim was to evaluate the performance of each model in terms of energy consumption, carbon emissions, thermal comfort, and economic feasibility. Simulations revealed substantial differences between the two approaches, underscoring the benefits of transitioning to biobased, thermally efficient construction systems.

In terms of energy performance, the wooden construction model (Scenario 2) showed a 33.3% reduction in annual energy consumption compared to the conventional model (Scenario 1), consuming approximately 100 kWh/m2/year versus 150 kWh/m2/year. This reduction is statistically significant and is attributed to improved envelope insulation, lower thermal transmittance (U-value 0.9 W/m2·K versus 1.8 W/m2·K), and better regulation of indoor thermal conditions. Furthermore, peak cooling loads were reduced by almost 38.5% in the wooden model, highlighting its ability to passively regulate indoor environments during periods of high external temperatures.

Environmental performance also improved markedly in the wooden construction scenario. Operational CO2 emissions were halved, decreasing from 50 kg/m2/year in the conventional model to 25 kg/m2/year in the wooden model. Furthermore, a cradle-to-gate assessment of embodied carbon indicated a 62.5% reduction in construction-related emissions. The use of renewable materials, together with a lower electricity dependency (reduced by 50% for heating and 57% for cooling), contributes to a significantly lower environmental footprint. The wooden building also showed reduced contributions to the effect of the urban heat island, with a surface temperature difference (ΔTsurface) of 3.2 K compared to the standard structure. From an economic perspective, although the wooden construction model involves a higher initial investment estimated at $80,000 compared to $70,000 for the conventional model, the life cycle analysis demonstrates long-term financial advantages. The annual energy cost is reduced by 33.3%, resulting in projected 20-year savings of approximately $ 15,000. When evaluated over the full lifespan of the building, the wooden construction scenario exhibits a positive net present value after 12.7 years, assuming a discount rate of 5%. Furthermore, the enhanced thermal efficiency of the building envelope allows for downsized HVAC systems, translating into 25% to 30% lower capital expenditures on mechanical systems (Table 6). Beyond quantifiable performance metrics, the wooden construction model presents additional qualitative advantages. It allows quicker construction times to be up to 28% shorter and provides increased seismic resilience due to the superior ductility of wood structures (ductility factor μ = 4.1). Furthermore, wood-based interiors are associated with biophilic benefits, including improved occupant well-being and productivity increases of 12 to 15%, according to findings in the literature.

Table 6.

Comparative analysis of standard vs. Wooden Construction: Energy, Environmental, and Economic Performance.

3.3. Annual and Monthly Energy Consumption Analysis

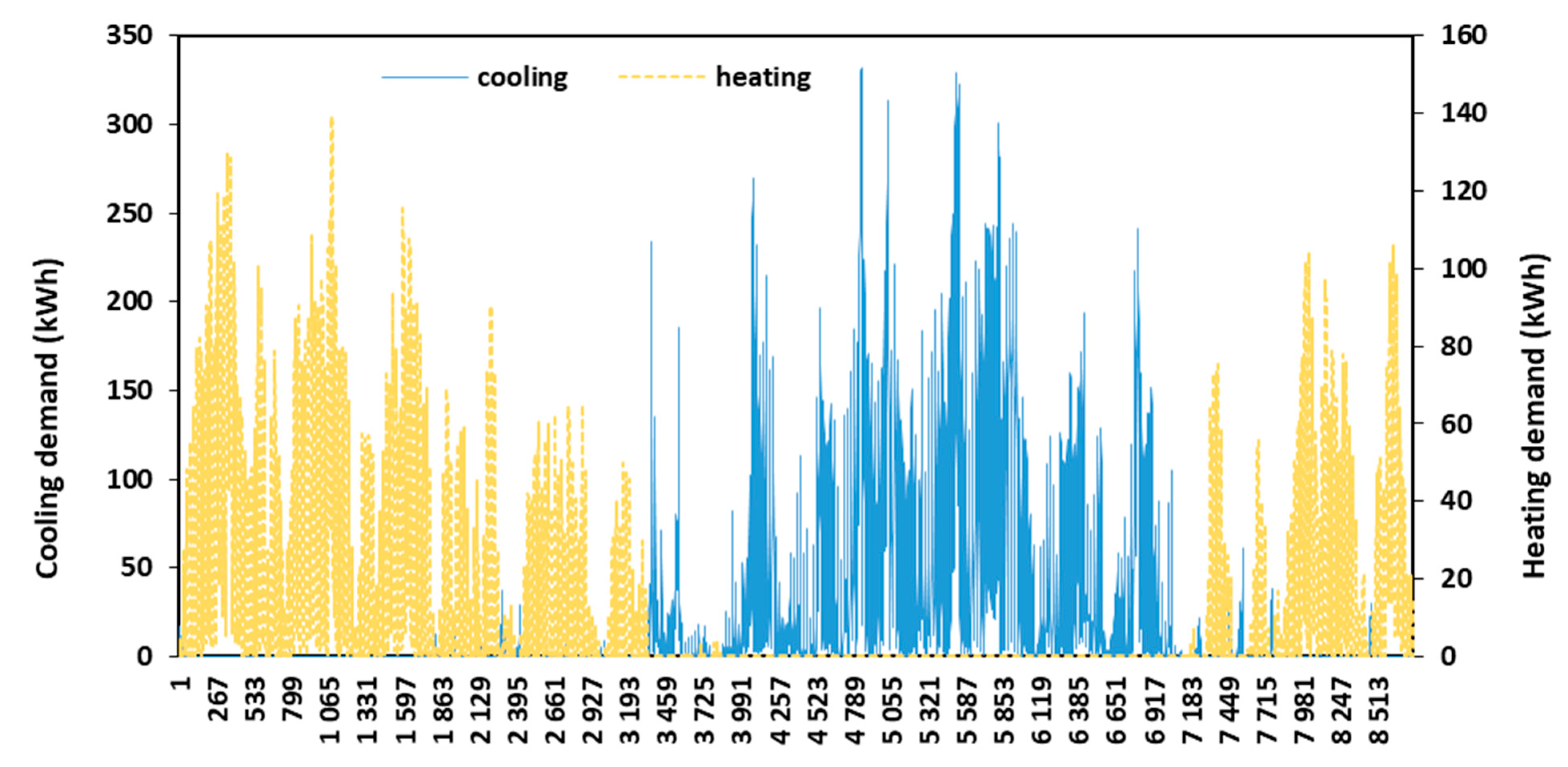

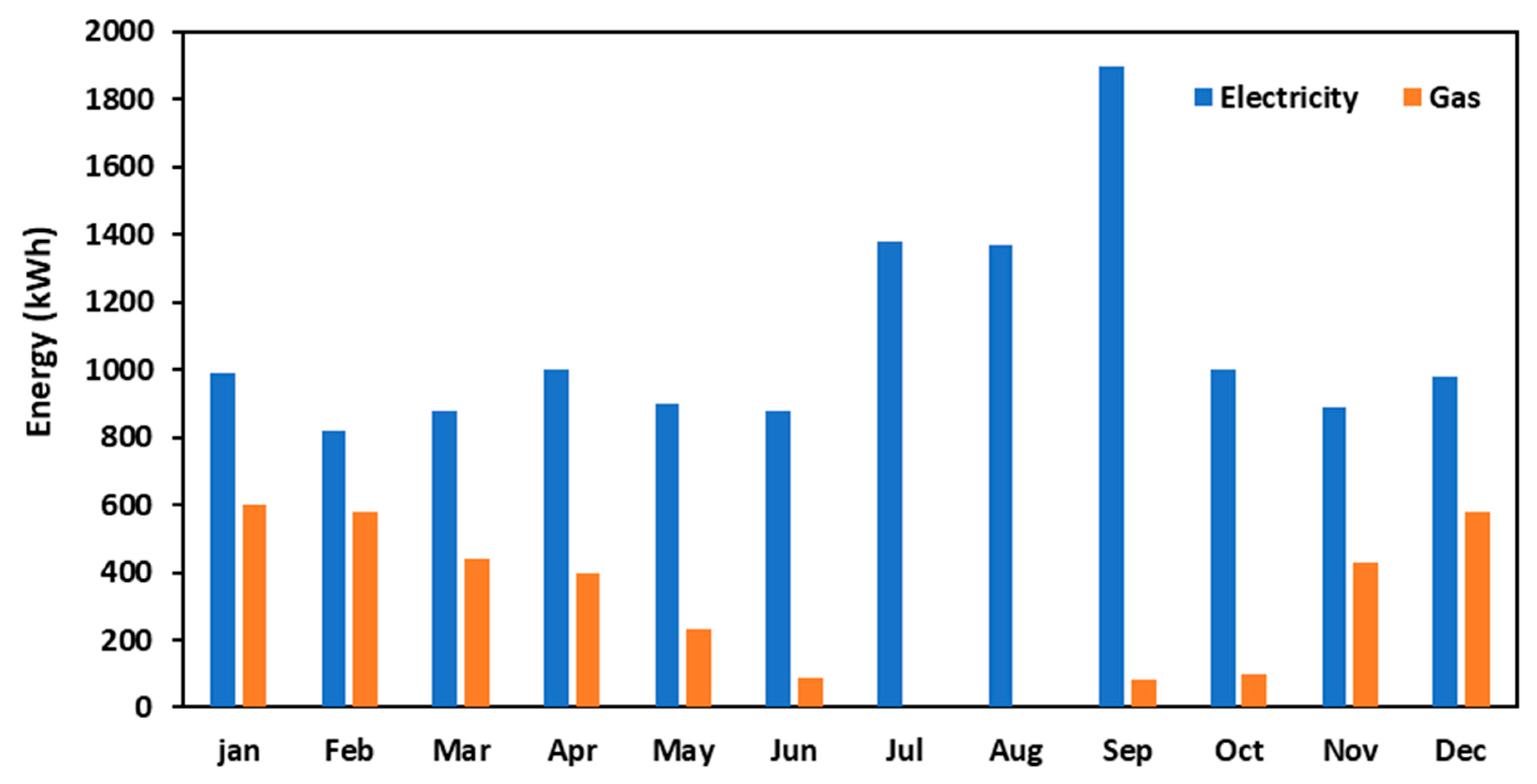

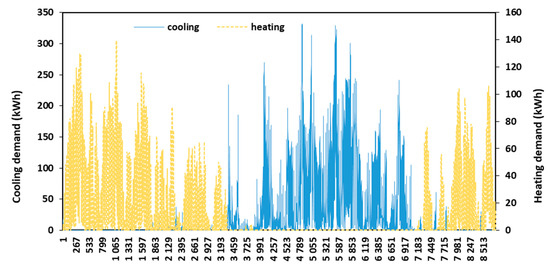

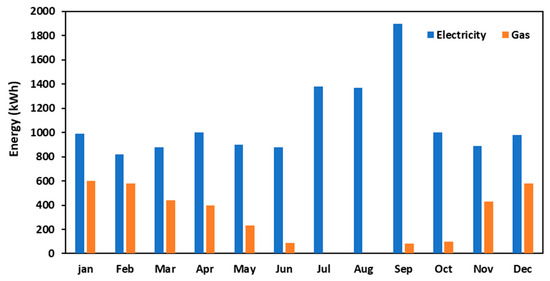

Based on the construction parameters and operational data defined in the previous sections, dynamic simulations were performed to estimate the total annual energy consumption of the building, expressed in kilowatt hours (kWh). The results provide a detailed breakdown of the monthly energy use by end use categories, including lighting, heating, cooling, domestic hot water (DHW) and room-specific electricity demand. Figure 8 illustrates the monthly distribution of electricity consumption across building systems and spaces. The variation reflects both seasonal climatic conditions and occupancy-driven internal loads. Higher electricity usage was observed during the summer months (June–August) due to increased demand for cooling, while lighting and equipment loads remained relatively constant throughout the year. In particular, during the winter period (December–February), electricity consumption also increased, primarily due to space heating requirements in areas not served by gas heating.

Figure 8.

Annual cooling and heating consumption in (kWh) for scenario 2.

To provide a holistic view of the energy profile, Figure 9 presents the total monthly energy consumption disaggregated by electricity and natural gas usage. The data reveal complementary consumption patterns between the two energy sources: While electricity demand peaks during midsummer (July and August), gas consumption reaches its maximum in winter months (January and February), consistent with the use of gas for space heating and domestic hot water production. The highest electricity demand is recorded in July and August, with values of 1383.53 kWh, mainly due to intensive cooling loads. In contrast, gas consumption in these months drops to minimal levels (as low as 3.29 kWh in August), indicating a minimal need for heating. On the contrary, January shows elevated gas consumption (622.59 kWh) and lower electricity demand (968.47 kWh), illustrating the seasonal energy balance between both systems. These patterns emphasise the importance of thermal envelope performance and integration of the energy system to optimise annual energy loads.

Figure 9.

Annual energy load of gas and electricity (Scenario 2).

Overall, the data indicate a strong seasonal dependence of energy use, with electricity dominating in the hot months and gas in cold months. These findings support the need for integrated energy management strategies that take advantage of seasonal resources such as photovoltaic electricity production in summer and minimise the use of fossil fuels during winter through improved insulation and efficient heating technologies.

The next sections will analyse how Scenario 3, which integrates PV and BIPV systems, can mitigate these loads, increase energy autonomy, and reduce annual operating costs and emissions.

3.4. Evaluation of the Proposed Off-Grid PV/BIPV Hybrid Energy System

This section presents the performance assessment and techno-economic analysis of various renewable energy system configurations explored in this study. The focus is on the proposed off-grid hybrid system, which integrates rooftop PV panels, BIPV modules, and battery energy storage to achieve complete autonomy from the electrical grid. This model was selected based on its ability to meet 100% of the annual energy demand while aligning with the sustainability and cost reduction objectives (Table 7). The configuration of the selected system includes 7.1 kW of rooftop photovoltaic energy, covering approximately 80% of the available roof area, and orientated south at a 15° tilt angle to optimise solar exposure. Additionally, 1.5 kW of BIPV panels are installed on the east, south, and west façades, allowing for more distributed and temporally diversified energy capture. The system is equipped with 9 kW inverters to convert direct current (DC) to alternating current (AC), and is supported by a lithium-ion battery storage system sized to ensure off-grid reliability and energy balance. The battery bank has a depth of discharge (DOD) of 80%, a charge/discharge efficiency of 95%, and a minimal self-discharge rate of 0.001%, with an operational lifespan estimated at 12 years. The simulation results indicate that the proposed hybrid system generates a total of 12,390 kWh/year, entirely from renewable sources. Of this, the rooftop photovoltaic system contributes approximately 92.6% (11,477 kWh/year), while the BIPV system accounts for the remaining 7.4% (913.5 kWh/year). Although the BIPV share is smaller, it plays a critical role in enhancing energy availability during early morning and late afternoon hours, complementing the output profile of the rooftop array and supporting daily load matching. Collectively, the system achieves a 100% renewable energy fraction, fully meeting the building’s annual electricity needs without dependence on the grid infrastructure. From an economic perspective, the system was evaluated on key financial indicators, including the Cost of Energy (COE) and the Net Present Cost (NPC) over the project life. The results show a COE of $0.705/kWh and a corresponding NPC of $45,708. Although these values are higher than those of grid-tied or partially renewable configurations, they reflect the premium required for full energy independence, long-term resilience, and reduced exposure to volatility in energy prices. Furthermore, the system eliminates ongoing power costs from the grid and reduces carbon emissions in the life cycle, offering long-term environmental and operational advantages.

Table 7.

Cost breakdown per energy system.

In comparison to alternative configurations examined in the study such as PV-only, BIPV-only, or PV/BIPV systems connected to the grid, the off-grid PV/BIPV/battery system emerges as the most sustainable and self-sufficient option (Table 8). For example, a PV-grid hybrid model reached a renewable fraction of only 47.2% and a lower COE of $0.116/kWh, but remained dependent on grid supply. Similarly, a BIPV/grid configuration achieved a modest 17.3% renewable contribution and the highest COE among the options evaluated ($0.177/kWh). Although these systems demonstrate lower initial capital costs, they do not provide complete autonomy or resilience, especially in regions with potential grid instability.

Table 8.

Comparative evaluation for different hybrid configurations.

To this end, the off-grid photovoltaic/BIPV hybrid energy system with battery storage offers a technically robust and environmentally sound solution for the Africa Golden Riyad building. It ensures uninterrupted renewable energy supply, aligns with national energy transition goals and supports Moroccan vision for carbon neutrality in the built environment. The feasibility is further strengthened by its scalability and potential integration into other residential and institutional buildings in regions with similar climatic and infrastructure profiles.

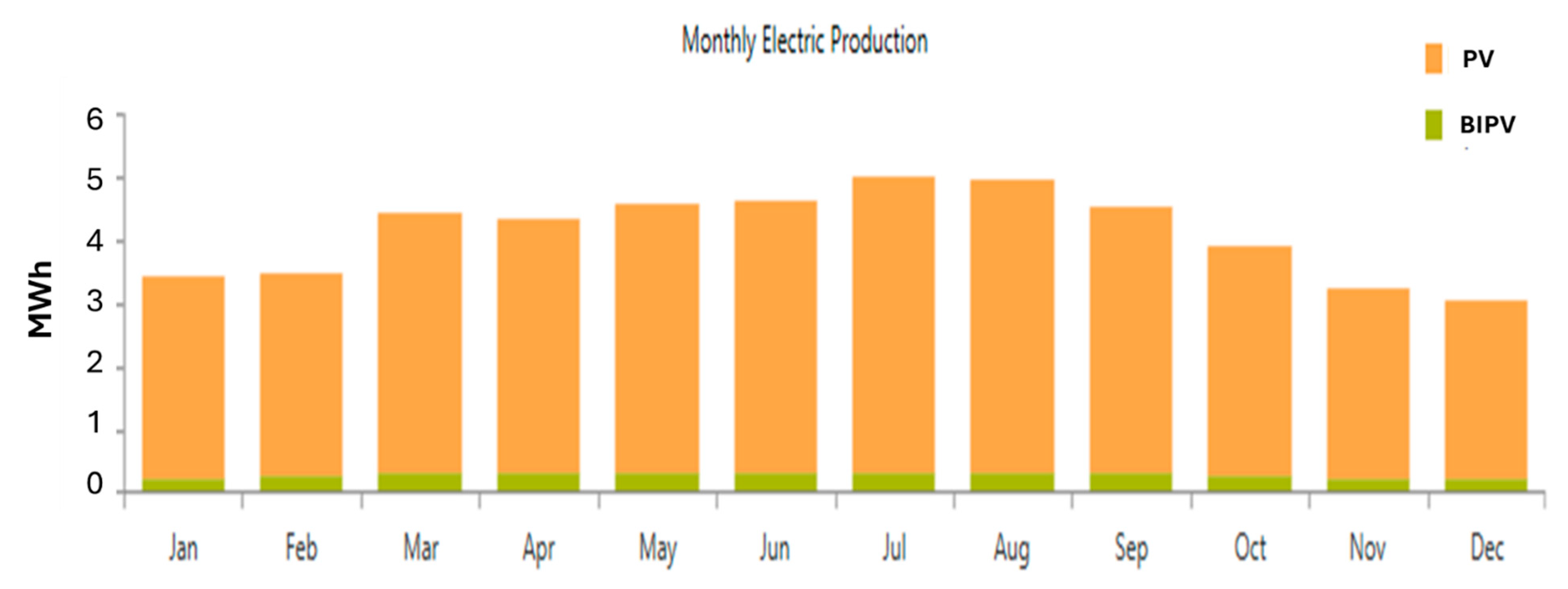

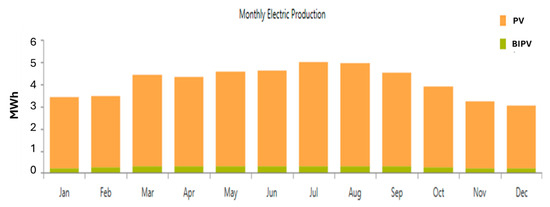

3.4.1. Monthly Electric Production

The monthly energy output of the proposed hybrid off-grid system, which comprises rooftop photovoltaic modules and BIPV elements, is presented in Figure 10, which illustrates the cumulative power generation profile throughout the calendar year. The production profile demonstrates a clear seasonal pattern, with higher generation levels observed during the summer months (May to August), coinciding with peak solar irradiance in the Fes-Meknes region. In contrast, lower production values are recorded during the winter months, reflecting the reduced availability of solar resources. A closer examination of the breakdown of the energy contribution reveals that the BIPV system represents approximately 12% of the total annual photovoltaic plant production. Although secondary in output compared to the rooftop PV array, BIPV modules provide a meaningful supplemental energy yield, particularly in early morning and late afternoon hours due to their diversified façade orientation (east, south, and west). This temporal distribution improves the overall energy availability profile and supports better load matching throughout the day. The integration of horizontal (rooftop PV) and vertical (BIPV façade) components not only increases the total generation surface but also improves the spatial and temporal utilisation of solar energy. This design strategy maximises energy capture throughout various sun angles, contributing to the system 100% renewable fraction and improving resilience in off-grid operation. Monthly production data confirm the reliability of the hybrid approach to meet residential energy needs under real-world climatic conditions.

Figure 10.

The accumulation of monthly power generation of the proposed hybrid system (PV/BIPV).

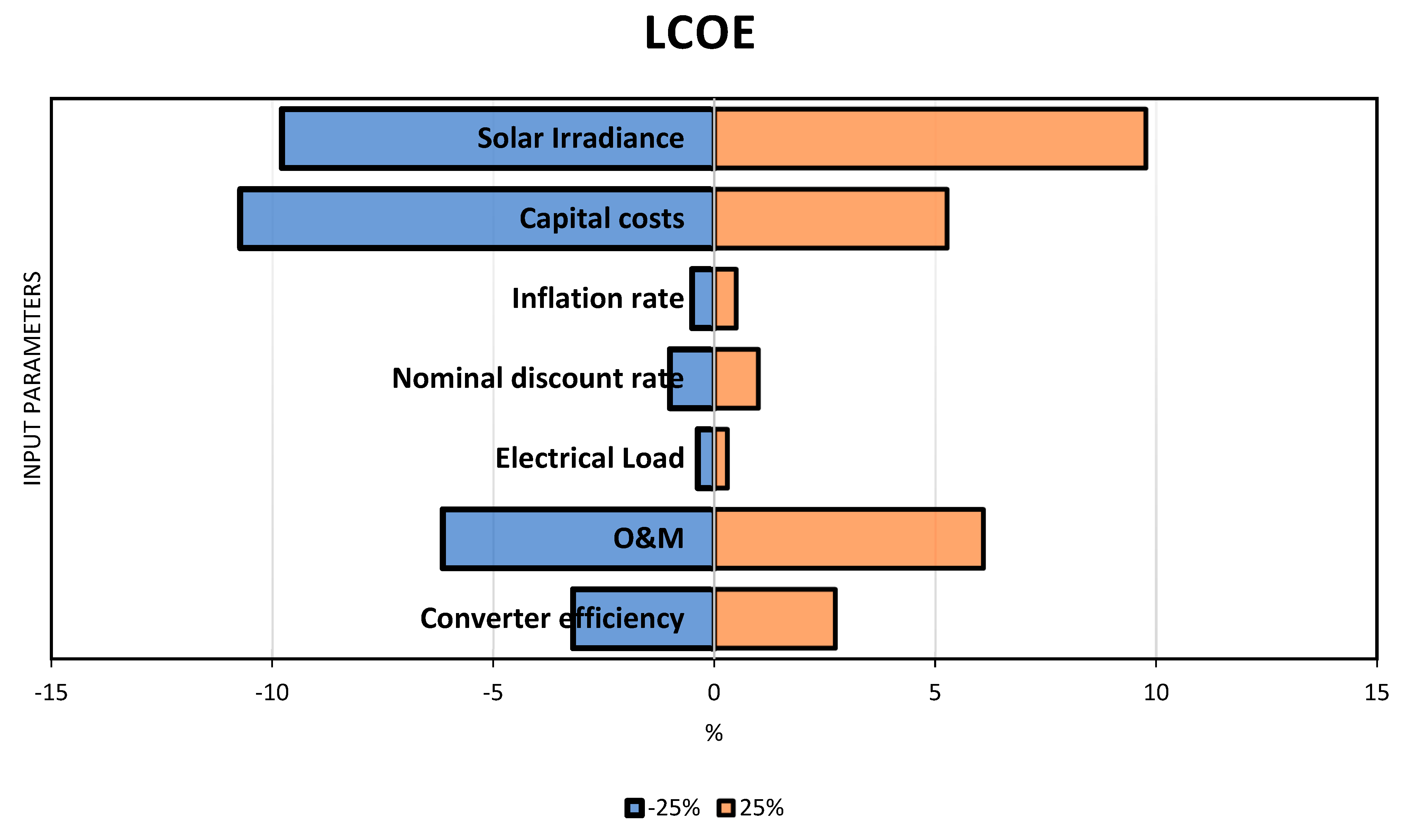

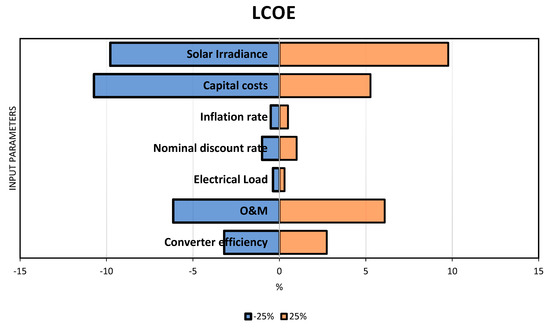

3.4.2. Sensitivity Analysis of LCOE

To assess the robustness of the proposed hybrid off-grid PV/BIPV/battery system and identify the most critical parameters influencing its economic performance, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. The Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCOE) was chosen as the central indicator, as it encapsulates the lifecycle cost per unit of electricity generated. Key technical, economic and environmental inputs were individually varied by ±25%, and the resulting percentage change in LCOE was recorded (Figure 11). The results reveal that solar irradiance and capital costs are the two most sensitive parameters affecting the LCOE, with absolute impact ranges of 19.55% and 16.00%, respectively. A 25% decrease in solar irradiance increases the LCOE by 9.78%, indicating that the system is highly dependent on optimal solar exposure. On the contrary, an equivalent increase in irradiance leads to a similar percentage decrease in LCOE, reinforcing the importance of accurate solar resource assessment during the project design phase. Capital costs also show a pronounced effect. A 25% increase in CAPEX raises the LCOE by over 5.27%, while a 25% reduction leads to a significant 10.73% decrease. This asymmetrical sensitivity underscores the importance of cost-effective procurement, particularly for photovoltaic modules, BIPV components, and battery storage systems. Operational and maintenance costs (O&M) costs rank third in influence, with a nearly symmetrical ±6% effect of 6% on LCOE. This suggests that minimising O&M through predictive maintenance strategies and system reliability enhancements can yield considerable economic benefits.

Figure 11.

LCOE sensitivity to the main inputs.

On the other hand, the converter. efficiency, the nominal discount rate, and the inflation rate exert moderate influence, with absolute variations ranging from 1% to 5.9%. These parameters, although not dominant individually, still contribute to overall financial performance and should be optimised through appropriate financial structuring and equipment selection. The electrical load showed the least impact, with variations in a demand change resulting in less than 0.4% of the LCOE. This low sensitivity reflects the resilience of the system design in accommodating load fluctuations within the expected operational range.

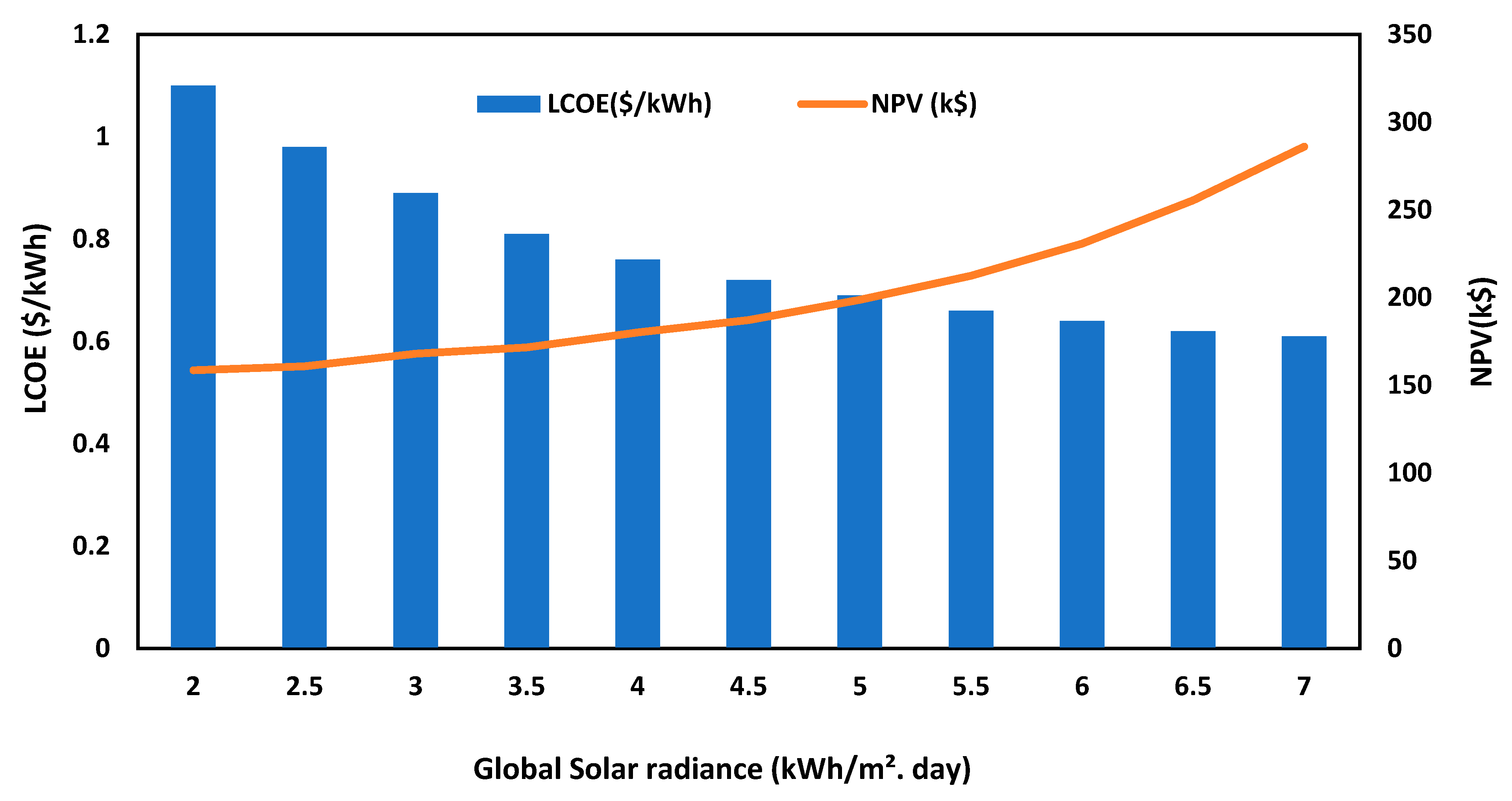

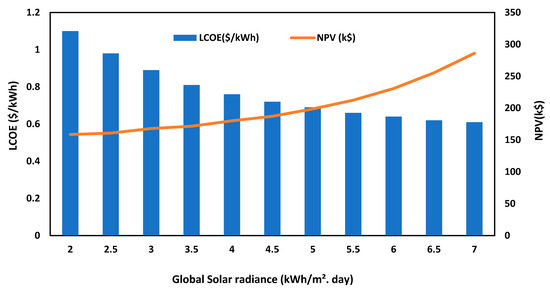

Figure 12 illustrates the sensitivity of the LCOE and the net present value (NPV) with respect to variations in average daily solar radiation ranging from 2 to 7 kWh/m2/day. This analysis reflects the economic response of the proposed off-grid PV/BIPV hybrid system to changing solar resource availability.

Figure 12.

Sensitivity of economic metrics to solar resources.

As solar irradiance increases, the LCOE shows a clear declining trend, falling from $1.10/kWh at 2 kWh/m2/day to just $0.61/kWh at 7 kWh/m2/day. This represents a 44.5% reduction in LCOE, highlighting the strong inverse correlation between the availability of solar resources and the cost of electricity generation. This trend is consistent with the economics of the photovoltaic system, where higher irradiance improves the energy yield, thus reducing the cost per kilowatt hour produced. The NPV of the system increases significantly, from $158.6 k at 2 kWh/m2/day to $286 k at 7 kWh/m2/day. This 80% increase in NPV confirms the improved profitability of the project with increased solar exposure. The slope of NPV growth increases beyond the 5.5 to 6 kWh/m2/day range, indicating that irradiance levels above this threshold result in accelerated financial returns.

3.5. Critical Limitations and Future Research Directions in Sustainable Construction

This study offers a comparative evaluation of conventional versus wood-based construction systems, providing meaningful information on their respective performance in terms of energy efficiency, environmental impact, and economic viability. However, several key limitations methodological, geographic, environmental, and economic constrain the generalizability and depth of the conclusions drawn. Addressing these limitations through a more integrative and multidisciplinary research framework is essential for advancing sustainable construction practices. One of the primary methodological limitations of the current study lies in its reliance on static input parameters to model energy consumption and carbon emissions. This approach overlooks the inherently dynamic nature of building performance, which is influenced by time-dependent factors such as fluctuations in occupant behavior, gradual degradation of mechanical systems, and site-specific microclimatic interactions. The absence of these dynamic variables introduces a risk of discrepancy between simulated outputs and actual building operation, potentially undermining the reliability of projected performance metrics.

The applicability of the study findings is further constrained by its climatic specificity. Calibrated primarily for temperate conditions, the results may not be directly transferrable to other climatic zones without significant adjustments. For example, arid and desert climates, characterised by sharp diurnal temperature variations, demand enhanced thermal mass and buffering strategies. Tropical regions, where high humidity and precipitation levels prevail, require advanced moisture control and ventilation systems. Similarly, polar climates with extended periods of low temperatures require tailored insulation strategies, high-performance building envelopes, and greater reliance on renewable heating solutions. As such, extending the applicability of this research requires the integration of climate-resilient design principles and localised energy system optimization.

From an environmental point of view, the study focusses primarily on emissions in the operational phase, offering only a partial representation of sustainability. A more comprehensive approach would involve a complete life cycle assessment (LCA) that accounts for the embodied carbon from raw material extraction and processing, transportation logistics, and end-of-life scenarios such as demolition, recycling, or reuse. Furthermore, the biogenic carbon sequestration potential of wood-based construction materials, a significant contributor to net zero targets, is not addressed, which represents a critical omission in the current sustainability assessment.

Several essential dimensions of building performance are underexplored. These include summer thermal comfort and overheating risk, indoor humidity regulation, air quality parameters such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and fine particulate matter (PM2.5), and acoustic insulation performance. These aspects are critical for the health, well-being, and long-term usability of buildings of occupants, particularly when considering the distinct physical and thermal properties of lightweight wood structures compared to conventional masonry or concrete systems.

To overcome the limitations of current sustainable construction methodologies and drive a systemic shift toward high-performance, climate-responsive buildings, a comprehensive and multidisciplinary research agenda is imperative. This agenda should encompass advanced modeling, empirical validation, integrated life-cycle analysis, and systemic policy and market frameworks. The following strategic directions are crucial to achieving transformative progress in the field.

First, future research must prioritise high-resolution modeling approaches that go beyond static analyses. Transient simulation tools capable of capturing time-dependent phenomena such as stochastic occupant behavior, progressive equipment degradation, and evolving climate conditions are essential for accurately predicting building performance over time. Integrating hybrid modeling techniques that combine physics-based simulations with machine learning algorithms will provide a robust framework to capture nonlinear interactions and optimize performance at building, neighbourhood, and district scales. These models will be vital for supporting data-driven design and policy decisions within increasingly complex urban energy systems.

Second, advancing the integration of renewable energy systems within the built environment is critical. Research should explore the architectural, structural, and operational feasibility of BIPV, thermal energy storage embedded in building envelopes or structural mass, and seasonal energy balancing strategies. Additionally, developing smart grid-compatible buildings capable of bidirectional energy exchange, load shifting, and real-time optimization is fundamental to achieving energy autonomy and enhancing grid resilience. These innovations must be evaluated through comprehensive life-cycle energy analyses to ensure meaningful contributions to decarbonization goals.

Third, a comprehensive and dynamic life-cycle assessment (LCA) framework is needed to capture the full environmental, economic, and social impacts of construction materials and processes. This includes dynamic carbon accounting that reflects time-sensitive emissions, circular economy indicators assessing material reuse and resource efficiency, and resilience metrics evaluating long-term performance under stress. Incorporating social lifecycle indicators will enable a holistic understanding of sustainability encompassing human well-being and community impacts. Such frameworks are essential for informed decision-making, policy benchmarking, and compliance with emerging sustainability standards.

Fourth, greater emphasis must be placed on empirical performance validation through long-term monitoring of real buildings. Sensor-based data acquisition, non-destructive diagnostics, and continuous commissioning protocols are key to verifying predicted performance and identifying gaps. Coupling these with post-occupancy evaluations and crowdsourced occupant feedback will ensure that building systems are both technically sound and aligned with actual user comfort and behaviour. This empirical feedback loop will improve model accuracy, guide iterative design refinements, and foster occupant-centered innovation.

Therefore, research on policy and market transformation is vital to address structural barriers to sustainable construction adoption. Studies should investigate how regulatory innovation can incentivize low-carbon materials, how supply chains can be restructured to support local and renewable resources, and how workforce training programs can prepare skilled professionals for next-generation buildings. The development of financial risk assessment tools and green financing mechanisms will be crucial for scaling sustainable construction investments. Concurrently, emerging technologies such as additive manufacturing, smart materials, digital twins, and blockchain-based material passports offer disruptive potential for transparency, traceability, and precision in construction and warrant dedicated research focus.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This study presented an integrated evaluation of biobased construction systems and decentralised renewable energy configurations for the Africa Golden Riyad building in the hot–dry climate of Fes–Meknes, Morocco. By combining dynamic thermal simulations with HOMER-based hybrid optimisation, the work demonstrated that replacing conventional concrete–brick envelopes with locally sourced wooden structures can deliver substantial performance gains. Specifically, annual energy demand was reduced by 33.3%, operational CO2 emissions were cut by 50%, and summer cooling peaks were significantly lowered, resulting in extended periods of passive thermal comfort and enhanced moisture regulation.

On the supply side, a hybrid rooftop PV and BIPV system with battery storage achieved full renewable energy autonomy, producing nearly 12.5 MWh annually and eliminating reliance on the grid. While the net present cost was relatively high ($45,708 USD), the LCOE remained within viable bounds (0.705 $/kWh), confirming the techno-economic feasibility of off-grid biobased housing in arid regions. The integration of BIPV further underscored its multifunctional role as both an energy source and a passive design strategy, improving façade performance, architectural quality, and urban microclimates.

Beyond technical results, the study contributes to broader sustainability and policy debates. The findings align with Moroccan NDC commitments and global Net-Zero Energy Building (NZEB) targets, while also advancing the discourse on biobased envelopes in hot–dry climates, an underexplored context in existing literature. The demonstrated benefits position wooden construction and BIPV integration as scalable solutions to decarbonise rapidly urbanising regions across North Africa and the MENA zone.

Nonetheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. The results are derived from simulation-based modelling without empirical calibration, economic analyses excluded embodied carbon and full life-cycle costs, and occupancy/battery degradation assumptions were simplified. These constraints highlight the need for pilot projects, long-term monitoring, and expanded techno-economic assessments.

Future research should therefore pursue empirical validation, broaden geographic scope to other climatic contexts, and explore advanced passive measures, digital twin technologies, and district-scale applications. Integrating life-cycle assessments will also be essential to capture embodied impacts and circular-economy considerations.

In conclusion, the Africa Golden Riyad case study demonstrates that biobased construction, when coupled with optimised PV/BIPV and storage, provides a robust pathway to climate-adapted net-zero housing in hot–dry regions. By combining reduced energy demand, lower carbon emissions, enhanced indoor comfort, and complete renewable autonomy, this work establishes a replicable model for sustainable building development and contributes to the international transition toward positive-energy and climate-resilient urban environments.

Author Contributions

Methodology, M.O.I. and A.M.; Software, S.I.K. and A.J.; Validation, A.M.; Resources, M.O.I., A.M., S.I.K. and A.J.; Writing – original draft, M.O.I., A.M., S.I.K. and A.J.; Project administration, M.O.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. (please specify the reason for restriction, e.g., the data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.)

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| BIPV | Building-integrated Photovoltaic |

| BPS | Building Performance Simulation |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| GHG | greenhouse gas |

| LCOE | Levelized Cost of Electricity |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| Nearly ZEB | Nearly Zero Energy Building |

| NZEB | Net Zero Energy Building |

| PEB | Positive energy buildings |

References

- Santos, F.D.; Ferreira, P.L.; Pedersen, J.S.T. The climate change challenge: A review of the barriers and solutions to deliver a Paris solution. Climate 2022, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fam, A.; Fam, S. Review of the US 2050 long term strategy to reach net zero carbon emissions. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 845–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Zhou, N.; Ma, M.; Feng, W.; Yan, R. Global transition of operational carbon in residential buildings since the millennium. Adv. Appl. Energy 2023, 11, 100145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, Y.; Jafarinejad, S.; Anand, P. A review on harnessing renewable energy synergies for achieving urban net-zero energy buildings: Technologies, performance evaluation, policies, challenges, and future direction. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Vand, B.; Baldi, S. Challenges and strategies for achieving high energy efficiency in building districts. Buildings 2024, 14, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffat, S.; Ahmad, M.I.; Shakir, A. Zero-Energy and Low Carbon Buildings. In Sustainable Energy Technologies and Low Carbon Buildings; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 219–258. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, V.J.; Hariram, N.P.; Ghazali, M.F.; Kumarasamy, S. Pathway to sustainability: An overview of renewable energy integration in building systems. Sustainability 2024, 16, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, B.; Meng, X.; Xiao, R. A Comprehensive Review on Technologies for Achieving Zero-Energy Buildings. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iavorschi, E.; Milici, L.D.; Ifrim, V.C.; Ungureanu, C.; Bejenar, C. A Literature Review on the European Legislative Framework for Energy Efficiency, Nearly Zero-Energy Buildings (nZEB), and the Promotion of Renewable Electricity Generation. Energies 2025, 18, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrousso, S.; Kaitouni, S.I.; Mana, A.; Wakil, M.; Jamil, A.; Brigui, J.; Azzouzi, H. Optimal sizing of off-grid microgrid building-integrated-photovoltaic system with battery for a net zero energy residential building in different climates of Morocco. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrutieta, X.; Kolbasnikova, A.; Irulegi, O.; Hernández, R. Decision-making framework for positive energy building design through key performance indicators relating geometry, localization, energy and PV system integration. Energy Build. 2023, 297, 113442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrutieta, X.; Kolbasnikova, A.; Irulegi, O.; Hernández, R. Energy balance and photovoltaic integration in positive energy buildings. Design and performance in built office case studies. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2023, 66, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benziada, R.; Mokhtari, A.; Hadj Mohamed, N.; Benlahbib, F.Z.; Benkhedda, F. Building a Positive Energy in Arid Zones: How to Pass “Energy” Buildings to Efficient Buildings? In Innovations in Green Urbanization and Alternative Renewable Energy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Vassiliades, C.; Minterides, C.; Astara, O.-E.; Barone, G.; Vardopoulos, I. Socio-economic barriers to adopting energy-saving bioclimatic strategies in a Mediterranean sustainable real estate setting: A quantitative analysis of resident perspectives. Energies 2023, 16, 7952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaouzy, Y.; El Fadar, A. Impact of key bioclimatic design strategies on buildings’ performance in dominant climates worldwide. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2022, 68, 532–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljashaami, B.A.; Ali, B.M.; Salih, S.A.; Alwan, N.T.; Majeed, M.H.; Ali, O.M.; Alomar, O.R.; Velkin, V.I.; Shcheklein, S.E. Recent improvements to heating, ventilation, and cooling technologies for buildings based on renewable energy to achieve zero-energy buildings: A systematic review. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, H.C.; Tsai, S.C. Global decarbonization: Current status and what it will take to achieve net zero by 2050. Energies 2023, 16, 7800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamimi, H.A.; Paramita, C. The strategic role of renewable energy in supporting net-zero emissions targets in industrial clusters: Pathways to achieving sustainability. Appl. Environ. Sci. 2025, 2, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, X.; Qiu, B.; Xu, N. Integration of carbon emission reduction policies and technologies: Research progress on carbon capture, utilization and storage technologies. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 343, 127153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnabuife, S.G.; Oko, E.; Kuang, B.; Bello, A.; Onwualu, A.P.; Oyagha, S.; Whidborne, J. The prospects of hydrogen in achieving net zero emissions by 2050: A critical review. Sustain. Chem. Clim. Action 2023, 2, 100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaccia, F. Technology Innovation in the Energy Sector and Climate Change: The Role of Governments and Policies. In Interdisciplinary Approaches to Climate Change for Sustainable Growth; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 159–179. [Google Scholar]

- Obergassel, W.; Xia-Bauer, C.; Thomas, S. Strengthening global climate governance and international cooperation for energy-efficient buildings. Energy Effic. 2023, 16, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cristo, E.; Evangelisti, L.; Barbaro, L.; De Lieto Vollaro, R.; Asdrubali, F. A Systematic Review of Green Roofs’ Thermal and Energy Performance in the Mediterranean Region. Energies 2025, 18, 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharston, R.; Singh, M. The role of passive, active, and operational parameters in the relationship between urban heat island effect (UHI) and building energy consumption. Energy Build. 2024, 323, 114720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, S.; Jia, G.; Li, H.; Li, W. Urban heat island impacts on building energy consumption: A review of approaches and findings. Energy 2019, 174, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, S.; Benzidane, C.; Rahif, R.; Amaripadath, D.; Hamdy, M.; Holzer, P.; Koch, A.; Maas, A.; Moosberger, S.; Petersen, S. Overheating calculation methods, criteria, and indicators in European regulation for residential buildings. Energy Build. 2023, 292, 113170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. Low-carbon urban–rural modern energy systems with energy resilience under climate change and extreme events in China—A state-of-the-art review. Energy Build. 2024, 321, 114661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolokotsa, D.; Pignatta, G.; Ulpiani, G. Nearly Zero-Energy and Positive-Energy Buildings: Status and Trends. Technol. Integr. Energy Syst. Netw. 2022, 239–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Penaka, S.R.; Giriraj, S.; Sánchez, M.N.; Civiero, P.; Vandevyvere, H. Characterizing positive energy district (PED) through a preliminary review of 60 existing projects in europe. Buildings 2021, 11, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Gao, X.; Chen, R.; Yang, H.; Zeng, Z. A dynamic hierarchical partition method for active distribution networks with shared energy storage aggregation. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 1009972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zekiye, A.; Bouachir, O.; Özkasap, Ö.; Aloqaily, M. Blockchain-enabled energy trading and battery-based sharing in microgrids. In Proceedings of the ICC 2024—IEEE International Conference on Communications, Denver, CO, USA, 9–13 June 2024; pp. 4674–4679. [Google Scholar]

- Turci, G.; Civiero, P.; Aparisi-Cerdá, I.; Marotta, I.; Massa, G. Transition Approaches towards Positive Energy Districts: A Systematic Review. Buildings 2024, 14, 3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabzadeh, V.; Frank, R. Creating a renewable energy-powered energy system: Extreme scenarios and novel solutions for large-scale renewable power integration. Appl. Energy 2024, 374, 124088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, J.-P.; Alander, J.; Ponto, H.; Santala, V.; Martijnse-Hartikka, R.; Andra, A.; Sillander, T. Contemporary development directions for urban digital twins. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 48, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco Mauthe Degerfeld, F.; Tootkaboni, M.P.; Piro, M.; Ballarini, I.; Corrado, V. Toward Zero-Emission Buildings in Italy: A Holistic Approach to Identify Actions Under Current and Future Climates. Energies 2025, 18, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Ding, Y.; Li, B.; Athienitis, A.K. A review of climate adaptation of phase change material incorporated in building envelopes for passive energy conservation. Build. Environ. 2023, 244, 110711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Deng, S.; Su, P. Climate-Responsive Design of Photovoltaic Façades in Hot Climates: Materials, Technologies, and Implementation Strategies. Buildings 2025, 15, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aste, N.; Adhikari, R.S.; Buzzetti, M.; Del Pero, C.; Huerto-Cardenas, H.E.; Leonforte, F.; Miglioli, A. nZEB: Bridging the gap between design forecast and actual performance data. Energy Built Environ. 2022, 3, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosamo, H.H.; Nielsen, H.K.; Kraniotis, D.; Svennevig, P.R.; Svidt, K. Improving building occupant comfort through a digital twin approach: A Bayesian network model and predictive maintenance method. Energy Build. 2023, 288, 112992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayaçetin, N.C.; Hozatlı, B. Whole life carbon assessment of representative building typologies for nearly zero energy building definitions. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 95, 110214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtani, S.; Koç, M.; Isaifan, R.J. Mycelium-based thermal insulation for domestic cooling footprint reduction: A review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayhorn, E.; Artuso, T.; White, A.; Metzger, C. Exploring benefits and affordability of clean energy technologies in urban disadvantaged communities–A case study. Energy Policy 2025, 199, 114533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varo, A.; Hamou, D.; Méndez de Andés, A.; Bagué, E.; Aparicio Wilhelmi, M. Commoning urban infrastructures: Lessons from energy, water and housing commons in Barcelona. J. Urban Aff. 2025, 47, 566–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chayaamor-Heil, N.; Houette, T.; Demirci, Ö.; Badarnah, L. The potential of co-designing with living organisms: Towards a new ecological paradigm in architecture. Sustainability 2024, 16, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyal, A.; Singh, D.K.; Kumar, R. Bioclimatic Building Technology. In Thermal Evaluation of Indoor Climate and Energy Storage in Buildings; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 126–156. [Google Scholar]

- Toroxel, J.L.; Silva, S.M. A review of passive solar heating and cooling technologies based on bioclimatic and vernacular architecture. Energies 2024, 17, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessì, V. Environment: A Bioclimatic Approach to Urban and Architectural Design in Sub-Saharan African Cities. In Territorial Development and Water-Energy-Food Nexus in the Global South: A Study for the Maputo Province, Mozambique; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 185–198. [Google Scholar]